Abstract

Objective

To describe the surgical technique and early clinical results after a one-stage laparoscopic-assisted endorectal colon pull-through for Hirschsprung’s disease.

Summary Background Data

Recent trends in surgery for Hirschsprung’s disease have been toward earlier repair and fewer surgical stages. A one-stage pull-through for Hirschsprung’s disease avoids the additional anesthesia, surgery, and complications of a colostomy. A laparoscopic-assisted approach diminishes surgical trauma to the peritoneal cavity.

Methods

The technique uses four small abdominal ports. The transition zone is initially identified by seromuscular biopsies obtained laparoscopically. A colon pedicle preserving the marginal artery is fashioned endoscopically. The rectal mobilization is performed transanally using an endorectal sleeve technique. The anastomosis is performed transanally 1 cm above the dentate line. This report discusses the outcome of primary laparoscopic pull-through in 80 patients performed at six pediatric surgery centers over the past 5 years.

Results

The age at surgery ranged from 3 days to 96 months. The average length of the surgical procedure was 2.5 hours. Almost all of the patients passed stool and flatus within 24 hours of surgery. The average time for discharge after surgery was 3.7 days. All 80 patients are currently alive and well. Most of the children are too young to evaluate for fecal continence, but 18 of the older children have been reported to be continent.

Conclusion

Laparoscopic-assisted colon pull-through appears to reduce perioperative complications and postoperative recovery time dramatically. The technique is quickly learned and has been performed in multiple centers with consistently good results.

In 1948, Swenson reported his early experience with definitive surgical therapy for Hirschsprung’s disease (HD). 1 The procedure he employed included a sphincter-sparing abdominoperineal resection of the aganglionic rectosigmoid colon, followed by mobilization of a distal ganglionated colon pedicle that was approximated to the anorectum 2 to 3 cm above the dentate line. Since Swenson’s initial report, open surgical correction of HD has traditionally been performed in two or three stages. 2–4 A leveling colostomy is formed at diagnosis for decompression of the dilated bowel proximal to the aganglionic segment. After an appropriate time interval, a colon pull-through is performed with either simultaneous or subsequent ostomy closure.

During the past 20 years, there have been sporadic reports of satisfactory results after a single-stage primary pull-through for HD. 5,6 One-stage pull-through has been noted to be particularly beneficial in infants younger than 3 months of age. Recent advances in minimal-access surgery have led to the successful application of laparoscopic-assisted techniques for the surgical management of diseases of the colon. This paper reports the early clinical outcomes after a one-stage laparoscopic-assisted endorectal pull-through.

METHODS

All patients with a potential diagnosis of HD were assessed with a barium enema and rectal biopsies. Only infants and children with biopsy-documented distal colon aganglionosis were considered candidates for laparoscopic-assisted endorectal colon pull-through. Patients with severe enterocolitis or patients in poor general health were excluded as candidates for primary laparoscopic pull-through.

Frequent digital dilatation of the anorectum and/or irrigation of the colon with saline through a rectal tube usually provided excellent decompression of the intestine. Although most of the patients underwent their definitive surgical procedure immediately after the diagnosis of HD was confirmed, some patients were sent home on a regimen of daily colonic irrigations and admitted later for the surgical procedure.

Preparation for surgery included the administration of preoperative oral and intravenous antibiotics according to the usual practices of the surgeon. Infants were positioned transversely on the operating table, with the surgeon performing the laparoscopic portion of the procedure standing above the patient’s head. Older children were placed in stirrups, with the surgeon standing to the right side of the patient. Infants were not catheterized; the bladder was emptied using Credé’s maneuver. The patient was prepared and draped from the nipples to the toes. Pneumoperitoneum was secured using a Varess needle inserted through the umbilicus. Pressures of 12 cm H2O were well tolerated in all age groups. Modest hyperventilation prevented hypercarbia. A 4-mm 30° scope was used in infants and a 5-mm 30° scope in older children. The trocar site for the scope was placed just below the liver edge and to the right of the falciform ligament. Trocars were also placed in the right lower quadrant and left upper quadrant of the abdomen. These ports were 4 or 5 mm in diameter, depending on the size of the patient. A suprapubic trocar was used in some patients to provide retraction of pelvic structures and to hold the colon in traction during laparoscopic dissection of the rectum (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Position of trocar sites for laparoscopic pull-through.

After placement of the trocars, the transition zone was identified visually. A seromuscular biopsy was obtained with laparoscopic scissors for histologic leveling. A window was made between the colon and the superior rectal vessels. These vessels were divided with monopolar or bipolar cautery in infants or the ultrasonic scalpel in older children. The aganglionic segment of intraabdominal colon was then dissected circumferentially, keeping close to the rectum. The avascular plane behind the rectum was dissected bluntly. The rectum was dissected anteriorly 1 to 2 cm below the peritoneal reflection. The anterior and posterior planes were then joined, hugging the rectal wall.

Once the pathologist had confirmed the presence of ganglion cells proximal to the aganglionic segment, dissection of the colon pedicle began. The mesenteric dissection was extended proximally, carefully preserving the marginal artery. In patients with a low rectosigmoid transition zone, very little dissection was needed. In other patients, only the sigmoid mesocolon was mobilized. In a few patients, the lateral fusion fascia was divided up to the splenic flexure and the colon mesentery was mobilized while carefully preserving the marginal artery. This mobilization was carried proximally until the colon pedicle was long enough to reach deep into the pelvis without tension (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Mesenteric dissection for mobilization of the colon pedicle.

Once the endoscopic dissection of the colon and rectum had been completed, the perineal dissection was started by placing six to eight traction sutures to evert the anus and expose the rectum. A circular incision was made in the rectal mucosa 10 to 20 mm above the dentate line (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Transanal dissection of rectal mucosa begins 10 to 20 mm above the dentate line.

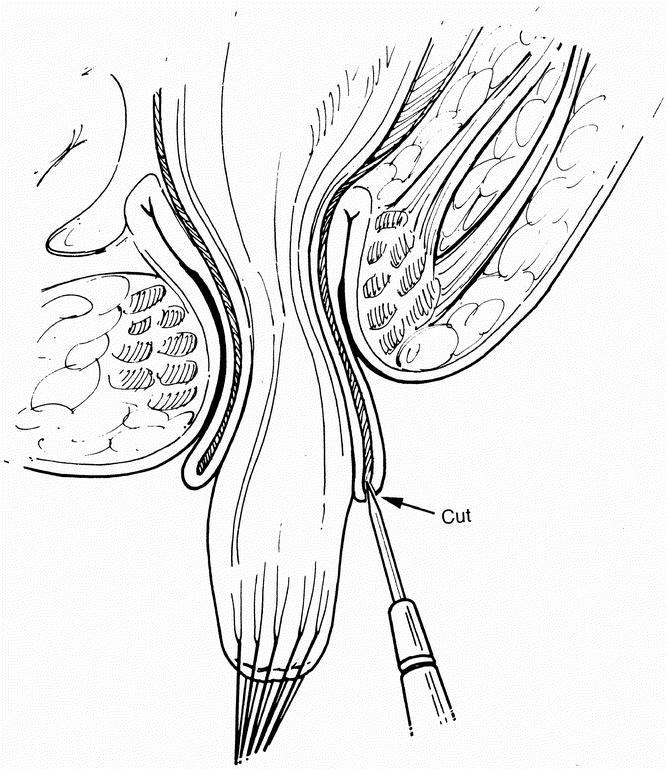

Fine silk traction sutures were placed in the proximal lip of the exposed mucosal edge, creating a circumferential submucosal plane, which was further developed using blunt and sharp dissection. Larger vessels were cauterized during this dissection. The plane was extended proximally until the colorectum turned inside-out, indicating that the transanal dissection had advanced to the level of the internal perirectal dissection. The rectal sleeve was opened posteriorly, joining the submucosal plane with the extramural dissection from above (Fig. 4). The muscle sleeve was subsequently divided, joining the two dissection planes circumferentially. If the transanal submucosal dissection had not proceeded up to the laparoscopic perirectal dissection, the submucosal dissection was extended several centimeters upward, and another attempt was made to join the two planes. Once the perineal and laparoscopic dissection planes had been joined circumferentially, the resulting short muscular rectal cuff was usually divided posteriorly to allow more room for the developing neorectal reservoir. Division of the muscular cuff was optional, subject to the preference of the surgeon. The rectum and colon were pulled down through the anus in continuity until the ganglionated bowel presented in the anus. The point of seromuscular colon biopsy was pulled beyond the point of intended bowel transection. The colon was transected and a circumferential one-layer anastomosis between the neorectum and anus was fashioned using absorbable sutures (Fig. 5).

Figure 4. Transanal joining of planes posteriorly after prolapse of rectosigmoid colon.

Figure 5. The ganglionated colon is pulled down to the anus and secured with interrupted sutures.

Pneumoperitoneum was reintroduced and the colon pedicle was inspected for internal herniation or twisting. The pelvis was reperitonealized with interrupted sutures when indicated. The port sites were closed with fascial sutures and skin strips.

After surgery, patients remained on nasogastric decompression for 12 hours. A diet was introduced when there was evidence of bowel function. The patient was discharged when tolerating an oral diet. Rectal examination was performed 2 to 3 weeks after surgery. A parent was taught to perform routine daily anorectal dilatation in approximately half of the patients, according to the preference of the surgeon.

The clinical outcomes at each of the contributing centers were tabulated and compiled for this report.

RESULTS

Laparoscopic-assisted colon pull-through was performed on 80 patients at six participating pediatric surgery centers over a 5-year period (Table 1). Sixty-nine (86%) of the 80 patients had a transition zone in the rectum or sigmoid colon. The remaining 11 patients had a transition zone proximal to the sigmoid colon; one of these patients had total colon aganglionosis. Seventy (87.5%) of the children were younger than 6 months of age at the time of the pull-through procedure. Operative time averaged 147 minutes. Blood loss was <10 cc per patient; only one patient was given a blood transfusion.

Table 1. Participating Pediatric Surgery Centers

The early postoperative course after laparoscopic-assisted colon pull-through was characterized by rapid recovery. Only six patients did not have a bowel movement within 24 hours of the procedure. Average time to ad libitum feedings was 28 hours. The mean time to discharge was 3.7 days.

Complications are listed in Table 2. There were no instances of anastomotic stricture, postoperative bowel obstruction, wound infection, prolonged ileus, pelvic or intraabdominal abscesses, or wound dehiscence. Ten (12.5%) of the 80 patients were readmitted to the hospital for complications. Four of these 10 patients required postoperative diversion of the gastrointestinal tract. One patient underwent diversion for severe enterocolitis and two for an anastomotic leak. The fourth patient underwent diversion for a congenital syndrome.

Table 2. Early Complications After Laparoscopic-Assisted Endorectal Pull-Through (n = 80)

Approximately half of the 80 patients had routine anorectal dilatations, according to the preference of the surgeon. Only one patient required forceful dilatation for chronic constipation secondary to a tight internal sphincter. This patient had been in the group that had daily dilatation. Long-term compliance of the anorectum did not seem to be affected by routine, daily anorectal dilatation.

Most of the patients had frequent stools immediately after their pull-through procedure, apparently because of the small size of the neorectal reservoir, but only six patients had frequent stools for >6 months. Two of these six patients had lactose intolerance; their diarrhea resolved with lactose restriction. Two of the remaining four patients with chronic diarrhea did not form a rectal reservoir for >18 months after pull-through; they both responded to a secondary Duhamel procedure to enlarge their rectal reservoir. Two of the six patients responded to a constipating diet and antidiarrheal agents.

All 80 patients are alive and well at present. Eighteen of the older patients are reported to have satisfactory continence. Another two patients have had overflow incontinence, which responded well to the administration of cisapride. The other patients are either too young to evaluate for continence or have significant neurologic impairment.

DISCUSSION

The features that distinguish this minimal-access endorectal technique from the traditional open pull-through procedures include the following:

• The colon pedicle is mobilized laparoscopically, minimizing peritoneal trauma.

• The intraabdominal colon remains intact, avoiding bacterial contamination of the peritoneal cavity.

• The endorectal dissection is performed transanally, minimizing peritoneal trauma.

Because many of the benefits of the procedure can be attained by transanal dissection alone, the possibility of performing the pull-through procedure without laparoscopic assistance seems attractive. We, as well as others, have performed the colon pull-through transanally without laparoscopic assistance. There are, however, significant benefits realized by performing the laparoscopic dissection. Most important is the ability to verify the presence of ganglion cells in the proximal colon pedicle by seromuscular biopsy before proceeding with the irreversible step of endorectal dissection. Laparoscopic devascularization and mobilization of the intraabdominal aganglionic segment of rectosigmoid colon increases the mobility of the rectum and makes the end point of the endorectal dissection more definitive. Because the endorectal dissection is facilitated by laparoscopic mobilization of the rectosigmoid colon, there is less potential for overdilating the internal anal sphincter and thereby weakening the patient’s fecal continence mechanism during the transanal dissection. The laparoscopic approach also provides greater versatility in fashioning the ganglionated pedicle proximal to the aganglionic colon and allows for completion of the pull-through in patients with longer aganglionic segments.

Laparoscopic-assisted colon pull-through appears to reduce the postoperative recovery time and perioperative complications dramatically when compared with open pull-through procedures. Most of the patients were fed on the first postoperative day and discharged on the second or third postoperative day. Six of the 10 patients who had to be readmitted to the hospital were admitted for ≤3 days and did not require additional admissions or surgical procedures. Only 4 of the 80 patients required a secondary ostomy. Two of these four patients had an anastomotic leak and one had a serious congenital abnormality. Better preoperative screening and a more precise surgical technique may have avoided these mishaps. Laparoscopic-assisted endorectal pull-through sets a new standard for minimizing perioperative complications and shortening postoperative recovery in patients having corrective surgery for HD. 7–9 Long-term assessment of fecal continence will be necessary to determine the overall utility of this procedure.

Discussion

Dr. George W. (Whit) Holcomb, III (Nashville, Tennessee): I think it is important that the authors appreciate the fact that Keith has developed the idea and the technique for this operative approach. Just as the other operations have been named for their inventors, such as the Duhamel procedure, the Soave procedure, and the Swenson procedure, I believe that the laparoscopic assisted pull-through will soon be known as the Georgeson procedure. Keith should be applauded for his concern that the operation is performed safely and appropriately.

I agree that this approach is safe and effective. At this time I would take issue with the authors to anoint this technique as the gold standard. From my perspective, the gold standard should indicate the optimal results, not necessarily the optimal technique. Therefore, in follow-up of these patients it is important to assess anal continence and function, which will require several more years of evaluation.

I’d like to ask Keith four questions.

The average day of discharge was 3.7 days. Yet in the manuscript it says that most patients are discharged on the first or second, or some on the third day. How do you account for this difference in the average length of hospitalization being 3.7 days? Could you elaborate on what kept some patients in the hospital for a longer time?

Second, some patients had immediate surgery after their diagnosis was made, and some were discharged home with daily colonic irrigations and then returned for their operation. Were there any differences in results according to this difference in management?

Third, 10 patients, which was 12% of the series, required rehospitalization, and 4 of these required post–pull-through diverting colostomies. What have you and your colleagues learned from these patients?

Would you elaborate on which patients should have an initial colostomy rather than the single-stage operative procedure?

Dr. H. Biemann Otherson, Jr. (Charleston, South Carolina): I have three comments and one question.

Pediatric surgeons as a group are very conservative individuals, and they have been slow to accept minimally invasive techniques. We have seen other procedures, though, such as laparoscopic cholecystectomy, rapidly become the gold standard. I would agree that before this becomes the gold standard, that we should watch out for the final results. I agree that we have to wait. The caveat is that we will have to wait and see whether all of these patients will develop continence, and it will be even longer to determine whether they will have ejaculatory function as a male.

However, the fact that this is 80 patients in a multiinstitutional study means that it may be becoming a gold standard. Maybe it’s silver already.

Second, Dr. Georgeson has devised this procedure, and he is to be complimented as a teacher, because he has been able take this to other institutions. They have been able to duplicate his results after he has taught them the technique. So I think that that is another area to congratulate him.

The third comment is similar to that of Dr. Holcomb, and that is that this is primarily a minimally invasive Soave-type of operation, but there are some elements of the Swenson procedure. And I agree that it will probably eventually be called the Georgeson modification or Georgeson procedure.

My question is that one of our patients was an older child who was diagnosed late. When this procedure was performed by one of my associates, the bowel was very dilated and made the operation difficult, even though it had been cleaned out, and it led to serious complications. Do you think this procedure should be limited to newborns and infants who do not have dilated bowel?

Dr. Keith E. Georgeson (Closing Discussion): I thank both of you for your comments. First of all, I would have no problem scratching the latter part of this title off, that is, I don’t believe it needs to be considered a gold standard yet. On the other hand, I do think that the morbidity in the early postoperative period is much less, and for that reason, at least needs to be considered as an operation that is worth doing.

In terms of the day of discharge, when we first started doing this operation, we held the patients in hospital for 7 days, so that a lot of our early patients were in hospital for that period of time because we were waiting for the other shoe to drop. And when it finally didn’t drop, we let them go home. And as time went on, we kept shortening that period. And as I began sharing the operation with some of my friends, some of them are a lot bolder than I am. And one of my friends, who happens to be here, operated on a doctor’s child and let that child go home the next day. So it became apparent to me that in many cases we can discharge these patients earlier.

I think a better statement would be that at the present time most of our patients go home on the second or third day.

As far as the timing of surgery, as far as I know, there were no benefits to decompressing the patients and sending them home. Now perhaps you could argue that this gives the mother and child a chance to bond. But many of our children are not brand-new borns. They have been home for a short period of time, and so that bonding has already occurred. But otherwise, I don’t know of any advantages or disadvantages. The one theoretical disadvantage that I have seen has been in patients that people were saving for me. In fact, one of those happened in Charleston where they were saving the patient by using saline enemas at home, and the patient developed severe enterocolitis. So that my predisposition would be to operate sooner rather than later.

Who should have a colostomy? Well, I think first and foremost, we are surgeons. And anytime you have a patient whose general condition is unstable or could easily become unstable, I think it is unwise to do a major operative procedure. Otherwise, I don’t think colostomy is that helpful.

Regarding Dr. Otherson’s question about the older patient, it seems to me that in the older patients that I have done, these are patients that seem to be immune to enterocolitis, and that is why they haven’t been discovered earlier. And for that reason, they seem to do very well. I don’t know what happened in the particular case you described, but I have not seen enterocolitis in patients who have been operated later. But I think that some people might be uncomfortable with pulling that very dilated colon down, and, if so, it would be perfectly fair to do a colostomy before you do the pull-through.

Footnotes

Correspondence: Keith E. Georgeson, MD, The Children’s Hospital of Alabama, 1600 7th Avenue South, ACC 300, Birmingham, AL 35233.

Presented at the 110th Annual Meeting of the Southern Surgical Association, December 6–9, 1998, The Breakers, West Palm Beach, Florida.

Accepted for publication December 1998.

References

- 1.Swenson O, Bill AH. Resection of rectum and rectosigmoid with preservation of the sphincter for benign spastic lesions producing megacolon. Surgery 1948; 24: 212–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kleinhaus S, Biley SJ, Sheran M, et al. Hirschsprung’s disease: a survey of the number of the surgical section of the American Academy of Pediatrics. J Pediatr Surg 1979; 14 (5): 588–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harrison MW, Deitz DM, Campbell Jr, et al. Diagnosis and management of Hirschsprung’s disease: a 25-year perspective. Am J Surg 1986; 152: 46–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nixon HH. Hirschsprung’s disease: progress in management and diagnosis. World J Surg 1985; 9: 189–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carassonne M, Morrison-Lacombe G, Le Tourneau JN. Primary corrective operation without decompression in infants less than three months of age with Hirschsprung’s disease. J Pediatr Surg 1982; 17: 241–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Georgeson KE, Fuenfer MM, Hardin WD. Primary laparoscopic pull-through for Hirschsprung’s disease in infants and children. J Pediatr Surg 1995; 30: 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mishalany HG, Woolley MM. Postoperative functional and manometric evaluation of patients with Hirschsprung’s disease. J Pediatr Surg 1987; 22: 443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rescorla FJ, Morrison AM, Engles D, West KW, Gorsfeld JL. Hirschsprung’s disease: evaluation of mortality and long-term function in 260 cases. Arch Surg 1992; 127: 934–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Teitelbaum DH, Coran AG, Weitzman JJ, et al. Hirschsprung’s disease and related neuromuscular disorders of the intestine. In: O’Neill JA, Rowe MI, Grosfeld JL, Fonkalsrud EW, Coran AG, eds. Pediatric Surgery. 5th ed, vol 2. St. Louis: Mosby-Year Book; 1998: 1381–1424.