INTRODUCTION

The development of B lineage cells from haematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow to mature antibody-secreting plasma cells in peripheral lymphoid tissues is a complex and tightly regulated process. The proliferation and maturation of these cells occurs in response to numerous signals from the bone marrow microenvironment, soluble cytokines, interaction with antigen and T lymphocytes and the expression of specific gene products. Lymphocyte development, in both T and B lineages, begins with the commitment of multipotent progenitors to the lymphoid lineage. It is likely that these early stages are in part dependent upon extracellular and stromal signals, though the exact mechanisms of early lymphoid commitment are not well defined. The transcription factor Ikaros appears to play an important role in these initial stages, since mice with targeted deletions of the Ikaros gene lack T, B and natural killer cell development [1]. By contrast, the transcription factors E2A and EBF appear to be more B cell-specific, in that mice that are unable to express these genes have normal numbers of T cells and myeloid cells but few if any B lineage cells [2–4].

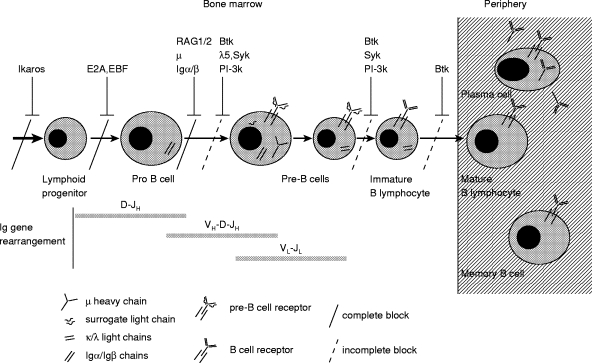

The earliest stages of normal B cell development are antigen-independent and occur in the bone marrow in response to stromal cell contact and cytokines. From the pre-B cell stage onwards, B cell development is dependent upon the successful assembly, and functional signalling through, pre-B and B cell receptor complexes. Central to this process is expression of the individual components of the receptor and also the molecules that transduce signals from the receptor to initiate cellular events. This is diagrammatically represented in Fig. 1. The understanding of this highly organized developmental pathway comes not only from in vitro data and the generation of transgenic mice but also from the study of naturally occurring human gene abnormalities. In this review we will outline the major gene defects that result in early B lymphocyte maturation arrest and detail the clinical manifestations and the molecular pathogenesis of these conditions. Considerable emphasis will be devoted to X-linked agammaglobulinaemia (XLA), since this is the most common abnormality of B cell development.

Fig. 1.

The stages of B lymphocyte development in the bone marrow and periphery are outlined. The most significant B cell developmental block most commonly seen in individuals with X-linked agammaglobulinaemia (XLA) is shown by a dashed line at the pro B cell to pre-B cell transition. However, there are also blocks at later stages as indicated by the dashed lines at the pre-B to immature B cell stage and at the immature to mature B lymphocyte stage. The knowledge from mouse studies and from individuals with congenital autosomal recessive agammaglobulinaemia has led to an understanding of the role of other genes in B cell development. The maturation arrest arising from abnormalities in these other genes is also demonstrated. A complete block at the pro to pre-B cell transition is seen in patients with μ heavy chain deficiency and in a patient with Igα deficiency.

X-linked agammaglobulinaemia

Clinical manifestations

XLA was the first human immunodeficiency described for which the clinical and laboratory findings dictated effective therapy. In 1952 Bruton reported the case of an 8-year-old boy who had suffered from recurrent infections and in whom analysis of serum by protein electrophoresis revealed no demonstrable gammaglobulin fraction [5]. The boy was treated with monthly intramuscular injections of human gamma globulin with significant clinical improvement. Although there was no family history in this initial case, subsequent cases revealed a similar clinical phenotype with an X-linked pedigree [6,7].

The phenotype of XLA is characterized in its classical form by the almost complete absence of immunoglobulin of all isotypes and the profound reduction of B lymphocytes in the peripheral cir‐culation. As a result the majority of affected boys are prone to recurrent bacterial infection from the age of approximately 4–12 months following the disappearance of maternal immunoglobulin [8]. However, in a significant number of cases (21% in a survey of 44 patients) onset of infections may occur later at 3–5 years of age [9].

The infections are usually caused by pyogenic bacteria, with Haemophilus influenzae, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Pseudomonas being the most common species [8], although mycoplasmas are a significant cause of arthritis [10,11]. The site of infection varies considerably, with sinusitis, otitis media and lower respiratory tract infections being the most common [8,9]. Resistance to viral infection remains predominantly intact except for a susceptibility to enteroviral infection which most commonly results in chronic meningoencephalitis or poliomyelitis in a significant number of cases [12]. Indeed, the major cause of mortality in the series reported by Hermaszewski & Webster [9] was as a result of enteroviral meningoencephalitis. The incidence of enteroviral disease in current populations of XLA patients appears to be less frequent, a finding which may be a result of improved clinical monitoring of patients and optimal immunoglobulin substitution therapy. The disease has always been considered to be confined to the B lymphocyte compartment; however, up to 25% of patients with XLA have profound neutropenia at the time of diagnosis [13]. This may be due to endotoxaemia following severe infections experienced by these patients, or it may be a reflection of the need for the XLA gene product in myeloid cells in situations of stress.

Heterogeneity of XLA

In 1993, the gene defective in XLA was identified and termed Btk (Brutons tyrosine kinase) [14,15]. This has had considerable impact on understanding the molecular pathogenesis of the condition (discussed below) but has clinically allowed unambiguous assignment of a molecular defect to individuals with abnormalities in antibody production. Thus, although the majority of Btk-deficient patients display the classical immunophenotype of less than 1% peripheral B lymphocytes and virtual absence of all immunoglobulin isotypes, a significant number of atypical or ‘leaky’ phenotypes have been identified, implying that XLA as a disease entity has considerable clinical and immunological heterogeneity. As many as 20% of patients with mutations in Btk have delayed onset of symptoms or higher concentrations of serum immunoglobulins than expected [16–20]. In addition, there appear to be differences in clinical severity, with some individuals with very low concentrations of serum immunoglobulins and almost no B cells having surprisingly few infective complications [19,21]. The reasons for clinical and immunological heterogeneity in XLA are unclear and may be dependent on factors other than the Btk defect.

Molecular basis of XLA

Btk was identified as the molecular defect in XLA by two groups, one using a positional cloning approach [15] and the other in a search for novel protein kinases expressed in B lymphocytes [14]. The gene is located on the long arm of the X chromosome at Xq21.3 and the human gene encompasses 37·5 kb. Btk is organized into 19 exons [22–25], including a 5′ untranslated region (exon 1), and encodes a 659 amino acid protein that is expressed throughout myeloid and B cell differentiation [26,27]. The Btk protein belongs to a family of cytoplasmic tyrosine kinases that are related to, but distinct from, the Src family kinases. The protein is characterized by its modular structure which includes an amino-terminal pleckstrin homology (PH) domain followed by a tec-homology (TH) domain, a Src homology SH3 domain, an SH2 domain and a carboxy-terminal kinase SH1 domain. Catalytic activity resides in the kinase domain while the other domains are necessary for protein–protein interactions. Other members of this family include Tec [28], Itk [29,30], and Bmx [31], all of which are also expressed in haematopoietic tissues.

Identification of the gene has led to mutational analysis being undertaken by a number of groups world wide. Over 500 unique mutations in Btk have now been identified and an international database of mutations and clinical information has now been established (BTKbase: http://http://www.uta.fi/laitokset/imt/bioinfo/BTKbase) [32–34]. Various different types of genetic abnormalities have been found in the Btk gene. One third of mutations are missense mutations and these have been found predominantly in the kinase domain of the gene, although they have been found in all domains except the SH3 domain [32,35]. Premature stop codons, deletions and insertions have also been described throughout the gene. Although the large majority of mutations are found in the coding region, 12% of mutations have been found to affect splice site recognition sequences [36]. Only one mutation has been found in the promoter region and this is thought to affect transcriptional regulation of the gene [37]. About 5–10% of mutations result in gross alterations of the Btk gene [38]. In addition to large deletions, an inversion, a duplication and a retroviral insertion have been identified.

Despite the large amount of mutation and phenotypic data available, it has not been possible to make definitive genotype–phenotype correlations. This is emphasized by reports of considerable variation in clinical severity within the same pedigree [17,21] showing that factors other than the genetic mutation may influence the clinical course. It has been suggested that, as in other immunodeficiencies [39], the presence of cytokine gene polymorphisms or defects in innate immunity such as mutations in mannan binding lectin may be important, but as yet there is no evidence to refute or confirm these ideas. It is also possible that environmental factors may play an important role. The consequence of the gene mutation on expression of the Btk protein and its relation to clinical severity has also been explored. However, it has been found that in the majority of individuals, despite the severity of the clinical phenotype and regardless of the nature of the mutation, there is complete lack of Btk expression [18,27,40]. It would appear that even carboxy-terminal amino acid substitutions render the mRNA and/or protein unstable.

Animal models of XLA

The consequences of mutations in Btk have also been studied in animal models of the disease. Soon after the identification of the defect in Btk in humans, the X-linked immunodeficiency (xid) mouse was found to have a single amino acid substitution (R28C) in the PH domain of Btk [41,42]. However, the immunophenotype of the xid mouse is very different from the human form. Xid mice have relatively normal serum concentrations of IgG1, IgG2a and IgG2b, but markedly reduced IgG3 and IgM concentrations. In addition, they are unable to make antibody responses to T cell-independent antigens but respond well to stimulation with T cell-dependent antigens [43]. The reduction in the number of B cells is also much less severe in xid mice compared with patients with XLA. While typical XLA patients have < 1% of the normal number of peripheral B cells, xid mice B cell numbers are only reduced to 30–50% of normal. In both species, defects in Btk are associated with an immature B cell phenotype, with the majority of B cells displaying an increased density of surface IgM [43,44]. The differences between the murine and human phenotypes cannot be explained by the nature of the xid genetic defect, since human R28C mutations with severe phenotypes have been described [36], and also Btk-null mice created by homologous recombination have a B cell phenotype that is identical to the xid mouse [45–47].

Btk function and its role in B cell development

Tyrosine kinases have been studied in many haematopoietic cell lineages and have been shown to act as signal transduction molecules mediating cell surface receptor activation events to downstream pathways. Cross-linking of a number of cell surface receptors including IL-5, IL-6, CD38, FcRε and perhaps most importantly surface IgM on B cells, results in the recruitment of cytosolic Btk to the plasma membrane and activation of Btk by tyrosine phosphorylation [48]. Migration of Btk to the cell membrane is dependent upon an intact PH domain and its association with PIP3 (phosphatidyl inositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate) [49,50]. The process of Btk activation is initiated by phosphorylation of tyrosine 551 (Tyr551) in the kinase domain of Btk by a Src family kinase, most likely lyn or fyn, followed by Btk autophosphorylation at tyrosine 223 (Tyr223) in the SH3 domain [51–53]. At the cell membrane activated Btk interacts with phospholipase gamma (PLCγ), leading to enhanced tyrosine phosphorylation of PLCγ and resulting in accumulation of inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) and mobilization of extracellular calcium. This pathway has been well defined by in vitro models [54,55] and is supported by evidence from Btk-deficient cell lines which show reduced phosphorylation of PLCγ and decreased calcium mobilization [56,57]. Other biochemical consequences of Btk activation include co-immunoprecipitation with, and phosphorylation of a protein termed BAP (Btk associated protein)-135 [58]. This protein has been independently identified as the DNA binding protein TFII and thus links Btk with regulation of transcriptional events [59,60].

Despite the large volume of biochemical and signalling data available, the central question of why the Btk gene defect results in B cell development arrest remains unresolved. There is however evidence that B cell receptor (BCR) expression and signalling is necessary for positive selection of B cells and prevention of death by apoptosis. Xid mice exhibit a progressive loss of splenic and recirculating B cells [61]. Moreover, some of the xid defects can be rescued by over-expression of the anti-apoptotic proteins Bcl-2 and BclXL[62,63]. This, together with evidence for Btk in regulation of BclXL expression, suggests that Btk may be important in mediating anti-apoptotic signals during crucial stages of B cell development [64].

Autosomal recessive agammaglobulinaemia

The majority of patients with congenital agammaglobulinaemia and absent B cells have defects in Btk. However, it has been well recognized that there are females who display a similar clinical and immunological profile [65,66], and there are pedigrees in which males and females have early onset hypogammaglobulinaemia and absent B cells. It is therefore likely that autosomally coded genes are sometimes responsible for this disorder. The incidence of these abnormalities is difficult to estimate. In a study of a large cohort of boys with presumed XLA, 90–95% had mutations in Btk [36]. Most of the remaining patients had defects in other genes. When one includes XLA-type females it has been estimated that approximately 10% of agammaglobulinaemic syndromes are autosomally inherited.

Molecular basis for autosomal recessive agammaglobulinaemia

The molecular defects for three of the autosomally inherited forms have now been identified [67,68,69]. The first disorder was identified by a combination of a candidate gene approach and linkage analysis. It was assumed that the correct gene would be relatively specific to the B cell lineage and that it would be expressed early in B cell differentiation. Four genes that had been mapped to specific loci in the genome and encode proteins involved in signal transduction through the B cell or pre-B cell receptor were chosen as candidate genes: syk (a B cell signal transduction kinase); CD79a (also termed Igα, which is an essential component of the BCR); EBF (a transcription factor required for CD79a transcription), and μ immunoglobulin heavy chain. Linkage analysis in two consanguineous families showed that the defect colocalized to the μ heavy chain gene; therefore this gene was studied in greater detail.

Four different mutations from four families have been identified in the μ heavy chain gene on chromosome 14. In one family, there was a homozygous 75–100-kb deletion that included D-region genes, J-region genes, and the μ constant region gene. In two families, there was a homozygous base-pair substitution in the alternative splice site of the μ heavy chain gene. This mutation is thought to inhibit production of the membrane form of the μ-chain and produce an amino acid substitution in the secreted form. In addition, a patient previously thought to have XLA was found to have an amino acid substitution on one chromosome at an invariant cysteine and, on the other chromosome, a large deletion that included the μ heavy chain locus.

The identification of mutations in the μ heavy chain gene suggested the possibility that defects in other components of the B cell or pre-B cell receptor complex might result in a failure of B cell development. Therefore single strand conformation polymorphism (SSCP) analysis was used to screen for mutations in the surrogate light chain molecules (VpreB and λ5/14.1) and the signal transduction module (Igα/Igβ). A 5-year-old boy with a clinical phenotype of sporadic XLA was found to have two mutations in the λ5/14.1 gene; a non-sense mutation in exon 1 of the maternally derived allele and an amino acid substitution in exon 3 of the paternally derived allele [68]. A homozygous splice defect that resulted in the deletion of the transmembrane domain of Igα was found in a 2-year-old Turkish girl with absent B cells [69].

Clinical and immunological profile

The numbers of patients with the autosomally inherited conditions are too small at present to make definitive statements on differences in clinical phenotype between these patients and those with XLA. However, anecdotal evidence suggests that females with congenital agammaglobulinaemia may have a more severe disease than XLA boys. Of the seven patients with μ deficiency, the mean age of presentation was 11 months compared with 32 months for patients with XLA. In addition, six of seven patients had a life-threatening infection and four suffered from chronic enteroviral encephalitis. The patient with λ5/14.1 had a history of otitis media from 2 months of age and the patient with Igα deficiency developed persistent diarrhoea and failure to thrive in the first month of life.

The stage of B cell differentiation arrest has also been studied in the four known human forms of congenital agammaglobulinaemia. Flow cytometric analysis of bone marrow showed that all four types had normal numbers of pro B cells expressing both CD34 and CD19 cell surface markers. However, CD19+CD34− pre B cells were completely absent in the patients with μ-chain or Igα deficiency and markedly reduced in number in patients with XLA or λ5/14.1 deficiency [67,68]. This highlights the importance of cell surface expression of the pre-B cell receptor and signalling through this complex in B cell development. Comparison of peripheral B cell numbers also shows that in XLA and λ5/14.1 deficiency 0·01–0·10% CD19+ cells can still be detected, whereas in μ-chain or Igα deficiency < 0·01% of peripheral lymphocytes are CD19+[67]. Functional analysis of the small peripheral B cell population from XLA patients shows that these cells proliferate and produce IgE in response to CD40 and IL-4 stimulation [70].

Other abnormalities in B cell development

There are still a number of individuals described who have a B cell development abnormality for whom no cause has been identified. Two groups have described female patients with a block in B lineage development at the early pro-B cell stage; however, despite extensive analysis of a number of genes necessary for B cell maturation, no specific molecular defect has been found [71,72]. The study of these unusual cases will further our understanding of normal B cell development. In addition to the pure B cell abnormalities, defects in B cell development are also seen in individuals with severe combined immunodeficiencies (SCID) due to recombinase activating gene (RAG) defects [73]. This is further detailed in a forthcoming review in this series.

Diagnostic tests for congenital agammaglobulinaemias

A pattern of X-linked inheritance, severely decreased numbers of peripheral B lymphocytes and decreased immunoglobulin production make a clinical diagnosis of XLA very likely. However, since approximately one third to one half of XLA cases are sporadic, alternative mechanisms of diagnosis are necessary. In addition, there is considerable heterogeneity to the XLA phenotype, as previously discussed, making a diagnosis based on clinical and immunological criteria more difficult. Since the identification of Btk as the defective gene in XLA, mutation analysis can now provide an unambiguous molecular diagnosis and also offer the possibility of carrier assignment and prenatal diagnosis. In most laboratories, mutation analysis for XLA involves screening the 19 exons of the Btk gene in genomic DNA by one of many techniques, of which SSCP is the most commonly used; direct sequencing of the affected exon can then be undertaken. This can be a time-consuming and expensive procedure and a definitive diagnosis may take weeks to achieve. Furthermore, some mutations may not be detected by SSCP. Other screening techniques do exist but the sensitivities are not necessarily greater than SSCP.

Based on the findings that most mutations lead to lack of Btk expression, unambiguous diagnosis can now rapidly be made by examination of Btk protein expression in peripheral blood monocytes by either Western blot or FACs analysis. In the FACs studies, 40 of 41 patients were shown to lack Btk [40] and the diagnosis was made in 10 individuals in whom no previous genetic data were available. In our own experience, 28 of 30 patients had abnormal expression by Western blot analysis, the majority completely lacking expression but two cases showing the presence of abnormally sized protein ([74] and unpublished observations). In our immunodeficiency diagnostic service, the routine strategy is to screen initially by immunoblotting and then to refer abnormal findings for mutation analysis. Thus a rapid diagnosis can be established and SSCP analysis can be undertaken with greater confidence. If Btk expression is normal, clinical and immunological findings dictate when referral for genetic testing is appropriate. The FACs analysis assay also offers the possibility of carrier testing since monocytes from obligate carriers of patients with no Btk expression show a dual population of Btk-expressing and non-expressing cells [40].

In males who are thought to have XLA but in whom a mutation in Btk is not identified, and in females who are phenotypically similar to patients with XLA, it may be worthwhile screening for defects in the components of the B cell or pre-B cell receptor complex. This could be done by screening of candidate genes in genomic DNA or reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis of bone marrow to examine the expression of candidate genes. Flow cytometric analysis of marrow for expression of these molecules may also prove useful. Because these disorders are very rare, it is likely that only certain specialized laboratories will undertake this task.

Clinical management

The mainstay of treatment for all congenital agammaglobulinaemias regardless of molecular defect is immunoglobulin replacement therapy. In most clinics, replacement is given on a regular basis intravenously (IVIg), but difficulty with venous access in young children and ease of administration has led to some centres adopting subcutaneous administration (SCIg) as an alternative approach. Treatment aims to achieve serum IgG levels in the normal age-related range. For most patients this will involve a dose of approximately 0·4–0·6 gm/kg every 3–4 weeks. Some centres practice a ‘loading dose’ of 1 gm/kg at the initiation of therapy. Dose and frequency should be tailored to the trough levels of immunoglobulin and to clinical symptoms. Individuals who continue to have recurrent infective problems may need higher or more frequent doses. Once established on a regular regime, patients can be trained to self-cannulate and administer IVIg at home, leading to greater patient convenience.

Adverse reactions can be associated with the infusion of IVIg. This most commonly takes the form of headaches, nausea, vomiting, flushing and myalgia [75]. More severe symptoms such as chest pain and anaphylactoid reactions have been described but are rare. Thus IVIg should only be given under the supervision of experienced practitioners and patients on home therapy should be taught to recognize and manage such events.

Immunoglobulin preparations are prepared from cold alcohol fractionation of pooled human plasma. As with all blood product preparations, there is a risk of virus transmission, although the fractionation process is effective in removal and inactivation of most viruses. However, there has been transmission of hepatitis C after use of commercial preparations of IVIg [76,77] and this has now led to all companies adopting a second step in the manufacturing procedure to ensure virus inactivation.

Rapid subcutaneous infusion of immunoglobulin is an alternative method of administration that has many advantages. First used in combined variable immunodeficiency (CVID) adult patients [78], it is attractive in the paediatric population where regular venous access can be a difficult and traumatic process. SCIg allows ease of access and is more readily transferable to home administration. Preliminary data also suggest that there is no difference in the maintenance of optimal immunoglobulin levels [79]. The drawbacks are that only a limited volume of immunoglobulin can be administered in one infusion and thus the frequency of infusions has to be increased, especially in older children. In addition, concentrated intramuscular preparations are needed for SCIg therapy, which until recently had not undergone formal viral inactivation steps. With the development of a specific virus-inactivated subcutaneous preparation, there will be increasing use of this mode of immunoglobulin administration.

Despite the excellent clinical response of most patients to immunoglobulin replacement therapy, it is still important to monitor patients on a regular basis. It is recommended that trough immunoglobulin levels are monitored regularly (usually every 3 months) to ensure that optimal levels are maintained. Liver function tests should also be checked regularly so that any hepatitic illness due to viral transmission can be detected at an early stage. In our practice all children undergo a chest x-ray or chest computed tomography (CT) scan on a yearly basis, since non-symptomatic infections do occur and can lead to chronic changes. Early detection of such abnormalities can prevent further progression by optimizing replacement therapy or by use of prophylactic antibiotics.

Enteroviral disease, and especially chronic meningoencephalitis, remains the greatest danger to agammaglobulinaemic patients. No effective antiviral agents were previously available. However, pleconaril is an orally active broad-spectrum anti-picornaviral agent which has excellent penetration into the central nervous system and nasal epithelium. Studies have shown this to have significant activity against the common forms of enteroviral strains in both in vitro and in vivo murine models [80]. Its use has also been piloted in immunodeficient patients, but the results are not yet published.

Gene therapy for XLA is an attractive concept since only the B cell lineage needs to be targeted. Further, since carrier females show non-random X-inactivation in B cells [81,82], it would appear that there would be a survival advantage for corrected cells. However, there are concerns that unrestricted expression of Btk could have potentially tumorigenic effects [83] that would necessitate the development of more precise mechanisms of transgene regulation.

Patient information

A number of organizations in Europe and in the USA exist to support patients with all forms of primary immunodeficiencies and these may be of great help to patients with agammaglobulinaemia and their families. In addition, there is an International Patient Organization for Primary Immunodeficiencies (IPOPI) (http://http://www.ipopi.org/). A full list of international patient support groups can be found at this site. Web addresses for patient organizations in the UK and USA are given below:

Primary Immunodeficiency Association:

Immune deficiency Foundation:

References

- 1.Georgopoulos K, Bigby M, Wang JH, et al. The Ikaros gene is required for the development of all lymphoid lineages. Cell. 1994;79:143–56. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90407-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bain G, Maandag EC, Izon DJ, et al. E2A proteins are required for proper B cell development and initiation of immunoglobulin gene rearrangements. Cell. 1994;79:885–92. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90077-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhuang Y, Soriano P, Weintraub H. The helix-loop-helix gene E2A is required for B cell formation. Cell. 1994;79:875–84. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90076-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin H, Grosschedl R. Failure of B-cell differentiation in mice lacking the transcription factor EBF. Nature. 1995;376:263–7. doi: 10.1038/376263a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruton OC. Agammaglobulinemia. Pediatrics. 1952;9:722–7. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Good RA. Clinical investigations in patients with agammaglobulinemia. J Lab Clin Med. 1954;44:803–7. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Janeway CA, Apt L, Gitlin D. Agammaglobulinemia. Trans Assoc Am Physicians. 1953;66:200–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lederman HM, Winkelstein JA. X-linked agammaglobulinemia: an analysis of 96 patients. Med Baltimore. 1985;64:145–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hermaszewski RA, Webster AD. Primary hypogammaglobulinaemia: a survey of clinical manifestations and complications. Q J Med. 1993;86:31–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stuckey M, Quinn PA, Gelfand EW. Identification of Ureaplasma urealyticum (T-strain Mycoplasma) in patient with polyarthritis. Lancet. 1978;2:917–20. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)91632-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roifman CM, Rao CP, Lederman HM, Lavi S, Quinn P, Gelfand EW. Increased susceptibility to Mycoplasma infection in patients with hypogammaglobulinemia. Am J Med. 1986;80:590–4. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(86)90812-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McKinney REJ, Katz SL, Wilfert CM. Chronic enteroviral meningoencephalitis in agammaglobulinemic patients. Rev Infect Dis. 1987;9:334–56. doi: 10.1093/clinids/9.2.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farrar JE, Rohrer J, Conley ME. Neutropenia in X-linked agammaglobulinemia. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1996;81:271–6. doi: 10.1006/clin.1996.0188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsukada S, Saffran DC, Rawlings DJ, et al. Deficient expression of a B cell cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase in human X-linked agammaglobulinemia. Cell. 1993;72:279–90. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90667-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vetrie D, Vorechovsky I, Sideras P, et al. The gene involved in X-linked agammaglobulinaemia is a member of the src family of protein-tyrosine kinases. Nature. 1993;361:226–33. doi: 10.1038/361226a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saffran DC, Parolini O, Fitch HM, et al. Brief report: a point mutation in the SH2 domain of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase in atypical X-linked agammaglobulinemia. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1488–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199405263302104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bykowsky MJ, Haire RN, Ohta Y, et al. Discordant phenotype in siblings with X-linked agammaglobulinemia. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;58:477–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hashimoto S, Tsukada S, Matsushita M, et al. Identification of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (Btk) gene mutations and characterization of the derived proteins in 35 X-linked agammaglobulinemia families: a nationwide study of Btk deficiency in Japan. Blood. 1996;88:561–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kornfeld SJ, Good RA, Litman GW. Atypical X-linked agammaglobulinemia. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:949–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hashimoto S, Miyawaki T, Futatani T, et al. Atypical X-linked agammaglobulinemia diagnosed in three adults. Intern Med. 1999;38:722–5. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.38.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kornfeld SJ, Haire RN, Strong SJ, et al. Extreme variation in X-linked agammaglobulinemia phenotype in a three-generation family. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;100:702–6. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(97)70176-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hagemann TL, Chen Y, Rosen FS, Kwan SP. Genomic organization of the Btk gene and exon scanning for mutations in patients with X-linked agammaglobulinemia. Hum Mol Genet. 1994;3:1743–9. doi: 10.1093/hmg/3.10.1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rohrer J, Parolini O, Belmont JW, Conley ME. The genomic structure of human BTK, the defective gene in X-linked agammaglobulinemia. Immunogenetics. 1994;40:319–24. doi: 10.1007/BF01246672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohta Y, Haire RN, Litman RT, et al. Genomic organization and structure of Bruton agammaglobulinemia tyrosine kinase: localization of mutations associated with varied clinical presentations and course in X chromosome-linked agammaglobulinemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:9062–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.19.9062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sideras P, Muller S, Shiels H, et al. Genomic organization of mouse and human Bruton’s agammaglobulinemia tyrosine kinase (Btk) loci. J Immunol. 1994;153:5607–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith CI, Baskin B, Humire GP, et al. Expression of Bruton’s agammaglobulinemia tyrosine kinase gene, BTK, is selectively down-regulated in T lymphocytes and plasma cells. J Immunol. 1994;152:557–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Genevier HC, Hinshelwood S, Gaspar HB, et al. Expression of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase protein within the B cell lineage. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:3100–5. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830241228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mano H, Yamashita Y, Sato K, Yazaki Y, Hirai H. Tec protein-tyrosine kinase is involved in interleukin-3 signaling pathway. Blood. 1995;85:343–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heyeck SD, Berg LJ. Developmental regulation of a murine T-cell-specific tyrosine kinase gene, Tsk. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:669–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.2.669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamada N, Kawakami Y, Kimura H, et al. Structure and expression of novel protein-tyrosine kinases, Emb and Emt, in hematopoietic cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;192:231–40. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tamagnone L, Lahtinen I, Mustonen T, et al. BMX, a novel nonreceptor tyrosine kinase gene of the BTK/ITK/TEC/TXK family located in chromosome Xp22.2. Oncogene. 1994;9:3683–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vihinen M, Kwan SP, Lester T, et al. Mutations of the human BTK gene coding for bruton tyrosine kinase in X-linked agammaglobulinemia. Human Mutat. 1999;13:280–5. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1999)13:4<280::AID-HUMU3>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vihinen M, Belohradsky BH, Haire RN, et al. BTKbase, mutation database for X-linked agammaglobulinemia (XLA) Nucl Acids Res. 1997;25:166–71. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.1.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vihinen M, Brandau O, Branden LJ, et al. BTKbase, mutation database for X-linked agammaglobulinemia (XLA) Nucl Acids Res. 1998;26:242–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.1.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vihinen M, Iwata T, Kinnon C, et al. BTKbase, mutation database for X-linked agammaglobulinemia (XLA) Nucl Acids Res. 1996;24:160–5. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.1.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Conley ME, Mathias D, Treadaway J, Minegishi Y, Rohrer J. Mutations in btk in patients with presumed X-linked agammaglobulinemia. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62:1034–43. doi: 10.1086/301828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holinski FE, Weiss M, Brandau O, et al. Mutation screening of the BTK gene in 56 families with X-linked agammaglobulinemia (XLA): 47 unique mutations without correlation to clinical course. Pediatrics. 1998;101:276–84. doi: 10.1542/peds.101.2.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rohrer J, Minegishi Y, Richter D, Eguiguren J, Conley ME. Unusual mutations in Btk: an insertion, a duplication, an inversion, and four large deletions. Clin Immunol. 1999;90:28–37. doi: 10.1006/clim.1998.4629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Foster CB, Lehrnbecher T, Mol F, et al. Host defense molecule polymorphisms influence the risk for immune-mediated complications in chronic granulomatous disease. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:2146–55. doi: 10.1172/JCI5084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Futatani T, Miyawaki T, Tsukada S, et al. Deficient expression of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase in monocytes from X-linked agammaglobulinemia as evaluated by a flow cytometric analysis and its clinical application to carrier detection. Blood. 1998;91:595–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thomas JD, Sideras P, Smith CI, Vorechovsky I, Chapman V, Paul WE. Colocalization of X-linked agammaglobulinemia and X-linked immunodeficiency genes. Science. 1993;261:355–8. doi: 10.1126/science.8332900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rawlings DJ, Saffran DC, Tsukada S, et al. Mutation of unique region of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase in immunodeficient XID mice. Science. 1993;261:358–61. doi: 10.1126/science.8332901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wicker LS, Scher I. X-linked immune deficiency (xid) of CBA/N mice. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1986;124:87–101. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-70986-9_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Conley ME. B cells in patients with X-linked agammaglobulinemia. J Immunol. 1985;134:3070–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khan WN, Alt FW, Gerstein RM, et al. Defective B cell development and function in Btk-deficient mice. Immunity. 1995;3:283–99. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90114-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kerner JD, Appleby MW, Mohr RN, et al. Impaired expansion of mouse B cell progenitors lacking Btk. Immunity. 1995;3:301–12. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90115-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hendriks RW, de-Bruijn MF, Maas A, Dingjan GM, Karis A, Grosveld F. Inactivation of Btk by insertion of lacZ reveals defects in B cell development only past the pre-B cell stage. EMBO J. 1996;15:4862–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li T, Rawlings DJ, Park H, Kato RM, Witte ON, Satterthwaite AB. Constitutive membrane association potentiates activation of Bruton tyrosine kinase. Oncogene. 1997;15:1375–83. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hyvonen M, Saraste M. Structure of the PH domain and Btk motif from Bruton’s tyrosine kinase: molecular explanations for X-linked agammaglobulinaemia. EMBO J. 1997;16:3396–404. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.12.3396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fukuda M, Kojima T, Kabayama H, Mikoshiba K. Mutation of the pleckstrin homology domain of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase in immunodeficiency impaired inositol 1,3,4,5-tetrakisphosphate binding capacity. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:30303–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.48.30303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rawlings DJ, Scharenberg AM, Park H, et al. Activation of BTK by a phosphorylation mechanism initiated by SRC family kinases. Science. 1996;271:822–5. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5250.822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Park H, Wahl MI, Afar DE, et al. Regulation of Btk function by a major autophosphorylation site within the SH3 domain. Immunity. 1996;4:515–25. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80417-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wahl MI, Fluckiger AC, Kato RM, Park H, Witte ON, Rawlings DJ. Phosphorylation of two regulatory tyrosine residues in the activation of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase via alternative receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:11526–33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fluckiger AC, Li Z, Kato RM, et al. Btk/Tec kinases regulate sustained increases in intracellular Ca2+ following B-cell receptor activation. EMBO J. 1998;17:1973–85. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.7.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Scharenberg AM, El-Hillal O, Fruman DA, et al. Phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate (PtdIns-3,4,5-P3)/Tec kinase-dependent calcium signaling pathway: a target for SHIP-mediated inhibitory signals. EMBO J. 1998;17:1961–72. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.7.1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Takata M, Kurosaki T. A role for Bruton’s tyrosine kinase in B cell antigen receptor-mediated activation of phospholipase C-gamma 2. J Exp Med. 1996;184:31–40. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Genevier HC, Callard RE. Impaired Ca2+ mobilization by X-linked agammaglobulinaemia (XLA) B cells in response to ligation of the B cell receptor (BCR) Clin Exp Immunol. 1997;110:386–91. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1997.4581478.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yang W, Desiderio S. BAP-135, a target for Bruton’s tyrosine kinase in response to B cell receptor engagement. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:604–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.2.604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Grueneberg DA, Henry RW, Brauer A, et al. A multifunctional DNA-binding protein that promotes the formation of serum response factor/homeodomain complexes: identity to TFII-I. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2482–93. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.19.2482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Novina CD, Kumar S, Bajpai U, et al. Regulation of nuclear localization and transcriptional activity of TFII-I by Bruton’s tyrosine kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:5014–24. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.7.5014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Klaus GG, Holman M, Johnson LC, Elgueta KC, Atkins C. A re-evaluation of the effects of X-linked immunodeficiency (xid) mutation on B cell differentiation and function in the mouse. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:2749–56. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830271102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Solvason N, Wu WW, Kabra N, et al. Transgene expression of bcl-xL permits anti-immunoglobulin (Ig)-induced proliferation in xid B cells. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1081–91. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.7.1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Woodland RT, Schmidt MR, Korsmeyer SJ, Gravel KA. Regulation of B cell survival in xid mice by the proto-oncogene bcl-2. J Immunol. 1996;156:2143–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Anderson JS, Teutsch M, Dong Z, Wortis HH. An essential role for Bruton’s tyrosine kinase in the regulation of B-cell apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:10966–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.10966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hoffman T, Winchester R, Schulkind M, Frias JL, Ayoub EM, Good RA. Hypoimmunoglobulinemia with normal T cell function in female siblings. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1977;7:364–71. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(77)90070-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Conley ME, Sweinberg SK. Females with a disorder phenotypically identical to X-linked agammaglobulinemia. J Clin Immunol. 1992;12:139–43. doi: 10.1007/BF00918144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yel L, Minegishi Y, Coustan SE, et al. Mutations in the mu heavy-chain gene in patients with agammaglobulinemia. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1486–93. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199611143352003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Minegishi Y, Coustan SE, Wang YH, Cooper MD, Campana D, Conley ME. Mutations in the human lambda5/14.1 gene result in B cell deficiency and agammaglobulinemia. J Exp Med. 1998;187:71–77. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Minegishi Y, Coustan SE, Rapalus L, Ersoy F, Campana D, Conley ME. Mutations in Ig alpha result in a complete block in B cell development at the pre-B cell receptor checkpoint. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:1115–21. doi: 10.1172/JCI7696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nonoyama S, Tsukada S, Yamadori T, et al. Functional analysis of peripheral blood B cells in patients with X-linked agammaglobulinemia. J Immunol. 1998;161:3925–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.de-la-Morena M, Haire RN, Ohta Y, et al. Predominance of sterile immunoglobulin transcripts in a female phenotypically resembling Bruton’s agammaglobulinemia. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:809–15. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Meffre E, LeDeist F, de-Saint-Basile G, et al. A human non-XLA immunodeficiency disease characterized by blockage of B cell development at an early proB cell stage. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:1519–26. doi: 10.1172/JCI118943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Schwarz K, Gauss GH, Ludwig L, et al. RAG mutations in human B cell-negative SCID. Science. 1996;274:97–99. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5284.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gaspar HB, Lester T, Levinsky RJ, Kinnon C. Bruton’s tyrosine kinase expression and activity in X-linked agammaglobulinaemia (XLA): the use of protein analysis as a diagnostic indicator of XLA. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;111:334–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00503.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Stiehm ER. Human intravenous immunoglobulin in primary and secondary antibody deficiencies. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1997;16:696–707. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199707000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Healey CJ, Sabharwal NK, Daub J, et al. Outbreak of acute hepatitis C following the use of anti-hepatitis C virus-screened intravenous immunoglobulin therapy. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:1120–6. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8613001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bjorkander J, Fasth A, Widell A. Intravenous immunoglobulin and hepatitis C virus: the Scandinavian experience. Clin Ther. 1996;18(Suppl. B):73–82. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(96)80198-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gardulf A, Andersen V, Bjorkander J, et al. Subcutaneous immunoglobulin replacement in patients with primary antibody deficiencies: safety and costs. Lancet. 1995;345:365–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90346-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gaspar J, Gerritsen B, Jones A. Immunoglobulin replacement treatment by rapid subcutaneous infusion. Arch Dis Child. 1998;79:48–51. doi: 10.1136/adc.79.1.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pevear DC, Tull TM, Seipel ME, Groarke JM. Activity of Pleconaril against Enteroviruses. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:2109–15. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.9.2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Conley ME, Brown P, Pickard AR, et al. Expression of the gene defect in X-linked agammaglobulinemia. N Engl J Med. 1986;315:564–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198608283150907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fearon ER, Winkelstein JA, Civin CI, Pardol DM, Vogelstein B. Carrier detection in X-linked agammaglobulinemia by analysis of X-chromosome inactivation. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:427–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198702193160802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Li T, Tsukada S, Satterthwaite A, et al. Activation of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) by a point mutation in its pleckstrin homology (PH) domain. Immunity. 1995;2:451–60. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90026-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]