Abstract

To develop a new immunotherapy for Japanese cedar (Cryptomeria japonica; CJ) pollinosis, we evaluated the use of DNA immunization by inoculating mice with plasmid DNA encoding Cry j 1 as a CJ pollen major allergen (pCACJ1). Repeated intramuscular (i.m.) inoculation of BALB/c mice with pCACJ1 produced anti-Cry j 1 antibody responses, which were predominately of the immunoglobulin G2a (IgG2a) type. Furthermore, this inoculation suppressed immunoglobulin E (IgE) and IgG1 antibody responses to subsequent alum-precipitated Cry j 1 injections. Splenic T cells isolated from mice inoculated with pCACJ1 i.m. secreted interferon-γ (IFN-γ), but not interleukin (IL)-4, in vitro upon stimulation with Cry j 1 as well as with p277–288, a peptide corresponding to the T-cell epitope of Cry j 1. In contrast, inoculation of BALB/c mice with pCACJ1 by gene gun injection caused response predominantly of the IgG1 type, and enhanced production of anti-Cry j 1 IgE antibodies to subsequent alum-precipitated Cry j 1 injections. Splenic T cells isolated from pCACJ1-innoculated mice by gene gun injection secreted both IFN-γ and IL-4 in vitro, upon stimulation with Cry j 1 as well as with p277–288. These findings suggest that i.m. inoculation with pCACJ1 effectively elicits Cry j 1-specific T helper 1 (Th1)-type immune responses, resulting in inhibition of the IgE response to Cry j 1.

Introduction

Japanese cedar (Cryptomeria japonica; CJ) pollinosis is one of the most common immediate-type allergic diseases in Japan, with more than 10% of the population being affected. Two major allergens, Cry j 1 and Cry j 2, have been isolated from CJ pollen.1,2 Patients with CJ pollinosis have high levels of specific immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies and T-cell reactivity to Cry j 1 and/or Cry j 2.3,4

Cry j 1 is a basic glycoprotein with a molecular weight (MW) of 41–45 000.1 The five amino acid residues of the N-terminus of Cry j 1 are reported to be identical to those of the North American mountain cedar that belongs to the same plant order (Pines) as Japanese cedar.5 The cDNA of Cry j 1 has been cloned and the Cry j 1 sequences show some homology to the Amb a 1 and 2 family of genes for ragweed pollen allergens.6,7

At present, desensitization treatment for type-I allergic diseases is used as immunotherapy. This treatment involves the stepwise subcutaneous (s.c.) injection of the specific allergen in an escalating dose, such that the patients reach a state of immunological tolerance. The repeated injection of allergen over a long time-period is laborious and inconvenient, and it is therefore of great importance to establish a convenient, effective protocol for the prevention and treatment of CJ pollinosis.

DNA immunization is an attractive approach for the prevention and treatment of allergic diseases.8–13 Inoculation with plasmid DNA encoding an allergen induces long-lasting expression of recombinant allergens. The protein is processed and presented to CD8+ or CD4+ T cells in the context of major histocompatibility class I and class II molecules, respectively. CD4+ T cells can be polarized into T helper 1 (Th1) cells producing interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and interleukin (IL)-2, or into T helper 2 (Th2) cells producing IL-4, IL-5 and IL-10.14 The allergic reaction characterized by IgE responses to the allergen and activation of inflammatory cells is dependent on the help of allergen-specific Th2 cells. In general, IFN-γ produced by Th1 cells selectively inhibits the development and activation of Th2 cells.15,16 B-cell switching to IgE production is also prevented by IFN-γ.17 Induction of allergen-specific Th1 cells by inoculation with plasmid DNA suppresses the activity of Th2 cells, which could be promising for interfering with the allergic reaction.

To establish a convenient and effective protocol for the prevention and treatment of CJ pollinosis, we evaluated the use of a DNA immunization method. The favoured routes of injecting plasmid DNA are either intramuscular (i.m.) or intradermal (i.d.) inoculation by saline injection, or gene gun inoculation into skin. Several reports have indicated that i.m. or i.d. inoculation with plasmid DNA encoding allergens inhibits subsequent IgE responses to those same allergens.8–10 However, the effect of gene gun inoculation in allergic responses has not yet been elucidated. We inoculated BALB/c mice with plasmid DNA encoding Cry j 1 (pCACJ1) by both methods, and then examined the immune responses elicited to Cry j 1 and the effect on the Cry j 1-specific IgE response.

Materials and methods

Mice

Female BALB/c mice were purchased from Japan SLC Inc. (Shizuoka, Japan). They were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions until used in experiments at the age of 8–10 weeks.

Cell culture

293-T cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM; Nissui, Tokyo, Japan), supplemented with penicillin (100 U/ml; Life Technologies Inc., Rockville, MD), streptomycin (100 µg/ml; Life Technologies Inc.) and 10% fetal calf serum (FCS). Mouse T cells were enriched from pooled spleens of BALB/c mice using a nylon wool column (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd., Osaka, Japan). These cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Life Technologies Inc.), supplemented with penicillin, streptomycin and 10% FCS.

Antigens

Cry j 1 protein was isolated from CJ pollen by affinity chromatography using a monoclonal antibody (mAb) specific to Cry j 1 (mAb 065), as described previously.18,19 The peptide corresponding to residues 277–288 of Cry j 1, p277–288, was provided by Dr Kazuki Hirahara (Sankyo Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan).

Construction of pCACJ1 recombinant plasmid

To induce an immune response to Cry j 1 by plasmid DNA immunization, we constructed the plasmid pCACJ1 by ligation of XhoI–SmaI-digested Cry j 1 cDNA to the eukaryotic expression vector pCAGGS, which encodes the cytomegalovirus enhancer and chicken β-actin promoter.20 The coding region of Cry j 16 was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the primers 5′-CTGCTCGAGATGGATAATCCCATAGACAGCTGC-3′ (XhoI site underlined) and 5′-GATCCCGGGCTTCATCAACAACGTTTAGAGAG-3′ (SmaI site underlined). The PCR product was digested with XhoI and SmaI then subcloned into pCAGGS. The expression plasmid was provided by Dr Junichi Miyazaki (Osaka University Medical School, Osaka, Japan).

Transfection

Plasmids were transfected into 293-T cells by LIPOFECTAMINE™ reagent (Life Technologies Inc.), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were harvested 48 hr after transfection, after which the protein expression of Cry j 1 in the cells was examined by Western blotting.

Sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE) and Western blotting

Transfected cells were lysed in sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE) sample buffer containing 5% 2-mercaptoethanol. Each preparation was loaded into wells, and SDS–PAGE was performed in a 10% gel. For immunoblotting with Cry j 1, the electrophoretic transfer of proteins from gels to Immobilon™-P (Millipore, Bedford, MA) was performed. The transferred membranes were blocked with 5% skimmed milk in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 0·05% Tween-20, then incubated with rabbit anti-Cry j 1 immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies and then with peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech Ltd, Bucks., UK). The substrate reaction was developed by enhanced chemiluminescence using the ECL kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech Ltd) and detected by exposure on X-ray film.

Immunization

Inoculations were given i.m. using a 26-gauge needle that delivered 50 µg of plasmid DNA in 50 µl of normal saline to both the left and right femoral muscles, four times at weekly intervals (days 0, 7, 14 and 21). Gene gun inoculations were delivered to the depilated abdominal skin of anaesthetized mice using a Helios gene gun (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) at a helium discharge pressure of 300 pounds per square inch. Mice were inoculated with plasmid DNA two or three times at weekly intervals (days 0, 7 and 14), and each inoculation consisted of 0·75 mg of 1·0-micron gold beads coated with 1·0 µg of plasmid DNA.

To assess the IgE antibody response to Cry j 1, the mice were sensitized by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection with 5·0 µg of Cry j 1 adsorbed on 2 mg of aluminum hydroxide (Pierce, Rockford, IL), 6 weeks after the last inoculation with pCACJ1. Three weeks after sensitization, the mice were given a booster injection with 1·0 µg of Cry j 1 adsorbed on 2 mg of alum.

Measurement of mouse anti-Cry j 1 IgG, IgG1 and IgG2a antibodies

The IgG, IgG1 and IgG2a antibody responses to Cry j 1 were assayed using an indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Briefly, microtitre plates (MaxiSorp F96; Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) were coated with Cry j 1 (1·0 µg/ml) in carbonate buffer (pH 9·6) then blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Serum samples were diluted in PBS containing 0·05% Tween-20 and 1% BSA. The IgG, IgG1, or IgG2a bound to the Cry j 1 immobilized on the wells was detected using peroxidase-conjugated rat anti-mouse IgG, IgG1 or IgG2a antibodies (Zymed Laboratories, South San Francisco, CA). The substrate used for the peroxidase was ortho-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride (Zymed Laboratories), and the plates were read at 492 nm. The titres of anti-Cry j 1 IgG, IgG1 and IgG2a were estimated using mouse anti-Cry j 1 mAbs, S95 (IgG and IgG1) and S92 (IgG2a), as the reference antibodies, which were added at various concentrations to wells coated with Cry j 1, blocked with BSA and then treated using the same procedure described above.

Measurement of mouse anti-Cry j 1 IgE antibodies

The IgE antibody response to Cry j 1 was assayed by a fluorometric ELISA, as described previously.21 Briefly, microtitre plate (MaxiSorp F96; Nunc) wells were coated with 1·0 µg/ml of anti-mouse IgE mAb (Yamasa Shouyu Co., Tokyo, Japan) in carbonate buffer (pH 9·6) for 2 hr at 37°, then blocked with 1% BSA in PBS at room temperature for 2 hr. The plates were washed, and serially diluted serum was added to the wells for overnight incubation at 4°. After each plate was washed, biotinylated Cry j 1 (0·75 µg/ml) was added to the wells and the plates were incubated for 1 hr at room temperature. After another wash, the plates were incubated with β- d-galactosidase-conjugated streptavidin (Zymed Laboratories) for 1 hr at room temperature. After a final wash, 0·1 m m 4-methylumbelliferhl-β- d-galactoside (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) was added to each well, and the plates were then incubated for 2 hr at 37°. The enzyme reaction was stopped with 0·1 m l-glycine-NaOH (pH 10·2). Fluorescence intensity was read as fluorescence units (FU) by using a microplate fluorescence reader (Fluoroska; Flow Laboratories, McLeans, VA). The passive cutaneous anaphylaxis (PCA) titre of anti-Cry j 1 IgE was calculated on a standard curve generated for a reference serum of known PCA titre.

Cytokine assays

Splenic T cells were enriched from pCACJ1-inoculated mice 3 weeks after the last inoculation. The T cells (4 × 105) were co-cultured with mitomycin C-treated splenocytes (8 × 105) in 96-well flat-bottom plates in the presence or absence of Cry j 1 (5·0 µg/ml) or p277–288 (10 µg/ml). The culture supernatant was collected after 3 days and kept at − 20° until used. The IFN-γ and IL-4 levels were determined by ELISA with anti-IL-4 mAbs (11B and BVD6: PharMingen, San Diego, CA) and with anti-IFN-γ mAbs (R46A2 and XMG1·2, PharMingen).

Statistical analyses

Significance analysis of results obtained for various groups of mice was performed using the Student’s t-test. Probability values < 0·05 were considered significant.

Results

Inoculation i.m. with pCACJ1 induced Cry j 1-specific Th1 responses in mice

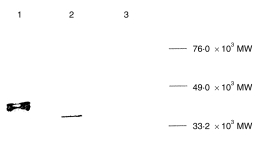

To induce immune responses to Cry j 1 by plasmid DNA inoculation, plasmid pCACJ1 was constructed by ligation of XhoI–SmaI-digested Cry j 1 cDNA to the pCAGGS mammalian cell-expression vector. Recombinant Cry j 1 was detected by anti-Cry j 1 IgG antibodies in the pCACJ1-transfected 293-T-cell lysate. In Western blotting analysis, native Cry j 1 showed multiple bands, as is generally observed with glycoproteins, and its MW was 41–45 000 (Fig. 1). In contrast, the recombinant Cry j 1 showed a single band, the MW of which was 39 000 (Fig. 1). The N-glycosylation pathway in mammals differs from that of plants; 22 therefore, the lower MW of recombinant Cry j 1 was probably a result of the difference in glycosylation patterns of Cry j 1 in mammalian cells.

Figure 1.

Western blot analysis of expressed Cry j 1. Lysates of the Cry j 1 transfectants and control were electrophoresed. Cry j 1 bands were detected using rabbit anti-Cry j 1 immunoglobulin G (IgG), as described in the Materials and methods. Lane 1, native Cry j 1; lane 2, lysate of pCACJ1-transfected 293-T cells; lane 3, lysate of pCAGGS-transfected 293-T cells. MW, molecular weight.

To determine whether inoculation with pCACJ1 caused an immune response against Cry j 1, BALB/c mice were inoculated i.m. with pCACJ1 in saline. As shown in Fig. 2, the IgG antibody response to Cry j 1 was detected in mice inoculated i.m. with 100 µg of pCACJ1 four times at weekly intervals, the response being maximal 36 days after inoculation with pCACJ1. In contrast, no Cry j 1-specific immune response was detected in mice inoculated with the parental expression vector pCAGGS (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Intramuscular (i.m.) inoculation with pCACJ1 mainly induced immunoglobulin G2a (IgG2a) antibody response to Cry j 1. BALB/c mice (n = 4) were inoculated i.m. with 100 µg of pCACJ1 four times (4 × i.m.) at weekly intervals. The anti-Cry j 1 IgG, IgG1 and IgG2a titres of pooled sera from mice on days 12 (open bars), 24 (hatched bars) and 36 (solid bars) after the last inoculation were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Data represent mean±SD of duplicate wells. The results are representative of three independent experiments. *IgG1 < 5·0 ng/ml.

In i.m.-inoculated mice, anti-Cry j 1 IgG2a production was predominant and IgG1 production was not observed (Fig. 2). Because IgG1 production is mediated by the Th2 response, and IgG2a production is mediated by the Th1 response,14 the results are compatible with the idea that i.m. inoculation of plasmid pCACJ1 causes a Th1 response to Cry j 1. To investigate this possibility, we enriched splenic T cells from mice inoculated with pCACJ1 and stimulated them in vitro with Cry j 1 or p277–288, a peptide corresponding to the dominant CD4+ T-cell determinant of Cry j 1.23 As shown in Table 1, splenic T cells secreted IFN-γ, a Th1-type cytokine, in the culture supernatant upon stimulation with Cry j 1 protein or a peptide antigen, but did not secrete IL-4, a Th2-type cytokine. As with previous observations, these findings suggest that i.m. inoculation of plasmid pCACJ1 to mice causes a Th1 response against Cry j 1, followed by an IgG2a antibody response.

Table 1.

Cytokines responses in pCACJ1-inoculated mice

| Cytokines | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Inoculation method* | In vitro stimulation | IFN-γ (U/ml) | IL-4 (pg/ml) |

| 4×i.m. | Cry j 1 | 185±51 | <4.0 |

| 4×i.m. | p277–288 | 227±15 | <4.0 |

| 2×g.g. | Cry j 1 | 134±37 | 27.1±6.7 |

| 2×g.g. | p277–288 | ND† | ND |

| 3×g.g. | Cry j 1 | 93.0±12 | 39.9±14 |

| 3×g.g. | p277–288 | 101±19 | 25.3±9.2 |

BALB/c mice (n = 4) were inoculated intramuscularly with 100 μg of pCACJ1 four times (4×i.m.) or with 1 μg of pCACJ1 by gene gun twice (2×g.g) or three times (3×g.g.) at weekly intervals.

Not determined.

IFN-γ, interferon-γ; IL-4, interleukin-4.

Gene gun inoculation of pCACJ1 induced Cry j 1-specific Th2 responses in mice

It has been reported previously that inoculation of plasmid DNA by gene gun produces preferentially Th2 responses in mice.24,25 Next, we examined Cry j 1-specific immune responses in BALB/c mice inoculated with pCACJ1 by gene gun. Inoculation of BALB/c mice with 1 µg of pCACJ1 two to three times by gene gun induced an IgG antibody response to Cry j 1. The level of IgG response in mice inoculated by gene gun twice was ≈ threefold higher than that in mice inoculated four times i.m. with 100 µg of the same plasmid (Fig. 3). Inoculation of pCACJ1 to mice by gene gun three times at weekly intervals enhanced the response in comparison with that for mice inoculated twice. No IgE antibody response to Cry j 1 was detected in mice inoculated with pCACJ1 by gene gun (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Gene gun inoculation with pCACJ1 mainly induced antibody response of the immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) type to Cry j 1. BALB/c mice (n = 4) were inoculated with 1 µg of pCACJ1 by gene gun twice (2 × g.g.) or three times (3 × g.g.) at weekly intervals. The anti-Cry j 1 IgG, IgG1 and IgG2a titres of pooled sera from mice on days 12 (open bars), 24 (hatched bars) and 36 (solid bars) after the last inoculation were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The data are presented as mean±SD of duplicate wells. The results are representative of three independent experiments. *IgG2a < 5·0 ng/ml.

In contrast to the response in mice inoculated i.m. with pCACJ1, the IgG antibody response was dominated by IgG1 antibodies in mice inoculated by gene gun, and the IgG2a antibody level against Cry j 1, when measurable, was ≈ 40-fold less than the level of IgG1 antibody (Fig. 3). Splenic T cells isolated from mice inoculated with pCACJ1 by gene gun secreted IFN-γ together with IL-4 upon stimulation in vitro with Cry j 1 or a peptide antigen (Table 1). These findings suggest that gene gun inoculation of pCACJ1 may induce Th1 responses against Cry j 1, but that the Th2 responses are predominant.

Inoculation i.m. with pCACJ1 inhibited the subsequent IgE response to Cry j 1

To determine whether the inoculation of pCACJ1 affects the subsequent IgE antibody response to Cry j 1, BALB/c mice were sensitized i.p. with alum-precipitated Cry j 1 6 weeks after inoculation with pCACJ1. Because a single sensitization did not elicit an IgE antibody response, mice were sensitized twice with the same antigen at 3-week intervals. They were bled 7 days after the last sensitization to estimate the IgE antibody response.

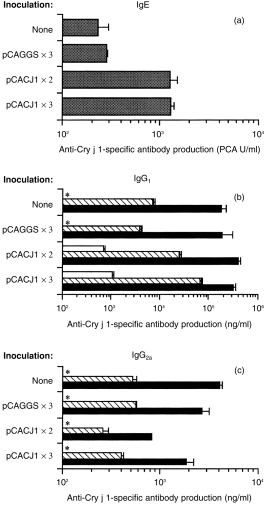

As shown in Fig. 4(a), the IgE antibody response to Cry j 1 was reduced in mice inoculated i.m. with pCACJ1 four times at weekly intervals, being six- to 10-fold less than that of the non-inoculated mice or pCAGGS-inoculated mice. Likewise, i.m. inoculation with pCACJ1 decreased the IgG1 antibody response to Cry j 1 14 days after the first sensitization, but the decrease became marginal after the second sensitization (Fig. 4b). In contrast, inoculation with pCACJ1 markedly enhanced the IgG2a response to Cry j 1 ≈ 10-fold over that of the control mice (Fig. 4c). These findings support the notion that i.m. inoculation with pCACJ1 suppresses the priming and/or activation of the Th2 cells in subsequent sensitization with Cry j 1, together with an enhancement of the Th1 response.

Figure 4.

Intramuscular (i.m.) inoculation with pCACJ1 inhibited the immunoglobulin E (IgE) and immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) responses to Cry j 1. BALB/c mice (n = 6) were inoculated i.m. with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or with 100 µg of pCAGGS or pCACJ1 four times at weekly intervals. Six weeks after the last inoculation, the mice were sensitized with 5 µg of Cry j 1 plus alum and given a booster of 1 µg of Cry j 1 plus alum 3 weeks after the sensitization. Anti-Cry j 1 IgE titre (a) of sera pooled from mice 7 days after the booster, or the anti-Cry j 1 IgG1 (b) and IgG2a (c) titres of sera pooled from mice on days 0 (open bars) and 14 (hatched bars) after the first sensitization, and on day 7 (solid bars) after the booster, were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The data are presented as mean±SD of duplicate wells. The results are representative of three independent experiments. *IgG1 < 5·0 ng/ml; IgG2a < 5·0 ng/ml. PCA, passive cutaneous anaphylaxis.

Gene gun inoculation with pCACJ1 enhanced the subsequent IgE response to Cry j 1

To examine the effect of inoculation with pCACJ1 by gene gun on subsequent antibody responses to Cry j 1, BALB/c mice were sensitized i.p. with alum-precipitated Cry j 1 6 weeks after inoculation with pCACJ1 by gene gun, two to three times at weekly intervals. As shown in Fig. 5(a), in contrast to the i.m. inoculation with pCACJ1, inoculation with the plasmid by gene gun resulted in an enhancement of IgE antibody formation in response to subsequent Cry j 1 injection, at an approximate maximum of 10-fold over the non-inoculated mice or pCAGGS-inoculated mice.

Figure 5.

Gene gun inoculation with pCACJ1 enhanced immunoglobulin E (IgE) and immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) antibody responses to Cry j 1. BALB/c mice (n = 6) were or were not inoculated with 1 µg of pCAGGS or pCACJ1 by gene gun two or three times at weekly intervals. Six weeks after the last inoculation, mice were sensitized with 5 µg of Cry j 1 plus alum and given a booster of 1 µg of Cry j 1 plus alum 3 weeks after sensitization. The anti-Cry j 1 IgE titre (a) of pooled sera from mice 7 days after the booster, or the anti-Cry j 1 IgG1 (b) and IgG2a (c) titres of sera from six mice on days 0 (open bars) and 14 (hatched bars) after the first sensitization, and on day 7 (solid bars) after the booster, were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The data are presented as mean±SD of duplicate wells. The results are representative of two independent experiments. *IgG1 < 5·0 ng/ml; IgG2a < 5·0 ng/ml. PCA, passive cutaneous anaphylaxis.

Likewise, gene gun inoculation with pCACJ1 enhanced the IgG1 antibody response to Cry j 1 14 days after the first sensitization with Cry j 1, but the enhancement became marginal after the second sensitization (Fig. 5b). In contrast, inoculation of mice twice with pCACJ1 decreased the IgG2a antibody response to Cry j 1, which was twofold less than that of the control animals, but inoculation with pCACJ1 three times did not affect the IgG2a antibody response (Fig. 5c). Owing to the preponderance of Th2-type over Th1-type immune responses, inoculation with pCACJ1 by gene gun must enhance IgE antibody responses to Cry j 1.

Discussion

In this study, we found that different inoculation methods of plasmid DNA had different abilities to suppress the CJ allergen-specific IgE response. The i.m. inoculation with pCACJ1 elicited Cry j 1-specific Th1-type immune responses, resulting in inhibition of the IgE response to Cry j 1. This finding indicated the potential for DNA immunization as a tool for the prevention and treatment of CJ pollinosis. It should be noted that gene gun inoculation of pCACJ1 predominantly induced the Th2 response and enhanced IgE formation in response to subsequent injection of Cry j 1. Therefore, DNA immunization by gene gun would be useful for suppression of Th1-mediated immune diseases, such as multiple sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis, but would promote the occurrence and symptoms of allergic diseases. To suppress allergic responses following DNA immunization with gene gun, the use of an adjuvant for promoting Th1 responses, such as IL-12, should be considered.

Some studies have reported that there is a difference between immune responses induced by i.m. and gene gun inoculation, which is agreement with our results.24,25 The difference in immune responses induced by the two methods can be explained by several factors, including antigen concentration, cytokine condition, or the type of antige-presenting cells (APC). In i.m. inoculation, cells acquire plasmid DNA from the extracellular spaces and the transfection rate is low. Gene gun inoculation directly transfects cells by depositing plasmid DNA-coated gold beads within the cell cytoplasm, which gives a high transfection rate. The difference in the level of expressed protein between the two methods would result in the differentiation of distinct types of CD4+ T cells. In fact, a predominant IgG1 response to Cry j 1 was observed in mice inoculated i.m. with pCACJ1 by in vivo electroporation, which is known to be a method of achieving high transfection rates and protein expression (data not shown).26

It was also reported that the unmethylated CpG motif in bacterial DNA induces the production of IL-12, IFN-α, IFN-β and IFN-γ by macrophages, dendritic cells, natural killer (NK) cells, B cells and T cells, which trigger Th1-type immune responses.27–30 The sequence AACGTT, in particular, possessed significant activity.31 Three such sites exist in the plasmid used in our study. Injection of large amounts of plasmid DNA containing the CpG motif by i.m. inoculation would induce adjuvant effects that promote Th1-cell responses. In gene gun inoculation, the plasmid DNA injection dose was probably insufficient to induce the adjuvant effect necessary for eliciting predominantly Th1 responses.

Different types of APC transfected by the two methods may influence the differentiation of CD4+ T cells. Porgador et al. indicated that directly transfected dendritic cells acted as APC to prime CD8+ T cells after gene gun inoculation.32 Several studies using parent-into-F1 bone marrow-reconstituted mice indicated that CD8+ T-cell responses induced by i.m. inoculation are initiated by bone marrow-derived APC.33,34 However, it has not yet been elucidated which type of APC prime CD4+ T cells, nor how endogenously synthesized proteins induce CD4+ T-cell responses. When information concerning the priming of CD4+ T cells is available, the precise mechanisms underlying the difference in immune responses can be elucidated.

The recombinant Cry j 1 in pCACJ1-transfected mammalian cells had a different MW from that of native Cry j 1 (Fig. 1). Cry j 1 possessing N-linked oligosaccharides with xylose and fucose structures are found only in plants.35,36 The lower MW of recombinant Cry j 1 was probably a result of the difference in glycosylation patterns of Cry j 1 in mammals. However, recombinant Cry j 1 had a T-cell epitope, and the splenic T cells isolated from pCACJ1-inoculated mice were able to respond to native Cry j 1 and peptide corresponding to the CD4+ T-cell epitope (Table 1). The important factor in the induction of allergen-specific Th1 cells is the CD4+ T-cell epitope site in the recombinant allergen. As long as an allergen expressed in mammalian cells by inoculated plasmid DNA has T-cell antigenicity, the induction of allergen-specific Th1 responses would be guaranteed.

Acknowledgments

We thank K. Notomi and K. Honda for technical assistance. We are grateful to Dr S. Tamura and Dr Z. Chen for their advice on the construction of plasmid DNA. This work was supported by a grant from the Agency for Science and Technology, Japan.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- CJ

Cryptomeria japonica

- i.d.

intradermal

- IFN

interferon

- IL

interleukin

- i.m.

intramuscular

- i.p.

intraperitoneal

- mAb

monoclonal antibody

References

- 1.Yasueda H, Yui Y, Shimizu T, Shida T. Isolation and partial characterization of the major allergen from Japanese cedar (Cryptomeria japonica) pollen. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1983;71:77. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(83)90550-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sakaguchi M, Inouye S, Taniai M, et al. Identification of the second major allergen of Japanese cedar pollen. Allergy. 1990;45:309. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.1990.tb00501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hashimoto M, Nigi H, Sakaguchi M, et al. Sensitivity to two major allergens (Cry j I and Cry j II) in patients with Japanese cedar (Cryptomeria japonica) pollinosis. Clin Exp Allergy. 1995;25:848. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1995.tb00027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sugimura K, Hashiguchi S, Takahashi Y, et al. Th1/Th2 response profiles to the major allergens Cry j 1 and Cry j 2 of Japanese cedar pollen. Allergy. 1996;51:732. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.1996.tb02118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taniai M, Ando S, Usui M, et al. N-terminal amino acid sequence of a major allergen of Japanese cedar pollen (Cry j I) FEBS Lett. 1988;239:329. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(88)80945-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sone T, Komiyama N, Shimizu K, et al. Cloning and sequencing of cDNA coding for Cry j I, a major allergen of Japanese cedar pollen. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;199:619. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Griffith IJ, Lussier A, Garman R, et al. cDNA cloning of Cry j I, the major allergen Cryptomeria japonica (Japanese cedar) J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1993;91:339. (no. 792) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsu CH, Chua KY, Tao MH, et al. Immuno-prophylaxis of allergen induced immunoglobulin E synthesis and airway hyperresponsiveness in vivo by genetic immunization. Nature Med. 1996;2:540. doi: 10.1038/nm0596-540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raz E, Tighe H, Sato Y, et al. Preferential induction of a Th1 immune response and inhibition of specific IgE antibody formation by plasmid DNA immunization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:5141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.10.5141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Slater JE, Colberg PA. A DNA vaccine for allergen immunotherapy using the latex allergen Hev b 5. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;99:S504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tighe H, Corr M, Roman M, Raz E. Gene vaccination: plasmid DNA is more than just a blueprint. Immunol Today. 1998;19:89. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)01201-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hartl A, Kiesslich J, Weiss R, et al. Immune responses after immunization with plasmid DNA encoding Bet v 1, the major allergen of birch pollen. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;103:107. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70533-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krishnendu R, Hai-quan M, Shau-ku H, Kam WL. Oral gene delivery with chitosan-DNA nanoparticles generates immunologic protections in a murine model of peanut allergy. Nature Med. 1999;5:387. doi: 10.1038/7385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mosmann TR, Coffman RL. TH1 and TH2 cells: different patterns of lymphokine secretion lead to different functional properties. Annu Rev Immunol. 1989;7:145. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.07.040189.001045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seder RA, Paul WE. Acquisition of lymphokine-producing phenotype by CD4+ T cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:635. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.003223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abbas AK, Murphy KM, Sher A. Functional diversity of helper T lymphocytes. Nature. 1996;383:787. doi: 10.1038/383787a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Snapper CM, Paul WE. Interferon-gamma and B cell stimulatory factor-1 reciprocally regulate Ig isotype production. Science. 1987;236:944. doi: 10.1126/science.3107127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawashima T, Taniai M, Taniguchi Y, et al. Antigenic analysis of Sugi basic protein by monoclonal antibodies, I. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1992;98:110. doi: 10.1159/000236173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawashima T, Taniai M, Usui M, et al. Antigenic analysis of Sugi basic protein by monoclonal antibodies, II. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1992;98:118. doi: 10.1159/000236174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Niwa H, Yamamura K, Miyazaki J. Efficient selection for high-expression transfectants with a novel eukaryotic vector. Gene. 1991;108:193. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90434-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sakaguchi M, Inouye S, Miyazawa H, Tamura S. Measurement of antigen-specific mouse IgE by a fluorometric reverse (IgE-capture) ELISA. J Immunol Methods. 1989;116:181. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(89)90202-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lerouge P, Cabanes MM, Rayon C, et al. N-glycoprotein biosynthesis in plants: recent developments and future trends. Plant Mol Biol. 1998;38:31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kingetsu I, Saito S. Identical recognition of T-cell epitopes by Th1 and Th2 subsets in mice immunized with Japanese cedar pollen antigens. Jikeikai Med J. 1998;45:95. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pertmer TM, Roberts TR, Haynes JR. Influenza virus nucleoprotein-specific immunoglobulin G subclass and cytokine responses elicited by DNA vaccination are dependent on the route of vector DNA delivery. J Virol. 1996;70:6119. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.9.6119-6125.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feltquate DM, Heaney S, Webster RG, Robinson HL. Different T helper cell types and antibody isotypes generated by saline and gene gun DNA immunization. J Immunol. 1997;158:2278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aihara H, Miyazaki J. Gene transfer into muscle by electroporation in vivo. Nature Biotechnol. 1998;16:867. doi: 10.1038/nbt0998-867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sonehara K, Saito H, Kuramoto E, et al. Hexamer palindromic oligonucleotides with 5′-CG-3′ motif(s) induce production of interferon. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 1996;16:799. doi: 10.1089/jir.1996.16.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klinmann DM, Yi AK, Beaucage SL, et al. CpG motifs present in bacteria DNA rapidly induce lymphocytes to secrete interleukin 6, interleukin 12, and interferon gammma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2879. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.2879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sparwasser T, Koch ES, Vablulas RM, et al. Bacterial DNA and immunostimulatory CpG oligonucleotides trigger maturation and activation of murine dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:2045. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199806)28:06<2045::AID-IMMU2045>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jakob T, Walker PS, Krieg AM, et al. Activation of cutaneous dendritic cells by CpG-containing oligodeoxynucleotides: a role for dendritic cells in the augmentation of Th1 responses by immunostimulatory DNA. J Immunol. 1998;15:3042. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roman M, Martin-orozco E, Goodman JS, et al. Immunostimulatory DNA sequences function as T helper-1 promoting adjuvants. Nature Med. 1997;3:849. doi: 10.1038/nm0897-849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Porgador A, Irvine KR, Iwasaki A, et al. Predominant role for directly transfected dendritic cells in antigen presentation to CD8+ T cells after gene gun immunization. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1075. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.6.1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Doe B, Selby M, Barnett S, et al. Induction of cytotoxic T lymphocytes by intramuscular immunization with plasmid DNA is facilitated by bone marrow-derived cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:8578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Corr M, Lee JD, Carson AD, Tighe H. Gene vaccination with naked plasmid DNA: mechanism of CTL priming. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1555. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.4.1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hino K, Yamamoto S, Sano O, et al. Carbohydrate structures of the glycoprotein allergen Cry j I from Japanese cedar (Cryptomeria japonica) pollen. J Biochem. 1995;117:289. doi: 10.1093/jb/117.2.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ogawa H, Hijikata A, Amano M, et al. Structures and contribution to the antigenicity of oligosaccharides of Japanese cedar (Cryptomeria japonica) pollen allergen Cry j I: relationship between the structures and antigenic epitopes of plant N-linked complex-type glycans. Glyco J. 1996;13:555. doi: 10.1007/BF00731443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]