Abstract

Background

Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia type 1 (MEN1, OMIM 131100) is an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by endocrine tumors of the parathyroids, pancreatic islets and pituitary. The disease is caused by the functional loss of the tumor suppressor protein menin, coded by the MEN1 gene. The protein sequence has no significant homology to known consensus motifs. In vitro studies have shown menin binding to JunD, Pem, Smad3, NF-kappaB, nm23H1, and RPA2 proteins. However, none of these binding studies have led to a convincing theory of how loss-of-menin leads to neoplasia.

Results

Global gene expression studies on eight neuroendocrine tumors from MEN1 patients and 4 normal islet controls was performed utilizing Affymetrix U95Av2 chips. Overall hierarchical clustering placed all tumors in one group separate from the group of normal islets. Within the group of tumors, those of the same type were mostly clustered together. The clustering analysis also revealed 19 apoptosis-related genes that were under-expressed in the group of tumors. There were 193 genes that were increased/decreased by at least 2-fold in the tumors relative to the normal islets and that had a t-test significance value of p < = 0.005. Forty-five of these genes were increased and 148 were decreased in the tumors relative to the controls. One hundred and four of the genes could be classified as being involved in cell growth, cell death, or signal transduction. The results from 11 genes were selected for validation by quantitative RT-PCR. The average correlation coefficient was 0.655 (range 0.235–0.964).

Conclusion

This is the first analysis of global gene expression in MEN1-associated neuroendocrine tumors. Many genes were identified which were differentially expressed in neuroendocrine tumors arising in patients with the MEN1 syndrome, as compared with normal human islet cells. The expression of a group of apoptosis-related genes was significantly suppressed, suggesting that these genes may play crucial roles in tumorigenesis in this syndrome. We identified a number of genes which are attractive candidates for further investigation into the mechanisms by which menin loss causes tumors in pancreatic islets. Of particular interest are: FGF9 which may stimulate the growth of prostate cancer, brain cancer and endometrium; and IER3 (IEX-1), PHLDA2 (TSS3), IAPP (amylin), and SST, all of which may play roles in apoptosis.

Background

Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia type 1 (MEN1, OMIM 131100) is an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by endocrine tumors of parathyroid, pancreatic islets and pituitary [1]. The prevalence of MEN1 is estimated to be 2–10 per 100,000 [2]. Based on loss of heterozygosity in tumors and Knudson's "two-hit" hypothesis, the MEN1 gene was classified as a tumor suppressor [2,3] and the gene was isolated in 1997 by positional cloning [4]. The MEN1 gene spans 9 kb of the genome, is comprised of 10 exons, and codes for a 610 amino acid protein termed menin [4]. More than 300 independent germline and somatic mutations have been identified [5]. Recently, five new germline mutations which affect splicing of pre-mRNA transcribed from MEN1 gene were identified in our laboratory [6]. The nature of all the disease-inducing mutations points to a loss of function of menin, which is characteristic of a tumor suppressor. Database analysis of menin protein sequence reveals no significant homology to known consensus protein motifs. Menin is widely expressed in both endocrine and non-endocrine tissues [4]. Menin is primarily localized in the nucleus and contains two nuclear localization signal sequences near the carboxyl terminus of the protein [7].

Studies on the function of menin have not yielded a clear picture as to the role of menin as a tumor suppressor; however, the results of these studies suggest some interesting possibilities. Two groups [8,9], based on yeast two-hybrid screening of a human adult brain library, reported that menin interacts with JunD (a member of the AP-1 transcription factor family) and represses JunD mediated transcription. Recently, Agarawal et al[10] reported that when JunD loses its association with menin it becomes a growth promoter rather than a growth suppressor. Other reports suggest some relevance of the menin-JunD interaction. JunD null male mice exhibit impaired spermatogenesis [11]. In postnatal mouse, Men1 was found to be expressed in testis (spermatogonia) at high levels [12]. Lemmens et al [13] by screening a 12.5 dpc mouse embryo library with menin, identified a homeobox-containing mouse protein, Pem. Interestingly, both menin and Pem showed a very similar pattern of expression, especially in testis and Sertoli cells. These findings along with the fact that some MEN1 patients have idiopathic oligospermia and non-motility of spermatozoa [14] suggest that menin-JunD and menin-PEM interactions may play a vital role in spermatogenesis. Kaji et al [15] observed that menin interacts with Smad3 and inactivation of the former blocks transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) signaling in pituitary tumor derived cell lines. Recently, two more menin interacting proteins, NF-kappa B [16] and a putative tumor metastasis suppressor nm23 [17] have been identified. Interactions among AP-1 family members, Smad proteins and NF-kappa B have been documented [18-21] and such cross talk among signaling pathways is not uncommon.

Despite the above studies, a clear consensus of the molecular mechanisms leading to neoplasia, following the loss of menin, has not emerged. Very little is known about the gene expression changes in human neuroendocrine tumors following the loss of menin. Global gene expression analyses, using cDNA microarrays, have been used to classify other human tumors into clinically distinct categories [22-26]. Wu [27] has discussed the mathematical and statistical considerations for the use of DNA microarrays to identify genes of specific interest, and Harkin [28] has used expression profiling to identify downstream transcriptional targets of the BRCA1 tumor suppressor gene. Our objective was to identify genes that might be directly or indirectly over or under-expressed as a consequence of loss of menin expression.

Results

Patients and Controls

Eight neuroendocrine tumors from six MEN1 patients were included in this study. The patient ages were 19, 22, 42, 51, 57, and 57 years at the time of surgery (Table 1). One was female, and five were male. Two of the patients had clinical and laboratory findings consistent with insulinoma. Three tumors were analyzed from one of these patients. One patient had findings consistent with VIP-oma (vasoactive intestinal polypeptide secreting tumor). Two patients, with no specific symptoms, had non-functioning or pancreatic polypeptide secreting tumors. One patient had symptoms of gastrinoma from a duodenal tumor (not used for this analysis). A pancreatic tumor from this patient, found incidentally, was used in this study. Pathological examination of tumors from the 6 patients resulted in the classification of 3 insulinomas, 3 neuroendocrine tumors, 1 VIP-oma and 1 glucagonoma. The ages of the individuals donating normal pancreatic islets were 42, 52(2), and 56 years. Two were female, and two were male.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients and normal subjects.

| Pt.# | T # | Age | Sex | Clinical | LN Mets | T Vol. (ml) | Menin Defect [6] |

| 1 | 1 | 19 | F | Insulinoma | 0/1 | 8.28 | Large Deletion, exon 1 & 2 |

| 2 | 2 | 42 | M | Neuroendocrine Tumor | 0/14 | 18.75 | Nonesense Mutation, exon 7 |

| 6 | 6 | 60 | M | VIP-oma | 1/16 | 288 | 8 bp Deletion, exon 5 |

| 7 | 7 | 51 | M | Neuroendocrine Tumor | 2/30 | 3.75 | 2 bp Deletion, exon 2 |

| 8 | 8–10 | 22 | M | Insulinoma | 2/8 | 6.9 | 2 bp Deletion, exon 2 |

| 11 | 11 | 57 | M | Gastrinoma | 1/1 | 0.5 | 4 bp Deletion, exon 3 |

| N1 | N1 | 52 | M | Normal | NA | NA | NA |

| N2 | N2 | 56 | F | Normal | NA | NA | NA |

| N3 | N3 | 52 | F | Normal | NA | NA | NA |

| N4 | N4 | 42 | M | Normal | NA | NA | NA |

Quality of Hybridization

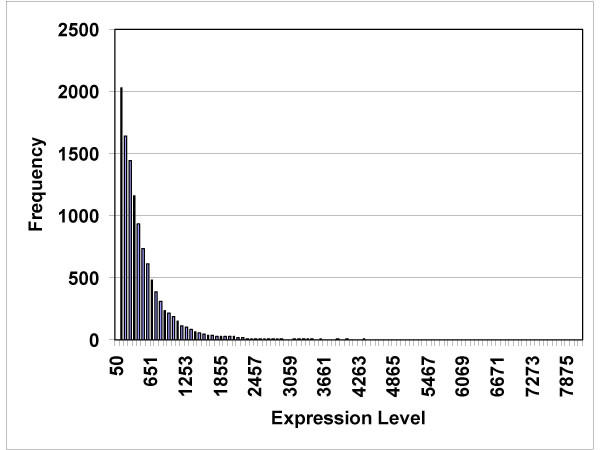

The RNA isolated from 8 tumor specimens (6 patients) and 4 normal islet preparations was of acceptable quality for hybridization, as determined by preliminary small hybridizations on test chips. The dChip computer program returned data concerning the percent of genes judged to be present, and the percent of single and array outlier events (Table 2). The expression data from one normal islet preparation had 5.94% array outliers, which prompted dChip to issue a warning (a warning indicates more than 5% array outliers detected). However, since we had only four normal specimens, we elected to include all four in our analysis. The average level of gene expression was computed for each gene (Figure 1). The average gene expression level for all genes followed an exponentially decreasing pattern; the greatest number of genes had expression values less than 100, and only a few genes had expression levels greater than 4000.

Table 2.

Overall statistics on the quality of each the processed GeneChips. One chip was used for each tumor/normal specimen. The "Median Intensity" refers to the overall brightness of the fluorescence of the genes. The "Present Call" refers to whether the gene was "present" or "absent".

| Chip Name | Median Intensity | Present Call (%) | Array outlier % | Single outlier % | Warning |

| T1 | 170 | 49.4 | 1.12 | 0.11 | |

| T2 | 107 | 46.2 | 1.54 | 0.15 | |

| T6 | 160 | 51.4 | 1.16 | 0.12 | |

| T7 | 132 | 47.7 | 0.50 | 0.08 | |

| T8 | 158 | 51.0 | 0.59 | 0.10 | |

| T9 | 114 | 48.9 | 0.66 | 0.10 | |

| T10 | 158 | 50.6 | 0.42 | 0.07 | |

| T11 | 121 | 46.1 | 3.34 | 0.30 | |

| N1 | 142 | 48.4 | 2.65 | 0.26 | |

| N2 | 179 | 49.7 | 2.72 | 0.24 | |

| N3 | 75 | 48.3 | 3.38 | 0.31 | |

| N4 | 73 | 33.2 | 9.50 | 0.63 | * |

Figure 1.

Histogram showing the frequency of genes being expressed at levels between 50 and 7875 (arbitrary expression units).

Overall Consistency of Gene Expression

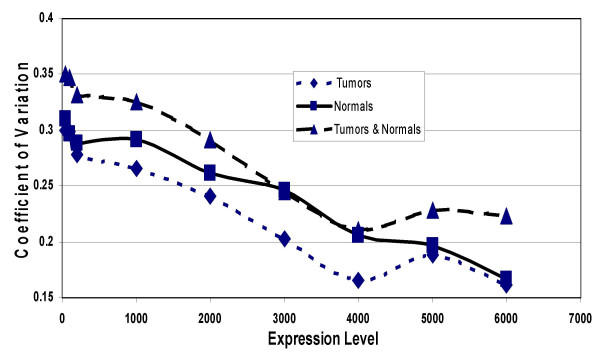

Average expression and standard deviation was computed for each gene in both the group of 4 normal islets, and the group of 8 islet tumors and expressed as the coefficient of variation (CV). Genes with average expression levels less than 50 were excluded from this analysis. Figure 2 shows that the average (11,416 genes and expressed sequences) CV in the group of 8 tumors was 30%. There was a linear regression of CV values as the average minimum expression level of the genes increased. Genes with an average minimum expression level of 7000 or more had an average CV level of 12.7%. The analysis of genes expressed in the normal islets gave similar results. However, when the tumors were combined with the normals, the CV was higher than either group alone. This was caused by the true differences in gene expression levels between the tumors and the normals.

Figure 2.

Coefficient of variation (CV) of genes being expressed at levels between 50 and 6000. For each gene expressed at an average level of 50 or above, the CV was computed for the group of 8 tumors, for the group of 4 normals, and for the group of all 12 tumors and normals. As the lower limit of expression was increased, the number of genes represented in the CV decreased: there were 12,000 genes with expression levels of 50 or more, but only a few genes with expression levels of 6,500 or more.

Clustering

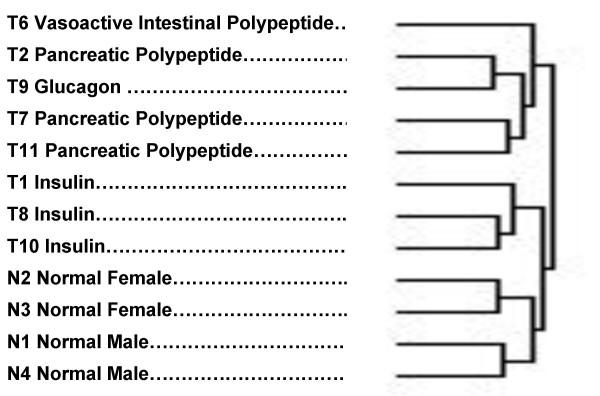

The experimental groups were clustered (figure 3) using a hierarchical clustering procedure [29,30]. This cluster was based on the inclusion of all genes which had 33% to 67% of "present" calls made by the GeneChip software. The assignment of tumor type was made on the basis of principal hormone messenger RNA levels that were consistent with the clinical and biochemical findings (Table 3). The principal bifurcation in the clustering occurred between the group that included the normal specimens and the three tumors with a predominance of insulin expression, on one hand, and the other tumor types on the other. The four normal islet preparations clustered together, separate from the tumors. Among the normal islets, the females clustered separately from the males. Among the tumors, all 3 insulinomas clustered together, separate from the VIP-oma, the glucagonoma and the PP-omas (pancreatic polypeptide producing tumors). It is also interesting that all the specimens clustered in a pattern of increasing malignancy going from normal at the bottom of the cluster to most malignant at the top.

Figure 3.

Clustering of tumors and normals according to overall gene expression patterns. The predominant type of hormone expression (Table 3) is noted for each tumor/normal specimen.

Table 3.

Gene expression levels of islet hormone mRNAs in tumors and normals. VIP: Vasoactive intestinal polypeptide; PP: Pancreatic polypeptide.

| T1 | T2 | T6 | T7 | T8 | T9 | T10 | T11 | N1 | N2 | N3 | N4 | |

| pre-Gastrin | 864 | 530 | 678 | 392 | 600 | 383 | 209 | 395 | 1036 | 775 | 28 | 1192 |

| Insulin | 9990 | 13 | 179 | 401 | 10195 | 240 | 8971 | 1831 | 10010 | 9752 | 9580 | 8158 |

| Glucagon | 10 | 6482 | 2783 | 1198 | 10 | 8370 | 10 | 10 | 9037 | 8425 | 9043 | 7800 |

| VIP | 351 | 278 | 10243 | 374 | 334 | 276 | 362 | 202 | 806 | 436 | 334 | 389 |

| PP | 246 | 7257 | 577 | 5845 | 70 | 1805 | 211 | 8895 | 1897 | 7605 | 3598 | 1177 |

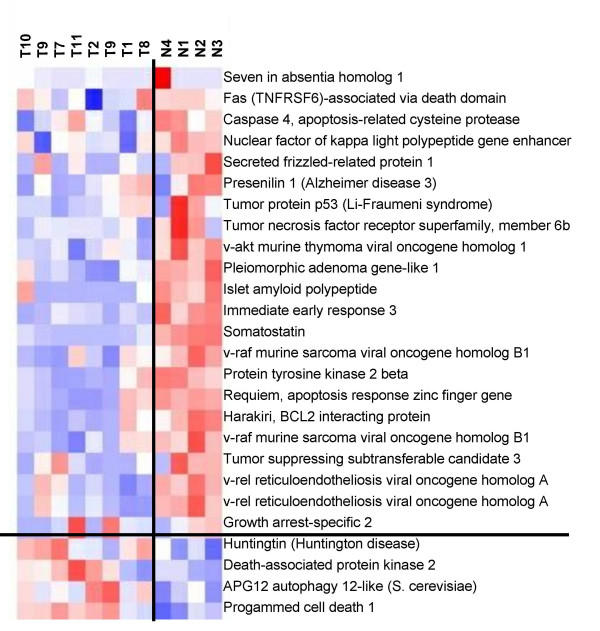

The genes were also clustered by the dChip software. A group of apoptosis-related genes was identified whose expression was significantly correlated with the Tumor/Normal assignment of the data. Twenty-four apoptosis-related genes represented by 26 different Affymetrix probes were identified in the overall hierarchical clustering. Nineteen of these genes were more highly expressed in the normal islets than in the islet tumors (Figure 4). Eighteen of the nineteen under expressed genes in the set of tumors had t-test p values (tumor vs. normal) <= 0.037. All five of the apoptosis-related genes, that were more highly expressed in the tumors, had t-test p values >0.05

Figure 4.

Clustering of apoptosis-related genes in tumors (T) and normals (N). Pink indicates strong, white indicates moderate, and blue indicates weak expression.

Evaluation of Student's t-test

Since the Student's t-test was designed to compare only one parameter in two populations, the simultaneous measurement of multiple genes might lead to an excessive number of false positives. In order to empirically determine the potential false positive rate, we started with 923 genes which had a p value <=.05 and repeatedly scrambled the individual tests into groups 4 and 8 and then performed new t-tests. The average number of genes having a p value = < .05 in 20 such scrambles was 51 (5.5% of 923 genes). This was only slightly more than the 46 genes expected (0.05 × 923). We therefore concluded that there was little chance of excess false positives in repeatedly using the Student's t-test.

Hormone Expression Profiles

In order to obtain a better picture of the nature of the tumors and normal islets in this study, the expression levels of the principal hormone RNA of pancreatic islets was examined (Table 3). Tumors 1, 8, and 10 had high levels of insulin expression and came from patients with the clinical diagnosis of insulinoma. Tumor 6 had high levels of VIP and came from a patient with the clinical syndrome of VIP-oma. Tumors 2 and 7 had high levels of pancreatic polypeptide, and came from patients with only a diagnosis of neuroendocrine tumor. Tumor 9, which came from a patient with a clinical diagnosis of insulinoma had a high level of glucagon expression; the clinical diagnosis was apparently due to the other tumor (#8) which did have a high level of insulin expression. One other apparent discrepancy between the clinical diagnosis and hormone expression profile occurred with tumor 11, which had high a level of glucagon expression. This patient had an additional duodenal tumor that was responsible for the gastrin secretion and the clinical diagnosis. All the normal islet preparations had high levels of insulin and glucagon expression, as expected.

Comparison of tumor and normal gene expression

The reporting of differentially expressed genes was restricted to those in which the absolute ratio of Tumor to Normal was greater than or equal to 2, and which had a Student's t-test p value of less than or equal to .005. There were 193 genes that met the criteria. Expressed sequences with no known protein product were not included. There were 45 genes that were increased in the tumors relative to the normals, and 148 genes that were decreased. The fold-change in expression values ranged from +179 to -449. Genes were assigned to functional categories based on the Gene Ontology Consortium assignments http://www.geneontology.org/. There were 16 genes related to cell growth, 13 genes related to signal transduction, and 16 genes related to other functions which were increased in the group of tumors relative to the group of normal islets (Table 4). There were 44 genes related to cell growth, 10 related to cell death, 10 related to embryogenesis, 5 related to nucleic acid binding, 21 related to cell signaling, and 58 related to other functions in the group of genes which were decreased in the islet tumors relative to the controls (Tables 5, 6, 7, 8).

Table 4.

Genes significantly increased in tumors.

| GeneBank Accession | Gene | Symbol | Normal Mean | Tumor Mean | Fold Change | P value |

| Cell Growth/Cycle | ||||||

| X16323 | hepatocyte growth factor | HGF | 11 | 116 | 10.77 | 0.003305 |

| AB017642 | oxidative-stress responsive 1 | OSR1 | 58 | 428 | 7.41 | 0.000819 |

| AL078641 | phorbolin-like protein | APOBEC3G | 15 | 92 | 6.21 | 0.000158 |

| L17128 | gamma-glutamyl carboxylase | GGCX | 64 | 346 | 5.37 | 0.000018 |

| D21089 | xeroderma pigmentosum, complementation group C | XPC | 292 | 1278 | 4.38 | 0.000284 |

| AL050223 | vesicle-associated membrane protein 2 | VAMP2 | 360 | 1533 | 4.26 | 0.002196 |

| D38145 | prostaglandin I2 synthase | PTGIS | 29 | 121 | 4.09 | 0.000448 |

| AF092563 | structural maintenance of chromosomes 2-like 1 | SMC2L1 | 58 | 185 | 3.21 | 0.002352 |

| AF006087 | actin related protein 2/3 complex, subunit 4 | ARPC4 | 292 | 865 | 2.96 | 0.000565 |

| AC004537 | inhibitor of growth family, member 3 | ING3 | 46 | 114 | 2.47 | 0.003976 |

| AF013168 | tuberous sclerosis 1 | TSC1 | 35 | 86 | 2.45 | 0.001232 |

| AJ236876 | ADP-ribosyltransferase polymerase)-like 2 | ADPRTL2 | 32 | 76 | 2.34 | 0.003874 |

| Cell Death/Apoptosis | ||||||

| D38435 | postmeiotic segregation increased 2-like | PMS2L1 | 74 | 193 | 2.6 | 0.002976 |

| M61906 | phosphoinositide-3-kinase, regulatory subunit | PIK3R1 | 43 | 104 | 2.4 | 0.004387 |

| Signal Transduction | ||||||

| U26710 | Cas-Br-M ectropic retroviral transforming sequence b | CBLB | 21 | 177 | 8.4 | 0.000082 |

| AB010414 | guanine nucleotide binding protein, gamma 7 | GNG7 | 59 | 334 | 5.68 | 0.003835 |

| U59913 | mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 5 | MADH5 | 14 | 73 | 5.22 | 0.004731 |

| AB004922 | Homo sapiens gene for Smad 3 | MADH3 | 93 | 443 | 4.76 | 0.001024 |

| L11672 | zinc finger protein 91 | ZNF91 | 428 | 2007 | 4.69 | 0.000376 |

| D14838 | fibroblast growth factor 9 | FGF9 | 27 | 108 | 3.97 | 0.000752 |

| W27899 | member RAS oncogene family | RAB6B | 68 | 232 | 3.43 | 0.00501 |

| U48251 | protein kinase C binding protein 1 | PRKCBP1 | 40 | 127 | 3.18 | 0.001999 |

| U90268 | cerebral cavernous malformations 1 | CCM1 | 53 | 151 | 2.87 | 0.004392 |

| AL050275 | cysteine rich with EGF-like domains | CRELD1 | 195 | 543 | 2.79 | 0.000828 |

| AB014600 | SIN3 homolog B, transcriptional regulator | SIN3B | 177 | 425 | 2.39 | 0.001924 |

| M27691 | cAMP responsive element binding protein 1 | CREB1 | 107 | 229 | 2.15 | 0.003559 |

| U85245 | phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase, type II, beta | PIP5K2B | 244 | 518 | 2.12 | 0.000441 |

| W25793 | ring finger protein 3 | RNF3 | 163 | 326 | 2 | 0.004947 |

| Nucleic Acid Binding | ||||||

| D50912 | RNA binding motif protein 10 | RBM10 | 96 | 443 | 4.6 | 0.001925 |

| U41315 | makorin, ring finger protein, 4 | MKRN4 | 404 | 808 | 2 | 0.000262 |

| Ligand Binding | ||||||

| X67155 | kinesin-like 5 | KIF23 | 64 | 368 | 5.76 | 0.001584 |

| AB028985 | ATP-binding cassette, sub-family A, member 2 | ABC1 | 65 | 262 | 4.04 | 0.001234 |

| Z48482 | matrix metalloproteinase 15 | MMP15 | 139 | 495 | 3.56 | 0.003946 |

| Enzyme | ||||||

| X13794 | lactate dehydrogenase B | LDHB | 396 | 1606 | 4.05 | 0.000845 |

| X15334 | creatine kinase, brain | CKB | 939 | 2083 | 2.22 | 0.002008 |

| X60708 | dipeptidylpeptidase IV | DPP4 | 133 | 291 | 2.19 | 0.000697 |

| AC004381 | SA homolog | SAH | 283 | 599 | 2.11 | 0.000168 |

| AF000416 | exostoses-like 2 | EXTL2 | 134 | 271 | 2.02 | 0.001314 |

| Embryogenesis | ||||||

| U48437 | amyloid beta precursor-like protein 1 | APLP1 | 851 | 2433 | 2.86 | 0.001043 |

| U66406 | ephrin-B3 | EFNB3 | 168 | 438 | 2.6 | 0.00309 |

| D50840 | UDP-glucose ceramide glucosyltransferase | UGCG | 85 | 211 | 2.5 | 0.002554 |

| Other/Unknown | ||||||

| L48215 | hemoglobin, beta | HBB | 12 | 2099 | 178.78 | 0.001299 |

| J00153 | hemoglobin, alpha 1 | HBA1 | 15 | 1249 | 82.25 | 0.001889 |

| U30521 | P311 protein | C5orf13 | 157 | 453 | 2.88 | 0.001431 |

| AB011169 | similar to S. cerevisiae SSM4 | TEB4 | 140 | 300 | 2.15 | 0.00154 |

| AL031432 | GCIP-interacting protein | P29 | 99 | 198 | 2 | 0.002036 |

Table 5.

Genes significantly decreased in tumors.

| GeneBank Accession | Gene Description | Symbol | Normal Mean | Tumor Mean | Fold Change | P value |

| Cell Growth/Division | ||||||

| D17291 | regenerating protein I beta | REG1B | 6286 | 13 | -499.46 | 0.000095 |

| X67318 | carboxypeptidase A1 | CPA1 | 3928 | 121 | -32.57 | 0.003205 |

| AI763065 | regenerating islet-derived 1 alpha | REG1A | 5641 | 334 | -16.88 | 0.000001 |

| D29990 | solute carrier family 7, member 2 | SLC7A2 | 2988 | 445 | -6.72 | 0.002204 |

| AB017430 | kinesin-like 4 | KIFF22 | 1223 | 316 | -3.87 | 0.000177 |

| Z25884 | chloride channel 1 | CLCN1 | 2511 | 655 | -3.84 | 0.00013 |

| X81438 | amphiphysin | AMPH | 2686 | 752 | -3.57 | 0.000002 |

| L03785 | myosin, light polypeptide 5 | MYL5 | 207 | 59 | -3.51 | 0.000233 |

| W28062 | guanine nucleotide-exch. Prot. 2 | ARFGEF2 | 66 | 19 | -3.46 | 0.003602 |

| X52486 | uracil-DNA glycosylase 2 | UNG2 | 2555 | 756 | -3.38 | 0.000514 |

| M81933 | cell division cycle 25A | CDC25A | 312 | 96 | -3.25 | 0.000005 |

| M69136 | chymase 1 | CMA1 | 360 | 115 | -3.13 | 0.004413 |

| U90543 | butyrophilin | BTN2A1 | 685 | 226 | -3.04 | 0.000023 |

| X69086 | utrophin | UTRN | 1325 | 457 | -2.90 | 0.000011 |

| AF039241 | histone deacetylase 5 | HDAC5 | 1124 | 393 | -2.86 | 0.000319 |

| U49392 | allograft inflammatory factor 1 | AIF1 | 165 | 58 | -2.82 | 0.000105 |

| U81992 | pleiomorphic adenoma gene-like 1 | PLAGL1 | 330 | 118 | -2.80 | 0.004717 |

| L26336 | heat shock 70kD protein 2 | HSPA2 | 90 | 32 | -2.79 | 0.000689 |

| F27891 | cytochrome c oxidase subunit VIa | COX6A2 | 872 | 313 | -2.79 | 0.000342 |

| D87673 | heat shock transcription factor 4 | HSF4 | 1964 | 721 | -2.73 | 0.000453 |

| X97795 | RAD54-like | RAD54L | 392 | 144 | -2.72 | 0.001345 |

| X92689 | UDP-N-acetyl-alpha-D-galactosamine | GALNT3 | 80 | 32 | -2.50 | 0.000243 |

| Y08683 | carnitine palmitoyltransferase I | CPT1B | 1038 | 420 | -2.47 | 0.000573 |

| U40622 | X-ray repair complementing defective repair 4 | XRCC4 | 177 | 72 | -2.45 | 0.000678 |

| U64315 | excision repair, complementation group 4 | ERCC4 | 2122 | 868 | -2.44 | 0.000045 |

| AB020337 | beta 1,3-galactosyltransferase | B3GALT5 | 1489 | 635 | -2.34 | 0.002613 |

| U40152 | origin recognition complex | ORC1L | 3671 | 1702 | -2.16 | 0.001425 |

| M10943 | metallothionein 1F | MT1F | 5691 | 2653 | -2.14 | 0.001707 |

| X79882 | major vault protein | MVP | 758 | 376 | -2.02 | 0.001719 |

| AF035960 | transglutaminase 5 | TGM5 | 3097 | 1542 | -2.01 | 0.002951 |

| Cell Death/Apoptosis | ||||||

| S81914 | immediate early response 3 | IER3 | 2209 | 480 | -4.60 | 0.000307 |

| D80007 | programmed cell death 11 | PDCD11 | 457 | 129 | -3.55 | 0.002358 |

| AF013956 | chromobox homolog 4 | CBX4 | 1599 | 492 | -3.25 | 0.00034 |

| U33284 | protein tyrosine kinase 2 beta | PTK2B | 693 | 237 | -2.93 | 0.000763 |

| U90919 | likely partner of ARF1 | APA1 | 2687 | 1021 | -2.63 | 0.000015 |

| X57110 | Cas-Br-M retroviral transforming | CBL | 1889 | 784 | -2.41 | 0.000033 |

| AL050161 | pro-oncosis receptor | PORIMIN | 1178 | 497 | -2.37 | 0.00031 |

| U40380 | presenilin 1 | PSEN1 | 1301 | 569 | -2.29 | 0.00012 |

| D83699 | harakiri, BCL2 interacting protein | HRK | 768 | 338 | -2.27 | 0.001321 |

| U07563 | v-abl viral oncogene homolog 1 | ABL1 | 1415 | 631 | -2.24 | 0.000248 |

| M95712 | v-raf oncogene homolog B1 | BRAF | 338 | 157 | -2.16 | 0.004207 |

| M16441 | lymphotoxin alpha | LTA | 2106 | 985 | -2.14 | 0.000239 |

| AF035444 | pleckstrin homology-like domain, family A, member 2 | PHLDA2 | 334 | 166 | -2.01 | 0.001759 |

Table 6.

Genes significantly decreased in tumors (continued).

| GeneBank Accession | Gene Description | Symbol | Normal Mean | Tumor Mean | Fold Change | P value |

| Signal Transduction | ||||||

| J00306 | somatostatin | SST | 7701 | 284 | -27.09 | 0 |

| AI636761 | somatostatin | SST | 7224 | 598 | -12.09 | 0.000001 |

| AB011143 | GRB2-associated binding protein 2 | GAB2 | 2237 | 402 | -5.57 | 0.001816 |

| M93056 | serine (or cysteine) proteinase inhibitor | SERPINB1 | 505 | 105 | -4.80 | 0.004637 |

| X68830 | islet amyloid polypeptide | IAPP | 2231 | 477 | -4.68 | 0.001221 |

| AB029014 | RAB6 interacting protein 1 | RAB6IP1 | 824 | 181 | -4.56 | 0.000155 |

| AI198311 | neuropeptide Y | NPY | 610 | 154 | -3.96 | 0.004817 |

| M28210 | member RAS oncogene family | RAB3A | 2566 | 672 | -3.82 | 0.000048 |

| J04040 | glucagon | GCG | 8620 | 2351 | -3.67 | 0.000396 |

| AF030335 | purinergic receptor P2Y | P2RY11 | 2314 | 680 | -3.40 | 0.000058 |

| M29335 | major histocompatibility complex | HLA-DOA | 906 | 268 | -3.39 | 0.00159 |

| L38517 | Indian hedgehog homolog | IHH | 3013 | 897 | -3.36 | 0.000055 |

| U95367 | gamma-aminobutyric acid A receptor, pi | GABRP | 668 | 202 | -3.30 | 0.000837 |

| W28558 | pleiotropic regulator 1 | PLRG1 | 704 | 216 | -3.26 | 0.000068 |

| L08485 | gamma-aminobutyric acid A receptor, alpha 5 | GABRA5 | 342 | 107 | -3.20 | 0.000336 |

| AF004231 | leukocyte immunoglobulin-like receptor | LILRB2 | 93 | 30 | -3.08 | 0.001105 |

| AF055033 | insulin-like growth factor binding protein 5 | IGFBP5 | 126 | 43 | -2.96 | 0.000257 |

| AJ010119 | ribosomal protein S6 kinase | RPS6KA4 | 1532 | 522 | -2.94 | 0.000201 |

| U46194 | Human renal cell carcinoma antigen | RAGE | 2057 | 754 | -2.73 | 0.000324 |

| L13858 | son of sevenless homolog 2 | SOS2 | 964 | 354 | -2.72 | 0.000268 |

| Z29572 | tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily | TNFRSF17 | 184 | 68 | -2.69 | 0.000178 |

| U01134 | fms-related tyrosine kinase 1 | FLT1 | 910 | 379 | -2.40 | 0.003257 |

| D78156 | RAS p21 protein activator 2 | RASA2 | 327 | 144 | -2.26 | 0.002332 |

| U77783 | glutamate receptor | GRIN2D | 518 | 240 | -2.15 | 0.001379 |

| D49394 | 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 3A | HTR3A | 197 | 98 | -2.02 | 0.002493 |

| Nucleic Acid Binding | ||||||

| Z30425 | nuclear receptor subfamily 1, group I, member 3 | NR1I3 | 1008 | 356 | -2.83 | 0.000329 |

| U18760 | nuclear factor I/X | NFIX | 5796 | 2216 | -2.62 | 0.000711 |

| AI223140 | purine-rich element binding protein A | PURA | 1137 | 506 | -2.25 | 0.002448 |

| AF015950 | telomerase reverse transcriptase | TERT | 561 | 255 | -2.20 | 0.002839 |

| U40462 | zinc finger protein, subfamily 1A, 1 | ZNFN1A1 | 662 | 308 | -2.15 | 0.001171 |

| Z93930 | X-box binding protein 1 | XBP1 | 2223 | 1061 | -2.09 | 0.000277 |

| AB019410 | PET112-like | PET112A | 1422 | 707 | -2.01 | 0.001309 |

| Ligand Binding | ||||||

| X00129 | retinol binding protein 4, plasma | RBP4 | 1517 | 68 | -22.27 | 0.004809 |

| AJ223317 | sarcosine dehydrogenase | SARDH | 3844 | 1069 | -3.60 | 0.000085 |

| AB017494 | LCAT-like lysophospholipase | LYPLA3 | 906 | 326 | -2.78 | 0.001131 |

| U78735 | ATP-binding cassette, sub-family A, member 3 | ABCA3 | 1914 | 706 | -2.71 | 0.000288 |

| AF026488 | spectrin, beta, non-erythrocytic 2 | SPTBN2 | 1604 | 671 | -2.39 | 0.00005 |

| U83659 | ATP-binding cassette, sub-family C, member 3 | ABCC3 | 1287 | 551 | -2.34 | 0.00244 |

| R93527 | metallothionein 1H | MT1H | 5093 | 2196 | -2.32 | 0.002937 |

| AA586894 | S100 calcium binding protein A7 | S100A7 | 507 | 221 | -2.29 | 0.000537 |

| U91329 | kinesin family member 1C | KIF1C | 2981 | 1484 | -2.01 | 0.000518 |

Table 7.

Genes significantly decreased in tumors (continued).

| GeneChip Accession | Gene Description | Symbol | Normal Mean | Tumor Mean | Fold Change | P value |

| Enzyme | ||||||

| M81057 | carboxypeptidase B1 | CPB1 | 4534 | 79 | -57.09 | 0.001106 |

| X71345 | protease, serine, 4 | PRSS3 | 3859 | 76 | -51.11 | 0.004102 |

| X01683 | serine (or cysteine) proteinase inhibitor, clade A | SERPINA1 | 2550 | 74 | -34.64 | 0.004833 |

| M24400 | chymotrypsinogen B1 | CTRB1 | 5158 | 207 | -24.95 | 0.001744 |

| M18700 | elastase 3A, pancreatic | ELA3A | 7058 | 384 | -18.37 | 0.000009 |

| U66061 | protease, serine, 1 | PRSS1 | 7291 | 645 | -11.31 | 0.000047 |

| L22524 | matrix metalloproteinase 7 | MMP7 | 595 | 54 | -11.03 | 0.002591 |

| AI655458 | 5-oxoprolinase (ATP-hydrolysing) | OPLAH | 446 | 99 | -4.52 | 0.004072 |

| H94881 | FXYD domain-containing ion transport regulator 2 | FXYD2 | 3116 | 708 | -4.40 | 0.000539 |

| AL021026 | flavin containing monooxygenase 2 | FMO2 | 905 | 215 | -4.21 | 0.000804 |

| AC005525 | plasminogen activator, urokinase receptor | PLAUR | 1779 | 566 | -3.14 | 0.000031 |

| U40370 | phosphodiesterase 1A, calmodulin-dependent | PDE1A | 268 | 89 | -3.03 | 0.004023 |

| R90942 | sialyltransferase 7D | SIAT7D | 3148 | 1052 | -2.99 | 0.002319 |

| M84472 | hydroxysteroid (17-beta) dehydrogenase 1 | HSD17B1 | 1196 | 440 | -2.72 | 0.000991 |

| X55988 | ribonuclease, RNase A family, 2 | RNASE2 | 480 | 203 | -2.36 | 0.001314 |

| AB003151 | carbonyl reductase 1 | CBR1 | 4538 | 1945 | -2.33 | 0.000511 |

| X08020 | glutathione S-transferase M1 | GSTM1 | 2766 | 1376 | -2.01 | 0.000519 |

| Embryogenesis | ||||||

| U15979 | delta-like homolog | SIGLEC5 | 3384 | 402 | -8.41 | 0.002927 |

| M60094 | H1 histone family, member T | HIST1H1T | 976 | 230 | -4.23 | 0.001639 |

| U50330 | bone morphogenetic protein 1 | BMP1 | 3298 | 973 | -3.39 | 0.001637 |

| M74297 | homeo box A4 | HOXA4 | 501 | 176 | -2.85 | 0.000477 |

| AJ011785 | sine oculis homeobox homolog 6 | SIX6 | 530 | 190 | -2.79 | 0.000286 |

| U66198 | fibroblast growth factor 13 | FGF13 | 191 | 73 | -2.61 | 0.001068 |

| D31897 | double C2-like domains, alpha | DOC2A | 1151 | 451 | -2.55 | 0.000068 |

| U12472 | glutathione S-transferase pi | GSTP1 | 3122 | 1524 | -2.05 | 0.000237 |

| Transcription | ||||||

| AL049228 | pleckstrin homology domain interacting protein | PHIP | 257 | 33 | -7.69 | 0.000782 |

| M27878 | zinc finger protein 84 | ZNF84 | 54 | 15 | -3.64 | 0.001108 |

| U77629 | achaete-scute complex-like 2 | ASCL2 | 438 | 184 | -2.38 | 0.000058 |

| D50495 | transcription elongation factor A, 2 | TCEA2 | 1330 | 595 | -2.23 | 0.000019 |

| U49857 | transcriptional activator of the c-fos promoter | CROC4 | 542 | 259 | -2.09 | 0.003894 |

Table 8.

Genes significantly decreased in tumors (continued).

| GeneBank Accession | Gene Description | Symbol | Normal Mean | Tumor Mean | Fold Change | P value |

| Other/Undefined | ||||||

| X72475 | immunoglobulin kappa constant | IGKC | 1409 | 276 | -5.11 | 0.000111 |

| D17570 | zona pellucida binding protein | ZPBP | 355 | 71 | -5.02 | 0.001107 |

| M90657 | transmembrane 4 superfamily member 1 | TM4SF1 | 592 | 141 | -4.20 | 0.004537 |

| AF063308 | mitotic spindle coiled-coil related protein | SPAG5 | 2015 | 502 | -4.01 | 0.000588 |

| U66059 | T cell receptor beta locus | TRB@ | 3022 | 779 | -3.88 | 0.000266 |

| AL022165 | carbohydrate sulfotransferase 7 | CHST7 | 359 | 94 | -3.82 | 0.001738 |

| U10694 | melanoma antigen, family A, 9 | MAGEA9 | 1039 | 272 | -3.82 | 0.000067 |

| M73255 | vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 | VCAM1 | 80 | 22 | -3.66 | 0.004179 |

| U47926 | leprecan-like 2 protein | LEPREL2 | 1003 | 319 | -3.15 | 0.00013 |

| L05424 | CD44 antigen | CD44 | 1439 | 471 | -3.05 | 0.001361 |

| AI445461 | transmembrane 4 superfamily member 1 | TM4SF1 | 463 | 161 | -2.88 | 0.002911 |

| AF010310 | proline oxidase homolog | PRODH | 1194 | 421 | -2.84 | 0.000005 |

| AF000991 | testis-specific transcript, Y-linked 2 | TTTY2 | 700 | 254 | -2.76 | 0.000542 |

| X57522 | transporter 1, ATP-binding cassette, sub-family B | TAP1 | 781 | 287 | -2.72 | 0.000971 |

| AA314825 | trefoil factor 1 | TFF1 | 1657 | 616 | -2.69 | 0.000011 |

| AB020880 | squamous cell carcinoma antigen | SART3 | 3228 | 1224 | -2.64 | 0.000135 |

| AF040707 | homologous to yeast nitrogen permease | NPR2L | 1131 | 437 | -2.59 | 0.001537 |

| U47292 | trefoil factor 2 | TFF2 | 359 | 141 | -2.54 | 0.000684 |

| X69398 | CD47 antigen | CD47 | 350 | 144 | -2.42 | 0.000853 |

| U27331 | fucosyltransferase 6 | FUT6 | 1105 | 473 | -2.34 | 0.000872 |

| AI827730 | cyclin M2 | CNNM2 | 5863 | 2535 | -2.31 | 0.000484 |

| U05255 | glycophorin B | GYPB | 1606 | 717 | -2.24 | 0.00013 |

| M34428 | pvt-1 oncogene homolog, MYC activator | PVT1 | 1231 | 550 | -2.24 | 0.004423 |

| U86759 | netrin 2-like | NTN2L | 2039 | 937 | -2.18 | 0.000204 |

| D90278 | CEA-related cell adhesion molecule 3 | CEACAM3 | 4388 | 2024 | -2.17 | 0.000902 |

| L40400 | ZAP3 protein | ZAP3 | 1549 | 719 | -2.15 | 0.000776 |

| U48224 | beaded filament structural protein 2, phakinin | BFSP2 | 568 | 271 | -2.10 | 0.000166 |

| AI138834 | deltex homolog 2 | DTX2 | 311 | 148 | -2.10 | 0.000687 |

| M13755 | interferon-stimulated protein, 15 kDa | G1P2 | 1507 | 741 | -2.03 | 0.001157 |

| X52228 | mucin 1, transmembrane | MUC1 | 1523 | 756 | -2.02 | 0.001707 |

Validation of GeneChip Data with Quantitative RT-PCR

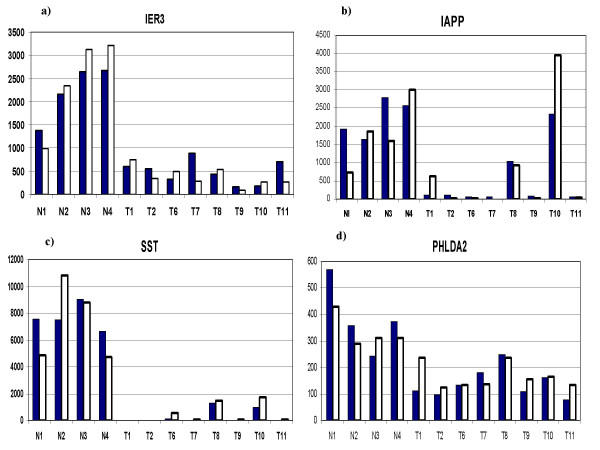

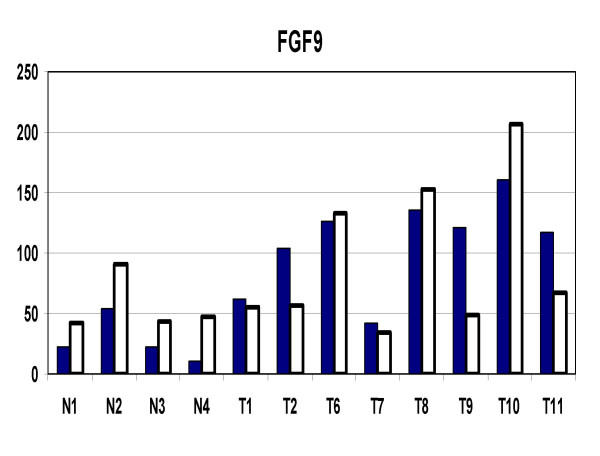

In order to evaluate how accurately the GeneChip data was representing actual gene expression levels, eleven genes were tested with quantitative RT-PCR (Q-PCR). The results are shown in Table 9. The correlation coefficients ranged from 0.964 to 0.235 with an average of 0.655. The lower correlation coefficients were associated with genes with larger numbers of exons. There was some association of low correlation with low average numerical expression values. The lowest correlations were associated with very faint image intensity of the involved genes in the dChip visual representation. The correlation coefficients of 4 genes, identified as apoptosis-related, was examined in detail (Figure 5). IER3, IAPP, SST, and PHLDA2 all had good correlation between GeneChip and Q-PCR results. FGF9, a potential growth stimulating gene was also examined (Figure 6). Again, there was overall good correlation between the individual GeneChip and Q-PCR results.

Table 9.

Correlation of GeneChip expression with quantitative RT-PCR.

| Gene Symbol | Correlation | Probe Set | Exons | Gene Size (bp) | Fold Change (T/N) | P value GeneChip T vs. N |

| IER3 | 0.964 | 1237_at | 1 | 1236 | -4.6 | 0.0000 |

| SST | 0.925 | 37782_at | 2 | 351 | -12 | 0.0000 |

| PHLDA2 | 0.909 | 40237_at | 2 | 913 | -2.01 | 0.0003 |

| REG1B | 0.875 | 35981_at | 6 | 773 | -499 | 0.0000 |

| IAPP | 0.823 | 37871_at | 3 | 1462 | -4.68 | 0.0033 |

| REG1A | 0.814 | 38646_s_at | 6 | 808 | -16.9 | 0.0000 |

| FGF9 | 0.74 | 1616_at | 3 | 1420 | 3.97 | 0.0031 |

| CBLB | 0.327 | 514_at | 21 | 3923 | 3.01 | 0.0009 |

| XPC | 0.318 | 1873_at | 16 | 3658 | 4.38 | 0.0018 |

| HRK | 0.273 | 34011_at | 2 | 716 | -2.27 | 0.0011 |

| PTK2B | 0.235 | 2009_at | 38 | 4715 | -2.94 | 0.0019 |

| Average | 0.655 |

Figure 5.

The expression levels of 4 apoptosis-related genes are shown by GeneChip and quantitative RT-PCR: a) IER3; b) IAPP; c) SST; d) PHLDA2. Normals (N) and tumors (T) are shown. Solid bars represent GeneChip and open bars represent Q-PCR results.

Figure 6.

FGF9 expression levels in tumors (T) and normals (N) by GeneChip and quantitative RT-PCR. Solid bars represent GeneChip and open bars represent Q-PCR results.

Discussion

Whether there were degradative processes acting on the tissues prior to or during or after the extraction of the RNA can be guessed by the quality of the RNA. Each RNA specimen in this study was tested on an Affymetrix test chip, and each was found to be acceptable. Additional quality assessment was made by the dChip software. Only one specimen, a normal control, had Array Outliers greater than 5%, suggesting that it was subnormal (Table 2). However, since the percent outliers was only 5.94, the chip was included in the analysis.

Although, only solid tumor was utilized, there were undoubtedly a small percentage of blood, blood vessel, and connective tissue elements intermixed with the tumor tissue. Rarely, there might be a small amount of exocrine tissue. In the case of the normal islets used as controls, microscopic examination showed that greater than 90% of the tissue was islet. Any contaminants would probably have the effect of reducing the discriminant power to differentiate tumor from normal. Thus, t-test p values and fold changes would tend to under-represented and some, otherwise significant, genes might be missed. The actual data, represented by the hierarchical specimen clustering (Figure 3), showed strong differential gene expression relating to group identity as would be expected if the overall gene expression levels were accurate. All the normals clustered together, separate from all the tumors. Within the normals, the two male specimens clustered in one group, and the two female in another. All the normal islet preparations, which are composed predominantly of beta cells, clustered closer to the insulinoma tumors than to the other neuroendocrine tumor types. The gene clustering results revealed 19 apoptosis-related genes whose expression was suppressed in the islet tumors relative to the normals. This suggests that apoptosis may play a significant role in the development of these tumors.

One might have expected more variation in the gene expression levels in the tumors than in the normal islets, since tumors are often heterogonous. However the data on the average CV of the genes in the normal and tumor groups suggested that there was no more variation in the tumors (average CV of 30%) than in the normals (average CV of 31%). The low CV in the tumors may relate to the single mode of tumor formation (induction by the loss of the menin tumor suppressor). However, there was increased variation noted when the tumors and normals were combined (Figure 2). This was probably the result of the differences in expression between the tumors and the normals.

Of particular interest was the high proportion (3/8) of tumors expressing principally PP hormonal RNA. This was entirely consistent with pathological studies showing the preponderance of PP containing tumors in the pancreas of MEN1 patients [31]. The fact that the clinical classification of two patients (9 and 11) was different than indicated by the hormone expression profile of the tumor analyzed was a consequence of the facts that those patients had multiple tumors secreting multiple hormones but only insulin and gastrin and sometime PP over secretion are likely to result in a clinical diagnosis.

The use of the Students t-test for comparison of multiple genes might be questioned because the test was designed for comparison of only two groups. In this study, we confirmed that comparison of 923 genes would not generate an excess number of false positive results. Nevertheless, in the group of 193 genes finally selected at a p < = .005, we can expect that 1 of those genes is a false positive.

This study suggests that the overall effect of loss of function of menin is the suppression of gene expression. Nevertheless, there were 86 genes that were over-expressed in the tumors relative to the normals. Although we associate tumorigenesis with increased rates of growth, only two of eleven Cell Cycle and Cell Proliferation genes were increased in the tumors. Since tumor growth may also be significantly affected by rates of cell death, it is perhaps significant that there were no Cell Death genes significantly increased in the tumors relative to the controls.

The correlation of GeneChip results with quantitative real-time PCR (Q-PCR, Table 9) was relatively good. However, there were some genes that correlated poorly (correlation coefficient less than 0.6). Interestingly, most of the genes with poor correlation coefficients had a large number of exons, whereas those with high correlation coefficients had a low number of exons. Since exhaustive testing of alternative primer pairs for Q-PCR was not made, it is possible that correlation coefficients of some genes could be improved by the use of other primers.

Four studies of global gene expression in pancreatic islets have been published recently [32-35]. Cardozo et al [32] have used microarrays to look for NF-kB dependent genes in primary cultures of rat pancreatic islets. Shalev et al [33] have measured global gene expression in purified human islets in tissue culture under high and low glucose concentrations. They noted that the TGFβ superfamily member PDF was down regulated 10-fold in the presence of glucose, whereas other TGFβ superfamily members were up regulated. In the current study, none of the TGFβ superfamily members were significantly different between tumor and normal. Scearce et al [34] have used a pancreas-specific micro-chip, the PanChip to analyze gene expression patterns in E14 to adult mice. Only a few specific genes were noted in the paper, and none of them had human homologs of significance to the current study. Maitra et al [35] conducted a study which in many ways was similar to the current one. They compared gene expression, using the Affymetrix U133A chip, in a series of sporadic pancreatic endocrine tumors with isolated normal islets. There was no overlap in the genes they identified (having a three-fold or greater difference in expression) with the genes we identified (having a two-fold or greater difference in expression). This is quite surprising, but perhaps suggests that sporadically arising tumors may have a quite different pattern of gene expression than tumors arising as a result of menin loss or dysfunction. Another possible cause of the differences may be the different Affymetrix GeneChips used in the two studies.

The question of which (if any) of the genes delineated in this study are a direct and necessary affect of loss-of-menin tumorigenesis cannot be determined by this study alone. Firstly, the activity of many genes are regulated both by their levels of expression and by post-translation modifications, such as phosphorylation. Secondly, the microchips used in this study represent only about 1/3 of the total number of human genes. Thirdly, it is not certain that the initiating gene changes caused by loss-of-menin are persistent in the tumors that develop. However, there were some genes, which because of their association with growth or apoptosis are of special interest. The general suppression of apoptosis related genes noted in this study (Figure 4) has been highlighted by the recent study of Schnepp et al, [36] who showed a loss of menin suppression of apoptosis in murine embryonic fibroblasts through a caspase-8 mechanism. Specific apoptosis-related genes which were suppressed in the tumors in the current study, and which were confirmed by Q-PCR include IER3, SST, PHLDA2, and IAPP. IER3 (IEX-1) is regulated by several transcription factors and may have positive or negative effects upon cell growth and apoptosis depending upon the cell-specific context [37]. Several studies have shown that it can be a promoter of apoptosis [38-40]. Somatostatin has shown a wide range of growth inhibitory activity in vitro and in vivo [41-57].PHLDA2 (TSSC3) is an imprinted gene homologous to the murineTDAG51 apoptosis-related gene [58], and may be involved in human brain tumors [59]. IAPP (amylin) is a gene which has contrasting activities and has been associated with experimental diabetes in rodents [60]. Amylin deposits were increased in islets of patients with gastrectomy-induced islet atrophy [61]. On the other hand, exposure of rat embryonic islets to amylin results in beta cell proliferation [62]. In contrast, amylin has been shown to induce apoptosis in rat and human insulinoma cells in vitro [63,64]. In contrast to the suppression of apoptosis-related genes, FGF9 (Figure 6), a growth promoting gene, was significantly increased in the neuroendocrine tumors. This protein has been reported to play roles in glial cell growth [65], chondrocyte growth [66], prostate growth [67], endometrial growth [68], and has been suggested to have a role in human oncogenesis [69].

A recent report by Busygina et al [70] suggested that loss of menin can lead to hypermutability in a Drosophila model for MEN1. The spectrum of mutation sensitivity suggested that there was a defect in nucleotide excision repair. Whether the defect was a direct or indirect effect of menin loss was not stated. In the current study, there was a 2.44-fold decrease, in the tumors, in the expression of ERCC4 (Table 5), a gene involved in nucleotide excision repair. In addition, XRCC4, a gene involved in double-strand break repair, was also decreased in the tumors in the current study.

Conclusion

This first study of global gene expression in neuroendocrine tumors arising in the pancreas of patients with the MEN1 syndrome has identified many genes that are differentially expressed, as compared with normal human islet cells. A number of these genes are strongly over/under expressed and are attractive candidates for further investigation into the mechanisms by which menin loss causes tumors in pancreatic islets. Of particular interest was a group of 24 apoptosis-related genes that were significantly differentially expressed (mostly underexpressed) in the group of neuroendocrine tumors. The underexpression of these apoptosis-related genes may be related to neoplastic development or progression in these MEN1-related neuroendocrine tumors.

Methods

Human Tissue Specimens

Tumor specimens were obtained from patients with the MEN1 syndrome who had undergone surgery for islet-cell tumors of the pancreas. The specific germline mutations in the menin tumor suppressor gene were identified and previously reported [6] for each of the patients. Six of the patients had frame-shift mutations and one had a nonsense mutation. Informed consent was obtained in advance, and tumor tissues not needed for pathological analysis were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and kept frozen at -70° prior to RNA extraction. Normal pancreatic islets (which were originally intended for human transplatation studies, but were not used) were isolated from brain-dead donors by a collagenase procedure, as previously described [71], and were then frozen until used for extraction of RNA. Human Studies Committee approval from Washington University School of Medicine was obtained for this study.

Isolation of RNA from Tissue Specimens

Approximately 50 mg of tissue was removed from each frozen tumor specimen and homogenized with a mortar and pestle (Qiagen, Qiashredder Kit), and RNA was extracted using the Rneasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Inc.), and quantified by UV absorbance. RNA was similarly isolated from the normal human islet preparations.

GeneChip Hybridization and Analysis

The RNA was submitted to the GeneChip facility of the Siteman Cancer Center at Washington University School of Medicine. There, biotin labeled cRNA was prepared and hybridized to U95Av2 microarray chips (Affymetrix). The fluorescence of individual spots was then measured and the data returned on compact discs. We analyzed the gene expression data and made comparisons between groups using the dChip computer program [30]. Following normalization (to equalize the overall intensity of each chip), the expression of each gene was determined by statistical modeling procedure in the dChip software. Each gene was represented by an array of 10 perfect match oligonucleotide spots and 10 mismatch oligonucleotide spots on the U95Av2 chip. The dChip program examines all the spots on all the chips involved in the study, and by a statistical procedure determines single and array outliers. These outliers can be considered as "bad" readings, and removed from further consideration.

Quantitative RT-PCR

The same preparations of total RNA that were used to probe the GeneChips were also used to prepare c-DNA for quantitative RT-PCR analysis of gene expression. C-DNA was first prepared using Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Inc.). Primers for each gene were designed to produce products of 100 to 150 bp that spanned exon boundaries (when possible). The primer pairs are shown in table 10.

Table 10.

| Gene | Forward Primer | Reverse Primer |

| CBLB | cacgtctaaatctatagcagccagaac | tgcactcccaagcctcttctc |

| FGF9 | cggcaccagaaattcacaca | aaattgtctttgtcaactttggcttag |

| HRK | agctggttcccgttttcca | cagtcccattctgtgtttctacgat |

| IAPP | ctgctttgtatccatgagggttt | gaggtttgctgaaagccacttaa |

| ER3 | ccagcatctcaactccgtctgt | caccctaaaggcgacttcaaga |

| SST | cccagactccgtcagtttctg | tacttggccagttcctgcttc |

| PHLDA2 | tgcccattgcaaataaatcact | ctgcccgcccattcct |

| PTK2B | gtgaggagtgcaagaggcagat | gccagattggccagaacct |

| REG1A | cctcaagcacaggattccaga | acatgtattttccagctgcctcta |

| REG1B | gggtccctggtctcctacaagt | catttcttgaatcctgagcatgaa |

| XPC | gcccgcaagctggacat | atcagtcacgggatgggagta |

The Sybr Green technique on an Applied Biosystems model GeneAmp 5700 instrument was utilized. Relative quantitation using a standard c-DNA preparation from an in vitro islet tumor cell line was utilized.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Alvin J. Siteman Cancer Center at Washington University School of Medicine and Barnes-Jewish Hospital in St. Louis, Missouri, for the use of the Multiplexed Gene Analysis Core, which provided the GeneChip processing service. The Siteman Cancer Center is supported in part by an NCI Cancer Center Support Grant #P30 CA91842.

Portions of this work were supported by grant RPG-99-183-01-CCE (TCL) from the American Cancer Society and a Siteman Cancer Center Research Development Award.

Contributor Information

William G Dilley, Email: dilleyb@wustl.edu.

Somasundaram Kalyanaraman, Email: omlimited@hotmail.com.

Sulekha Verma, Email: vermas@slu.edu.

J Perren Cobb, Email: cobb@wustl.edu.

Jason M Laramie, Email: laramiej@bu.edu.

Terry C Lairmore, Email: lairmoret@wustl.edu.

References

- Wermer P. Genetic aspects of adenomatosis of the endocrine glands. Am J Med. 1954;16:363–371. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(54)90353-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx SJ, Agarwal SK, Kester MB, Heppner C, Kim YS, Skarulis MC, James LA, Goldsmith PK, Saggar SK, Park SY, Spiegel AM, Burns AL, Debelenko LV, Zhuang Z, Lubensky IA, Liotta LA, Emmert-Buck MR, Guru SC, Manickam P, Crabtree J, Erdos MR, Collins FS, Chandrasekharappa SC. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1: clinical and genetic features of the hereditary endocrine neoplasias. Recent Prog Horm Res. 1999;54:397–438; discussion 438-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen AGJ. Mutation and Cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1971;68:820–823. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.4.820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekharappa SC, Guru SC, Manickam P, Olufemi SE, Collins FS, Emmert-Buck MR, Debelenko LV, Zhuang Z, Lubensky IA, Liotta LA, Crabtree JS, Wang Y, Roe BA, Weisemann J, Boguski MS, Agarwal SK, Kester MB, Kim YS, Heppner C, Dong Q, Spiegel AM, Burns AL, Marx SJ. Positional cloning of the gene for multiple endocrine neoplasia-type 1. Science. 1997;276:404–407. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5311.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schussheim DH, Skarulis MC, Agarwal SK, Simonds WF, Burns AL, Spiegel AM, Marx SJ. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1: new clinical and basic findings. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2001;12:173–178. doi: 10.1016/S1043-2760(00)00372-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutch MG, Dilley WG, Sanjurjo F, DeBenedetti MK, Doherty GM, Wells SAJ, Goodfellow PJ, Lairmore TC. Germline mutations in the multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 gene: evidence for frequent splicing defects. Hum Mutat. 1999;13:175–185. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1999)13:3<175::AID-HUMU1>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guru SC, Goldsmith PK, Burns AL, Marx SJ, Spiegel AM, Collins FS, Chandrasekharappa SC. Menin, the product of the MEN1 gene, is a nuclear protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:1630–1634. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal SK, Guru SC, Heppner C, Erdos MR, Collins RM, Park SY, Saggar S, Chandrasekharappa SC, Collins FS, Spiegel AM, Marx SJ, Burns AL. Menin interacts with the AP1 transcription factor JunD and represses JunD-activated transcription. Cell. 1999;96:143–152. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80967-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobl AE, Berg M, Lopez-Egido JR, Oberg K, Skogseid B, Westin G. Menin represses JunD-activated transcription by a histone deacetylase-dependent mechanism. Biochim Biophy Acta. 1999;1447:51–56. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(99)00132-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal SK, Novotny EA, Crabtree JS, Weitzman JB, Yaniv M, Burns AL, Chandrasekharappa SC, Collins FS, Spiegel AM, Marx SJ. Transcription factor JunD, deprived of menin, switches from growth suppressor to growth promoter. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:10770–10775. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1834524100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thepot D, Weitzman JB, Barra J, Segretain D, Stinnakre MG, Babinet C, Yaniv M. Targeted disruption of the murine junD gene results in multiple defects in male reproductive function. Development. 2000;127:143–153. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.1.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart C, Parente F, Piehl F, Farnebo F, Quincey D, Silins G, Bergman L, Carle GF, Lemmens I, Grimmond S, Xian CZ, Khodei S, Teh BT, Lagercrantz J, Siggers P, Calender A, Van de Vem V, Kas K, Weber G, Hayward N, Gaudray P, Larsson C. Characterization of the mouse Men1 gene and its expression during development. Oncogene. 1998;17:2485–2493. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemmens IH, Forsberg L, Pannett AA, Meyen E, Piehl F, Turner JJ, Van de Ven WJ, Thakker RV, Larsson C, Kas K. Menin interacts directly with the homeobox-containing protein Pem. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;286:426–431. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandi ML, Weber G, Svensson A, Falchetti A, Tonelli F, Castello R, Furlani L, Scappaticci S, Fraccaro M, Larsson C. Homozygotes for the autosomal dominant neoplasia syndrome (MEN1) Am J Hum Genet. 1993;53:1167–1172. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaji H, Canaff L, Lebrun JJ, Goltzman D, Hendy GN. Inactivation of menin, a Smad3-interacting protein, blocks transforming growth factor type beta signaling. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:3837–3842. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061358098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heppner C, Bilimoria KY, Agarwal SK, Kester M, Whitty LJ, Guru SC, Chandrasekharappa SC, Collins FS, Spiegel AM, Marx SJ, Burns AL. The tumor suppressor protein menin interacts with NF-kappaB proteins and inhibits NF-kappaB-mediated transactivation. Oncogene. 2001;20:4917–4925. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkura N, Kishi M, Tsukada T, Yamaguchi K. Menin, a gene product responsible for multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1, interacts with the putative tumor metastasis suppressor nm23. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;282:1206–1210. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberati NT, Datto MB, Frederick JP, Shen X, Wong C, Rougier-Chapman EM, Wang XF. Smads bind directly to the Jun family of AP-1 transcription factors. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:4844–4849. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.4844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Rovira T, Chalaux E, Rosa JL, Bartrons R, Ventura F. Interaction and functional cooperation of NF-kappa B with Smads. Transcriptional regulation of the junB promoter. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:28937–28946. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M909923199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitzer M, von Gersdorff G, Liang D, Dominguez-Rosales A, Beg AA, Rojkind M, Bottinger EP. A mechanism of suppression of TGF-beta/SMAD signaling by NF-kappa B/RelA. Genes Dev. 2000;14:187–197. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahmani M, Peron P, Weitzman J, Bakiri L, Lardeux B, Bernuau D. Functional cooperation between JunD and NF-kappaB in rat hepatocytes. Oncogene. 2001;20:5132–5142. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alon U, Barkai N, Notterman DA, Gish K, Ybarra S, Mack D, Levine AJ. Broad patterns of gene expression revealed by clustering analysis of tumor and normal colon tissues probed by oligonucleotide arrays. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:6745–6750. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub TR, Slonim DK, Tamayo P, Huard C, Gaasenbeek M, Mesirov JP, Coller H, Loh ML, Downing JR, Caligiuri MA, Bloomfield CD, Lander ES. Molecular classification of cancer: class discovery and class prediction by gene expression monitoring. Science. 1999;286:531–537. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5439.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alizadeh AA, Ross DT, Perou CM, van de Rijn M. Towards a novel classification of human malignancies based on gene expression patterns. J Pathol. 2001;195:41–52. doi: 10.1002/path.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su AI, Welsh JB, Sapinoso LM, Kern SG, Dimitrov P, Lapp H, Schultz PG, Powell SM, Moskaluk CA, Frierson HFJ, Hampton GM. Molecular classification of human carcinomas by use of gene expression signatures. Cancer Res. 2001;61:7388–7393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramaswamy S, Tamayo P, Rifkin R, Mukherjee S, Yeang CH, Angelo M, Ladd C, Reich M, Latulippe E, Mesirov JP, Poggio T, Gerald W, Loda M, Lander ES, Golub TR. Multiclass cancer diagnosis using tumor gene expression signatures. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:15149–15154. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211566398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu TD. Analysing gene expression data from DNA microarrays to identify candidate genes. J Pathol. 2001;195:53–65. doi: 10.1002/1096-9896(200109)195:1<53::AID-PATH891>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkin DP. Uncovering functionally relevant signaling pathways using microarray-based expression profiling. Oncologist. 2000;5:501–507. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.5-6-501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Hung Wong W. Model-based analysis of oligonucleotide arrays: model validation, design issues and standard error application. Genome Biol. 2001;2:RESEARCH0032. doi: 10.1186/gb-2001-2-8-research0032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Wong WH. Model-based analysis of oligonucleotide arrays: expression index computation and outlier detection. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:31–36. doi: 10.1073/pnas.011404098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komminoth P, Heitz PU, Kloppel G. Pathology of MEN-1: morphology, clinicopathologic correlations and tumour development. J Intern Med. 1998;243:455–464. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1998.00274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardozo AK, Heimberg H, Heremans Y, Leeman R, Kutlu B, Kruhoffer M, Orntoft T, Eizirik DL. A comprehensive analysis of cytokine-induced and nuclear factor-kappa B-dependent genes in primary rat pancreatic beta-cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:48879–48886. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108658200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalev A, Pise-Masison CA, Radonovich M, Hoffmann SC, Hirshberg B, Brady JN, Harlan DM. Oligonucleotide microarray analysis of intact human pancreatic islets: identification of glucose-responsive genes and a highly regulated TGFbeta signaling pathway. Endocrinology. 2002;143:3695–3698. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scearce LM, Brestelli JE, McWeeney SK, Lee CS, Mazzarelli J, Pinney DF, Pizarro A, Stoeckert CJJ, Clifton SW, Permutt MA, Brown J, Melton DA, Kaestner KH. Functional genomics of the endocrine pancreas: the pancreas clone set and PancChip, new resources for diabetes research. Diabetes. 2002;51:1997–2004. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.7.1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maitra A, Hansel DE, Argani P, Ashfaq R, Rahman A, Naji A, Deng S, Geradts J, Hawthorne L, House MG, Yeo CJ. Global expression analysis of well-differentiated pancreatic endocrine neoplasms using oligonucleotide microarrays. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:5988–5995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnepp RW, Mao H, Sykes SM, Zong WX, Silva A, La P, Hua X. Menin induces apoptosis in murine embryonic fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:10685–10691. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308073200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu MX. Roles of the stress-induced gene IEX-1 in regulation of cell death and oncogenesis. Apoptosis. 2003;8:11–18. doi: 10.1023/A:1021688600370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arlt A, Grobe O, Sieke A, Kruse ML, Folsch UR, Schmidt WE, Schafer H. Expression of the NF-kappa B target gene IEX-1 (p22/PRG1) does not prevent cell death but instead triggers apoptosis in Hela cells. Oncogene. 2001;20:69–76. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilling D, Pittelkow MR, Kumar R. IEX-1, an immediate early gene, increases the rate of apoptosis in keratinocytes. Oncogene. 2001;20:7992–7997. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osawa Y, Nagaki M, Banno Y, Brenner DA, Nozawa Y, Moriwaki H, Nakashima S. Expression of the NF-kappa B target gene X-ray-inducible immediate early response factor-1 short enhances TNF-alpha-induced hepatocyte apoptosis by inhibiting Akt activation. J Immunol. 2003;170:4053–4060. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.8.4053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albini A, Florio T, Giunciuglio D, Masiello L, Carlone S, Corsaro A, Thellung S, Cai T, Noonan DM, Schettini G. Somatostatin controls Kaposi's sarcoma tumor growth through inhibition of angiogenesis. FASEB Journal. 1999;13:647–655. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.6.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold R, Wied M, Behr TH. Somatostatin analogues in the treatment of endocrine tumors of the gastrointestinal tract. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2002;3:643–656. doi: 10.1517/14656566.3.6.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benali N, Cordelier P, Calise D, Pages P, Rochaix P, Nagy A, Esteve JP, Pour PM, Schally AV, Vaysse N, Susini C, Buscail L. Inhibition of growth and metastatic progression of pancreatic carcinoma in hamster after somatostatin receptor subtype 2 (sst2) gene expression and administration of cytotoxic somatostatin analog AN-238. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:9180–9185. doi: 10.1073/pnas.130196697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgstrom P, Hassan M, Wassberg E, Refai E, Jonsson C, Larsson SA, Jacobsson H, Kogner P. The somatostatin analogue octreotide inhibits neuroblastoma growth in vivo. Pediatr Res. 1999;46:328–332. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199909000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatzistamou I, Schally AV, Varga JL, Groot K, Armatis P, Busto R, Halmos G. Antagonists of growth hormone-releasing hormone and somatostatin analog RC-160 inhibit the growth of the OV-1063 human epithelial ovarian cancer cell line xenografted into nude mice. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:2144–2152. doi: 10.1210/jc.86.5.2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florio T, Morini M, Villa V, Arena S, Corsaro A, Thellung S, Culler MD, Pfeffer U, Noonan DM, Schettini G, Albini A. Somatostatin inhibits tumor angiogenesis and growth via somatostatin receptor-3-mediated regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase and mitogen-activated protein kinase activities. Endocrinology. 2003;144:1574–1584. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgii-Hemming P, Stromberg T, Janson ET, Stridsberg M, Wiklund HJ, Nilsson K. The somatostatin analog octreotide inhibits growth of interleukin-6 (IL-6)-dependent and IL-6-independent human multiple myeloma cell lines. Blood. 1999;93:1724–1731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoelting T, Duh QY, Clark OH, Herfarth C. Somatostatin analog octreotide inhibits the growth of differentiated thyroid cancer cells in vitro, but not in vivo. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:2638–2641. doi: 10.1210/jc.81.7.2638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara S, Hassan S, Kinoshita Y, Moriyama N, Fukuda R, Maekawa T, Okada A, Chiba T. Growth inhibitory effects of somatostatin on human leukemia cell lines mediated by somatostatin receptor subtype 1. Peptides. 1999;20:313–318. doi: 10.1016/S0196-9781(99)00037-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jungwirth A, Schally AV, Halmos G, Groot K, Szepeshazi K, Pinski J, Armatis P. Inhibition of the growth of Caki-I human renal adenocarcinoma in vivo by luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone antagonist Cetrorelix, somatostatin analog RC-160, and bombesin antagonist RC-3940-II. Cancer. 1998;82:909–917. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19980301)82:5<909::AID-CNCR16>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahan Z, Nagy A, Schally AV, Hebert F, Sun B, Groot K, Halmos G. Inhibition of growth of MX-1, MCF-7-MIII and MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer xenografts after administration of a targeted cytotoxic analog of somatostatin, AN-238. Int J Cancer. 1999;82:592–598. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19990812)82:4<592::AID-IJC20>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiaris H, Schally AV, Nagy A, Szepeshazi K, Hebert F, Halmos G. A targeted cytotoxic somatostatin (SST) analogue, AN-238, inhibits the growth of H-69 small-cell lung carcinoma (SCLC) and H-157 non-SCLC in nude mice. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37:620–628. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(00)00437-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikutsuji T, Harada M, Tashiro S, Ii S, Moritani M, Yamaoka T, Itakura M. Expression of somatostatin receptor subtypes and growth inhibition in human exocrine pancreatic cancers. J Heptobiliary Pancreat Surgery. 2000;7:496–503. doi: 10.1007/s005340070021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krenning EP, Valkema R, Kooij PP, Breeman WA, Bakker WH, de Herder WW, van Eijck CH, Kwekkeboom DJ, de Jong M, Jamar F, Pauwels S. The role of radioactive somatostatin and its analogues in the control of tumor growth. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2000;153:1–13. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-59587-5_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishima M, Yano T, Jimbo H, Yano N, Morita Y, Yoshikawa H, Schally AV, Taketani Y. Inhibition of human endometrial cancer cell growth in vitro and in vivo by somatostatin analog RC-160. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181:583–590. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70496-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinski J, Schally AV, Halmos G, Szepeshazi K, Groot K. Somatostatin analog RC-160 inhibits the growth of human osteosarcomas in nude mice. Int J Cancer. 1996;65:870–874. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19960315)65:6<870::AID-IJC27>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zatelli MC, Tagliati F, Piccin D, Taylor JE, Culler MD, Bondanelli M, degli Uberti EC. Somatostatin receptor subtype 1-selective activation reduces cell growth and calcitonin secretion in a human medullary thyroid carcinoma cell line. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;297:828–834. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)02307-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MP, Feinberg AP. Genomic imprinting of a human apoptosis gene homologue, TSSC3. Cancer Res. 1998;58:1052–1056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller S, van den Boom D, Zirkel D, Koster H, Berthold F, Schwab M, Westphal M, Zumkeller W. Retention of imprinting of the human apoptosis-related gene TSSC3 in human brain tumors. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:757–763. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.5.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebre-Medhin S, Olofsson C, Mulder H. Islet amyloid polypeptide in the islets of Langerhans: friend or foe? Diabetologia. 2000;43:687–695. doi: 10.1007/s001250051364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh H, Takei K. Immunohistochemical and statistical studies on the islets of Langerhans pancreas in autopsied patients after gastrectomy. Hum Pathol. 2000;31:1368–1376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson E, Sandler S. Islet amyloid polypeptide promotes beta-cell proliferation in neonatal rat pancreatic islets. Diabetologia. 2001;44:1015–1018. doi: 10.1007/s001250100601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumora L, Hadzija M, Barisic K, Maysinger D, Grubiic TZ. Amylin-induced cytotoxicity is associated with activation of caspase-3 and MAP kinases. Biol Chem. 2002;383:1751–1758. doi: 10.1515/BC.2002.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Liu J, MacGibbon G, Dragunow M, Cooper GJ. Increased expression and activation of c-Jun contributes to human amylin-induced apoptosis in pancreatic islet beta-cells. J Mol Biol. 2002;324:271–285. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)01044-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyagi N, Kato S, Terasaki M, Aoki T, Sugita Y, Yamaguchi M, Shigemori M, Morimatsu M. Fibroblast growth factor-9 (glia-activating factor) stimulates proliferation and production of glial fibrillary acidic protein in human gliomas either in the presence or in the absence of the endogenous growth factor expression. Oncol Rep. 1999;6:87–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weksler NB, Lunstrum GP, Reid ES, Horton WA. Differential effects of fibroblast growth factor (FGF) 9 and FGF2 on proliferation, differentiation and terminal differentiation of chondrocytic cells in vitro. Biochem J. 1999;342:677–682. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3420677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giri D, Ropiquet F, Ittmann M. FGF9 is an autocrine and paracrine prostatic growth factor expressed by prostatic stromal cells. J Cellr Physiol. 1999;180:53–60. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199907)180:1<53::AID-JCP6>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai SJ, Wu MH, Chen HM, Chuang PC, Wing LY. Fibroblast growth factor-9 is an endometrial stromal growth factor. Endocrinology. 2002;143:2715–2721. doi: 10.1210/en.143.7.2715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto-Yoshitomi S, Habashita J, Nomura C, Kuroshima K, Kurokawa T. Autocrine transformation by fibroblast growth factor 9 (FGF-9) and its possible participation in human oncogenesis. Int J Cancer. 1997;71:442–450. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19970502)71:3<442::AID-IJC23>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busygina V, Suphapeetiporn K, Marek LR, Stowers RS, Xu T, Bale AE. Hypermutability in a Drosophila model for multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:2399–2408. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olack BJ, Swanson CJ, Howard TK, Mohanakumar T. Improved method for the isolation and purification of human islets of langerhans using Liberase enzyme blend. Human Immunol. 1999;60:1303–1309. doi: 10.1016/S0198-8859(99)00118-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]