Executive summary

Inspired by unprecedented improvements in human health and development in recent decades, our world has embarked on a quest that only a generation ago would have been considered unreachable—achieving sustainable health and development for all. Improving the health and wellbeing of the world’s people is at the core of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), reflected in targets that call for ending the epidemics of AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria; achieving enormous improvements in maternal and child health; and tackling the growing burden of non-communicable diseases (NCDs). Attaining universal health coverage is the means by which these ambitious health targets are to be achieved.

Although on their face, the SDGs reflect an unprecedented level of global solidarity and resolve, the trends that increasingly define our world in 2018 are inconsistent with both the sentiments that underlie the SDGs and the ethos that generated such striking health and development gains in recent years. Democracy is in retreat, and in many countries the space for civil society is declining and the human rights environment deteriorating. Official development assistance for health has stalled, as an inward-looking nationalism has in many places supplanted recognition of the need for global collaboration to address shared challenges. The loss of momentum on global health ignores the urgent need to strengthen health systems to address the steady growth of NCDs, which now account for seven of ten deaths worldwide.

Recent trends in the HIV response are especially concerning. Although the number of new HIV infections and AIDS-related deaths have markedly decreased since the epidemic peaked, little progress has been made in reducing new infections in the past decade. Without further reductions in HIV incidence, a resurgence of the epidemic is inevitable, as the largest ever generation of young people age into adolescence and adulthood. Yet where vigilance and renewed efforts are needed, there are disturbing indications that the world’s commitment is waning. Allowing the HIV epidemic to rebound would be catastrophic for the communities most affected by HIV and for the broader field of global health. If the world cannot follow through on HIV, which prompted such an extraordinary global mobilisation, hopes for achieving the ambitious health aims outlined in the SDGs will inevitably dim.

At this moment of uncertainty for the future of the HIV response and for global health generally, the International AIDS Society and The Lancet convened an international Commission of global experts and stakeholders to assess the future of the HIV response in the context of a more integrated approach to health. A central finding of the Commission is that the HIV epidemic is not on track to end and that existing tools are insufficient. Although antiretroviral therapy (ART) has transformed the HIV response by averting deaths, improving quality of life, and preventing new HIV infections, HIV treatment alone will not end the epidemic. The UNAIDS 90–90-90 approach must be accompanied by a similarly robust commitment to scaled-up primary HIV prevention and to the development of a preventive vaccine and a functional cure for HIV. Ironically, the diminishing energy on HIV is occurring at the moment when lessons learned during the HIV response could serve as pathfinders in the quest for sustainable health for all.

From its inception, the HIV response was a unique undertaking, apart from the broader health system. Although elements of a disease-specific approach will and should be retained, the future of the HIV response will also depend on finding opportunities for integrating HIV services more closely within health systems. Wholesale abandonment of vertical HIV funding would involve considerable risks, as the laser-like focus on a single disease accounts in large measure for the HIV response’s successes. Unique attributes that have defined the HIV response (including its multisectoral and inclusive approach, engagement of civil society, emphasis on equity and human rights, galvanisation of scientific innovation, and foundation of global collaboration and problem solving) must be preserved and mainstreamed across global health practice.

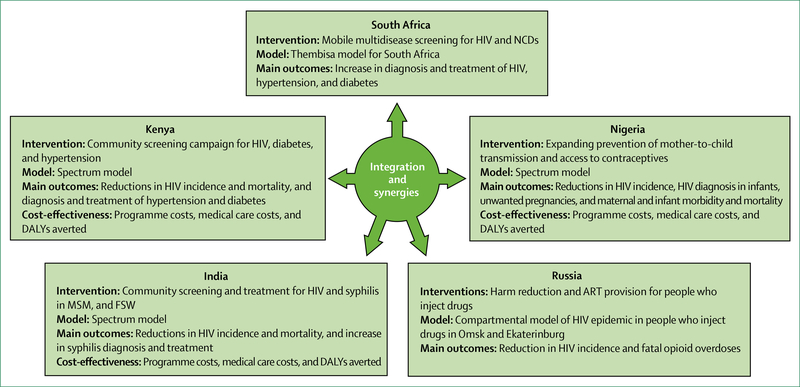

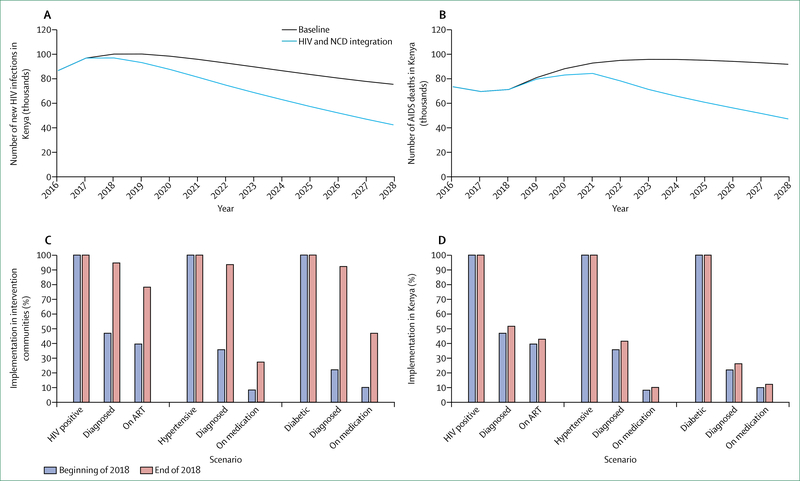

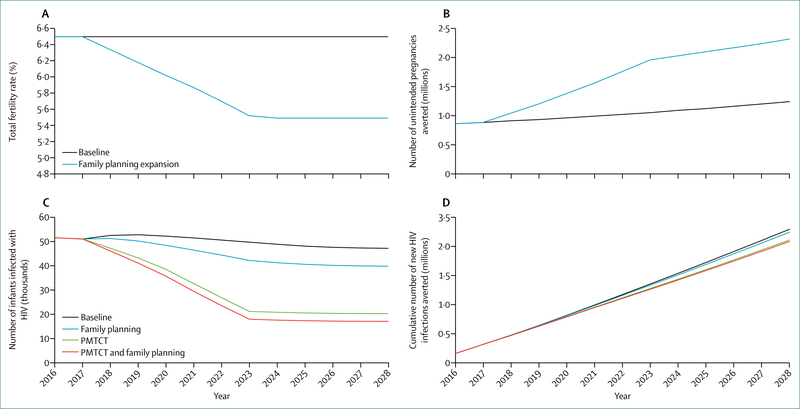

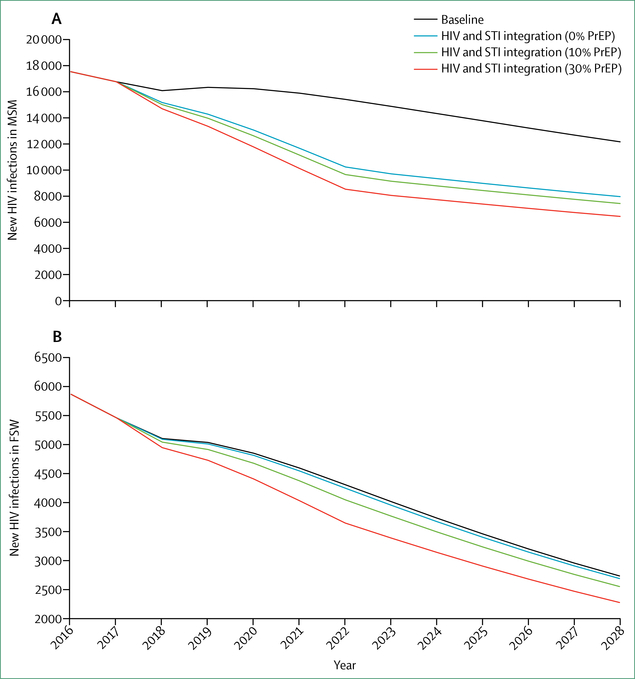

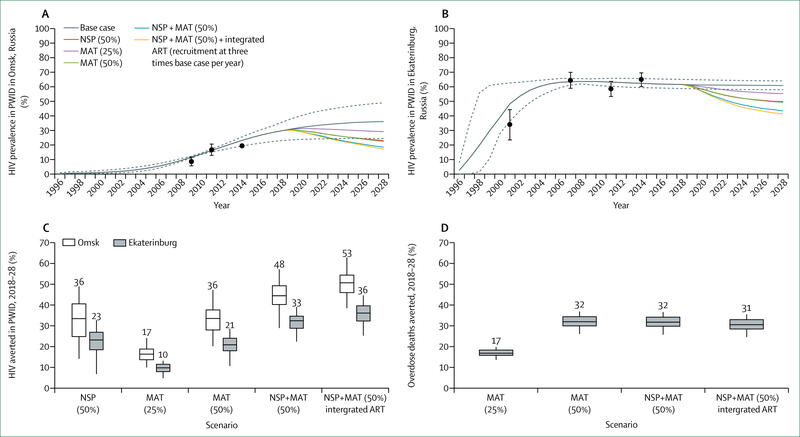

Whether to integrate HIV within broader health systems is not an either-or choice, and optimal paths will differ between settings, populations, and services. To be effective, more integrated approaches must yield improvements both to HIV-related and non-HIV-related health outcomes. In most cases, approaches to integration will and should be incremental, allowing learning by doing. To assess the health and financial benefits of such win-win scenarios, the Commission engaged modellers to examine different scenarios for incremental integration of HIV-related and non-HIV-related services. These include: models in South Africa and Kenya for screening of HIV alongside screening for diabetes, hypertension, and other NCDs; integration of HIV in reproductive health services in Nigeria; integrated management of HIV and sexually transmitted infections in India; and integration of harm reduction and overdose services and ART for people who use drugs in Russia. In each of these scenarios, integrated approaches generated concrete improvements in HIV and broader health outcomes. With one exception (antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis [PrEP] in India), integrated models were consistently found to be cost-effective.

The HIV community must make common cause with the global health field— to make universal health coverage a reality, to substantially increase the share of resources devoted to health, and to build worldwide recognition of health as key to progress across the breadth of the SDGs. The global health field must take a leading role in resisting the turn towards authoritarianism, xenophobia, and austerity with respect to essential public health investments. In a time of fragmentation and uncertainty, the global health field can aid in reminding all of us of our common humanity. Health systems must be designed to meet the needs of the people they serve, including having the capacity to address multiple health problems simultaneously. No one can be left behind in our efforts to achieve sustainable health. Recognising health as an investment, major new resources (from national governments, the international community, and the private sector, involving innovative financing mechanisms) must be mobilised to support stronger, sustainable, and people-centred health systems.

Global health and HIV

The SDGs sharply elevate global health and development aspirations, contemplating a world that is far more prosperous, secure, healthy, and equitable, where human rights and dignity are universally respected, and where human development unfolds in a manner that preserves the natural environment. Yet, the 3 years that have passed since the SDGs were agreed have dimmed prospects for achieving many of these visionary aims. By contrast with the international solidarity, shared commitment, and increased investments that characterised the era of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), much of the world has, since 2015, turned inward and toward authoritarianism, repression, a diminished role for civil society, a policy of austerity for public investments, and suspicion of international cooperation. As a result of civil conflicts that have yet to elicit an appropriate international response, more people than ever have been forced from their homes and countries. At a time when the fruits of scientific advances are so evident, denial in many quarters of the role of humankind in the degradation of our environment threatens the very health and wellbeing of our planet and our civilisations.

Among the reasons why the world opted for such an ambitious agenda for the SDGs was the success of the HIV response. As a result of a worldwide mobilisation, the incidence of HIV infections peaked and began to decrease in all parts of the world, and AIDS-related mortality decreased from 1–9 million in 2005 to 1–0 million in 2016.1 The HIV response has not been an unalloyed story of achievement, as the world’s capacity to respond effectively to the epidemic has been undermined by 15 years of relative inaction in the epidemic’s early stages, an approach to epidemic management that has undervalued primary prevention, and the enduring stigma associated with HIV.

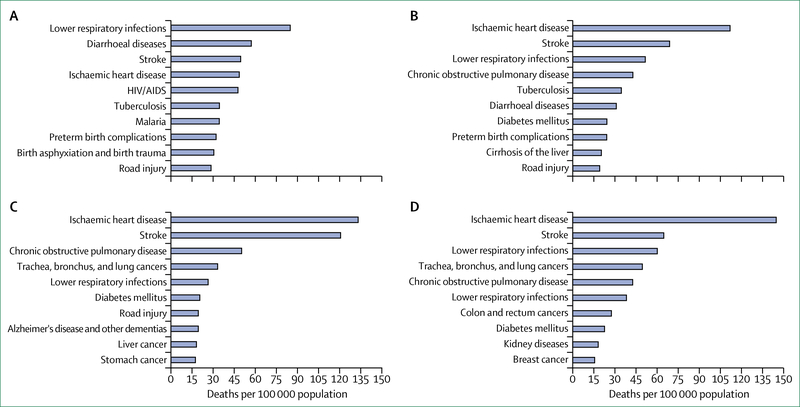

The broader global health community, facing both historic opportunities and profound challenges, could potentially benefit from lessons learned from the successes and failures of the global HIV response. With its multisectoral and inclusive approach, mobilisation of political commitment, engagement of civil society at every level, emphasis on equity and human rights, galvanisation of scientific innovation, and foundation of global collaboration and problem solving, the HIV response has properly been cited as a model for the future of global health.2 The global health challenge remains immense, with millions of people in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs) dying each year from causes that have either been largely eradicated or are decreasing in prevalence in high-income countries (figure 1).3 Whether the world is prepared to meet these challenges is unclear. Although the incidence of communicable, maternal, neonatal, and nutritional diseases have decreased worldwide since 1980,3 the most recent projections indicate that financial resources available for health programmes in LMICs are likely to fall far short of amounts needed to reach the health targets set forth in the SDGs.4 Persistent weaknesses of health systems undermine prospects for progress in addressing the full panoply of health challenges.

Figure 1: Ten leading causes of death in 2015.

(A) Low-income economies. (B) Low-middle-income economies. (C) Upper-middle-income economies. (D) High-income economies. Source: WHO.

At the very moment when HIV could serve as a pathfinder for global health, there are signs that global commitment to build on the gains achieved against HIV thus far is waning. From 2013 to 2016, international HIV assistance was reduced by roughly 20%, from almost US$10 billion to US$8·1 billion.5

Relinquishing the fight against HIV before it is over would have disastrous consequences, both for people affected by HIV and for the broader global health community. Unless further investments are made to accelerate expansion of HIV prevention and treatment programmes, the HIV epidemic is likely to rebound and grow far more serious in the coming years, especially as the world’s largest-ever cohort of young people age into adolescence and young adulthood.6 Notwithstanding the enormous progress that has been made in the HIV response, HIV remains “the epidemic of our time”.7 In 2015–16, an estimated 36·7–38·8 million people were living with HIV worldwide, including 1·9–2·5 million newly infected in 2015.1,8 More than 35 million people have died of AIDS-related causes; 1·0 million of these deaths were in 2016.9 A refusal to follow through to achieve long-term control of the epidemic would merely repeat a longstanding pattern in global health, when failure to sustain a surge in global interest in combating particular health threats allows these epidemics to return in force. The history of malaria elimination efforts is a case in point, as the failure to sustain malaria-related control programmes, funding, and research investments led to an abandonment of the global malaria elimination campaign in 1969 and subsequent increases in the global malaria burden.10 At a moment when the means to improve human health are greater than ever, allowing a resurgence of HIV through neglect and apathy could deal a blow from which the broader cause of global health could need decades to recover.

The relationship between the HIV response and the broader global health field is multilayered and bidirectional. Even as the HIV response offers important lessons from which global health can learn, it is also clear that controlling the HIV epidemic will depend in large measure on the broader global health and development fields. However, the exceptionalist approach to the HIV epidemic, in which the HIV response has often unfolded as a vertical undertaking, distinct from other health programmes, has achieved historic results and should not be jettisoned lightly.

Both the HIV response and the broader global health field share a commitment to the development of health systems that are capable of addressing several health challenges at the same time. In many settings, robust, if still flawed, service systems have been developed for certain populations (eg, pregnant women, children) or for priority health conditions (eg, maternal and child health, HIV, and other communicable diseases). However, health systems as a whole are largely unprepared for providing care that is holistic, universal, and well coordinated. In the still-early years of the SDG era, the gap between reality and the vision of sustainable health remains gaping.

In the midst of uncertainty about the long-term feasibility of an exceptionalist HIV approach and the prospects for achieving the lofty health targets in the SDGs, the International AIDS Society (IAS)-Lancet Commission on the Future of Global Health and the HIV Response was established in 2016 to critically examine future prospects for global health and the HIV response. The Commission was tasked with assessing the future of the HIV response in a more integrated global health and development agenda, with the aim of advising how best to achieve global control of the HIV pandemic in an era in which health and development priorities are proliferating. The Commission studied the history of the HIV response to discern how experience in responding to HIV might inform and strengthen global health more broadly. Modelling exercises were undertaken to assess the effect of various approaches to improve integration of HIV and non-HIV-related services. The most salient threats to global health and to the goal of universal health coverage were identified.

With this report, we summarise the findings of the Commission, and we seek to articulate a vision for the future of the HIV response and global health that builds common cause across health and development movements and sectors. Rather than despair over the trends and patterns of the past several years, we must instead look to the extraordinary achievements of the past two decades to embolden us and reinforce our resolve to rejuvenate the HIV response and strengthen the broader cause of global health. By taking on board the lessons of the HIV response, the global health field can be made fit for the purpose of realising the vision of sustainable health for all. Global health can serve as a driving force to repudiate and discredit the continuing retreat from international solidarity, human rights, reason, scientific evidence, and open societies. Global health can serve as a pioneer in a re-engineering of the development project, from one based on charity from the high-income countries to one that tackles the central determinants of global health inequities. Just as the HIV response has demonstrated that global problems demand global solutions, the future health and wellbeing of our planet relies on us to recognise, celebrate, and build on our common humanity.

With respect to the flagging response to HIV, the Commission hopes that this report serves as a wake-up call. Without a thorough rejuvenation of the HIV response and a change of course, we are likely to see a resurgence of the epidemic. After such history-making successes from unprecedented global solidarity and collaboration, the world can and must do better.

To realise the vision of sustainable health for all, we must ensure that health systems are equipped to bring communicable diseases under control and to respond effectively to the growing burden of NCDs. A focused response and categorical HIV funding will remain crucial to avoid a resurgence of HIV and to bring the global pandemic under control. However, immediate and incremental steps are needed to strategically integrate HIV services into co-located primary care platforms and toward the longer-term goal of creating fully integrated, co-located, and patient-centred health-service systems.

Global Health in 2018: new ambitions and growing threats

The Agenda for Sustainable Development envisages “a world free from poverty, hunger, disease and want, where all life can thrive.”11 SDG 3 calls for concerted action to ensure healthy lives and promote wellbeing for all at all ages.11 SDG 3 also calls for ending the epidemics of AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria, and neglected tropical diseases; eliminating preventable deaths in children younger than 5 years; and reducing by a third the number of deaths from NCDs.11 Under the Agenda for Sustainable Development, universal health coverage serves as the primary vehicle for continuing and fully leveraging the momentum on health.11

The health targets of SDG 3 build on historic gains made under the MDGs (panel 1).12 The health gains during the MDG era coincided with, and were enabled by, advances across the broader development agenda. Whereas nearly half of the population in LMICs lived on less than $1·25 per day in 1990, this proportion had fallen to 14% by 2015.12 Primary school attendance worldwide increased between 2000 and 2015, and differences in secondary school attendance between boys and girls diminished or disappeared altogether in some regions.12

Panel 1: Health targets for Sustainable Development Goal 3.

By 2030, reduce the global maternal mortality ratio to less than 70 deaths per 100 000 livebirths

By 2030, end preventable deaths of newborn babies and children younger than 5 years, with all countries aiming to reduce neonatal mortality to at least as low as 12 deaths per 1000 livebirths and under-5 mortality to at least as low as 25 deaths per 1000 livebirths

By 2030, end the epidemics of AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria, and neglected tropical diseases and combat hepatitis, water-borne diseases, and other communicable diseases

By 2030, reduce by a third premature mortality from non-communicable diseases through prevention and treatment, and promote mental health and wellbeing

Strengthen the prevention and treatment of substance abuse, including narcotic drug abuse and harmful use of alcohol

By 2020, halve the number of deaths and injuries from road traffic accidents globally

By 2030, ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive health-care services, including for family planning, information, and education and ensure the integration of reproductive health into national strategies and programmes

Achieve universal health coverage, including financial risk protection, access to quality and essential health-care services, and access to safe, effective, quality, and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all

By 2030, substantially reduce the number of deaths and illnesses from hazardous chemicals and air, water, and soil pollution and contamination

Strengthen the implementation of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control in all countries, as appropriate

Support the research and development of vaccines and medicines for the communicable and non-communicable diseases that primarily affect developing countries, provide access to affordable essential medicines and vaccines, in accordance with the Doha Declaration on the TRIPS Agreement and Public Health, which affirms the right of developing countries to use to the full the provisions in the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights regarding flexibilities to protect public health, and, in particular, provide access to medicines for all

Substantially increase health financing and the recruitment, development, training, and retention of the health workforce in developing countries, especially in least developed countries and small-island developing states

Strengthen the capacity of all countries, in particular developing countries, for early warning, risk reduction, and management of national and global health risks

Decreasing prominence of health on the global political stage

Whereas health occupied three of the eight MDGs, health is specifically addressed in only one of 17 SDGs and ten of 169 SDG targets. Effective measures to improve global health outcomes draw on principles of international solidarity and shared responsibility, recognising that all of us, irrespective of where we live, have a stake in improving the health of our planet and its people. Yet growing hostility towards globalisation, which has become especially pronounced in many countries that have long served as global health donors, poses a potential threat to all forms of international and multilateral cooperation, including global collaboration to address health and development challenges. As threats to global solidarity have intensified, stresses on such multilateral institutions as the European Union (EU) have become more apparent.

Substantial additional health investments will be necessary to achieve the SDG 3 targets. Yet prospects for mobilising such sums appear in doubt as global assistance for health has flattened since 2010.13 Although domestic investments in health by LMICs have generally increased since 2000,14 these investments frequently fall short of leaders’ stated ambitions. In the Abuja Declaration of 2001, African heads of state committed to allocate 15% of government budget to health, yet most countries are not reaching this agreed benchmark.15 Economic growth in LMICs (estimated at 3·9% in 201616), if sustained, has the potential to expand the fiscal space for investments in health if sufficient political commitment exists. However, most low-income countries will for the foreseeable future lack the capacity to fully finance health and development initiatives on their own, underscoring the continued need for robust and sustained international assistance.17

Weak and dysfunctional health systems and the future of global health

Health systems in much of the world appear unprepared to realise the vision of sustainable health for all. As recently as 2013, 37 of 49 countries in Africa did not have a single medical laboratory that satisfied international quality assurance standards.18 In 2013, the number of health workers needed to provide essential health services fell 17·4 million short of the number needed, with the most severe shortages occurring in Africa and southeast Asia.19 In Africa, health worker shortages are expected to worsen in the coming years.19

Weak and overburdened health systems that are already struggling to provide basic services will confront vastly more serious stresses in the coming years. The global population is projected to grow from 7·6 billion people in 2017, to 9 8 billion people by 2050, with the sharpest increase set to occur in Africa, where the population will roughly triple in size.20 Many health systems are unprepared to carry through on the SDG 3 target of reducing NCD-associated premature mortality by a third. Although LMICs are home to 70% of global cancer deaths, they account for only 5% of cancer spending world-wide.21 Some countries in Africa have no clinical oncologists, whereas India reportedly had only 29 treatment centres to manage cancer for more than 1 billion people in 2010.22

Confronting the inherent inequities of the international order

The narrowing of economic disparities between rich and poor countries represents one of the signal achievements of our era, but yawning inequities in access to resources between countries and regions persist. In 2016, the per-capita gross domestic product (GDP) in North America was more than 34 times higher than in south Asia or sub-Saharan Africa and nearly 92 times higher than in low-income countries generally.23 These extraordinary disparities in access to the fruits of the global economy are inevitably reflected in health outcomes because lower socioeconomic status is closely correlated with poorer health.24

In addition to differences between countries, persistent social and economic inequalities within countries increase vulnerability to disease and diminish service access. In diverse countries, lower-income households consistently have poorer access to health care than the more affluent and experience comparatively greater morbidity and mortality.25

Existing global health mechanisms and practices fail to ensure ready, equitable access to international public goods such as medicines and diagnostics. Although the 2001 Doha Declaration on TRIPS and Public Health recognised the flexibility of countries under international law to obtain access to essential medicines, the global community has yet to find a workable balance between trade and the right to health. Unfortunately, the HIV response, which achieved a 99% reduction in the annual cost of first-line ART between 2000 and 2015, largely remains an outlier with respect to medicines access in resource-limited settings. Affordable diagnostic tools are also often in short supply. Nearly half of African countries have no cancer radiotherapy services, leaving four of five Africans without access to radiotherapy.26

The 2014 Ebola outbreak in west Africa underscored the ongoing crisis of global health governance.27 Although the International Health Regulations were designed in part to discourage restrictive and coercive responses to health emergencies, nearly a quarter of the WHO member states imposed restrictions on trade and travel in response to the Ebola outbreak.28 WHO, a cornerstone for global health governance, remains chronically underfunded and hobbled by a decentralised structure, which often inhibits rapid and effective responses to emerging health crises.29

Deteriorating environment for human rights, sound governance, and global cooperation

The underlying political and social environment is shifting in ways that are inimical to good health and to the development of sound and sustainable health systems. After years in which the proportion of the world’s people living in free and democratic societies increased, freedom is now in retreat, with one global freedom index reporting the 11th consecutive year of decline in 2017.30 Accompanying this democratic retreat is growing official hostility toward civil society in many countries.30

The increase in authoritarianism and the decrease in adherence to democratic norms also risk normalising human rights violations and degrading universal human rights commitments. The global retreat on human rights has exacted an especially heavy toll on migrants and other disenfranchised groups. In 2015, the global population of displaced people was greater than ever (21 million people) as raging conflicts in Syria and elsewhere have compelled millions of people to flee their homeland.31 More recently, government-sanctioned violence against the Rohingya minority in Myanmar has caused hundreds of thousands of people to seek sanctuary in neighbouring countries.

Discriminatory practices within health systems, which frequently mirror prejudices prevalent in the broader population, prevent many from accessing the most basic health services. Migrants, indigenous populations, and ethnic minorities often encounter hostility from health providers (including, in the case of migrants, formalized exclusion of non-citizens from health-care services).25 Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people worldwide experience considerable difficulties in accessing good quality and non-judgmental health services.32

Threats to planetary health

While political, social, and economic patterns threaten the foundation of global health, continued deterioration of the physical environment potentially poses an existential threat to the planet.33 The planet is warming because of human activity, and failure to take swift action to arrest or slow the growing concentration of manmade greenhouse gases is projected to lead to further devastating increases in temperature in the coming decades. Threatening the very habitability of our planet, these trends will have powerful effects on health, affecting food production, susceptibility to heat-related illnesses and natural disasters, and patterns for vector-borne and water-borne diseases.

The world’s response to climate change in many respects serves as a fundamental test case for international action to address shared threats. In this respect, recent trends are not promising. In 2018, authoritative reports on climate trends indicated that no developed country is on track to meet its pledges under the Paris Agreement and that current warming trends suggest that the global temperature will rise in coming decades well beyond the maximum threshold set by the Paris Agreement.34

Towards sustainable health for all: a status report

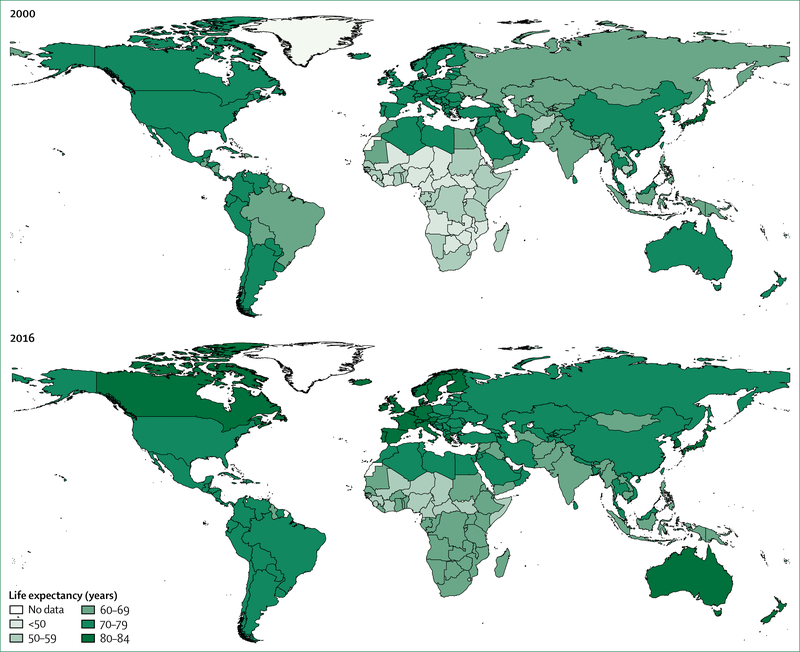

As a result of remarkable increases in health spending,35 the much healthier since 1990. Under-5 mortality decreased from 90 deaths per 1000 livebirths in 1990, to 43 deaths per 1000 livebirths in 2015, the proportion of children younger than 5 years who are underweight decreased from 25% to 14%, and maternal mortality decreased by 45% worldwide.12 Adolescent mortality is estimated to have decreased by about 17% since 2000. Notable reductions in the incidence of new infections and deaths associated with HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria between 2000 and 2015 led the UN to declare that these epidemics had been halted and reversed.12 Globally, life expectancy increased faster in 2000–15 than in half a century, increasing on average a full 5 years. The greatest increase in life expectancy occurred in Africa, which had previously seen sharp reductions in life expectancy as a result of the HIV epidemic (figure 2). With three of the eight MDGs specifically focused on health, the MDG agenda catalysed a remarkable increase in official development assistance for health.

Figure 2: Life expectancy in 2000 and 2016.

Source: WHO

An enormous gap persists between current reality and the vision of sustainable health for all. Although numerous LMICs have made important strides in expanding health coverage,36 400 million people do not have access to essential health services, and 6% of people in LMICs are impoverished or pushed deeper into poverty by household medical expenses.37

More than 15 000 children younger than 5 years die every day, largely from preventable communicable diseases and malnutrition.38 45% of childhood deaths are associated with undernutrition, 80% are associated with low birthweight, and NCDs are increasing as a major cause of death in children.39 In 2015, 1·2 million adolescents died, largely from preventable causes.40 Adolescents are at high risk of sexually transmitted infections (including HIV41), unintended pregnancy, unmet contraceptive need, and contraceptive failure.42

NCDs (eg, cancers, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and diabetes) account for 70% of deaths worldwide, and more than 75% of NCD-related deaths occur in LMICs.43 In the future, LMICs will account for up to 80% of the anticipated global increase in cancer cases and deaths.44 NCDs are projected to exact economic costs of $47 trillion in the next two decades,45 and progress in combatting NCDs will affect the world’s ability to attain at least nine of the 17 SDGs.46

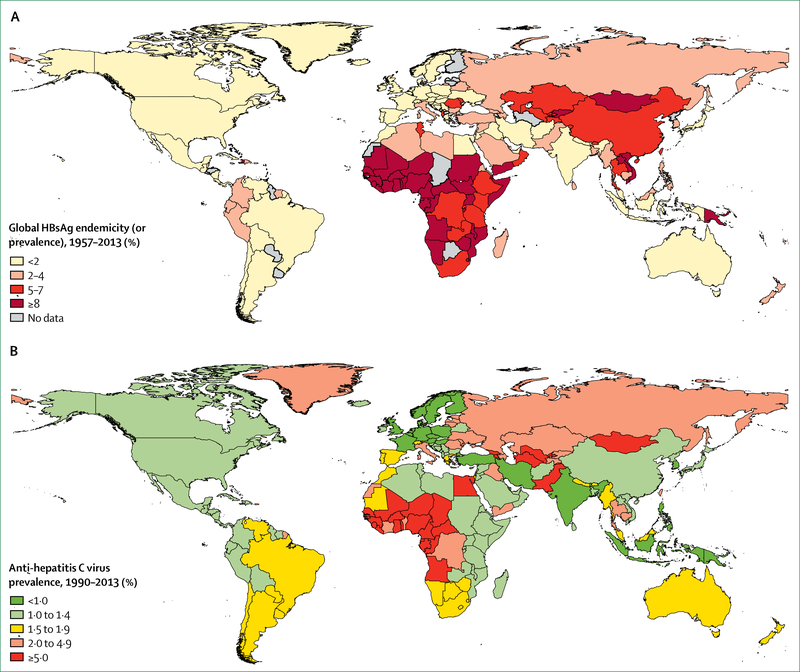

While the world mobilises to address NCDs as the primary driver of mortality and disability, the global community must follow through on its commitments to make communicable diseases a thing of the past. Tuberculosis, for example, is the leading cause of death by single infectious agents, the ninth leading cause of death overall (accounting for 1·7 million deaths in 201638), and the leading cause of death in people living with HIV.47 Africa accounts for roughly 80% of all cases of and death from combined HIV and tuberculosis. Unlike HIV, tuberculosis is a curable infection. Nearly half of the world’s population is at risk for malaria, and no meaningful progress in reducing malaria cases and deaths was seen in 2016.48 Likewise, the challenge of addressing viral hepatitis remains considerable (figure 3). An estimated 71 million people worldwide have chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, and 2·7 million of these people have HIV infection.51 An estimated 1·34 million people die from viral hepatitis each year, and this includes an estimated 399 000 deaths related to HCV infection.51

Figure 3: Global burden of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus.

(A) Prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection between 1957 and 2013. (B) Prevalence of anti-hepatitis C virus between 1990 and 2013. Adapted from Schweitzer et al (2015)49 and from Gower et al (2014),50 by permission of Elsevier.

Alcohol and drug use disorders are associated with extensive morbidity, disability, and mortality52 and are also closely linked with HIV transmission through the sharing of syringes and the effects of specific drugs (eg, amphetamines) on condom use and sexual HIV transmission.53 In 2016, mental health disorders accounted for nearly 16% of years lived with disability worldwide.52

HIV and global health: what have we learned, and where do we go from here?

The global HIV response serves as one of the most inspiring undertakings in the history of global health. The escalating toll of AIDS across the world in the 1980s and 1990s, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, resulted in “the single greatest reversal in human development” in history.54 However, a genuinely multi-sectoral and multidimensional global mobilization uniting and synergising a diverse set of actors from all across the world achieved what some considered unattainable: halting and beginning to reverse the epidemic.55 These health advances have had profoundly positive effects on households, communities, and societies. In South Africa, home to nearly one in five people living with HIV, sharply reduced AIDS-related mortality stemming from a remarkable expansion of HIV treatment services caused average life expectancy to increase from 52 years to 61 years in less than a decade.56

An unprecedented expansion of access to ART

The greatest achievement of the HIV response to date has been the unprecedented global expansion of access to ART. Although only 680 000 people were receiving ART in 2000 (most of them in high-income countries), by June 2017, this number had risen to 20·9 million people (18·4 million–21·7 million), or 57% of all people living with HIV worldwide.57 In 2016, an estimated 1·6 million deaths were averted worldwide as a result of ART.1

The history of ART and its effect on the global HIV epidemic is one of multidisciplinary collaboration, continual improvements in the quality and durability of treatment regimens, ever-increasing aspirations for service coverage, and passionate advocacy to overcome the resistance that HIV treatment expansion elicited. Public and private sector researchers combined to generate the therapies capable of halting viral replication; civil society advocacy and competition from and within the generic pharmaceutical industry coalesced to produce marked reductions in the prices of ART; robust funding, primarily at the outset from international donors, enabled rapid introduction and expansion of treatment programmes; and programme planners and implementers (as well as affected communities) have helped to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of HIV treatment service delivery. As the scientific evidence expanded, normative guidance on HIV treatment evolved, and in 2015, WHO recommended the initiation of ART for all people living with HIV, irrespective of disease stage, both for clinical benefit to the individual living with HIV and for the prevention benefits of successful viral suppression on onward transmission.58

Substantial scientific advances have also been achieved in primary HIV prevention. Principally due to implementation of ART for pregnant women and other measures to prevent vertical HIV transmission, the number of children newly infected with HIV decreased from 470 000 children in 2002, to 160 000 children in 2016.1 Since results of clinical trials more than a decade ago showed that medical male circumcision reduces the risk of female-to-male sexual HIV transmission by about 60%,59 nearly 15 million men in sub-Saharan Africa have been circumcised.60 PrEP has substantial HIV prevention efficacy,61 and cash transfers might reduce young people’s HIV risk behaviours or the odds of acquiring HIV, or both.62

The future of HIV: an unfinished agenda with an uncertain outcome

The fight against HIV is far from over. In eastern Europe and central Asia, the incidence of new HIV infections increased by 60% between 2010 and 2016,5 and the incidence is also trending upwards in populous countries such as Philippines and Ghana.1 Progress in reducing new HIV infections in adults has largely stalled worldwide. Although UNAIDS estimates that new HIV infections in adults decreased by a modest 11% between 2010 and 2016,5 the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015 investigators found no meaningful decrease in new HIV infections in the previous decade.8 The coming demographic wave, as children become adolescents and young adults, threatens major expansions of the epidemic. In 2016, 43% of the population in low-income countries, 43% of the population in all of sub-Saharan Africa (excluding high-income countries), and 31% of the population in lower-middle income countries were younger than 15 years.63 In a recent modelling study, the failure to build on existing prevention and treatment coverage gains was found to result in a rebound of the HIV epidemic in the coming years.64

The 90–90-90 approach: its promise and its limitations

As part of the SDGs, UN member states have pledged to end the AIDS epidemic as a public health threat by 2030, which has been defined as reducing the number of new HIV infections and AIDS-related deaths by 90% relative to 2010. The cornerstone of this global undertaking is the UNAIDS 90–90-90 approach, which follows that by 2020, 90% of all people living with HIV will know their HIV status, 90% of people with an HIV diagnosis will receive ART, and 90% of people receiving ART will achieve viral suppression.65 The 90–90-90 approach is grounded in the considerable evidence that ART sharply reduces the risk of HIV transmission.66 Within the Fast-Track strategy proposed by UNAIDS to reduce the incidence of new HIV infections to less than 200 000 annually by 2030, UNAIDS estimates that scaled-up ART will account for 60% of HIV infections averted during this period.64

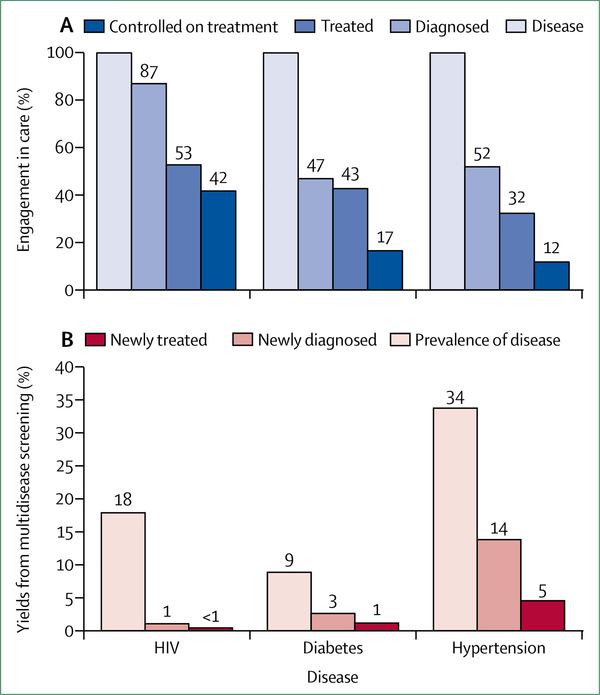

However, it is increasingly clear that the 90–90-90 approach on its own will be inadequate to end the epidemic. Even as ART coverage has steadily increased and as the HIV response has adopted an almost singular focus on HIV treatment expansion, the rate at which the incidence of new HIV infections is decreasing remains far too slow to achieve epidemic control. A case in point is Botswana, which might already have achieved the 90–90-90 target,67 but the decrease in new HIV infections is far too modest to end the country’s epidemic.1

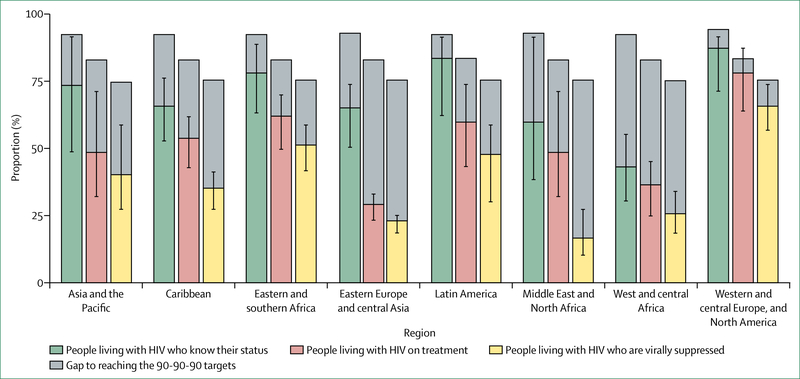

Outcomes across the HIV treatment continuum in eastern and southern Africa, Latin America, and high-income countries are cause for optimism that the 90–90-90 target might be achieved by 2020 in these settings (figure 4). However, in other regions, the proportion of people living with HIV who had suppressed virus in 2016 was far off the pace for the 73% target viral suppression benchmark for 2020 under the 90–90-90 approach (viral suppression was achieved for 34% of people with HIV in the Caribbean, 25% in west and central Africa, 22% in eastern Europe and central Asia, and 16% in the Middle East and north Africa).1 Ensuring widespread viral suppression is also a challenge in many high-income countries such as the USA, where only 49% of people with HIV were virally suppressed in 2014.68

Figure 4: Knowledge of HIV status, treatment coverage, and viral load suppression by region in 2016.

Comparison of HIV testing and treatment cascades by region reveals different patterns of progress. Western and central Europe and North America are approaching global targets. Latin America and eastern and southern Africa show high levels of achievement across the cascade. Eastern Europe and central Asia, the Middle East and North Africa, and western and central Africa are clearly off track. Source: UNAIDS special analysis, 2017.

The prevention benefits of expanded ART would be substantially enhanced by a similarly vigorous scale-up of other strategic prevention interventions. In Uganda, the combination of steady expansion in ART coverage, a near-doubling of the rate with which HIV viral suppression is achieved, and roll-out of medical male circumcision was associated with a 42% reduction in HIV incidence in 10 years.69 In cities in high-income countries, the prioritised roll-out of PrEP as a complement to the test-and-treat approach has contributed to sharp decreases in the incidence of new HIV infections, especially in gay and bisexual men.70,71 Although the so-called combination prevention approach has long been recommended as the optimal means to reduce the risk of new HIV infections, the approach has seldom been implemented at scale because national HIV responses have increasingly come to be dominated by an overwhelming emphasis on HIV treatment. Less than one in five people at risk of HIV acquisition have access to prevention programmes because of chronic underfunding of HIV prevention.6

An alternative future for the HIV epidemic: persistent settings and communities with heavy HIV burdens

Far from putting the world on course to vanquish AIDS, existing approaches are leaving numerous populations behind. In sub-Saharan Africa, young people and men of all ages consistently have suboptimal outcomes along the HIV treatment continuum.5 Various marginalized populations at increased risk of HIV infection, including gay and bisexual men, people who inject drugs, sex workers, transgender people, and the sex partners of people in these groups, accounted for 44% of new HIV infections worldwide (80% of new infections outside sub-Saharan Africa).5

Contrary to optimistic expectations of ending AIDS, these trends point toward the likelihood of a much more concerning scenario. Athough the desired benefits of population-level viral suppression could be realised in settings and populations where access to HIV testing and treatment services is widespread, those people living in countries or belonging to marginalised populations in which services are difficult or impossible to obtain will remain highly vulnerable to HIV acquisition.

Already, evidence suggests that the epidemic is sustained in substantial high-prevalence and high-incidence geographical areas in large measure by the inability of service systems to reach and engage specific populations. For example, even as the incidence of HIV infections in the USA have decreased overall since 2008,72 black gay and bisexual men now have a 50% lifetime chance of acquiring HIV (figure 5).73 Rates of viral suppression in people living with HIV in the USA have steadily improved,74 but black gay and bisexual men living with HIV are markedly less likely than other people living with HIV to receive ART, remain engaged in care, and achieve viral suppression.75 Major pockets of endemic HIV are also apparent in Russia, where HIV infections are heavily concentrated in six subnational regions (referred to as Federal Subjects) in eastern and western Siberia, along principal overland heroin and opium trafficking routes out of Afghanistan. In the case of people who inject drugs, in Russia and elsewhere, access to prevention and treatment services is extremely limited.76 A similar clustering of susceptibility to HIV is apparent in the KwaZulu-Natal province of South Africa, where adolescent girls and women younger than 25 years are roughly three times more likely than men younger than 25 years to be living with HIV.77

Figure 5: African American men who have sex with men have an increased lifetime acquisition probability of HIV infection in 2018.

Credit: © NASTAD.

The persistence of large, high-prevalence, and high-incidence areas in the midst of epidemics that are large and small, decreasing and increasing, is a global phenomenon. Compared with the population as a whole, gay men and other men who have sex with men (MSM), people who inject drugs, sex workers, and transgender women are 19 times,78 13·5 times,79 22 times,80 and 49 times,81 more likely to be living with HIV, respectively. Yet although these marginalised populations have a disproportionate and growing HIV burden, they are often the groups least likely to obtain access to HIV prevention, treatment, and care services.78

With the failure of existing service approaches to address persistent susceptibility or to reach those people who are in greatest need, it is clear that new and scaled-up service delivery and community engagement strategies will be needed. The transmission-preventing potential of scaled-up ART must be matched with an equally strong reduction in the risk of HIV acquisition and transmission.7,82 And programmes for the delivery of prevention and treatment services must be coupled with renewed efforts to address the social and structural factors that increase risk and susceptibility and diminish utilisation of essential services.

Activism and the future of the HIV response

Grassroots political activists have had a defining role in the HIV response. In the epidemic’s early years, gay communities in several countries mobilised to resist the imposition of coercive measures in what was then a new and frightening epidemic. Across the world, chapters of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) marched in the streets and infiltrated decision making bodies to demand greater investments in HIV research and expedited, people-centred approaches to the evaluation and approval of new medicines. In South Africa, activism by Treatment Action Campaign and other groups led to dramatic changes in national HIV policies, which have reverberated around the world. In every region, activists have emerged to challenge high prices for HIV treatments and to insist on approaches to intellectual property that take into account the needs of people with life-threatening diseases.

Today, inclusion of civil society and people living with HIV is standard practice of many HIV-related decision making bodies. Non-governmental representatives, including from organisations and networks of people living with HIV, are now routinely involved in national HIV-related advisory bodies. Vigorous activism persists in many countries and regions. However, as the incidence of HIV infections and AIDS-related mortality have decreased, and as funding for civil society activities has diminished, so have the magnitude and intensity of AIDS activism. In particular, the kind of cohesive activist voice that united the global north and south and laid the foundation for the HIV treatment revolution is no longer evident. In some cases, experiences in the HIV response have led some activists to concentrate more on broader health and human rights issues. For some, a focus on service delivery in their own communities has taken the place of activism for systemic change.

Standard inclusion of civil society in national and global bodies is one of the great achievements of the HIV response and one of its defining features, yet the voices of grassroots activists are at risk of being silenced or muffled. As a class of international and non-governmental HIV professionals has developed, questions have emerged about a potential disconnect between civil society spokespeople at the global level and those working in communities. The inclusion of civil society in decision-making bodies, especially at the global level, is often more tokenistic than substantive.

How to rejuvenate and empower a new wave of activism on HIV remains a topic of considerable discussion and debate within the HIV community (figure 6). What is clear is that the loss of a strong activist presence diminishes both the accountability of the HIV response and the likelihood that our policies, programmes, and approaches will respond to the communities being left behind. Few advocacy community equivalents to HIV exist in other domains of global health. Infusing the broader global health field with the grassroots energy and leadership that has defined the HIV response could revolutionise global health and elevate it on the global political agenda, but a key first step towards this end is to reinvigorate HIV activism.

Figure 6: Activism on HIV in India.

Students recognise International AIDS Candlelight Memorial Day with painted faces at the Centre for Social Work, Panjab University, Chandigarh, India. Credit: © 2016 Gaurav Gaur, Photoshare.

The future of HIV exceptionalism

From the earliest recognition of the epidemic in the early 1980s, the HIV response adopted an exceptionalist approach. Rather than look to often-overburdened health systems to manage HIV as one of many health problems, specific vertical funding mechanisms and frequently disease-specific service delivery channels were established to respond to the global emergency. In 2000–01, diverse global stakeholders spearheaded the creation of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, which, by the end of 2016, had allocated more than $17 billion for HIV programmes in more than 100 countries, while also providing much needed support to chronically neglected tuberculosis and malaria.83 Created in 2003, the US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) is the largest bilateral health programme ever devoted to a single disease. The UN also took a distinctly unorthodox approach to HIV, vesting UN leadership on the epidemic, not with the designated health agency WHO, but in the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), a multidisciplinary and cosponsored programme.84

Whether such an exceptionalist approach will remain feasible is unclear. Overall investments in the HIV response, taking into account both domestic and international sources, has remained relatively flat in recent years, at about $19.1 billion, roughly $7 billion short of the amounts needed to achieve 90–90-90 and the broader UNAIDS Fast-Track strategy.5 In 2016, total resources for HIV programmes actually decreased by 7%.85 In the midst of growing insecurity and disorder in the regions that have historically led in mobilising international financing for the HIV response (namely, North America and Europe), HIV seems less frightening than in earlier times. African leadership in the HIV response, so crucial to success under the MDGs, is also less visible. In a globalised world where attention spans are limited, the temptation to pretend that HIV is a problem that has been solved has proven to be powerful.

As the HIV response grapples with an uncertain future and works to identify optimal strategies for sustainability, it faces a pivotal challenge in defining, for the long-term, its relationship to the global health field. Appropriately integrating HIV within broader health systems will probably be essential to achieve ambitious global HIV aims, sustain treatment access in decades to come, and spread costs associated with controlling the epidemic. However, there are genuine risks to wholesale relinquishment of the exceptionalist approach to HIV. Notwithstanding the many criticisms of vertical health programmes, there is little dispute that HIV exceptionalism has worked, mobilising extraordinary new financial, technical, and human resources, uniting diverse stakeholders, focusing global attention on concrete results, driving and benefiting from scientific innovation, and engaging communities in far-reaching ways. Abandonment of an approach that has been groundbreaking in its success should not be done without a rigorous interrogation of the risks and benefits of mainstreaming the HIV response into national health systems.

Heeding the lessons of the HIV response

Even as the HIV response will inevitably depend on health and social systems to achieve its ambitious global target for 2030, lessons from the HIV response are also instructive for the future of global health. The UNAIDS-Lancet Commission on Defeating AIDS—Advancing Global Health in 2015 outlined the salient attributes of the HIV response that have contributed to its success and that should inform broader global health efforts. These include the sustained leadership of civil society and people living with HIV, the multistakeholder nature of the response, the extraordinary degree of political leadership for the fight against HIV, the centrality of human rights, gender equity, and social justice to the response, and a commitment to global and local-level accountability and transparency.6 Similarly pivotal has been the close link between scientific research and efforts to strengthen HIV programmatic efforts.

An emphasis on innovation has typified the HIV response from its earliest days and is in large measure responsible for bringing the world to the point where HIV as a medical problem can be effectively managed. Continuing research investments have made possible first-line HIV treatment regimens that are more durable, more tolerable, and less expensive than the regimens that have already saved millions of lives. Additional innovations that are anticipated in the coming years, including long-acting antiretroviral regimens for both HIV treatment and PrEP, are among the reasons for optimism that even greater progress against HIV is achievable in the coming years, including the ultimate goals of a preventive vaccine and a functional cure for HIV.

Infusing the HIV response with a renewed energy and sense of purpose will be challenging, but the future health and wellbeing of countless millions of people require that we meet this challenge. Decision makers must be made aware of the profound and indisputable humanitarian and economic stakes at play in the future of the HIV epidemic. While fully acknowledging the daunting challenges we face, the HIV community must reinvigorate itself and embrace the scientist-activist zeal that yielded such historic achievements.

Opportunities for integration and synergy in the global health and HIV responses

Linking global health and HIV responses more closely and integrally across health programmes and practice is hardly a new idea. Experience in integrating HIV in broader health systems underscores both the benefits and potential risks associated with a more integrated and less exceptionalist approach to HIV, illustrates the challenges confronting greater linkage and integration, and highlights potentially valuable opportunities to rethink further how the HIV response fits within the broader global health enterprise. This experience further shows that the options for future programmatic approaches to HIV are not confined to a binary choice between exceptionalism or wholesale integration, but rather that several opportunities exist in the immediate-term for more incremental integration and for learning by doing. In all cases, steps toward integration should be undertaken thoughtfully, retaining the key principles that have defined the HIV response.

People and communities

To advance the SDGs’ goal of leaving no one behind and addressing the needs of the most susceptible first, innovative and rights-based approaches are needed to realise the vision of sustainable health for all. The particular health needs of different populations, outlined here, illustrate diverse ways in which the HIV response and the global health field can benefit and learn from each other.

Children’s health: ensuring that every child has the best chance at healthy adulthood

Comparatively well funded and vertical disease programmes have had a clear effect on child health. Childhood vaccination programmes, including programmes supported by G AVI, the Vaccine Alliance, have generated exceptionally high and increasing rates ofimmunisation.39 Between 2000 and 2014, measles vaccination is estimated to have saved 17·1 million lives.86 Between 2010 to 2015, the mortality from malaria in children younger than 5 years decreased by 35%87 because of dramatic increases in the coverage of key malaria interventions.39

The HIV response illustrates both the potential of focused global action to improve the health of children as well as the persistent failures of health systems to address children’s needs. As the proportion of pregnant women living with HIV who receive antiretroviral medicines has increased, the incidence of new HIV infections in children has sharply decreased. In 2016, the 160 000 new HIV infections in children represented a 47% decrease since 2010, and a 66% decrease since 2005.1

By contrast, little progress has been made with respect to integrated interventions that rely on regular contacts with the health system. Comparing utilisation data for 2000–08 with that of 2009–14, met demand for family planning services increased only modestly, from 54% to 64%, the proportion of pregnant women who visited antenatal care at least four times increased only from 50% to 56%, the share of births with a skilled attendant increased only incrementally, from 55% to 65%, and similarly modest increases (less than 10%) were reported for exclusive breastfeeding, oral rehydration therapy, and care-seeking for pneumonia.39 Shortcomings in health systems that undermine health outcomes for children include weak laboratory systems, inadequate systems for monitoring mother-child pairs from antenatal to paediatric care settings, fragmented service delivery systems that invite discontinuity of care, and frequent drug stock-outs.

These deficiencies in health systems are evident with respect to HIV treatment for children. HIV treatment coverage in children (46% as of June, 2017) remains far lower than in adults (58%), resulting in notably higher morbidity and mortality in children than in adults.1 Although children accounted for 6% of all people living with HIV worldwide in 2016, they made up 12% of all AIDS-related deaths.1 The persistent coverage gap between children and adults has long been excused by complexities associated with diagnosing and treating HIV in children, including the need for virological testing to confirm HIV infection in children and the historic shortage of child-appropriate antiretroviral reformulations. However, as a result of technological advances in recent years, the means to address these complexities now include point-of-care early infant diagnostic testing platforms, innovative methods to reduce turnaround times for standard virological testing by remote central laboratories, and striking progress in optimising treatment options for children.

Effectively integrating service delivery for children will meet children’s health needs in a holistic manner and provide co-located services that are effective, efficient, and of good quality. Health-service integration for children spans not only the levels of care (eg, community, primary, and referral) but also the child’s life (pre-pregnancy to childhood). The Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Pneumonia is a valuable approach to service integration, providing a framework for coordinated and integrated actions to improve feeding and nutrition for infants and young children, access to safe drinking water and sanitation, hand washing with soap, reduction in indoor air pollution, immunisation, HIV prevention, and treatment of pneumonia and diarrhoea.88

Adolescent health

Health risks are especially acute for adolescent girls (figure 7). The risk of new HIV infections in women living in high-burden countries in sub-Saharan Africa peaks at age 15–24 years, about 10 years earlier than in their male peers, and AIDS persists as the fourth leading cause of death in adolescent girls and young women in sub-Saharan Africa.89 The disproportionate health burden in adolescent girls stems from a confluence of factors, including the persistently low socioeconomic status of women in many societies, lack of educational and economic opportunities, and sharply limited access to family planning and adolescent-friendly health services.

Figure 7: Sexual and emotional health in adolescents in India.

A young girl attends a candlelit march for sexual and emotional health for young teens in Udaipur, India. Credit: © 2016 Arvind Jodha/UNFPA, Photoshare.

One in four women worldwide become married before age 19 years, and 6% of women are married before age 15 years.90 Early marriage is linked with lower nutritional status, lower educational attainment, increased mortality for women,91 increased risk of HIV acquisition,92 intimate partner violence,93 and reduced health, nutritional status, and socioeconomic outcomes for their children.91

Particular risks are experienced by the estimated 21 million girls aged 15–19 years and the 2 million girls younger than 15 years who give birth each year.94 Pregnancy during adolescence increases the risk of complications, and childbirth is the leading cause of death in girls aged 15–19 years.91 Giving birth during adolescence also increases health risks for newborn children, including low birthweight, preterm delivery, and poor long-term developmental outcomes.95 Minimising health risks for adolescent girls, including but not limited to HIV infection, will rely on an unprecedented, well resourced, and multisectoral effort. Keeping girls in school, through cash transfers and other strategies, is an overriding priority.

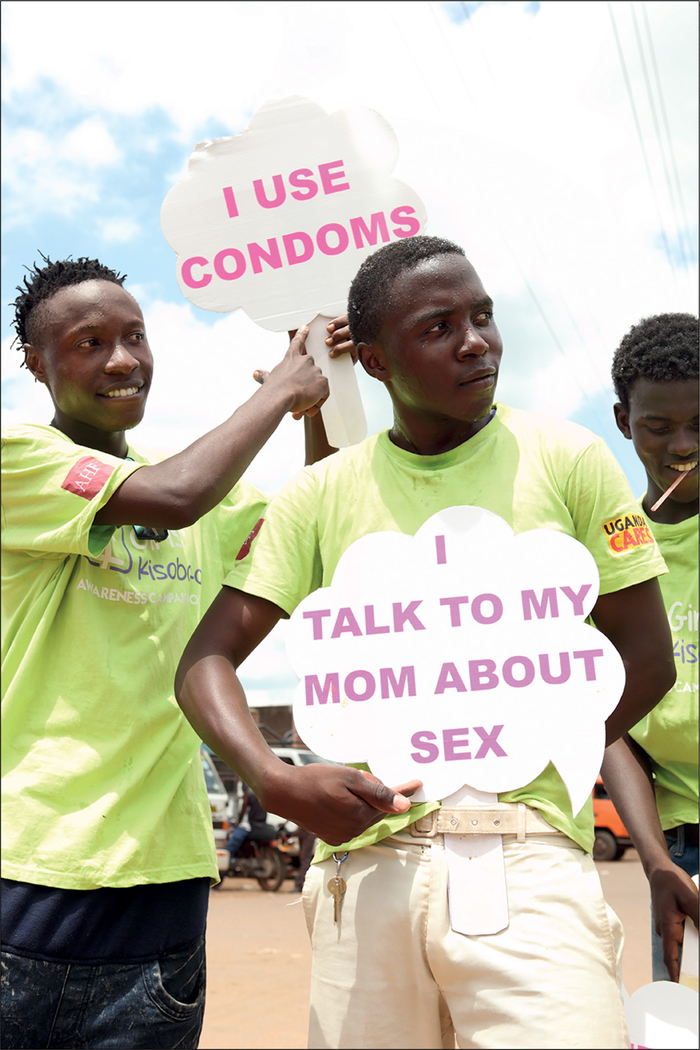

The HIV response has galvanised interdisciplinary work to clarify young people’s reasons for engaging in unprotected sex and effective means to reduce sexual risks. Data from extensive research have conclusively shown that abstinence is a failed strategy for HIV prevention.96 Effective prevention of HIV and sexually transmitted infections and advancement of broader sexual and reproductive health in young people necessitates evidence-based, tailored, flexible, and client-centred approaches to sexual harm reduction and comprehensive sexual education (figure 8).97 Ready access to contraception and other family planning services is essential because half of pregnancies in girls aged 15–19 years are unintended.98

Figure 8: HIV testing, family planning education and referrals, and deworming kits in Uganda.

A dance troupe with Public Health Ambassadors Uganda perform in the Kasana Market in Luwero to call attention to a pop-up health clinic providing HIV testing, family planning education and referrals, and deworming kits.

Credit: © 2016 David Alexander, Photoshare.

Changing lifestyles mean that an increasing number of adolescents are susceptible to the health risks associated with poor diet, tobacco, alcohol and substance abuse, malnutrition (including anaemia and obesity), and NCDs such as diabetes and cancer. In turn, these risks are associated with preventable mortality in adulthood. Mental health issues are among the top five causes of adolescent disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) lost, with more than 75% of mental illnesses originating before age 24 years.99

All adolescents have the right to accessible health services. Helping youth to prioritise health and engage in services is challenging when low mortality and good health is expected in young people, prior experience in health-care interaction is limited, and concern about confidentiality breaches is high.99 Among the key lessons learned in the HIV response is that health services must be tailored to young people’s needs and preferences and should offer an integrated combination of services. Integrated service packages must include comprehensive health checks relevant to adolescents and take into consideration other priorities such as education and economic opportunities, which, if unaddressed, lead to poor health and wellbeing.89

Achieving universal health coverage demands the availability of adolescent-focused health services in all health facilities and in other more accessible multipurpose spaces. Adolescent-friendly services offer operating hours outside of work or school, create a friendly and non-judgmental environment, engage peers in support functions, promote health in ways that appeal to young people, and use modern technologies and innovations already incorporated in the daily lives of adolescents.100,101

Meeting the needs of women

Women’s health needs often differ from those of men. Whereas breast cancer is not a leading cause of death in men, the breast is the most common site of cancer diagnosis in women (accounting for 25% of all cases in 2012).44 Cervical cancer is the fourth leading cancer diagnosis in women and the fourth leading cancer-related cause of death in women.44 Although maternal mortality has decreased, an estimated 830 women die daily from preventable causes associated with pregnancy and childbirth.102

In addition to heightened physiological vulnerabilities to many diseases and health conditions, women’s health risks are often closely linked with their unequal status in societies. For example, an estimated one in three women worldwide will experience physical or sexual violence, and those women who do are roughly twice more likely to experience depression or have an alcohol use disorder and 16% more likely to have a baby with low birthweight than those women who do not.103

Because of both increased physiological susceptibility to HIV acquisition during penile-vaginal intercourse and because of gender-related challenges in negotiating safer sex, women are especially susceptible to HIV, accounting for 56% of all people living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa.1 Women’s experience of intimate partner violence has been correlated with a 50% increase in the risk of HIV acquisition,104 and emotional abuse by partners is linked with rapid progression of HIV disease in women.105

The HIV response has long joined forces with the broader women’s health agenda through political advocacy for gender equality, programmes to promote healthy gender norms, and strategies to prevent gender-based violence. At national, regional, and global levels, women living with HIV have organised networks to provide mutual support and to increase recognition of HIV as a women’s health issue. Substantial resources have been invested in condom programming and other interventions to reduce women’s sexual risks and in research to develop prevention methods that women can control on their own.

The successful global scale-up of ART in women has shown the feasibility of achieving broad access to care for women. Among people living with HIV, women are more likely than men to know their HIV status, receive ART, and achieve viral suppression.5 The proportion of pregnant women living with HIV who receive effective antiretroviral medicines increased from 47% in 2010, to 76% in 2016.5

There is growing recognition that the women’s health agenda must move beyond its traditional focus on sexual and reproductive health and tackle women’s growing burden of NCDs.105 The Pink Ribbon Red Ribbon partnership, working in six countries in sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America, aims to leverage momentum and infrastructure from the HIV response to reduce the cancer burden in women. Through the third quarter of 2017, the partnership reported that it had screened more than 465 000 women for cervical cancer and more than 34 000 women for breast cancer, administered the vaccine for human papillomavirus to nearly 148 000 girls, and provided treatment services to almost 30 000 women diagnosed with cervical cancer.106

The gender gap in health: services for men

Health outcomes are consistently worse in men than in women. In 2015, mean life expectancy was 5·8 years higher in women than in men (74·8 years [uncertainty interval 74·4—75.2] for women vs 69–0 [68·6–69·4] for men), and this gender gap in life expectancy is increasing over time.107 These patterns are vividly reflected in HIV-related outcomes; in 2016, men accounted for less than half of all adults (>15 years) living with HIV but for an estimated 58·4% of AIDS-related deaths.1

A key driver in gender differences in health outcomes appears to be men’s comparatively lower utilisation of health services. In a national survey in 2013,108 men in the USA were markedly less likely than women (72% vs 86%) to report a regular source of care or to report having seen a health-care provider in the previous 2 years (75% vs 91%). Across regions, men are consistently less likely than women to know their HIV status, to receive ART, and to remain engaged in care once they initiate HIV treatment.5

In many countries, especially in LMICs, the best developed health-service delivery platforms (eg, antenatal, maternal, paediatric, sexual and reproductive services) are often designed primarily for use by women or children, or both. In many settings, few, if any, health-service delivery channels have been developed specifically with men in mind. This has led to the common belief that clinics are not meant for men,109 deterring men from accessing health services. Often, health services are accessible only during working hours, further discouraging male workforce participants from obtaining the services they need. Popular notions of masculinity might also disfavor receipt of health services as a sign of weakness.110

In view of the severe gender gap in health, it is striking how little attention the HIV response or the global health field has given to men’s health issues. To close the gender gap, decision makers must expressly value men’s lives and prioritise action to increase men’s access to and use of health services. In the case of HIV, a growing body of evidence suggests that community-centred programmes that specifically work to engage men and address their needs and preferences (including flexible clinic hours, mobile services, workplace programmes, and private access) can effectively diminish the gender gap in men’s utilisation of health services.111 To reach nearly 15 million men with voluntary medical male circumcision in 14 African countries in 2008–16, and thereby avert more than 500 000 new HIV infections through 2030,60 circumcision programmes worked with men and local communities to forge new social norms, offered services at hours that corresponded to men’s needs, used a variety of service delivery approaches (eg, mobile outreach), and integrated circumcision services with multiple other health services.112

Innovative service models could diminish or eliminate gender gaps in HIV service utilisation (figure 9). SEARCH, a community-centred research project in 32 rural communities in Kenya and Uganda, integrated HIV testing in multidisease health fairs and used innovative approaches to deliver ART through co-located services. To help avoid a gender gap in testing utilisation, SEARCH created men-only discussion groups that invited men to discuss HIV and sexual health issues. After 2 years of the intervention, gender gaps across the 90–90-90 cascade had effectively disappeared, with men achieving the first two 90s and 88% viral suppression.113

Figure 9: HIV testing services in Kenya.

A counsellor provides HIV testing services to livestock herders during community outreach services in the Eremit area of Kajiado County, Kenya. Credit: © 2012 George N Obanyi/FHI 360, Photoshare.

People who inject drugs

One of the great ironies with respect to the prohibitionist approach to substance use, which treats drug use primarily as a law enforcement and national security matter and continues to have widespread and negative implications for HIV114 and global health more generally, is that it was initiated in the name of public health. A further irony is that these failed policies also spawned one of the most successful of all HIV prevention strategies. Harm reduction is a practical and rights-based approach that aims to mitigate the negative consequences of behaviours, including when cessation of the behavior is infeasible or not desired by the individual. This approach has potential applicability to a host of health problems beyond blood-borne pathogens such as reducing alcohol-related problems, minimising road trauma, and preventing skin cancers. Harm reduction needs be seen as a core global health promotion strategy.

For prevention of HIV and viral hepatitis, harm reduction has traditionally referred to a range of services that include the provision of clean needles and syringes (NSPs). Combined with access to medication-assisted therapy (MAT), NSPs continue to be the most effective strategy to reduce new HIV infections in people who inject drugs. Harm-reduction services have the added public health benefit of facilitating linkages to other HIV-related services, drug treatment, and primary health care. Harm reduction is increasingly being adopted in diverse settings, although large gaps in the scale and coverage of harm-reduction programmes limit the ability of many countries to halt HIV and HCV epidemics.115 The USA, long a leading proponent of the global war on drugs, appears poised to undertake a rapid expansion of MAT in response to a surge in opioid addiction, offering potential opportunities to alter the global discourse on harm reduction.

To reduce the negative consequences associated with drug use, expansion of harm-reduction services also needs to be coupled with broad-based reform of laws and policies. Incremental progress has been made in reforming UN drug conventions to incorporate certain health and human rights considerations, but a wholesale paradigm shift in the global approach to drug use has yet to occur.116 Needed legal reforms (eg, decriminalisation, proportional sentencing, or diversion to health and social services for non-violent offenders) will not only facilitate greater access to health and social services for susceptible communities but also sharply reduce prison populations. Reductions in the prison population might free up resources for scaling up ART, drug treatment, and primary health care in prison settings and reduce the incidence and risk of infectious diseases. In pursuing locally tailored drug policy reform, nation states and states within nation states can help build a compelling evidence base that can guide and inform reform efforts, unlock new efficiencies in prison systems, and build new constituencies for drug policy reform. To transcend polarising political debates that have limited its support, harm reduction itself needs to expand and mainstream its ethos and more integrate its application beyond drug use across a wider spectrum of stakeholders and public health issues.

Gay and bisexual men

In 2016, 12% of all new HIV infections worldwide and 22% of all incident infections outside sub-Saharan Africa were in gay men and other MSM.117 Among HIV risk behaviours, HIV acquisition from condomless and receptive anal intercourse is twice more likely than from needle sharing during injecting drug use and more than 17 times more likely than from receptive penile-vaginal intercourse.118

However, gay men’s disproportionate HIV burden cannot be disentangled from their profound (and in many settings, worsening) social disadvantages. In 2017, more than 70 countries criminalised consensual same-sex relations,119 and the legal and policy barriers confronted by gay men have only increased in recent years, including through enactment of Russia’s so-called gay propaganda law and a draconian anti-gay law in Nigeria that went into effect in 2014. The past 2 years witnessed a sharp increase in the number of arrests of gay men in Indonesia120 and the forced closure of drop-in clinics providing HIV and other health and social services to gay men in Tanzania.121

Such a climate of fear and hostility inevitably increases gay men’s susceptibility to HIV and reduces their access to essential prevention and treatment services. In India and in Moscow, only a small minority of gay men living with HIV have achieved viral suppression, with lack of knowledge of HIV status serving as the most serious service bottleneck.122,123 Coverage of PrEP, a potentially transformative prevention tool for gay man and other marginalised populations, is only minimal outside of high-income countries.5

A crucial barrier to a more effective HIV response for gay men (and an unfortunate reflection of the neglect of gay men’s needs) is the shortage of robust evidence for action in this population. Although findings from focused studies continue to demonstrate extraordinarily high HIV prevalence and incidence in gay men in broadly diverse settings, evidence on gay men from standard surveillance systems is extremely limited, primarily because these systems focus on adults of reproductive age, especially in high-burden settings. Many countries still have no estimates of the size of the gay population, and half of those countries with estimations employ methodologies that call the reliability of these estimates into question.124

Migrants and the displaced

The number of people living in a country other than the one in which they were born (244 million in 2015) is larger than the population of all but four countries.125 In addition to cross-border migration, many people move for work or other reasons to different states or provinces within their own country; In China alone, this affects more than 280 million rural migrants.126 Worldwide, the migrant population includes 65·6 million forcibly displaced people, 22·5 million refugees, and 10 million stateless people.127

Addressing the health needs of the world’s massive and growing population of migrants is a health and human rights imperative.128 However, public health insurance schemes often exclude or limit services for migrants, especially for those who are undocumented. In part through regional cooperative compacts, more countries are taking steps to introduce health insurance approaches that explicitly cover migrants, yet implementation of these approaches remains incomplete129 and many migrant workers in such settings are unaware of the health benefits to which they are ostensibly entitled.130