Abstract

The prevalence of food allergies varies by country, as does each country’s food allergen labeling. While labeling laws may vary by country, most follow the Codex Alimentarius. Even developing countries have some degree of labeling guidelines for food allergies, but it is highly developed countries that tend to implement stricter labeling regulations to protect their citizens and tourists. Different organizations, both domestic and international, such as Food Allergy Research and Education (FARE), work to advance food allergen labeling laws around the globe. Eating out and traveling can be anxiety-provoking for people with food allergies, especially when traveling to international destinations. Furthermore, experiences that young children, teenagers, and parents have with food allergies can have psychosocial and social impacts. To evaluate food allergen labeling laws across the globe, official legal documents outlining the laws pertaining to foods and allergen food labeling were reviewed for each respective country or region. These were organized according to continent, then region or country. The majority of countries require that major food groups be listed on food labels, including milk, egg, soy, wheat, peanuts, treenuts, fish, and shellfish. There are individual variations across regions depending on staples in respective diets. With increasing rates of food allergies worldwide, legislative action is needed to ensure that people living with food allergies can more safely purchase and consume foods. Until then, the work of avoiding accidental ingestions and anaphylaxis remains primarily with the individual, who must educate themselves on labeling laws and implement other protective measures.

Keywords: Food allergy, Traveling, Labeling laws, FDA, Countries, Epinephrine, EMA, Airlines, Food allergy action plans, Anaphylaxis, Ingredients

Introduction

Food allergies remain a global problem, and the incidence of food allergies continues to increase, especially in developed countries. Differing definitions of food allergy, influenced by social and cultural perceptions, makes tracking food allergy prevalence, implementing legislation changes, and increasing consumer awareness more complex [1]. In the UK, 101,891 people were hospitalized for anaphylaxis between 1998 and 2018. About 30% of these admissions were due to a food trigger [2]. In the U.S., the prevalence of food allergies in children aged 0–17 increased from 3.4% in 1997–1999 to 5.1% in 2009–2011 [3]. In Canada, a survey conducted by AllerGen indicated that of the children between the ages of 0 and 17, approximately 6.9% were living with food allergies; meanwhile, 7.7% of Canadian adults were reported to be living with food allergies [4]. While the number of hospital admissions and deaths due to issues regarding food labeling remains unknown, several studies over the past two decades have advocated for standardized precautionary allergen labeling and improved awareness of labeling guidelines. A 2017 study surveyed consumers from the U.S. and Canada and concluded that almost half of consumers falsely believed that precautionary allergen labeling was required by law [5]. Even with increased efforts to increase consumer awareness, many consumers do not consult food labels or are unable to interpret the labels accurately [6]. Existing research on the awareness, understanding, and use of food labeling have focused on specific regions and nutrients, such as a 2018 cross-sectional study on sodium information in urban Beijing [7]. Given the impact food allergies have on millions of people around the globe, more decisive action must be taken to protect consumers with food allergies. More precise allergen labeling is needed so people can identify and understand the allergens in the food they consume and purchase.

Methods

Policies and protocols regarding food labeling laws for the countries discussed in this paper were obtained from official government food labeling policy documents for the respective country or region. Illustrations or examples of the way foods are labeled in various regions with specific distinctions are provided. A discussion of the food labeling laws for each country or region is organized across continent, then region, and finally individual countries. Not all countries are discussed, but the discussion does encompass a significant portion of the globe.

Results

International Standards

The Codex Alimentarius, or “Food Code,” is a list of standards and guidelines adopted by the Codex Alimentarius Commission (CAC), part of the Joint Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO)/World Health Organization (WHO) Food Standards Programme constructed to protect consumer health and promote fair food trade practices. The complete list of standards is available for download at the following web page: https://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/codex-texts/list-standards/en/. The General Standard for the Labeling of Prepackaged Foods is a standard established by the Codex Alimentarius and requires that the following be declared on prepackaged foods: name of the food, list of ingredients, name and address of the manufacturer, exporter, importer, packer, distributor or vendor, country of origin, lot identification, and instructions for use [8]. Per the General Standard for the Labelling of Prepackaged Foods, the name of the food should not be misleading. It should state the true nature of the food and be specific. Apart from single-ingredient products, all ingredients should be listed. Paragraph 4.2.1.1 of the General Standard for the Labelling of Prepackaged Foods also states that the term “Ingredient” should be used before the list of ingredients is declared. The ingredients in the ingredient list shall be listed in order of descending weight. When a product has compound ingredients, the ingredients within the compound ingredient shall be immediately declared in brackets [8].

Paragraph 4.2.1.4 also recognizes the following ingredients as allergens and requires them to be declared at all times: “cereals containing gluten; i.e., wheat, rye, barley, oats, spelt or their hybridized strains and products of these; crustacea and products of these; egg and egg products; fish and fish products; peanuts, soybeans, and products of these; milk and milk products (lactose included); tree nuts and tree nut products; and sulphites in concentrations of 10 mg/kg of food or more.” Furthermore, paragraph 4.2.2 of the General Standard for the Labelling of Prepackaged Foods also states that “if it is not possible to provide adequate information on the presence of an allergen through labeling, the product containing the allergen should not be marketed” [8].

Paragraph 4.6 of the document requires that the lot identification information be declared. Paragraph 4.7 requires date marking and storage instructions, providing manufacturers with details on how to specify a product’s expiration date [8]. Paragraph 4.8 lists how the instructions for the use of the product should be declared if necessary [8]. The document states the following regarding exceptions to mandatory allergen labeling: “With the exception of spices and herbs, small units, where the largest surface area is less than 10cm [2], may be exempted from the requirements of paragraph 4.2 and 4.6 to 4.8” [8]. As of March 2022, the Codex Alimentarius Commission consists of 188 Member Countries and 1 Member Organization (The European Union) (Table 1). Despite these guidelines and regulations, each nation’s respective laws vary.

Table 1.

Members of the Codus Alimentarius Commission

| Africa | Asia | Europe | North America | South America | Oceania |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Algeria | Afghanistan | Albania | Antigua and Barbuda | Argentina | Australia |

| Angola | Azerbaijan | Armenia | Bahamas | Bolivia | Cook Islands |

| Benin | Bahrain | Belarus | Barbados | Brazil | Fiji |

| Botswana | Bangladesh | Belgium | Belize | Chile | Kiribati |

| Burkina Faso | Bhutan | Bosnia and Herzegovina | Canada | Columbia | Micronesia |

| Burundi | Brunei Darussalam | Bulgaria | Costa Rica | Ecuador | Nauru |

| Cabo Verde | Cambodia | Croatia | Cuba | Guyana | New Zealand |

| Cameroon | China | Cyprus | Dominica | Paraguay | Papua new Guinea |

| Central African Republic | Democratic People’s Republic of Korea | Czech Republic | Dominican Republic | Peru | Samoa |

| Chad | Georgia | Denmark | El Salvador | Suriname | Seychelles |

| Comoros | India | Estonia | Grenada | Uruguay | Solomon Islands |

| Congo | Indonesia | Finland | Guatemala | Venezuela | Timor-Leste |

| Cota d’Ivoire | Iran | France | Haiti | Tonga | |

| Democratic Republic of Congo | Iraq | Germany | Honduras | Vanautu | |

| Djibouti | Israel | Greece | Jamaica | ||

| Egypt | Japan | Hungary | Mexico | ||

| Equatorial Guinea | Jordan | Iceland | Nicaragua | ||

| Eritrea | Khazakhstan | Ireland | Panama | ||

| Eswatini | Kuwait | Italy | St. Kitts and Nevis | ||

| Ethiopia | Kyrgyzstan | Latvia | Saint Lucia | ||

| Gabon | Lao People’s Democratic Republic | Lithuania | Saint Vincent and the Grenadines | ||

| Gambia | Lebanon | Luxembourg | Trinidad and Tobago | ||

| Ghana | Malaysia | Malta | United States of America | ||

| Guinea | Maldives | Montenegro | |||

| Guinea-Bassau | Mongolia | Netherlands | |||

| Kenya | Nepal | Norway | |||

| Lesotho | Oman | Poland | |||

| Liberia | Pakistan | Portugal | |||

| Madagascar | Philippines | Republic of Moldova | |||

| Malawi | Qatar | Romania | |||

| Mali | Republic of Korea | Russian Federation | |||

| Mauritania | Saudi Arabia | San Marino | |||

| Mauritius | Singapore | Serbia | |||

| Morocco | Sri Lanka | Slovakia | |||

| Mozambique | Syrian Arab Republic | Slovenia | |||

| Namibia | Tajikstan | Spain | |||

| Niger | Thailand | Sweden | |||

| Rwanda | Turkey | Switzerland | |||

| Sao Tome and the Principe | Turkmenistan | The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia | |||

| Senegal | United Arab Emirates | Ukraine | |||

| Sierra Leone | Uzbekistan | United Kingdom | |||

| Somalia | Vietnam | ||||

| South Africa | Yemen | ||||

| South Sudan | |||||

| State of Libya | |||||

| Sudan | |||||

| Togo | |||||

| Tunisia | |||||

| Uganda | |||||

| United Republic of Tanzania | |||||

| Zambia | |||||

| Zimbabwe |

North America

Food Labeling Laws in the U.S.

A 2019 study found that at least 1 in 10 adults are food allergic in the United States (U.S.) [9]. As of 2018, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) estimates that about 30,000 Americans are sent to the emergency room because of allergies; 150 die from allergic reactions to food [10]. The FDA is the major U.S. government organization regulating nutrition and allergen information on food products, cosmetics, and drugs. In 1999, research conducted by the FDA on the effects of food allergens in businesses found that in a random selection of sweets, goods, and candies in Wisconsin and Minnesota, 25% of the randomly selected products failed to list peanuts or eggs as allergens on the food labels [10].

The U.S. Congress passed the Food Allergen Labeling and Consumer Protection Act of 2004 (FALCPA) which identifies eight major food allergens: milk, egg, fish, Crustacean shellfish, tree nuts, wheat, peanuts, and soybeans. While Crustacean shellfish are recognized as a major food allergen (such as crab, lobster, or shrimp), molluscan shellfish (such as oysters, clams, mussels, or scallops) are not [11]. While more than 160 foods have been identified to cause food allergies in the U.S., these eight major allergens account for ninety percent of documented food allergies in the U.S. [10]. On April 23, 2021, the Food Allergy Safety, Treatment, Education, and Research (FASTER) Act declared sesame as the ninth major food allergen. The law will become effective on January 1, 2023 [12]. If a product has tree nuts as one of the ingredients, the specific type of nut must be listed. For example, rather than only writing “tree nut,” a manufacturer must write whichever type of nut may be in the product, such as “almond” or “pecan.” The same policy applies to Crustacean shellfish and fish, for which the species must be declared [12].

The U.S. currently requires that companies and manufacturers list their ingredients clearly on packaging (Fig. 1). According to a 2013 Food Labeling Guide published by the FDA, the labeling must be easy to read for consumers [13]. The sizing of the letters is based on the letter “o,” and the letters must be 1/16th of an inch, at the minimum. The height of the letters cannot be more than three times their width. Furthermore, the labeling must not be blocked or crowded with artwork or labeling that is unnecessary. The ingredients are to be listed in descending order of prevalence by weight. Therefore, the ingredient that weighs the most must be listed in the beginning, while the ingredient that weighs the least must be listed towards the end. If a product has an ingredient that consists of other ingredients, the “subingredients,” as the FDA refers to them, must be listed parenthetically. Subingredients can also be listed by “dispersing each ingredient in its order of predominance,” but the original ingredient cannot be listed again [13].

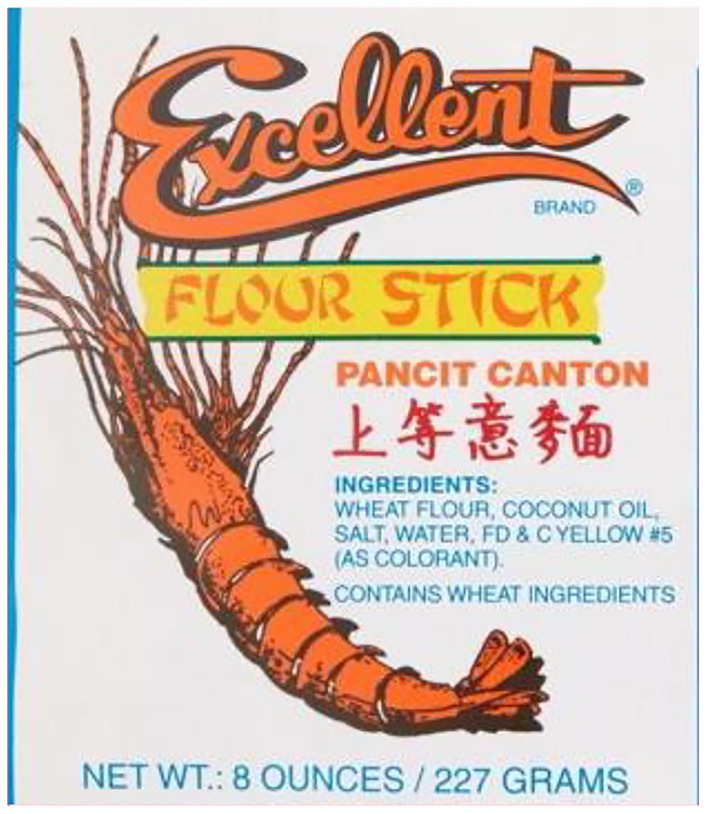

Fig. 1.

U.S. food allergen labeling showing ingredients in decreasing order of amount and allergen labeling of a U.S. food product, provided by author LE

The 2002 and 2008 Farm Bills and the 2016 Consolidated Appropriations Act, which amended the Agricultural Marketing Act of 1946, require retailers to “inform consumers of the country of origin of muscle cuts and ground lamb, chicken, goat, wild and farm-raised fish and shellfish, perishable agricultural commodities, peanuts, pecans, ginseng, and macadamia nuts” [14]. The Perishable Commodities Act of 1930 (PACA) defines “retailers” include any person who sells any perishable agricultural commodity at retail. There are no stipulations on exact size or placement of country of origin declarations, but statements should be “legible and placed in a conspicuous location where they are likely to be read and understood by a customer” [14]. Country of origin labeling statements can be presented in different forms, including a placard, sign, label, sticker, band, twist tie, or pin tag [14]. Abbreviations approved under Customs and Border Protection rules, regulations, and policies are the only abbreviations that can be used in country of origin labeling and must “unmistakably indicate the name of the country of origin” [14]. For example, “P.R. China” and “China” are acceptable abbreviations for the People’s Republic of China. However, “America” is not an acceptable abbreviation because it does not specify whether the country of origin is North America, Central America, or South America [14]. More information on country of origin labeling requirements can be found on the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Agricultural Marketing Service website: https://www.ams.usda.gov/rules-regulations/cool/questions-answers-consumers#:~:text=The%202002%20and%202008%20Farm,and%20shellfish%2C%20perishable%20agricultural%20commodities%2C.

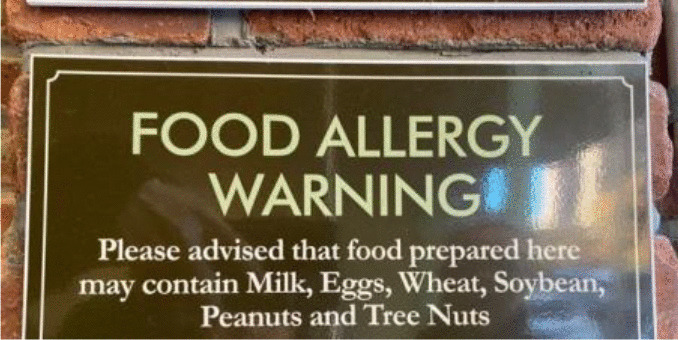

Multiple domestic organizations aim to improve the lives of people with food allergies in the U.S. On November 30, 2016, a review titled Finding a Path to Safety in Food Allergy: Assessment of the Global Burden, Causes, Prevention, Management, and Public Policy was published to examine the “prevalence and severity of food allergy and its impact on affected individuals, families, and communities; and current understanding of food allergy as a disease, and in diagnostics, treatments, prevention, and public policy” [15]. There were several federal sponsors: the Food and Drug Administration, the Food and Nutrition Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and nonfederal sponsors: the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America, the Egg Nutrition Center, Food Allergy Research and Education, the International Life Sciences Institute North America, the International Tree Nut Council Nutrition Research and Education Foundation, the National Dairy Council, the National Peanut Board, and the Seafood Industry Research Fund [15]. Another organization that has had significant involvement in the food allergy community is Food Allergy Research and Education (FARE). Instructions for reading US food labels can be found on the FARE website and are accessible to the public: https://www.foodallergy.org/living-food-allergies/food-allergy-essentials/free-downloadable-resources. Throughout its tenure, FARE has been vital to pushing significant changes in legislation. As a result of their efforts, over one million epinephrine auto-injectors have been provided in K-12 schools. Former U.S. President Barack Obama signed the School Access to Emergency Epinephrine Act into law in 2013. Under the law, schools are encouraged to plan in the event that a severe asthma attack or allergic reaction occurs [16]. States such as Indiana, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Texas, and Virginia also have laws that require colleges to have epinephrine accessible on their campuses. In New York, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia, bus drivers are allowed to administer epinephrine. In Illinois, Massachusetts, Maryland, Rhode Island, and Virginia, restaurants are by law required to train their staff regarding food allergy preparedness. Some restaurants have begun to put up signs with food allergy warnings (Fig. 2). An example of such a sign in a New York City establishment is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

A food allergy warning in a New York City food establishment, provided by author LE

Food Labeling Laws in Canada

The prevention of food allergies has become a public health issue in Canada, with almost 600,000 children under 18 years reported to have food allergies [17]. Canada recognizes the following as substances most frequently associated with food allergies and allergic-type reactions: peanuts, tree nuts, sesame, milk, egg, soy, wheat and triticale, crustaceans and mollusks, mustard, fish, and sulfites [18]. Food Allergy Canada was founded in 2001 with the goal of making it safer for those living with food allergies. The organization has led to changes in Canadian legislation. In 2012, the Canadian government passed legislation requiring manufacturers to list ingredients in pre-packaged foods in common language (Fig. 3). Consequently, companies could no longer label ingredients such as “milk” under the name “casein” as some consumers may not know that casein is milk [19].

Fig. 3.

A label for Perigord Duck Rillettes from Amazon, showing the use of common English terms only

Although Canadian manufacturers can use precautionary statements, Health Canada, the organization responsible for national public health, does not require them to do so. Health Canada also does not regulate precautionary statements. If labeling ingredients run the risk of cross-contamination, companies that add the “may contain” statement must be truthful and not misleading.

In 2003, Sabrina Shannon suffered fatally from an anaphylactic reaction in her first year of high school. Before her death, she advocated for adolescents living with food allergies. In 2005, Sabrina’s law was passed to help children with severe allergies in public schools in Ontario. The law requires that schools implement an anaphylaxis policy to serve students with allergies better. Schools must also construct a plan for each student prone to anaphylaxis. Since the law was passed, schools have created thousands of plans and educational programs catered to their students [20].

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) is dedicated to food safety and works to ensure Canadians are protected from preventable health risks. Manufacturers can label ingredients using either an ingredient list or a “contains” statement. According to the CFIA’s website, if the food contains Canada’s priority allergens, gluten sources, or added sulfites, these ingredients must be listed at least once in the ingredient list and when they are part of an ingredient. A “contains” statement can also be used to identify food allergens, gluten sources, or added sulfites. The “contains” statements must list the allergens regardless of whether they were previously listed in the ingredient list [21].

Health Canada and the CFIA have shared responsibility for monitoring food labeling. Health Canada is responsible for overseeing labeling, claims regarding nutrients, and expiration dates relating to safety. The CFIA regulates labeling, standards of identity, and grades [22]. Regulatory amendments published in the Canada Gazette Part II on December 14, 2016, will change how prepackaged foods are labeled. These amendments dictate that “1. The “contains” statement (if used) will have to comply with legibility requirements as with the list of ingredients and 2. When used, any precautionary allergen statements will have to appear immediately following the list of ingredients or the “contains” statement if one is provided” [23]. The regulatory amendments will make it easier and faster for consumers to find the appropriate allergen information on labels.

South America

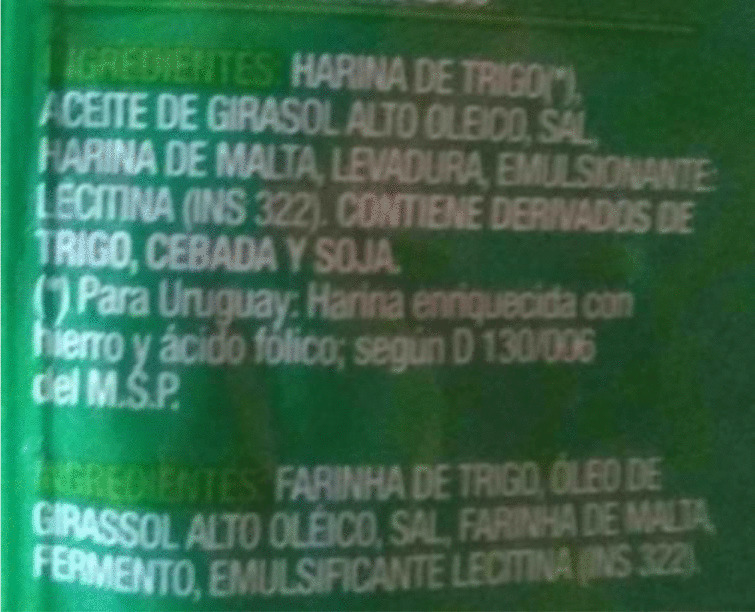

Not much information is available about the prevalence of food allergies in Latin America [24], which may contribute to the variation of food allergen labeling regulations. Some Latin American countries require allergen labeling, while others have no regulations. In recent years, Argentina (Fig. 4) and Brazil (Fig. 5) transitioned into new legislation that would require manufacturers to add food allergen labels to their foods. Examples of labels from Argentina (in Spanish) and Brazil (in English) are illustrated in Figs. 4 and 5, respectively. Colombia and Chile also require mandatory allergen labeling. Mexico, Bolivia, and Peru mostly follow the same guidelines established in Codex Alimentarius [25].

Fig. 4.

A food label from Argentina for veganeamos. bizcochos 9 de oro light — 170 g from open food facts; 2020. Notice that this label is in the native language of Argentina, Spanish

Fig. 5.

A label from Brazil of a soft drink. The label is in English because the product is made in Brazil and imported and distributed in the U.S. Guaraná Antarctica, The Brazilian Original Guaraná Soda, Amazon

In Argentina, any regulations must be published in the Official Bulletin to become active. This would remove “cereals containing gluten; i.e., wheat, rye, barley, oats, spelt, or their hybridized stains and products” from having to be listed, and it would be replaced with “wheat, rye, barley, oats, spelt, or their hybridized strains and products.” Consequently, manufacturers would not be required to write “gluten” in their allergens list explicitly [26].

Venezuela has also recently updated its laws. According to the Venezuelan Standard for the General Labeling of Prepackaged Foods (COVENIN 2952:2001-1st Revision), Venezuelan law requires food allergen labeling. However, this regulation prohibits manufacturers from using precautionary statements on their labels [25]. Other nations, including Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Chile, and Mexico, have begun to establish regulations. Most countries with food allergen labeling laws require that the allergens listed come from the Codex Alimentarius. These are as follows: cereals with gluten, crustacea, and crustacean products; egg and egg products; fish and fish products; peanuts, soybeans, and products of peanuts and soybeans; milk and milk products, including lactose; tree nuts and their products; and sulfites when the concentration consists of 10 mg/kg or more. The list may vary by country due to the prevalence of intolerances to other foods and the above-mentioned allergens. Unfortunately, an accurate reporting of food allergies in Latin America is still being determined due to the limited number of studies done in Latin America. As of 2018, eight countries in Latin America do not have established food allergen labeling laws, including Bolivia, Dominican Republic, Haiti, Honduras, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, and Uruguay [26].

MERCOSUR, officially known as the Southern Common Market, an economic and political bloc that includes Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay, strives to ensure that the laws in Latin America work in unison, including food allergen labeling regulations [26]. In 2011, there were discussions within MERCOSUR to implement mandatory labeling. However, due to some unresolved issues, the conversations never continued beyond 2015 [26]. MERCOSUR’s Technical Regulation on the Labeling of Packaged Foods states that packaged foods cannot be labeled in any manner that would make it unclear for the consumer to comprehend [27]. The legislation also requires that the ingredients are listed in the language of the respective nation, which would be either Spanish or Portuguese, the two primary languages in South America. It is also required that an ingredient list be included, but the legislation does not mention that food allergens be identified separately [27]. If the product has a compound ingredient that has been established by the Codex Alimentarius but comprises less than 25% of the product, the ingredients of the compound ingredient do not need to be declared. In June 2015, Brazil passed the Resolução da Directoria Colegiada (RDC) 26/2015, which required mandatory food allergen labeling. MERCOSUR also allows manufacturers to use precautionary statements. However, they must submit a “Declaración Jurada.” This requires manufacturers to add a statement declaring that even though “good manufacturing practices” were employed, there may be some cross-contamination [26].

Brazil has added latex as one of the allergens to be declared, but sulfites have yet to be added. The Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency (ANVISA) stated that sulfites cannot be considered allergenic and, therefore, cannot be listed as “allergenic.” However, companies may still emphasize in their ingredient list that sulfites may be present in their product as long as they adhere to the general rules of the ingredient list [22].

Europe

Food Labeling Laws in the UK

The United Kingdom (UK) also has its own laws regarding food allergen labeling. Manufacturers must list the name of the food; expiration date; warnings; net quantity information; ingredients if there are more than one; name and address of the manufacturer, packer, or seller; country of origin; lot number; any special storage conditions; and cooking instructions if applicable [28]. UK law requires that the country of origin be listed for beef, veal, lamb, mutton, pork, goat, poultry, fish, shellfish, honey, olive oil, wine, and fruit and vegetables imported from outside the European Union (EU) [29]. If a product has two or more ingredients, manufacturers are required to list all the ingredients. The ingredients must be listed by order, and the main ingredient is to be listed first. The percentage of an ingredient must be listed if it is emphasized by the packaging, mentioned in the name, or the name commonly known by the consumer. Allergens must be listed in a different font, style, or background color. UK law requires that manufacturers list the following: celery, cereals with gluten (including wheat, rye, barley, and oats), crustaceans (including prawns, crab, and lobster), eggs, fish, lupin, milk, mollusks (including squid, mussels, cockles, whelks, and snails), mustard, nuts, peanuts, sesame seeds, soya beans, and sulfur dioxide or sulfites that have more than 10 mg/kg or 10 L [28]. However, food made on-premise in the United Kingdom that has been wrapped was once optional to have allergen advice. In 2015, 15-year-old Natasha Ednan-Laperouse purchased a sandwich from Pret a Manger, a popular chain in Europe, at Heathrow International Airport in England. Because restaurants were not required to label food when prepared on the premises at the time, Ms. Ednan-Laperouse died of anaphylaxis secondary to an allergy to sesame. Since the incident, the British government declared that it would consider revising its labeling laws. In October 2021, Natasha’s law became effective in the UK, requiring retailers to display full ingredient and allergen labeling on every food item made on the premises and pre-packed for direct sale [30].

As of 2022, one restaurant in England prepared and marked food for consumers who reported food allergens. The food came with a flag denoting that the food was “made with care” with the hashtag “allergen aware” (Fig. 6). Although labeling prepared foods at restaurants is not required by law, the restaurant’s actions demonstrate a growing awareness of food preparation for consumers with food allergens.

Fig. 6.

A food allergen marker provided by a restaurant in England after a consumer reported a food allergy, provided by author FC

Because of Brexit, there were changes to some labeling laws. On October 12, 2020, the UK government updated its guidance on the food and drink labeling rules applicable from January 1, 2021. Previous guidance had indicated that foods sold in Great Britain (GB) required labeling changes from January 1, 2021, but according to the updated guidance, the requirements for particular labeling changes will instead apply to food placed on the GB market from October 1, 2022 [31]. Moreover, Northern Ireland will not follow the specific food labeling rules applicable in GB but will instead continue to follow the food labeling rules applicable in the EU [31].

Food Labeling Laws in the European Union

The European Union requires that allergens are emphasized in the ingredient list so consumers can easily identify them. As of March 2022, the 27 members of the European Union include Germany, France, Italy, Sweden, Poland, Spain, Ireland, Romania, Netherlands, Denmark, Bulgaria, Belgium, Croatia, Portugal, Austria, Greece, Czech Republic, Hungary, Finland, Luxembourg, Malta, Lithuania, Republic of Cyprus, Slovenia, Slovakia, Estonia, and Latvia. The EU allows manufacturers some flexibility in deciding how to emphasize the allergens. According to an EU notice relating to Annex II of Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011, if a substance consists of multiple words, the only word that must be emphasized is the allergen [32]. In instances where allergens are present in compound ingredients, the substances must be listed in the ingredient list. For example, the word”egg “ must be emphasized if a sandwich has mayonnaise that contains egg [32].

If a food has a product as an ingredient that does not require an ingredient list, the manufacturer must list the allergen and emphasize it on the product. For example, wine does not require an ingredient list per European Union regulations. However, if another food contains wine, the manufacturer must list it as an ingredient and should write, “ingredients […] wine (contains sulphites) […]” [32]. Furthermore, if a product has the same allergen multiple times, the manufacturer need not repeatedly list the allergen. Instead, it can be listed collectively as long as it is emphasized [32]. For example, the manufacturer can include a footnote at the end of each ingredient and put the allergen at the bottom of the list. When foods such as cream or cheese are an ingredient, the manufacturer is not required to list the allergen — in this instance, milk — because the allergen is already clearly identified. Even so, if a food is sold or marketed under a trademark or brand name and the name does not specifically refer to the allergen, the allergen must be identified with additional information. Furthermore, if a food has a clearly identifiable allergen on the front of the product, the allergen must still be emphasized in the ingredient list. In the European Union, if nuts are present in the product, the manufacturer must clarify which type of nut is present. For example, if the product has almonds, rather than writing “tree nut,” the manufacturer should write “almond.” This regulation applies in other countries as well. Finally, the European Union does not have any legislation that addresses “may contain” or “free from” claims to suggest that something is convenient for those with food allergies [33].

Although Switzerland is not a member of the European Union, in November of 2013, the Swiss government published changes to the Ordannance du DFI sure l’etiquetage et la publicité des denrées alimentary (817.022.21). This ordinance has similarities to Article 21 of the EU’s Labeling Directive. The EU’s Labeling Directive requires that allergens be easily identifiable through a special font, size, or background color [25]. Switzerland follows the same list of allergens that the European Union declares [34]. Macedonia, Iceland, Norway, and Liechtenstein, all members of the European Economic Area (EEA), follow the same rules that have been established under EU regulations [25].

On April 1, 2020, a new regulation on the indication of primary ingredients of different origins was implemented throughout the EU. It requires manufacturers to indicate the origin of primary ingredients if they differ from the product’s origin. The origin of the primary ingredients must now be indicated in case it does not correspond to the indicated country of origin or place of provenance of the food [35].

Food Labeling Laws in Ukraine

Little information is known about the prevalence of food allergies in Ukraine. In a 2022 cross-sectional study on food hypersensitivity in children aged 0–3 years of the Lviv region, the most common allergens were milk, egg, and wheat [36]. Ukraine enacted a law in August 2019 regarding food products labeling, including imported foods. The law was created to define what information must be communicated to consumers and provide more standardized regulations for food labeling [37]. Even more recent labeling requirements for country of origin or place of origin for selected food products were adopted on April 1, 2021 [38]. Under these new requirements, food products’ country/countries of origin or place of origin must be documented throughout the entire production and sales cycle so that this information may appear on the product label [38]. The requirements, which address beef, pork and poultry products, honey, and olive oil labeling, satisfy Ukraine’s part under its Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area Agreement with the European Union [38]. The requirements will come into force on May 18, 2024.

Food Labeling Laws in Scandinavian Countries

Nordic countries, which include Denmark (Fig. 7), Iceland, Finland, Norway, Sweden, Greenland, the Faroe Islands, and the Åland Islands, require the word “ingredients” to appear before the ingredient list. Ingredients must be listed in the order of descending weight [39].There are many similarities between Nordic countries’ requirements regarding the allergens that must be declared. These allergens include the following: cereals with gluten (wheat, rye, barley, oats, spelt, kamut or their hybridized strains) and their products, crustaceans and their products, eggs and their products, fish and their products, peanuts and their products, soybeans and their products, milk and their products (including lactose), nuts (almonds, hazelnuts, walnuts, cashews, pecan nuts, Brazil nuts, pistachio nuts, macadamia nuts, and their products), celery and their products, mustard and their products, sesame seeds and their products, sulfur dioxide and sulfites with concentrations of more than 10 mg/kg or 10 mg/L, lupin and their products, and mollusks and their products. Nordic law also requires that allergens be distinguished in a different typeset or format, and allergens must be declared if they are an ingredient, compound ingredient, category of food, additive, or processing aid [39]. Statements such as “may contain traces of…” are also voluntary as they are not being monitored by any government organization. However, they cannot be written in a manner that would mislead or confuse the consumer [39]. Precautionary statements should only be used if the risk of cross-contamination is “uncontrollable […] or sporadically occurring” [39].

Fig. 7.

A label for Nordic Sweets Salmiac Licorice Salty Stix from Amazon, showing an allergen listed in a different format as required by law. The food is a product of Denmark. The label is in English

Asia

Food Labeling Laws in East Asia

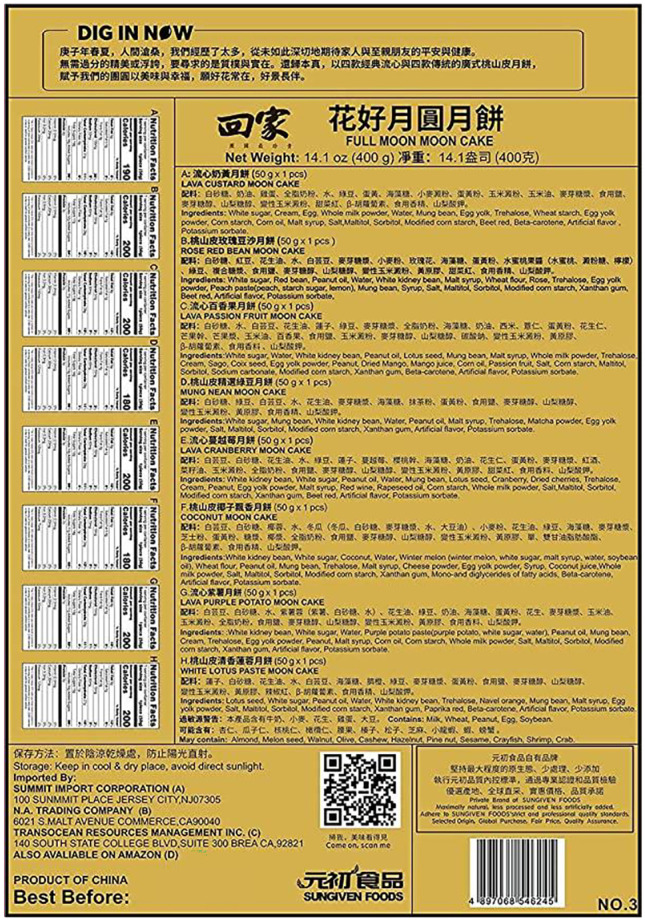

China’s State Administration of Market Regulation (SAMR) and National Health Commission proposed changes to food labeling regulations at the end of 2019 that are expected to impact labeling regulations for locally produced and imported foods significantly [40]. In China, labeling errors have been the leading cause of non-compliance complaints from consumers seeking monetary compensation [41]. The changes aim to protect consumers from misleading or inaccurate food labeling [40]. One document under revision is the General Standard for the Labelling of Prepackaged Foods (GB7718-2011), a mandatory national food safety standard that specifies the labeling requirements of prepackaged foods in China [41]. The standard was issued on April 20, 2011, and implemented on April 20, 2012. China released a draft revision of GB7718-2011 on December 31, 2019. The main changes include modifying the declaration requirements for foods that contain allergens. Appendix E of the draft revision provides the methods for declaring allergens in food labels and lists the ingredient categories that require an allergen warning. For example, allergen declaration methods include but are not limited to using bold font and underlining [42]. Allergens that need warning include grains and grain products containing gluten substances, crustacean animals and products, fish and its products, eggs and its products, peanut and its products, soybean and its products, milk and dairy products (including lactose), and nut and its products [42]. Appendix E also requires warnings be provided “in close proximity to the list of ingredients; marking words such as ‘warning of food allergens’, ‘warning of allergens’ or ‘information of allergens’ may be used at the same time” (Fig. 8) [42]. Example warnings include “containing egg, peanut, nut, and milk” and “this product contains fish and soybean components” [42]. Heavily processed ingredients exempt from declaring allergens include refined vegetable oil, phospholipid, starch, and dextrin [42]. An example of an ingredient label with the marking words “may contain” is illustrated in Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

A label for ONETANG Assorted Lava Moon Cake from Amazon, showing the ingredients list followed by an allergen listing in close proximity. The label is in Chinese and in English

The proposed changes to food labeling include the draft “Measures on Supervision and Management of Food Labeling” released by SAMR for domestic comment on November 20, 2019. The document specifies labeling for food produced and distributed within China and contains information on the supervision and management of food labeling [42]. The basic requirements on food labeling call for labels that are “clear, obvious, persistent and easy to distinguish and identify” [42]. Bigger font sizes or special characters and colors should be used for the food name, production date, shelf life, and warning signs to differentiate it from other information on the label [42]. The Measures also regulate the languages used in labeling. According to Article 11, normative Chinese characters should be used for food labeling, which can be used in conjunction with the Chinese phonetic alphabet or foreign languages. However, the size of languages should not be bigger than the corresponding Chinese characters [42]. The Measures list requirements for food labeling, including for food made from plants, health foods, and repackaged foods, but none of the articles specifically address how allergens are marked.

Prepackaged food sold in Hong Kong must follow the requirements under the Food and Drugs (Composition and Labelling) Regulations, which provide information on the marking and labeling of prepackaged food and the nutrition labeling of prepackaged food for infants and young children. The regulations were released on November 11, 1960. Schedule 3 under the regulation requires that prepackaged foods must be legibly marked or labeled with their food name or destination; list of ingredients; appropriate durability indication; statement of special conditions for storage or instructions for use; count of contents, net weight, or net volume of the food; name and address of manufacturer or packer; and appropriate language [43]. The list of ingredients must specify the name of any of the following substances: cereals containing gluten (namely wheat, rye, barley, oats, spelt, their hybridized strains and their products); crustacea and crustacean products; eggs and egg products; fish and fish products; peanuts, soybeans and their products; milk and milk products (including lactose); tree nuts and nut products [43]. The list of ingredients for foods that consist of or contain sulfite in a concentration of ten parts per million or more must include the functional class of the sulfite and its name. The requirements of Schedule 3 need only be met in either English or Chinese [43]. However, if both English and Chinese appear in the labeling or marking of prepackaged foods, the name of the food and the list of ingredients shall appear in both languages [43]. Schedule 4 lists the items exempt from Schedule 3, which include drinks with an alcoholic strength by volume of more than 1.2% but less than 10%, prepackaged food sold at a catering establishment for immediate consumption, and individually wrapped confectionary products in a fancy form intended for sale as single items [43]. Verified copies of Food and Drugs (Composition and Labelling) Regulations are available for download at https://www.elegislation.gov.hk/hk/cap132W?pmc=0&SEARCH_WITHIN_CAP_TXT=language&xpid=ID_1438402697252_001&m=0&pm=1 in English and traditional Chinese.

Taiwan recently revised its food allergen labeling regulations. Previously, Taiwanese law required that manufacturers label the package with “This product contains,” “This product contains [name of substance], unsuitable for susceptible individuals,” or a variation of these words. On August 21, 2018, legislation added a new way to declare any necessary warnings. Once the name of allergic substances is claimed in the product name, all the allergic substances of the product shall be included in the product name [44]. Moreover, this new legislation raised the number of allergens that must be declared from six to eleven. Taiwanese law now requires the following to be declared: “Crustacea and products thereof; Mango and products thereof; Peanut and products thereof; Milk, goat milk and products thereof, except lactitol derived from milk and goat milk; Eggs and products thereof; Nuts and products thereof; Sesame and products thereof; Cereals containing gluten and products thereof, except glucose syrup, maltodextrin and alcohol produced from cereals; Soybean and products thereof, except highly refined or purified soybean oil (fat), tocopherols and their derivatives/analogs, phytosterols and phytosterol esters; Fish and products thereof, except fish gelatin used as carrier for vitamin or carotenoid preparations; fish gelatin used as a thickening agent in alcohol; The use of sulfites etc., at concentrations of 10 mg/kg or more in term of total sulfur dioxide which are to be calculated for final products.”

Japan was the first country to decree mandatory allergen labeling. Japan’s Food Sanitation Act (Act No. 233 of 1947), which was last revised in 2018, requires that manufacturers clearly declare the labeling on the container. Manufacturers must also ensure that they are indicating any possibility of present allergens. Japanese law separates its allergen labeling into mandatory and recommended. There are twenty-seven total substances that are a part of the list. Of the twenty-seven, only seven are considered compulsory, while the other twenty are a part of the recommended list.

South Korean law also requires manufacturers to acknowledge food allergens in their products even if the product may have a slight amount of the allergen (Fig. 9) [25]. Beginning on May 30, 2017, the Korean Ministry for Food and Drug Safety implemented a food allergen labeling system. The system requires eggs, milk, buckwheat, peanuts, soybeans, wheat, mackerel, crab, shrimp, pork, peaches, tomatoes, sulfites, walnuts, chicken, beef, squid, and shellfish to be labeled. An example of a food label with an allergy notice is illustrated in Fig. 9. South Korea’s law requires that foods sold as raw materials be labeled around the product names or price. Another method to declare allergens is through a common poster or brochure. Food sold online should be labeled on the website, while food ordered on the telephone should be labeled as a pamphlet or brochure [45].

Fig. 9.

A label for Yopokki Sweet & Mild Spicy Tteokbokki Pack from Amazon, showing the ingredients list followed by an allergy notice. The label is in English because the brand, according to a statement posted on Amazon, markets to American consumers

Food Labeling Laws in South Asia

A 2017 study indicates that there is an overall low incidence of allergy in South Asia and a variety of allergens reported [46]. Unfortunately, food allergen labeling laws are not well-developed in some areas of South Asia, including Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Nepal, Maldives, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka. These eight countries form the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), an economic and political organization. Afghanistan has yet to establish its own food laws, while Bangladesh, Bhutan, Nepal, and Sri Lanka do not have any food allergen labeling laws despite having food laws [25]. Pakistan has enforced food allergen labeling laws, which follow the regulations established under Codex Alimentarius.

On June 17, 2022, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) and Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) called for the draft Food Safety and Standards (Labeling and Display) Amendment Regulations (2022) to be implemented [47]. The amendments, which include some recommendations from the Codex, include categories related to minimally processed foods, tolerance limits, and a warning statement related to pan masala [48]. They also address the labeling of non-retail containers. The food labeling regulation became effective on July 1, 2022. Food products and ingredients containing allergens (cereals, crustacean, and their products; milk; eggs; nuts; fish; etc.) must carry a declaration regarding the presence of the allergen in the food product [49]. Previously, India only required food allergens in infant milk substitutes to be listed as allergens.

Food Labeling Laws in Southeast Asia

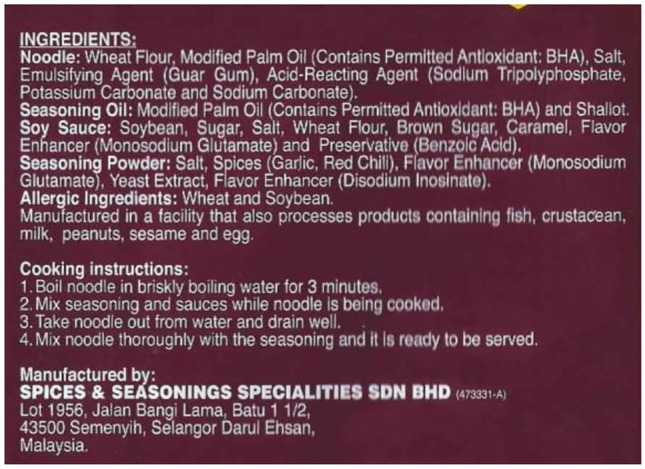

Ten additional South Asian countries (Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam) have formed their own organization, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). ASEAN instituted the Guiding Principles for Food Control Systems in 2005. The Guiding Principles for Food Control Systems includes the same allergens outlined in Codex Alimentarius. The ASEAN General Standards for the Labelling of Prepacked Food in June 2016 Sect. 4 states: "The following foods and ingredients are known to cause hypersensitivity and shall always be declared: Cereals containing gluten; i.e., wheat, rye, barley, oats, spelt or their hybridized strains and products of these; Crustacea and products of these; Eggs and egg products; Fish and fish products; Peanuts, soybeans and products of these; Milk and milk products (lactose included); Tree nuts and nut products; and Sulphite in concentrations of 10 mg/kg or more” [50]. Malaysia (Fig. 10) and Vietnam both require by law that foods known to cause reactions in individuals are declared as ingredient lists. Brunei, Laos, and Cambodia do not have their own laws [25]. The Philippines (Fig. 11) has food laws but no specific food allergen labeling laws. However, U.S. labeling laws are commonly followed by manufacturers in the Philippines [25]. Examples of a food label from Malaysia and the Philippines are illustrated in Figs. 10 and 11, respectively.

Fig. 10.

A label for Ibumie Always Mi Goreng Asli from The Ramen Rater. The ingredient list is broken down by the ingredients in the noodle, seasoning oil, and seasoning powder. In addition to declaring the allergic ingredients, the label states that the food product was manufactured in a facility that also processes products containing fish, crustacean, milk, peanuts, sesame, and egg. The label is in English because it is imported to and distributed in the United States

Fig. 11.

A label for Excellent Noodle-Wheat Pancit Canton from Walmart. The packaging lists the ingredients underneath the brand name and states that the product contains wheat ingredients. The label is in English because the food product is manufactured in the Philippines and imported to the United States

Food Labeling Laws in Western Asia

Turkish law requires that food labeling and nutrition information include the food name, the ingredient list, allergens, net amount of food, expiration or sell-by-date, instructions of use, name or business name and address, country of origin, alcohol strength for beverages with more than 1.2% volumetric alcohol, a nutrition notice, and a user manual [51]. These regulations were included in the Turkish Food Codex Labelling and Informing Consumers Regulation and the Turkish Food Codex Nourishment and Health Declaration Regulation published on January 26, 2017. In addition, Turkey’s laws also require mandatory allergen labeling [51]. On January 22, 2019, the World Trade Organization announced that the Turkish Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry/General Directorate proposed to adopt the Turkish Food Codex Regulation on Food Labelling and Information to Consumers [52]. The document follows the Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 of the European Parliament and the Council, with the goal of protecting customers by “[setting out] general principles, needs and responsibilities governing food information to consumers and in particular food labelling” [52]. The publication entered effect into on December 31, 2019.

Eastern Europe and Asia

Food Labeling Laws in the Commonwealth of Independent States

The Commonwealth of Independent States, which consists of Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Russian Federation, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan, recognizes major allergens [25]. However, manufacturers are not required to label allergens.Ukraine currently does not have any laws relating to food allergen labeling. However, The Draft of Technical Regulation states that the Ukrainian government will adhere to the European Parliament’s and the European Council’s regulations [25]. Ukraine follows the same list of allergens as the European Union [34].

Food Labeling Laws in Russia

An online survey conducted in Russia in 2020 estimates that over 35 million Russian adults have allergies [53]. The Technical Regulations of the Russia-Kazakhstan-Belarus Customs Union (CU) on Food Product Labeling established food products labeling requirements that came into force on July 1, 2013 [54]. The requirements include information regarding the naming of food products, methods of clear and readable labeling, specification of nutrition value in food products labeling, and specification of the name and location of food products. An unofficial English translation of the Customs Union Technical Regulations on Food Product Labeling can be found in a report by the USDA Foreign Agricultural Service.

Africa

South Africa requires that the following be declared on the packaging of an allergen: ingredient list, name of the food, batch identification number, instructions for use, name and address of the manufacturer, special storage instructions if applicable, net contents, country of origin, date marking, the Quantitative Ingredients Declaration, and the allergens. South Africa recognizes the following as common allergens: cow’s milk, egg, crustacean products, mollusks, fish, peanuts, soybeans, tree nuts, and cereals. Allergens must be indicated in parenthesis after an ingredient in the ingredient list or must be identifiable at the end with a “contains” statement [55]. South African law does not permit any “gluten free” claims on products except if the gluten level of the final product does not exceed 20 mg/kg of gluten [33].

Morocco recognizes fourteen substances that are known to cause allergic reactions or intolerances. These include cereals, crustaceans, and their products; eggs and their products; fish and fish products; peanuts and peanut products, soybean and soy products; milk and milk products including lactose, nuts, celery, and celery products; mustard and mustard products; sesame seeds and sesame seed products; sulfur dioxide and sulfites; lupine and lupine products; and mollusks and products derived from mollusks [56]. Many exceptions accompany Moroccan law. “Cereals” includes wheat, rye, barley, oat, spelt, and kamut, or their “hybridized stains and products” made from the above cereals. However, wheat glucose syrups with dextrose, wheat-based maltodextrins, glucose syrups made of barley, and cereals that are used for “alcoholic distillates, including ethyl alcohol of agricultural origin” are exempted [56]. Additionally, “fish and fish products” excludes “fish gelatin used as a carrier for vitamin or carotenoid preparations” and “fish gelatin or isinglass used as a clarifying agent in beer and wine” [56]. “Soybean” excludes oil and grease of highly refined soybean, “mixed tocopherols natural (E306), d-alpha-tocopherol Natural, the acetate of d-alpha-tocopheryl natural derivatives of soybean,” “phytosterols and phytosterol esters derived from vegetable soybean oils,” and “plant stanol ester produced from sterols derived from vegetable soybeans oils” [56]. Milk excludes lactitol and milk products when used to create “alcohol distillates including ethyl alcohol of agricultural origin” [56]. Moroccan law recognizes the following nuts: almonds, hazelnuts, walnuts, cashews, pecans, Brazil nuts, pistachio nuts, and Macadamia nuts or Queensland nuts. Nuts used to create “alcohol distillates including ethyl alcohol of agricultural origin” are also excluded [56]. Sulfur dioxides and sulfites only have to be declared when they are of concentrations of more than 10 mg/kg or 10 mg/L “in terms of total SO2 for the products offered ready for consumption or reconstituted according to the manufacturer’s instructions” [56].

One study published in 2018 on one sub-Saharan African country, Malawi, has revealed that Malawi’s food allergen labeling regulation is less demanding compared to the U.S., EU, and South Africa’s Regulation Relating to the Labeling and Advertising of Foods regulations, and is not protective enough [57].

Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Burundi, and Rwanda are the five member states that comprise the East African Community (EAC). EAC regulations regarding the labeling of prepackaged food have entered into force and are as follows:

EAS 38:2014 Labelling of pre-packaged foods — General requirements

EAS 803: 2014 Nutrition labelling — Requirements

EAS 804:2014 Claims — General requirements

EAS 805:2014 Use of nutrition and health claims —Requirements

Labeling of food products requires the name of food, net contents, country of origin, date marking and storage instructions, list of ingredients and allergens, name and address (manufacturer, packer, distributor, importer, exporter or vendor), lot identification, instructions for use, and QUID (quantitative ingredients declaration). The EAC does not require the inclusion of nutritional information on packaging labels, but there is a guiding template that can be found at the following website: https://resources.selerant.com/food-regulatory-news/east-african-community-labeling-reference-guide-now-available-on-scc. The language of the nutritional information must be in English and/or any other official language used in the importing East African partner State [58].

Oceania

Food Labeling Laws in the Oceania Region

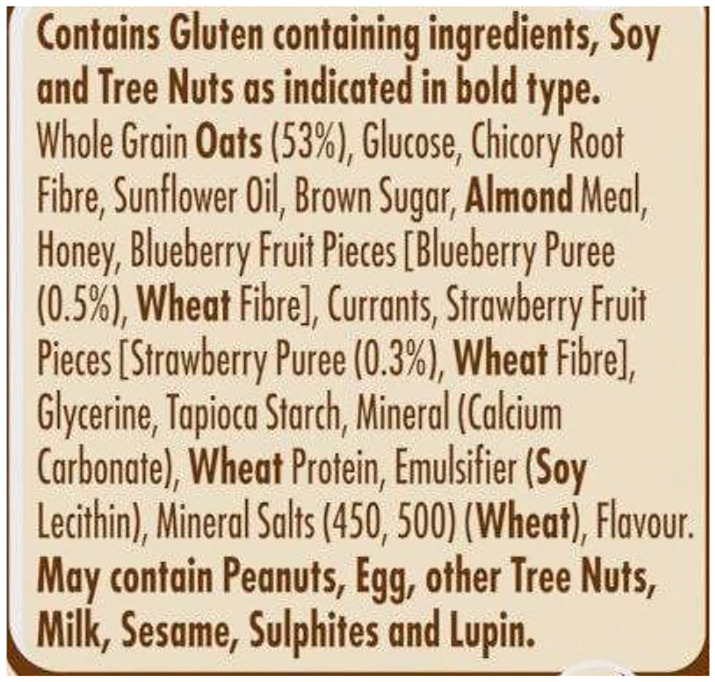

Australia has one of the highest food allergy prevalence in the world at about 11% [59]. Allergy and Anaphylaxis Australia is a non-profit organization that strives to educate Australians on the prevalence of food allergies. According to Allergy and Anaphylaxis Australia, 1 to 2% of adults are believed to have food allergies in Australia. Four to eight percent of children under 5 years are also thought to have food allergies [60]. The Australian Food and Grocery Council regulates labeled laws throughout the nation. Packaging is required to have a list of ingredients, declare any major allergens, and state the percentage of the key ingredients in the product. The Allergen Bureau was established by the Australian Food and Grocery Council in 2005. Their objective is to help the industry with allergen identification and labeling issues [61]. In 2007, the Australian Food and Grocery Council Allergen Forum released a food allergen labeling guide to assist companies known as the “Food Industry Guide to Allergen Management and Labelling.” By law, the ingredients must be listed on most packaged foods.

The Australian government requires that the following ingredients be labeled: cereals with gluten, crustacea, egg, egg products, fish, fish products, milk, milk products, peanuts and soybeans and their products, sulfites containing concentrations of 10 mg/kg or more, and tree nuts and sesame and sesame their products. These ingredients must be listed when they are present in the product as “an ingredient; or an ingredient of a compound ingredient; or a food additive or a component of a food additive; or a processing aid or a component of a processing aid” [61]. The guide also states that coconut is not considered a nut and therefore does not have to be listed under tree nuts. Additionally, the guide encourages businesses to separate non-allergen foods from allergenic foods and business owners to train their staff on food allergy awareness. Although Australian law does not specify a format to list food allergens, the Food Industry Guide to Allergen Management and Labelling suggests ways for businesses list the allergens. They suggest that all allergens be listed together to make them more apparent to the consumer rather than hidden in the ingredient list. A description of the product is also recommended; this description should not be misleading but should instead be used to provide an expectation of the product.

Allergens should be listed in plain, simple English. The guide also suggests that the print size be big enough so that it is legible. At a minimum, the print size should be 1.5 mm, and the font should be Sans Serif. The font color should not blend in with the background or else it would be illegible. Furthermore, it is recommended that manufacturers employ an ingredient list, an allergen summary statement, and a precautionary statement. It is suggested that the allergens be identified in bold (Fig. 12). If tree nuts are present in the product, the manufacturer should specify which type of tree nut is present [61]. On February 25, 2021, Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) announced new changes to the Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code. The new requirements will help ensure that mandatory food allergen declarations are clear and consistent for consumers. These requirements include declaring allergen information in a specific format and location on food labels and using simple, plain English terms for allergen declarations.

Fig. 12.

A label for Nestlé from Nestlé Australia, following the allergen labelling requirements of the Australia New Zealand Foods Standards Code. Allergens are bolded

Papua New Guinea has considered adding its own laws regarding food allergen labeling but has yet to do so. In Mongolia, packaged food labeling standards, which follow the Codex Alimentarius, went into effect on January 1, 2018.

Discussion

Food allergies impact millions of people around the globe and can have profound physical, psychological, and social consequences. The primary findings of a 2016 study published in Annals of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology suggest that a significant proportion of children with food allergies may be at risk for posttraumatic stress symptoms, with those experiencing anaphylaxis at higher risk [62]. As of 2022, there have been several studies on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the quality of life for children and adolescents with food allergies. While survey data indicates significant increases in anxiety-like symptoms in the general public [63], depression and reported post-traumatic stress disorder particularly impacted individuals with allergic diseases [64]. The pandemic has also affected the families of children with food allergies. One study found that 44% of mothers of children with food allergy were found to have high rates of clinical anxiety during the pandemic [65].

Food allergies can also affect the activities of families with food-allergic children. One study found that of the 87 families evaluated, more than 60% of caregivers reported that food allergy significantly affected meal preparation. Forty-nine percent or more expressed that food allergy affected family social activities [66]. Parents of children with food allergies may also find themselves being more aware and vigilant of their surroundings because they need to be prepared for any potential allergic reactions.

The social consequences of having food allergies extend to school environments. In a study that surveyed 251 families, 32% of children reported being bullied at least once due to their food allergy. A follow-up study found that quality of life was reduced for those who were bullied [67]. There have also been cases of specific allergy-related bullying, such as food being intentionally contaminated with an allergen [67]. Efforts to create safe school environments for students with food allergies, such as the implementation of allergen-free tables, have had their own impacts on students. Some parents and students have stated that these policies only increased feelings of isolation. Recent guidelines recommend schools do away with allergen-free zones and instead provide teachers and staff with food allergy training and allergy action plans [68]. The psychology of traveling with food allergies is a significant issue that is beyond the scope of this paper.

More standardized and strict labeling laws are necessary for citizens’ and tourists’ health and well-being (Table 2). While many countries follow the Codex Alimentarius, the regulatory process of identifying allergens and designing labels differs depending on the government and organization [69]. As of February 2023, FDA’s Compliance Programs provide instructions for evaluating industry compliance, including cosmetics, dietary supplements, and food and beverages [70]. There is no compliance program for allergen regulation. Implementing food compliance and monitoring programs can help enforce food allergen labeling laws but may not be practical solutions. People with food allergies should familiarize themselves with their own country’s laws and those of any countries they visit. There are differences in the major allergens recognized by countries and their inclusion in allergen labeling. For example, while mollusks are recognized as a common food allergen in Canada, Morocco, and South Africa, and UK law requires mollusks to be listed if present, the U.S. does not identify them as a major allergen source. Variation in allergen recognition and labeling laws may have been developed in response to prevalence. Seafood allergies, such as crustacean shellfish allergies, are among the most common food allergens worldwide [71]. Molluscan shellfish allergies are well-known, but their lower rates of occurrence may explain their lack of recognition as a major allergen.

Table 2.

Reasons for food labeling laws

| • Inform the purchaser of the presence of potential food allergens so that they may take steps to mitigate exposure |

| • Create more accessible and comprehensible labels for consumers |

| • Prevention of severe anaphylaxis leading to death |

| • Standardization of domestic and international food labels |

| • Greater awareness of food allergies in general |

From a global standpoint, the ease of navigating food allergen labeling laws is dependent on the language spoken, consistency of labeling (implementation of laws), adherence to policies, and accessibility of the policies. On January 6, 2010, following a complaint made by two passengers who claimed to have difficulties with nut allergies when traveling with Air Canada, the Canadian Transportation Agency ruled to require carriers to establish allergy buffer zones if requested [72]. The policy, last updated on December 3, 2020, allows passengers to request to be seated in a bank of seats where the allergen is not located and ask to pre-board and clean the seat [73].

With planning and preparation, people with food allergies can travel anywhere. It is also important to be aware of non-food products that contain allergens, such as playdough (may contain wheat), sunscreens (may contain tree nut oils and extracts), and cosmetics (may contain soy or tree nuts). Although there are many public resources available for individuals living with food allergies and for families with food allergic children, it is important to check that the information is from a credible source.

FARE, the U.S.-based non-profit organization, provides a step-by-step guide of recommendations for traveling with food allergies. The guide includes advice about preparing for a trip months, weeks, and days before travel and what to do while abroad. FARE also includes personal accounts of traveling with food allergies on its website, which is organized by country. The guide and accounts are available to the public on the FARE website: https://www.foodallergy.org/resources/traveling-abroad [74].

Moreover, Allergy UK, a British medical charity, offers patients the option to purchase translation cards. The cards include an allergy alert message, an emergency message, and a message for use in restaurants when ordering food. The organization allows patients to buy cards for up to 70 allergens in 35 languages. These languages include Balinese, Bulgarian, Cambodian (Khmer), Chinese (Simplified), Croatian, Czech, Danish, Dutch, Finnish, Flemish, French, German, Greek, Hindi, Hungarian, Icelandic, Italian, Indonesian, Japanese, Lao, Malay, Maltese, Norwegian, Polish, Portuguese, Punjabi, Russian, Slovene, Spanish, Swahili, Swedish, Tamil, Thai, Turkish, and Vietnamese. Three cards per language comprise one set, and the cards are about the size of a credit card [75].

The safety of people with food allergies should not fall solely on those individuals. Food allergies are a public health concern, with the cases of documented food allergies increasing over the past few decades. In addition to stricter labeling laws and guidelines, there is a need to raise awareness about food allergies and advocate for legislative change. The lack of universal labeling laws and the variability in the language in which allergen information is displayed can be quite confusing to travelers around the world. Those with food allergies who travel must be aware of the limitations of food labels and protect themselves in places where food is not labeled, such as restaurants and bars, airplanes, ships, and private gatherings. People with food allergies may look into purchasing or making allergy translation cards using credible sources. Being able to read a food label also does not eliminate the need to carry emergency medications such as epinephrine in case of accidental ingestion. Epinephrine is the only medication able to reverse an anaphylactic reaction. An additional point that was not addressed in this paper is that despite the presence of food allergen labeling laws and policies in almost every nation in the world, enforcement of such polices may vary depending on the social conditions of the respective countries.

Author Contributions

F.C and L. E. wrote the main manuscript and obtained figures. C.C. conceptualized the project and finalized the review of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Francesca Chang and Lauren Eng contributed equally to this project

Contributor Information

Francesca Chang, Email: 19fchang@gmail.com.

Lauren Eng, Email: laureneng830@gmail.com.

Christopher Chang, Email: chrchang@mhs.net.

References

- 1.Hadley C. Food allergies on the rise? Determining the prevalence of food allergies, and how quickly it is increasing, is the first step in tackling the problem. EMBO Rep. 2006;7(11):1080–3. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Food anaphylaxis in the United Kingdom: analysis of national data, 1998–2018. BMJ 2021;372:n733. 10.1136/bmj.n733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Jackson KD, Howie LD, Akinbami LJ (2013) Trends in Allergic Conditions Among Children: United States, 1997–2011. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db121.pdf [PubMed]

- 4.AllerGen. Estimated Food Allergy Prevalence among Canadian children and adults. 2017:Prepared June 2017 with 2016 Statistics Canada Census data. Perceived food allergy self-reported through a nationwide AllerGen research survey. https://allergen.ca/wp-content/uploads/Canadian-food-allergy-prevalence-Jul-2017.pdf

- 5.Marchisotto MJ, Harada L, Kamdar O et al (2017) Food allergen labeling and purchasing habits in the United States and Canada. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 5(2):345–351.e2. (In eng). 10.1016/j.jaip.2016.09.020 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Kasapila W, Shaarani SM. Legislation—impact and trends in nutrition labeling: a global overview. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2016;56(1):56–64. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2012.710277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.He Y, Huang L, Yan S, et al. Awareness, understanding and use of sodium information labelled on pre-packaged food in Beijing: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):509. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5396-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.General standard for the labelling of prepackaged foods (1985) In: Organization FaAOotUNWH, ed. 9

- 9.Gupta RS, Warren CM, Smith BM, et al. Prevalence and severity of food allergies among US adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(1):e185630–e185630. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.5630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Administration FaD (2022) Questions and Answers Regarding Food Allergens, Including the Food Allergen Labeling Requirements of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (Edition 5): Guidance for Industry. In: Services USDoHaH, ed. https://www.fda.gov/media/117410/download

- 11.Administration FaD (2022) Questions and answers regarding food allergens, including the Food Allergen Labeling Requirements of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (Edition 5): guidance for industry. In: Services USDoHaH, ed

- 12.Administration USFD. Food allergies. https://www.fda.gov/food/food-labeling-nutrition/food-allergies. Accessed 10 Jan 2023

- 13.Administration FaD (2013) Guidance for industry: food labeling guide

- 14.Country of Origin Labeling (COOL) Frequently asked questions. USDA Agricultural Marketing Service. https://www.ams.usda.gov/rules-regulations/cool/questions-answers-consumers#:~:text=The%202002%20and%202008%20Farm,and%20shellfish%2C%20perishable%20agricultural%20commodities%2C. Accessed 25 Sept 2022

- 15.National Academies of Sciences E, Medicine, Health, et al (2016) In: Oria MP, Stallings VA, eds. Finding a path to safety in food allergy: assessment of the global burden, causes, prevention, management, and public policy. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US) Copyright 2017 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved [PubMed]

- 16.Jarrett V. President Obama signs new EpiPen law to protect children with asthma and severe allergies, and help their families to breathe easier. The White House: President Barack Obama. November 13, 2013. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/blog/2013/11/13/president-obama-signs-new-epipen-law-protect-children-asthma-and-severe-allergies-an

- 17.Canada FA. Food allergy FAQs. https://foodallergycanada.ca/food-allergy-basics/food-allergies-101/food-allergy-faqs/#:~:text=More%20than%203%20million%20Canadians,are%20impacted%20by%20food%20allergy. Accessed 25 Sept 2022

- 18.Common food allergens. Government of Canada. May 14, 2018. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-nutrition/food-safety/food-allergies-intolerances/food-allergies.html

- 19.Reading food labels. Food Allergy Canada. https://foodallergycanada.ca/living-with-allergies/day-to-day-management/reading-food-labels/. Accessed 4 June 2022

- 20.Sabrina’s Law. Food Allergy Canada. https://foodallergycanada.ca/sabrinas-law/. Accessed 4 June 2022

- 21.Food labelling for industry. Government of Canada. December 23, 2021. https://inspection.canada.ca/food-labels/labelling/industry/eng/1383607266489/1383607344939

- 22.Labelling, standards of identity and grades. Government of Canada. May 24, 2022. https://inspection.canada.ca/food-labels/labelling/eng/1299879892810/1299879939872

- 23.Food Allergen Labelling. Government of Canada. April 13, 2022. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-nutrition/food-labelling/allergen-labelling.html

- 24.Sánchez J, Sánchez A. Epidemiology of food allergy in Latin America. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 2015;43(2):185–95. doi: 10.1016/j.aller.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Diao X (2017) An Update on Food Allergen Management and Global Labeling Regulations. University of Minnesota 108

- 26.Lopez MC. Food allergen labeling: a Latin American approach. J AOAC Int. 2019;101(1):14–16. doi: 10.5740/jaoacint.17-0382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ng Clark M, Nielsen CR (2019) Update: food packaging regulations in Latin America. https://www.packaginglaw.com/special-focus/update-food-packaging-regulations-latin-america

- 28.Food labelling and packaging. GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/food-labelling-and-packaging. Accessed 4 June 2022

- 29.Food labelling and packaging: food labelling — what you must show. GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/food-labelling-and-packaging/food-labelling-what-you-must-show. Accessed 4 June 2022

- 30.Kirby D (2021) Natasha’s Law: teen’s parents’ pride as food allergy information must be displayed from today under new rules. i news. https://inews.co.uk/news/natasha-law-food-allergies-pret-labelling-ingredients-1226278

- 31.McKenzie B (2020) Europe: Brexit — impact on food labelling. Lexology. https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=770754ac-17d9-4462-bc5f-9e6720d281e5

- 32.Commission Notice of 13 July 2017 relating to the provision of information on substances or products causing allergies or intolerances as listed in Annex II to Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council on the provision of food information to consumers. Official Journal of the European Union; 2017:5

- 33.Steinman H (2014) Food allergens: concepts, control, management and risk assessment in Southern Africa. https://ilsi.org/southafrica/wp-content/uploads/sites/17/2016/05/ILSI-2014-Steinman-Concepts.pdf

- 34.Baker R. The global status of food allergen labeling laws. California Western Law Review 2018;54(2). https://scholarlycommons.law.cwsl.edu/cwlr/vol54/iss2/4/

- 35.Gwenner N. New EU food labelling rules for primary ingredients from April 2020. Weber Marking Blog. https://www.weber-marking.com/blog/new-eu-food-labelling-rules-for-primary-ingredients-from-april-2020/#:~:text=Starting%201%20April%202020%2C%20a,the%20origin%20of%20the%20product

- 36.Matsyura O, Besh L, Borysiuk O, et al. Food hypersensitivity in children aged 0–3 years of the Lviv region in Ukraine: a cross-sectional study. Front Pediatr. 2021;9:800331. doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.800331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ukraine: Ukraine adopts new labeling rules for selected food products. UP2020–0003. 2020. https://apps.fas.usda.gov/newgainapi/api/Report/DownloadReportByFileName?fileName=Ukraine%20Adopts%20New%20Labeling%20Requirements_Kyiv_Ukraine_01-28-2020

- 38.Tarassevych O. Ukraine: Ukraine adopts new labeling rules for selected food products. USDA Foreign Agricultural Service; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lindeberg YSBI. Undeclared allergens in food: food control, analyses and risk assessment. Copenhagen: Nordisk Ministerråd; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lim GY (2020) Packaged foods in China: compulsory allergen labelling and negative claim crackdown proposed. FoodNavigator-Asia. https://www.foodnavigator-asia.com/Article/2020/01/27/Packaged-foods-in-China-Compulsory-allergen-labelling-and-negative-claim-crackdown-proposed#

- 41.Staff FB. China releases draft general standard for the labelling of prepackaged foods for domestic comments. CH2020–0022. 2020. https://apps.fas.usda.gov/newgainapi/api/Report/DownloadReportByFileName?fileName=China%20Releases%20Draft%20General%20Standard%20for%20the%20Labelling%20of%20Prepackaged%20Foods%20for%20Domestic%20Comments%20_Beijing_China%20-%20Peoples%20Republic%20of_03-01-2020

- 42.Staff FB. Draft measures on supervision and management of food labeling. CH2019–0188. 2019. https://apps.fas.usda.gov/newgainapi/api/Report/DownloadReportByFileName?fileName=Draft%20Measures%20on%20Supervision%20and%20Management%20of%20Food%20Labeling_Beijing_China%20-%20Peoples%20Republic%20of_12-18-2019

- 43.Food and Drugs (Composition and Labelling) Regulations. Hong Kong e-Legislation 1960:47

- 44.Tao L (2018) Revised regulation of food allergen labeling in Taiwan. ChemLinked. https://food.chemlinked.com/news/food-news/revised-regulation-food-allergen-labeling-taiwan

- 45.Food Labeling System. Ministry of Food and Drug Safety. https://www.mfds.go.kr/eng/wpge/m_14/de011005l001.do. Accessed 4 June 2022