Abstract

Adenosine exerts a marked protective effect on the heart during cardiac ischemia. This protection is mediated by binding to the A1 and A3 subtypes of adenosine receptor (A1R and A3R, respectively). The objective of the present study was to investigate whether activation of A1 and A3 adenosine receptors may reduce doxorubicin-induced damage to cardiomyocytes in culture. Cultured cardiomyocytes from newborn rats were treated with 0.5–5 μm doxorubicin (DOX) for 18 h and then incubated in drug-free medium for an additional 24 h. This treatment resulted in cell damage and lactate dehydrogenase release, even after low (0.5 μm) doses of the drug, and increased in a concentration-dependent manner. Activation of A3-subtype but not A1-subtype receptors attenuated doxorubicin-cardiotoxicity after drug treatment for 18 h followed by 24 h incubation in drug-free medium. Modulation of intracellular calcium mediated by activation of A3R, but not by A1R, in cultured myocytes suggested an important pathophysiological significance of this subtype of adenosine receptors. Protection by A3R agonist Cl-IB-MECA (2-chloro-N6-(3-iodobenzyl)adenosine-5′-N-methyluronamide) following DOX treatment is evident in: (1) decreases in intracellular calcium overloading and abnormalities in Ca2+ transients; (2) reduction of free-radical generation and lipid peroxidation; (3) attenuation of mitochondrial damage by protection of the terminal link (COX-complex) of respiratory chain; (4) attenuation of the decrease in ATP production and irreversible cardiomyocyte damage. Cardioprotection caused by Cl-IB-MECA was antagonized considerably by the selective A3 adenosine receptor antagonist MRS1523.

Keywords: Doxorubicin, Adenosine receptors, Adriamycine, Cardioprotection, Image analysis, Lipid peroxidation, ATP, Calcium overloading

Introduction

Adenosine (ADO), the purine nucleoside, is a well-known regulator of a variety of physiological functions in the heart. In stress conditions like hypoxia or ischemia, the concentration of ADO in the extracellular space rises dramatically. This elevated amount of adenosine might protect the heart from hypoxic damage.1 Adenosine is a ubiquitous regulator of cellular function. Its effects are mediated by binding to four adenosine receptor (AR) subtypes termed A1, A2A, A2B and A3.2 Traditionally, the A1 ADO receptor (A1R) was thought to be the only subtype expressed in ventricular cardiomyocytes.

However, there is increasing evidence that other ADO receptor subtypes also exist in ventricular myocyte and they may have important physiological functions.3 The A3 ADO receptor (A3R) is the most recently identified subtype. Like A1R, it is negatively coupled to adenylyl cyclase. Tracey et al.4 were the first to demonstrate unambiguously that selective activation of A3 receptor provides cardioprotection from ischemia–reperfusion injury in the rabbit heart. A highly selective A1R agonist CCPA (2-chloro-N6-cyclopentyladenosine) and A3R agonist Cl-IB-MECA (2-chloro-N6-(3-iodobenzyl)adenosine-5′-N-methyluronamide) have been shown to protect against hypoxia.5 Blocking adenosine receptors with selective A1 and A3 receptor antagonists DPCPX (8-cyclopentyl-1-3-dipropylxanthine) for A1R and MRS1523 [5-propyl-2-ethyl-4-propyl-3-(ethylsulfanylcarbonyl)-6-phenylpyridine-5-carboxylate] for A3R abolished the protective effects of ADO. Adenosine has been shown to delay the onset of ischemic contracture,6 reduce the rates of ATP catabolism and intracellular H+ and Ca2+ accumulation during ischemia,6,7 and reduce infarct size.8 Activation of both adenosine A1 and A3 receptors resulted in a protective response greater than that induced by stimulation of either receptor alone.5 Recently, we have shown that A3 subtype of ADO receptors is expressed in cultured cardiac myocytes from newborn rats and activation by high doses (≥10 μm) of this receptor induce apoptosis while low doses (~100 nm) are cardioprotective.9–11

Doxorubicin (adriamycin) is an anthracycline antibiotic that has been shown to be effective in the treatment of acute leukemias and malignant lymphomas as well as in a number of solid tumors.12 The severe cardiotoxicity of doxorubicin (DOX) limits its clinical use.13 In spite of extensive investigations, the mechanism involved in cardiomyocyte toxicity of DOX is not yet completely understood. This mechanism is generally related to DOX interaction with nuclear14 and mitochondrial15 DNA. The cardioselective accumulation of DOX in nucleus and mitochondria is consistent with the implication of mitochondrial and cellular dysfunction in the cumulative and irreversible cardiotoxicity observed clinically in patients receiving DOX chemotherapy.15 The exact mechanisms underlying DOX-induced cardiac damage are certainly related to the ability of the drug to induce membrane destruction through lipid peroxidation,16 to generate free radicals17 and to change the intracellular calcium homeostasis.17–20 DOX and other anthracyclines may induce cardiac injury after being metabolized to the corresponding semiquinone free radical by broadly distributed enzymes, the flavin reductases.21 These free radicals, analogous to the reactive oxygen species generation during ischemia/reperfusion, may induce cardiomyocyte injury.

The aim of our study was to test the working hypothesis that stimulation of the A1R and A3R with the highly selective agonists CCPA and Cl-IB-MECA would reduce cardiomyocyte damage after treatment with DOX in culture. Protection from a damage as expressed by reduction in release of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) into the medium, modulation of myocyte Ca2+ homeostasis and preservation of ATP synthesis in cardiomyocytes after DOX treatment, were investigated. Moreover, the protection after DOX treatment at the terminal link (COX-complex) of the respiratory chain, inhibition of free radical generation and lipid peroxidation induced by DOX, were studied. Our findings show that Cl-IB-MECA reduces the damage induced by DOX by activating A3R.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

Hearts from newborn (2–3 days old) rats were removed under sterile conditions and washed three times in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove excess blood cells. The hearts were minced into small fragments and then agitated gently in a solution of proteolytic enzymes—RDB (Biological Institute, Ness-Ziona, Israel), prepared from a fig tree extract. The RDB was diluted 1:100 in Ca2+ and Mg2+-free PBS at 25°C and incubated with the heart fragments for several cycles of 10 min each, as described previously.22 Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing 10% horse serum (Biological Industries, Kibbutz Beit Haemek, Israel) was added to the supernatant containing a suspension of dissociated cells. The mixture was centrifuged at 300×g for 5 min. The supernatant phase was discarded and the cells were resuspended. The cell suspension was diluted to 1.0×106 cells/ml, and 1.5 ml of suspension was placed in 35 mm plastic culture dishes on collagen/gelatin-coated cover-glasses. The cultures were incubated in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2, 95% air at 37°C. The growth medium was replaced after 24 h and then every 3 days. Cells were treated on day 4 in culture with 0.5–5 μm of DOX for 18 h and then with drug-free growth medium for an additional 24 h.

Assessment of cytochrome C oxidase (COX) activity

COX activity was measured by a cytochemical method, based on the oxidative polymerization of 3,3-diaminobenzidine (DAB) to a coloured reaction product.23 COX content in whole cultured cardiomyocyte correlated with the optical density of cytochemically stained cells. Cultured cells were fixed with 0.5% formaldehyde solution in PBS for 5 min, washed in PBS and placed in an incubation medium containing: PBS with 1 mg/ml DAB, 1 mg/ml cytochrome C (type III, Sigma Chemical Co), and 85 mg/ml sucrose. The cells were incubated in the dark at 37°C for 1-1.5 h. They were then rinsed in distilled water, coverslipped with glycerol and analysed as described below.

Image analysis

Image analysis was performed with a Scan-Array 2 Image Analyzer (Galai, Israel). The analyser consisted of an Axiovert 135TV microscope (Zeiss, Germany) and a black and white Sony camera interfaced to an image analysis computer. The ratio of a specific phase (COX-positive) in the image to the total image area was compared as described elsewhere.22

LDH assay

Cytotoxicity was assessed by spectrophotometric measurement of LDH released into the culture medium. LDH activity was measured using a LDH kit (Sigma). LDH release was standardized as described.21 Control (100%) was defined as LDH released in samples from dishes in which cells were lysed with 1% Triton X-100.21

Intracellular Ca measurements

Intracellular free calcium concentration, [Ca2+]i, was estimated from indo-1 fluorescence using the ratio method described by Grynkiewicz et al.24 Cardiomyocytes were incubated with 2 μm indo-1/AM and 1.5 μm pluronic acid for 30 min in glucose enriched PBS at 24-25°C. After incubation, the cells were rinsed twice with glucose-enriched PBS and transferred to a chamber on the stage of Zeiss inverted epifluorescent microscope. Indo-1 was excited at 355 nm and the emitted light then split by a dichroic mirror to two photomultipliers (Hamamatsu, Japan) with input filters at 405 and 495 nm. The fluorescence ratio of 405/495 nm, which is proportional to [Ca2+]i, fed to a SAMPLE program written by Dr Dron Kaplan from Biological Institute, Nes-Ziona, Israel. The calibration and analysis were performed at 24-25°C. Under these conditions fluorescence ratio of indo-1 remained stable for 4-5 h. No compartmentation of indo-1 could be observed when 4–5 day old cultured cells were analysed. The ratio (R) of the light emitted at 405 nm to that emitted at 490 nm was translated to [Ca2+]i, with the equation [Ca2+]i=Kdβ(R-Rmin) (Rmax-R)−1. Kd—the apparent dissociated constant of indo-1. β—the ratio of 490 nm signals at very low and saturating calcium concentrations. Rmin and Rmax are the fluorescence ratio values at very low and saturating calcium concentrations, respectively, after autofluorescence subtraction at both wavelengths. Five μm ionomycin was used to yield maximal signal change in situ.

Lipid peroxidation assay

Lipid peroxidation was measured as the level of lipid hydroperoxides (LOOH), using a Lipid Hydroperoxide Assay Kit (Cayman Chemical Company, USA). This assay measures the hydroperoxides directly utilizing the redox reactions with ferrous ions, producing ferric ions. The resulting ferric ions are detected using thiocyanate ion as the chromogen. According to the manufacturer’s recommendation, quantitative extraction method was developed to extract lipid hydroperoxides into chloroform/methanol and the extract was directly used in the assay. This procedure eliminates any interference caused by endogenous hydrogen peroxide or ferric ions in the sample, and provides a sensitive and reliable assay for lipid peroxidation. The standards and samples were transferred into a 96-well plate and values were read with a Spectrafluor Plus (Tecan) plate-reader.

Measurement of ATP concentration

Control cells and DOX-treated cardiomyocytes were harvested in 1 ml cold 5% trichloroacetic acid. The cell extract was used to measure ATP content by the luciferin-luciferase bioluminescence kit (ATP Bioluminescence Assay Kit CLSII, Boehringer Mannheim) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The values are expressed as nanomoles/mg of protein.

Protein determination

Protein content was determined according to the method of Bradford.25

Chemicals

The highly selective A3R agonist, Cl-IB-MECA, was a gift from the National Institute of Mental Health Chemical Synthesis and Drug Supply Program. The selective A3R antagonist MRS1523 was synthesized as described by Li et al.26 A highly selective A1R agonist CCPA was purchased from RBI (Sigma). Indo-1/AM was obtained from Teflabs (Texas Fluorescence Lab., USA) and other reagents were purchased from Sigma Chemicals. The selectivity of Cl-IB-MECA, CCPA and MRS1523 in the rat relative to the concentrations used in this study was shown recently.11,26–28

Statistics

Results are expressed as the mean± s.e.m. Data were analysed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) with application of a post-hoc Tukey’s test. P<0.05 was accepted as indicating statistical significance.

Results

Effect of DOX on LDH release

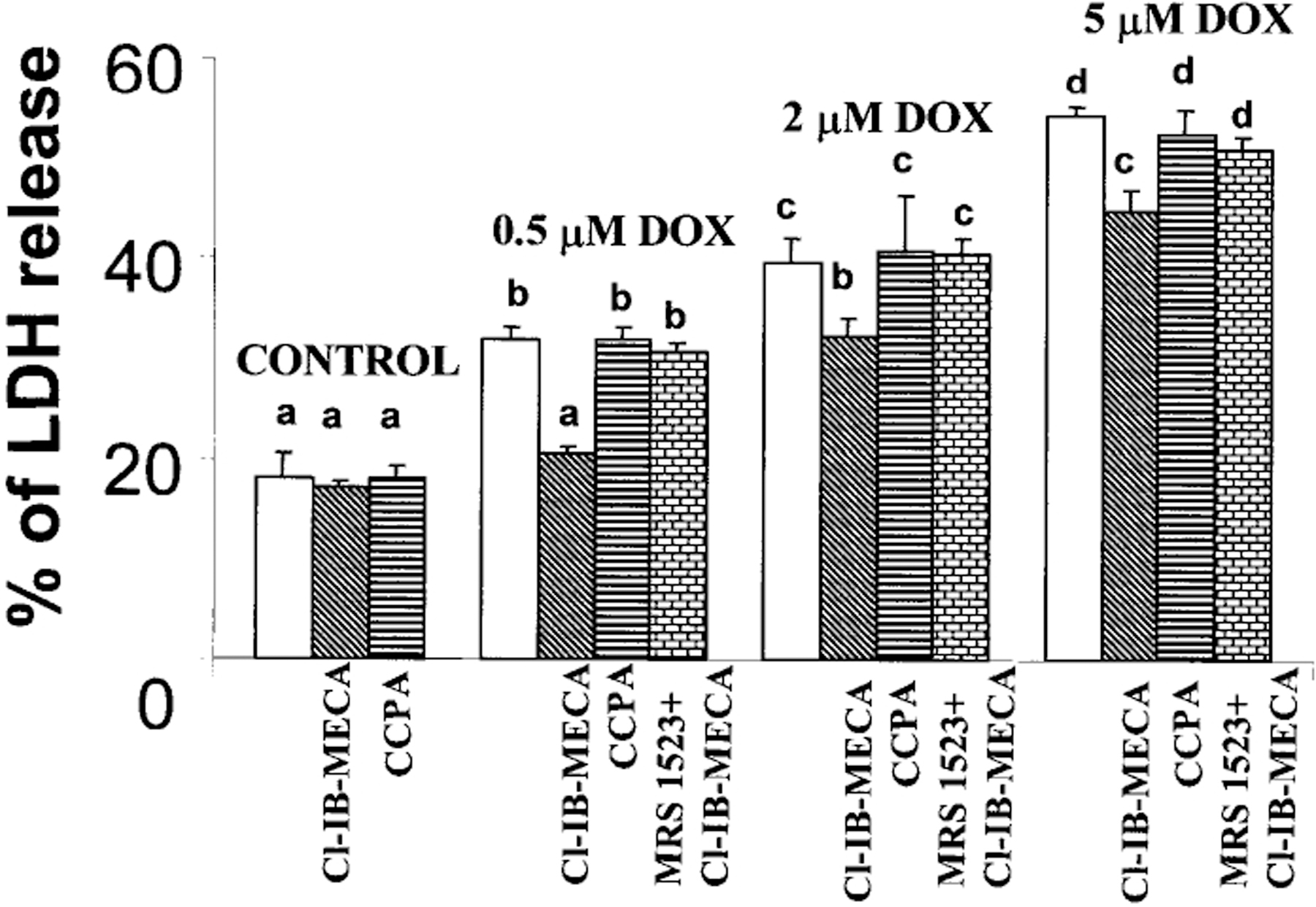

The release of LDH into the medium was measured as a marker of cell injury after DOX treatment. The release of LDH, after an 18 h exposure of the cells to DOX followed by 24 h in a drug-free medium, increased in a dose-dependent manner and was evident even after treatment with as little as 0.5 μm DOX (Fig. 1). The addition of A3R agonist Cl-IB-MECA (100 nm) to the DOX-treated cells significantly decreased the amount of LDH released (Fig. 1), indicating that activation of A3 receptors mediates a sustained cardioprotective effect. The protection achieved by the A3R agonist Cl-IB-MECA was abolished by the A3R antagonist, MRS1523 (1 μm). The A1 receptor agonist CCPA (100 nm) was not effective in protection against DOX toxicity (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Effects of activation of A1R and A3R on DOX-induced LDH release. Four days old cardiomyocyte cultures were exposed to DOX for 18 h, then incubated for 24 h in drug-free medium. A1R agonist CCPA (100 nm) or A3R agonist Cl-IB-MECA (100 nm) were introduced to the medium 10 min before DOX administration and left in culture during DOX treatment. A3R selective antagonist MRS1523 (1 μm) was added to medium 10 min before Cl-IB-MECA application. The significance of observed differences was determined by ANOVA. Means with the same letter are not significantly different (n=6, P<0.05) according to a post-hoc Tukeys test.

Calcium transients

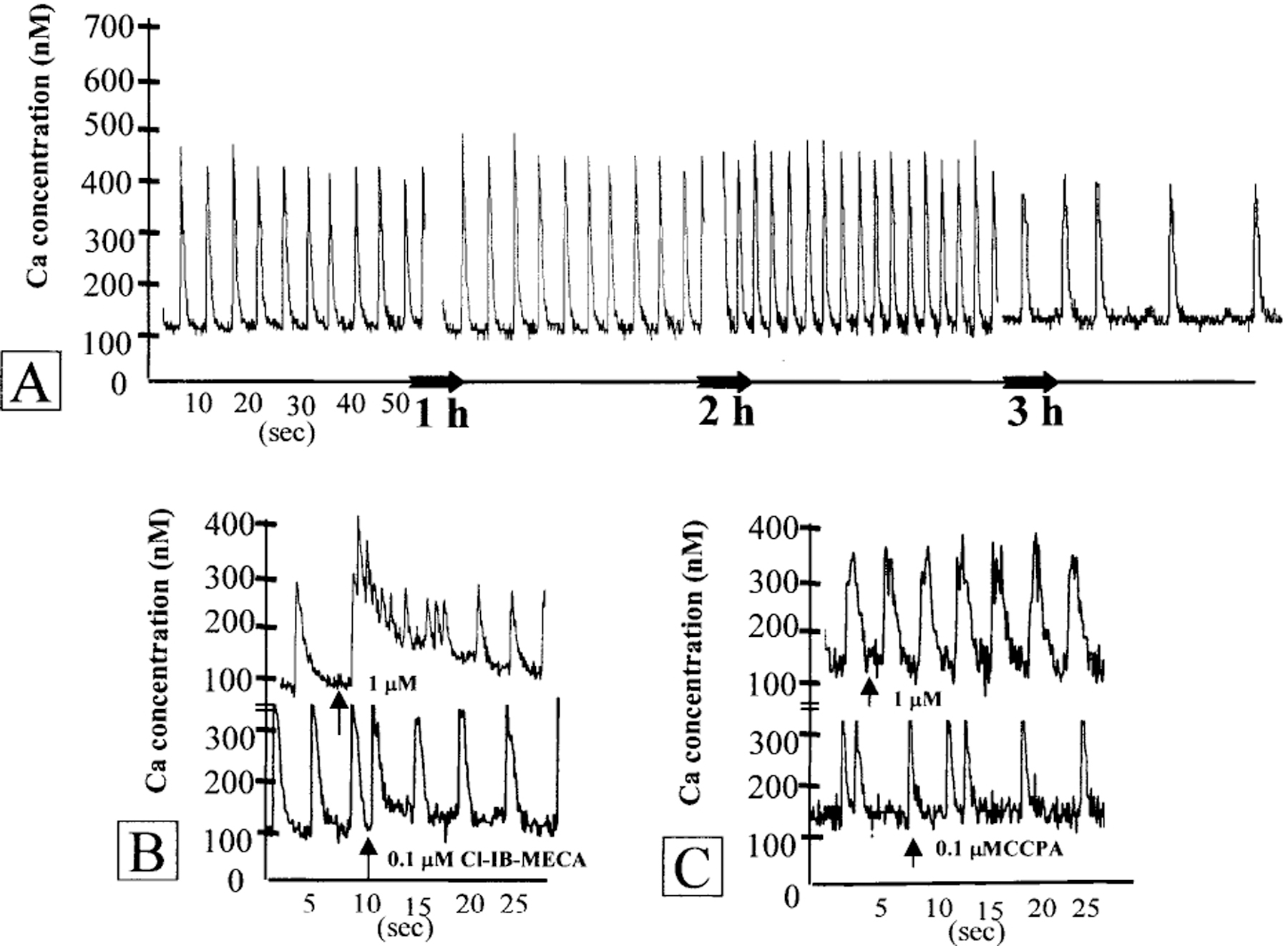

In indo-1 loaded cells, each beat was accompanied by an increase in 405 nm and a decrease in 495 nm wavelength fluorescence intensity signal. The ratio of indo-1 fluorescence at the above wavelengths was converted into [Ca2+]i concentration. Control myocytes demonstrated spontaneous, regular beating activity and [Ca2+]i transients [Fig. 2(A)]. A3 adenosine receptor agonist Cl-IB-MECA caused an increase in [Ca2+]i in a concentration-dependent manner. One hundred nm of the drug abbreviated the complete decay of the preceding [Ca2+]i transient and elevated the minimal level of [Ca2+]i. The maximal level of [Ca2+]i was not elevated. After 2–3 beats, the minimal level returned to control value. One μm of the agonist produced a rapid rise in minimal and maximal level of calcium and in the rate of [Ca2+]i transients. The increase in Ca2+ lasted for 10–20 s and finally returned to control level [Fig. 2(B)]. Activation of adenosine A1 receptor did not result in enhanced influx of Ca2+ [Fig. 2(C)]. Earlier it was shown that the increase in [Ca2+]i achieved by the A3R agonist Cl-IB-MECA (30 μm) was inhibited effectively by the A3R antagonist, MRS1523 (1 μm).9 Progressive elevation of the intracellular calcium and an increase of the minimal level of [Ca2+]i transients were observed in cardiomyocytes treated with DOX. The slow elevation of [Ca2+]i was accompanied by increase in beat rate and abnormality in oscillations [Fig. 2(D)]. The elevation of calcium transients and abnormality in beating rate were significantly reduced in cardiomyocytes preincubated with 100 nm Cl-IB-MECA [Fig. 2(E)]. A3R antagonist, MRS1523 (1 μm) abolished the protection of Ca level and transients achieved by A3R agonist Cl-IB-MECA [Fig. 2(F)]. The A1 receptor agonist CCPA (100 nm) was not effective in protection against calcium overloading after DOX treatment [Fig. 2(G)].

Figure 2.

Effect of adenosine A1R and A3R activation on intracellular Ca2+ concentration in cultured cardiomyocytes treated with DOX. (A) Stability of intracellular calcium level and [Ca2+]i transients in control cardiomyocytes. (B) Effects of A3R agonist Cl-IB-MECA (0.1–1 μm) on intracellular calcium levels in cultured cardiomyocytes. (C) Effects of A1R agonist CCPA (0.1–1 μm) on intracellular calcium level. (D) Progressive slow elevation of the intracellular calcium and abnormality in oscillations after DOX (5 μm) treatment. (E) Attenuation of Ca2+ elevation after DOX (5 μm) treatment by Cl-IB-MECA (100 nm). (F) Prevention of protective effect of Cl-IB-MECA by A3R antagonist MRS1523 (1 μm). Ligands were added to the medium before treatment with DOX and left during the treatment. (G) The A1R agonist CCPA (100 nm) was not effective in prevention of intracellular calcium elevation in cardiac cells after DOX (5 μm) treatment. Drugs were added at the indicated time (arrows).

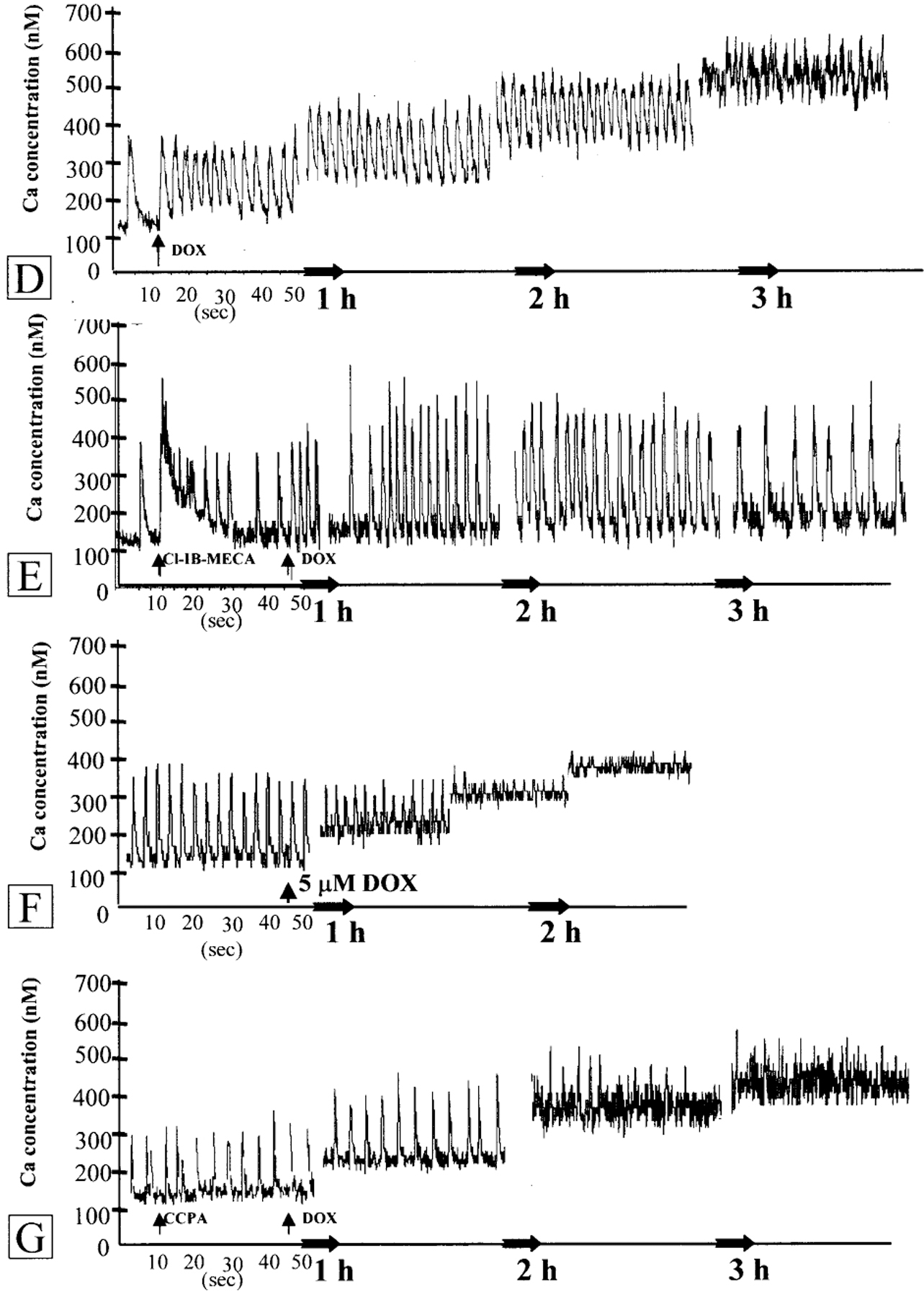

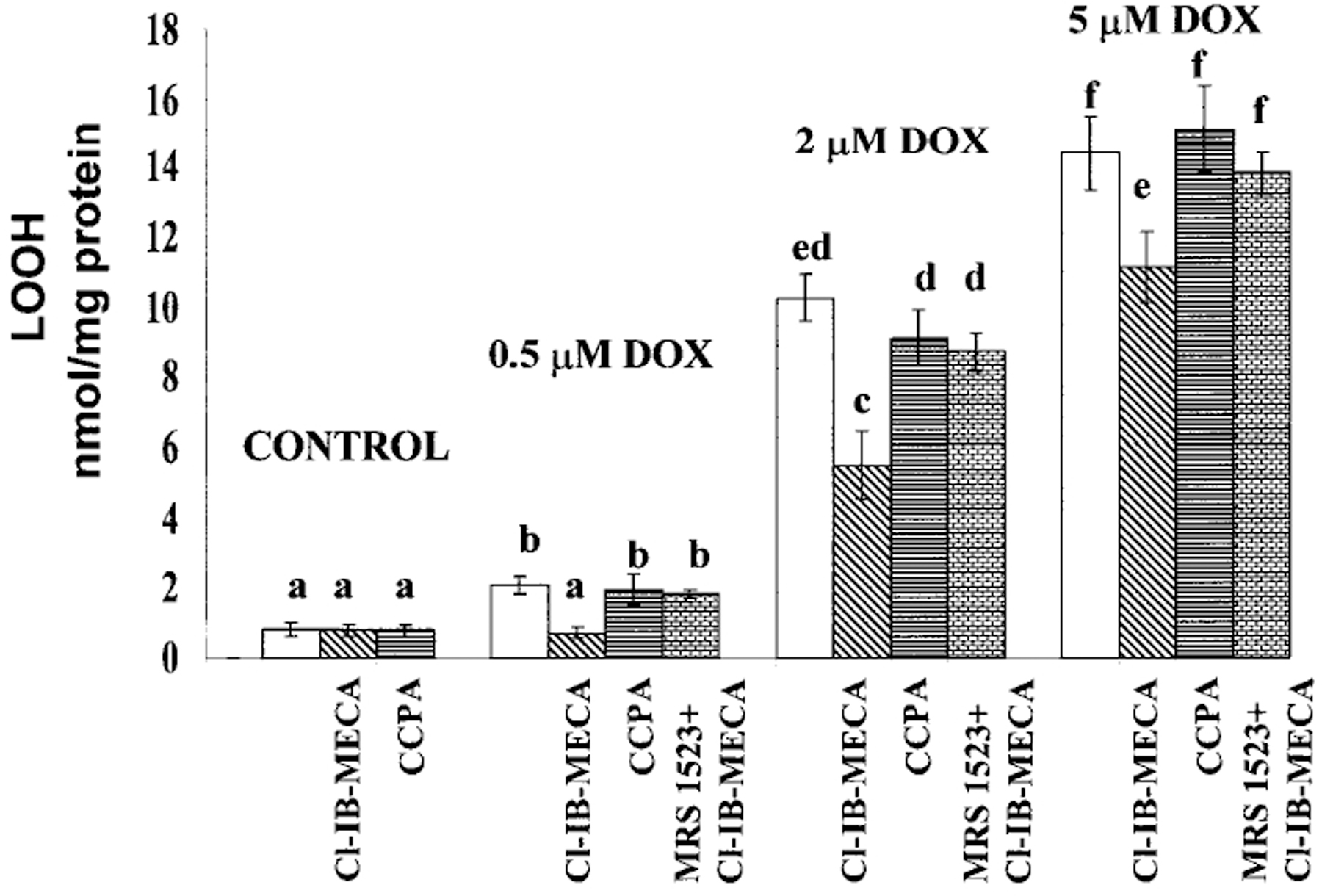

Activation of lipid peroxidation by DOX

The level of lipid hydroperoxides, LOOH, is a sensitive marker of lipid peroxidation in the cell. To test the basal level of lipid peroxidation in cultured cardiomyocytes after DOX treatment, LOOH was estimated after an 18 h exposure of the cells to 0.5–5 μm DOX followed by 24 h in drug-free medium. LOOH production in controls and DOX-treated cells is shown in Figure 3. Control cardiomyocytes produced 0.8±0.23 LOOH nmol/mg protein. Treatment with 0.5 μm DOX induced an approximately 2.5-fold increase in hydroperoxide production: following 2 μm and 5 μm DOX exposure, a 15-fold and 21-fold increase was obtained, respectively. Addition of 100 nm Cl-IB-MECA or CCPA to control cells did not change LOOH values (Fig. 3). Addition of 100 nm Cl-IB-MECA to cells treated with 0.5 μm DOX reduced LOOH value to control level and significantly reduced lipid peroxidation after treatment with 2 and 5 μm DOX (Fig. 3). This beneficial effect of Cl-IB-MECA was blocked by 1 μm of the A3R antagonist MRS1523 (Fig. 3). Addition of 100 nm CCPA, a selective A1R agonist, did not decrease the level of lipid peroxidation induced by DOX (Fig. 3). Thus, only A3R activation was effective in attenuation lipid peroxidation after DOX treatment of cultured cardiomyocyte.

Figure 3.

Effects of activation of A1R and A3R on DOX-induced intensification of lipid peroxidation. Four days old cardiomyocytes in vitro were exposed to DOX for 18 h, then left for 24 h in drug-free medium. The level of lipid hydroperoxide (LOOH) was estimated after exposure to 0.5–5 μm DOX. The A1R agonist CCPA (100 nm), A3R agonist Cl-IB-MECA (100 nm) and A3R antagonist MRS1523 (1 μm) were added to the medium before treatment with DOX and left during the treatment. Significance of the differences observed was determined by ANOVA. Means with the same letter are not significantly different (n=6, P<0.05) according to a post-hoc Tukey’s test.

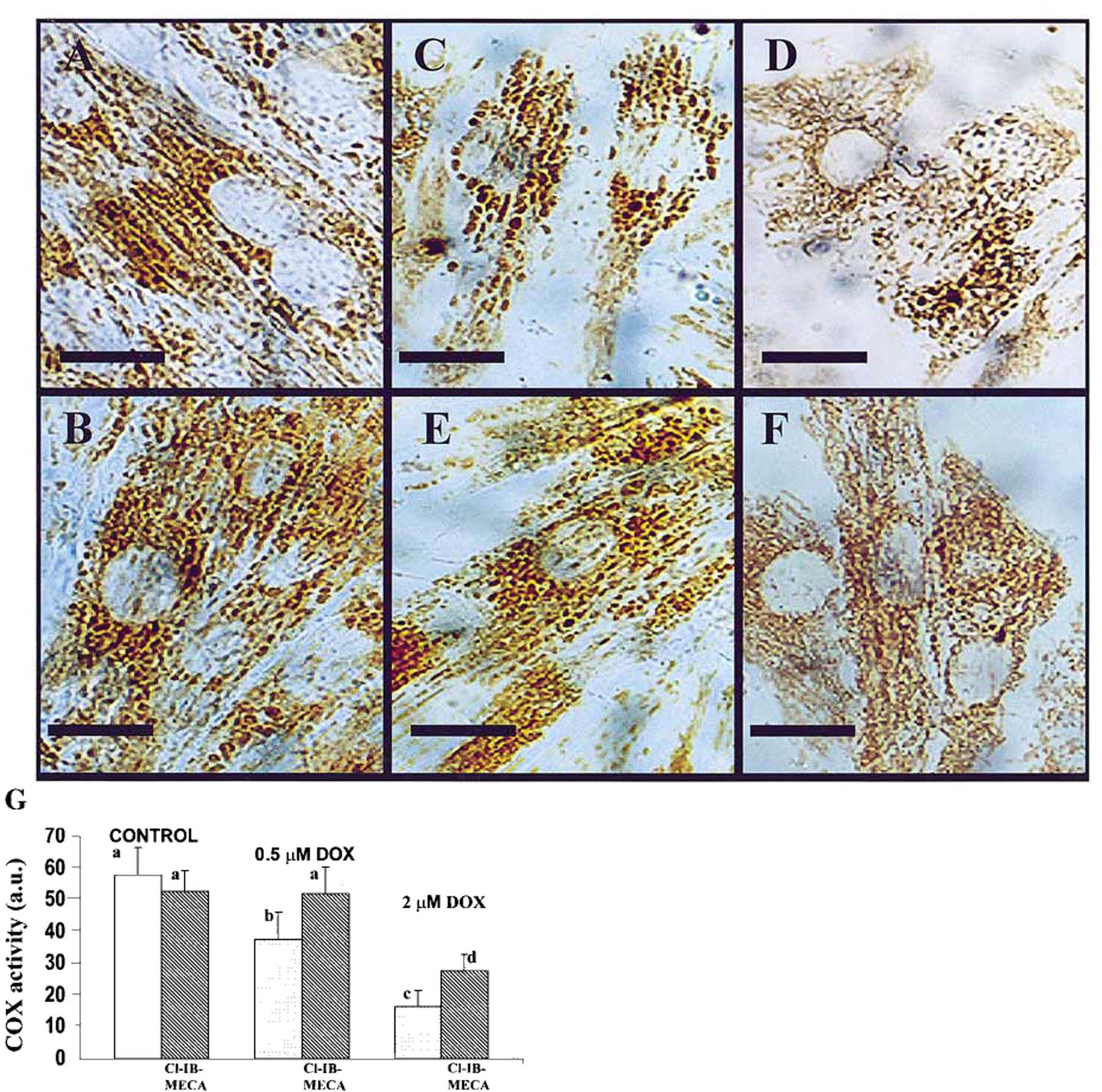

Mitochondrial cytochrome C oxidase

To elucidate the biological significance of the interaction of DOX with the pivotal mitochondrial enzyme cytochrome C oxidase and the protective activity of adenosine A3 receptors, we determined COX activity by histochemistry. In control cardiomyocytes, COX-positive mitochondrial patterns were revealed in the perinuclear and intermyofibrillar regions, forming parallel longitudinal rows and, in many cells, localization of the mitochondria followed by the striation pattern of the myofibrils [Fig. 4(A)]. After 18 h exposure of the cells to 0.5 μm DOX followed by 24 h in a drug-free medium, a decrease in the number of COX-positive mitochondria were evident [Fig. 4(C)]. The longitudinal, striated pattern disappeared, and prominent conglomerates of rounded mitochondrial patterns were revealed in the perinuclear space. At a higher dose (2 μm), DOX caused a further decrease in the amount of mitochondria/cardiomyocyte. Localization of mitochondria was similar to that observed following a low dose of DOX; however, the mitochondrial patterns were small to dust-looking [Fig. 4(D)]. Addition of 100 nm Cl-IB-MECA to control cultures did not modify COX distribution in cultured cardiomyocytes [Fig. 4(B)]. Addition of Cl-IB-MECA to cultures treated with 0.5 μm DOX completely reduced DOX-induced inhibition of COX activity [Fig. 4(E)] and partially reduced inhibition of COX in cultures treated with 2 μm DOX [Fig. 4(F)]. Addition of 1 μm of the A3R antagonist MRS1523 blocked the protective activity of Cl-IB-MECA (data not shown). Morphological data were quantitatively confirmed by definition of the ratio of COX-positive area in the image to the total image area [Fig. 4(G)].

Figure 4.

Light microscopic observation of cytochrome C oxidase (COX) activity in cultured cardiomyocytes. Effects of activation of A3R on DOX-induced alterations in COX activity. Four days old cardiomyocytes in vitro were exposed to DOX for 18 h, then incubated for 24 h in drug-free medium. A3R agonist Cl-IB-MECA (100 nm) was added to medium before treatment with DOX. (A) Control cells. Dark COX-positive mitochondria revealed in the perinuclear and intermyofibrillar regions. (B) Cells treated with Cl-IB-MECA (100 nm). (C) Decrease in COX activity after 0.5 μm DOX treatment. (D) Considerable decrease in COX activity in cells treated with 2 µm DOX. (E) Protection of COX activity in cells treated with 0.5 μm DOX by activation of A3R with Cl-IB-MECA. (F) Moderate protection of COX activity in cells treated with 2 μm DOX by activation of A3R with Cl-IB-MECA (bars=10 μm). (G) Definition of the ratio of COX-positive area in the image of stained cells to the total image area. The significance of observed differences was determined by ANOVA. Means with the same letter are not significantly different (n=6, P<0.05) according to a post-hoc Tukey’s test.

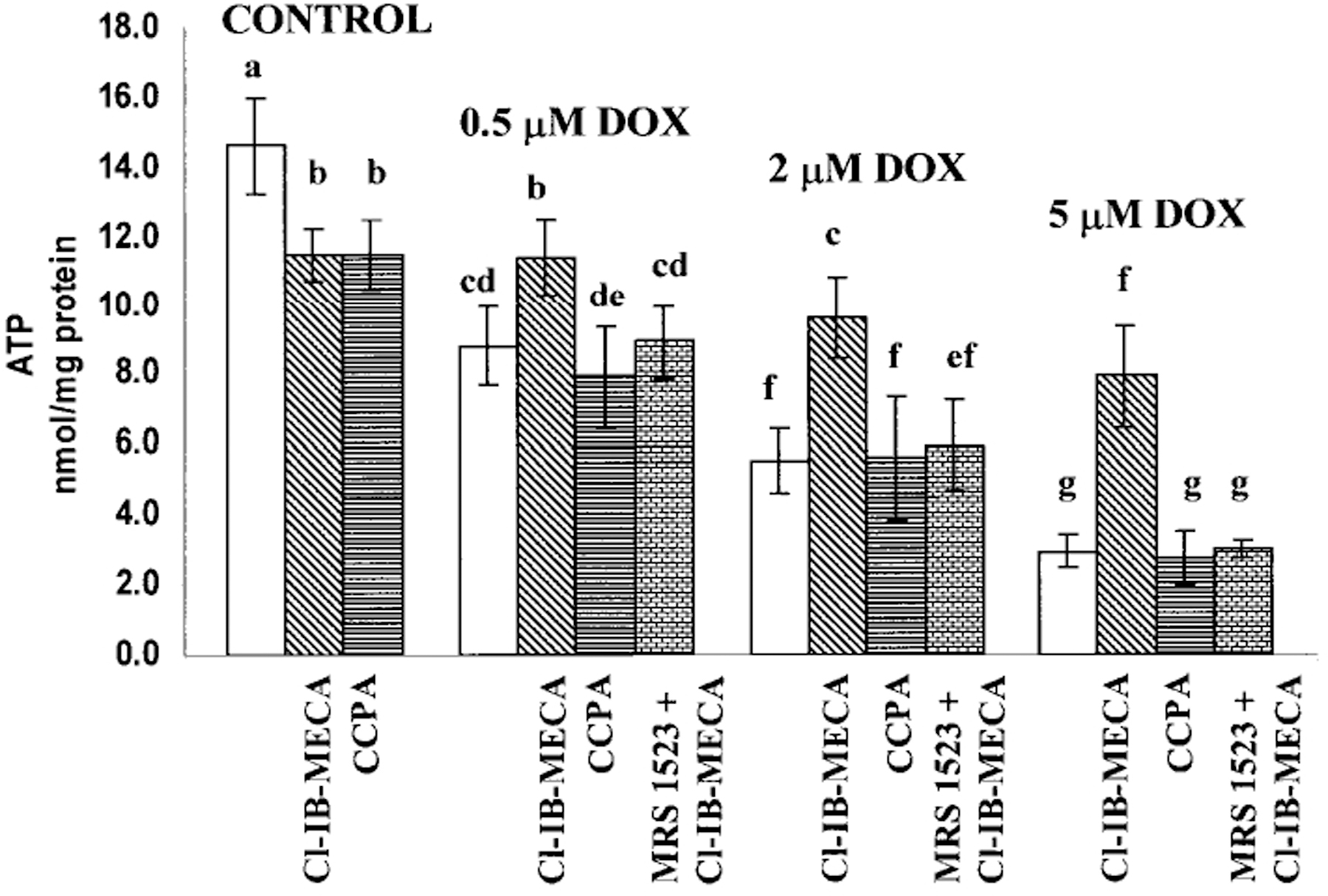

Cellular ATP content

Myocyte cultures were treated with 0.5–5 μm DOX for 18 h on day 4 of culture, then incubated in DOX-free medium for 24 h and studied morphologically.10 After treatment with 0.5 μm DOX, an irregular intermyofibrillar network with marked accentuation in the perinuclear region of cardiac cells was observed. In the majority of the myocytes, perinuclear edema and cytoplasmic vacuoles were evident. All cultures treated with 2 μm DOX exhibited microscopic features of dying cells, including nuclear pyknosis and kariorrhexis in many cells. At a dose of 5 μm DOX, pronounced oncotic damages were found, and it caused irreversible changes in the nucleus of some cells (necrosis). Under the experimental conditions and drug concentrations used, total ATP content was measured. The result shows that ATP levels fell significantly after exposure to 0.5, 2 and 5 μm DOX (Fig. 5). Pretreatment of cardiomyocytes with 100 nm of A1R agonist CCPA did not protect against ATP depletion by DOX. However, pretreatment with 100 nm A3R agonist Cl-IB-MECA prevented the decrease of ATP level in cultures treated with 0.5 and 2 μm DOX (Fig. 5). The protection of ATP level achieved by the A3R agonist Cl-IB-MECA was abolished by the A3R antagonist, MRS1523 (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Effects of the activation of A1R and A3R on the ATP level in cultured cardiomyocytes after DOX treatment. Four days old cardiomyocytes in vitro were exposed to DOX for 18 h, then left for 24 h in drug-free medium. A1R agonist CCPA (100 nm) and A3R agonist Cl-IB-MECA (100 nm) were added to the medium 10 min before DOX administration and left in the culture during DOX treatment. A3R selective antagonist MRS1523 was added to the media 10 min before Cl-IB-MECA application. The significance of observed differences was determined by ANOVA. Means with the same letter are not significantly different (n=6, P<0.05) according to a post-hoc Tukey’s test.

Discussion

It has been shown that ADO at high concentrations (1 mm) can significantly decrease toxicity induced by the antineoplastic drug, doxorubicin (DOX), in heart myocyte culture.29 In DOX-treated cells, the addition of ADO increased both the ATP concentration and the adenylate charge, and concomitant with this increase, the number of beating cells and rate of contractions are maintained. It was shown that in primary cultures of rat myocardial cells, pre-incubation with adenosine for 24 h prior to the addition of DOX decreases or prevents drug-induced release of creatine phosphokinase and LDH.30 These data were suggested as a result of synthesis of ATP from exogenous adenosine in DOX-treated cultured cells. Now it is evident that ADO is released from cardiomyocyte and mediates important protective functions by ADO receptors. Moreover, high concentrations of ADO are toxic for cardiac22 and other cells.31,32 DOX and other anthracyclines may induce cardiac injury after being metabolized to the corresponding semiquinone-free radical by broadly distributed enzymes, the flavin reductases.21 These free radicals, analogous to the reactive oxygen species generated during ischemia/reperfusion, may cause injury through oxidative damage of cardiomyocytes.21 However, unlike hypoxic injury, which develops during 1–2 h,11 in our study, cardiomyocyte dysfunction caused by low doses of DOX develops slowly; these slower kinetics may explain the specific effect of only the more sustained subtype of ADO receptors.

Calcium overloading was perhaps the first attempt to explain DOX cardiotoxicity.33 However, later it was found that DOX-induced dysfunction is associated with deficiency of calcium in myofibrillar apparatus.17 The complex nature of the modulation of myocardial Ca2+ handling is now recognized.18 DOX has been shown to induce spontaneous leakage of Ca2+ from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR),20 leading to a depletion of Ca2+ for contraction. DOX has been shown to inhibit sarcolemmal Na+/Ca2+ exchange,34 and the Na+/K+ pump, which would lead to intracellular Ca2+ overload of cardiomyocytes. As shown in this study, the A3R agonist Cl-IB-MECA significantly protected DOX-treated cells from Ca2+ overload. Recently, we have shown that high concentration of Cl-IB-MECA (20–30 μm) caused a sustained and reversible increase in [Ca2+]i, which was blocked by selective antagonist MRS1523.9 A2A-selective agonists CGS-21680 and A1R agonist CCPA were not effective.9 In a rat RBL-2H3 mast cell line, it was found that adenosine analogues interact with A3R to cause elevation of intracellular calcium via generation of inositol phosphate (IP3) through phosphoinositide breakdown.35 Thus, these findings suggest that A3R may initiate regulation of myocardial Ca2+ handling in adaptation to extreme situations including DOX toxicity.

The quinone structure permits DOX and other anthracyclines to act as electron acceptors in reactions mediated by oxoreductive enzymes.36 The addition of the free electron converts the quinones to semiquenone free radicals,37 which may induce free-radical injury to DNA or lipid peroxidation. Cardiomyocytes are characterized by less catalase, glutatione peroxidase and superoxide dismutase (SOD) than other cells, possibly explaining the selective toxicity of DOX for these cells.17 It was shown that cell-permeable SOD and glutatione peroxidase mimetics afforded protection against DOX-induced cardiotoxicity.38,39 These experiments support the hypothesis that intracellular detoxification of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide will inhibit DOX-induced injury to cardiomyocytes. Although many observations appear inconsistent with the free radical hypothesis of DOX cardiotoxicity, several studies17,36 concluded that there is insufficient evidence to implicate lipid peroxidation (through free-radical production at the level of cell membrane) in the antitumor effects of the antracyclines. Our data on cultured cardiomyocytes support the role of lipid peroxidation in cardiac cell damage. Simultaneously following subclinically relevant concentrations of DOX, it has been demonstrated that stimulation of adenosine A3R inhibits lipid peroxidation in the cultured cardiomyocytes after DOX treatment. Activation of a unique A3R in some cells, including rat cardiac myocytes, decreases the degree of lipid peroxidation and increases the activity of SOD, catalase, glutathione peroxidase and glutathione reductase.40,41 These data provide strong evidence that the cytoprotective action of A3 adenosine receptors is mediated, at least in part, via a novel mechanism-activation of the cellular antioxidant enzymes.

Structural and functional impairment of mitochondria in DOX-induced cardiomyopathy is one of the proposed mechanisms of the drug action.17,42,43 Cardiomyocytes undergo extensive mitochondrial damage leading to the depletion of energy sources, hypoxia and cell death. It was found that DOX interacts both with substrate (cytochrome C) and the enzyme (COX).42,43 These interactions may facilitate electron transfer. COX is a novel target enzyme involved in DOX-induced cardiovascular toxicity at relatively high DOX concentrations. It is also possible that DOX impairs the biosynthesis of COX at the level of transcription of mitochondrial and nuclear genes coding for COX subunits.42 As was shown in this study, loss of mitochondrial function was observed after treatment with relatively low concentrations of DOX. Treatment with 0.5 μm DOX, followed by 24 h reperfusion with drug-free medium, results in disintegration of mitochondria structure and arrangement, and decrease in total COX activity. Increase in LDH release indicates irreversible damage of some cardiomyocytes. The maximal damage of COX activity and distribution was observed after a maximal dose of 5 μm DOX. An alteration in mitochondrial physiology after DOX treatment may be responsible for disruption in ATP exchange, cell damage and cell death. The use of ATP as an index of cardiotoxicity is confirmed by the observation that some effects of DOX may be directly targeted to this biochemical system.44 Inhibition of oxidative phosphorylation, a decrease in high-energy phosphates and increased lactic acid production were previously observed in early DOX-cardiotoxicity investigations.17 The molecular mechanisms that lead to reduced levels of ATP after DOX treatment are unclear. It was reported that, following exposure to DOX, there were rapidly reduced levels of mRNA for key enzymes responsible for energy production.45

Adenosine is beneficial to myocardial preservation; however, its undesirable effects produced by A1 (bradycardia) and A2A-mediated actions (vasodilatation, hypotension) have impeded the routine clinical use of corresponding agonists. A3R stimulation could potentially provide myocardial protection without systemic side effects.46 Although A3R shares similarity with the other adenosine receptors, we demonstrate here functional differences from the adenosine A1 receptor. It was previously shown in a cultured chicken myocyte model that protection during cardiac ischemia mediated by prior activation of A3R exhibits a significantly longer duration than that produced by activation of A1R.47 Recently, it was shown in our model of cultured myocyte that DOX-mediated injury is a delayed response to the drug treatment.10 Using cytochemical and morphological methods, it was shown that myocyte damage after DOX treatment appears to occur only after a long incubation time in drug-free medium. These delayed effects may involve progressive uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation in mitochondria or accumulation of oxygen-free radical damage by a slow cyclical bioreduction of DOX in vitro.44 Activation and regulation of intracellular calcium mediated by activation of A3R in cultured myocytes and not by A1R suggest important pathophysiological significance of this subtype of adenosine receptors.

In summary, the current results show that the A3R-subtype and not the A1R-subtype mediates the attenuation of DOX cardiotoxicity after treatment for 18 h with the drug followed by 24 h incubation in drug-free medium. This adenosine receptor subtype mediates a decrease in both intracellular calcium overloading and abnormalities in Ca2+ transients. Activation of A3R leads to reduction of free-radical generation and lipid peroxidation after treatment with DOX, attenuates mitochondrial damage and inhibition of ATP production, and prevents irreversible cardiomyocyte damage. Further studies in this field are required in order to establish the relevance of A3R stimulation in treatment of cancer patients with both DOX and A3R agonist.

Acknowledgments

The skilful technical assistance of Mrs A. Isaac is gratefully acknowledged. This study was supported in part by Grant no. 4390 from the Chief Scientist’s Office of the Ministry of Health, Israel.

Abbreviation

- ADO

Adenosine

- AR

adenosine receptor

- A1R

A1 ADO receptor

- A3R

A3 ADO receptor

- CCPA

2-chloro-N6-cyclopentyladenosine

- Cl-IB-MECA

(2-chloro-N6-(3-iodobenzyl)adenosine-5′-N-methyluronamide)

- COX

cytochrome C oxidase

- DAB

3,3-diaminobenzidine

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

- DOX

doxorubicin

- LDH

lactate dehydrogenase

- LOOH

lipid hydroperoxides

- MRS1523

[5-propyl-2-ethyl-4-propyl-3-(ethylsulfanylcarbonyl)-6-phenylpyridine-5-carboxylate]

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

References

- 1.Mubagwa K, Mullane K, Flameng W. Role of adenosine in the heart circulation. Cardiovasc Res 1996; 32: 797–813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ralevic V, Burnstock G. Receptors for purines and pyrimidines. Pharmacol Rev 1998; 50: 413–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Auchampach JA, Bolli R. Adenosine receptor subtypes in the heart: therapeutic opportunities and challenges. Am J Physiol 1999; 276: H1113–H1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tracey WR, Magee W, Masamune H, Kennedy SP, Knight DR, Buchholz RA, Hill RJ. Selective adenosine A3 receptor stimulation reduces ischemic myocardial injury in the rabbit heart. Cardiovasc Res 1997; 33: 410–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parsons M, Young L, Lee JE, Jacobson KA, Liang BT. Distinct cardioprotective effects of adenosine mediated by differential coupling of receptor subtypes to phospholipases C and D. FASEB J 2000; 14: 1423–1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lasley RD, Rhee JW, Van Wylen DG, Mentzer RM Jr. Adenosine A1 receptor mediated protection of the globally ischemic isolated rat heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol 1990; 22: 39–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lasley RD, Mentzer RM Jr. Adenosine improves recovery of postischemic myocardial function via an adenosine A1 receptor mechanism. Am J Physiol 1992; 263: H1460–H1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Toombs CF, McGee S, Johnston WE, Vinten-Johansen J. Myocardial protective effects of adenosine. Infarct size reduction with pretreatment and continued receptor stimulation during ischemia. Circulation 1992; 86: 986–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shneyvays V, Jacobson KA, Li AH, Nawrath H, Zinman T, Isaac A, Shainberg A. Induction of apoptosis in rat cardiocytes by A3 adenosine receptor activation and its suppression by isoproterenol. Exp Cell Res 2000; 257: 111–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shneyvays V, Safran N, Halili-Rutman I, Shainberg A. Insights into adenosine A1 and A3 receptors function: cardiotoxicity and cardioprotection. Drug Dev Res 2000; 50: 324–337. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Safran N, Shneyvays V, Balas N, Jacobson KA, Shainberg A. Cardioprotective effects of adenosine A1 and A3 receptor activation during hypoxia in isolated rat cardiac myocytes. Mol Cell Biochem 2001; 217: 143–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murphy GP, Lawrence WJ, Lenhard REE. American Society Textbook of Oncology, 2nd Edition. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society. 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ettinghausen SE, Bonow RO, Palmeri ST, Seipp CA, Steinberg SM, White DE, Rosenberg SA. Prospective study of cardiomyopathy induced by adjuvant doxorubicin therapy in patients with soft-tissue sarcomas. Arch Surg 1986; 121: 1445–1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Skladanowski A, Konopa J. Relevance of interstrand DNA crosslinking induced by anthracyclines for their biological activity. Biochem Pharmacol 1994; 47: 2279–2287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Serrano J, Palmeira CM, Kuehl DW, Wallace KB. Cardioselective and cumulative oxidation of mitochondrial DNA following subchronic doxorubicin administration. Biochim Biophys Acta 1999; 1411: 201–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Myers CE, McGuire WP, Liss RH, Ifrim I, Grotzinger K, Young RC. Adriamycin: the role of lipid peroxidation in cardiac toxicity and tumor response. Science 1977; 197: 165–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olson RD, Mushlin PS. Doxorubicin cardiotoxicity: analysis of prevailing hypotheses. FASEB J 1990; 4: 3076–3086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsushita T, Okamoto M, Toyama J, Kodama I, Ito S, Fukutomi T, Suzuki S, Itoh M. Adriamycin causes dual inotropic effects through complex modulation of myocardial Ca2+handling. Jpn Circ J 2000; 64: 65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maeda A, Honda M, Kuramochi T, Takabatake T. A calcium antagonist protects against doxorubicin-induced impairment of calcium handling in neonatal rat cardiac myocytes. Jpn Circ J 1999; 63: 123–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halili-Rutman I, Hershko C, Link G, Rutman AJ, Shainberg A. Inhibition of calcium accumulation by the sarcoplasmic reticulum: a putative mechanism for the cardiotoxicity of adriamycin. Biochem Pharmacol 1997; 54: 211–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adderley SR, Fitzgerald DJ. Oxidative damage of cardiomyocytes is limited by extracellular regulated kinases 1/2-mediated induction of cyclooxygenase-2. J Biol Chem 1999; 274: 5038–5046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shneyvays V, Nawrath H, Jacobson KA, Shainberg A. Induction of apoptosis in cardiac myocytes by an A3 adenosine receptor agonist. Exp Cell Res 1998; 243: 383–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seligman AM, Karnovsky MJ, Wasserkrug HL, Hanker JS. Nondroplet ultrastructural demonstration of cytochrome oxidase activity with a polymerizing osmiophilic reagent, diaminobenzidine (DAB). J Cell Biol 1968; 38: 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien TY. A new generation of Ca2+indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem 1985; 260: 3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein dye binding. Anal Biochem 1976; 72: 248–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li AH, Moro S, Forsyth N, Melman N, Ji XD, Jacobson KA. Synthesis, CoMFA analysis, and receptor docking of 3,5-diacyl-2, 4-dialkylpyridine derivatives as selective A3 adenosine receptor antagonists. J Med Chem 1999; 42: 706–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim HO, Ji XD, Siddiqi SM, Olah ME, Stiles GL, Jacobson KA. 2-Substitution of N6-benzyladenosine-5′-uronamides enhances selectivity for A3 adenosine receptors. J Med Chem 1994; 37: 3614–3621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klotz KN, Lohse MJ, Schwabe U, Cristalli G, Vittori S, Grifantini M. 2-Chloro-N6-[3H]cyclopentyladenosine ([3H]CCPA) a high affinity agonist radioligand for A1adenosine receptors. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 1989; 340: 679–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seraydarian MW, Artaza L. Modification by adenosine of the effect of adriamycin on myocardial cells in culture. Cancer Res 1979; 39: 2940–2944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Newman RA, Hacker MP, Krakoff IH. Amelioration of adriamycin and daunorubicin myocardial toxicity by adenosine. Cancer Res 1981; 41: 3483–3488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tanaka Y, Yoshihara K, Tsuyuki M, Kamiya T. Apoptosis induced by adenosine in human leukemia HL-60 cells. Exp Cell Res 1994; 213: 242–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abbracchio MP, Ceruti S, Brambilla R, Franceschi C, Malorni W, Jacobson KA, von Lubitz DK, Cattabeni F. Modulation of apoptosis by adenosine in the central nervous system: a possible role for the A3receptor. Pathophysiological significance and therapeutic implications for neurodegenerative disorders. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1997; 825: 11–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olson HM, Young DM, Prieur AF, Roy LE, Reagen RL. Electrolyte and morphologic alterations of myocardium in adriamycin-treated rabbits. Am J Pathol 1974; 77: 439–454. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Caroni P, Villani F, Carafoli E. The cardiotoxic antibiotic doxorubicin inhibits the Na+/Ca2+exchange of dog heart sarcolemmal vesicles. FEBS Lett 1981; 130: 184–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shin Y, Daly JW, Jacobson KA. Activation of phosphoinositide breakdown and elevation of intracellular calcium in a rat RBL-2H3 mast cell line by adenosine analogs: involvement of A3-adenosine receptors?. Drug Dev Res 1996; 39: 36–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gewirtz DA. A critical evaluation of the mechanisms of action proposed for the antitumor effects of the anthracycline antibiotics adriamycin and daunorubicin. Biochem Pharmacol 1999; 57: 727–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bachur NR, Gordon SL, Gee MV. Anthracycline antibiotic augmentation of microsomal electron transport and free radical formation. Mol Pharmacol 1977; 13: 901–910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vanella A, Campisi A, di Giacomo C, Sorrenti V, Vanella G, Acquaviva R. Enhanced resistance of adriamycin-treated MCR-5 lung fibroblasts by increased intracellular glutathione peroxidase and extracellular antioxidants. Biochem Mol Med 1997; 62: 36–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Konorev EA, Kennedy MC, Kalyanaraman B. Cell-permeable superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase mimetics afford superior protection against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity: the role of reactive oxygen and nitrogen intermediates. Arch Biochem Biophys 1999; 368: 421–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maggirwar SB, Dhanraj DN, Somani SM, Ramkumar V. Adenosine acts as an endogenous activator of the cellular antioxidant defense system. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1994; 201: 508–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ramkumar V, Nie Z, Rybak LP, Maggiewar SB. Adenosine, antioxidant enzymes and cytoprotection. Trends Pharmacol Sci 1995; 16: 283–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Papadopoulou LC, Theophilidis G, Thomopoulos GN, Tsiftsoglou AS. Structural and functional impairment of mitochondria in adriamycin-induced cardiomyopathy in mice: suppression of cytochrome c oxidase II gene expression. Biochem Pharmacol 1999; 57: 481–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Papadopoulou LC, Tsiftsoglou AS. Mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase as a target site for daunomycin in K-562 cells and heart tissue. Cancer Res 1993; 53: 1072–1078. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dorr RT, Bozak KA, Shipp NG, Hendrix M, Alberts DS, Ahmann F. In vitro rat myocyte cardiotoxicity model for antitumor antibiotics using adenosine triphosphate/protein ratios. Cancer Res 1988; 48: 5222–5227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jeyaseelhan R, Poizat C, Wu HY, Kedes L. Molecular mechanisms of doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy. Selective suppression of Reiske iron-sulfur protein, ADP/ATP translocase, and phosphoÍfructokinase genes is associated with ATP depletion in rat cardiomyocytes. J Biol Chem 1997; 272: 5828–5832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Auchampach JA, Rizvi A, Qiu Y, Tang X-L, Maldonado C, Teschner S, Bolli R. Selective activation of A3 adenosine receptors with N6-(3-Iodobenzyl)adenosine-5′-N-methyluronamide protects against myocardial stunning and infarction without hemodynamic changes in conscious rabbits. Circ Res 1997; 80: 800–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liang BT, Jacobson KA. A physiological role of the adenosine A3 receptor: sustained cardioprotection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998; 95: 6995–6999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]