Abstract

Vitamin Ds have been reported to have diverse effects on cell homeostasis, leading to suggestions that they have therapeutic applications extending beyond their traditional actions on the Ca2+/parathyroid/bone axis. As some of these potential indications carry an inherent risk of acute renal failure (ARF; eg, cancer chemotherapy and organ transplantation), the goal of this study was to assess whether vitamin Ds directly affect renal tubule injury responses. Cultured human proximal tubular (HK-2) cells were exposed to physiological or pharmacological doses of either calcitriol (D3) or a synthetic vitamin D2 analogue (19-nor) for 3 to 48 hours. Their impact on cell integrity (percent lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release and tetrazolium dye MTT uptake) under basal conditions and during superimposed injuries (ATP depletion/Ca2+ ionophore or iron-mediated oxidant stress) were determined. As vitamin Ds can be anti-proliferative, cell outgrowth ([3H]thymidine uptake and crystal violet staining) was also tested. Finally, the action of D3 on in vivo ARF (glycerol-induced myoglobinuria) and isolated proximal tubule injury responses were assessed. D3 induced a rapid, dose-dependent increase in HK-2 susceptibility to both ATP-depletion/Ca2+-ionophore- and Fe-mediated attack without independently affecting cell integrity or proliferative responses. In contrast, D2 negatively affected only Fe toxicity and only after relatively prolonged exposure (48 hours). D3 dramatically potentiated in vivo ARF (two- to threefold increase in azotemia), suggesting potential in vivo relevance of the above HK-2 cell results. Proximal tubules, isolated from these glycerol-exposed mice, suggested that D3 can worsen tubule injury despite a parodoxic suppression of H2O2 production. In contrast, D3 had a mild negative impact on cellular energetics (depressed ATP/ADP ratios), and it accentuated plasma membrane phospholipid breakdown. The latter was observed in both glycerol-treated and control tubules, suggesting a primary role in the injury- potentiation effect of D3. Vitamins D(s) may directly, and differentially, increase proximal tubule cell susceptibility to superimposed attack. This property should be considered as new uses for these agents are defined.

Over the past 15 years, there has been steadily increasing evidence that vitamin D can exert diverse effects on cell homeostasis, extending well beyond its capacity to regulate gut and renal calcium/phosphate transport and bone mineralization. 1 The discovery that vitamin D receptors exist outside of traditional target organs (intestine, kidney, and bone) underscores vitamin D’s potentially broad-ranging biological effects. 2,3 Several examples of nonclassical vitamin D actions are as follows: 1) vitamin D can stimulate cellular differentiation, a phenomenon first identified by its ability to facilitate promyeloid→granulocyte or macrophage conversions 4,5 ; 2) it can inhibit cell proliferation, as evidenced by its ability to retard the growth of malignant cell lines that possess the genomic vitamin D receptor 6,7 ; and 3) vitamin D can down-regulate T-cell-mediated immune responses. 8-10 The latter is indicated by a growing literature that vitamin Ds can suppress experimental lupus nephritis, 11 ablation nephropathy, 12 rheumatoid arthritis, 13 allergic encephalomyelitis, 14,15 and transplant rejection across HLA incompatibility lines. 1,16,17 Given these anti-neoplastic, anti-inflammatory, and immunosuppressive effects, it is not surprising that intense efforts are underway to synthesize new vitamin D analogues that optimize these novel therapeutic applications while avoiding unwanted hypercalcemic/hypercalciuric side effects.

As the indications for vitamin Ds are likely to increase, it seems important to more completely define their influence on renal tubular cell homeostasis. Because acute renal injury is likely to occur in many potentially targeted patient populations (eg, cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy and organ transplant patients receiving cyclosporine), vitamin D’s impact on tubular injury responses seems particularly relevant. It is already known that some consequences of vitamin D therapy, namely, hypercalcemia and hyperphosphatemia, can exacerbate 18-22 or attenuate 23-26 selected forms of acute renal failure (ARF). However, whether vitamin D directly alters tubular cell injury has not been established.

In light of the above considerations, the present study was undertaken to address some potential vitamin D influences on renal tubular cell homeostasis. To this end, cultured human proximal tubular cells were treated with either physiological or pharmacological doses of 1,25-(OH)2-D3 (calcitriol) or 19-nor-1,25-(OH)2-D2 (19-nor), a synthetic vitamin D analogue recently released for treatment of secondary hyperparathyroidism. 27,28 After variable lengths of exposure, the impact of these two agents on tubular cell homeostasis and susceptibility to superimposed injury (ATP depletion/Ca2+ ionophore treatment or iron-mediated oxidant stress) were assessed. As these cell culture experiments indicated that vitamin D can, indeed, accentuate tubular cell injury responses, additional experiments were performed to 1) ascertain the potential in vivo relevance of these in vitro observations and 2) explore possible mechanisms by which vitamin D might exert this effect.

Materials and Methods

HK-2 Cell Culture Experiments: Culture Conditions

HK-2 cells, an immortalized proximal tubular cell line derived from normal human kidney, 29 were used for all cell culture experiments. The cells were maintained (at 37°C and 5% CO2) in T75 Costar flasks (Cambridge, MA) with keratinocyte serum-free medium (K-SFM; Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) containing 1 mmol/L glutamine, 5 ng/ml epidermal growth factor, 40 μg/ml bovine pituitary extract, 25 U/ml penicillin, and 25 μg/ml streptomycin. At near confluence, the cells were trypsinized 29 and transferred to either additional T75 flasks (for passage) or to 24-well Costar plates (for experimentation, as described below). Shortly after seeding the cluster plates, selected wells were spiked with 10 μl of K-SFM or with 10 μl of K-SFM containing either 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (calcitriol), or 19-nor-1-α-dihydroxyvitamin D2 (19-nor). These two agents were provided as a gift from Abbott Laboratories (L. Mershimer, Abbott Park, IL). Calcitriol was added to achieve a final 50 pg/ml (physiological, ie, a normal human plasma calcitriol concentration) or 250 pg/ml (pharmacological) concentration (1:20,000 and 1:4000 dilutions in K-SFM, respectively). Additional wells were exposed to biologically equivalent doses of 19-nor (200 and 1000 pg/ml, based on a 4:1 potency of calcitriol versus 19-nor; 1:25,000 and 1:5000 dilutions in K-SFM, respectively). (Hence, the 200 pg/ml dose is again a pharmacologically/physiologically relevant concentration.) Finally, additional wells were exposed to calcitriol or 19-nor vehicle as controls. For studies lasting >24 hours, the culture media (with the appropriate vitamin D doses) were changed each day.

Calcitriol Effects on ATP Depletion/Ca2+ Overload Injury

HK-2 cells were grown within cluster plates with or without calcitriol. Within each 24-well plate, 8 wells were treated with 0, 50, or 250 pg/ml calcitriol unless stated otherwise. After variable periods of calcitriol treatment (see below) the cells were subjected to ATP depletion (addition of 7.5 μmol/L antimycin plus 10 mmol/L 2-deoxyglucose) plus Ca2+ overload (5 μmol/L A23187 Ca2+ ionophore) injury, as previously described. 30,31 The original calcitriol concentrations were maintained during the injury period. The extent of cell injury was assessed either by calculating percent lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release or by determining cellular uptake of the tetrazolium dye MTT. 29-32 The specifics of individual experiments were as follows.

Eighteen-Hour Calcitriol Pretreatment/Four-Hour Challenge

After completing 18 hours of 0, 50, or 250 pg/ml calcitriol treatment, one-half the wells of cells were challenged with antimycin/2-deoxyglucose/A23187, as noted above. Four hours later, cell injury was assessed by MTT uptake, as previously described. 29 Cells co-incubated with 0, 50, or 250 pg/ml calcitriol/vehicle and not subjected to ATP depletion/Ca2+ overload injury established baseline MTT uptake values.

Eighteen-Hour Calcitriol Pretreatment/Sixteen-Hour Challenge

After completing 18-hour exposures to either 0 or 250 pg/ml calcitriol, one-half of the cells were subjected to the ATP depletion/A23187 challenge for 16 hours, as noted above. Cell injury was then assessed by calculating percent LDH release. 33 The remaining half of the cells, exposed only to 0/vehicle or to 250 pg/ml calcitriol concentrations, established control percent LDH release values.

Thirty-Hour Calcitriol Pretreatment/Sixteen-Hour Challenge

Cells were exposed to 0, 50, or 250 pg/ml calcitriol for 30 hours, followed by a 16-hour ATP depletion/Ca2+ overload challenge. Cell injury was assessed by percent LDH release. Unchallenged cells established control percent LDH values, as noted above.

In each of the above three sets of experiments, between 8 and 24 wells of cells subjected to each of the above conditions/protocols on two to four separate occasions were used to establish each of the experimental groups.

19-Nor Effects on ATP Depletion/Ca2+ Overload Injury

Eighteen-Hour 19-Nor Pretreatment/Four-Hour Challenge

HK-2 cells were cultured for 18 hours in the presence of either 0, 200, or 1000 pg/ml 19-nor. The cells then underwent the 4-hour ATP depletion/Ca2+ overload challenge, followed by assessment of cell injury by the MTT assay. One-half of the wells in each plate were maintained under control culture conditions with or without 200 or 1000 pg/ml 19-nor, thereby establishing normal MTT uptake values; n = 8 to 12 wells for each of the above treatment groups).

Eighteen-Hour 19-Nor Pretreatment/Sixteen-Hour Challenge

The above experiment was repeated exactly as detailed with the exceptions that 1) the challenge was administered for 16 hours rather than 4 hours and 2) cell injury was assessed by percent LDH release.

Forty-Eight-Hour 19-Nor Treatment/Sixteen-Hour Challenge

The following experiment assessed whether a more prolonged exposure to 19-nor might unmask an injury-promoting effect. HK-2 cells were cultured with 0, 200, or 1000 pg/ml 19-nor for 48 hours. At the end of this period, the cells were subjected to the 16-hour ATP depletion/Ca2+ ionophore challenge, followed by assessment of percent LDH release, as above. Co-cultured cells maintained under the same conditions, but without the ATP depletion/Ca2+ overload challenge, served as controls.

Calcitriol and 19-Nor Effects on Fe-Mediated Oxidative Tubular Injury

The following experiments were undertaken to ascertain whether calcitriol’s effects on the expression of cell injury is unique to ATP depletion/Ca2+ overload injury or whether it is more diversely expressed. Hence, its impact on iron-mediated oxidant stress was assessed. For comparison, the impact of 19-nor was also determined. In each of these oxidant injury experiments, between 8 and 24 wells of cells, subjected to the following protocols on two to four separate occasions, were studied.

Three-Hour Vitamin D Pretreatment/Sixteen-Hour Iron Challenge

Within 2 hours of seeding 24-well cluster plates with HK-2 cells, they were exposed to either 0, 50, or 250 pg/ml calcitriol. Approximately 3 hours later, the cells were exposed to Fe-mediated oxidant injury (addition of 10 μmol/L ferrous ammonium sulfate, complexed to 10 μmol/L 8-hydroxyquinoline (HQ; a siderophore, permitting ready intracellular iron access 34 ). After completing a 16-hour Fe/HQ exposure, cell injury was assessed by percent LDH release. Co-incubated cells treated identically to those above, but without Fe/HQ exposure, served as controls.

The experiment described immediately above was repeated, substituting 19-nor (0, 200, or 1000 pg/ml) for calcitriol treatment.

Forty-Eight-Hour Vitamin D Pretreatment/Sixteen-Hour Iron Challenge

Cells were exposed to calcitriol (0, 50, or 250 pg/ml) for 48 hours, followed by a 16-hour Fe/HQ challenge, as noted above. Cell injury was assessed by percent LDH release. An equal number of wells co-incubated with equal amounts of calcitriol/vehicle, but not subjected to the Fe/HQ challenge, established baseline percent LDH release values. The experiment described immediately above was repeated, substituting 19-nor (0, 200, or 1000 pg/ml) for calcitriol.

Calcitriol and 19-Nor Effects on HK-2 Cell Proliferation

The following experiments were undertaken to ascertain whether vitamin D alters HK-2 cell proliferation, possibly contributing to its injury-potentiating effect. Proliferation was gauged by two independent methods: thymidine incorporation and crystal violet assay.

[3H]Thymidine Incorporation

For the 18-hour incubations, HK-2 cells were plated in 12-well Costar plates and cultured for 18 hours under one of the following conditions: 1) control incubation, 2) addition of 50 or 250 pg/ml calcitriol, or 3) incubation with 200 or 1000 pg/ml 19-nor. Within 2 hours of establishing these conditions, [3H]thymidine (2 μCi/well; Amersham; Arlington Heights, IL) was added to each well. Eighteen hours later, the media were removed, the cells were washed twice with 2 ml of cold phosphate-buffered saline, and then 200 μl of 70% perchloric acid was added to each well. The acid-precipitable material was then solubilized in 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS). 35 The samples (media and acid-precipitable cell extracts) were transferred to scintillation vials, the radioactivity in each was measured (LS6000IC scintillation counter, Beckman Instruments, Fullerton, CA), and the percent cellular thymidine uptake was determined (n = 8 wells for each treatment; 16 wells of controls).

To further assess the impact of vitamin D on cellular [3H]thymidine uptake, the above experiment was repeated, except that the cells were treated with the vitamin Ds for 30 hours before [3H]thymidine addition. After completing an 18-hour [3H]thymidine exposure, percent thymidine uptake was assessed as noted above (n = 4 wells with each treatment; 8 wells of controls).

Crystal Violet Assay

HK-2 cells were cultured for 48 hours in 24-well plates under control conditions or with either calcitriol (50 or 250 pg/ml) or 19-nor (200 or 1000 pg/ml) exposure. Cell numbers were then assessed by the crystal violet staining technique. 36 In brief, after completing the above incubations, the cells were fixed by addition of 1% glutaraldehyde. They were washed, dried, and stained with crystal violet (0.5%; in methanol:water, 20:80%). Unfixed crystal violet was removed by washing four times, and then the plates were re-dried. Finally, the adherent crystal violet in each well was solubilized with 1% SDS, and the absorbance units were simultaneously determined (96-well microtiter plate reader; 600-nm filter; n = 8 separate wells for each vitamin D treatment and 16 controls).

To validate the crystal violet method for assessing HK-2 cell numbers, a 96-well Costar plate was seeded with serial cell dilutions (16,000, 8,000, 4,000, 2,000, 1,000, or 500 cells per well; n = 6 each). The plates were cultured for 18 hours, and then crystal violet staining was performed. The absorbance units were correlated with the number of starting cells.

Impact of Vitamin D Therapy on in Vivo Renal Tubular Injury

The glycerol model of myohemoglobinic ARF is mediated, in part, by iron-induced oxidant stress and ATP depletion. 37-41 As calcitriol exacerbated both of these forms of injury in HK-2 cells (see Results), the following experiments were undertaken to assess possible in vitro/in vivo correlate(s). To this end, 20 male CD-1 mice (35 to 40 g; Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) were lightly anesthetized with pentobarbital (2 mg intraperitoneally) and divided into four groups: 1) glycerol injection alone (8 ml/kg 50% glycerol, administered in equally divided doses into each upper hind limb plus calcitriol vehicle (50 μl intraperitoneally; n = 6)), 2) glycerol injection plus calcitriol (glycerol plus 50 ng of calcitriol (50 μl; n = 6)), 3) calcitriol alone, administered as noted above (n = 4), and 4) controls (50 μl of vehicle injection alone (n = 4)).

After completing the injections, the mice were maintained under heating lamps for 2 hours to maintain body temperature while recovering from anesthesia. They were then returned to their cages and given free food and water access. Eighteen hours later, they were re-anesthetized, and the abdominal cavities were opened and exsanguinated from the aorta using a heparinized syringe. Terminal blood urea nitrogens, plasma creatinines, and total plasma calciums were determined on all animals. Animals subjected to glycerol injection had their kidneys removed, and frontal sections were cut and fixed in 10% buffered formalin. Four-micron paraffin-embedded sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin for histological analysis.

Isolated Tubule Experiments

The following experiments were undertaken to further assess the impact of calcitriol on selected determinants of heme protein- induced tubular cytotoxicity, 37-41 using a previously published combined in vivo/in vitro approach. 33,37 In brief, mice are subjected to glycerol injection, and 2 hours later cortical tubules are isolated for in vitro investigation. 33,37 This technique permits direct assessments of evolving heme protein tubular toxicity (oxidant stress, mitochondrial suppression, membrane injury) over a 30–60 minutes in vitro incubation period.

Tubule H2O2 Production

Eight mice were injected with 8 ml/kg glycerol with (n = 4) or without (n = 4) calcitriol, as noted above. Two hours later, the kidneys were removed, the cortices dissected, and proximal tubule segments (PTSs) were harvested as previously described. 37 A plasma sample was saved at the time of kidney removal and used for creatine phosphokinase (CPK) assay (CPK kit; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO), used as an index of glycerol-induced muscle injury. The harvested tubules were incubated for 60 minutes to assess H2O2 generation rates by the phenol red/horseradish peroxidase technique, as previously described in detail. 39 Corresponding percent LDH releases at the end of these incubations were determined as an index of heme protein cytotoxicity. To assess independent calcitriol effects on H2O2 generation and LDH release, tubules were isolated from six non-glycerol-exposed mice treated 2 hours earlier with calcitriol or vehicle (n = 3 each). They were treated and analyzed as above.

Cellular Energetics

Six mice were injected with glycerol, three with and three without concomitant calcitriol treatment. Two hours later, PTSs were harvested and incubated in vitro under standard conditions. 37 After completing 15-minute incubations, tubule adenine nucleotides were extracted in trichloroacetic acid and analyzed for ATP, ADP, and AMP content by high-pressure liquid chromatography. 37 Mitochondrial respiratory integrity was assessed by ATP/ADP ratios. 37 Independent calcitriol effects were determined by repeating the above experiment in six non-glycerol-exposed mice, treated with or without calcitriol therapy (n = 3 each).

Plasma Membrane Phospholipid Integrity during Heme Attack

Twelve mice were injected with glycerol, half with calcitriol or vehicle, as noted above. Two hours later, PTSs were isolated and subjected to 60-minute incubations under routine conditions. 33,37 At the completion of each incubation, percent LDH release was determined, and then the PTSs underwent chloroform/methanol (2:1) lipid extraction. 42 The lipid extracts were then subjected to two-dimensional gel thin-layer chromatography. 43 Individual plasma membrane phospholipids were scraped from the silica plates and quantified by the recovered inorganic phosphate content. 42 Controls for sphingomyelin (SM), phosphatidylcholine (PC), phosphatidylserine (PS), phosphatidylinositol (PI), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), and lyso-PC, and lyso-PE were simultaneously run. Individual phospholipids were expressed as nmoles per milligram of protein in the extracted tubule samples. Both total plasma membrane phospholipid (SM plus PC plus PE plus PS plus PI) and percent contribution of each to the total were calculated.

Independent Calcitriol Effects on Plasma Membrane Phospholipids

Eight mice were injected with either calcitriol (n = 4) or vehicle, and 2 hours later tubules were isolated. After completing 30-minute in vitro incubations, plasma membrane phospholipids were determined and analyzed as noted above.

Calculations and Statistics

All values are given as means ± 1 SEM. Unless stated otherwise, statistical comparisons were made by paired or unpaired Student’s t-test, as appropriate. If more than one comparison was made within a given experiment, the Bonferroni correction was applied. Significance was judged by a P value of <0.05.

Results

Calcitriol Effects on ATP Depletion/Ca2+ Overload Injury

Eighteen-Hour Pretreatment/Four-Hour Challenge

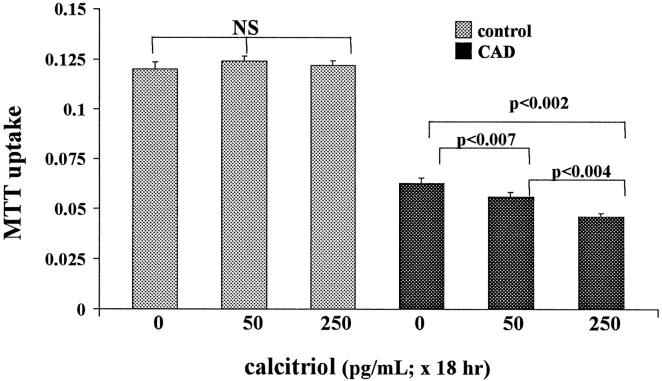

Exposing cells to calcitriol for 18 hours did not alter baseline HK-2 cell MTT uptake (Figure 1) ▶ . The 4-hour ATP depletion/Ca2+ ionophore challenge reduced cellular MTT uptake to 53% of baseline values (CAD in Figure 1 ▶ is calcium ionophore plus antimycin plus deoxyglucose). Calcitriol modestly, but highly significantly, exacerbated these CAD-mediated MTT declines (from 53% without calcitriol to 45% and 37% with 50 and 250 pg/ml calcitriol, respectively; Figure 1 ▶ ).

Figure 1.

Calcitriol effects on HK-2 cell MTT uptake under basal conditions and after 4 hours of ATP depletion/Ca2+ ionophore exposure. CAD, calcium ionophore plus antimycin plus 2-deoxyglucose. Calcitriol exposures were 0, 50, and 250 pg/ml for 18 hours before the CAD challenge. Under basal conditions, calcitriol had no effect on MTT uptake; however, it induced slight, but highly significant, reductions in MTT uptake after CAD exposure (consistent with an increase in CAD-mediated cytotoxicity).

Eighteen-Hour Pretreatment/Sixteen-Hour Challenge

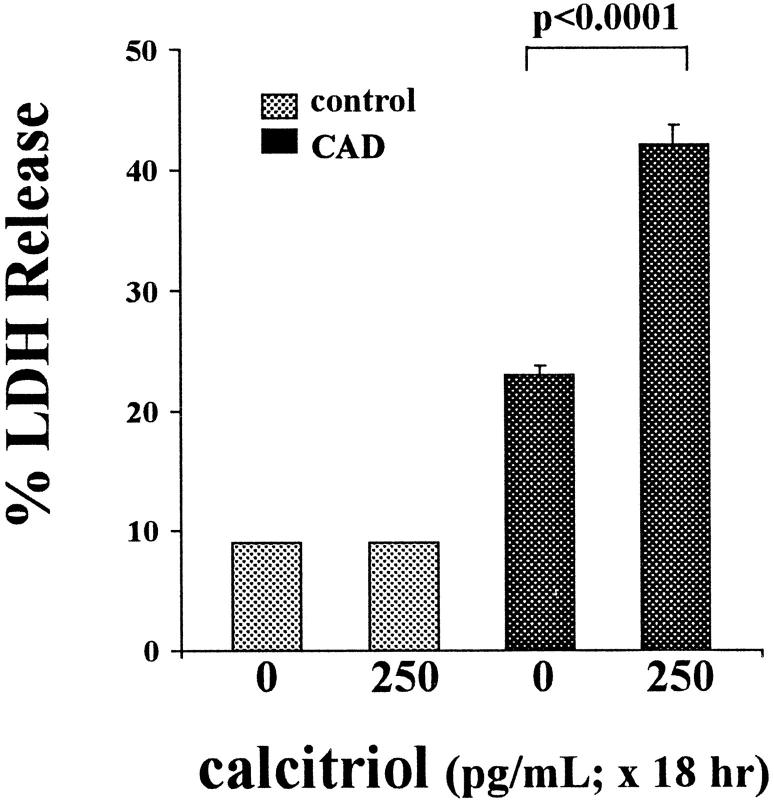

As shown in Figure 2 ▶ , 250 pg/ml calcitriol did not alter baseline percent LDH release. The CAD challenge modestly increased percent LDH release in control cells. This injury was approximately doubled by calcitriol treatment (P < 1 × 10−6).

Figure 2.

Calcitriol effects on ATP depletion/Ca2+ ionophore injury (CAD for 16 hours), as assessed by percent LDH release. Calcitriol exposure (250 pg/ml for 18 hours) did not independently alter percent LDH release. However, in the presence of the CAD challenge, it doubled LDH release, consistent with an exacerbation of CAD-mediated cell death.

Thirty-Hour Pretreatment/Sixteen-Hour Challenge

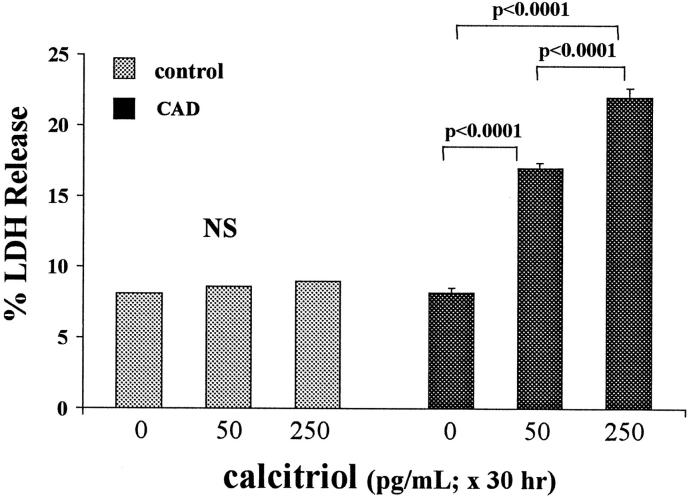

Calcitriol treatment for 30 hours did not affect baseline percent LDH release. However, this treatment caused a dose-dependent increase in cellular susceptibility to CAD-mediated injury, as assessed by LDH release (Figure 3) ▶ .

Figure 3.

ATP depletion/Ca2+ ionophore (CAD × 16 hours) injury: effects of 30-hour calcitriol exposure. In contrast to the Figure 2 ▶ (18-hour) experiments, in these experiments cells were exposed to 0, 50, or 250 pg/ml calcitriol for 30 hours, and then cellular susceptibility to injury was assessed. Calcitriol induced dose-dependent increases in CAD-mediated LDH release without independently affecting LDH release.

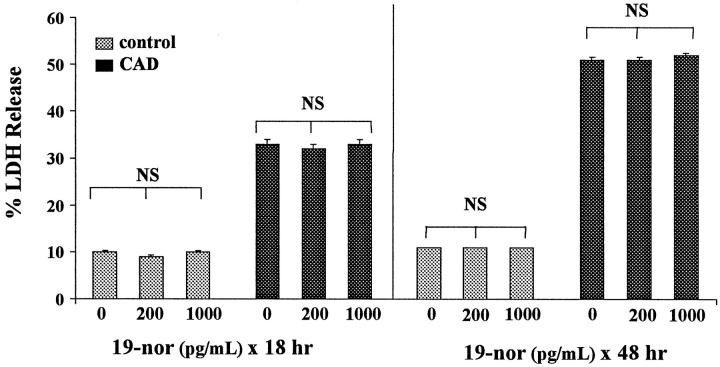

19-Nor Effects on the Expression of ATP Depletion/Ca2+ Overload Injury

Eighteen-Hour 19-Nor Pretreatment/Four-Hour CAD Challenge

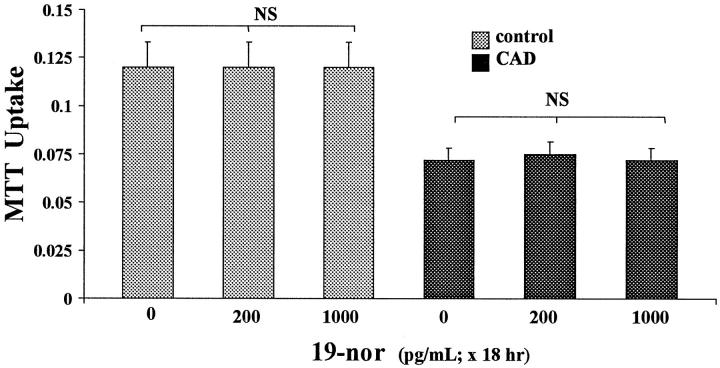

19-Nor did not affect cellular MTT uptake under control conditions (Figure 4) ▶ . Unlike the findings with calcitriol, 19-nor did not alter cellular susceptibility to the CAD challenge, with ∼40% decrements in MTT uptake occurring irrespective of 19-nor treatment.

Figure 4.

Effects of 19-nor on ATP depletion/Ca2+ ionophore (CAD for 4 hours) mediated injury, as assessed by MTT assay. These experiments recapitulated those shown in Figure 1 ▶ , except for substituting bio-equivalent doses of 19-nor for calcitriol. Unlike calcitriol, 19-nor had no impact on CAD-mediated reductions in MTT uptake.

Eighteen-Hour 19-Nor Pretreatment/Sixteen-Hour CAD Challenge

19-Nor did not influence baseline LDH release (Figure 5 ▶ , left). Control cells subjected to the 16-hour CAD challenge manifested 33 ± 1% LDH release. Neither 200 nor 1000 pg/ml 19-nor exposure affected the extent of this CAD-mediated injury (Figure 5 ▶ , left).

Figure 5.

Effects of 19-nor on ATP depletion/Ca2+ ionophore (CAD for 16 hours) mediated injury, as assessed by percent LDH release. Exposing HK-2 cells to either 200 or 1000 pg/ml doses of 19-nor for either 18 or 48 hours failed to alter CAD-mediated injury.

Forty-Eight-Hour 19-Nor Pretreatment/Sixteen-Hour Challenge

As shown in Figure 5 ▶ , right, exposing cells to 19-nor for 48 hours also did not affect baseline percent LDH release. Despite these prolonged exposures, 19-nor, once again, failed to alter CAD-mediated injury.

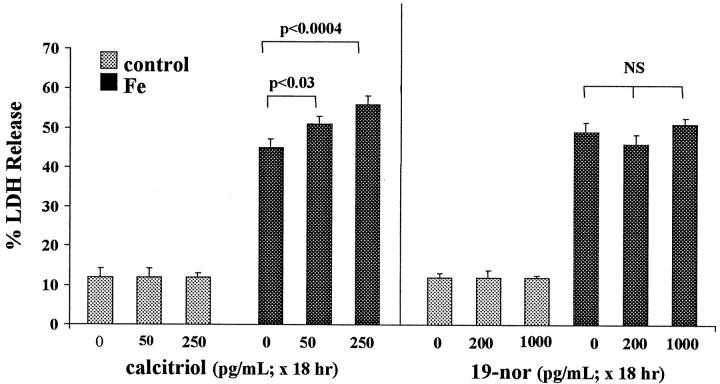

Vitamin D Effects on Fe-Mediated Cell Injury

Eighteen-Hour Calcitriol Pretreatment/Sixteen-Hour Fe Challenge

As shown in Figure 6 ▶ , left, Fe/HQ induced 45% LDH release over a 16-hour period. When cells were challenged with Fe/HQ in the presence of calcitriol, a modest, but highly significant, dose-dependent worsening of the Fe toxicity resulted (P < 0.0004 with the 250 pg/ml dosage). In the absence of the Fe challenge, calcitriol had no independent effect on percent LDH release.

Figure 6.

Calcitriol and 19-nor effects on 16 hours of iron-mediated HK-2 cell injury. Calcitriol exposure for 18 hours induced modest, but highly significant, dose-dependent increments in percent LDH release in response to Fe-mediated cell injury (left panel). In contrast, 18-hour 19-nor exposures had no injury-potentiating effect (right panel). Neither agent altered LDH release independent of the Fe challenge.

Eighteen-Hour 19-Nor Pretreatment/Sixteen-Hour Fe Challenge

Unlike calcitriol treatment, as discussed immediately above, 19-nor exposure for 18 hours had no effect on the extent of Fe-mediated LDH release/cell death (Figure 6 ▶ , right).

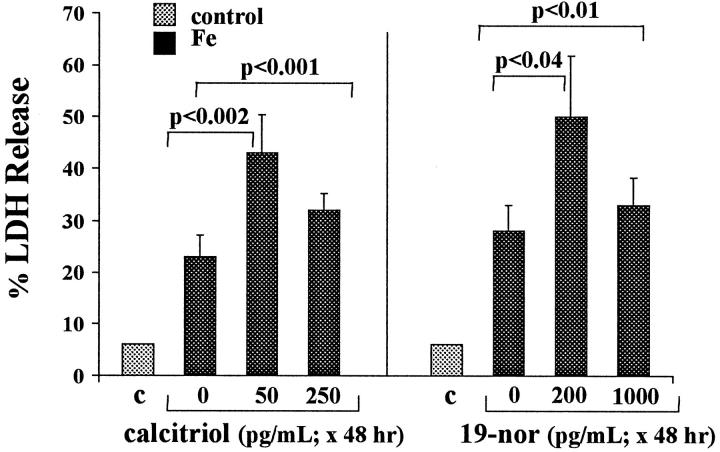

Forty-Eight-Hour Calcitriol Pretreatment/Sixteen-Hour Fe Challenge

As depicted in Figure 7 ▶ , left, exposing cells to 50 pg/ml calcitriol resulted in an approximate doubling of Fe/HQ-mediated LDH release. High dose (250 pg/ml) calcitriol also significantly increased Fe-mediated injury (P < 0.0001) but, paradoxically, to a lesser extent than did lower-dose calcitriol exposure. Calcitriol had no effect on percent LDH release in the absence of the Fe challenge (6 ± 0.5% LDH release; data not depicted).

Figure 7.

Iron-mediated HK-2 cell injury (for 16 hours): effects of 48-hour calcitriol or 19-nor exposure. These experiments were analogous to those in Figure 6 ▶ , except that the cells were exposed to calcitriol or 19-nor for 48 hours (rather than 18 hours) before Fe addition. The results differed from those presented in Figure 6 ▶ in two respects: 1) 19-nor, as well as calcitriol, exacerbated Fe-mediated injury; and 2) the lower vitamin D dosages (50 pg/ml calcitriol; 200 pg/ml 19-nor) exerted greater injury-promoting effects than did the higher calcitriol/19-nor doses (200 and 1000 pg/ml, respectively).

Forty-Eight-Hour 19-Nor Pretreatment/Sixteen-Hour Fe Challenge

As shown in Figure 7 ▶ , right, when cells were exposed to 19-nor for 48 hours, it fully reproduced calcitriol’s ability to increase Fe-mediated injury. Again, as with calcitriol, greater injury was observed with low-dose versus high-dose 19-nor treatment. In the absence of the Fe challenge, 19-nor had no independent effect on percent LDH release (6 ± 0.5%; not shown).

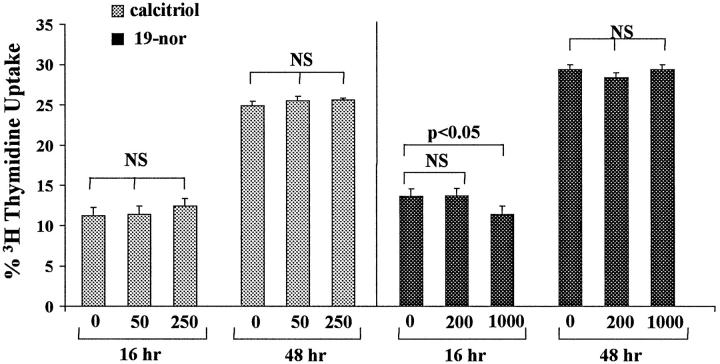

Calcitriol and 19-Nor Effects on HK-2 Cell Proliferation

[3H]Thymidine Uptake

Cells incubated in the absence of calcitriol for 18 and 48 hours manifested 11 ± 1% and 25 ± 0.2% [3H]thymidine uptake. Calcitriol therapy did not alter these results (Figure 8 ▶ , left). The 1000 pg/ml 19-nor treatment for 18 hours caused a slight decrease in [3H]thymidine uptake (from 13% to 11%; P < 0.05). However, these results were not sustained after 48 hours (Figure 8 ▶ , right). Furthermore, the 200 pg/ml 19-nor dose exerted no anti-proliferative effect.

Figure 8.

HK-2 cell proliferation, as assessed by [3H]thymidine incorporation, in the presence of calcitriol or 19-nor. HK-2 cells were cultured for 16 or 48 hours with either calcitriol (0, 50, or 250 pg/ml; left panel) or with 19-nor (0, 200, or 1000 pg/ml), and then [3H]thymidine incorporation was assessed. Calcitriol had no effect on [3H]thymidine uptake under any of the test conditions, and 19-nor slightly suppressed [3H]thymidine uptake, but only with the 1000 pg/ml dose. This was only a transient effect, as after more prolonged (48 hours) exposure, 19-nor had no effect.

Crystal Violet

Neither calcitriol nor 19-nor altered HK-2 cell proliferation, as assessed by crystal violet staining (ODs, 0.381 ± 0.002, 0.387 ± 0.004, and 0.384 ± 0.003 for 0, 50, and 250 pg/ml calcitriol, respectively, and 0.326 ± 0.004, 0.325 ± 0.006, and 0.325 ± 0.01, for 0, 200, and 1000 pg/ml 19-nor, respectively). The validity of the crystal violet assay was established by an essentially perfect correlation (r 2 = 0.9998) between serial HK-2 cell dilutions and subsequent crystal violet staining values.

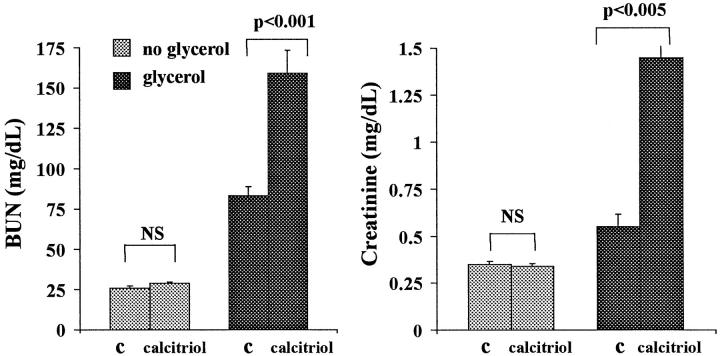

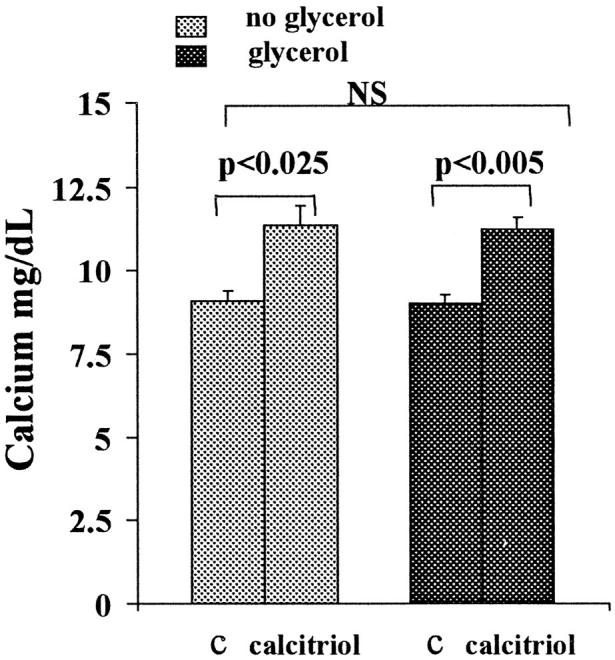

Calcitriol Effects on the Glycerol Model of ARF

As shown in Figure 9 ▶ , calcitriol in the absence of glycerol induced no change in BUN or plasma creatinine concentrations. However, it strikingly exacerbated the glycerol model of ARF (two- to threefold higher BUNs/creatinines with versus without calcitriol therapy). Calcitriol induced moderate, and comparable, degrees of hypercalcemia in control mice and glycerol-treated mice (Figure 10) ▶ , ranging from 9.7 to 12.4 mg/dl.

Figure 9.

Effects of single-dose calcitriol administration on normal mice and on mice subjected to concomitant glycerol administration. When administered to control (C) mice, calcitriol induced no increments in BUN or plasma creatinine concentrations. However, when administered at the time of glycerol administration, calcitriol caused two- to threefold BUN/creatinine increments (assessed 18 hours after glycerol with or without calcitriol therapy).

Figure 10.

Total plasma calcium concentrations in normal mice (left) and in glycerol-treated mice (right) (18 hours with or without calcitriol administration). Calcitriol induced modest, and essentially identical, degrees of hypercalcemia in normal and glycerol-treated mice. C, controls (ie, no calcitriol treatment).

Renal histology revealed typical changes of rhabdomyolysis- induced ARF, 41,44 consisting of proximal tubular necrosis (most prominent in the outer medullary stripes and medullary rays and to lesser degrees in the cortex) and prominent heme pigment cast formation. The sections were scored using a 0 to 5+ scale, as previously described. 44 Significantly worse morphological injury was observed in the glycerol/calcitriol D versus the glycerol control group (scores of 2.5 ± 0.2 versus 1.5 ± 0.2; P < 0.05; Wilcoxon rank sum test).

Isolated Tubule Experiments

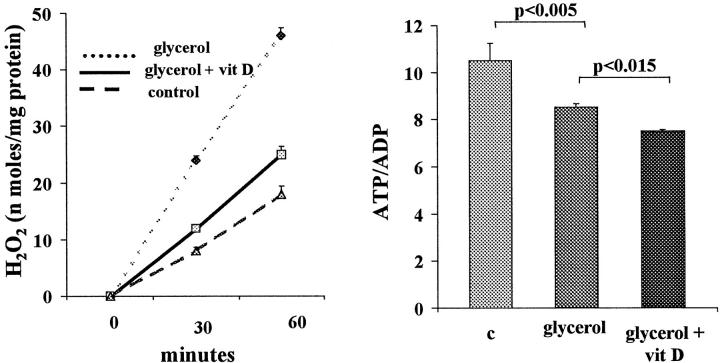

H2O2 Generation

Tubules harvested from glycerol-treated mice manifested brisk in vitro H2O2 generation (Figure 11 ▶ , left). Administration of calcitriol along with the glycerol decreased this H2O2 production by ∼80% (P < 0.005). Calcitriol had no effect on H2O2 production in non-glycerol-treated rats, essentially reproducing the values depicted in control tubules (Figure 11) ▶ .

Figure 11.

Effects of calcitriol administration on H2O2 production by isolated tubules and on cell energetics, assessed by tubule ATP/ADP ratios. Left panel: Tubules harvested from mice 2 hours after glycerol injection demonstrated brisk H2O2 production, compared with control tubules (harvested from normal mice). In vivo calcitriol (vit D) treatment at the time of glycerol injection markedly suppressed tubule H2O2 production. Right panel: Tubules harvested from glycerol-treated mice had significant depressions in ATP/ADP ratios (an indirect assessment of state 3 respiration). In vivo calcitriol (vit D) treatment caused a modest, but significant, accentuation of this ATP/ADP suppression.

ATP/ADP Ratios

As depicted in Figure 11 ▶ , right, glycerol-treated tubules had modest, but highly significant, reductions in ATP/ADP ratios, compared with control tubules. Calcitriol, administered in vivo, further suppressed these ratios, implying a further impairment in cellular energetics. In the absence of glycerol, calcitriol had no independent effect on ATP/ADP ratios (not depicted).

CPK Values

The plasma samples obtained at the time of harvesting tubules for the above experiments demonstrated marked CPK elevations after glycerol injection. However, the extent of this elevation was not affected by calcitriol therapy (glycerol plus calcitriol, 561 ± 192 U/ml; glycerol controls, 528 ± 161; normal mice, 22 ± 5; P < 0.025 versus both glycerol groups). Thus, the above differences in tubule function could not be ascribed to differences in the severity of glycerol-mediated in vivo muscle injury.

Phospholipid Assessments

As shown in Table 1 ▶ , calcitriol, in the absence of glycerol, induced ∼20% declines in total plasma membrane phospholipid (PC plus PI plus PE plus PS plus SM), compared with control tubules. These losses reflected declines in each of the phospholipids, except SM. Glycerol tubules (no calcitriol) manifested ∼20% losses of total phospholipids, compared with control tubules. These losses were expressed by PC, PS, PE, and PI but not SM (causing an increase in percent SM content). Calcitriol therapy significantly accentuated these glycerol-associated phospholipid declines.

Table 1.

Percentage of Individual Phospholipids and Total Plasma Membrane Phospholipid Content in Tubules Harvested from Normal and Glycerol-Treated Mice with or without Calcitriol Treatment

| Group | % SM | % PC | % PE | % PI | % PS | Total PL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls | 12.1 ± 1.1 | 44.6 ± 0.5 | 29.1 ± 0.9 | 7.2 ± 0.2 | 7.1 ± 0.5 | 201 ± 11 |

| Calcitriol | 13.5 ± 1.0 | 44.2 ± 1.9 | 28.1 ± 1.8 | 7.4 ± 0.4 | 6.8 ± 0.6 | 174 ± 11* |

| Glycerol | 17.2 ± 2.0 | 44.8 ± 1.9 | 23.2 ± 2.1 | 8.1 ± 0.8 | 6.7 ± 0.4 | 158 ± 11 |

| Glycerol + calcitriol | 17.3 ± 2.6 | 44.6 ± 1.7 | 23.7 ± 2.8 | 7.8 ± 0.7 | 6.7 ± 0.3 | 145 ± 11** |

Total phospholipid (PL; nmol phosphate/mg tubule protein) = the sum of each of the five dominant plasma membrane phospholipids presented. The percentage of each is calculated as a percentage of this total. In vivo calcitriol treatment (of non-glycerol-treated mice) caused ∼25% reduction in total phospholipid content (*p = 0.021). This was due to reductions in each of the phospholipids presented except SM. The increase in percent SM does not reflect an absolute increase in SM content. Rather, it represents the fact that the other phospholipids declined, thereby raising SM’s relative contribution to the total phospholipid mass. The glycerol model of tubule injury was associated with ∼20% reduction in total phospholipid (p < 0.01 vs. control tubules). This was due to losses in each of the phospholipids except SM. This led to reciprocal increases in % SM content. Calcitriol further exacerbated these glycerol-associated phospholipid declines (**p = 0.036) due to losses of PC, PI, PE, and PS.

Percent LDH Release

After completing 60-minute incubations, control tubules manifested 15 ± 1% LDH release. In contrast, glycerol-treated tubules manifested 54 ± 2% LDH release over this same period (P < 0.0001). Calcitriol did not significantly alter this result (54 ± 4%), indicating that the above H2O2, ATP/ADP ratio, and phospholipid differences were not simply due to differences in the extent of lethal cell injury in the with or without calcitriol treatment groups.

Discussion

There have been several indications in the literature that alterations in calcium and phosphate homeostasis can alter the severity of ARF. As examples, inorganic phosphate infusions exacerbate HgCl2 and ischemic tubular injury in rats, 19 hypercalcemia potentiates hypoxic injury in isolated perfused kidneys, 21 and hypercalciuria can attenuate gentamicin-induced ARF. 23-25 There are multiple pathways by which changes in calcium and phosphate homeostasis might mediate such changes. These include alterations in the glomerular ultrafiltration coefficient (Kf)/renal hemodynamics, 45 increased cast formation, altered tubular nephrotoxin uptake, 23-26 induction of metastatic calcification, and, possibly, direct cytotoxic effects. 19,21 Another, and previously unexplored, possibility is that secondary changes in vitamin D expression might be involved. This hypothesis was suggested to us by the following experimental paradox: when hypercalciuria is induced by either oral calcium loading or parathyroidectomy, rats are protected against gentamicin nephrotoxicity 23-25 ; conversely, when hypercalciuria is created by calcitriol administration, a potentiation of gentamicin nephrotoxicity results. 18 As the first two interventions suppress calcitriol levels, whereas the latter obviously increases them, the possibility emerges that calcitriol directly increases tubular vulnerability to attack. A burgeoning experimental literature that indicates that vitamin Ds exert protean cellular homeostatic effects further suggests they might directly affect tissue damage.

To directly test this hypothesis, it was necessary to use a cell culture system to prevent secondary changes in serum calcium, phosphate, and PTH levels. Hence, HK-2 cells were exposed to either physiologically relevant or pharmacological doses of calcitriol for up to 48 hours, and then cell integrity was assessed in the presence and absence of superimposed injuries. Two highly divergent injury models were used (ATP depletion/Ca2+ overload and iron-mediated oxidant stress) to more fully gauge vitamin D’s impact.

The first noteworthy result of these studies was that even a pharmacological dose of calcitriol, by itself, had no discernible effect on HK-2 viability. Three sets of observations support this view. First, irrespective of the length, or dose, of calcitriol treatment, no increase in percent LDH release was observed, indicating an absence of direct cytolytic effects. Second, MTT uptake, an exquisitely sensitive marker of HK-2 viability, 29 was not suppressed by calcitriol exposure. And third, calcitriol had no effect on either [3H]thymidine incorporation or on the crystal violet assay. The latter are generally used as markers of cellular proliferation, not cell integrity. However, as cell injury generally decreases cell outgrowth, comparable cell numbers after 48-hour calcitriol exposures indicate an absence of overt cytotoxicity. As calcitriol is generally considered to be anti-proliferative, 6,7 it was surprising that no decrements in HK-2 cell numbers resulted. Whether this negative result is specific for HK-2 cells, or whether it has more generalized relevance for tubular epithelium, remains unknown. However, unpublished pilot observations from our laboratory indicating that 1 week of daily calcitriol therapy does not suppress renal growth in uni-nephrectomized rats lends credence to the present HK-2 cell results.

Despite the fact that the calcitriol exerted no direct cytotoxicity, in each experimental situation tested, it increased HK-2 cell susceptibility to superimposed attack. A number of points are noteworthy in this regard: 1) calcitriol exposure exacerbated both ATP depletion/Ca2+ overload- and iron-mediated cytotoxicity, suggesting a broad-based biological effect; 2) this phenomenon was confirmed after several different lengths of calcitriol exposure, indicating that it is not merely a transient biological event; 3) in most cases, the injury potentiation was dose dependent, suggesting possible pharmacological relevance; and 4) the increase in cell injury was confirmed using two different assays, MTT uptake and LDH release. Finally, it is noteworthy that many of these results were relatively calcitriol specific. For example, 19-nor completely failed to affect ATP depletion/Ca2+ overload injury, irrespective of dose or length of exposure. In further contrast to calcitriol, 19-nor exacerbated iron cytotoxicity only after prolonged (48-hour) exposures. Although the reason for the different calcitriol versus 19-nor effects remain unknown, they are not unexpected. For example, calcitriol and 19-nor have been reported to up-regulate and down-regulate the nuclear vitamin D receptor, respectively. 27 Hence, it is not surprising that they have different impacts on cell injury responses.

In the in vivo study of Cohen et al, 18 ∼7 days of combined calcitriol/gentamicin therapy was required before calcitriol’s injury-potentiating effect could be observed. In contrast, our present cell culture results indicate that vitamin D can, within hours, affect tubular cell injury responses. In an attempt to provide in vivo support for our in vitro data, mice were subjected to the glycerol model of ARF with or without calcitriol therapy. The glycerol model was selected because it recapitulates two important injury pathways explored in our cell culture experiments: iron-mediated oxidant stress, and Ca2+ overload/ATP depletion. 41 Within just 18 hours of glycerol injection, calcitriol induced an approximate two- to threefold increase in azotemia, and it significantly worsened histological damage. As modest hypercalcemia also resulted, we cannot exclude the possibility that the worsening of renal failure was not hypercalcemic dependent (eg, as was suggested by Cohen et al in their study of gentamicin-induced ARF 18 ). However, that the in vitro experiments clearly demonstrated that calcitriol exacerbates injury in a situation in which hypercalcemia is excluded certainly indicates that calcitriol’s injury-potentiating effect is not necessarily hypercalcemic dependent. That calcitriol induced a comparable degree of hypercalcemia in control mice and yet no azotemia resulted provides some indirect support for the possibility that calcitriol might exert direct in vivo injury-potentiating effects. At a minimum, the in vivo results are at least consistent with our in vitro experiments.

Given vitamin D’s protean effects of cellular homeostasis, it is currently impossible to state the precise subcellular mechanism(s) that underlie its injury-potentiating effect. However, a number of conclusions, and speculations, can be drawn.

First, although calcitriol can be anti-proliferative, this obviously can be dissociated from injury potentiation, as the latter was expressed in the complete absence of the former.

Second, despite the fact that calcitriol may enhance cell differentiation, the available data suggest that this, too, is an unlikely factor contributing to its effects on cell injury for the following reasons: 1) calcitriol did not noticeably change HK-2 cell phenotype (as observed by routine light microscopy as well as by pilot electron microscopy studies; not shown); 2) just 3 hours of calcitriol pretreatment was sufficient to potentiate iron-mediated cytotoxicity, seemingly too short an interval for a major differentiation response; and 3) calcitriol exacerbated cell injury in vivo, where proximal tubules already exist in a fully differentiated state.

Third, although calcitriol has been reported to enhance H2O2 generation/toxicity in macrophage/monocyte lines, 46,47 its ability to worsen tubular cell injury also appears to be dissociated from this property. This is based on the finding that calcitriol markedly suppressed, rather than stimulated, H2O2 production in isolated tubules harvested from glycerol-treated mice. It is noteworthy that the mitochondrion accounts for almost all free radical/H2O2 generation in the glycerol model of ARF. 37-39 Given that calcitriol suppressed ∼80% of tubule H2O2 production, it is virtually certain that this action had a mitochondrial basis.

Fourth, the finding that calcitriol suppressed ATP/ADP ratios in heme-loaded tubules further supports the third point above: that calcitriol can, either directly or indirectly, affect mitochondrial function. As ATP depletion can be critical to the pathogenesis of myohemoglobinuric ARF, 41 it is tempting to postulate that this finding might contribute to calcitriol’s pro-injury effect. However, arguing against this are that 1) the ATP/ADP ratio depressions were quite mild (only ∼15%) and 2) calcitriol exacerbated cell injury when mitochondrial performance was already maximally suppressed (due to antimycin A in the CAD challenge 30 ). Thus, calcitriol must contribute to some consequence of ATP depletion, not the severity of ATP depletion per se.

Fifth, although calcitriol can induce 20% to 50% increases in cytosolic Ca2+ levels above basal values, 48-50 an increase in cell Ca2+ levels during cell injury is a most unlikely explanation for the current results. This is based on the fact that during the ATP depletion/Ca2+ ionophore challenge, cytosolic Ca2+ levels increase by ∼600%. 30,31 Hence, a small increase in basal calcium levels would seemingly be irrelevant in the presence of maximal Ca2+ overload (ionophore-induced) cell injury. However, it remains possible that a basal increase in cytosolic calcium could have helped set the stage for increased cell susceptibility to subsequent superimposed injury (see below).

Sixth and finally, of the various hypotheses tested to date, the most compelling is that calcitriol in some way alters plasma membrane homeostasis, increasing its susceptibility to attack. It has previously been noted that vitamin Ds can stimulate degradation of a number of plasma membrane phospholipids. As examples, calcitriol can enhance phosphatidylinositol turnover in colonic epithelium, 50 induce losses of phospholipase A2 substrates in isolated hepatocytes, 51,52 and stimulate sphingomyelin breakdown, 53 each by as yet to be defined pathways. The present study provides the first demonstrations that 1) this same phenomenon can be stimulated by in vivo calcitriol therapy and that 2) the proximal tubular epithelium can be involved. The plasma membrane phospholipid decrements were observed in both the absence and presence of myohemoglobinuric tubular attack. Given that plasma membrane integrity is the ultimate arbiter of necrotic cell death, it is tempting to postulate that such a change could predispose tubular cells to superimposed injury. Key questions for future investigations are: 1) what the mechanisms for these phospholipid losses are, 2) whether the latter directly predispose to tubular cell death, and 3) whether concomitant generation of secondary phospholipid messengers (eg, ceramide and phosphoinositides) are required. An intriguing possibility in regard to the first issue is that calcitriol might increase basal tubule cytosolic calcium levels, calcium-dependent PLA2 activation might result, and then the latter triggers the presently documented partial phospholipid depletion state. However, this remains only a working hypothesis at the present time.

In conclusion, the present investigations offer the following new insights. 1) Vitamin D(s) can directly affect tubular cell injury responses. This can occur independent of changes in serum Ca2+ phosphate and PTH levels (given that this phenomenon can be documented in a highly controlled cell culture system). 2) Not all vitamin Ds are equivalent in this regard (as calcitriol had a much more fully expressed injury-potentiating effect than did 19-nor). 3) Calcitriol’s ability to intensify acute tubular injury appears to be expressed despite its capacity to suppress iron-driven mitochondrial H2O2 generation. 4) An intensification of plasma membrane injury/phospholipid losses appear likely to be involved. These potential effects may need to be considered as new therapeutic uses are sought for calcitriol and new vitamin D/vitamin D analogues.

Acknowledgments

I thank Ms. Kristin Burkhart, Ms. Ali Johnson, Mr. Benjamin Sacks, and Ms Linda Risler for their expert technical assistance with this project.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Dr. Richard A. Zager, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, 1100 Fairview Avenue North, Room D2–190, P.O. Box 19024, Seattle, WA 98109-1024. E-mail: dzager@fhcrc.org.

Supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (RO-1 DK 38432–11 and DK 54200–1).

References

- 1.DeLuca HF, Zierold C: Mechanisms and functions of vitamin D. Nutr Rev 1998, 56:S4-S10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stumpf WE, Sar M, DeLuca HF: Sites of action of 1,25 (OH)2 vitamin D3 identified by thaw-mount autoradiography. Cohn DV Talmage RV Mathews JL eds. Hormonal Control of Calcium Metabolism. 1981, :pp 22-229 Exerpta Medica Amsterdam, The Netherlands [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stumpf WE, Sar M, Reid FA, Tanaka Y, DeLuca HF: Target cells for 1,25 (OH)2-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in intestinal tract, stomach, kidney, skin, pituitary, and parathyroid. Science 1979, 206:1188-1190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abe E, Miyaura C, Sakagami H, Takeda M, Konno K, Yamazaki T, Yoshiki S, Suda T: Differentiation of mouse myeloid leukemia cells induced by 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1981, 78:4990-4994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tanaka H, Abe E, Miyaura C, Kuribayashi T, Konno K, Nishii Y, Suda T: 1α,25-Dihydroxycholecalciferol and a human myeloid leukaemia cell line (HL-60). Biochem J 1982, 204:713-719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dokoh S, Donaldson CA, Haussler MR: Influence of 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin Ds on cultured osteogenic sarcoma cells: correlation with the 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 receptor. Cancer Res 1984, 44:2103-2109 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eisman JA, Martin TJ, MacIntyre I: 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 receptors in cancer. Lancet 1980, 1:1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manolagas SC, Hustmyer FF, Yu X-P: 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 and the immune system. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 1989, 191:238-245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang S, Smith C, DeLuca HF: 1α,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 and 19-nor-1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D2 suppress immunoglobinulin production and thymic lymphocyte proliferation in vivo. Biochem Biophys Acta 11993, 158:269-286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang S, Smith C, Prahl JM, Luo X, De Luca HF: Vitamin D deficiency suppresses cell-mediated immunity in vivo. Arch Biochem Biophys 1993, 303:98-106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lemire JM, Ince A, Takashima M: 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 attenuates the expression of experimental lupus of MRL/l mice. Autoimmunity 1992, 12:143-148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwarz U, Amann K, Orth SR, Simonaviciene A, Wessels S, Ritz E: Effect of 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D3 on glomerulosclerosis in subtotally nephrectomized rats. Kidney Int 1998, 53:1696-1705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cantorna MT, Hayes CE, DeLuca HF: 1,25-Dihydroxycholecalciferol inhibits the progression of arthritis in murine models of human arthritis. J Nutr 1998, 128:68-72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cantorna MT, Hayes CE, DeLuca HF: 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 reversibly blocks the progression of relapsing encephalomyelitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996, 93:7861-7864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayes CE, Cantorna MT, DeLuca HF: Vitamin D and multiple sclerosis. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 1997, 216:21-27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mathieu C, Waer M, Rutgeerts O, Bouillon R: Activated form of vitamin D [1,25(OH)2D3] and its analogs are dose-reducing agents for cyclosporine in vitro and in vivo. Transplant Proc 1994, 26:3048-3049 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Veyron P, Pamphile R, Binderup L, Touraine J-L: New 20-epi-vitamin D3 analogs: immunosuppressive effects on skin allograft survival. Transplant Proc 1995, 27:450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen R, Johnson K, Humes HD: Potentiation of aminoglycoside nephrotoxicity by vitamin-D-induced hypercalcemia. Mineral Electrolyte Metab 1988, 14:121-128 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zager RA: Hyperphosphatemia: a factor that provokes severe experimental acute renal failure. J Lab Clin Med 1982, 100:230-239 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen DJ, Sherman WH, Osserman EF, Appel GB: Acute renal failure in patients with multiple myeloma. Am J Med 1984, 76:247-256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brezis M, Shina A, Kidrona G, Epstein FH, Rosen S: Calcium and hypoxic injury in the renal medulla of the perfused kidney. Kidney Int 1988, 34:186-194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levi M, Molitoris BA, Burke TJ, Schrier RW, Simon FR: Effects of vitamin D-induced hypercalcemia on rat renal cortical plasma membrane and mitochondria. Am J Physiol 1987, 252:F267-F275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bennett WM, Elliott WC, Houghton DC, Gilbert DN, DeFehr J, McCarron DA: Reduction of experimental gentamicin nephrotoxicity by dietary calcium loading. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1982, 22:508-512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quarum ML, Houghton DC, Gilbert DN, McCarron DA, Bennett WM: Increasing calcium moderates experimental gentamicin nephrotoxicity. J Lab Clin Med 1984, 103:104-114 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bennett WM, Pulliam JP, Porter GA, Houghton DC: Modification of experimental nephrotoxicity by selective parathyroidectomy. Am J Physiol 1985, 249:F832-F835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sastrasinh M, Knauss JM, Weinberg JM, Humes HD: Identification of the aminoglycoside binding site in rat renal brush border membranes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1982, 222:350-359 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takahashi F, Finch JL, Denda M, Dusso AS, Brown AJ, Slatopolsky E: A new analog of 1,25 (OH)2D3, 19-nor-1,25 (OH)2D2 suppresses serum PTH and parathyroid gland growth in uremic rats without elevation of intestinal vitamin D receptor content. Am J Kidney Dis 1997, 30:105-112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin K, Gonzalez EA, M Gellens M, Hamm LL, Abboud H, Lindberg J: 19-Nor-1α-25-dihydroxyvitamin D2 (paricalcitol) safely and effectively reduces the levels of intract parathyroid hormone in patients on hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 1998, 9:1427-1432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ryan MJ, Johnson G, Kirk J, Fuerstenberg SM, Zager RA, Torok-Storb B: HK-2: an immortalized proximal tubule epithelial cell line from normal adult human kidney. Kidney Int 1994, 45:48-57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iwata M, Herrington JB, Zager RA: Protein synthesis inhibition induces cytoresistance in cultured proximal tubular (HK-2) cells. Am J Physiol 1995, 268:F1154-F1163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iwata M, Herrington J, Zager RA: Sphingosine: a mediator of acute renal tubular injury and subsequent cytoresistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1995, 92:8970-8974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Price P, McMillan TJ: Use of the tetrazolium assay in measuring the response of human tumor cells in ionizing radiation. Cancer Res 1990, 50:1392-1396 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zager RA, Burkhart K, Conrad D, Gmur DJ: Iron, heme oxygenase, and glutathione: mechanistic and therapeutic implications for myohemoglobinuric renal tubular injury. Kidney Int 1995, 48:1624-1634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zager RA, Conrad DS, Burkhart KM: Ceramide accumulation during oxidant renal tubular injury: mechanisms and potential consequences. J Am Soc Nephrol 1998, 9:1670-1680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anderson RJ, Ray CJ, Hattler BG: Retinoic acid regulation of renal tubular epithelial and vascular smooth muscle function. J Am Soc Nephrol 1998, 9:773-781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang YY, Olosfsoon M, Kopf I, Hultborn R: Growth and clonogenic assays compared for irradiated MCF-7 and Colo-205 cell lines. Anticancer Res 1998, 18:53-60 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zager RA: Mitochondrial free radical production induces lipid peroxidation during myohemoglobinuria. Kidney Int 1996, 49:741-751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zager RA, Burkhart K: Myoglobin toxicity in proximal human kidney cells: roles of Fe, Ca2+, H2O2, and terminal mitochondrial electron transport. Kidney Int 1997, 51:728-738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zager RA, Burkhart K: Decreased expression of mitochondrial derived H2O2 and hydroxyl radical in cytoresistant proximal tubules. Kidney Int 1997, 52:942-952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nath KA, Balla G, Vercollotti GN, Balla J, Jacob HS, Levitt MD, Rosenberg ME: Induction of heme oxygenase is a rapid and protective response in rhabdomyolysis in the rat. J Clin Invest 1992, 90:267-270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zager RA: Rhabdomyolysis and myohemoglobinuric acute renal failure. Kidney Int 1996, 49:314-326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zager RA, Iwata M, Conrad DS, Burkhart K, Igarashi Y: Altered ceramide and sphingosine expression during the induction phase of ischemic acute renal failure. Kidney Int 1997, 52:60-70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Esko JD, Raetz CRH: Mutants of Chinese hamster ovary cells with altered membrane phospholipid composition. J Biol Chem 1980, 255:4474-4480 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zager RA, Foerder C, Bredl C: The influence of mannitol on myoglobinuric acute renal failure: functional, biochemical, and morphological assessments. J Am Soc Nephrol 1991, 2:848-855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Humes HD, Ichikawa I, Troy JL, Brenner BM: Evidence for a parathyroid hormone-dependent influence of calcium on the glomerular ultrafiltration coefficient. J Clin Invest 1978, 61:32-40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Polla BS, Bonventre JV, Krane SM: 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 increases the toxicity of hydrogen peroxide in the human monocytic line U937: the role of calcium and heat shock. J Cell Biol 1981, 107:373-380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Steinbeck MJ, Kim JK, Trudeau MJ, Hauschka PV, Karnovsky MJ: Involvement of hydrogen peroxide in the differentiation of clonal HD-11EM cells into osteoclast-like cells. J Cell Physiol 1998, 176:574-487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baran DT, Milne ML: 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D increases hepatocyte cytosolic calcium levels: a potential regulator of vitamin D-25-hydroxylase. J Clin Invest 1986, 77:1622-1726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Desai SS, Appel MC, Baran DT: Differential effects of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 on cytosolic calcium in two human cell lines (HL-60 and U-937). J Bone Mineral Res 1986, 1:497-501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wali RK, Baum CL, Sitrin MD, Brasitus TA: 1,25(OH)2 vitamin D3 stimulates membrane phosphoinositide turnover, activates protein kinase C, and increases cytosolic calicum in rat colonic epithelium. J Clin Invest 1990, 85:1296-1303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baran DT, Sorensen M, Honeyman TW: Rapid action of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 on hepatocyte phospholipids. J Bone Mineral Res 1988, 3:593-600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Baran DT, Kelly AM: Lysophosphatidylinositol: a potential mediator of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D-induced increments in hepatocyte cytosolic calcium. Endocrinology 1988, 122:930-934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Okazaki T, Bielawska A, Domae N, Bell RM, Hannun YA: Characteristics and partial purification of a novel cytosolic, magnesium-independent, neutral sphingomyelinase activated in the early signal transduction of 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-induced HL-60 cell differentiation. J Biol Chem 1994, 269:4070-4077 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]