Abstract

Human immunodeficiency virus infection in humans and simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infection in rhesus macaques (RM) leads to a generalized loss of immune responses involving perturbations in T-cell receptor (TCR) signaling. In contrast, naturally SIV-infected sooty mangabeys (SM) remain asymptomatic and retain immune responses despite relatively high viral loads. However, SIV infection in both RM and SM led to similar decreases in TCR-induced Lck phosphorylation. In this study, a protein tyrosine kinase (PTK) differential display method was utilized to characterize the effects of in vivo SIV infection on key signaling molecules of the CD4+ T-cell signaling pathways. The CD4+ T cells from SIV-infected RM, but not SIV-infected SM, showed chronic downregulation of baseline expression of MLK3, PRK, and GSK3, and symptomatically SIV-infected RM showed similar downregulation of MKK3. In vitro TCR stimulation with or without CD28 costimulation of CD4+ T cells did not lead to the enhancement of gene transcription of these PTKs. While the CD4+ T cells from SIV-infected RM showed a significant increase of the baseline and anti-TCR-mediated ROR2 transcription, SIV infection in SM led to substantially decreased anti-TCR-stimulated ROR2 transcription. TCR stimulation of CD4+ T cells from SIV-infected RM (but not SIV-infected SM) led to the repression of CaMKKβ and the induction of gene transcription of MLK2. Studies of the function of these molecules in T-cell signaling may lead to the identification of potential targets for specific intervention, leading to the restoration of T-cell responses.

Increased susceptibility to opportunistic infections and a state of generalized immunosuppression are among the hallmarks of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-infected patients and simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-infected rhesus macaques (RM). Such a compromised immune state is not merely secondary to loss of CD4+ T cells since it precedes their depletion and a substantial frequency of CD4+ T cells that are not infected with HIV-1 demonstrate ineffective immune function.

Among the possible mechanisms for such a failure are either the direct (e.g., in the infected cells) or the indirect (e.g., in noninfected cells) effects that lentiviral infection exerts on intracellular signaling pathways in CD4+ T lymphocytes. Previous studies have shown that infection by HIV or SIV in vivo and incubation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) in vitro with either infectious virus or the viral proteins Nef, Tat, and envelope protein gp120 differentially affect T-cell stimulatory and costimulatory pathways (12, 29, 44). Cellular protein tyrosine kinases (PTKs) have been shown to play a critical role in multiple signaling pathways, including those involved in TCR activation pathways (reviewed in reference 8). Several HIV and/or SIV viral proteins have been shown to either directly or indirectly modulate these regulatory enzymes. HIV- or SIV-derived Nef proteins were shown to associate directly with Lck, T-cell-receptor (TCR) zeta chain, and the adapter protein Vav and exhibit complex effects on T-cell activation pathways (19, 27, 29). The envelope proteins gp120 and gp160 were shown to affect CD4 and coreceptor signaling, resulting in the modulation of TCR-mediated ERK/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and phospholipase C (PLC) pathways (9, 44). Finally, although the HIV-derived transactivator Tat protein has been shown to exert its function mostly at the transcriptional level, several reports have documented its effect on signaling through JNK, ERK/MAPK and PLC pathways in CD4+ T cells or cell lines (2, 3).

While SIV infection in RM resembles HIV infection in humans (21), naturally SIV-infected sooty mangabeys (SM) remain asymptomatic despite the fact that the animals experience viral loads similar to SIV-infected RM that develop AIDS (11). Interestingly, CD4+ T cells from SM (compared to RM cells) show high levels of baseline telomerase activity that further increases after SIV infection and lower rates of SIV-induced apoptosis (4, 58). Furthermore, while normal human and RM CD4+ T cells from uninfected donors require both TCR-mediated signal 1 and costimulatory signal 2 (e.g., CD28) to induce proliferation and interleukin-2 (IL-2) production, SM CD4+ T cells showed considerable activation and IL-2 synthesis with signal 1 alone, regardless of SIV status, and showed relative resistance to the development of immunological anergy in vitro (5). At the same time, while HIV-infected humans and SIV-infected RM were shown to gradually lose antigen-specific memory CD4 responses, SIV-seropositive SM fully retain such memory T-cell responses over time (5, 48, 53). This would suggest either that the multiple intracellular signaling defects seen in CD4+ T cells from HIV-infected humans and SIV-infected RM are not directly linked to disease progression or that the SM have developed unique mechanisms that maintain physiological CD4+ T-cell responses despite SIV infection. Clearly, the comparative analysis of the intracellular signaling pathways in SIV-infected disease-susceptible RM and SIV-infected disease-resistant SM may provide some important insights on the mechanism of dysfunction in one of the key cell lineages in human and nonhuman lentiviral infection, the CD4+ T cell.

In efforts to address potential differential effects of SIV on TCR mediated signaling and/or activation of CD4+ T cells in pathogenic and apathogenic infection, a PTK differential display analysis was performed on cells from uninfected and SIV-infected RM and SM. Several differences in tyrosine or serine/threonine kinase transcription were observed in relation to the SIV status and disease course. Of these, seven kinases showed substantial and significant differences as assessed by real-time PCR. Involvement of these kinases in various signaling cascades and their dysregulation may significantly contribute to the SIV induced differences in T-cell signaling, leading to distinct disease outcomes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells.

The peripheral blood samples utilized were obtained from normal, healthy adult RM (Macaca mulatta), SIVmac251-infected RM (after achievement of viral load set point 3 to 6 months postinfection) and adult healthy SIV-seronegative and -seropositive SM (Cercocebus atys) housed at the Yerkes Regional Primate Research Center of Emory University. Viral loads were determined by using quantitative-competitive reverse transcription-PCR (QC-RT-PCR) as previously described (37). All animals were maintained according to the guidelines of the Committee on the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, National Research Council, and Health and Human Services guidelines. CD4+ T cells (5 × 106 to 10 × 106) were separated from fresh or cryopreserved PBMC by using Dynabeads M450 CD4 (Dynal, Lake Success, N.Y.). The purity of the cell population was always >99.0% as determined by fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis.

PTK differential display.

Aliquots of the enriched CD4+ T cells were then incubated overnight in media alone (nonstimulated cells) or with medium containing anti-CD3 alone (clone FN18; Biosource International, Camarillo, Calif.) or anti-CD3/anti-CD28 (BD, San Jose, Calif.) antibody-conjugated immunobeads prepared as described elsewhere (6). RNA was harvested by using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.) and reverse transcribed by using random hexamer oligonucleotide primers. The protocol for differential display of tyrosine kinases was performed as described previously (46). First, the CD4+ T-cell cDNA was subjected to PCR by using two sets of degenerate primers (see below). The sense primers were labeled with [γ-32P]ATP (Amersham, Piscataway, N.J.) by end labeling them with T4PNK (Promega, Madison, Wis.). Each 50-μl PCR contained 3 mM MgCl2, 1× Mg-free PCR buffer (Promega), 200 μM concentrations of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, cDNA generated by RT of RNA from 0.5 × 106 cells, 5 U of Taq polymerase (Promega), and sets of degenerate primers as follows: (i) sense, 25 nM (5′-CCAGGTCACCAARRTWGGNGAYTTYGG-3′), 75 nM (5′-CCAGGTCACCAARRTIDCNGAYTTYGG-3′), 75 nM (5′-CCAGGTCACCAARRTTDCNGAYTTYGG-3′), 37.5 nM (5′-CCAGGTCACCAARRTIWGYGAYTTYGG-3′), and 37.5 nM (5′-CCAGGTCACCAARRTTWGYGAYTTYGG-3′); and (ii) antisense, 70 nM (5′-CACAGGTTACCRHANGMCCAAACRTC-3′), 70 nM (5′-CACAGGTTACCRHANGMCCACACRTC-3′), 70 nM (5′-CACAGGTTACCRHANGMCCAGACRTC-3′), 70 nM (5′-CACAGGTTACCRHANGMCCATACRTC-3′), 50 nM (5′-CACAGGTTACCRHARCTCCAYACRTC-3′), 50 nM (5′-CACAGGTTACCRHARCTCCARACRTC-3′), and 10 nM (5′-CACAGGTTACCRAACATCCAKACGTC-3′). The PCR cycles were as follows: denaturation for 5 min at 95°C; 5 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min 30 s at 45°C, and 15 s at 72°C; followed by 25 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min 30 s at 56°C, and 20 s at 72°C (plus 2 s/cycle). PCR products were then separated on 2.5% agarose gels (NuSieve Agarose; FMC, Rockland, Maine) in 0.5× Tris-acetate-EDTA (TAE) buffer with 0.5 μg of ethidium bromide/ml, and the desired band at 150 to 170 bp was excised. DNA was extracted from the gel by using Wizard PCR Prep kit (Promega) and reconstituted in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0). Radioactivity was measured in a liquid scintillation counter (Microbeta Trilux). Restriction digests were performed with an aliquot of each DNA fragment (15,000 to 20,000 cpm) in a total volume of 10 μl with the enzymes BbvI, BslI, BsrI, HpaII, MnlI, MwoI, and DdeI (all from NEB, Beverly, Mass.) for 60 min. Each reaction was then mixed with 7 μl of loading dye (98% deionized formamide, 10 mM EDTA [pH 8.0], 0.01% bromophenol blue, 0.01% xylene cyanol) and denatured at 80°C for 10 min; 4 μl of each sample was then electrophoresed on a 7% acrylamide-urea gel at 50 W. The gel was dried, and bands were visualized by using a phosphorimager (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.).

Cloning of PTK fragments.

The PTK patterns obtained from the samples were compared to the restriction pattern of known human PTK, and kinases corresponding to the differentially expressed bands were identified. RT-PCR was performed with kinase-specific primers amplifying ∼400-bp fragments that encompass the 160- to 170-bp fragment amplified by the differential display. Amplification products were subjected to Southern blot analysis with kinase-specific probes. Primers and probes utilized included: (i) MLK2 (sense, 5′-GGGCATGAACTACCTACACA-3′; antisense, 5′-AGATGSTACCGAAATCTGGC-3′; and probe, 5′-GGAGGCCATTCGAGAACCACA-3′); (ii) MLK3 (sense, 5′-ATGCACTACCTGCACTGCGA-3′; antisense, 5′-TCCAACTGCTGCAGGATGGA-3′; and probe, 5′-GAGGTTATCAAGGCCTCCACC-3′); (iii) MKK3 (sense, 5′-ATCCACAGAGATGTGAAGCC-3′; antisense, 5′-ACTGAGCAGTGAAGTCCACA-3′; and probe, 5′-ACGATGGATGCCGGCTGCAG-3′); (iv) CamKKβ (sense, 5′-CCCGTTTCTACTTCCAGGA-3′; antisense, 5′-CAAGTCCTCAGCTATGTCG-3′; and probe, 5′-TCTGAGACCCGCAAGATCTTC-3′); (v) ROR2 (sense, 5′-CTCCACGAATTCCTGGTCAT-3′; antisense, 5′-GGCTGTGGATGTCCTTGAAG-3′; and probe, 5′-CCATCATGTACGGCAAGTTCTCC-3′); and (vi) GSK3 (sense, 5′-GCCAAGTTGACCATCCCTAT-3′; antisense, 5′-CGGCGTTCGAGATTTGAACA-3′; and probe, 5′-CTGTCCTCAAGCTCTGCGATTTT-3′). The PCR products were cloned in pGEM-T vector (Promega) and sequenced, and sequences were analyzed by using the GCG Wisconsin Package analysis software (GCG, Madison, Wis.).

Western blotting.

Purified CD4+ T cells were incubated in medium alone or stimulated with anti-CD3 or anti-CD3/anti-CD28 antibody-conjugated immunobeads (as described above) for 10 min and lysed as described previously (7). Cell lysates (106 cells/sample) were separated in 10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and transferred to Immuno-Blot polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Bio-Rad), and membranes were blocked overnight with phosphate-buffered saline containing 3% milk and 20% fetal calf serum. Membranes were probed with anti-Lck monoclonal antibody (MAb; clone 3A5; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, Calif.). After the addition of goat anti-mouse-alkaline phosphatase conjugate (BioSource), the blots were developed by using the AP-Conjugate Substrate Kit (Bio-Rad).

Kinase-specific PCR and real-time PCR quantification.

cDNA samples were subjected to real-time PCR by using probe and antisense PCR primers (amplifying fragments of 100 to 200 nucleotides) in an iCycler (Bio-Rad) and SYBR-Green fluorescence quantification (PE Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). PCR conditions for each PTK sequence were optimized with regard to primer concentration (50 to 900 nM), annealing temperature, and primer-dimer formation. The parameters of the cycle were 95°C for 15 s, 56°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s. As a control, amplification of GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) fragment was performed with the primers 5′-ACCACCATGGAGAAGGCTGG-3′ and 5′-CAGTTGGTGGTGCAGGAGGC-3′. The target cDNA quantitation in different samples was then performed according to the directions of the manufacturer (Sybr-Green Kit; PE Biosystems) by first normalizing the threshold cycle number of the target gene to the GAPDH. The copy numbers of the target gene were then expressed relative to the calibrator sample. Each target sequence and GAPDH control was quantitated from two independent cDNA preparations, and the resulting relative quantitation is expressed as an average of two measurements.

Statistical analysis.

The data were analyzed by using the t test, and differences with a P value of <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

SIV infection downmodulates phosphorylation of lck.

It has been previously reported that the detection of several tyrosine kinases involved in proximal TCR signaling, such as Lck, Fyn, and ZAP70, was substantially decreased in advanced stages of HIV infection due to the posttranslational modification that corresponded to the loss of activity in these kinases (51). To address this issue in nonhuman primates and to investigate whether there are any differences in TCR-proximal signaling in symptomatic versus asymptomatic SIV infection, we analyzed the expression of Lck in both SIV-negative and -positive RM and SM. Figure 1 shows that while TCR stimulation by anti-CD3 antibody induces phosphorylation of Lck (band p-lck) in CD4+ T cells from uninfected animals from both species, SIV infection leads in both species to inhibition of anti-CD3 induced Lck phosphorylation. The phosphorylation of Lck did not increase in cells from SIV-infected animals even when both TCR and CD28 costimulatory signals were provided. The inhibitory effect of SIV on Lck phosphorylation did not seem to be secondary to the SIV-induced phosphorylation “defect,” since polyclonal activation of CD4+ T cells from these animals by PMA or ionomycin led to a substantial and proportionally comparable phosphorylation of Lck regardless of the SIV status (data not shown). However, with the 3E5 antibody we did not detect any apparent downmodulation of Lck expression after SIV infection in either species.

FIG. 1.

Effect of SIV infection on the expression and phosphorylation of Lck. Purified CD4+ cells from SIV-negative (SIV–) or SIV-positive (SIV+) RM and SM were either not stimulated (NS) or stimulated with anti-CD3-coated beads (αCD3) or anti-CD3/anti-CD28-coated beads (αCD3/28), and cell lysates were assayed for Lck by Western blot. Western blots show unphosphorylated p56-Lck (lck) and phosphorylated p58-Lck (p-lck); β-actin expression is used as control for the equivalent loading. Representative data from one animal from each group (consisting of at least three animals) are shown.

Differential gene transcription of several PTKs in pathogenic versus apathogenic SIV infection.

We have previously shown that CD4+ T cells from SM, but not from RM, that were subjected to an anergy-inducing protocol exhibited substantial ERK1/2 phosphorylation after TCR stimulation regardless of the SIV status (5). However, as seen in Fig. 1, the membrane-proximal TCR signaling events (phosphorylation of Lck) that we analyzed did not show any detectable differences between the two species before and after SIV infection. These data indicated that differences in CD4+ T-cell responses observed between SIV-infected RM and SM may possibly involve signaling differences located between TCR-proximal (Lck) and -distal (ERK1/2) signaling events. To address the issue of the effect of SIV infection on the signaling molecules involved in the “intermediate” segment of the signaling pathways and the complex effect of SIV on T-cell signaling, PTK differential displays were generated from CD4+ T cells from four groups of three to four adult experimental animals: SIV-naive healthy RM, SIV-infected RM, SIV-seronegative SM, and SIV-seropositive SM. The obtained data were analyzed with regard to the species-related and SIV-induced differences. A comparison of displays from SIV-infected animals between the two species led to the identification of several differences. However, only differences that were not present in SIV-naive animals of the two species were considered to exclude potential species-specific differences. In addition, to elucidate the possible influence of SIV infection on TCR signaling and T-cell activation, aliquots of these cells were cultured in medium alone (baseline) or were TCR stimulated (with anti-CD3 antibody) with or without CD28 costimulation. Only differences that were consistently observed in at least three animals in each group were identified as important for further study. These differences are illustrated in the representative displays in Fig. 2. The comparative analysis led to the tentative identification of protein kinases that showed differences in transcription between the groups (Table 1). Altogether, 13 candidate PTKs were identified, and 8 additional differentially expressed fragments that did not match any PTK in the database were found. These data indicate that there are indeed notable differences in both baseline and TCR stimulation-elicited expression of several kinases that seem to be distinct in samples from apathogenically versus pathogenically SIV-infected nonhuman primates.

FIG. 2.

Protein kinase differential display from CD4+ T cells. Purified CD4+ cells from SIV-negative (A) and SIV-positive (B) RM and SM were incubated in medium alone (lanes 0), with anti-CD3 (lanes 1)- or anti-CD3/CD28 (lanes 2)-coated beads, and protein kinase display assays were performed as described in Materials and Methods. Amplification products were digested with restriction enzymes and electrophoresed with 10-bp ladder (M) as the molecular mass marker. Representative digests with BslI, HpaII, MnlI, and DdeI are shown.

TABLE 1.

Summary of the differences in PTK transcription detected by the differential display and real-time PCR

| PTK | Fragment(s)a | Differential display (SIV+)b

|

Real-time PCRc

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RM | SM | RM | SM | ||

| MLK2 | Hpa 82, Mnl 28 | − | + | − | ∼ |

| MLK3 | Mwo 76 | − | + | − | ∼ |

| MKK3 | Bsl 89 | +/− | + | − | ∼ |

| GSK3 | Hpa 78 | − | + | − | ∼ |

| PRK | Dde 100 | − | + | − | ∼ |

| CamKKβ | Dde 101 | − | + | − | ∼ |

| ROR2 | Bbv 41 | + | − | + | ∼ |

| KKIALRE | Bsl 127, Hpa 125 | + | − | ∼ | ∼ |

| TEC3 | Dde 65 | + | − | ∼ | ∼ |

| ATK | Hpa 79 | + | − | ∼ | ∼ |

| KKIAMRE | Mnl 39 | +/− | − | ∼ | ∼ |

| TXK | Mnl 98 | +/− | + | ∼ | ∼ |

| EMK | Mnl 114 | − | + | ∼ | ∼ |

| UM1d | Bsl 150, Bsl 130 | + | − | NA | NA |

| UM2 | Dde 150, Dde 130 | + | − | NA | NA |

| UM3 | Dde 78 | + | − | NA | NA |

| UM4 | Hpa 150, Hpa 130 | + | − | NA | NA |

| UM5 | Mnl 49 | − | +/− | NA | NA |

Only the fragments present consistently in at least three animals are listed.

Denotes presence (+) or absence (−) of signal in infected animals of each species.

Denotes positive (+), negative (−), or no difference (∼) in real-time PCR in SIV+ versus SIV− animals. NA, not applicable.

UM1 to UM5 refer to unmatched fragments 1 to 5.

PTKs from nonhuman primates are highly homologous to their human counterparts.

While the data from the differential display showed clear differences in transcription patterns, it could not be excluded that some of these differences were perhaps due to sequence variations between the two nonhuman primate species and humans, which could have led to aberrant restriction patterns. To exclude this possibility and to validate the assay, ∼400-bp cDNA fragments (encompassing an ∼160-bp conserved region amplified by the PTK display procedure) of MLK2, MLK3, MKK3, GSK3, ROR2, CaMKKβ, and PRK were amplified with specific primers, cloned, and sequenced, and the sequences were compared to the published human sequences. All of these PTKs showed 95 to 99% DNA sequence homology to their human homologues, and none of the sequences exhibited substitutions in restriction sites that would lead to restriction patterns different from those of humans and therefore invalidate the results. These findings confirm that the differences observed in the differential display were indeed real differences in specific gene transcription.

Quantitative differences in gene transcription of PTK in SIV infection.

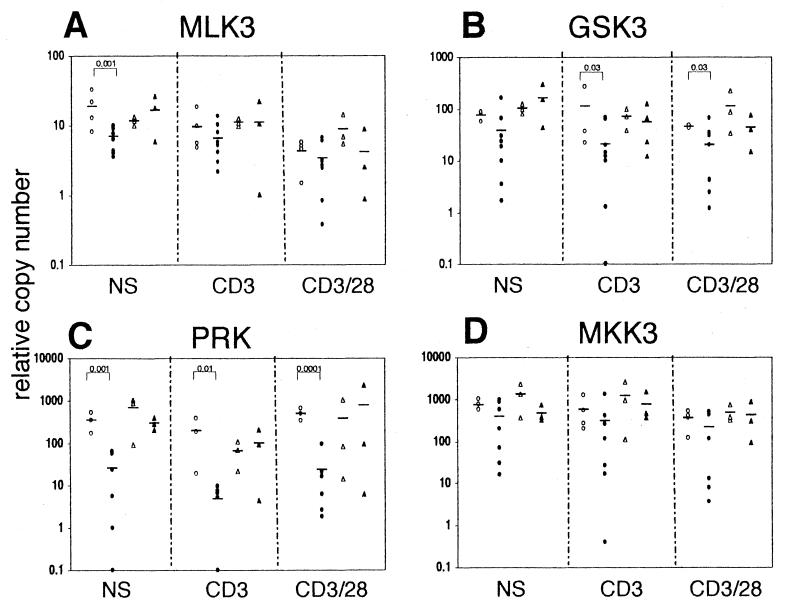

The differential display technique, while very useful for assessing overall differences in PTK expression, is only semiquantitative. In addition, PTK amplification is performed with degenerate primers amplifying the whole pool of cellular PTKs. Subsequently, more than one PTK can generate restriction fragments of the same size, and therefore it is possible that some bands contain more than one candidate PTK. Finally, the differences in the transcription of mRNA specific for one PTK can be “masked” by increased transcription of another mRNA giving the same restriction fragment in the particular restriction digest. Therefore, in efforts to confirm and further quantitate the differences detected by the differential display, the preselected PTKs were subjected to kinase-specific real-time PCR amplification. Figure 3 shows that SIV infection in RM induces downregulation of gene transcription of MLK3, MKK3, GSK3, and PRK in CD4+ T cells but had no marked effect on the transcription of these protein kinases in SM CD4+ T cells. A modest (∼3-fold) but highly significant (P = 0.001) decrease in transcription of MLK3 in SIV-infected RM was observed only in nonstimulated cells (Fig. 3A). In CD4+ T cells from SIV-infected RM, the levels of GSK3 transcription (Fig. 3B) show a significant 5- to 10-fold decrease in signal I- and signal I+II-stimulated cells (P = 0.03 for both anti-CD3- and anti-CD3/anti-CD28-stimulated cells). Similarly, there was an even more pronounced (>10-fold) decrease in transcription of PRK regardless of stimulation (P = 0.001 for nonstimulated, P = 0.01 for anti-CD3-stimulated, and P = 0.0001 for anti-CD3/anti-CD28-stimulated cells) (Fig. 3C). The transcription of MKK3 did not show any apparent differences in SIV-infected RM (Fig. 3D). However, Fig. 4A shows that MKK3 transcription decreased in SIV-infected RM in correlation with viral load. Thus, while the repression was pronounced and significant in animals with viral load >106 vRNA/ml (P = 0.0002 for basal and P = 0.011 for anti-CD3-stimulated transcription), in animals with a low viral load (<106 vRNA/ml), levels were comparable to those observed in noninfected animals. Similarly, the data show a gradual effect of the SIV viral load on transcription of ROR2 and GSK3 (Fig. 4B and C).

FIG. 3.

Select protein kinases are downregulated in pathogenic SIV infection. CD4+ cells from SIV-negative RM (○), SIV-infected RM (●), SIV-seronegative SM (▵), and SIV-seropositive SM (▴) were cultured in medium alone (NS) or stimulated with beads coated with anti-CD3 (CD3) or anti-CD3/anti-CD28 (CD3/28) antibodies. The transcription levels of MLK3 (A), GSK3 (B), PRK (C), and MKK3 (D) were assessed by real-time PCR, normalized to GAPDH, and expressed as copy numbers relative to the calibrator sample. Horizontal bars indicate mean of each group and P values for statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) are listed.

FIG. 4.

Dysregulation of MKK3, GSK3, and ROR2 correlates with viral load in RM. CD4+ T cells from SIV-negative RM (○), SIV-infected RM with a viral load of <106 vRNA/ml (□), and SIV-infected RM with a viral load of >106 vRNA/ml (●) were cultured in medium alone (NS), stimulated with anti-CD3 (CD3), or stimulated with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 (CD3/28) antibody-coated beads. The transcription of selected protein kinases was assessed by real-time PCR, normalized to GAPDH, and expressed as copy numbers relative to the calibrator sample. Horizontal bars indicate the mean of each group, and P values for statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) are given.

The effect of SIV infection on the transcription of MLK2, ROR2, and CaMKKβ was more complex. For ROR2 (Fig. 5A), SIV infection in SM led to an unchanged level of basal transcription and a 5- to 10-fold decrease in anti-CD3 or anti-CD3/anti-CD28-stimulated transcription (P = 0.05 and 0.02, respectively). However, there was a significant (10–100-fold) increase in ROR2 transcription in SIV-positive RM in both nonstimulated and stimulated cells (P = 0.005 for nonstimulated, 0.03 for anti-CD3- and 0.01 for anti-CD3/anti-CD28-stimulated cells). In addition, there was a positive correlation between viral load and the magnitude of increase of ROR2 transcription in SIV-infected RM, e.g., the increase was less pronounced in the animals harboring <106 vRNA of the virus/ml (Fig. 4C). Figure 5B shows that SIV infection significantly decreased CaMKKβ transcription in anti-CD3-stimulated cells from RM (but not from SM) compared to both the nonstimulated infected cells and the anti-CD3-stimulated noninfected cells (P = 0.03 and 0.006, respectively). The basal levels of MLK2 transcription showed the highest variability between individual samples, although the average values in different groups were comparable (range, 0.1 to 0.5). However, Fig. 5C clearly shows that while anti-CD3 stimulation of CD4+ T cells from SIV-infected RM led to a consistent increase of MLK2 transcription, there was no apparent effect or decrease in all of the other experimental animal groups.

FIG. 5.

Complex effect of SIV infection on the transcription of ROR2, CaMKKβ, and MLK2. (A and B) CD4+ cells from SIV-negative RM (○), SIV-infected RM (●), SIV-seronegative SM (▵), and SIV-seropositive SM (▴) were cultured in medium alone (NS) or were stimulated with beads coated with anti-CD3 antibody with (CD3/28) or without (CD3) antibody. The transcription of selected protein kinases was assessed by real-time PCR, normalized to GAPDH, and expressed as copy numbers relative to the calibrator sample. Horizontal bars indicate the mean of each group, and P values for statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) are listed. (C) The levels of transcription of MLK2 in SIV-seropositive (RM+) or SIV-seronegative (RM–) RM and in SIV-seronegative (SM-) or SIV-seropositive (SM+) SM were determined as in panel A. The dotted line connects values from individual animals.

These data indicate that there indeed are significant quantitative differences in several protein kinases that distinguish pathogenic from apathogenic SIV infection and that the degree of dysregulation of transcription of select kinases (MKK3, GSK3, and ROR2) correlates with viral load and stage of the disease in SIV-infected RM.

DISCUSSION

CD4+ T lymphocytes are the primary target cells of HIV or SIV infection, and HIV-infected humans and SIV-infected RM exhibit both net loss and a functional impairment of CD4+ T cells, leading to the development of AIDS. Functional dysregulation of both infected and uninfected cells leads to impaired recall immune responses and activation patterns, resulting in a state of immunological anergy. However, the existence of several nonhuman primate species, i.e., natural hosts of SIV such as SM, that exhibit high levels of productive infection and replication with no symptoms of immunodeficiency and AIDS suggests that these species have developed mechanisms that either antagonize or compensate for the negative effect of SIV. Elucidating these mechanisms not only would help in the understanding of HIV- and SIV-induced pathogenesis but might also have direct implications for potential novel treatment strategies.

The analysis of select proximal TCR signaling events—the expression and phosphorylation of Lck—showed that SIV infection in both RM and SM leads to the inhibition of TCR-induced Lck phosphorylation. Previously published data showed “downmodulation” of Lck-specific signal accompanied by the loss of kinase function in CD4+ T cells from HIV-infected humans. This downmodulation was secondary to posttranslational modification, leading to the decreased reactivity of Lck with 1F6 antibody clone but not with C-terminus-specific antibody (51). It is therefore possible that the 3E5 clone of anti-Lck MAb that we used similarly recognizes an epitope not affected by the potential SIV-mediated posttranslational modification. Lck was shown to have a critical role in the initiation of signaling after TCR engagement (reviewed in reference 8), and several studies have reported multiple mechanisms by which lentivirus infection can lead to the Lck signaling impairment. Thus, gp120 was shown to downmodulate Lck expression along with CD4 (10) and to inhibit CD4-Lck-CD3 interaction and signaling (28, 31). Interestingly, SIV Nef (contrary to HIV Nef) was shown to activate Lck in vitro (22). Our finding of inhibition of TCR-induced phosphorylation of Lck in SIV-infected animals may thus reflect an overall complex negative effect of SIV infection in vivo rather than an isolated effect of SIV Nef in vitro. However, this SIV-induced impairment of proximal signaling does not translate into the loss of T-cell recall responses or downstream TCR-MAPK signaling in chronically infected SM (5). These data indicated that the potential signaling differences between symptomatic and asymptomatic SIV may lie in between membrane-proximal and -distal segments of T-cell signaling pathways. To obtain more complex information regarding the potential effects of SIV on the signal transduction of TCR-mediated signaling, we utilized the PTK differential display method and compared PTK patterns of nonactivated and activated cells (stimulated by anti-CD3 or anti-CD3/anti-CD28 antibodies). It should be noted that the comparison of the differential display patterns was performed from the perspective of SIV-induced differences in apathogenic (SM) and pathogenic (RM) infection. The potential differences characteristic for the species, e.g., those prominent in uninfected animals, were not considered in this study. The differential display method designed for use with human sequences was first “validated” for the use in nonhuman primates by cloning and sequencing representative fragments of PTKs. The high degree of homology of the cloned sequences from select protein kinases from RM and SM to their corresponding human homologues, along with identical restriction patterns, indicated that the methodology is applicable for use in nonhuman primates without any substantial modification. Comparison of the results obtained by the differential display method and real-time PCR showed (Table 1) that >50% differences of picked up by the differential display (7 of 13) were matched by the real-time PCR results. It is possible that, for the PTKs showing discordant results, the differential display method is less sensitive for the amplification with degenerate primers on the background of the pool of all cellular PTK cDNAs. Alternatively, the differences may actually represent new, as-yet-unidentified PTKs with no match in the database. In addition, several differentially expressed fragments were not matched altogether, indicating that there are indeed as-yet-unidentified PTKs or related molecules that may play a role in the T-cell signaling. Approaches utilizing direct cloning from the gel methods are currently being utilized to identify these molecules. The differential display method used is limited to the specific group of target sequences (PTKs) and may not provide as thorough a screening procedure as do the microarray techniques. However, the advantage of the differential display technique lies in the fact that much less RNA is needed for the experiment (requiring typically RNA from ∼0.5 × 106 cells) compared to the available microarray techniques, which typically require 1- to 2-log-higher numbers of cells. This is critical in conditions for which the amount of material is limited, such as with CD4+ T cells in HIV-infected humans or SIV-infected RM.

Signaling elicited by TCR engagement on T lymphocytes with or without concurrent costimulation elicits activation of intracellular signal transduction cascades that lead to cell activation, anergy, or apoptosis. Three major MAPK cascades are involved in TCR signaling: MAPK/ERK, SAPK/JNK, and p38 (for a review, see reference 30). TCR-proximal signaling involves recruitment and phosphorylation of Src family kinases (Lck, Fyn, or ZAP70), leading to the phosphorylation of the adapter proteins LAT and SLP76 (56). Activated adapter proteins facilitate the assembly of signaling complexes that then relay the signal to the particular MAPK pathway. All three MAPK pathways contain three stage signaling cascades (reviewed in reference 33) in which the successive activation of cascade MAPK-kinase-kinases (MAPK3Ks)—MAPK/ERK kinase (MKK) and MAPK (such as ERK, JNK, and p38)—leads to the regulation of transcription (AP1, NFAT) or mediates cytoskeleton changes, chromatin remodeling, or translational changes. MAPK3Ks are entry points of the signaling cascade and are regulated by the upstream proximal events. Our data show differential transcription of three kinases that are directly involved in JNK and p38 pathways, i.e., MLK2, MLK3, and MKK3. The two MLKs MLK2 and MLK3 are MAPK3Ks that are SAPK/JNK pathway specific and activate MKK4 and MKK7 (direct activators of JNK) and MKK3 (an activator of p38), respectively (24, 25, 54, 55). It has been proposed that tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α)- and IL-1-induced signaling is mediated through the activation of MLK2-MKK7 (14), and both MLK2 and MLK3 were shown to interact with activated forms of Rac1, Cdc42, and proteins involved in cellular motor complexes (38). MLK3 was shown to be involved in the regulation of transcription of IL-2 and IL-4 (23, 26). The MKK3 is (together with MKK6) a specific activator of p38 (17) involved in the regulation of expression of IL-8, TNF-α, and IL-12 (35, 39). It was shown in T cells that p38 and JNK synergize (together with the ERK pathway) in the TCR/CD28-mediated T-cell activation (18, 36, 57) in response to the cytokines IL-2 and IL-7 (13). Therefore, the modest decrease of constitutive transcription of MLK3 in SIV-infected RM and constitutive and stimulated transcription of MKK3 in symptomatically SIV-infected RM, but not in asymptomatically infected SM, may have important implications. Although the binding of SIV to cells was shown to elicit the activation of all three MAPK pathways (45), the detected low levels of MLK3 and MKK3 in chronically SIV-infected symptomatic monkeys may represent a feedback response to continuous stimulation by the virus in infected organisms. Alternatively, they may be directly affected and downregulated by the virus. However, the effect of HIV and SIV on the downstream signaling cascades has not been well defined. Interestingly, while the baseline levels of MLK2 transcription were comparable in both species regardless of the SIV status, the transcription levels in anti-CD3-stimulated cells from SIV-infected RM showed an approximately fivefold increase above baseline compared to an approximately fivefold decrease in noninfected animals.

The CaMKKβ is a part of the Ca2+-dependent calmodulin pathway, which was shown to be involved in T-cell activation (1, 50). Therefore, the downmodulation of CaMKKβ in the CD4+ T cells from SIV-infected RM may have important consequences for the potentiation of signals required for T-cell activation. Interestingly, the decrease of transcription of this protein kinase was detected only in anti-CD3 stimulated, but not in nonstimulated or anti-CD3/anti-CD28-stimulated CD4+ T cells from SIV-infected RM. This would suggest that there is a specific additive effect of pathogenic SIV infection and TCR stimulation without costimulation.

The most pronounced effect of SIV infection and differences between pathogenic and apathogenic SIV infection were observed in the expression of three protein kinases—ROR2, GSK3, and PRK—the functions of which remain poorly defined. The role of the receptor tyrosine kinase ROR2 has thus far only been studied in the context of its role in the development of neural tissue, heart, and cartilage (16, 41, 52). Interestingly, our data show that of all of the protein kinases tested, ROR2 exhibited the most profound differences between pathogenic and apathogenic SIV infection. While the SIV infection in SM induced no significant change (nonstimulated cells) or a 5- to 10-fold decrease in stimulated ROR2 expression, SIV infection of RM induced an overall 10- to 100-fold increase in ROR2 transcription, regardless of the stimulus. Further studies of a possible role of ROR2 in T-cell signaling are therefore warranted, since it may lead to progress in our understanding of virus-host interactions.

We have also detected marked downregulation (10- to 50-fold) of GSK3 and PRK (proliferation related kinase) in CD4+ T cells from SIV-infected RM. GSK3 was implicated in insulin signaling and the modulation of several transcription factors, such as AP-1, CREB, and C/EBP (15, 20, 32, 40, 47). PRK was shown to play a role in regulation of M-phase functions during the cell cycle (42, 43). Clearly, further studies are needed to elucidate the role of these two protein kinases in T cells and in SIV-induced pathogenesis.

Taken together, our data show clear differences in CD4+ T-cell downstream signaling pathways between symptomatic and asymptomatic SIV infection. It should be kept in mind that these are changes that occur in the whole CD4+ T-cell population and therefore may reflect both changes in the gene transcription induced by SIV in individual cells and changes related to the potential perturbations in SIV-induced cell subpopulations. Indeed, RM show an increase in the CD4+ CD45RA+ CD62L+ (naive) cells after SIV infection that is not observed in SM after SIV seroconversion (data not shown). However, there is a substantial evidence from both our own and other laboratories demonstrating the effects of HIV and SIV infection on TCR signaling in vivo and in vitro (5, 9, 12, 19, 27, 29, 34, 44, 49), suggesting that the data derived in this study may indeed reflect true differences occuring in cells rather than the shifts in cell populations. In either case, however, the data presented here reflect the differences in CD4+ T lymphocyte signaling patterns directly related to the pathogenic SIV infection. Further studies that would address this issue and elucidate the precise functions of the dysregulated protein kinases may provide important clues for the mechanisms of T-cell signaling and HIV- and SIV-mediated dysregulation of T-cell function. Moreover, the results of such studies may lead to possible intervention strategies that will be useful in immune reconstitution therapy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by amFAR grant 70518-28-RFI to P.B. and NIH grant RO1 AI27057 to A.A.A.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson K A, Ribar T J, Illario M, Means A R. Defective survival and activation of thymocytes in transgenic mice expressing a catalytically inactive form of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IV. Mol Endocrinol. 1997;11:725–737. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.6.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borgatti P, Zauli G, Cantley L C, Capitani S. Extracellular HIV-1 Tat protein induces a rapid and selective activation of protein kinase C (PKC)-alpha, -epsilon, and -zeta isoforms in PC12 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;242:332–337. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borgatti P, Zauli G, Colamussi M L, Gibellini D, Previati M, Cantley L L, Capitani S. Extracellular HIV-1 Tat protein activates phosphatidylinositol 3- and Akt/PKB kinases in CD4+ T lymphoblastoid Jurkat cells. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:2805–2811. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830271110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bostik P, Brice G T, Greenberg K P, Mayne A E, Villinger F, Lewis M G, Ansari A A. Inverse correlation of telomerase activity/proliferation of CD4+ T lymphocytes and disease progression in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected nonhuman primates. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000;24:89–99. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200006010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bostik P, Mayne A E, Villinger F, Greenberg K P, Powell J D, Ansari A A. Relative resistance in the development of T cell anergy in CD4+ T cells from simian immunodeficiency virus disease-resistant sooty mangabeys. J Immunol. 2001;166:506–516. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brice G T, Riley J L, Villinger F, Mayne A, Hillyer C D, June C H, Ansari A A. Development of an animal model for autotransfusion therapy: in vitro characterization and analysis of anti-CD3/CD28 expanded cells. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1998;19:210–220. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199811010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brice G T, Villinger F, Mayne A, Sundstrom J B, Ansari A A. Detection of intracellular signal transduction molecules in PBMC from rhesus macaques and sooty mangabeys. J Med Primatol. 1996;25:210–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.1996.tb00018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cantrell D. T cell antigen receptor signal transduction pathways. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:259–274. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cefai D, Debre P, Kaczorek M, Idziorek T, Autran B, Bismuth G. Human immunodeficiency virus-1 glycoproteins gp120 and gp160 specifically inhibit the CD3/T cell-antigen receptor phosphoinositide transduction pathway. J Clin Investig. 1990;86:2117–2124. doi: 10.1172/JCI114950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cefai D, Ferrer M, Serpente N, Idziorek T, Dautry-Varsat A, Debre P, Bismuth G. Internalization of HIV glycoprotein gp120 is associated with down-modulation of membrane CD4 and p56lck together with impairment of T cell activation. J Immunol. 1992;149:285–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chakrabarti L A, Lewin S R, Zhang L, Gettie A, Luckay A, Martin L N, Skulsky E, Ho D D, Cheng-Mayer C, Marx P A. Normal T-cell turnover in sooty mangabeys harboring active simian immunodeficiency virus infection. J Virol. 2000;74:1209–1223. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.3.1209-1223.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chirmule N, Than S, Khan S A, Pahwa S. Human immunodeficiency virus Tat induces functional unresponsiveness in T cells. J Virol. 1995;69:492–498. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.1.492-498.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crawley J B, Rawlinson L, Lali F V, Page T H, Saklatvala J, Foxwell B M. T cell proliferation in response to interleukins 2 and 7 requires p38MAP kinase activation. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:15023–15027. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.23.15023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cuenda A, Dorow D S. Differential activation of stress-activated protein kinase kinases SKK4/MKK7 and SKK1/MKK4 by the mixed-lineage kinase-2 and mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MKK) kinase-1. Biochem J. 1998;333:11–15. doi: 10.1042/bj3330011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Groot R P, Auwerx J, Bourouis M, Sassone-Corsi P. Negative regulation of Jun/AP-1: conserved function of glycogen synthase kinase 3 and the Drosophila kinase shaggy. Oncogene. 1993;8:841–847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DeChiara T M, Kimble R B, Poueymirou W T, Rojas J, Masiakowski P, Valenzuela D M, Yancopoulos G D. Ror2, encoding a receptor-like tyrosine kinase, is required for cartilage and growth plate development. Nat Genet. 2000;24:271–274. doi: 10.1038/73488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Derijard B, Raingeaud J, Barrett T, Wu I H, Han J, Ulevitch R J, Davis R J. Independent human MAP-kinase signal transduction pathways defined by MEK and MKK isoforms. Science. 1995;267:682–685. doi: 10.1126/science.7839144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DeSilva D R, Jones E A, Feeser W S, Manos E J, Scherle P A. The p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in activated and anergic Th1 cells. Cell Immunol. 1997;180:116–123. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1997.1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fackler O T, Luo W, Geyer M, Alberts A S, Peterlin B M. Activation of Vav by Nef induces cytoskeletal rearrangements and downstream effector functions. Mol Cell. 1999;3:729–739. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)80005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fiol C J, Williams J S, Chou C H, Wang Q M, Roach P J, Andrisani O M. A secondary phosphorylation of CREB341 at Ser129 is required for the cAMP-mediated control of gene expression. A role for glycogen synthase kinase-3 in the control of gene expression. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:32187–32193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gale M J, Jr, Ledbetter J A, Schieven G L, Jonker M, Morton W R, Benveniste R E, Clark E A. CD4 and CD8 T cells from SIV-infected macaques have defective signaling responses after perturbation of either CD3 or CD2 receptors. Int Immunol. 1990;2:849–858. doi: 10.1093/intimm/2.9.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greenway A L, Dutartre H, Allen K, McPhee D A, Olive D, Collette Y. Simian immunodeficiency virus and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef proteins show distinct patterns and mechanisms of Src kinase activation. J Virol. 1999;73:6152–6158. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.6152-6158.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hehner S P, Li-Weber M, Giaisi M, Droge W, Krammer P H, Schmitz M L. Vav synergizes with protein kinase CTheta to mediate IL-4 gene expression in response to CD28 costimulation in T cells. J Immunol. 2000;164:3829–3836. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.7.3829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hirai S, Katoh M, Terada M, Kyriakis J M, Zon L I, Rana A, Avruch J, Ohno S. MST/MLK2, a member of the mixed lineage kinase family, directly phosphorylates and activates SEK1, an activator of c-Jun N-terminal kinase/stress-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:15167–15173. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.24.15167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirai S, Noda K, Moriguchi T, Nishida E, Yamashita A, Deyama T, Fukuyama K, Ohno S. Differential activation of two JNK activators, MKK7 and SEK1, by MKN28-derived nonreceptor serine/threonine kinase/mixed lineage kinase 2. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:7406–7412. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.13.7406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoffmeyer A, Avots A, Flory E, Weber C K, Serfling E, Rapp U R. The GABP-responsive element of the interleukin-2 enhancer is regulated by JNK/SAPK-activating pathways in T lymphocytes. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:10112–10119. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.17.10112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Howe A Y, Jung J U, Desrosiers R C. Zeta chain of the T-cell receptor interacts with Nef of simian immunodeficiency virus and human immunodeficiency virus type 2. J Virol. 1998;72:9827–9834. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.9827-9834.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hubert P, Bismuth G, Korner M, Debre P. HIV-1 glycoprotein gp120 disrupts CD4–p56lck/CD3-T cell receptor interactions and inhibits CD3 signaling. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:1417–1425. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iafrate A J, Bronson S, Skowronski J. Separable functions of Nef disrupt two aspects of T cell receptor machinery: CD4 expression and CD3 signaling. EMBO J. 1997;16:673–684. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.4.673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kane L P, Lin J, Weiss A. Signal transduction by the TCR for antigen. Curr Opin Immunol. 2000;12:242–249. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(00)00083-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kanner S B, Haffar O K. HIV-1 down-regulates CD4 costimulation of TCR/CD3-directed tyrosine phosphorylation through CD4/p56lck dissociation. J Immunol. 1995;154:2996–3005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim L, Kimmel A R. GSK3, a master switch regulating cell-fate specification and tumorigenesis. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2000;10:508–514. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kyriakis J M, Avruch J. Mammalian mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathways activated by stress and inflammation. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:807–869. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liegler T J, Stites D P. HIV-1 gp120 and anti-gp120 induce reversible unresponsiveness in peripheral CD4 T lymphocytes. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1994;7:340–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu H T, Yang D D, Wysk M, Gatti E, Mellman I, Davis R J, Flavell R A. Defective IL-12 production in mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase kinase 3 (MKK3)-deficient mice. EMBO J. 1999;18:1845–1857. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.7.1845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matsuda S, Moriguchi T, Koyasu S, Nishida E. T lymphocyte activation signals for interleukin-2 production involve activation of MKK6–p38 and MKK7-SAPK/JNK signaling pathways sensitive to cyclosporin A. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:12378–12382. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.20.12378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mori K, Yasutomi Y, Sawada S, Villinger F, Sugama K, Rosenwith B, Heeney J L, Uberla K, Yamazaki S, Ansari A A, Rubsamen-Waigmann H. Suppression of acute viremia by short-term postexposure prophylaxis of simian/human immunodeficiency virus SHIV-RT-infected monkeys with a novel reverse transcriptase inhibitor ( GW420867) allows for development of potent antiviral immune responses resulting in efficient containment of infection. J Virol. 2000;74:5747–5753. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.13.5747-5753.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nagata K, Puls A, Futter C, Aspenstrom P, Schaefer E, Nakata T, Hirokawa N, Hall A. The MAP kinase kinase kinase MLK2 co-localizes with activated JNK along microtubules and associates with kinesin superfamily motor KIF3. EMBO J. 1998;17:149–158. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.1.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nick J A, Avdi N J, Young S K, Lehman L A, McDonald P P, Frasch S C, Billstrom M A, Henson P M, Johnson G L, Worthen G S. Selective activation and functional significance of p38alpha mitogen-activated protein kinase in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated neutrophils. J Clin Investig. 1999;103:851–858. doi: 10.1172/JCI5257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nikolakaki E, Coffer P J, Hemelsoet R, Woodgett J R, Defize L H. Glycogen synthase kinase 3 phosphorylates Jun family members in vitro and negatively regulates their transactivating potential in intact cells. Oncogene. 1993;8:833–840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oishi I, Takeuchi S, Hashimoto R, Nagabukuro A, Ueda T, Liu Z J, Hatta T, Akira S, Matsuda Y, Yamamura H, Otani H, Minami Y. Spatio-temporally regulated expression of receptor tyrosine kinases, mRor1, mRor2, during mouse development: implications in development and function of the nervous system. Genes Cells. 1999;4:41–56. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1999.00234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ouyang B, Li W, Pan H, Meadows J, Hoffmann I, Dai W. The physical association and phosphorylation of Cdc25C protein phosphatase by Prk. Oncogene. 1999;18:6029–6036. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ouyang B, Pan H, Lu L, Li J, Stambrook P, Li B, Dai W. Human Prk is a conserved protein serine/threonine kinase involved in regulating M phase functions. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:28646–28651. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.45.28646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Popik W, Hesselgesser J E, Pitha P M. Binding of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 to CD4 and CXCR4 receptors differentially regulates expression of inflammatory genes and activates the MEK/ERK signaling pathway. J Virol. 1998;72:6406–6413. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.8.6406-6413.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Popik W, Pitha P M. Early activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase, extracellular signal-regulated kinase, p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase, and c-Jun N-terminal kinase in response to binding of simian immunodeficiency virus to Jurkat T cells expressing CCR5 receptor. Virology. 1998;252:210–217. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Robinson D, He F, Pretlow T, Kung H J. A tyrosine kinase profile of prostate carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:5958–5962. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.5958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ross S E, Erickson R L, Hemati N, MacDougald O A. Glycogen synthase kinase 3 is an insulin-regulated C/EBPα kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:8433–8441. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.12.8433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sabbaj S, Para M F, Fass R J, Adams P W, Orosz C G, Whitacre C C. Quantitation of antigen-specific immune responses in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected individuals by limiting dilution analysis. J Clin Immunol. 1992;12:216–224. doi: 10.1007/BF00918092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Selliah N, Finkel T H. HIV-1 NL4-3, but Not IIIB, Inhibits JAK3/STAT5 activation in CD4+ T cells. Virology. 2001;286:412–421. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.0994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Soderling T R. The Ca-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase cascade .Trends Biochem. Sci. 1999;24:232–236. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01383-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stefanova I, Saville M W, Peters C, Cleghorn F R, Schwartz D, Venzon D J, Weinhold K J, Jack N, Bartholomew C, Blattner W A, Yarchoan R, Bolen J B, Horak I D. HIV infection-induced posttranslational modification of T cell signaling molecules associated with disease progression. J Clin Investig. 1996;98:1290–1297. doi: 10.1172/JCI118915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Takeuchi S, Takeda K, Oishi I, Nomi M, Ikeya M, Itoh K, Tamura S, Ueda T, Hatta T, Otani H, Terashima T, Takada S, Yamamura H, Akira S, Minami Y. Mouse Ror2 receptor tyrosine kinase is required for the heart development and limb formation. Genes Cells. 2000;5:71–78. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2000.00300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Teeuwsen V J, Siebelink K H, de Wolf F, Goudsmit J, UytdeHaag F G, Osterhaus A D. Impairment of in vitro immune responses occurs within 3 months after HIV-1 seroconversion. AIDS. 1990;4:77–81. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199001000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tibbles L A, Ing Y L, Kiefer F, Chan J, Iscove N, Woodgett J R, Lassam N J. MLK-3 activates the SAPK/JNK and p38/RK pathways via SEK1 and MKK3/6. EMBO J. 1996;15:7026–7035. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tournier C, Whitmarsh A J, Cavanagh J, Barrett T, Davis R J. The MKK7 gene encodes a group of c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase kinases. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:1569–1581. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.2.1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.van Leeuwen J E, Samelson L E. T cell antigen-receptor signal transduction. Curr Opin Immunol. 1999;11:242–248. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(99)80040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Varga G, Dreikhausen U, Kracht M, Appel A, Resch K, Szamel M. Molecular mechanisms of T lymphocyte activation: convergence of T cell antigen receptor and IL-1 receptor-induced signaling at the level of IL-2 gene transcription. Int Immunol. 1999;11:1851–1862. doi: 10.1093/intimm/11.11.1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Villinger F, Folks T M, Lauro S, Powell J D, Sundstrom J B, Mayne A, Ansari A A. Immunological and virological studies of natural SIV infection of disease-resistant nonhuman primates. Immunol Lett. 1996;51:59–68. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(96)02556-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]