Abstract

Nuclear envelope (NE) irregularity is an important diagnostic feature of cancer, and its molecular basis is not understood. One possible cause is abnormal postmitotic NE re-assembly, such that a rounded contour is never achieved before the next mitosis. Alternatively, dynamic forces could deform the NE during interphase following an otherwise normal postmitotic NE re-assembly. To distinguish these possibilities, normal human thyroid epithelial cells were microinjected with the papillary thyroid carcinoma oncogene (RET/PTC1 short isoform, known to induce NE irregularity), an attenuated version of RET/PTC1 lacking the leucine zipper dimerization domain (RET/PTC1 Δzip), H (V-12) RAS, and labeled dextran. Cells were fixed at 6 or 18 to 24 hours, stained for lamins and the products of microinjected plasmids, and scored blindly using previously defined criteria for NE irregularity. 6.5% of non-injected thyrocytes showed NE irregularity. Neither dextran nor RAS microinjections increased NE irregularity. In contrast, RET/PTC1 microinjection induced NE irregularity in 27% of cells at 6 hours and 37% of cells at 18 to 24 hours. RET/PTC1 Δzip induced significantly less irregularity. Since irregularity develops quickly, and since no mitoses and only rare possible postmitotic cells were scored, postmitotic NE re-assembly does not appear necessary for RET/PTC signaling to induce an irregular NE contour.

An irregularity in nuclear shape is a common diagnostic abnormality in cancer cells, yet surprisingly little is known about the structural basis of this change or its functional significance. The large-scale organization of the nuclear envelope (NE) defines nuclear shape. The NE consists of two lipid bilayers, nuclear pores, and the nuclear lamina (reviewed in 1-4 ). One lipid bilayer is the outer nuclear membrane, which is continuous with the endoplasmic reticulum. To date, no biochemical difference is known to distinguish the outer nuclear membrane or its membrane-associated proteins from the endoplasmic reticulum. In contrast, the inner nuclear membrane facing chromatin contains a number of membrane-associated proteins that are specific to this lipid bilayer. In turn, the membrane-associated proteins of the inner nuclear membrane are tightly associated with the intermediate filament proteins, called lamins, to form the chromatin-associated nuclear lamina. 2,5,6 The inner nuclear lipid bilayer is continuous with the outer nuclear membrane at nuclear pores. Nuclear pores regulate vectorial import and export between the nucleus and cytoplasm. 7 Irregularity of NE shape, from any cause, could theoretically affect a number of cell physiologies. Nuclear lamina proteins are involved in determining replication competence 8-14 and organizing transcription by binding to and segregating heterochromatin 15 (reviewed in 16 ). Consistent with a role in organizing transcription, large-scale localization of genes near the NE is associated with transcriptional silencing. 17 Theoretically the function of nuclear pores could be altered within folds of the NE that would oblige them to export toward each other and thereby potentially segregate transport factors on one side of the NE (see also 18 ).

The irregularity of nuclear shape in cancer cells could derive from either an abnormal postmitotic NE re-assembly or dynamic disturbance of the NE during interphase. Major dynamics of the nuclear envelope occur during mitotic NE disassembly and re-assembly, mediated by specific phosphorylations and dephosphorylations of lamina proteins (reviewed in 5,19 ). Three large-scale dynamics of the NE described in molecular terms include mitotic breakdown, postmitotic re-assembly, and a gradual concentric enlargement following postmitotic nuclear envelope re-assembly mediated by the NE protein LAP2. 12,13,19 Much less is known about NE dynamics in interphase, perhaps in part because the NE is difficult to visualize in living cells that display NE irregularity.

Papillary thyroid carcinoma and follicular thyroid neoplasms are both derived from thyroid epithelial cells. 20 Papillary thyroid carcinoma is diagnosed mostly on the basis of dispersal of heterochromatin and prominent NE irregularity. 20 Follicular neoplasms are diagnosed on the basis of abnormalities in large-scale tissue architecture and tend to show round nuclei and heterochromatin aggregates that are often coarser than normal thyroid epithelial cells. 20 The differing nuclear morphological features that distinguish papillary and follicular-type tumors can be induced by expression of the genes associated with these two tumor types. RET/PTC1 is a chimeric tyrosine kinase originally identified through its ability to cause focus formation when DNA from papillary thyroid carcinomas was transfected into fibroblasts. 21 Subsequent studies showed that this oncogene was restricted to papillary thyroid carcinomas, 22 including some very small tumors. 23 When primary cultures of normal human thyroid epithelium are retrovirally infected with RET/PTC1, they develop NE irregularity and chromatin-clearing within 10 days. 24 The close association of RET/PTC activation with these nuclear morphological changes has been confirmed recently in human thyroid tumors. 25 RAS, on the other hand, is commonly activated in follicular neoplasms, 26 and it induces increased coarsening of chromatin in cells with maintenance of a spherical NE shape when expressed in thyroid epithelial cells or fibroblasts in culture. 24,27

To address whether the NE irregularity in papillary thyroid carcinomas mediated by RET/PTC requires a postmitotic NE re-assembly for expression, or whether it forms during interphase, we assessed the time-course of development of NE irregularity following intranuclear microinjection of RET/PTC1. Our results show that major deflections of the NE must occur in a dynamic fashion during interphase since they do not require postmitotic NE re-assembly.

Materials and Methods

IRB Approval and Human Tissue Samples Studied

Institutional review board approval for these studies of human cells was obtained. Primary cultures of normal human thyroid cells, obtained from thyroid glands that had no goiterous change and no lymphocytic thyroiditis were established in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium, Ham’s F12, and MCDB 104 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) (2:1:1 ratio), according to previously published protocols. 28 A total of five different normal thyroid cultures from five patients were studied, and each of the microinjection conditions were performed on at least two different cultures.

Plasmids Studied

RET/PTC1 short isoform was cloned into pRc/CMV plasmid (Invitrogen). RET/PTC1 Δzip is RET/PTC1 with deletion of the dimerization domain of the H4 protein, as previously described. 29 This was also cloned into the pRc/CMV plasmid. RAS is an activated H-RAS with valine at position 12 (H-T24) bearing an N-terminal hemagglutinin tag, driven by a cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter in the mammalian expression vector pDCR (a kind gift of Drs. Michael White and Channing Der). 30 All plasmids were prepared using an endotoxin-free system from Qiagen (Valencia, CA).

Microinjection Procedure

Primary normal human thyroid cell cultures were seeded generally within the second to fourth passage in 35-mm Corning plastic dishes onto which four 1-mm squares were etched. HEPES buffer was added to the culture media to 20 mmol/L during the microinjection procedure. Cells were microinjected at room temperature with Eppendorf Brinkmann Femto-tips (Brinkmann catalog number 930–00-003–5, Eppendorf, Westbury, CT), using an Eppendorf 5246 microinjector equipped with Eppendorf micromanipulator 5171. Generally 100 cells were injected in each of the 1-mm squares. Average injection conditions included injection time of 0.3 seconds, initial pressure of 80 hecto Pascals, and compensation pressure of 60 hecto Pascals. About 800 cells can be microinjected in their nuclei in one day. All plasmids were at 1 μg/ul in microinjection buffer containing PBS with 2 mmol/L Mg Cl2 and 0.6 mg/ml fluorescently labeled dextran. Fluorescein and cascade-blue-labeled lysine formalin-fixable dextrans, 10,000 mol/L, were purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR).

Fixation and Immunostaining

Following incubation of the cells at 37°C in thyroid media for 6 or 18 to 24 hours, cells were fixed onto the dish by rinsing with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) followed by addition of 10% normal buffered formalin for 15 minutes at room temperature. Dishes were then stored for up to 72 hours in PBS at 4°C. Permeabilization with 0.5% Triton X-100 was followed by blocking with 10% human serum for 20 minutes at room temperature in PBS. Primary antibodies were Goat polyclonal anti-RET antibody (dilution 1:100, catalog number 167-G; Santa Cruz), rabbit polyclonal anti-lamin A/C antibody (dilution 1:50), a kind gift of Nilhabh Chaudhary, 3 and anti-hemagglutinin mouse hybridoma clone 12CA5 supernatant. Primary antibodies were diluted in the blocking solution and were incubated for 1 hour at 37°C. Secondary antibodies included CY3-labeled donkey anti-goat antibody (1:500), CY3-labeled sheep anti-mouse antibody (1:500), and FITC-labeled donkey anti-rabbit antibody (1:100; all from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA); secondary antibodies were prepared in blocking buffer and were applied for 30 minutes at room temperature. DAKO fluorescent mounting media was used after extensive washing in PBS (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA).

Scoring NE Irregularity

NE contour was scored blindly by one individual at a magnification of ×600 (×40 objective and ×15 oculars) using a conventional epifluorescence microscope equipped with separate filter cubes for the different fluorochromes. A regular NE is defined as having a smooth arc for at least a continuous 25% of its perimeter. An irregular NE therefore lacks a smooth arc over at least 75% of its mid-nuclear perimeter. These criteria for scoring NE contour have been previously shown to be reproducible between different blinded observers. 24 Scoring of cells expressing RET/PTC1, RET/PTC1 Δzip, and RAS was able to be performed in a blinded fashion because the immunostaining pattern of anti-RET and anti-hemagglutinin (for RAS) was identical. The 1-mm square quadrants were scanned for all cells that expressed an injected plasmid. After data began to suggest that NE irregularity occurred rapidly, cells were microinjected apart from each other such that a non-injected cell separated two injected cells. It was expected that postmitotic cells would appear as doublets on the plate, whereas if no mitosis occurred injected cells would still be likely to have a non-expressing cell as a closest neighbor. From that point on, cells were scored as occurring either as a doublet versus singly, based on whether or not the closest nucleus to an expressing cell belonged to another cell that did or did not express a microinjected plasmid, respectively. For each plate of cells that were microinjected, 100 random cells outside of the 1-mm squares that had not been injected were scored for NE irregularity. χ2 test of the proportions tested significance.

Results

Characteristics of the Microinjection Procedure

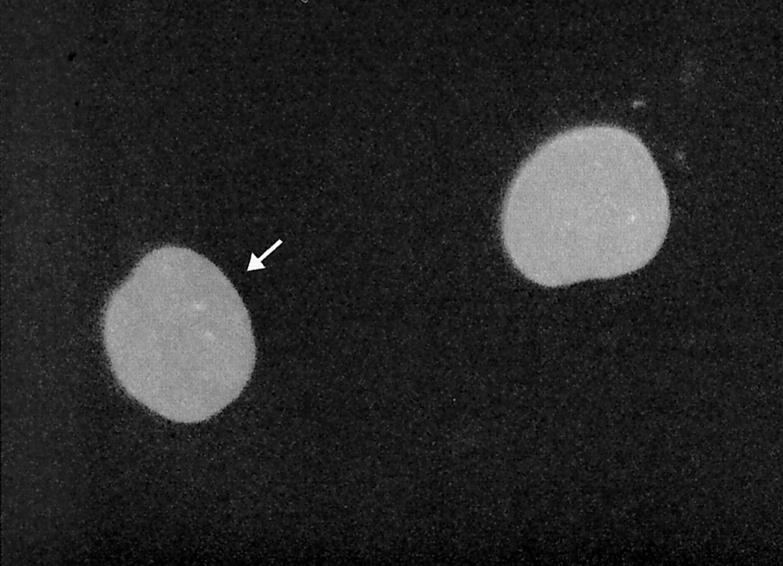

Intranuclear rather than intracytoplasmic injections are required to express plasmid DNAs. 31 The microinjection procedure per se was therefore extensively characterized for its effect on nuclear morphology. As suggested by previous investigators, 31-34 the DAPI staining pattern of the chromatin (not shown), the phase contrast appearance, the immunostaining pattern of the lamins, and NE contour were all unaltered in cells recovered 6 hours after microinjection of fluorescently labeled dextran and immunostaining. No residual “hole” in the nuclear lamina was evident, as though the nuclear lamina resealed quickly and smoothly. Figure 1 ▶ shows that the lamin-immunostaining pattern of one cell (arrow) 6 hours after intranuclear microinjection of cascade blue dextran (dextran label not shown) does not differ from a control non-injected cell. The rate of nuclear envelope irregularity, as assessed by scoring contour after lamin immunostaining, in control dextran-injected cells was somewhat less (but not significantly) than the rate of irregularity in non-injected cells. 18 hours after dextran injection, nuclear envelope irregularity was seen in 5 of 138 injected cells (3.6%) compared to a background rate of irregularity (6.5%) in non-injected cells. Six hours after microinjection of dextran, 6 of 119 injected cells showed nuclear envelope irregularity (5.0%).

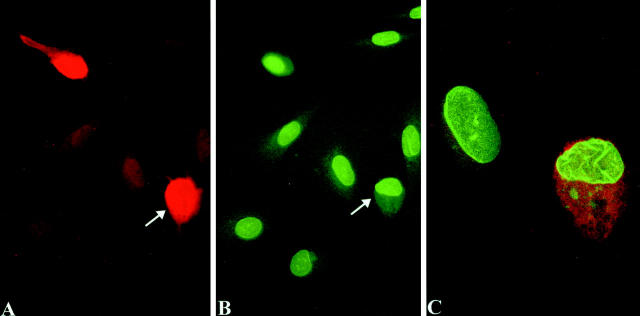

Figure 1.

Lamin immunostaining pattern is unaltered in a cell microinjected 6 hours previously with cascade-blue-labeled dextran (cell marked with an arrow). Only lamin staining is shown. Conventional epifluorescence microscope, final magnification ×1000.

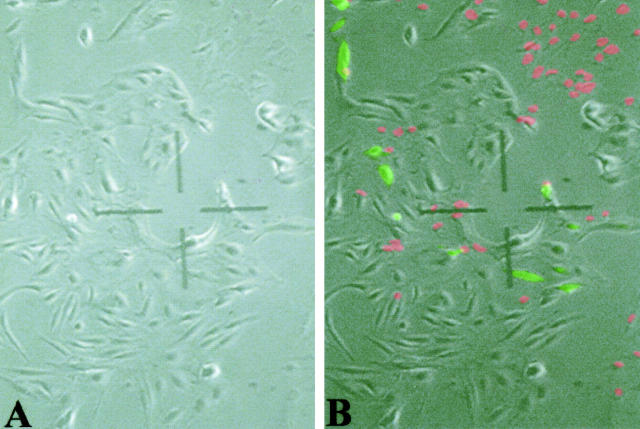

The recovery of microinjected cells following fixation and immunostaining was about 15%, but the range varied stochastically from day to day, without relation to the construct injected. A flattened, shrunken appearance with dark nuclei suggestive of cell death was observed by phase-contrast microscopy in a significant fraction of the cells within about 30 minutes of microinjection. This phenotype seemed to account for most of the non-recovered cells. The remaining cells, corresponding approximately to the total number of cells recovered, regained a normal morphology by phase contrast within minutes of intranuclear microinjection. Addition of ethidium bromide to the media confirmed that the shrunken cells were dead and had lost much of the injected fluorescently labeled dextran. Figure 2 ▶ shows that dead cells (staining red in their chromatin) tend to have a characteristic shrunken, flattened cytoplasm and dark nuclear morphology by phase contrast, whereas residual live cells bearing microinjected fluoresceinated dextran show a normal morphology. To quantify the time-course of cell death, time-lapse phase-contrast photomicroscopy was performed on three occasions using a 37°C-warmed stage over 12 to 18 hours within 30 minutes of microinjection of fluoresceinated dextran. Initial and final fluorescent images were captured to mark the location of microinjected cells and dead cells. Cell death was assessed by ethidium bromide uptake and absent dynamics of the cytoplasm in the time lapse images. Of 65 cells that had been injected and were ultimately found to be dead by ethidium bromide uptake after at least 12 hours, cell death was seen to have occurred in 62 of the cells before the onset of filming. For two cells, it was possible that cell death occurred within the first 20 minutes of filming; for a third cell, cell death may have occurred at about 3 hours of filming. Since microinjected plasmids are reported to be expressed only after about 3 hours, 31,35 virtually no expression would therefore be anticipated in cells that died as a result of microinjection per se.

Figure 2.

Lack of cell recovery after microinjection can be mostly accounted for by an early cell death, associated with a characteristic shrunken appearance by phase contrast microscopy. Corresponding phase contrast (A) and superimposed fluorescein-dextran (green) and ethidium bromide (red) (B) fluorescent images show that microinjected cells that remain viable have a grossly normal morphology, whereas cells that die as a result of microinjection (red) show a characteristic flattened morphology and lose much of the microinjected fluorescent dextran. Final magnification, ×50.

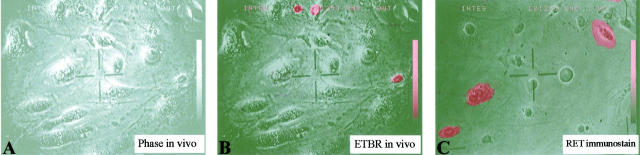

Dead cells appear to wash off the dish during immunostaining. As shown in Figure 3 ▶ , three dead cells detach at the end of 18 hours of in vivo phase-contrast filming, whereas three other viable cells, which had been microinjected with RET/PTC1, remain and express RET. Dead cells are only rarely encountered after microinjection and immunostaining. These cells have a distinctly fragmented nucleus that would not be scored as irregular (Figure 4) ▶ , and as expected, they do not express microinjected plasmids. It is concluded that the microinjection procedure appears to have an acute effect on cell viability, but does not appear to affect cell morphology in cells that survive the procedure. Furthermore, the majority of cells that die as a consequence of microinjection detach during immunostaining, and any remaining dead cells not only do not express injected plasmids but they would not score as showing an irregular nuclear envelope contour. Therefore, nuclear morphology in cells that express plasmids 6 hours or more after microinjection are not anticipated to be affected by the microinjection procedure itself.

Figure 3.

Dead cells tend to detach during immunostaining, while cells expressing microinjected plasmids are viable and do not detach. Phase contrast (A) and superimposed phase contrast and ethidium bromide (B) shows three dead cells in a living culture of normal thyroid culture 12 hours after microinjection of RET/PTC1. Approximately the same field is shown following fixation and immunostaining for RET (C). The three dead cells had detached, and the RET/PTC1-expressing cells (including a binucleated cell) were viable at the time of fixation. Final magnification, ×150.

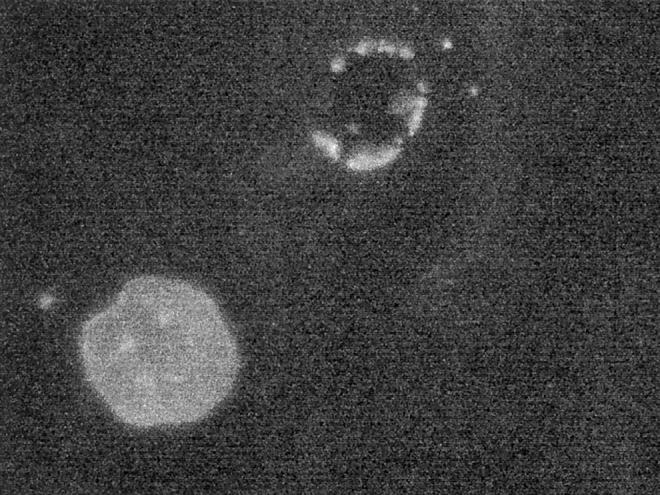

Figure 4.

A rare cell with a fragmented nuclear envelopes (upper right) is encountered that likely died early as a result of the microinjection procedure itself. The appearance is distinctly different from the appearance of viable cells. Only lamin staining is shown. Conventional epifluorescence microscope, final magnification, ×1000.

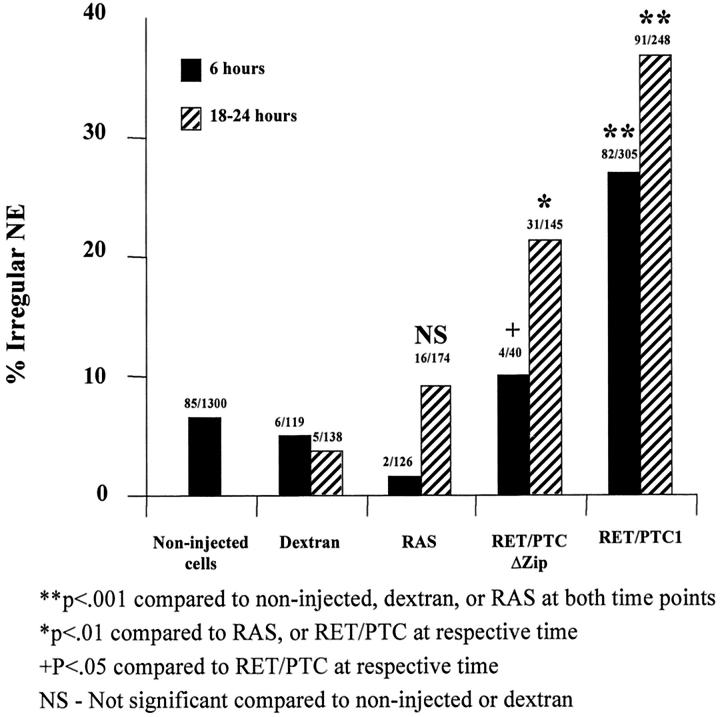

RET/PTC1 Induces NE Irregularity within 6 to 18 Hours

Immunostaining for RET and the hemagglutinin tag of activated RAS is generally strong, with positive staining only seen within the squares in which cells had been injected. Figure 5A and D ▶ show the immunostaining for RET. As expected, 31 virtually all of the surviving cells with fluorescently labeled intranuclear dextran (not shown in Figure 5 ▶ ) express microinjected plasmid DNA by 6 hours. The results of NE contour scoring for the different microinjected materials are summarized in Figure 6 ▶ . RAS, RET/PTC1, and RET/PTC1 Δzip microinjected cells were all scored by an individual who did not know what had been injected or when. An average of ∼6% of non-injected cells, or cells microinjected in their nuclei with dextran or RAS, showed irregular nuclei. The attenuated RET/PTC Δzip gave a 10% rate of irregularity 6 hours after microinjection, which is not statistically different from the controls. Figure 5, A to C ▶ , shows the RET immunostaining and lamin immunostaining of the same field that includes three cells with regular nuclei 6 hours after microinjection of RET/PTC Δzip. In contrast, cells microinjected 6 hours previously with RET/PTC1 showed 27% irregular nuclei, which is significantly higher than the controls. 18 to 24 hours after RET/PTC1 microinjection, an even higher proportion showed an irregular NE (37%). Figure 5, D to F ▶ , shows one cell with an irregular NE 18 hours after RET/PTC1 microinjection. 21% of cells showed irregular nuclear envelopes 18 to 24 hours after RET/PTC1 Δzip microinjection. This 21% proportion is statistically smaller than the 37% proportion of irregularity in RET/PTC1-expressing cells, but statistically larger than the rate of irregularity for any of the other negative controls. The background NE irregularity following microinjection of RET/PTC1 Δzip may relate to the fact that absence of the dimerization domain would only decrease the activation of the kinase by decreasing autophosphorylation: Deletion of the dimerization domain would not decrease catalytic activity of the kinase if it were to become active. In fact, RET/PTC1 Δzip shows diminished but not absent autophosphorylation compared to RET/PTC1 29 predicting that there is a small pool of active RET kinase in the cells expressing RET/PTC1 Δzip.

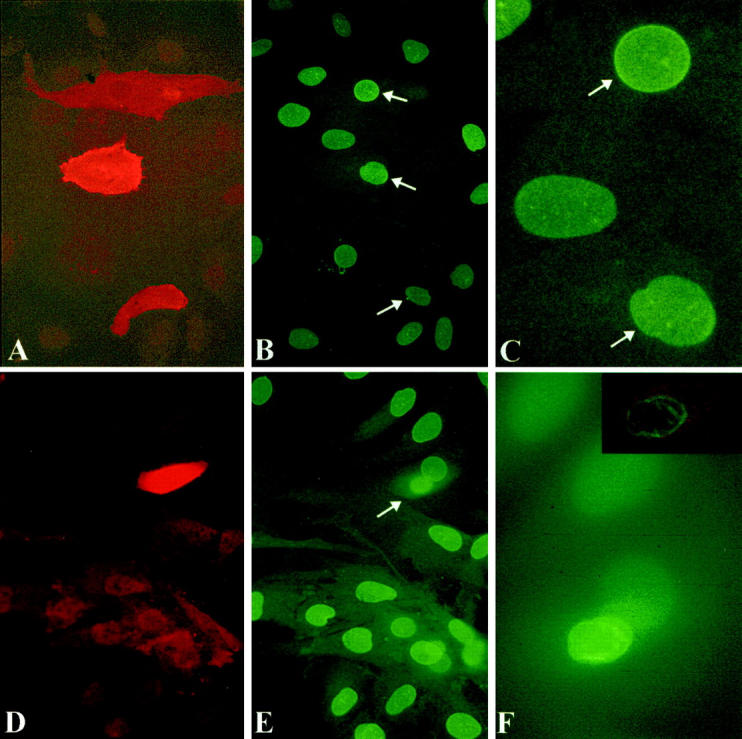

Figure 5.

Microinjection of RET/PTC Δzip (A to C) causes no change in nuclear contour in three cells, whereas microinjection of RET/PTC1 (D to F) induces nuclear envelope irregularity within 18 hours. Anti-RET antibody (red) in A, D, and the inset to F shows unambiguous staining of microinjected cells; B, C, E, and F show the lamin immunostaining of the corresponding fields. The appearance of the three nuclei that had been microinjected with RET/PTC Δzip 6 hours previously (arrows in B) is not different from the surrounding non-injected cells. C: Higher magnification of the upper two cells of B. In contrast, one cell that had been microinjected with RET/PTC1 18 hours previously (D to F) shows an irregular nucleus in the expressing cell. This cell can be seen in E (arrow) to be at a higher plane than the surrounding non-injected cells. F shows the same microinjected cell at higher magnification in focus by conventional epifluorescence and the inset shows the cell by confocal microscopy. Magnifications: A and B, ×300; D and E, ×400; C and F, ×1000.

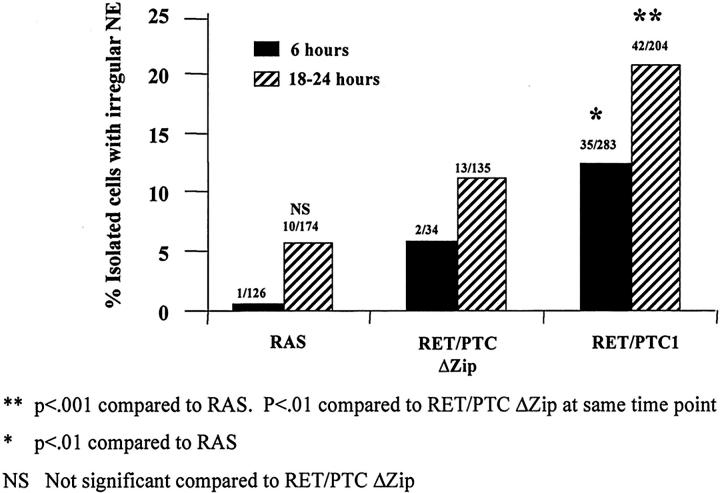

Figure 6.

Nuclear envelope irregularity is induced by RET/PTC1 within 6 hours of microinjection. The proportion of cells (shown above each of the histograms) with NE irregularity at 6 and 18 to 24 hours after microinjection of RET/PTC1 is significantly higher (P < 0.001) than non-injected cells, dextran-injected cells, or RAS-injected cells. 18 hours after the microinjection of RET/PTC Δzip, significantly fewer cells (P < 0.01) have nuclear envelope irregularity than cells microinjected 18 hours previously with RET/PTC1, but significantly more than non-injected, dextran-injected, or RAS-injected cells. Six hours after RET/PTC Δzip microinjection, the proportion of cells with NE irregularity is statistically (P < 0.05) less than at 6 hours after RET/PTC1 microinjection. Irregularity after RAS microinjection is not significantly (NS) different from controls.

Mitosis Is Not Required for Expression of an Irregular NE after Microinjection of RET/PTC

As data began to show development of NE irregularity within hours of microinjecting RET/PTC1, the possibility was assessed that a postmitotic nuclear envelope reassembly was not required for this phenotype. Cells were deliberately microinjected relatively far apart from each other to see if irregular cells appeared as postmitotic doublets, and it was noted whether labeled mitotic cells were present. If the cells did not pass through mitosis, it was expected that single cells expressing the microinjected constructs would be found, and the nearest neighbor would be a non-expressing cell. Figure 7 ▶ shows two cells microinjected 6 hours previously with RET/PTC1 separated by two non-injected cells; both cells expressing RET/PTC1 show NE irregularity (one of the two microinjected cells, indicated with an arrow, is shown at higher magnification in 7C). Figure 8 ▶ summarizes the blinded scoring of NE contour in expressing cells that were not next to another cell that expressed the construct, as if a mitosis had not occurred (eg, as shown in Figure 5, D to F ▶ , and Figure 7 ▶ ). Every result from Figure 8 ▶ is incorporated into the totals shown in Figure 6 ▶ , but not every cell scored for Figure 8 ▶ could be scored as to whether or not it was next to an expressing cell, and so the totals are not the same between these two figures. Only rare cells expressing microinjected constructs were possible post-telophase doublets, and no mitotic figures were seen. The proportion of irregular nuclei in single cells following RET/PTC1 microinjection was significantly higher than the proportion of irregular nuclei following RAS injections, or following RET/PTC1 Δzip injections at the 6- and 18- to 24-hour time-points (Figure 8) ▶ .

Figure 7.

No evidence for an intervening mitosis can be seen in two cells with irregular nuclei 6 hours after microinjection of RET/PTC1. The two cells are separated from each other by two other non-injected cells. A: Anti-RET immunostain. B: Lamin immunostaining of the same field. C: Confocal micrograph of the same cell marked with an arrow in B. The confocal micrograph shows superimposed RET immunostain product (red) and lamin (green) staining and it shows with better resolution the NE irregularity consisting of numerous longitudinal folds. A and B: Conventional epifluorescence micrographs at ×400 final magnification. C: Confocal image at ×1000 final magnification.

Figure 8.

Nuclear envelope irregularity occurs in non-mitotic cells that appear singly, rather than in postmitotic doublets. To try to eliminate scoring of a cell that could have passed through mitosis, a subset of the results shown in Figure 1 was scored as to whether an expressing cell was next to another expressing cell. NE irregularity 18 hours after RET/PTC1 microinjection in single cells is statistically higher than RAS or RET/PTC Δzip at either time point, and at 6 hours after RET/PTC1 microinjection, the rate of single cells with irregular NE contours is significantly higher than RAS at the 18-hour time-point.

Other Observations

Cells expressing NE irregularity often round up at a plane higher than the surrounding cells. For example, in Figures 5 and 7 ▶ , the expressing cells with irregular NEs are at a focal plane farther from the substrate than the non-injected cells. In retrospect this same phenotype was evident in previous work 24 and appears to correspond to the phenotype of “fenestrated colonies” first described by Jane Bond et al, 28 in which the RET/PTC-expressing cells are more refractile and form looser contacts with neighboring cells, as observed by time-lapse phase-contrast microscopy.

Discussion

Postmitotic NE Re-Assembly Is Not Required

The results support a model in which RET/PTC1 signals rapidly to induce the NE phenotype characteristic of papillary thyroid carcinoma, without a requirement for an intervening postmitotic NE re-assembly. NE irregularity cannot be ascribed to microinjection per se, since dextran injections and two other negative controls did not cause the same extent of irregularity. The possibility of a toxic effect is ruled out by the following observations: cell death in microinjected cells probably occurs before the first time-point studied, most dead cells apparently detach from the plate or at least do not appear to express the microinjected plasmids, and the nuclear appearance of dead cells is distinctly different from the phenotype we observed following RET/PTC1 microinjection. All of the constructs were prepared with an endotoxin-free procedure, and a toxic effect of the plasmids would not explain the significant increase in irregularity observed between 6 and 18 to 24 hours following RET/PTC1 injection. Intranuclear injection has been used previously to introduce plasmids to study the interphase assembly of NE proteins starting 3 hours after microinjection. 35 Surprisingly, nuclear pore function is apparently normal within 30 to 45 minutes following intranuclear microinjections of various proteins. 32-34 The microinjection technique is useful for studying nuclear organization because of the relatively tight control over the initiation of expression of injected plasmids, and ability to express genes in specific cells that are resistant to transfections.

The NE is known to be somewhat irregular immediately after it is reassembled on postmitotic chromosomes. 35 However, if the observed irregularity were due to capture of cells in the early postmitotic time following a mitogenic effect of RET/PTC1, irregular NE would also be expected following oncogenic RAS microinjection since RAS is a known mitogen for thyrocytes (reviewed in 26 ). Our experience is that the doubling time of either normal human thyroid cells or human thyroid cells expressing RET/PTC is about 48 hours (unpublished observations). The rate of irregularity 18 hours after injecting RET/PTC1 is similar to the rate of irregularity scored with the same criteria 7 to 14 days after retroviral expression of RET/PTC1, 24 suggesting that this phenotype develops to completion before a majority of the cells could have even progressed through a complete cell cycle. Further evidence against a requirement for postmitotic NE re-assembly is that postmitotic cells are known to have relatively condensed chromatin early after telophase; 13 however, NE irregularity was not scored in cells with the condensed appearance of post-telophase cells.

As previously noted, not all cells expressing RET/PTC1 score as showing NE irregularity. 24 Possible reasons for this include an arbitrary (but reproducible) cut-off for scoring NE irregularity, and heterogeneity in these primary cultures of normal human thyroid cells. Not every cell in a human papillary thyroid carcinoma shows nuclear irregularity; perhaps it is the tendency to lose NE regularity that is a better description of the phenotype.

Dynamic Forces Must Act on the NE in Interphase

It therefore appears that dynamic forces deform the NE during interphase as a downstream event in normal human thyroid cells, occurring within hours of RET/PTC1 activation. We cannot exclude the possibility that postmitotic nuclear envelope re-assembly is also abnormal. Since RET/PTC1 appears to be recruited to the cytoplasmic membrane for docking with Shc or FRS-2, 36,37 there may be a diffusible signal downstream of RET/PTC1 that can effect the change in NE contour. Intranuclear RET/PTC has not been reported. Our studies do not resolve its precise subcellular localization. 24

What types of dynamic forces could deform the NE? No gross alteration in the amounts or electrophoretic mobilities of many of the major nuclear lamina proteins have been found in human papillary thyroid carcinomas, and the distribution of these nuclear lamina proteins are unaltered with respect to the characteristic nuclear grooves and inclusions. 3 These results give the impression of a passive distortion of an otherwise normal NE by exogenous forces directed at right angles from the nucleus or cytoplasm (discussed in 3 ). The force(s) that distort the nuclear envelop in interphase seem unlikely to originate from within the NE itself since a rounded NE of normal thyroid cells could not generate much leverage. The potential candidates for exerting force that deforms the interphase NE are an intranuclear/chromatin-based force, and cytoskeletal forces exerted by actin, tubulin, or intermediate filaments.

Potential Chromatin-Based Forces Acting on the NE

Almost nothing is known about force-generation by chromatin that could mediate NE irregularity. After terminal differentiation of myeloid cells, neutrophils develop their characteristic nuclear lobulation over a period of days. This process is accompanied by expression of specific chromatin-associated proteins, and a concomitant large-scale reorganization of heterochromatin. 38 Intranuclear actin has been shown to exist, but its role in nuclear physiology is still poorly understood. 39 Cell lines with P21 or P53 mutations develop nuclear lobulations after mutational stress. 40 Development of the lobulations does not require postmitotic NE re-assembly but the mechanisms are not understood. 40 NE evaginations, or “buds” develop during S phase in cells with gene amplification. 41 The appearance of “lobulations” and “buds” differ from the appearance of nuclear grooves and the folds that were observed in this study. Deep, thin, tubular invaginations of NE with included nuclear pores have been shown to traverse an otherwise rounded nucleus of many normal and transformed cell types, and these tubular invaginations undergo dynamic motions during interphase. 42 Evidence for interphase intranuclear motion of large chromosome domains with respect to the NE have begun to be described, 17,43 and it is possible that the NE provides a fulcrum for some of these dynamics.

Potential Cytoplasmic-Based Forces Acting on the NE

The apparent rounding-up of RET/PTC1-expressing cells predicts cytoskeletal reorganization. 24,28 Blunt movements of the interphase NE can be visualized in living cells when the cytoskeleton is physically manipulated, 44 demonstrating that the cytoskeleton has mechanical connections to the nucleus. Recent evidence suggests that microtubules physically indent and pierce the NE just before the onset of mitosis. 45,46 Vimentin knock-out fibroblasts have more irregular NE contours than corresponding vimentin-replete fibroblasts 47 (see also 48 ). Prominent bundles of intermediate filaments have been described in the nuclear folds in an adenocarcinoma cell line. 49 The nature of NE receptors for cytoskeletal connections is unknown, but nuclear pores would be the best candidates since no outer NE-specific proteins are known. It should be straightforward to test the relative contributions of the actin, tubulin, and intermediate filament classes of cytoskeletal elements to the dynamic development of nuclear irregularity during interphase, and the ability to induce NE dynamics could facilitate discovery of potential cytoskeletal binding sites on the NE. There may be no relation of this putative perinuclear cytoskeletal physiology to the known dynamics of the peripheral cytoskeleton, since RAS does not induce irregularity, 24,27 yet RAS is known to induce peripheral cytoskeletal dynamics during interphase. 50

How General is the Mechanism of NE Irregularity Observed Here, and How Is it Related to Cancer?

Neither phase-contrast microscopy nor differential-interference contrast microscopy is able to show the complexities of NE contour in living cells, especially if their cytoplasm is rounded up. Direct visualization of the dynamics of the NE in interphase in cancer cells requires confocal time-lapse microscopy of cells expressing fluorescently labeled nuclear lamina proteins. Therefore, the possibility of large-scale NE deformations during interphase could easily have been overlooked. Previous time-lapse studies of fluorescently labeled NE are restricted to a few non-tumorigenic cell lines with generally round NEs, and these studies have shown only relatively blunt and shallow deflections of the outer contour of the NE. 35,51 The present results suggest that much more dynamic interphase deformations of the NE can occur in cancer cells. We recently observed significant inward and outward sharp deflections greater than 1 μm of the interphase NE in prostate cancer cells occurring within a time-span of less than 5 minutes (Vanguri et al, manuscript in preparation).

Not all cancers show NE irregularity, and conversely, some normal cells (eg, centrocytic lymphocytes) show prominent NE irregularity. Nevertheless, we speculate that within certain cellular contexts, NE irregularity will be found to be functionally significant to the cancer cell since NE irregularity is “conserved in evolution” (during tumor progression). In fact, loss of regular nuclear contour has adverse prognostic significance for cancers of the head and neck, 52 breast, 53 kidney, 54 bladder, 55 prostate, 56-58 and ovary, 59,60 and it predicts the development of squamous intra-epithelial lesions in patients with atypical squamous cells of the cervix. 61 It is possible that the mechanism of NE irregularity downstream of RET/PTC will have a general importance across histogenetic boundaries. In any case, RET/PTC activation in human thyroid cells appears to be an excellent model for inducing NE irregularity relevant to cancer.

When a pathologist observes NE irregularity in pancreatic, lung, prostate, or breast cancers, it now seems possible that the nuclei had been literally writhing within their cytoplasm at the moment they were fixed. Viewing NE irregularity as a dynamic process, mediated by an oncogene, should open the door to identifying the force-generating components of the cell that drive this cancer-associated pathophysiology.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Andrew H. Fischer, Department of Pathology and Cell Biology, University of Massachusetts, H2–466, 55 Lake Avenue North, Worcester, MA 01655. E-mail: Fischa01@ummhc.org.

References

- 1.Aitchison JD, Rout MP: A tense time for the nuclear envelope. Cell 2002, 108:301-304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hutchison CJ, Alvarez-Reyes M, Vaughan OA: Lamins in disease: why do ubiquitously expressed nuclear envelope proteins give rise to tissue-specific disease phenotypes? J Cell Sci 2001, 114:9-19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fischer AH, Taysavang P, Weber C, Wilson K: Nuclear envelope organization in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Histol Histopathol 2001, 16:1-14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson KL: The nuclear envelope, muscular dystrophy, and gene expression. Trends Cell Biol 2000, 10:125-129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Worman HJ, Courvalin JC: The inner nuclear membrane. J Membr Biol 2000, 177:1-11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moir RD, Spann TP, Goldman RD: The dynamic properties and possible functions of nuclear lamins. Int Rev Cytol 1995, 162B:141-182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ryan KJ, Wente SR: The nuclear pore complex: a protein machine bridging the nucleus and cytoplasm. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2000, 12:361-371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Newport JW, Wilson KL, Dunphy WG: A lamin-independent pathway for nuclear envelope assembly. J Cell Biol 1990, 111:2247-2259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spann TP, Moir RD, Goldman AE, Stick R, Goldman RD: Disruption of nuclear lamin organization alters the distribution of replication factors and inhibits DNA synthesis. J Cell Biol 1997, 136:1201-1212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldberg M, Jenkins H, Allen T, Whitfield WG, Hutchison CJ: Xenopus lamin B3 has a direct role in the assembly of a replication-competent nucleus: evidence from cell-free egg extracts. J Cell Sci 1995, 108:3451-3461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hutchison CJ, Bridger JM, Cox LS, Kill IR: Weaving a pattern from disparate threads: lamin function in nuclear assembly and DNA replication. Journal of Cell Science 1994, 107:3259-3269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang L, Guan T, Gerace L: Lamin-binding fragment of LAP2 inhibits increase in nuclear volume during the cell cycle and progression into S phase. J Cell Biol 1997, 139:1077-1087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gant TM, Harris CA, Wilson KL: Roles of LAP2 proteins in nuclear assembly and DNA replication: truncated LAP2B proteins alter lamina assembly, envelope formation, nuclear size, and DNA replication efficiency in Xenopus laevis extracts. J Cell Biol 1999, 144:1083-1096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moir RD, Spann TP, Herrmann H, Goldman RD: Disruption of nuclear lamin organization blocks the elongation phase of DNA replication. J Cell Biol 2000, 149:1179-1192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ye Q, Callebaut I, Pezhman A, Courvalin JC, Worman HJ: Domain-specific interactions of human HP1-type chromodomain proteins and inner nuclear membrane protein LBR. J Biol Chem 1997, 272:14983-14989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cockell M, Gasser SM: Nuclear compartments and gene regulation. Curr Opin Genet Dev 1999, 9:199-205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kosak ST, Skok JA, Medina KL, Riblet R, Le Beau MM, Fisher AG, Singh H: Subnuclear compartmentalization of immunoglobulin loci during lymphocyte development. Science 2002, 296:158-162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matioli GT: Mechanics of nucleocytoplasmic exchanges mediated by vertebrates’ nuclear pore complex. Med Hypotheses 2000, 54:30-32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gant TM, Wilson KL: Nuclear assembly. Ann Rev Cell Dev Biol 1997, 13:669-695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosai J, Carcangiu ML, Delellis RA: Tumors of the Thyroid Gland. 1992:pp 343 Armed Forces Institute of Pathology Washington

- 21.Grieco M, Santoro M, Berlingieri MT, Melillo RM, Donghi R, Bongarzone I, Pierotti MA, Della Porta G, Fusco A, Vecchio G: PTC is a novel rearranged form of the ret proto-oncogene and is frequently detected in vivo in human thyroid papillary carcinomas. Cell 1990, 60:557-563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Santoro M, Sabino N, Ishizaka Y, Ushijima T, Carlomagno F, Cerrato A, Grieco M, Battaglia C, Martelli ML, Paulin C, Fabien N, Sugimura T, Fusco A, Nagao M: Involvement of RET oncogene in human tumours: specificity of RET activation to thyroid tumours. Br J Cancer 1993, 68:460-464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Viglietto G, Chiappetta G, Martinez-Tello FJ, Fukunaga FH, Tallini G, Rigopoulou D, Visconti R, Mastro A, Santoro M, Fusco A: RET/PTC oncogene activation is an early event in thyroid carcinogenesis. Oncogene 1995, 11:1207-1210 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fischer AH, Bond JA, Taysavang P, Battles OE, Wynford-Thomas D: Papillary thyroid carcinoma oncogene (RET/PTC) alters the nuclear envelope and chromatin structure. Am J Pathol 1998, 153:1443-1450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fusco A, Chiappetta G, Hui P, Garcia-Rostan G, Golden L, Kinder BK, Dillon DA, Giuliano A, Cirafici AM, Santoro M, Rosai J, Tallini G: Assessment of RET/PTC oncogene activation and clonality in thyroid nodules with incomplete morphological evidence of papillary carcinoma: a search for the early precursors of papillary cancer. Am J Pathol 2002, 160:2157-2167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wynford-Thomas D: Origin and progression of thyroid epithelial tumours: cellular and molecular mechanisms. Horm Res 1997, 47:145-157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fischer AH, Chaddee DN, Wright JA, Gansler TS, Davie JR: Ras-associated nuclear structural change appears functionally significant and independent of the mitotic signaling pathway. J Cell Biochem 1998, 70:130-140 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bond JA, Wyllie FS, Rowson J, Radulescu A, Wynford-Thomas D: In vitro reconstruction of tumour initiation in a human epithelium. Oncogene 1994, 9:281-290 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xing S, Furminger TL, Tong Q, Jhiang SM: Signal transduction pathways activated by RET oncoproteins in PC12 pheochromocytoma cells. J Biol Chem 1998, 273:4909-4914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khosravi-Far R, White MA, Westwick JK, Solski PA, Chrzanowska-Wodnicka M, Van Aelst L, Wigler MH, Der CJ: Oncogenic Ras activation of Raf/mitogen-activated protein kinase-independent pathways is sufficient to cause tumorigenic transformation. Mol Cell Biol 1996, 16:3923-3933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bar-Sagi D: Mammalian cell microinjection assay. Methods Enzymol 1995, 255:436-442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosorius O, Reichart B, Kratzer F, Heger P, Dabauvalle MC, Hauber J: Nuclear pore localization and nucleocytoplasmic transport of eIF-5A: evidence for direct interaction with the export receptor CRM1. J Cell Sci 1999, 112:2369-2380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guan T, Kehlenbach RH, Schirmer EC, Kehlenbach A, Fan F, Clurman BE, Arnheim N, Gerace L: Nup50, a nucleoplasmically oriented nucleoporin with a role in nuclear protein export. Mol Cell Biol 2000, 20:5619-5630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iovine MK, Wente SR: A nuclear export signal in Kap95p is required for both recycling the import factor and interaction with the nucleoporin GLFG repeat regions of Nup116p and Nup100p. J Cell Biol 1997, 137:797-811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ellenberg J, Siggia ED, Moreira JE, Smith CL, Presley JF, Worman HJ, Lippincott-Schwartz J: Nuclear membrane dynamics and reassembly in living cells: targeting of an inner nuclear membrane protein in interphase and mitosis. J Cell Biol 1997, 138:1193-1206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Melillo RM, Santoro M, Ong SH, Billaud M, Fusco A, Hadari YR, Schlessinger J, Lax I: Docking protein FRS2 links the protein tyrosine kinase RET and its oncogenic forms with the mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling cascade. Mol Cell Biol 2001, 21:4177-4187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mercalli E, Ghizzoni S, Arighi E, Alberti L, Sangregorio R, Radice MT, Gishizky ML, Pierotti MA, Borrello MG: Key role of Shc signaling in the transforming pathway triggered by Ret/ptc2 oncoprotein. Oncogene 2001, 20:3475-3485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grigoryev SA, Woodcock CL: Chromatin structure in granulocytes. A link between tight compaction and accumulation of a heterochromatin-associated protein (MENT). J Biol Chem 1998, 273:3082-3089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rando OJ, Zhao K, Crabtree GR: Searching for a function for nuclear actin. Trends Cell Biol 2000, 10:92-97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Waldman T, Lengauer C, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B: Uncoupling of S phase and mitosis induced by anticancer agents in cells lacking p21. Nature 1996, 381:713-716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shimizu N, Itoh N, Utiyama H, Wahl GM: Selective entrapment of extrachromosomally amplified DNA by nuclear budding and micronucleation during S phase. J Cell Biol 1998, 140:1307-1320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fricker M, Hollinshead M, White N, Vaux D: Interphase nuclei of many mammalian cell types contain deep, dynamic, tubular membrane-bound invaginations of the nuclear envelope. J Cell Biol 1997, 136:531-544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Belmont AS: Visualizing chromosome dynamics with GFP. Trends Cell Biol 2001, 11:250-257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maniotis AJ, Chen CS, Ingber DE: Demonstration of mechanical connections between integrins, cytoskeletal filaments, and nucleoplasm that stabilize nuclear structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1997, 94:849-854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Salina D, Bodoor K, Eckley DM, Schroer TA, Rattner JB, Burke B: Cytoplasmic dynein as a facilitator of nuclear envelope breakdown. Cell 2002, 108:97-107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Beaudouin J, Gerlich D, Daigle N, Eils R, Ellenberg J: Nuclear envelope breakdown proceeds by microtubule-induced tearing of the lamina. Cell 2002, 108:83-96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sarria AJ, Lieber JG, Nordeen SK, Evans RM: The presence or absence of a vimentin-type intermediate filament network affects the shape of the nucleus in human SW-13 cells. J Cell Sci 1994, 107:1593-1607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Holwell TA, Schweitzer SC, Evans RM: Tetracycline-regulated expression of vimentin in fibroblasts derived from vimentin null mice. J Cell Sci 1997, 110:1947-1956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kamei H: Relationship of nuclear invaginations to perinuclear rings composed of intermediate filaments in MIA PaCa-2 and some other cells. Cell Struct Funct 1994, 19:123-132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ridley AJ, Paterson HF, Johnston CL, Diekmann D, Hall A: The small GTP-binding protein rac regulates growth factor-induced membrane ruffling. Cell 1992, 70:401-410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Broers JL, Machiels BM, van Eys GJ, Kuijpers HJ, Manders EM, van Driel R, Ramaekers FC: Dynamics of the nuclear lamina as monitored by GFP-tagged A-type lamins. J Cell Sci 1999, 112:3463-3475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Giardina C, Caniglia DM, D’Aprile M, Lettini T, Serio G, Cipriani T, Ricco R, Pesce Delfino V: Nuclear morphometry in squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the tongue. Eur J Cancer B Oral Oncol 1996, 32B:91-96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Seker H, Odetayo MO, Petrovic D, Naguib RN, Bartoli C, Alasio L, Lakshmi MS, Sherbet GV: Assessment of nodal involvement and survival analysis in breast cancer patients using image cytometric data: statistical, neural network and fuzzy approaches. Anticancer Research 2002, 22:433-438 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nativ O, Sabo E, Bejar J, Halachmi S, Moskovitz B, Miselevich I: A comparison between histological grade and nuclear morphometry for predicting the clinical outcome of localized renal cell carcinoma. Br J Urol 1996, 78:33-38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Borland RN, Partin AW, Epstein JI, Brendler CB: The use of nuclear morphometry in predicting recurrence of transitional cell carcinoma. J Urol 1993, 149:272-275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Epstein JI, Berry SJ, Eggleston JC: Nuclear roundness factor: a predictor of progression in untreated Stage A2 prostate cancer. Cancer 1984, 54:1666-1671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mohler JL, Figlesthaler WM, Zhang XZ, Partin AW, Maygarden SJ: Nuclear shape analysis for the assessment of local invasion and metastases in clinically localized prostate carcinoma. Cancer 1994, 74:2996-3001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Partin AW, Steinberg GD, Pitcock RV, Wu L, Piantadosi S, Coffey DS, Epstein JI: Use of nuclear morphometry, gleason histologic scoring, clinical stage, and age to predict disease-free survival among patients with prostate cancer. Cancer 1992, 70:161-168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu CQ, Sasaki H, Fahey MT, Sakamoto A, Sato S, Tanaka T: Prognostic value of nuclear morphometry in patients with TNM stage T1 ovarian clear cell adenocarcinoma. Br J Cancer 1999, 79:1736-1741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gurley AM, Hidvegi DF, Cajulis RS, Bacus S: Morphologic and morphometric features of low-grade serous tumours of the ovary. Diagn Cytopathol 1994, 11:220-225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ettler HC, Joseph MG, Downing PA, Suskin NG, Wright VC: Atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance: a cytohistological study in a colposcopy clinic. Diagn Cytopathol 1999, 21:211-216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]