Abstract

The authors present Relationship Competence Training (RCT), which is an organized conceptual framework developed by them for assessing a family's ability to mobilize their relational support in times of distress. RTC is a process of studying family relationship patterns and how these patterns influence family health. The RTC model is described as a method of promoting mental health as a part of everyday family health, which is suitable for health care providers working in a wide variety of environments who have in common the desire to offer continuity and value in promoting the health of the families under their care. RCT provides an empathic way of dealing with the “compassion fatigue” that health care providers often experience when managing complex family health issues in constantly changing and quality-strained primary health care environments.

Large gaps between the care that patients and their families should receive and the care that they actually receive exist within our health care environment.1 The provision of quality mental health care for all who could benefit from it falls below standard in our country.2 Primary care today is referred to as the de facto mental health delivery system, where most Americans prefer to deal with their mental health needs.3,4

It is estimated that, in the United States alone, 50% of primary care office visits involve a mental health–related concern.5–8 Four of the 10 leading causes of disability in the United States are mental health conditions, and these conditions rank second to cardiovascular disease in contributing to life years lost to disability.9 Depression is the most common primary care mental health diagnosis, yet it is often undiagnosed and undertreated.3,10,11,12 Only 28% of patients and families who suffer from mental health problems seek professional help, and of those, only 40% reach a practitioner who is trained to diagnose and treat these disorders.3,13 Therefore, the majority of undiagnosed or undertreated patients and their family members are visiting their primary care offices with unrecognized or somatized medical complaints.14–16 These mental health–related concerns not only distress the family, but also exhaust the patience and empathy of the office staff and the health care providers.17,18 They place an overwhelming burden and cost on primary care providers and systems to respond to complicated mental health concerns.19,20 This burden is projected to continue into the year 2020 when depression is projected to be the second leading cause of disability in the world.9 The urgency of these family mental health facts supports the timely development of collaborative care models that address the need for integrated care that focuses on building family strength.

The Surgeon General's landmark report2 on mental health defines a vision for the future, which includes integration as the potential course of action needed to promote balanced health. The recent “Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century” report1 of the Institute of Medicine recommends that the health care industry redesign the delivery of care by focusing on the priority health conditions that create burdens for the population in need. Therefore, a leading goal of a public health focus for the integration of mental health as a part of everyday primary care would be to improve family functioning and reduce the risk of disability. Relationship Competence Training (RCT) offers a systemic approach to integration, which is accomplished by defining the population in need, tracking the process of coordinated care, measuring the cost and efficacy of collaborative interventions, and redesigning the health delivery system to match what the patient and family have defined as culturally necessary to improve their quality of life.

Integration is defined as the incorporation of different groups or systems within a common framework of values and principles.21 Collaboration is the process by which integration is implemented. Collaborative care models that include training in the continuous quality improvement principles of defining, measuring, and tracking the process of care into their design have improved the potential for increasing the value of care for the treatment of mental health disorders within primary care.20,22–26

The incorporation of collaborative training for appropriate diagnosis and treatment of depression and other mental health conditions in the primary care setting could improve families' psychological and health functional status and reduce health care utilization for nonpsychiatric reasons.24,27–29

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK FOR RELATIONSHIP COMPETENCE

The Relationship Competence Training model describes a collaborative care process of rebuilding family relationship competencies as a primary health intervention. In RCT, relationship competence is defined as the ability to identify a need and mobilize available relationship resources to develop a collaborative strategy that will result in improved health status. Relationship competence is a sustainable resource that can promote long-term family health management skills and prevent the increase of mental health risk associated with a health condition or disability. This view of relationship competence is consistent with the Surgeon General's definition of mental health as “a state of successful performance of mental and physical functioning resulting in productive activities, fulfilling relationships with others, and the ability to adapt to change and cope with adversity.”2 Promoting care that is based on continuous healing relationships is 1 of the 10 new rules proposed by the Institute of Medicine for redesigning health care processes.1

Families are at the heart of our health care systems. They may be the stabilizing force for an individual's health, or they may create and promote complicating factors that result in poor compliance and responsiveness to necessary health care interventions. For the first time in the history of American family life, having “family-related issues” is one of the leading causes of absenteeism from work.30 These family-related issues are stressing the very fabric of our daily life and lead to the deterioration of healthy lifestyles within our communities.

Family-related issues have a pervasive influence on health care practices, schools, justice systems, and work environments. To address such issues, families turn most often to their primary care providers with whom they often develop long-term relationships. These helping relationships become a consistent part of the family's support network and are called on to solve health issues. The primary care provider, therefore, is placed in an influential position of trust not only as the giver of care, but as a mentor who is capable of providing a normalizing framework through which the family can cope with difficult health issues. As facilitators and educators, primary care providers can prepare the family for the emotional process of receiving help. Through their helping relationships, they encourage family members to accept and utilize available care at appropriate times. In other words, health care providers intuitively try to help families build competent strategies to cope with health issues, and there is a need for a practical, teachable, and theoretically coherent model that is applicable to the primary care context. This article describes such a model, RCT, and illustrates its usefulness in managing difficult family issues in primary care.

RELATIONSHIP COMPETENCE TRAINING

Relationship Competence Training introduces a standardized collaborative method of identifying, tracking, managing, and building sustainable relationship resources for individuals within their families and communities. The RCT process of collaborative care is guided by the relationship competence approach, which is the study of interactional relationship patterns in groups, families, and systems and their subsequent impact on individual health behaviors. RCT promotes integration and collaboration through the process of empathy. Empathy facilitates growth in helping relationships.31 RCT focuses on teaching and managing empathic responses with the goal of improving patient and family compliance and satisfaction with care. When patients and their families experience a genuine sense of being cared for, understood, and valued in the helping relationship, they are more likely to adhere to and collaborate with treatment goals.

Clinical research has determined that the therapeutic alliance has a greater effect on patient compliance than the actual health care intervention.5 For example, irritable, depressed patients require time and attention that primary care providers may have difficulty providing as they try to respond empathically to multiple, nonresponsive somatic complaints. RCT helps providers and families identify their responses to difficult health issues and identify relationship competencies that will guide the design of meaningful and measurable family health outcomes.47 This system was developed as a tool for managing difficult experiences in the helping relationship.

HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF RCT

During the 1980s, the lead author (B.R.-B.), operating within an outpatient mental health team in collaboration with referring primary care physicians and nurses, began to define and track what was then called the “difficult family profile.” Tracking the profile was accomplished through clinical observations and analyzing videotapes of initial clinical interviews of families referred to mental health providers by their primary care provider. In this initial tracking and analysis process, the team found that the family's systemic presentation of suffering did not fit into the individual-oriented psychiatric or medical diagnoses that were available. Rather, the clinical observations revealed that the families who were “difficult to treat” shared a similar profile. For example, these families commonly demanded time and follow through due to their complicated medical and emotional histories. They also required extensive collaboration between providers, schools, courts, and other community services. Their difficult-to-treat profile almost always increased the likelihood that they would get lost in or avoided by the system. The team even found that when services were clearly made available and defined for the families, they would resist or simply not comply with even the most logical treatment goals.

Clearly, resistance to the helping relationship was a tremendous challenge for the clinicians. Clinicians often experienced a sense of failure in their inability to develop a therapeutic alliance with the family due to chronic relationship difficulties. Recurring symptoms such as depression, anxiety, or somatization often masked the family's relationship difficulties. It did not take long during the course of a busy “clinic day life” for these family interactions to exhaust the patience and empathy of the office staff. System-wide reflections of how difficult family life was at home were often recreated in the primary care office.

As the team developed insight into the needs of the families, it became clear that an equally affected population that required attention and support were the providers and support staff. Providers were becoming exhausted, confused, irritable, apathetic, and fatigued. High staff dissatisfaction and turnover, inability to manage time and productivity, and ineffective clinical interventions ensued. These provider symptoms were observed as clues that clinicians were in need of support, consultation, and training that would enhance their diagnostic and management skills and prevent “compassion fatigue.”

The team felt confident that if they could identify and understand the factors that negatively influenced the therapeutic relationship between the family and the helping provider, they would be able to impact dropout, relapse, and treatment satisfaction outcomes. In other words, the team felt certain that provider exhaustion and fatigue were influencing poor patient health outcomes and influencing family noncompliance. Careful systemic analysis of these therapeutic barriers to treating relationship difficulties suggests that the lack of empathy in the interactional process of the helping relationship negatively influences the family's ability to adhere to treatment goals.

One of the key observational findings revealed that as families were referred for help, they had common symptoms, but responded differently to the therapeutic relationship. Their differential responses appeared to be strongly related to the families' relationship styles and not the symptoms for which they were referred. These varying styles influenced the family's capacity to engage in the helping relationship. The observed family responses were classified into family profiles and organized into the “Classification System of Family Relationship Patterns.”18 This tool helps both providers and families identify the family's relationship style and organize culturally sensitive treatment goals, which match the providers' and families' natural relational abilities. This work provided the clinical foundation for the development of RCT.

THEORETICAL FOUNDATION FOR RCT

The Relationship Competence Training approach involves the study of interactional relationship patterns in families and the impact of these patterns on health behaviors. In addition, RCT provides tools to improve families' abilities to manage the health of their members. The RCT approach integrates key theoretical ideas from attachment, family systems, and object relations theories. The attachment theory emphasizes the basic human need for protection, safety, and feelings of security and the role these needs have in promoting healthy development.32 Critical in the development of secure attachment is sensitive caregiving, that is, caregiving that is based on empathic understanding of a child's emotional needs.31 In addition, the attachment theory proposes that early relational experiences are internalized and organized into patterns that theorists call internal working models.33 Studies indicate that these patterns are stable over time, at least when the family environment remains stable, and predictive of important aspects of children's emotional development.34,35

The family systems theory supports the notion that individuals grow in the context of interdependent relational systems that are in constant pursuit of homeostasis and balance.32,36 All systems have a regulatory process, which provides stability for ongoing adaptations to ecological change forces. A family's homeostasis is grounded in its culture. Family culture is not simply ethnicity, but a complex set of beliefs that capture the system's history, health, spirituality, economic status, social and political values, and emotional relatedness. Cultural patterns reinforce the strength of homeostatic forces and naturally produce resistance to change. Normalizing the resistant forces within a family system can promote natural restoration of balance through respecting the family's culturally sensitive needs and readiness to change.

Finally, similar to the attachment theory, the object relations theory also sees early relationships as influential.37 The object relations theory adds a stronger emphasis on the way our perceptions of others are strongly colored by affective experiences, particularly unmet emotional needs. Furthermore, it focuses on emotional experiences that evoke painful anxiety and are therefore put out of awareness.38 Such experiences are thought to exert a powerful influence on current relationships by distorting the perceptions of others, particularly in times of distress or emotional need.

A common thread in all 3 theories involves the understanding that the family relational environment is influential in shaping the individual's capacities to engage in and form meaningful and satisfying relationships later in life. Furthermore, all 3 approaches underscore the developmental and patterned nature of relationships and their relative stability, whether growth promoting or less optimal. Such relationship patterns provide predictability and a sense of familiarity and balance for the developing family and, consequently, are likely to be resistant to change. This resistance may not be confined to only one generation. Rather, relationship patterns are passed on through generations,39 and emotional traumas that are not treated in one generation are likely to be passed on to the next generation.40

RELATIONSHIP PATTERN DIAGNOSIS

Through Relationship Competence Training, families are educated about some of the mental health concepts presented above, but always through the use of language that applies directly to the nature of their family relationship patterns. For example, families learn about “internal working models” called their family “blueprints.” They also learn how this blueprint provides a sense of stability and familiarity, but that it may compromise how they cope with current health difficulties or developmental processes. The “blueprint” concept is also extremely helpful in designing interventions that match the family's pattern and “natural” capabilities and is very useful in predicting realistic outcomes that anticipate the family's needs rather than reacting to them. To understand different family styles of engagement, we have identified 3 family relationship patterns that serve as the cornerstone of the RCT approach (Table 1).

Table 1.

Family Relationship Pattern Diagnosis in Relationship Competence Training

The first family relationship pattern is the Disconnected/Avoidant family pattern. The families who follow this pattern tend to hide their psychological stress within their family or mask it with physical symptoms. One member of the family is usually identified as “sick” or “in need of being fixed.” They usually avoid helping relationships, preferring to handle things on their own and tend to isolate themselves from available support systems. This engagement style often forces families to seek help. They are frequently annoyed or irritated by their health problem. It appears that this relationship style is based on fear related to rejection, neglect, or unmet emotional needs and is demonstrated by their embarrassed discomfort in asking for or accepting help.

The second family relationship pattern is the Confused/Chaotic family pattern. The engagement style of families who follow this pattern involves repeated crises and neediness. The families tend to attach quickly to multiple providers, while projecting their chaos onto the health care system. Consequently, it is common for these families' support systems to seem burned-out and exhausted. These families are frequently confused and panicked regarding their health problems. They demonstrate difficulty in organizing a consistent strategy or plan of action to deal with the chronic nature of their problems. It appears that this relationship pattern is based on a history in which emotional needs have been inconsistently met, leading to high levels of anxiety concerning the expression of needs.

The third family relationship pattern is the Secure/Balanced family pattern. The families who follow this pattern have a cooperative engagement style and actively seek help in response to distress. They provide a clear and congruent description of their problem and are capable of developing a plan of action to deal with the problem at hand. They rely on the support systems that are available to them and are also able to develop new resources if needed. It appears that this pattern is based on a history in which emotional needs have been, by and large, met or that family members have come to terms with losses, traumas, or frustrating and difficult life experiences.

Three important points need to be made regarding the patterns described above. First, families can have characteristics of all 3 patterns, but careful examination over time reveals that 1 pattern remains dominant. In other words, the unit of analysis involves relational patterns, not individual family members' characteristics. Second, families whose characteristics resemble 1 of the 3 patterns can be struggling with similar health conditions such as depression, suicide attempts, anxiety, somatic complaints, or chronic illness. They differ in how they identify the stress, ask for help, and cope with their health condition. Third, the goal of RCT is to help each family build competencies within their natural pattern that help them manage their identified health concerns.

THE ASSESSMENT PROCESS

As described earlier in the article, families see their primary health provider for a variety of health needs including mental health–related issues. Resources for detection and screening for mental health issues are typically not readily available and may create more work for the already busy provider. The provider who has been trained in the RCT approach uses his or her expanded clinical intuition to assess the readiness of the patient and family to accept help for the health condition and its mental health–related concerns. As families grow and change, they are in continuous need of information and educational preparation for the early identification of health problems. The primary care providers (PCPs) who know their families well will be able to assess the families' emotional and social readiness to deal with delicate health facts related to mental health. The RCT family patterns model helps the clinician organize an empathic response to a family's symptoms and prepare them for a collaborative team approach to their health issue.

The next step involves having the family complete self-report measures of psychological and general health status, as well as a Family Pattern Profile Form (Appendix 1). These measures may be administered in the primary care office or upon referral to a mental health specialty service. The Family Pattern Profile Form is completed by the family member who is identified as the patient and other family members who are actively providing continuous and significant relational support to the patient. This self-report profile describes how the family asks for help when distressed, patient's memories of early childhood relationships, and the patient and family's current relationship support. In addition, brief descriptions of the 3 family patterns are provided, and family members are asked to choose the pattern that most resembles the current relationship style of their family.

The form introduces families to a non-stigmatizing way of looking at emotional and physical health symptoms in the context of their natural style of responding to distress. Families bring the completed forms to their initial interview with their integrated primary mental health provider. During this interview, the family is asked to identify the reason for referral, and the results of their self-reported measurements are discussed and used to establish a relationship pattern diagnosis. This diagnosis is based on the family's self-report and the clinician's examination of the family's relationship style across 4 domains (see Table 1).

The first domain measures how the family engages in the helping relationship in times of distress. Observed engagement behaviors are a window from which to see how family and community life have influenced the family's ability to ask for and use help when they need it. The second domain of measurement is the provider's affective response to the family's engagement behavior. This domain helps the provider identify, organize, and manage his or her own feelings that are evoked during the process of trying to help the family. Successfully managing these feelings helps to remove “empathetic blocks” that directly impact the probability of treatment compliance.

The third domain of assessment is the family's history of relationship. This is measured through the use of a clinical Family Developmental Interview Form, which is completed by the family members (available from the authors upon request). Through the use of a series of developmental questions, family members are typically asked by the mental health provider to remember their perception of their family relationship history. The ability to historically link family strengths and difficulties to current distress gives the family a sense of hope and understanding that helps guide their motivation to learn new health behaviors.

The fourth domain assesses the family's perception of the availability of their defined support system and whether they use this support in times of need. Families and individuals who do not use their support system are at greater risk for continued mental health problems. This domain helps to determine how isolated the family is with their health concerns and the extent to which relationship resources need to be reestablished or rebuilt.

The 4 domains of assessment are used to help the family and the provider determine the relationship pattern diagnosis. Congruence across the domains improves the provider's ability to read the family's unique life story. If the provider is able to understand the family's experience of distress, the probability that the helping interaction will evoke empathy and result in a collaborative strategy to address the family's health needs is directly increased. Through this interaction, the family experiences the provider as caring about them and knowing them well.

Once a family relationship pattern diagnosis has been established, it is linked with the patient's medical and psychiatric diagnoses to develop a comprehensive integrated treatment plan. The family consents to collaborative interventions and communications regarding their care. The provider and the family use the relationship pattern diagnosis to prepare and predict the family's natural compliance response to their identified health problems. Health problems are not limited to depression or anxiety but include complex chronic conditions such as diabetes, asthma, hypertension, and other comorbid illnesses. Organizing care for patients with chronic disease improves the potential for long-term health benefits.25 The provider continues to screen for these disease-specific conditions and then utilizes the RCT diagnosis to understand how this disease will affect patients and their family (or support system) and how to best approach them with the information they need to know to manage their health condition.

Predictions of compliance with recommended treatment are discussed with each family, and a collaborative action plan necessary to support follow through is determined and accessed by an onsite, integrated team. The collaborative integrated team includes the PCP, the mental health specialist, a nurse care manager, and clinic support staff. The provider reviews with the family a list of RCT integration guidelines that is matched to the family's relationship pattern, which will help the family understand the compliance strategies that will be used by the team to manage their current illness. These RCT guidelines provide a normalizing language, which facilitates communication between the family, their PCP, their mental health provider, and other significant resources. The nurse care manager provides critical communication links for the patient and the patient's family to achieve their identified health goals. The nurse care manager uses the RCT guidelines to tailor educational and self-management information to the family's compliance capacity. Advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs) and nurse care managers are important and effective members of the integrated team, providing diagnostic and care management interventions that improve the quality and outcome of care.41–44

Care outcome measures of improvement or non-responsiveness are tracked by the nurse care manager using repeat functional status measures and patient and family satisfaction measures. The care manager facilitates communication between the family and their primary care provider. These outcomes are used to reevaluate or confirm the integrated treatment plan and are readily available for review by the family and the provider.

IMPLEMENTING RCT IN PRIMARY CARE

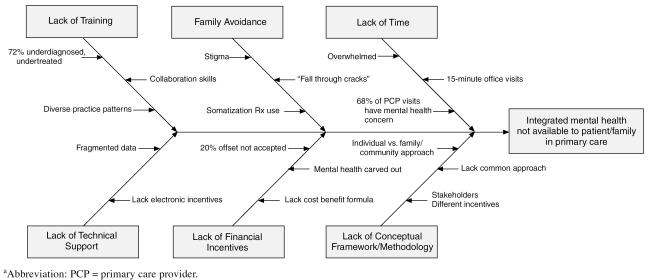

As seen in Figure 1, there are many complex barriers that impede the integration of mental health services in primary care. The stigma and fear of mental illness are still listed as the leading barriers to adequate care.2,45 The stigma of mental illness can lead to family mistrust in mental health interventions, which contributes to the family's avoidance of dealing with the mental health component of their illness. Often, patients and their families mention a mental health concern at the end of a medical visit, which typically lasts approximately 15 minutes. This delay in mentioning the concern creates a significant barrier for the provider who does not have adequate time or training to address the complexity of the family's mental health issue. During the short medical visit, providers are faced with competing demands, and if they ask the appropriate questions, they have neither the time nor the support available to meet the family's needs.46 Of major concern for both the family and the provider are the financial disincentives to diagnose and treat mental health disorders in the primary care setting because reimbursement and coverage for these services are restrictive or nonexistent.47 In many settings, it is time-consuming and financially prohibitive to track functional outcomes. Therefore, practices are limited to reporting on unintegrated data sets such as medical records and claims data for pseudoreliable outcomes. Tracking outcomes can inadvertently be perceived as a barrier to care because it is costly, cumbersome, and time-consuming. Many health systems do not have the funding needed to develop technologically state-of-the-art, integrated, and protected data sets.

Figure 1.

Primary Mental Health Integration Cause and Effect Diagrama

It is not surprising that compliance and non-responsiveness are major health care burdens and concerns.23,48 Families with priority health conditions seem to fall through the cracks of the unintegrated systems, shifting the cost and burden of their unmet needs to other community systems, such as the courts and schools. Feedback from the mental health provider to the primary care provider is rare. At the heart of these collective barriers is the lack of a conceptual framework that builds a consensual, common vision of values and principles and guides the development of a strategic plan from which to organize, implement, and measure system change. The Institute of Medicine presents a promising framework for redesigning quality care that is evidence based, patient centered, and systems oriented.1

Implementation requires careful planning with collaborative, system-wide input to address the complex issues involved when attempting to integrate the processes of clinical care. The first step in implementing a collaborative approach that integrates mental health into primary care practices is to identify the needs of the population being served. This public health focus requires a consensus of common values and goals with sensitivity to the cultural diversity of the population being served. The next step is to build an integration guidance team that reflects active representation of all the stakeholders who have invested in the benefits of quality family health care including family consumers, community leaders, and front-line service and administrative directors.

The team begins to develop its collaborative relationship by building consensus for a mission, an operational work plan, and an evaluation strategy based on continuous quality improvement principles of measuring the process of care and promoting the benefits and value of quality. System and community leaders provide ongoing input and political guidance to the integrated conceptual plan. The process of implementation will generate naturally resistant forces that may create imbalance, uncertainty, and even possibly fear as the 2 worlds of mental health and primary care begin to merge under their common mission of improving family health. As discussed earlier regarding family systems theory, the normalization of resistance as a natural, predictive, and energizing phenomenon of a systems-regulatory mechanism can be used to promote change and restore balance.

One of the key ingredients necessary to support and facilitate the change processes inherent in integration is a substantial investment in training, research, and technological resources to prepare and sustain the system for the impact of mainstreaming mental health as a part of everyday family health care. RCT is one example of a method of training that facilitates the changes required to build integrated collaborative care teams. The conceptual framework of rebuilding family relationship competencies as a primary health intervention promotes the overall systemic goal of improving family health. The family relationship pattern diagnosis provides a method for treating the underlying distress of a family's illness, while reducing the fear and stigma associated with integrating mental health into everyday primary care. Training is one of many ongoing first steps toward preparing a system for integration and reducing predictable resistant barriers.

EDUCATIONAL TRACKS

Relationship Competence Training is currently organized into 4 educational tracks, which include a series of lectures, video case examples, and standardized family compliance management protocols. These educational tracks include Primary Care Collaborative RCT (designed for primary care providers and support staff), Relationship Competence Therapy Training (designed for mental health professionals), Consumer/Family Relationship Competence Training (designed for the family's use at home), and Employer/Employee Relationship Competence Training (designed for use in the workplace) (available from the authors upon request). The RCT training curriculum is also being developed for academic and justice systems.

This article has focused on the RCT featured in Primary Care Collaborative RCT, designed for physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, onsite mental health clinicians, and medical office staff. Using the RCT framework, PCPs and their staff are taught how to screen, manage, and talk to families about “difficult” mental health problems. Training is provided onsite and in coordination with case management collaboration. Providers develop screening and diagnostic skills that enable them to design an integrated treatment plan in partnership with the family and to collaborate as a member of the primary mental health integrated team.

With 33% to 50% of mental health diagnoses being missed in the primary care visit,49 training primary care providers to improve their screening and detection strategies is a major initiative of integrated care. This is somewhat difficult in that many physicians have diverse and persistent practice patterns that they have developed over the years and are often reluctant to change. Primary care providers trained in the RCT method are encouraged to use their existing diagnostic skills to help the family understand their health concern in the context of the RCT relationship diagnosis. The provider in collaboration with support staff uses simple relational language to talk with the family about their mental health concerns. This allows the provider to discuss prevention and compliance predictions directly and empathically with the family based on the family's natural relational ability to ask for help. The PCP uses this educational intervention to help prepare the patient and family to accept the mental health needs related to their illness. The rebuilding family competency focus moves the provider from a single isolated disease-specific diagnosis to a more comprehensive functional improvement strategy, which incorporates the disease facts with the family's capacity to build “managed wellness.” This functional approach will ultimately help the family reduce the long-term disability and relapse associated with their illness by helping them engage in reliable and immediate access to collaborative integrated support.

Case Study

Mrs. K calls the family practice for a follow-up visit for migraine headaches and repeated urinary tract infection. When asked, she explains that the reason for her visit is that the medication she is taking is not enough and is not working. The receptionist notes that Mrs. K is highly agitated and irritable on the phone, and, according to screening protocol, alerts the nurse that this is Mrs. K's sixth visit to the clinic in the last month and she continues to be unresponsive to medications. The receptionist acknowledges the patient's frustration and schedules her for a 30-minute visit to allow the provider time to address the potential mental health component of Mrs. K's symptoms. Unable to obtain childcare, Mrs. K arrives in the busy clinic with her 4 children who are also irritable. The nursing staff has prepared for the chaos that usually accompanies this family's visits and has made available a room for them to wait so that other patients in the waiting room, who do not feel well either, are not disrupted.

While waiting for the physician, the nurse prepares Mrs. K by acknowledging that this is her sixth visit and how frustrating it must be for her that she is still not feeling better. The nurse conveys that Dr. H will want to talk with her today about why nothing seems to be working and how her illness is affecting her both emotionally and physically. In order to prepare for this, she is asked to complete a family pattern profile form and a physical health form to measure how her headaches are affecting her and her family. This information helps Dr. H and Mrs. K decide what should be done next to help her. Dr. H's support staff prepares him for this “mental health–related visit.”

Dr. H engages Mrs. K directly by empathizing with her current frustration that “nothing works” and reviews the self-reported Confused/Chaotic family pattern with her. They agree together that Mrs. K is naturally inconsistent in her ability to follow through with Dr. H's prescribed interventions. Dr. H concurrently reviews with Mrs. K her self-reported poor health status score, which reflects a significant indicator of poor mental health. He prepares Mrs. K directly for the possibility of a mental health condition such as depression, which may be complicating her headaches, and he questions whether she would be willing to see a member of his integrated team to help with further evaluation. Mrs. K is grateful for her mental health diagnosis, but it may be difficult for her to follow through, as predicted for her based on her relationship pattern diagnosis. She is, therefore, introduced immediately to the integrated nurse care manager who will help her schedule the onsite mental health evaluation. The care manager then coordinates compliance feedback with Dr. H.

With the help of the nurse care manager, Mrs. K is able to arrange child care and follow through with a formal mental health evaluation at her primary care clinic, and her depression diagnosis is confirmed. At this visit, her medication is reevaluated to treat both her depression and her migraines. The care manager repeats the functional measures to track her improvement and follows up with her by phone to check on medication compliance, being sensitive to Mrs. K's identified and predictable chaotic home life. Mrs. K attends several mental health appointments and learns new strategies for improving the family bedtime routine, which improves the sleep deficits associated with her depression.

This case example demonstrates how the RCT language promotes collaborative support and direction for the integrated team. The integrated team was instrumental in helping this patient identify, treat, and manage her depression in the context of her complicated and chaotic family life. Instead of her chaos disrupting the busy clinic, it was identified and accepted as normal for this family, and the staff and physician were able to address the health issues directly instead of making them worse by ignoring or avoiding her chaos.

THE IMPACT OF RCT

The Relationship Competence Training standardized method has been successfully implemented in a small family practice of 12 PCPs and 50 support staff that cares for approximately 35,000 patients and their families each year.50,51

Providers received Primary Care Collaborative RCT and, as a team, decided how they would like the mental health needs of their family population met. They chose depression as their most frequent mental health symptom and noncompliance as their most troubling issue. For a 6-month period in 1998 (January–June), claims data were tracked, and 1800 of the primary care visits were noted to be for depression. This figure accounted for only the visits that listed depression as the primary concern and did not include other mental health–related concerns such as fatigue and insomnia. The medical charts of these patients were randomly selected for review. Eighty-eight percent of these patients were married, employed, and had some form of insurance coverage. The majority of the patients were over the age of 40. Ninety percent of the patients were being treated in primary care with medication for depression, and 39% had been referred for mental health treatment. Of the patients referred to integrated RCT-trained mental health providers, 92% showed up for their first appointment compared with a national referral follow-through rate of 50%.6,47

Outcome measurements before and after mental health treatment showed a reduction in anxiety and depression scores and an improvement in perceived general health functioning.50,51 Patients reported high levels of satisfaction as measured by the Mental Health Statistical Improvement Program consumer survey.52 Providers who completed 12 hours of continuous training over a 6- to 9-month period reported an improved capacity for empathy and hope and a reduction in exhaustion and frustration when managing family issues and difficult health behaviors. Providers also reported increased skill in identifying and diagnosing mental health issues.

Finally, the RCT method has provided a standardized way to track the quality and cost of integrated care. Cost trends show a reduction in primary care and mental health costs and a reduction in prescription cost during the 3-year period since RCT was initiated.50,51 Families who rated themselves with a Confused/Chaotic family relationship pattern showed the most cost reduction over time. There is a potential for medical cost offsets when treating mental health conditions appropriately as a part of integrated quality primary care.47,53–55 Further study is needed to build a financial formula that fairly reflects the cost and subsequent value of improving family health through mental health integration.

These preliminary findings provide the foundation for evidence-based outcomes that will be used to replicate and further study the impact of the relationship competence method on the delivery of quality care for primary care practices.56

SUMMARY

Understanding the health of a population of people is influenced by cultural diversity, illness distribution, and the environmental nature of the community in which they live. Populations are networks of communities, communities are networks of families, and families are networks of relationships. Relationships are defined as regularities of patterns of interaction over time and are predictive of individual behaviors.57 This article reviewed the process of using a relationship competence model as a primary health intervention for integrating mental health into primary care. Integration was described as a solution for managing the difficult family issues that are presented in primary care and often interfere with rebuilding family health.

Throughout the health care system today, providers are becoming increasingly frustrated with increased demands and expectations, lack of training, lack of time, and lack of reasonable reimbursement in unintegrated, poor quality health care systems. Their frustration leads to a pervasive sense of not being valued in a career or profession that they chose with the intent of caring for others. This and other barriers to implementing integration were discussed, and recommendations were made to prepare the health care system to respond to the inevitable forces of change that will accompany the needed system redesign.

Health care systems of many countries are going through rapid change on a daily basis. Technology and politics are transforming the way we deliver care and pay for it. Given a chance, systems will restore themselves toward balance.58 This is an underlying principle of ecological science. The RCT language of building sustainable relationship competencies was presented as a conceptual framework, which provides contextual holding, while a system adapts to the process of integration and eventually attains ecological balance.

In summary, a common framework of rebuilding family health and collaborative teams has resulted in successful integration. The use of a practical language with effective protocols has resulted in collaborative relationship development and improved patient and family functioning. It appears that integrated practices may promote the best potential for cost savings and determining the value of quality care. The valuable, sustainable, and available resources of relationships can reinforce our competencies as individuals, families, and communities. Relational competencies can be used to mobilize the collective energy needed to improve family health. World health leaders must organize and develop policy that will support the development of systemic approaches to healthy families and communities and sustain the implementation of integration strategies that demonstrate affordable, evidence-based quality care.

Appendix 1.

Family Pattern Profile Form

Footnotes

No funding or grant support was provided for this article.

Ms. Reiss-Brennan holds the trademark for Relationship Competence Training in the state of Utah. Drs. Oppenheim and Kirstein report no financial affiliation or other relationship relevant to the subject matter of this article.

REFERENCES

- Quality of Health Care Committee. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- US Dept Health Human Services. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, Md: US Dept Health Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration, Center for Mental Health Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health. 1999 [Google Scholar]

- Reiger DA, Narrow WE, Rae DS, et al. The de facto US mental and addictive disorders service system: epidemiologic catchment area prospective 1-year prevalence rates of disorders and services. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:85–94. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820140007001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annexure J, Katon W, Sullivan M, and et al. The effectiveness of treatments for depressed older adults in primary care. Presented at Exploring Opportunities to Advanced Mental Health Care for an Aging Population, sponsored by the John A. Hartford Foundation; 1997; Rockville, Md. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Mangelsdorff AD. Common symptoms in ambulatory care: incidence, evaluation, therapy, and outcome. Am J Med. 1989;86:262–266. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(89)90293-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White B. Mental health care: from carve-out to collaboration. Fam Pract Manag. 1997;4:32–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherbourne CD, Jackson CA, Meredith LS, et al. Prevalence of comorbid anxiety disorders in primary care outpatients. Arch Fam Med. 1996;5:27–34. doi: 10.1001/archfami.5.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M, Fireman B, Weissman MM, et al. Mental disorders and disability among patients in a primary care group practice. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:1734–1740. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.12.1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray C, Lopez A. The Global Burden of Disease: A Comprehensive Assessment of Mortality and Disability from Diseases, Injuries and Risk Factors in 1990 and Projected to 2020. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard School of Public Health. 1996 [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg L. Treating depression and anxiety in primary care: closing the gap between knowledge and practice. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1080–1084. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199204163261610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whooley MA, Simon GE. Managing depression in medical outpatients. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1942–1950. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200012283432607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon W, Scheulberg H. Epidemiology of depression in primary care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1992;14:237–247. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(92)90094-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Nelson CB, McGonagle KA, et al. The epidemiology of co-occurring addictive and mental disorders: implications for prevention and service utilization. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1996;66:17–31. doi: 10.1037/h0080151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemelin J, Hotz S, Swensen R, et al. Depression in primary care: why do we miss the diagnosis? Can Fam Physician. 1994;40:104–108. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rost K, Zhang M, Fortney J, et al. Persistently poor outcomes of undetected major depression in primary care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1998;20:12–20. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(97)00095-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal P, Bendell E, Aboudarham J, et al. Psychosocial morbidity: the economic burden in a pediatric health maintenance organization sample. Arch Pediatr Adoles Med. 2000;154:261–266. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.3.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein A, Budd M, Cole S. Behavioral disorders: an unrecognized epidemic with implications for providers. HMO Pract. 1995;9:53–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss-Brennan B, Oppenheim D, Vos E. A classification system of family relationship patterns for diagnosing and managing difficult families in psychotherapy. Fam Psychol. 1994;2:11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg PE, Stiglin LE, Finkelstein SN, et al. The economic burden of depression in 1990. J Clin Psychiatry. 1993;54:405–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon W, Robinson P, Von Korff M, et al. A multifaceted intervention to improve treatment of depression in primary care. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:924–932. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830100072009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm M, Howard P, Boyd M, et al. Special report: quality indicators for primary mental health within managed care: a public health focus. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 1997;11:167–181. doi: 10.1016/s0883-9417(97)80024-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Korff M, Katon W, Bush T, et al. Treatment costs, cost offset and cost-effectiveness of collaborative management of depression. Psychosom Med. 1998;60:143–149. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199803000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al. Collaborative management to achieve treatment guidelines: impact on depression in primary care. JAMA. 1995;273:1026–1031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al. Stepped collaborative care for primary care patients with persistent symptoms of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:1109–1115. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.12.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Q. 1996;74:511–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells K, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, et al. Impact of disseminating quality improvement programs for depression in managed primary care. JAMA. 2000;283:33–47. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.2.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel S, Campbell T, Seaburn D. Principles for collaboration between health and mental health providers in primary care. Fam Syst Med. 1995;13:3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Sturm R, Wells KB. How can care for depression become more cost-effective? JAMA. 1995;273:51–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubenstein LV, Jackson-Triche M, Unutzer J, et al. Evidence-based care for depression in managed primary care practices. Health Aff. 1999;18:89–105. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.18.5.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldfogel J. The impact of family medical leave act. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 1999 18:281–301.From Neurons to Neighborhoods: The Science of Early Childhood Development 2000. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheim D, Koren-Karie N, Sagi A. Mother's empathic understanding of their preschoolers' internal experience: relations with early attachment. Int J Behav Dev. 2001;25:16–26. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and Loss, vol 1. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Basic Books. 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bretherton I, Munholland KA. Internal working models in attachment relationships: a construct revisited. In: Cassidy J, Shaver P, eds. Handbook of Attachment. New York, NY: Guilford Press. 2000 89–111. [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA. The coherence of individual development. Am Psychol. 1979;34:834–841. [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff A, Emde R. Relationship Disturbances in Early Childhood. New York, NY: Basic Books. 1989 [Google Scholar]

- Bertalanffy L. General Systems Theory. New York, NY: Braziller. 1968 [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy P. Psychoanalytic theory form the viewpoint of attachment theory and research. In: Cassidy J, Shaver P, eds. Handbook of Attachment. New York, NY: Guilford Press. 2000 595–624. [Google Scholar]

- Slipp S. Object Relations: A Dynamic Bridge Between Individual and Family Treatment. NewYork, NY: Aronson. 1984 [Google Scholar]

- Steele H, Steele M. Intergenerational patterns of attachment: in advance in personal relationships. London, England: Jessica Kingsley. 1994 5:93–120. [Google Scholar]

- Fraiberg S, Adleson E, Shapiro V. Ghosts in the nursery: a psychoanalytic approach to the problems of impaired infant-mother relationships. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 1975;14:387–421. doi: 10.1016/s0002-7138(09)61442-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson B, West J, Pincus H, and et al. An Update of Human Resources in Mental Health Mental Health United States. US Dept Health Human Services publication (DHHS) 96–3098. Rockville, Md: National Institute of Mental Health. 1996:168–204. [Google Scholar]

- Marks I. Controlled trial of psychiatric nurse therapists in primary care. Br Med J. 1985;290:1181–1184. doi: 10.1136/bmj.290.6476.1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunkeler EM, Meresman JF, Hargreaves WA, et al. Efficacy of nurse telehealth care and peer support in augmenting treatment of depression in primary care. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:700–708. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.8.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon GE, VonKorff M, Rutter C, et al. Randomised trial of monitoring, feedback, and management of care by telephone to improve treatment of depression in primary care. BMJ. 2000;320:550–554. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7234.550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefl ME, Prosperi DC. Barriers to mental health service utilization. Community Ment Health J. 1985;21:167–178. doi: 10.1007/BF00754732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rost K, Nutting P, Smith J, et al. The role of competing demands in the treatment provided primary care patients with major depression. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:150–154. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.2.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malek SP. Financial, risk and structural issues related to the integration of behavioral health in primary care settings under managed care [research report]. Seattle, Wash: Milliman & Robertson. 1999 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Arean P, Alvidrez J. Treating depressive disorders: who responds, who does not respond and who do we need to study. Presented at Improving Care for Depression in Organized Health Care Systems; Feb 24–26, 1999; Seattle, Wash. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ES. A review of unrecognized mental illness in primary care: prevalence, natural history, and efforts to change the course. Arch Fam Med. 1994;3:908–917. doi: 10.1001/archfami.3.10.908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss-Brennan B, Kirstein J. Mainstreaming collaborative care: cultural change and re-engineering clinical processes. Presented at the Primary Care Behavioral Health Summit: Behavioral Health Care Tomorrow; June 18–20, 1998; San Antonio, Tex. [Google Scholar]

- Reiss-Brennan B, Kirstein J. Improving family health: the practice of collaborative care. Presented at the International Congress of Improving Family Health; Nov 21, 1998; Regio Emilia, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- Mental Health Statistical Improvement Program (MHSIP): Consumer Survey. MHSIP Consumer Oriented Report Card. Rockville, Md: US Department of Health Human Services; Center for Mental Health Services. 1996 [Google Scholar]

- Simon G, Ormel J, VonKorff M, et al. Health care costs associated with depressive and anxiety disorders in primary care. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:352–357. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.3.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon GE, Katzelnick DJ. Depression, use of medical services and cost-offset effects. J Psychosom Res. 1997;42:333–344. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(96)00367-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg R. Financial incentives influencing the integration of mental health care and primary care. Psychiatr Serv. 1999;51:1071–1075. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.8.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosen D, Reiss-Brennan B, and Cannon W. The effect of primary mental health integration on detection of mental health conditions and functional status. Presented at the 50th National Mental Health Statistics Conference; June 2, 2001; Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA. Relationships, self, and individual adaptation. In: Sameroff A, Emde RN, eds. Relationship Disturbances in Early Infancy. New York, NY: Basic Books. 1989 70–124. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins P. The Ecology of Commerce. New York, NY: Harper Collins Publisher. 1993 [Google Scholar]