Abstract

Objective:

To measure tissue-temperature rise in the lateral aspect of the ankle during 10-minute ultrasound treatments with ultrasound gel (gel), a gel pad with a thin layer of ultrasound gel on the top (gel/pad), and a gel pad with a thin layer of ultrasound gel on the top and the bottom coated with ultrasound gel (gel/pad/gel).

Design and Setting:

We used a 1 × 3 repeated-measures, crossover design. The dependent variables were tissue-temperature change and time to peak temperature. The independent variable was the type of ultrasound coupling medium. Treatment orders were randomly assigned, and all possible orders were assigned 3 times. A thermocouple was inserted through a 32-mm catheter at a depth of 1 cm into the target-tissue space, the posterior lateral aspect of the left ankle, halfway between the lateral malleolus and the Achilles tendon. Each treatment consisted of ultrasound delivered topically at 1 W/cm2, 3 MHz, in the continuous mode for 10 minutes.

Subjects:

Eighteen healthy, college-aged student volunteers (13 women, 5 men), with no history of ankle injury in the previous 6 months.

Measurements:

Intratissue temperature, measured every 30 seconds for 10 minutes.

Results:

Intratissue temperature increases during the 10-minute treatments were significantly greater for the ultrasound gel (7.72°C ± 0.52°C) and the gel/pad/gel (6.68°C ± 0.52°C) than for the gel/pad (4.98°C ± 0.52°C).

Conclusions:

When ultrasound is applied over bony prominences, a gel pad should be covered with ultrasound gel on both sides to ensure optimal heating.

Keywords: ultrasound coupling media, phonophoresis

Continuous ultrasound is used to heat tissues,1–6 decrease pain,7–10 decrease inflammation,7,9,11,12 decrease joint stiffness,9,12 decrease muscle spasms,8,9 facilitate the stretch of collagenous fibers,6,12,13 and increase blood flow.9,14,15 It can be applied either directly or indirectly. The direct technique involves applying a thin layer of coupling medium between the skin and the sound head. The coupling medium allows ultrasonic energy to enter the target tissue at the desired intensity by minimizing the air between the transducer head and the tissue16 and serves as a lubricant.16 Ultrasound coupling media include gels, gel pads, creams, water, oil, and mixed media. Previous researchers have demonstrated that gels are more effective for transmitting ultrasonic energy than are other forms of ultrasound coupling agents.2,17–29

The indirect technique is typically used over superficial tissue with bony prominences. The indirect application can be either through the water-immersion method,1,28–30 the bladder method,1,28–30 or the ultrasound gel pad.31 The bladder method is used when the water-immersion method is not feasible because of the location of the treatment area.1,28–30 It is performed by placing a balloon or plastic bag filled with water over the treatment site, covering both sides of the bladder with gel, and then applying ultrasound through the bladder toward the treatment area.1,28–30

The ultrasound gel pad is used in a similar way, but there is controversy about how it should be used. Some experts advise that ultrasound gel should be placed on both sides of the pad, just as if the bladder method were used (C. R. Denegar, PhD, ATC, PT, personal communication, November 2001). Representatives of Parker Laboratories (Fairfield, NJ), the developer of the Aquaflex gel pad, state that this is not necessary and that the only advantage of using gel with the gel pad is to prolong the life of the pad (Parker Laboratories, personal communication, November 2001).

Although ultrasound coupling gels are accepted as the most effective coupling agents,2,17–29 they have not been adequately compared with gel pads. Two in vitro studies24,25 using a gel pad have been conducted on pig tissues. It was reported that the gel pad has the same characteristics as ultrasound coupling gel, except that the gel pad allows for 27% more transmission of ultrasound energy.24 This increase in ultrasonic energy transmission should result in a greater increase in tissue temperature.

Only 1 in vivo study has been conducted on the gel pad.32 Merrick et al32 reported no significant difference in intramuscular heating when using the gel pad or conducting gel during ultrasound. These results have limited application, however. Gel pads are typically intended to replace underwater ultrasound treatments on superficial tissues with bony prominences.31 Merrick et al32 conducted their study on the gastrocnemius muscle, an area where the gel pad would not normally be used, and they applied 1-MHz ultrasound, which is for target tissues of 2.5 to 5 cm deep.29,33 The gel pad, however, is designed to be used as an indirect technique and to target superficial tissues; when the goal is to heat superficial tissues (less than 1 cm deep), 3-MHz ultrasound should be used.29,33

Our study was designed to determine whether the gel pad is an effective coupling agent when 3-MHz ultrasound is applied over small joints and bony prominences and for tissues 1 cm deep. We also wanted to determine if adding gel to both surfaces of the gel pad had an effect on ultrasonic energy transmission over irregular surfaces and if the depth of the groove between the posterior aspect of the lateral malleolus and the anterior aspect of the Achilles tendon affected ultrasound transmission by creating an air pocket.

METHODS

Design

We followed a 1 × 3 repeated-measures, crossover design. The dependent variables were tissue-temperature change and time to peak temperature. The independent variable was the type of ultrasound coupling medium or interface between the sound head and the skin. These consisted of (1) ultrasound gel (gel), (2) gel pad with a thin layer of ultrasound gel on the top (gel/pad), and (3) gel pad with a thin layer of ultrasound gel on the top and the bottom coated in ultrasound gel (gel/ pad/gel). The purpose of the thin layer of ultrasound gel on the top of the pad was to eliminate friction between the sound head and the skin. Subjects drew random numbers that assigned them to 1 of 6 treatment orders, established with two 3 × 3 balanced Latin squares.

Subjects

Eighteen subjects, 13 women and 5 men, ranging from 19 to 27 (mean = 21.61 ± 2.45) years of age, participated in this study. Each subject's ankle and lower leg were free from injury, swelling, ecchymosis, and infection for 6 months before testing as identified by the subject through a medical questionnaire. University institutional review board approval was granted before we recruited subjects, each of whom gave informed consent to participate in the study.

Instruments

An Omnisound 3000 (Accelerated Care Plus, Sparks, NV) ultrasound unit was used for this study. The unit housed a 5-cm2 lead zirconate titanate crystal, with an effective radiating area of 4.0 cm2 and a beam nonuniformity ratio of 3:1, as measured by the manufacturer.

One 20-gauge needle (34 mm long) with a 32-mm catheter (Johnson & Johnson Medical, Arlington, TX) was used to insert a thermocouple in the tissue. The thermocouple34 was connected to an electric thermometer (Iso-Thermex, Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH) and interfaced with a personal computer. The Iso-Thermex has been found to be reliable to ±0.1°C (0.2% of range at 22°C ambient temperature).34 Ultrasound gel (Parker Laboratories), an Aquaflex gel pad with ultrasound gel on the top (Parker Laboratories), and an Aquaflex gel pad with ultrasound gel on both sides served as the conducting media.

Procedures

The target tissue was the posterior lateral aspect of the left ankle halfway between the lateral malleolus and the Achilles tendon. The difference between the highest point of the posterior aspect of the left lateral malleolus and the deepest point in the target tissue (peroneal-groove “depression”) was measured. Each subject lay on the right side so that the body was perpendicular with the table. One arm of the caliper was positioned at the deepest point in the peroneal-groove depression, and the other arm measured the highest point on the malleolus (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Measurement of the peroneal-groove depth. The measurement was taken from the deepest point in the peroneal-groove depression to the highest point on the left lateral malleolus.

A mark was then placed on the target tissue where the thermocouple would be inserted. The subject lay prone with the ankle in an open-packed, relaxed position (foot plantar flexed to 10° to 20°). A 10-cm-diameter area on the left lateral malleolus and lateral aspect of the Achilles tendon was cleansed with a Betadine swab (Purdue Pharma LP, Stamford, CT). The thermocouple was inserted via a catheter to a depth of 1 cm. The catheter was then extracted, and the thermocouple was taped to the subject's leg to prevent movement (Figure 2). After the thermocouple was inserted and connected to the Iso-Thermex, we waited for the intratissue temperature to reach baseline (defined as no change greater than ±0.1°C over 2 minutes). Room temperature remained between 22°C and 23°C, with 18% to 23% humidity.

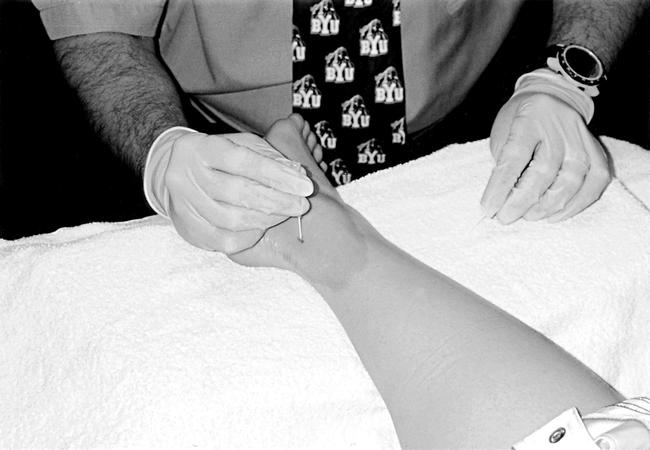

Figure 2.

Insertion of the catheter. The groove between the left lateral malleolus and the Achilles tendon served as the target tissue.

Ultrasound was applied to each subject's left lateral ankle for 10 minutes with the following settings: continuous mode, 1 W/cm2, 3-MHz frequency. Each subject was instructed to respond if the ultrasound treatment became uncomfortable at any time. Each subject received all 3 treatments in 1 setting; however, we waited for the temperature to reach baseline after each treatment before initiating the next treatment. The typical length of time spent waiting between treatments was approximately 12–20 minutes.

When the gel treatment was performed, ultrasound gel was applied to cover the treatment area. When the gel/pad treatment was being performed, the pad was placed directly over the treatment area. A thin layer of ultrasound gel was applied to the top of the gel pad in order to allow the sound head to move freely. When the gel/pad/gel treatment was given, ultrasound gel was applied to both sides of the pad. Because the high-frequency acoustic waves of ultrasound cannot be transmitted into the tissues through air,35 enough ultrasound gel was applied to the bottom of the gel pad to ensure that no air pockets were between the gel pad and the tissue. It has been suggested by some that the Aquaflex gel pad lasts for approximately 5 treatments.31 Therefore, we used each pad for only 4 treatments (2 treatments on 2 subjects) and then discarded it, so as to increase the likelihood that each subject had a premium Aquaflex gel pad for each treatment.

To guarantee consistency among ultrasound treatments, a template was placed on the gel pad or on the skin, depending upon the treatment given (Figures 3 and 4). The size of the template was 2 times the size of the effective radiating area of the sound head (4 cm2). The ultrasound head was moved over the treatment area at a rate of 4 cm/s. A metronome was used to help monitor the pace of the ultrasound application (4 cm/s).

Figure 3.

Ultrasound treatment with ultrasound gel.

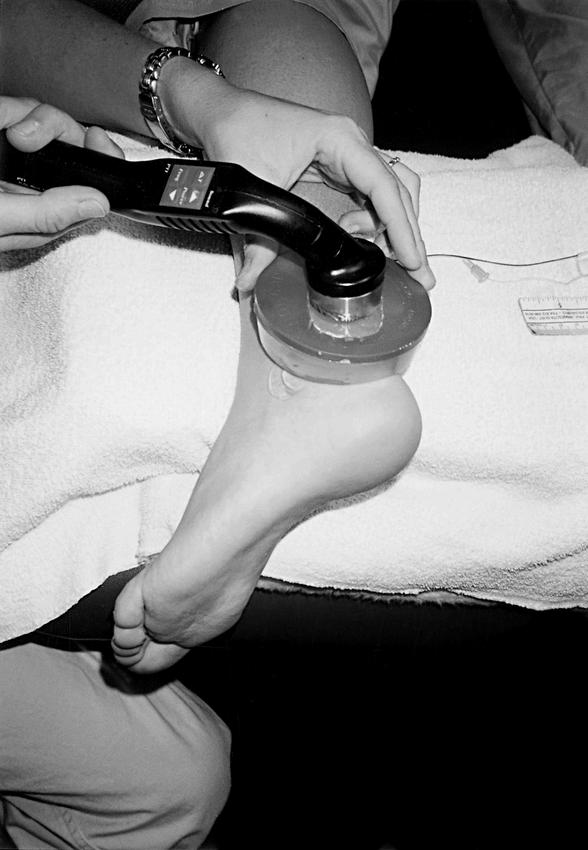

Figure 4.

Ultrasound treatment with the Aquaflex gel pad coated with ultrasound gel. This was repeated without ultrasound gel.

Tissue temperature was recorded every 30 seconds during each treatment. At the end of the treatment, tissue-temperature decrease was monitored until baseline was reached (no change greater than ±0.1°C over 2 minutes). Once the posttreatment baseline had been established, the next treatment was administered. At the completion of each participant's treatment, the thermocouple was removed, and the subject's leg was cleansed with 70% isopropyl alcohol. The thermocouple was disinfected in Cidex (Johnson & Johnson) overnight.

Statistical Analysis

Two 1 × 3 factor analyses of covariance were computed, the first to examine the treatment effects on temperature change (baseline to peak tissue temperature) and the second to examine treatment effects on time to peak tissue temperature. Baseline temperature and target tissue (groove) depth were used as covariates, the latter to determine if the height of the walls forming the groove had any effect on ultrasonic transmission. Each subject received all 3 treatments; thus, subjects were considered blocks in the analysis. A Duncan post hoc test was used to compare treatment means. These analyses were performed by using SAS PROC MIXED (version 8.1; Cary, NC).36

RESULTS

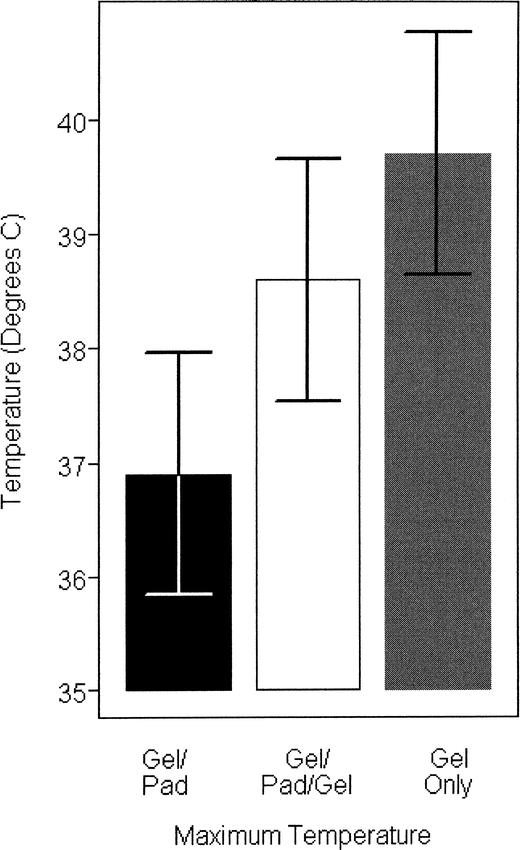

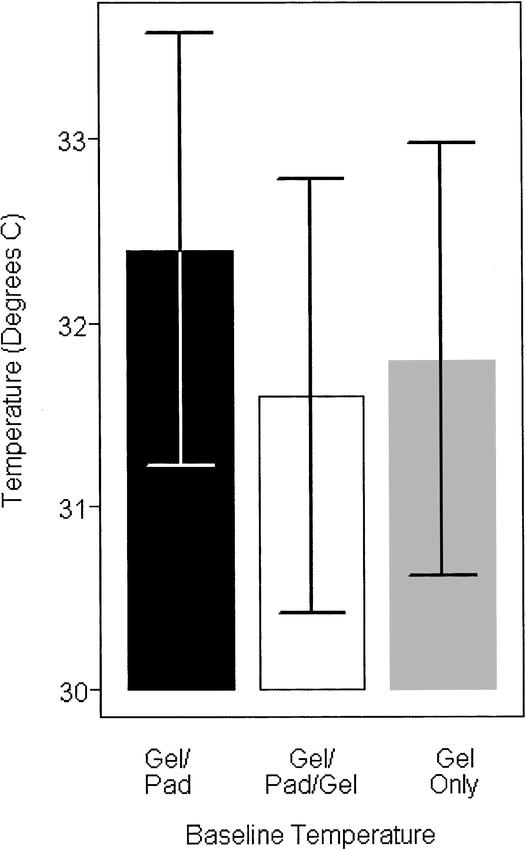

Intratissue temperature rise was significantly greater with the gel treatment (7.72°C ± 0.52°C) and the gel/pad/gel (6.68°C ± 0.52°C) than with the gel/pad (4.98°C ± 0.52°C; F2,16 = 13.39, P < .0001, Duncan < .006). No difference was noted between the gel and the gel/pad/gel treatments (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Maximum temperatures obtained with each treatment.

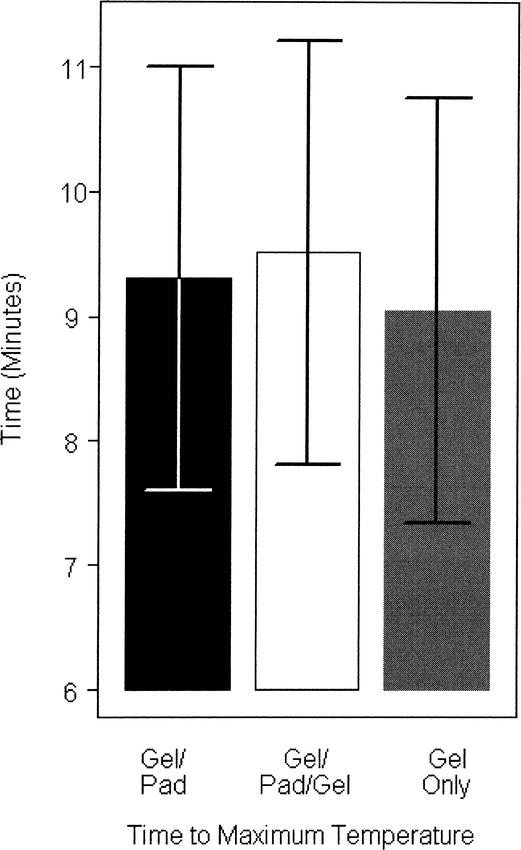

The time to peak temperature was not significantly different among the 3 intratissue treatments for the gel (9.05 minutes), the gel/pad (9.30 minutes), and the gel/pad/gel treatments (9.51 minutes) (F2,15 = .32, P = 0.73) (Figure 6). Also, the depth of the subject's groove (2.33 ± 0.91 cm, range = 0.5 to 3.5 cm) did not have a significant effect on the transmission of ultrasonic energy (F1,16 = 2.31, P = .15) on the basis of the heat measured from the tissues in the groove.

Figure 6.

Time to maximum temperature of each treatment.

Additionally, 8 of the 18 subjects complained of discomfort from the gel/pad treatment. These subjects reported no discomfort during the gel/pad/gel or gel-only treatments.

DISCUSSION

Our results indicate that when 3-MHz ultrasound at 1 W/cm2 is applied for 10 minutes, the gel/pad/gel interface is as effective at increasing intratissue temperature at 1-cm depth as ultrasound gel alone. The gel/pad interface, however, does not increase tissue temperature as effectively as the gel alone or the gel/pad/gel interface.

At first glance, the results of this study might appear to be a moot point, because all 3 treatments yielded temperature increases greater than 4°C, which is often considered vigorous heating (true if the baseline temperature is 36°C). It is important to note that the thermocouple was quite shallow; thus, we had low baseline temperatures (mean = 32°C) at the start (Figure 7). The slightly different baselines of treatments 1, 2, and 3 did not affect the outcome of the study because each subject was tested in a random order.

Figure 7.

Baseline temperatures.

With an average baseline temperature of 32°C, an increase of 7°C is possible. If the baseline temperature was 36°C to 37°C, then a 4°C increase would be optimal. From past studies, we have found that once the temperature reaches 39°C to 41°C, it stabilizes.2–4,33,37,38 We theorize that this is because of increased blood flow cooling the area. In a 1-MHz ultrasound study measuring temperature at 4 to 5 cm deep, the baseline temperature might be 36°C to 37°C; therefore, a 4°C increase is all that is typically possible before blood flow stabilizes the temperature of the tissue. The key here is which of the 3 treatments was least effective as an ultrasound couplant at producing the highest tissue-temperature rise (the gel/pad).

Our results differ from those reported previously that suggest no difference in the gel/pad or ultrasound gel as conducting media.32 We found that ultrasound delivered through a gel/pad interface produced lower tissue temperatures than did ultrasound delivered through a gel/pad/gel interface or ultrasound gel alone. In an in vitro study with pig muscle as the target tissue, the gel/pad/gel technique was 27% more effective in transmitting acoustic energy than was ultrasound gel (1-MHz continuous ultrasound at 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, and 2.5 W/cm2).24 A second in vitro study25 was then performed with 3.3-MHz ultrasound at intensities of 0.2, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, and 2 W/cm2. Klucinec et al25 compared transmissivity of ultrasound gel, the gel/pad/gel technique, the bladder technique, and immersion in tap water and degassed water. When ultrasound gel was considered baseline (100%), transmissivity of the gel/pad/ gel was 109%, bladder was 79% to 23%, tap water was 31%, and degassed water was 33%. The authors25 concluded that the gel/pad/gel technique was preferred with indirect ultrasound for optimal results.

In contrast, Merrick et al32 suggested that the gel pad alone was equivalent to ultrasound gel and provided no added benefits when used as a coupling agent. This conclusion was based on an in vivo (gastrocnemius) study with the gel pad (without any ultrasound gel) as a coupling agent using 1-MHz ultrasound for 7 minutes at an intensity of 1.5 W/cm2 over a surface area of twice the effective radiating area at a target-tissue depth of 3 cm.32 After reading the Merrick et al32 study, we concluded that it needed to be repeated with 3-MHz ultrasound. The gel pad was developed for treating soft tissues overlying bony prominences—tissues that typically fall within the treatment range of 3 MHz, not 1 MHz.31,33

Our study was designed with the depression between the lateral malleolus and the Achilles tendon as the target tissue. This necessitated using a 5-cm2 sound head so that it could lie flat on the target tissue's surface area and move freely and smoothly without being hindered by bony prominences. However, if a smaller bony prominence or joint were used, the sound head would need to be even smaller (perhaps 2 to 3 cm2). Otherwise, the sound head would not lie flat against the tissue, causing air to be entrapped between the sound head and the tissue.

Our results could have been partially caused by air entrapment. For instance, with the gel/pad technique, air may have been trapped between the pad and the skin of the subjects in the peroneal groove. This entrapped air results in inadequate coupling between the skin and the ultrasound transducer, which may have produced less uniform sound waves. When the pad was coated with gel on both sides during the gel/pad/ gel technique, no such air entrapment was apparent; thus, higher levels of heating took place. We reported earlier that 8 of the 18 subjects complained of discomfort during the gel/pad treatment, whereas no subject reported discomfort during the gel/pad/gel or gel-only treatments. We surmise that these air pockets in the gel/pad interface might result not only in nonuniform heating but also in possible hot spots on the ultrasound transducer faceplate or possibly the skin.28

Another reason our results differed from Klucinec et al25 and Merrick et al32 might be the types of tissues used in each study. Merrick et al32 used triceps surae muscle, and we used musculotendinous area in the peroneal groove; both are living, highly vascularized tissues. However, Klucinec et al25 used nonvascularized pig tissue. When highly vascularized tissue is heated, blood flow comes to the area to prevent excessive heating,39 which would not be the case with the tissue Klucinec et al25 studied.

Research Suggestions

The following recommendations for further research will extend our results and provide greater understanding of the use of the ultrasound gel pad:

Use an analog scale to measure the subjects' discomfort during the treatment and the rate of their perceived heating.

A different anatomic location should be studied, perhaps a smaller joint or bony prominence.

Different indirect techniques need to be compared, such as the ultrasound gel pad versus the underwater method and the bladder method.

Compare various settings, such as time, dose, and frequency.

CONCLUSIONS

When the gel pad has ultrasound gel applied to the top and the bottom surfaces, intratissue temperature increases are higher and faster during ultrasound application than when performed through a gel pad with ultrasound gel only on its topside. Because the gel pad was designed to be used over irregular surfaces and bony prominences, we suggest it should be coated on the bottom surface with ultrasound gel to decrease or eliminate entrapped air and to increase intratissue temperatures. A thin layer of gel should also be applied to the top of the pad to improve gliding of the ultrasound transducer faceplate.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bracciano AG. Physical Agent Modalities: Theory and Application for the Occupational Therapist. Thorofare, NJ: FA Davis; 2000. Therapeutic ultrasound and phonophoresis; pp. 63–80. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashton DF, Draper DO, Myrer JW. Temperature rise in human muscle during ultrasound treatments using Flex-All as a coupling agent. J Athl Train. 1998;33:136–140. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Draper DO, Schulthies S, Sovisto P, Hautala AM. Temperature changes in deep muscles of humans during ice and ultrasound therapies: an in vivo study. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1995;21:153–157. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1995.21.3.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Draper DO, Sunderland S, Kirkendall DT, Ricard M. A comparison of temperature rise in human calf muscles following applications of underwater and topical gel ultrasound. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1993;17:247–251. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1993.17.5.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kramer JF. Ultrasound: evaluation of its mechanical and thermal effects. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1984;65:223–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lehmann JF, DeLateur BJ, Silverman DR. Selective heating effects of ultrasound in human beings. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1966;47:331–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dyson M, Suckling J. Stimulation of tissue repair by ultrasound: a survey of the mechanisms involved. Physiotherapy. 1978;64:105–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hayes KW. The use of ultrasound to decrease pain and improve mobility. Crit Rev Phys Med Rehabil Med. 1992;3:271–287. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lehmann JF, DeLateur BJ. Therapeutic heat. In: Lehmann JF, editor. Therapeutic Heat and Cold. 4th ed. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1990. pp. 207–245. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klaiman MD, Shrader JS, Hicks JE, Danoff JV. Phonophoresis compared to ultrasound in the treatment of chronic musculoskeletal conditions [abstract] Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1995;27:S51. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199809000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dyson M. Mechanisms involved in therapeutic ultrasound. Physiotherapy. 1987;73:116–120. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lehmann JF, DeLateur BJ. Krusen's Handbook of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1982. pp. 304–322.pp. 332–342. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gersten JW. Effect of ultrasound on tendon extensibility. Am J Phys Med. 1955;34:362–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baker RJ, Bell GW. The effect of therapeutic modalities of blood flow in the human calf. J Orthop Sports Ther. 1991;13:23–27. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1991.13.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schrieber TU, Macher D, Mengs J, Callies R. Dose-dependent effects of therapeutic ultrasound to tissue blood flow detected by laser-doppler-spectroscopy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1996;77:937. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Balmaseda MT, Jr, Fatehi MT, Koozekanani SH, Lee AL. Ultrasound therapy: a comparative study of different coupling media. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1986;67:147–150. doi: 10.1016/0003-9993(86)90052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benson HAE, McElnay JC. Transmission of ultrasound energy through topical pharmaceutical products. Physiotherapy. 1988;74:587–589. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benson HAE, McElnay JC. Topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory products as ultrasound couplants: their potential in phonophoresis. Physiotherapy. 1994;80:74–76. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cameron MH, Monroe LG. Relative transmission of ultrasound by media customarily used for phonophoresis. Phys Ther. 1992;72:142–148. doi: 10.1093/ptj/72.2.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Docker MF, Foulkes DJ, Patrick MK. Ultrasound couplants for physiotherapy. Physiotherapy. 1982;68:124–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Forrest G, Rosen K. Ultrasound: effectiveness of treatments given under water. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1989;70:28–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Forrest G, Rosen K. Ultrasound treatments in degassed water. J Sport Rehabil. 1992;1:284–289. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Griffin JE. Transmissiveness of ultrasound through tap water, glycerin, and mineral oil. Phys Ther. 1980;60:1010–1016. doi: 10.1093/ptj/60.8.1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klucinec B. The effectiveness of the Aquaflex gel pad in the transmission of acoustic energy. J Athl Train. 1996;31:313–317. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klucinec B, Scheilder M, Denegar C, Domholdt E, Burgess S. Transmissivity of coupling agents used to deliver ultrasound through indirect methods. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2000;30:263–269. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2000.30.5.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pose A, Lee Foo D. Evaluation of ultrasound couplants. Med Ultrasound. 1979;3:77–78. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reid DC, Cummings GE. Efficiency of ultrasound coupling agents. Physiotherapy. 1977;63:255–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prentice WE, Draper DO. Therapeutic ultrasound. In: Prentice WE, editor. Therapeutic Modalities for Allied Health Professionals. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1998. pp. 285–288. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Denegar CR. Therapeutic Modalities for Athletic Injuries. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 2000. pp. 161–164. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Starkey C. Therapeutic Modalities. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: FA Davis; 1999. pp. 283–291. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nault P. Applying ultrasound to irregular surfaces. PT Magazine. 1993;1:94. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Merrick MA, Mihalyov MR, Roethemeier JL, Cordova ML, Ingersoll CD. A comparison of intramuscular temperatures during ultrasound treatments with coupling gel or gel pads. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2002;32:216–220. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2002.32.5.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Draper DO, Castel JC, Castel D. Rate of temperature increase in human muscle during 1 MHz and 3 MHz continuous ultrasound. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1995;22:142–150. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1995.22.4.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Isothermex-Electronic Thermometer: Instruction Manual. Columbus, OH: Columbus Instruments; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buchtala V. The present state of ultrasonic therapy. Br J Phys Med. 1952;15:3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Littell RC, Milliken GA, Stroup WW, Wolfinger RD. SAS System for Mixed Models. Version 8.1. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 1996. p. 633. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rose S, Draper DO, Schulthies SS, Durrant E. The stretching window part two: rate of thermal decay in deep muscle following 1-MHz ultrasound. J Athl Train. 1996;31:139–143. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Draper DO, Ricard MD. Rate of temperature decay in human muscle following 3MHz ultrasound: the stretching window revealed. J Athl Train. 1995;30:304–307. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chan AK, Myrer JW, Measom G, Draper DO. Temperature changes in human patellar tendon in response to therapeutic ultrasound. J Athl Train. 1998;33:130–135. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]