Abstract

Parasites, as with the vast majority of organisms, are dependent on iron. Pathogens must compete directly with the host for this essential trace metal, which is sequestered within host proteins and inorganic chelates. Not surprisingly, pathogenic prokaryotes and eukaryotic parasites have diverse adaptations to exploit host iron resources. How pathogenic bacteria scavenge host iron is well characterized, reasonably well known for a few parasitic protozoa, but is poorly understood for metazoan parasites. Strategies of iron acquisition by schistosomes are examined here, with emphasis on possible mechanisms of iron absorption from host serum iron transporters, or from digested haem. Elucidation of these metabolic mechanisms could lead to the development of new interventions for the control of schistosomiasis and other helminth diseases.

Filling the gaps in metabolic pathways

The recent release of genome sequence information of a range of parasites has provided a plethora of tools for the study of parasite biology [1]. Despite these advances, Scholl and colleagues [2] state that, for the malaria genome at least, there remain many ‘gene gaps’ where little is known of gene control of specific metabolic or development mechanisms. One field of relative ignorance is in how parasites acquire essential trace elements, in particular iron, from their host environment [2]. The gene gaps for malaria become veritable chasms for less intensively studied metazoan parasites, such as schistosomes. Although schistosomes are known to have strong dependence on trace metals, little is known of the acquisition biology of the elements. Adult schistosomes live in and feed on the iron-rich environment of host blood [3, 4]. However, newly penetrant schistosomules absorb iron before their gut is differentiated [4], implicating the parasite surface in iron acquisition, as occurs with many other small molecular weight serum components [5]. It is likely that iron acquisition from the host environment constitutes a critical factor in parasite survival, one that has the potential to be exploited by therapeutics.

Iron: an element essential for life

Iron contributes approximately 5% of the Earth’s crust and is a trace requirement for virtually all prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms [6]. The element readily and reversibly transitions between two oxidation states, Fe2+ (ferrous) and Fe3+ (ferric). This property has enabled eukaryotes and prokaryotes to use iron for many crucial biological reactions [6]. Iron forms the active centre of numerous diverse proteins, including ribonucleotide reductase, mitochondrial aconitase, and haem-containing proteins, such as the cytochromes and iron-sulfur (Fe-S) proteins of the electron transport chain [7]. Iron confers oxygen binding ability to haem moieties of haemoglobin (Hb) and myoglobin, and iron-containing proteins are central to the metabolism of collagen, tyrosine and catecholamines [7-9] and for innate and acquired immunological responses in mammals. Despite its essential role in diverse reactions, iron, if not appropriately chelated, can convert oxygen to toxic free radical species by the iron-catalyzed Haber-Weiss and Fenton reactions. These reactive oxygen radicals are able to attack membrane lipids, proteins and DNA [6, 8]. Iron therefore presents a dilemma for living systems - although essential for life, it is also harmful. This paradox has led to the evolution of sophisticated mechanisms for regulating the absorption, transport, and storage of cellular iron [7]. Iron homeostasis is most tightly regulated at uptake [8]. There are extensive data on iron uptake, transport and regulation in prokaryotes, plants, yeast and vertebrates. By contrast, the mechanisms of iron accumulation in parasites, particularly parasitic helminths, are neglected.

Iron: a limiting factor in pathogen invasion

Tight regulation of iron in mammalian hosts presents an obstacle to invading pathogens, which also require this essential element. Hosts bind iron in proteins or inorganic chelates, and present an iron-restricted environment to pathogenic bacteria and parasites. Indeed, hosts ‘withhold’ iron as an integral strategy of innate immunity [10] and host-pathogen competition for the element is a deciding factor in the success of infection [10, 11]. Microbial pathogens, consequently, have evolved efficient mechanisms to exploit host iron sources. Most iron circulating in mammalian blood is either in the form of haem (bound in haemoglobin within erythrocytes) or reversibly bound to glycoprotein carriers such as transferrin. In addition to these primary resources, invading pathogens use a diverse range of host molecules for iron [12] (Box 1).

Box 1. Potential iron sources from the host available for scavenging by pathogens.

Transferrin - A glycoprotein in blood that binds and transports two ferric ions with high affinity

Non-transferrin bound iron (NTBI) - As the name suggests, this includes all forms of iron not bound in transferrin, and can include iron that is weakly complexed to molecules such as albumin, citrate, amino acids and sugars

Haemoglobin - An iron-containing protein pigment of red blood cells, functioning primarily in the transport of oxygen from the lungs to the body tissues

Haptoglobin/haemoglobin complexes - A protein in the blood that binds free haemoglobin released from erythrocytes with high affinity and thereby inhibits its oxidative activity

Haemopexin/haem complexes - A serum glycoprotein that binds haem and transports it to the liver for breakdown and iron recovery

Ferritin - A globular protein complex consisting of 24 protein subunits that is the main intracellular iron storage protein

Lactoferrin - Belongs to the transferrin family of proteins and is found in milk, mucosal surfaces and secretions such as tears and saliva

Myoglobin - A monomeric haem protein found mainly in muscle tissue where it serves as an intracellular storage site for oxygen.

Iron uptake in pathogenic prokaryotes

Strategies for iron acquisition from hosts have been studied extensively for prokaryotic pathogens [12]. Uptake mechanisms include the synthesis of siderophores to bind Fe3+, and production of specific ligands to entrap and strip host iron carriers (Table 1). One iron-entrapment strategy commonly employed involves the targeted use of proteases and reductases to cleave and reduce bound iron to free Fe2+ for internalization by a range of transporters[12]. Pathogenic members of the Pasteurellaceae and Neisseriaceae acquire iron directly from host transferrin by means of specific receptor-mediated uptake [13-15]. Prokaryote iron uptake is regulated post-transcriptionally in response to iron availability. Usually, iron transporters are detectable only when the bacteria are under iron-restricted conditions [12, 14]

Table 1. Summary of iron uptake mechanisms in prokaryotes [12].

| Proteina | Mechanism and target iron sourceb | Organism |

|---|---|---|

| Siderophores – e.g. coprogen, ferrichrome, enterobactin and rhodotorulic acid |

Low molecular mass iron chelators synthesised and secreted by bacteria to bind ferric iron. |

Gram-negative bacteria. Escherichia coli is the model. |

| FepA, FecA and FhuA | Outer membrane siderophore receptors. Transport through the outer membrane is mediated by an energy transducing TonB-ExbB-ExbD protein complex. |

E. coli and other Gram- negative bacteria |

| FhuD, FepD, FepG | Transport of siderophores across the periplasm and the cytoplasmic membrane; also uses ABC permeases to facilitate uptake. |

E. coli and other Gram- negative bacteria. |

| FeoA, FeoB | Ferrous iron transporters. Important during low oxygen conditions when ferrous iron is more predominant than ferric iron. Although reductase activity facilitates this action, no specific proteins have been identified. |

E. coli, Salmonella, Helicobacter pylori |

| SfuABC, SitABCD, FbpABC |

Metal-type ABC transporters. Transport ferrous iron. |

Serratia marcescens, Salmonella typhimurium, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, |

| Tbp1, Tbp2, Lbp1, Lbp2 |

Outer membrane receptors for host transferrin and lactoferrin. |

Pasteurellaceae, Neisseriaceae, Haemophilus spp. |

| IsdC, DppBCDF, HbpA | Haem iron transporters. Use haem, haemoglobin or the haemopexin complex. Gram-negative bacteria require TonB protein complex for transport and ABC permeases. |

Bacillus anthracis, E. coli, Haemophilus influenzae |

| Fur | Iron regulator. Controls the expression of iron uptake proteins post- transcriptionally in response to iron availability. |

Model organism is E. coli. Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Bacillus subtilis |

Abbreviations: Fep, Ferric enterobactin protein; Fec, Ferric citrate binding; Fhu, Ferrihydroxamate binding; Feo, Fe-oxidising protein; Sfu, Serratia ferrous uptake protein; Sit, Samonella iron transporter; Fbp, Ferric binding protein; Tbp, Transferrin binding protein; Lbp, Lactoferrin binding protein; Isd, Iron-regulated surface determinant; Dpp, Dipeptide permease; Hbp, Haem binding protein; Fur, Ferric uptake regulator protein.

Abbreviation: ABC, ATP-binding cassette.

Iron uptake in parasitic Protozoa

Iron uptake strategies of parasitic protozoans are summarised in Table 2. As is also observed for some pathogenic bacteria, the intracellular location of some protozoans presents those species with major obstacles of iron restriction that the parasites must overcome [16]. Iron is essential for growth of Leishmania, Plasmodium, Trichomonas and Trypanosoma species in vitro, and this development can be disrupted by administration of iron chelators [17]. Although transferrin receptors have been preliminarily identified for all these protozoan genera, the former two have not held up in further investigations [17, 18]. Molecular characterization of a transferrin receptor exists only for Trypanosoma [19].

Table 2. Summary of iron sources and strategies of uptake in parasitic protozoa.

| Organism | Iron Source(s)a |

Mechanismb |

|---|---|---|

| Trypanosoma brucei | Tf | A specific receptor-mediated uptake. The receptor is a 50-60 kDa heterodimer, and its monomers are encoded by two homologous genes: ESAG6 and ESAG7. This complex binds host Tf and endocytoses into the flagellar pocket for processing. [19, 51]. |

| Trichomonas vaginalis | Lf and Hb | Lf uptake occurs via a specific non-saturable 136 kDa receptor [17]. Hb is utilised as iron source in vitro. Non-saturable binding of Hb indicates possible receptor. [17] |

| Leishmania chagasi | Tf and Hb | A Tf receptor was initially proposed [52], however, it has since been found to be non-specific [17]. An uncharacterised ferrous iron transporter might act in tandem with a reductase to facilitate uptake from Tf [18]. Hb can promote growth in vitro, but there is no identified uptake mechanism [17] |

| L. amazonensis | ? | LIT1 facilitates ferrous iron uptake in amastigotes. The biological iron source is not confirmed [20]. Use of Tf or Hb would require cleavage from the protein and reduction to the ferrous form. |

| Plasmodium spp. | ? | Rodriguez proposed that Plasmodium induces uptake of Tf receptor across the erythrocyte plasma membrane[53] but numerous groups have found that Plasmodium cannot access Tf-bound iron [17]. Haem-bound iron is also ruled improbable, with iron from the cytosolic pool in erythrocytes the most likely iron source [2]. |

Abbreviations: Tf, Transferrin; Lf, Lactoferrin; Hb, Haemoglobin

Abbreviations: ESAG, Expression Site-Associated Genes; LIT1. Leishmania Iron Transporter 1.

For intracellular parasites, such as Leishmania and Plasmodium, iron uptake might be mediated through breakdown of haem or by ferrous iron uptake of cytosolic iron (Table 2). It is known that incubation of L. chagasi in the presence of bathophenanthroline, which chelates Fe2+ but not Fe3+, inhibits iron uptake. Leishmania likely cleaves iron from host transferrin using a ferric reductase, and internalises this iron via a ferrous iron transporter [18]. In support of this hypothesis, it has been recently shown that Leishmania amazonesis amastigotes express a Fe2+ iron transporter 1 (LIT1) [20]. LIT1 promoted iron transport in LIT1 null amastigotes and endogenous LIT1 was upregulated in normal amastigotes cultured in iron deprived media. Furthermore, LIT1 deficient amastigotes were unable to replicate in macrophages and were avirulent in mice [20]. Trichomonads grown in iron-deficient medium also lose virulence [21], indicating that iron transporters are important virulence factors for these flagellates.

Iron uptake in metazoans

Apart from the well characterised iron metabolism pathways of mammals [7, 9, 22] knowledge of metazoan iron homeostasis is limited. Some data exist for the iron-related proteins of insects [23], but these data are mostly related to the biology of transferrins and ferritins, and not molecules for iron uptake [24]. An emerging field is in the understanding of haem acquisition and breakdown mechanisms of haematophagous metazoans. Many blood-feeding insects engorge on blood, and the abundance of reactive haem is problematic. The triatomine hemipteran Rhodnius prolixus, for example, processes haem, not by the classical pathways resulting in biliverdin (BV) IX, Carbon Monoxide (CO), and iron, but by unique reactions resulting in dicysteinyl-BV IXgamma, CO and iron [25]. Some of the haem is absorbed by the parasite and can be catabolised. Interestingly, iron produced from haem degradation is stored, in the presence of ferritin, in mid-gut and pericardial cells of the insect [25]. These findings raise the possibility that haem is a major source of iron in haematophagous metazoans. However, for helminths, this hypothesis requires the presence of haem oxygenases (HO) capable of liberating iron from haem, which have yet to be identified in worm genomes [26].

Roundworms and flatworms possess haem-containing proteins, but are said to lack the biosynthetic machinery for haem [26]. These data arise from biochemical assays of haem-synthesis in a range of free-living and parasitic helminths, including Schistosoma mansoni. Rao and colleagues [26] suggest that helminths scavenge haem from dietary or environmental sources. In the case of schistosomes, the gastrodermal lumen represents a major source of haem, most of which is sequestered in haematin [27]. It is noteworthy that sequences for known enzymes of haem biosynthesis, such as δ–aminolevulinic acid dehydratase (ALAD) and porphobilinogen deaminase (PBGD), have been reported for the schistosome expressed sequence tag (EST) datasets [28, 29], suggesting that these helminths, at least, have a capacity to make haem. Whether the source of haem for haematophagous helminths is by de novo synthesis or salvage is an unresolved and intriguing question. It also remains to be determined if helminths can salvage iron from haem through action of HO.

Iron and schistosomes

There is solid evidence that iron is used by schistosomes for development and reproduction, most probably from iron transporters, such as Tf, which are abundant in host serum. Schistosomes sequester iron in the gastrodermal lumen [3], held largely in haem and haematin [27]. In addition, extensive iron is stored within isoforms of the highly conserved iron storage protein ferritin. One isoform, Fer-2, is typical of somatic tissues, the other, Fer-1, occurs as an abundant component of yolk platelets of vitelline cells (eggshell precursors and possible yolk cells) [30, 31]. Female schistosomes express 15-fold more Fer-1 than males, but equal amounts of Fer-2 occur in both sexes [31, 32]. Roles for this abundant egg-associated iron store include early embryogenesis [31], and in stabilization of cross-linked proteins in eggshell formation [32].

Transferrin (Tf) and non-transferrin-bound iron (NTBI) stimulate the growth of schistosomula in vitro [4]. The stimulatory effects of NTBI can be reversed in the presence of the iron chelator desferroxamine. Schistosomes, therefore, might acquire iron through Tf-dependent and Tf-independent mechanisms (Figure 1). Tf binding by the tegument is non-saturable and non-specific [4], precluding the action of specific Tf-receptors, in contrast to mammalian cells and trypanosomes. Schistosoma mansoni expresses two isoforms of a divalent metal transporter (DMT) with significant sequence similarity to the mammalian ferrous iron uptake protein DMT1 (also known as Nramp2) [33]. Notably, schistosome DMT1 has been localised to the tegument and not the gastrodermis. This localization pattern complements in vitro studies of iron uptake in schistosomes conducted by Clemens and Basch, which suggested that iron uptake is surface-mediated and most likely from serum transporters [4]. Despite their high sequence identity to mammalian proteins, neither the schistosome ferritins nor the DMT1 sequences possess the regions associated with post-transcriptional iron regulation that are found in the homologous mammalian sequences [33, 34]. As DMT transports Fe2+, which is relatively insoluble at physiological pH [7], it is likely that ferric reductase is required for iron uptake, but none has been identified.

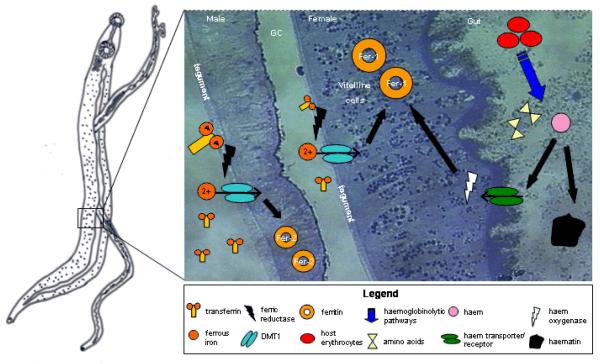

Figure 1. Pumping iron: hypothesised iron uptake mechanisms in schistosomes.

Pumping iron: hypothesized iron uptake mechanisms in schistosomes.

Iron uptake at the schistosome tegument is proposed to occur via non-specific binding of the host iron-carrier protein, transferrin (Tf). Ferric (Fe3+) iron is cleaved from Tf and reduced to its ferrous (Fe2+) form by ferric reductase. Ferrous iron is then transported by a divalent metal transporter (DMT1). The second hypothesized mode of iron acquisition uses haem. Haem is obtained as a by-product of blood-feeding from the breakdown of host erythrocytes by a haemoglobinolytic pathway. The resulting products from this are amino acids for nutrition, and haem. Hypothesized haem uptake is via a haem transporter in the gastrodermis, haem is then catabolized by haem oxygenase to release the iron. Excess haem is sequestered in haematin and egested from the gut. Iron taken up by the helminth is stored in ferritin (Fer); Fer-1 in the vitelline cells of females and Fer-2 in general somatic tissues. Abbreviations: GC, gynecophoric canal.

Renewed interest in haem acquisition in metazoan parasites raises the question whether schistosomes can use host haem for synthesis of haemoproteins, or as a source of iron. The gastrodermis is enriched in haem by virtue of haemoglobinolytic pathways [5]. It was thought that schistosomes, like other human parasites, have no capacity to digest haem, voiding it from the gut as haematin by regurgitation. There is no in silico evidence that haem is catabolized to release iron, as there are no ESTs representing HO in the published in schistosome EST databases [28, 29]. One research group, however, has described HO activity for S. japonicum [35], but this requires confirmation. Given the accumulating data on haem-dependent iron uptake in metazoans [22, 25], and the reasonable hypothesis that the excess haem in the schistosome gut could act as a source of iron, a search for haem utilization mechanisms is warranted.

Therapies targeting iron transport

It is clear that iron is essential for growth and maintenance of schistosomes. Iron uptake transporters and receptors are implicated in pathogen virulence and immunogenicity [36, 37] and are generally surface located, making them favourable drug or vaccine targets. Recently, bacterial iron transporters of the outer membrane of pathogenic bacteria have been tested as potential vaccine targets with promising results [38-41]. Vaccine trials of recombinant S. japonicum Fer-1 in experimental schistosomiasis [42] produced only moderate protection, as expected for an intracellular protein contained within organelles. The DMTs identified in S. mansoni show significant overall homology to mammalian DMTs [33]. However, there are regions within the sequence with limited sequence identity, and these could be targeted for vaccine development. The evidence that iron plays an integral role in egg shell formation [32] means that vaccination against iron homeostasis targets could disrupt the formation of eggs, as well as the pathology and morbidity associated with egg deposition. Because adult worms alone cause no pathology and do not replicate within their mammalian hosts, targeting egg production is a desirable approach for vaccine development [43].

Another strategy for parasite control might include the use of chemotherapeutics targeted at iron uptake and regulation. The artemisinin drug family have shown to be effective against both schistosomiasis and malaria [44, 45]. Although the mode of action of this group of drugs is still under investigation, there is evidence that the antiparasitic activity is iron-dependent [46-48]. The uses of iron chelators is best documented in the treatment of malaria, but they have been proposed as potential chemotherapeutic agents against other parasitic diseases [49]. In vitro, iron chelators halt the growth of schistosomes and protozoan parasites [4, 17, 50].

Concluding remarks

Although the amount of data on iron assimilation in schistosomes is growing, there remain significant gaps and inconsistencies in our knowledge (Box 2). In addition, there is no information on iron uptake and metabolism in other parasitic helminths. It is clear that iron uptake and metabolism in schistosomes represent novel areas for study. The varied nature of iron uptake mechanisms provides numerous putative targets against which novel therapies could be directed. Elucidating how iron homeostasis and other metabolic processes differ from mammalian host cells is not only important for the development of new control strategies, but will also expand our knowledge of parasite biology.

Box 2. Outstanding questions concerning schistosome iron uptake.

Do schistosomes acquire iron directly from host transferrin?

What is the identity of the ferric reductase(s) that provides ferrous iron to DMT1?

Is haemoglobin digestion the primary source of iron for schistosomes: if so by what mechanism?

Do schistosomes have post-transcriptional regulation of iron uptake similar to that seen in prokaryotes and mammalian cells?

Acknowledgements

The authors are supported by grants from the NHMRC of Australia and the Wellcome Trust (ICRGS Award).

References

- 1.Wilson RA, et al. ’Oming in on schistosomes: prospects and limitations for post-genomics. Trends Parasitol. 2007;23:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scholl PF, et al. Bioavailable iron and heme metabolism in Plasmodium falciparum. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2005;295:293–324. doi: 10.1007/3-540-29088-5_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WoldeMussie E, Bennett JL. Plasma spectrometric analysis for Na, K, Ca, Mg, Fe, and Cu in Schistosoma mansoni and S. japonicum. J Parasitol. 1982;68:48–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clemens LE, Basch PF. Schistosoma mansoni: effect of transferrin and growth factors on development of schistosomula in vitro. J Parasitol. 1989;75:417–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smyth J, Halton DW. The Physiology of Trematodes. Cambridge University Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richardson DR, Ponka P. The molecular mechanisms of the metabolism and transport of iron in normal and neoplastic cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1331:1–40. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4157(96)00014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aisen P, et al. Chemistry and biology of eukaryotic iron metabolism. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2001;33:940–959. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(01)00063-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Silva DM, et al. Molecular mechanisms of iron uptake in eukaryotes. Physiol Rev. 1996;76:31–47. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1996.76.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chung J, Wessling-Resnick M. Molecular mechanisms and regulation of iron transport. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2003;40:151–182. doi: 10.1080/713609332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marx JJ. Iron and infection: competition between host and microbes for a precious element. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2002;15:411–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jurado RL. Iron, infections, and anemia of inflammation. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:888–895. doi: 10.1086/515549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andrews SC, et al. Bacterial iron homeostasis. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2003;27:215–237. doi: 10.1016/S0168-6445(03)00055-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bahrami F, et al. Iron acquisition by Actinobacillus suis: identification and characterization of transferrin receptor proteins and encoding genes. Vet Microbiol. 2003;94:79–92. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(03)00082-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perkins-Balding D, et al. Iron transport systems in Neisseria meningitidis. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2004;68:154–171. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.68.1.154-171.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ekins A, et al. Haemophilus somnus possesses two systems for acquisition of transferrin-bound iron. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:4407–4411. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.13.4407-4411.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marquis JF, Gros P. Intracellular Leishmania: your iron or mine? Trends Microbiol. 2007;15:93–95. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilson ME, Britigan BE. Iron acquisition by parasitic protozoa. Parasitol Today. 1998;14:348–353. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(98)01294-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilson ME, et al. Leishmania chagasi: uptake of iron bound to lactoferrin or transferrin requires an iron reductase. Exp Parasitol. 2002;100:196–207. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4894(02)00018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steverding D. The transferrin receptor of Trypanosoma brucei. Parasitol Int. 2000;48:191–198. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5769(99)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huynh C, et al. A Leishmania amazonensis ZIP family iron transporter is essential for parasite replication within macrophage phagolysosomes. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2363–2375. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ryu JS, et al. Effect of iron on the virulence of Trichomonas vaginalis. J Parasitol. 2001;87:457–460. doi: 10.1645/0022-3395(2001)087[0457:EOIOTV]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shayeghi M, et al. Identification of an intestinal heme transporter. Cell. 2005;122:789–801. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nichol H, et al. Iron metabolism in insects. Annu Rev Entomol. 2002;47:535–559. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.47.091201.145237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dunkov B, Georgieva T. Insect iron binding proteins: insights from the genomes. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2006;36:300–309. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paiva-Silva GO, et al. A heme-degradation pathway in a blood-sucking insect. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:8030–8035. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602224103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rao AU, et al. Lack of heme synthesis in a free-living eukaryote. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:4270–4275. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500877102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Correa Soares JB, et al. Extracellular lipid droplets promote hemozoin crystallization in the gut of the blood fluke Schistosoma mansoni. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:1742–1750. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Verjovski-Almeida S, et al. Transcriptome analysis of the acoelomate human parasite Schistosoma mansoni. Nat Genet. 2003;35:148–157. doi: 10.1038/ng1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hu W, et al. Evolutionary and biomedical implications of a Schistosoma japonicum complementary DNA resource. Nat Genet. 2003;35:139–147. doi: 10.1038/ng1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dietzel J, et al. Ferritins of Schistosoma mansoni: sequence comparison and expression in female and male worms. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1992;50:245–254. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(92)90221-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schussler P, et al. An isoform of ferritin as a component of protein yolk platelets in Schistosoma mansoni. Mol Reprod Dev. 1995;41:325–330. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1080410307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones MK, et al. Tracking the fate of iron in early development of human blood flukes. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39:1646–1658. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smyth DJ, et al. Two isoforms of a divalent metal transporter (DMT1) in Schistosoma mansoni suggest a surface-associated pathway for iron absorption in schistosomes. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:2242–2248. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511148200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schussler P, et al. Ferritin mRNAs in Schistosoma mansoni do not have iron-responsive elements for post-transcriptional regulation. Eur J Biochem. 1996;241:64–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0064t.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu WQ, et al. Studies on the activity and immunohistochemistry of heme oxygenase in Schistosoma japonicum. Zhongguo Ji Sheng Chong Xue Yu Ji Sheng Chong Bing Za Zhi. 2001;19:84–86. In Chinese. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Forbes JR, Gros P. Divalent-metal transport by NRAMP proteins at the interface of host-pathogen interactions. Trends Microbiol. 2001;9:397–403. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(01)02098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koster W. ABC transporter-mediated uptake of iron, siderophores, heme and vitamin B12. Res Microbiol. 2001;152:291–301. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(01)01200-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gat O, et al. Search for Bacillus anthracis potential vaccine candidates by a functional genomic-serologic screen. Infect Immun. 2006;74:3987–4001. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00174-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jomaa M, et al. Immunization with the iron uptake ABC transporter proteins PiaA and PiuA prevents respiratory infection with Streptococcus pneumoniae. Vaccine. 2006;24:5133–5139. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kuklin NA, et al. A novel Staphylococcus aureus vaccine: iron surface determinant B induces rapid antibody responses in rhesus macaques and specific increased survival in a murine S. aureus sepsis model. Infect Immun. 2006;74:2215–2223. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.4.2215-2223.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sun Y, et al. Identification of novel antigens that protect against systemic meningococcal infection. Vaccine. 2005;23:4136–4141. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen LY, et al. Mucosal immunization of recombinant Schistosoma japonicum ferritin. Zhongguo Ji Sheng Chong Xue Yu Ji Sheng Chong Bing Za Zhi. 2004;22:129–132. In Chinese. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McManus DP. Prospects for development of a transmission blocking vaccine against Schistosoma japonicum. Parasite Immunol. 2005;27:297–308. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2005.00784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Olliaro PL, Taylor WR. Developing artemisinin based drug combinations for the treatment of drug resistant falciparum malaria: A review. J Postgrad Med. 2004;50:40–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shuhua X, et al. Artemether, an effective new agent for chemoprophylaxis against shistosomiasis in China: its in vivo effect on the biochemical metabolism of the Asian schistosome. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2000;31:724–732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sibmooh N, et al. Redox reaction of artemisinin with ferrous and ferric ions in aqueous buffer. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 2001;49:1541–1546. doi: 10.1248/cpb.49.1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xiao S, et al. Artemether administered together with haemin damages schistosomes in vitro. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2001;95:67–71. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(01)90336-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xiao SH, et al. Schistosoma japonicum: In vitro effects of artemether combined with haemin depend on cultivation media and appraisal of artemether products appearing in the media. Parasitol Res. 2003;89:459–466. doi: 10.1007/s00436-002-0786-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smith HJ, Meremikwu M. Iron chelating agents for treating malaria. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001474 ( http://www.cochrane.org/index.htm) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Breidbach T, et al. Growth inhibition of bloodstream forms of Trypanosoma brucei by the iron chelator deferoxamine. Int J Parasitol. 2002;32:473–479. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(01)00310-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gerrits H, et al. The physiological significance of transferrin receptor variations in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2002;119:237–247. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(01)00417-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Voyiatzaki CS, Soteriadou KP. Evidence of transferrin binding sites on the surface of Leishmania promastigotes. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:22380–22385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rodriguez MH, Jungery M. A protein on Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes functions as a transferrin receptor. Nature. 1986;324:388–391. doi: 10.1038/324388a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]