Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

The relationship between persistent loneliness and Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) is unclear. We examined the relationship between different types of mid-life loneliness and the development of dementia and AD.

METHODS:

Loneliness was assessed in cognitively normal adults by using one item from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale. We defined loneliness as No loneliness; Transient loneliness; Incident loneliness; Persistent loneliness, and applied Cox regression models and Kaplan-Meier plots with dementia and AD as outcomes (n=2,880).

RESULTS:

After adjusting for demographics, social network, physical health, and Apolipoprotein ε4, persistent loneliness was associated with higher (HR, 1.91; 95%CI 1.25–2.90; p<0.01), and transient loneliness with lower (HR, 0.34; 95%CI 0.14–0.84; p<0.05), risk of dementia onset, compared with no loneliness. Results were similar for AD risk.

DISCUSSION:

Persistent loneliness in mid-life is an independent risk factor for dementia and AD, whereas recovery from loneliness suggests resilience to dementia risk.

Keywords: prevention, healthy aging, social isolation, depression, cognitive function, brain health, longitudinal, cohort-study, population-based, APOE4, Mental health

1. Background

Loneliness is a subjective feeling resulting from a perceived discrepancy between desired and actual social relationships.1 Although loneliness does not itself have the status of a clinical disease, it is associated with a range of negative health outcomes, including stress, sleep disturbances, depressive symptoms, cognitive impairment, coronary heart disease, stroke, and mortality.2–9 Notably, trajectories of loneliness may be influenced by people’s contexts, for example, their living arrangements, their need for social support, as well as their physical and mental health (for review, see Akhter-Khan & Au).10 Moreover, individual differences in how one copes with loneliness may correspond to, more generally, how one copes with stressful life events.11

Yet, the relationship between loneliness and dementia is still unclear. Whereas in some studies, loneliness has been associated with increased risk of dementia,6,12,13 other studies do not find these associations (for review, see Sutin et al;6 Penninkilampi et al.)14 One possibility for this discrepancy may be that previous studies only used one-time assessments of loneliness. However, individuals vary in their life experiences, as well as their ability to cope with adverse life events such as bereavement, which may impact interindividual trajectories of loneliness (i.e., continuation versus recovery).11,15 A recent meta-analysis suggests that a person’s experience of loneliness may change, with increasing variability of interindividual differences from midlife to old age, resembling findings for other personality traits.15 Given that the pathogenesis and progression of Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) can span decades, whereas individual feelings of loneliness vary,16 we hypothesized that temporariness of loneliness (i.e., transient form) versus continuation of loneliness (i.e., persistent form) would differentially impact AD risk in older adults.

We aimed to investigate the relationship between individual changes of loneliness in mid-life and risk of dementia and AD 18 years later. To shed light on the relationship between different loneliness groups (transient and persistent loneliness) and the incident of AD, we examined data from the Framingham Heart Study (FHS), specifically investigating (i) whether persistent loneliness more strongly predicted the future development of dementia and AD onsets than transient loneliness and (ii) whether loneliness predicted AD independently from depression and established genetic risk factors for AD, e.g., the Apolipoprotein ε4 (APOE ε4) allele.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

FHS, established in 1948, is a large, population-based, multi-generation cohort with regular health exams.17 Neuropsychological and neurological assessments of dementia and AD have been implemented over decades. The present study used data from the FHS Gen 2 cohort which included multiple assessments of loneliness using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D);18 who had health exams on average every 4 years; the design and selection criteria are described in detail elsewhere.19–21 From four CES-D assessments in total, we chose to include loneliness assessments from exams 6 and 7 in the analyses because exam 8 had a small sample size, and exam 9 was close to the end of follow-up. To study the relationship between midlife loneliness and AD risk, analyses were based on 2,880 participants who (i) were aged 45 years and older at the 7th health exam (1998–2001) (i.e., time zero), (ii) had completed CES-D both at exam 6 (1995–1998) and exam 7, (iii) did not have AD or dementia at exam 7, and (iv) had complete follow-up data on AD and dementia. In total, 384 participants were excluded for not meeting the abovementioned criteria (Supplement Figure 1). For the multivariate analyses when APOE genotype was added, as well as for the subset analysis, another 77 individuals were excluded due to not consenting to the use of their genetic information (APOE genotype). Informed consent was obtained from all study participants, and the study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Boston University Medical Campus.

With exam 7 as time zero, all subjects were followed up to the end of 2018 (18 years maximum) with time-to-events being death or onset of dementia or AD (Supplement Figure 2). This study followed the guidelines reported in the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement.22

2.2. Defining Loneliness

Participants completed the self-reported CES-D (20 items) at exams 6 and 7, including the item “I felt lonely during the past week”. The loneliness score derived from the CES-D was based on a scale of number of days feeling lonely within the past week. We defined loneliness as feeling lonely at least 1–2 days within the past week and further differentiated between the following subgroups of loneliness:

(i) No loneliness (Group 0): Participants did not report loneliness at either exam 6 or exam 7.

(ii) Transient loneliness (Group 1): Participants reported loneliness at exam 6 but did not report loneliness at exam 7.

(iii) Incident loneliness (Group 2): Participants reported loneliness at exam 7 but did not report loneliness at exam 6.

(iv) Persistent loneliness (Group 3): Participants reported loneliness at both exam 6 and exam 7.

2.3. Outcome Variables

Participants suspected of cognitive impairment are classified by expert consensus as to whether they have dementia or not.19 Diagnoses of dementia and AD were based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders fourth edition (DSM-IV) and the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS–ADRDA) criteria, respectively.23 Detailed procedures for the diagnosis of AD dementia within the FHS are reported elsewhere.19,21

2.4. Covariates

Covariates were collected at time zero and included age, sex, education, widowhood, social network index (e.g., number of close friends, social support), living situation (i.e., living alone), and activities of daily living (ADL). Cardiovascular disease (CVD) status at exam 7 was also used as covariate and represented as dichotomous variable (yes/no). Lastly, we stratified participants by APOE genotype: APOE ε4 non-carriers had either APOE ε2- ε2/2, ε2/3, or APOE ε3- ε3/3; APOE ε4 carriers had APOE ε4- ε2/4, ε3/4, or ε4/4.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Analyses were performed using R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, 2019), with significance assessed by a two-tailed value of p < 0.05. In descriptive statistics of all variables, ANOVA was used for continuous variables, and the Chi-square test was used for categorical variables. Kaplan-Meier (KM) plots and Log-rank tests were used to test and compare the onsets of dementia and AD in different subgroups for loneliness. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression models then estimated hazard ratios (HR) of dementia and AD incidence after adjusting for covariates. Transient, incident, and persistent loneliness were entered as single predictors of incident dementia and AD over the follow-up period of up to 18 years, with participants who did not feel lonely as a reference group. Time was measured in years from exam 7 and coded as time-to-incidence with the outcome events followed up until 2018 (Supplementary Figure 2). We built four models with different sets of covariates. Then, we stratified the subjects to test the effect modification. For depression, CES-D scores at exam 7 were modified by excluding the loneliness item in order to derive an independent depression score. This categorical modified score was calculated as the sum of the remaining 19 questions, with a score of ≥ 16 indicating mid-life depression. The subjects were divided into (i) APOE ε4 carriers versus noncarriers; and (ii) modified CES-D < versus ≥ 16 to test whether loneliness was associated with dementia and AD in stratified subgroups.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics of Loneliness Subgroups

The average age of the 2,880 participants was 62.1 ± 9.0 years (mean ± SD), and 1,552 (53.9%) were female (Table 1). Of these, 2,140 (74.3%) participants reported no loneliness, 243 (8.4%) reported transient loneliness, 243 (8.4%) reported incident loneliness, and 254 (8.8%) reported persistent loneliness. Regarding the incident loneliness group, we treated it as a separate group because we did not have further follow-up data to determine whether participants would fit into the persistent or transient loneliness group. The time between exam 6 and exam 7 was approximately 3 years. Table 1 shows that compared with those who reported no loneliness, participants who reported transient, incident, or persistent loneliness were more likely to be female, live alone, be widowed, be depressed, and have smaller social networks. The transient loneliness group had slightly longer follow-up time (~1 year) than the persistent loneliness group. There were no differences in age, education levels, MMSE scores, rates of APOE ε4, ADL, CVD, or diabetes across the four loneliness subgroups.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the total sample and by loneliness status.

| Characteristics | Total sample (n = 2,880) |

Loneliness |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 2,140) |

Transient (n = 243) |

Incident (n= 243) |

Persistent (n = 254) |

P values |

||

|

Age (years),

mean ± SD |

62.1 ± 9.0 | 62.3 ± 8.8 | 59.9 ± 8.9 | 62.3 ± 9.6 | 62.1 ± 9.9 | 0.350 |

| Sex (Female), n (%) | 1552 (53.9) | 1075 (50.2) | 155 (63.8) | 149 (61.3) | 173 (68.1) | <0.001 |

| Education, n1/n (%) | ||||||

| 0 – High school not graduate |

124/2798 (4.4) |

93/124 (75.0) |

7/124 (5.6) |

10/124 (8.1) |

14/124 (11.3) |

Ref. |

| 1 – High school graduate |

777/2798 (27.8) |

575/777 (74.0) |

69/777 (8.9) |

55/777 (7.1) |

78/777 (10.0) |

0.648 |

| 2 – Some college | 742/2798 (26.5) |

544/742 (73.3) |

71/742 (9.6) |

60/742 (8.1) |

67/742 (9.0) |

0.487 |

| 3 – College | 1155/2798 (41.3) |

87/1155 (75.4) |

91/1155 (7.9) |

108/1155 (9.4) |

85/1155 (7.4) |

0.366 |

| APOE ε4, n1/n (%) | 618/2795 (22.1) |

447/2076 (21.5) |

59/240 (24.6) |

55/235 (23.4) |

57/244 (23.4) |

0.636 |

|

Modified CES-D

score ≥ 16, n1/n (%) |

230/2874 (8.0) |

58/2135 (2.7) |

10/243 (4.1) |

61/243 (25.1) |

101/253 (39.9) |

<0.001 |

|

Living alone,

n1/n (%) |

323/2876 (11.2) |

160/2136 (7.5) |

44/243 (18.1) |

51/243 (21.0) |

68/254 (26.8) |

<0.001 |

| MMSE, mean ± SD | 28.7 ± 1.6 | 28.7 ± 1.6 | 28.9 ± 1.4 | 28.7 ± 1.8 | 28.6 ± 1.6 | 0.794 |

| CVD, n (%) | 284 (9.9) | 202 (9.4) | 22 (9.1) | 29 (11.9) | 31 (12.2) | 0.341 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 204 (7.1) | 157 (7.3) | 18 (7.4) | 11 (4.5) | 18 (7.1) | 0.447 |

| Widowhood, n1/n (%) | 274/2874 (9.5) |

142/2134 (6.7) |

30/243 (12.3) |

44/243 (18.1) |

58/254 (22.8) |

<0.001 |

| ADL, n, mean ± SD | 2879 6.0 ± 0.2 |

2139 6.0 ± 0.1 |

243 6.0 ± 0.3 |

243 6.0 ± 0.3 |

254 6.0 ± 0.3 |

0.028 |

| SNI, n, mean ± SD | 2857 6.6 ± 2.3 |

2127 7.0 ± 2.1 |

241 5.9 ± 2.4 |

242 5.5 ± 2.6 |

247 5.0 ± 2.7 |

<0.001 |

|

Follow-up (years),

mean ± SD |

14.9 ± 4.0 | 14.9 ± 4.0 | 15.2 ± 3.9 | 14.6 ± 4.2 | 14.1 ± 4.6 | 0.011 |

Loneliness was defined as feeling lonely at least 1–2 days within the past week. The four loneliness groups were defined as: No loneliness = participants did not report loneliness at neither exam 6 nor exam 7; Transient loneliness = participants reported loneliness only at exam 6; Incident loneliness = participants reported loneliness only at exam 7; Persistent loneliness = participants reported loneliness at both exam 6 and exam 7; APOE ε4 = apolipoprotein ε4; Modified CES-D = total CES-D score without the loneliness item; MMSE = Mini Mental State Exam; CVD = cardiovascular disease; ADL = Activities of Daily Living; SNI = Berkman-Syme Social Network Index. The quantitative variables (Mean ± SD) with one-way ANOVA was used to test differences among loneliness groups, and Chi-square (χ2) test was used to compare categorical variables (n/total %). P values for statistical significance are shown for the comparisons.

3.2. The Associations between the Loneliness Groups and AD Dementia Development

Next, we studied the relationship between self-reported loneliness in mid-life and the development of dementia and AD. Of the 218 (7.6%) individuals who developed dementia, 177 (81.2%) were diagnosed with AD. The average time to follow-up from time zero was 14.9 ± 4.0 years (mean ± SD). Using Chi-square analyses, we examined the relationship between loneliness subgroups and risk for dementia and AD incidence. Compared with the participants who had no loneliness, those with transient loneliness had lower risk of developing both dementia (2.1 % vs. 7.5%, p < 0.01) and AD (2.1 % vs. 6.0%, p < 0.01), those with incident loneliness showed no significant difference in both dementia (7.4 % vs. 7.5%, p > 0.05) and AD (7.0 % vs 6.0%, p > 0.05), whereas those with persistent loneliness had higher risk, of developing both dementia (13.4% vs. 7.5%, p < 0.01) and AD (10.6% vs. 6.0%, p < 0.01) (Figure 1). Consistently, using Kaplan-Meier plots and Log-rank tests, we found that those with persistent loneliness were more likely to develop dementia as well as AD onset, but those with transient loneliness were less likely to develop dementia and AD onset (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Accumulative rates and Log-rank test analysis for dementia and AD based on loneliness status.

Loneliness was defined as feeling lonely at least 1–2 days within the past week. No loneliness = participants did not report loneliness at neither exam 6 nor exam 7; Transient loneliness = participants reported loneliness only at exam 6; Incident loneliness = participants reported loneliness only at exam 7. Persistent loneliness = participants reported loneliness at both exam 6 and exam 7. The incident dementia (A) and the incident AD (B) between those with no loneliness and with different groups of loneliness were compared by using Chi-square (χ2) test. Kaplan-Meier method (C, D) was used to show the survival curves of up to 18 years of follow-up and the Log-rank test was used to compare the survival curves of loneliness with the no loneliness group as reference. Statistical significance is shown as * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001; **** p < 0.0001.

Using Cox regression analyses, persistent loneliness in mid-life remained associated with the risk of subsequent dementia and AD after accounting for covariates including age, sex, education, widowhood (Model 1), social network, living alone (Model 2), CVD, diabetes, ADL (Model 3), and APOE ε4 (Model 4) (Table 2, Supplement Table 1). Transient loneliness remained associated with lower risk of dementia 18 years later (HR, 0.34; 95% CI 0.14–0.84; p < 0.05), whereas persistent loneliness remained associated with a higher risk of dementia (HR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.25–2.90; p < 0.01) in the final model (Supplement Table 1). Similarly, transient and persistent loneliness were associated with AD risk independently after adjusting for the same covariates (Table 2). Other factors independently predicting dementia and AD in the final model were age, widowhood (not for AD), ADL, and APOE ε4. When APOE ε4 was included in Model 4, the strength of the association between persistent loneliness and dementia risk was reduced (HR changed from 2.00 to 1.91 for dementia and from 1.91 to 1.76 for AD, respectively).

Table 2.

Multivariate Cox hazard models for the relationship between loneliness and Alzheimer’s disease

| Variables | Cox hazard models, event = AD, HR (95%CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 (n = 2,792) |

Model 2 (n = 2,766) |

Model 3 (n = 2,765) |

Model 4 (n = 2,688) |

|

| Loneliness | ||||

| Transient | 0.38 (0.15,0.93) * | 0.41 (0.17,1.01) | 0.41 (0.17,1.01) | 0.41 (0.16,1.00) * |

| Incident | 0.99 (0.58,1.70) | 0.99 (0.57,1.75) | 0.98 (0.56,1.73) | 0.91 (0.52,1.60) |

| Persistent | 1.79 (1.17,2.76) ** | 1.92 (1.21,3.06) ** | 1.91 (1.20,3.06) ** | 1.76 (1.09,2.82) * |

| Age (years) | 1.18 (1.15,1.21) *** | 1.18 (1.15, 1.21) *** | 1.18 (1.15, 1.21) *** | 1.19 (1.16, 1.22) *** |

| Sex (Female) | 1.18 (0.85,1.63) | 1.22 (0.87,1.71) | 1.24 (0.88,1.75) | 1.35 (0.95,1.91) |

| Education | ||||

| 1 - High school | 0.74 (0.44,1.26) | 0.77 (0.43,1.38) | 0.77 (0.43,1.38) | 0.80 (0.45,1.43) |

| 2 - Some college | 0.68 (0.39,1.17) | 0.72 (0.40,1.30) | 0.73 (0.41,1.32) | 0.72 (0.40,1.30) |

| 3 - College | 0.60 (0.35,1.05) | 0.64 (0.35,1.16) | 0.64 (0.36,1.17) | 0.59 (0.32,1.06) |

| Widowhood | 1.09 (0.74,1.60) | 1.36 (0.88,2.10) | 1.37 (0.88,2.12) | 1.42 (0.93,2.18) |

| SNI | 1.05 (0.98,1.13) | 1.05 (0.98,1.13) | 1.04 (0.96,1.11) | |

| Living alone | 0.72 (0.45,1.15) | 0.73 (0.46,1.16) | 0.70 (0.44,1.12) | |

| CVD | 1.18 (0.77,1.81) | 1.10 (0.72,1.68) | ||

| Diabetes | 1.55 (0.96,2.49) | 1.52 (0.95,2.44) | ||

| ADL | 0.58 (0.38,0.87) ** | 0.55 (0.37,0.82) ** | ||

| APOE ε4 | 3.02 (2.19,4.15) *** | |||

Loneliness was defined as feeling lonely at least 1–2 days within the past week. No loneliness = participants did not report loneliness at neither exam 6 nor exam 7; Transient loneliness = participants reported loneliness only at exam 6; Incident loneliness = participants reported loneliness only at exam 7; Persistent loneliness = participants reported loneliness at both exam 6 and exam 7; APOE ε4 = apolipoprotein E4; CVD = cardiovascular disease; ADL = Activities of Daily Living; SNI = Berkman-Syme Network Index.

Cox model (Proportional hazards regression), with no loneliness as a reference group, was used to investigate the effects of transient and persistent loneliness on the incidence of AD. Model 1: adjustment for covariates including age, sex, education (reference as not graduated from high school), widowhood; Model 2: model 1 plus SNI and living alone; Model 3: model 2 plus CVD, diabetes, and ADL; Model 4: model 3 plus APOE ε4. Statistical significance is shown as

, p < 0.05;

, p < 0.01;

, p < 0.001

When including loneliness measures in additional analyses from one timepoint only (i.e., only exam 6 or only exam 7)––to see whether previous findings could be replicated––we did not find a significant relationship between loneliness and dementia or AD. Regarding incident loneliness, this group was similar to the no loneliness group (Table 2, Figure 1). Lastly, we found that loneliness was not associated with future death (Supplement Table 2) and brain lobe volumes (MRI) (data not shown).

3.3. Stratifications for Genetic Risk and Depression

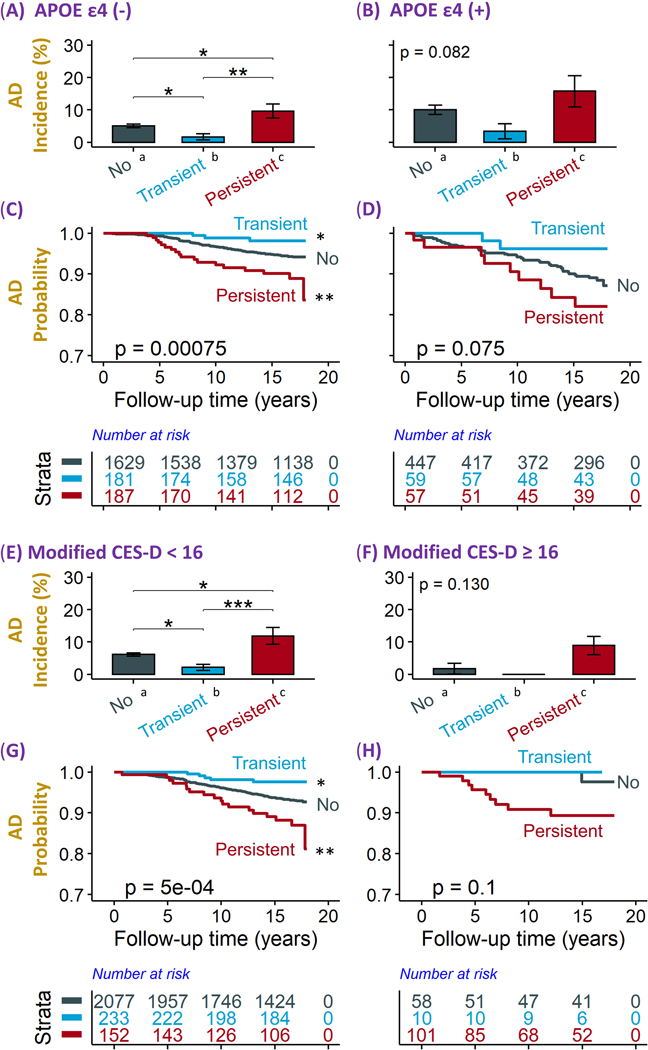

We divided the participants into those who were APOE ε4 carriers (n=563) versus noncarriers (n=1,997). In the absence of APOE ε4, individuals with persistent loneliness had a higher risk of developing dementia or AD, and individuals with transient loneliness had lower risk of developing dementia or AD, compared with the no loneliness group (Figure 2 A, C, Supplement Figure 3 A, C); in the presence of APOE ε4, the associations between mid-life loneliness and the development of dementia or AD were not statistically significant (Figure 2 B, D, Supplement Figure 3 B, D).

Figure 2. Accumulative rates and Log-rank test analysis for AD based on loneliness status stratified by APOE ε4 genotype and depression status.

Loneliness was defined as feeling lonely at least 1–2 days within the past week. No loneliness = participants did not report loneliness at neither exam 6 nor exam 7; Transient loneliness = participants reported loneliness only at exam 6; Persistent loneliness = participants reported loneliness at both exam 6 and exam 7.

A-B and E-F: Subjects were stratified into those without (A) and with (B) APOE ε4 allele; those without (E) and with (F) depression (modified CES-D score ≥ 16). Then, they were further divided into those with no loneliness, with transient loneliness, and with persistent loneliness (X-axis). The incident rates of AD (Y-axis) between those with no loneliness and with different groups of loneliness in each subgroup were compared using Chi-square (χ2) test.

C-D and G-H: Subjects were stratified into those without (C) and with (D) APOE ε4 allele; those without (G) and with (H) depression (modified CES-D score ≥ 16). They were further divided into no loneliness, transient loneliness, and persistent loneliness. Kaplan-Meier method was used to show the survival curves of up to 18 years of follow-up and the Log-rank test was used to compare the survival curves of loneliness with the no loneliness group as reference.

Statistical significance is shown as * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001; **** p < 0.0001.

Consistently, using Cox regression models, in APOE ε4 noncarriers, the persistent loneliness group was more than twice as likely to develop dementia (HR, 2.32; 95% CI, 1.49–3.62; p < 0.001) and the transient loneliness group was less likely to develop dementia (HR, 0.29; 95% CI, 0.09–0.92; p < 0.05) compared with the no loneliness group, after adjusting for demographic, social, and health risk factors (Table 3). In contrast, in the APOE ε4 carriers, the association between loneliness and dementia did not reach statistical significance. Similar patterns of associations were found between loneliness groups (transient and persistent loneliness) and the incident of AD as an outcome in the presence of APOE ε4 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate Cox hazard models for the association between loneliness and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease stratified by APOE ε4 allele

| Variables | Dementia (all types) | AD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APOE ε4 noncarriers (n = 1,942) |

APOE ε4 carriers (n = 551) |

APOE ε4 noncarriers (n = 1,942) |

APOE ε4 carriers (n = 554) |

||

| Loneliness | |||||

| Transient | 0.29 (0.09,0.92) * | 0.41 (0.10,1.69) | 0.35 (0.11,1.13) | 0.45 (0.11,1.86) | |

| Persistent | 2.32 (1.49,3.62) *** | 1.15 (0.56,2.38) | 2.10 (1.25,3.52) ** | 1.28 (0.62,2.66) | |

| Age (years) | 1.19 (1.162,1.22) *** | 1.16 (1.12,1.20) *** | 1.22 (1.18,1.26) *** | 1.16 (1.12,1.21) *** | |

| Sex (Female) | 0.93 (0.65,1.33) | 1.33 (0.77,2.28) | 0.99 (0.66,1.50) | 1.67 (0.94,2.99) | |

| Education | |||||

| 1 - High school | 0.99 (0.54,1.85) | 0.48 (0.20,1.19) | 1.19 (0.57,2.48) | 0.50 (0.20,1.23) | |

| 2 - Some college | 0.83 (0.44,1.57) | 0.39 (0.15,0.99) * | 1.04 (0.50,2.19) | 0.35 (0.13,0.90) * | |

| 3 - College | 0.67 (0.35,1.29) | 0.48 (0.20,1.14) | 0.78 (0.36,1.71) | 0.40 (0.17,0.99) * | |

| ADL | 0.56 (0.35,0.90) * | 0.53 (0.29,0.97) * | 0.58 (0.32,1.03) | 0.54 (0.30,0.99) * | |

Loneliness was defined as feeling lonely at least 1–2 days within the past week. No loneliness = participants did not report loneliness at neither exam 6 nor exam 7; Transient loneliness = participants reported loneliness only at exam 6; Persistent loneliness = participants reported loneliness at both exam 6 and exam 7; APOE ε4 = apolipoprotein ε4; ADL = Activities of Daily Living. Cox model (Proportional hazards regression), with no loneliness as a reference group, was used to investigate the effects of transient and persistent loneliness on the incident of dementia and AD cases after adjustment for covariates including age, sex, education (reference as not graduated from high school), and ADL. The same model was conducted in the absence and the presence of APOE ε4 allele. Statistical significance is shown as

, p < 0.05;

, p < 0.01;

, p < 0.001

Next, to investigate whether the effect of loneliness on dementia and AD differed by depression status in mid-life, we divided the participants into those who had modified CES-D scores < 16 (i.e., not depressed, n=2,462) and those who had modified CES-D scores ≥ 16 (i.e., depressed, n=169) at exam 7. In the absence of depression, compared with the no loneliness group, individuals with persistent loneliness had a higher risk, but individuals with transient loneliness had a lower risk of developing dementia and AD (p < 0.01 in KM curve) (Figure 2 E, G; Supplement Figure 3 E, G). Using Cox regression models, persistent loneliness was associated with a higher risk of dementia (HR, 2.00; 95% CI =1.20–3.25; p < 0.01) and AD (HR, 2.00; 95% CI =1.14–3.50; p < 0.05), and transient loneliness with a lower risk of dementia (HR, 0.37, 95% CI = 0.15–0.90; p < 0.05), and with a non-significant lower tendency in AD (HR, 0.42, 95% CI = 0.17–1.04; p > 0.05) among participants who were not depressed in mid-life. Notably, the trajectories of the four loneliness groups were significantly associated with the trajectories of depression (when also grouped into “no”, “transient”, “incident”, and “persistent” depression over exams 6 and 7; p < 0.0001; Supplement Table 3). Still, of those who were in the persistent loneliness group (n=253), 111 (43.9%) were not depressed. The data jointly indicates that loneliness was a risk factor independent from depression in mid-life for the development of AD dementia.

4. Discussion

In the present study, we examined the associations between loneliness in mid-life and the development of dementia and AD onsets in cognitively healthy adults of the FHS over an 18-year follow-up. Results showing that persistent loneliness was associated with an increased risk of AD dementia are consistent with previous longitudinal findings.6,12,13 Contrary to findings from a previous study that examined the effects of transient and persistent loneliness on measures of cognitive functioning,16 we found that transient loneliness was associated with lower risk for AD dementia in the study sample, when compared with no loneliness. Given that we did not find associations between loneliness at a single timepoint and the risk of AD or dementia, our results may add on to the explanation––next to different measurements of loneliness––why some studies previously found associations between loneliness and dementia, whereas others did not.6,14

Loneliness is a subjective psychological feeling impacted by multiple factors including (i) changing life events (e.g., bereavement),15 (ii) environmental conditions (e.g., isolation),25 and (iii) genetic vulnerability.26 In our study, mid-life loneliness was associated with AD risk independently from the AD risk factors APOE ε4 and depression.27–29 Previous studies reported associations of loneliness with AD hallmarks––amyloid burden and tauopathy––in brains of older adults with normal cognition and found stronger associations among APOE ε4 carriers.24,30 Whereas the association between persistent loneliness and AD risk was strong in APOE ε4 noncarriers, this relationship did not reach statistical significance in APOE ε4 carriers, possibly due to a small number of APOE ε4 carriers. Our results support Hawkley and Cacioppo’s 26 proposal that loneliness is an independent risk factor for AD,5,12,13 and may have unique mechanisms on cognitive functioning, although causal effects of loneliness and depression on cognitive decline may not be distinct.7,31

We found transient loneliness to be protective for the development of dementia, compared to no loneliness. Our finding may point to differences in personality traits and psychological resilience following adverse life events. Various socio-environmental factors are known to influence trajectories of loneliness.32 For instance, loneliness is found to be strongly associated with widowhood across multiple studies.25 Widowhood may lead to differential trajectories of loneliness, depending on how people adapt to bereavement (e.g., resilient widowers show lower levels of loneliness compared with vulnerable widowers).11 In our study, 274 individuals were widowed at time zero. Still, more than half of them did not feel lonely during our examinations, 58 (21.2%) felt lonely persistently, and 30 (10.9%) felt lonely transiently. In accordance with previous studies,25 our results show that loneliness––especially persistent loneliness––is associated with the status of living alone. Yet, widowhood and living alone were not directly associated with AD onset when included in regression analysis, suggesting that persistent loneliness, but not stressful life events per se, negatively impacts cognitive aging. Further, one may hypothesize that individuals feeling transient loneliness may cope with bereavement resiliently by engaging in more daily activities, which in turn may promote social and physical integration and engagement in stimulating environments. Accordingly, higher engagement in diverse activities has been shown to predict cognitive functioning.33 Whereas persistent loneliness states a threat to brain health, psychological resilience following adverse life experiences may explain why transient loneliness is protective in the context of dementia onset.

Although the diverging effects of the loneliness groups (transient and persistent loneliness) on the incident of dementia and AD in FHS need to be confirmed by other cohorts, there may be differential underlying neurobiological mechanisms between these groups. For instance, one may hypothesize that elevated inflammatory responses are especially pertinent to persistent loneliness2,7,26 and could lead to changes in neuroplasticity in areas crucial for healthy cognitive aging.34 Inflammatory factors may be associated with the trajectory of loneliness, especially the persistent form. Indeed, studies suggest a strong link between chronic stress underlying prolonged loneliness and other inflammatory indicators, such as greater activation of glucocorticoids and hypercortisolism.2,7 According to the social allostasis model,7 prolonged engagement of mechanisms normally recruited for short-term adaptations play a vital role in negative consequences of perceived isolation. For example, transient loneliness may activate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis to downregulate inflammatory responses, whereas persistent loneliness is associated with elevated inflammatory responses leading to overactivity of the HPA axis,7,26 thus, losing its efficiency.

In light of the current Coronavirus pandemic (Covid-19), more older adults––especially those who were infected with the virus and experienced long-term isolation––may have persistent feelings of loneliness.34 In fact, older Covid-19 survivors showed a higher risk of developing dementia.35 Thus, future studies are needed to investigate the underlying mechanisms of loneliness and AD. In summary, our findings are in line with evolutionary theories stating that loneliness could be both adaptive and maladaptive for humans,7,32 depending on its persistency.

Our study has some limitations. Loneliness was measured as a single item within the CES-D, which is not a multi-dimensional scale and may not accurately account for real life experiences of loneliness.10 The lack of more frequent data collection on loneliness between exams 6 and 7 limits our assessment of how persistent or transient the feeling of loneliness actually was. We also do not know whether participants who felt lonely at exam 7 (“incident loneliness”) would belong to the transient or persistent group if we had more follow-ups. In addition, our data does not allow to further investigate widowhood status with loneliness and AD in more detail as we do not know when the participant’s spouses passed away, likely influencing their loneliness status. Further, we did not find associations between loneliness and brain volume measurements in FHS when investigating brain lobes and whole hippocampal volume. Yet, Düzel and colleagues36 found associations between loneliness and smaller grey matter volumes of the left amygdala/anterior hippocampus and the left posterior parahippocampus; brain areas relevant to emotional appraisal and cognitive functioning. Unfortunately, FHS did not have such detailed measurements of the temporal lobe. Future studies will need to address the underlying neural mechanisms of loneliness and cognitive functioning to investigate whether reducing loneliness could potentially protect from AD, as there is yet not data to proof this hypothesis. Lastly, all participants in FHS were White Americans, but studies show that loneliness is coped with differently depending on the cultural context, e.g., religious coping,37 which increases the necessity to replicate our findings in other, more diverse study samples.

5. Conclusion

Ultimately, findings from the FHS suggest that mid-life loneliness may be an independent, modifiable risk-factor for dementia and AD. In light of rapid globalization and population aging, more people may experience increasingly stressful life events, such as loss of spouse, living alone, financial distress, environmental disasters, medical illness, and pandemics, which are all likely to exacerbate loneliness. Our results motivate further investigation of the factors that make individuals resilient against adverse life events and urges to tailor interventions to the right person at the right time10 to avert persistency of loneliness, promote brain health and AD prevention. Finally, if reducing loneliness will actually prevent AD onset remains an open question for future research.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We want to express our thanks to the FHS participants for their decades of dedication and to the FHS staff for their hard work in collecting and preparing the data. We also thank Leon Li for his helpful feedback on an earlier draft of this manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute contract (N01-HC-25195) and by grants from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, NS-17950 and from the National Institute on Aging AG-022476 (RA); AG-09899 (WQ) and K24AG050842 (WQ). The sponsor institutes did not play any role in design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Qiushan Tao and Ting Fang Alvin Ang had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

Declarations of interest: none

References

- 1.Peplau LA, Perlman D. Perspectives on loneliness. In: Peplau LA, Perlman D, eds. Loneliness: A source-book of current theory, research and therapy. New York (US): Wiley; 1982:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boss L, Kang DH, Branson S. Loneliness and cognitive function in the older adult: A systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2015;27(4):541–553. doi: 10.1017/S1041610214002749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, Crawford LE, et al. Loneliness and health: Potential mechanisms. Psychosom Med. 2002;64(3):407–417. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200205000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, Thisted RA. Perceived social isolation makes me sad: 5-year cross-lagged analyses of loneliness and depressive symptomatology in the Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study. Psychol Aging. 2010;25(2):453–463. doi: 10.1037/a0017216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holwerda TJ, Deeg DJ, Beekman AT, et al. Feelings of loneliness, but not social isolation, predict dementia onset: Results from the Amsterdam Study of the Elderly (AMSTEL). J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014;85(2):135–142. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2012-302755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sutin AR, Stephan Y, Luchetti M, Terracciano A. Loneliness and risk of dementia. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2020;75(7):1414–1422. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gby112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quadt L, Esposito G, Critchley HD, Garfinkel SN. Brain-body interactions underlying the association of loneliness with mental and physical health. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2020;116:283–300. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Baker M, Harris T, Stephenson D. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015;10(2):227–237. doi: 10.1177/1745691614568352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valtorta NK, Kanaan M, Gilbody S, Ronzi S, Hanratty B. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke: Systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal observational studies. Heart. 2016;102(13):1009–1016. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akhter-Khan SC, Au R. Why loneliness interventions are unsuccessful: A call for precision health. Adv Geriatr Med Res. 2020;2(3):e200016. doi: 10.20900/agmr20200016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bennett KM, Morselli D, Spahni S, Perrig-Chiello P. Trajectories of resilience among widows: A latent transition model. Aging Ment Health. 2020;24(12):2014–2021. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2019.1647129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rafnsson SB, Orrell M, d’Orsi E, Hogervorst E, Steptoe A. Loneliness, social integration, and incident dementia over 6 years: Prospective findings from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2020;75(1):114–124. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbx087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilson RS, Krueger KR, Arnold SE, et al. Loneliness and risk of Alzheimer disease. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(2):234–240. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.2.234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Penninkilampi R, Casey AN, Singh MF, Brodaty H. The association between social engagement, loneliness, and risk of dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;66(4):1619–1633. doi: 10.3233/JAD-180439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mund M, Freuding MM, Möbius K, Horn N, Neyer FJ. The stability and change of loneliness across the life span: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2020;24(1):24–52. doi: 10.1177/1088868319850738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhong BL, Chen SL, Conwell Y. Effects of transient versus chronic loneliness on cognitive function in older adults: Findings from the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;24(5):389–398. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2015.12.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mahmood SS, Levy D, Vasan RS, Wang TJ. The Framingham Heart Study and the epidemiology of cardiovascular disease: a historical perspective. Lancet. 2014;383(9921):999–1008. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61752-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Au R, Seshadri S, Wolf PA, et al. New norms for a new generation: Cognitive performance in the Framingham offspring cohort. Exp Aging Res. 2004;30(4):333–358. doi: 10.1080/03610730490484380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feinleib M, Kannel WB, Garrison RJ, McNamara PM, Castelli WP. The Framingham Offspring Study. Design and preliminary data. Prev Med. 1975;4(4):518–525. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(75)90037-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Satizabal CL, Beiser AS, Chouraki V, Chêne G, Dufouil C, Seshadri S. Incidence of dementia over three decades in the Framingham Heart Study. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(6):523–532. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. PLoS Med. 2007;4(10):e296. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: Report of the NINCDS‐ADRDA work group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. 1984;34(7):939–939. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.d’Oleire Uquillas F, Jacobs HIL, Biddle KD, et al. Regional tau pathology and loneliness in cognitively normal older adults. Transl Psychiatry. 2018;8(1):282. doi: 10.1038/s41398-018-0345-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cohen-Mansfield J, Hazan H, Lerman Y, Shalom V. Correlates and predictors of loneliness in older-adults: A review of quantitative results informed by qualitative insights. Int Psychogeriatr. 2016;28(4):557–576. doi: 10.1017/S1041610215001532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness matters: A theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med. 2010;40(2):218–227. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9210-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu CC, Kanekiyo T, Xu H, Bu G. Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer disease: Risk, mechanisms and therapy. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013;9(2):106–118. doi: 10.1038/nmeurol.2013.32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ownby RL, Crocco E, Acevedo A, John V, Loewenstein D. Depression and risk for Alzheimer disease: Systematic review, meta-analysis, and metaregression analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(5):530–538. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.5.530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poey JL, Burr JA, Roberts JS. Social connectedness, perceived isolation, and dementia: Does the social environment moderate the relationship between genetic risk and cognitive well-being? Gerontologist. 2017;57(6):1031–1040. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Donovan NJ, Okereke OI, Vannini P, et al. Association of higher cortical amyloid burden with loneliness in cognitively normal older adults. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(12):1230–1237. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.2657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Donovan NJ, Wu Q, Rentz DM, Sperling RA, Marshall GA, Glymour MM. Loneliness, depression and cognitive function in older U.S. adults. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;32(5):564–573. doi: 10.1002/gps.4495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goossens L, van Roekel E, Verhagen M, et al. The genetics of loneliness: Linking evolutionary theory to genome-wide genetics, epigenetics, and social science. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015;10(2):213–226. doi: 10.1177/1745691614564878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee S, Charles ST, Almeida DM. Change is good for the brain: Activity diversity and cognitive functioning across adulthood [published online ahead of print, 2020 Feb 6]. J Gerontol B: Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2020;gbaa020. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbaa020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dahlberg L Loneliness during the COVID-19 pandemic [published online ahead of print, 2021 Jan 25]. Aging Ment Health. 2021;1–4. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2021.1875195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taquet M, Luciano S, Geddes JR, Harrison PJ. Bidirectional associations between COVID-19 and psychiatric disorder: retrospective cohort studies of 62 354 COVID-19 cases in the USA. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(2):130–140. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30462-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Düzel S, Drewelies J, Gerstorf D, et al. Structural brain correlates of loneliness among older adults. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):13569. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-49888-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rokach A, Orzeck T, Neto F. Coping with loneliness in old age: A cross-cultural comparison. Current Psychology. 2004;23(2):124–137. doi: 10.1007/BF02903073 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.