Abstract

Objective

To compare the outcomes and associated morbidity in patients with blunt aortic injury (BAI) repaired using cardiopulmonary bypass versus no bypass. Special consideration is given to the influence of bypass in the outcome of complex injuries or repair circumstances.

Summary Background Data

There are conflicting data concerning the utility of bypass techniques in the operative management of BAI, and controversy over the subject persists. During the last decade, surgeons at the authors’ institution have undergone a change in philosophy concerning management of these injuries and began almost exclusively using cardiopulmonary bypass for the repair in 1996. This project explores the effects of this change in the management of BAI.

Methods

The records of all patients with BAI admitted to a level 1 trauma center over a period of 12 years were reviewed for demographics, injury characteristics, operative technique, and outcome. The bypass group was compared to the no bypass group with respect to morbidity and mortality. Those with a complex injury or repair (CI/R) were examined as a subgroup. CI/R was defined as the presence of an injury with extension proximal to the subclavian artery, involvement of branch vessels, or requirement of maneuvers interfering with anastomosis construction, such as cardiac massage.

Results

From January 1, 1990, to December 31, 2001, 91 patients were admitted to Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center with BAI. Sixty-five of these underwent operative repair. Sixty (32 no bypass, 28 bypass) survived to the immediate postoperative period. Injury Severity Score was similar (33 no bypass, 31 bypass, P = .48), as was admission base deficit (−9.2 m Eq/L no bypass vs. −7.0 mEq/L B, P = .13). Paraplegia occurred in four (12%) of the no bypass group as opposed to 0 of the bypass group (P = .05). No patient in the bypass group experienced complications related to heparinization, and two (7%) experienced bypass-related complications (cerebral edema, femoral vein laceration). Mean clamp time for the entire group was 27 minutes. Examination of the 10 patients with CI/R who survived the operating room showed markedly longer clamp times (59 minutes vs. 22 minutes, P < .0001) and a higher rate of paraplegia/paresis (30% vs. 2%, P = .01) as compared to those without CI/R. Logistic regression demonstrated a significant relationship between increasing clamp time and the CI/R classification (P = .007). All three (100%) of the CI/R patients repaired via clamp-and-sew technique developed paraplegia, while none of the seven CI/R patients repaired on bypass developed neurologic changes (P = .008).

Conclusions

With the use of cardiopulmonary bypass in the repair of BAI, the incidence of paraplegia/paresis has fallen. While patients with typical injuries and uncomplicated repair can expect good results with either technique, cardiopulmonary bypass provides significant advantages in the repair of those with CI/R. With the use of bypass, no CI/R patient developed paraplegia, while all CI/R patients experienced paraplegia before bypass use. Although others have reported the importance of clamp time, in this series clamp time appeared largely to be a surrogate variable for complexity of injury.

Blunt aortic injury (BAI) is a highly lethal injury, with the majority of victims dying at the accident scene. In addition, it is the second only to brain injury as the most common cause of death in blunt trauma victims. 1 Despite its lethality, patients surviving the initial injury with a rupture contained by the mediastinum and pleura are seen at larger trauma centers on a regular basis. In the 42 years since surgical repair was first described, 2 great strides have been made in the management of this injury, and successful repair is now the norm. However, one of the most feared complications in operative survivors remains paraplegia. This is believed to stem from spinal cord ischemia due to a number of reasons, and prolonged aortic cross-clamp times have been implicated in the development of paraplegia. 3–6 BAI ranges from a simple tear, usually distal to the origin of the subclavian artery, to complex variations of the injury involving the proximal aorta and branch vessels. These more complex injuries may require a different management scheme than the more typical injuries, 7 and the relationship of complex injuries to prolonged clamp times and the incidence of paraplegia warrants close examination.

Many have reported the use of bypass techniques in surgical repair to allow for distal spinal cord perfusion and have demonstrated a significant reduction in paraplegia with such techniques. 5,6,8–11 While it appears clear that the use of bypass has a beneficial effect on paraplegia rate, controversy exists over its exact role in the repair of BAI. 12,13

The goal of the current study was to examine the utility of cardiopulmonary bypass in the repair of BAI, with emphasis on its effect on operative course and outcome in the case of patients with more complex injury or repair scenarios.

METHODS

Patient Population

The registry of our level 1 trauma center was queried for all patients admitted with BAI over a 12-year period. The records were carefully reviewed for demographics, admission hemodynamics, injury characteristics, and associated injuries. Details of operative repair (if performed) and outcome were also examined. Patients were classified as complex injury or repair (CI/R) in the case of an injury with extension proximal to the subclavian artery, involvement of branch vessels, or requirement of maneuvers interfering with anastomosis construction, such as cardiac massage.

Diagnosis

Before 1999, patients with abnormalities on chest radiograph suggestive of BAI underwent angiography of the aorta. Such abnormalities included widened mediastinum, indistinct aortic knob, “pleural cap” indicating extrapleural hematoma, or significant deviation of the nasogastric tube to the right of the patient. After 1999, helical computed tomography (CT) of the chest became the most common method of aortic evaluation in the face of mediastinal abnormalities on plain film. For the purposes of this project, radiographic studies were reviewed and interpreted by a staff radiologist, and the data reflect this interpretation.

Injury Management

All injuries were managed by trauma or cardiothoracic surgery staff in conjunction with residents. On diagnosis, blood pressure management was instituted in most cases. A variety of agents were used, but the large majority of patients in the latter years of the study were treated with esmolol, with the addition of nitroprusside as needed. Before 1996, most injuries were repaired with a “clamp-and-sew” technique, whereas subsequent injuries have been repaired with the use of partial cardiopulmonary bypass and full heparinization. Deep hypothermic circulatory arrest was used in selected cases as needed. All operations were carried out shortly after admission, with the exception of those in patients with severe brain injury, in whom bypass was planned. Operative intervention was delayed in this case to allow an interval to pass that would make systemic heparinization safe.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Statview 5.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Dichotomous variables were compared using the chi-square or Fisher exact test where appropriate. The relationship between cross-clamp time and CI/R was examined using logistic regression and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. The area under the ROC curve is bounded by 0.50 and 1; better discriminating scores have more area under the curve than poorer discriminating scores. The area under the ROC curve may alternatively be thought of as the probability that a randomly chosen CI/R patient will have a longer clamp time than an uncomplicated patient. Significance was defined as P ≤ .05.

RESULTS

General Population

From January 1, 1990, to December 31, 2001, 91 patients with BAI were admitted to Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center. The mean age of this group was 46 ± 22 years, Injury Severity Score was 35 ± 13, admission systolic blood pressure and base deficit were 116 ± 29 mmHg and −7.4 ± 6.8 mEq/L, and the overall mortality was 44% (40 patients). Of the original 91, 20 were in extremis on arrival, and none of these patients survived. The remaining 71 survived past initial evaluation, and the majority of these patients had severe concomitant injuries (21% brain injury, 38% intra-abdominal injury, and 14% long bone fracture). Sixty-five of these 71 patients underwent attempted operative repair, with 60 survivors (92%). Mean aortic cross-clamp time in the patients undergoing operation was 27 ± 18 minutes. Overall incidence of paraplegia in survivors was 6.7%. 4 Of these 60, 16 (27%) underwent primary repair and 44 (73%) required placement of a prosthetic graft. Two underwent planned nonoperative management, one due to minimal nature of injury and one due to the prohibitive risk of mortality with attempted repair. The remaining four died (three from exsanguination) before operation.

Injury Types

The anatomic distribution of injuries in patients undergoing operation was similar to that described by other authors: the majority (55 [85%]) were just distal to the subclavian artery, and the remaining 10 had injuries involving the more proximal extent of the aorta and its branches. The CI/R group comprised these 10 patients and included 1 additional patient whose repair was complicated by the need for cardiac massage during construction of the anastomosis. Table 1 describes the injuries and outcomes in these 11 patients, 10 of whom survived the operation for repair.

Table 1. PATIENTS IN THE COMPLEX INJURY/REPAIR GROUP

Diagnostic Methods

In the 71 patients who did not arrive in extremis, conventional angiography was the most common method of definitive diagnosis; it was used in 42 (59%). This was followed by computed tomography (CT) in 22 patients (31%) and transesophageal echocardiography in 4 (6%). Two additional injuries were diagnosed at emergent thoracotomy, and one was diagnosed on autopsy after in-house rupture. While arteriography still plays an important role in diagnosis and operative planning, CT has become the most common method of initial diagnosis as the technology has improved. From 1990 to 1998, only 4 of 46 injuries (9%) were diagnosed with CT, compared to 18 of 25 (72%) in 1999 to 2001.

In the 10 patients in the CI/R group due to type of injury, the unusual nature of the injury was diagnosed on preoperative angiography in only 4 patients (40%). Four patients also had chest CT, with only one (25%) being suggestive of a more complex injury.

In the 71 patients stable at admission, findings on chest radiography that prompted further diagnostic measures included widened mediastinum alone (n = 50), indistinct aortic knob alone (n = 2), widened mediastinum and apical cap (n = 5), widened mediastinum and indistinct aortic knob (n = 5), and a combination of widened mediastinum, indistinct aortic knob, and apical cap (n = 3). Six (8.4%) had a normal plain chest radiograph on admission.

Repair and Outcome

Bypass Versus No Bypass

Operative survivors were evenly split between those repaired without cardiopulmonary bypass (n = 32) and those repaired on bypass (n = 28). The large majority of the bypass group was seen subsequent to January 1996, with only 2 of 27 (7%) repairs occurring with the use of cardiopulmonary bypass in 1990 to 1995 and 26 of 33 (79%) during 1996 to 2001. Average time on cardiopulmonary bypass for the bypass group was 70 ± 55 minutes. Six of these 28 patients also underwent deep hypothermic circulatory arrest (average time 27 ± 13 minutes). Table 2 shows a comparison of the characteristics and outcome in the no bypass and bypass groups. While the bypass group was older, each group had similar injury severity, shock on admission, and aortic cross-clamp time. Despite these similarities, paraplegia was more common in the no bypass group. In addition, there was a trend toward greater transfusion requirement in this group. Postoperative pneumonia rates, ICU length of stay, and overall mortality did not differ between the two groups. The use of bypass appeared to allow for better control of hypothermia. In patients with preoperative hypothermia (<36°C), those in the bypass group had a higher postoperative temperature than those in the no bypass group (36.4°C vs. 35.3°C, P = .007).

Table 2. CHARACTERISTICS AND OUTCOMES IN PATIENTS REPAIRED WITH AND WITHOUT CARDIOPULMONARY BYPASS

BD, admission base deficit.

Despite heparinization during cardiopulmonary bypass, there were no associated bleeding complications. Planned nonoperative management of two grade II liver injuries and one grade III and one grade II spleen injury was successful in the face of anticoagulation. Another patient with a grade II splenic injury underwent laparotomy following bypass because of concern for splenic bleeding, but none was found. There were two (7%) complications attributable to use of bypass: femoral vein laceration requiring repair, and an episode of cerebral edema.

Paraplegia Versus No Paraplegia

To determine factors that might be associated with risk of paraplegia during repair of BAI, comparison was made between those surviving repair with and without paralysis (Table 3). While injury severity and admission hemodynamics were similar, aortic cross-clamp time was markedly longer in the group sustaining postoperative paraplegia. This is paired with the fact that those with paraplegia were significantly more likely to fall into the CI/R group.

Table 3. DEMOGRAPHICS, INJURY AND REPAIR CHARACTERISTICS, AND OUTCOME IN PATIENTS WITH AND WITHOUT PARAPLEGIA

BD, admission base deficit; CI/R, complex injury or repair.

CI/R: Relationship to Clamp Time and Paraplegia

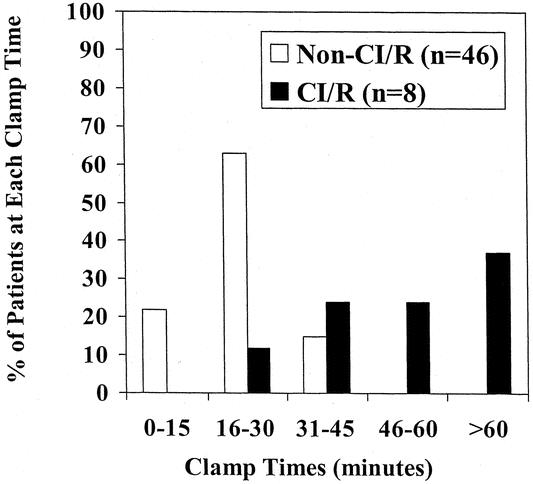

Due to the high incidence of CI/R patients and longer clamp times in the group with paraplegia, the relationship between CI/R and clamp time was explored (Fig. 1). This shows that the longest clamp times were uniformly seen in CI/R patients. Mean clamp times were longer in the CI/R group (59 minutes) compared to the non-CI/R group (22 minutes, P < .0001), and logistic regression demonstrated a significant relationship between increasing clamp time and the CI/R classification (P = .007). If clamp times more than 30 minutes are examined, 7 of the 8 (87%) CI/R patients with clamp times available required cross-clamp for more than 30 minutes, while only 7 of the 46 (15%) non-CI/R patients with times available needed more than 30 minutes for repair (P = .0001). An area under the curve of 0.92 was found on ROC curve analysis for the ability of clamp time to identify CI/R patients (that is, a longer clamp time will discriminate between CI/R and non-CI/R patients correctly 92% of the time). Thus, it appears that in this series longer clamp times may be seen as a surrogate for the complexity of injury or repair. CI/R was also associated with higher rates of paraplegia, with only one case (2%) occurring in the non-CI/R group and three (30%) occurring in the CI/R group (P = .01).

Figure 1. Distribution of clamp times* in complex injury/repair (CI/R) patients and non-CI/R patients. Includes those not repaired using deep hypothermic circulatory arrest without cross-clamp.

Given this relationship, CI/R patients in the bypass and no bypass groups who survived operation were compared to determine the effect of the use of bypass on the incidence of paraplegia in the CI/R subset. Indeed, all three (100%) of the CI/R patients repaired via clamp-and-sew technique developed paraplegia, while none of the seven CI/R patients repaired on bypass developed neurologic changes (P = .008).

Free rupture into the thoracic cavity occurred in six patients after admission to the hospital, and all patients subsequently died. Although this complication was uncommon, reduced risk for in-house rupture appeared to be related to control of blood pressure. None of the 6 patients sustaining in-house rupture received medication for blood pressure control, while 54 of the 65 (83%) without in-house rupture were treated with antihypertensives (P = .0001). Esmolol with or without nitroprusside was used in the majority (74%), while the remaining 26% received nitroprusside alone, nitrates alone, or a combination of these agents. Although blood pressure control appears to be protective, delay of repair for greater than 48 hours after admission is not routinely done and occurred in only one patient in the series, who had a severe brain injury.

DISCUSSION

BAI is a significant and lethal problem after blunt trauma, led only by traumatic brain injury as the most common cause of death in such accidents. 1 Those who survive the immediate injury, however, may have excellent outcomes with optimal management. In those who survive operative repair, paraplegia remains a significant problem, affecting as many as 10% to 20% of such patients. 4,5,12 While the factors leading to paraplegia are incompletely understood, prolonged aortic cross-clamp times with spinal cord ischemia during repair are clearly related to its development. Bypass techniques that provide distal aortic perfusion may help prevent cord ischemia, and several authors have demonstrated the possible utility of these techniques in the prevention of paraplegia during repair of BAI. 5,6,8–11 Others have argued that bypass with distal perfusion is unnecessary.

These data show that while clamp time is indeed related to paraplegia rate, prolonged clamp times are largely a surrogate for the more direct variable of complexity of the injury or repair. In addition, although a modest reduction in paraplegia rate was seen in the overall population with bypass use, the protective effect of such measures in the CI/R population is striking. No CI/R patient experienced paraplegia with bypass use, while all CI/R patients repaired without bypass were rendered paraplegic.

Longer clamp times with relative distal cord ischemia have been implicated by several authors as a significant risk factor for paraplegia. The largest series supporting this was the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) multicenter trial on BAI, in which prolonged clamp times were strongly associated with subsequent paraplegia. The AAST data as well as others have shown that significantly higher rates of neurologic dysfunction are seen with times greater than 30 to 35 minutes. 3–6,14 This relationship between clamp time and cord injury is important. Some have voiced concern, however, that the mark of 30 to 35 minutes should not be viewed as a standard to which surgeons should be held, but that longer clamp times may simply be indicative of more severe injury or difficulty with repair. 15 These data support the concept that longer times are indeed a marker of injury severity, with a tight relationship between clamp time and CI/R.

The use of some type of bypass technique to allow for distal perfusion of the spinal cord has been advocated by many surgeons experienced in the care of BAI patients. Passive conduits such as the Gott shunt are no longer widely employed, but other techniques are common. In 1989, Wallenhaupt et al., in a review of 18 patients, noted that “shunting procedures during repair of descending aortic disruption appear to offer some protection from neurological deficits.”16 Since than, several larger series have demonstrated significantly lower rates of paraplegia using bypass. In the recent AAST trial, 65% of patients were repaired using some type of bypass technique, and again this trial found bypass use to be associated with lower rates of paraplegia. 6

This concept has not been universally embraced, however, and this has remained a point of controversy in recent years. 12,13 These data serve to reinforce the concept that paraplegia rates are lower in BAI patients repaired on bypass. Most striking, however, was the apparent utility of bypass in the CI/R group. All patients in the CI/R group repaired using the “clamp-and-sew” technique experienced neurologic sequelae; no CI/R patient repaired on bypass did so. Thus, while bypass may offer advantages in the repair of the aorta in the overall BAI population, its major benefit with respect to spinal cord protection will be seen in the patients with complex injuries or repair scenarios. Hunt et al. in 1996 found bypass to be protective against paraplegia in patients with clamp times longer than 35 minutes. 5 Since prolonged clamp times are so closely associated with complexity of injury, these data appear to strongly support this earlier work.

In addition to providing spinal cord protection, bypass has other potential advantages. First is the ability to easily control blood pressure without the use of medicines. Both afterload and preload can be adjusted with the heart-lung machine to optimize hemodynamics. This will reduce the workload of the heart, which is especially important in elderly patients. In addition, a temporary decrease in aortic pressure allows for accurate manual assessment for the presence and configuration of atherosclerotic plaques, and thus more accurate selection of clamp location. Distal perfusion during aortic cross-clamping with cardiopulmonary bypass gives adequate flow rates to the mesenteric organs as well as the spinal cord. This lessens ischemia/reperfusion injury, and work is ongoing in the examination of pharmacologic adjuncts to be used during distal perfusion that may further improve the postischemic functioning of these organs. 17,18 Blood salvage advantages with cardiopulmonary bypass include not only red blood cell conservation, which is seen with cell savers when bypass is not used, but also reinfusion of all blood products, including plasma and platelets. Temperature control is a vital part of the use of cardiopulmonary bypass in repairing BAI. One can allow the temperature to drift to 35°C during clamping and repair, which decreases oxygen requirements to ischemic areas. In complex aortic injury, one may drop temperatures down to 20°C to 22°C, allowing turning off of the circulation and exsanguinating the patient into the heart-lung machine. The inside of the aorta can then be carefully and completely examined, allowing optimal repair under ideal conditions. The patient may also be warmed with the bypass heater-cooler to normothermia, which allows better clotting function.

The disadvantages of cardiopulmonary bypass often cited include the need for cannula placement and heparin use. Soft, flexible cannulas in recent years have made this easier than in the past. The most common sites for cannulation include the femoral artery and femoral vein in the groin, which can be exposed before turning the patient for left thoracotomy. Frequently, we use pulmonary artery cannulation for venous return and descending aortic cannulation for inflow when the patient is on the side and the left chest is open. Bleeding complications with the use of heparin are unusual. Heparin is easily reversible with protamine, and further improvements in clotting may be seen because of the ability, in using bypass, to salvage whole blood, with its included coagulation factors.

As cited, large amounts of data point to the importance of shorter clamp times and the use of bypass in avoiding paraplegia. While these reports represent an inarguable contribution to the goal of improving patient care and outcomes, the exact mechanism of paraplegia in the face of these injuries is likely multifactorial and remains incompletely understood. Paraplegia still occurs, albeit infrequently, with shorter clamp times and with the use of bypass. 19 Thus, continued investigation into the pathophysiology and prevention of neurologic dysfunction in the face of BAI is essential.

Since patients with complex injuries appear to be a high-risk population, early identification of such patients would assist in preoperative planning and management. Current angiographic techniques clearly cannot provide such information reliably, with only 40% of the CI/R group being identified as such on angiogram. CT also did not perform well in identification of these injuries, with only one of four being diagnosed correctly on CT. While these data do not support the ability of CT in the accurate anatomic diagnosis of CI/R injuries, this must be interpreted with caution. CT was applied inconsistently over the earlier part of the review, and techniques and technology have evolved considerably in recent years. As technology such as multi-slice CT scanning continues to develop and mature, improvement in image quality may allow for excellent preoperative planning based on CT alone.

Although CT may not currently be adequate for all preoperative planning, it is routinely used as a diagnostic modality, and the increase in diagnosis by CT in the latter part of this study reflects this trend. Scanning of the chest in high-risk patients who are already undergoing abdominal/pelvis CT adds only minimal time and contrast exposure. With today’s technology, CT has a sensitivity similar to angiography. 20 With CT screening, many unnecessary trips to angiography with critically ill patients may be avoided.

The issue of heparinization during bypass in the multi-trauma patient has been raised as a cause for concern by some authors. In the current series, however, no complications related to anticoagulation occurred in the 28 patients managed with bypass and full anticoagulation. This population included five patients undergoing nonoperative management of solid organ injuries. This is similar to the experience reported by the Memphis group in which none of 20 patients with grade I-II spleen or liver injuries failed nonoperative management after heparinization for BAI repair. 21 It would seem prudent to avoid acute heparinization in patients with severe brain injuries or ongoing bleeding, but it does appear safe in most blunt trauma victims.

The natural history of untreated BAI is rupture in the majority of cases. This was outlined in the well-known report by Parmley et al. in 1958 in which 90% of BAI patients surviving the initial injury experienced intrathoracic rupture and death by 10 weeks. 22 These data support the concept that this history may be altered by the use of antihypertensive therapy, with no patient who received antihypertensive therapy undergoing in-house rupture, while none of the six patients who did rupture after admission had control of their blood pressure. This supports the findings of previous investigators who have described the advantages of blood pressure control in the BAI population. 23,24 The concept was examined by Fabian et al. in 1998; they reported that early diagnosis with antihypertensive therapy eliminated in-house rupture in their population. 20 These findings do not imply, however, that the repair of BAI can be conveniently fitted into the week’s elective schedule, and planned delay should be done only in circumstances that might make attempted repair more dangerous, such as severe brain injury or hypoperfusion from other reasons.

There is increasing interest in the idea that some patients with BAI may actually heal and not require surgery. One patient in the current data set with minimal BAI underwent planned nonoperative management with apparent success. No follow-up studies were available for documentation of healing, however. There is a growing body of evidence that observation may be safe in some circumstances, 25 and this population certainly warrants further study. Optimal criteria for patients who may be safely observed have yet to be well defined, and the large majority of patients will likely benefit from aggressive operative intervention.

In the repair of BAI, paraplegia remains a significant concern. These data demonstrate that in the hands of surgeons experienced in the management of this injury, prolonged clamp times with the attendant rise in paraplegia rate are dictated by the complexity of the injury or repair. Thus, the incidence of paraplegia is largely predicted by the injury itself, if no bypass is used. Cardiopulmonary bypass is an important tool in the management of the general BAI population, with improved core temperature control as shown here, as well as options for blood salvage, clamp placement, and circulatory arrest if needed. Despite these advantages, the impact of bypass use on the course of most patients with typical BAI may not be clinically obvious. In patients with complex injuries, however, its impact becomes clear, and in the studied population it was associated with a marked reduction of paraplegia. In fact, no CI/R patient in the current series repaired with the use of bypass experienced neurologic dysfunction despite prolonged aortic cross-clamping. Data describing the ability of current imaging technology to identify the more complex subset are not currently available, so bypass cannot always be selectively applied to this group. In addition, cardiopulmonary bypass in the trauma population has a favorable safety profile. For these reasons, bypass remains an important adjunct in BAI repair to be considered in all such patients.

Discussion

Dr. Timothy C. Fabian (Memphis, TN): I would like to congratulate the authors on a nice contribution to the important issue of management of blunt aortic injuries.

As you observed at the end of their presentation, the authors stated that cross-clamp time is a surrogate for complex repairs, while complex repairs were defined as those basically where the anatomy involved the arch in the injury. I want to return to that issue at the end of this discussion. But what is implied is that in simple repairs, the clamp-and-sew techniques really are appropriate and would be preferred.

The authors confirmed several important issues I think that have been discussed over the last five years and added data to help us in making management decisions. First, that heparin can, in fact, be safe even in patients with multiple injuries. They had no significant adverse outcomes associated with complete heparinization. Secondly, they also noted in the manuscript that antihypertension therapy significantly reduced prehospital rupture in their series, perhaps one of the more important issues that needs to be widely adopted to prevent preoperative death in these patients. And finally their biggest point was that bypass is clearly associated with lower paraplegia rates.

I would like the authors to comment on a few things. Dr. Miller, you had a half-dozen patients who had hypothermic arrest as part of operative management. Could you tell us a little about those? Is this an alternative to bypass in complex patients, perhaps?

Also, in recent years, atrial-femoral bypass has been the technique associated with the lowest paraplegia rate in the literature. It is very appealing, since it eliminates the need for total heparinization with the 60,000 to 80,000 units required for partial bypass. Do you have any thoughts on that? We have used it in Memphis sporadically, but I think it probably is the wave of the future.

Finally, when patients were stratified for clamp-and-sew versus bypass, they appeared to be quite similar. The only difference was the complex repairs had longer cross-clamp times. What I would suggest is, it is not the complex repairs that are causing the paraplegia, but clearly the mechanism is prolonged ischemia of the spinal cord associated with long cross-clamp times, similar to the epiphenomenal circumstance that was referred to earlier by Dr. Thompson in discussing Dr. Fong’s paper. The issue really is ischemia. So I would suggest the cross-clamp time is not a surrogate for complex repairs, but, on the contrary, the complex repairs are surrogates for long cross-clamp times.

As a more practical matter, however, until complex repairs can be predicted preoperatively with advanced CT or other means of diagnosis, bypass techniques with distal aortic perfusion should become the standard based on an abundance of available evidence, including this excellent report given today.

Dr. John A. Morris, Jr. (Nashville, TN): Drs. Miller and Meredith present a series of 71 patients with blunt aortic injury who survived to be admitted to a single academic medical center over an 11-year period. Sixty-five patients underwent operative repair and 60 survived. Of the 60 survivors, 28 underwent cardiac bypass and 32 had no bypass. The overall incidence of paraplegia was 6.7%, which is low, and all paraplegic patients were in the non-bypass group. Ten patients had complex injury repair, and these patients had longer clamp time and a higher incidence of paraplegia than those without complex injury.

The strengths of this paper include the fact that it is from a single well-established trauma program with an acceptable study size and apparently consistent philosophy of repair over the 11-year study period. Its weaknesses include the study design: it is a case series, not a randomized trial, although I doubt that we could get a randomized trial like this through our IRBs, and the fact that they are studying a rare outcome, paraplegia, in a very rare event aortic transection.

I have several questions. First, were there any adjunctive therapies used in this population of patients to prevent paraplegia—steroids, mannitol, or thiopental? Second, will you speculate on why preoperative imaging technologies failed to identify complex anatomy in 60% of cases? And, third, are there any grades of solid organ injury or head injury that you would consider to be a contraindication to heparinization and consequently to bypass?

Finally, I would like to emphasize that while this report has no incidence of paraplegia in the bypass group, it is not appropriate to conclude that the use of bypass eliminates the risk of paraplegia. I believe that bypass lowers the risk but does not eliminate it.

Dr. Lynn H. Harrison, Jr. (New Orleans, LA): I would like to go back to a question raised by Dr. Fabian regarding the choice of venoarterial bypass over left atrial to distal aortic or femoral artery bypass. The latter has obvious attractive advantages in that if a heparin-bonded circuit is used, there is no need for additional heparin. This seems to be important, although it did not appear to be a major factor in your series. It certainly is attractive in these patients who frequently have multiple solid organ injuries in the abdomen.

In addition, by avoiding conventional bypass using an oxygenator, when used as a heparin-bonded or other biocompatible circuit, it may avoid the systemic inflammatory response, which is associated with conventional bypass. Why did you choose the venoarterial route rather than left atrial to distal aortic or femoral artery route?

Dr. Preston R. Miller (Winston-Salem, NC): The aim of this project was to review our experience with blunt aortic injury with specific emphasis on those with more complex injuries and look at their outcome. And I think these data suggest that more complex injuries are associated with higher clamp time. In fact, a higher clamp time is really just a surrogate marker for the complexity of injury. In addition, although there are probably benefits in a lot of aortic injury patients from routine bypass, the greatest benefits look like they are going to be seen in those with more complex injuries, with a markedly lower paraplegia rate.

In reference to Dr. Fabian’s comments and questions. You asked about the clamp time and the complexity of injury and which was a marker for the other. And I think your point is a good one, and that is that certainly very few patients have been paralyzed from the complexity of injury, and it does require the cross-clamp time and the ensuing ischemia to the spinal cord. But I think these data suggest that in experienced hands that the clamp time and the complexity of injury are almost indistinguishable as variables.

With respect to the hypothermic arrest, I think it is a useful technique in a situation where either you are able to preoperatively determine whether there is a more complex injury that can only be repaired successfully this way, or if in the middle of a repair it becomes clear that this is going to be used or would be helpful to be used. I think this speaks to Dr. Harrison’s question, too. This is a technique that allows you more options. With respect to atrial femoral as opposed to the bypass technique used here, again, it is a matter of expanding your options with temperature control, oxygenation, blood salvage, that type of thing.

In discussing Dr. Morris’s questions specifically, solid organ or brain injury in which we would not use heparin. These data and some data from Memphis and others have suggested that despite a lot of concerns over heparinization in significant blunt trauma patients, it is really not a big problem if you use it carefully. Certainly, there is nothing to argue that it is safe to heparinize patients with higher-grade solid organ injuries or severe head injury. I think there are two options in those patients. One is, there is increasing data that those patients can be delayed with appropriate blood pressure control. That is what we currently do. And I think these data point to another possibility. If improving imaging can predict which of these patients are complex and which are not complex, it may be that you can, if the patient is otherwise ready to go, perform a clamp-and-sew type repair without heparin in a patient like this. So there may be other options.

Dr. Morris, you asked about the imaging technology and was there some reason it was not very good at diagnosing these complex injuries. If you look at the imaging used, it is a longitudinal study, and the majority early on were imaged using angiography. And these data, I think, in conjunction with some others, demonstrate that although angiography is good at diagnosing the injury, it may not be very good at giving you a very consistent road map. And as we have begun to use CT and the CT technology is improving, it is the gestalt of our surgeons that very good imaging given by the current CT technology really does give a good road map and gives a much better idea as to whether these injuries are likely to be the standard, the run-of-the-mill distal to the subclavian injury versus some more complex type injury.

As far as adjunctive treatment, we don’t use any of that. We don’t use steroids or drainage of CSF. But certainly that is an ongoing area of research, and I think it is important. Certain substances that may be used in bypass may allow for even further spinal cord protection.

And that gets me to the last point that you made, Dr. Morrison, and I think it is a very important one. Clamp time is important. Complexity of injury is a marker of longer clamp time. And the use of bypass certainly helps. But it has been pretty well shown that none of these completely eliminate the risk of paraplegia. There are other problems that we need to address. There is certainly ongoing research in that, which is important and needs to continue.

References

- 1.Smith RS, Chang FC. Traumatic rupture of the aorta: still a lethal injury. Am J Surg. 1986; 152: 660–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Passaro E, Pace WB. Traumatic rupture or the aorta. Surgery. 1959; 46: 787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee RB, Stahkman GC, Sharp KW. Treatment priorities in patients with traumatic rupture of the thoracic aorta. Am Surg. 1992; 58: 37–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cowley RA, Turney SZ, Hankins JR. Rupture of the thoracic aorta caused by blunt trauma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1990; 100: 652–660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hunt JP, Baker CC, Lentz CW, et al. Thoracic aorta injuries: management and outcome of 144 patients. J Trauma. 1996; 40: 547–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fabian TC, Richardson JD, Croce MA, et al. Prospective study of blunt aortic injury: multicenter trial of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma. J Trauma. 1997; 42: 374–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carter Y, Meissner M, Bulger E, et al. Anatomical considerations in the surgical management of blunt thoracic aortic injury. J Vasc Surg. 2001; 34: 628–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pate JW, Fabian TC, Walker WA. Acute traumatic rupture of the aortic isthmus: repair with cardiopulmonary bypass. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995; 59: 90–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forbes AD, Ashbaugh DG. Mechanical circulatory support during repair of thoracic aortic injuries improves morbidity and prevents spinal cord injury. Arch Surg. 1994; 129: 494–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jamieson WRE, Janusz MT, Gudas VM, et al. Traumatic rupture of the thoracic aorta: third decade of experience. Am J Surg. 2002; 183: 571–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Downing SW, Cardarelli MG, Sperling J, et al. Heparinless partial cardiopulmonary bypass for the repair of aortic trauma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000; 120: 1104–1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hilgenberg AD, Logan DL, Akins CW, et al. Blunt injuries of the thoracic aorta. Ann Thorac Surg. 1992; 53: 233–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kwon CC, Gill IS, Fallon WF, et al. Delayed operative intervention in the management of traumatic descending thoracic aortic rupture. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002; 74: S1888–1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katz NM, Blackstone EH, Kirklin JW, et al. Incremental risk factors for spinal cord injury following operation for acute traumatic aortic transection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 81:669–674. [PubMed]

- 15.Mattox KL. Fact and fiction about management of aortic transaction. Ann Thorac Surg. 1989; 48: 1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wallenhaupt SL, Hudspeth AS, Mills SA, et al. Current treatment of traumatic aortic disruptions. Am Surg. 1989; 55: 316–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parrino PE, Kron IL, Ross SD, et al. Spinal cord protection during aortic cross-clamping using retrograde venous perfusion. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999; 67: 1589–1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gangemi JJ, Kern JA, Ross SD, et al. Retrograde perfusion with a sodium channel antagonist provides ischemic spinal cord protection. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000; 69: 1744–1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wall MJ Jr, Hirshberg A, LeMaire SA, et al. Thoracic aortic and thoracic vascular injuries. Surg Clin North Am. 2001; 81: 1375–1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fabian TC, Davis KA, Gavant ML, et al. Prospective study of blunt aortic injury: helical CT is diagnostic and antihypertensive therapy reduces rupture. Ann Surg. 1998; 227: 666–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Santaniello JM, Miller PR, Croce MA, et al. Blunt aortic injury with concomitant intra-abdominal solid organ injury: treatment priorities revisited. J Trauma. 2002; 53: 442–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parmley LF, Mattingly TW, Manion TW, et al. Nonpenetrating traumatic injury of the aorta. Circulation. 1958; 17: 1086–1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akins CW, Buckley MJ, Dagget W, et al. Acute traumatic disruption of the thoracic aorta: a 10-year experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 1981; 31: 305–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maggisano R, Nathens A, Alexandrova NA, et al. Traumatic rupture of the thoracic aorta: should one always operate immediately? Ann Vasc Surg. 1995; 9: 44–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malhotra AK, Fabian TC, Croce MA, et al. Minimal aortic injury: a lesion associated with advancing diagnostic techniques. J Trauma. 2001; 51: 1042–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Footnotes

Presented at the 114th Annual Session of the Southern Surgical Association, December 1–4, 2002, Palm Beach, Florida.

Correspondence: Preston R. Miller, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Surgery, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Medical Center Blvd., Winston-Salem, NC 27514.

E-mail: pmiller@wfubmc.edu

Accepted for publication December 2002.