Summary

There is currently no comprehensive meningococcal vaccine, due to difficulties in immunising against organisms expressing serogroup B capsules. To address this problem, sub-capsular antigens, particularly the outer membrane proteins (OMPs), are being investigated as candidate vaccine components. If immunogenic, however, such antigens are often antigenically variable and knowledge of the extent and structuring of this diversity is an essential part of vaccine formulation. Factor H-binding protein (fHbp) is one such protein and is included in two vaccines under development. A survey of the diversity of the fHbp gene and the encoded protein in a representative sample of meningococcal isolates confirmed that variability in this protein is structured into two or three major groups, each with a substantial number of alleles that have some association with meningococcal clonal complexes and serogroups. A unified nomenclature scheme was devised to catalogue this diversity. Analysis of recombination and selection on the allele sequences demonstrated that the parts of the gene are subject to positive selection, consistent with immune selection on the protein generating antigenic variation, particularly in the C-terminal region of the peptide sequence. The highest levels of selection were observed in regions corresponding to epitopes recognised by previously described bactericidal monoclonal antibodies.

Introduction

Meningococcal disease, caused by the Gram negative bacterium Neisseria meningitidis, is an important cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, with most disease due to meningococci expressing one of five capsular polysaccharide antigens corresponding to serogroups A, B, C, Y and W135. Although serogroup B meningococci are a major cause of disease, particularly in industrialised countries (Jones, 1995; Pollard et al., 2001; Trotter et al., 2007), there is currently no vaccine against them due to the poor immunogenicity of the serogroup B capsular polysaccharide. This may be a consequence of its similarity to host antigens, which also raises concerns as to the safety of serogroup B polysaccharide as a vaccine component (Finne et al., 1983). A variety of sub-capsular cellular components, particularly outer-membrane proteins (OMPs), have been evaluated as possible alternative vaccine antigens (Jodar et al., 2002). These have included outer-membrane vesicle (OMV) vaccines that contain PorA, which have been used to target single-clone epidemics of meningococcal disease in Cuba, Norway, and New Zealand with some success (Bjune et al., 1991; O'Hallahan et al., 2005; Rodriguez et al., 1999). A major issue is the antigenic variability of OMPs, which complicates the development of vaccines with broad coverage. PorA, for example, has two major regions of antigenic variability (Russell et al., 2004) with 199 and 535 different peptide sequences in each region described by July 2009 (http://neisseria.org/nm/typing/fhbp).

Wider coverage against variable antigens can be attained by inclusion of multiple variants in vaccine formulations and multivalent PorA vaccines such as NonaMen have been developed (van den Dobbelsteen et al., 2007). For vaccine formulations such as this, it is necessary to have detailed molecular epidemiological information about the current and most frequently occurring strains in the population. Alternatively, more conserved antigens, such as Neisseria adhesin A (NadA) and Neisseria surface protein A (NspA) (Comanducci et al., 2002; Martin et al., 1997) and despite its variability (Rokbi et al., 2000), transferrin-binding protein B (TbpB) (Ala'Aldeen & Borriello, 1996) have been considered as candidates.

The vaccine candidate lipoprotein 2086 (LP2086) was discovered by an iterative process of immunisation following differential detergent extraction and protein purification (Bernfield et al., 2002; Fletcher et al., 2004). It was also identified Genome Derived Neisserial Antigen 1870 (GNA1870) (Masignani et al., 2003) by the technique known as ‘reverse vaccinology’ (Rappuoli, 2000). Subsequently it has been given the name factor H-binding protein (fHbp) because of its role in modulating the activity of the alternative complement pathway where it binds the regulatory protein factor H (fH) (Madico et al., 2006). fH has a critical role in maintaining homeostasis of the complement system and also, by attachment to host cells and tissue, preventing potential damage to them by inhibiting complement activation (Rodríguez de Córdoba et al., 2004). Several organisms, including Neisseria meningitidis mimic human tissue by recruiting fH and coating their surface, therefore avoiding complement-mediated lysis (Lambris et al., 2008; Schneider et al., 2006). In the case of the meningococcus, fHbp is the only receptor for fH on its surface (Schneider et al., 2009). The protein is present in all meningococci although levels of expression may vary in different isolates (Fletcher et al., 2004; Masignani et al., 2003). In comparison to other vaccine antigens, it is relatively sparse in its epitope surface-exposure in most meningococcal strains (Welsch et al., 2004). Expression of fHbp has been found to be key for survival in ex vivo human blood and human serum particularly in high-expressing strains (Seib et al., 2009; Welsch et al., 2008). Structurally, fHbp is a surface-exposed 29kDa globular lipoprotein composed of two β barrels connected by a short linker and is bound to the outermembrane by an N-terminal lipid anchor (Cantini et al., 2009; Mascioni et al., 2008; Schneider et al., 2009). Recent analysis of the fH-fHbp interaction indicate that the fH recognition site spans the whole surface of fHbp and that previously described bactericidal epitope sites do not lie in this region, but epitopes that bind to antibodies that affect fH binding are found around the edge of the site (Schneider et al., 2009).

The protein is a principal component of two recombinant protein vaccines in clinical trials at the time of writing. It is unique as a vaccine candidate in that it is able to elicit serum antibodies that activate classical complement pathway bacteriolysis and also prevent fH binding to the meningococcal cell surface thus making it more susceptible to bactericidal activity (Madico et al., 2006; Welsch et al., 2008). Like the related human-restricted organism Neisseria gonorrhoeae, there is specificity of binding to human fH (Granoff et al., 2009; Ngampasutadol et al., 2008). This may help to explain the higher bactericidal titres obtained when using vaccine-induced antibodies with rabbit complement versus human complement and also the organisms' exclusively human-related pathogenicity.

In the present study, variation of fHbp in a reference set of diverse meningococcal isolates was surveyed. The association of particular variants with clonal complex and serogroup was established, and the levels of recombination and selection acting on it were determined. Also, a novel, unified nomenclature scheme was developed that was independent of subfamily/variant and a Web-accessible database established to facilitate querying of sequences and submission of new allele sequences.

Materials and Methods

Isolates

The 107 meningococci surveyed were representative of bacteria isolated worldwide in the latter half of the 20th century, obtained from both patients with meningococcal disease and carriers (Maiden et al., 1998). Two previously published Neisseria gonorrhoeae protein sequences: YP_002793564, EEH61327 from Genbank were also used as part of the analysis.

Amplification of the fHbp gene and nucleotide sequence determination

Amplification of an approximately 900 bp region including the fHbp gene and immediately flanking regions was carried out using the Long 5UNI 2086 and 3UNI primer pair of primers (Fletcher et al., 2004). The PCRs were performed in 50 μl amplification reactions volumes using Taq polymerase (Qiagen) with 33 cycles of 95 °C for 50 s, 59 °C for 50 s, and 72 °C for 50 s with a final extension step of 72 °C for 7 mins. The amplicons were purified by 20% PEG/ 2.5 M NaCl precipitation and then used as templates for 10 μl dideoxynucleotide sequence reactions using BigDye Ready Reaction Mix (Applied Biosystems). Oligonucleotide primers specific for each of the subfamilies A and B were used to amplify internal fragments of the purified amplified gene products: (for subfamily A) 5′2086forseq (5′-TAT GAC TAG GAG CAA ACC TG-3′), 3′2086forseq (5′-TAC TGT TTG CCG GCG ATG-3′), 2086interforseq5′LA primer (5′-AGC TCA TTA CCT TGG AGA GCG GA-3′); (for subfamily B) 2086seq3′BLA primer (5′-TTC GGA CGG CAT TTT CAC AAT GG-3′) and 2086seqBinternal (5′-GGC GAT TTC AAA TGT TCG ATT T-3′). Cycling conditions were 30 cycles of 96 °C for 10 s, 50 °C for 5 s and 60 °C for 4 min. Separation of the labelled extension products was carried out on a 3730 capillary DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems) at the Department of Zoology Sequencing Facility, University of Oxford.

Analysis of sequence data

Assembly and editing of nucleotide sequence data was carried out using the Staden suite of software (Staden, 1996). Reformatted nucleotide sequences were visualised, aligned and translated manually using SeqLab, part of the GCG Wisconsin Package (Womble, 2000) (Version 10.3 for Unix (Accelrys Inc., San Diego, CA)). The alignment was based on amino acid sequence similarity with codon integrity maintained. A web-based front end to the NRDB program (written by Warren Gish, Washington University) was used to compare nucleotide and amino acid sequences to find those that were identical (http://pubmlst.org/analysis/).

The mega 3.1 program (Kumar et al., 2004) was used to calculate the overall mean distances as well as the within and between group distances for sequences using the Kimura 2-parameter model for nucleotide sequences and p-distances for amino acid sequences and also to produce distance matrix-based neighbour-joining trees. The reliability of the inferred trees was assessed by the bootstrap test with 2000 replications. mega 3.1 implements Felsenstein's bootstrap test evaluated using Efron's bootstrap resampling method. In the bootstrap test of phylogeny, a matrix of m sequences x n (nucleotides/peptides) are sampled with replacement (bootstrapping). These new sequences are reconstructed into a tree using the previously used phylogenetic method and the topology is compared to the original tree. This procedure is repeated 2000 times and the percentage of times a particular interior branch is the same between the original tree and the bootstrap tree is given. Boostrapping is a means of assessing confidence in a particular phylogeny and values are interpreted as the probability of interior branches being “correct” (generally 95% or higher).

The software package ClonalFrame Version 1.1, which implements a statistical model for inferring bacterial microevolution, was used for phylogenetic analysis and to identify regions likely to have undergone homologous recombination (Didelot & Falush, 2007). ClonalFrame performs inference in a Bayesian framework which assumes a standard neutral coalescent model whereby the bacteria in the sample come from a constant-sized population where each bacterium is equally likely to reproduce, irrespective of its previous history. The key assumption is that recombination events introduce a constant rate of substitutions to a contiguous region of sequence. Six independent runs, each with 250,000 iterations, 100,000 burn-in iterations and with every hundredth tree sampled, were used to derive a 75% majority-rule consensus tree. PAUP* version 4.0b10 for Unix (Swofford, 1998) was used to construct phylogenetic trees using the maximum-likelihood method. ClonalFrame and maximum-likelihood tree output were imported and further annotated in mega 3.1.

Associations between subfamily/allele and clonal complex/serogroup were analysed using the Fisher's exact test with Bonferroni correction applied as appropriate, with calculations performed with the R program version 2.7.1 (http://www.r-project.org/). Simpson's index of diversity (D) was used to assess the level of diversity of each subfamily/variant. It gives the probability that any two randomly selected individuals drawn from an infinitely large community belong to different species, or in the case of this study, isolates drawn from a population belong to different allele types (Hunter & Gaston, 1988; Simpson, 1949). The bias-corrected form of the formula used is as follows:

N = total number of isolates

n = total number of isolates of a particular genetic type

The value of the index ranges from 0 to one, meaning that the nearer to one the greater the diversity and the nearer to 0 the less the diversity. The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for these indices were calculated as described by Grundmann et al (Grundmann et al., 2001). Non-overlapping CIs indicate a significant difference in D.

Analysis of selection pressures

The START2 program (Jolley et al., 2001) (http://pubmlst.org/software/analysis/start2/) was used for tests of recombination by the Maximum Chi squared test and for selection using the ratio of nonsynonymous to synonymous nucleotide substitutions (dN/dS ratio). The OmegaMap program, which employs a Bayesian method to estimate the selection parameter ω (dN/dS) and the recombination rate ρ from gene sequences by use of reversible jump Monte Carlo Markov Chain (Wilson & McVean, 2006), was used to detect selection and recombination by inferring the posterior distributions of omega and rho along the gene. The means of the posterior distributions were used as a point estimates for omega and rho. The per-site posterior probability of positive selection was also used to summarize the posterior distribution of omega. Three independent OmegaMap runs each with 1,000,000 iterations and a thinning interval of 100 were compared to assess convergence and combined. Output from the OmegaMap runs was used to visualise possible selection acting on the sequence by means of fireplots and graphs indicating the posterior probability of positive selection along the sequence. Fireplots visualize the posterior on log(ω) or ω along the sequence using a colour gradient where a higher posterior density is represented by more intense colour (closer to white), and lower posterior density is represented by less intense colour (closer to red). These plots were produced using the R program version 2.7.1 (http://www.r-project.org/). The point estimate of ω, was used to colour a three-dimensional pdb file of the solution structure of a complex between a subfamily B/variant 1 GNA1870/fHbp protein and a region of the fH protein (Schneider et al., 2009) (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/home/home.do Protein Data Bank code 2W81).

fHbp Database

Unique nucleotide and peptide sequences were arbitrarily assigned allele numbers in order of discovery. A database was established containing these allele sequences obtained as part of this study, from direct submissions from collaborators or by interrogation of the GenBank database. AGDBNET antigen sequence software for web-based bacterial typing was used to do this (http://pubmlst.org/software/database/agdbnet/). It allows simultaneous BLAST querying of multiple loci using either nucleotide or peptide sequences (Jolley & Maiden, 2006).

Results

Diversity of fHbp gene and protein

The fHbp gene was found in all 107 isolates and among these, a total of 28 unique gene sequences encoding 27 different amino acid sequences were identified (Table 1). Unique peptide and nucleotide sequences were arbitrarily assigned allele numbers in order of discovery and entered into a database (http://neisseria.org/nm/typing/fhbp/), providing a comprehensive repository of reported fHbp diversity.

Table 1.

Study isolates and association with clonal complex, sequence type (ST), year, country, disease, serogroup, peptide, nucleotide allele and subfamily/variant.

| isolate name |

complex | ST | subfamily /variant |

year | country | disease | serogroup | peptide | allele |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 393 | ST-1 complex | 1 | SubB/v1 | 1968 | Greece | carrier | A | 4 | 4 |

| 20 | ST-1 complex | 1 | SubB/v1 | 1963 | Niger | invasive(unspecified/other) | A | 4 | 4 |

| 129E | ST-1 complex | 1 | SubB/v1 | 1964 | West Germany | invasive(unspecified/other) | A | 4 | 4 |

| 254 | ST-1 complex | 1 | SubB/v1 | 1966 | Djibouti | invasive(unspecified/other) | A | 4 | 4 |

| 106 | ST-1 complex | 1 | SubB/v1 | 1967 | Morocco | invasive(unspecified/other) | A | 4 | 4 |

| 6748 | ST-1 complex | 1 | SubB/v1 | 1971 | Canada | invasive(unspecified/other) | A | 4 | 4 |

| S5611 | ST-1 complex | 1 | SubB/v1 | 1977 | Australia | invasive(unspecified/other) | A | 4 | 4 |

| 79126 | ST-1 complex | 3 | SubB/v1 | 1979 | China | invasive(unspecified/other) | A | 38 | 37 |

| 79128 | ST-1 complex | 3 | SubB/v1 | 1979 | China | invasive(unspecified/other) | A | 38 | 37 |

| 371 | ST-1 complex | 1 | SubB/v1 | 1980 | India | invasive(unspecified/other) | A | 4 | 4 |

| 322/85 | ST-1 complex | 2 | SubB/v1 | 1985 | East Germany | invasive(unspecified/other) | A | 14 | 14 |

| 120M | ST-1 complex | 1 | SubB/v1 | 1967 | Pakistan | meningitis and septicaemia | A | 4 | 4 |

| 139M | ST-1 complex | 1 | SubB/v1 | 1968 | Philippines | unspecified | A | 1 | 1 |

| BZ 133 | ST-1 complex | 1 | SubB/v1 | 1977 | Netherlands | invasive(unspecified/other) | B | 4 | 4 |

| 890326 | ST-103 complex | 28 | SubA/v2 | 1989 | Netherlands | invasive(unspecified/other) | Z | 25 | 25 |

| NG P20 | ST-11 complex | 11 | SubB/v1 | 1969 | Norway | invasive(unspecified/other) | B | 5 | 5 |

| D1 | ST-11 complex | 11 | SubA/v2 | 1989 | Mali | carrier | C | 22 | 22 |

| M597 | ST-11 complex | 11 | SubA/v2 | 1988 | Israel | invasive(unspecified/other) | C | 22 | 22 |

| BRAZ10 | ST-11 complex | 11 | SubA/v2 | 1976 | Brazil | unspecified | C | 22 | 22 |

| F1576 | ST-11 complex | 11 | SubA/v2 | 1984 | Ghana | unspecified | C | 22 | 22 |

| 500 | ST-11 complex | 11 | SubA/v2 | 1984 | Italy | unspecified | C | 22 | 22 |

| MA-5756 | ST-11 complex | 11 | SubA/v3 | 1985 | Spain | unspecified | C | 67 | 54 |

| 90/18311 | ST-11 complex | 11 | SubA/v2 | 1990 | Scotland | unspecified | C | 22 | 22 |

| L93/4286 | ST-11 complex | 11 | SubA/v2 | 1993 | England | invasive(unspecified/other) | C | 95 | 92 |

| 38VI | ST-11 complex | 11 | SubA/v3 | 1964 | USA | unspecified | B | 98 | 95 |

| 860800 | ST-167 complex | 29 | SubA/v2 | 1986 | Netherlands | invasive(unspecified/other) | Y | 23 | 23 |

| EG 328 | ST-18 complex | 18 | SubB/v1 | 1985 | East Germany | invasive(unspecified/other) | B | 37 | 36 |

| EG 327 | ST-18 complex | 19 | SubA/v2 | 1985 | East Germany | invasive(unspecified/other) | B | 33 | 41 |

| 1000 | ST-18 complex | 20 | SubB/v1 | 1988 | USSR | invasive(unspecified/other) | B | 5 | 5 |

| 528 | ST-18 complex | 18 | SubB/v1 | 1989 | USSR | invasive(unspecified/other) | B | 37 | 36 |

| E26 | ST-198 complex | 39 | SubA/v3 | 1988 | Norway | carrier | X | 94 | 91 |

| A22 | ST-22 complex | 22 | SubA/v2 | 1986 | Norway | carrier | W-135 | 16 | 16 |

| 71/94 | ST-23 complex | 23 | SubA/v2 | 1994 | Norway | invasive(unspecified/other) | Y | 25 | 25 |

| 297-0 | ST-254 complex | 49 | SubB/v1 | 1987 | Chile | carrier | B | 13 | 13 |

| NG F26 | ST-269 complex | 14 | SubA/v2 | 1988 | Norway | carrier | B | 19 | 19 |

| NG 6/88 | ST-269 complex | 13 | SubA/v2 | 1988 | Norway | invasive(unspecified/other) | B | 32 | 40 |

| 44/76 | ST-32 complex | 32 | SubB/v1 | 1976 | Norway | invasive(unspecified/other) | B | 1 | 1 |

| NG 080 | ST-32 complex | 32 | SubB/v1 | 1981 | Norway | invasive(unspecified/other) | B | 1 | 1 |

| NG144/82 | ST-32 complex | 32 | SubB/v1 | 1982 | Norway | invasive(unspecified/other) | B | 1 | 1 |

| BZ 83 | ST-32 complex | 34 | SubB/v1 | 1984 | Netherlands | invasive(unspecified/other) | B | 1 | 1 |

| EG 329 | ST-32 complex | 32 | SubB/v1 | 1985 | East Germany | invasive(unspecified/other) | B | 1 | 1 |

| BZ 169 | ST-32 complex | 32 | SubB/v1 | 1985 | Netherlands | invasive(unspecified/other) | B | 1 | 1 |

| NG PB24 | ST-32 complex | 32 | SubB/v1 | 1985 | Norway | invasive(unspecified/other) | B | 1 | 1 |

| 8680 | ST-32 complex | 32 | SubB/v1 | 1987 | Chile | invasive(unspecified/other) | B | 13 | 13 |

| 204/92 | ST-32 complex | 33 | SubB/v1 | 1992 | Cuba | invasive(unspecified/other) | B | 1 | 1 |

| 196/87 | ST-32 complex | 32 | SubB/v1 | 1987 | Norway | unspecified | C | 1 | 1 |

| E32 | ST-334 complex | 31 | SubA/v2 | 1988 | Norway | carrier | Z | 19 | 19 |

| SWZ107 | ST-35 complex | 35 | SubA/v2 | 1986 | Switzerland | invasive(unspecified/other) | B | 16 | 16 |

| NG E31 | ST-364 complex | 15 | SubA/v2 | 1988 | Norway | carrier | B | 34 | 43 |

| DK 353 | ST-37 complex | 37 | SubA/v2 | 1962 | Denmark | invasive(unspecified/other) | B | 24 | 24 |

| BZ 232 | ST-37 complex | 38 | SubA/v2 | 1964 | Netherlands | invasive(unspecified/other) | B | 24 | 24 |

| A4/M1027 | ST-4 complex | 4 | SubB/v1 | 1937 | USA | invasive(unspecified/other) | A | 5 | 5 |

| 10 | ST-4 complex | 4 | SubB/v1 | 1963 | Burkina Faso | invasive(unspecified/other) | A | 5 | 5 |

| 26 | ST-4 complex | 4 | SubB/v1 | 1963 | Niger | invasive(unspecified/other) | A | 5 | 5 |

| 255 | ST-4 complex | 4 | SubB/v1 | 1966 | Burkina Faso | invasive(unspecified/other) | A | 5 | 5 |

| S3131 | ST-4 complex | 4 | SubB/v1 | 1973 | Ghana | invasive(unspecified/other) | A | 5 | 5 |

| 690 | ST-4 complex | 4 | SubB/v1 | 1980 | India | invasive(unspecified/other) | A | 5 | 5 |

| C751 | ST-4 complex | 4 | SubB/v1 | 1983 | Gambia | invasive(unspecified/other) | A | 5 | 5 |

| 1014 | ST-4 complex | 4 | SubB/v1 | 1985 | Sudan | invasive(unspecified/other) | A | 5 | 5 |

| 2059001 | ST-4 complex | 4 | SubB/v1 | 1990 | Mali | invasive(unspecified/other) | A | 5 | 5 |

| D8 | ST-4 complex | 4 | SubB/v1 | 1990 | Mali | invasive(unspecified/other) | A | 5 | 5 |

| 243 | ST-4 complex | 4 | SubB/v1 | 1966 | Cameroon | unspecified | A | 5 | 5 |

| NG H36 | ST-41/44 complex | 47 | SubA/v2 | 1988 | Norway | carrier | B | 19 | 19 |

| NG E30 | ST-41/44 complex | 44 | SubA/v2 | 1988 | Norway | carrier | B | 32 | 42 |

| BZ 147 | ST-41/44 complex | 48 | SubB/v1 | 1963 | Netherlands | invasive(unspecified/other) | B | 4 | 4 |

| BZ198 | ST-41/44 complex | 41 | SubB/v1 | 1986 | Netherlands | invasive(unspecified/other) | B | 5 | 5 |

| 88/03415 | ST-41/44 complex | 46 | SubB/v1 | 1988 | Scotland | invasive(unspecified/other) | B | 14 | 14 |

| 91/40 | ST-41/44 complex | 42 | SubB/v1 | 1991 | New Zealand | invasive(unspecified/other) | B | 14 | 14 |

| 400 | ST-41/44 complex | 40 | SubB/v1 | 1991 | Austria | invasive(unspecified/other) | B | 14 | 14 |

| AK50 | ST-41/44 complex | 41 | SubB/v1 | 1992 | Greece | invasive(unspecified/other) | B | 4 | 4 |

| M-101/93 | ST-41/44 complex | 41 | SubB/v1 | 1993 | Iceland | invasive(unspecified/other) | B | 4 | 4 |

| 931905 | ST-41/44 complex | 41 | SubB/v1 | 1993 | Netherlands | invasive(unspecified/other) | B | 14 | 14 |

| 50/94 | ST-41/44 complex | 45 | SubB/v1 | 1994 | Norway | invasive(unspecified/other) | B | 4 | 4 |

| M40/94 | ST-41/44 complex | 41 | SubB/v1 | 1994 | Chile | invasive(unspecified/other) | B | 35 | 32 |

| N45/96 | ST-41/44 complex | 41 | SubB/v1 | 1996 | Norway | invasive(unspecified/other) | B | 1 | 1 |

| NG H15 | ST-41/44 complex | 43 | SubA/v2 | 1988 | Norway | carrier | B | 19 | 19 |

| 80049 | ST-5 complex | 5 | SubB/v1 | 1963 | China | carrier | A | 39 | 38 |

| F4698 | ST-5 complex | 5 | SubB/v1 | 1987 | Saudi | carrier | A | 14 | 14 |

| 153 | ST-5 complex | 5 | SubA/v2 | 1966 | China | invasive(unspecified/other) | A | 22 | 22 |

| 154 | ST-5 complex | 6 | SubB/v1 | 1966 | China | invasive(unspecified/other) | A | 36 | 35 |

| S4355 | ST-5 complex | 5 | SubB/v1 | 1974 | Denmark | invasive(unspecified/other) | A | 5 | 5 |

| 7891 | ST-5 complex | 5 | SubB/v1 | 1975 | Finland | invasive(unspecified/other) | A | 5 | 5 |

| 11-004 | ST-5 complex | 5 | SubB/v1 | 1984 | China | invasive(unspecified/other) | A | 5 | 5 |

| H1964 | ST-5 complex | 5 | SubB/v1 | 1987 | UK | invasive(unspecified/other) | A | 5 | 5 |

| 92001 | ST-5 complex | 7 | SubB/v1 | 1992 | China | invasive(unspecified/other) | A | 5 | 5 |

| 14/1455 | ST-5 complex | 5 | SubB/v1 | 1970 | USSR | unspecified | A | 14 | 14 |

| IAL2229 | ST-5 complex | 5 | SubB/v1 | 1976 | Brazil | unspecified | A | 5 | 5 |

| F6124 | ST-5 complex | 5 | SubA/v2 | 1988 | Chad | invasive(unspecified/other) | A | 25 | 25 |

| 860060 | ST-750 complex | 24 | SubA/v3 | 1986 | Netherlands | invasive(unspecified/other) | X | 84 | 69 |

| BZ 10 | ST-8 complex | 8 | SubA/v2 | 1967 | Netherlands | invasive(unspecified/other) | B | 18 | 39 |

| B6116/77 | ST-8 complex | 10 | SubA/v2 | 1977 | Iceland | invasive(unspecified/other) | B | 16 | 16 |

| BZ 163 | ST-8 complex | 9 | SubA/v2 | 1979 | Netherlands | invasive(unspecified/other) | B | 16 | 16 |

| G2136 | ST-8 complex | 8 | SubA/v2 | 1986 | England | invasive(unspecified/other) | B | 16 | 16 |

| AK22 | ST-8 complex | 8 | SubA/v2 | 1992 | Greece | invasive(unspecified/other) | B | 16 | 16 |

| SB25 | ST-8 complex | 8 | SubA/v2 | 1990 | South Africa | invasive(unspecified/other) | C | 16 | 16 |

| 94/155 | ST-8 complex | 66 | SubA/v2 | 1994 | New Zealand | invasive(unspecified/other) | C | 16 | 16 |

| 312 901 | ST-8 complex | 8 | SubA/v2 | 1996 | England | invasive(unspecified/other) | C | 16 | 16 |

| CN100 | Unassigned | 21 | SubB/v1 | 1941 | England | invasive(unspecified/other) | A | 4 | 4 |

| NG E28 | Unassigned | 26 | SubB/v1 | 1988 | Norway | carrier | B | 14 | 14 |

| 3906 | Unassigned | 17 | SubA/v2 | 1977 | China | invasive(unspecified/other) | B | 18 | 39 |

| NG 4/88 | Unassigned | 30 | SubB/v1 | 1988 | Norway | invasive(unspecified/other) | B | 4 | 4 |

| NG 3/88 | Unassigned | 12 | SubA/v3 | 1988 | Norway | invasive(unspecified/other) | B | 96 | 93 |

| NG G40 | Unassigned | 25 | SubA/v2 | 1988 | Norway | carrier | B | 24 | 24 |

| EG 011 | Unassigned | 36 | SubA/v2 | 1986 | East Germany | invasive(unspecified/other) | B | 24 | 24 |

| NG H41 | Unassigned | 27 | SubA/v2 | 1988 | Norway | carrier | B | 25 | 25 |

| DK 24 | Unassigned | 16 | SubA/v2 | 1940 | Denmark | invasive(unspecified/other) | B | 97 | 94 |

| NG H38 | Unassigned | 36 | SubA/v2 | 1988 | Norway | carrier | B | 24 | 24 |

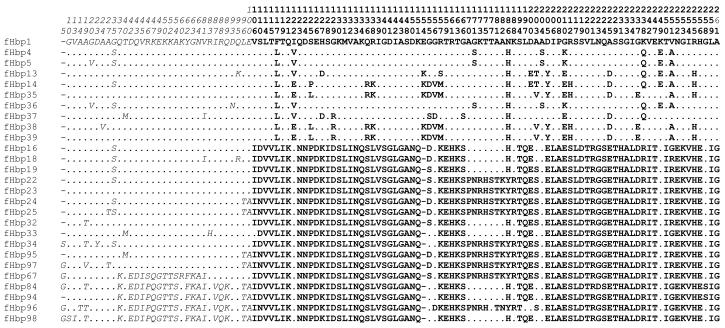

On the basis of 798 unambiguously aligned nucleotides there were a total of 299 variable nucleotide sites within these sequences (Fig. 1). Two broad groups of sequence variant types were evident from this alignment. This corresponds to the previously identified groups: subfamily A/variant 2 and subfamily B/variant 1 (Fletcher et al., 2004). Within subfamily A/variant 2, there were five putative subfamily A/variant 3 sequences which differ from the rest of subfamily A/variant 2 mainly in the N-terminal first ~ 100 amino acids (a.a.) (Masignani et al., 2003). The subfamily A/variant 2 (including variant 3) was significantly more diverse in terms of allele types than subfamily B/variant 1 (D=0.91 (95% CIs 0.87-0.95) vs. 0.80 (95% CIs 0.75-0.85) respectively).

Fig. 1.

Aligned unique fHbp peptide sequence variable sites. fHbp1 to fHbp39 are subfamily B/variant 1; fHbp16 to fHbp97 are subfamily A/variant 2 and fHbp67 to fHbp98 are subfamily A/variant 3.

There was 63% nucleotide sequence identity shared between the two main groups and larger identity within them: 85% nucleotide site identity within subfamily A/variant 2 and 87% nucleotide site identity in subfamily B/variant 1. The overall mean Kimura 2-parameter p-distance among all gene sequences was 0.165. The within-group mean p-distances were 0.046 for subfamily A/variant 2 and 0.032 for subfamily B/variant 1 with a mean average p-distance between the two subfamilies/variants of 0.302. There was 56% deduced amino acid sequence identity shared between the two groups. Within subfamily A/variant 2 there was 81% amino acid site identity and within subfamily B/variant 1 there was 87% amino acid site identity. The overall mean p-distance among the amino acid sequences was 0.17. The within-group mean p-distances for subfamily A/variant 2 and subfamily B/variant 1 were 0.052 and 0.038 respectively. The mean average p-distance between the two subfamilies/variants was 0.31. Without the subfamily A/variant 3 sequences, subfamily A/variant 2 nucleotide sequences identity was 90% and amino acid site identity was 88%.

Sequence variability was found throughout the gene and encoded protein (Fig. 1). There was a marked difference in variability, however, between the N–terminal first ~105 (a.a.) and the C terminal region of ~161 a.a. where sequences were more variable. Amino acid sequence identity of the C terminal region between the two groups was 48%; however, there was more identity within the groups (subfamily A/variant 2 - 87%; subfamily B/variant 1 - 84%). For the N-terminal region there was 67% amino acid identity between the two subfamilies/variants and 70% within subfamily A/variant 2 and 93% within subfamily B/variant 1. In the absence of the subfamily A/variant 3 sequences, for subfamily A/variant 2, there was 90% amino acid identity in the C terminal region and 86% in the N terminal region.

The amino acid Glu/Lys at position 154 was present in subfamily B/variant 1 isolates but not subfamily A/variant 2 isolates (Fig.1). There was an absence, in subfamily A/variant 2 isolates, of Arg204 (here at a.a. 212) considered to be key in antibody binding in the subfamily B/variant 1 antigen (Giuliani et al., 2005), where it was substituted with serine. There were 81% of subfamily B/variant 1 isolates that contained Arg204; the rest had a histidine residue at this position. Two subfamily B/variant 1 isolates (id 79126 and 79128; peptide 37) had a substitution of a G for a T in the final stop codon and were thus extended for a further 9 bases. The N-terminal region separates the subfamily A/variant 3 isolate sequences from the other subfamilies/variants (Fig. 1). Subfamily A/variant 3 sequences contained an insertion at 67 - 69 a.a. of lysine, aspartic acid and asparagine, not present in the other variants. This insertion has previously been noted as being present in a subset of subfamily A protein sequences (Fletcher et al., 2004). Three of the five subfamily A/variant 3 sequences also contained a 5 a.a. glycine-rich insertion at the N-terminal end. This insertion has previously been found in sequences of both subfamilies/variants (Fletcher et al., 2004) and is thought to be used as a means of lengthening the chain that attaches the folded protein to accommodate differences in LOS length on the outermembrane (Mascioni et al., 2008).

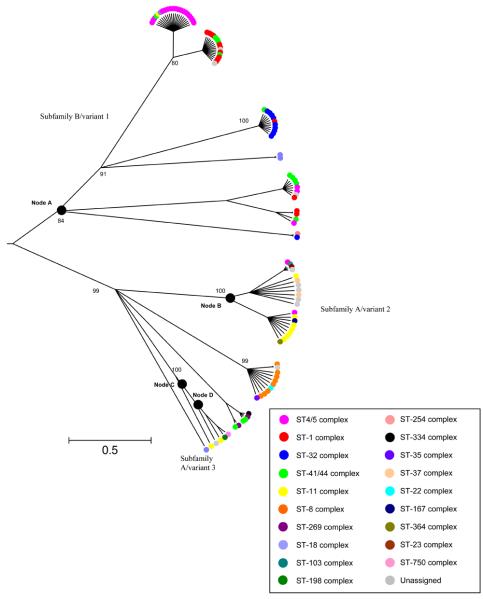

Genealogical analysis using ClonalFrame, and phylogenies constructed with neighbour-joining and maximum-likelihood methods (not shown) resolved protein and nucleotide sequences into two major groups, with the subfamily A/variant 3 isolates branching off from the rest of the subfamily A/variant 2 (Fig. 2). ClonalFrame, gives equal weight to genetic events that result in one nucleotide change, as single horizontal genetic exchange events that result in many nucleotide changes and did not separate the putative subfamily A/variant 3 isolate sequences from the other subfamily A/variant 2 isolates (Fig. 2), although they were more distant from them in neighbour-joining and maximum-likelihood phylogenies (not shown).

Fig. 2.

A 75% majority-rule consensus ClonalFrame radial tree of 107 aligned nucleotide sequences with colour coding according to clonal complex and confidence values in nodes. Nodes are defined as the most recent common ancestor of the isolates in the branch above it.

Clonal complex/serogroup association

The distribution of subfamily/variant peptides was not random among clonal complexes, showing some clustering with particular meningococcal genotypes (Fig. 2). For example, the ST-11 complex was associated with subfamily A/variant 2 and in particular a cluster within this subfamily/variant (6 of 8 isolates were fHbp peptide 22; Fisher's exact test p< 0.005). Similarly, the ST-8 complex was found to be only associated with this subfamily/variant and 7 of 8 isolates had the fHbp 16 peptide (Fisher's exact test p< 0.005). The serogroup A-associated complexes ST-4 and ST-5 were clustered together and associated mainly with subfamily B/variant 1. The ST-4 complex was particularly homogeneous as all isolates had the fHbp 5 peptide (Fisher's exact test p< 0.005). All the ST-32 complex isolates were found associated with subfamily B/variant 1 with 9/10 isolates having the fHbp 1 peptide type (Fisher's exact test p< 0.005). The ST-1 complex was significantly associated with fHbp peptide 4 (10/14 isolates, Fisher's exact test p< 0.005). The other main hyperinvasive lineage, ST-41/44 complex, was more diverse with respect to the subfamilies/variants observed.

Similarly, there was a relationship between serogroup (particularly non-B serogroups) and variants/subfamilies (Table 1), although this was at least in part due to the known association of clonal complex with serogroup (Trotter et al., 2007). A total of 55% of subfamily B/variant 1 were serogroup A (Fisher's exact test p< 0.005) compared to 4% for subfamily A/variant 2. Serogroup C was found in 1.6% of subfamily B/variant 1 while it accounted for 35% of subfamily A/variant 2 (Fisher's exact test p< 0.005). There were no W-135, Y or Z subfamily B/variant 1 types while each serogroup accounted for 4% of subfamily A/variant 2 isolates. Serogroup B was more evenly distributed, accounting for 50% of subfamily A/variant 2 isolates and 44% of subfamily B/variant 1 isolates. However, 70% of serogroup B disease-associated isolates were subfamily B/variant 1.

Evidence of recombination and selection

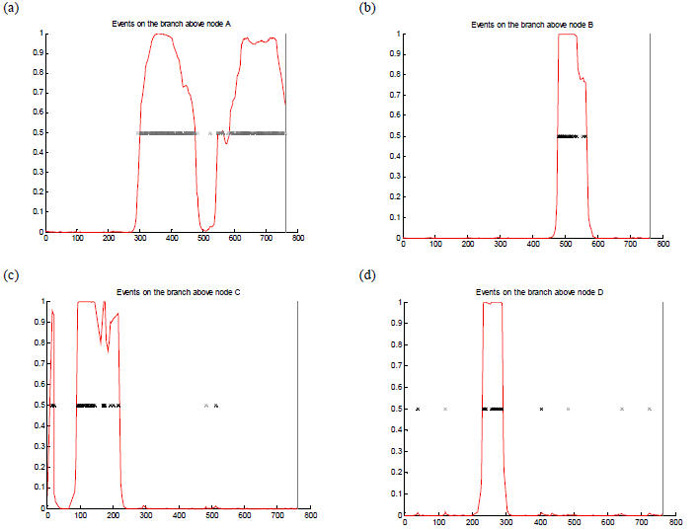

Maximum Chi Squared analysis identified putative recombination sites after nucleotide sites 281 and 326. ClonalFrame analysis indicated strong evidence of horizontal genetic exchange in the C terminal region from around 300 bp onwards (node A Fig. 2 and Fig. 3(a)). Also, in the N terminal region of subfamily A/variant 3 sequences there was strong evidence of lateral gene transfer which presumably gave rise to this variant within the subfamily A/variant 2 group (nodes C and D (Fig. 3(c) and (d)). Other points of recombination were identified including, above node B which contains subfamily A/variant 2 sequences (Fig. 3(b)).

Fig. 3.

Representation of fHbp gene recombination events (a) - (d). The nucleotide sequence of fHbp gene is on the x axis with the red line indicating the probability for an import from 0 to 1 (y axis). The panels depict genetic events above nodes A, B, C and D shown in the 75% majority-rule consensus ClonalFrame tree panel (Fig. 2). Each inferred substitution is indicated by a cross, the intensity of which indicates the posterior probability for that substitution. In panel (a) horizontal genetic exchange is depicted occurring from bases 300 to 500 and 550 to 800; in panel (b) from 450-600; panel (c) horizontal genetic exchange is depicted occurring from bases 100 to 250 and in panel (d) at about 200 and 300 bases.

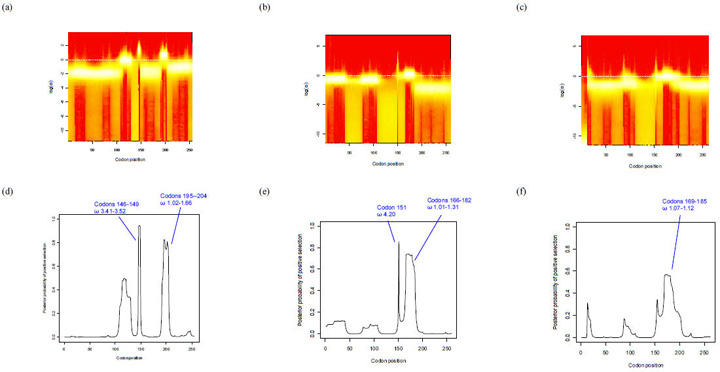

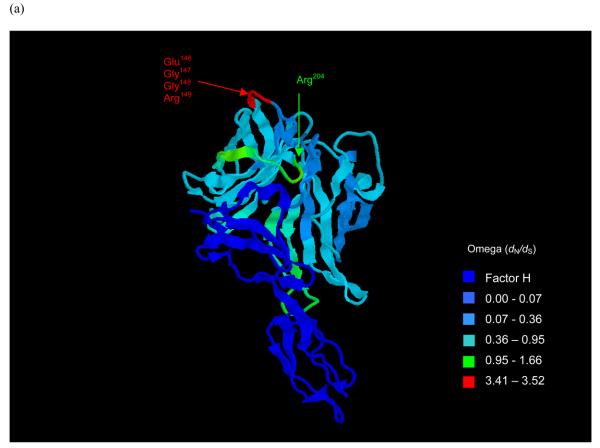

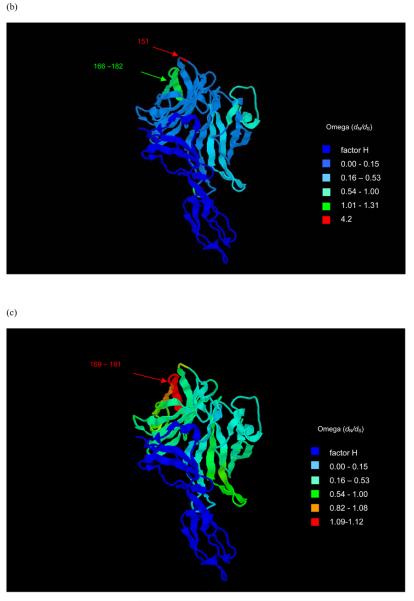

The fHbp locus had an average dN/dS ratio of 0.35 indicating a level of purifying selection against amino acid change. Previous estimates have been 0.51 ± 0.7 (Bambini et al., 2009) and is comparable to that of other antigenic genes such as fetA (0.314) (Thompson, 2001). Codon-by-codon analysis of selection on the gene was possible using OmegaMap. Separate analyses for each of the subfamilies/variants, including variant 3, indicated that in the C terminal region (after ~ 318 nucleotides encoding 106 amino acids) there was diversifying immune selection (ω>1) acting on particular areas in each of the subfamilies/variants (Figs. 4(a) - (f)). Subfamily B/variant 1 and subfamily A/variant 2 (not including variant 3) shared one positively selected codon (147 and 151 in subfamily B/variant 1 and subfamily A/variant 2 respectively). Subfamily B/variant 1 displayed positive selection at the four codons 146-149 (ω 3.41-3.52) and also at codons 195-204 (ω 1.02-1.66). Subfamily A variants 2 and 3 shared the positively selected sites from codons 169-181. The per-site point estimate of ω inferred for each of the subfamily/variant isolates was used to colour a three-dimensional pdb file of the solution structure of a complex between a subfamily B/variant 1 GNA1870/fHbp protein and a region of the fH protein (code 2W81) (Schneider et al., 2009). The temperature colouring of the protein enabled the demonstration of the regions under positive selection on the 3D model (Fig. 5(a) (b) & (c)). These regions did not overlap with residues involved interactions with the fH molecule (Schneider et al., 2009).

Fig. 4.

OmegaMap program output using subfamily A/variant 2 and subfamily B/variant 1 nucleotide sequences. Panels (a), (b) and (c) depict fireplots of the sitewise posterior distribution of log(ω) for subfamily B, subfamily A (without variant 3) and subfamily A/variant 3 sequences respectively. A fireplot visualizes the posterior on log(ω) along the sequence using a colour gradient where a higher posterior density is represented by more intense colour (closer to white), and lower posterior density is represented by less intense colour (closer to red). Panels (d), (e) and (f) depict the posterior probability of positive selection (y-axis, values 0 to 1) along the codon sequence (x-axis) for subfamily B, subfamily A (without variant 3) and subfamily A/variant 3 sequences respectively. Sites with a point estimate of ω > 1 are indicated with blue braces. Note: Variants 2 and 3 differ from subfamily B/variant 1 in length by +4 and +7 bp respectively e.g. residue 147 of variant 1 is at position 151 of subfamily A/variant 2 (e) and 154 of subfamily A/variant 3 (d).

Fig. 5.

Structure of the fH-fHbp complex (Schneider et al., 2009) with temperature colouring using per-site point estimate of ω for (a) subfamily B/variant 1 sequences, (b) subfamily A/variant 2 and (c) subfamily A/variant 3 sequences. Peptides indicated in (a) are putative bactericidal epitopes previously identified (Giuliani et al., 2005; Scarselli et al., 2008; Welsch et al., 2004). In (b) and (c) positively selected sites are indicated. Note: subfamily A/variant 2 and subfamily A/variant 3 differ from subfamily B/variant 1 in length by +4 bp (e.g. Glu151 is equivalent to Glu147 in variant 1) and +7 bp (e.g. Glu154 is equivalent to Glu147 in variant 1) in length respectively.

Discussion

An ideal vaccine candidate provides cross-protection against all variants of a targeted pathogen. To date, proteins suggested as components of meningococcal vaccines either do not elicit protective immune responses or, like fHbp, are variable (Jodar et al., 2002). Consequently, it is important to catalogue this diversity before a vaccine formulation is finalised to ensure maximum vaccine coverage. For fHbp a number of studies have been performed to achieve this (Bambini et al., 2009; Murphy et al., 2009); however, a universal agreed nomenclature is essential to enable comparisons among different studies. Two different fHbp classification schemes have been proposed: one classifies the protein variants of fHbp (referred to as GNA1870) into three variant families, named variants 1, 2, and 3 (Masignani et al., 2003); while the other group's variants of the same protein (referred to as LP2086) are resolved into subfamilies A and B (Fletcher et al., 2004). Here, a unified nomenclature is proposed in which unique fHbp peptide and nucleotide sequences are assigned numbers arbitrarily and entered into a database that can be queried and new sequences deposited (http://neisseria.org/nm/typing/fhbp). Using this nomenclature as a basis, higher order classifications can be applied without confusion.

Understanding diversity also requires appropriate isolate collections, with a sample frame appropriate to the question addressed. For this reason, the present study investigated the 107 meningococci used to establish MLST, which includes the globally important disease-associated hyperinvasive meningococcal lineages of all serogroups from the latter half of the twentieth century, which have been extensively characterised (Callaghan et al., 2006; Maiden et al., 1998; Thompson et al., 2003; Urwin et al., 2004). The number of fHbp alleles in this set, 28 encoding 27 peptides was broadly comparable to the number of other surface proteins investigated: PorA (33 alleles encoding 33 peptides); PorB (31 alleles encoding 28 peptides); FetA (33 alleles encoding 31 peptides); and Opa (90 alleles encoding 83 peptides)(Callaghan et al., 2006; Urwin et al., 2004). The diversity of fHbp resolved into two major clusters by the phylogenetic approaches used (Fig. 2), as described previously (Fletcher et al., 2004; Murphy et al., 2009), with evidence of a third group (variant 3) (Masignani et al., 2003). While other variants may be discovered by further studies, especially of carried rather than disease-associated meningococci, comparison with published sequences from various sources (Genbank, http://neisseria.org/nm/typing/fhbp) demonstrated that the 107 isolates included all the major variant clusters of the protein described to date. Of the previously described groups, Subfamily B/variant 1 was the most prevalent (60%) among the 107 isolates. In previous studies it accounted for 54 - 70% of isolates (Beernink et al., 2007; Fletcher et al., 2004; Jacobsson et al., 2006; Masignani et al., 2003; Murphy et al., 2009; Welsch et al., 2004).

There was evidence that fHbp alleles and consequently variant peptides are generated by horizontal genetic exchange, as is the case for other meningococcal antigens (Bennett et al., 2008; Derrick et al., 1999; Harrison et al., 2008). Further, the gene is also present in Neisseria gonorrhoeae, with the gonococcal fHbp sequences described to date belonging to subfamily A/variant 2 group (Fletcher et al., 2004; Masignani et al., 2003). It is possible that subfamily A/variant 3 arose through a recombination event with a DNA fragment donated from another member of the genus Neisseria, and idea supported by a neighbour-joining phylogenetic analysis of peptide sequences that clustered the subfamily A/variant 3 sequences between two gonococcal fHbp sequences and other subfamily A/variant 2 sequences (data not shown). Common gene pools have been documented for other Neisseria antigens such as PorB2, FetA and TbpB (Bennett et al., 2008; Derrick et al., 1999; Harrison et al., 2008). In the case of PorB and TbpB, different variant classes are thought to have arisen due to inter-species recombination.

While N. gonorrhoeae appears to have a fHbp gene, it is known to bind fH via porin proteins (Ngampasutadol et al., 2008). Both meningococci and gonococci have specificity for human fH, which may partly explain their pathogenic restriction in humans (Granoff et al., 2009; Welsch & Ram, 2008). The gene encoding fHbp has also been detected in the commensal species Neisseria cinerea and Neisseria lactamica and a potential fHbp peptide detected by Western blot analysis (Fletcher et al., 2004; Masignani et al., 2003); however, the distribution of the fHbp gene among the Neisseria and its function in the non-pathogenic organisms is yet to be fully elucidated.

Despite the genetic and antigenic diversity of carried populations of meningococci (Caugant & Maiden, 2009; Yazdankhah & Caugant, 2004), most invasive meningococcal disease is caused by a small number of clonal complexes, known as the hyperinvasive lineages (Brehony et al., 2007; Caugant, 2001; Yazdankhah et al., 2004). In common with other variable antigens (Callaghan et al., 2008; Harrison et al., 2008; Trotter et al., 2007; Urwin et al., 2004), the distribution of fHbp variants was not random among clonal complexes, with certain variants more likely to be found in given hyperinvasive lineages, as seen in other isolate collections (Bambini et al., 2009; Jacobsson et al., 2006; Masignani et al., 2003). The ST-32 complex and serogroup A were significantly associated with particular subfamily B/variant 1 fHbp peptides (1 and 5 respectively). The ST-11 complex, which can be distinguished from other hyper-invasive lineages by harbouring only tbpB isotype I and lacking the opcA gene (Claus et al., 2001), was significantly associated with subfamily A and fHbp peptide 22. Similarly, stable associations have been observed in serogroup A, X and W-135 meningococci in Africa over a 45 year period (Beernink et al., 2009b). It should be noted, however, that while these associations exist, they are not absolute. For example, while most of the ST-32 complex isolates were peptide 1, there was an isolate with the fHbp peptide 13 and several of the complexes, while they may have a dominant fHbp peptide type, can also contain others. The ST-41-44 complex in particular was heterogeneous, with multiple fHbp peptides. (Bambini et al., 2009; Beernink et al., 2007; Jacobsson et al., 2006; Masignani et al., 2003). The reasons for these associations are not fully understood but models of strain structure in recombining pathogens show that immune selection can, counter-intuitively, lead to the stable associations of antigenic variants characteristic of meningococcal hyperinvasive lineages (Gupta et al 1996, Callaghan et al 2008, Buckee et al 2008).

The availability of protein structures for fHbp, including one with the protein bound to factor H(Schneider et al., 2009), allowed analysis of the sequence variability of regions encoding different structural and functional domains. Variation in peptide sequence is present throughout fHbp, rather than being limited to particular variable regions as is the case in the PorA, FetA, and PorB2 (but not PorB3) porins. Most fHbp diversity was found in the C-terminal region (~161 a. a. in length) of fHbp, while there was less in the N-terminal region (~ 105 a. a. in length), which contained a domain that anchors the protein to the cell membrane (Mascioni et al., 2008). Other invariant regions of the protein are those involved with factor H interaction (particularly within subfamilies/variants although some of the interaction residues show some polymorphism (Schneider et al., 2009)) and residues that make up hydrophobic cores of the β-barrels and the points of contact between the N and C terminal domains (Mascioni et al., 2008).

The selection pressures acting on fHbp were deduced by means of a Bayesian algorithm, which has a number of advantages over the maximum likelihood approaches used previously to analyse selection pressures on the PorB protein (Urwin et al., 2002), and the results compared to those obtained in functional studies. Epitope mapping has identified the residue Arg204 as being essential for the binding of a bactericidal monoclonal antibody (MAb) (Giuliani et al., 2005; Scarselli et al., 2008). Residues also identified as potentially involved in a conformational epitope with Arg204 are residues Glu146 - Arg149 (Cantini et al., 2006; Scarselli et al., 2008; Welsch et al., 2004). Due to their placement and clustering in structural models, it is thought that these residues could make up a bactericidal epitope in the C-terminal region with the potential cooperation of other residues (Cantini et al., 2006; Scarselli et al., 2008) and have been shown to be placed away from the fH recognition site and therefore may not interfere with fH binding (Schneider et al., 2009). The selection analyses identified these residues as displaying evidence of immune selection on the subfamily B/variant 1 protein, underlining their potential relevance as protective epitopes. One of these residues also showed evidence of positive selection in subfamily A/variant 2 - 151 (147 in subfamily B/variant 1).

Other protective epitopes identified to date include residues 121-122 present in subfamily B/variant 1 proteins, residues between 25-59 present in subfamily A/variant 2 and subfamily B/variant 1 and residues between positions 174 to 216 of variant 2 and 3 proteins (Beernink & Granoff, 2008; Beernink et al., 2009a; Beernink et al., 2008). Particularly in meningococci expressing fHbp at low levels, these epitopes can induce bactericidal activity by eliciting cooperative pairs of MAbs that and also inhibit fH binding thus increasing complement-mediated activity (Beernink et al., 2008). The selection analysis provided evidence for positive selection in a region that partially overlapped with one of these putative bactericidal epitopes found in the C terminal region of the subfamily A/variant 2 and subfamily A/variant 3 proteins i.e. residue 174. These results are very encouraging that such analyses can be used to predict regions involved in immune interactions of other bacterial proteins.

Molecular epidemiology has played a major role in the development, implementation, and study of meningococcal vaccines (Bjune et al., 1991; Maiden et al., 2008; O'Hallahan et al., 2005; Rodriguez et al., 1999). For candidate protein components it is essential to determine the number of variants required and to identify those likely to provide the broadest possible protection, ideally before a vaccine formulation is tested in humans. Although the use of functional assays is important, nucleotide and peptide sequence diversity give important guides to this process. In the case of fHbp, the existence of multiple variants and the evidence for particular epitopes under immune selection indicates that, as for other meningococcal antigens it will be important to use vaccine formulations with multiple components to achieve broad coverage, particularly as it has been shown that cross-protection between the two major subfamilies and within, subfamily A, variants 2 and 3, is limited (Beernink et al., 2007; Fletcher et al., 2004; Masignani et al., 2003). An alternative strategy is to create chimeric proteins containing domains from the different subfamilies/variants (Beernink & Granoff, 2008). However multivalency is achieved, the optimum number of variants to be used will depend on a combination of molecular epidemiological and functional studies. Further, the lifespan of such vaccines will depend on the dynamics of fHbp evolution in natural populations of meningococci and any possible effects of vaccination on this process. The nomenclature scheme and analytical framework described here should contribute to assembling the information required to answer these questions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Gary W. Zlotnick, Ph.D. who provided primer sequences used in this study. We are also grateful to Dr. Keith Jolley for setting up the fHbp database.

List of abbreviations

- fHbp

Factor H-binding protein

- fH

Factor H

- OMP

Outer membrane protein

- OMV

Outer membrane vesicle

- MLST

Multilocus sequence typing

- ST

Sequence type

- D

Index of diversity

- ω

Omega (dN/dS)

References

- Ala'Aldeen DA, Borriello SP. The meningococcal transferrin-binding proteins 1 and 2 are both surface exposed and generate bactericidal antibodies capable of killing homologous and heterologous strains. Vaccine. 1996;14:49–53. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(95)00136-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bambini S, Muzzi A, Olcen P, Rappuoli R, Pizza M, Comanducci M. Distribution and genetic variability of three vaccine components in a panel of strains representative of the diversity of serogroup B meningococcus. Vaccine. 2009;27:2794–2803. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.02.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beernink PT, Granoff DM. Bactericidal Antibody Responses Induced by Meningococcal Recombinant Chimeric Factor H Binding Protein Vaccines. Infect. Immun. 2008;IAI:00033–00008. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00033-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beernink PT, LoPasso C, Angiolillo A, Felici F, Granoff D. A region of the N-terminal domain of meningococcal factor H-binding protein that elicits bactericidal antibody across antigenic variant groups. Molecular Immunology. 2009a;46:1647–1653. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beernink PT, Caugant DA, Welsch JA, Koeberling O, Granoff DM. Meningococcal Factor H-Binding Protein Variants Expressed by Epidemic Capsular Group A, W-135, and X Strains from Africa. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2009b;199:1360–1368. doi: 10.1086/597806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beernink PT, Welsch JA, Harrison LH, Leipus A, Kaplan SL, Granoff DM. Prevalence of factor H-binding protein variants and NadA among meningococcal group B isolates from the United States: implications for the development of a multicomponent group B vaccine. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:1472–1479. doi: 10.1086/514821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beernink PT, Welsch JA, Bar-Lev M, Koeberling O, Comanducci M, Granoff DM. Fine Antigenic Specificity and Cooperative Bactericidal Activity of Monoclonal Antibodies Directed at the Meningococcal Vaccine Candidate, Factor H-Binding Protein 10.1128/IAI.00367-08. Infect. Immun. 2008;IAI:00367–00308. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00367-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett JS, Thompson EA, Kriz P, Jolley KA, Maiden MC. A common gene pool for the Neisseria FetA antigen. Int J Med Microbiol. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2008.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernfield L, Fletcher DL, Howell A, Farley JE, Zagursky R, Knauf M, Zlotnick G. Identification of a novel vaccine candidate for group B Neisseria meningitidis. In: Caugant DA, Wedege E, editors. Thirteenth International Pathogenic Conference; Oslo, Norway. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bjune G, Høiby EA, Grønnesby JK, Arnesen O, Fredriksen JH, Halstensen A, Holten E, Lindbak AK, Nøkleby H, Rosenqvist E, Solberg LK, Closs O, Eng J, Frøholm LO, Lystad A, Bakketeig LS, Hareide B. Effect of outer membrane vesicle vaccine against group B meningococcal disease in Norway. Lancet. 1991;338:1093–1096. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)91961-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brehony C, Jolley KA, Maiden MC. Multilocus sequence typing for global surveillance of meningococcal disease. FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 2007;31:15–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2006.00056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaghan MJ, Jolley KA, Maiden MC. Opacity-associated adhesin repertoire in hyperinvasive Neisseria meningitidis. Infection and Immunity. 2006;74:5085–5094. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00293-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaghan MJ, Buckee C, McCarthy ND, Ibarz-Pavon AB, Jolley K, Faust S, Gray SJ, Kaczmarski EB, Levin M, Kroll JS, Maiden MC, Pollard AJ. The Opa protein repertoires of disease-causing and carried meningococci. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2008 doi: 10.1128/JCM.00005-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantini F, Veggi D, Dragonetti S, Savino S, Scarselli M, Romagnoli G, Pizza M, Banci L, Rappuoli R. Solution structure of the factor H binding protein, a survival factor and protective antigen of Neisseria meningitidis 10.1074/jbc.C800214200. J. Biol. Chem. 2009:C800214200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C800214200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantini F, Savino S, Scarselli M, Masignani V, Pizza M, Romagnoli G, Swennen E, Veggi D, Banci L, Rappuoli R. Solution structure of the immunodominant domain of protective antigen GNA1870 of Neisseria meningitidis. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:7220–7227. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508595200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caugant DA. Global trends in meningococcal disease. In: Pollard AJ, Maiden MCJ, editors. Meningococcal Disease: methods and protocols. Humana Press; Totowa, New Jersey: 2001. p. 273-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caugant DA, Maiden MCJ. Meningococcal carriage and disease--Population biology and evolution. Vaccine. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.04.061. In Press, Corrected Proof. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claus H, Stoevesandt J, Frosch M, Vogel U. Genetic isolation of meningococci of the electrophoretic type 37 complex. Journal of Bacteriology. 2001;183:2570–2575. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.8.2570-2575.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comanducci M, Bambini S, Brunelli B, Adu-Bobie J, Arico B, Capecchi B, Giuliani MM, Masignani V, Santini L, Savino S, Granoff DM, Caugant DA, Pizza M, Rappuoli R, Mora M. NadA, a novel vaccine candidate of Neisseria meningitidis. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2002;195:1445–1454. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derrick JP, Urwin R, Suker J, Feavers IM, Maiden MCJ. Structural and evolutionary inference from molecular variation in Neisseria porins. Infection and Immunity. 1999;67:2406–2413. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.5.2406-2413.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Didelot X, Falush D. Inference of bacterial microevolution using multilocus sequence data. Genetics. 2007;175:1251–1266. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.063305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finne J, Leinonen M, Makela PH. Antigenic similarities between brain components and bacteria causing meningitis. Implications for vaccine development and pathogenesis. Lancet. 1983;2:355–357. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)90340-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher LD, Bernfield L, Barniak V, Farley JE, Howell A, Knauf M, Ooi P, Smith RP, Weise P, Wetherell M, Xie X, Zagursky R, Zhang Y, Zlotnick GW. Vaccine potential of the Neisseria meningitidis 2086 lipoprotein. Infect Immun. 2004;72:2088–2100. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.4.2088-2100.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuliani MM, Santini L, Brunelli B, Biolchi A, Arico B, Di Marcello F, Cartocci E, Comanducci M, Masignani V, Lozzi L, Savino S, Scarselli M, Rappuoli R, Pizza M. The region comprising amino acids 100 to 255 of Neisseria meningitidis lipoprotein GNA 1870 elicits bactericidal antibodies. Infect Immun. 2005;73:1151–1160. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.2.1151-1160.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granoff DM, Welsch JA, Ram S. Binding of Complement Factor H (fH) to Neisseria meningitidis Is Specific for Human fH and Inhibits Complement Activation by Rat and Rabbit Sera 10.1128/IAI.01191-08. Infect. Immun. 2009;77:764–769. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01191-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundmann H, Hori S, Tanner G. Determining confidence intervals when measuring genetic diversity and the discriminatory abilities of typing methods for microorganisms. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2001;39:4190–4192. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.11.4190-4192.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison OB, Maiden MC, Rokbi B. Distribution of transferrin binding protein B gene (tbpB) variants among Neisseria species. BMC Microbiology. 2008;8:66. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-8-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter PR, Gaston MA. Numerical index of discriminatory ability of typing systems: an application of Simpson's index of diversity. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1988;26:2465–2466. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.11.2465-2466.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsson S, Thulin S, Molling P, Unemo M, Comanducci M, Rappuoli R, Olcen P. Sequence constancies and variations in genes encoding three new meningococcal vaccine candidate antigens. Vaccine. 2006;24:2161–2168. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jodar L, Feavers IM, Salisbury D, Granoff DM. Development of vaccines against meningococcal disease. Lancet. 2002;359:1499–1508. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08416-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolley KA, Maiden MC. AgdbNet - antigen sequence database software for bacterial typing. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:314. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolley KA, Feil EJ, Chan MS, Maiden MC. Sequence type analysis and recombinational tests (START) Bioinformatics. 2001;17:1230–1231. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.12.1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DM. Epidemiology of meningococcal disease in Europe and the USA. In: Cartwright K, editor. Meningococcal disease. John Wiley and Sons Ltd; Chichester, England: 1995. pp. 147–157. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Tamura K, Nei M. MEGA3: Integrated software for Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis and sequence alignment. Briefings in Bioinformatics. 2004;5:150–163. doi: 10.1093/bib/5.2.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambris JD, Ricklin D, Geisbrecht BV. Complement evasion by human pathogens. 2008;6:132–142. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madico G, Welsch JA, Lewis LA, McNaughton A, Perlman DH, Costello CE, Ngampasutadol J, Vogel U, Granoff DM, Ram S. The meningococcal vaccine candidate GNA1870 binds the complement regulatory protein factor H and enhances serum resistance. J Immunol. 2006;177:501–510. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiden MC, Ibarz-Pavon AB, Urwin R, Gray SJ, Andrews NJ, Clarke SC, Walker AM, Evans MR, Kroll JS, Neal KR, Ala'aldeen DA, Crook DW, Cann K, Harrison S, Cunningham R, Baxter D, Kaczmarski E, Maclennan J, Cameron JC, Stuart JM. Impact of Meningococcal Serogroup C Conjugate Vaccines on Carriage and Herd Immunity. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2008;197:737–743. doi: 10.1086/527401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiden MCJ, Bygraves JA, Feil E, Morelli G, Russell JE, Urwin R, Zhang Q, Zhou J, Zurth K, Caugant DA, Feavers IM, Achtman M, Spratt BG. Multilocus sequence typing: a portable approach to the identification of clones within populations of pathogenic microorganisms. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 1998;95:3140–3145. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin D, Cadieux N, Hamel J, Brodeur BR. Highly conserved Neisseria meningitidis surface protein confers protection against experimental infection. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1997;185:1173–1183. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.7.1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascioni A, Bentley BE, Camarda R, Dilts DA, Fink P, Gusarova V, Hoiseth S, Jacob J, Lin SL, Malakian K, McNeil LK, Mininni T, Moy F, Murphy E, Novikova E, Sigethy S, Wen Y, Zlotnick GW, Tsao DHH. Structural basis for the immunogenic properties of the meningococcal vaccine candidate LP2086 10.1074/jbc.M808831200. J. Biol. Chem. 2008:M808831200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808831200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masignani V, Comanducci M, Giuliani MM, Bambini S, Adu-Bobie J, Arico B, Brunelli B, Pieri A, Santini L, Savino S, Serruto D, Litt D, Kroll S, Welsch JA, Granoff DM, Rappuoli R, Pizza M. Vaccination against Neisseria meningitidis using three variants of the lipoprotein GNA1870. J Exp Med. 2003;197:789–799. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy E, Andrew L, Lee K, Dilts DA, Nunez L, Fink PS, Ambrose K, Borrow R, Findlow J, Taha MK, Deghmane AE, Kriz P, Musilek M, Kalmusova J, Caugant DA, Alvestad T, Mayer LW, Sacchi CT, Wang X, Martin D, von Gottberg A, du Plessis M, Klugman KP, Anderson AS, Jansen KU, Zlotnick GW, Hoiseth SK. Sequence Diversity of the Factor H Binding Protein Vaccine Candidate in Epidemiologically Relevant Strains of Serogroup B Neisseria meningitidis. J Infect Dis. 2009 doi: 10.1086/600141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngampasutadol J, Ram S, Gulati S, Agarwal S, Li C, Visintin A, Monks B, Madico G, Rice PA. Human Factor H Interacts Selectively with Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Results in Species-Specific Complement Evasion. J Immunol. 2008;180:3426–3435. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.5.3426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Hallahan J, Lennon D, Oster P, Lane R, Reid S, Mulholland K, Stewart J, Penney L, Percival T, Martin D. From secondary prevention to primary prevention: a unique strategy that gives hope to a country ravaged by meningococcal disease. Vaccine. 2005;23:2197–2201. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.01.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard AJ, Scheifele D, Rosenstein N. In: Epidemiology of Meningococcal Disease in North America. In Meningococcal Disease: Methods and Protocols. Pollard AJ, Maiden MC, editors. Humana Press; Totowa, New Jersey: 2001. pp. 341–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rappuoli R. Reverse vaccinology. Current Opinion in Microbiology. 2000;3:445–450. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(00)00119-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez AP, Dickinson F, Baly A, Martinez R. The epidemiological impact of antimeningococcal B vaccination in Cuba. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1999;94:433–440. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761999000400002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez de Córdoba S, Esparza-Gordillo J, Goicoechea de Jorge E, Lopez-Trascasa M, Sánchez-Corral P. The human complement factor H: functional roles, genetic variations and disease associations. Molecular Immunology. 2004;41:355–367. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rokbi B, Renauld-Mongenie G, Mignon M, Danve B, Poncet D, Chabanel C, Caugant DA, Quentin-Millet MJ. Allelic diversity of the two transferrin binding protein B gene isotypes among a collection of Neisseria meningitidis strains representative of serogroup B disease: implication for the composition of a recombinant TbpB-based vaccine. Infection and Immunity. 2000;68:4938–4947. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.9.4938-4947.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell JE, Jolley KA, Feavers IM, Maiden MC, Suker J. PorA variable regions of Neisseria meningitidis. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2004;10:674–678. doi: 10.3201/eid1004.030247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarselli M, Cantini F, Santini L, Veggi D, Dragonetti S, Donati C, Savino S, Giuliani MM, Comanducci M, Di Marcello F, Romagnoli G, Pizza M, Banci L, Rappuoli R. Epitope mapping of a bactericidal monoclonal antibody against the factor H binding protein of Neisseria meningitidis. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.12.005. In Press, Accepted Manuscript. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider MC, Exley RM, Chan H, Feavers I, Kang Y-H, Sim RB, Tang CM. Functional Significance of Factor H Binding to Neisseria meningitidis. J Immunol. 2006;176:7566–7575. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.12.7566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider MC, Prosser BE, Caesar JJE, Kugelberg E, Li S, Zhang Q, Quoraishi S, Lovett JE, Deane JE, Sim RB, Roversi P, Johnson S, Tang CM, Lea SM. Neisseria meningitidis recruits factor H using protein mimicry of host carbohydrates. 2009 doi: 10.1038/nature07769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seib KL, Serruto D, Oriente F, Delany I, Adu-Bobie J, Veggi D, Arico B, Rappuoli R, Pizza M. Factor H-binding protein is important for meningococcal survival in human whole blood and serum and in the presence of the antimicrobial peptide LL-37. Infect Immun. 2009;77:292–299. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01071-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson EH. Measurement of Diversity. Nature. 1949;163:688. [Google Scholar]

- Staden R. The Staden sequence analysis package. Molecular Biotechnology. 1996;5:233–241. doi: 10.1007/BF02900361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swofford D. PAUP* Phylogenetic analysis using parsimony and other methods. Sinauer; Sunderland, Mass.: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson EAL. Antigenic variation in the potential meningococcal vaccine candidate FetA. University of Oxford; Oxford: 2001. p. 183. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson EAL, Feavers IM, Maiden MCJ. Antigenic diversity of meningococcal enterobactin receptor FetA, a vaccine component. Microbiology. 2003;149:1849–1858. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26131-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trotter CL, Chandra M, Cano R, Larrauri A, Ramsay ME, Brehony C, Jolley KA, Maiden MC, Heuberger S, Frosch M. A surveillance network for meningococcal disease in Europe. FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 2007;31:27–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2006.00060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urwin R, Holmes EC, Fox AJ, Derrick JP, Maiden MC. Phylogenetic evidence for frequent positive selection and recombination in the meningococcal surface antigen PorB. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2002;19:1686–1694. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urwin R, Russell JE, Thompson EA, Holmes EC, Feavers IM, Maiden MC. Distribution of Surface Protein Variants among Hyperinvasive Meningococci: Implications for Vaccine Design. Infection and Immunity. 2004;72:5955–5962. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.10.5955-5962.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Dobbelsteen GPJM, van Dijken HH, Pillai S, van Alphen L. Immunogenicity of a combination vaccine containing pneumococcal conjugates and meningococcal PorA OMVs. Vaccine. 2007;25:2491–2496. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsch J, Ram S, Koeberling O, Granoff D. Complement-Dependent Synergistic Bactericidal Activity of Antibodies against Factor H-Binding Protein, a Sparsely Distributed Meningococcal Vaccine Antigen. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2008;197:1053–1061. doi: 10.1086/528994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsch JA, Ram S. Factor H and Neisserial pathogenesis. Vaccine Complement: The First Barrier of Innate Immunity. 2008;26:I40–I45. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.11.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsch JA, Rossi R, Comanducci M, Granoff DM. Protective activity of monoclonal antibodies to genome-derived neisserial antigen 1870, a Neisseria meningitidis candidate vaccine. J Immunol. 2004;172:5606–5615. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.9.5606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson DJ, McVean G. Estimating diversifying selection and functional constraint in the presence of recombination. Genetics. 2006;172:1411–1425. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.044917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Womble DD. GCG: The Wisconsin Package of sequence analysis programs. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2000;132:3–22. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-192-2:3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazdankhah SP, Caugant DA. Neisseria meningitidis: an overview of the carriage state. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2004;53:821–832. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.45529-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazdankhah SP, Kriz P, Tzanakaki G, Kremastinou J, Kalmusova J, Musilek M, Alvestad T, Jolley KA, Wilson DJ, McCarthy ND, Caugant DA, Maiden MC. Distribution of Serogroups and Genotypes among Disease-Associated and Carried Isolates of Neisseria meningitidis from the Czech Republic, Greece, and Norway. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2004;42:5146–5153. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.11.5146-5153.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.