Abstract

The adoptive transfer of activated CD4+α/β T cell blasts from the spleens of immunocompetent C.B-17+/+ or BALB/cdm2 mice into C.B-17scid/scid (scid) mice induces a colitis in the scid recipient within 8 weeks, which progresses to severe disease within 16 weeks. T cells isolated from recipient colon show a Th1 cytokine phenotype. We have examined the relationship between the phenotype of the cellular infiltrate and the transcription and translation of the proinflammatory cytokine TNF-α. The techniques of double indirect immunohistology and in situ hybridization using digoxigenin-labelled riboprobes were used. The prominent myeloid cell infiltrate in diseased tissues comprised F4/80+, Mac-l+ macrophages, neutrophils, dendritic cells and activated macrophages. TNF-α transcription and translation were associated with activated macrophages in the lamina propria. Activated macrophages transcribing and translating TNF-α were clustered in areas of tissue destruction. Crypt epithelium of inflamed tissues transcribed TNF-α at a very early stage of the disease process, but translation of TNF-α protein could only be found in advanced epithelial dysplasia. This indicates differential post-transcriptional control of TNF-α in activated macrophages and the epithelium.

Keywords: tumour necrosis factor-alpha, transcription, translation, scid colitis, macrophages

INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is the collective term given to two inflammatory intestinal disorders of currently unknown primary cause: Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). The inflammation in IBD may be due to a dysregulated immune response to an unidentified pathogen or to a commensal of the normal gut flora. The initiating stimulus is unknown and the nature of the aberrant mucosal immune response is poorly understood.

In recent years, mice with targeted deletions of cytokine genes [1,2], or other immune response-related genes [3,4], and immunodeficient mice reconstituted with immunocompetent histocompatible T cells [5–10], have been extensively studied as animal models of IBD.

In one such model, transplantation of low numbers of peripheral CD4+CD8− T cells from immunocompetent mice into congenic severe combined immunodeficient (scid) mice causes an IBD affecting the large intestine [11,12]. Whether isolated peripheral CD4+ cells [12] or whole tissue from the gut wall [9] is transplanted the result is the same—engraftment of donor CD3+CD4+ TCR αβ+ cells into the gut-associated lymphoid tissue of the homozygous scid recipient host and clinical symptoms of IBD within 3–6 months of transfer [12].

The engrafted T cells express the CD4+CD45RBlo CD44hi CD2hi CD28hi CD49dhiCD62Llo phenotype of mucosa-seeking memory cells [9,12], and home to mucosal sites where they become activated (CD69hi). The cells have been shown to be phenotypically Th1-like by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis [13], by permeabilized FACS analysis [14] and functionally Th1-like in that re-isolated cells secrete interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) and IL-2 on CD3 ligation [10]. The Th1-mediated inflammatory response is reversed by administration of rIL-10 [15]. IL-10 is a potent suppresser of macrophage activation [16] and thus may exert its anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting macrophage cytokine release. Alternatively, IL-10 has been shown to induce proliferation of a regulatory T cell clone (termed Tr1) which is capable of preventing colitis in the CD45RBhi model when co-transferred with CD45RBhi T cells [17]. Thus Tr1 cells functionally resemble the regulatory T cells of the CD45RBlo population, which is able to prevent colitis by an IL-10-dependent [18] and transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β)-dependent mechanism [19].

TNF-α and IFN-γ are important mediators of disease in the scid mouse model of colitis [15]. However, the role of TNF-α in human IBD has proved controversial. Many studies have reported elevated levels of TNF-α in the serum, stool and lamina propria of patients with active CD and UC [20–22], but other groups have been unable to find any increase in TNF-α mRNA or protein in IBD [23,24]. Therapeutic trials of the TNF-α inhibitor oxpentifylline have reported both positive and negative results [25–27], again leading to controversy as to the role of TNF-α. However, recent human trials using the anti-TNF-α antibodies CDP-571 [28] and Infliximab (cA2) [29–31] have produced promising results. Considerable reductions in the CD activity index (CDAI) were observed and in some cases to below a level indicating remission, although long-term efficacy and side effects, e.g. responses to the chimeric antibodies, have yet to be established. These results support the view that TNF-α is a major factor in perpetuating the inflammation of IBD, although the cell types secreting TNF-α, and the kinetics and controls of TNF-α transcription and translation during disease pathogenesis remain unknown.

In many studies of animal models, the assessment of TNF-α involvement is based on the analysis of isolated cells. In this study we have characterized the transcription and synthesis of TNF-α by specific cell types within the inflammatory lesions found in the transplanted scid mouse model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents for immunohistology

Monoclonal rat anti-mouse CD3 (clone KT3), rat anti-mouse CD11b (clone M1/70) and rat anti-mouse F4/80 antigen were all purchased from Serotec Ltd (Oxford, UK). Monoclonal rat anti-mouse TNF-α (clone XT3) and biotin-conjugated goat anti-rat IgG were purchased from Harlan Sera-lab (Loughborough, UK). Clone 158.2, rat anti-mouse activated macrophage, was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD). The streptavidin-biotin horseradish peroxidase amplification kit (ABC kit) was purchased from Dako A/S (Glostrup, Denmark).

Plasmid

The TNF-α-containing plasmid (a gift of Dr B. Brody, University of Alabama at Birmingham, AL) contained a murine cDNA construct of 1110 bp cloned into the PstI-EcoRI sites of pGEM-3. Both sense and antisense RNA transcripts were of approx. 1100 bp. The cDNA construct was sequenced using the Sanger method of dideoxy termination sequencing [32,33], before first use to confirm identity and determine orientation. The plasmid was stored in Escherichia coli-XL-1 blue in glycerol at −70°C.

Reagents for in situ hybridization

The plasmid preparation kit (Qiaprep mini-prep) was purchased from Qiagen (Crawley, UK). Restriction endonucleases (HindIII and SalI), digoxigenin (DIG)-conjugated RNA labelling NTP mix, RNA polymerases (T7 and SP6), RNase A and anti-DIG alkaline phosphatase-conjugated Fab fragments (α-DIG-AP) were all purchased from Boehringer Mannheim (Lewes, UK). A DNA recovery/purification kit, all electrophoresis equipment, the Omnislide thermal cycler and slide wash module were purchased from Hybaid (Teddington, UK). The slide clearing solution (Histoclear) and non-xylene mountant (Histomount) were purchased from National Diagnostics (Hull, UK) and the Gene Frame II sample incubation chambers were from Advanced Biotechnologies (Epsom, UK). All other reagents were purchased from Sigma (Poole, UK) unless stated otherwise.

Mice

C.B-17+/+ mice (H-2d,Ld+), C.B-17scid/scid mice (H-2d,Ld+) and BALB/cdm2 (H-2d,Ld−), were bred and maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions in the animal colony of the University of Ulm, Germany. Mice were routinely tested for mouse hepatitis virus to ensure its absence. We investigated four C.B-17+/+ controls, two non-transplanted scid mice and 20 transplanted scid mice with colitis.

Transplantation

C.B-17scid/scid mice were transplanted with immunocompetent CD4+ T cells in accordance with a previous protocol [12]. Briefly, spleens were taken from immunocompetent C.B-17+/+ or BALB/cdm2 donor mice and a single-cell suspension was aseptically prepared, and the cells were then cultured for 3 days with concanavalin A (Con A). On day 3, the cells were separated over Ficoll to remove dead cells and cultured for a further 2 days in the presence of Con A alone, or Con A and cytokines and antibodies favouring Th1 development. On day 5, cells were again separated over Ficoll and the desired cell population (unfractionated CD4+ or CD4+ CD45RBhi) was isolated by flow cytometry and transplanted by i.p. injection into C.B-17scid/scid recipients.

Creation of riboprobes

The plasmid containing TNF-α cDNA was extracted from E. coli-XL-1 blue cells and linearized with the appropriate restriction enzyme. A 40-mm NTP mix (each NTP 10 mm) containing 3.5 mm UTP linked via a spacer arm to DIG was the labelling substrate. After electrophoresis and gel purification of the linear cDNA, sense and antisense DIG-labelled riboprobes were transcribed using SP6 or T7 RNA polymerase as appropriate. For verification of size, label incorporation and quantity, the RNA probes were electrophoresed and blotted onto nylon membrane, then probed with α-DIG-AP and the AP substrate, nitro blue tetrazolium/5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-phosphate (BCIP/NBT). Probes were aliquoted at a dilution of 1:5 in hybridization buffer; 100 mm Tris, 600 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 0.5 mg/ml tRNA, 1 × Denhart's medium (a non-specific blocking agent), 10% dextran sulphate, 50% formamide for storage at −20°C.

Preparation of tissue samples

At necropsy, intestinal tissue samples were collected and immediately embedded in OCT (Tissue-Tek; R. A. Lamb, London, UK) and frozen in liquid nitrogen-cooled isopentane. Tissues were stored at −70°C.

Day 1

Serial cryostat sections were cut at 10 μm (Bright Instruments, Huntingdon, UK) and thaw-mounted alternately onto 3-aminopropyltriethoxy-silane or chrome-alum-gelatin-coated glass slides for in situ hybridization and immunohistology, respectively.

The sections were then air-dried for at least 1 h.

Immunohistology

After air-drying, the sections were fixed in acetone at 4°C for 10 min, then air-dried for 15 min. After blocking with 10% normal goat serum/PBS for 30 min, the primary antibody was applied at an appropriate concentration and incubated overnight at 4°C in a humidity chamber.

Day 2

The slides were washed several times in PBS and the secondary antibody (biotin-conjugated goat anti-rat IgG) was applied. Detection utilized the ABC amplification kit and either the peroxidase chromagen, diaminobenzidine (DAB, brown) for single antibody detection, or the chromagens 4-chloro-napthol (4-CN, blue) and 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole (AEC, red), when serial detection by two antibodies was required. Slides developed with DAB were counterstained with Mayers’ haematoxylin, cleared through alcohol and Histoclear and mounted using DPX. Slides developed with AEC and 4-CN were mounted with Aquaperm, an aqueous mountant purchased from Life Sciences International (Basingstoke, UK).

In situ hybridization

All instruments were treated with 0.3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 min and rinsed with DEPC-treated milliQ water before use. All buffers, water and solutions were treated with DEPC and autoclaved before use.

After air drying the sections were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C for 10 min. The sections were washed three times in PBS, permeabilized in 0.4% Triton X-100/PBS for 5 min, washed again in PBS and acetylated for 10 min in 0.25% acetic anhydride/0.1 m triethanolamine (pH 8.0) to reduce non-specific electrostatic binding. Sections were then dehydrated through ethanol (50, 70, 90, 100%), air-dried and a Gene frame II incubation chamber was applied to each slide prior to hybridization. As a negative control, one section from each series was incubated in 5 μg/ml RNase A for 20 min at 37°C prior to acetylation.

For hybridization, a sufficient volume of the relevant sense and anti-sense riboprobes was diluted in hybridization buffer (final dilution of 1:200), heated to 65°C for 10 min, cooled on ice and applied onto the slides. Coverslips were applied without introducing air bubbles to seal the incubation chamber. The slides were then incubated on the slide thermal cycler for 5 min at 80°C (to denature the riboprobe), cooled to 55°C and incubated overnight.

Day 2

Coverslips were carefully removed and the sections were desalted by incubating in 2 ×, 1 ×, 0.5 × and 0.2 × SSC for10 min each. Slides were stringently washed in 0.2 × SSC at 60°C for 1 h to remove any probe non-specifically bound to tissue constituents. The RNA was cleaved from non-specific DNA–RNA hybrids, and single-stranded RNA was digested byincubating with 5 μg/ml RNase A in Tris–EDTA pH 8.0 and 150 mm NaCl at 37°C for 20 min. After extensive washing in PBS, the samples were blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 40 min, and incubated with 7.5 U/ml α-DIG-AP for 90–120 min in a humidity chamber at room temperature. The slides were extensively washed and mRNA was visualized using BCIP/NBT. When an intense precipitate was observed, the sections were washed in distilled water to halt the reaction and counterstained with nuclear fast red. The slides were cleared through alcohol and Histoclear and mounted using Histomount.

TNF-α control experiment

A mouse T cell clone (UZ,314; Dr U. Steinhoff, Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology, Berlin, Germany) secreting high levels of TNF-α in response to heat shock protein was used as a positive control for TNF-αin situ hybridization.

Scoring and statistical analysis

Mice were scored for histological disease in a blinded fashion by an independent observer. The criteria on which the disease score was assessed included: degree of total tissue hypertrophy; crypt hyperplasia; T cell infiltration; crypt branching; crypt abscesses; and ulceration. Each parameter was scored subjectively from 0 (absent) to 3 (severe) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Histological disease scores of all mice investigated

TNF-α involvement was assessed by observing the distribution of mRNA and protein in the epithelium, mucosal lamina propria and submucosa using a subjective score from 0 (absent) to 3 (extensive). The involvement and distribution of T cells and macrophages in these three compartments were assessed in the same way (Table 2). The greater disease severity of some mice was reflected by the fact that lamina propria scores became maximal and submucosal involvement became evident.

Table 2.

Scores of TNF-α mRNA, TNF-α protein, activated macrophage and CD3+ cell involvement in all mice investigated

Statistical analysis was performed using Systat software. Cluster analysis was performed using several methods and no clustering of cases was identified. Correlations between TNF-α message or protein and infiltration by T cells or macrophages (Table 2), and between TNF-α message or protein and each of the histological disease parameters (Table 1), were assessed by multiple regression analysis using all mice and are indicated at the appropriate points in the text. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Cellular infiltration

Infiltration of colonic tissues by T cells and myeloid cells likely to be involved in the production of TNF-α was assessed by immunohistochemistry. In non-transplanted scid mice, as expected, there was no evidence of CD3+ T cells or activated macrophages. However, large numbers of CD11b+F4/80+ myeloid cells were present throughout the lamina propria, together with low numbers of CD11b+ single-positive cells (Fig. 1a), and this appearance did not differ from C.B-17+/+ controls (not shown). In C.B-17+/+ colon, CD3+ cells were scattered throughout the lamina propria and activated macrophages were present, albeit in extremely low numbers.

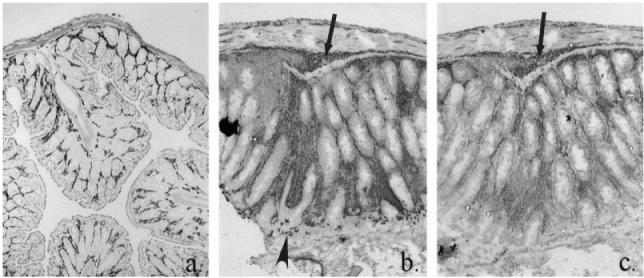

Fig. 1.

Immunohistochemical localization of myeloid cells in the normal scid mouse colon (a) and in the inflamed colon of a scid mouse transplanted with CD4+ T cells (b,c). Stained for CD11b, MoAb M1/70 and F4/80, MoAb C1:A3-1 (a); CD11b only (b); and F4/80 only (c). In colitis, tissue hypertrophy and increased infiltration by myeloid cells: arrow, infiltration of submucosa; arrowhead, CD11b+ neutrophils crossing epithelium. (All ×10 objective.)

In the transplanted scid mice, colitis resulted in pronounced crypt hyperplasia and tissue hypertrophy (compare Fig. 1b,c and Fig. 1a). The expanded lamina propria was infiltrated by greatly increased numbers of CD11b+F4/80+ macrophages (Fig. 1b,c), with extension of this infiltrate into the submucosa, but there was also extensive infiltration by CD11b+F4/80− neutrophils which in severe disease were frequently observed transiting the surface epithelium (Fig. 1b). A feature of the myeloid cell expansion in colitis was the inclusion of large numbers of activated macrophages in the infiltrate. By double indirect immunohistochemistry, activated macrophages did not express F4/80 antigen, confirming the loss of this macrophage differentiation marker on activation [34–37]. In less severe disease, clusters of activated macrophages were confined to the lamina propria immediately subjacent to the luminal surface epithelium. In more severe disease, activated macrophages were present throughout the entire lamina propria and submucosa (Fig. 2a). Activated macrophages were either dispersed together with approximately equal numbers of CD3+ T cells, or as foci in which activated macrophages dominated, with very few CD3+ cells present (Fig. 2). Areas in which CD3+ cells dominated were also seen (Fig. 2). Presence of activated macrophages in a section correlated with the presence of CD3+ cells (P < 0.001, Table 2), indicating the reliance of macrophage activation on the presence of activated T cells. Sheaths of activated macrophages surrounding crypt abscesses and crypts undergoing epithelial degradation were a common finding in severely diseased mice (Fig. 5c).

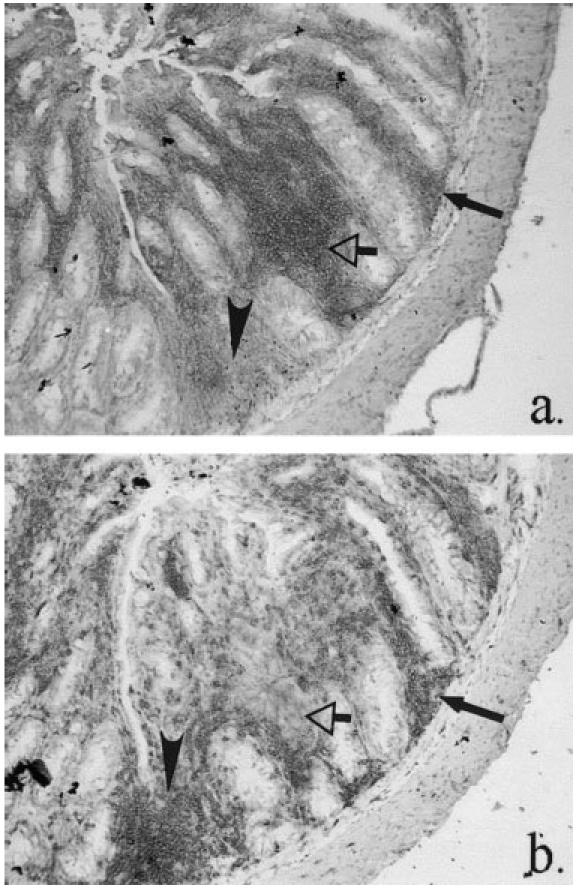

Fig. 2.

Scid mouse colitis, demonstrating distribution of (a) activated macrophages, MoAb 158.2 and (b) CD3+ T cells, MoAb KT3. Activated macrophages are present with equivalent numbers of T cells (closed arrows), or as foci without T cells (open arrows). CD3+-dominant foci can also be seen (arrowheads). (Both ×10 objective.)

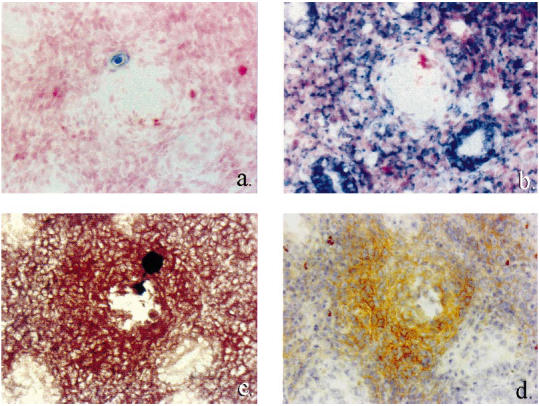

Fig. 5.

Correlation of TNF-α transcription and protein synthesis with presence of activated macrophages in a region of crypt destruction in scid mouse colitis. Serial sections: (a) TNF-α sense riboprobe, in situ hybridization (ISH); (b) TNF-α antisense riboprobe, ISH; (c) activated macrophages, MoAb 158.2, immunohistochemistry; (d) TNF-α protein, MoAb XT3, immunohistochemistry. Coincidence of TNF-α mRNA and protein and activated macrophages in pericryptal sheath. (All ×40 objective.)

TNF-a transcription

In situ hybridization studies showed that in non-transplanted scid colon, TNF-α was not transcribed by lamina propria cells. However, crypt epithelial cells, to approx. 50% of the crypt axis, did transcribe TNF-α (Fig. 3a), whereas in C.B-17+/+ mice no epithelial transcription of TNF-α was observed (Fig. 3b). As with non-transplanted scid mice, there was no lamina propria transcription of TNF-α, but within mucosal lymphoid follicles many TNF-α-transcribing cells were observed (not shown).

Fig. 3.

Transcription of TNF-α in colonic tissues of normal scid mouse (a) (×10 objective) and C.B-17+/+ mouse (b) (×20 objective), by in situ hybridization using TNF-α antisense riboprobe. Positive staining in lower crypt epithelium of scid only.

In mice with mild colitis, foci of cells transcribing TNF-α mRNA were observed in the superficial lamina propria, whereas in severe colitis transcription was evident throughout the entire lamina propria. In general, transcription correlated with activated macrophage accumulation (Fig. 4). Thus, lamina propria transcription correlated with lamina propria-activated macrophage infiltration (P < 0.001, Table 2), and submucosal transcription correlated with submucosal activated macrophage infiltration (P < 0.001, Table 2). In the vicinity of crypt abscesses, lamina propria transcription of TNF-α clearly coincided with the clustering of activated macrophages in pericryptal sheaths (Fig. 5b,c).

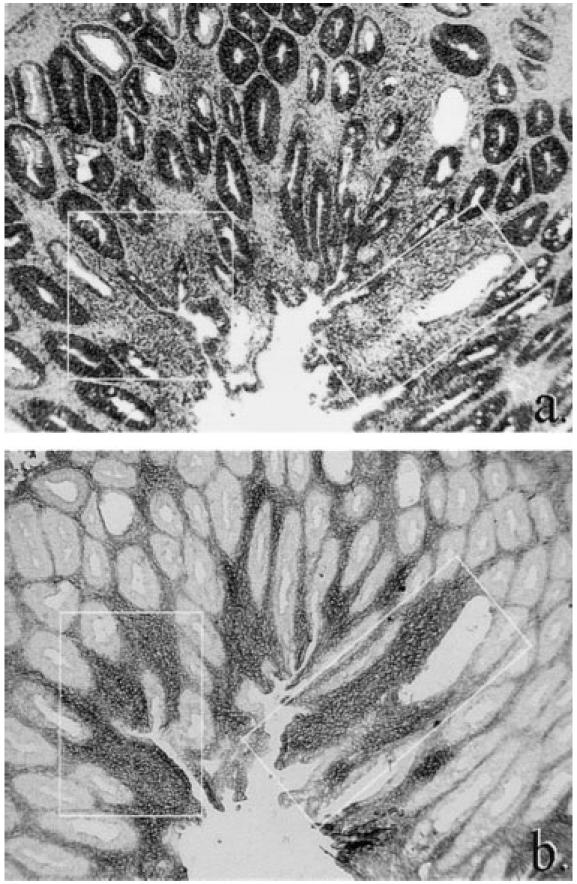

Fig. 4.

Correlation of TNF-α mRNA in scid colitis by in situ hybridization (a) with distribution of activated macrophages (MoAb 158.2) by immunohistochemistry (b). Note especially corresponding areas of transcription and activated macrophage infiltration highlighted by insets (slight differences between inset size and tissue included are caused by serial sectioning and differential tissue shrinkage artefact using the two methods). (Both ×10 objective.)

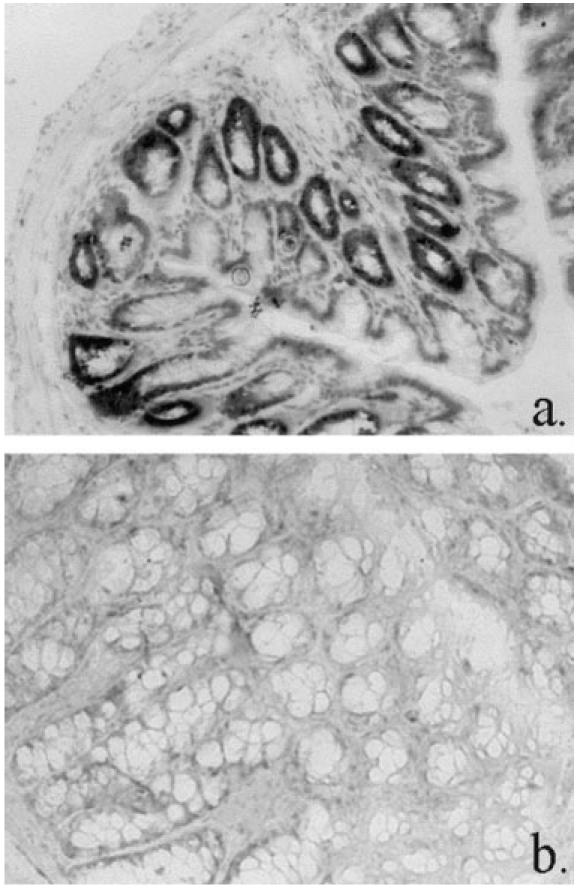

Transcription in the epithelium in colitis was extended compared with non-transplanted scid mice, to the necks of crypts in less severely diseased mice, and throughout the entire epithelium, including the luminal surface epithelium, in severely diseased mice (Fig. 4). However, in regions of epithelial destruction, there was less hybridization to TNF-α mRNA than in the relatively normal epithelium of adjacent crypts (Fig. 5b, Fig. 6a).

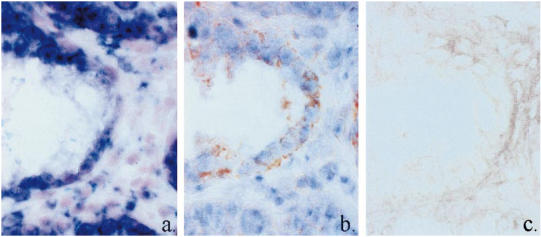

Fig. 6.

TNF-α protein in damaged epithelium in scid colitis does not correlate with TNF-α mRNA expression and is not derived from activated macrophages. (a) TNF-α mRNA, antisense riboprobe. (b) TNF-α protein, MoAb XT3, immunohistochemistry. (c) Immunohistochemistry for activated macrophages, MoAb 158.2. Serial sections. (All × 100 oil objective.)

TNF-a translation

There was no immunohistochemical evidence of TNF-α protein either in non-transplanted scid mice, or C.B-17+/+ mice, even in tissues in which transcription had been demonstrated.

In colitis, lamina propria TNF-α protein followed the same distribution as mRNA, and correlated with areas of activated macrophage infiltration (Fig. 5b,c,d) (P < 0.001, Table 2). TNF-α protein was not observed in the epithelium in colitis, except in crypts in which the epithelium was undergoing late stages of destruction—interestingly, the epithelium in which reduced levels of transcription had been observed (Fig. 6b).

DISCUSSION

We have shown enhanced mucosal synthesis of TNF-α, and that activated macrophages are the primary source in scid colitis, as postulated in human CD [22,38,39]. The latter observation, combined with the lack of significant enhancement of TNF-α in mild disease compared with control tissue, suggests the possibility of two stages in the inflammatory process: the first, in which IFN-γ secreted by activated Th1 cells leads to activation of tissue macrophages, low level secretion of TNF-α and secretion of other macrophage cytokines (e.g. IL-8 and IL-12); and a second stage, whereby macrophages and polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMN) are attracted to the site of inflammation (by IL-8 for example) and become activated by macrophage-derived TNF-α acting in combination with T cell-derived IFN-γ, leading to self-amplifying inflammation, the formation of granulomata and the observed tissue destruction. In two recent studies of animal models, it has been shown that the continued presence of active TNF-α is important to maintain chronic experimental colitis. Thus, in the TNBS model [40] and in the CD45RBhi transfer model of colitis [15], antibodies to TNF-α ameliorated disease development and led to much improved histological features of established disease. Neurath et al. [40] noted that TNBS administration could not induce colitis in TNF-α knockout mice and that administration of TNBS to TNF-α transgenic mice led to a greatly enhanced disease and death of some mice within days. The importance of T cell-secreted IFN-γ has been demonstrated by the lack of colitis induction in scid mice after transfer of CD45RBhi T cells from IFN-γ knockout mice [41], and by the demonstration that administration of antibodies to IFN-γ soon after T cell transfer delayed development of disease for 12 weeks [15]. Early administration of anti-TNF-α antibody was unable to ameliorate disease, and continuous neutralization was necessary to reduce the incidence of severe disease [15]. This supports our own in situ observations of T cell involvement in pathogenesis earlier than that of macrophages, and that macrophage production of TNF-α is important for the later stages of tissue destruction. To define further the interplay between IFN-γ and TNF-α in the pathogenesis of colitis, time course studies are in progress.

An unexpected finding was made during this study that although colonic epithelial cells were shown to transcribe TNF-α mRNA from a very early stage of disease, TNF-α protein was only found in epithelium undergoing advanced stages of damage. The epithelial mRNA appeared to be in the expected cytoplasmic location in all stages of hyperplasia, although some evidence of basolateral polarization was seen in epithelium undergoing damage. Although the epithelium of C.B-17 mice did not express mRNA for TNF-α, non-transplanted scid mice displayed mRNA in their deep crypt epithelium. This may simply indicate the differentiative status of the cells (TNF-α mRNA has been observed in pre-B cells and fetal organs [42]), or their hyperplastic potential (epithelial tumour cell lines commonly express TNF-α mRNA [42]), or circumvention of post-transcriptional mRNA degradation. Although not yet explained, TNF-α transcription in the non-colitic scid mouse colonic epithelium does indicate a potentially pathogenic difference compared with its parent strain.

Epithelial cells have been shown to be capable of TNF-α protein synthesis, both in cultured cells [43,44] and as freshly isolated cells on bacterial invasion [45]. Our inability to detect TNF-α protein in the hyperplastic epithelium may be due to kinetics of protein production following mRNA expression. However, studies of the kinetics of TNF-α transcription and translation in many cell types in vitro and in vivo produce consistent results [45–47]: mRNA levels peak at 3–4 h after stimulation and are undetectable by 48 h; surface-expressed TNF-α peaks at 3–4 h; and soluble TNF-α peaks at 8–12 h. Therefore, we would expect to detect at least surface expressed TNF-α concurrently with mRNA. Our inability to detect TNF-α protein in the hyperplastic epithelium could be methodological—soluble cytokines such as TNF-α can be cross-linked or washed away by processing steps and may subsequently be undetectable by antibody towards TNF-α. Alternatively, it is possible that hyperplastic epithelial cells may be extremely effective at secreting the protein into the intestinal lumen. This could account for some of the TNF-α which is seen to be elevated in the stools of human patients with active CD [22]. On the other hand, it is possible that our observation reflects selective post-transcriptional blockade of TNF-α translation in the hyperplastic epithelial cells. The production of TNF-α is tightly controlled at the transcriptional, post-transcriptional and translational levels, reflecting the potential for damage by unregulated TNF-α release. TNF-α mRNA contains AU-rich regions within the 3′ untranslated region which act as an RNase attack site [48,49] and decrease the stability of mRNA. It has been proposed that for TNF-α translation to proceed in some cell types, a cytoplasmic AU-binding protein (AU-B) must stabilize the mRNA [50]. This binding protein requires new transcription and new translation and its synthesis mirrors the kinetics of lymphokine production following cell activation. It is possible that the transcripts which we detect in hyperplastic epithelial cells are degraded and not translatable. Alternatively, other mechanisms may exist in epithelial cells for blocking translation, conceivably by binding of suppresser proteins to the 5′ promoter region. These mechanisms may be lost when the epithelial cell reaches a stage where its death is inevitable, e.g. in epithelium undergoing advanced damage. Conversely, there may be cell-specific mechanisms in activated macrophages for circumvention of post-transcriptional control and stabilization of TNF-α mRNA, leading to prolonged translation of TNF-α, crucial to the pathogenesis of colitis. In support of this theory is a study where polymorphism in the TNF-α promoter associated with increased TNF-α production was found in Crohn's patients [51]. Further analysis of cell-specific transcriptional control of TNF-α may benefit the development of targeted anti-inflammatory therapy in IBD.

Although lamina propria macrophages play an important role in mucosal defence by phagocytosis of invading organisms, activated macrophages and their cytokines are clearly very important to the pathogenesis of IBD. A recent study observed that injection of rTNF-α induced rapid apoptosis and detachment of small intestinal epithelial cells [52]. This may have been a direct effect of TNF-α, or it may reflect TNF-α-induced metalloproteinase secretion by macrophages, which has been shown to decrease epithelial adherence [53] and is known to induce rapid apoptosis [54]. T cell-derived IFN-γ has been shown to up-regulate expression of TNF-R1 on epithelial cells [52]. In the scid mouse, activated T cells secreting IFN-γ could increase the sensitivity of epithelial cells to TNF-α-induced apoptosis. In combination with dysregulated macrophage TNF-α production, this would present an extremely damaging situation for the epithelium.

Finally, it is possible that the immune defect in scid mice impinges on epithelial integrity, permitting the initial barrier breakdown which causes mucosal T cell activation. Relevant to this, it has been shown that lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-activated epithelial cells are capable of down-regulating macrophage TNF-α production in an in vitro co-culture system [55]. If this mechanism of homeostasis acts in vivo, then epithelial cells in the scid mouse, which lack normal cross-talk with immune elements in the mucosa, may not be able to perform this function, possibly resulting in unchecked macrophage TNF-α synthesis and its damaging sequelae.

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge the financial support of the European Union contract no. BMH4-CT96-0612 and the use of photographic equipment funded by BBSRC grant no. 7/S09245.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sadlack B, Merz H, Schorle H, Schimpl A, Feller AC, Horak I. Ulcerative colitis-like disease in mice with a disrupted interleukin-2 gene. Cell. 1993;75:253–61. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80067-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kühn RL, Löhler J, Rennick D, Rajewsky K, Müller W. Interleukin-10-deficient mice develop chronic enterocolitis. Cell. 1993;75:263–14. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80068-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mombaerts P, Mizoguchi E, Grusby MJ, Glimcher LH, Bhan AK, Tonegawa S. Spontaneous development of inflammatory bowel disease in T cell receptor mutant mice. Cell. 1993;75:275–82. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80069-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hornquist CE, Lu X, Rogers-Fani PM, Rudolph U, Shappell S, Birnbaumer L, Harriman GR. Gαi2-deficient mice with colitis exhibit a local increase in memory CD4+T cells and proinflammatory Th1-type cytokines. J Immunol. 1997;158:1068–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morrissey PJ, Charrier K, Braddy S, Liggitt D, Watson JD. CD4+ T cells that express high levels of CD45RB induce wasting disease when transferred into congenic severe combined immunodeficient mice. Disease development is prevented by co-transfer of purified CD4+T cells. J Exp Med. 1993;178:237–44. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.1.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Powrie F, Leach MW, Mauze S, Caddle LB, Coffman RL. Phenotypically distinct subsets of CD4+T cells induce or protect against chronic intestinal inflammation in C.B-17 Scid mice. Int Immunol. 1993;5:1461–71. doi: 10.1093/intimm/5.11.1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Powrie F, Correa-Oliveira R, Mauze S, Coffman RL. Regulatory interactions between CD45RBhi and CD45RBlo, CD4+ T cells are important for the balance between protective and pathogenic cell mediated immunity. J Exp Med. 1994;179:589–600. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.2.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leach MW, Bean AG, Mauze S, Coffman RL, Powrie F. Inflammatory bowel disease in C.B-17 scid mice reconstituted with the CD45RBhi subset of CD4+ T cells. Am J Pathol. 1996;148:1503–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rudolphi A, Boll G, Poulsen SS, Claesson MH, Reimann J. Gut-homing CD4+ T cell receptor alpha+ beta+ T cells in the pathogenesis of murine inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:2803–12. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830241134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonhagen K, Thoma S, Bland P, Bregenholt S, Rudolphi A, Claesson MH, Reimann J. Cytotoxic reactivity of gut lamina propria CD4+αβ T cells in scid mice with colitis. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:3074–83. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830261238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reimann J, Rudolphi A, Claesson MH. Reconstitution of scid mice with low numbers of CD4+ TCR alpha beta+ T cells. Res Immunol. 1994;145:332–7. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2494(94)80195-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rudolphi A, Bonhagen K, Reimann J. Polyclonal expansion of adoptively transferred CD4+ alpha beta T cells in the colonic lamina propria of scid mice with colitis. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:1156–63. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rudolphi A, Enssle KH, Claesson MH, Reimann J. Adoptive transfer of low numbers of CD4+ T cells into scid mice chronically treated with soluble IL-4 receptor does not prevent engraftment of IL-4-producing T cells. Scand J Immunol. 1993;38:57–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1993.tb01694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bregenholt S, Claesson MH. Increased intracellular Th1 cytokines in scid mice with inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:379–89. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199801)28:01<379::AID-IMMU379>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Powrie F, Leach MW, Mauze S, Menon S, Caddle LB, Coffman RL. Inhibition of Th1 responses prevents inflammatory bowel disease in scid mice reconstituted with CD45RBhi CD4+ T cells. Immunity. 1994;1:553–62. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fiorentino DF, Zlotnik A, Mosmann TR, Howard M, O'Garra A. Interleukin 10 inhibits cytokine production by activated macrophage. J Immunol. 1991;147:3815–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Groux H, O'Garra A, Bigler M, Rouleau M, Antonenko S, deVries JE, Roncarolo MG. A CD4+ T cell subset inhibits antigen-specific T cell responses and prevents colitis. Nature. 1997;389:737–41. doi: 10.1038/39614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Asseman C, Powrie F. Interleukin 10 is a growth factor for a population of regulatory T cells. Gut. 1998;42:157–8. doi: 10.1136/gut.42.2.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Powrie F, Carlino J, Leach MW, Mauze S, Coffman RL. A critical role for transforming growth factor beta but not IL-4 in the suppression of T helper type 1 mediated colitis by CD45RBlo CD4+T cells. J Exp Med. 1996;183:2669–74. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.6.2669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacDonald TT, Hutchings P, Choy MY, Murch S, Cooke A. Tumour necrosis factor α and interferon γ production measured at the single cell level in normal and inflamed human intestine. Clin Exp Immunol. 1990;S1:301–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1990.tb03334.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murch S, Lambkin VA, Savage MO, Walker-Smith JA, MacDonald TT. Serum concentrations of tumour necrosis factor α in childhood chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 1991;32:913–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.32.8.913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murch SH, Braegger CP, Walker-Smith JA, MacDonald TT. Location of tumour necrosis factor α by immunohistochemistry in chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 1993;34:1705–9. doi: 10.1136/gut.34.12.1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Isaacs KL, Sartor LB, Haskill JS. Cytokine mRNA profiles in inflammatory bowel disease mucosa detected by PCR amplification. Gastroenterol. 1992;103:1587–95. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)91182-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stevens C, Walz G, Singaram C, et al. Tumour necrosis factor-α, interleukin-1β, and interleukin-6 expression in inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 1992;37:818. doi: 10.1007/BF01300378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reimund JM, Dumont S, Muller CD, Kenney JS, Kedinger M, Baumann R, Poindron P, Duclos B. In vitro effects of oxpentifylline on inflammatory cytokine release in patients with IBD. Gut. 1997;40:475–80. doi: 10.1136/gut.40.4.475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bauditz J, Haemling J, Ortner M, Lochs H, Raedler A, Schreiber S. Treatment with tumour necrosis factor inhibitor oxpentifylline does not improve corticosteroid dependant chronic active Crohn's disease. Gut. 1997;40:470–4. doi: 10.1136/gut.40.4.470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katz J, Geraci K. An open trial of pentoxifylline for active Crohn's disease. Gastroenterol. 1997;112:A1009. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stack WA, Man SD, Roy AJ, et al. Randomised controlled trial of CDP571 antibody to tumour necrosis factor-α in Crohn's disease. Lancet. 1997;349:521–4. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)80083-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Dullemen HM, van Deventer SJH, Hommes DW, Bijl HA, Jansen J, Tytgat GNJ, Woody J. Treatment of Crohn's disease with anti-tumour necrosis factor chimeric monoclonal antibody (cA2) Gastroenterol. 1995;109:129–35. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90277-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Targan SR, Hanauer SB, van Deventer SJH, et al. A short-term study of chimeric monoclonal antibody cA2 to tumour necrosis factor-α for Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1029–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199710093371502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rutgeerts P, D’Haens G, van Deventer SJH, et al. Retreatment with anti-TNF-α chimeric antibody (cA2) effectively maintains cA2-induced remission in Crohn's disease. Gastroenterol. 1997;112:A1078. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson AR. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sanger F, Coulson AR, Barrell BG, Smith AJM, Roe BA. Cloning in single stranded bacteriophage as an aid to rapid DNA sequencing. J Mol Biol. 1980;143:161–78. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(80)90196-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ezekowitz RAB, Austyn J, Stahl P, Gordon S. Surface properties of BCG-activated mouse macrophages; reduced expression of mannose specific endocytosis, Fc receptors, and antigen F4/80 accompanies induction of Ia. J Exp Med. 1981;154:60–76. doi: 10.1084/jem.154.1.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hume DA, Robinson AP, Macpherson GG, Gordon S. The mononuclear phagocyte system of the mouse defined by immunohistochemical localisation of the antigen F4/80; relationship between macrophages, Langerhans cells, reticular cells, and dendritic cells in lymphoid and hematopoietic organs. J Exp Med. 1983;158:1522–36. doi: 10.1084/jem.158.5.1522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McKnight AJ, Macfarlane AJ, Dris P, Turley L, Willis C, Gordon S. Molecular cloning of F4/80, a macrophage-restricted cell surface glycoprotein with homology to the G-protein linked transmembrane 7 hormone receptor family. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:486–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.1.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haidl ID, Jefferies WA. The macrophage cell surface glycoprotein F4/80 is a highly glycosylated proteoglycan. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:1139–46. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Woywodt A, Neustock P, Kruse A, Schwarting K, Ludwig D, Stange EF, Kirchner H. Cytokine expression in intestinal mucosal biopsies. In situ hybridisation of the mRNA for interleukin-1β, interleukin-6 and tumour necrosis factor-α in inflammatory bowel disease. Eur Cytokine Netw. 1994;5:387–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cappello M, Keshav S, Prince C, Jewell DP, Gordon S. Detection of mRNAs for macrophage products in inflammatory bowel disease by in situ hybridisation. Gut. 1992;33:1214–9. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.9.1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Neurath MF, Fuss I, Pasparakis M, et al. Predominant pathogenic role of tumour necrosis factor in experimental colitis in mice. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:1743–50. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ito H, Fathman CG. CD45RBhi CD4 T cells from IFN-γ knockout mice do not induce wasting disease. JAI. 1997;10:455–9. doi: 10.1016/s0896-8411(97)90152-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vassali P. The pathophysiology of tumour necrosis factors. Ann Rev Immunol. 1992;10:411–52. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.10.040192.002211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spriggs DR, Imamura K, Rodriguez C, Sariban E, Kufe D. Tumour necrosis factor expression in human epithelial tumour cell lines. J Clin Invest. 1988;81:455–60. doi: 10.1172/JCI113341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Greten TF, Moeller J, Feldmeier H, Eigler A, Endres S. Synthesis of tumour necrosis factor-α in tissue culture of rat caecum: lack of suppression by phosphodiesterase inhibitors and prostanoids. Eur J Gast Hepat. 1996;8:679–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jung HC, Eckmann L, Yang S-K, Panja A, Fierer J, Morzycka-Wroblewska E, Kagnoff MF. A distinct array of proinflammatory cytokines is expressed in human colon epithelial cells in response to bacterial invasion. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:55–65. doi: 10.1172/JCI117676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mohler KM, Butler LD. Quantitation of cytokine mRNA levels utilising the reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction following primary antigen specific sensitisation in vivo. I. Verification of linearity, reproducibility and specificity. Mol Immunol. 1991;28:437–47. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(91)90157-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.di Giovine FS, Malawista SE, Thornton E, Duff GW. Urate crystals stimulate production of tumour necrosis factor alpha from human blood monocytes and synovial cells: cytokine mRNA and protein kinetics, and cellular distribution. J Clin Invest. 1991;87:1375–81. doi: 10.1172/JCI115142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Caput D, Beutler B, Hartog K, Thayer R, Brown-Shimer S, Cerami A. Identification of a common nucleotide sequence in the 3′-untranslated region of mRNA molecules specifying inflammatory mediators. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:1670–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.6.1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shaw G, Kamen R. A conserved AU sequence from the 3′-untranslated region of GM-CSF mRNA mediates selective mRNA degradation. Cell. 1986;46:659–67. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90341-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bohjanen PR, Petryniak B, June CH, Thompson CB, Lindsten T. An inducible cytoplasmic factor (AU-B) binds selectively to AUUUA multimers in the 3′-untranslated region of lymphokine mRNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;1:3288–95. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.6.3288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Plevy SE, Targan SR, Rotter JI, Toyoda H. Tumour necrosis factor (TNF) microsatellite associations within HLA-DR2 patients define Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC)-specific genotypes. Gastroenterol. 1994;106:A754. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guy-Grand D, DiSanto JP, Henchoz P, Malassis-Seris M, Vassalli P. Small bowel enteropathy: role of intraepithelial lymphocytes and of cytokines (IL-12, IFN-γ, TNF-α) in the induction of epithelial cell death and renewal. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:730–44. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199802)28:02<730::AID-IMMU730>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pender SLF, Tickle SP, Docherty AJP, Howie D, Wathen NC, MacDonald TT. A major role for matrix metalloproteinases in T cell injury in the gut. J Immunol. 1997;158:1582–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cordone MH, Salvesen GS, Widman C, Johnson G, Frisch SM. The regulation of anoikis: MEKK-1 activation requires cleavage by caspases. Cell. 1997;90:315–23. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80339-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nathens AB, Rotstein OD, Dackiw APB, Marshall JC. Intestinal epithelial cells down-regulate macrophage tumour necrosis factor α secretion: a mechanism for immune homeostasis in the gut associated lymphoid tissue. Surgery. 1995;118:343–51. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(05)80343-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]