WHY BE CONCERNED ABOUT HEALTH INEQUALITIES IF THE HEALTH OF THE POPULATION IS IMPROVING?

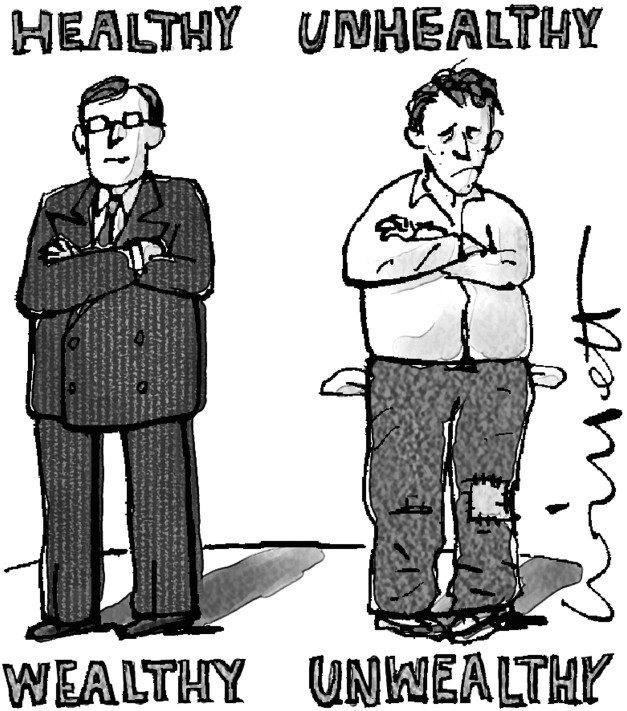

Statistics the world over show that good health is shared unevenly. Rates of disease and injury are strongly associated with social and economic factors such as income, education, and occupation. In many countries, the gap between the health of advantaged and disadvantaged groups is widening, even though measures such as average life expectancy indicate that the health of the population as a whole is improving.

The most powerful argument for reducing inequalities is on the grounds of justice. For many people, it is simply an affront to their sense of what is fair and proper that some people should have more than their share of avoidable illness. However, when challenged, most of us probably find it difficult to explain why such a situation should be unacceptable. There is no comprehensive account of justice that describes which health differences are unjust or that prescribes exactly the extent to which they should be reduced.

Someone holding a utilitarian philosophical position might be comfortable with an improvement in average health status (“the greatest good for the greatest number”) that does not necessarily narrow the differentials caused by socioeconomic status. But many people are unwilling to accept the “end justifies the means” implications of such a world view. A different philosophical position might view health as such an important asset (both as an end in itself and as an instrumental ingredient in achieving valued “doings and beings”) that gross inequalities in its distribution would be regarded as intrinsically problematic.1 In this light, poor health is one of the most important causes of restricted opportunity and limited personal freedom. It can be argued also that socioeconomic disparities in health status are unfair to the extent that they reflect underlying inequities in the distribution of “primary goods,” that is, the social determinants of health, including liberty, powers, opportunities, income and wealth, and the social bases of self-respect.2

Disparities in health are not a natural or inevitable consequence of society, nor are economic inequalities accidental: they result from decisions made by society on issues such as tax policy, home ownership, business regulation, welfare benefits, and health care funding.3 We suggest that inequalities become unfair when poor health is itself the consequence of an unjust distribution of the underlying social determinants of health (eg, unequal opportunities in education or employment).

Aside from the claims of justice, another compelling reason for reducing health disparities is that reducing them will benefit society at large by preventing “spillover” effects. This means that a reduction in health inequalities would benefit others in the population besides those with the worst health. One reason the sanitary reforms of the 19th century took place was that the affluent realized that the living conditions of the poor were a threat to their own good health. We see the same picture with modern epidemics such as acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, where disease emerges in conditions of poverty and disorder but is not confined to these populations. Self-interest does not apply only to control of infectious disease; alcohol abuse, mental illness, and violence also illustrate the general principle that everyone may be affected by the conditions of the weakest and most vulnerable members of their community.

Loss of the “social glue” that holds groups together may have many adverse consequences, including latent social conflict, diminished functioning of democracy, and reduced investment in social goods such as education and health care.4 When there are marked inequalities, those who are disadvantaged may lack the resources to participate in the social and economic mainstream of society. Apart from moral considerations, exclusion is costly. Exclusion is inefficient (since it represents a waste of potential talent) and unsafe (individuals who are out of the mainstream do not have a stake in the security of the wider community).

WHAT IS THE SCOPE OF HEALTH CARE INTERVENTIONS IN REDUCING DISPARITIES?

It is true that some health care interventions have caused a widening of health inequalities, but this is by no means inevitable. The distribution of effects depends on the nature of the intervention—structural and environmental interventions are likely to affect the population more evenly than educational programs aimed at individual behavior change (and also have greater potential to reduce health inequalities). For example, fluoridated water supplies are most beneficial for children with the highest rates of tooth decay, and consequently, the addition of fluoride to drinking water has reduced dental health inequalities.5 Similarly, tax changes to raise the price of cigarettes have lowered smoking rates most in the groups with the highest consumption.6 Health care interventions that are deliberately targeted to high-risk groups have also been shown to reduce inequalities.7

WHY SHOULD PHYSICIANS BE CONCERNED?

Physicians see the human face of inequalities every day in their offices. What stands behind the statistics are individual cases of avoidable death and disability. We seldom think of social disadvantage as a risk factor for disease in the same way that heavy alcohol consumption raises the risk of liver cirrhosis, or hypertension is associated with heart disease. But the effects of health inequalities are just as important to the health of patients as lifestyle factors such as drinking and smoking. Taking cardiovascular disease as an example, the population-attributable risk fraction (the proportion of disease that can be attributed to a risk factor) is similar for low socioeconomic status and for smoking. The role the medical profession takes in supporting tobacco control is widely accepted. Physicians also have an important role in implementing interventions and advocating for policies that abate socioeconomic disparities.

Figure 1.

Competing interests: None declared

References

- 1.Sen A. Inequality Re-examined. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1992.

- 2.Daniels N, Kennedy BP, Kawachi I. Why justice is good for our health: the social determinants of health inequalities. Daedalus 1999;128: 215-251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fischer CS, Hout M, Jankowski M, Lucas SR, Swidler A, Voss K. Inequality by Design. Cracking the Bell Curve Myth. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1996.

- 4.Kawachi I, Kennedy BP. Health and social cohesion: why care about income inequality? BMJ 1997;314: 1037-1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carmichael CL, Rugg-Gunn AJ, Ferrell RS. The relationship between fluoridation, social class and caries experience in 5-year-old children in Newcastle and Northumberland in 1987. Br Dent J 1989;167: 57-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Townsend J, Roderick P, Cooper. Cigarette smoking by socioeconomic group, sex and age: effects of price, income, and health publicity. BMJ 1994;309: 923-927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Victora CG, Vaughan JP, Barros FC, Silva AC, Tomasi E. Explaining trends in inequities: evidence from Brazilian child health studies. Lancet 2000;356: 1093-1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]