Abstract

This study examined the role of endothelin ETA and ETB receptors on haemodynamic compensation following haemorrhage (−17.5 ml kg−1) in thiobutabarbitone-anaesthetized rats. Rats were divided into four groups (n=6 each): time-control, haemorrhage-control, haemorrhage after treatment with FR 139317 (ETA-receptor antagonist), and haemorrhage after treatment with BQ-788 (ETB-receptor antagonist).

In the time-control rats, there were no significant changes in any haemodynamics for the duration of the experiments. Relative to the time-control rats, rats given haemorrhage had reduced mean arterial pressure (MAP), cardiac output (CO) and mean circulatory filling pressure (MCFP), but increased systemic vascular resistance (RSV). Venous resistance (RV) was slightly (but insignificantly) reduced by haemorrhage. MAP, however, gradually returned towards baseline (−17±4 and −3±2 mmHg at 10 and 60 min after haemorrhage, respectively) as a result of a further increase in RSV.

Pre-treatment with FR 139317 (i.v. 1 mg kg−1, followed by 1 mg kg−1 h−1) accentuated haemorrhage-induced hypotension through abolition of the increase in RSV. FR 139317 did not modify haemorrhage-induced changes in CO, MCFP and RV.

Pre-treatment of BQ-788 (3 mg kg−1) did not affect MAP or MCFP following haemorrhage; however, CO was lower, and RSV as well as RV were higher relative to the readings in the haemorrhaged-control rats.

These results show that following compensated haemorrhage, ET maintains arterial resistance and blood pressure via the activation of ETA but not ETB receptors.

Keywords: Endothelin, haemorrhage, mean circulatory filling pressure, cardiac output, venous resistance, body venous tone, endothelin receptor antagonist, FR 139317, BQ-788

Introduction

Endothelins (ETs) are endothelium-derived peptides with potent vasoconstrictor actions in vitro and in vivo. I.v. injection of ET-1, the major ET in the vasculature, causes a transient (<1 min) depressor followed by a prolonged (>1 h) pressor response. The transient depressor response is due to the activation of endothelial ETB receptors that leads to the release of nitric oxide and prostacyclin; the pressor response is due to the activation of both ETA and ETB receptors located on vascular smooth muscle cells (see review by Luscher, 1995). There is evidence that ETB receptors may also mediate sustained vasodilatation. For example, i.v. infusion of BQ-788 (ETB receptor antagonist) into humans caused a sustained increase in total peripheral resistance (Strachan et al., 1999) and vasoconstriction of the forearm (Verhaar et al., 1998). Furthermore, i.v. injection of A-192621 (ETB receptor antagonist) into deoxycorticosterone/salt hypertensive rats increased renal arterial resistance (Matsumura et al., 1999).

Studies in our laboratory have shown that ET-1 is also an efficacious venoconstrictor. I.v. infusion of ET-1 into conscious rats increased mean arterial pressure (MAP) as well as mean circulatory filling pressure (MCFP) (Waite & Pang, 1992), the driving force of venous return (Rothe, 1993; Tabrizchi & Pang, 1992; Pang, 2000). In pentobarbitone-anaesthetized rats, i.v. injection of ET-1 caused a marked increase in venous resistance, and this was via the activation of both ETA- and ETB-receptors (Palacios et al., 1997a, 1997b).

Plasma concentrations of ET-1 are normally low. However, in certain pathophysiological conditions, such as hypovolaemic hypotension, increased circulating levels of ET-1 have been described (Chang et al., 1993; Michida et al., 1994; Vemulapalli et al., 1994; Zimmerman et al., 1994; Kitajima et al., 1995), which raises the possibility that endogenous ET may modulate cardiovascular function in hypovolaemia. Therefore, it is possible that ET may participate in the control of arterial resistance, venous resistance, MAP and MCFP in haemorrhage, and this may be mediated through the activation of ETA and ETB receptors. Since the venous circulation contains approximately 70% of the total blood volume, a change in venomotor tone can drastically alter haemodynamics and MAP.

This study investigated the relative roles of ETA and ETB receptors on haemodynamic compensation following haemorrhage in thiobutabarbitone-anaesthetized rats via administration of the selective ETA-receptor antagonist, FR 139317 ((R)2-[(R)-2-[(S)-2-[[1-(hexahydro-1H-azepinyl)]carbonyl] amino-4-methylpentanoyl] amino-3-[3-(1-methyl-1H-indoyl)] propionyl] amino-3-(2-pyridyl)propionic acid) (Sogabe et al., 1993), and the selective ETB-receptor antagonist, BQ-788 (N-cis-2, 6-dimethylpiperidinocarbonyl-L-γ-methylleucyl-D-1-methoxycarbonyltryptophanyl-D-norleucine) (Ishikawa et al., 1994).

Method

Animal preparation

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (470 – 500 g) were anaesthetized with thiobutabarbitone (Inactin, RBI, MA, U.S.A., 100 mg kg−1, i.p.). The trachea was intubated to facilitate spontaneous breathing. Body temperature was maintained at 36 – 37°C via a rectal thermometer and a heat lamp connected to a Thermistemp Temperature Controller (Model 71; Yellow Springs Instrument Co. Inc., OH, U.S.A.). A polyethylene catheter (PE50) filled with heparinized saline (0.9% NaCl, 25 IU ml−1) was inserted into the left iliac artery for continuous recordings of MAP by a pressure transducer (P23DB, Gould Statham, CA, U.S.A.) and heart rate (HR), which was derived electronically from the upstroke of the arterial pulse pressure by a cardiotachograph (Grass, Model 7P4G). PE50 cannulae were also inserted into the right iliac vein for the administration of vehicle or drugs, and the inferior vena cava via the left iliac vein for the measurement of central venous pressure (CVP) by another pressure transducer (P23DB, Gould Statham). A saline-filled, balloon-tipped catheter was inserted into the right atrium via the right external jugular vein. The correct positioning of the atrial balloon was tested by transiently inflating the balloon, which when correctly placed, induced circulatory arrest within 5 s of inflation. This led to a simultaneous increase of CVP to a plateau value and a decrease of MAP to a final value of 20 – 25 mmHg. MAP, HR and CVP were continuously monitored and recorded by a Grass polygraph (Model RPS, 7C8). Additional cannulae were inserted via the right carotid artery into the left ventricle, for the injection of radioactively-labelled microspheres for the measurement of cardiac output (CO), and into the abdominal aorta through the right iliac artery for the withdrawal of a reference blood sample as described in Wang et al. (1995). The same catheter was also used for withdrawing blood to cause hypovolaemia.

The method for determining MCFP has been described in detail (see Tabrizchi & Pang, 1992; Pang, 2000). Briefly, steady-state readings of MAP and CVP were obtained at 4 – 5 s after circulatory arrest by inflation of the atrial balloon. To avoid the need to rapidly equilibrate arterial and venous pressures during circulatory arrest, the arterial pressure contributed by the small amount of trapped arterial blood was corrected by the following formula: MCFP=VPP+1/60 (FAP - VPP), where FAP and VPP represent, respectively, the final arterial pressure and venous plateau pressure obtained within 5 s of circulatory arrest, and 1/60 represents the ratio of arterial to venous compliance.

Microsphere technique

CO was determined by the microsphere technique. A well-stirred suspension (150 μl) containing 20,000 – 25,000 microspheres (15 μm diameter; Mandel Scientific Company Ltd., Ontario, Canada) labelled with 57Co were injected and flushed over 10 s into the left ventricle. Blood was withdrawn for 1 min at 0.35 ml min−1 from the right iliac arterial cannula into a heparinised syringe (0.9% NaCl, 50 IU ml−1) starting at 10 s before the injection of each set of microspheres using a Harvard infusion/withdrawal pump. The radioactivity contained in the blood samples, syringes used for injection of the microspheres and collection of blood, and test tubes for holding the radio-labelled samples was counted using a 1185 Series Dual Channel Automatic Gamma Counter (Nuclear-Chicago, IL, U.S.A.) with a 3 inch NaI crystal at an energy setting of 80 – 160 keV. The withdrawn blood was slowly injected back to the rats immediately after the counting of radioactivity.

Experimental protocol

Rats were randomly divided into four groups (n=6 each). After 60 min of equilibration, baseline readings of MAP, HR and CO followed by MCFP were obtained. Two groups received the vehicle (distilled water, 0.4 ml kg−1, n=3; or 0.9% NaCl, 0.4 ml kg−1 followed by 0.54 ml h−1 of 0.9% NaCl, n=3), but only one of them was subjected to haemorrhage (17.5 ml kg−1; 1.03 ml min−1) which began after a bolus injection of the vehicle. Another two groups were pretreated with either FR 139317 (1 mg kg−1, 0.4 ml kg−1, i.v. injected over 1 min, followed by continuous infusion at 1 mg kg−1 h−1, 0.54 ml h−1 until the end of the experiment) or BQ-788 (3 mg kg−1, 0.4 ml kg−1, i.v. injected over 3 min) prior to haemorrhage. FR 139317 (1 mg kg−1, i.v.) was shown to maximally inhibit the haemodynamic effects of i.v. bolus ET-1 for at least 1 h (Palacios et al., 1997b). BQ-788 (3 mg kg−1, i.v.) was also shown to completely abolish the effects of the ETB-agonist IRL 1620 on MAP and RA for more than 1 h (Palacios et al., 1998).

Haemodynamics were measured at the end of stabilization (baseline measurements), at 10 min after injection of the vehicle, FR 139317 or BQ 788, and again at 10, 20, 30 and 60 min after the completion of haemorrhage. Haemodynamics were also measured at the same time points in the time-control animals.

Measurement of blood volume

Two additional groups of thiobutabarbitone-anaesthetized rats (n=6 each) were used for the measurement of haematocrit and blood volume using the 51Cr-labelled red blood cell method (Sterling & Gray, 1950). The effect of haemorrhage on blood volume was estimated in two groups of rats because the removal of blood by haemorrhage would not alter the radioactivity of the circulating blood (which would still contain the same proportion of labelled and non-labelled red blood cells). Cannulae were inserted in the left iliac vein and the left and right iliac arteries for the injection of 51Cr-labelled red blood cells, the measurement of MAP and the withdrawal of a reference blood sample, respectively. Red blood cells labelled with 51Cr (0.25 ml) containing approximately 160,000 c.p.m. was i.v. injected into the time-control rats after 30 min of equilibration, and into rats subjected to haemorrhage at 5 min after the end of blood withdrawal. Thereafter, reference blood samples (0.2 ml) were obtained for the measurement of radioactivity, starting at 10, 20, 30 and 60 min after the end of haemorrhage, and at matching times in the time-control group. The radioactivity contained in the blood samples, syringes used for the injection, and test tubes used for holding the radiolabelled samples was counted with a Gamma Counter at energy settings of 271 – 375 keV. The withdrawn blood was i.v. injected back to the animals after the counting of radioactivity. Haematocrit samples were also obtained immediately prior to withdrawal of the reference blood samples.

Drugs

FR 139317 and BQ-788 (Parke-Davis Pharmaceutical Research Div., Ann Arbor, MI, U.S.A.) were dissolved in saline (0.9% NaCl) and distilled water, respectively. All drugs were freshly prepared before each use.

Calculations and statistical analysis

CO (ml min−1), systemic vascular resistance (RSV, mmHg min ml−1) and venous resistance (RV, mmHg min ml−1) were calculated as follows:

|

Due to technical difficulty in monitoring right atrial pressure in small animals, CVP rather than right atrial pressure was used to calculate the pressure gradient to venous return (MCFP – right atrial pressure), as mean CVP is nearly identical to mean right atrial pressure (Rothe, 1993).

The results were expressed as mean±s.e.mean. Baseline haemodynamics (Table 1) and dose-response relationships to drugs or vehicle among the four groups (Figures 1, 2, 3 and 4) were both analysed by two-way repeated measures analysis of variance followed by multiple comparison of group data using Tukey test (SigmaStat statistical software), with P<0.05 selected as the criterion for statistical significance.

Table 1.

Effects (mean±s.e.mean) of vehicle, FR-139317 (1 mg kg−1) and BQ-788 (3 mg kg−1) on mean arterial pressure (MAP, mmHg), heart rate (HR, beats min−1), cardiac output, (CO, ml min−1), systemic vascular resistance (RSV, mmHg min ml−1), venous resistance (Rv mmHg min ml−1) and mean circulatory filling pressure (MCFP, mmHg) in four groups (n=6 each) of thiobutabarbitone-anaesthetized rats.

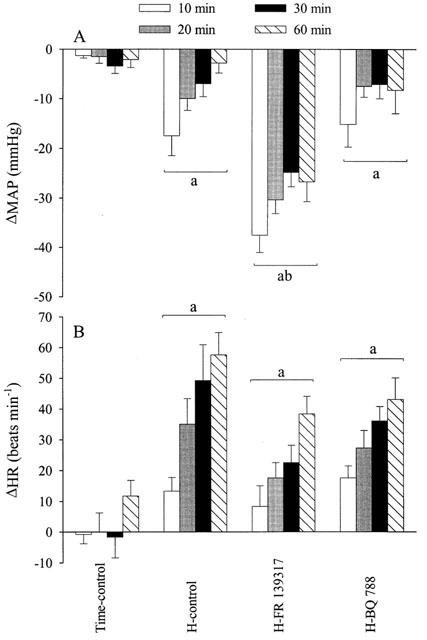

Figure 1.

Effects (mean±s.e.mean) of hypotensive haemorrhage (17.5 ml kg−1) on mean arterial pressure (MAP, A) and heart rate (HR, B) in four groups of thiobutabarbitone-anaesthetized rats (n=6 each) in the presence or absence of FR 139317 (1 mg kg−1, i.v. bolus followed by 1 mg kg−1 h−1) or BQ-788 (3 mg kg−1, i.v. bolus) administered 12 min prior to the start of haemorrhage (H). aSignificantly (P<0.05) different from the time-control group. bSignificantly different from the haemorrhage-control group (H-control).

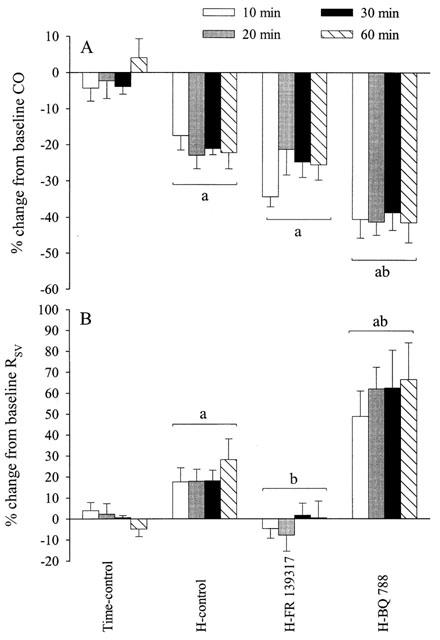

Figure 2.

Effects (mean±s.e.mean) of hypotensive haemorrhage (17.5 ml kg−1) on cardiac output (CO, A) and systemic vascular resistance (RSV, B) in four groups of thiobutabarbitone-anaesthetized rats (n=6 each) in the presence or absence of FR 139317 (1 mg kg−1, i.v. bolus followed by 1 mg kg−1 h−1) or BQ-788 (3 mg kg−1, i.v. bolus) administered 12 min prior to the start of haemorrhage (H). aSignificantly (P<0.05) different from the time-control group. bSignificantly different from the haemorrhage-control group (H-control).

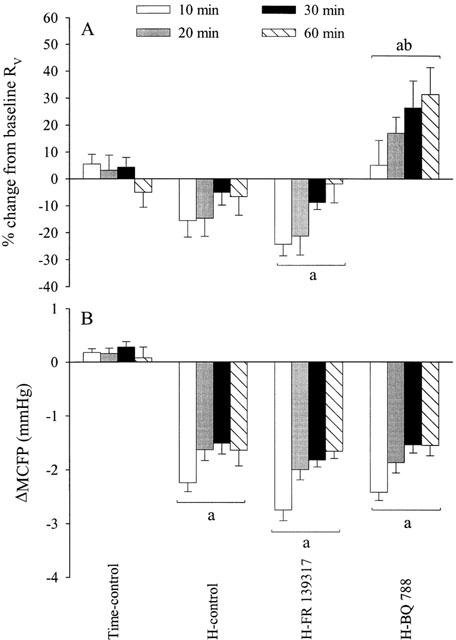

Figure 3.

Effects (mean±s.e.mean) of hypotensive haemorrhage (17.5 ml kg−1) on venous resistance (RV, A) and mean circulatory filling pressure (MCFP, B) in four groups of thiobutabarbitone-anaesthetized rats (n=6 each) in the presence or absence of FR 139317 (1 mg kg−1, i.v. bolus followed by 1 mg kg−1 h−1) or BQ-788 (3 mg kg−1, i.v. bolus) administered 12 min prior to the start of haemorrhage (H). aSignificantly (P<0.05) different from the time-control group. bSignificantly different from the haemorrhage-control group (H-control).

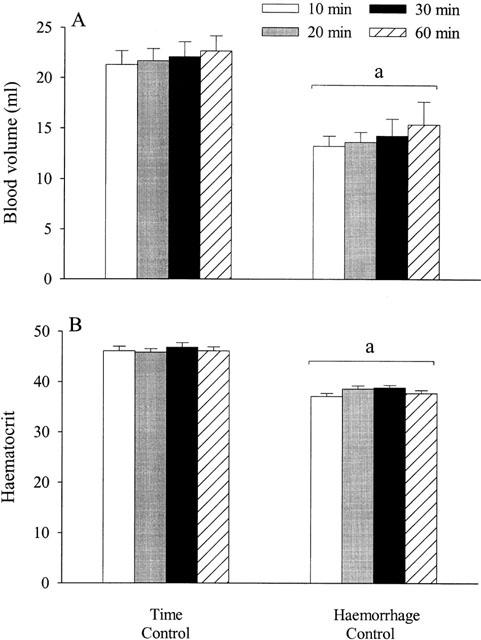

Figure 4.

Effects (mean±s.e.mean) of hypotensive haemorrhage (17.5 ml kg−1) on blood volume (A) and haematocrit (B) in two groups of thiobutabarbitone-anaesthetized rats (n=6 each). aSignificantly different (P<0.05) from the time-control group.

Results

Baseline haemodynamic measurements were not significantly different among the four groups of rats (Table 1). Pre-treatment with vehicle, FR 139317 or BQ-788 did not alter any haemodynamic measurements (Table 1). It should be mentioned that since there were no significant differences in any haemodynamic measurements between the subgroups of time-control rats that received either the distilled water or saline vehicle, data of the two subgroups of vehicles were pooled.

In the time-control group, there was no significant change in any haemodynamic measurements within the duration of the experiments (Figures 1, 2, 3 and 4). Haemorrhage in groups II (vehicle-pre-treatment), III (FR 139317-pretreatment) and IV (BQ-788-pretreatment) progressively reduced MAP, starting at approximately at 3 min after the onset of blood withdrawal to minimum MAP of −49±4, −60±3 and −46±7 mmHg, respectively, at the end of haemorrhage. The decrease in MAP in FR 139317-treated group at this time was greater than that in the haemorrhage-control group, whereas the decrease in MAP in the BQ-788-treated group was similar to that of the haemorrhage-control. After the completion of haemorrhage, MAP in the haemorrhage-control group and BQ-788 group gradually returned toward the baseline (Figure 1a). MAP in the group that received FR 139317, however, was significantly lower than MAP in the haemorrhage-control group, whereas MAP in the BQ-788 group was similar to that of the haemorrhage-control group (Figure 1a). Haemorrhage caused tachycardia in all three groups (Figure 1b).

CO was decreased by haemorrhage in all groups relative to readings in the time-control group. FR 139317 did not affect the haemorrhage-induced decrease in CO while BQ-788 accentuated the decrease in CO (Figure 2a).

RSV was increased in the haemorrhage-control group (Figure 2b). Treatment with FR 139317 abolished the haemorrhage-induced increase in RSV. Treatment with BQ-788, on the other hand, further increased RSV relative to the corresponding readings in the haemorrhage-control group.

In both the haemorrhage-control and the FR 139317-pretreated groups, RV was slightly decreased by haemorrhage; the decrease was insignificant for the control group but significant for the FR 139317-treated group (Figure 3a). In both of these groups, however, RV gradually returned towards baseline with the passage of time. Pretreatment with BQ-788 markedly and progressively increased RV after haemorrhage. MCFP was consistently decreased in the three groups that underwent haemorrhage (Figure 3b).

Blood volume remained the same throughout the experiment in the time-control group (Figure 4a). Blood volume in the haemorrhage-control group was consistently less than that in the time-control group from 10 to 60 min after haemorrhage. Likewise, haematocrit was consistently decreased by haemorrhage (Figure 4b).

Discussion

Total blood volumes in the time control rats and the haemorrhage-control rats at 10 min after the completion of blood loss were estimated by the 51Cr-labelled red blood cell technique. Rats given haemorrhage were found to contain approximately 60% of the blood volume of control rats at 10 – 60 min following the completion of haemorrhage. Associated with the blood loss was a reduction in haematocrit reflecting compensatory net transcapillary fluid absorption that was caused, in part, by the reduction in capillary pressure and increase in plasma osmolarity due to hyperglycaemia (Järhult & Grände, 1975; Larsson et al., 1981). Fluid shifts into the circulation from the interstitium likely occurred soon after haemorrhage, as reflected by the decrease of haematocrit at 10 min after haemorrhage.

In the haemorrhage-control rats, the loss of blood was associated with a sharp decrease of MAP (−49 mmHg) immediately afterwards. At 10 min after haemorrhage, MAP was still significantly decreased (−17 mmHg), but MAP gradually returned to baseline at 60 min after the completion of haemorrhage. Therefore, a large part of the compensatory response, including capillary fluid re-absorption, occurred before the first haemodynamic measurement at 10 min. HR in the time-control rats progressively increased in spite of the eventual restoration of MAP at 30 – 60 min after the completion of haemorrhage. Despite the presence of tachycardia that should have increased CO somewhat, CO remained decreased for the entire period of observation, likely due to sustained hypovolaemia. The gradual restoration of MAP with time was therefore due to the marked and progressive increase in RSV. RV was slightly, though insignificantly, reduced at 10 min after haemorrhage, but it gradually returned towards the baseline level thereafter. Therefore, hypovolaemia in the rats was associated with increased arteriolar but not venular tone. Due to the decrease in blood volume, MCFP remained decreased even at 60 min after haemorrhage. Reduced MCFP following haemorrhage has been reported in chloralose-urethane-anaesthetized dogs (Drees & Rothe, 1974; Rothe & Drees, 1976) and conscious rats (Samar & Coleman, 1979).

The decrease in MAP in the group of rats pretreated with FR 139317 (ETA receptor antagonist) was markedly greater than that in the haemorrhage-control group. Whereas FR 139317 did not affect haemorrhage-induced changes in HR, CO, RV and MCFP, it prevented the increase in RSV at 10 – 60 min following haemorrhage. These results suggest that ETA receptors play a primary role in the maintenance of arterial resistance and MAP following haemorrhage. Zimmerman et al. (1994) reported that pre-treatment of anaesthetized rats (body weights 275 – 403 g) with BQ-123 reduced RSV and exacerbated hypotension at 5 – 20 min, but not at 30 min, following hypotensive haemorrhage (removal of 6-ml of blood per rat within 1 min). It should be noted that the haemorrhage in the Zimmerman et al. (1994) study was more severe than that in the present study, as their haemorrhage-control rats remained hypotensive (−41 mmHg), and RSV was not elevated above baseline at 30 min after haemorrhage, the end of the observation period.

Similar to the haemorrhage-control group, MAP gradually returned towards the baseline in the group pretreated with BQ-788 (ETB receptor antagonist). BQ-788 did not affect haemorrhage-induced changes in HR and MCFP, but exacerbated the reduction in CO. Furthermore, RA and RV were markedly higher in rats pretreated with BQ-788 relative to the readings in the haemorrhage-control rats, and these increases in flow resistances at the arteriolar and venular levels undoubtedly exacerbated the reduction in CO.

Increased pressor response or vasoconstriction to BQ-788 has been reported previously. BQ-788 was shown to potentiate the arterial (Ishikawa et al., 1994; Allcock et al., 1995; Flynn et al., 1995; Sargent et al., 1995; Palacios et al., 1998; Gratton et al., 2000) and venous constrictor effects of ET-1 (Palacios et al., 1998). The ETB receptor antagonist BQ-928 was also shown to potentiate ET-1 induced constriction in the isolated perfused rabbit kidneys (Maurice et al., 1997). There is ample evidence that increased vasoconstriction following the blockade of ETB receptors is likely due to reduced clearance of ET. Indeed, the blockade of ETB receptors has been shown to inhibit pulmonary clearance of ET-1 (Fukuroda et al., 1994; Dupuis et al., 1998), and increase the concentration of ET-1 in the plasma in vivo (Gratton et al., 1997; Willette et al., 1998; Underwood et al., 1999), and in the perfusate of isolated rat lungs (Muramatsu et al., 1997). Furthermore, pressor response to BQ-788 was absent in anaesthetized rabbits pretreated with the ETA receptor antagonist BQ-123 indicating that it was indirectly mediated via the activation of ETA receptors (Gratton et al., 1997). In disagreement with these findings, immunoreactive ET-1 concentration was not increased in ETB-deficient mice; furthermore, BQ-788 increased blood pressure in normal but not ETB-deficient mice, and the increase was inhibited by indomethacin showing the involvement of prostanoids (Ohuchi et al., 1999).

The complex haemodynamic response following haemorrhage involves the activation of different overlapping vasopressor systems that preserve circulatory homeostasis (Schadt & Ludbrook, 1991), e.g., the sympathetic (Chien, 1967; Darlington et al., 1986; Korner et al., 1990; Leskinen et al., 1994), the renin-angiotensin (Freeman et al., 1975; Pang, 1983; Korner et al., 1990; Schadt & Gaddis, 1990) and vasopressin (Zerbe et al., 1982; Hock et al., 1984; Pang, 1983; Johnson et al., 1988; Korner et al., 1990; Imai et al., 1996) systems. ET likely also plays a vital role in haemodynamic compensation following haemorrhage, since plasma concentration of ET-1 is very high following haemorrhage in rats (Michida et al., 1994; Vemulapalli et al., 1994; Zimmerman et al., 1994; Kitajima et al., 1995) and dogs (Chang et al., 1993; Notarius et al., 1995). Furthermore, unlike catecholamines, angiotensin II and vasopressin, ET-1 has a very long duration of vasoconstrictor action that lasts more than 1 h.

Undoubtedly, various vasoconstrictors interact to maintain vascular tone; however, their contributions may vary at different times after haemorrhage (Korner et al., 1990; Schadt & Ludbrook, 1991; Ludbrook & Ventura, 1996). Early in haemorrhage, sympathetic stimulation is responsible for the maintenance of MAP close to the normal level. When blood volume is reduced by 20% or more, vasopressin and angiotensin II become more important than the sympathetic nervous system. The present results further show that ET plays a vital role in the maintenance of arterial resistance following haemorrhage, and this is through the activation of ETA and not ETB receptors. ETA receptors contributed to the maintenance of RSV and ultimately, the restoration of MAP following compensated haemorrhage.

In summary, these results suggest that endogenously released ET has a major vasoconstrictor role in compensated haemorrhage via effects on arterial resistance vessels. The blockade of ETA-receptors leads to marked reductions in MAP and arterial resistance. The blockade of ETB-receptor, on the other hand, leads to sustained constriction of arterial and venous resistance vessels.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Heart & Stroke Foundation of B.C. & Yukon. Beatriz Palacios was a recipient of a postdoctoral fellowship from the Ramón Areces Foundation in Spain. We thank Dr A.M. Doherty (Parke-Davis, U.S.A.) for the generous supply of FR 139317 and BQ 788.

Abbreviations

- CO

cardiac output

- ET

endothelin

- FAP

final arterial pressure

- MAP

mean arterial pressure

- MCFP

mean circulatory filling pressure

- RSV

systemic vascular resistance

- RV

venous resistance

- VPP

venous plateau pressure

References

- ALLCOCK G.H., WARNER T.D., VANE J.R. Roles of endothelin receptors in the regional and systemic vascular responses to ET-1 in anaesthetized ganglion-blocked rat: use of selective antagonists. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;116:2482–2486. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb15099.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHANG H., WU G.-J., WANG S.-M., HUNG C.-R. Plasma endothelin level changes during hemorrhagic shock. J. Trauma. 1993;35:825–833. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199312000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHIEN S. Role of sympathetic nervous system in hemorrhage. Physiol. Rev. 1967;47:215–288. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1967.47.2.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DARLINGTON D.N., SHINSAKO J., DALLMAN M.F. Responses of ACTH, epinephrine, norepinephrine, and cardiovascular system to hemorrhage. Am. J. Physiol. 1986;251:H612–H618. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1986.251.3.H612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DREES J.A., ROTHE C.F. Reflex venoconstriction and capacity vessel pressure-volume relationships in dogs. Circ. Res. 1974;34:360–373. doi: 10.1161/01.res.34.3.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUPUIS J., MOE G.W., CERNACEK P. Reduced pulmonary metabolism of endothelin-1 in canine tachycardia-induced heart failure. Cardiovasc. Res. 1998;39:609–616. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(98)00172-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FLYNN D.A., SARGENT C.A., BRAZDIL R., BROWN T.J., ROACH A.G. Sarafotoxin S6c elicits a non-ETA or non-ETB-mediated pressor response in the pithed rat. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1995;26 Suppl. 3:S219–S221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FREEMAN R.H., DAVIS J.O., JOHNSON J.A., SPIELMAN W.S., ZATZMAN M.L. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1975. pp. 19–22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- FUKURODA T., FUJIKAWA T., OZAKI S., ISHIKAWA K., YANO M., NISHIKIBE M. Clearance of circulating endothelin-1 by ETB receptors in rats. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1994;199:1461–1465. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRATTON J.P., COURNOYER G., LOFFLER B.M., SIROIS P., D'ORLEANS-JUSTE P. ETB receptor and nitric oxide synthase blockade induce BQ-123-sensitive pressor effects in the rabbit. Hypertension. 1997;30:1204–1209. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.30.5.1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRATTON J.P., RAE G.A., BKAILY G., D'ORLEANS-JUSTE P. ETB receptor blockade potentiates the pressor response to big endothelin-1 but not big endothelin-2 in the anesthetized rabbit. Hypertension. 2000;35:726–731. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.3.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOCK C.E., SU J.-Y., LEFER A.M. Role of AVP in maintenance of circulatory homeostasis during hemorrhagic shock. Am. J. Physiol. 1984;246:H174–H179. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1984.246.2.H174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IMAI Y., KIM C.-Y., HASHIMOTO J., MINAMI N., MUNAKATA M., ABE K. Roles of vasopressin in neurocardiogenic responses to hemorrhage in conscious rats. Hypertension. 1996;27:136–143. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.27.1.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ISHIKAWA K., IHARA M., NOGUCHI K., MASE T., MINO N., SAEKI T., FUKURODA T., FUKAMI T., OZAKI S., NAGASE T., NISHIKIBE M., YANO M. Biochemical and pharmacological profile of a potent and selective endothelin B-receptor antagonist, BQ-788. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1994;91:4892–4896. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.4892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JÄRHULT J., GRÄNDE P.-O. Transcapillary fluid movements in sympathectomized intestine and skin during hemorrhagic hypotension. Acta. Physiol. Scand. 1975;94:29–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1975.tb05858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOHNSON J.V., BENNETT G.W., HATTON R. Central and systemic effects of a vasopressin V1 antagonist on MAP recovery after haemorrhage in rats. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1988;12:405–412. doi: 10.1097/00005344-198810000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KITAJIMA T., TANI K., YAMAGUCHI T., KUBOTA Y., OKUHIRA M., MIZUNO T., INOUE K. Role of endogenous endothelin in gastric mucosal injury induced by hemorrhagic shock in rats. Digestion. 1995;56:111–116. doi: 10.1159/000201230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KORNER P.I., OLIVER J.R., ZHU J.L., GIPPS J., HANNEMAN F. Autonomic, hormonal, and local circulatory effects of hemorrhage in conscious rabbits. Am. J. Physiol. 1990;258:H229–H239. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.258.1.H229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LARSSON M., NYLANDER G., ÖHMAN U. Posthemorrhagic changes in plasma water and extracellular fluid volumes in the rat. J. Trauma. 1981;21:870–877. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198110000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LESKINEN H., RUSKOAHO H., HUTTUNEN P., LEPPÄLUOTO J., VUOLTEENAHO O. Hemorrhage effects on plasma ANP, NH2-terminal pro-ANP, and pressor hormones in anesthetized and conscious rats. Am. J. Physiol. 1994;266:R1933–R1943. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1994.266.6.R1933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUDBROOK J., VENTURA S. Roles of carotid baroreceptor and cardiac afferents in hemodynamic responses to acute central hypovolemia. Am. J. Physiol. 1996;270:H1538–H1548. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.270.5.H1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUSCHER T.F. Endothelin and endothelin antagonists: pharmacology and clinical implications. Agents Actions Suppl. 1995;45:237–253. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-7346-8_34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MATSUMURA Y., TAIRA S., KITANO R., HASHIMOTO N., KURO T. Selective antagonism of endothelin ET(A) or ET(B) receptor in renal hemodynamics and function of deoxycorticosterone acetate-salt-induced hypertensive rats. Biol. Pharmaceut. Bull. 1999;22:858–862. doi: 10.1248/bpb.22.858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAURICE M.-C., GRATTON J.-P., D'ORLEANS-JUSTE P. Pharmacology of two novel mixed ETA/ETB receptor antagonists, BQ-928 and 238, in the carotid and pulmonary arteries and the perfused kidney of the rabbit. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;120:319–325. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0700895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MICHIDA T., KAWANO S., MASUDA E., KOBAYASHI I., NISHIMURA Y., TSUJII M., HAYASHI N., TAKEI Y., TSUJI S., NAGANO K., FUSAMOTO H.O., KAMADA T. Role of endothelin 1 in hemorrhagic shock-induced gastric mucosal injury in rats. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:988–993. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90758-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MURAMATSU M., RODMAN D.M., OKA M., MCMURTRY I.F. Endothelin-1 mediates nitro-L-arginine vasoconstriction of hypertensive rat lungs. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;272:L807–L812. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.272.5.L807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NOTARIUS C.F., ERICE F., STEWART D., MAGDER S. Effect of baroreceptor activation and systemic hypotension on plasma endothelin 1 and neuropeptide Y. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1995;73:1136–1143. doi: 10.1139/y95-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OHUCHI T., KUWAKI T., LING G.-Y., DEWIT D., JU K.-H., ONODERA M., CAO W.-H., YANAGISAWA M., KUMADA M. Elevation of blood pressure by genetic and pharmacological disruption of the ETB receptor in mice. Am. J. Physiol. 1999;276:R1071–R1077. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.276.4.R1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PALACIOS B., LIM S.L., PANG C.C.Y. Effects of endothelin-1 on arterial and venous resistances in anaesthetized rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1997a;327:183–188. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)89659-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PALACIOS B., LIM S.L., PANG C.C.Y. Subtypes of endothelin receptors that mediate venous effects of endothelin-1 in anaesthetised rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997b;122:993–998. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PALACIOS B., LIM S.L., PANG C.C.Y. Endothelin ETB receptors counteract venoconstrictor effects of endothelin-1 in anaesthetised rats. Life Sci. 1998;63:1239–1249. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(98)00386-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PANG C.C.Y. Effect of vasopressin antagonist and saralasin on regional blood flow following hemorrhage. Am. J. Physiol. 1983;245:H749–H755. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1983.245.5.H749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PANG C.C.Y. Measurement of body venous tone. J. Pharmacol. Methods. 2000;44:341–361. doi: 10.1016/s1056-8719(00)00124-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROTHE C.F. Mean circulatory filling pressure: its meaning and measurements. J. Appl. Physiol. 1993;74:499–509. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.74.2.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROTHE C.F., DREES J.A. Vascular capacitance and fluid shifts in dogs during prolonged hemorrhagic hypotension. Circ. Res. 1976;38:347–356. doi: 10.1161/01.res.38.5.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMAR R.E., COLEMAN T.G. Whole-body response of the peripheral circulation following hemorrhage in the rat. Am. J. Physiol. 1979;5:H206–H210. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1979.236.2.H206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SARGENT C.A., BRAZDIL R., FLYNN D.A., BROWN T.J., ROACH A.G. Effect of endothelin antagonists with or without BQ 788 on ET-1 responses in pithed rats. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1995;26 Suppl. 3:S216–S128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHADT J.C., GADDIS R.R. Renin-angiotensin system and opioids during acute hemorrhage in conscious rabbits. Am. J. Physiol. 1990;258:R543–R551. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1990.258.2.R543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHADT J.C., LUDBROOK J. Hemodynamic and neurohumoral responses to acute hypovolemia in conscious mammals. Am. J. Physiol. 1991;260:H305–H318. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.260.2.H305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SOGABE K., NIREI H., SHOUBO M., NOMOTO A., AO S., NOTSU Y., ONO T. Pharmacological profile of FR139317, a novel, potent endothelin ETA receptor antagonist. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1993;264:1040–1046. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STERLING K., GRAY S.J. Determination of circulating red cell volume in man by radioactive chromium. J. Clin. Invest. 1950;29:1614–1619. doi: 10.1172/JCI102404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STRACHAN F.E., SPRATT J.C., WILKINSON I.B., JOHNSTON N.R., GRAY G.A., WEBB D.J. Systemic blockade of the endothelin-B receptor increases peripheral vascular resistance in healthy men. Hypertension. 1999;33:581–585. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.33.1.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TABRIZCHI R., PANG C.C.Y. Effects of drugs on body venous tone, as reflected by mean circulatory filling pressure. Cardiovasc. Res. 1992;26:443–448. doi: 10.1093/cvr/26.5.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNDERWOOD D.C., BOCHNOWICZ S., OSBORN R.R., LUTTMANN M.A., LOUDEN C.S., HART T.K., ELLIOTT J.D., HAY D.W.P. Effect of SB 217242 on hypoxia-induced cardiopulmonary changes in the high altitude-sensitive rat. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 1999;12:13–26. doi: 10.1006/pupt.1999.0158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VEMULAPALLI S., CHIU P.J.S., GRISCTI K., BROWN A., KUROWSKI S., SYBERTZ E.J. Phosphoramidon does not inhibit endogenous endothelin-1 release stimulated by hemorrhage, cytokines and hypoxia in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1994;257:95–102. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)90699-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VERHAAR M.C., STRACHAN F.E., NEWBY D.E., CRUDEN N.L., KOOMANS H.A., RABELINK T.J., WEBB D.J. Endothelin-A receptor antagonist-mediated vasodilatation is attenuated by inhibition of nitric oxide synthesis and by endothelin-B receptor blockade. Circulation. 1998;97:752–756. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.8.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WAITE R.P., PANG C.C.Y. The sympathetic nervous system facilitates endothelin-1 effects on venous tone. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1992;260:45–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG Y.X., LIM S.L., PANG C.C.Y. Increase by NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) of resistance to venous return in rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;114:1454–1458. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb13369.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILLETTE R.N., SAUERMELCH C.F., STORER B.L., GUINEY S., LUENGO J.I., XIANG J.N., ELLIOTT J.D., OHLSTEIN E.H. Plasma- and cerebrospinal fluid-immunoreactive endothelin-1: effects of nonpeptide endothelin receptor antagonists with diverse affinity profiles for endothelin-A and endothelin-B receptors. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1998;31 Suppl. 1:S149–S157. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199800001-00044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZERBE R.L., BAYORH M.A., FEUERSTEIN G. Vasopressin: an essential pressor factor for blood pressure recovery following hemorrhage. Peptides. 1982;3:509–514. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(82)90117-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZIMMERMAN R.S., MAYMIND M., BARBEE R.W. Endothelin blockade lowers total peripheral resistance in hemorrhagic shock recovery. Hypertension. 1994;23:205–210. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.23.2.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]