Abstract

The repressor-activator MerR that controls transcription of the mercury resistance (mer) operon is unusual for its high sensitivity and specificity for Hg(II) in in vivo and in vitro transcriptional assays. The metal-recognition domain of MerR resides at the homodimer interface in a novel antiparallel arrangement of α-helix 5 that forms a coiled-coil motif. To facilitate the study of this novel metal binding motif, we assembled this antiparallel coiled coil into a single chain by directly fusing two copies of the 48-residue α-helix 5 of MerR. The resulting 107-residue polypeptide, called the metal binding domain (MBD), and wild-type MerR were overproduced and purified, and their metal-binding properties were determined in vivo and in vitro. In vitro MBD bound ca. 1.0 equivalent of Hg(II) per pair of binding sites, just as MerR does, and it showed only a slightly lower affinity for Hg(II) than did MerR. Extended X-ray absorption fine structure data showed that MBD has essentially the same Hg(II) coordination environment as MerR. In vivo, cells overexpressing MBD accumulated 70 to 100% more 203Hg(II) than cells bearing the vector alone, without deleterious effects on cell growth. Both MerR and MBD variously bound other thiophilic metal ions, including Cd(II), Zn(II), Pb(II), and As(III), in vitro and in vivo. We conclude that (i) it is possible to simulate in a single polypeptide chain the in vitro and in vivo metal-binding ability of dimeric, full-length MerR and (ii) MerR's specificity in transcriptional activation does not reside solely in the metal-binding step.

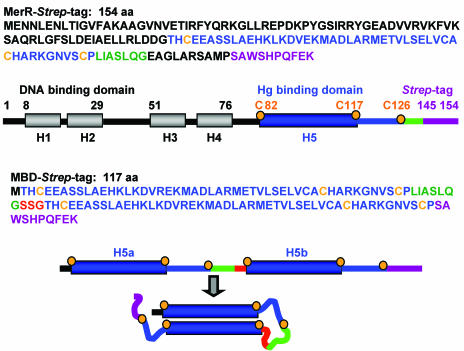

One of the best understood bacterial mercury resistance (mer) operons, located on transposon Tn21 from Shigella flexneri IncFII plasmid R100, contains five structural genes, merTPCAD(2). This gene cluster constitutes a Hg(II)-detoxification system which transports Hg(II) into cells (via MerT, MerC, and MerP), where soluble ionic Hg(II) is reduced to volatile Hg(0) vapor by MerA. The system is under positive and negative transcriptional control by the Hg(II)-responsive metalloregulatory protein MerR (2). Binding to the operator merO, MerR represses the transcription of merTPCAD in the absence of Hg(II) and activates transcription in the presence of Hg(II). MerR contains three domains: the N-terminal DNA binding domain (residues 10 to 29), the C-terminal Hg(II) binding domain (residues 82 to 126), and an intervening region of undefined function (residues 30 to 81) (22, 27) (Fig. 1). Three conserved cysteine residues in the Hg(II) binding domain of the MerR dimer form a trigonal Hg(II)-coordination site, employing C117 and C126 from one monomer and C82 from the other. Although a MerR dimer has two potential Hg(II)-coordination sites, it only binds one Hg(II) in vitro (23, 29-31).

FIG. 1.

Construction of MBD. The MBD gene was constructed by connecting two α-helices 5 of MerR in tandem with three nonnative amino acids, SSG, as a bridge. The carboxyl terminus of MBD was fused with the 10-amino-acid Strep affinity tag, represented in purple, in the pASK-IBA3 vector. A Strep-tag fusion of full-length MerR was also made with this vector. Bars indicate helices as follows: blue bars indicate α-helices in the metal binding domain of MerR, and gray bars indicate other α-helices of MerR. Lines indicate non-α-helix regions as follows: the red line indicates the SSG linker, and the blue and green lines indicate the loop after α-helix 5 and the region after the loop, respectively. Orange dots indicate cysteines involved in Hg(II) binding, which are also given in orange in the sequences.

Tn21 MerR demonstrates a high affinity and specificity for Hg(II) during in vivo and in vitro transcription assays, responding to Hg(II) at concentrations as low as 10−9 M in the presence of 1 to 5 mM competing thiol ligands (7, 18). Cd(II) and Zn(II) do not activate mer transcription in vivo (18), but they do activate it in vitro at metal ion concentrations of 100-fold and 1,000-fold more, respectively, than Hg(II) (18). However, a transcription assay is not the same as a direct protein-metal binding assay, although both assays are often assumed to report on the same phenomenon. The only quantitative data about the direct binding of other metals by MerR in vitro are those indicating the allosteric response of immobilized Bacillus MerR to 10−14 M Cu(II) or Cd(II) in a biosensor assay (8).

The first three-dimensional (3-D) structures of two metal-binding members of the MerR family, CueR and ZntR (4, 17, 26), have recently appeared (6). The metal-recognition domain of these proteins is an antiparallel, coiled coil lying in the C-terminal half of the protein, as predicted by earlier genetic, biochemical, and biophysical work. Specifically, this antecedent work established that (i) the Hg(II) binding response of MerR requires three cysteines (C82, C117, and C126) and the protein functions as a dimer, employing C117 and C126 from one monomer and C82 from the other to bind Hg(II) (14, 19, 23); (ii) MerR has a long α-helix (residues 82 to 117) with a strongly predicted propensity to form a coiled coil (5, 31); (iii) a deletion mutant containing only residues 80 to 128 of MerR folds into an α-helix and forms stable dimers capable of binding Hg(II) even in the presence of excess thiols (31); and (iv) crystal structures of two MerR family members, the aromatic drug-binding regulators BmrR and MtaN (11, 13), show antiparallel coiled coils in regions corresponding to the C terminus of the metal-binding members of the MerR-family.

To facilitate the study of MerR's metal-binding mechanism, we constructed a single polypeptide consisting of two tandem direct repeats of α-helix 5 of Tn21 MerR. In this 107-residue protein (Fig. 1), the two α-helices are free to fold back upon each other to form an antiparallel coiled coil, thereby mimicking in a single chain the MerR binding domain ordinarily constituted by the interaction of two monomers. We compared the biochemical, biophysical and properties of this small protein with those of wild-type MerR.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

Escherichia coli strain XL1-Blue {recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17 supE44 relA1 lac [F′ proAB lacIqZΔDM15 Tn10(Tetr)]} (IBA GmbH, Göttingen, Germany) was the host strain for cloning and protein overexpression and purification. Plasmid pNH9 (Kmr merR) was the target of PCR for the construction of expression vectors (12). Plasmid pASK-IBA3 (Ampr) (IBA GmbH) was used for cloning and protein expression.

Construction of MBD-Strep-tag and MerR-Strep-tag.

The entire coding region of the metal binding domain (MBD) was amplified by PCR from the pNH9 template with two pairs of primers, which were designed with OLIGO software (National Biosciences, Inc., Plymouth, Minn.) and synthesized by Genosys Biotechnologies, Inc. (The Woodlands, Tex.). Two of these primers encoded a three-residue bridge, SSG, which does not occur in MerR and was added to afford some flexibility in the loop connecting the two number 5 α-helices (Fig. 1). The primer sequences were as follows: primer 1, 5′-TGCGGCGGTCTCAAATGACACACTGCGAGGAGG-3′; primer 2 (used with primer 1), 5′-GCCTGAGGATCCCTGTAGTGACGCGATCAACGG-3′; primer 3, 5′-CTACAGGGATCCTCAGGCACCCACTGCGAG-3′; and primer 4 (used with primer 3), 5′-CTGTAGGGTCTCGGCGCTCGGGCAGGAAACATT-3′. Target DNA sequences were amplified by a modified hot-start technique employing wax beads and previously described conditions (5).

The two PCR products were digested with BsaI or BamHI and cloned into BsaI-digested pASK-IBA3 in one step to construct pJC101, which was verified by DNA sequencing. Plasmid pJC101 contains the entire MBD gene fused to a region encoding a 10-residue Strep tag. The expression of the MBD gene is under the transcriptional control of TetR at the tetA promoter-operator and can be induced by tetracycline analogues. Similarly, wild-type merR was cloned from pNH9 into pASK-IBA3 to construct plasmid pJC100. Plasmids pJC100 and pJC101 were transformed into various E. coli strains by electroporation.

Protein expression and purification.

E. coli XL1-Blue cells carrying pJC100 or pJC101 were grown with aeration in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth at 30°C to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of ∼0.5 and were induced with 200 μg of anhydrotetracycline (AHT)/liter for 3 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, suspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) buffer containing 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 0.6 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 1 μg of leupeptin/ml, and broken with a French press two or three times at 16,000 lb/in2 at 4°C. The lysate was centrifuged at 15,800 × g at 4°C for 15 min and then filtered through a 0.2-μm-pore-size syringe filter (Whatman Inc.). The filtrate was loaded onto a Strep-Tactin Sepharose affinity column (IBA GmbH) containing 5.0 or 10.0 ml of resin that had been previously washed three times with 1 column volume of buffer 1 (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA) and three times with 1 column volume of buffer 2 (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM DTT). The loaded column was washed and eluted according to the manufacturer's specifications, except that the elution buffer (buffer E) contained 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM DTT, and 2.5 mM desthiobiotin. Eluate fractions containing MBD were concentrated in a 5,000-Da MWCO Centricon centrifugal filter (Millipore Corp., Bedford, Mass.) at 4°C, and glycerol was added to 10%. Proteins were stored at −80°C and dialyzed against buffer 3 (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.9], 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM beta-mercaptoethanol [BME], 10% glycerol) before each experiment. The protein was >99% pure, as assessed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-mass spectrometry (MALDI-MS) operating in reflectron mode (0.05% mass accuracy). The latter technique was preceded by dialysis of the protein into 0.1 M ammonium bicarbonate, pH 8.0, at 4°C, via two changes, of 1 and 2 h at a 1,000-fold volume each, followed by centrifugal concentration as described above.

Determination of protein concentration.

The extinction coefficient for each protein was calculated on the basis of its content of tryptophan, tyrosine, and cysteine at 280 nm (10). Protein concentrations were routinely measured by the Bradford assay, with bovine serum albumin (BSA) as the standard protein, and were corrected to their OD280 concentrations; for full-length MerR, the BSA-standardized Bradford assay correction factor was 1.024, and for MBD, it was 1.487. It was noted previously that the BSA-standardized Bradford assay underestimates protein concentrations for truncated MerR derivatives (31).

Quantitative Western blotting.

E. coli XL1-Blue cells expressing MerR or MBD were harvested, suspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) buffer containing 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 10 mM DTT, and lysed by sonication at 4°C. Lysates were centrifuged at 15,800 × g for 15 min at 4°C, and the pellet was suspended in the same volume of the above buffer heated at 95 to 98°C for 5 min in Laemmli gel-loading buffer. Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE with Bio-Rad 18% polyacrylamide-Tris-HCl Ready gels in Tris-tricine buffer and then were transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes which were blocked, washed, and incubated with anti-MerR polyclonal antisera, and after additional washing, with fluorescein-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (Amersham Biosciences, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) for 1.5 h. The washed and dried membranes were quantified by using ImageQuaNT software on a FluorImager 575 (Molecular Dynamics, Inc.). The lysate protein was measured by the Bradford assay, and the corresponding cellular wet mass was determined by using the standard value of 156 × 10−15 g of total protein/cell (16). Serial dilutions of pure MerR-Strep-tag or MBD-Strep-tag were run on the same gel to generate a standard curve.

Hg(II) binding in vitro.

The relative affinities of MBD and MerR for Hg(II) were determined by conventional free dialysis and by equilibrium ultrafiltration (31). For equilibrium ultrafiltration, 10.0 μM protein in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.9) buffer containing 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM BME, and 10% glycerol was incubated with 5 to 20 μM 203HgCl2 for 15 min at room temperature. Reactions and buffer controls were each transferred to a 3,000-Da MWCO Amicon ultrafiltration unit (Millipore) and centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 9 min. The Hg(II) concentrations were determined in the upper and lower chambers of ultrafiltration units by liquid scintillation spectrometry in a Beckman LS-100 spectrometer or by γ-counting in a Packard Cobra γ-spectrometer and were corrected for modest Hg(II) loss to vessel surfaces by the appropriate buffer-only controls. For free dialysis, 60 μM proteins in the above buffer were allowed to react with a fourfold molar excess of HgCl2 for 1 h at room temperature and then were dialyzed in 3,500 MWCO Slide-A-Lyzers (Pierce, Inc.) against the same buffer containing 1 mM BME for two 1-h changes, of a 1,000-fold volume each, at 4°C. The protein binding of Hg was determined by inductively coupled plasma MS (ICP-MS).

Hg(II) accumulation by whole cells in vivo.

E. coli XL1-Blue cells harboring pJC101, pJC100, or the vector pASK-IBA3 were grown in LB broth containing 100 μg of ampicillin/ml at 37°C with shaking at 250 rpm to an OD600 of ∼0.5, and portions were induced with 200 μg of AHT/liter for 3 h. Induced and uninduced cultures were exposed to subtoxic 3 μM 203HgCl2 in a 1.0-ml reaction. A 300-μl aliquot was periodically removed and centrifuged at 15,800 × g at 4°C. The radioactivities of the supernatant and pellet were measured by liquid scintillation or γ-spectrometry.

XAS.

The X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) protocol of Zeng et al. (31) was used, with slight modifications. Proteins were mixed with equimolar Hg(II) in buffer 4 (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 500 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 10 mM BME) and were dialyzed in Slide-A-Lyzer cassettes (10,000-Da cutoff for MerR and 3,500-Da cutoff for MBD; Pierce, Chicago, Ill.) against 2 liters of buffer 4 in two changes (1 h and 2 to 3 h) at 4°C. Aliquots of dialyzed proteins were removed for the determination of total [Hg] by ICP-MS, and the remainder was concentrated to 50 to 100 μl in a 0.5-ml-capacity Amicon Ultrafree-MC centrifugal filter device (10,000-Da cutoff for MerR and 5,000-Da cutoff for MBD) by centrifugation at 4°C and then adjusted to 30% glycerol. Each sample contained 0.2 to 0.4 mM protein-metal complexes after adjustment. Samples were loaded into 50- or 100-μl-capacity XAS cuvettes and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Mercury L3-edge XAS data were collected at 10 K at beamline 9-3 of the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory (SSRL), with the SPEAR storage ring operating in a dedicated mode at 3.0 GeV and 50 to 100 mA. An Si[220] double-crystal monochromator and a 30-element Ge solid-state X-ray fluorescence detector were employed for data collection. No photoreduction was observed when comparing the first and last spectra collected for a given sample. The first inflection of the edge of a Hg-Sn amalgam standard was used for energy calibration (Table 1). Extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) analysis was performed with EXAFSPAK software (http://www-ssrl.slac.stanford.edu/exafspak.html) according to standard procedures (21). Fourier transforms (FTs) were calculated with sulfur-based phase-shift correction. The theoretical amplitude and phase-shift functions employed in simulation were generated with FEFF 8.2 code (1). A curve-fitting analysis was performed as described previously (9).

TABLE 1.

Hg XAS data collection

| Characteristic | Hg L3-edge EXAFS value or description |

|---|---|

| Synchrotron radiation facility | SSRL |

| Beamline | 9-3 |

| Current in storage ring (mA) | 60-100 |

| Monochromator crystal | Si[220]-B |

| Detection method | Fluorescence |

| Detector type | Solid-state arraya |

| Scan length (min) | 20-22 |

| Scans in average | 3-6 |

| Temperature (K) | 10 |

| Energy standard | Hg/Sn amalgam |

| Energy calibration (eV) | 12,285 |

| E0 (eV) | 12,295 |

| Pre-edge background data | |

| Energy range (eV) | 11,960-12,250 |

| Gaussian center (eV) | 9,987 |

| Gaussian width (eV) | 4,300 |

| Spline background data | |

| Energy range (eV) (polynomial order) | 12,295-12,565 (4) |

| 12,565-12,835 (4) | |

| 12,835-13,104 (4) |

The 30-element Ge solid-state fluorescence detector at SSRL was provided by the NIH Biotechnology Research Resource.

Binding of other thiophilic metals. (i) In vitro.

Proteins (60 μM) were exposed to 120 to 200 μM NaAsO2, CdCl2, lead (II) acetate, or ZnCl2 in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.9) containing 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM BME, and 10% glycerol for 1 h at 24°C. Proteins were dialyzed against a 2,000-fold excess of the same buffer for 2 h at 4°C, with two changes. Protein-bound metals were measured by ICP-MS.

(ii) In vivo.

AHT-induced XL1-Blue strains containing pJC100 or pJC101 were exposed to NaAsO2, CdCl2, lead (II) acetate, or ZnCl2 for 2.5 h at 37°C and then centrifuged for 5 min at 15,800 × g at room temperature. Cd(II), Pb(II), and As(III) were each added at a subtoxic level of 3 μM; however, since the [Zn(II)] in LB medium was 18 μM, no additional Zn(II) was added. The metal concentrations in the medium and the cells were determined by ICP-MS. The cellular content of MerR or MBD was quantified by Western blotting (see above).

RESULTS

Design and production of MBD.

Previous studies of MerR (31) indicated that its Hg(II)-binding ability lies in residues 82 to 126. MBD was designed as a single polypeptide that could fold into an antiparallel coiled coil, thereby forming a structure like that formed by the two chains of the MerR dimer (Fig. 1). Ser-Ser-Gly was used as a short linker between the tandem metal binding domains, since serine and glycine have small side chains and impose no electrostatic effects and minimal steric effects on the structure. We used the Strep-tag affinity peptide because, unlike the hexahistidine tag (His tag) (20, 25), it does not bind thiophilic metals.

For cells grown at 30°C, a quantitative Western blot analysis of cell lysates, supernatants, and pellets showed that >90% of both proteins was soluble. Cell lysates fully induced for MerR expression ranged from 6 × 105 to 9 × 105 molecules/cell and for MBD expression ranged from 5.6 × 105 to 8 × 105 molecules/cell. The isolated proteins were >99% pure by Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE and by MALDI-MS and had no detectable metal ions by ICP-MS. The calculated monomer molecular mass of the Strep-tagged MBD protein was 12,821 Da. By MALDI-MS (in reflectron mode, with 0.05% mass accuracy), purified MBD had a molecular mass of 12,818 Da. There was a minor peak (<5%) of doubly charged, monomeric MBD at 6,409.5 Da; singly charged dimeric MBD at 25,642 Da was <1% of the total signal. Similarly prepared MerR was ca. 80% dimeric under these conditions, as was also observed previously by electrospray MS and gel filtration (31).

Hg(II)-binding properties in vitro and in vivo.

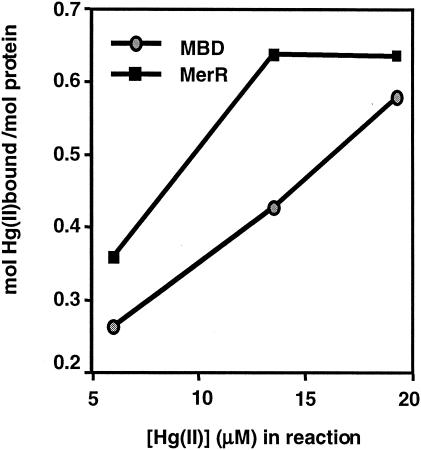

Both free dialysis and equilibrium ultrafiltration were used to compare MBD and MerR. With free dialysis after exposure to a fourfold molar excess of metal ion, MerR bound Hg(II) with a stoichiometry of 0.90 ± 0.06 Hg(II)/MerR dimer, consistent with previous observations for MerR (29) or C-terminally His-tagged MerR (31). The Hg(II)-binding stoichiometry of MBD with free dialysis was 1.12 ± 0.18 Hg(II)/MBD monomer, indicating that, as intended, one MBD monomer is equivalent to one MerR dimer by this measurement. These results suggest that the C-terminal Strep-tag fusion does not bind Hg(II) itself or interfere with MerR's Hg(II)-binding function. Given their similar behaviors in free dialysis, equilibrium ultrafiltration was employed with a range of lower Hg(II) concentrations to tease out differences between MBD and MerR. Under these conditions, MerR's stoichiometry was 0.65 ± 0.07 and MBD bound Hg(II) from 60 to 70% as well as MerR at lower ligand concentrations (Fig. 2). At the highest ligand concentration, MBD's stoichiometry approached that of MerR, consistent with the free dialysis observations.

FIG. 2.

Equilibrium ultrafiltration determination of 203Hg binding to purified MerR and MBD. The values are the means of duplicate measurements. The average standard deviation was 10%. MerR values are presented as per mole of MerR dimers.

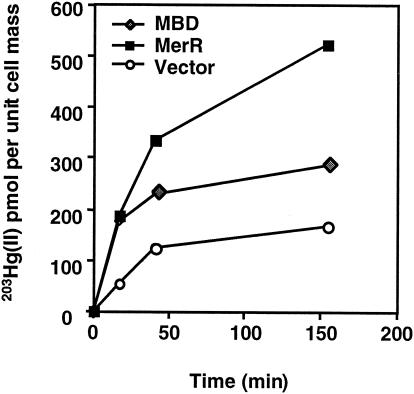

To investigate whether intracellular MBD and MerR can bind Hg(II) in intact E. coli cells, we measured the ability of growing cells expressing MerR or MBD to accumulate 203Hg(II) supplied at a subtoxic level (3 μM in LB medium) (Fig. 3). Cells containing only the vector were saturated by Hg(II) in the first 50 min. For comparison, cells expressing MBD accumulated 80% more Hg(II) on a per cell basis than the vector-containing cells. The culture expressing MerR was not saturated even after 150 min of incubation with Hg(II) (Fig. 3). Thus, intracellularly expressed MerR and MBD competed effectively with metal-binding competitors in the rich medium and accumulated threefold and two-fold more Hg(II), respectively, than cells containing the vector only.

FIG. 3.

Accumulation of 203Hg(II) by cells containing MerR or MBD. The values are the means of duplicate measurements. The average standard deviation was 29%. The units [moles of 203Hg(II) per picomole per unit of cell mass] indicate the amount of 203Hg(II) in cell cultures normalized on the basis of OD600.

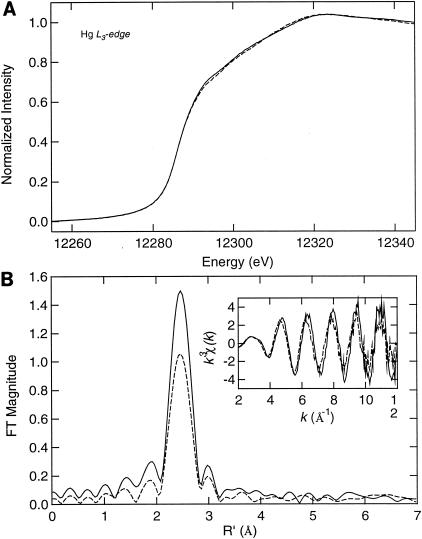

XAS of Hg(II)-protein complexes.

XAS is a qualitative biophysical technique that reveals the ligand type (i.e., what element) and coordination number (i.e., how many ligands) of protein-metal centers (21). The technique cannot discern subpopulations with distinct coordination environments; rather, XAS reports on the aggregate characteristics of the entire population of metal centers. Previous XAS work with MerR (30, 31) and deletion derivatives of it (31) revealed an unusual tricoordinate HgS3 structure for the MerR-Hg binding center. Here we found that the XAS spectra of MBD and MerR indicated a very similar coordination of mercury in both proteins (Fig. 4A), consistent with previous observations of MerR purified under denaturing conditions (28, 29, 31) and of native His-tagged MerR (28, 29, 31). The FTs (Fig. 4B) of the EXAFS (Fig. 4B, inset) data for both MerR and MBD indicated a single shell of scatterers at about 2.4 to 2.5 Å, consistent with the average Hg-S bond distance of 2.43 Å (range, 2.41 to 2.51 Å) in MerR, as measured previously (28, 30). The EXAFS curve-fitting results (Table 2) indicate that the average Hg-S bond length of MBD is slightly longer than that of MerR, although still within the range for three-coordinate Hg-S sites. (Average Hg-S bond lengths for two- and four-coordinate sites are 2.34 and 2.54 Å, respectively [28, 29, 31].) However, the larger Debye-Waller factor (σas2) for MBD suggests that the Hg(II)-binding site of MBD is more disordered than that of MerR, as also indicated by the relatively damped FT peak intensity for MBD (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

EXAFS analysis of Hg(II) complexes with MerR and MBD. XAS edge (top) and EXAFS FT and experimental k3-weighted EXAFS spectra (bottom and insert, respectively) for comparison of full-length MerR-Strep-tag (solid lines) and MBD-Strep-tag (dashed lines) are shown. The conditions used are shown in Table 1, and curve-fitting results are shown in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Curve-fitting results for Hg L3 EXAFSa

| Sample filename (k range [Å−1]) | Fit | Shell | Ras (Å) | σas2 (Å2) | ΔE0 (eV) | f′b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MerR-Hg HRO2A (2-12) (Δk3χ = 8.07) | 1 | Hg-S2 | 2.45 | 0.0001 | 0.27 | 0.053 |

| 2 | Hg-S3 | 2.45 | 0.0024 | 0.81 | 0.069 | |

| 3 | Hg-S4 | 2.45 | 0.0043 | 1.34 | 0.099 | |

| MBD-Hg HD02A (2-12) (Δk3 χ = 6.92) | 4 | Hg-S2 | 2.46 | 0.0027 | −2.69 | 0.075 |

| 5 | Hg-S3 | 2.46 | 0.0052 | −2.28 | 0.073 | |

| 6 | Hg-S4 | 2.46 | 0.0075 | −1.51 | 0.088 |

Shell, coordination sphere. Subscripts denote Ns, the number of scatterers per metal. Ras, metal-scatterer distance; σas2 (the Debye-Waller factor), mean square deviation in Ras; ΔE0, shift in E0 for the theoretical scattering functions.

|

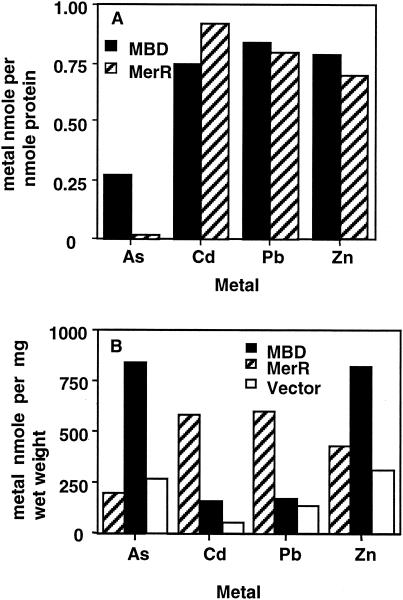

MerR and MBD bind other thiophilic metals.

Purified MerR and MBD bound other thiophilic metals, including Cd(II), Zn(II), and Pb(II), with stoichiometries of ca. 1 metal ion per MerR dimer or per MBD monomer in the presence of 1 mM BME (i.e., a 16-fold molar excess over [protein]) (Fig. 5A). In vivo data corroborated these findings generally and also revealed different behaviors in MerR and MBD. Cells overproducing MerR accumulated considerably more Cd(II) and Pb(II) and slightly more Zn(II) than cells containing only the vector (Fig. 5B). In contrast, cells expressing MBD accumulated only slightly more Cd(II) and Pb(II) than vector-only cells but considerably more Zn than the vector-only cells or cells expressing MerR. Interestingly, MBD bound the thiophilic metalloid As(III) both in vivo and in vitro, but MerR did not.

FIG. 5.

Binding of other thiophilic metals by MBD and MerR. (A) In vitro. (B) In vivo. The values are the means of duplicate measurements. Average standard deviations were 28% for panel A and 9% for panel B.

DISCUSSION

We have constructed a small polypeptide embodying in a single chain the metal-binding center of the dimeric metalloregulator MerR. The characteristics of the designed protein MBD in vivo and in vitro reveal that a stable, functional metal-recognition domain, normally formed through the interaction of two 144-residue monomers, can be constituted in a single 107-residue polypeptide chain that is smaller even than a single monomer of wild-type MerR. The designed protein MBD largely retains MerR's ability to compete with excess low-molecular-weight thiols for Hg(II) and by EXAFS establishes a very similar coordination environment for this metal ion.

The above properties would arise if MBD forms an intramolecular antiparallel coiled coil; a hairpin structure (Fig. 1), but with an extended dimer, might also have these properties. It was previously shown by gel filtration (31) that MerR and the smallest deletion derivative previously made (called ΔΔ; it contains the same sequences incorporated in tandem into the MBD) are >90% dimers at 5 uM in the buffer used here for metal binding. As was also shown in that work, these earlier deletion derivatives, even ΔΔ, containing only 48 natural residues of MerR, folded stably into easily isolatable dimeric soluble proteins (31). These findings suggest that in MBD each coil-generating α-helix forms readily during translation and will find its most stable partner in the downstream polypeptide chain. As noted here, MBD is >95% monomeric under conditions in which MerR is ca. 80% dimeric by MALDI-MS. Thus, prior and current observations on MerR and MBD are consistent with the latter forming an intramolecular, anti-parallel coiled-coil hairpin, as intended. In addition, MBD mounted on the surfaces of resin beads binds Hg(II) twofold more tightly than similarly tethered MerR monomers (unpublished observations), suggesting that, when it is physically constrained, MBD can adopt an effective metal-binding conformation more easily than a similarly constrained MerR monomer, which must find an appropriately oriented partner to dimerize and form a metal binding site. Biophysical studies are under way to determine whether other conformers of MBD exist and, if so, what determines their distributions. In any case, since our comparisons of MerR and MBD have been done under the same conditions, our present findings with respect to stoichiometry, metal preferences, and Hg(II) coordination will remain the same.

Both MBD and MerR bound other thiophilic transition metals, including Cd(II), Zn(II), and Pb(II), in vitro in the presence of excess BME and also when highly expressed in vivo. This is the first work demonstrating the latter point, but others have also observed MerR's direct binding in vitro of Cd(II), Cu(II) (8, 29), and Zn(II) (3). The stoichiometry of MerR-Cd(II) binding that we observed in a millimolar thiol buffer in vitro is consistent with Wright's and other's (8, 29) observations of a Cd(II)-MerR dimer of 1:1 in a N2-saturated buffer containing 1 mM DTT. MBD's relatively poor ability to accumulate Cd(II) and Pb(II) in vivo may reflect competition from the high concentration of Zn(II) (18 μM) in the medium, which MBD seems even better able to sequester intracellularly than MerR. Both in vivo and in vitro, MBD differed from MerR in binding the thiophilic metalloid As(III) (Fig. 5).

Its larger EXAFS Debye-Waller factor for Hg indicates that MBD has a disordered Hg(II) binding site compared to that of MerR (Fig. 4; Table 2). Recently, Pecoraro and coworkers (15) observed a similar disorder in two artificial polypeptides, TRI-L12C and TRI-L16C, that were chemically synthesized as models for the investigation of metalloregulators such as MerR and CadC. These synthetic 30-residue polypeptides each contained a single central cysteine residue, and at a Hg(II)/peptide ratio of 1:3, they formed a disordered trigonal HgS3 structure. This distortion was proposed to arise from an inherently distorted Hg environment, such as T-shaped HgS3, or possibly from a mixture of 1:2 and 1:3 complexes (15). The observations that MBD binds Hg(II) less effectively than MerR (Fig. 2) and that it binds As(III) although MerR does not (Fig. 5) indicate that the Hg(II) binding domain of MBD can assume conformations distinct from those of MerR. These differences also support our previous hypothesis that steric hindrance of MerR's thiol ligands might constrain its stable association with smaller metal ions (5). As(III)'s covalent radius (121 pm) is smaller than that of Zn(II) (125 pm), and it can assume two- or three-coordination in proteins (24). MerR's failure to bind As(III) suggests that, unlike ArsR, which can provide various combinations of its three cysteines as bis-coordinate or tricoordinate sulfur ligands, MerR's cysteines are not arranged so as to form an As(III) complex that is sufficiently stable to compete with buffer or cellular thiols. The Pecoraro group's observations with the synthetic TRI oligopeptides and our observations with MBD are consistent with a requirement for the complete MerR protein in order to form the precisely ordered arrangement of thiol ligands characteristic of Hg(II) binding by full-length, dimeric MerR.

MerR is the index example of a growing family of metal-responsive regulators, each of which also has a long α-helical domain (α-helix 5) which was predicted to constitute an antiparallel coiled-coil dimer interface (5, 31). The 3-D structures of two aromatic compound-responsive members of the MerR family, BmrR and MtaN, revealed this prediction to be correct (11, 13). More recent work with CueR and ZntR (6) revealed the 3-D structures and metal coordination of the respective inducers of these two MerR family metalloregulators. CueR provides in each of its two binding sites a buried two-coordinate thiolate (Cys112 and Cys120) environment especially suitable for binding one monovalent metal cation, such as Ag(I), Au(I), and Cu(I), because excess negative charge from the thiolates is neutralized by the dipole of the long dimer interface helix. In contrast, in its crystal structure, ZntR provides three thiolates (Cys114, Cys115, and Cys124) and one histidine (His119) ligand to a pair of Zn(II) ions at each of its two potential binding sites. Unlike CueR, in which both ligands come from one monomer, ZntR (reminiscent of MerR) uses ligands from both monomers to effect a tetracoordinate binding site for each Zn(II) ion. Each protein has, in in vitro transcription assays, exquisite sensitivity to its respective inducer ions (zeptomolar for CueR and femtomolar for ZntR), suggesting that, despite their binding of two or four atoms of metal per dimer under crystallization conditions, each could trigger induction in the cell with only a single ion bound per dimer.

Since MerR and MBD retain homologs of the three Zn ligand cysteines found in ZntR, it is not surprising that they bind Zn(II) well in vitro (Fig. 5A). That MBD binds Zn(II) with a higher affinity than does MerR in vivo may arise from a more flexible presentation of these cysteine ligands, as suggested above. Two of MerR's and MBD's cysteines also correspond to Cys112 and Cys120, which bind Cu(I) in CueR, and we found that MerR and MBD bind Cu(I) and Ag(I) in vitro at one ion per dimer (data not shown). Thus, under metal-saturated crystallization conditions and with free dialysis, all three of these metalloregulators bind metals other than those understood to be their normal physiological inducers. Indeed, in transcriptional runoff assays, CueR is more sensitive to Ag(I) than to Cu(I) (6). Thus, the observed in vivo induction specificity for each system apparently does not reside solely in the metal-binding step. We hypothesize that accurate registration of the key protein ligands may be required for highly sensitive metal discrimination during transcriptional activation. This accurate recognition likely involves the whole protein and may even require that the protein be bound to its cognate DNA operator.

Acknowledgments

We thank Nathaniel Cosper for assistance with EXAFS work, Dennis Phillips of the Chemical and Biological Sciences Mass Spectrometry Facility for assistance with MALDI-MS, and Sayed Hassan and Keith Harris of the Laboratory for Environmental Analysis for metal quantification by ICP-MS. We are grateful for thoughtful comments on the manuscript by members of our lab group.

This work was funded by the Natural and Accelerated Bioremediation Research (NABIR) Program, Biological and Environmental Research (BER), Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy (grant 99ER62865 to A.O.S.). XAS studies were supported by the NIH (grant GM42025 to R.A.S.). SSRL is operated by the Division of Chemical Sciences, U.S. Department of Energy. The SSRL Biotechnology Program is supported by the Division of Research Resources, Biomedical Resource Technology Program, National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ankudinov, A. L., C. E. Bouldin, J. J. Rehr, J. Sims, and H. Hung. 2002. Parallel calculation of electron multiple scattering using Lanczos algorithms. Phys. Rev. B 65:104107.1-104107.11. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barkay, T., S. M. Miller, and A. O. Summers. 2003. Bacterial mercury resistance from atoms to ecosystems. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 27:355-384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bontidean, I., J. R. Lloyd, J. L. Hobman, J. R. Wilson, E. Csoregi, B. Mattiasson, and N. L. Brown. 2000. Bacterial metal-resistance proteins and their use in biosensors for the detection of bioavailable heavy metals. J. Inorg. Biochem. 79:225-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brocklehurst, K. R., J. L. Hobman, B. Lawley, L. Blank, S. J. Marshall, N. L. Brown, and A. P. Morby. 1999. ZntR is a Zn(II)-responsive MerR-like transcriptional regulator of zntA in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 31:893-902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caguiat, J. J., A. L. Watson, and A. O. Summers. 1999. Cd(II)-responsive and constitutive mutants implicate a novel domain in MerR. J. Bacteriol. 181:3462-3471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Changela, A., K. Chen, Y. Xue, J. Holschen, C. E. Outten, T. V. O'Halloran, and A. Mondragon. 2003. Molecular basis of metal-ion selectivity and zeptomolar sensitivity by CueR. Science 301:1383-1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Condee, C. W., and A. O. Summers. 1992. A mer-lux transcriptional fusion for real-time examination of in vivo gene-expression kinetics and promoter response to altered superhelicity. J. Bacteriol. 174:8094-8101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corbisier, P., D. van der Lelie, B. Borremans, A. Provoost, V. de Lorenzo, N. L. Brown, J. R. Lloyd, J. L. Hobman, E. Csoregi, G. Johansson, and B. Mattiasson. 1999. Whole cell- and protein-based biosensors for the detection of bioavailable heavy metals in environmental samples. Anal. Chim. Acta 387:235-244. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cosper, N. J., C. M. Stalhandske, R. E. Saari, R. P. Hausinger, and R. A. Scott. 1999. X-ray absorption spectroscopic analysis of Fe(II) and Cu(II) forms of a herbicide-degrading alpha-ketoglutarate dioxygenase. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 4:122-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edelhoch, H. 1967. Spectroscopic determination of tryptophan and tyrosine in proteins. Biochemistry 6:1948-1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Godsey, M. H., N. N. Baranova, A. A. Neyfakh, and R. G. Brennan. 2001. Crystal structure of MtaN, a global multidrug transporter gene activator. J. Biol. Chem. 276:47178-47184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamlett, N. V., E. C. Landale, B. H. Davis, and A. O. Summers. 1992. Roles of the Tn21 merT, merP, and merC gene products in mercury resistance and mercury binding. J. Bacteriol. 174:6377-6385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heldwein, E. E., and R. G. Brennan. 2001. Crystal structure of the transcription activator BmrR bound to DNA and a drug. Nature 409:378-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Helmann, J. D., B. T. Ballard, and C. T. Walsh. 1990. The MerR metalloregulatory protein binds mercuric ion as a tricoordinate, metal-bridged dimer. Science 247:946-948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matzapetakis, M., B. T. Farrer, T. C. Weng, L. Hemmingsen, J. E. Penner-Hahn, and V. L. Pecoraro. 2002. Comparison of the binding of cadmium(II), mercury(II), and arsenic(III) to the de novo designed peptides TRI L12C and TRI L16C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124:8042-8054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neidhardt, F. C., and H. E. Umbarger. 1996. Chemical composition of Escherichia coli, p. 13-16. In F. C. Neidhardt, R. Curtiss III, J. L. Ingraham, E. C. C. Lin, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, W. S. Reznikoff, M. Riley, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed., vol. 1. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 17.Outten, C. E., F. W. Outten, and T. V. O'Halloran. 1999. DNA distortion mechanism for transcriptional activation by ZntR, a Zn(II)-responsive MerR homologue in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 274:37517-37524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ralston, D. M., and T. V. O'Halloran. 1990. Ultrasensitivity and heavy-metal selectivity of the allosterically modulated MerR transcription complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:3846-3850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ross, W., S. J. Park, and A. O. Summers. 1989. Genetic analysis of transcriptional activation and repression in the Tn21 mer operon. J. Bacteriol. 171:4009-4018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmidt, T. G., and A. Skerra. 1994. One-step affinity purification of bacterially produced proteins by means of the “Strep-tag” and immobilized recombinant core streptavidin. J. Chromatogr. A 676:337-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scott, R. A. (ed.). 2000. X-ray absorption spectroscopy. University Science, Sausalito, Calif.

- 22.Shewchuk, L. M., J. D. Helmann, W. Ross, S. J. Park, A. O. Summers, and C. T. Walsh. 1989. Transcriptional switching by the MerR protein: activation and repression mutants implicate distinct DNA and mercury(II) binding domains. Biochemistry 28:2340-2344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shewchuk, L. M., G. L. Verdine, H. Nash, and C. T. Walsh. 1989. Mutagenesis of the cysteines in the metalloregulatory protein MerR indicates that a metal-bridged dimer activates transcription. Biochemistry 28:6140-6145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shi, W., J. Dong, R. A. Scott, M. Y. Ksenzenko, and B. P. Rosen. 1996. The role of arsenic-thiol interactions in metalloregulation of the ars operon. J. Biol. Chem. 271:9291-9297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Skerra, A., and T. G. Schmidt. 2000. Use of the Strep-tag and streptavidin for detection and purification of recombinant proteins. Methods Enzymol. 326:271-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stoyanov, J. V., J. L. Hobman, and N. L. Brown. 2001. CueR (YbbI) of Escherichia coli is a MerR family regulator controlling expression of the copper exporter CopA. Mol. Microbiol. 39:502-511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Summers, A. O. 1992. Untwist and shout: a heavy metal-responsive transcriptional regulator. J. Bacteriol. 174:3097-3101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Utschig, L. M., J. G. Wright, and T. V. O'Halloran. 1993. Biochemical and spectroscopic probes of mercury(II) coordination environments in proteins. Methods Enzymol. 226:71-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wright, J. G. 1991. Doctoral dissertation. Northwestern University, Chicago, Ill.

- 30.Wright, J. G., S. L. Johnson, L. M. Utschig, and T. V. O'Halloran. 1990. Coordination chemistry and molecular basis of heavy metal recognition in the metalloregulatory protein, MerR. J. Inorg. Biochem. 43:519. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zeng, Q., C. Stalhandske, M. C. Anderson, R. A. Scott, and A. O. Summers. 1998. The core metal-recognition domain of MerR. Biochemistry 37:15885-15895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]