Abstract

A fluorous-tagged “safety catch” linker is described for the synthesis of heterocycles with use of ring-closing metathesis. The linker facilitiates the purification of metathesis substrates, the removal of the catalyst, the functionalization of the products, and the release of only metathesis products. The synthesis of a range of heterocycles is described.

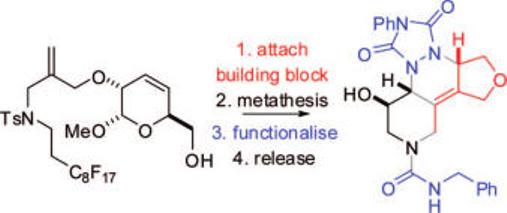

Ring-closing metathesis has revolutionalized organic synthesis.1 Ruthenium complexes are particularly functional group tolerant,2 but the catalyst residues often need to be scavenged.3 Recently, we developed a fluorous-tagged linker for synthesizing heterocycles by metathesis but a fluorous-tagged catalyst was needed to allow easy product purification.4 We now describe a fluorous-tagged “safety catch”5 linker that facilitates the synthesis, purification, and functionalization of metathesis products without the use a fluorous-tagged catalyst (Scheme 1). We use the term “linker” to describe compounds (e.g., 1) which are functionalized to yield metathesis substrates (e.g., 2).

Scheme 1.

Design of the Fluorous-Tagged “Safety Catch” Linker 1

It was envisaged that functionalization of 1 (→ 2) would be followed by removal of excess reagents by fluorous-solid phase extraction6 (F-SPE). Initiation of a metathesis cascade would be expected at the terminal alkene7 of 2 (→ 3). Cyclization (→ 4) would be followed by a second ring-closing metathesis (→ 5) in which a catalytically active methylene complex was regenerated.8 Crucially, the product 5 would still be fluorous-tagged; F-SPE would thus allow removal of the metathesis catalyst and removal of the excess reagents in subsequent functionalization steps. Finally, acetal cleavage would release only metathesis products (e.g., 6) (and not unreacted substrates such as 2) from the fluorous tag. The fluorous-tagged linker 1 was, therefore, designed to be a “safety catch”5 linker since the cleavage step should release only metathesis products.

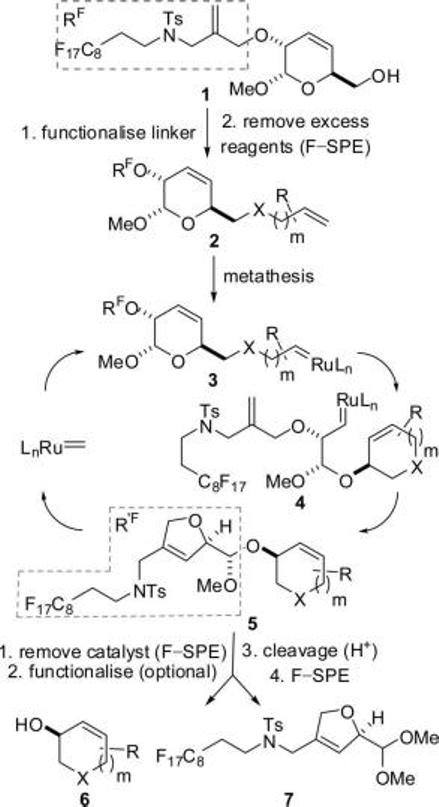

To validate the design, we prepared the trienes 8 and 9 from a known glucose derivative (see the Supporting Information). Treatment of 8 and 9 (4 mM in CH2Cl2) with 6 mol % Grubbs’s second generation catalyst gave the expected metathesis products 10 and 11 (Scheme 2). Thus, irrespective of the initiation site,7 the metathesis cascade proceeded smoothly, cleaving the central dihyropyran ring. The study validated the “safety catch” linker design since hydrolysis of the resulting acyclic acetals would yield the required dihydropyran products.

Scheme 2.

Validation of the Design of the Linker 1a

a GII is Grubbs’s second generation catalyst.

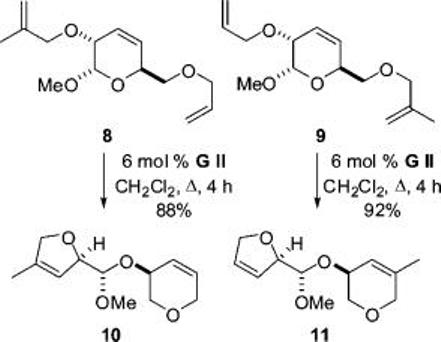

Scheme 3 describes the synthesis of the linkers 1 and 18. Reaction of the anion of 12 with ethyl α-bromomethyl acrylate,9 and reduction, gave the allylic alcohol 13. A Fukuyama–Mitsunobu reaction10 between 13 and the sulfonamide4 14, and deprotection, gave the fluorous-tagged linker 1. Finally, Fukuyama–Mitsunobu reaction with Ns-BocNH, and deprotection, gave the fluorous-tagged sulfonamide 18.

Scheme 3.

Preparation of the Fluorous-Tagged Linkers 1 and 18a

a For the definition of RF, see Scheme 1.

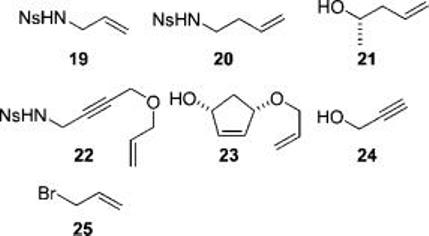

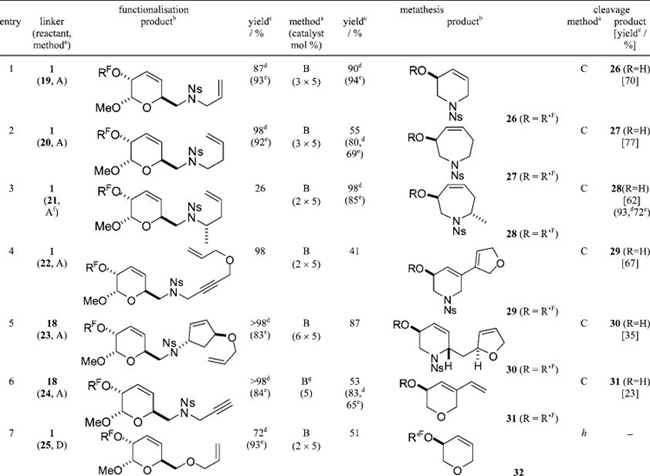

The linkers 1 and 18 were functionalized with a range of reactants (see Figure 1, Table 1, and the Supporting Information). Thus, the substrates were prepared by using the Fukuyama–Mitsunobu reaction,10 allylation, silaketal formation,11 or esterification. In general, the fluorous-tagged products were purified by F-SPE alone, and the purities were determined by HPLC.

Figure 1.

Reactants used to derivatize the linkers 1 and 18.

Table 1.

Heterocycle Synthesis by Functionalization of the Linker, Metathesis, and Release (See Scheme 1 for the Definitions of RF and R′F)

Method A: reactant (4 equiv), PPh3 (4 equiv), DEAD (4 equiv), THF, rt then F-SPE. Method B: (i) Hoveyda–Grubbs second generation catalyst, CH2Cl2, reflux; (ii) P(CH2OH)3, Et3N then silica; (iii) F-SPE. Method C: 3% TFA in CH2Cl2, rt then F-SPE. Method D: (i) NaH, THF, 0 °C; (ii) allyl bromide, rt; (iii) MeOH then F-SPE

See Scheme 1 for the definitions of RF and R′F.

Unless otherwise stated, isolated yield of product.

Mass of product after F-SPE.

Purity (%) determined by HPLC after F-SPE.

10 equiv of the sulfonamide, PPh3, and DEAD were used.

In the presence of an ethylene atmosphere.

Not undertaken.

The cascade reactions of a range of the metathesis substrates were successful (Table 1). Six- and seven-membered nitrogen and oxygen heterocycles were formed in good to excellent yield. In the case of the terminal alkyne substrate (entry 6), the reaction was performed under an ethylene atmosphere,12 and a 53% yield of the fluorous-tagged product 31 (R = R′F) was obtained. More complex cascade reactions in which two new heterocyclic rings were formed were also successful (entries 4 and 5). Unlike with our previous linker,4 it was not possible to prepare eight- or nine-membered heterocycles (see the Supporting Information for the substrates studied); instead, dimerization was competitive with cyclization and, hence, release from the linker. Six metathesis products [26-31 (R = H)] were released directly from the linker by treatment of the correponding metathesis products with 3% TFA in CH2Cl2 (entries 1-6, Table 1).

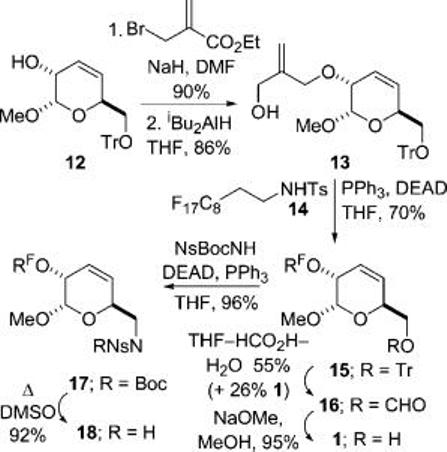

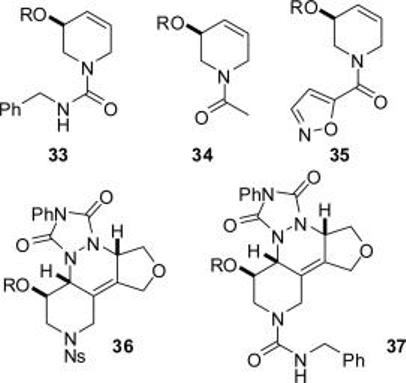

The metathesis products could also be functionalized before release from the fluorous tag (see Table 2 and Figure 2). In each case, the excess reagents were removed by F-SPE only. Thus, removal of the o-nitrophenylsulfonyl group from 26 (R = R′F), derivatization, and release from the fluorous tag yielded the tetrahydropyridines 33 (R = H), 34 (R = H), and 35 (R = H) (entries 1-3). Alternatively, the diene 29 (R = R′F) underwent efficient Diels–Alder reaction with 4-phenyl-[1,2,4]-triazole-3,5-dione to yield 36 (R = R′F): the resulting adduct could either be released directly from the fluorous tag [→ 36 (R = H), entry 4] or after deprotection and derivatization [→ 37 (R = H), entry 5].

Table 2.

Functionalisation of the Metathesis Products and Release from the Fluorous Taga

| entry | starting material | purity/% | functionalization methodb | product | mass recoveryc/% (purityd/%) | cleavage methodb | product | yielde/% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 26 (R = R′F) | 94 | A | 33 (R = R′F) | 87 (>90) | B | 33 (R = H) | 82 |

| 2 | 26 (R = R′F) | 94 | C | 34 (R = R′F) | B | 34 (R = H) | 67f | |

| 3 | 26 (R = R′F) | >99 | E | 35 (R = R′F) | B | 35 (R = H) | 57f | |

| 4 | 29 (R = R′F) | >99 | D | 36 (R = R′F) | 86 (87) | B | 36 (R = H) | 59 |

| 5 | 36 (R = R′F) | 87 | A | 37 (R = R′F) | 79 (>95) | B | 37 (R = H) | 67 |

See Scheme 1 for the definition of R′F.

Method A: (i) PhSH, DBU, MeCN; (ii) BnNCO; (iii) F-SPE. Method B: (i) 3% TFA in CH2Cl2; (ii) F-SPE. Method C: (i) PhSH, DBU, MeCN; (ii) Ac2O, pyridine; (iii) F-SPE. Method D: (i) 4-phenyl-[1,2,4]-triazole-3,5-dione, CH2Cl2; (ii) F-SPE. Method E: (i) PhSH, DBU, MeCN; (ii) DMAP and isoxazole-5-carbonyl chloride; (iii) F-SPE.

Mass of product after F-SPE only.

Purity (%) determined by HPLC after F-SPE only.

Isolated yield of purified product.

Isolated yield of product over 2 steps.

Figure 2.

Derivatized metathesis products after release from the fluorous tag, R = H.

In summary, we have developed a linker for the synthesis of arrays of heterocylic products using metathesis cascade reactions. The design of the fluorous-tagged linker allowed (a) easy purification of metathesis substrates; (b) easy removal of the catalyst from the metathesis products; (c) functionalization of the products before release; and (d) the release of only metathesis products.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Information Available: Details of all experimental procedures, including unsuccessful metathesis substrates, and NMR spectra for all novel compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgment

We thank the Wellcome Trust, EPSRC, Leeds University and GSK for funding, and Stuart Leach and Daniel Morton (University of Leeds) for discussions.

References

- (1).(a) Deiters A, Martin SF. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:2199. doi: 10.1021/cr0200872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chattopadhyay SK, Karmakar S, Biswas T, Majumdar KC, Rahaman H, Roy B. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:3919. [Google Scholar]; (c) Gradillas A, Péres-Castells J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006;45:6086. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Grubbs RH. Handbook of Metathesis. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim, Germany: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- (3).For example, see: Ahn YM, Yang K, Georg GI. Org. Lett. 2001;3:1411. doi: 10.1021/ol010045k. Maynard HD, Grubbs RH. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:4137. Galan BR, Kalbarczyk KP, Szczepankiewicz S, Keister JB, Diver ST. Org. Lett. 2007;9:1203. doi: 10.1021/ol0631399. Matsugi M, Curran DP. J. Org. Chem. 2005;70:1636. doi: 10.1021/jo048001n. Yao Q, Zhang Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:74. doi: 10.1021/ja037394p.

- (4).(a) Leach SG, Cordier CJ, Morton D, McKiernan GJ, Warriner S, Nelson A. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:2752. doi: 10.1021/jo7026273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Morton D, Leach S, Cordier C, Warriner S, Nelson A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009;48:104. doi: 10.1002/anie.200804486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Patek M, Lebl M. Biopolymers. 1999;47:353. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Zhang W, Curran DP. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:11837. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2006.08.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).(a) Ulman M, Grubbs RH. Organomet. 1998;17:2484. [Google Scholar]; (b) Wallace DJ. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005;44:1912. doi: 10.1002/anie.200462753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Moriggi J-D, Brown LJ, Castro JL, Brown RCD. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2004;2:835. doi: 10.1039/b313686h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Villieras J, Rambaud M. Org. Synth. 1988;66:220. [Google Scholar]

- (10).Fukuyama T, Jow C-K, Cheung M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995;36:6373. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Cordier C, Morton D, Leach S, Woodhall T, O’Leary-Steele C, Warriner S, Nelson A. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2008;6:1734. doi: 10.1039/b804769n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Lloyd-Jones GC, Margue RG, de Vries JG. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005;44:7442. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.