Abstract

In this study we measured ΔΨm in single isolated brain mitochondria using rhodamine 123. Mitochondria were attached to coverslips and superfused with K+-based HEPES-buffer medium supplemented with malate and glutamate. In ∼70% of energized mitochondria we observed large amplitude spontaneous fluctuations in ΔΨm with a time course comparable to that observed previously in mitochondria of intact cells. The other 30% of mitochondria maintained a stable ΔΨm. Some of the “stable” mitochondria began to fluctuate spontaneously during the recording period. However, none of the initially fluctuating mitochondria became stable. Upon the removal of substrates from the medium or application of small amounts of Ca2+, rhodamine 123 fluorescence rapidly dropped to background values in fluctuating mitochondria, while nonfluctuating mitochondria depolarized with a delay and often began to fluctuate before complete depolarization. The changes in ΔΨm were not connected to oxidant production since reducing illumination or the addition of antioxidants had no effect on ΔΨm. Fluctuating mitochondria did not lose calcein, nor was there any effect of cyclosporin A on ΔΨm, which ruled out a contribution of permeability transition. We conclude that the fluctuations in ΔΨm reflect an intermediate, unstable state of mitochondria that may lead to or reflect mitochondrial dysfunction.

INTRODUCTION

Mitochondria serve many functions in eukaryotic cells. Perhaps the most important is the generation of adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP) by oxidative phosphorylation. This, along with many mitochondrial carrier-mediated processes, requires an electrochemical potential generated by the electron transport chain (for review see Bernardi, 1999). Thus, normally functioning mitochondria establish a mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) and a pH gradient (ΔpH) which together comprise Δp, the proton motive force that drives ATP synthesis. Processes that dissipate Δp are usually considered harmful to cells, although it can be argued that regulated uncoupling of Δp from ATP synthesis has some beneficial effects (Nicholls, 2001; Skulachev, 1998).

The ΔΨm is typically the more dynamic parameter in the proton motive force. ΔΨm is typically maintained at −150-200 mV in respiring mitochondria and may be dissipated by ATP synthesis, Ca2+ transport, or the activity of other carrier proteins. Perhaps surprisingly, a number of laboratories have recently reported spontaneous changes in ΔΨm in experimental conditions where ΔΨm was monitored in individual mitochondria using fluorescent potential-sensitive dyes. Alterations in ΔΨm detected as transient decreases in dye signals have been reported in neuroblastoma cells (Loew et al., 1993; Fall and Bennett, 1999), astrocytes (Belousov et al., 2001; Buckman and Reynolds, 2001b), cardiomyocytes (Duchen et al., 1998), vascular endothelial cells (Huser and Blatter, 1999), and pancreatic B-cells (Krippeit-Drews et al., 2000). We have also reported a slightly different phenomenon of transient increases in the signal of potential-sensitive dyes in primary cultures of forebrain neurons (Buckman and Reynolds, 2001a). Thus, spontaneous changes in mitochondrial function that are reported by these potential-sensitive dyes appear to be a common property of mitochondria in cells. The fundamental nature of the phenomenon and the mechanisms responsible for changing ΔΨm remain unclear in these cell-based studies, although several laboratories have concluded that mitochondrial permeability transition (MPT) is an important contributor to the depolarizations (De Giorgi et al., 2000; Ichas et al., 1997; Huser et al., 1998).

Isolated mitochondria preparations offer a number of advantages over intact cells, particularly in the ability to manipulate access to substrates, to alter the local environment, and to deliver drugs. Typically these preparations are studied in a cuvette, which is an inherently unsuitable approach to study stochastic phenomena in individual organelles. However, several recent studies have demonstrated the feasibility of immobilizing individual mitochondria to permit imaging studies utilizing isolated mitochondria (Ichas et al., 1997; Huser et al., 1998; Huser and Blatter, 1999; Nakayama et al., 2002). Interestingly, immobilized mitochondria also exhibit spontaneous changes in ΔΨm, suggesting that the mechanism producing this phenomenon can exist in a cell-free environment.

In the present study, we have applied this approach to the study of isolated rat forebrain mitochondria. We provide a quantitative demonstration of a number of different characteristics of this preparation, including the sensitivity to substrate removal, the effects of calcium loading, and the impact of oxidative stress. Interestingly, however, we find no evidence to support the suggestion that spontaneous depolarization of brain mitochondria is mediated by MPT.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

All materials and reagents were purchased through Sigma (St. Louis, MO), unless otherwise specified.

Isolation of mitochondria

All procedures using animals were in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the University of Pittsburgh's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Rat brain mitochondria were isolated from the cortex of male Sprague-Dawley rats using a Percoll gradient method described by Sims (Sims, 1991) with minor modifications. Isolation buffer contained (in mM): mannitol 225, sucrose 75, EDTA 0.5, HEPES 5, 1 mg/mL fatty acid free BSA, pH adjusted to 7.3 with KOH. Brain tissue was homogenized using a glass/glass homogenizer in isolation buffer containing 12% Percoll and carefully layered on the top of a 12%/24%/42% discontinuous gradient of Percoll. After 11 min of centrifugation at 31,000 × g, the mitochondrial fraction was collected from the top of the 42% Percoll layer of the gradient and then washed twice. For the final wash we used isolation buffer where BSA was omitted, and concentration of EDTA was reduced to 0.1 mM. All isolation procedures were carried out at 0–2°C. During experimentation mitochondria were stored on ice at a final concentration of 15–20 mg protein/ml in isolation medium until use. The protein concentration in each preparation was determined by the Biuret method using a plate reader.

Experimental solutions and fluorescence measurements

All imaging experiments were performed at room temperature in KCl-based buffer containing (in mM): KCl 125, K2HPO4 2, HEPES 5, MgCl2 5, EDTA 0.02, malate 5, glutamate 5, pH 7.0. Mitochondria were added to this buffer at final concentration of 0.75–1 mg protein/ml immediately before each experiment. Thirty-one mm glass coverslips were washed with 70% alcohol, then with H2O and dried before use. A small drop (20 μl) of mitochondrial suspension was placed in the middle of the coverslip for 5–7 min. The coverslips with the mitochondrial suspension were carefully placed into a 700 μl perfusion chamber that was then mounted onto a microscope fitted for fluorescence imaging as described below. The mitochondria were perfused at 7 ml/min with KCl buffer; after 1 min of perfusion, mitochondria which had not attached to the coverslip were effectively washed out of the recording chamber. Typically, the density of attached mitochondria was 400,000–500,000 mitochondria per square millimeter. Thus, in a field observed with a 100× objective ∼2000 mitochondria were present.

For ΔΨm measurements, we used the potentiometric probes rhodamine 123 and tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester (Rh123 and TMRM, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) at nonquenching concentrations. Rh123 (200 nM) or TMRM (40 nM) were added to the perfusion buffer 2–3 min before the start of the recording and were present in the perfusion medium during the experiment. No preloading was necessary. To monitor calcein (Molecular Probes) fluorescence within the mitochondria, the mitochondria were loaded with 8 μM calcein AM for 30 min at room temperature, and then placed onto the coverslip as described above. For the fluorescence recording, we used a BX50WI Olympus Optical (Tokyo, Japan) microscope fitted with an Olympus Optical LUM PlanFI 100× water immersion quartz objective. The fluorescence was monitored using excitation light provided by a 75 W xenon lamp-based monochromator (T.I.L.L. Photonics GmbH, Martinsried, Germany), and emitted light was detected using a CCD camera (Orca; Hamamatsu, Shizouka, Japan). For Rh123 or calcein, mitochondria were illuminated with 490 nm, and emitted fluorescence was passed through a 500-nm long-pass dichroic mirror and a 535/25 nm band-pass filter (Omega Optical, Brattleboro, VT). TMRM was excited with a 550-nm light, the signal was passed through a 570-nm long-pass dichroic mirror and collected using a 605/55-nm filter. An excitation exposure time and neutral density filters were chosen to avoid detector saturation during recording and to minimize light exposure. Mitochondria were exposed to light only during image acquisition (<0.5 s per image). Rh123 and TMRM images were acquired every 10 s, whereas calcein images were acquired every 20 s. Fluorescence data were acquired and analyzed using Simple PCI software (Compix, Cranberry, PA). Fluorescence was measured in 100–150 individual mitochondria for each coverslip. Objects smaller then 0.3 μm were not analyzed. Background fluorescence, determined from three or four mitochondrion-free regions of the coverslip, was subtracted from all the signals. All experiments were repeated 4–6 times using mitochondria from different animals.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using Prism 3.0 (Graph Pad Software, San Diego, CA). All the data are presented as mean ± SE. Comparisons were made using Student's t-test, with P values of less than 0.05 taken as significant.

RESULTS

Fig. 1 shows a typical recording of Rh123 fluorescence obtained from individual mitochondria. Comparing phase contrast (DIC) and fluorescence images, we observed fluorescence in ∼70% of mitochondria attached to the coverslip (Fig. 1 A). Nonfluorescent mitochondria were presumably already depolarized. Since a small nonquenching Rh123 concentration (200 nM) was used, the increase in fluorescence intensity reflected an increase in ΔΨm (Nicholls and Ward, 2000). In response to mitochondrial depolarization caused by either application of mitochondrial uncoupler carbonyl cyanide p-trifluoro-methoxyphenyl hydrazone (FCCP, 250 nM) or by removal of respiratory substrates from the perfusion medium, the fluorescence of Rh123 dropped to background levels without an initial increase, confirming that Rh123 was not quenched (see Fig. 2 A). Fig. 1 B shows examples of the different patterns of changes in ΔΨm observed in individual mitochondria. About 30% of the energized mitochondria maintained a stable ΔΨm, which was rapidly dissipated after addition of FCCP (Fig. 2 A) or spontaneously during experiment (Fig.1 B, trace 1). The remaining 70% of mitochondria showed large amplitude spontaneous fluctuations in ΔΨm, with maximal fluorescence comparable with that in “stable” mitochondria and minima near background levels (Fig.1 B, traces 3–5). Some nonfluctuating mitochondria began to fluctuate spontaneously during the recording period. However, none of the initially fluctuating mitochondria became stable. Fig. 1 B shows that the mean fluorescence of Rh123 gradually decreased during the time of recording.

FIGURE 1.

Examples of characteristic changes in Rh123 fluorescence in single mitochondria. (A) Representative DIC image and fluorescent images taken at different time points illustrating spontaneous ΔΨm fluctuations. (B) The plots show different patterns of spontaneous changes in Rh123 fluorescence in five individual mitochondria from panel A. Mitochondria 1 and 2 would be considered nonfluctuating, whereas 3–5 show various characteristics of individual mitochondria with fluctuating ΔΨm.

FIGURE 2.

Time course of the mitochondrial depolarization in the response to removal of substrates and addition of Ca2+. (A) Changes in Rh123 fluorescence in nonfluctuating (i), fluctuating (ii), and initially nonfluctuating (iii) individual mitochondria. (B) Summarized data of the single experiment presented in A, showing the rate of depolarization in fluctuating compared to nonfluctuating mitochondria. The time of the beginning of the application of substrate-free medium was defined as 0. The percentage of polarized mitochondria was calculated from 150 individual mitochondria; mitochondria that had an Rh123 fluorescence level less than four units were determined as depolarized. These results are representative of four additional experiments.

To characterize the dynamics of ΔΨm, three parameters were analyzed: a mean Rh123 fluorescence, a percentage of fluctuating mitochondria, and a frequency of fluctuations. All of those parameters were measured in the beginning (first 1–3 min) and at the end (12–15 min) of each experiment. We calculated the number of fluctuations using a custom macro written in Visual Basic for Microsoft Excel. Rapid decreases or increases in fluorescence with a minimal amplitude of 10 fluorescence units were counted as a single event. Thus, the mitochondrion presented in Fig. 1 B, trace 4, had two fluctuations during the first 180 s and four fluctuations between 720 and 900 s of the recording. Loss of fluorescence without recovery (as shown on Fig.1 B, trace 1) was not considered as an event. We noted that Rh123 fluorescence intensity varied between preparations (compare Fig. 1 to Fig. 2, for example). Collectively, there was an overall decrease in mean Rh123 fluorescence over the course of the recording, and an increase in the frequency of fluctuations. The characteristics of the spontaneous fluctuations in ΔΨm were similar when using TMRM to report membrane potential to those seen with Rh123 (data not shown).

Characteristics of ΔΨm fluctuations

In the next series of experiments, mitochondria were deenergized by deprivation of substrates. After the removal of substrates, mitochondria maintained ΔΨm for 1.5–3 min, and then depolarized. As illustrated in Fig. 2 A, where the nonfluctuating (panel Ai) and fluctuating (panel Aii) mitochondria are shown separately, stable mitochondria depolarized with a characteristic delay compared with fluctuating mitochondria. Indeed, some nonfluctuating mitochondria did not completely depolarize even after 10 min of substrate deprivation. Interestingly, most of the nonfluctuating and all of the fluctuating mitochondria lost ΔΨm abruptly in substrate-free buffer, although the delay before loss of ΔΨm was variable. This would be consistent with the loss of ΔΨm requiring the activation of an explicit conductance, rather than as a slow leak of protons in the absence of ongoing proton extrusion. The results of this experiment are summarized on Fig. 2 B, which shows the percentage of mitochondria remaining polarized after substrate removal as a function of time. After 3 min of substrate-free medium, more then 80% of mitochondria in both groups remained polarized. However, by 4 min all fluctuating mitochondria had lost ΔΨm, whereas 75% of nonfluctuating mitochondria still remained polarized. Qualitatively similar results were obtained in four other experiments.

Similar patterns of changes in ΔΨm were observed in the next experiment, when mitochondria were exposed to Ca2+. In these experiments 35 μM of Ca2+ was added to the buffer containing 20 μM EDTA, which should result in a free Ca2+ concentration of ∼15μM. Fig. 3 B presents the data of one experiment, in which 150 individual mitochondria were analyzed. By the time all of the fluctuating mitochondria lost ΔΨm, only 50% of the nonfluctuating mitochondria were fully depolarized. We also observed a subpopulation of initially nonfluctuating mitochondria which began to fluctuate in response to Ca2+ or substrate removal before they depolarized completely (Figs. 2 Aiii and 3 Aiii). The overall pattern of ΔΨm behavior, after segregation into fluctuating and nonfluctuating populations, is illustrated in Fig. 3 A.

FIGURE 3.

The effects of Ca2+ on ΔΨm in individual mitochondria. A total of 35 μM Ca2+ was added to the normal 20 μM EDTA-containing superfusate, yielding a free calcium concentration of ∼15μM. (A) Each panel shows separately nonfluctuating (i), fluctuating (ii), and initially nonfluctuating (iii) individual mitochondria. (B) Percentage of mitochondria remaining polarized shown as a function of time after Ca2+ application. Traces from individual mitochondria were segregated into fluctuating and nonfluctuating based on the Rh123 signal before calcium application. The time of the beginning of the application of substrate-free medium was defined as 0. These curves represent the mean of 200 individual mitochondria from the same field, and are representative of five additional experiments.

These data show that mitochondria which did not initially show spontaneous changes in ΔΨm were more resistant to challenges like substrate deprivation or Ca2+ loading. This suggests that the fluctuation in ΔΨm may be an intermediate state between stable, fully coupled mitochondria and damaged organelles that are fully depolarized.

The effects of oxidative stress

Several rhodamine-based ΔΨm probes produce singlet oxygen upon illumination (Bunting, 1992). It is well established that oxidative stress can compromise mitochondrial functions (Zhang et al., 1990). In addition, oxidation of mitochondrial thiol groups together with Ca2+ exposure may trigger MPT activation in isolated mitochondria (Chernyak and Bernardi, 1996), which could plausibly explain the spontaneous depolarizations. We first investigated whether the loss of Rh123 signal or the increase in fluctuation frequency was a consequence of illumination (and presumably the generation of singlet oxygen). Mitochondria were attached to the coverslip in two different regions located as far as possible from each other. Then we recorded the Rh123 fluorescence only from one field, which was selectively illuminated, while the other remained in the dark. Fig. 4 A shows Rh123 fluorescence in the mitochondria illuminated normally (field a) at the beginning and at the end of a 14-min recording period, and a second field from the same coverslip that was not illuminated until the very end of the experiment (field b). This experiment clearly demonstrates that the intensity of the fluorescence and frequency of fluctuations in mitochondria at the end of the recording period was the same in both fields regardless of light exposure (Fig. 4 B). Data from several experiments of this nature are provided in Fig. 4, C and D.

FIGURE 4.

Effect of illumination on ΔΨm in single isolated mitochondria. (A) Images of Rh123 fluorescence in the two different fields of the coverslip with the attached mitochondria. The mitochondria in panels a were subjected to the normal illumination, whereas the mitochondria in panel b were illuminated only at the end of the experiment. (B) The average Rh123 fluorescence of 150 individual mitochondria from each field shown in the previous panel. Panels A and B are from a single experiment that was repeated four additional times with similar results. (C and D) Mean Rh123 fluorescence and the frequency of the fluctuations, respectively, were not significantly different in the mitochondria from field a and b when they were measured at the closed time points. The data in C and D represent the mean ± SE of five experiments.

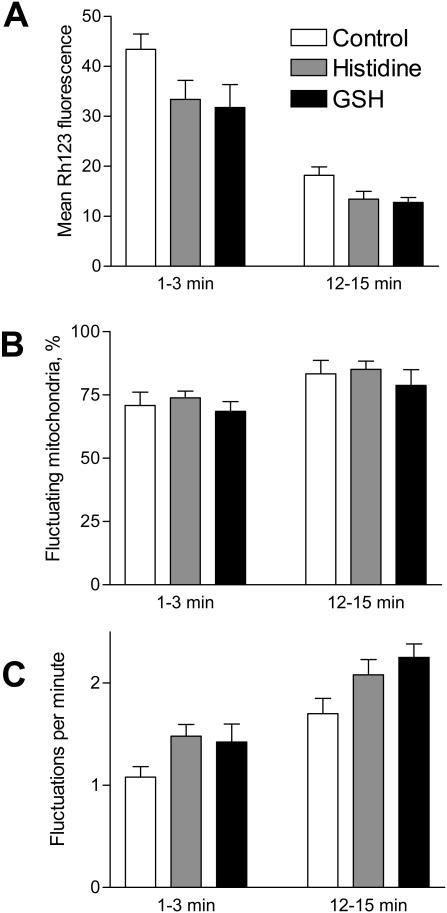

We also examined the effect of ROS scavengers on the changes in mitochondrial ΔΨm. Fig. 5 illustrates that neither the singlet oxygen scavenger histidine nor glutathione (GSH) significantly altered any of the ΔΨm parameters. These results argue that the gradual depolarization of mitochondria and the enhancement of spontaneous fluctuations of ΔΨm during the recording period were not the immediate consequence of oxidative damage.

FIGURE 5.

Effect of antioxidants on ΔΨm. A scavenger of singlet oxygen histidine (300 μM) or glutathione (GSH, 5 mM) did not have any effect on ΔΨm. All parameters (mean Rh123 fluorescence, percentage of blinking mitochondria, and frequency of fluctuations) were measured at the beginning (1–3 min) and at the end (12–15 min) of the experiment. The antioxidants were added to the perfusion medium for 2 min before the start of the recording and were present for the entire experiment. The data represent the mean ± SE of five experiments.

A role for mitochondrial permeability transition

Most studies of spontaneous changes in ΔΨm have concluded that the MPT plays a critical role (Ichas et al., 1997; Fall and Bennett, 1999; Huser et al., 1998; Huser and Blatter, 1999; Nakayama et al., 2002). We therefore performed experiments to determine whether the spontaneous changes in ΔΨm could be attributed to a change in the permeability of the inner mitochondrial membrane associated with MPT. Activation of MPT renders the inner mitochondrial membrane permeable to hydrophilic molecules up to 1500 Da (Zoratti and Szabo, 1995). Calcein (∼620 Da when deesterified) has been used to identify opening of PTP in both cells (Petronilli et al., 1999) and in isolated mitochondria (Huser et al., 1998). We loaded mitochondria with the ester form of calcein, which is hydrolyzed and entrapped in the mitochondrial matrix. To record the calcein fluorescence and ΔΨm in the same mitochondria, calcein-loaded mitochondria were perfused with TMRM (which avoids the problem of overlap of excitation and emission wavelengths). Because we were not able to monitor the fluorescence of calcein and TMRM with the same optics, we measured calcein fluorescence first, then changed the dichroic mirror for TMRM wavelength, monitored ΔΨm for a few minutes in the same field, and then switched the optics back for calcein measurements. Fig. 6 shows the fluorescence images of calcein (green) and TMRM (red) and the plots obtained from three individual mitochondria. As can be seen, despite continuous fluctuations in ΔΨm reported by TMRM fluorescence, mitochondria did not demonstrate equivalent, stochastic loss of the calcein signal that should accompany an increase in permeability of the inner membrane. The minor decrease in the average calcein fluorescence was presumably due to photobleaching because we did not observe a decrease in calcein fluorescence in cells that were not illuminated during the recording. To provide a positive control for calcein release from mitochondria when the permeability of mitochondrial membrane is increased, we used the pore-forming antibiotic alamethicin (Fox and Richards, 1982; Marsh, 1996). Fig. 6 shows that application of alamethicin induces a quick loss of fluorescence in calcein-loaded mitochondria (Fig. 6 B) and a complete mitochondrial depolarization (Fig. 6 C). The loss of calcein signal was not the consequence of mitochondrial depolarization, because deenergization of mitochondria induced by the removal of the substrates did not change calcein fluorescence (data not shown). We did not observe an interference of the calcein and TMRM signals as has been reported by Huser et al. (1998). This may be because we used a smaller concentration of TMRM (40 nM) instead of 200–400 nM, which was used in the experiments of Huser et al. (1998).

FIGURE 6.

The measurement of calcein fluorescence in single mitochondria. (A) The calcein fluorescence and ΔΨm (TMRM) were measured in the same mitochondria (see explanation in the text). The series of images at the top represent DIC and fluorescent images taken at the different time points indicated. The images show the fluorescence of calcein (green images) and TMRM (red images). The traces illustrate individual mitochondria and mean calcein signal (± SE, n = 100 mitochondria). These data are representative of five additional experiments. (B) Left panel, DIC image and fluorescence images showing the loss of calcein fluorescence in the presence of 40 μg/ml alamethicin; right panel, the traces obtained from individual mitochondria and mean calcein signal (± SE, n = 50 mitochondria). The data are representative of three additional experiments. (C) Alamethicin-induced depolarization of ΔΨm measured by Rh123. The concentration of alamethicin was 40 μg/ml. Each trace corresponds to an individual mitochondrion.

We also checked the effect of the MPT blocker cyclosporin A (CsA) on ΔΨm. CsA (1 μM) was added into the perfusion medium for the duration of the ΔΨm recording. Fig. 7 shows that the treatment of mitochondria with CsA did not change any of the parameters of the fluctuations in ΔΨm. The lack of calcein movement across the mitochondrial membrane and the absence of effect of CsA is inconsistent with a role for MPT in the spontaneous changes in ΔΨm.

FIGURE 7.

Effect of cyclosporin A (CsA) on ΔΨm. The histograms show a mean Rh123 fluorescence (A), percentage of fluctuating mitochondria (B), and frequency of fluctuations (C) in single mitochondria in control and 1 μM CsA-containing medium. Each histogram represents the mean (± SE) of five experiments, and 150 mitochondria were analyzed in each experiment. None of the relevant differences reached statistical significance (P > 0.05).

DISCUSSION

In this study we have provided the first demonstration of spontaneous fluctuations in ΔΨm in isolated rat brain mitochondria. These mitochondria develop a ΔΨm when provided with glutamate and malate as substrates, and then a substantial fraction of the mitochondria display stochastic, large amplitude decreases in fluorescence consistent with transient depolarization of ΔΨm. These changes become more substantial with increased duration of experimental recordings or exposure to calcium but do not appear to be a consequence of fluorescence illumination. Moreover, the fluctuations do not appear to be the result of activation of MPT.

As noted above, spontaneous changes in the signals of fluorescence indicators of and exposure to calcium have previously been reported in both cultured cells and isolated mitochondria, although not in isolated brain mitochondria. In general, these studies have reported rather similar basic phenomena to the findings reported here. Thus, mitochondria loaded with ΔΨm-sensitive dyes show a progressively enhanced frequency of spontaneous, large amplitude changes in fluorescence that is typically attributed to mitochondrial depolarization (Ichas et al., 1997; Fall and Bennett, 1999; Huser et al., 1998; Huser and Blatter, 1999; Duchen et al., 1998; Belousov et al., 2001). We have additionally observed transient increases in dye signals that appear to be the only form of spontaneous activity exhibited by neurons (Buckman and Reynolds, 2001a) and are distinct from the spontaneous depolarizations seen in cultured astrocytes (Buckman and Reynolds, 2001b). It is thus evident that spontaneous changes in mitochondrial membrane potential are a common, if underappreciated, phenomenon. However, there does not appear to be a clear consensus regarding the mechanism that is responsible for this effect.

A number of studies have identified MPT in mitochondria of brain origin. Exposing neurons to elevated intracellular Ca2+ after N–methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor activation produces a mitochondrial depolarization that has been attributed to MPT (White and Reynolds, 1996; Schinder et al., 1996; Nieminen et al., 1996). Inhibitors of MPT have also been reported to protect neurons from hypoglycemic and ischemic injury (Friberg et al., 1998), although this effect has previously been attributed to calcineurin inhibition (Dawson et al., 1993). Expression of MPT also appears to vary according to the region of the brain used as a source of mitochondria (Friberg et al., 1999). However, there are also differences between MPT in brain mitochondria compared to liver mitochondria. For example, the amplitude of swelling induced by MPT in isolated brain mitochondria is clearly much smaller than in liver mitochondria (Berman et al., 2000; Andreyev and Fiskum, 1999; Brustovetsky and Dubinsky, 2000). It is also evident that NMDA receptor-mediated mitochondrial depolarization can occur independently of MPT activation, and it is difficult to unequivocally attribute alterations in mitochondrial function in intact neural cells to MPT (Reynolds and Hastings, 2001). Nevertheless, under appropriate conditions, MPT can clearly be expressed by brain mitochondria (Berman et al., 2000; Andreyev et al., 1998; Brustovetsky and Dubinsky, 2000).

Given the regularity with which previous studies have attributed spontaneous depolarizations in isolated mitochondria to MPT, it is perhaps surprising that MPT does not appear to be the source of this phenomena in our experiments. CsA is the prototypical MPT inhibitor and can inhibit MPT-like events in our brain mitochondria preparation. However, our observations of CsA sensitivity (of mitochondrial Ca2+ handling) were seen only in mitochondria suspended in a sucrose/mannitol buffer, and the CsA sensitivity was lost in a potassium-based buffer of the kind used in this study (T.V.V. and I.J.R., unpublished observations). The actions of CsA can be overcome by the addition of excess Ca2+, but that is unlikely to be occurring in our experiments under basal conditions because of the presence of EDTA in the normal superfusion buffer. We would also expect altered permeability of the inner membrane to be associated with the loss of calcein, which should be small enough to permeate the pore (Zoratti and Szabo, 1995). Calcein quenching has previously been used to detect MPT activation (Petronilli et al., 1999), although in that case calcein was used in conjunction with cobalt which quenches calcein fluorescence. It was not clear whether calcein leaves mitochondria or whether cobalt enters through the pore in these studies. Huser and colleagues (1998) have demonstrated, however, that calcein leaves rat ventricular mitochondria under similar conditions, supporting the contention that it would report permeability changes if these were to occur. Thus, we conclude that the changes in ΔΨm are not due to MPT activation in this mitochondrial preparation. This leaves open the question of the conductance that is activated in our experiments. There are many potential candidates, including ATP-sensitive and Ca2+-activated potassium currents (Grover and Garlid, 2000; Xu et al., 2002), a variety of putative uncoupling proteins (Skulachev, 1998; Ricquier and Bouillaud, 2000), and perhaps even the Ca2+ uniporter, not to mention proteins like the adenine nucleotide translocator that can evidently operate as either a carrier or as an ion channel under different circumstances (Connern and Halestrap, 1994). The identity of the conductance in brain mitochondria awaits further experimentation.

The physiological relevance of spontaneous depolarizations has yet to be demonstrated, too. It has been suggested that the entire phenomenon is a consequence of the oxidative stress associated with light exposure and the subsequent generation of oxidants like singlet oxygen (Belousov et al., 2001). If this were the case, one could still credibly claim that the phenomenon was relevant to pathophysiological conditions that are associated with oxidative stress. Our studies presented here and others (Huser et al., 1998) clearly demonstrate that the spontaneous changes are a progressive phenomenon, so that the mean fluorescence signal decreases as the experiment progresses, and also demonstrate that the frequency of the spontaneous changes increases. This has also been reported in intact astrocytes (Belousov et al., 2001). Although we initially assumed that this was likely to be due to oxidative stress triggered by light exposure, this does not appear to be the case. The finding that mitochondria also lose Rh123 fluorescence even without light exposure argues against light and oxidative stress as a cause of the loss of signal (Fig. 4), as does the failure of histidine or GSH to protect mitochondria (Fig. 5). Similar concentrations of GSH were previously found to delay the onset of MPT (Huser et al., 1998), and this might provide an additional argument against the expression of MPT in our mitochondria. The cause of the time-dependent loss of dye signal and increase in frequency of fluctuations remains unclear, but might be attributable to the washout of some key extra-mitochondrial factor during superfusion.

One of the more striking features of the recording of responses from individual organelles is the heterogeneity in the responses. Even when presented simultaneously with the depletion of substrates or Ca2+, there was a remarkable difference in the time between the earliest and latest response within a given field. The basis of this heterogeneity is not clear. Although the mitochondria preparation is enriched in nonsynaptosomal, and presumably thus astrocyte, mitochondria (Sims, 1991), we lack definitive markers to differentiate the organelles at this level. It is also possible that the difference in the responses reflects varying degrees of damage of the organelles during preparation. In this way one might consider the spontaneous changes as a marker of injured mitochondria, and the increase in fluctuations would therefore reflect additional “injury” during the course of the experiment. This interpretation would be consistent with a more marked response to the introduction of Ca2+ in mitochondria that are already fluctuating. Identifying the mechanism responsible for the spontaneous changes would be of great value to resolve this issue. Even so, it seems likely that this preparation may offer some useful and novel insights into physiological or pathophysiological properties of brain mitochondria.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Nicole Zeak for the preparation of mitochondria and Dr. Gordon Rintoul for the help with data analysis.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants AG 20899 and NS 41299.

References

- Andreyev, A. Y., B. Fahy, and G. Fiskum. 1998. Cyctochrome c release from brain mitochondria is independent of the mitochondrial permeability transition. FEBS Lett. 439:373–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreyev, A., and G. Fiskum. 1999. Calcium induced release of mitochondrial cytochrome c by different mechanisms selective for brain versus liver. Cell Death Differ. 6:825–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belousov, V. V., L. L. Bambrick, A. A. Starkov, D. B. Zorov, V. P. Skulachev, and G. Fiskum. 2001. Oscillations in mitochondrial membrane potential in rat astrocytes in vitro. Abstr. Soc. Neurosci. 27:205–218. [Google Scholar]

- Berman, S. B., S. C. Watkins, and T. G. Hastings. 2000. Quantitative biochemical and ultrastructural comparison of mitochondrial permeability transition in isolated brain and liver mitochondria: evidence for relative insensitivity of brain mitochondria. Exp. Neurol. 164:415–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi, P. 1999. Mitochondrial transport of cations: channels, exchangers, and permeability transition. Physiol. Rev. 79:1127–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brustovetsky, N., and J. M. Dubinsky. 2000. Dual responses of CNS mitochondria to elevated calcium. J. Neurosci. 20:103–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckman, J. F., and I. J. Reynolds. 2001a. Spontaneous changes in mitochondrial membrane potential in cultured neurons. J. Neurosci. 21:5054–5065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckman, J. F., and I. J. Reynolds. 2001b. Spontaneous mitochondrial activities in astrocytes. Abstr. Soc. Neurosci. 27:96–99. [Google Scholar]

- Bunting, J. R. 1992. A test of the singlet oxygen mechanism of cationic dye photosensitization of mitochondrial damage. Photochem. Photobiol. 55:81–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernyak, B. V., and P. Bernardi. 1996. The mitochondrial permeability transition pore is modulated by oxidative agents through both pyridine nucleotides and glutathione at two separate sites. Eur. J. Biochem. 238:623–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connern, C. P., and A. P. Halestrap. 1994. Recruitment of mitochondrial cyclophilin to the mitochondrial inner membrane under conditions of oxidative stress that enhance opening of a calcium-sensitive non-specific channel. Biochem. J. 302:321–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, T. M., J. P. Steiner, V. L. Dawson, J. L. Dinerman, G. R. Uhl, and S. H. Snyder. 1993. Immunosuppressant FK506 enhances phosphorylation of nitric oxide synthase and protects against glutamate neurotoxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 90:9808–9812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Giorgi, F., L. Lartigue, and F. Ichas. 2000. Electrical coupling and the plasticity of the mitochondrial network. Cell Calcium. 28:365–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchen, M. R., A. Leyssens, and M. Crompton. 1998. Transient mitochondrial depolarizations reflect focal sarcoplasmic reticular calcium release in single rat cardiomyocytes. J. Cell Biol. 142:975–988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fall, C. P., and J. P. Bennett, Jr. 1999. Visualization of cyclosporin A and Ca2+-sensitive cyclical mitochondrial depolarizations in cell culture. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1410:77–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox, R. O., and F. M. Richards. 1982. A voltage-gated ion channel model inferred from the crystal structure of alamethicin at 1.5-A resolution. Nature. 300:325–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friberg, H., C. P. Connern, A. P. Halestrap, and T. Wieloch. 1999. Differences in the activation of the mitochondrial permeability transition among brain regions correlates with selective vulnerability. J. Neurochem. 72:2488–2497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friberg, H., M. Ferrand-Drake, F. Bengtsson, A. P. Halestrap, and T. Wieloch. 1998. Cyclosporin A, but not FK 506, protects mitochondria and neurons against hypoglycemic damage and implicates the mitochondrial permeability transition in cell death. J. Neurosci. 18:5151–5159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grover, G. J., and K. D. Garlid. 2000. ATP-sensitive potassium channels: a review of their cardioprotective pharmacology. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 32:677–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huser, J., and L. A. Blatter. 1999. Fluctuations in mitochondrial membrane potential caused by repetitive gating of the permeability transition pore. Biochem. J. 343:311–317. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huser, J., C. E. Rechenmacher, and L. A. Blatter. 1998. Imaging the permeability pore transition in single mitochondria. Biophys. J. 74:2129–2137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichas, F., L. S. Jouaville, and J. P. Mazat. 1997. Mitochondria are excitable organelles capable of generating and conveying electrical and calcium signals. Cell. 89:1145–1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krippeit-Drews, P., M. Dufer, and G. Drews. 2000. Parallel oscillations of intracellular calcium activity and mitochondrial membrane potential in mouse pancreatic B-cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 267:179–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loew, L. M., R. A. Tuft, W. Carrington, and F. S. Fay. 1993. Imaging in five dimensions: time-dependent membrane potentials in individual mitochondria. Biophys. J. 65:2396–2407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, D. 1996. Peptide models for membrane channels. Biochem. J. 315:345–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama, S., T. Sakuyama, S. Mitaku, and Y. Ohta. 2002. Fluorescence imaging of metabolic responses in single mitochondria. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 290:23–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls, D. G. 2001. A history of UCP1. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 29:751–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls, D. G., and M. W. Ward. 2000. Mitochondrial membrane potential and neuronal glutamate excitotoxicity: mortality and millivolts. Trends Neurosci. 23:166–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieminen, A.-L., T. G. Petrie, J. J. Lemasters, and W. R. Selman. 1996. Cyclosporin A delays mitochondrial depolarization induced by N-methyl-d-aspartate in cortical neurons: evidence of the mitochondrial permeability transition. Neuroscience. 75:993–997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petronilli, V., G. Miotto, M. Canton, M. Brini, R. Lonna, P. Bernardi, and F. Di Lisa. 1999. Transient and long-lasting openings of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore can be monitored directly in intact cells by changes in mitochondrial calcein fluorescence. Biophys. J. 76:725–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, I. J., and T. G. Hastings. 2001. Role of the permeability transition in glutamate mediated neuronal injury. In Mitochondria in Pathogenesis. J. J. Lemasters and A.-L. Nieminen, editors. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, New York. 301–16.

- Ricquier, D., and F. Bouillaud. 2000. The uncoupling protein homologues: UCP1, UCP2, UCP3, StUCP and AtUCP. Biochem. J. 345:161–179. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schinder, A. F., E. C. Olson, N. C. Spitzer, and M. Montal. 1996. Mitochondrial dysfunction is a primary event in glutamate neurotoxicity. J. Neurosci. 16:6125–6133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims, N. R. 1991. Selective impairment of respiration in mitochondria isolated from brain subregions following transient forebrain ischemia in the rat. J. Neurochem. 56:1836–1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skulachev, V. P. 1998. Uncoupling: new approaches to an old problem of bioenergetics. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1363:100–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White, R. J., and I. J. Reynolds. 1996. Mitochondrial depolarization in glutamate-stimulated neurons: an early signal specific to excitotoxin exposure. J. Neurosci. 16:5688–5697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W. H., Y. G. Liu, S. Wang, T. McDonald, J. E. Van Eyk, A. Sidor, and B. O'Rourke. 2002. Cytoprotective role of Ca2+-activated K+ channels in the cardiac inner mitochondrial membrane. Science. 298:1029–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y., O. Marcillat, C. Guilivi, L. Ernster, and K. J. A. Davies. 1990. The oxidative inactivation of mitochondrial electron transport chain components and ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 265:16330–16336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoratti, M., and I. Szabo. 1995. The mitochondrial permeability transition. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1241:139–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]