Abstract

Asparagus racemosus (A. racemosus) belongs to family Liliaceae and commonly known as Satawar, Satamuli, Satavari found at low altitudes throughout India. The dried roots of the plant are used as drug. The roots are said to be tonic and diuretic and galactgogue, the drug has ulcer healing effect probably via strenthening the mucosal resistance or cytoprotection. It has also been identified as one of the drugs to control the symotoms of AIDS. A. racemosus has also been successfully by some Ayurvedic practitioner for nervous disorder, inflammation and certain infectious disease. However, no scintific proof justify aborementioned uses of root extract of A. racemosus is available so far. Recently few reports are available demonstrating beneficial effects of alcoholic and water extract of the roots of A. racemosus in some clinical conditions and experimentally indused disease e.g. galactogougue affects, antihepatotoxic, immunomodulatory effects, immunoadjuvant effect, antilithiatic effect and teratogenicity of A. racemosus. The present artical includes the detailed exploration of pharmacological properties of the root extract of A. racemosus reported so far.

Keywords: Shatavari, Shatavarins I-IV, Racemosol, Antiageing, Asparagus racemosus, Pharmacology

1. Introduction

Shatavari means “who possesses a hundred husbands or acceptable to many”. It is considered both a general tonic and a female reproductive tonic. Shatavari may be translated as “100 spouses”, implying its ability to increase fertility and vitality. In Ayurveda, this amazing herb is known as the “Queen of herbs”, because it promotes love and devotion. Shatavari is the main Ayurvedic rejuvenative tonic for the female, as is Withania for the male. Asparagus racemosus (family Asparagaceae) also known by the name Shatavari is one of the well known drugs in Ayurveda, effective in treating madhur rasam, madhur vipakam, seet-veeryam, som rogam, chronic fever and internal heat[1],[2]. This herb is highly effective in problems related with female reproductive system. Charak Samhita written by Charak and Ashtang Hridyam written by Vagbhata, the two main texts on Ayurvedic medicines, list Asparagus racemosus (A. racemosus) as part of the formulas to treat women's health disorder[3]–[6]. A. racemosus is a well known Ayurvedic rasayana which prevent ageing, increase longevity, impart immunity, improve mental function, vigor and addvitality to the body and it is also used in nervous disorders, dyspepsia, tumors, inflammation, neuropathy, hepatopathy. Reports indicate that the pharmacological activities of A. racemosus root extract include antiulcer, antioxidant, and antidiarrhoeal, antidiabetic and immunomodulatory activities. A study of ancient classical Ayurvedic literature claimed several therapeutic attributes for the root of A. racemosus and has been specially recommended in cases of threatened abortion and as a galactogogue. Root of A. racemosus has been referred as bitter-sweet, emollient, cooling, nervine tonic, constipating, galactogogue, and aphrodisiac, diuretic, rejuvenating, carminative, stomachic, antiseptic and as tonic. Beneficial effects of the root of A. recemosus are suggested in nervous disorders, dyspepsia, diarrhoea, dysentry, tumors, inflammations, hyper dipsia, neuropathy, hepatopathy, cough, bronchitis, hyperacidity and certain infectious diseases[7],[8]. The major active constituents of A. racemosus are steroidal saponins (Shatavarins I-IV) that are present in the roots. Shatavarin IV has been reported to display significant activity as an inhibitor of core Golgi enzymes transferase in cell free assays and recently to exhibit immuno-modulation activity against specific T-dependent antigens in immuno compromised animals[9].

2. A. racemosus

A. racemosus is common throughout Sri Lanka, India and the Himalayas. It grows one to two metres tall and prefers to take root in gravelly, rocky soils high up in piedmont plains, at 1 300-1 400 m elevation[10,11]. Some plants parts are given in Figure 1.

Figure 1. A. racemosus.

2.1. Scientific classification

Kingdom: Plantae

Clade: Angiosperms

Clade: Monocots

Order: Asparagales

Family: Asparagaceae

Subfamily: Asparagoideae

Genus: Asparagus

Species: A. racemos

It was botanically described in 1799[12]. Due to its multiple uses, the demand for A. racemosus isconstantly on the rise. Due to destructive harvesting, combined with habitat destruction, and deforestation, the plant is now considered endangered in its natural habitat. A. racemosus is recommended in Ayurvedic texts for prevention and treatment of gastric ulcers, dyspepsia and as a galactogogue. A. racemosus has also been used successfully by some Ayurvedic practitioners for nervous disorders[13]. Shatawari has different names in the different Indian languages, such as Shatuli, Vrishya and other terms. In Nepal, it is called Kurilo. The name Shatawari means “curer of a hundred diseases” (shat: “hundred”; variety: “curer”).

2.2. Characteristics of A. racemosus

A. racemosus is a woody climber growing to 1-2 m in height. The leaves are like pine needles, small and uniform and flowers are white and have small spikes. This plant belongs to the genus Asparagus which has recently moved from the sub family Asparagae in the family Liliaceae to a newly created family Asparagaceae.

2.3. Habitat

Its habitat is common at low altitudes in shade and in tropical climates throughout Asia, Australia and Africa. Out of several species of Asparagus grown in India, A. racemosus is most commonly used in indigenous medicine[14].

3. Phytochemicals

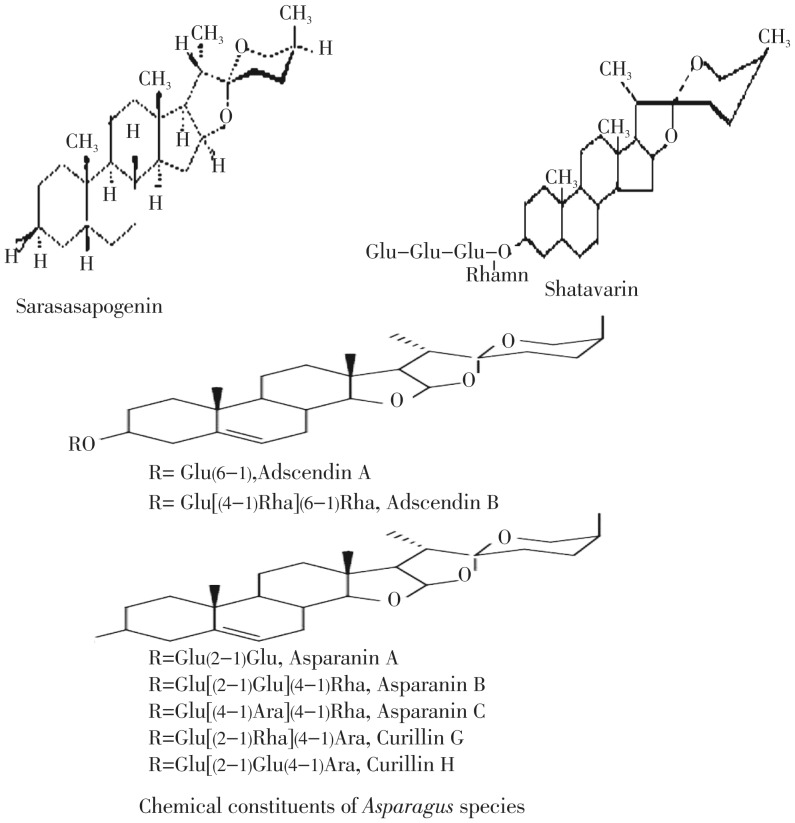

Shatvari is known to possess a wide range of photochemical constituents which are mentioned below. Some of the structures have been drawn in (Figure 2),

Figure 2. Photochemical constituents structures.

Steroidal saponins, known as shatvarins. Shatvarin I to VI are present. Shatvarin I is the major glycoside with 3-glucose and rhamnose moieties attached to sarsapogenin[15]–[18];

Oligospirostanoside referred to as Immunoside[19];

Polycyclic alkaloid-Aspargamine A, a cage type pyrrolizidine alkaloid[20]–[22];

Isoflavones-8-methoxy-5, 6, 4-trihydroxy isoflavone-7-0-beta-D-glucopyranoside[23];

Cyclic hydrocarbon-racemosol, dihydrophenantherene[24], [25];

Furan compound-Racemofuran[26];

Carbohydrates-Polysacharides, mucilage[27];

Flavanoids-Glycosides of quercitin, rutin and hyperoside are present in flower and fruits[28];

Sterols-Roots also contain sitosterol, 4, 6-dihydryxy-2-O (-2-hydroxy isobutyl) benzaldehyde and undecanyl cetanoate[29];

Trace minerals are found in roots-zinc (53.15), manganese (19.98 mg/g), copper (5.29 mg/g), cobalt (22.00 mg/g) along with calcium, magnesium, potassium zinc and selenium[30],[31];

Kaepfrol-Kaepfrol along with Sarsapogenin from woody portions of tuberous roots could be isolated[32];

Miscellaneous-Essential fatty acids-Gamma linoleinic acids, vitamin A, diosgenin, quercetin 3-glucourbnides[33]–[35]. Some chemical structures are given in Figure 2.

4. Pharmacological activity

4.1. Galactogogue effect

The root extract of A.racemosus is prescribed in Ayurveda to increases milk secretion during laction[36]. A. racemosus is combination with other herbal substance in the form of Ricalax tablet (Aphali pharmaceutical Ltd. Ahmednagar) has been shown to increase milk production in females complaining of dificient milk secretion[37]. Gradual decrease in milk secretion, on withdraw of the drug suggested that the increase in milk secretion was due to drug theraphy only and not due to any psychological effect. In the form of a commercial preparation, lactare (TTK Pharma, Chennai) is reported to enhance milk output in women complaining of scantly breast milk, on the 5th day after delivery[38].A significant increase in milk yield has also increase growth of mammary glands, alveolar tissue and acini in guinea pigs[39]. Patel et al. have shown galactogogue effect of A. racemosus in buffaloes[40]. However, Sharma et al. did not observed any increase in prolectin level in females complaining of secondary lactational failure with A.racemosus, suggesting that it has no lactogenic effect[41]. In other study, the aqueous fraction of the alcoholic extract of the roots at 250 mg/kg, administratered intramuscularly, was shown to cause both on increase in the weight of mammary gland lobuloaveolar tissue and in the milk yield of oestrogen primed rats. The activity has attributed to the action of released corticoteroids or an increase in prolactin[42].

4.2. Antisecretory and antiulcer activity

Efficacy of A. racemosus was evaluated in 32 patients by administrating the root powder 12 g/d in four doses, for an average duration of 6 weeks. Shatavari was found to relive most of the symptoms in majority of the patients. The ulcer healing effect of the drug was attributed to a direct to a direct healing effect, possible by potentiating intrinsic protective factor as it has neither antisecretory activity nor antacid propertise, by strengthening mucosal resistance, prolonging the lifespan of mucosal cells, increasing secretion and viscosity of mucous and reducing H+ ion back diffusion. It has been found to maintain the continuity and thickness of asprin treated gastric mucosa with a significant increase in mucosal main. As A. racemosus heals duodenal ulcers without inhibiting acid secretion, it may have cytoprotective action similar action to that of prostaglandin other binding of bile salts[43]–[45].

4.3. Antitussive effect

Methanolic extract of roots, at dose of 200 and 400 mg/kg p.o., showed significant antitussive activity on sulphur dioxide- induce cough in mice. The cough inhibition of 40% and 58.5%, respectively, was comparable to that of 10-20 mg/kg of codeine phosphate, where the inhibition observed 36% and 55.4%, respectively[46].

4.4. Adaptogenic activity

Aqueous extract was administered orally to experimental animals of biological, physical and chemical stressors. A model of cisplatin induced alteration in gastrointestinal motility was used to test the ability of extract to exert a normalising effect, irrespective or direction of pathological change. The extract reversed the effects of cisplatin on gastric emptying and also normalized cisplatin-induced intestinal hyper motility[47].

4.5. Antibacterial activity

Methanolic extract of roots at 50, 100 and 150 mg/mL showed significant In vitro antibacterial efficacy against Escherichia coli, Shigella dysenteriae, Shegella sonnei, Shigella flexneri, Vibriocholerae, Salmonella typhi, Salmonella typhimurium, Pseudomonas pectida, Bacillus subtilis and Staphylococcus aureus. Chloramphenicol was used for comparison[48].

4.6. Antiprotozoal activity

An aqueous solution of the crude alcoholic extract of the roots exhibited an inhibitory effect of the growth of Eintamoeba histolytica in vitro[49].

4.7. Gastrointestinal effects

The powdered dried root of A. racemosus is used in Ayurveda for dysepesia. Oral administration of powdered dried root of A. racemosus has been found to promote gastric emptying in healthy volunteers. Its action is reported to be comparable with that of the synthetic dopamine antagonist metoclopromide[50]. In Ayurveda, A. racemosus has also been mentioned for the treatment of ulcerative disorder of stomach and parinama sula, a clinical entity akin to the duodenal ulcer disease. The juice of fresh root of A. racemosus has been shown to have definite curative effect in patients of duodenal ulcers[51]. A. racemosus along with Terminalia chebula were reported to protect gastric mucosa against pentagastrin and carbachol induce ulcer by significantly reducing both severity of ulceration and ulcer index[52].

In addition to antiulcerogenic activity of A. racemosus is clinical trials[53]. Demonstrated similar effects of fresh root juice of A. racemosus in rats, using cold stress and poloric-ligation induced gastric ulcer. Various extract from the root of A. racemosus have been shown to cause contraction of smooth muscles of rabbits duodenum, guinea pig ileum and rats's fundal strip without affecting peristatic movement. These actions were found to be similar to that of acetylcholine and were blocked by atropine, suggesting a cholinergic mechanism of action[54]. However no effect was observed on isolate rectus abdominus.

4.8. Effect on uterus

Inspite of cholinergic activity of A. racemosus on guniea pig's ileum, ethyl acetate and acetone extract of the root of A. recemosus blocked spontaneous motility of the virgin rat's uterus[54]. These extract also inhibited contraction induced by spasmogens like acetylcholine, barium chloride and 5- hydroxytryptamine where as alcoholic extract was found to produce a specific block of pitocin induced contraction. On the other hand petroleum ether as well as ether extract of the powdered roots did not produce any uterine activity. It indicates the presence of some particular substance in the alcoholic extract which specifically block pitiocin sensitive receptor through not other in the uterus[54]. Confirming the Shatavari receptor can be used as uterin sedative. Further, a glycosides, Shatavarin 1, isolated from the roots of A. racemosus has been found to be responsible for the competitive block of oxytocin induced contraction of rat, guinea pig and rabbits uteri, in vitro as well as in vivo[55],[56].

4.9. Molluscicidal activity

Aqueous and ethanolic extract of A. racemosus exhibited a high mortality rate (100%) against Biomhalaria pfeifferi and Lymnaea natalensis. The LC50 was found to be 0.1, 5, 10 and 50 mg/mL for Biomphalaria pfeifferi and 0.5, 5, 1, 10 mg/mL for Lymnaea natalensis. The activites were attributed to the presence of terpenoids, steroids and saponins in the extract[57].

4.10. Antihepatotoxic activity

Alcoholic extract of root of A. racemosus has been shown to significantly reduce the enhanced levels of alanine transakinase, aspartate transaminase and alkaline phosphate in CCl4 induced heptic damagein rats[58], [59], indicating antihepatotoxic potential of A. racemosus.

4.11. Antineoplastic activity

Choloroform/methanol (1:1) extract of fresh root of A. racemosus has been reported to reduce the tumor incidence in female rats treated with 7, 12 dimethyl benza. This action is suggested to be medicated by virtue of mammotropic and/ or lactogenic[60], influence of A. racemosus on normal as well as estrogen primed animals, which renders the mammary epithelium refractory to the carcinogen[61],[62].

4.12. Cardiovascular effects

Alcoholic extract of the root of A. racemosus has been reported to produce positive ionotropic and chronotropic effect on frog heart with lower doses and cardiac arrest with higher doses. The extract was found to produce hypotension in cats, which was blocked by atropine, indicating cholinergic mechanism of action. The extract also produced congestion and complete stasis of blood flow in mesentric vessels of mice and rat, slight increase in the bleeding time and no effect on clotting time was obseved on i.v. administration of the extract in rabbits[49].

4.13. Effect on central nervours system

Neither stimulant nor depressant action of lactrae on central nervous system has been reported in albino mice[63],[64]. Shatavari did not produce catalepsy in experimental rats, even with massive oral doses, suggesting that its action may be outside the blood-brain barrier, similar to that of metoclopromide.

4.14. Immunomodulatory activity

Intra-abdominal sepsis is major causes of mortality following trauma and bowel surgery. Immunomodulating property of A. racemosus has been shown to protect the rat and mice against experimental induced abdominal sepsis[65],[66]. Oral administration of decotion of powdered root of A. racemosus been reported to produce leucocytosis and predominant neutrophilia along with enhanced phagocytic activity of the macrophages and polymorphs. Parcentage mortality of A. racemosus treated animals was founded significantly reduced while survival rate was comparable to that of the group treated with a combination of metronidazole and gentamicin. Since A. racemosus is reported to be devoid of antibacterial action, so protection offered by A. racemosus against sepsis by altering function of macrophages, indicating its possible immunomodulatory property[65],[66].

4.15. Immunoadjuvant potential activity

The immunoadjuvant potential of A. racemosus aqueous extract root extract was evaluated in experimental animals immunized with diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis vaccine. Immunostimulation was evaluated using serological and hematological parameters. Oral administration of test material at 100 mg/kg per day dose for 15 d resulted significant increase in antibody titre to Boredtella pertussis as compared to untreated (control) animals. Results indicate that the treated animals did show significant increase in antibody titre as compared to untreated animals after change. Applications of test material as potential immunoadjuvant bring less morbidity and mortality to experimental animals[67]–[69].

4.16. Miscellaneous effects

Alcoholic extract of root of A. racemosus was found to have slight diuretic effect in rats and hypoglycemic effect in rabbits, but no anticonvulsant and antifertility effect was observed in rats and rabbits, respectively. However, it did show some antiamoebic effect in rats[49].

4.17. Toxic effect

In Ayurveda, A. racemosus has been descrived as absolutely safe for long term use, even during pregnancy and lactation. Systemic administration of higher doses of all extracts did not produce only abnorbility in behavior pattern of mice and rat[54]. LD50 of the product lactare has not been assessed since it did not produce mortality even up to oral dosage of 64 g/kg[63].

4.18. Antioxidant effects

The possible antioxidant effects of crude extract and purified aqueous fraction of A. racemosus against member damage induced by the free radicals generated during gama radiation were examined in rat liver mitochondria. Gama radiation in those rays of 75-900 Gray, induced lipid peroxidation as assessed by the formation of thiobarbituric acid reactive substances and lipid hydroperoxides. Using an effective dose of 450 Gray antioxidant effect of A. racemosus extract were studied against oxidative damage term of protection against lipid peroxidation, protein oxidation. An active fraction consisting of polysaccharides (P3) was effective even low concentration of 10 mg/mL. Both the crude extract as well as P3 fraction significantly inhibited lipid peroxidation and protein oxidation. The antioxidant effect of P3 fraction was more pronounced against lipid peroxidation, as assessed by thiobarbituric acid reactive substance formation, while that of crude extract was more effective in inhibiting proteins oxidation[9],[26],[70],[71].

4.19. Antilithiatic effects

The ethanolic extract of A. racemosus was evaluated for its inhibitory potential of lithasis (stone formation), induced by oral administration of 0.75% ethylene glycolated water to adult male albino wister rats for 28 d. The ionic chemistry of urine was attered by ethylene glycol, which elevated the urinary concentration of crucial ions viz. calcium, oxalate and phosphate, there by contributing to renal stone formation. The ethanolic extract, however, significantly reduced the elevated level of these ions in urine. Also, it elevated the urinary concentration of magnesium, which is considered as one of the inhibitor of crystallization[72].

4.20. Teratogenicity effects

A. racemosus is a herb used as a rasayna in Ayurveda and is considered both general and female reproduction tonic. Methanolic extract of A. racemosus roots (MAR), 100 mg/kg per day for 60 d, showed teratological disordres in terms of increase resorption of fetuses, gross malformation e.g. swelling in legs and intrauterine growth retardation with a small placenta size in charles foster rats. Pups to mother exposed to A. racemosus for full duration of gestation showed evidence of higher rate of resorption and therefore smaller litter size. The live pup showed significant decrease in body weight and length, and delay of various development parameters when compared to respective control group. Therefore, A. racemosus should be used pregnancy continuously as its exposure during that period may cause damage to the offspring[73].

4.21. Antidepressant activity

Adaptogenic drugs are those which are useful as anti-stress agents by promoting non-specific resistance of the body. Although, the adaptogenic effect of A. racemosus is well documented, its use in psychological disorders like depression is not scientifically evaluated. Hence, the present investigation evaluates the antidepressant effect of MAR standardized to saponins (62.2% w/w). Rats were given methanolic extract of roots of A. racemosus in doses of 100, 200 and 400 mg/kg daily for 7 d and then subjected to forced swim test (FST) and learned helplessness test (LH). The results showed that MAR decreased immobility in FST and increased avoidance response in LH indicating antidepressant activity. In behavioral experiments, MAR increased the number of head twitches produced by 5-HTP and increased clonidine-induced aggressive behavior indicating facilitatory effect on both serotonergic and adrenergic systems respectively. However, MAR had insignificant effect on l-DOPA-induced aggressive behavior indicating absence of activity on dopaminergic system. MAR also reversed changes to the endogenous antioxidant system induced by FST. Thus, MAR has significant antidepressant activity and this effect is probably mediated through the serotonergic, noradrenergic systems and augmentation of antioxidant defenses[74].

4.22. Anti-inflammatory effects

ACE inhibited topical edema in the mouse ear, following administration at 200 mg/kg (i.p.), leading to substantial reductions in skin thickness and tissue weight, inflammatory cytokine production, neutrophil-mediated myeloperoxidase activity, and various histopathological indicators. Furthermore, ACE was effective at reducing inflammatory damage induced by chronic TPA exposure and evoked a significant inhibition of vascular permeability induced by acetic acid in mice[75].

4.23. Enhances memory and protects against amnesia

MAR also significantly reversed scopolamine and sodium nitrite-induced increase in transfer latency on elevated plus maze indicating anti-amnesic activity. Further, MAR dose-dependently inhibited acetylcholinesterase enzyme in specific brain regions (prefrontal cortex, hippocampus and hypothalamus). Thus, MAR showed nootropic and anti-amnesic activities in the models tested and these effects may probably be mediated through augmentation of cholinergic system due to its anti-cholinesterase activity. Post-trial administration of Convolvulus pluricaulis (C. pluricaulis) and A. racemosus extract demonstrated significant decrease in latency time during retention trials. Hippocampal regions associated with the learning and memory functions showed dose dependent increase in AChE activity in Carbonic anhydrase 1 with A. racemosus and Carbonic anhydrase 3 area with C. pluricaulis treatment. The underlying mechanism of these actions of A. racemosus and C. pluricaulis may be attributed to their antioxidant, neuroprotective and cholinergic properties[76],[77].

4.24. Aphrodisiac activity

Lyophilized aqueous extracts obtained from the roots of A. racemosus, Chlorophytum borivilianum, and rhizomes of Curculigo orchioides were studied for sexual behavior effects in male albino rats and compared with untreated control group animals. The rats were evaluated for effect of treatments on anabolic effect. Seven measures of sexual behaviors were evaluated. Administration of 200 mg/kg body weight of the aqueous extracts had pronounced anabolic effect in treated animals as evidenced by weight gains in body and reproductive organs. There was a significant variation in the sexual behavior of animals as reflected by reduction of mount latency, ejaculation latency, post ejaculatory latency, intromission latency, and an increase of mount frequency. Penile erection was also considerably enhanced. Reduced hesitation time (an indicator of attraction towards female in treated rats) also indicated an improvement in sexual behavior of extract treated animals. The observed effects appear to be attributable to the testosterone-like effects of the extracts. Nitric oxide based intervention may also be involved as observable from the improved penile erection. The present results, therefore, support the folklore claim for the usefulness of these herbs and provide a scientific basis for their purported traditional usage[78].

4.25. Diuretic activity

Acute toxicity study showed no fatality even with the highest dose, and the diuretic study revealed significant diuretic activity in dose of 3 200 mg/kg[79].

4.26. Potential to prevent hepatocarcinogenesis

Histopathological studies of hepatic tissues of Wistar rats treated with diethylnitrosamine (DEN) (200 mg/kg body weight, i.p.) once a week for 2 weeks, followed by treatment with Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, a tumor promoter (0.05% in diet) for 2 weeks and kept under observation for another 18 weeks, demonstrated the development of malignancy. Pretreatment of Wistar rats with the aqueous extract of the roots of A. racemosus prevented the incidence of hepatocarcinogenesis. Immunohistochemical staining of the hepatic tissues of rats treated with DEN showed the presence of p53+ foci (clusters of cells expressing the mutated p53 protein), whereas an absence of p53+ foci was observed in Wistar rats pretreated with the aqueous extract of the roots of A. racemosus. The microsections of the hepatic tissue of rats treated with DEN followed by treatment with the aqueous extract of A. racemosus showed an absence of p53+ foci. The results of the biochemical determinations also showed that pretreatment of Wistar rats with the aqueous extract of A. racemosus leadedto the amelioration of oxidative stress and hepatotoxicity brought about by treatment with DEN. These results prove that the aqueous extract of the roots of A. racemosus has the potential to act as an effective formulation to prevent hepatocarcinogenesis induced by treatment with DEN[80].

4.27. Anti-stess activity

Chlorophytum arundinaceum (C.arundinaceum), Asparagus adscendens (A. adscendens) and A. racemosus are used in the Indian traditional medicine system for improving the general state of health and for stress-related immune disorders. The effects of the methanol and aqueous extracts of the tuberous roots of these plants were examined in an experimental mouse stress model, induced by swimming. The extracts were shown to exert an inhibitory effect on pro-inflammatory cytokines, namely interleukin 1β and tumour necrosis factor α, and on the production of nitric oxide in mouse macrophage cells RAW 264.7 stimulated by lipopolysaccharide in vitro. Similar inhibition was also observed in the production of interleukin 2 in EL4 lymphoma cells stimulated by concanavalin A. Corticosterone levels in serum and adrenal glands were measured. The findings suggest that these plants may be beneficial in the management of stress and inflammatory conditions[81],[82].

4.28. Reduce blood glucose

Ethanol extract caused a significant increase in insulin release during 10 min perfusion (P<0.001), with a 21-fold increase above basal (0.06±0.01) ng/mL at 2.8 mmol/L glucose vs. (1.27±0.09) ng/mL with ethanol extract (Figure 2A). Subsequent exposure for 5 min to 11.1 mmol/L glucose caused steep elevation in insulin release. When extract was reintroduced at 11.1 mmol/L glucose, there was a further enhancement of insulin release (P<0.05). As shown in Figure 2B, perfusion with hexane, chloroform and ethyl acetate fractions evokes a significant increase in insulin release in an almost similar pattern, with a peak increase above basal of 36-, 18- and 28-fold, respectively. Aqueous and butanol fractions showed less prominent effects on insulin release, especially at lower glucose concentration[83].

4.29. A versatile female tonic

In Ayurveda, it is considered a female tonic. In spite of being a rejuvenating herb it is beneficial in female infertility, as it increases libido, cures inflammation of sexual organs and even moistens dry tissues of the sexual organs, enhances folliculogenesis and ovulation, prepares womb for conception, prevents miscarriages, acts as post partum tonic by increasing lactation, normalizing uterus and changing hormones. Its use is also advocated in leucorrhoea and menorrhagia[84].

4.30. Cytotoxicity, analgesic and antidiarrhoeal activities

In Ayurveda, A. racemosus is known as the queen of herbs because it has a strong rejuvenating, nurturing and stabilizing effect on excessive air, gas, dryness and agitation in body and mind. Ethanol extracts of A. racemosus was investigated for biological action. The present study was designed to evaluate the cytotoxicity, analgesic and antidiarrhoeal properties of the ethanol extract of whole plant of A. racemosus. The test for analgesic activity of the crude ethanol extract was performed using acetic acid induced writhing model in mice. On the other hand, antidiarrhoeal test of the ethanol extracts of A. racemosus was done according to the model of castor oil induced diarrhoea in mice and brine shrimp lethality bioassay was used to determine cytotoxic activity of ethanol extract of the plant. In acetic acid induced writhing in mice, the ethanol extract exhibited significant inhibition of writhing reflex 67.47% (P<0.01) at dose of 500 mg/kg body weight. The plant extract showed antidiarrhoeal activity in castor oil induced diarrhoea in mice. It increased mean latent period and decreased the frequency of defecation with number of stool count at dose of 250 and 500 mg/kg body weight, respectively comparable to the standard drug Loperamide at dose of 50 mg/kg body weight. In addition, the brine shrimp lethality test showed significant cytotoxic activity of the plant extract (LC50: 10 μg/mL and LC90: 47.86 μg/mL). The obtained results support the traditional uses of the plant and require further investigation to identify the chemical constituent(s) responsible for cytotoxicity, analgesic and antidiarrhoeal activities[85].

4.31. Antiurolithiatic activity

The rats treated with ethanolic extract of A. racemosus at doses 800 and 1 600 mg/kg significantly (P<0.05) reduced the serum concentrations of calcium, phosphorus, urea and creatinine[86].

5. Conclusion

Numerous studies have been conducted on different parts of A. racemosus, this plant has developed as a drug by pharmaceutical industries. A detailed and systematic study is required for identification, cataloguing and documentation of plants, which may provide a meaningful way for promoting traditional knowledge of the medicinal herbal plant.

Acknowledgments

The author are thankful with our deepest core of heart to Dr. SK Jain and Dr. Amita Verma for valuable guidance.

Comments

Background

This is a review paper on the benefits of A. racemosus as an alternative medicine for many diseases. The pharmacological effects exhibited by this plant have been elaborated in depth with citations from studies that have been conducted using this Ayurvedic plant.

Research frontiers

There is no lab experiment being done in this manuscript since it is a review paper. However, the author cited latest and recent publications on works done in this particular field, in which bring the readers to the recent analytical approach for pharmacological potential of this plant.

Related reports

The author cited different papers in this manuscript to support the therapeutic potential of A. racemosus in traditional medicine. Past studies mostly presented the pharmacological activities of this plant done in vitro and in vivo.

Applications

This review summarizes researches conducted on A. racemosus specifically in medicinal field. It is a good source of literature survey for researchers who intended to do studies in this particular field, and using this plant could be applied by most Ayurvedic practitioners in their medication activities to treat patients with different types of diseases.

Peer review

This paper is a good review paper on pharmacological activities of A. racemosus. Citations used are also a good resources for reviewing and very informative to all the Ayurvedic and traditional medical practitioners.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Gogte VM. Ayurvedic pharmacology and therapeutic uses of medicinal plants. Mumbai: SPARC; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frawley D. Ayurvedic healing-a comprehensive guide. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Private Limited; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharma RK, Dash B. Charaka samhita-text with english translation and critical exposition based on Chakrapani Datta's Ayurveda dipika. India: Chowkhamba Varanasi; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garde GK, Vagbhat S. Marathia translation of vagbhat's astangahridya. Uttarstana: Aryabhushana Mudranalaya; 1970. pp. 40–48. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atreya . Ayurvedic healing for women. York: Samuel Weiser Inc; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Srikantha MKR. Appendix and indices. Varanasi: Krishnadas Academy; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharma PV, Charaka S. Chaukhambha orientalis. India: Varanasi; 2001. pp. 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sairam KS, Priyambada NC, Goel RK. Gastroduodenal ulcer protective activity of Asparagus racemosus. An experimental, biochemical and histological study. J Ethnopharmacol. 2003;86(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(02)00342-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kamat JP, Boloor KK, Devasagayam TP, Venkatachalam SR. Antioxdant properties of Asparagus racemosus against damagedinduced by gamma radiation on rat liver mitochondria. J Ethanopharmacol. 2000;71:425–435. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(00)00176-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freeman R. Liliaceae-famine foods. Centre for New Crops and Plant Products, Department of Horticulture & Landscape Architecture. Purdue University. Retrieved 2009

- 11.Wikipedia . Asparagus racemosus. USA: Wikipedia; [Online] available from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Asparagus_racemosus. [Accessed on 12th April, 2012] [Google Scholar]

- 12.United States: Department of Agriculture; 2009. Asparagus racemosus information from NPGS/GRIN. Germplasm resources information network. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goyal RK, Singh J, Lal H. Asparagus racemosus an update. Indian J Med Sci. 2003;57(9):408–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simon D. The wisdom of healing. New York: Harmony Books; 1997. p. 148. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaitonde BB, Jetmalani MH. Antioxytocic action of saponin isolated from Asparagus racemosus Willd (Shatavari) on uterine muscle. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther. 1969;179:121–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joshi JDS. Chemistry of Ayurvedic crude drugs: Part VIII: Shatavari 2. Structure elucidation of bioactive shatavarin I and other glycosides. Indian J Chem Section B Organ Chem. 1988;27(1):12–16. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nair AGR, Subramanian SS. Occurrence of diosgenin in Asparagus racemosus. Curr Sci. 1969;17:414. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patricia YH, Jahidin AH, Lehmann R, Penman K, Kitchinga W, De Vossa JJ. Asparinins, asparosides, curillins, curillosides and shavatarins. Structural clarication with the isolation of shatavarin V, a new steroidal saponin from the root of Asparagus racemosus. Tetrahed Lett. 2006;47:8683–8687. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Handa SS, Suri OP, Gupta VN, Suri KA, Satti NK, Bhardwaj V, et al. et al. Oligospirostanoside from Asparagus racemosus as immunomodulator. US Patent No. 6649745. 2003

- 20.Sekine TN. Fukasawa Structure of asparagamine A, a novel polycyclic alkaloid from Asparagus racemosus. Chem Pharm Bull Tokyo. 1994;42(6):1360–1362. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kukasawa N, Sekine T, Kashiwagi Y, Ruangrungsi N, Murakoshi I. Structure of asparagamine A, a novel polycyclic alkaloid from Asparagus racemosus. Chem Pharm Bull. 1994;42:1360–1362. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sekine TN. TIFFNal structure and relative stereochemistry of a new polycyclic alkaloid, asparagamine A, showing anti-oxytocin activity, isolated from Asparagus racemosus. J Chem Soc. 1995;1:391–393. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saxena VK, Chourasia S. A new isoflavone from the roots of Asparagus racemosus. Fitoterapia. 2001;72:307–309. doi: 10.1016/s0367-326x(00)00315-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boger DL, Mitscher LA, Mullican MD, Drake SD, Kitos P. Antimicrobial and cytotoxic properties of 9, 10-dihydrophenanthrenes: structure-activity studies on juncusol. J Med Chem. 1985;28:1543–1547. doi: 10.1021/jm00148a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sekine TN, Fukasawa A. 9, 10-dihydrophenanthrene from Asparagus racemosus. Phytochemistry. 1997;44(4):763–764. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wiboonpun N, Phuwapraisirisan P, Tip-pyang S. Identification of antioxidant compound from Asparagus racemosus. Phytother Res. 2004;8(9):771–773. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Acharya SR, Acharya NS, Bhangale JO, Shah SK, Pandya SS. Antioxidant and hepatoprotective action of Asparagus racemosus Willd. root extracts. Indian J Exp Biol. 2012;50(11):795–801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharma SC. Constituents of the fruits of Asparagus racemosus Willd. Pharmazie. 1981;36(10):709. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singh J, Tiwari HP. Chemical examination of roots of Asparagus racemosus. J Indian Chem Soc. 1991;68(7):427–428. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Choudhary BK, Kar A. Mineral contents of Asparagus racemosus. Indian Drugs. 1992;29(13):623. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mohanta B, Chakraborty A, Sudarshan M, Dutta RK, Baruah M. Elemental profile in some common medicinal plants of India. Its correlation with traditional therapeutic usage. J Rad Anal Nucl Chem. 2003;258(1):175–179. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ahmad S, Ahmed S, Jain PC. Chemical examination of Shatavari Asparagus racemosus. Bull Medico-Ethano Bot Res. 1991;12(3–4):157–160. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Subramanian SS, Nair AGR. Chemical components of Asparagus racemosus. Curr Sci. 1968;37(10):287–288. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Subramanian SS, Nair AGR. Occurrence of Diosegenin in Asparagus racemosus leaves. Curr Sci. 1969;38(17):414. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tambvekar NR. Ayurvedic drugs in common eye conditions. J Natl Integ Med Assoc. 1985;27(5):13–18. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nadkarni AK. Indian materia medica. 1954. pp. 153–155. Bombay; Popular Book Depot. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Joglekar GV, Ahuja RH, Balwani JH. Galactogogue effect of Asparagus racemosus. Indian Med J. 1967;61:165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sholapurkar ML. Lactare-for improving lactation. Indian Prac. 1986;39:1023–1026. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Narendranath KA, Mahalingam S, Anuradha V, Rao IS. Effect of herbal galactogogue (Lactare) a pharmacological and clinical observation. Med Surg. 1986;26:19–22. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Patel AB, Kanitkar UK. Asparagus racemosus Willd. Form Bordi, as a galactogogue, in buffaloes. Indian Vet J. 1969;46:718–721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sharma S, Ramji S, Kumari S, Bapna JS. Randomized controlled trial of Asparagus racemosus (Shatavari) as a lactogogue in lactational inadequacy. Indian Pediatr. 1996;33:675–677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Joglekar GV, Ahuja RH, Balwani JH. Galactogogue effect of Asparagus racemosus. Indian Med J. 1967;61:165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Singh KP, Singh RH. Clinical trial on Satavari (Asparagus racemosus Willd.) in duodenal ulcer disease. J Res Ay Sid. 1986;7:91–100. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bhatnagar M, Sisodia SS. Antisecretory and antiulcer activity of Asparagus racemosus Willd. Against indomethacin plus phyloric ligation-induced gastric ulcer in rats. J Herb Pharmacother. 2006;6(1):13–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sairam K, Priyambada S, Aryya NC, Goel RK. Gastroduodenal ulcer protective activity of Asparagus racemosus: an experimental, biochemical and histological study. J Ethnopharmacol. 2003;86(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(02)00342-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mandal SC, Kumar CKA, Mohana LS, Sinha S, Murugesan T, Saha BP, et al. et al. Antitussive effect of Asparagus racemosus root against sulfur dioxide-induced cough in mice. Fitoterapia. 2000;71(6):686. doi: 10.1016/s0367-326x(00)00151-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Regh NN, Nazareth HM, Isaac A, Karandikar SM, Dahanukar SA. Immunotherapeutic modulation of intraperitoneal adhesions by Asparagus racemosus. J Postgrad Med. 1989;35:199–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mandal SC, Nandy A, Pal M, Saha BP. Evaluation of antibacterial activity of Asparagus racemosus Willd. root. Phytother Res. 2000;14(2):118–119. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1573(200003)14:2<118::aid-ptr493>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Roy RN, Bhagwager S, Chavan SR, Dutta NK. Preliminary pharmacological studies on extracts of root of Asparagus racemosus (Satavari), Willd, Lilliaceae. J Res Indian Med. 1971;6:132–138. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dalvi SS, Nadkarni PM, Gupta KC. Effect of Asparagus racemosus (Shatavari) on gastric emptying time in normal healthy volunteers. J Postgrad Med. 1990;36:91–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kishore P, Pandey PN, Pandey SN, Dash S. Treatment of duodenal ulcer with Asparagus racemosus Linn. J Res Indian Med Yog Homeo. 1980;15:409–415. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dahanukar S, Thatte U, Pai N, Mose PB, Karandikar SM. Protective effect of Asparagus racemosus against induced abdominal sepsis. Indian Drugs. 1986;24:125–128. [Google Scholar]

- 53.De B, Maiti RN, Joshi VK, Agrawal VK, Goel RK. Effect of some Sitavirya drugs on gastric secretion and ulceration. Indian J Exp Biol. 1997;35:1084–1087. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jetmalani MH, Sabins PB, Gaitonde BB. A study on the pharmacology of various extracts of Shatavari-Asparagus racemosus (Willd) J Res Indian Med. 1967;2:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Joshi J, Dev S. Chemistry of Ayurvedic crude drugs: Part VIIIa-Shatavari-2: Structure elucidation of bioactive Shatavarin-I & other glycosidesb. Indian J Chem. 1988;27:12–16. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pandey SK, Sahay A, Pandey RS, Tripathi YB. Effect of Asparagus racemosus rhizome (Shatavari) on mammary gland and genital organs of pregnant rat. Phytother Res. 2005;19(8):721–724. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chifundera K, Boluku B, Mashimango B. Phytochemical screening and molluscicidal potency of some Zairean medicinal plants. Pharmacol Res. 1993;28(4):333–340. doi: 10.1006/phrs.1993.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhu X, Zhang W, Zhao J, Wang J, Qu W. Hypolipidaemic and hepatoprotective effects of ethanolic and aqueous extracts from Asparagus officinalis L. by-products in mice fed a high-fat diet. J Sci Food Agric. 2010;90(7):1129–1135. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.3923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Muruganadan S, Garg H, Lal J, Chandra S, Kumar D. Studies on the immunostimulant and antihepatotoxic activities of Asparagus racemosus root extract. J Med Arom PI Sci. 2000;22:49–52. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rao AR. Inhibitory action of Asparagus racemosus on DMBA-induced mammary carcinogoenesis in rats. Int J Cancer. 1981;28:607–610. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910280512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sabins PB, Gaitonde BB, Jetmalani M. Effect of alcoholic extract of Asparagus racemosus on mammary glands of rats. Indian J Exp Biol. 1968;6:55–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu W, Huang XF, Qi Q, Dai QS, Yang L, Nie FF, et al. et al. Asparanin A induces G(2)/M cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in human hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;381(4):700–705. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.02.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Narendranath KA, Mahalingam S, Anuradha V, Rao IS. Effect of herbal galactogogue (Lactare) a pharmacological and clinical observation. Med Surg. 1986;26:19–22. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Parihar MS, Hemnani T. Experimental excitotoxicity provokes oxidative damage in mice brain and attenuation by extract of Asparagus racemosus. J Neur Transm. 2004;111(1):1–12. doi: 10.1007/s00702-003-0069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dahanukar S, Thatte U, Pai N, Mose PB, Karandikar SM. Protective effect of Asparagus racemosus against induced abdominal sepsis. Indian Drugs. 1986;24:125–128. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Thatte U, Chhabria S, Karandikar SM, Dahanukar S. Immunotherapeutic modification of E. coli induced abdominal sepsis and mortality in mice by Indian medicinal plants. Indian Drugs. 1987;25:95–97. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gautam M, Saha S, Bani S, Kaul A, Mishra S, Patil D, et al. et al. Immunomodulatory activity of Asparagus racemosus on systemic Th1/Th2 immunity: implications for immune adjuvant potential. J Ethno Pharmacol. 2009;121(2):241–247. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gautam M, Diwanay S, Gairola S, Shinde Y, Patki P, Patwardhan B. Immunoadjuvant potential of Asparagus racemosus aqueous extract in experimental system. J Ethnopharmacol. 2004;91(2–3):251–255. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2003.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sharma P, Chauhan PS, Dutt P, Amina M, Suri KA, Gupta BD, et al. et al. A unique immuno-stimulant steroidal sapogenin acid from the roots of Asparagus racemosus. Steroids. 2011;76(4):358–364. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Takeungwongtrakul S, Benjakul S, H-Kittikun A. Lipids from cephalothorax and hepatopancreas of Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei): Compositions and deterioration as affected by iced storage. Food Chem. 2012;134(4):2066–2074. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Visavadiya NP, Soni B, Madamwar D. Suppression of reactive oxygen species and nitric oxide by Asparagus racemosus root extract using in vitro studies. Cell Mol Biol. 2009;55:1083–1095. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Christina AJ, Ashok k, Packialashmi M. Antilithiatic effect of Asparagus racemosus Willd on ethylene glycol-induced lithiasis in male albino Wistar rats. Exp Clin Pharmacol. 2005;27(9):633–638. doi: 10.1358/mf.2005.27.9.939338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Goel RK, Prabha T, Kumar MM, Dorababu M, Prakash, Singh G. Teratogenicity of Asparagus racemosus Willd. root, an herbal medicine. Indian J Exp Biol. 2006;44(7):570–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Singh GK, Garabadu D, Muruganandam AV, Joshi VK, Krishnamurthy S. Antidepressant activity of Asparagus racemosus in rodent models. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2009;91(3):283–290. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lee do Y, Choo BK, Yoon T, Cheon MS, Lee HW, Lee AY, et al. et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of Asparagus cochinchinensis extract in acute and chronic cutaneous inflammation. J Ethnopharmacol. 2009;121(1):28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ojha R, Sahu AN, Muruganandam AV, Singh GK, Krishnamurthy S. Asparagus recemosus enhances memory and protects against amnesia in rodent models. Brain Cogn. 2010;74(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sharma K, Bhatnagar M, Kulkarni SK. Effect of Convolvulus pluricaulis Choisy and Asparagus racemosus Willd on learning and memory in young and old mice, a comparative evaluation. Indian J Exp Biol. 2010;48(5):479–485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Thakur M, Chauhan NS, Bhargava S, Dixit VK. A comparative study on aphrodisiac activity of some ayurvedic herbs in male albino rats. Arch Sex Behav. 2009;38(6):1009–1015. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9444-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kumar MC, Udupa AL, Sammodavardhana K, Rathnakar UP, Shvetha U, Kodancha GP. Acute toxicity and diuretic studies of the roots of Asparagus racemosus Willd. in rats. West Indian Med J. 2010;59(1):3–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Agrawal A, Sharma M, Rai SK, Singh B, Tiwari M, Chandra R. The effect of the aqueous extract of the roots of Asparagus racemosus on hepatocarcinogenesis initiated by diethyl nitrosamine. Phytother Res. 2008;22(9):1175–1182. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kanwar AS, Bhutani KK. Effects of Chlorophytum arundinaceum, Asparagus adscendens and Asparagus racemosus on pro-inflammatory cytokine and corticosterone levels produced by stress. Phytother Res. 2010;24(10):1562–1566. doi: 10.1002/ptr.3218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Joshi T, Sah SP, Singh A. Antistress activity of ethanolic extract of Asparagus racemosus Willd roots in mice. Indian J Exp Biol. 2012;50(6):419–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hannan JM, Marenah L, Ali L, Rokeya B, Flatt PR, Abdel-Wahab YH. Insulin secretory actions of extracts of Asparagus racemosus root in perfused pancreas, isolated islets and clonal pancreatic beta-cells. J Endocrinol. 2007;192(1):159–168. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.07084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sharma K, Bhatnagar M. Asparagus racemosus (Shatavari): A versatile female tonic. Int J Pharm Biol Arch. 2011;2(3):855–863. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Karmakar UK, Sadhu SK, Biswas SK, Chowdhury A, Shill MC, Das J. Cytotoxicity, analgesic and antidiarrhoeal activities of Asparagus racemosus. J Appl Sci. 2012;12:581–586. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Narumalla J, Somashekara S, Chikkannasetty, Damodaram G, Golla D. Study of antiurolithiatic activity of Asparagus racemosus on albino rats. Indian J Pharmacol. 2012;44(5):576–579. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.100378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]