Abstract

Using breast cancer risk assessment tools and going through the process of assessing breast cancer risk can answer many women's questions about what puts them at relatively higher or lower risk. This effectively engages both the clinician and the patient in a discussion about breast cancer, the chances of getting it, and the family's involvement — making the process as important as the actual tools.

Examples of selected case histories demonstrate risk assessment using available tools such as the Gail-NCI and the Claus models. For some women, such as those considering tamoxifen or prophylactic surgeries, it may be desirable to prescreen for the inheritance of hereditary mutations and to follow with genetic testing, if indicated. Testing for mutations of breast cancer susceptibility genes or for their diminished expression adds to our ability to assess breast cancer risk at an individual level.

The literature contains general interventions that are widely accepted to reduce the severity and the burden of breast cancer, and these are brought together here. The risk assessment process is an important part of a risk reduction program and can help motivate women to engage in prevention activities. This paper uses 2 hypothetical but fact-based and typical case histories to discuss the utility of risk assessment tools for informing women about their options.

Using breast cancer risk assessment tools can answer many womeńs questions about risk levels and effectively engages a clinician and patient in crucial discussions about cancer and individual risk.

Introduction

Clinicians can incorporate breast cancer risk assessment into their routine screening and health maintenance appointments.[1] This effectively engages both the clinician and the patient in a discussion about breast cancer, the chances of getting it, and the family's involvement. The process is as important as the actual tools, but women and their clinicians are increasingly encouraged to use risk assessment estimates based on statistical models.[2] The Gail-NCI model[3] is the most thoroughly tested; the Gail-NCI and Claus[4] models are the most often used. Risk assessment is a serious undertaking,[5] but the availability of these 2 tools permits rapid risk calculation during routine clinical encounters.

The tools are not perfect, but they can help motivate women to engage in prevention activities. The literature contains general interventions that are widely accepted to reduce the severity and the burden of breast cancer, and these are compiled here. This paper first presents case history-based examples of how a practicing clinician could use risk assessment tools and then discusses interventions for managing the risk.

Methods

Breast cancer patient case histories were selected and reviewed retrospectively from previously published information. Information from the case histories was used to assess breast cancer risk either from computer programs or by consulting tables. The Gail-NCI model as a computer program (v.2) with documentation was obtained from NCI. Claus risk was determined based on tables.[4,6] Data used to calculate the odds of having a BRCA gene mutation came from the Myriad Genetics Web site (http://www.myriad.com). CancerGene, a computer program, was used to calculate these probabilities using the computer program BRCAPRO. CancerGene was obtained from Dr. David Euhus after signing a license agreement at http://www3.utsouthwestern.edu/cancergene/. BRCAPRO measures BRCA gene mutation probability by treating family history more thoroughly than the Claus or Gail-NCI models, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Variables Used in Different Models for Breast Cancer Risk Prediction

| Gail-NCI | Claus | BRCAPRO | Feuer and Wun | |

| Reference | 3 | 4 | 7 | 10 |

| Personal information | ||||

| Age | + | + | + | + |

| Body mass index | ||||

| Hormonal factors | ||||

| Age at menarche | + | |||

| Age at first live birth | + | |||

| Age at menopause | + | |||

| Personal history | ||||

| Breast biopsy | + | |||

| Atypical hyperplasia | + | |||

| LCIS | ||||

| Family history | ||||

| Number of first-degree relatives affected | + | + | + | |

| Number of second-degree relatives affected | + | + | ||

| Age of onset of breast cancer in first- and second-degree relatives | + | + | ||

| Bilateral breast cancer | + | |||

| Ovarian cancer | + | |||

| Male breast cancer | + | |||

| Race/ethnicity | + | |||

| Ashkenazi Jewish | + | |||

| Population-based risk factors | ||||

| Breast cancer incidence in the population | + | |||

| Breast cancer mortality | + | |||

Table 1 also summarizes the risk factors considered by other risk prediction tools.[3,4,6-10] The Gail-NCI and Claus models were used here because physicians would be most likely to encounter them. They are widely available, easily and widely used, current, and applicable to the cases considered here. However, other models exist. Tyrer and colleagues[8] and Amir and colleagues[9] incorporate other known risk factors in a new model. Feuer and Wun[10] give age-conditional probabilities of developing breast cancer and dying from the disease. Incidence data for these probabilities originate from the NCI Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program. This is a collection of population-based US cancer registries that collect and submit cancer incidence and mortality data to the NCI.

There are also a variety of other models that are not included in Table 1. Models from Anderson and Badzioch[11] predict the risk of breast cancer in the presence of a family history of prostate, endometrial, or ovarian cancer. Models by Couch and colleagues,[12] Shattuck-Eidens and colleagues,[13] and Frank and colleagues[14] were earlier calculation methods for risks due to BRCA gene mutations.

Case Histories

Case History 1: Lucy, A 34-Year-Old, Severely Stressed Woman

Lucy, a 34-year-old woman, presented with significant stress and sleep deprivation. She worked part time and cared for her 3 young children, aged 10, 8, and 5 years, with little or no spousal support with child care. A detailed history revealed that a major concern was the recent diagnosis of breast cancer in her mother at age 57 years. Receiving information about breast cancer allowed her to help her mother more realistically. However, the daughter feared that she herself might develop the disease.[15]

Case History 2: Jane, A Woman With a Strong Family History of Breast Cancer

Jane is a 36-year-old white, non-Jewish woman concerned about her risk of developing breast cancer. She has had 5 previous mammograms and receives annual clinical breast exams. She performs weekly breast self-examination. Her mother had unilateral breast cancer at age 49 years, underwent chemotherapy, and is still alive. Her sister was recently diagnosed with breast cancer at age 43 years, had a lumpectomy, and is currently receiving chemotherapy. Jane has 2 daughters; the elder is age 14 years. Jane has recently lost 30 pounds but is still overweight. She has had problems with her menstrual cycle and takes oral contraceptives. She recently became a vegetarian and has stopped drinking alcoholic beverages.[16]

Results

Case 1

Applying the Gail-NCI model. Like 34-year-old Lucy, 1 in 3 women with breast cancer has a mother, sister, or daughter with the disease. The Gail-NCI computer program requests input about the 6 risk factors listed in Table 1, but the program still works if some of this information is missing. Results are given in comparison to a woman of average risk rather than in comparison to a woman with no risk factors. Results can be expressed as 5-year risk, lifetime risk, and risk at any age. Because Gail-NCI includes simple measures of estrogen exposure, the tool is used to identify potential candidates for tamoxifen therapy.

Thirty-four-year-old Lucy had no breast biopsies, and menarche occurred after age 12 years. The Gail-NCI results have predictive value only for women over the age of 35 years, so to apply the tool here, it is necessary to assume that a woman's risk until she is 35 is 0%. The Gail-NCI model (Figure 1) calculates Lucy's cumulative risk of breast cancer by age 39 years as 0.4% (twice the average cumulative risk of 0.2% at age 39 years). By age 79 years, her cumulative lifetime risk is 17.2% vs 12.6% for a woman at average risk, so her mother's cancer raises her lifetime risk by about 5% (Figure 1). Lucy's worry is largely affected by her judgment of the probability that she will get the disease. Her perception of this probability may be much higher than the probability perceived by experts. Thus, a realistic understanding of her breast cancer risk may reduce her level of worry and stress. Reassurance can be an important intervention.[17] Lucy may also reduce worry and stress by understanding her risk factors and taking available steps to lower them.

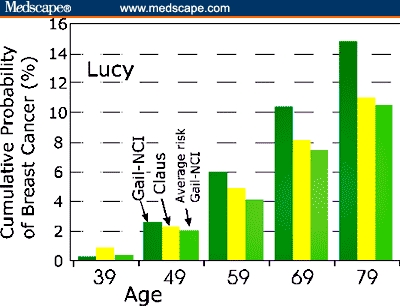

Figure 1.

Simultaneous Gail-NCI and Claus risk assessment for Lucy (34 years old with 1 first-degree relative with breast cancer). Risk is graphed as calculated by the 2 models for Lucy at 10-year increments. The last vertical bar at each age is the Gail-NCI calculation for a woman at “average” risk

Applying the Claus model: familial breast cancer. Gail-NCI is currently the only independently validated model for breast cancer risk assessment but has not been validated in African-American women, with their higher mortality rates.[18] The model still seems well-suited for general screening,[19] corresponding to the final risk assignment even in 87% of cases thought to confound it: family history of breast cancer in second degree relatives; breast cancer in the family before the age of 50 years; bilateral breast cancer; family history of ovarian cancer; or personal history of lobular neoplasia.[19] Nonetheless, the fact that Gail-NCI does not consider these risk factors is a limitation of the model.

The Claus model[4] is still useful to assess risk for familial breast cancer — the kind of breast cancer that seems to run in families but is not associated with a known hereditary breast cancer susceptibility gene. Unlike the Gail-NCI model, the Claus model requires the age at breast cancer diagnosis of first- or second-degree relatives as an input (Table 1). McTiernan and colleagues[20] found that the Claus model was moderately and positively correlated (r = 0.55) with the Gail-NCI model. Lucy's risk of breast cancer vs age (Case 1) was calculated based on both models. Figure 1 shows that Lucy's Gail-NCI risk is greater than her Claus risk except perhaps at the age 39 point. Lucy's calculated Gail-NCI values differ significantly from her Claus risk. In fact, the “average risk” from Gail-NCI agrees better with Lucy's Claus risk than with her Gail-NCI risk (Figure 1).

Claus and colleagues[4] confirmed a 3-fold increase in breast cancer risk in women whose mothers or sisters had breast cancer. Early-onset breast cancer was strongly associated with a family history, and the data conform to an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance. This adds emphasis to asking women about family history on both maternal and paternal sides.[21,22] The Claus model considers these data for breast cancer (Table 1).

The lifetime risk for familial breast cancer may approach about half the risk of those susceptible to a known inherited breast cancer susceptibility gene. Familial breast cancer causes perhaps 15% to 20% of all breast cancer cases.[23] There is always the chance that some cancer in the family is due to the chance aggregation of sporadic or spontaneous breast cancers. These are breast cancers with poorly understood causes, so any one case in a breast cancer family may still be the sporadic form.

Case 2

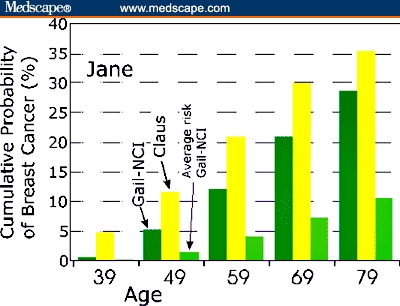

Jane has a stronger family history of breast cancer than Lucy but only through first-degree relatives, considered by both the Gail-NCI method and the Claus methods. Jane's cumulative risk of breast cancer vs her age is shown in Figure 2, plotted based on both models. The data show that her Claus risk is elevated more than 2-fold over her Gail-NCI risk at age 49 years. By age 79 years, Jane's Claus risk is a substantial 35.4% (Figure 2), but the Gail-NCI risk has risen to about 28%, nearly equaling her Claus risk. Information from the paternal side of her family also needs to be considered but is missing. Even without paternal data, Jane's Claus risk is so substantial that she may wish to consider genetic testing for hereditary breast cancer — the inheritance of a mutation in a breast cancer susceptibility gene.

Figure 2.

Simultaneous Gail-NCI and Claus risk assessment for Jane (36 years old with 2 first-degree relatives with breast cancer). Risk is plotted after calculation according to the 2 models for Jane at 10-year increments. The last vertical bar at each age is the Gail-NCI calculation for a woman at “average” risk

Hereditary breast cancer screening methods: prescreening for hereditary mutations. Neither the Claus nor the Gail-NCI method is appropriate to use if there is a BRCA gene mutation in Jane's family. An inherited mutation in BRCA cancer susceptibility genes would put Jane's lifetime risk at 50% to 85%. These mutations are rare and only involved in 5% to 10% of all breast cancers, but her mother's and her sister's cancers at ages < 50 years raise this suspicion. Other items in the family history that would raise this suspicion include many cases of cancer, breast and ovarian cancers, male breast cancer, medullary breast cancer, or a family member under 50 with breast cancer plus Ashkenazi or Icelandic ancestry.[6,24] Table 1 shows that the Gail-NCI model and the Claus model do not consider most of these risk factors, so they would seriously underpredict Jane's breast cancer risk if she were a mutation carrier.

To help Jane decide whether to undergo genetic testing, the odds can be determined that she has inherited a pathogenic BRCA gene mutation. It is cost-effective to do this. Based on European data, direct DNA sequencing currently costs about $12,000 per mutation detected,[25] but other strategies that include prescreening techniques save much of this cost. For Jane, the Myriad tables estimate 32.6% as the prevalence of deleterious mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes in individuals who are not Ashkenazi Jewish and with more than one relative with breast cancer diagnosed at an age < 50 years. This information is based on 349 observations from 1072 tests.

BRCA gene mutation probability was also measured with BRCAPRO, a tool that works best for high-risk families that contain many women.[26] According to BRCAPRO, Jane's odds of having a pathogenic BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutation are 5.3%.

If genetic counseling and genetic testing are desired, http://cancer.gov/search/genetics_services/ contains a searchable list of specialized genetic testing centers, or this information can be obtained by calling 1-800-4-CANCER.

Genetic testing benefits and risks. If positive, Jane may opt for undergoing frequent surveillance, tamoxifen therapy, and/or prophylactic surgery in addition to general steps aimed at reducing breast cancer probability. She may derive a benefit from ending uncertainty; she may also wish to share her test results with others in the family for emotional support, for advice, and because sharing her results will allow predictive testing of healthy individuals. However, the option to learn genetic status may not always be a benefit, resulting in greater levels of anger, worry, and distress. In contrast, a negative genetic test result may be valuable by itself. Although it does not guarantee freedom from cancer, a negative test can release Jane from coping with a defined high risk, from intensive surveillance, and from guilt and worry about transmission to her children.

Discussion

Insights From the Risk Modeling Experiments

The 2 modeling exercises show that the risk values obtained using 2 different assessment tools differ significantly, providing a range of risk values. If women with a family history of breast cancer are being counseled regarding decisions on augmented surveillance, genetic testing, tamoxifen use, or other preventive measures, presenting both Claus and Gail estimates may be the best option.[20]

The Gail-NCI model predicts risk based on data obtained mainly from sporadic cancers, while the Claus model is based largely on familial breast cancer data. For Lucy and Jane, Claus risk is proportionately greater relative to Gail-NCI risk at the younger ages plotted in both Figures 1 and 2. For Lucy, the Gail-NCI cumulative risk becomes larger than Claus cumulative risk beginning at the age 49 point (Figure 1). For Jane, Claus risk is more than double the Gail-NCI risk at the age 49 point. With increasing age, the Gail-NCI risk begins to catch up (Figure 2). This is consistent with Claus's premise that the effect of genotype on the risk of breast cancer is an inverse function of a woman's age. Moreover, an early age of onset is the strongest indicator of a possible genetic subtype of breast cancer.[27]

Implications of Risk Assessment Results: Measures to Reduce Breast Cancer Risk

Simply using breast cancer risk assessment tools and going through the process of assessing breast cancer risk can answer many women's questions about what puts them at relatively higher or lower risk. Table 2 contains a list of generally accepted risk factors and the magnitude of their effect. Not all of them can be modified, but discussing these and other potential risk factors can provide motivation to engage in prevention activities. The fact that there are management options even for mutation carriers supports physician recommendation of breast cancer genetic testing, if appropriate. Table 3 contains a summary of suggested risk stratification models, proposed screening techniques, and suggested risk reduction measures for different patients.

Table 2.

Established Breast Cancer Risk Factors

| Risk Factor | Magnitude of Risk Factor | Notes | Reference |

| Age >/= 50 vs < 50 | 6.5 | The strongest risk factor. Graphs in Figures 1 & 2 show risk increases with age. | 3, 70 |

| Number of first-degree relatives with breast cancer | 1.4–13.6 | Family history is the second strongest risk factor after age. | 3, 4, 71 |

| Age at menarche < 12 vs >/= 14 | 1.2–1.5 | Menarche at ages 12–13 has a smaller effect on breast cancer risk and is not listed. | 3 |

| Age at menopause (>/= 55 vs < 55) | 1.5–2.0 | Years from menarche measures long-term estrogen exposure. | 3, 72 |

| Age at first live birth > 30 vs < 20 | 1.3–2.2 | First live birth at ages 20–30 has a smaller effect and is not listed. | 3, 72 |

| Previous breast biopsy (whether positive or negative) | 1.5–1.8 | 3 | |

| Lobular carcinoma in situ | 5.4–11 X general population; 18% after 20 years | A risk factor and nonobligate precursor for invasive or intraductal carcinoma. | 73,74 |

| At least 1 biopsy with atypical hyperplasia | 4.0–4.4 | 3 | |

| Hormone replacement therapy | 1.5 | 48 | |

| Radiation to chest area | Up to 20-fold increase at age 32 | Data from A-bomb survivors. Radiation for Hodgkin's also increases risk. | 45, 47, 75 |

| High mammographic breast density | 1.8- to 6-fold | May be hereditary, a Claus risk assessment may be worthwhile. | 76 |

| Alcohol use 15 g/day | 2.5-fold | 38 | |

| Alcohol 1.5 drinks per day | 1.3 | 38 | |

| Postmenopausal body mass index (BMI) | 1.19 for each 5 kg/m2 rise in BMI | Perhaps attributed to associated increase in estrogen, especially bioavailable estradiol | 77 |

Table 3.

Risk Assessment, Surveillance, and Reduction

| Version of Breast Cancer | Initial Risk Assessment | Follow-up Assessment | Surveillance | Proposed Risk Reduction |

| Hereditary | Ask about family history of breast/ovarian cancer in both maternal and paternal sides. Use Claus assessment if multiple first- or second-degree relatives affected and age of onset known. Prescreen for BRCA gene mutations based on family history. | Myriad genetics tables, then counseling and genetic testing for BRCA1/2 mutations | Minimum recommendations are a physical exam every 6 months between ages 25–35 with monthly BSE at age 20. Screen for ovarian cancer. Mammograms may be ineffective or unreliable in some carriers. Deficit in repairing radiation damage may also complicate mammograms. If mammograms are inadequate, consider adding to standard surveillance MRI with serial comparison to baseline for changes. Consider ductoscopy and ductal lavage to decide on tamoxifen if BRCA2 carrier or on prophylactic surgery. | If BRCA2 mutation, offer tamoxifen. If BRCA1 or 2, avoid radiation and oral contraceptives. General methods of risk reduction in text. Counseling. Consider mastectomy and salpingo-oophorectomy |

| Sporadic | Ask about family history of breast/ovarian cancer in both maternal and paternal sides. Use Gail-NCI if first- or second-degree relative not affected. Either Claus or Gail-NCI applies if only first-degree relatives, but answers will differ. | Risk < 5%: mammography and clinical breast exam. Risk > 5%: initial mammography and clinical breast exam. |

Mammogram every 1–2 years, with or without clinical breast exam. Mammogram every 1–2 years, with or without clinical breast exam. Consider serial MRI for high risk. |

General methods of risk reduction in text. Offer tamoxifen. Offer ductoscopy, ductal lavage as decision aid. General methods of risk reduction in text. |

| Familial | Ask about family history of breast/ovarian cancer in both maternal and paternal sides. Use Claus method | Myriad genetics tables, then counseling and other related genetic testing as available. | MRI serial comparison to baseline for changes. (High breast density raises risk 1.8- to 6-fold and may make mammograms unreadable.) | Offer tamoxifen. Use ductoscopy, ductal lavage as decision aid. Avoid radiation and oral contraceptives. General methods of risk reduction in text. |

Risk Reduction Strategies

The literature provides a wealth of information about how lifestyle, dietary, and/or medical intervention measures may affect the probability of a woman developing breast cancer. Bringing this information together here makes it easier for the physician to suggest ways to reduce breast cancer risk to women proactively, without waiting to be asked. There are general practices that all women may wish to use in an effort to prevent 3 types of breast cancer — sporadic, familial, and hereditary. In order for this to be successful, women must be convinced of 3 separate judgments: (1) the strategies actually reduce risk, (2) it is possible to do them, and (3) the costs are worth it.[28]

Oral contraceptives. Observational studies conflict about an association between oral contraceptives and breast cancer in the general population and in women with a family history.[29,30] However, oral contraceptives are contraindicated in the presence of malignancy because they contain estrogens and progestins that stimulate tumors.[31]

Abundant evidence in the literature shows that women who are at high risk for hereditary or familial cancer may already have premalignant or undiscovered malignant cells.[32] Even those with one first-degree relative with the disease have a 35% chance of having either marked or atypical hyperplasia. A recent observational study verified that oral contraceptives raised the risk from breast cancer in BRCA1 mutation carriers who used them.[33] Thus, if there is a strong family history of breast cancer, women should use caution with oral contraceptives and should receive additional information to allow informed consent. They can be offered augmented screening for occult malignant or premalignant cells (Table 3). In some of these women, MRI screening regularly uncovers tumors missed by more routine methods.[34] The increased risk caused by oral contraceptives in women with a family history of breast cancer can be eliminated by using nonhormonal methods of contraception, although these may come with the real trade-off of lower efficacy for pregnancy prevention.

Exercise. Four or more hours per week of exercise results in about a 40% reduction in breast cancer risk.[35] Compared with less active women, women who had regular strenuous physical activity at age 35 years had a 14% decreased risk of breast cancer over an average of 4.7 years of follow-up. Women aged 18 and 50 years also experienced a reduction in breast cancer risk.[36] Even in BRCA mutation carriers, physical exercise in adolescence was associated with significantly delayed breast cancer onset.[22]

Weight control. Women who gain > 50 pounds after pregnancy and do not lose it increase their risk by 3 times. Each 2.2 pounds retained after pregnancy raises risk by 4%.[37,38] Healthy weight at menarche and at age 21 years significantly delayed breast cancer onset in BRCA mutation carriers.[22] Other effects of diet are not widely accepted.

Limit alcohol intake. Consumption of 15 g/day of alcohol raised breast cancer risk by 2.5-fold (Table 2). Women who average 1.5 drinks per day have a 30% increase in risk.[39]

Parity. In comparison with not giving birth, having a child reduces both breast and ovarian cancer risk by 2- to 3-fold. Breast protective effects may arise from terminal differentiation that occurs in breast tissue, from the temporary break from ovulation, from greater transcription of BRCA or other genes, or from elimination of mutagens in breast milk.[40] For Danish women in a large study, there was a risk reduction after any birth occurring before the age of 30 years.[41] Parity protected even women with BRCA founder mutations from ovarian cancer,[42,43] but it is now uncertain whether parity also protects mutation carriers from breast cancer.

Breastfeeding. The relative risk of breast cancer decreased by 4.3% for every 12 months of breastfeeding in addition to a decrease of 7% for each birth.[44]

Radiation. There is a clear link between radiation exposure and breast cancer. Radiation is dangerous for young women, especially if they have not completed breast development (Table 2). Each breast lobule originates from a single cell. If one of these cells has misrepaired or unrepaired radiation damage, then the cell division that occurs during puberty could propagate the damage and increase the odds that a tumor will develop. BRCA mutation carriers or other women who have an impaired DNA damage response would be especially susceptible. Exposure to radiation (particularly to the chest area) for all women should be kept to a minimum, and modern low-dose equipment should be used when x-rays or other radiation is necessary. Uninvolved body parts should be shielded.[45-47]

Hormone replacement therapy. According to the WHI study,[48] if 10,000 women took menopause hormone therapy drugs (Prempro) for a year and 10,000 did not, women in the first group would have 8 more cases of invasive breast cancer, 7 more heart attacks, 8 more strokes, and 18 more instances of blood clots. But vasomotor symptoms would improve and there would be fewer fractures. Thus, a woman and her doctor may decide that the benefits of menopause hormone treatment outweigh the risks, but then the treatment should be as brief as possible with as low a dose as possible.[48,49] Many women on menopause hormone therapy have decided to stay on it. Even these women may benefit from increasing their level of exercise.[36]

Medical Interventions for Risk Management

Reassurance, surveillance, and referral. A recent set of proposed guidelines for the general practitioner was composed of 4 options that follow breast cancer risk assessment: reassuring, starting surveillance, contacting a family cancer clinic, and referring to a family cancer clinic.[17] Based on risk assessment, women can be selected for more than routine breast cancer screening according to predicted risk. A younger age of breast cancer diagnosis in a family justifies screening from an earlier age.[50]

Tamoxifen. Although debate continues, Jane may benefit from tamoxifen for primary prevention because she has 2 or more first-degree relatives with breast cancer.[51] Other indications that tamoxifen may be particularly beneficial are atypical hyperplasia (86% risk reduction), a 5-year Gail risk > 5%, or lobular carcinoma-in-situ.[51] The benefits may be greater if tamoxifen is initiated before age 50 years.[51] Women who have dense breasts and women with a BRCA2 mutation that may produce an estrogen receptor-positive tumor should also consider tamoxifen. If genetic testing reveals that Jane has a BRCA1 gene mutation, then tamoxifen will probably not be protective.

Tamoxifen for primary prevention reduced the risk of invasive breast cancer by 49%. But only estrogen receptor-positive tumors were prevented. In estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer, adjuvant tamoxifen therapy for 5 years after initial surgery reduced recurrence by 47%. Mortality at 10 years fell by 26%,[51,52] but the overall effect on survival and quality of life has yet to be determined.

When tamoxifen is used as adjuvant therapy to treat breast cancer, its benefits on disease-free survival and time to recurrence probably outweigh the risks. However, of the women who are offered tamoxifen, only about 20% agree to take it because of the drug's side effects. Several trials report a 2- to 3-fold increase in both uterine cancer and dangerous blood clots (deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism). No risk assessment model incorporates risks of adverse events that come from taking tamoxifen.[53] Chemoprevention that is safe and as effective as prophylactic surgeries remains a hope for the future.

Prophylactic surgeries: mastectomy. Women who undergo prophylactic bilateral mastectomy may have an exaggerated perception of their breast cancer risk before surgery. Formal genetic counseling and genetic testing may give women a more realistic perception of their breast cancer risk.[54]

Specific indications for prophylactic mastectomy include a positive genetic test result, a strong family or personal history of breast cancer, multiple previous breast biopsies, unreliable results on physical examination because of nodular breasts, findings of dense breast tissue on mammography, mastodynia, and cancer phobia. Surgeons have long recognized that breast tissue is widely distributed over the entire anterolateral portion of the chest wall and axilla and that no mastectomy removes all mammary tissue. There have been case reports of breast cancer in residual tissue, but prophylactic mastectomy very substantially reduces the incidence of breast cancer, even for women who carry a BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutation.[55,56]

Protection from this prophylactic strategy persisted throughout a continuing follow-up period with a median of 14 years. Most cancers occurring after prophylactic mastectomy were confined to the chest wall and were not associated with distant metastases.[55,56]

Prophylactic surgeries: prophylactic oophorectomy. Bilateral prophylactic oophorectomy markedly reduced the risk of both cancer of the coelomic epithelium and of the breast associated with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. The procedure is generally better accepted than mastectomy.[57] With the mean age of ovarian cancer diagnosis at 50.8 years, prophylactic oophorectomy is generally performed in carriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations as soon as feasible after childbearing is completed.[58-60] The current lack of effective methods of surveillance also argues in favor of prophylactic surgeries, but MRI and promising genomic and proteomic-based procedures may provide rapid accurate surveillance in the near future.[61]

Ductoscopy and breast ductal lavage for individual risk assessment. Ductoscopy and breast ductal lavage are minimally invasive methods of individual risk assessment based on cytologic evaluation of cells obtained from ductal fluid. Breast ductal lavage can be offered to help women make a more informed decision about tamoxifen or surgeries. The technique is based on the fact that a major duct and its tributaries drain each of the 15–20 lobes that make up the breast. About 95% of breast cancers involve this ductal system. Breast ductal lavage is successful in about 80% of women and is no more uncomfortable than a mammogram. However, it only provides cells from one of the 15–20 major ducts. Recent data have questioned the sensitivity of the procedure, and further studies are needed to define its role in risk assessment.

Limitations of Risk Assessment

Risk assessment and subsequent interventions can reduce the severity and the burden of breast cancer, both individually and in the population. This allows a new emphasis on preventing and delaying onset of the disease.[62] However, if not managed well, a breast cancer risk assessment could cause undue stress and concern. For example, a risk assessment that leads to finding a pathogenic BRCA gene mutation can make some women feel doomed and powerless. Probands may experience distress in communicating their test results to family members.[63]

Risk stratification can lead to more informed decisions, but a favorable risk assessment result still does not guarantee that women will not develop the disease. Cancer can still develop in the absence of any identifiable risk factors. Even when women seem to be at relatively low risk, bad outcomes can still occur. This points out an important boundary for how risk assessment models should be used. Current models are a first step in breast cancer risk management. They provide general answers in terms of probabilities or a range of probabilities and are not intended to give yes or no answers about one woman's individual risk.

Recent advances promise clearer individualized risk assessment. To go beyond statistical probabilities to a more individualized risk assessment will require a broader range of genetic testing. Mutations in BRCA genes are currently associated with hereditary breast cancers, but a mutation in a BRCA gene is not an adequate model for breast cancer. It is reasonable to expect that future evidence will implicate sets of additional genes. Mutations in other genes are also known to be associated with breast cancer cases (eg, CHEK2, p53, PTEN, etc),[64-66] while still other genes have suspected, plausible, or postulated associations. Some may require significant or unusual environmental interactions.[64]

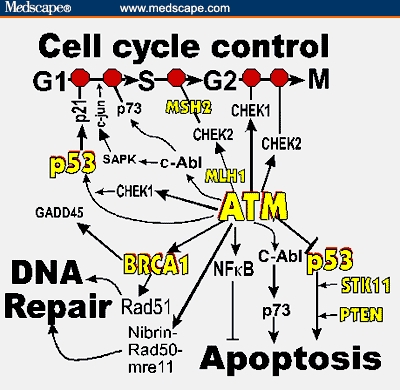

Mutations in the cell-cycle checkpoint kinase gene CHEK2 account for about 5% of familial breast cancer. Hereditary deficits in the p53 gene only account for < 1% of hereditary cancers, but p53 mutations are found in half of all cancers. Female relatives of ATM homozygotes are at increased risk for breast cancer. There are already commercial genetic or functional tests for some of these candidate genes (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Outline of DNA damage response showing opportunities for more extensive testing of genetic predispositions to breast cancer. The central role of ATM is shown as well as its connection to BRCA1. Note that p53 appears in 2 places in the outline. The red octagons (“stop signs”) represent checkpoints that slow or stop the cell cycle in the event of DNA damage. The short perpendicular bars above apoptosis and p53 (right) represent inhibition. Proteins for which there are already commercial tests are indicated in yellow. Based on BioCarta Pathways from the Cancer Genome Anatomy Projecthttp://cgap.nci.nih.gov/Pathways/BioCarta_Pathways.

The proteins listed as products of candidate genes function within a vast, redundant network of interacting DNA damage response proteins that also includes BRCA proteins.[65-68] Figure 3 shows rudiments of this damage response network. Because our knowledge is changing rapidly with new information, Figure 3 presents only a broad outline, but even this may require revision. It is clear now that the vast network of pathways represented by the figure accomplishes 3 broad functions when faced with DNA damage: (1) stop the cell cycle to allow for DNA repair, (2) repair DNA damage, and (3) promote programmed cell death in the event that DNA damage is beyond repair. Disabling this network leads to genomic instability, commonly found in breast cancers. DNA repair deficits may identify high-risk members in breast cancer families.[69]

Hereditary BRCA-related cancer has helped us to understand the DNA damage response and probably provided insights into sporadic and familial cancer as well. Although BRCA genes only occasionally mutate in sporadic cancers, their expression is often reduced. Testing for mutations of known or future breast cancer susceptibility genes or for their diminished expression will add more individualized risk prediction to information provided by breast cancer risk assessment models.

Conclusions

The physician can now suggest evidence-based ways to reduce breast cancer risk to all women. A breast cancer risk assessment may arguably help motivate a woman to take steps to reduce risk. Thus, breast cancer risk assessment can reduce the severity and the burden of breast cancer both to an individual and to an entire population.

Risk assessment tools are meant for quick stratification of women into risk groups. Testing for mutations of known or future breast cancer susceptibility genes or for their diminished expression will add to our ability to assess breast cancer risk at an individual level.

As we learn more about the role of genes in breast and ovarian cancer, widespread genetic screening may well become a cost-effective method of risk analysis, reducing the impact of breast, ovarian, and other cancers.

LCIS, lobular carcinoma in situ

BSE, breast self-examination; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging

References

- 1.Vogel VG. Management of the high-risk patient. Surg Clin North Am. 2003;83:733–751. doi: 10.1016/S0039-6109(03)00030-6. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rubenstein W, O'Neill S, Peters J, Rittmeyer L, Stadler M. Oncology. 2002;16:1082–1094. discussion 1097–1099. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gail MH, Costantino J, Bryant J, et al. Weighing the risks and benefits of tamoxifen treatment for preventing breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:1829–1846. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.21.1829. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Claus E, Risch N, Thompson W. Autosomal dominant inheritance of early-onset breast cancer. Implications for risk prediction. Cancer. 1994;73:643–651. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940201)73:3<643::aid-cncr2820730323>3.0.co;2-5. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sakorafas GH, Krespis E, Pavlakis G. Risk estimation for breast cancer development; a clinical perspective. Surg Oncol. 2002;10:183–192. doi: 10.1016/s0960-7404(02)00016-6. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eisen A, Armstrong K, Weber B. Assessing the risk of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:565–570. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200002243420807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berry DA, Iversen ES, Jr, Gudbjartsson DF, et al. BRCAPRO validation, sensitivity of genetic testing of BRCA1/BRCA2, and prevalence of other breast cancer susceptibility genes. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2701–2712. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.05.121. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tyrer JP, Duffy SW, Cuzick J. A breast cancer prediction model incorporating familial and personal risk factors. Stat Med. doi: 10.1002/sim.1668. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amir E, Evans D, Shenton A, et al. Evaluation of breast cancer risk assessment packages in the family history evaluation and screening programme. J Med Genet. 2003;40:807–814. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.11.807. Abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feuer EJ, Wun LM. 1. Vol. 4. Bethesda, Md: National Cancer Institute; 1999. DevCan: probability of developing or dying of cancer. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson DE, Badzioch MD. Familial effects of prostate and other cancers on lifetime breast cancer risk. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1993;28:107–113. doi: 10.1007/BF00666423. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Couch FJ, DeShano ML, Blackwood MA, et al. BRCA1 mutations in women attending clinics that evaluate the risk of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1409–1415. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199705153362002. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shattuck-Eidens D, Oliphant A, McClure M, et al. Sequence analysis in women at high risk for susceptibility mutations. Risk factor analysis and implications for genetic testing. JAMA. 1997;278:1242–1250. Abstract. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frank TS, Manley SA, Olopade O, et al. Sequence analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2: correlation of mutations with family history and ovarian cancer risk. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:2417–2425. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.7.2417. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.A Common Problem. [January 8, 2004]. Available at: http://www.mja.com.au/public/mentalhealth/articles/turner/turcase.html. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Breast/Ovarian Cancer: Woman at High Risk. [January 8, 2004];Mid Atlantic Genetics Network. Available at: http://www.macgn.org/cases/p_case_b1.html. [Google Scholar]

- 17.deBock GH, Vliet Vlieland TP, Hageman GC, Oosterwijk JC, Springer MP, Kievit J. The assessment of genetic risk of breast cancer: a set of GP guidelines. Fam Pract. 1999;16:71–77. doi: 10.1093/fampra/16.1.71. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bondy ML, Newman LA. Breast cancer risk assessment models: applicability to African-American women. Cancer. 2003;97(1 suppl):230–235. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Euhus DM, Leitch AM, Huth JF, Peters GN. Limitations of the Gail model in the specialized breast cancer risk assessment clinic. Breast J. 2002;8:23–27. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4741.2002.08005.x. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McTiernan A, Kuniyuki A, Yasui Y, et al. Comparisons of two breast cancer risk estimates in women with a family history of breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001;10:333–338. Abstract. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fletcher S, Elmore J. Mammographic screening for breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1672–1680. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp021804. Abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.King MC, Marks J, Mandell J, et al. Breast and ovarian cancer risks due to inherited mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2. Science. 2003;302:643–646. doi: 10.1126/science.1088759. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rubinstein W. The genetics of breast cancer. In: Vogel V, editor. Management of Patients at High Risk for Breast Cancer. Malden, Mass: Blackwell Science; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Friedenson B. A current perspective on genetic testing for breast and ovarian cancer: the oral contraceptive decision. [January 8, 2004];Medscape General Medicine. 2001 Nov 2; Available at: http://www.medscape.com/Medscape/GeneralMedicine/journal/2001/v03.n06/mgm1102.01.frie/mgm1102.01.frie-01.html. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sevilla C, Julian-Reynier C, Eisinger F, et al. Impact of gene patents on the cost-effective delivery of care: the case of BRCA1 genetic testing. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2003;19:287–300. doi: 10.1017/s0266462303000266. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bonadona V, Sinilikova O, Lenoir G, Lasset C. Pretest prediction of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation risk by risk counselors and the computer model BRCAPro. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1582. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.20.1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Claus E, Risch N, Thompson W. Autosomal dominant inheritance of early-onset breast cancer. Implications for risk prediction. Cancer. 1994;73:643–651. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940201)73:3<643::aid-cncr2820730323>3.0.co;2-5. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kunreuther H. Risk analysis and risk management in an uncertain world. Risk Analysis. 2002;22:655–664. doi: 10.1111/0272-4332.00057. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grabrick DM, Hartmann L, Cerhan J, et al. Risk of breast cancer with oral contraceptive use in women with a family history of breast cancer. JAMA. 2000;284:1791–1798. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.14.1791. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marchbanks P, McDonald J, Wilson H, et al. Oral contraceptives and the risk of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:2025–2032. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013202. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stewart F, Harper C, Ellertson C, et al. Clinical breast and pelvic examination requirements for hormonal contraception. Current practice vs evidence. JAMA. 2001;285:2232–2239. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.17.2232. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Friedenson B, Friedenson H. Special article: Genetic testing for breast and ovarian cancer for women with a family history of breast cancer: weighing conflicting evidence about oral contraceptives. [January 8, 2004];Medscape General Medicine. 2002 Aug 30; Available at: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/440631_1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Narod SA, Dube MP, Klijn J, et al. Oral contraceptives and the risk of breast cancer in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1773. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.23.1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stoutjesdijk M, Boetes C, Jager G, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging and mammography in women with a hereditary risk of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:1095–1102. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.14.1095. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thune I, Brenn T, Lund E, Gaard M. Physical activity and the risk of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1999;336:1269–1275. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199705013361801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McTiernan A, Kooperberg C, White E, et al. Recreational physical activity and the risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women. The women's health initiative cohort study. JAMA. 2003;290:1331–1336. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.10.1331. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Calle E, Rodriquez C, Walker-Thurmond K, Thun M. Overweight, obesity and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of US adults. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1625–1638. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021423. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Willett W, Dietz, Colditz G. Guidelines for healthy weight. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:427–434. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199908053410607. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hamajima N, Hirose K, Tajima K, et al. Alcohol, tobacco and breast cancer — collaborative reanalysis of individual data from 53 epidemiological studies, including 58,515 women with breast cancer and 95,067 women without the disease. Br J Cancer. 2002;87:1234–1245. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600596. Abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thompson P, De Marini D, Kadlubar F, et al. Evidence for the presence of mutagenic arylamies in human breast milk and DNA adducts in exfoliated breast ductal epithelial cells. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2002;39:134–142. doi: 10.1002/em.10067. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wohlfahrt J, Melbye M. Age at any birth is associated with breast cancer risk. Epidemiology. 2001;12:68–73. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200101000-00012. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Modan B, Hartge P, Hirsh-Yechezkel G, et al. Parity, oral contraceptives, and the risk of ovarian cancer among carriers and non-carriers of a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:235–240. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107263450401. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Narod SA, Risch H, Moslehi R, et al. Oral contraceptives and the risk of hereditary ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:424–428. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199808133390702. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer, author. Breast cancer and breastfeeding: collaborative reanalysis of individual data from 47 epidemiological studies in 30 countries, including 50302 women with breast cancer and 96973 women without the disease. Lancet. 2002;360:187–195. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09454-0. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gofman J. Preventing Breast Cancer: The Story of a Major Proven Preventable Cause of This Disease. San Francisco, Calif: Committee for Nuclear Responsibility; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Friedenson B. Is mammography indicated for women with defective BRCA genes? Implications of recent scientific advances for the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of hereditary breast cancer. [January 15, 2004];Medscape General Medicine. 2000 2(1) Available at: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/408048. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Friedenson B. Roads to breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:936–937. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103223441214. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Writing Group for the Women's Health Initiative, author. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in health postmenopausal women: principal results from the women's health initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:321–334. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hays J, Ockene J, Brunner R, et al. Effects of estrogen plus progestin on health related quality of life. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gui GP, Hogben RK, Walsh G, A'Hern R, Eeles R. The incidence of breast cancer from screening women according to predicted family history risk: does annual clinical examination add to mammography? Eur J Cancer. 2001;37:1668–1673. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00207-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hershman D, Sundararajan V, Jacobson JS, et al. Outcomes of tamoxifen chemoprevention for breast cancer in very high-risk women: a cost-effectiveness analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:9–16. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.1.9. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Riggs B, Hartmann L. Drug therapy: selective estrogen receptor modulators — mechanisms of action and application to clinical practice. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:618–629. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022219. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Theisen C. For patients, prediction of cancer risk can be worrisome. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1360–1361. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.18.1360. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Metcalfe KA, Narod SA. Breast cancer risk perception among women who have undergone prophylactic bilateral mastectomy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1564–1569. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.20.1564. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hartmann L, Schaid D, Woods J, et al. Efficacy of bilateral prophylactic mastectomy in women with a family history of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:77–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901143400201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Meijers-Heijboer H, van Geel B, van Putten W, et al. Breast cancer after prophylactic bilateral mastectomy in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:159–164. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107193450301. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Eisinger F, Julian-Reynier C, Sobol H, et al. Acceptability of prophylactic mastectomy in cancer-prone women. JAMA. 2000;283:202–203. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.2.202. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kauf N, Satagopan J, Robson M, et al. Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1609–1615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020119. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rebbeck T, Lynch H, Neuhausen S, et al. Prophylactic oophorectomy in carriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1616–1622. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012158. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Haber D. Prophylactic oophorectomy to reduce the risk of ovarian and breast cancer in carriers of BRCA mutations. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1660–1662. doi: 10.1056/NEJMed020044. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Petricoin E, Ardekani A, Hitt B, et al. Use of proteomic patterns in serum to identify ovarian cancer. Lancet. 2002;359:572–577. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07746-2. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.O'Neill S. Quantitative breast cancer risk assessment. In: Vogel V, editor. Management of Patients at High Risk for Breast Cancer. Malden, Mass: Blackwell Science; 2001. pp. 63–93. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Costalas J, Itzen M, Malick J, et al. Communication of BRCA1 and BRCA2 results to at-risk relatives: a cancer risk assessment program's experience. Am J Med Genet. 2003;119C:11–18. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.10003. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Srivastava A, McKinnon W, Wood ME. Risk of breast and ovarian cancer in women with strong family histories. Oncology (Huntington) 2001;15:889–902. discussion 902, 905–907, 911–913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhou BB, Elledge S. The DNA damage response: putting checkpoints in perspective. Nature. 2000;408:433–439. doi: 10.1038/35044005. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Varley J, Haber D. Familial breast cancer and the hCHK2 1100delC mutation: assessing cancer risk. Breast Cancer Res. 2003;5:123–125. doi: 10.1186/bcr582. Abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Haber D. Roads leading to breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1566–1568. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011233432111. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Haber D. BRCA1: an emerging role in the cellular response to DNA damage. Lancet. 2000;355:2090–2091. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02371-0. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jyothish B, Ankathil R, Chandini R, et al. Deficient DNA repair proficiency: a potential marker for identification of high risk members in breast cancer families. Cancer Lett. 1998;124:9–13. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(97)00419-9. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ries LAG, Kosary CL, Hankey BF, Miller BA, Clegg L, Edwards BK, editors. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1973–1996: Tables and Graphs. Bethesda, Md: National Cancer Institute; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gail MH, Brinton LA, Byar DP, et al. Projecting individualized probabilities of developing breast cancer for white females who are being examined annually. Natl Cancer Inst. 1989;81:1879–1886. doi: 10.1093/jnci/81.24.1879. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Madigan MP, Ziegler RG, Benichou J, Byrne C, Hoover RN. Proportion of breast cancer cases in the United States explained by well-established risk factors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:1681–1685. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.22.1681. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bodian CA, Perzin K, Lattes R. Lobular neoplasia. Long term risk of breast cancer and relation to other factors. Cancer. 1996;78:1024–1034. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960901)78:5<1024::AID-CNCR12>3.0.CO;2-4. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ottesen G, Graversen H, Blichert-Toft M, Zedeler K, Andersen J. Lobular carcinoma in situ of the female breast. Short term results of a prospective nationwide study. Am J Surg Pathol. 1993;17:14–21. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199301000-00002. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bhatia S, Robison L, Oberlin O, et al. Breast cancer and other second neoplasms after childhood Hodgkin's disease. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:745–751. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603213341201. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Boyd N, Dite I, Stone J, et al. Heritability of mammographic density, a risk factor for breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:886–894. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013390. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Endogenous Hormones and Breast Cancer Collaborative Group, author. Body mass index, serum hormones, and breast cancer risk in postmenopausal women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1218. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]