Abstract

Small heat shock proteins protect cells from stress presumably by acting as molecular chaperones. Here we report on the functional characterization of a developmentally regulated, heat-inducible member of the Xenopus small heat shock protein family, Hsp30C. An expression vector containing the open reading frame of the Hsp30C gene was expressed in Escherichia coli. These bacterial cells displayed greater thermoresistance than wild type or plasmid-containing cells. Purified recombinant protein, 30C, was recovered as multimeric complexes which inhibited heat-induced aggregation of either citrate synthase or luciferase as determined by light scattering assays. Additionally, 30C attenuated but did not reverse heat-induced inactivation of enzyme activity. In contrast to an N-terminal deletion mutant, removal of the last 25 amino acids from the C-terminal end of 30C severely impaired its chaperone activity. Furthermore, heat-treated concentrated solutions of the C-terminal mutant formed nonfunctional complexes and precipitated from solution. Immunoblot and gel filtration analysis indicated that 30C binds with and maintains the solubility of luciferase preventing it from forming heat-induced aggregates. Coimmunoprecipitation experiments suggested that the carboxyl region is necessary for 30C to interact with target proteins. These results clearly indicate a molecular chaperone role for Xenopus Hsp30C and provide evidence that its activity requires the carboxyl terminal region.

INTRODUCTION

The class of molecular chaperones known as heat shock proteins (Hsps) have become recognized as a critical component of the intracellular environment (Morimoto et al 1994; Feige et al 1996). Chaperones including members of the Hsps assist the in vivo folding of proteins from their native state but do not remain to form a part of these proteins after assembly. An important function of Hsps is their ability to interact with and stabilize proteins that are partially unfolded in response to environmental stress and to maintain these proteins in a state that allows them to regain proper structure and function upon the return of favorable cellular conditions. A number of studies have suggested that chaperones such as Hsc70 and Hsp60 are involved in protein folding under normal cellular conditions whereas Hsp70 and small Hsps are synthesized to assist in the protection of cellular proteins during periods of stress (Feige et al 1996).

While the Hsp70 family is highly conserved in a wide range of organisms, small Hsps are quite divergent except for an amino acid domain that is found in α-crystallin (Arrigo and Landry 1994; Waters et al 1996). Unlike members of the large molecular weight Hsps, small Hsps and α-crystallins can form large polymeric structures that are believed to be necessary for function in vivo (Arrigo and Landry 1994; Waters et al 1996). A number of in vivo functions have been proposed for small Hsps including a role as molecular chaperone as well as an involvement in actin capping/decapping activity, cellular differentiation and modulation of redox parameters (Merck et al 1993; Huot et al 1996; Lee et al 1997; Liang et al 1997; Ehrnsperger et al 1997; Mehlen et al 1997; Muchowski et al 1997; Arrigo 1998; Mehlen et al 1999). It has been demonstrated in a variety of organisms that the synthesis of small Hsps can confer stress resistance (Arrigo and Landry 1994; Arrigo 1998; Jakob and Buchner 1994; Hartl 1996).

Developmental regulation of small Hsps has been described in a range of organisms including nematode, Drosophila, brine shrimp, mouse and rat (Stringham et al 1992; Marin et al 1993; Liang and MacRae 1999; Tanguay et al 1993; Mirkes et al 1996). Our laboratory and others have been involved in the analysis of small Hsp gene expression during early development of the frog, Xenopus laevis. Xenopus contains at least 2 families of small Hsps including the Hsp30s and basic small Hsps (Krone et al 1992; Ohan et al 1998). The most studied of these small Hsps are the Hsp30s, whose members are differentially expressed during development in a heat-inducible fashion. Hsp30A and Hsp30C genes are first inducible after 2 days of embryogenesis at the early tailbud stage while Hsp30D is not stress-inducible until 1 day later at the late tailbud stage (Krone et al 1992; Krone and Heikkila 1988; Krone and Heikkila 1989; Ohan and Heikkila 1995; Heikkila et al 1997). The differential pattern of Hsp30 gene expression was documented at the level of Hsp30 synthesis (Tam and Heikkila 1995). Recently, using in situ hybridization and immunolocalization studies we detected Hsp30 message and protein in the cement gland of unstressed tailbud embryos (Lang et al 1999). Upon heat shock there was a preferential accumulation of Hsp30 message and protein in selected tissues. The function of Hsp30 in the cement gland and in specific tissues of tailbud embryos following heat shock is not known. However, given the fact that the Xenopus Hsp30 protein possesses an α-crystallin domain, as determined from the gene sequence (Krone et al 1992), it is likely that these small Hsps function as molecular chaperones.

While small Hsp gene expression has been documented in a number of organisms (Arrigo and Landry 1994), relatively few have been examined with respect to small Hsp chaperone activity or the protein domains involved. In an attempt to understand the functional role of Xenopus Hsp30, we produced recombinant Hsp30C (30C) protein and examined its chaperone activity. In this study, we show that expression of Xenopus 30C in bacteria confers resistance against thermal challenge. Purified 30C which was recovered as large multimeric complexes interacted with unfolded protein, maintained it in a soluble form and inhibited its aggregation. Finally, truncation of the carboxyl terminus but not the amino terminus substantially reduced the ability of 30C to act as a molecular chaperone.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Preparation of recombinant protein

All restriction enzymes and primers were obtained from New England Biolabs and Mobix (McMaster University), respectively. The entire open reading frame of the Xenopus Hsp30C gene (Krone et al 1992) was obtained by polymerase chain reaction such that a BamHI restriction site was created at nucleotide 1120, just 5’ to the start codon and an EcoRI restriction site at nucleotide 1769, just 3’ to the translational stop codon. The resulting 675 bp fragment was gel purified, digested with BamHI/EcoRI and inserted into the corresponding sites of the pRSET expression vector (Invitrogen), containing an N-terminal 6x-histidine tag. Excluding the 6x-histidine residue, the predicted length of the protein was 214 amino acids. The resultant Hsp30C-pRSET construct was transformed into E coli BL21 (DE3) cells and grown at 37°C in M9 media overnight (Studier et al 1990). M9ZB media (Studier et al 1990) was then inoculated with the overnight culture and grown to an OD600 of 0.6. Hsp30 gene expression was induced by the addition of 0.4 mM isopropyl-B-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and allowed to grow for 4–5 hours (Studier et al 1990; Kroll et al 1993). As such, cells were collected and homogenized in guanidinium lysis buffer (6M guanidine hydrochloride, 20 mM sodium phosphate, 500 mM sodium chloride, pH 7.8). Following sonication and low speed centrifugation to remove cellular debris, bacterial lysates were applied to a nickel-coated ProBond column (Invitrogen) and 30C was purified under denaturing conditions according to the manufacturer's instructions. Eluted protein was dialyzed for 15 hours against protein dialysis buffer (PD buffer: 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 0.1 mM EDTA, 25 mM NaCl) and then concentrated in a Microsep microconcentrator (Pall Filtron). A mutant 30C protein missing the first 17 amino acids from the amino-terminus was produced by PCR-directed mutagenesis creating a PstI site at nucleotide 1176 and an EcoRI site at nucleotide 1769 after the translational stop of the Hsp30C gene. A 30C protein missing the last 25 amino acids from the carboxyl-terminus (C-30C) was made in a similar fashion by creating BamHI and HindIII sites at nucleotides 1120 and 1695, respectively. These PCR-amplified products were digested with the appropriate restriction enzymes, cloned into pRSET vectors, expressed and purified as described above for the full-length 30C protein. All PCR amplified fragments inserted into pRSET vectors were verified by DNA sequencing. The purity of protein preparations was checked using SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining.

Cell survival assays

E coli BL21(DE3) was transformed with pRSETB or pRSETB containing a genomic DNA fragment encoding the full length Hsp30C protein. Cells were grown overnight at 37°C in M9 minimal media and then transferred to M9ZB. After 4–5 hours of growth, cells were induced with 0.4 mM IPTG and incubated overnight at 37°C. Overnight cultures were diluted 1:500 into preheated LB media and placed at 60°C for 3 hours. Aliquots from cultures were collected at selected time intervals and plated onto LB agar. Colony forming units, indicative of the number of cells that survived the heat treatment, were determined after incubation overnight at 37°C.

Polyclonal antibody production

Recombinant 30C protein was produced in bacterial cells and purified as described above. Following a pre-immune bleed, a female New Zealand white rabbit was immunized with a subcutaneous injection of 30C mixed in Freunds complete adjuvent (Sigma, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). Subsequent booster injections were given at regular intervals. Blood was collected from the marginal ear vein, allowed to clot and centrifuged at 10 000 × g to isolate the serum fraction. A 1.5 mL nickel affinity column containing bound 30C (via the N-terminal 6 histidine residues) was used for affinity purification of anti-30C antibody from the rabbit anti-sera (Gu et al 1994). Bound antibody was eluted from the column and concentrated using a microconcentrator as described above. Antibody titre was tested against immunoblots of extract obtained from control and heat shock Xenopus A6 kidney epithelial cultured cells (Tam and Heikkila 1995; Ohan et al 1998) as well as recombinant 30C protein.

Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunodetection

SDS-PAGE was performed in either 10% or 12% acrylamide gels using the BioRad Mini Protean II system. Proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore) using a BioRad Mini Trans-Blot Transfer system. Immunodetection was carried out using an affinity purified polyclonal anti-30C antibody. Blots were incubated with horse-radish peroxidase conjugated secondary IgG (Roche), and detected using an ECL chemiluminescence kit (Amersham) as described by the manufacturer.

Size exclusion chromatography

Size estimation of the 30C complex and luciferase was accomplished by size exclusion chromatography. Approximately 5 mg of 30C protein or luciferase (Promega) was loaded onto a 35 × 1.6 cm size exclusion column containing Sepharose CL4B beads (Pharmacia). The column was calibrated according to instructions provided by the manufacturer using molecular weight standards: thyroglobin (669 kDa), ferritin (440 kDa), aldolase (158 kDa), and blue dextran to determine the void volume. Chromatography was performed at room temperature in PD buffer and the absorbances at 280 nm of collected fractions were measured in a Beckman DU-7 spectrophotometer. To determine the presence of 30C protein, selected eluant fractions were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE, immunoblotted and detected using the anti-30C antibody.

Thermal aggregation assays

Aggregation assays were conducted essentially as described by Buchner et al (1998). Either citrate synthase or luciferase at 150 nM monomer concentration was mixed with various molar amounts of 30C protein or incubated alone in a 50 mM HEPES-KOH buffer, pH 7.5, and heated at 42°C. Light scattering was determined at regular intervals in a Beckman DU7 spectrophotometer at 320 nm. An increase in absorbance was indicative of protein aggregation.

Thermal inactivation experiments

CS at a concentration of 150 nM was incubated in the presence or absence of either 150 or 750 nM 30C at 42°C for 25 minutes and then placed at 22°C. CS activity was measured based on the condensation of oxaloacetic acid and acetyl-CoA to citrate and coenzyme A (Buchner et al 1991).

Luciferase solubility assay

Luciferase (150 nM) was incubated alone or with 750 nM of either 30C, N-30C or C-30C in 50 mM HEPES-KOH buffer, pH 7.5, and incubated at 42°C for 30 minutes or kept at 22°C. An aliquot was removed and designated as the total fraction. Samples were then centrifuged at 10 000 × g and an aliquot from the supernatant fraction was collected. A pellet fraction was collected after dissolving the pellet in 1X SDS-PAGE sample buffer (BioRad). An equal volume of each sample was subjected to SDS-PAGE on a 10% acrylamide gel and immunoblotted as described above using a polyclonal anti-luciferase primary antibody (Cortex).

Immunoprecipitation analysis

Luciferase at a concentration of 150 nM was incubated with 750 nM of 30C, N-30C or C-30C in 50 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.5, buffer at 22°C or at 42°C for 30 minutes. Samples were initially pre-incubated with protein A-Sepharose (Sigma) in IP buffer (1.0 M NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% deoxycholic acid, 0.1% SDS) containing 100 μg/mL ovalbumin. Anti-30C antibody was added to the supernatant and mixed at 4°C for 1 hour. Protein A-Sepharose pellets from each mixture were washed 3 times for 10 minutes each in IP buffer, and twice for 15 minutes in HIP buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 300 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100). Pellets were boiled in 1X SDS-PAGE sample buffer and then subjected to SDS-PAGE on 10% acrylamide. Recombinant luciferase was included as a control. Immunodetection was carried out with a polyclonal anti-luciferase antibody. Blots were stripped and re-probed with the anti-30C antibody.

RESULTS

Production of recombinant Hsp30C protein and polyclonal antibody

Examination of the chaperone activity of Xenopus Hsp30C required the preparation of recombinant Hsp30C protein and an anti-Hsp30 antibody. To accomplish this, the complete open reading frame of the Xenopus Hsp30C gene was amplified by PCR and inserted into the pRSETB expression vector. Following transformation into E coli strain BL21(DE3) and induction with IPTG, recombinant Hsp30C (30C) was detected in the bacterial lysate after 4 hours (Fig 1). After washing and eluting the lysate through a nickel affinity column, 30C was recovered in a purified form (Fig 1, 30C purified lane) and was used in the production of a polyclonal anti-30C antibody. Rabbit serum containing the anti-30C antibody was affinity purified and tested against protein extracts of control and heat shocked Xenopus A6 kidney epithelial cells (Fig 2). The purified antibody reacted with Hsp30 protein as well as recombinant 30C in a specific manner and did not cross-react with any other endogenous A6 cell proteins. Preimmune serum did not recognize Xenopus Hsp30 or any other protein in Xenopus tissues or bacterial extract (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Expression and purification of Hsp30C recombinant protein from E coli. Total bacterial protein from E coli BL21(DE3) cells containing either the expression vector (pRSETB) or the vector with a DNA insert containing the entire Hsp30C gene open reading frame (30C) were collected either before or after 4 hours of IPTG addition. Protein was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and visualized by Coommassie blue staining. Total bacterial lysates containing 30C were passed over a nickel affinity column and 30C was purified from residual bacterial contaminants as described in Experimental Procedures. Five μg of purified 30C was loaded onto the gel. The asteriks indicate the location of 30C. Molecular mass markers in kDa are indicated on the left side of the figure

Fig. 2.

Production of polyclonal anti-30C antibody. Recombinant 30C was injected into rabbits to produce a polyclonal anti-30C antibody. The antibody was affinity purified from crude sera using a nickel affinity column and tested for specificity by immunoblot analysis with protein from control (22°C; lane 1, 15 μg) and heat shocked (33°C for 2 hours; lane 2, 5 μg; lane 3, 15 μg) Xenopus A6 tissue culture cells. Molecular mass markers in kDa are indicated on the left side of the figure

Hsp30C protects bacterial cells from thermal stress

As an initial step in the analysis of Hsp30 chaperone function, the thermoresistance of E coli cells which overexpressed 30C was examined. As shown in Figure 3, E coli BL21 cells or those containing the vector pRSETB were unable to withstand a severe thermal stress of 60°C over a 3 hour period. These cells died quickly with less than 3–4% surviving after only 45 minutes. In contrast, 45% of E coli BL21 cells overexpressing 30C survived at this time point. After 2–3 hours of thermal stress approximately 20% of E coli cells overexpressing 30C were still viable.

Fig. 3.

Effect of thermal stress on the survival of E coli cells overexpressing 30C. E coli BL21 (DE3) cells were transformed with pRSETB expression vector or pRSETB with a DNA insert containing the open reading frame for Hsp30C. Thermotolerance assays were performed as described in Experimental Procedures. Similar results were obtained for 3 trials and the data were expressed as a percentage of the number of colony forming units at t = 0 hours. ▵: BL21(DE3), □: BL21(DE3) + pRSETB, ○: BL21(DE3) + pRSETB/Hsp30C

Recombinant Hsp30C forms large multimeric complexes

Size exclusion chromatography on a Sepharose CL-4B column and immunoblot analysis were used to estimate the size of 30C complexes (Fig 4). Recombinant Hsp30C formed large multimeric complexes ranging in size from 130 kDa to more than 669 kDa with a major peak at an estimated size of 800–900 kDa and a possible secondary peak at 160 kDa as indicated by the shape of the curve in this region (Fig 4A; compare fractions 46–52) and the corresponding immunoblot analysis (Fig 4B; compare fractions 45 to 52). While fractions 60–63 showed the presence of UV absorbing material we did not detect any cross-reactivity with the anti-30C antibody which may indicate the presence of residual bacterial proteins. Although data are shown for only the heat-treated sample both heat-treated and non-heat-treated 30C had identical elution profiles indicating that the oligomeric form of 30C remained unchanged upon incubation at elevated temperatures. These results are similar to studies examining recombinant murine Hsp25 (Ehrnsperger et al 1997; Behlke et al 1991) as well as a 16 kDa small Hsp from Myocbacterium tuberculosis (Chang et al 1996) and demonstrate that small Hsps are not themselves heat sensitive and as such, do not aggregate further upon heating.

Fig. 4.

Elution profile of 30C from a Sepharose CL-4B column. (A) 30C heated at 42°C for 50 minutes was applied to a Sepharose CL-4B column maintained at 22°C. Eluant fractions were measured by spectrophotometry at 280 nm. Calibration standards are indicated above the curve: thyroglobin (669 kDa), ferritin (440 kDa), aldolase (158 kDa). Void volume (Vo) was determined using blue dextran. (B) an equal amount of eluant from each fraction was analyzed by immunoblot analysis. The presence of 30C in the different fractions was detected using a polyclonal anti-30C antibody

30C inhibits heat-induced citrate synthase aggregation

To assess the ability of 30C to function as a molecular chaperone, we utilized a citrate synthase (CS) in vitro aggregation assay. Heat-induced aggregation of CS, as determined by the amount of light scattering at 320 nm, developed rapidly and irreversibly with approximately 90% aggregation occurring after 30 minutes at 42°C (Fig 5). Incubation with an equimolar amount of 30C resulted in only 30% CS aggregation in the same amount of time. A 2:1 molar ratio of 30C:CS almost completely inhibited CS aggregation. Further increases in the molar ratio of 30C: CS had similar effects as the 2:1 (30C:CS) ratio. When a solution of CS was treated at 42°C for 10 minutes followed by the addition of 30C, a further increase in aggregation was prevented while pre-existing CS complexes remained irreversibly aggregated (data not shown). Finally, the chaperone activity of 30C was not affected by the addition of ATP (data not shown). In contrast to 30C, incubation of bovine serum albumin (BSA) or immunoglobin G (IgG) with CS at molar ratios of 5:1 did not inhibit aggregation.

Fig. 5.

Prevention of heat-induced aggregation of CS by 30C. Effect of various molar quantities of 30C (□, 0.1 μM; ▵, 0.2 μM; ○, 0.5 μM) and IgG (•, 0.5 μM) and BSA (▴, 0.5 μM) on heat-induced aggregation of CS (x, 0.1 μM) at 42°C was determined by means of a light scattering assay. Data are representative of 4–6 trials and were calculated as a percentage of the maximum aggregation of CS after 60 minutes and were expressed as the mean ±SD

To assess the ability of 30C to prevent thermal inactivation of CS enzyme activity, CS was incubated at 42°C in either the presence or absence of 30C (Fig 6). After 5 minutes of heat treatment, approximately 25% of total CS activity remained. In comparison, when 30C was incubated with CS at a 1:1 molar ratio, 38% of total CS enzyme activity remained after 5 minutes. While CS enzyme activity did not increase in the presence of 30C, approximately 15–20% of CS activity was retained after 25 minutes at 42°C as well as during an additional recovery period at 22°C. Further increases in the molar ratio of 30C:CS did not alter these results. These data demonstrate that 30C had a minimal effect on preventing CS enzyme inactivation and were unable to reactivate denatured CS.

Fig. 6.

30C has a minimal effect on the prevention of thermal inactivation of CS. CS was heated at 42°C either alone (X) or with 30C in a 1:1 (○) or 5:1 (•)30C:CS molar ratio as described in Experimental Procedures. The enzymatic activity of CS from each mixture was expressed as a percentage of initial CS activity. The data are representative of 4–6 trials and are shown as the mean ±SD

The carboxyl end of 30C is required for chaperone activity and 30C stability

In an initial approach to identify regions of 30C that are involved in chaperone activity, PCR targeted mutagenesis was used to create short terminal deletions. The N-terminal mutant, N-30C, in which the first 17 amino acids were deleted and the C-terminal mutant, C-30C, in which the last 25 amino acids were removed had apparent molecular masses of 29 kDa and 26 kDa, respectively, as determined by SDS-PAGE (Fig 7). These deletions were determined to be outside of the region containing the small hsp α-crystallin domain as defined by Wistow (1985) and De Jong (1988). The identity and size of both N- and C-terminal mutants was verified by immunoblot analysis using the anti-30C antibody (data not shown). In most experiments, the 6 histidine tag, added at the carboxyl terminus from the pRSET vector, was not removed from these recombinant proteins and for purposes of simplicity were not included in the calculation of their total amino acid number. Furthermore, removal of the histidine tag had no effect on the chaperone activity of the different mutants as outlined below. In in vitro aggregation assays, a N-30C prevented thermal aggregation of CS as effectively as full length 30C (Fig 8). Both of these recombinant proteins inhibited heat-induced aggregation of CS by 90% after 60 minutes. However, deletion of amino acids from the carboxyl end resulted in a substantial loss of chaperone activity since C-30C suppressed heat-induced CS aggregation by only 40% after 60 minutes. As mentioned previously, removal of the histidine tag had no effect on the chaperone activity of the full length or mutant Hsp30C proteins (data not shown). These experiments indicate that the carboxyl region of Hsp30C is required for the inhibition of heat-induced aggregation of CS.

Fig. 7.

Production of 30C terminal deletion mutants. Recombinant 30C mutants missing either the first 17 amino acids (N-30C) or the last 25 amino acids (C-30C) were expressed and purified as for 30C and described in Experimental Procedures. The 30C, N-30C and C-30C proteins were separated using SDS-PAGE and stained with Commassie blue. Molecular mass markers in kDa are indicated on the vertical axis

Fig. 8.

The carboxyl end of 30C is involved in the prevention of heat-induced CS aggregation. CS was incubated alone (+) or with 30C (○), N-30C (□) or C-30C (▵) at a 5:1 molar ratio (Hsp (0.5 μM): CS (0.1 μM)) at 42°C and assayed by light scattering as outlined in Experimental Procedures. Data were calculated as a percentage of the maximum aggregation of CS after 60 minutes and was expressed as the mean ±SD

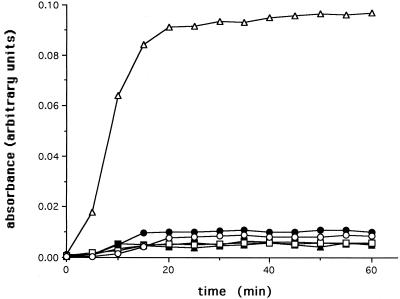

Analysis of the effect of heat on the multimerization of the C-30C terminal deletion mutant by size exclusion chromatography was not possible because heating of highly concentrated amounts of C-30C resulted in precipitation from solution. This was in contrast to both 30C and N-30C in which heat had no effect on oligomeric size of either of these recombinant proteins. This prompted an examination of the ability of 30C proteins to self-aggregate. When low concentrations (0.8 μmol) of recombinant protein identical to those used in CS aggregation assays were heated, no increase in the amount of light scattering was observed in the full length or mutant 30C proteins (Fig 9). However, at a concentration of 300 μmol, C-30C aggregated to levels almost 10-fold higher than 30C and N-30C. These results suggest that the carboxyl region is necessary for 30C to remain soluble.

Fig. 9.

The carboxyl region of 30C is required for solubility. The extent of heat-induced aggregation of 30C, N-30C and C-30C at 42°C was examined using light scattering assays as detailed in Experimental Procedures. •, 0.8 μM 30C; ○ 300 μM 30C; ▪, 0.8 μM of N-30C; □, 300 μM of N-30C; ▴, 0.8 μM of C-30C; ▵ 300 μM of C-30C

30C inhibits aggregation and maintains the solubility of heat-treated luciferase

The ability of 30C, N-30C and C-30C to inhibit heat-induced aggregation of other target proteins such as luciferase (LUC) was also investigated (Fig 10A). LUC was highly sensitive to heat since almost all of this enzyme aggregated within 10 minutes of heating at 42°C. At molar ratios of 5: 1 both 30C and N-30C effectively inhibited the aggregation of LUC after 60 minutes by 93% and 76%, respectively. However C-30C was not effective in inhibiting CS aggregation. Similar results were observed with the enzyme aldolase and malate dehydrogenase (data not shown). These results suggest that 30C was not selective in its ability to prevent aggregation of proteins that unfold during heat stress.

Fig. 10.

30C maintains heat-treated LUC in a soluble state. (A) LUC was incubated alone (+) or with 30C (○), N-30C (□, or C-30C (▵) in a 5:1 molar ratio (Hsp(0.5 μM): LUC(0.1 μM)) at 42°C. Data were calculated as a percentage of the maximum aggregation of LUC after 60 minutes and were expressed as the mean ±SD. (B) Immunoblot analysis of LUC in the total, T, supernatant, S, and pellet, P, fractions of control and heat-treated mixtures from panel A as described in Experimental Procedures

The availability of an anti-LUC antibody permitted immunoblot analysis of the effect of 30C on heat-induced aggregation of LUC. As shown in Figure 10B, LUC kept at 22°C remained in the supernatant with a smaller amount in the pellet fraction. Upon heating at 42°C, LUC became insoluble and was detectable only in the pellet fraction. The presence of either 30C or N-30C at a 5:1 ratio resulted in most of the heat-treated LUC remaining in the supernatant fraction. When LUC was heated with C-30C, most of the LUC was insoluble and located in the pellet fraction. Thus, 30C maintains the solubility of luciferase during heat treatment.

The data obtained from the aggregation experiments suggested that a stable complex was formed between 30C and LUC. To verify such an interaction, size exclusion chromatography and immunoblot analysis was performed. Figure 11A demonstrates the position of non-heat-treated LUC and 30C (verified by immunoblotting) when applied separately onto the column. Incubation of 30C at 42°C in the presence of LUC at a 5:1 molar ratio, previously shown to prevent heat-induced aggregation of LUC (Fig 10A), resulted in the formation of a single peak that eluted in the void volume. Sequential detection with an anti-LUC antibody and an anti-30C antibody demonstrated the presence of LUC in each fraction containing 30C (Fig 11B). Additionally, interaction of 30C, N-30C, and C-30C with LUC was assessed in coimmunoprecipitation experiments using the anti-30C antibody (Fig 12). These studies revealed that LUC (top panel) coprecipitated with 30C (bottom panel) when incubated together at 42°C but not when incubated at 22°C. Similar results were observed when LUC was incubated with N-30C. Therefore results from both the chromatography experiments and the coimmunoprecipitation experiments indicated that 30C and N-30C recognized and bound unfolded proteins. When LUC was incubated with C-30C, a very small amount of LUC coprecipitated with C-30C. These results suggest that C-30C was impaired in its ability to recognize and bind heat-treated LUC.

Fig. 11.

30C binds to LUC during heat treatment. (A) LUC was heated at 42°C with 30C in a 5:1 (30C:LUC) molar ratio as described in Experimental Procedures. Size exclusion chromatography was used to characterize the formation of 30C and LUC into large oligomeric complexes. Vo indicates the position of the void volume as determined by blue dextran. ○: non-heat-treated 30C, □: non-heat-treated luciferase, ▴: heat-treated 30C and LUC. (B) 30C is present in each eluant fraction containing LUC. An equal amount from selected eluant fractions obtained from size exclusion chromatography of heat-treated 30C and LUC as indicated above was immunoblotted using an anti-LUC or an anti-30C antibody as described in Experimental Procedures

Fig. 12.

The 30C carboxyl region is necessary for association with heat-treated LUC. LUC was mixed with 30C, N-30C or C-30C in a 5:1 (30C: LUC) molar ratio and heated at 42°C (hs) or kept at 22°C (con) for 30 minutes. Coimmunoprecipitation with anti-30C antibody was performed as described in Experimental Procedures. The presence of LUC (upper panel) and 30C (lower panel) as determined by immunoblot analysis is indicated by arrows A and B, respectively. Location of IgG is indicated by the asterisk.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we examined the molecular chaperone properties of the Xenopus small Hsp family member, Hsp30C. The coding region of the Xenopus Hsp30C gene was cloned into a plasmid vector and overexpressed in bacteria. Interestingly, bacteria which expressed the recombinant protein 30C were more thermoresistant to a severe thermal challenge of 60°C than either nontransformed bacteria or those containing only the plasmid vector. The acquisition of cellular thermotolerance in bacteria by expression of eukaryotic small Hsp genes has been documented with Artemia salina p26 (Liang and MacRae 1999) and human αB crystallin (Muchowski and Clark 1998). All of these studies are in parallel with the ability of small Hsp transgenes such as Hsp27 and α-crystallin to protect eukaryotic cells from environmental stress (Arrigo and Landry 1994; Arrigo 1998; Jakob and Buchner 1994).

The protection of bacterial cells from thermal stress by 30C suggested that it may act as a molecular chaperone. In order to gain more insight into the physical properties and function of 30C, this protein was purified and used in chaperone assays. Purified 30C, which was obtained as large complexes ranging in size from 130 kDa to approximately 800–900 kDa as determined by size exclusion chromatography, was resolved as 30 kDa protein by means of SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis. Comparable results with respect to multimerization have been reported with recombinant human αB-crystallin in which gel filtration and laser light scattering analysis in conjunction with 3 dimensional variance mapping showed the presence of a range of molecular masses (Haley et al 1998). Their results suggested that subunits of αB-crystallin do not oligomerize in a specific manner and as such, do not have a defined quartenary structure. Given the size range of multimeric complexes that were found with 30C, it is possible that this Xenopus small Hsp behaves in a similar fashion in vitro. However, a different situation may exist in vivo since Xenopus Hsp30 aggregates are composed of a number of different isoforms in addition to Hsp30C and possibly other proteins such as Hsp70 which may affect complex formation (Ohan et al 1998). Additionally, while our results indicated that both heat- and non-heat-treated 30C are similar in size, we cannot rule out the possibility of differences in secondary or tertiary structure in these 2 samples.

Xenopus 30C displayed a number of properties characteristic of a small Hsp molecular chaperone including the ability to inhibit heat-induced aggregation of CS and LUC in an ATP-independent manner. Furthermore using luciferase and an anti-luciferase antibody in gel filtration and coimmunoprecipitation assays, it was found that 30C interacted with heat-treated LUC forming 30C-LUC complexes which remained soluble at elevated temperatures. Thus, Xenopus 30C appears to function as a molecular chaperone by binding to unfolded proteins and maintaining them in a soluble form. This property has been reported for mouse Hsp25 and bovine αA-crystallin (Ehrnsperger et al 1997; Smulders et al 1996). While 30C inhibited heat-induced enzyme aggregation, it was not very efficient in preventing heat-induced inactivation of CS enzyme activity, even when high concentrations of 30C were used. Only 15% to 20% of CS enzyme activity remained after incubation with 30C at 42°C. The inability of small Hsps to effectively protect CS from heat inactivation has been found with small Hsps from pea and mouse (Ehrnsperger et al 1997; Lee et al 1995).

As an initial approach to determining the protein domains responsible for the molecular chaperone activity of 30C, we created 2 truncated versions of this protein. The mutant, N-30C, lacked the first 17 amino acids while the other mutant, C-30C had the last 25 amino acids omitted. Both of these mutants retained the α-crystallin domain, a region that is highly conserved among shsps of different species (Arrigo and Landry 1994). N-30C was fully functional since it behaved almost identically to 30C in the inhibition of heat-induced aggregation of both CS and LUC as well as maintaining LUC solubility throughout the duration of heat treatment. In contrast, truncation of the C-terminus was detrimental to the function of 30C as a molecular chaperone since it was inefficient at inhibiting enzyme aggregation and maintaining solubility. Comparable results were reported with mammalian αA crystallin in which removal of approximately 10–17 amino acids from the carboxyl end resulted in a substantial loss of chaperone-like activity (Takemoto et al 1993; Andley et al 1996). In contrast, recent studies with nematode small Hsp revealed that elimination of the last 16 amino acids of the C-terminus had no effect on chaperone activity whereas deletions in the N-terminus suppressed chaperone activity (Leroux et al 1997). Thus, Xenopus 30C appears to function more like mammalian αA-crystallin than nematode small Hsps. The reason for this difference is unclear at present and may suggest differences in small Hsps across species. It is also possible that there are differences in the chaperone properties of small Hsps within species. In Xenopus there exists at least 2 different families of small Hsps including the Hsp30 family, and the recently described basic small Hsps (Krone et al 1992; Ohan et al 1998; Heikkila et al 1997). The C-terminal end of small Hsps appears to be important for chaperone function in vivo since the enhanced stress resistance of COS cells transfected with Drosophila Hsp27 was lost when 42 amino acids were removed from the C-terminal end of Hsp27 (Mehlen et al 1993). Future studies will determine whether there are functional differences in the protein domains of these Xenopus small Hsp families in vivo.

Another interesting property of C-30C which was not shared by 30C or N-30C was its precipitation from solution at high concentrations (≥300 μM) and elevated temperatures. This finding parallels the behaviour of nematode Hsp16–2 in which truncation of the C-terminus resulted in an unstable protein that precipitates from solution after freezing and thawing (Leroux et al 1997). Similarly, removal of 17 amino acids from the C-terminal end of human αA-crystallin results in reduced solubility (Andley et al 1996). The present study supports the contention first reported with α-crystallin and later with mouse and nematode small Hsp that the solubility of this class of proteins resides in the C-terminal end (Leroux et al 1997; Smulders et al 1996; Carver et al 1992; Carver et al 1995). In these latter studies, it was determined that the carboxyl end consisted of mostly polar residues. Furthermore, the insertion of a highly hydrophobic residue into the carboxyl end of bovine αA crystallin reduced chaperone-like activity (Smulders et al 1996). An examination of the Xenopus Hsp30 carboxyl end (Krone et al 1992) revealed that the last 25 residues contain 16 polar amino acids with 11 of these polar residues occurring in the last 13 amino acids. Thus, Xenopus Hsp30 contains a set of polar amino acids at the carboxyl end which is likely involved in maintaining its own solubility and that of the target protein. Removal of 25 aa from the C-terminus of 30C may lead to further structural alterations that prevent 30C from interacting with client proteins. Additionally, these 25 aa may be necessary for the interaction of 30C with target cellular proteins.

In conclusion this study has shown that Xenopus small Hsp, Hsp30C, can act as a molecular chaperone and prevent heat-induced CS and LUC aggregation by binding to these target proteins and maintaining them in solution. Furthermore, the C-terminal residues appear to be involved in this phenomenon. Our study supports a model in which small Hsps sequester unfolded proteins and maintain them in a soluble state (Ehrnsperger et al 1997; Smulders et al 1996; Carver et al 1995). Other studies have suggested that since small Hsps have minimal refolding ability, other chaperones such as Hsp40, Hsp70 and others are involved in this process (Beissinger and Buchner 1998).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council grant to J.J. Heikkila. The authors wish to thank Garret Lee, University of Arizona, as well as Miriam Heynen and Philippe Mercier for their excellent advice.

REFERENCES

- Andley UP, Mathur S, Griest TA, Petrash JM. Cloning, expression, and chaperone-like activity of human αA-crystallin. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:31973–31980. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.50.31973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrigo A-P. Small stress proteins: chaperones that act as regulators of intracellular redox state and programmed cell death. J Biol Chem. 1998;379:19–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrigo AP, Landry J 1994 Expression and function of the low-molecular-weight heat shock proteins. In: The biology of heat shock proteins and molecular chaperones, edited by Morimoto RI, Tissieres A, Georgopoulos C. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: Cold Spring Harbor, NY, p 335–373. [Google Scholar]

- Behlke J, Lutsch G, Gaestel M, Bielka H. Supramolecular structure of the recombinant murine small heat shock protein hsp25. FEBS Lett. 1991;288:119–122. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)81016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beissinger M, Buchner J. How chaperones fold proteins. Biol Chem. 1998;379:245–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchner J, Grallert H, Jakob U. Analysis of chaperone function using citrate synthase as nonnative substrate protein. Methods Enzymol. 1998;290:323–338. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(98)90029-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver JA, Aquilina JA, Truscott RJ, Ralston GB. Identification by 1H NMR spectroscopy of flexible C-terminal extension in bovine lens alpha-crystallin. FEBS Lett. 1992;311:143–149. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)81386-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver JA, Guerreiro N, Nicholls KA, Truscott RJ. On the interaction of alpha-crystallin with unfolded proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1995;1252:251–260. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(95)00146-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Z, Primm TP, Jakana J, Lee IH, Serysheva I, Chiu W, Gilbert HF, Quiocho FA. Mycobacterium tuberculosis 16-kDa antigen (Hsp16.3) functions as an oligomeric structure in vitro to suppress thermal aggregation. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:7218–7223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jong WW, Leeunissen JA, Leener PJ, Zweers A, Versteeg M. Dogfish alpha- crystallin sequences. Comparisons with small heat shock protein and Schistosoma egg antigen. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:5141–5149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrnsperger M, Graber S, Gaestel M, Buchner J. Binding of non-native protein to Hsp25during heat shock creates a reservoir of folding intermediates for reactivation. EMBO J. 1997;16:221–229. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.2.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feige U, Morimoto RI, Yahara I, and Polla BS 1996 Stress-Inducible Cellular Responses. Birkhauser Verlag, Switzerland. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu J, Stephenson CG, Iadarola MJ. Recombinant proteins attached to a nickel-NTA column: Use in affinity purification of antibodies. Bio Techniques. 1994;17:257–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haley DA, Horwitz J, Stewart PL. The small heat shock protein, αB-crystallin, has variable quaternary structure. J Mol Biol. 1998;277:27–35. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartl FU. Molecular chaperones in cellular protein folding. Nature. 1996;381:571–579. doi: 10.1038/381571a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heikkila JJ, Ohan N, Tam Y, Ali A. Heat shock protein gene expression during Xenopus development. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1997;53:114–121. doi: 10.1007/PL00000573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huot JF, Houle F, Spitz DR, Landry J. Hsp27 phosphorylation-mediated resistance against actin fragmentation and cell death induced by oxidative stress. Cancer Res. 1996;56:273–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakob U, Buchner J. Assisting spontaneity: the role of Hsp90 and small Hsps as molecular chaperones. Trends Biochem Sci. 1994;19:205–211. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(94)90023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krone PH, Heikkila JJ. Analysis of Hsp 30, Hsp 70, and ubiquitin gene expression in Xenopus laevis tadpoles. Development. 1988;103:59–67. doi: 10.1242/dev.103.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krone PH, Heikkila JJ. Expression of microinjected hsp 70/CAT and hsp 30/CAT chimeric genes in developing Xenopus laevis embryos. Development. 1989;106:271–281. doi: 10.1242/dev.106.2.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krone PH, Snow A, Ali A, Pasternak JJ, Heikkila JJ. Comparison of the regulatory and structural regions of the Xenopus laevis small heat-shock protein encoding gene family. Gene. 1992;110:159–166. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90643-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroll DJ, Abdel-Malek , Abdel-Hafiz H, Marcell T, et al. A multifunctional prokaryotic protein expression system: overproduction, affinity purification and selective detection. DNA Cell Biol. 1993;12:441–453. doi: 10.1089/dna.1993.12.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang L, Miskovic D, Fernando P, Heikkila JJ. Spatial pattern of constitutive and heat shock-induced expression of the small heat shock protein gene family, Hsp30, inXenopus laevis tailbud embryos. Dev Genet. 1999;25:365–374. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6408(1999)25:4<365::AID-DVG10>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee GJ, Pokala N, Vierling E. Structure and in vitro molecular-chaperone activity of cytosolic small heat shock proteins from pea. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:10432–10438. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.18.10432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee GJ, Roseman AM, Saibil HR, Vierling E. A small heat shock protein stably binds heat-denatured model substrates and can maintain a substrate in a folding-competent state. EMBO J. 1997;16:659–671. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.3.659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leroux MR, Melki R, Gordon B, Batelier G, Candido EPM. Structure-function studies on small heat shock protein oligomeric assembly and interaction with unfolded polypeptides. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:24646–24656. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.39.24646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang P, Amons R, Clegg JS, MacRae TH. Purification, structureand in vitro molecular-chaperone activity of Artemia p26, a small heat-shock/α-crystallin protein. Eur J Biochem. 1997;243:225–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.0225a.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang P, MacRae TH. The synthesis of small heat shock/α-crystallin protein in Artemia and its relationship to stress tolerance during development. Dev Biol. 1999;207:445–456. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin R, Valet JP, Tanguay RM. Hsp 23 and Hsp 26 exhibit distinct spatial and temporal patterns of constitutive expression in Drosophila adults. Dev Genet. 1993;14:69–77. doi: 10.1002/dvg.1020140109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehlen P, Briolay J, Smith L, Diaz-Latoud C, Fabre N, Pauli D, Arrigo AP. Analysis of the resistance to heat and hydrogen peroxide stresses in COS cells transiently expressing wild type or deletion mutants of the Drosophila 27-kDa heat shock protein. Eur J Biochem. 1993;215:277–284. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehlen P, Coronas V, Ljubic-Thibal V, Ducasse C, Granger L, Jourdan F, Arrigo A-P. Small stress protein Hsp27 accumulation during dopamine-mediated differentiation of rat olfactory neurons counteracts apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 1999;6:227–233. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehlen P, Mehlen A, Godet J, Arrigo A-P. Hsp27 as a switch between differentiation and apoptosis in murine embryonic stem cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:31657–31665. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.50.31657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merck KB, Groenen PJ, Voorter CE, deHaard-Hoekman WA, Horwitz J, Bloemendal H, deJong WW. Structural and functional similarities of bovine α-crystallin and mouse small heat shock protein. A family of chaperones. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:1046–1052. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirkes PE, Little SA, Cornel L, Welsh MJ, Laney TN, Wright FH. Induction of heat shock protein 27 in rat embryos exposed to hyperthermia. Mol Reprod Dev. 1996;45:276–284. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(199611)45:3<276::AID-MRD3>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto RI, Tissieres A, and Georgopoulos C 1994 The Biology of Heat Shock Proteins and Molecular Chaperones. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Muchowski PJ, Bassuk JA, Lubsen NH, Clark JI. Human αB-crystallin. Small heat shock protein and molecular chaperone. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:2578–2582. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.4.2578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muchowski PJ, Clark JI. ATP-enhanced molecular chaperone functions of the small heat shock protein human αB crystallin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:1004–1009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohan NW, Heikkila JJ. Involvement of differential gene expression and mRNA stability in the developmental regulation of the Hsp30 gene family in heat shocked Xenopus laevis embryos. Dev. Genet. 1995;17:176–184. doi: 10.1002/dvg.1020170209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohan N, Tam Y, Fernando P, Heikkila JJ. Characterization of a novel group of basic small heat shock proteins in Xenopus laevis A6 kidney epithelial cells. Biochem Cell Biol. 1998;76:665–671. doi: 10.1139/bcb-76-4-665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohan N, Tam Y, Heikkila JJ. Heat-shock-induced assembly of Hsp30 family members into high molecular weight aggregates in Xenopus laevis cultured cells. Comp Physiol Biochem. 1998;119:381–389. doi: 10.1016/s0305-0491(97)00364-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smulders RH, Carver JA, Lindner RA, van Boekel MA, Bloemendal H, de Jong WW. Immobilization of the C-terminal extension of bovine αA-crystallin reduces chaperone-like activity. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:29060–29066. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.46.29060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringham EG, Dixon DK, Jones D, Candido EP. Temporal and spatial expression of patterns of the small heat shock (Hsp16) genes in transgenic Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol Biol Cell. 1992;3:221–233. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.2.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studier FW, Rosenberg AH, Dunn JJ, Dubendorf JW. Use of T7 RNA polymerase to direct expression of cloned genes. Meth Enzymol. 1990;185:60–89. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)85008-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takemoto L, Emmons T, Horwitz J. The C-terminal region of α-crystallin: involvement in protection against heat-induced denaturation. Biochem J. 1993;294:435–438. doi: 10.1042/bj2940435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam Y, Heikkila JJ. Identification of members of the Hsp30 small heat shock protein family and characterization of their developmental regulation in heat-shocked Xenopus laevis embryos. Dev Genet. 1995;17:331–339. doi: 10.1002/dvg.1020170406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanguay RM, Wu Y, Khandjian EW. Tissue-specific expression of heat shock proteins of the mouse in the absence of stress. Dev Genet. 1993;14:112–118. doi: 10.1002/dvg.1020140205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters E, Lee G, Vierling E. Evolution, structure and function of the small heat shock proteins in plants. J Exp Biol. 1996;47:325–338. [Google Scholar]

- Wistow G. Domain structure and evolution in alpha-crystallin and small heat shock proteins. FEBS Lett. 1985;181:1–6. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(85)81102-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]