Abstract

Certain heterocyclic N-oxides are vasodilators and inhibitors of platelet aggregation. The pharmacological activity of the furoxan derivative condensed with pyridazine di-N-oxide 4,7-dimethyl-1,2,5-oxadiazolo[3,4-d]pyridazine 1,5,6-trioxide (FPTO) and the corresponding furazan (FPDO) was studied.

FPTO reacted with thiols generating nitrite (NO), S-nitrosoglutathione and hydroxylamine (nitroxyl) and converted oxyHb to metHb. FPDO did not generate detectable amounts of NO-like species but reacted with thiols and oxyHb.

FPTO and FPDO haem-dependently stimulated the activity of soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) and this stimulation was inhibited by 1H-[1,2,4]oxadiazolo[4,3-a]quinoxalin-1-one (ODQ) and by 0.1 mM dithiothreitol.

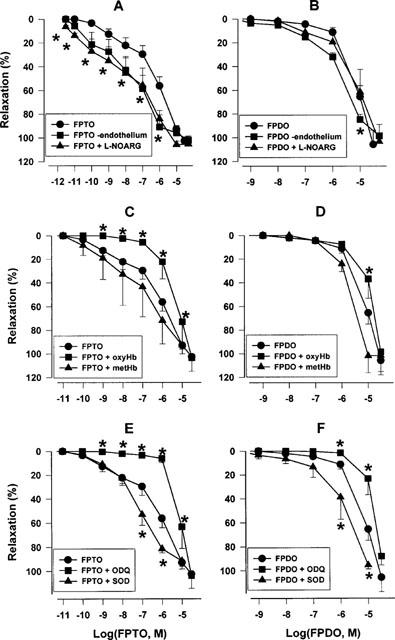

FPTO relaxed noradrenaline-precontracted aortic rings and its concentration-response curve was biphasic (pIC50=9.03±0.13 and 5.85±0.06). FPDO was significantly less potent vasodilator (pIC50=5.19±0.14). The vasorelaxant activity of FPTO and FPDO was inhibited by ODQ. oxyHb significantly inhibited only FPTO-dependent relaxation.

FPTO and FPDO were equipotent inhibitors of ADP-induced platelet aggregation (IC50=0.63±0.15 and 0.49±0.05 μM, respectively). The antiplatelet activity of FPTO (but not FPDO) was partially suppressed by oxyHb. The antiaggregatory effects of FPTO and FPDO were only partially blocked by sGC inhibitors.

FPTO and FPDO (10–20 μM) significantly increased cyclic GMP levels in aortic rings and platelets and this increase was blocked by ODQ.

Thus, FPTO can generate NO and, like FPDO, reacts with thiols and haem. The vasorelaxant activity of FPTO and FPDO is sGC-dependent and a predominant role is played by NO at FPTO concentrations below 1 μM. On the contrary, inhibition of platelet aggregation is only partially related to sGC activation.

Keywords: Furoxan; 1,2,5-oxadiazole; pyridazine di-N-oxide; soluble guanylate cyclase; nitric oxide; nitroxyl; S-nitrosothiols; vasorelaxation; platelet aggregation; cyclic GMP

Introduction

Nitric oxide (NO) and its redox forms (NO-like species) are potent physiological regulators in the cardiovascular, immune and nervous systems (Kerwin et al., 1995). Numerous NO prodrugs (NO donors) release NO or NO-like species under physiological conditions either spontaneously or in the presence of thiols or other cofactors. The main mechanism of the therapeutic effects of NO donors involves activation of soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC) thus increasing intracellular levels of the second messenger, cyclic 3′ : 5′ guanosine monophosphate (cyclic GMP) (for reviews see Hobbs, 1997; Gasco et al., 1996; Feelisch & Stamler, 1996).

Among the newly discovered classes of NO prodrugs, three types of compounds containing heterocyclic nitrogen systems with one or two N-oxide groups including furoxans (1,2,5-oxadiazole 2-oxides), pyrazol di-N-oxides and diazetine di-N-oxides have been reported. The mechanism of biological activity of these derivatives is complex and may involve generation of nitric oxide and NO-like species. Furoxans are potent activators of sGC and are inhibitors of platelet aggregation and vasodilators (Ghosh & Everitt, 1974; Calvino et al., 1992; Ferioli et al., 1995). Furoxans stimulate sGC (Ghigo et al., 1992) by releasing NO in the presence of thiol cofactors (Feelisch et al., 1992; Medana et al., 1994) or other nucleophils (Sorba et al., 1997). Cyclic diazine di-N-oxides (pyrazol di-N-oxides and diazetine di-N-oxides) stimulate sGC and are NO donors, vasodilators and inhibitors of platelet aggregation. Pyrazol di-N-oxides release NO thiol-dependently similar to furoxans (Rehse & Muller, 1995; Ulrich et al., 1995; Dutov et al., 1997). Certain diazetine di-N-oxides are apparently spontaneous NO donors (Severina et al., 1993; Shvartz et al., 1994; Utepbergenov et al., 1995), whereas halogen-substituted derivatives generate NO in the presence of thiols (Kirilyuk et al., 1998). It should be noted that recently 4,7-dihydro-4,4,7,7-tetramethyl-1,2,5-oxadiazolo[3,4-d]pyridazine 1,5,6-trioxide was shown to release nitric oxide following laser flash photolysis (Paschenko et al., 1996).

Combination of the furoxan ring and diazene di-N-oxide group in a single molecule may result in enhanced biological activity compared with the parent compounds. Thus, the pharmacological activity of 4,7-dimethyl-1,2,5-oxadiazolo[3,4-d]pyridazine 1,5,6-trioxide (FPTO) (Figure 1) was studied. The molecule of FPTO is composed of a furoxan ring condensed with a pyridazine di-N-oxide moiety resulting in a unique substance with two potentially active groups known to release nitric oxide. The furazan ring is not actively metabolized under biological conditions (Feelisch et al., 1992). Thus, 4,7-dimethyl-1,2,5-oxadiazolo[3,4-d]pyridazine 5,6-dioxide (FPDO) (Figure 1) was used as a control compound since it lacks the furoxan moiety. In addition, 3,4-dicyano-1,2,5-oxadiazole 2-oxide (dicyanofuroxan, DCF) was used in some experiments as a control compound since this lacks a pyridazine di-N-oxide ring and is highly reactive towards thiols due to the presence of strong electron-withdrawing substituents (Ferioli et al., 1995).

Figure 1.

Structures of FPTO (4,7-dimethyl-1,2,5-oxadiazolo[3,4-d]pyridazine 1,5,6-trioxide), FPDO (4,7-dimethyl-1,2,5-oxadiazolo[3,4-d]pyridazine 5,6-dioxide) and DCF (3,4-dicyano-1,2,5-oxadiazole 2-oxide).

In the present study we have demonstrated that FPTO and FPDO are potent activators of sGC. These compounds react with oxyHb and low molecular weight and protein thiols, relax noradrenaline (NA)-precontracted rings of rat thoracic aorta, inhibit ADP-induced platelet aggregation, and increase cyclic GMP levels in platelets and vascular tissue. However, only FPTO thiol-dependently generates detectable amounts of NO and NO-like species and relaxes noradrenaline (NA)-precontracted aortic rings at concentrations less than 0.1 μM.

Methods

Materials

Synthesis of FPTO (Ponzio & Bernardi, 1925) and FPDO (Steffens & Behrend, 1899) was described for the first time a century ago. FPTO and FPDO were synthesized by oxidation of the corresponding dioximes with N2O4 in ether (Fruttero et al., 1988; Strelenko et al., 1988). The dioxime of 3,4-diacetylfurazan was prepared by treatment of 3,4-diacetylfurazan (Kulikov et al., 1994) with hydroxylamine hydrochloride in water for 24 h at 20°C. Dicyanofuroxan (DCF) (Figure 1) was synthesized by treatment of 3,4-carboxamidofuroxan (Snyder & Boyer, 1955) with P2O5 at 220°C under vacuum. Evaporated DCF was further purified by flash chromatography on silicagel in chloroform. After solvent evaporation, the crystalline product was obtained with 30% yield. Stock 50 mM solutions of FPTO and FPDO prepared in dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO) were stable for at least 2 months at −20°C. Solutions in DMSO were diluted in deionized water or buffer on the day of the experiment and used within 5–6 h. Decomposition of FPTO and FPDO did not exceed 1% within 10 h at room temperature. DCF solution was stored in the dark and used immediately after dilution with deionized water.

Human oxyHb was prepared from fresh venous blood by CM-Sephadex (Pharmacia, Sweden) chromatography (Winterbourn, 1990) and stored frozen at −20°C. Before the experiment, oxyHb (98%) was reduced with a 10 fold molar excess of sodium dithionite and extensively dialysed against 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). metHb (99%) was prepared by treatment with a 10 fold molar excess of potassium ferricyanide. All other reagents were of analytical grade from Sigma Chemical Co. (U.S.A.) unless indicated otherwise. 1H-[1,2,4]Oxadiazolo[4,3-a]quinoxalin-1-one (ODQ), a specific inhibitor of nitric oxide-dependent activation of sGC (Garthwaite et al., 1995), was dissolved in DMSO (10 mM) and further diluted with water or buffer. Diethylamine NONOate (DEA/NO), a spontaneous NO donor (Calbiochem, Switzerland), was dissolved in degassed 10 mM NaOH, stored on ice in the dark and used within 2 h. 3-Morpholinosydnonimine (SIN-1) solution (10 mM) was prepared in ice-cold deionized water and used within 15 min.

Assay of free thiols

Free thiols were assayed by the method of Ellman et al. (1961). The samples (final volume 0.2 ml) containing 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), 0.5 mM thiols (cysteine, glutathione or β-mercaptoethanol), and 50 μM FPTO, FPDO, or DCF or vehicle (0.2% v v−1 DMSO) were incubated for 30 min at 37°C and 1.8 ml of the same buffer containing 0.5 mM 5,5′-dithiobis(dinitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB) were added. After 5 min incubation, optical density was read at 412 nm and the concentration of free thiols was calculated. Gergel & Cederbaum (1997) reported that the DTNB assay can be affected by certain reactive NO-like species. However, our experiments were performed after the reaction of FPTO, FPDO or DCF with thiols is essentially complete and only the stable end-products (nitrite, hydroxylamine) were present in the samples. Control experiments indicated that neither NO2− nor NH2OH (up to 100 μM) influenced the reaction of DTNB with cysteine and glutathione.

Kinetics of reaction with thiols

The rate constants were measured at 25°C in a spectrophotometer (Ultrospec 4050, LKB, Sweden) cell containing 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) and variable concentrations of FPTO or FPDO and thiols (cysteine, glutathione or β-mercaptoethanol). Time course of the reaction was studied by adding thiols (50–500 μM) to the solution of the compounds (10–100 μM) and recording changes in optical density at 252 and 353 nm for FPTO (extinction coefficients ε=20.30 and 4.42 mM−1 cm−1, respectively) and at 240 and 318 nm for FPDO (ε=16.05 and 4.06 mM−1 cm−1, respectively). Initial linear parts of the curves were used to calculate the reaction rate. The extinction coefficients of FPTO and FPDO were determined in a separate set of experiments (mean values; n=6–8). Briefly, these compounds (50 or 100 μM) were incubated for 40 min at 25°C in the presence of 0.5 mM thiols and absorption spectra were recorded every 10 min. The spectrum of FPTO had two peaks at 252 and 353 nm (ε=27.02 and 5.32 nM−1 cm−1, respectively) and similar pattern was observed in the case of FPDO (peaks at 237 and 318 nm with ε=21.02 and 4.06 mM−1 cm−1, respectively). End-products of the reaction with thiols had similar absorption spectra in the case of cysteine, β-mercaptoethanol and glutathione (peaks at 290 and 235 nm with ε=11.6 and 6.96 mM−1 cm−1 in case of FPTO and FPDO, respectively).

Inhibition of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase in intact erythrocytes

Fresh venous blood was taken from apparently healthy donors and blood cells were washed with 0.9% w v−1 NaCl three times by centrifugation at 1000×g for 10 min removing the top leukocyte layer. Erythrocytes were packed and FPTO or FPDO were added to 0.5 ml of cell pellet to make 10 μM final concentration. Samples were incubated for 3 min at 37°C and cells were washed three times with cold 0.9% w v−1 NaCl. Erythrocytes were lysed with 0.5 ml of ice-cold water for 1 h at 4°C and the lysate was centrifuged at 20,000×g for 15 min to separate cytosol from the membrane fraction. Membranes were washed with 0.9% w v−1 NaCl and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase activity was measured. Assay medium contained 0.1 M glycine buffer (pH 8.9), 0.5 mM NAD, 0.5 mM glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate, and 20 mM sodium arsenate. The increase in optical density at 340 nm corresponding to NADH formation was recorded for 15 s to ensure registration of the initial reaction rate. Enzyme activity was expressed in μmol NADH min−1 per 0.5 ml packed cells.

Assay of nitrite (NO), hydroxylamine (NO−) and S-nitosoglutathione by the Griess method

The formation of nitric oxide was determined indirectly by assaying nitrite concentration by the Griess reaction (Schmidt & Kelm, 1996). Compounds (100 μM) were incubated in 1 ml of 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) in the presence or absence of thiols and 1 ml of freshly prepared Griess reagent was added (4 vol of 0.92% w v−1 sulphanilic acid in 30% v v−1 acetic acid, 4 vol of 0.05% w v−1 N-naphthylethylenediamine, and 1 vol of 3 M sodium acetate). Optical density was measured at 554 nm (AG) after 10 min incubation at room temperature. Standard samples (SG) containing sodium nitrite (5–200 μM) were run under the same conditions.

Hydroxylamine was assayed as described (Arnelle & Stamler, 1996) with modifications. Nitroxyl formed during the reaction of the compounds with thiols is trapped by free SH-groups forming hydroxylamine which is oxidized by I3− to nitrite. FPTO, FPDO or DCF (100 μM) were incubated in 1 ml of 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) in the presence or the absence of thiols for 30 min and the following reagents were added sequentially into each tube at 30 s intervals: 0.4 ml of 0.92% w v−1 sulphanilic acid in 30% v v−1 acetic acid, 0.1 ml of 3 M sodium acetate, 0.2 ml of 1.25% w v−1 I2 in 2% w v−1 KI, 0.035 ml of 0.5 M β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.4 ml of 0.05% w v−1 N-naphthylethylenediamine. After 10 min incubation at room temperature optical density was measured at 554 nm (ANH). To determine the amount of hydroxylamine formed, hydroxylamine hydrochloride (SH) and sodium nitrite (SN) standards were run in parallel as well as a separate Griess assay for nitrite. The amount of hydroxylamine formed was determined by the following equation:

|

Nitrosothiols were determined by the Griess reaction performed in the presence of 0.1% w v−1 HgCl2 (Stamler & Feelisch, 1996).

Reaction with oxyHb

OxyHb (40 μM) was incubated in the presence of FPTO, FPDO (50 μM), or vehicle (0.1% v v−1 DMSO) with or without 0.25 mM cysteine in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at 37°C. After 1 h, optical densities of the samples were measured at 577, 630 and 700 nm and concentrations of oxyHb, metHb, choleglobin and haemichrome were calculated as described by Winterbourn (1990). In the presence of 0.25 mM cysteine, small amount of choleglobin was formed (3.5±2.4%; n=4; this value was not significantly changed versus vehicle) but there was no detectable haemichrome formation. Kinetics of oxyHb conversion to metHb were studied by monitoring the decrease in optical density at 577 nm at 25°C (Winterbourn, 1990).

Assay of partially purified haem-deficient rat lung sGC

Soluble guanylate cyclase was partially purified from rat lung essentially as described by Craven & Ignarro (1996) with modifications. Briefly, 100,000×g extract in buffer A (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, containing 5 mM dithiothreitol, DTT) was loaded onto a Toyopearl DEAE-650M column (Toyosoda, Japan) eluted with linear NaCl gradient (0–0.5 M) in buffer A and the peak of enzyme activity (at 0.2 M NaCl) was concentrated, desalted and chromatographed on a Blue Sepharose CL-4B column (Pharmacia, Sweden). The enzyme was eluted with 0.5 M NaCl in buffer A, concentrated and gel filtered through a Sephacryl S-300 column (Pharmacia, Sweden) equilibrated with buffer A. Active fractions were pooled, concentrated and stored in nitrogen-purged 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.6) containing 30% v v−1 glycerol, 10 mM DTT and 1.5 M NaCl at −70°C. This method results in 650 fold purification of sGC activity with 27% yield. The final preparation was haem-deficient and was poorly activated by sodium nitroprusside (SNP) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Effect of FPTO and FPDO on activity or partially purified rat lung sGC (n=6–9)

Prior to the experiment, the enzyme solution was thawed, rapidly desalted by passing through a Sephadex G-25 column equilibrated with 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.6) containing 0.1 mM DTT and immediately added to the ice-cold incubation medium (final volume 100 μl) containing (mM): Tris-HCl (pH 7.6) 50, 3-isobutyl-1-methyl xanthine (IBMX) 1, MgCl2 5, creatine phosphate 5, cyclic GMP 2, [α-32P]-GTP 0.2 (10,000–20,000 c.p.m. pmol−1; Izotop Co., Obninsk, Russia) and 0.4 mg ml−1 creatine kinase. DTT concentration was varied as indicated in the text. Various additions were made and samples were heated at 37°C for 15 min. The reaction was stopped by boiling for 2 min and the amount of [32P]-cyclic GMP formed was assayed by chromatography on acidic aluminium oxide columns after precipitation of unreacted GTP by the ZnCO3 method (Walseth et al., 1991). Yield of cyclic GMP was checked for each batch of aluminium oxide with [3H]-cyclic GMP (Amersham, U.K.).

Study of the effects of FPTO and FPDO on haem-reconstituted enzyme is very difficult since adequate reconstitution requires desalting in the presence of high thiol concentration but thiols suppressed enzyme activation by FPTO and FPDO (Figure 3). Thus, the enzyme was reconstituted by adding 10 μM haemin chloride reduced with 1 mM sodium borohydride and desalted on a Sephadex G-25 column equilibrated with 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.6) containing 0.1 mM DTT. The yield of the active enzyme was low (typically less than 10%) but results presented in Table 4 indicate that haem was partially reconstituted.

Figure 3.

Effect of exogenous DTT on activation of crude rat lung soluble guanylate cyclase preparation by FPTO, FPDO (A) and spontaneous NO donor DEA/NO and basal activity (B) (n=6). Extract was prepared in the absence of thiols and total endogenous thiol concentration in the incubation medium was 16 μM (2.8 μM low molecular weight thiols). The latter value was added to the final DTT concentrations. Spontaneous NO donors (0.1 mM SIN-1 and 0.1 mM SNP) did not significantly activate the enzyme at DTT concentration up to 200 μM but the enzyme was efficiently stimulated in the presence of 10 mM DTT (58±4 and 114±17 fold, respectively) or 5 mM cysteine. Note the difference in ordinate scales between plots A and B.

Assay of crude preparation of rat lung sGC

Since preliminary results have demonstrated that activation of sGC by FPTO and FPDO is suppressed in the presence of high concentrations of thiols (over 100 μM), the extract of rat lung was prepared in the absence of exogenously added thiols. It is known that sGC is unstable without high concentration of thiols and we were unable to prepare the active enzyme without exogenous thiols using a standard protocol (centrifugation for 1 h at 100,000×g). Apparently, this is due to the long time required for centrifugation. Because of this, we developed a protocol for rapid centrifugation in the presence of 10 mM MgCl2 that was added to improve sedimentation of the particulate fraction(s). The possibility of contamination with particulate guanylate cyclase was checked by preparing the extracts in the presence of DTT. One sample was centrifuged for 100,000×g for 1 h and another identical sample was supplemented with 10 mM MgCl2 and centrifuged at 30,000×g for 30 min. Then, basal and Mn2+-stimulated guanylate cyclase activity was assayed in both samples simultaneously and the values for both activities did not differ significantly (P<0.05; n=3).

Rat lung was cleaned of blood and connective tissue and homogenized using a hand-held glass-glass homogenizer in 5 vol of 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.6) containing 10 mM MgCl2. The homogenate was centrifuged at 30,000×g for 30 min and the enzyme activity was assayed as described above for partially purified sGC. The enzyme activity was stable for up to 1 h when stored on ice. The extract contained some endogenous thiols and their concentration was assayed by the Ellman's method directly in the extract and after precipitation of the proteins with 5% w v−1 trichloroacetic acid. Total thiol content was 16.0±4.2 nmol mg−1 protein and low molecular weight thiols were 2.8±0.2 nmol mg−1 protein. This corresponds to 8–16 μM thiols in the incubation medium for sGC assay. This value should be considered with caution because incubation medium also contains some additional SH-groups of creatine kinase.

Protein concentration in the rat lung extract and preparation of partially purified sGC was assayed by the method of Lowry et al. (1951).

Vasorelaxant activity studies (organ bath)

The vasorelaxant activity of the compounds studied was assayed in NA-precontracted rat thoracic aorta rings. Male Wistar rats (210–330 g weight) were decapitated and thoracic aorta was removed and cleaned of surrounding adipose tissue. Rings were cut (3.5 mm in length) and mounted between two parallel stainless steel hooks. One hook was fixed to the organ bath wall and another was connected to a DY1 isometric force transducer which was coupled to a Gemini two-channel recorder (both from Ugo Basile, Varese, Italy). The organ bath medium contained 30 ml of Krebs-indomethacin, solution (mM): NaCl 130, KCl 4.7, CaCl2 2.5, KH2PO4 1.18, NaHCO3 14.9, MgSO4 1.2, glucose 11, and 1 μM indomethacin, at 37°C and constantly aerated with 95% O2/5% CO2 (pH 7.4). The rings were equilibrated for 1 h repeatedly readjusting optimal tension (1.2 g).

At the beginning of the experiment, rings were sensitized with 10 nM NA and after 15 min, precontracted with a submaximal concentration of NA (0.5 μM). When the NA-dependent increase in tension became constant, FPTO, FPDO, DCF, sodium nitroprusside, SIN-1 or DEA/NO were added to the bath and cumulative concentration-response curves were recorded. Presence of intact endothelium was controlled by acetylcholine relaxation (50 nM–50 μM) and endothelium-independent relaxation in mechanically denuded rings (with a stainless steel rod) was verified with SNP (0.1–1000 nM).

In all experiments, 10 U ml−1 superoxide dismutase (SOD), 1 mM cysteine, 0.1 mM L-NG-nitroarginine (L-NOARG), 1 μM ODQ, 10 μM oxyHb or 10 μM metHb were added prior to contraction of the aortic rings with 0.5 μM NA. Because the tissue was subjected to various treatment protocols, we verified that 0.5 μM NA produces 85–95% of maximal contraction. In intact rings, the EC50 for NA was 20.3±5.6 nM and the percentage of contraction calculated from the concentration-response curve corresponding to 0.5 μM NA was 90.6±2.6%. SOD, ODQ, oxyHb, and metHb did not significantly influence these parameters. The EC50 values in endothelium-denuded rings and tissues treated with 0.1 mM L-NOARG and 1 mM cysteine were 17.9±4.2, 22.0±7.1 and 38.0±7.6 nM, respectively, and percentages of contraction corresponding to 0.5 μM NA were 93.3±2.7, 94.2±2.2, and 85.6±3.4%, respectively (n=4 for each value).

Platelet aggregation

Citrate-treated venous blood taken from apparently healthy donors was centrifuged at 450×g for 10 min at room temperature to obtain platelet-rich plasma. Centrifugation of platelet-rich plasma at 650×g for 30 min yielded platelet-poor plasma. Platelet content was adjusted in platelet-rich plasma to 2.5×108 cells ml−1 with platelet-poor plasma and the suspension was added to a 0.5 ml aggregometer cell. Aggregation was initiated by addition of 2–5 μM ADP. The concentration of ADP was adjusted in each experiment to ensure that aggregation was reversible, maximal within 2 min and did not exceed 50%. Light scattering of the platelet suspension was measured by an aggregometer developed in the Laboratory of Bioorganic Chemistry, School of Biology, Moscow State University. Various additions were made as indicated in Table 6 before aggregation was started with ADP. To evaluate the antiaggregatory effects of FPTO and FPDO, these compounds were added at the peak of reversible aggregation.

Table 6.

Effect of FPTO, FPDO and DCF on ADP-induced platelet aggression

Assay of cyclic GMP levels in human platelets

Samples (4 ml final volume) contained 1 ml of platelet suspension (2.5×108 cells ml−1, 3 ml of platelet-poor plasma and 10 μM FPTO, FPDO, and DCF or 100 μM SNP. Tubes were incubated for 10 min at 37°C and centrifuged for 5 min at 1500×g. The pellet was resuspended in 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.6) containing 8 mM EDTA, sonicated for 20 s on ice, boiled for 2 min and recentrifuged for 10 min at 2000×g. Cyclic GMP was assayed in the supernatant by an ELISA cyclic GMP assay kit (Biogen Co., Moscow, Russia).

Assay of cyclic GMP levels in rabbit thoracic aorta rings

The protocol of Moro et al. (1996) was followed with minor modifications. Briefly, rabbits were anaesthetized with sodium pentobarbitone (40 mg kg−1 as bolus i.v.) and killed by decapitation. The thoracic aorta was excised, washed to remove blood and cleaned of fat and connective tissues. Aorta was cut into 1 cm rings that were equilibrated in the Krebs solution at 37°C under constant aeration for 1.5 h. IBMX (1 mM) and ODQ (3 μM) were added to the corresponding tubes and preincubated for 30 min. Thereafter, 10 μM FPTO, 20 μM FPDO or vehicle (0.4% v v−1 DMSO) were added and samples were incubated for 3 min. The tissue was frozen, ground in a mortar with liquid nitrogen and extracted for 1 h with 1 M HClO4 on ice. The extract was centrifuged at 15,000×g for 3 min and the supernatant was neutralized with ice-cold 2 M K2CO3 and centrifuged. Cyclic GMP was assayed in the supernatant using a [3H]-cyclic GMP assay kit from Amersham (U.K.). Results were normalized versus soluble protein concentration determined by the Bio-Rad Coomassie assay kit.

Statistics

Experiments were repeated at least three times and statistical significance was estimated by unpaired or paired Student's t-test when appropriate; P<0.05 was considered significant. Data are shown as mean±s.e.mean.

Results

Reaction with thiols

FPTO, FPDO and DCF are highly electrophilic and readily react with nucleophils such as thiols. Incubation of these compounds with cysteine, glutathione and β-mercaptoethanol resulted in a decrease in the concentration of free thiols in the solution. Stoichiometry of the reaction of FPTO with cysteine, glutathione, and β-mercaptoethanol was 3.5±0.2, 3.1±0.1 and 2.5±0.1 mol mol−1 FPTO (P<0.05 versus cysteine), respectively. In the case of the reaction of FPDO with cysteine, glutathione and β-mercaptoethanol, the stoichiometry was 2.3±0.1, 2.2±0.2 and 2.0±0.2 mol mol−1 FPDO, respectively. Stoichiometry of the reaction of DCF with cysteine, glutathione and β-mercaptoethanol was 4.8±0.2, 4.9±0.2 and 1.8±0.2 mol mol−1 DCF (P<0.05 versus cysteine), respectively (n=4 for each value). In the case of FPTO and FPDO, the more thiols which reacted with the compounds, the higher was the apparent second order rate constant of the reaction measured by spectrophotometric monitoring of the decomposition of FPTO and FPDO in the presence of thiols (Table 1). In general, FPTO was more reactive than FPDO.

Table 1.

Kinetics of the reaction of FPTO and FPDO with thiols (n=6–10)

FPTO and FPDO (10 μM) decreased the free thiol content of the rat lung extract prepared in the absence of exogenous SH-groups from 16.0±4.2 to 0.1±0.2 nmol mg−1 protein (n=4). Moreover, FPTO and FPDO inhibited the activity of a thiol-dependent enzyme, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, in intact human erythrocytes. Enzyme activity in the membrane fraction was decreased from 4.9±0.3 μmol NADH min−1 per 0.5 ml packed cells (vehicle; 0.02% v v−1 DMSO) to 3.1±0.9 μmol NADH min−1 per 0.5 ml packed cells (10 μM FPTO; P<0.05 versus vehicle) and 4.5±0.3 μmol NADH min−1 per 0.5 ml packed cells (10 μM FPDO); activity in the cytosol was decreased from 4.5±0.4 μmol NADH min−1 per 0.5 ml packed cells (vehicle) to 4.0±0.7 μmol NADH min−1 per 0.5 ml packed cells (10 μM FPTO) and 2.6±0.5 μmol NADH min−1 per 0.5 ml packed cells (10 μM FPDO; P<0.01 versus vehicle). Overall enzyme inhibition (membrane+cytosolic) was 24.5±2.1% (P<0.05) for FPTO and FPDO (n=10–12 for each value).

Formation of nitrite (NO), hydroxylamine (nitroxyl) and S-nitrosoglutathione

It has been shown that furoxans thiol-dependently or spontaneously generate nitric oxide and S-nitrosothiols and this is associated with transformations of the furoxan ring (Feelish et al., 1992; Medana et al., 1994; Sorba et al., 1997). Similar findings were reported for pyrazol di-N-oxides (Ulrich et al., 1995; Dutov et al., 1997). FPTO and FPDO are apparently stable at neutral pH in aqueous solutions but react with thiols and they could generate nitric oxide, nitroxyl, nitrosothiols or a mixture of these species. FPTO did not generate detectable amounts of NO as measured by nitrite concentration at neutral pH in the absence of thiols (Table 2). In the presence of thiols, nitrite ion was rapidly formed and the reaction was complete in 10 min. The yield of nitrite depended on thiol concentration (Figure 2) suggesting a complex reaction mechanism. To verify that the assay is really detecting NO and not nitrite ion itself, the reaction was performed in the presence of 100 μM oxyHb which almost quantitatively traps NO (but is inactive towards nitrite) yielding nitrate ion; nitrate does not react in the Griess assay (Table 2). This experiment demonstrates that at least 80% of the nitrite detected by the Griess assay is formed indirectly from NO oxidized by O2 (Schmidt & Kelm, 1996). Formation of NO from FPTO in the presence of cysteine was also demonstrated by chemiluminescence at pH 8.0 (A. Gasco & C. Medana, personal communication). Similar results were obtained with the known NO-generating furoxan, DCF (Table 2). Nitrite generation from FPTO was unaffected by 0.1 mM EDTA or 0.1 mM Fe3+ ions thus ruling out the possibility of involvement of contaminating metal ions in nitrite formation. The amount of nitrite thiol-dependently generated from FPTO was slightly increased in the presence of high concentrations of SOD (150 U ml−1) which can convert NO− to NO• thus increasing nitrite apparently at the expense of nitroxyl. Low concentration of SOD (15 U ml−1) had no effect on nitrite formation indicating that superoxide is not generated. FPDO did not generate significant amounts of nitrite (Table 2).

Table 2.

Formation of nitrite, S-nitrosoglutathione and hydroxylamine in the reaction of FPTO, FPDO and DCF with thiols (n=3–7)

Figure 2.

Effect of cysteine and glutathione on generation of nitrite from FPTO (n=5).

Additionally, FPTO (but not FPDO or DCF) generated nitroxyl that was trapped by thiols forming hydroxylamine (Table 2). Assuming a trapping efficiency of 40% (Arnelle & Stamler, 1995) gives 1.1±0.2 mol nitroxyl mol−1 FPTO in the presence of 0.5 mM glutathione. Similar to the findings of Feelisch et al. (1992), we detected S-nitrosoglutathione (but not S-nitrosocysteine) as the end-product of the reaction of FPTO (but not FPDO or DCF) with glutathione (Table 2). The sum of all the reactive nitrogen oxide species (detected as nitrite, S-nitrosoglutathione and hydroxylamine, again assuming 40% trapping efficiency of nitroxyl) generated from FPTO in the presence of 0.5 mM glutathione was 1.7±0.2 mol NO-like species mol−1 FPTO with hydroxylamine (NO−/HNO) as the most abundant (64±12%).

Reaction with oxyHb

FPTO and FPDO (50 μM) converted oxyHb to metHb in the absence of added thiols (62.6±6.8 and 40.1±8.5% of oxyHb were converted to metHb in 1 h at 37°C, respectively; n=3). In the presence of 0.25 mM cysteine, 81.5±4.9 and 59.8±7.0% of oxyHb were converted to metHb by FPTO and FPDO, respectively (n=5). Some formation of metHb was induced by cysteine itself (36.7±6.2%; n=3); when the percentage of metHb formation are recalculated versus the concentration of oxyHb in the vehicle-containing samples (0.1% v v−1 DMSO) in the presence of cysteine, the resulting values for FPTO and FPDO were 44.8±2.9 and 23.1±4.4%. Thus, cysteine partially protects oxyHb from conversion into metHb by both compounds. When metHb was incubated with FPTO or FPDO under similar conditions, no formation of oxyHb was detected (data not shown).

The rate of the reaction of FPTO and FPDO with 30 μM oxyHb was determined at 25°C as a decrease in optical density at 577 nm. The reaction rates with 20 and 50 μM FPTO were 0.191±0.009 and 0.406±0.028 μM min−1 and the reaction rates with 20 and 50 μM FPDO were 0.048±0.010 and 0.118±0.001 μM min−1, respectively. In the presence of variable concentrations of glutathione or cysteine (20, 40 and 60 μM), the reaction rates were dramatically increased. The rate of FPTO reaction with oxyHb was linearly dependent on thiol concentration and the apparent first order rate constants (rate divided by thiol concentration) were 0.058±0.004 and 0.025±0.002 min−1 for glutathione and cysteine, respectively. On the contrary, the rate of FPDO reaction with oxyHb was not changed when thiol concentration varied from 20 to 60 μM (0.51±0.02 and 0.14±0.02 μM min−1 for glutathione and cysteine, respectively).

Activation of rat lung sGC

The crude enzyme extracted in the absence of exogenous thiols is apparently stable for a short period of time because it can be activated in the absence of cysteine by MnCl2 and protoporphyrin IX and in the presence of 5 mM cysteine, by SNP thus indicating the presence of an intact catalytic domain and haem moiety (Table 3). FPTO and FPDO were potent activators of sGC with FPTO being significantly more active versus FPDO at 10 μM concentration. Addition of thiols is required to detect sGC stimulation by spontaneous NO donors (DEA/NO and SIN-1) and SNP. Unlike these compounds, FPTO- and FPDO-dependent activation of sGC was completely blocked by DTT at 0.1 mM concentration (Figure 3). Addition of DTT up to 1 : 1 molar ratio to FPDO potentiated sGC activation (Figure 3). DCF slightly stimulated sGC without thiols and its activator potency was greatly increased by 5 mM cysteine (Table 3). The stimulatory effects of FPTO and FPDO on sGC were inhibited by 93±4 and 101±3%, respectively, in the presence of 1 μM ODQ. An oxidant of haem iron, K3[Fe(CN)6] (50 μM), also inhibited the sGC activation by FPTO and FPDO by 93±3 and 93±4%, respectively. Since K3[Fe(CN)6] can oxidise thiols essential for sGC activity, its effect was compared with 50 μM DTNB. DTNB modified all free thiol groups and completely suppressed basal activity and protoporphyrin IX-dependent stimulation of sGC as well as the effects of FPTO and FPDO on the enzyme (data not shown). Thus, the inhibition of FPTO- and FPDO-dependent stimulation of sGC by K3[Fe(CN)6] can be due to the oxidation of the haem iron of the enzyme.

Table 3.

Effect of FPTO and FPDO on activity of crude preparation of rat lung sGC (n=6–9)

To determine whether the compounds can activate the haem-deficient form of the enzyme, a partially purified preparation of sGC was used (Table 4). FPTO, FPDO and DCF did not significantly affect the activity of this enzyme, although sGC was efficiently stimulated by manganese and protoporphyrin IX. Moreover, unlike YC-1 that stimulates activation of the enzyme by protoporphyrin IX (Friebe & Koesling, 1998), FPTO, FPDO and DCF inhibited the stimulatory effect of protoporphyrin IX on haem-deficient enzyme at low concentrations of DTT (20 μM) by 67±3, 92±4 and 77±3%, respectively (Table 4). This can be due to modification of thiols required for haem or protoporphyrin IX binding to sGC (Friebe et al., 1997). However, FPTO and FPDO were able to activate the haem-reconstituted enzyme in the presence of low concentrations of DTT (10 μM). sGC was activated by SNP when supplemented with high thiol concentration (10 mM DTT) confirming that the intact haem moiety is indeed reconstituted (Table 4), Hence, the presence of the Fe2+-containing haem and up to equimolar amount of thiols is apparently required for FPTO and FPDO to activate sGC.

Vasorelaxant activity

FPTO and FPDO relaxed NA-precontracted aortic rings. The effects of these compounds developed rapidly (3–4 min) even at concentrations below 1 μM. FPTO was significantly more potent than FPDO and the effect of FPTO was clearly biphasic. The concentration-response curve of FPTO could not be adequately fitted by a single 3- or 4-parameter sigmoidal function (P>0.1; Student's t-test). Hence, the combination of two 3-parameter sigmoidal functions was used to describe the data (Figure 4). The parameters are listed in Table 5 where Rmax(1) and IC50(1) correspond to the values of maximal relaxation and IC50 of the left nanomolar part of the curve (FPTO concentration below 0.1 μM) and Rmax(2) and IC50(2) correspond to maximal relaxation and IC50 of the FPTO concentrations above 0.1 μM. FPDO was active only at concentrations above 0.1 μM (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Concentration-dependent relaxation of NA-precontracted aortic rings with FPTO and FPDO. For details see text. Data are mean±95% confidence limits (n=9–13).

Table 5.

Characteristics of vasorelaxant activity of FPTO in NA-precontracted aortic rings

When the endothelium was mechanically removed, the vasorelaxant effects of FPTO and FPDO were potentiated (Figure 5A,B). In the case of FPTO, both pIC50 values were decreased (Table 5). Addition of a NO-synthase inhibitor, 0.1 mM L-NG-nitroarginine (L-NOARG), in the endothelium-intact preparation also decreased the pIC50 values for FPTO (Figure 5A; Table 5). The removal of endothelium potentiated the vasorelaxant activity of FPDO but L-NOARG treatment had no such effect (Figure 5B). Thus, FPTO and FPDO are endothelium-independent vasorelaxing agents.

Figure 5.

Characterization of vasorelaxant activity of FPTO (A,C,E) and FPDO (B,D,F) in aortic rings precontracted with 0.5 μM NA. Endothelium-denuded (A,B) or intact rings (A–F) were pretreated 10 min before NA addition with 0.1 mM L-NOARG (A,B), 10 μM oxyHb or metHb (C,D), 1 μM ODQ or 10 U ml−1 SOD (E,F) and cumulative concentration-response curves for FPTO or FPDO were recorded. The pIC50 and Rmax values for FPTO are given in Table 5. Values of FPDO activity were determined by fitting the data to a 3- or 4-parameter logistic equation and fitting quality was always satisfactory (P<0.05; Student's t-test). Rmax shown are mean±s.e.mean and pIC50 values were weighted versus standard error (mean±95% confidence intervals). Control: pIC50=5.19±0.14, Rmax=105.7±12.1% (n=9); without endothelium: pIC50=5.58±0.05 (P<0.05 versus control), Rmax=98.4±9.5 (n=4); with endothelium: 0.1 mM L-NOARG: pIC50 5.20±0.21, Rmax=103.2±2.2 (n=4); 10 μM oxyHb: pIC50 4.92±0.16, Rmax=54.7±16.5 (n=4); 10 μM metHb: pIC50 5.53±0.10, Rmax=101.8±14.3 (n=4); 10 U ml−1 SOD: pIC50=5.66±0.17 (P<0.05 versus control), Rmax=106.0±3.3% (n=4); 1 μM ODQ: pIC50=4.87±0.20 (P<0.05 versus control), Rmax=87.9±12.4 (n=4). Asterisks correspond to the points significantly different from control (P<0.05).

A known nitric oxide scavenger, oxyHb (10 μM), strongly inhibited the vasorelaxant activity of FPTO (Figure 5C; Table 5). Slight inhibition of FPDO-dependent relaxation by oxyHb (Figure 5D) can be due to scavenging of the active substance. metHb (10 μM) had no significant influence on the vasorelaxant effect of either FPTO or FPDO.

ODQ (1 μM), a selective blocker of the processes associated with haem-dependent sGC activation, dramatically inhibited the vasorelaxant effects of FPTO and FPDO (Figure 5E,F). Similar to oxyHb, ODQ completely suppressed FPTO-dependent relaxation at FPTO concentrations below 1 μM. Also, ODQ partially blocked the relaxation induced by both FPTO and FPDO at 1 μM concentration. Thus, both compounds cause relaxation of NA-precontracted aorta via haem-dependent stimulation of sGC. In the presence of SOD (15 U ml−1), the effects of FPTO and FPDO at concentrations above 0.1 μM were potentiated (Figure 5E,F).

Cysteine has been suggested as an efficient trap for nitroxyl (Zamora et al., 1995) which is thiol-dependently formed from FPTO (Table 2). The effect of 1 mM cysteine on the vasorelaxant activity of FPTO was complex (Figure 6, Table 5). In the presence of cysteine, the relaxation of NA-precontracted aortic rings induced by low concentrations of FPTO (below 0.1 μM) was slightly potentiated, whereas at high FPTO concentrations (above 1 μM), the relaxation was partially suppressed and was slowly reversible (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Effect of 1 mM cysteine on vasorelaxant activity of FPTO. Typical recording representative of five similar experiments is shown. Arrows correspond to addition of 1 mM cysteine (Cys) or 0.5 μM NA. Numbers from 1 to 6 correspond to cumulative concentrations of FPTO: 0.1 nM (1), 1 nM (2), 10 nM (3), 100 nM (4), 1 μM (5), and 10 μM (6). Control recording without cysteine (A) indicates that NA-dependent contraction is developing faster in the presence of cysteine (B) and vascular tone was stable during the experiment (C).

The control compound, DCF, was also a potent vasorelaxant with a pIC50=6.89±0.31; its activity was not affected by 10 μM oxyHb (pIC50=7.14±0.12), 10 μM metHb (pIC50=7.11±0.23), 1 mM cysteine (pIC50=6.67±0.30), slightly enhanced in the presence of 15 U ml−1 SOD (pIC50=7.66±0.17; P<0.05) and suppressed by 3 μM ODQ (pIC50=4.80±0.42; P<0.05) (n=4; maximal relaxation Rmax at 30 μM DCF varied from 97.9 to 110.2%).

The potentiation of the vasorelaxant activity of NO donors in phenylephrine-precontracted aortic rings by removal of endothelium and inhibition of NO-synthase has been demonstrated by Moncada et al. (1991). Thus, we have tested the vasorelaxant effects of a spontaneous NO donor (DEA/NO) and SNP in endothelium-denuded rings and rings incubated in the presence of L-NOARG (0.1 mM). However, the effects of DEA/NO and SNP (pIC50 in intact rings were 4.68±0.65 and 7.85±0.21, respectively) were not enhanced by removal of endothelium (pIC50=4.65±0.32 and 7.55±0.17, respectively) or by inhibition of NO-synthase (pIC50= 4.68±0.43 and 7.41±0.14, respectively). These data are in agreement with the results of Morley et al. (1993) and Salom et al. (1998). The potency of DEA/NO and SNP was also unaffected by 1 mM cysteine (pIC50=4.45±0.44 and 7.63±0.11, respectively) thus confirming the data of Zamora et al. (1995).

Inhibition of ADP-induced platelet aggregation

FPTO and FPDO were potent inhibitors of ADP-dependent reversible platelet aggregation (Figure 7A); IC50 values were 0.63±0.15 and 0.49±0.05 μM, respectively, and the difference between these values was not statistically significant (P=0.6). Moreover, FPTO and FPDO were equipotent in inducing desaggregation of ADP-preaggregated platelets (Figure 7B) with IC50 values of 1.39±0.73 and 1.16±0.25 μM for FPTO and FPDO, respectively.

Figure 7.

Inhibition of ADP-induced human platelet aggregation (A) and desaggregation of reversibly aggregated platelets (B) by FPTO and FPDO (n=4). SNP is shown as the reference.

Inhibition of aggregation induced by 10 μM FPTO was slightly decreased by 10 μM oxyHb (by 23±7%) but unaffected by 10 μM metHb, whereas the effects of 10 μM FPDO were not sensitive to 10 μM oxyHb and 10 μM metHb (Table 6). The anti-aggregatory activity of FPTO and FPDO was partially blocked by 10 μM ODQ (by 13±4 and 64±14%, respectively) (Table 6). Another non-specific inhibitor of sGC, methylene blue (10 μM), significantly ameliorated the inhibition of platelet aggregation by FPTO and FPDO by 37±9 and 60±14%, respectively. Unfortunately, the interpretation of the effect of methylene blue is difficult because it inhibited platelet aggregation by itself (Table 6). Thus, sGC activation is responsible for at least some of the effects of FPTO and FPDO on platelets. The antiplatelet activity of 10 μM DCF was suppressed by 10 μM oxyHb (by 75±7%) and 10 μM metHb (by 82±9%) and was partially inhibited by 10 μM ODQ (by 29±6%), whereas the effects of SNP were completely blocked by 10 μM ODQ (Table 6).

Stimulation of cyclic GMP accumulation

The antiaggregatory effects of FPTO and FPDO were only partially suppressed by inhibition of sGC with ODQ and methylene blue. To determine whether this may result from an inability of FPTO and FPDO to increase platelet cyclic GMP levels, the cyclic GMP content in platelets was assayed. The cyclic GMP levels in untreated cells were 10.2±1.2 pmol per 109 cells. Treatment with 10 μM FPTO, FPDO, and DCF or with 100 μM SNP increased intracellular cyclic GMP levels to 15.4±2.1, 13.6±1.3, 12.5±1.5 and 15.0±1.6 pmol per 109 cells, respectively (P<0.05; n=3 for each value). The anti-aggregatory effects of SNP were completely blocked by ODQ unlike the antiplatelet activity of FPTO, FPDO and DCF (Table 6) thus suggesting that the mechanism of action of the latter three substances involves but is not restricted to the activation of sGC.

FPTO (10 μM) and FPDO (20 μM) increased the levels of cyclic GMP in rabbit thoracic aorta preparation from 3.1±2.2 to 20.8±2.8 pmol and 12.5±3.0 pmol cyclic GMP mg−1 protein, respectively (P<0.01; n=4). This increase was completely blocked by 3 μM ODQ (2.0±1.4, 2.9±0.8, and 3.8±1.4 pmol cyclic GMP mg−1 protein in the presence of ODQ, ODQ plus FPTO and ODQ plus FPDO, respectively; P<0.001; n=4). Increase in cyclic GMP content was potentiated by phosphodiesterase inhibition with 1 mM IBMX (11.4±1.3, 174.1±20.3, and 102.9±23.1 pmol cyclic GMP mg−1 protein in the presence of IBMX, IBMX plus FPTO and IBMX plus FPDO, respectively; P<0.001; n=3). This suggests that FPTO and FPDO enhance the synthesis of cyclic GMP by sGC stimulation and apparently have little or no effect on cyclic GMP-specific phosphodiesterase.

Discussion

The molecule of FPTO comprises a pyridazine di-N-oxide ring condensed with a furoxan ring. Each of these two rings potentially can generate NO and NO-like species either spontaneously or thiol-dependently. Two control compounds were used, i.e. FPDO and DCF. FPDO may be considered as a control compound since it lacks the reactive furoxan moiety because it contains an apparently stable furazan moiety (Feelisch et al., 1992). DCF is also a control since it lacks the pyridazine di-N-oxide moiety. FPTO, FPDO and DCF are apparently stable in aqueous solution at pH 7.4 and thus these compounds cannot be considered as spontaneous NO donors. On the other hand, the three substances readily react with thiols including cysteine, glutathione and β-mercaptoethanol. In the case of FPTO, this reaction results in generation of NO and NO-like species (Table 2). In the case of DCF, only NO is generated. FPDO does not form detectable amounts of NO or NO-like species. Thus, the furoxan ring is evidently required for generation of nitrite, nitroxyl and S-nitrosothiols from FPTO. At least 75% nitrite generated from FPTO and DCF as determined by the Griess assay corresponds to NO because trapping of NO with oxyHb (with formation of nitrate) results in reduced amounts of detected nitrite (Table 2).

Formation of NO and S-nitrosoglutathione has been demonstrated for certain furoxans (Feelish et al., 1992). Considering the overall reaction stoichiometry (1.74 mol NO and NO-like species mol−1 FPTO), thiol-dependent decomposition of the furoxan moiety of FPTO cannot result in such a massive generation of reactive nitrogen oxide species (stoichiometry would be below 100%). Thus the pyridazine di-N-oxide system is apparently contributing to the overall complex reaction stoichiometry including generation of nitroxyl. The pyridazine di-N-oxide moiety itself is responsible for the reaction with low molecular weight and protein thiols and oxidation of oxyHb to metHb but not for nitric oxide formation. Moreover, conversion of oxyHb to metHb by FPTO in the presence of thiols is significantly accelerated and the apparent reaction rate constant linearly depends on thiol concentration. On the other hand, the rate of the reaction of FPTO and FPDO with thiols also linearly depends on thiol concentration (Table 1). If FPDO thiol-dependently generated nitric oxide, the rate of oxyHb conversion to metHb in the presence of FPDO and thiols should be accelerated compared to FPDO without thiols and should depend on thiol concentration; however, this is not observed. Thus, the data of the Griess assay and experiments with oxyHb suggest that only FPTO (but not FPDO) thiol-dependently forms detectable amounts of NO and NO-like species.

Considering the reaction of FPTO and FPDO with thiols, it should be noted that thiol oxidation is not unique to pyridazine di-N-oxide. For example, trimethylamine N-oxide reacts with SH-containing amino acids forming disulphides (Brzezinsky & Zundel, 1993). The apparent second order rate constants and stoichiometry of the reaction with thiols are higher for FPTO than FPDO. This may be partially due to the secondary reactions of NO-like species generated from FPTO in the presence of an excess of free thiols. Overall reactivity of FPTO and FPDO towards protein thiols in intact cells measured as inhibition of a thiol-dependent glycolytic enzyme glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase in human erythrocytes is very similar because FPTO and FPDO inhibited the enzyme activity to the same extent.

Conversion of oxyHb to metHb by FPTO and FPDO in the absence of thiols indicates that, like 4,6-dinitrobenzofuroxan (Reddy et al., 1989; 1991), FPTO and FPDO are electron acceptors and can react with certain metalloporphyrins. The sGC molecule contains a haem moiety which is extremely sensitive to NO and oxidation. Moreover, thiol groups are very important for regulation of sGC activity (Ignarro, 1989). Thus, the influence of FPTO and FPDO on rat lung sGC was studied and it was shown that FPTO and FPDO are potent activators of sGC (Tables 3 and 4). Enzyme activation by FPTO can be explained by thiol-dependent formation of NO and NO-like species. However, NO generation from FPDO under the conditions of the sGC assay using crude extract seems unlikely because FPDO did not form significant amounts of nitrite. Partially purified haem-reconstituted emzyme is also activated by FPDO (Tables 3 and 4). Although the sGC was not extensively purified to homogeneity, the degree of purification was over 600 fold thus making participation of any residual factors catalysing biotransformation of some active species into nitric oxide unlikely.

Thus, the major factors which account for the biological activity of FPTO, FPDO and DCF include reaction of these compounds with thiols (associated or not associated with NO formation) and interaction with haem-containing proteins. These mechanisms should be considered in the case of stimulation of sGC activity by FPTO, FPDO and DCF.

Di Stilo et al. (1996) have shown that accumulation of cyclic GMP in the presence of furoxans is enhanced by thiols. Also, DCF and spontaneous NO donors (DEA/NO and SIN-1) require high concentrations of thiols (1–10 mM) for sGC activation (Table 3, Figure 3). In the case of FPTO and FPDO, thiol-dependent generation of NO or NO-like species cannot account for the sGC stimulation because enzyme activation was completely suppressed at 0.1 mM DTT (Figure 3). Even if FPDO undergoes some biotransformation into nitric oxide, which cannot be rigorously excluded on the basis of our data, thus generated NO-like species should not be identical to those generated from FPTO because otherwise, the vasorelaxant effects of FPDO would be more pronounced at concentrations below 0.1 μM and are expected to be more sensitive to oxyHb (Figure 5D); moreover, it is known that nitroxyl does not activate sGC (Dierks & Burstyn, 1996). However, the presence of a Fe2+-containing haem moiety and up to equimolar amounts of thiols are required for the activatory effects of FPTO and FPDO on sGC (Tables 3 and 4). Enzyme stimulation by FPTO and FPDO was inhibited by ODQ which can oxidise the haem-bound Fe2+ atom of sGC (Schrammel et al., 1996) and another oxidant, K3[Fe(CN)6]. Thus, sGC stimulation by FPTO and FPDO cannot be explained by generation of nitric oxide or other NO-like species.

There are alternative mechanisms for FPTO and FPDO which may be involved in the activation of sGC. These mechanisms can include direct NO-independent interaction with the Fe2+ atom of the haem group mediated by the N-oxide groups of the pyridazine di-N-oxide ring of FPTO and FPDO. For example, other authors have demonstrated that a 1-hydroxypyrazole 2-oxide derivative is the bidentate ligand of various transition metal ions (West & Johnson, 1979) and certain diazine di-N-oxides have been reported to generate azodioxide radical cations (Greer et al., 1995). Also, some porphyrins have been reported to form π-π donor-acceptor complexes with a benzofuroxan derivative (Chandrashekar & Krishnan, 1983). However, we were unable to detect such a complex between FPTO and protoporphyrin IX in the solution by spectrophotometry (data not shown). Breakage of N-N bond of FPTO and FPDO can generate a dinitroso intermediate which may react with thiols forming a hydronitroxide radical-like structure (Takahashi et al., 1988). In this case, thiols would inhibit activation (Figure 3) by removing the active species from the medium in a sequence of reactions and promote enzyme stimulation by reducing haem iron oxidized by FPDO and presumably FPTO similar to a benzofuroxan derivative (Reddy et al., 1991). On the other hand, at higher concentrations of FPTO and FPDO, oxidation of haem iron can play a significant role and thus activation is not observed at 0.1 mM FPTO and FPDO and 10–20 μM DTT (Severina & Busygina, unpublished observation).

Thus, interaction of FPTO and FPDO with sGC can involve oxidation of Fe2+ haem similar to oxyHb, formation of a coordinate bond with Fe2+ thus extracting it from the plane of the haem and activating the enzyme, and charge transfer donor-acceptor complexation. These or similar events can lead to the activation of sGC which is known to be haem-dependently activated by free radical species (Ignarro, 1989).

The mechanisms of vasorelaxant and antiplatelet activity of FPTO and FPDO are complex and involve NO-dependent and NO-independent activation of sGC, modification of low molecular weight and protein thiols or reaction with haem-containing proteins.

The generation of NO or S-nitrosothiols seems to be important for vasorelaxant effects of FPTO at concentrations below 0.1 μM. The pharmacological behaviour of FPTO at these low concentrations is similar to that of a typical NO donor and sGC activator because its effects are blocked by oxyHb (Figure 5C) and ODQ (Figure 5E) and it induces relaxation by an endothelium-independent mechanism. On the other hand, generation of nitroxyl is of minor importance (Figure 6) because cysteine, a known inhibitor of nitroxyl-dependent effect, has little influence on the vasorelaxant activity of FPTO and DCF (which does not generate detectable hydroxylamine; Table 2).

At concentrations above 0.1 μM, the effects of FPTO and FPDO on NA-precontracted rat aorta are not significantly affected by cysteine, oxyHb, and metHb, slightly increased in the presence of SOD and inhibited by ODQ (Figure 5 and Table 5). At 30–50 μM concentration, the effects of FPTO and FPDO are insensitive to ODQ apparently due to the competitive nature of inhibition of stimulated sGC by ODQ (Garthwaite et al., 1995). Hence, FPTO and FPDO induce smooth muscle relaxation via activation of sGC (similar to DCF) but NO is not apparently essential for their effects at concentrations above 1 μM in agreement with the suggested mechanism of sGC activation. Thus, relatively high concentrations of FPTO and FPDO can be effective stimulators of sGC under the conditions of enhanced formation of reactive oxygen species when thiol-dependent NO donors (organic nitrates, DCF, or partially SNP) would exhibit low efficacy because they require reduced thiols to generate NO and spontaneous donors (DEA/NO and SIN-1) require thiols for activation of the enzyme (Figure 3). Also, in this case functioning of endogenous NO-synthase can be severely altered (Wever et al., 1998) and vasorelaxant activity of FPTO is markedly potentiated by NO-synthase inhibition (Figure 5A).

Nitric oxide generation from FPTO (but not DCF) seems to play a minor role in the inhibition of platelet aggregation because FPDO has essentially the same activity (Figure 7). The crucial role of sGC is also questionable because enzyme inhibition by ODQ and methylene blue only partially blocks the antiplatelet effects of FPTO and FPDO (Table 6). This can be due to either low sensitivity of FPTO- and FPDO-activated human platelet sGC versus rat lung or smooth muscle enzyme to the ODQ- and methylene blue-dependent inhibition of this activation or to the involvement of other signalling molecules which are the potential targets of FPTO and FPDO. These alternative targets can act independently of cyclic GMP pathway because FPTO and FPDO increased the platelet cyclic GMP levels to the same extent as SNP and antiaggregatory activity of SNP is completely inhibited by ODQ.

In conclusion, we have shown that FPTO reacts with thiols generating NO-like species. The corresponding furazan, FPDO, also reacts with low molecular weight and protein thiols but NO-like species were not detected. FPTO and FPDO converted oxyHb to metHb and stimulated the activity of sGC apparently via NO-independent mechanism. FPTO is very potent vasorelaxant and both compounds are inhibitors of human platelet aggregation. In the body, they would be rapidly consumed by thiols (Table 1). This suggests that FPTO is the short-acting vasorelaxant agent. Moreover, the combination of two pharmacologically active moieties, furoxan and pyridazine di-N-oxide, markedly enhanced the activity of FPTO compared with representatives of the parent classes (DCF and FPDO, respectively) resulting in a unique mechanism of action. These properties of FPTO suggest that it possesses valuable pharmacological characteristics which may be beneficial for treatment of various cardiovascular disorders.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Professor A. Gasco and Professor V. Muronets for helpful discussions of our work. Authors are grateful to V. Yakunin for technical assistance during purification of rat lung guanylate cyclase. The work was supported by Russian Foundation for Basic Research.

Abbreviations

- cyclic GMP

cyclic 3′ : 5′ guanosine monophosphate

- DCF

3,4-dicyano-1,2,5-oxadiazole 2-oxide

- DEA/NO

diethylamine NONOate

- DMSO

dimethylsulphoxide

- DTNB

5,5′-dithiobis(dinitrobenzoic acid)

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- FPDO

4,7-dimethyl-1,2,5-oxadiazolo[3,4-d]pyridazine 5,6-dioxide

- FPTO

4,7-dimethyl-1,2,5-oxadiazolo[3,4-d]pyridazine 1,5,6-trioxide

- IBMX

3-isobutyl-1-methyl xanthine

- L-NOARG

L-NG-nitroarginine

- NA

noradrenaline

- ODQ

1H-[1,2,4]oxadiazolo[4,3-α]quinoxalin-1-one

- sGC

soluble guanylate cyclase

- SNP

sodium nitroprusside

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

References

- ARNELLE D.A., STAMLER J.S. NO+, NO•, and NO− donation by S-nitrosothiols: Implications for regulation of physiological functions by S-nitrosylation and acceleration of disulfide formation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1995;318:279–285. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1995.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ARNELLE D.R., STAMLER J.S.Detection of hydroxylamine Methods in Nitric Oxide Research 1996John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 541–554.ed. Feelisch, M. & Stamler, J.S. pp [Google Scholar]

- BRZEZINSKI B., ZUNDEL G. Formation of disulfide bonds in the reaction of SH group-containing amino acids with trimethylamine N-oxide. A regulatory mechanism in proteins. FEBS Lett. 1993;333:331–333. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80681-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CALVINO R., FRUTTERO R., GHIGO D., BOSIA A., PESCARMONA G.P., GASCO A. 4-Methyl-3-(arylsulfonyl)furoxans: a new class of potent inhibitors of platelet aggregation. J. Med. Chem. 1992;35:3296–3300. doi: 10.1021/jm00095a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHANDRASHEKAR T.K., KRISHNAN V. Optical and magnetic resonance studies of the interaction of metallo tetraphenylporphyrins with nitrobenzofuroxan. Can. J. Chem. 1983;62:475–480. [Google Scholar]

- CRAVEN P.A., IGNARRO L.J.Purification of soluble guanylyl cyclase and modulation of enzymatic activity Methods in Nitric Oxide Research 1996John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 209–219.ed. Feelisch, M. & Stamler, J.S. pp [Google Scholar]

- DIERKS E.A., BURSTYN J.N. Nitric oxide (NO), the only nitrogen monoxide redox form capable of activating soluble guanylyl cyclase. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1996;51:1593–1600. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(96)00078-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DI STILO A., GENA C., GASCO A.M., GASCO A., GHIGO D., BOSIA A. Glutathione potentiates cGMP synthesis induced by the two phenylfuroxancarbonitrile isomers in RFL-6 cells. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1996;6:2607–2612. [Google Scholar]

- DUTOV M.D., KHROPOV YU.V., KOTS A.YA., BELUSHKINA N.N., BUSYGINA O.G., SEVERINA I.S., SHEVELEV S.A.An activator of soluble guanylate cyclase 1997. Patent RU 2122582

- ELLMAN G.L., COURTNEY K.D., ANDRES V., JR, FEATHERSTONE R.M. A new and rapid colorimetric determination of acetylcholinesterase activity. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1961;7:88–95. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(61)90145-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FEELISCH M., SCHONAFINGER K., NOAK E. Thiol-mediated generation of nitric oxide accounts for the vasodilator action of furoxans. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1992;44:1149–1157. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(92)90379-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FEELISCH M., STAMLER J.S.Donors of nitrogen oxides Methods in Nitric Oxide Research 1996John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 71–117.ed. Feelisch, M. & Stamler, J.S. pp [Google Scholar]

- FERIOLI R., FOLCO G.C., FERRETTI C., GASCO A.M., MEDANA C., FRUTTERO R., CIVELLI M., GASCO A. A new class of furoxan derivatives as NO donors: mechanism of action and biological activity. Brit. J. Pharmacol. 1995;114:816–820. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb13277.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FRIEBE A., KOESLING D. Mechanism of YC-1-induced activation of soluble guanylyl cyclase. Mol. Pharmacol. 1998;53:123–127. doi: 10.1124/mol.53.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FRIEBE A., WEDEL B., HARTENECK C., FOERSTER J., SCHULTZ G., KOESLING D. Function of conserved cysteines of soluble guanylyl cyclase. Biochemistry. 1997;36:1194–1198. doi: 10.1021/bi962047w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FRUTTERO R., FERRAROTTI B., GASCO A., CALESTANI G., RIZZOLI C. A structural study of Tryller's and Schmitz's compounds and related substances. Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1988. pp. 1017–1023.

- GARTHWAITE J., SOUTHAM E., BOULTON C.L., NIELSEN E.B., SCHMIDT K., MAYER B. Potent and selective inhibition of nitric oxide-sensitive guanylyl cyclase by 1H-[1,2,4]oxadiazolo[4,3-a]quinoxalin-1-one. Mol. Pharmacol. 1995;48:184–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GASCO A., FRUTTERO R., SORBA G. NO-donors: an emerging class of compounds in medicinal chemistry. Il Farmaco. 1996;51:617–635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GERGEL D., CEDERBAUM A.I. Interaction of nitric oxide with 2-thio-5-nitrobenzoic acid: implications of the determination of free sulfhydryl groups by Ellmann's reagent. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1997;347:282–288. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.0352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GHIGO D., HELLER R., CALVINO R., ALESSIO P., FRUTTERO R., GASCO A., BOSIA A., PESCARMONA G. Characterization of a new compound, S35b, as a guanylate cyclase activator in human platelets. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1992;43:1281–1288. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(92)90504-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GHOSH P.B., EVERITT B.J. Furzanobenzofuroxan, furazanobenzothiadiazole and their N-oxides. New class of vasodilatory drugs. J. Med. Chem. 1974;17:203–206. doi: 10.1021/jm00248a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GREER M.L., SARKER H., MENDICINO M.E., BLACKSTOCK S.C. Azodioxide radical cations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:10460–10467. [Google Scholar]

- HOBBS A.J. Soluble guanylate cyclase: the forgotten sibling. TiPS. 1997;18:484–491. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(97)01137-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IGNARRO L. Heme-dependent activation of soluble guanylate cyclase by nitric oxide: Regulation of enzyme activity by porphyrins and metalloporphyrins. Sem. Hematol. 1989;26:63–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KERWIN J.F., JR, LANCASTER J.R., JR, FELDMAN P.L. Nitric oxide: a new paradigm for second messengers. J. Med. Chem. 1995;38:4343–4362. doi: 10.1021/jm00022a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIRILYUK I.A., UTEPBERGENOV D.I., MAZHUKIN D.G., FECHNER K., MERTSCH K., KHRAMTSOV V.V., BLASIG I.E., HASELOFF R.F. Thiol-induced nitric oxide release from 3-halogeno-3,4-dihydrodiazete 1,2-dioxides. J. Med. Chem. 1998;41:1027–1033. doi: 10.1021/jm960737s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KULIKOV A.S., MAKHOVA N.N., GODOVIKOVA T.I., GOLOVA S.P., KHMELNITSKII L.I. Reduction of furoxan ring to furazan in some carbonyl-substituted furoxans. Izv. AN SSSR (Chemistry) 1994. pp. 679–680.

- LOWRY O.H., ROSEBROUGH N.J., FARR A.L., RANDALL R.J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MEDANA C., ERMONDI G., FRUTTERO R., DI STILO A., FERRETTI C., GASCO A. Furoxans as nitric oxide donors. 4-Phenyl-3-furoxancarbonitrile: thiol-mediated nitric oxide release and biological evaluation. J. Med. Chem. 1994;37:4412–4416. doi: 10.1021/jm00051a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MONCADA S., REES D.D., SCHULZ R., PLAMER R.M. Development and mechanism of a specific supersensitivity to nitrovasodilators after inhibition of vascular nitric oxide synthesis in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1991;88:2166–2170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.6.2166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORLEY D., MARAGOS C.M., ZHANG X.Y., BOIGNON M., WINK D.A., KEEFER L.K. Mechanism of vascular relaxation induced by nitric oxide (NO)/nucleophile complexes, a new class of NO-based vasodilators. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1993;21:670–676. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199304000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORO M.A., RUSSELL R.J., CELLEK S., LIZASOAIN I., SU Y., DARLEY-USMAR V.M., RADOMSKI M.W., MONCADA S. cGMP mediates the vascular and platelet actions of nitric oxide: confirmation using an inhibitor of the soluble guanylyl cyclase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996;93:1480–1485. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.4.1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PASCHENKO S.V., KHRAMTSOV V.V., SKATCHKOV M.P., PLYUSNIN V.F., BASSENGE E. EPR and laser flash photolysis studies of the reaction of nitric oxide with water soluble NO trap Fe(II)-proline-ditiocarbamate complex. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1996;225:577–584. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PONZIO G., BERNARDI V. Ricerche sulle dioccime.-XXII. Gazz. Chim. Ital. 1925;55:67–72. [Google Scholar]

- REDDY D., REDDY N.S., CHANDRASHEKAR T.K. Optical, NMR and ESR evidence for the oxidation of cobalt porphyrins in the presence of an electron acceptor. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 1989;166:147–149. [Google Scholar]

- REDDY D., REDDY N.S., CHANDRASHEKAR T.K., VAN WILLIGEN H. Oxidation of Cobalt (II) tetrapyrroles in the presence of an electron acceptor. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1991. pp. 2097–2101.

- REHSE K., MULLER U. New NO donors with antithrombotic and vasodilating activities. Part 13. Pyrazol-4-one 1,2-dioxides and 4-hydroxyiminopyrazole 1,2-dioxides. Arch. Pharm. (Weinheim). 1995;328:765–769. [Google Scholar]

- SALOM J.B., BARBERA M.D., CENTERO J.M., ORTI M., TORREFROSA G., ALBORCH E. Relaxant effects of sodium nitroprusside and NONOates in rabbit basilar artery. Pharmacology. 1998;57:79–87. doi: 10.1159/000028228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHMIDT H.H.H.W., KELM M.Determination of nitrite and nitrate by the Griess reaction Methods in Nitric Oxide Research 1996John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 491–498.ed. Feelisch, M. & Stamler, J.S. pp [Google Scholar]

- SHVARTZ G.YA., GRIGORYEV N.B., SEVERINA I.S., RYAPOSOVA I.K., LAPITSKAYA A.C., VOLODARSKY L.B., TIKHONOV A.YA., KURBNIKOVA I.F., MAZHUKIN D.G., GRANIK V.G. Derivatives of 1,2-diazetine-1,2-dioxide as a new class of nitric oxide donors having vasodilatory activity. Khim.-Farm. Zh. 1994;28 No. 4:38–42. [Google Scholar]

- SEVERINA I.S., RYAPOSOVA I.K., VOLODARSKY L.B., MOZHUCHIN D.C., TICHONOV A.YA., SCHWARTZ G.YA., GRANIK V.G., GRIGORYEV D.A., GRIGORYEV N.B. Derivatives of 1,2-diazetidine-1,2-di-N-oxides a new class of soluble guanylate cyclase activators with vasodilatory properties. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Internat. 1993;30:357–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHRAMMEL A., BEHRENDS S., SCHMIDT K., KOESLING D., MAYER B. Characterization of 1H-[1,24]oxadiazolo[4,3-a]quinoxalin-1-one as a heme-site inhibitor of nitric oxide-sensitive guanylyl cyclase. Mol. Pharmacol. 1996;50:1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SNYDER H., BOYER N.E. The synthesis of furoxans from aryl methyl ketones and nitric acid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;77:4233–4238. [Google Scholar]

- SORBA G., MEDANA C., FRUTTERO R., CENA C., DI STILO A., GALLI U., GASCO A. Water soluble furoxan derivatives as NO prodrugs. J. Med. Chem. 1997;40:463–469. doi: 10.1021/jm960379t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STAMLER S.J., FEELISCH M.Preparation and detection of S-nitrosothiols Methods in Nitric Oxide Research 1996John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 521–540.ed. Feelisch, M. & Stamler, J.S. pp [Google Scholar]

- STEFFENS C., BEHREND R. Zur Kenntniss der Isomeren Verbindungen C6H8N4O4 aus Acetylmethylnitrolsaure. Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1899;309:241–253. [Google Scholar]

- STRELENKO YU.A., RAKITIN O.A., OGURTSOV V.A., GODOVIKOVA T.N., KHMELNITSKY L.I. NMR spectra and structure of N,N′-dioxide 4,7-dimethyl pyridazine[4,5-c]furoxan. Izv. AN SSSR (Chemistry) 1988. pp. 2848–2850.

- TAKAHASHI N., FISCHER V., SCHREIBER J., MASON R.P. An ESR study of nonenzymatic reactions of nitroso compounds with biological reducing agents. Free Rad. Res. Commun. 1988;4:351–358. doi: 10.3109/10715768809066903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ULRICH M., REHSE K., FEELISCH M.Pyrazolondioxide und pyrazolonoximidioxide 1995. Offenlegungsschrift DE 4322545-A1

- UTEPBERGENOV D.I., KHRAMTSOV V.V., VLASSENKO L.P., MARKEL A.L., MAZHUKIN D.G., TIKHONOV A.YA., VOLODARSKY L.B. Kinetics of nitric oxide liberation by 3,4-dihydro-1,2-diazete 1,2-dioxides and their vasodilatory properties in vitro and in vivo. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995;214:1023–1032. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WALSETH T.F., YUEN P.S.T., MOOS M.C. Preparation of α-[32P]-labeled nucleoside triphosphates, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, and cyclic nucleotides for use in determining adenylyl and guanylyl cyclases and cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase. Meth. Enzymol. 1991;195:29–44. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)95152-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEST D.X., JOHNSON A.A. Transition metal ion complexes of the conjugate base of 3,5-diphenyl 1-hydroxypyrazole 2-oxide. J. Inorg. Nucl. Chem. 1979;41:1101–1104. [Google Scholar]

- WEVER R.M.F., LUSCHER T.F., COSENTINO F., RABELINK T.J. Atherosclerosis and the two faces of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Circulation. 1998;97:108–112. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.1.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WINTERBOURN C.C. Oxidative reactions of hemoglobin. Meth. Enzymol. 1990;186:264–272. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)86118-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZAMORA R., GRZESIOK A., WEBER H., FEELISCH M. Oxidative release of nitric oxide accounts for guanylyl cyclase stimulating, vasodilator and anti-platelet activity of Piloty's acid: a comparison with Angeli's salt. Biochem. J. 1995;312:333–339. doi: 10.1042/bj3120333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]