Abstract

Following passage of the Coal Mine Health and Safety Act of 1969, underground coal mine operators were required to take air samples in order to monitor compliance with the exposure limit for respirable dust, a task essential for the prevention of pneumoconiosis among coal workers. Miners objected, claiming that having the mine operators perform this task was like “having the fox guard the chicken coop.”

This article is a historical narrative of mining industry corruption and of efforts to reform the program of monitoring exposure to coal mine dust. Several important themes common to the practice of occupational health are illustrated; most prominently, that employers should not be expected to regulate themselves.

WHEN REGULAR MONITORING of underground miners’ exposure to respirable dust began in 1970, many miners scoffed at having coal mine operators take their own dust samples. Mine operators had vigorously opposed the Coal Mine Health and Safety Act of 1969. They said it was unnecessary, unfeasible, and unconstitutional. Nevertheless, Congress delegated to them the role of taking samples to determine compliance with the exposure limit. Miners were astounded. They said it was like “having the fox guard the chicken coop.”1

The dust-monitoring program was one part of a significantly larger effort to make coal mining safer, to prevent disease, and to compensate disabled miners. The Coal Mine Act resulted from years of effort by coal miners, the United Mine Workers of America, and supporters. The original aim, begun in the mid-1960s, was to get a bill through the West Virginia legislature to compensate miners with pneumoconiosis, or “black lung.” In November 1968, a huge explosion killed 78 miners at a mine in Farmington, WVa. This catastrophe, the first mine disaster to have been televised, added significantly to the momentum. Throughout the fall of 1968 and into 1969, miners in the southern Appalachian coal fields organized a wildcat strike and continued to press their case for a compensation bill. In 1969, the focus moved to the US Congress, where the Federal Coal Mine Health and Safety Act was drafted, debated, and passed. It was signed by President Richard Nixon on December 31, 1969.2

This act contained several provisions that, by today’s standards, represent an exceptional regulatory intervention by the government into the industry. Inspections of underground coal mines 4 times a year were mandatory, with no exceptions based on size or any other factor. Inspectors could close all or parts of mines on their own authority. It established comprehensive standards requiring mine operators to prevent fires and explosions, to develop plans to support mine roofs, and to provide adequate ventilation to control gas and dust.

One of the most controversial provisions was a plan to compensate miners disabled by black lung. It also created a comprehensive plan to prevent black lung, including medical surveillance, medical research, research and development on dust control, a stringent (compared with standards in other coal-producing nations) exposure limit for respirable dust, and—our concern in this article—a system for monitoring exposure and enforcing the exposure limit. When Congress passed the Mine Safety and Health Act (hereafter called the Mine Act) in 1977, which brought all mines under the jurisdiction of the Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA), the new legislation preserved the dust-monitoring provisions of the 1969 Coal Mine Act.3

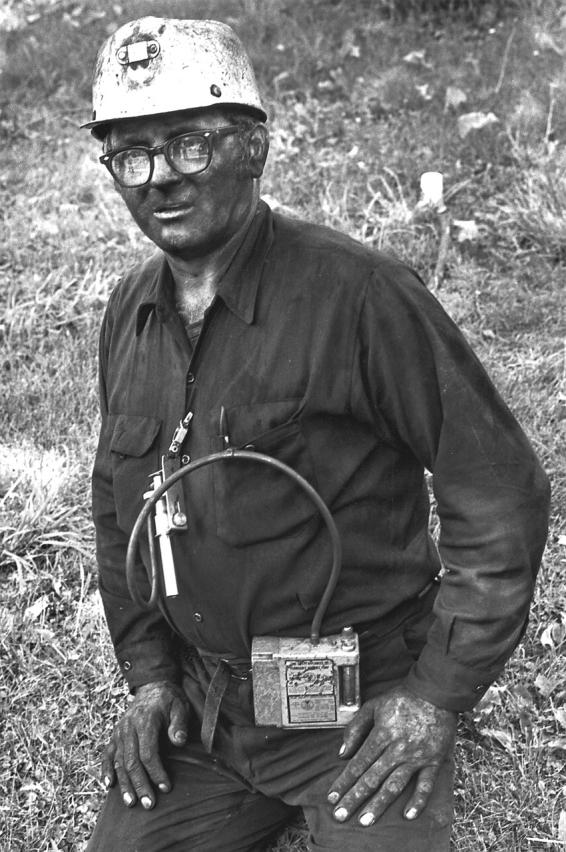

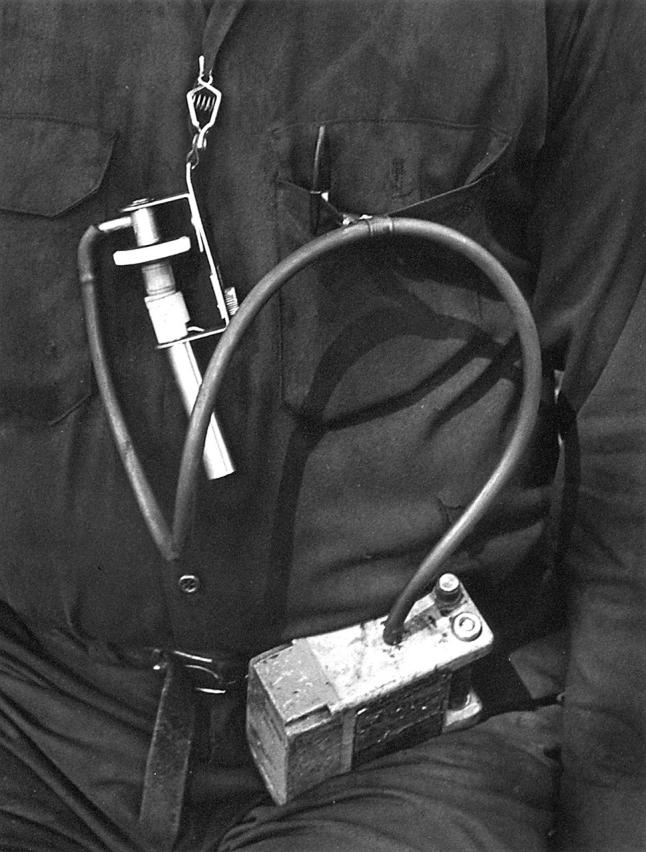

As one of its first tasks, MSHA proposed regulations that would address some of the concerns miners raised about the dust-monitoring program.4 In response to the same problems, the Bureau of Mines was developing instruments that would be tamper resistant or that could be mounted on a mining machine and would display dust concentrations in real time.5 During the summer of 1978, MSHA organized public hearings to consider the proposed rules. The United Mine Workers recruited many miners to testify about the ways that mine operators cheated when taking dust samples.6 Some of these methods were legal and exploited loopholes in the regulations; miners said, for example, that when dust samples were taken, operators would reduce production, increase ventilation, and assign miners who wore “samplers”—the devices by which dust samples were collected, shown in images on pages 1237 and 1238—to less dusty jobs. Other ways of cheating were blatantly illegal. Some operators, for example, placed samplers in clean areas of the mine, turned the samplers off before the shift was over, took samples outside the mine, discarded filter cassettes (the part of the sampler on which respirable dust is collected) that looked too dirty, and intentionally voided samples.

In spite of manifest problems, action on the proposed reforms ended with the election of Ronald Reagan as president. The proposals were quietly withdrawn in 1985 and development of the machine-mounted dust monitor ended.7 Mr Reagan had been elected on a strong sentiment of deregulation, and ending reform of the dust-monitoring rules was just one of many similar measures taken by the new administration.

One reform survived: miners were no longer required to sign dust data cards that accompanied the samples. This was not a mere cosmetic change. During the hearings in 1978, miners testified that they had been asked to sign blank cards before the sample was taken; that cards were switched if they had a “bad” sample (i.e., one with a lot of dust on it); that signatures were forged on data cards; that miners who refused to sign the data card were sent home for the day; that if they turned in a “bad” sample, they were required to continue wearing the sampler until they got a “good” one.

An attorney representing miners for black lung benefits testified that mine operators introduced dust data cards signed by the claimant into hearings in order to discredit the miner’s claim that he was disabled because of dust at the operator’s mine.8 Though seldom permitted as evidence, it was a nettlesome practice, literally adding insult to injury, given the sordid manner in which these cards were filled out and signed. Signatures are now voluntary.

In the early 1990s, corruption resurfaced, setting in motion another reform effort that was similar to the proposals that were halted by the Reagan administration. This time, the eventual remedy recommended by an advisory committee, appointed by the secretary of labor (discussed below under “Corruption, Again”), was for MSHA to take over all dust sampling in coal mines.9 In addition, MSHA, along with the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, renewed research and development on a real-time dust monitor. This monitor used the same technology that was developed in the 1970s and stopped in 1980. In a repeat of history, the more recent reform effort was withdrawn by the administration of George W. Bush; development of the real-time dust monitor, however, continues to this day.

This article recounts the current reform effort in this historical context and draws from it some important lessons for the practice of occupational health. It is axiomatic that accurate and reliable measures of workers’ exposure to health hazards is an essential aspect of preventing occupational disease. If measurements lack credibility, prevention efforts also lack credibility and are less likely to be effective.

CONDITIONS BEFORE THE COAL MINE ACT

Before the Coal Mine Act of 1969, there was no mandatory exposure limit for respirable dust. Even so, the Bureau of Mines measured exposure and discovered that exposure levels for continuous miner operators, the workers who consistently experienced the highest exposure, was about 6 mg/m3—a high level and, in retrospect, consistent with the large number of miners later found to have been disabled by pneumoconiosis. The average level had dropped to 3 mg/m3 within 18 months after the act was passed and to 2 mg/m3 in another year.10 This is a surprisingly rapid decline, especially so in light of complaints by mine operators that the exposure limit was not feasible, and it begs for an explanation.

One explanation is that the Coal Mine Act had successfully compelled mine operators to reduce exposure to respirable dust. The dust control methods used successfully in today’s mines were developed by the US Bureau of Mines during the 1950s. When the Coal Mine Act was passed in 1969, adopting these methods required some changes in work practices and ventilation controls and some capital investment for those mines that needed larger fans. But many mine operators already had high-capacity ventilation systems to remove methane from the mines. By 1969, dust control methods were practically off-the-shelf. What was lacking was an imperative to implement them. That was provided by the Coal Mine Act, which gave the Mining Enforcement Safety Administration, MSHA’s predecessor, significant enforcement powers that compelled mine operators to improve conditions.11

Another possible explanation, born of speculation and hindsight, is that many dust samples taken after the act was passed were fraudulent. The samples taken before the act were of little consequence for mine operators because there was no exposure limit, compensation for pneumoconiosis was limited, and the Bureau of Mines had limited enforcement powers. Moreover, the bureau, rather than mine operators, took the samples. Thus, before the Coal Mine Act, mine operators had fewer incentives to cheat and limited opportunities. By this reasoning, samples taken before the Coal Mine Act were probably more accurate than those taken afterwards. When the act linked dust sampling by operators to enforcement, fraudulent samples may have created the illusion of a rapid decline in dust exposure.

STATUTORY FRAMEWORK

The Coal Mine Act of 1969 brought significant changes to the industry. Its language is a necessary starting place for discussing current policy about dust monitoring. Congress delegated dust sampling for compliance purposes to mine operators and in so doing created a structural defect that has persisted to the present. It created both the incentive and the opportunity for mine operators to submit fraudulent samples. Section 202(a) of the Mine Act of 1977, which superseded the 1969 legislation, states that “Each operator of a coal mine shall take accurate samples of the amount of respirable dust in the mine atmosphere to which each miner in the active workings of such mine is exposed.” (Unless stated otherwise, all references to specific sections are to the 1977 act.) MSHA promulgated regulations requiring mine operators to take dust samples bimonthly. These samples are the principal means of determining noncompliance.12

The legislation also requires operators to “continuously maintain the average concentration of respirable dust in the mine atmosphere during each shift to which each miner in the active workings of such mine is exposed at or below 2.0 milligrams of respirable dust per cubic meter of air.”13 “Average” is defined as follows:

. . . a determination which accurately represents the atmospheric conditions with regard to respirable dust to which each miner in the active workings of a mine is exposed (1) as measured, during the 18 month period following the date of enactment of the Act [i.e., December 31, 1969], over a number of continuous production shifts to be determined by the Secretary [of Labor] and the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare [now the Department of Health and Human Services], and (2) as measured thereafter, over a single shift only, unless the Secretary and the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare find, in accordance with the provisions of section 101 of this Act [authorizing standards-setting for exposure to toxic materials], that such single shift measurement will not, after applying valid statistical techniques to such measurements, accurately represent such atmospheric conditions during such shift.14

This tortuous and often-parsed language, all one sentence, has been the focus of policy debate and litigation for the past several years. Its legislative history is limited and, consequently, so is our understanding of congressional intent. Its clumsiness has the mark of political compromise. The original House version of the Coal Mine Bill mandated multiple shift sampling, but the Senate version prohibited it.

This language is clearly inconsistent with language elsewhere in the act. In Section 202(2)(b)(2), mine operators are required to maintain average dust exposure at or below the standard for each miner on each shift. “Each” implies a single miner and a single shift. An “average,” however, is determined by sampling “over a number of continuous production shifts.” One cannot, as a matter of simple logic, determine exposure for each shift by sampling several. Variation between shifts is substantial, so that measuring the “average” exposure of each shift by averaging measurements of multiple shifts obscures instances of exposure above the limit. It is like trying to measure Tom’s height by taking the average height of Tom, Dick, and Harry.

Yet the practice for the past 30 years has been for mine operators to measure exposure at the same occupation over 5 consecutive shifts. When MSHA takes dust samples, it does so for several miners on the same production shift and calculates the average for each shift but not for each miner. The same logical fallacy applies. One (impractical) way to take an “average” exposure for each miner on each shift is to place several samplers on a single miner and average the result. The other way is to use the conventional industrial hygiene measure, the time-weighted average, the only logical meaning of “average.”

Under Section 202(f), the Mining Enforcement and Safety Administration, MSHA’s predecessor and the Department of Health and Human Services were required to investigate whether single shift measurements accurately reflected conditions.15 When it was found that they did not, MSHA implemented these statutory provisions with regulations that require mine operators to take samples over 5 consecutive shifts. It is the average of these 5 samples that is used to determine noncompliance with the standard.12

There are 4 troublesome features with this policy. First, operators themselves take the samples. Second, these samples are the principal means of determining compliance with the exposure limit. Taken together, these create an obvious conflict of interest. Third, and compounding this defect, MSHA, until recently, provided minimal oversight over the whole program. Aside from training and certifying the operator’s employee, the so-called certified person, for taking samples, MSHA did little more than receive and process dust samples, calculate averages, and, in so doing, determine noncompliance. Finally, citations for noncompliance are based on the average of 5 samples, thus allowing exposure above the limit for single shifts and, in the process, failing to guarantee that exposure is “at or below” (by Section 202[b][2]) the standard for each shift.

CORRUPTION, AGAIN

Corruption resurfaced early in the 1990s. MSHA discovered “abnormal white centers” (AWCs) in sampling filters; it looked like dust had been blown off the filters in order to reduce their weight. The occurrence of these AWCs was widespread, coming from approximately 1 out of 3 mines in the United States. Ironically, it was the secretary of labor of a Republican administration (that of George H. W. Bush), Lynn Martin, who used exceptionally inflammatory language when she announced citations. She accused the industry of having an “addiction to cheating,” a characterization that infuriated industry leaders.16 Not only did they want the citations withdrawn, they also wanted their honor restored.

Following this announcement, MSHA pursued 2 strategies. The first was to issue citations based solely only on the occurrence of an AWC and the second was, in concert with the US Department of Justice, to investigate practices at mines from which suspicious samples came.

The first strategy was a failure. After MSHA issued citations, mine operators as a group challenged the citations. A long and tedious evidentiary hearing followed in which the sole issue before the administrative law judge was whether the occurrence of the AWC was sufficient to issue citations.17

MSHA claimed that occurrence of an AWC was sufficient evidence. The administrative law judge hearing the case required MSHA to show that AWC samples could have occurred only through someone blowing on the filter. This standard of proof was itself a prominent controversy in the case. If there was any other way that an AWC could have been created, the administrative law judge stipulated, then MSHA could not issue a citation based solely on its occurrence. Industry experts testified at length that there were other ways they could have been created. In the end, sufficient doubt was created in the mind of the administrative law judge that he rejected MSHA’s citations.

A second piece of evidence that MSHA introduced was that as soon as MSHA announced that AWC samples would be rejected, their occurrence fell off rapidly. MSHA claimed that this demonstrated that mine operators controlled their occurrence. When plotted over time, there indeed seemed to be a precipitous decline in the frequency of AWC samples soon after MSHA made this announcement on March 26, 1991. Before that date, about 6.5% of all samples had AWCs, but afterwards fewer than 1% did. At some specific mines, the percentage of AWC samples dropped from 25% to zero.

But the industry’s statistical expert managed to undermine this interpretation. He showed that the decline in the frequency of AWC samples also correlated with dates of manufacture of filters that were more common among the AWC samples than others and that therefore manufacturing anomalies were a plausible explanation. He also argued that the decline in the occurrence of AWC samples began in September of the prior year and that there was no discontinuity around the date of the announcement. It is also plausible that mine operators could simply have not submitted AWC samples, regardless of whether they were fraudulent.

The judge, sufficiently persuaded by the industry’s statistician, concluded that MSHA had failed to carry its burden of proof with this argument also. In addition to invoking the industry’s statistician, he also stated that AWC samples continued to appear long after the announcement and long after considerable publicity about the case. Statistical correlation, he concluded in brief, was not sufficiently persuasive evidence of intentional tampering.18

However, the administrative law judge allowed MSHA to bring a case against a specific mine, Keystone’s Urling mine in Pennsylvania. MSHA brought the case, lost before the administrative law judge, appealed to the Federal Mine Safety and Health Review Commission, lost, appealed to the Federal District Court, and lost again.19

At one point during the appeal, dust technicians, in a bizarre celebration of incompetence, described their rough treatment of dust-monitoring instruments in an effort to demonstrate how the AWCs could have been created some other way than by blowing through the cassette filter. The judge summarized their testimony as follows:

[A dust technician] at Urling occasionally dropped cassettes on the floor when removing them from the sampling head or pushing in the plug. . . . [Another dust technician] has dropped pumps while carrying them from the Urling mine. He has had hoses catch on the car door and latch and on the drawer handles in the safety office. He has dropped cassettes when pulling them from the sampling head. He has stepped on hoses and has seen others step on hoses. When carrying loose pumps, [he] usually carried [them] by the hoses. He has placed pump-carrying boxes on the table in such a way that the hoses were caught under the box. . . . [A third dust technician] testified that when he placed pumps with the hoses wrapped around them in a carrying box, he had to push them into the box, thereby compressing the hoses on both sides of the pump. [He] used the trunk of his car to transport the pumps and samples and is certain that at times he shut the trunk lid on hoses or caught the hoses on the trunk latch.20

During the 1978 hearings, at least one miner testified about nearly identical practices as evidence of the carelessness of persons taking dust samples for mine operators.21 At that time, however, it was offered as evidence that samples were not trustworthy. With this case, 14 years later, it was offered in a mine operator’s defense, as an example of practices that could have resulted in AWC samples. That samples taken under these conditions were not valid was a foregone conclusion, but the implications in 1978 were completely different from those in 1992.

The second MSHA strategy—to investigate sampling practices more comprehensively and with the help of the Justice Department—was more successful but less publicized. MSHA gathered enough evidence to convict over 200 mine operators and their contractors on criminal charges of submitting fraudulent samples.22 Some of these mines were first identified because they had submitted AWC samples. But unlike the AWC cases discussed above, in these, the AWC samples were treated merely as one piece of evidence among others rather than the sole piece of evidence. MSHA gained convictions and punished the perpetrators by withdrawing certification papers, issuing fines, and placing the perpetrators under house arrest.

One of the largest operators in the nation was the first to be convicted. So compelling was the evidence that the operator entered a guilty plea on 13 counts of falsifying dust samples, including submitting AWC samples, taking samples outside the mine, and not taking samples at all but submitting blank filter cassettes.23 Other convicted operators took dust samples in the supply room at a mine and blew dust off the cassettes to reduce their weight. One consultant firm provided bogus, so-called “designer” samples to mine operators that they in turn submitted to MSHA as bona fide samples. Some operators would move the sampler to well-ventilated parts of their mines instead of at the face where it belonged. These and other practices bear a striking resemblance to the practices that miners had spoken of since the early 1970s and had formally testified about in 1978.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Analysis of dust-sampling data revealed other indicators of bias, most of which have appeared in the peer-reviewed scientific literature. Boden and Gold analyzed the occurrence of low concentration measurements in industry-wide samples.24 They found that samples showing concentrations less than or equal to 0.3 mg/m3 were more frequent among operator samples than among MSHA samples, and they suggested that there was systemic bias. Seixas and colleagues noted the same phenomenon.25 Weeks examined samples for each section of each mine, stratified by mining method. For the most common methods of mining, he found that very low concentration samples (0.1 mg/m3, the limit of detection for the sampling method) occurred far more frequently than expected in some mine sections than in others, by an observed to expected ratio of 20 to 1.26

Kogut, an MSHA statistician, examined MSHA samples taken on the same sections over several days. He compared the value of samples taken on the first day—when the only unannounced inspection was performed—with that on subsequent days and discovered that the concentration measured on the first day was consistently higher than it was on later days.27 These differences were not accounted for by historical trends, regression to the mean phenomena, or differences in production. Matched pairs of first and second MSHA samples show a similar phenomenon.28 This anomaly is important. It validates the commonsense notion that if the mine operator (or any employer) knows an inspection is imminent, he will take steps to reduce exposure. This is the idea behind provisions in both the 1977 Mine Act (Section 103[a]) and the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 (Section 17[f]) prohibiting advance notice of inspections.

REFORM

In light of miners’ testimony in 1978, criminal convictions, and problems manifest with the statistical analysis, it seems clear that there were problems with the existing sampling program. Partially in response to the analyses of Boden and Gold, Seixas et al., and Weeks, MSHA, in addition to prosecuting the criminal cases, began investigating dust-monitoring practices at mines that reported an excessive number of samples with low weight gain.29

MSHA also convened the Coal Mine Respirable Dust Task Group, consisting of personnel within MSHA.30 This task group was given a broad mandate to review the entire program. Among other matters, it advised MSHA to establish a Spot Inspection Program for the purpose of obtaining accurate measurements of dust levels to which miners were exposed. MSHA measured the average exposure at a sample of mines for several occupations on a single shift rather than its usual practice of measuring the exposure of occupations over several shifts. The Spot Inspection Program “revealed instances of overexposure that were masked by the averaging of results across different occupations.”31 This discovery seems a matter of elementary statistical logic that hardly needed experimental verification, but it led to the single sample policy described below.

MSHA also formed an advisory committee composed of miners, mine operators, and neutral observers, with the chairman and the majority of the committee having no economic interest in the coal industry.32 It had the curiously clumsy title “The Secretary of Labor’s Advisory Committee on the Elimination of Pneumoconiosis among Coal Mine Workers,” but it was commonly referred to as the Dust Advisory Committee. Neither in its charge nor its title was it evident that corruption of the dust-monitoring program was what brought it into existence and was its principal topic.

During this committee’s meetings, a panel of miners spoke about the dust-sampling program in ways reminiscent of testimony given in 1978; their testimony suggested, as had the criminal convictions noted above, that the problem of corruption in the dust-monitoring program was far greater than suggested by the AWCs.33 Excerpts follow:34

When they take dust samples, they cut in one direction, and he is outby and upwind from the dust.

We’ve got people on our longwall, some that work downwind of the shear constantly, but they’re told when Federal people are there, not to work downwind of the shear. And when they [MSHA] come to take their samples, 90% of the time, the longwall ends up on a repair date. They have to wait and come back. When they come back . . . they make exactly four cuts on our shear and they stop. After he leaves, they make an eight to ten cut day every day.

[W]e’re told that from the days that the pumps are coming in, that we need to make sure that the dust collection scrubbers on the miner are working at the maximum efficiency that we can get out of it, and make sure that they are cleaned exceptionally well, that the filters and everything are all double flushed, back flushed, and everything, so that everything’s working the maximum that they can possibly be working.

[T]he days that MSHA takes their dust samples . . . everything is wetted down. All the bits are changed. All the water sprays are working.

We have a longwall at our place. The jack-setters and the repairmen, and people like that, they’ve got to work in by the dust, where sometimes it’s so dusty that it would be like maybe this Committee sitting inside of a vacuum cleaner bag when its running, and this goes on daily, every day, as I said, 10 hours a day six days a week . . . until the dust samples are taken. For whatever reason, on those particular days, not much production is run.

THE SINGLE SAMPLE POLICY

The advisory committee recommended, among other things, that MSHA take over the whole dust-monitoring program. This was an ambitious recommendation and it faced some significant obstacles. The most formidable was the amount of resources needed to organize such a program. Under the current program, operators of underground mines take about 80 000 samples every year. MSHA claimed they would need to hire an additional 585 inspectors and commit $33.7 million to replicate the operators’ program. These are unlikely measures under most political circumstances and inconceivable at present.

Consequently, MSHA sought a program that would reduce its burden of sampling but would maintain the same level of surveillance (i.e., samples taken every 2 months on every section). The MSHA plan was to take samples on single shifts and to base determination of noncompliance on these samples considered separately, rather than on the average of 5 samples. An unspoken rationale for this approach derives from Kogut’s analysis.35 Kogut showed that MSHA samples taken after the first of several days’ sampling are systematically smaller than those taken on the first day. This suggests that the first day sample—a single sample, the only one that is unannounced—is the most accurate and, as such, is the only sample that meets the accuracy requirements of the act. Moreover, this conclusion meets the requirements of the act in another way, by using “valid statistical techniques.”

The situation is ironic. The presumption in the Mine Act is that samples would be taken over a single shift unless the secretaries of labor and of health and human services found that such measurements would not accurately represent the dust concentrations to which miners would be exposed. Multiple samples were presumed to be the relevant standard for “accuracy.” We now find that when MSHA takes samples, they are likely to be more accurate on the single shift when there is an unannounced inspection. The relevant standard for accuracy, even while it lacks precision, is in fact the single unannounced sample, not a multiple sample.

First announced in 1994, the single sample policy and variations have been entangled in litigation ever since.36 MSHA issued citations based on its announced policy, and mine operators contested on the grounds that MSHA could not adopt this policy without going through the formal rule-making process (Section 101 of the 1969 act). The Review Commission upheld the challenge; MSHA appealed to the federal district court and lost again.37 As noted above, Section 202(f) of the 1977 act is the governing statutory language. It requires that the average concentration of respirable dust should be measured over a single shift unless the secretaries of labor and of health and human services (i.e., MSHA and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health) “found” that such a measurement would not accurately represent conditions to which miners were exposed. The secretaries proposed such a finding in 1971, made it final in 1972, and laid the foundation for sampling on multiple shifts. Moreover, in making this finding, the secretaries were required to make their finding in accordance with the rule-making provisions of the act (Section 101). The basis of mine operators’ challenges and of the several court decisions was that MSHA had to follow this procedure.

Another challenge by coal mine operators occurred in 1999. Since 1975, MSHA had issued citations for noncompliance if the average of 5 samples taken on several occupations on a single shift exceeded the exposure limit. In 1999, operators contested this long-standing practice, claiming the citations were prohibited by the finding in 1971.38 An administrative law judge and the Review Commission were persuaded, and they vacated citations that had been based in this practice.39 MSHA appealed to the federal court of appeals, which, as of this writing, has not yet announced its decision.

Thus, in response to MSHA’s persistence in trying to make this policy change, it received equally persistent challenges by mine operators and the opinions of 2 administrative law judges, the Federal Mine Safety and Health Review Commission, and the court of appeals that they had to follow the rule-making procedures in the Mine Act, reverse the 1972 finding, and propose a new rule for review. MSHA and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health therefore sent a proposed rule to the Office of Management and Budget for review on July 7, 2000.32 As with President Reagan’s withdrawal of the 1978 reforms, this proposed rule was withdrawn by the new administration. MSHA revised and reissued it on March 6, 2003.40 Coal mine operators continue to take bimonthly samples. The fox still guards the chicken coop.

CONCLUSION

This tale is an unenlightening validation of common sense: regulated entities ought not to regulate themselves. It is a plain conflict of interest. It is for this reason that both the Mine Act and the Occupational Safety and Health Act require unannounced inspections. Even if self-monitoring is rationalized as the only feasible solution, cursory oversight by a regulatory agency invites abuse.

And the problem persists in other settings. The chairman of a health and safety committee of an underground mine in Kentucky wrote a memo in 2000 that was forwarded to the United Mine Workers of America. The memo describes the mine operator’s practices when MSHA monitored emissions from diesel-powered scoops during a longwall move. During this procedure, tons of machinery are moved to a new section of the mine using, in this case, diesel-powered vehicles that produce considerable exhaust. The committee member said,

When the emission tests were conducted . . . by MSHA on the longwall move, they [mine management] did not allow equipment to operate close together as they normally do. They tried to limit the number of scoops [a lowprofile front-end loader commonly used in mines] on the road at the same time. . . . They made sure the scoops did not idle. . . . They would allow only one scoop on the face line or recovery face to be loaded or unloaded. On a normal move, all of the scoops would get as close to the face as possible to wait to be loaded.41

POSTSCRIPT

Two important developments occurred as this article was going to press. First, in part as a response to strong and widespread criticism of the dust monitoring proposal published on March 6, 2003, and in part as a response to some promising developments concerning a direct-reading monitoring instrument, MSHA extended “until further notice” the rule-making schedule.42 Second, after the string of defeats described in this article, the US Court of Appeals deferred to the agency’s expertise and reversed the decision of the Review Commission, upholding the single shift (not single sample) sampling practice that Excel Mining had challenged.39,43

Figure 1.

Left: Miner at the end of a day shift wearing coal dust monitor in Bluefield, Va, ca. 1980. Photo by Earl Dotter.

Figure 2.

Closeup: Detail of dust sampling apparatus. Photo by Earl Dotter.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the United Mine Workers of America.

I acknowledge the constructive and thoughtful comments of 3 anonymous reviewers.

Note. The views expressed in this article are not necessarily those of the United Mine Workers of America or of Advanced Technologies and Laboratories.

Peer Reviewed

Endnotes

- 1.This phrase was common among miners whenever they discussed the dust-monitoring program. It has been heard many times by the author from the late 1970s to the present.

- 2.A. Derickson, Black Lung: Anatomy of a Public Health Disaster (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1998); B. E. Smith, Black Lung: The Social Production of Disease (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1983); D. M. Fox and J. F. Stone, “Black Lung: Miner’s Militancy and Medical Uncertainty, 1968–1972,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 34 (1980): 43–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mine Safety and Health Act, 30 USC §801, et seq (1977).

- 4.Miner Participation in the Respirable Dust Sampling Program, Notice of Proposed Rule-Making, 42 Federal Register 47001 (20June1977).

- 5.K. L. Williams and R. J. Timko, Performance Evaluation of a Real-Time Aerosol Monitor, Information Circular 8968 (Pittsburgh: US Department of the Interior, Bureau of Mines, 1984); K. L. Williams and R. P. Vinson, Evaluation of the TEOM Monitor, Information Circular 9119 (Pittsburgh: US Department of the Interior, Bureau of Mines, 1986).

- 6.Mine Safety and Health Administration, Transcript, Public Hearings on Dust Monitoring; Testimony of Mike Juvanelli, Harry Rossi, Rudolph Ciminetti, Phil Spencer, Junior Floyd, Fred Uslak, Gerald Abbott, and Peter Rutkowski (Pittsburgh, 13July1978, pp. 33–49); Testimony of Richard Perando, William Lane, and Otis Osborne (Charleston, WVa, 25July1978, pp. 14–20); Testimony of Dewey Cantley and Richard Cooper (Charleston, WVa, 25July1978, pp. 56–59).

- 7.Miner Participation in the Respirable Dust Sampling Program, 50 Federal Register 17450 (29April1985).

- 8.Mine Safety and Health Administration, Transcript, Public Hearings on Dust Monitoring; Testimony of Gail Falk (Charleston, WVa, 25July1978, pp. 46–55).

- 9.Report of the Advisory Committee on the Elimination of Pneumoconiosis Among Coal Mine Workers (Washington: US Department of Labor, Mine Safety and Health Administration, 1996). The author was a member of this Advisory Committee, 1 of 2 members representing the United Mine Workers of America.

- 10.M. Jacobson, P. S. Parobeck, and M. E. Hughes, Effect of the Coal Mine Health and Safety Act of 1969 on Respirable Dust Concentrations in Selected Underground Coal Mines, Information Circular 8536 (Washington: US Department of the Interior, Bureau of Mines, 1971).

- 11.J. L. Weeks, “From Explosions to Black Lung: A History of Efforts to Control Coal Mine Dust,” State of Art Reviews: Occupational Medicine 8 (1993): 1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mandatory Health Standards, 30 CFR Part 70: 100–120 (2002).

- 13.Mine Safety and Health Act, §202(b)(2).

- 14.Mine Safety and Health Act, §202(f).

- 15.Notice of Finding That Single Shift Measurements of Respirable Dust Will Not Accurately Represent Atmospheric Conditions During Such Shift, 36 Federal Register 138 (17July1971).

- 16.US Department of Labor Press Release, Statement of Secretary of Labor Lynn Martin (4April1991).

- 17.In Re: Contests of Respirable Dust Sample Alteration Citations, 15 FMSHRC 1456 (20July1993). FMSHRC stands for Federal Mine Safety and Health Review Commission.

- 18.Ibid, 1520.

- 19.Keystone Coal Mining Corporation v Secretary of Labor, Mine Safety and Health Administration, 16 FMSHRC 857 (20April1994); Keystone Coal Mining Corporation v Secretary of Labor, 17 FMSHRC 1819 (29November1995); Secretary of Labor v Keystone Coal Mining Corporation, 331 F2nd 422 (DC Cir 1998).

- 20.Keystone Coal Mining Corporation v Secretary of Labor, Mine Safety and Health Administration, 16 FMSHRC 857, 903 at 884. April1994.

- 21.Mine Safety and Health Administration. Public hearings on dust monitoring. Testimony of Harry Rossi (p35), Gerald Abbott (pp48–49), (Pittsburgh, 13July1078); Testimony of Mr Belt (pp112–13), James Rowe (p117), Mason Caudill (pp121–22) (Lexington, KY, 27July1978).

- 22.Mine Safety and Health Administration, Technical Compliance and Investigation Division (TCID), Summary of Criminal Proceedings, TCID Summaries, 6August1999.

- 23.United States of America v Peabody Coal Company, (SD WVa 1990).

- 24.L. I. Boden and M. Gold, “The Accuracy of Self-Reported Regulatory Data: The Case of Coal Mine Dust,” American Journal of Industrial Medicine 6 (1984): 427–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.N. S. Seixas, T. G. Robins, C. H. Rice, and L. M. Moulton, “Assessment of Potential Biases in the Application of MSHA Respirable Coal Mine Dust Data to an Epidemiologic Study,” American Industrial Hygiene Association Journal 51 (1990): 534–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.J. L. Weeks, “Estimating Possible Fraud in Coal Mine Operators’ Samples of Respirable Dust” [erratum appears in American Industrial Hygiene Association Journal 56 (1995): 775], American Industrial Hygiene Association Journal 56 (1995): 328–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.J. Kogut, “Multi-Day MSHA Sampling of Respirable Coal Mine Dust,” Memorandum for Ronald J. Schell, Chief, Division of Health, Coal Mine Safety and Health, 6September1994.

- 28.J. L. Weeks, unpublished data.

- 29.Boden and Gold, “Accuracy of Self-Reported Regulatory Data”; Seixas et al., “Assessment of Potential Biases”; Weeks, “Estimating Possible Fraud”; J. Spicer, “FY 1990 Health Standards Compliance Program,” Memorandum to District Managers, CMS&H Memo No. HQ-90-31-H (6009), 9January1990.

- 30.Mine Safety and Health Administration, Coal Mine Respirable Dust Task Group Report. Washington, DC: 1993.

- 31.Determination of Concentration of Respirable Coal Mine Dust, Proposed Rule, Part II, 65 Federal Register 42068 (7July2000).

- 32.U.S. Department of Labor, Mine Safety and Health Administration, Report of the Advisory Committee on the Elimination of Pneumoconiosis among Coal Mine Workers. 1996. Washington, DC, U.S. Department of Labor, Mine Safety and Health Administration.

- 33.Fifth Meeting of the Advisory Committee on the Elimination of Pneumoconiosis Among Coal Mine Workers, Lexington, Ky, 24July1996, Excerpts of Transcript; James Bell, pp. 927, 928; Frank Jeeters, pp. 935, 940; Bob Hicks, p. 941; Dwayne Childers, p. 954; John Stewart, p. 955.

- 34.Testimony of these miners requires some translation. A longwall section is a part of a mine that employs the longwall mining method. This method uses a machine (called a shear) with rotating cutter heads studded with bits that rides a track parallel to the face, a distance of up to 1,000 feet. As the shear traverses the face it cuts into the seam of coal, and the coal falls onto a conveyor and out of the mine. Longwall mining produces more dust than any other method and it is also has the highest productivity of any underground mining method. Consequently, it is a significant concern for mine operators, miners, and MSHA. In many dust control plans, mine operators are required to cut coal only during one pass along the face but not on the return. More than one of these miners said that mine operators only cut during one pass when they are taking dust samples but that at other times, they also cut on the return pass, thus increasing production of both coal and dust. “Inby” is a mining term that means, in this case, downwind from the shear and therefore in the dust; “outby” is the opposite. “Bits” refers to picks that are mounted on the cutter heads; when a bit is dull, it produces more dust. “Pumps” refers to dust sampling pumps. “Scrubbers” are a form of dust control using water sprays and a fan. The roof on a longwall section is supported by hydraulic jacks and consequently, the person who manages roof support is called a “jack-setter.” It is convenient for production, but not essential, for jacksetters to work inby the shear.

- 35.Kogut, “Multi-Day MSHA Sampling.”

- 36.Mine Shift Atmospheric Conditions; Coal Mine Dust Respirable Dust Standard Determination, Notice, 59 Federal Register 8357 (18February1994).

- 37.Keystone Coal Mining Corporation v Secretary of Labor, Mine Safety and Health Administration, 16 FMSHRC 6 (4January1994); Keystone Coal Mining Corporation v Secretary of Labor, Mine Safety and Health Administration, 17 FMSHRC 1819 (29November1995); National Mining Association et al. v Secretary of Labor, Mine Safety and Health Administration, 153 F2d 1262 (11th Cir 1998).

- 38.Excel Mining v Secretary of Labor, 21 FMSHRC 1401 (19November1999).

- 39.Excel Mining v Secretary of Labor, 23 FMSHRC 600 (29January2001).

- 40.Determination of Concentration of Responsible Coal Mine Dust, Proposed Rule, Part X, 68 Federal Register 10940 (6March2003); Verification of Underground Coal Mine Operators’ Dust Control Plans and Compliance Sampling for Respirable Dust, Proposed Rule, Part II, 68 Federal Register 10785 (6March2003).

- 41.B. Oldham, Letter to Joseph A. Main, Administrator, Department of Occupational Health and Safety, United Mine Workers of America, 5January2000.

- 42.Verification of underground coal mine operators’ dust control plans and compliance sampling for respirable dust. Federal Register. 3July2003;68:39881–82. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Secretary of Labor. MSHA v. Excel Mining and Federal Mine Safety and Health Review Commission. US Court of Appeals, DC Circuit. 8July2003. In press.