Abstract

The fim genes which code for the fimbria protective antigens present in both the inactivated whole-cell and acellular vaccines were analyzed in 86 Canadian Bordetella pertussis isolates. At least one of the novel mutations identified was found to involve a surface epitope that has been mapped by serum antibodies from infected or vaccinated subjects.

Bordetella pertussis is an obligate human pathogen that infects the respiratory tract and is a major cause of severe childhood disease, with over a quarter million deaths worldwide in children attributed to it per year (6). Among clinical isolates that showed differences from the vaccine strains, genetic polymorphisms of two pertussis virulence factors, pertactin and pertussis toxin, have been described. It has been suggested that they may be related to the resurgence of pertussis in the last decade in Poland and The Netherlands (10, 17). However, similar studies in the United States (5), England (7), and France (18) did not support the hypothesis that genetic variations in pertactin and pertussis toxin have contributed to the ineffectiveness of the pertussis whole-cell vaccine. They suggested that the resurgence of pertussis in the last decade might be due to an increase in the susceptible adolescent and adult population as a result of waning active immunity from childhood vaccination.

Many virulence factors have been described for B. pertussis. We have examined another pertussis virulence antigen, the fimbria, an important protective antigen present in both the inactivated whole-cell and the acellular vaccines. Fimbria or pilus antigens of B. pertussis have been shown to be one of the many adhesins present on the surface of the bacteria. Two closely related but serologically distinct fimbriae are produced by B. pertussis. They provide the basis for serotyping of the bacteria into serotypes 2 and 3 (2). The major subunits of the serotype 2 and 3 fimbriae are proteins of 22 and 22.5 kDa, respectively. These proteins are encoded by the fim2 and fim3 genes (15, 16) to form repeating units that are assembled together to make up the body of the long filamentous structure characteristic of fimbriae or pili. Besides serving as serodeterminant factors, fimbriae have been shown to allow the bacteria to adhere to host cells via the major subunit, which binds to sulfated sugars such as heparin (8), and the minor subunit, which binds to the integrin Vla-5 (13). Despite the documented importance of this bacterial structure, there are few data related to genetic polymorphism of the fimbria antigens. We therefore performed serotyping and DNA sequencing of the fimbriae from Canadian clinical isolates of B. pertussis isolated from 1994 to 2002, and the results are presented in this communication.

Eighty-six clinical isolates of B. pertussis were obtained from different parts of Canada (Manitoba, Ontario, and Nova Scotia) between 1994 and 2002. Serotyping and DNA sequencing were performed to examine the antigenic and genetic diversity of the fimbriae and to compare their genetic diversity with other pertussis virulence antigens reported in the literature. Serotyping of B. pertussis was done by bacterial agglutination by using polyclonal rabbit antisera to agglutinogens 2 (product code 89/598) and 3 (product code 89/600) obtained from the National Institute of Biological Standards and Control (Potters Bar, Hertfordshire, United Kingdom) and for some strains also by using murine monoclonal antibodies to the Fim2 and Fim3 antigens (gifts from Dorothy Xing, National Institute of Biological Standards and Control). Selected strains were also serotyped by the indirect whole-cell enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) method similar to the one described elsewhere for serotyping of meningococci (1). All 86 strains were found to be serotype 3. Typical indirect whole-cell ELISA results for serotyping of B. pertussis isolates are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Serotyping of B. pertussis strains by indirect whole-cell ELISAa

| Strain | Avgb ELISA OD (result) with monoclonal Ab to:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| No-Ab control | Fim2 | Fim3 | |

| Reference strains | |||

| 2558 | 0.022 | >3.000 (+ve) | 0.057 (-ve) |

| Hav | 0.026 | 0.041 (-ve) | 0.539 (+ve) |

| 460 | 0.046 | 2.692 (+ve) | 0.525 (+ve) |

| Representative Canadian clinical isolates | |||

| Bp NML-005 | 0.020 | 0.034 (-ve) | 0.815 (+ve) |

| Bp NML-012 | 0.033 | 0.049 (-ve) | 0.536 (+ve) |

| Bp NML-040 | 0.015 | 0.024 (-ve) | 0.803 (+ve) |

| Bp NML-046 | 0.019 | 0.026 (-ve) | 0.782 (+ve) |

| Bp NML-054 | 0.018 | 0.027 (-ve) | 0.653 (+ve) |

OD, optical density; Ab, antibody; +ve, positive; −ve, negative.

Average of duplicate determinations.

To determine if there might have been minor changes in the fimbria antigens not detected by our serotyping antibodies, we examined the diversity of the genetic sequence of the fimbria 3 antigen of our strains by performing DNA sequencing of the entire open reading frame of their fim3 genes. Primers for amplification and sequencing of the fim3 genes were designed from an alignment of the B. pertussis fim2 and fim3 gene sequences (GenBank accession no. Y00527 and X51543, respectively): Fim3F, 5′-CCC CCG GAC CTG ATA TTC TGA TG-3′, and Fim3R, 5′-GCT GAG CGT GCT GAA GGA CAA GAT-3′. Both strands of the 800-bp product were sequenced using an ABI Prism 3100 DNA sequencing system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.), and the data were compiled by using software from DNASTAR, Inc., Madison, Wis.

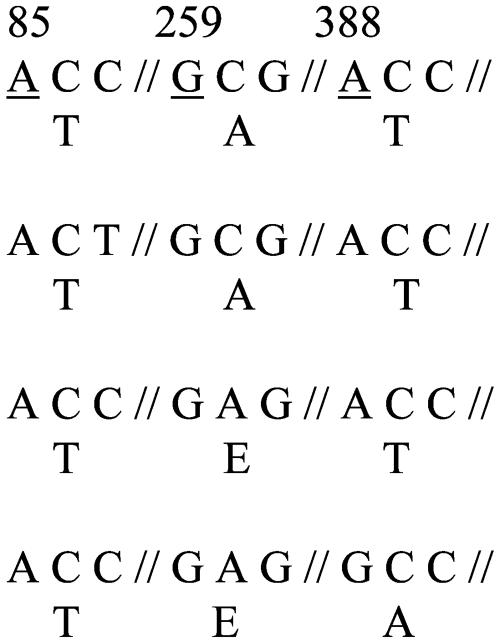

The fim3 gene sequences of the 86 Canadian clinical isolates and five reference strains (2558, Hav, 460, ATCC 9797, and DSM 5571) of B. pertussis were classified into four types. Fifty-four of 86 clinical isolates (62.8%) were determined to have the sequence type Fim3B, a novel type not found in the GenBank database nor described in the literature. Fim3B was found in strains isolated from all three provinces (Manitoba, Nova Scotia, and Ontario) and is characterized by an alanine-to-glutamic acid mutation at amino acid position 87. Twenty-eight strains (32.6%; also found in all three provinces) belonged to the type Fim3A, which is identical to the fim3 sequence of B. pertussis Tohama strain, serotype 2 (GenBank accession no. X51543). One clinical isolate (1.2%) from the province of Ontario was found to have a Fim3 protein sequence identical to that of Fim3A, but its fim3 gene contained a single synonymous mutation at nucleotide position 87 (C to T) and its sequence type was designated Fim3A*. The remaining three strains (3.5%), all recovered from pertussis patients in Manitoba, have another novel fim3 gene sequence type, designated Fim3C. Fim3C is characterized by an alanine-to-glutamic acid mutation at amino acid position 87 and a threonine-to-alanine mutation at amino acid position 130. The distribution of the strains according to their fim3 sequence type and the polymorphic region of the different Fim3 sequence types as well as their geographic and temporal distributions are summarized in Table 2. Strains with the single nonsynonymous mutation in their fim3 genes (Fim3B sequence type) did not seem to be restricted to one region in Canada, since such strains were found in all three provinces throughout the study period (1994 to 2002). In contrast, strains with the Fim3C sequence type showing two nonsynonymous mutations in their fim3 genes were found only in Manitoba in 2001.

TABLE 2.

Polymorphisms in the B. pertussis fimbria fim3 gene, showing number of strains for each sequence type and their GenBank accession numbers

| Fim 3 type | Polymorphic region of the Fim3 sequence typea | No. of strains | Origine (no. of strains) | Yr(s) | GenBank accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fim3 A | 33b | ON (14) | 1994-2002 | X51543 | |

| MB (2) | 2001-2002 | ||||

| NS (12) | 1995-1996c | ||||

| Fim3 A* | 1 | ON (1) | 1994 | AY464179 | |

| Fim3 B | 54 | ON (33) | 1994-2002 | AY464180 | |

| MB (7) | 1998-2002 | ||||

| NS (14) | 1996d | ||||

| Fim3 C | 3 | MB (3) | 2001 | AY464181 |

Numbers refer to the underlined residues. Amino acids are indicated underneath each codon. Numbering is relative to the start of the open reading frame. The fim3A sequence was reported by Mooi et al. (16).

Including the reference strains ATCC 9797, DSM 5571, 2558, Hav, and 460.

Year unknown for six strains.

Year unknown for 10 strains.

Origin of strains by province: ON, Ontario; MB, Manitoba; NS, Nova Scotia.

All 86 Canadian B. pertussis strains were found to be serotype 3, as were most of the strains studied in the 1970s (21, 22). The same serotype of B. pertussis was also found in strains responsible for an outbreak of pertussis that involved over 400 cases in Montreal, Canada, from 1990 to 1991 (14). The consistency of finding serotype 3 strains in Canada may involve a combination of factors. For example, the serotype 2 antigen in whole-cell vaccines that are comprised of both serotype 2 and 3 antigens produces a stronger immune response in the vaccinated subjects than the serotype 3 antigen does (20). Due to the weaker immune response to the serotype 3 antigen, partially immunized children had been found to be infected mainly by serotype 3 strains (19). This may be especially true in Canada since some of the whole-cell vaccines used in the 1970s and 1980s were of lower efficacy (3, 11).

Antibodies are produced to the serotyping fimbria antigen as a result of natural infections as well as immunization with whole-cell vaccines (25). It is therefore reasonable to postulate that the fimbria antigens are under selective pressure due to the presence of serospecific immunity in the population. Genetic polymorphisms (four distinct sequence types) were found in the fim3 gene among the Canadian serotype 3 B. pertussis isolates. Serotype 3 isolates with the novel fim3 gene sequences (types 3B and 3C) were different from the fim3 gene sequence of a serotype 2 strain (Tohama strain, GenBank accession no. X51543). It can be assumed that, in the serotype 2 strain, the fim3 gene was not expressed to produce the Fim3 fimbriae and was therefore not subjected to immune pressure to change. The finding of different fim3 gene sequences (especially types 3B and 3C) may be indirect evidence that these antigens are under immune selection. The observed nonsynonymous nucleotide changes on a surface protein like fimbria may be an indication of the bacterium's ability to adapt and evade the immune system. Genetic polymorphisms described for pertactin and pertussis toxins have been attributed to the ability of the bacterium to resist induced immunity and cause an increase in disease activities in the last decade (7, 9, 10, 17). Therefore, it is possible that the genetic polymorphisms found in the fim3 genes of recent Canadian B. pertussis strains may be acting in a similar fashion to contribute to increased infections in Canada in the last decade. However, it is equally possible that the genetic polymorphisms observed as a result of immune selection in the circulating strains can occur without any effect on the efficacy of vaccines in protecting against pertussis.

The possibility of nonselective mutations, however, cannot be ruled out until further evidence can be found to demonstrate corresponding antigenicity changes in these presumably novel serotype 3 fimbriae and unique serological responses in sera from pertussis patients infected with strains of these novel fimbria types. The synonymous mutation found in the single isolate with the Fim3A* sequence type probably represents a random mutation with no significant consequence since no amino acid change is expected in the fimbrial protein. The nonsynonymous mutations seen in the other B. pertussis strains may also represent an antigenic drift that did not alter the serospecificity of the strains and may not have any impact on the protective capacity of the present vaccines. However, mutations which change the serospecificity of strains will more likely affect the ability of the present vaccines to protect against strains harboring such mutations.

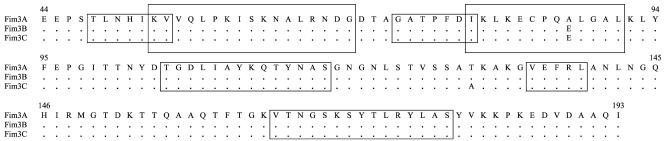

The two fimbria variant types (types 3B and 3C) that contained nonsynonymous mutations also have at least one mutation site (Fig. 1) found to occur in a presumable surface epitope or region that has been determined to react with serum antibodies from human subjects infected with or vaccinated against pertussis (25). Therefore, data presented in this study may suggest that fimbria antigens are being subjected to immune selection due to vaccine-induced or natural antibody-driven adaptation. The Fim3A sequence type was found in the Japanese vaccine strain Tohama (serotype 2) (accession no. X51543) and the reference strains Hav and 134 (results from this study and authors' unpublished data). Both strain Tohama and the reference strain 134 were isolated in the 1950s or earlier (9, 24). In contrast, strains with the Fim3B and Fim3C DNA sequence types were isolated from pertussis patients during the period of 1994 to 2002 and were found to contain either single or double nonsynonymous nucleotide polymorphisms. All three strains with the Fim3C sequence type were isolated from the same province and gave identical pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) patterns (unpublished data, National Microbiology Laboratory). DNA profile relatedness groups of pertussis strains obtained by PFGE have been reported to correlate with both their pertactin and pertussis toxin S1 subunit DNA sequence types (5, 24). Therefore, the use of fim sequences as epidemiological markers may deserve further evaluation, but PFGE is clearly more discriminative than DNA sequencing of a single target gene.

FIG. 1.

Polymorphisms in the amino acid sequence of the Fim3 protein of B. pertussis. Letters refer to amino acid residues. Dots indicate identity. Boxed regions indicate Fim3 epitopes recognized by human sera (25), suggesting surface location.

The identification of nonsynonymous point mutations in fimbriae is similar to the reported genetic polymorphisms described for other virulence factors of B. pertussis such as pertussis toxin subunit S1 and pertactin (7, 10, 17). Recent multilocus sequence typing data showed that, besides the four insertions and deletions detected, extensive DNA sequencing of gene segments from 15 different surface proteins of B. pertussis revealed only 22 point mutations (23). No sequence variations were found in the fim3 genes examined among the 12 strains reported in this study.

Finally, not all of the genetic polymorphism studies reported in the literature (10, 17) provided serological or structural evidence to support the idea that the sequence changes were translated into changes in the protein structures that would impart serological or immunological specificities. Protection against B. pertussis strains containing genetic variations of their pertussis toxin and pertactin has been evaluated in a murine model by active immunity induced by pertussis vaccine (4) or by an in vitro toxin neutralization model with antiserum induced by pertussis vaccines (12). Therefore, further studies should also examine the specificity of the different Fim3 types and examine if these different Fim3 types will have any impact on the protective immunity induced by the present pertussis vaccines.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The partial sequences of fim3 genes showing novel mutations described in this study have been deposited in GenBank (National Center for Biotechnology Information) with the assigned accession numbers AY464179, AY464180, and AY464181.

Acknowledgments

We thank the following persons for their contributions: Dorothy Xing of the National Institute of Biological Standards and Controls, United Kingdom, for the gift of the anti-Fim2 and anti-Fim3 monoclonal antibodies and Nicole Guiso of Institut Pasteur, France, for the gift of the reference strains. We also acknowledge the DNA core facility at Health Canada's NML for the DNA sequencing work. R. Tsang also wishes to thank Lai King Ng for her interest and support at the initial phase of this project.

Part of this work was supported by a grant from Health Canada's Office of Biotechnology and Science.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdillahi, H., and J. T. Poolman. 1987. Whole-cell ELISA for typing Neisseria meningitidis with monoclonal antibodies. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 48:367-371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashworth, L. A. E., L. I. Irons, and A. B. Dowsett. 1982. Antigenic relationship between serotype-specific agglutinogen and fimbriae of Bordetella pertussis. Infect. Immun. 37:1278-1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bentsi-Enchill, A., S. A. Halperin, J. Scott, K. MacIsaac, and P. Duclos. 1997. Estimates of the effectiveness of a whole-cell pertussis vaccine from an outbreak in an immunized population. Vaccine 15:301-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boursaux-Eude, C., S. Thiberge, G. Carletti, and N. Guiso. 1999. Intranasal murine model of Bordetella pertussis infection: II. Sequence variation and protection induced by a tricomponent acellular vaccine. Vaccine 17:2651-2660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cassiday, P., G. Sanden, K. Heuvelman, F. Mooi, K. M. Bisgard, and T. Popovic. 2000. Polymorphisms in Bordetella pertussis pertactin and pertussis toxin virulence factors in the United States, 1935-1999. J. Infect. Dis. 182:1402-1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crowcroft, N. S., and J. Britto. 2002. Whooping cough—a continuing problem. BMJ 324:1537-1538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fry, N. K., S. Neal, T. G. Harrison, E. Miller, R. Matthews, and R. C. George. 2001. Genotypic variation in the Bordetella pertussis virulence factors pertactin and pertussis toxin in historical and recent clinical isolates in the United Kingdom. Infect. Immun. 69:5520-5528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geuijen, C. A. W., R. J. L. Williams, and F. R. Mooi. 1996. The major fimbrial subunit of Bordetella pertussis binds to sulfated sugars. Infect. Immun. 64:2657-2665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guiso, N., C. Boursaux-Eude, C. Weber, S. Z. Hausman, H. Sato, M. Iwaki, K. Kamachi, T. Konda, and D. Burns. 2001. Analysis of Bordetella pertussis isolates collected in Japan before and after introduction of acellular pertussis vaccines. Vaccine 19:3248-3252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gzyl, A., E. Augustynowicz, L. van Loo, and J. Slusarczyk. 2002. Temporal nucleotide changes in pertactin and pertussis toxin genes in Bordetella pertussis strains isolated from clinical cases in Poland. Vaccine 20:299-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halperin, S. A., R. Bortolussi, D. MacLean, and N. Chisholm. 1989. Persistence of pertussis in an immunized population: results of the Nova Scotia enhanced pertussis surveillance program. J. Pediatr. 115:686-693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hausman, S. Z., and D. Burns. 2000. Use of pertussis toxin encoded by ptx genes from Bordetella bronchiseptica to model the effects of antigenic drifts of pertussis toxin on antibody neutralization. Infect. Immun. 68:3763-3767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hazenbos, W. L., C. A. Geuijen, B. M. van den Berg, F. R. Mooi, and R. van Furth. 1995. Bordetella pertussis fimbriae bind to human monocytes via the minor fimbrial subunit FimD. J. Infect. Dis. 171:924-929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knowles, K., M. Lorange, R. C. Matthews, and N. W. Preston. 1993. Characterization of outbreak and vaccine strains of Bordetella pertussis—Quebec. Can. Commun. Dis. Rep. 19:186-187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Livey, I., C. J. Duggleby, and A. Robinson. 1987. Cloning and nucleotide sequence analysis of the serotype 2 fimbrial subunit gene of Bordetella pertussis. Mol. Microbiol. 1:203-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mooi, F. R., A. ter Avest, and H. G. J. van der Heide. 1990. Structure of the Bordetella pertussis gene coding for the serotype 3 fimbrial subunit. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 66:327-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mooi, F. R., H. van Oirschot, K. Heuvelman, H. G. J. van der Heide, W. Gaastra, and R. J. L. Willems. 1998. Polymorphism in the Bordetella pertussis virulence factors P.69/pertactin and pertussis toxin in The Netherlands: temporal trends and evidence for vaccine-driven evolution. Infect. Immun. 66:670-675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Njamkepo, E., F. Rimlinger, S. Thiberge, and N. Guiso. 2002. Thirty-five years' experience with the whole-cell pertussis vaccine in France: vaccine strains analysis and immunogenicity. Vaccine 20:1290-1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Preston, N. W. 1985. Change in serotype of pertussis infection in Britain. Lancet i:510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Preston, N. W. 1988. Pertussis today, p. 1-18. In A. C. Wardlaw and R. Parton (ed.), Pathogenesis and immunity in pertussis. John Wiley, Chichester, United Kingdom

- 21.Rossier, E., and F. Chan. 1977. Bordetella pertussis in the National Capital Region: prevalent serotype and immunization status of patients. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 117:1169-1171. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Toma, S., H. Lo, and M. Magus. 1978. Bordetella pertussis serotypes in Canada. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 119:722-724. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Loo, I. H. M., K. J. Heuvelman, A. J. King, and F. R. Mooi. 2002. Multilocus sequence typing of Bordetella pertussis based on surface protein genes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:1994-2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weber, C., C. Boursaux-Eude, G. Coralie, V. Caro, and N. Guiso. 2001. Polymorphism of Bordetella pertussis isolates circulating for the last 10 years in France, where a single effective whole-cell vaccine has been used for more than 30 years. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:4396-4403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williamson, P., and R. Matthews. 1996. Epitope mapping the Fim2 and Fim3 proteins of Bordetella pertussis with sera from patients infected with or vaccinated against whooping cough. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 13:169-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]