Abstract

Objective

To determine whether observed changes in HIV prevalence in countries with generalized HIV epidemics are associated with changes in sexual risk behaviour.

Methods

We developed a mathematical model to explore the relationship between prevalence recorded at antenatal clinics (ANCs) and the pattern of incidence of infection throughout the population. To create a null model a range of assumptions about sexual behaviour, natural history of infection and sampling biases in ANC populations were explored to determine which maximised declines in prevalence in the absence of behaviour change. Modelled prevalence, where possible based on locally collected behavioural data, was compared to the observed prevalence data in urban Haiti, urban Kenya, urban Cote d'Ivoire, Malawi, Zimbabwe, Rwanda, Uganda and urban Ethiopia.

Results

Recent downturns in prevalence observed in Kenya, Zimbabwe and Haiti, like Uganda before them, could only be replicated in the model through reductions in risk associated with changes in behaviour. In contrast, prevalence trends in urban Cote d'Ivoire, Malawi, urban Ethiopia and Rwanda show no signs of changed sexual behaviour.

Conclusions

Changes in patterns of HIV prevalence in Kenya, Zimbabwe and Haiti are quite recent and caution is required because of doubts over the accuracy and representativeness of these estimates. Nonetheless, the observed changes are not consistent with behaviour change not the natural course of the HIV epidemic.

Keywords: Epidemiology, HIV, Prevalence

Introduction

HIV prevalence amongst women attending antenatal clinics collected over time from the same sites is fundamental to estimating the scale of the epidemic. The interpretation of trends in prevalence is important in understanding changes in population level risk but is complicated by the need to distinguish between the expected natural history of the epidemic and more pronounced changes arising from changes to individuals' sexual behaviour (1). In the case of Uganda and Thailand this has been possible and changes in the prevalence of HIV have been accepted to be the product of widespread alterations in sexual risk behaviour (2-5). These national success stories have had profound implications for global policy on HIV control leading to the development of prevention strategies and the investment of significant resources (6, 7). When the downturn in prevalence was first detected in Uganda the belief that behaviour change was responsible was strengthened through comparing observed prevalence trends with those generated by mathematical models with and without changes in risk behaviour (2).

Mathematical models are a precise way of describing assumptions about the transmission dynamics of an infectious disease and can be used to generate predictions. It is possible to generate predictions of HIV prevalence with and without behaviour change and test which predictions are consistent with observed patterns of prevalence. Models of HIV transmission dynamics have a long history and many complexities have been explored, including the impact of variation in risk behaviour (8) patterns of disease and infectiousness over time (9) and the impact of details of the dynamic network of sexual behaviour. However, models have also been developed to explore specific questions such as the impact of HIV on demography (10), the impact of particular interventions like hypothetical vaccines (11, 12) and the importance of particular network parameters (13). However, such models are best developed in a step wise fashion testing the importance of each particular assumption, and for simplicity the model should be parsimonious and include only as much detail as is relevant to the question in hand (14). In developing models to explore the potential changes in HIV prevalence it is important that they contain the assumptions that can impact on the results of interest.

In this supplement trends in HIV prevalence and associated evidence from sexual behaviour surveys from a number of countries have been described and interpreted. Such interpretation will be strengthened through a comparison of predicted trends under a range of assumptions in mathematical models. Because the data in antenatal clinic populations are obviously from women and include records of age, comparable model predictions should be sex and age structured. Other key elements to explore are the relationship between incidence and prevalence and the speed and variance in patterns of incidence and subsequent mortality (15). Further, while an exact description of the pattern of sexual behaviour is unnecessary, it is important to explore changes in the distribution of sexual risk behaviours resulting from differential AIDS associated morbidity and mortality in order that they can be distinguished from ‘exogenous' changes brought about by interventions (16). Another factor which can alter the trends in prevalence is changes in fertility and presence in ANC clinics over time (17).

Here we describe the expected dynamics of a generalised HIV epidemic using a newly developed mathematical model, and compare the prevalence data from countries included in this report with model predictions. Where the model can reproduce the observed changes in prevalence with ‘endogenous’ changes only (i.e. those caused by HIV and AIDS natural dynamics) then it cannot be argued from the data that the population level risks of HIV infection have been altered by the adoption of safer sexual behaviour. On the other hand, if the model cannot reproduce the observed epidemiological trends without also assuming changes in risk behaviour then this provides evidence that the proximate determinates of HIV incidence have been altered through an adoption of safer sexual practices.

Methods

Mathematical Model

A deterministic mathematical model of the heterosexual transmission of HIV in a sex, age and sexual-activity (defined according the rate of sexual partner change) stratified population, based on earlier published models (17) was developed. To focus on trends in prevalence in young women attending antenatal clinics the model included a detailed yearly age structure of young adults allowing changes in ages of sexual debut and rates of partner change in those recently entering the sexually active population. Full details of the model can be found in supplementary material but the key assumptions in the model are described here. HIV is assumed to be transmitted sexually at the formation of a sexual partnership or at the time of birth from an infected mother to her child. The population is divided into five sexual activity groups with different numbers of sexual partnerships formed per year. On sexual debut most individuals enter the group with the lowest sexual activity, but a minority enter groups with much higher sexual activity. In response to differential mortality two assumptions are possible: first the highest sexual activity groups can be depleted if those with high risk suffer greater mortality; second the relative sizes of the groups are maintained by recruiting individuals from other sexual activity groups into the higher activity groups.

An individual of a particular sex, age and sexual activity forms a number of sexual partnerships each year with partnerships preferentially directed between older men and younger women and with individuals of the same sexual activity class. Transmission of HIV is assumed to be prevented by consistent condom use with the probability of consistent use dependant on the age of both partners. To represent the long and variable incubation period and the higher transmission probability associated with initial and later stages of infection, those infected progress through three stages of asymptomatic infection prior to AIDS: a first stage lasting 3 months with a high transmission probability; a second stage lasting several years with the lowest transmission probability; and a third stage lasting 6 months with a high transmission probability. A model scenario with no exogenous behaviour change was compared with one where behaviour change was assumed to reduce the rate of sexual partner change or the transmission probability (through increased condom use). Where behaviour data were available (using the same indicator in successive surveys) this was used to estimate the change in parameter values for an alternative run of the model. If no such data were available a stepwise change in the transmission probability per partnership was used instead.

From each country the following data were sought for model parameterisation: median age at first sex for males and females, age-specific use of condoms (at last sex/with non-regular partner), age-specific mean number of sexual partners in last year and age of spouse or last partner. These population averages fail to specify some of the details of individual behaviour required to fully parameterise the model. To overcome this lack of detail in country wide data we used detailed sexual behaviour data from a household based population survey in rural Zimbabwe (18) to specify the heterogeneity in sexual partner change rates and the dependency of condom use on age of both partners. For each country all values were altered to generate the observed averages. The mean age difference between sexual partners was estimated by either the mean age difference between spouses or the difference in the median age of marriage between men and women. Where no data were available default model parameters were based on rural Zimbabwe data (18), with the exception of partner acquisition rates as a function of age which were based instead on observed patterns reported in Cote D'Ivoire for 1994 (ref). All simulations were run using a common demographic background rates (19) such that in the absence of infection the population would grow at approximately 4% per year and life expectancy at birth for males and females is 52.1 and 54.7 respectively. The behaviour data used to parameterise the model is summarised in Table 1 and sources are identified in the supplementary material. All model parameters are listed in Tables S1-S6 in the supplementary material.

Table 1.

Behavioural parameters used in the model.

| Haiti | Kenya | Zimbabwe | Uganda (N, C, W)* | Uganda (E)* | Ethiopia | Cote d'Ivoire | Malawi | Rwanda | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline settings | |||||||||

| Age at first sex (Males) | 18 | 17 | 17† | 17 | 17 | 20 | 18 | 18 | 17† |

| Age at first sex (Female) | 19 | 17 | 17† | 17 | 17 | 16 | 16 | 17 | 17† |

| Probability of consistent condom per partnership (male<24 with female<24) |

0.09 | 0.29 | 0.06 | 0.42 | 0.42 | 0.11 | 0.27 | 0.32 | 0.32† |

| Mean age difference between partners (male age minus female age) |

6.4 | 5.4 | 7.3† | 7.3† | 7.3† | 7.3† | 8.6 | 5.8 | 7.3† |

|

Behavioural changes (year implemented) | |||||||||

| Probability of HIV transmission (proportionate reduction). |

n/a | n/a | 50% (2000) |

75% (1990) |

80% (1994) |

n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Delay in age at first sex, males (years). |

n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Delay in age at first sex, females (years). |

n/a | +1 (1999) | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Number of sexual partnerships per year (proportionate reduction) |

10% (1995) |

F‡ 30% (1999) M‡ 26% (1999); 0.80 (2001) |

n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Probability of consistent condom per partnership (proportionate increase) |

100% (1995) |

n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

denotes that the default parameter was used in place of country-specific data.

F-Females, M-Males.

Uganda sites were provided separately as N-Northern (St Marys Hospital, Lacor, Gulu), C-Central (St Francis Hospital, Nsambya, Kampala), Western (Mbarara Hospital,), E-Eastern (Jinja Hospital and Mbale Hospital). Sources for behaviour data are listed in the supplementary material.

A brief summary of the HIV prevalence data used follows: Haiti Five urban ANC site from 1993 to 2003 (ref Haiti paper); Kenya Thirteen urban ANC sites from 1990 to 2003 (ref Kenya paper); Zimbabwe Nationwide ANC sites from 2000 to 2004 (Genscreen test)(ref Zimbabwe paper); Cote d'Ivoire Ten urban sites from 1997 to 2002; Malawi Nineteen nationwide sites from 1996 to 2003 (ref Malawi paper); Rwanda Twenty-four nationwide ANC sites in 2002 and 2003 (ref Rwanda paper); Uganda Five ANC sites from 1992 to 2002 (St Marys Hospital, Lacor, Gulu (northern Uganda), St Francis Hospital, Kampala (central Uganda), Mbarara Hospital (south western Uganda), Jinja Hospital (eastern Uganda) and Mbale Hospital (eastern Uganda) (ref Uganda paper); Ethiopia Urban sites from 2001 to 2003. To avoid trends in prevalence reflecting changes in the population sampling only data collected from the same antenatal clinics over time were included in our analysis. Where sample sizes were available we could construct 95% confidence intervals around the prevalence estimates. If such data were not available we arbitrarily include a 3% uncertainty interval.

The predicted growth in the prevalence of HIV from the model was roughly matched to prevalence by adjusting the transmission probability per sexual partnership and the assortativeness of mixing between the high and low sexual activity groups. Other model parameters values were chosen to maximise the natural decline in HIV prevalence and create a robust‘null model’ of trends without extrinsic behaviour change. These assumptions are outlined in the results. If the recorded changes in prevalence could not be reproduced without assuming changes in sexual behaviour, step-wise changes in behavioural parameters were made to reflect the trends in sexual behaviour observed in successive surveys. These changes were included at the time points between the surveys giving a likely match between the model and the data.

Results

The aim of modelling the transmission dynamics of HIV here was to predict the course of the epidemic in the absence of behaviour change. This allows us to exclude the natural history of the epidemic in interpreting any observed reductions in prevalence. For a conservative analysis we need to adopt assumptions that maximise the predicted declines in prevalence.

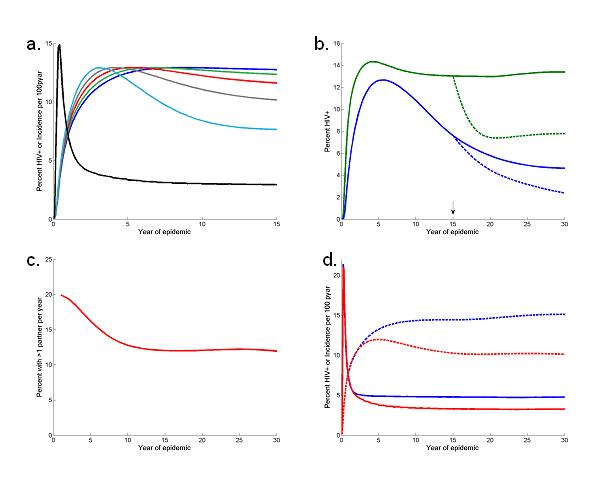

As HIV spreads first among those with the highest risk of acquiring infection incidence increases sharply, but as those high-risk individuals die the risk of infection they pose to others is removed so that incidence may subsequently decline. (Figure 1(a)). A prevalence decline ten to twenty years into the epidemic could be the product of that historic reduction in incidence or a more recent reduction in incidence associated with the deliberate adoption of safer sexual behaviour. Understanding the determinants of that initial decline in incidence and how it influences later trends in prevalence is crucial in our analysis. The rapid local“saturation” of those at highest risk is a consequence of the extreme variance in sexual activity within the population (10, 20, 21) with the majority forming few new sexual partnerships each year and a minority forming very many more (10, 22, 23). Soon after the infection is introduced to the population those individuals with riskiest sexual behaviour become infected, especially if there is a high transmission probability of the virus in those recently infected (Figure 1(a)). Subsequent infection mainly occurs in those with lower risk sexual behaviour and the number of new cases and the risk per susceptible decreases (24). Whether this initial decline in incidence generates a subsequent fall in prevalence is determined by how closely incidence and prevalence are coupled, i.e. the interval between infection and death (20). A long interval leads prevalence to record information about the risk experience accumulated over many years with the early reduction in incidence not manifest, but a shorter interval allows prevalence to follow the drop in incidence more closely (15) (Figure 1(a)). The relationship between prevalence and incidence is easier to interpret in young people because infections will have been acquired recently as they have only recently become at risk (as they begin sexual activity). Thus, in young adults prevalence is more a reflection of the current pattern of HIV transmission and is less influenced by deaths amongst those infected. Changes in prevalence following the adoption of safer sexual behaviour should appear first and most clearly among young people (25) (Figure 1(b)).

Fig 1.

Natural dynamics of generalised HIV epidemic.(a) Predicted HIV incidence per 100 person-years at risk (black line) and HIV prevalence amongst adult females for varying periods from infection to death: for 25 year-olds mean interval infection until death is 11 years (dark blue), 9 years (green), 7 years (red), 5 year (grey) and 3 years (light blue). (b) HIV prevalence amongst women aged 20-24 years (green line) and 30-35 years (blue lines) without behaviour change (full lines) and with the transmission probability halving at year fifteen (dashed lines). (c) The proportion of men and women currently forming more than one sexual partnerships per year,(d Predicted HIV incidence per 100 person-years at risk (full lines) and HIV prevalence amongst women (dashed lines) with the relative size of sexual activity groups being allowed to change freely (red lines) and being held constant with recruitment to the high activity groups from lower activity groups (blue lines).

Following the initial growth of an HIV epidemic, and as those with riskiest sexual behaviour who are infected die or reduce their sexual activity due to illness, the structure of the sexual network could begin to change; both because the high risk behaviour itself is lost, and because the opportunity for other individuals to form high risk partnerships is removed. This depends upon how an individual's risk behaviour changes as they age and the change in risk behaviour of those that remain following the deaths of those most at risk. At one extreme, if individuals remain at the same level risk throughout their life average sexual behaviour naturally becomes safer as those with risky behaviour die (Figure 1(c)). For this reason, changes in average sexual behaviour should be interpreted with some caution since the safer average behaviour may not be a consequence of the deliberate adoption of safer behaviours (20, 26). In the model it is possible to assume that as the number of high-risk individuals declines less risky individuals can adopt higher risk behaviour to keep constant average rate of partner acquisition. In this case, incidence remains high and may balance the surge in AIDS-related mortality, maintaining a steady prevalence of infection (Figure 1(d)).

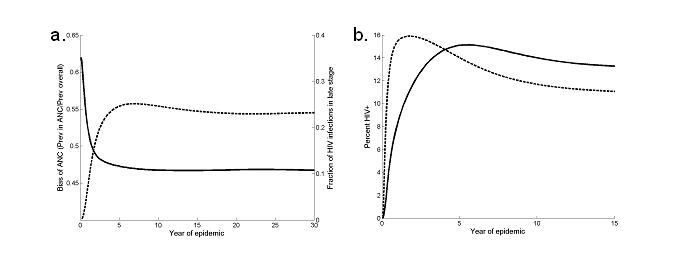

In interpreting trends in HIV prevalence we also need to be concerned with changing biases in the ANC population as a sample of women (27). First, reductions in fertility caused by the progression of HIV infection could exaggerate the decline in prevalence seen in the ANC sample relative to the general population. Recent data suggest that fertility is suppressed before the final stages of HIV infection (28, 29)). Simulations show that this sub-fertility and exclusion from the ANC sample of those infected will occur rapidly (Figure 2(a)). Second, the ANC sample might over-represent the women most likely to be infected with HIV, since sexual behaviour that exposes the women to the infection (e.g. unprotected sex) also exposes the women to the risk of pregnancy (27). Because prevalence among high risk women rises quickly and falls steeply an ANC sample may represent the extreme changes in prevalence (Figure 2(b)).

Fig 2.

Biases in ANC sample. (a) Ratio of percent of females attending ANC who are HIV+ and percent of all adult females HIV+, assuming that the probability of women being included in the ANC sample depends stage of HIV (sold line) and the fraction of HIV cases in late stage of infection (tertiary stage or full-blown AIDS) (dashed line). (b) Percent females attending ANC who are HIV+ (dashed line) and percent of all females HIV+ (full line), assuming that the probability of being included in the ANC sample depends on sexual activity group.

Our exploratory analysis found that the most extreme natural declines in prevalence arise from the greatest contrast between the initial peak and subsequent low incidence level, and from the shortest period from infection to death. Within reasonable limits we maximise the initial heterogeneity in rate of sexual partnership formation and the variation in transmission probability with stage of HIV infection. The acute peak in incidence reflects a lack of geographic space, stochastic effects and waiting times between sexual partnership formation and HIV transmission. These all distribute the peak in incidence over time and lessen the predicted prevalence decline (results not shown). Prevalence declines most when there is no compensatory recruitment into the high sexual activity groups in response to differential mortality and appears most extreme when assuming that the ANC over-samples high risk individuals. All model parameters are listed in tables S1-6 in the supplementary material.

In the case of Uganda, urban Kenya, Zimbabwe and urban Haiti, under a range of realistic and extreme assumptions (not all shown), our model can only replicate observed declines in prevalence by assuming that risk behaviour has also declined.

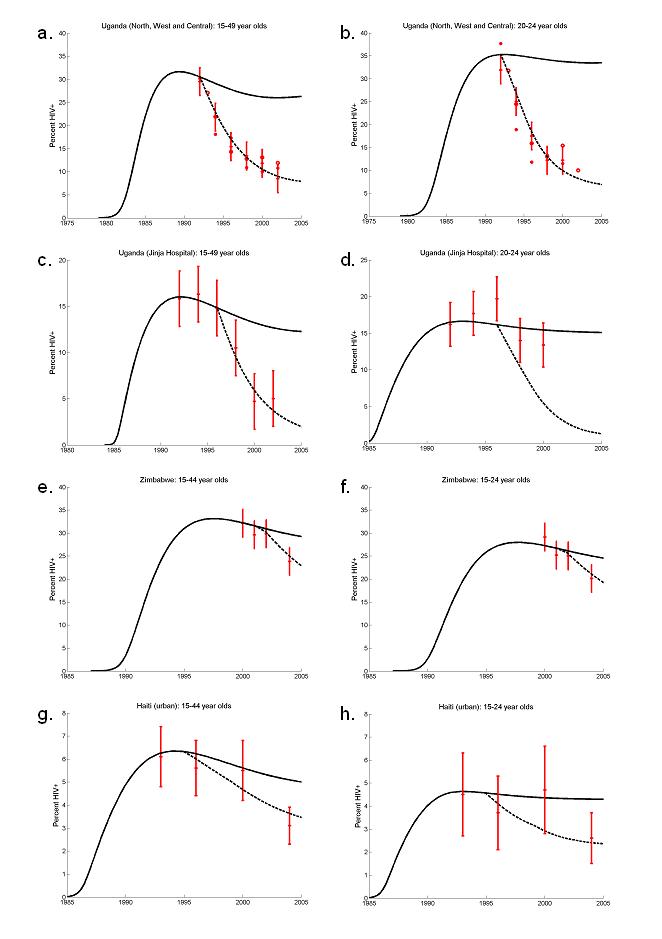

The decline in Uganda is the earliest and most researched (2, 3). Sites in the north, centre and west of the country have a similar epidemic curve with prevalence amongst 15-49 year-old and 20-24 year-old women both declining from approximately 30% to 10% (Figure 3(a-b)). These declines could be generated in our model with a reduction in the transmission probability of 75% in 1992 - a similar reduction to that previously estimated (2, 3). No subsequent reduction is necessary to generate the observed trends and the assumed change in risk predates observational cohort data from Rakai used to argue that incidence has not fallen (30). In Eastern sites (Jinja hospital and Mbale hospital) the decline prevalence in women aged 15-49 from approximately 15% to 5% (Figure 3(c)) is only possible with behaviour change, whereas prevalence estimates for women aged 20-24 show more fluctuations and are possible to model without risk behaviour changing (Figure 3(d)). Such seemingly contradictory results may arise from the greater error in prevalence estimates from a more restricted age group (sample sizes were not available to estimate confidence intervals), or from shifting behavioural parameters (in particular, age at first sex),which alter the distribution of the infection with respect to age, at the same time as overall prevalence is decreasing.

Fig 3.

ANC prevalence data (red crosses), model output assuming no behaviour change(full lines) and model output assuming behaviour change (dashed lines). Uganda: St Mary's Hospital, Lacor, Gulu, St Francis Hospital, Nsambya, Kampala and Mbarara Hospital (a) 15-49 years-olds and (b) 20-24 year-olds; Jinja Hospital (c) 15-49 years-olds and (d) 20-24 year-olds (error bars ± 3%). Zimbabwe: (e) 15-49 year-olds and (f) 20-24 year-olds, (error bars ± 3%). Urban Haiti: (g) 15-44 year old and (h) 15-24 year old (error bars ± 95% confidence intervals). Urban Kenya: Busia, Meru, Nakaru and Thika (i) 15-49 year-olds, and (j) 20-24 year olds, (error bars ± 3%); Garissa, Kisii, Kitui and Nyeri (k) 15-49 years old, and (l) 15-24 year olds.

In parts of urban Kenya HIV prevalence amongst women aged 15 to 49 fell from approximately 12% in 2001 to 9% in 2003 with a concomitant decline in those age 20-24 from 13% to 10%. The downturn in prevalence was particularly pronounced in four urban sites (Busia, Meru, Nakaru and Thika) where median prevalence fell from 28% in 1999 to 9% in 2003 among 15-49 year old women and from 29% in 1998 to 9% in 2002 among 15-24 year olds (Figure 3(i-j)). Again, to reproduce these changes requires assuming that risk behaviour has changed. Between behavioural surveys in 1993, 1998 and 2003 there were substantial reductions in the proportions of men and women having more than one sexual partner. Additionally, between 1998 and 2003, median age at first sex for females increased. To represent these changes in the model age-specific reductions of the mean rate of partner change were assumed in 1998 and 2001 and an instantaneous increase in females' age at first sex was included in 2001. The decrease in prevalence, though, is better matched with a reduction in the transmission probability of 70% in 1997 (blue dotted lines). Four other urban sites (Garissa, Kisii, Kitui and Nyeri) also experienced a reduction in median prevalence: 14% in 2000 to 7% in 2003 among 15-49 years old and same behaviour changes were assumed to bring the model into agreement with the data (Figure 3(k)). However, the trend in prevalence among 15-24 year olds is less clear and does not seem inconsistent with the null model (Figure 3(l)).

In Zimbabwe a decline in prevalence from 29% to 24% is recorded between 2002 and 2004 amongst 15-49 year-old women, and from 25% to 20% among women aged 15-24 year-old women (Figure 3(j)). In both cases, the observed cannot be reproduced through the natural evolution of the epidemic alone, but can be generated with if the overall probability of infection is reduced by half in 2001.

In urban Haiti, prevalence has decreased since 2000 from approximately 5.5% to 3% among 15-44 year women – a decline that could not be generated in the absence of behaviour change (Figure 3(e)). Among 15-24 year olds, prevalence has also declined although the uncertainty associated with these estimates not does rule out the possibility that prevalence has remained constant. In behavioural surveys there was a 20% decline in the mean number of sexual partners between 1994 and 2000 and condom use increased two- to threefold between 2000/1 and 2003. These changes were represented in the model by a step-change in partner change rates in 1994 and in condom use in 1999.

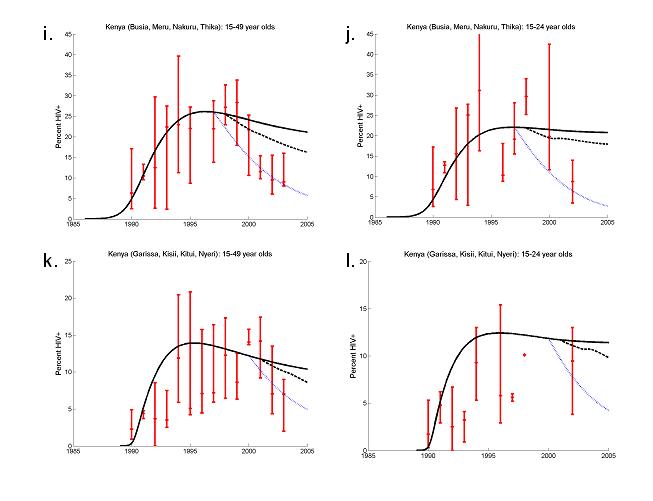

Adult prevalence (15-49 years) in urban Ethiopia fell from 14% in 2001 to 12% in 2003 (Figure 4(a)) and from 15% to 13% over the same time among 20-24 year olds (Figure 4(b)). These modest declines could be reproduced by the model without assuming any changes to sexual risk behaviour.

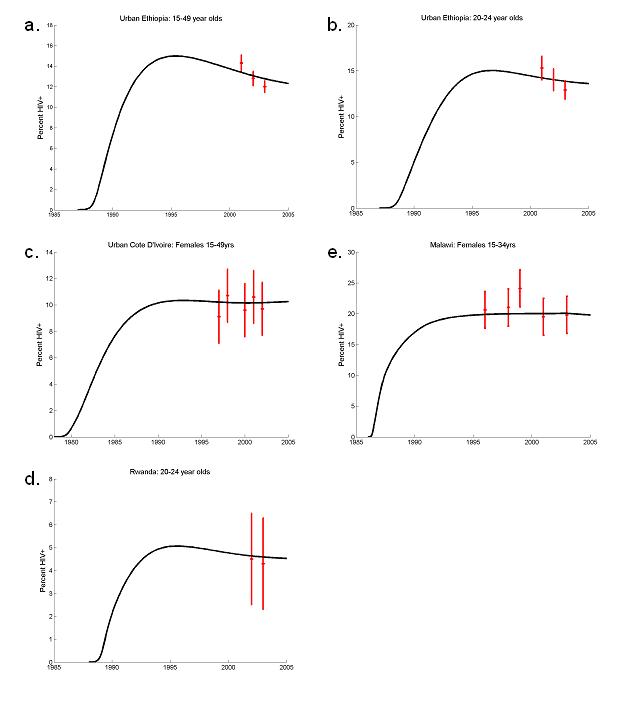

Fig 4.

ANC prevalence data (red crosses) and model output assuming no behaviour change (full lines). Urban Ethiopia: (a) 15-49 year olds, and (b) 20-24 year-old, (error bars ± 95% confidence intervals). (b) Urban Cote d'Ivoire 15-49 year-olds (error bars are ± 3%). (d) Malawi: 15-34 year olds (error bars are ± 3%).. (c) Rwanda 20-24 year-olds (error bars are ± 3%).

The data analysed from Malawi, urban Cote d'Ivoire and Rwanda show no sign of a decrease in prevalence amongst all adults, or selected age-groups (Figure 4(c-e)). There is some evidence that the fraction of men and women having had more than one or two sexual partners in the last twelve months has deceased in Malawi and Cote d'Ivoire (ref country papers).

Discussion

Our model illustrates the potential for HIV prevalence to decline without a deliberate adoption of safer sexual behaviours. However, the inability of the model to replicate the extent of the observed declines allows us to be more confident that changes in prevalence in Uganda, urban Kenya, Zimbabwe and urban Haiti are unlikely to be a product of these natural dynamics. The declines observed can be contrasted with urban Ethiopia where the prevalence patterns could be reproduced with sexual behaviour and HIV transmission remaining unchanged and urban Cote d'Ivoire, Malawi and Rwanda where aggregated prevalence has not recently decreased, although this does not exclude the possibility that behaviour change has had a significant impact on the HIV epidemic.

The model of HIV transmission is influenced by a large number of interacting variables which, without a dramatic increase in data sources, limits our ability to statistically fit the model and estimate the most likely value of particular parameters. A statistical interpretation of our results depends upon the confidence intervals around the prevalence estimates at particular time points and whether our extreme decline in prevalence falls within them. It should be noted that some of the prevalence estimates used here did not have reported sample sizes or statistical confidence intervals. In addition to statistical error, changing biases could lead to the observed and predicted trends separating. One such bias is suggested by recent data indicating that fertility is suppressed before the final stages of HIV infection (29). Sub-fertility in those with long standing HIV infection could lead to their exclusion from the ANC sample, but our model indicates that the effects of this bias will predate the declines in prevalence we are now observing. Nationally, estimates of prevalence often fall as samples are recruited from progressively remoter populations or as HIV tests become more specific. To avoid these problems we have only presented data from clinics consistently included.

Restricting HIV prevalence data to the younger age-groups often fails to help identify recent reductions in HIV incidence. In young age groups the confounding effects of mortality and sub-fertility on prevalence trends are minimised and reductions in incidence will be translated rapidly into reduced prevalence. However, the uncertainty associated with the prevalence point-estimates is often too great to detect trends. In contrast, although prevalence estimates from across all adult ages are prone to natural reductions, they may be determined more precisely and so allow trends due to the natural evolution of the epidemic and due to behaviour change to be distinguished.

One of the problems in reconstructing HIV epidemics is that current sexual behaviour already includes reductions in risky sexual behaviour brought about by the HIV epidemic and associated mortality in those who were previously at the greatest risk of infection. We are forced to assume that the heterogeneity in sexual partner change rates was originally greater than that observed today. Additionally, while we attempted a reconstruction of country specific epidemics, local patterns of risk were often not available, necessitating the adoption of standard patterns for condom use and age-specific partner change rates. Fortunately, despite being important for fitting age and sex-specific prevalence, these patterns have little bearing on the course of the epidemic once its magnitude is established.

In summary, our analysis supports a belief that behaviour change and decreased incidence is reducing prevalence in four countries with generalised epidemics. In all but Uganda the declines in prevalence are quite recent though the evidence of behaviour change in parts of Kenya is accumulating where several sequential HIV prevalence estimates have shown a continued decline. Although a substantial prevalence decline in Zimbabwe has only been detected recently, credence is lent to this observation by the increasing evidence of behavioural change (ref Zimbabwe paper) (26). The observed dip in prevalence in urban Haiti, on the other hand, could turn out to be anomalous. For a long time Uganda and Thailand (refs) have been the key national level examples of success in reducing HIV incidence and the main source of evidence on HIV prevention. Perhaps it is time for Kenya and Zimbabwe to be added to the list.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

TBH, SG and GPG thank The Wellcome Trust and UNAIDS for Grant support. GPG thanks the MRC for grant support.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interests

None declared.

Publisher's Disclaimer: The Corresponding Author has the right to grant on behalf of all authors and does grant on behalf of all authors, an exclusive licence (or non exclusive for government employees) on a worldwide basis to the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd to permit this article (if accepted) to be published in STI and any other BMJPGL products and sublicences such use and exploit all subsidiary rights, as set out in our licence (http://sti.bmjjournals.com/misc/ifora/licenceform.shtml).

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- 1.UNAIDS Reference Group on Estimates Modelling and Projections . Trends in HIV incidence and prevalence: natural course of the epidemic or results of behavioural change? Geneva, Switzerland: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kilian AH, Gregson S, Ndyanabangi B, Walusaga K, Kipp W, Sahlmuller G, et al. Reductions in risk behaviour provide the most consistent explanation for declining HIV-1 prevalence in Uganda. Aids. 1999;13(3):391–8. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199902250-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stoneburner RL, Low-Beer D. Population-level HIV declines and behavioral risk avoidance in Uganda. Science. 2004;304(5671):714–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1093166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nelson KE, Celentano DD, Eiumtrakol S, Hoover DR, Beyrer C, Suprasert S, et al. Changes in sexual behavior and a decline in HIV infection among young men in Thailand. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(5):297–303. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199608013350501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rojanapithayakorn W, Hanenberg R. The 100% condom program in Thailand. Aids. 1996;10(1):1–7. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199601000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.UNAIDS . 2004 Report of the global AIDS epidemic. Geneva: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Office of the United States Global AIDS Coordinator The President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief. U.S. Five-year global HIV/AIDS strategy. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson RM, Medley GF, May RM, Johnson AM. A preliminary study of the transmission dynamics of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), the causative agent of AIDS. IMA J Math Appl Med Biol. 1986;3(4):229–63. doi: 10.1093/imammb/3.4.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacquez JA, Koopman JS, Simon CP, Longini IM., Jr Role of the primary infection in epidemics of HIV infection in gay cohorts. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1994;7(11):1169–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson RM, May RM. Epidemiological parameters of HIV transmission. Nature. 1988;333(6173):514–9. doi: 10.1038/333514a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blower SM, McLean AR. Prophylactic vaccines, risk behavior change, and the probability of eradicating HIV in San Francisco. Science. 1994;265(5177):1451–4. doi: 10.1126/science.8073289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garnett GP. The basic reproductive rate of infection and the course of HIV epidemics. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 1998;12(6):435–49. doi: 10.1089/apc.1998.12.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morris M, Kretzschmar M. Concurrent partnerships and the spread of HIV. Aids. 1997;11(5):641–8. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199705000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anderson RM, Garnett GP. Mathematical models of the transmission and control of sexually transmitted diseases. Sex Transm Dis. 2000;27(10):636–43. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200011000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gregson S, Garnett GP, Anderson RM. Is HIV-1 likely to become a leading cause of adult mortality in sub-Saharan Africa? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1994;7(8):839–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boily MC, Lowndes CM, Gregson S. Population-level risk factors for HIV transmission and ‘the 4 Cities Study’: temporal dynamics and the significance of sexual mixing patterns. Aids. 2002;16(15):2101–2. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200210180-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garnett GP, Gregson S. Monitoring the course of the HIV-1 epidemic: the influence of patterns of fertility on HIV-1 prevalence estimates. Mathematical Population Studies. 2000;8(3):251–277. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gregson S, Nyamukapa CA, Garnett GP, Mason PR, Zhuwau T, Carael M, et al. Sexual mixing patterns and sex-differentials in teenage exposure to HIV infection in rural Zimbabwe. Lancet. 2002;359(9321):1896–903. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08780-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderson RM, May RM, Ng TW, Rowley JT. Age-dependent choice of sexual partners and the transmission dynamics of HIV in Sub-Saharan Africa. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1992;336(1277):135–55. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1992.0052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson RM, May RM. Infectious diseases of humans. Oxford university press; Oxford: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garnett GP, Anderson RM. Factors controlling the spread of HIV in heterosexual communities in developing countries: patterns of mixing between different age and sexual activity classes. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1993;342(1300):137–59. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1993.0143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spira A, N B, group atA . Sexual behaviour and AIDS. Avebury; Aldershot: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson AM, Wadsworth J, Wellings K, Field J. Sexual attitudes and lifestyles. Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baggaley R, Boily MC, White RG, Alary M. Systematic review of HIV-1 transmission probabilities in absence of antiretroviral therapy. In preparation. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zaba B, Boerma T, White R. Monitoring the AIDS epidemic using HIV prevalence data among young women attending antenatal clinics: prospects and problems. Aids. 2000;14(11):1633–45. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200007280-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gregson S, Garnett GP, Nyamukapa CA, Hallett T, Lewis JJC, Mason PR, et al. HIV decline assoiciated with behaviour change in eastern Zimbabwe. doi: 10.1126/science.1121054. submitted. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zaba B, Gregson S. Measuring the impact of HIV on fertility in Africa. Aids. 1998;12(Suppl 1):S41–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lewis JJ, Ronsmans C, Ezeh A, Gregson S. The population impact of HIV on fertility in sub-Saharan Africa. Aids. 2004;18(Suppl 2):S35–43. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200406002-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ross A, Van der Paal L, Lubega R, Mayanja BN, Shafer LA, Whitworth J. HIV-1 disease progression and fertility: the incidence of recognized pregnancy and pregnancy outcome in Uganda. Aids. 2004;18(5):799–804. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200403260-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wawer MJ. Declines in HIV prevalence in Uganda: not as simple as ABC; Twelfth Annual Retrovirus Conference; Boston. 2005.2005. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.