Abstract

Purpose

Although there are many controversial reports about the effect of p53 and p21WAF1/CIP1 overexpression in different human tumor cells, the p53 gene is shown to be a more effective candidate for cancer gene therapy because of its more pronounced ability to induce apoptosis. In the present study, we present the effect of p53 and p21WAF1/CIP1 overexpression on mouse renal carcinoma cells in vitro and in vivo.

Methods

p53 and p21WAF1/CIP1 genes were introduced into Renca cells using adenoviral vectors (Ad5CMV-p53 and Ad5CMV-p21). The induction of apoptosis was measured using Annexin V assay and DNA fragmentation analysis. The expression of proteins was examined using immunocytochemistry and Western blot methods. The ability of adenoviral vectors to inhibit tumorigenicity of Renca cells, as well as the growth of pre-established tumors was measured.

Results

In vitro growth assays revealed higher growth suppression after Ad5CMV-p21 infection. Although both vectors induced apoptosis, Ad5CMV-p53 was slightly more efficient. In vivo studies in Balb/c mice, demonstrated that tumorigenicity was completely suppressed by Ad5CMV-p21. Besides this, Ad5CMV-p21 significantly inhibited the growth of established tumors, while Ad5CMV-p53 did not.

Conclusions

These data suggest that p21WAF1/CIP1 is a more potent growth suppressor than p53 of mouse tumor cells Renca. The divergent responses of tumor cells to p21WAF1/CIP1 overexpression could be due to various networks that differ between species.

Keywords: p53, p21WAF1/CIP1, Gene therapy, Apoptosis, Renca cells

Introduction

Significant information has accumulated to suggest that overexpression of oncogenes and/or inactivation of cell cycle regulators (especially tumor suppressor genes) is responsible for the tumor growth. Developing gene therapy strategies in which defective or abnormal copies of genes in tumor cells are inactivated or supplemented with genes that can slow down tumor growth provide, therefore, an attractive strategy to cancer treatment (Roth and Cristiano 1997). The p53 tumor suppressor gene is one of the most commonly mutated genes in human cancer (Hollstein et al. 1996). It plays a critical role in mediating cell cycle arrest and apoptosis following exposure to stress stimuli (Stewart and Pietenpol 2001; Vousden 2000). Mutations of p53 affect its ability to suppress tumorigenesis and have been associated with unfavorable prognosis in a variety of tumor types and often with enhanced resistance to many anti-tumor agents (Wallace-Brodeur and Lowe 1999; Gallagher and Brown 1999). Numerous studies have confirmed that reintroduction of wt p53 suppresses tumor cell growth, induces apoptosis, and/or increases sensitivity to conventional antitumor agents (reviewed by Nielsen and Maneval 1998).

On the other hand, cell cycle progression is controlled by the cyclin-dependent protein kinases (Cdks), which are catalytic partners of the cyclins. Because of their central regulatory roles in cell proliferation, Cdks themselves are subject to many modes and levels of regulation, such as cyclins availability, protein degradation, dephosphorylation or inhibitory phosphorylation and binding to Cdk inhibitory proteins (CKIs) (Ekholm and Reed 2000; Gartel et al. 1996; Sherr 1996). p21WAF1/CIP1 was the first identified CKI. It was isolated as a mediator of p53-induced growth arrest (El-Deiry et al. 1993), an inhibitor of Cdk activity (Harper et al. 1993), and as a gene that is overexpressed in senescent fibroblasts (Noda et al. 1994). Different studies have shown that p21 could also act as a tumor suppressor in vitro and in vivo (Sheikh et al. 1995; Ramondetta et al. 2000; Katayose et al. 1995; Joshi et al. 1998; Cardinali et al. 1998; Shibata et al. 2001; Kralj et al. 2003). Although several studies demonstrate that exogenous expression of p21 in human tumor cells correlates with apoptosis (Sheikh et al. 1995; Ramondetta et al. 2000; Tsao et al. 1999), the others demonstrate only growth inhibition and more transient effects of p21 expression (Katayose et al. 1995; Joshi et al. 1998; Cardinali et al. 1998). Moreover, when comparing the effects of exogenous expression of p53 and p21 in human cells, it seems that p53 may be more effective candidate for cancer gene therapy than p21, although p53 overexpression always results in increased p21 expression (Ramondetta et al. 2000; Parker et al. 2000; Gotoh et al. 1997; Clayman et al. 1996). However, there are several reports that demonstrate that p21 transgene in mouse or hamster cells either induces apoptosis, or sensitizes cells to DNA-damaging agents-induced apoptosis (Shibata et al. 2001; Fotedar et al. 1999; Hingorani et al. 2000; Duttaroy et al. 1997; Sekiguchi and Hunter 1998). Besides this, when p53 and p21 genes were introduced into mouse prostate cancer cells, p21 was much more effective for growth inhibition in vitro and in vivo than p53 (Eastham et al. 1995). In addition, introduction of p21 with adenoviral vectors into mouse renal carcinoma cells, completely suppressed their growth in vivo and also resulted in striking reduction of growth of established pre-existing tumors (Yang et al. 1995). It seems that these differences could be explained by species differences, but additional studies regarding the role of p53 and p21 genes in murine cells are needed. The objective of this study is to compare the efficacy of the exogenous wt p53 gene expression with that of p21 gene on growth inhibition and induction of apoptosis in mouse renal carcinoma cell line (Renca) in vitro, as well as on tumor growth in vivo.

Materials and methods

Cell lines

Murine tumor cells

B16Bl6 (melanoma) and Renca (renal carcinoma) cell lines were cultured in RPMI-1640 (Institute of Immunology, Croatia) supplemented with 10% heat inactivated FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin.

Recombinant adenoviral vectors

Recombinant adenoviral vectors Ad5CMV-p53 and Ad5CMV-p21 (Introgen Therapeutics, USA) contained the CMV promoter, wild-type human p53 and p21 cDNA, SV 40 polyadenylation signal in a minigene cassette inserted into the E1-deleted region of modified Ad5, as described earlier (Zhang et al. 1994). As a control vector dl 312 was used. Viral vectors were propagated and titrated in 293 cells. Cells were harvested 36–40 h after infection, pelleted, resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline, and lysed; cell debris was removed by subjecting the cells to CsCl gradient purification. Concentrated virus was dialyzed, aliquoted, and stored at −80 °C.

Cell growth assay in vitro

The cells were plated at a density of 1×104 cells/ml in 24-well plates 24 h before viral infection. Infection was carried out by adding the virus to the cell monolayers in 200 μl RPMI-1640 and 2% FBS. The cells were incubated at 37 °C for 60 min. Then complete medium (RPMI-1640 and 10% FBS) was added and the cells were incubated for the desired length of time. Cells were harvested every 2 days and counted manually; their viability was determined by trypan blue exclusion. The cell growth was expressed as a percentage of viable infected cells, in relation to the number of viable control (uninfected) cells, which was expressed as 100%. The cell growth inhibition was also measured using MTT assay (Sigma). The plates were analyzed on a LabSystems Multiscan MS plate reader (Finland) at a wavelength of 570 nm.

Immunocytochemistry

The cells were plated at a density of 5×104 cells/well onto 8-well plastic slides (Nunc, USA) and infected with Ad5CMV-p53, Ad5CMV-p21 or mock-infected (control cells). Twenty-four hours after infection, the cells were washed with PBS and fixed in methanol with 3% hydrogen peroxide (Kemika, Croatia). Applying normal rabbit serum (1:10 in PBS) for 30 min at room temperature blocked non-specific binding. Primary mouse monoclonal antibodies anti-human and mouse p53 (Ab-3, Oncogene, USA), anti-human p53 (Ab-2, Oncogene), and anti-human p21 (Pharmingen, USA), in a concentration of 5 μg/ml, were allowed to bind overnight at 4 °C. After washing the slides in PBS, secondary antibody (rabbit anti-mouse, DAKO, Denmark) was applied for 1 h at room temperature. Finally, the slides were stained with 0.0025% diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (Sigma) containing 4% H2O2 for 7 min and counterstained with hematoxylin for 30 s. The slides were analyzed with a light microscope (Olympus, BH-2). The level of nonspecific background staining was established for each measurement using cells processed in the same way but without exposure to the primary antibody.

Western blotting

Twenty-four hours after infection, total cell lysates were prepared in lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.2 mM EGTA, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100) with protease inhibitors, and 20 μg of protein were separated by electrophoresis on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels. The proteins were transferred to polyvinyl-fluoride membrane (Millipore, USA) and the membranes were blocked with 0.05% Nonidet P40 and 3% milk. The membranes were probed with primary antibodies: polyclonal rabbit anti-mouse p21 antibody (Pharmingen, in a concentration of 1:1,000) and monoclonal mouse anti-human and mouse p53 antibody (Ab-3, Oncogene, in a concentration of 2.5 μg/ml). Secondary antibodies were horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse, or anti-rabbit antibodies (Amersham, USA, in a concentration of 1:5,000 and 1:6,000, respectively). The membranes were developed using chemiluminescence technique according to the manufacturer's directions (Roche, Germany). Densitometric calculations of the intensity of bands corresponding to specific proteins were performed using Image Master VDS (Pharmacia Biotech).

Detection of apoptosis

Annexin V test

Detection and quantification of apoptotic and differentiation from necrotic cells at single cell level was performed using Annexin-V-FLUOS staining kit (Roche), according to the manufacturer's recommendations. After the desired length of time, both floating and attached cells were collected. The cells were then washed with PBS, pelleted, and resuspended in staining-solution [annexin-V-fluorescein labeling reagent and propidium iodide (PI) in Hepes buffer]. The cells were then analyzed under a fluorescence microscope. Annexin-V (green fluorescent) cells were determined to be apoptotic and Annexin-V and PI cells were determined to be necrotic. Percentage of apoptotic cells was expressed as a number of fluorescent cells in relation to the total cell number (fluorescent and non-fluorescent cells), which was expressed as 100%.

Nucleosomal DNA fragmentation analysis

Apoptotic DNA fragments were isolated according to the method described by Herrmann and coworkers (Herrmann et al. 1994). Briefly, cells were plated at 106 in 10-ml plates and infected. Twenty-four hours after infection, attached and floating cells were harvested, washed with PBS, and pelleted by centrifugation. The cell pellets were then treated for 10 s with lysis buffer (1% NP-40 in 20 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5). After centrifugation for 5 min at 1600×g the supernatant was collected and the extraction was repeated with the same amount of lysis buffer. The supernatants were brought to 1% SDS and treated for 2 h with RNAse A (final concentration 5 mg/ml) at 56 °C followed by digestion with proteinase K (final concentration 2.5 mg/ml) for 2 h at 37 °C. After addition of 1/2 vol. 10 M ammonium acetate, the DNA was precipitated with 2.5 vol. ethanol, dissolved in TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl and 1 mM EDTA), and separated by electrophoresis in 1% agarose gels.

Animal studies

Eight-week-old female mice of the Balb/c strain were used. Mice were bred in the animal facility of the Rudjer Boskovic Institute. Food and tap water were given ad libitum. Experiments on animals were carried out in accordance with Croatian Law on the Protection of Animals and the Principles of Laboratory Animal Care established by the NIH.

Tumorigenicity study

Renca cells were infected either with Ad5CMV-p53, Ad5CMV-p21, dl 312 at a MOI 100 or mock infected. Four hours after the infection the cells were washed and resuspended in PBS. The cells were inoculated (5×105 cells/0.1 ml PBS) subcutaneously into the right hind leg. The animals were divided into four groups: one implanted with Ad5CMV-p53-infected cells, one implanted with Ad5CMV-p21-infected cells, one implanted with dl 312-infected cells, and one implanted with mock-infected cells. All four groups comprised six animals. The presence of tumor and tumor volume were evaluated.

Tumor growth inhibition study

Tumors were generated by subcutaneous injection of 5×105 cells/0.1 ml into the right hind leg. The treatment of tumors (intratumoral injections) started when the tumors were 30–50 mm3. The animals were divided into two groups (I and II) comprised of four subgroups. Group I was treated with a single dose (5×108 PFU) of Ad5CMV-p53, Ad5CMV-p21, dl 312, or PBS (subgroups). Group II was treated with five doses of either vectors (108 PFU per dose) or PBS, which were given on five consecutive days, so that the total dose received was the same as in group I. Every subgroup comprised six animals. The tumors were measured with calipers in two perpendicular diameters. Tumor volume was calculated by assuming a spherical shape with the average tumor diameter calculated as the square root of the product of cross-sectional diameters. Tumor volumes were calculated using the formula 4/3πr3 where r is the radius of the tumor.

Statistical analysis

One-way ANOVA was used to test the significance of the differences between the samples using Microcal Origin, Microcal Software, USA.

Results

Effect of Ad5CMV-p53 and Ad5CMV-p21 on cell growth

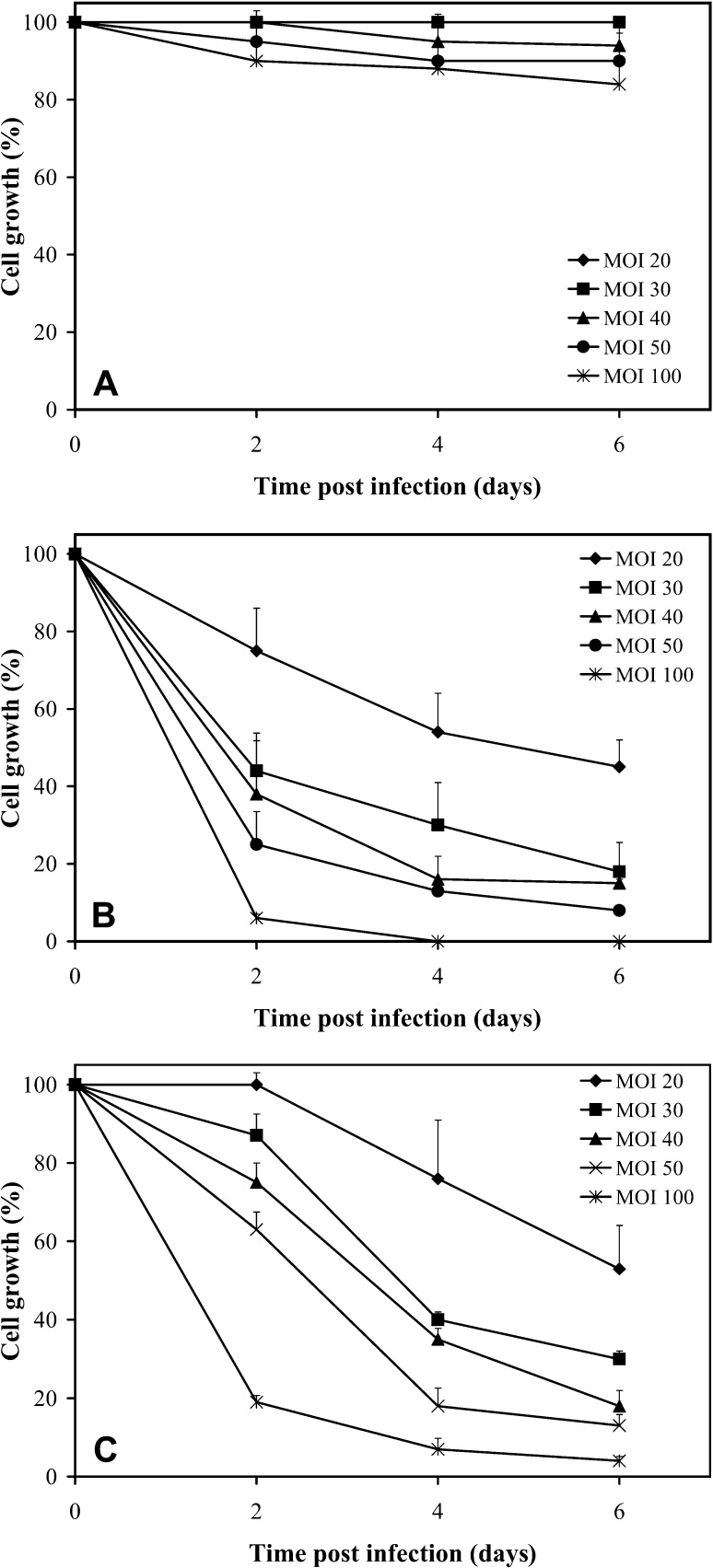

We investigated the effect of exogenous wild-type p53 and p21 expression on the growth of two murine tumor cell lines (Renca, B16Bl6). As the growth inhibitory effects were more pronounced on Renca cells, we focused our experiments on this cell line. Renca cells infected with the control vector had growth rates similar to control (uninfected) cells (Fig. 1A). Adenoviral vectors Ad5CMV-p53 and Ad5CMV-p21 strongly inhibited the growth of Renca cells in a time- and dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1B and C). The growth inhibition induced by Ad5CMV-p21 vector was more pronounced than by Ad5CMV-p53, although this difference was statistically significant only the second day after infection (P<0.02). For example, Ad5CMV-p53 at MOI 20 did not inhibit the growth of Renca cells 2 days after infection, whereas Ad5CMV-p21 inhibited the growth for 25%. A similar difference was noticed at other MOIs. Ad5CMV-p21 at MOI 100 completely suppressed the growth of Renca cells over the 4-day period, while Ad5CMV-p53 did not. The cell growth inhibition was also measured using MTT assay and the obtained results regarding the differences between Ad5CMV-p53 and Ad5CMV-p21-infected cells were similar (data not shown).

Fig. 1A-C.

Time- and dose-response curves obtained after infection of Renca cells with A dl 312, B Ad5CMV-p21, and C Ad5CMV-p53 at different MOI values ranging from 20 PFU/cell to 100 PFU/cell. Cells were plated in triplicates on 24-well plates and the growth was determined by counting the cell numbers at different time points after infection. Results represent means±SD. The experiment was repeated three times, and the results were similar

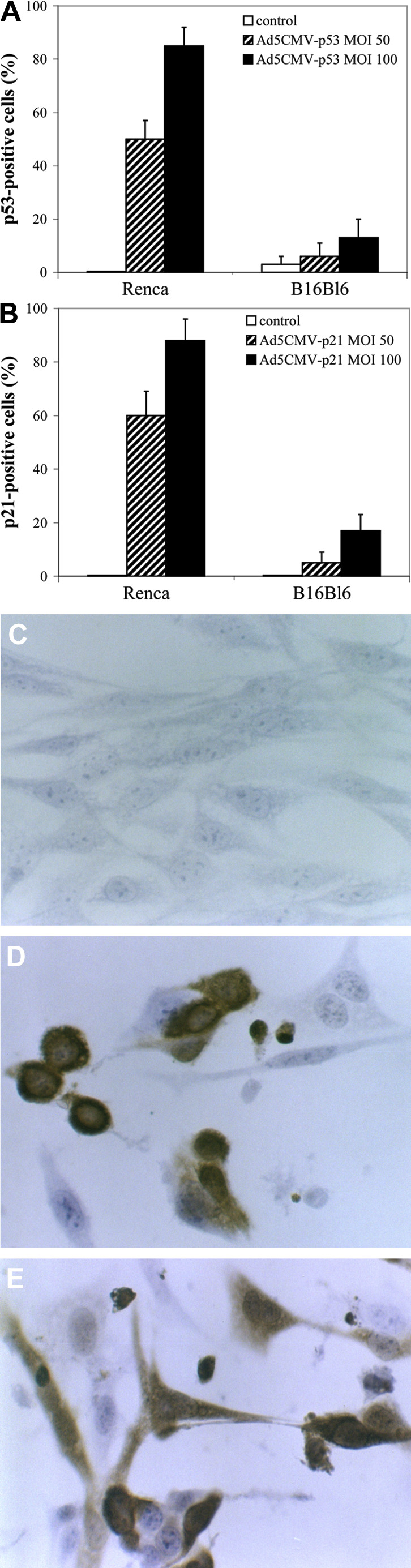

p53 and p21 protein expression following Ad5CMV-p53 and Ad5CMV-p21 infection

To determine the levels of expression of p53 and p21 proteins in control and infected cells, 24 h after infection, both immunocytochemistry and Western blot analysis were used. The results confirmed increased p53 and p21 expression after infection with Ad5CMV-p53 and Ad5CMV-p21, respectively, (Fig. 2A and B) and characteristic nuclear staining of both proteins, when infected at lower MOIs, as well as nuclear and cytoplasmic staining at higher MOIs (Fig. 2D and E and data not shown). The percentage of p53-positive cells after infection with Ad5CMV-p53 and p21-positive cells after infection with Ad5CMV-p21, at the same MOI, was almost identical (Fig. 2A and B). Since the exogenous proteins are of human origin, the difference between endogenous and exogenous proteins was easily discernable by using specific antibodies that recognize human protein. Besides, no endogenous p53 protein in Renca cells was detected in control cells. Moreover, the percentage of p53- and p21-positive cells increased with the MOI of virus, e.g., after infection with MOI 50 there was about 50% positive cells, and after infection with MOI 100, about 80%. This confirms that Renca cells are efficiently transfected with both adenoviral vectors and that the exogenous proteins are efficiently expressed. On the contrary, B16Bl6 cells were not efficiently transfected since there were strikingly less p53- or p21-positive B16Bl6 cells, at the same MOIs, which is in accordance with less effective growth inhibition detected on this cell line (data not shown). However, a certain basal level of endogenous p53 protein was detected in B16Bl6 cells (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2A-E.

Immunocytochemical analysis of p53 and p21 protein expression in Renca and B16Bl6 cells. The cells were infected with Ad5CMV-p53 and Ad5CMV-p21 at MOIs 50 and 100 and compared to uninfected cells. Antibodies towards human and mouse p53 protein and towards human p21 protein were used. Percentages of A p53- and B p21-positive cells and immunocytochemical staining of C Renca control, D Ad5CMV-p53-infected and E Ad5CMV-p21-infected cells are shown

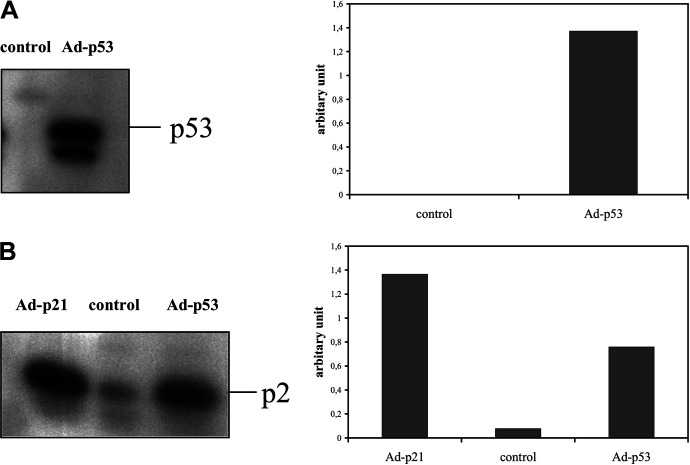

Western blot analysis of p53 expression confirmed increased expression of p53, in Ad5CMV-p53 infected cells, whereas control cells lacked detectable protein (Fig. 3A). On the other hand, basal levels of mouse p21 protein were detectable in control cells (Fig. 3B, lane 2). Besides this, p21 protein level after infection with Ad5CMV-p53 was about tenfold higher than in control cells (Fig. 3B, lane 3), which confirmed the ability of exogenous (virus-expressed) human p53 to activate transcription of endogenous (mouse) p21. However, the expression level of p21 protein obtained after infection with Ad5CMV-p21 is up to twofold higher than in Ad5CMV-p53-infected cells (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3A,B.

Western blot analysis of A p53 and B p21 protein expression in Renca cells. The cells were infected with Ad5CMV-p53 or Ad5CMV-p21 at a MOI 100. After 24 h, cell lysates were prepared and subjected to Western blot analysis using monoclonal antibody towards human and mouse p53 protein and polyclonal p21 antibody towards mouse p21 protein. The right half of each panel represents the densitometric analysis of the bands

Induction of apoptosis

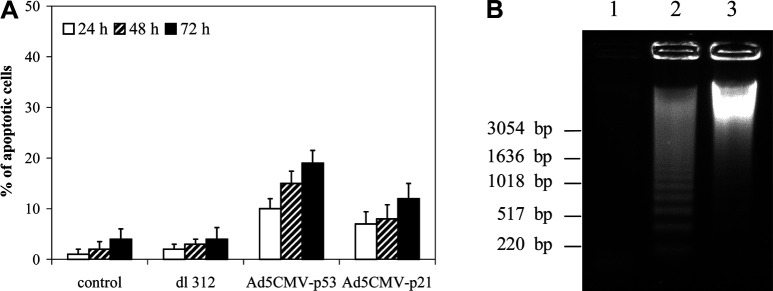

To determine whether the overexpression of exogenous p53 and p21 genes induces apoptosis in Renca cells, Annexin V assay was performed 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h after viral infection at the MOI 100. The results from one of three repeated experiments show that the both vectors induced apoptosis in Renca cells (Fig. 4A). However, Ad5CMV-p53 was slightly more efficient (e.g., 15% Annexin V positive cells 48 h after Ad5CMV-p53 infection, at MOI 100 compared with 8% positive cells after Ad5CMV-p21 infection). There was no statistical difference in the percentage of Annexin V positive cells infected with both vectors at MOI 50 and 100 (data not shown).

Fig. 4A,B. A.

Percentage of apoptotic cells. The cells were mock infected or infected with dl 312, Ad5CMV-p53, and Ad5CMV-p21 at a MOI 100 and examined after different time points using Annexin V assay. Results represent means±SD. B Nucleosomal DNA fragmentation in Renca cells. Low-molecular-weight DNA was isolated 24 h after infection with Ad5CMV-p53 and Ad5CMV-p21 at a MOI 100. Lane 1 DNA from control cells; Lane 2 DNA from cells infected with Ad5CMV-p53; Lane 3 DNA from cells infected with Ad5CMV-p21

The induction of apoptosis was confirmed by detection of DNA fragmentation 24 h after infection with either vector at MOI 100 (Fig. 4B). As expected, stronger fragmentation was observed after Ad5CMV-p53 infection.

In vivo effect of Ad5CMV-p53 and Ad5CMV-p21

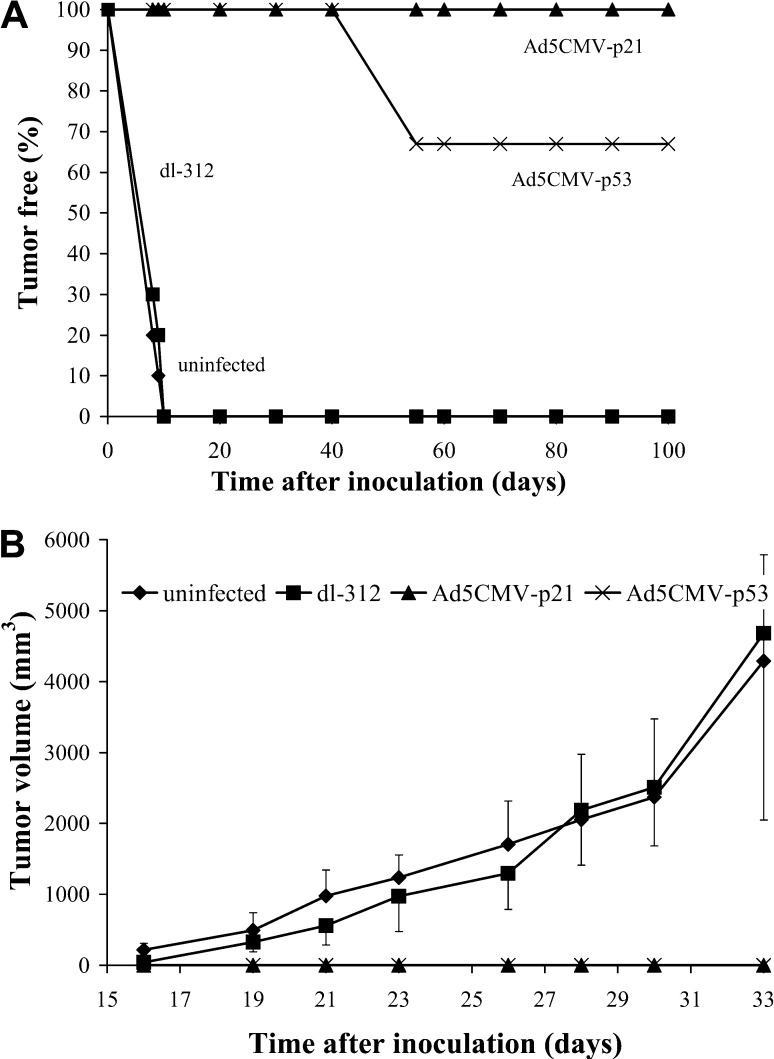

To examine whether the p53 or p21 overexpression can inhibit tumorigenicity of malignant cells, Renca cells were infected with Ad5CMV-p53, Ad5CMV-p21, dl-312 or mock infected and inoculated into recipient animals. Incidence of tumor formation (Fig. 5A) and tumor volumes (Fig. 5B) were observed throughout a period of 100 days. The tumor formation started at day 8 post-injection only in animals that received control vector- or mock infected cells. These animals were killed on day 33 (Fig. 5B). On the other hand, mice that received Ad5CMV-p21 infected cells did not develop tumors during a 100-day period. However, at day 55, in two out of six animals (33%) that were injected with Ad5CMV-p53 infected cells, tumors started to develop and were growing continuously thereafter.

Fig. 5A,B.

Inhibition of tumor formation. Renca cells were exposed to MOI 100 of Ad5CMV-p53, Ad5CMV-p21 and dl 312, or mock-infected and inoculated (5×105 cells/0.1 ml PBS) into recipient animals. The A presence of tumor and B tumor volume are shown. Results represent means±SD

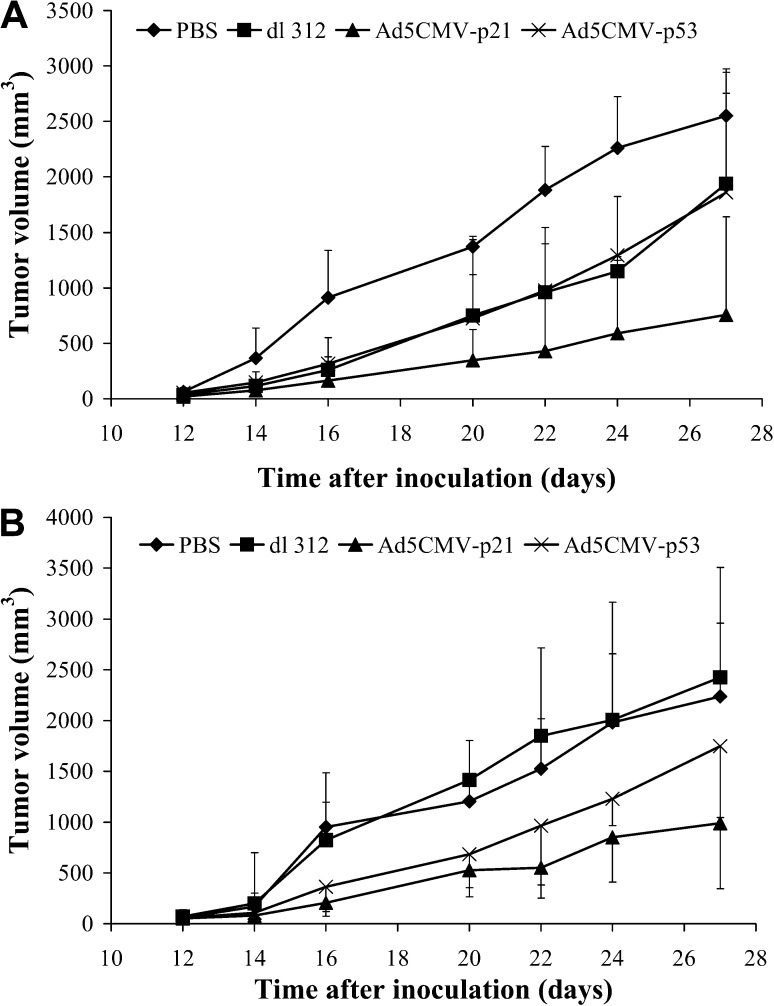

The ability of adenoviral vectors to inhibit the growth of pre-established tumors was examined by intratumoral single or repeating injections into established s.c. tumor nodules (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6A,B.

Inhibition of tumor growth. Renca cells (5×105 cells/0.1 ml PBS) were injected into Balb/c mice and tumors formed. Effect of A a single intratumoral injection of 5×108 PFU or B five consecutive injections of 1×108 PFU of Ad5CMV-p53, Ad5CMV-p21, dl 312 or PBS is shown (n=6). Results represent means±SD

Treatment with a single injection of 5×108 PFU of Ad5CMV-p21 significantly inhibited tumor growth during 27 days after inoculation (P<0.05) (Fig. 6A). By day 27 the average tumor size measured in this group, was 758±881 mm3, compared with 2553±423 mm3 in control group. Surprisingly, Ad5CMV-p53 and control vector (dl-312) similarly inhibited tumor growth; however, this inhibition was not statistically significant, compared to control group (P>0.05).

In the group of animals that received repeated injections for five consecutive days, Ad5CMV-p21 vector was again more efficient than Ad5CMV-p53 (Fig. 6B). In this study, the control vector did not show any inhibitory effect on tumor growth, while Ad5CMV-p53 slightly inhibited tumor growth, but this inhibition was statistically significant compared to the control group only on day 16. None of the animals in both studies was tumor-free at the end of the experiment.

Discussion

The ultimate goal of basic research on the molecular basis of cancer and cell cycle regulation is to develop better diagnostic and prognostic tools and new treatment strategies as alternative or adjuvant to conventional radiation and chemotherapy. Although tumor development involves numerous genetic alterations, in almost all instances deregulated cell proliferation and suppressed cell death play a critical role in the progression of the disease (Evan and Vousden 2001). Many of these alterations could be used as targets for cancer therapy; however, inactivation of oncogenes and replacement of tumor suppressor genes are the most interesting and effective methods (Roth and Cristiano 1997).

The ability of a certain gene to induce apoptosis is considered to be an important factor for cancer gene therapy. Since the p53 gene plays a critical role in both regulation of cell cycle and apoptosis, reintroduction of this gene into tumor cells is challenging strategy for cancer treatment. This idea was confirmed by numerous studies that demonstrated suppression of tumor cell growth and/or induction of apoptosis by p53 gene (Gallagher and Brown 1999; Nielsen and Maneval 1998).

Cyclin kinases inhibitors (CKI) represent another class of tumor suppressor genes that function as cell-cycle regulators by controlling the activity of cyclin-dependent kinases. This suggests that CKI could also be good candidates for cancer gene therapy.

The precise molecular mechanism controlling p53- or p21-induced apoptosis is not quite clear. There are many controversial reports about the effect of p53 and p21 overexpression in different tumor cells, regarding growth suppression and the induction of apoptosis. The general conclusion from these studies is that the p53 gene could be a more effective candidate for cancer gene therapy because of its more pronounced ability to induce apoptosis (Gallagher and Brown 1999; Nielsen and Maneval 1998).

In the present study, we have provided evidence that p21 is an even more potent growth suppressor than p53 of mouse tumor Renca cells in vitro and in vivo. This finding is rather surprising compared to the above-mentioned statements. Besides this, we demonstrated that the p21 gene also induced apoptosis in Renca cells. It therefore remains to be resolved why these two genes display such diverse effects in different systems. The induction of apoptosis after p53 overexpression was usually correlated with the endogenous p53 status, being more pronounced in p53mut or p53null than in p53wt or in nontransformed cells (Gallagher and Brown 1999; Nielsen and Maneval 1998; D'Orazi et al. 2000). There is, to our knowledge, no data of the p53 and/or p21 gene status in Renca cells. However, we have shown no evidence of the p53-basal level that could point to possible null mutation. On the other hand, the basal p21 level was readily detected, which could mean that p21 is induced in a p53-independent manner. Previously, we showed similar results with human colon carcinoma cells, CaCo-2, but neither p53 nor p21 induced apoptosis in this cell line, and we presumed that the basal p21 level could offer protection from either p53- or p21-induced apoptosis (Kralj et al. 2003). Since this is in contrast to the results presented in this work, we assume that possible species differences are responsible for the divergent outcomes. Similarly, Duttaroy et al. showed that the additional increase of p21 beyond the basal level, seen in serum-deprived quiescent mouse 3T3 fibroblasts, is associated with apoptosis (Duttaroy et al. 1997).

Furthermore, the immunocytochemical staining of cell cultures showed almost identical percentage of positive cells to both viral-encoded p53 and p21 proteins, so the reason for less pronounced Ad5CMV-p53 inhibitory effect is not its lower transduction efficacy or lower p53 protein expression. In addition, induction of endogenous mouse p21, as evidenced by Western blot, indicates that the exogenous p53 was functionally active. The similar results on mouse prostate tumor cell line 148-1PA were obtained by Eastham and coworkers (Eastham et al. 1995).

However, Ad5CMV-p21 induced apoptosis in Renca cells to a lesser extent than Ad5CMV-p53, so it is possible that p21 inhibited tumor cell growth by both arresting cell cycle and inducing apoptosis. Our results are in contrast to the observation of Yang and coworkers, who could not demonstrate any evidence for apoptosis in ADV-p21-infected Renca cells (Yang et al. 1995). It is not quite clear, though, which MOI the authors used for the cell infection; we could easily detect apoptosis using infection at both MOI 50 (data not shown) as well as MOI 100.

Interestingly, the results of parallel infection of different tumor cells showed that higher MOIs were required for infection of mouse in contrast to human cells (data not shown). Moreover, among several mouse cell lines tested the best inhibitory results were obtained with Renca cells. This was obviously due to low transgene expression in other cell lines, as it was shown by the difference of p21 and p53 protein level in Renca and B16Bl6 cells. These results are in accordance with those of Nielsen et al. who showed that the breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-435 was unaffected with adenovirus-mediated p53 expression (Nielsen et al. 1997), which was probably due to low adenovirus transduction. Since entry of adenovirus into host cells involves interactions of virus particles with two distinct receptors—Coxackie-adenovirus receptor (CAR) and αvβ3 or αvβ5 integrins—probably Ad-mediated gene expression is dependent on CAR and/or integrins expression (Nielsen and Maneval 1998; Zhang 1999).

More pronounced inhibitory effect of Ad5CMV-p21 than Ad5CMV-p53 was especially obvious in tumor growth suppression in vivo. For instance, the introduction of Ad5CMV-p21 into Renca tumor cells followed by in vivo inoculation completely suppressed the growth of tumors in all animals, while in group of animals that were inoculated with Ad5CMV-p53 infected cells, tumors developed in two out of six animals. Similarly, Ad5CMV-p21 significantly inhibited the growth of established tumors, while the effect of Ad5CMV-p53, although present, was not statistically significant in all tested points. However, none of the animals treated with either single or multiple doses of adenoviral vectors was tumor free, as was shown by Yang and coworkers (Yang et al. 1995) or Li and coworkers (Li et al. 1998). This was probably due to the lower doses of vectors used in our study. Unlike Li and coworkers (Li et al. 1998), we could not detect any difference between single and multiple doses used. A certain inhibitory effect of control vector was detected, however, in the experiments when a single dose was used for the treatment. Similar results were also obtained by Yang et al. and Li et al. as well as by other authors (Yang et al. 1995; Li et al. 1998).

Although p21 was identified as the first CKI and its biological function was mostly attributable to p53-dependent and p53-independent cell cycle arrest, a vast array of possible interactions and regulatory networks regarding p21 molecule have additionally been discovered. These different networks are probably responsible for the divergent responses of p21 overexpression in different cell lines. Some of them could be, for example, responsible for its anti-apoptotic functions and some of them for its pro-apoptotic functions (Dotto 2000; Roninson 2002). On the other hand, as we believe, they could differ between species, thus explaining the more pronounced p21 inhibitory activity in mouse cells than in human cells. However, the precise mechanism is still not known so further studies on the p21 and p53 role in cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in mouse cells, especially protein profiling data, are needed.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by grant 0098092 from the Ministry of Science and Technology, Republic of Croatia. We thank Mihaela Alivojvodić for expert technical assistance, and Dr. Anđelko Hrženjak and Dr. Saša Frank for useful discussions.

References

- Cardinali M, Jakus J, Shah S, Ensley JF, Robbins KC, Yeudall WA (1998) p21(WAF1/CIP1) retards the growth of human squamous cell carcinomas in vivo. Oral Oncol 34:211–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayman GL, Liu TJ, Overholt SM, Mobley SR, Wang M, Janot F, Goepfert H (1996) Gene therapy for head and neck cancer. Comparing the tumor suppressor gene p53 and a cell cycle regulator WAF1/CIP1 (p21). Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 122:489–493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Orazi G, Marchetti A, Crescenzi M, Coen S, Sacchi A, Soddu S (2000) Exogenous wt-p53 protein is active in transformed cells but not in their non-transformed counterparts: implications for cancer gene therapy without tumor targeting. J Gene Med 2:11–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dotto GP (2000) P21WAF1/CIP1: more than a break to the cell cycle. Biochim Biophys Acta 1471:M43-M56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duttaroy A, Qian J-F, Smith JS, Wang E (1997) Up-regulated p21CIP1 expression is part of the regulation quantitatively controlling serum deprivation-induced apoptosis. J Cell Biochem 64:434–446 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastham JA, Hall SJ, Sehgal I, Wang J, Timme TL, Yang, G Connell-Crowley L, Elledge SJ, Zhang WW, Harper JW, Thompson TC (1995) In vivo gene therapy with p53 or p21 adenovirus for prostate cancer. Cancer Res 55:5151–5155 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekholm SV, Reed SI (2000) Regulation of G1 cyclin-dependent kinases in the mammalian cell cycle. Curr Opin Cell Biol 12:676–684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Deiry WS, Tokino T, Velculescu VE, Levy DB, Parsons R, Trent JM, Lin D, Mercer WE, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B (1993) WAF1, a potential mediator of p53 tumor suppression. Cell 75:817–825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evan GI, Vousden KH (2001) Proliferation, cell cycle, and apoptosis in cancer. Nature 411:342–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fotedar R, Brickner H, Saadatmandi N, Rousselle T, Diederich L, Munshi A, Jung B, Reed JC, Fotedar A (1999) Effect of p21waf1/cip1 transgene on radiation induced apoptosis in T cells. Oncogene 18:3652–3658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher WM, Brown R (1999) p53-oriented cancer therapies: current progress. Ann Oncol 10:139–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartel AL, Serfas MS, Tyner AL (1996) p21-negative regulator of the cell cycle. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 213:138–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotoh A, Kao HC, Ko SC, Hamada K, Liu TJ, Chung LWK (1997) Cytotoxic effects of recombinant adenovirus p53 and cell cycle regulator genes (p21WAF1/Cip1 and p16CDKN4) in human prostate cancers. J Urol 158:636–641 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper JW, Adami GR, Wei N, Keyomarsi K, Elledge SJ (1993) The p21 Cdk-interacting protein Cip1 is a potent inhibitor of G1 cyclin-dependent kinases. Cell 75:805–816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann M, Lorenz HM, Voll R, Grunke M, Woith W, Kalden JR (1994) A rapid and simple method for the isolation of apoptotic DNA fragments. Nucleic Acid Res 22:5506–5507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingorani R, Bi BY, Dao T, Bae Y, Matsuzawa A, Crispe IN (2000) CD95/Fas signaling in T lymphocytes induces the cell cycle control protein p21cip-1/WAF-1, which promotes apoptosis. J Immunol 164:4032–4036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollstein M, Shomer B, Greenblatt M, Soussi T, Hovig E, Montesano R, Harris CC (1996) Somatic point mutations in the p53 gene of human tumors and cell lines: updated compilation. Nucleic Acid Res 24:141–146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi US, Dergham ST, Chen YQ, Dugan MC, Crissman JD, Vaitkevicius VK, Sarkar FH (1998) Inhibition of pancreatic tumor cell growth in culture by p21WAF1 recombinant adenovirus. Pancreas 16:107–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katayose D, Wersto R, Cowan KH, Seth P (1995) Effects of a recombinant adenovirus expressing WAF1/Cip1 on cell growth, cell cycle and apoptosis. Cell Growth Differ 6:1207–1212 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kralj M, Husnjak K, Körbler T, Pavelić J (2003) Endogenous p21WAF1/CIP1 status predicts the response of human tumor cells to wild-type p53 and p21WAF1/CIP1 overexpression. Cancer Gene Ther 10:457–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Rakkar A, Katayose Y, Kim M, Shanmugam N, Srivastava S, Moul JW, McLeod DG, Cowan KH, Seth P (1998) Efficacy of multiple administrations of recombinant adenovirus expressing wild-type p53 in an immune-competent mouse tumor model. Gene Ther 5:605–613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen LL, Maneval DC (1998) p53 tumor suppressor gene therapy for cancer. Cancer Gene Ther 5:52–63 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen LL, Dell J, Maxwell E, Armstrong L, Maneval D, Catino JJ (1997) Efficacy of p53 adenovirus-mediated gene therapy against human breast cancer xenografts. Cancer Gene Ther 4:129–138 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noda A, Ning Y, Venable SF, Pereira-Smith OM, Smith JR (1994) Cloning of senescent cell-derived inhibitors of DNA synthesis using an expression screen. Exp Cell Res 211:90–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker LP, Wolf JK, Price JE (2000) Adenoviral-mediated gene therapy with Ad5CMVp53 and Ad5CMVp21 in combination with standard therapies in human breast cancer cell lines. Ann Clin Lab Sci 30:395–405 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramondetta L, Mills GB, Burke TW, Wolf JK (2000) Adenovirus-mediated expression of p53 or p21 in papillary serous endometrial carcinoma cell line (SPEC-2) results in both growth inhibition and apoptotic cell death: potential application of gene therapy to endometrial cancer. Clin Cancer Res 6:278–284 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roninson IB (2002) Oncogenic functions of tumor suppressor p21Waf1/Cip1/Sdi1: association with cell senescence and tumour-promoting activities of stromal fibroblasts. Cancer Lett 179:1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth JA, Cristiano RJ (1997) Gene therapy for cancer: what have we done and where are we going? J Natl Cancer Inst 89:21–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekiguchi T, Hunter T (1998) Induction of growth arrest and cell death by overexpression of the cyclin-Ckd inhibitor p21 in hamster BHK21 cells Oncogene 16:369–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh MS, Rochefort H, Garcia M (1995) Overexpression of p21 WAF1/CIP1 induces growth arrest, giant cell formation and apoptosis in human breast carcinoma cell lines. Oncogene 11:1899–1905 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherr CJ (1996) Cancer cell cycles. Science 274:1672–1677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata M-A, Yoshidome K, Shibata E, Jorcyk CL, Green JE (2001) Suppression of mammary carcinoma growth in vitro and in vivo by inducible expression of the Cdk inhibitor p21. Cancer Gene Ther 8:23–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart ZA, Pietenpol JA (2001) p53 signaling and cell cycle checkpoints. Chem Res Toxicol 14:243–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsao Y-P, Huang S-J, Chang J-L, Hsieh J-T, Pong R-C, Chen S-L (1999) Adenovirus-mediated p21Waf1/Cip1 gene transfer induces apoptosis of human cervical cancer cell lines. J Virol 73:4983–4990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vousden KH (2000) p53: Death star. Cell 103:691–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace-Brodeur RR, Lowe SW (1999) Clinical implications of p53 mutations. Cell Mol Life Sci 55:64–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang ZY, Perkins ND, Ohno T, Nabel EG, Nabel GJ (1995) The p21 cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor suppress tumorigenicity in vivo. Nature Med. 1:1052–1056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang WW (1999) Development and application of adenoviral vectors for gene therapy of cancer. Cancer Gene Ther 6:113–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang WW, Fang XM, Mazur W, French BA, Georges RN, Roth JA (1994) High-efficiency gene transfer and high-level expression of wild-type p53 in human lung cancer cells mediated by recombinant adenovirus. Cancer Gene Ther 1:5–13 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]