Abstract

Efficient conversion of glucose to acetaldehyde is achieved by nisin-controlled overexpression of Zymomonas mobilis pyruvate decarboxylase (pdc) and Lactococcus lactis NADH oxidase (nox) in L. lactis. In resting cells, almost 50% of the glucose consumed could be redirected towards acetaldehyde by combined overexpression of pdc and nox under anaerobic conditions.

Acetaldehyde is an important aroma compound in dairy products. It is considered the most important aroma compound in yoghurt. In yoghurt fermentation, both Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophilus have been found to produce acetaldehyde (28, 32). In bacteria, acetaldehyde can be derived from amino acid, nucleotide, and pyruvate metabolism (6). In lactic acid bacteria, overproduction of amino acid-derived acetaldehyde has been achieved by overproduction of threonine aldolase (GlyA) in S. thermophilus (6). A thymidine synthase (thyA) deletion strain of Lactococcus lactis produces slightly more nucleotide metabolism-derived acetaldehyde than the parental strain (29), while a d-lactate dehydrogenase (Ldh)-deficient strain of Lactobacillus johnsonii showed a marginal increase in pyruvate-derived acetaldehyde production (22).

In lactococcal carbon metabolism, pyruvate can be converted to acetyl coenzyme A by pyruvate formate lyase (Pfl) or pyruvate dehydrogenase (Pdh) (16). Subsequently, acetyl coenzyme A can be converted to acetaldehyde by aldehyde dehydrogenase (Adh). Furthermore, acetate can potentially be converted to acetaldehyde as part of the acetate utilization rescue pathway (12). However, although several biochemical pathways for acetaldehyde production are described, acetaldehyde is hardly produced as a fermentation end product in L. lactis.

Here we describe the efficient rerouting of pyruvate towards acetaldehyde in L. lactis by functional expression of pyruvate decarboxylase (pdc), originating from the gram-negative ethanologenic bacterium Zymomonas mobilis. In this organism Pdc catalyzes the conversion of pyruvate to acetaldehyde, which is subsequently reduced to ethanol by alcohol dehydrogenase (35). In addition to this heterologous pdc gene, the endogenous NADH oxidase (nox) gene is overexpressed. Nox overproduction is known to decrease lactate production by NADH-dependent Ldh under aerobic conditions (24), leading to increased pyruvate availability for alternative reactions. Moreover, the quantitative model of pyruvate distribution in L. lactis (10; jjj.biochem.sun.ac.za/wcfs.html) predicts that overexpression of Nox leads to a reduction in the conversion of acetaldehyde to ethanol by the NADH-dependent alcohol dehydrogenase as a result of the lower NADH/NAD+ ratio.

Overproduction of pyruvate decarboxylase and NADH oxidase in L. lactis.

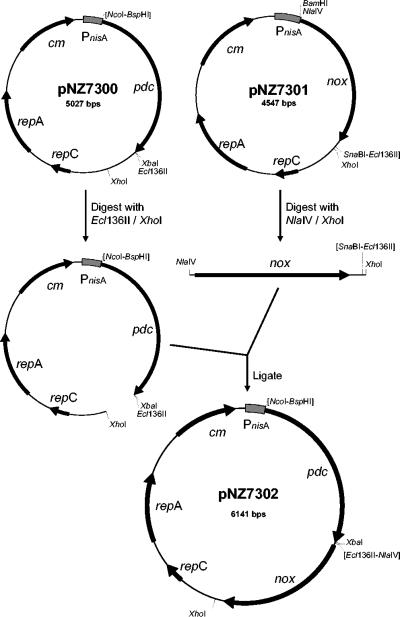

All plasmid constructions were performed using Escherichia coli MC1061 (5) as an intermediate host. DNA isolations and manipulations were performed according to established methods (31). The Zymononas mobilis pyruvate decarboxylase gene was amplified by PCR, using PdcF (5′-AGTCTCATGAGTTATACTGTCGGTACCTA-3′) and PdcR (5′-AGTCTCTAGAAACTAGAGGAGCTTGTTAAC-3′) as primers and pGIT510 (8) as the template. The 1.7-kb amplicon was digested with BspHI and XbaI (whose recognition sites are indicated in boldface in the primer sequences above) and cloned under the control of the nisA promoter in NcoI-XbaI-digested pNZ8048 (19), yielding pNZ7300 (Fig. 1). A plasmid for overproduction of lactococcal Nox was constructed by transcriptional fusion to the nisA promoter. To this end, the lactococcal nox gene, including its predicted ribosome binding site, was amplified by PCR, using noxtcF (5′-GCTAGGATCCTAAAGGAGACCTATTAGTATGAAAATCG-3′) and noxtcR (5′-CTAACTTTCTATACGTAAAGTTTGAGC-3′) as primers and chromosomal DNA of L. lactis MG1363 as the template. The 1.4-kb amplicon was digested with BamHI and SnaBI and cloned in BamHI-Ecl136II-digested pNZ8020 (7), generating pNZ7301 (Fig. 1). For combined overexpression of both pdc and nox, the nox-containing 1.5-kb NlaIV-XhoI fragment of pNZ7301 was subcloned into Ecl136II-XhoI-digested pNZ7300, yielding pNZ7302 (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of plasmid constructions for nisin-controlled overexpression of Pdc (pNZ7300), Nox (pNZ7301), and Pdc and Nox (pNZ7302). The nisA promoter is indicated by a grey box, and genes are indicated by arrows. Ligation sites of two compatible cohesive ends or blunt-ended DNA fragments that cannot be digested by either of the two original enzymes used are indicated by the enzyme names in brackets.

Overnight cultures of L. lactis NZ9000 (a pepN::nisRK derivative of MG1363) (19) harboring plasmid pNZ7300, pNZ7301, or pNZ7302 were grown at 30°C in M17 broth (Oxoid, Basingstoke, England) supplemented with 0.5% (wt/vol) glucose and 10 μg of chloramphenicol per ml to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.5. Cultures were split in portions of 50 ml, and expression of pdc and/or nox was induced by the addition of 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, or 1.0 ng of nisin per ml (7). Growth was continued for another 2 h, and cells were harvested by centrifugation (15 min, 10,000 × g, 4°C), washed once in a 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) for Nox quantifications or in a 100 mM Tris malate buffer (pH 6.0) for Pdc quantification, and resuspended in 1 ml of the same buffer. Cell extracts were prepared by bead beating (24), and total protein quantification was performed using the method described by Bradford (3).

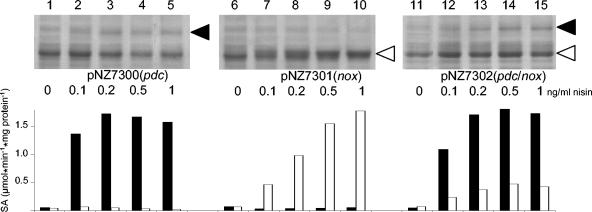

Overproduction of Nox and Pdc proteins was visualized by Coomassie blue-stained sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (21). This analysis showed additional protein bands of approximately 61 and 50 kDa upon nisin-induced overproduction of Pdc and Nox (Fig. 2), respectively, which is in good agreement with the predicted molecular masses of these proteins (60.5 and 48.9 kDa, respectively) (4).

FIG. 2.

Nisin-controlled overexpression of pdc and nox in L. lactis NZ9000. Shown are the results of sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of crude cell extracts of L. lactis NZ9000 harboring plasmids pNZ7300, pNZ7301, and pNZ7302 that were not induced (lanes 1, 6, and 11) and induced with 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, and 1.0 ng of nisin per ml (lanes 2 to 5, 7 to 10, and 12 to 15, respectively). Pdc- and Nox-representing protein bands are indicated by filled and open arrowheads, respectively. Specific activities (SA) of Pdc (filled bars) and Nox (open bars) are shown.

NADH oxidase activity in the cell extracts was determined as described previously (24). To determine the pyruvate decarboxylase activity, 100 μl of 10-fold-diluted cell extract was incubated with 30 mM pyruvate in a 100 mM Tris-malate buffer (pH 6.0) in a total reaction volume of 1.2 ml. After incubation for 6 min at 30°C, the reaction was stopped by adding 200 μl of 35% (wt/vol) perchloroacetic acid. Subsequently, the pH was adjusted to 9.0 by adding 350 μl of 1 M potassium pyrophosphate and 180 μl of 10 M potassium hydroxide, precipitated potassium-perchloroacetic acid was removed by centrifugation (1 min at 14,000 × g), and acetaldehyde concentrations were determined using an enzymatic assay according to the manufacturer's protocol (R-Biopharm, Darmstadt, Germany). Specific activities of Nox and Pdc are given as micromoles per minute per milligram of protein.

The enzyme activity measurements (Fig. 2) showed that in contrast to the Nox overproduction characteristics, the Pdc overproduction levels did not display the typical linear dose-response curve for the range of nisin concentrations used (7). In addition, overproduction of Nox appeared to be reduced when it was produced in combination with Pdc, relative to overproduction of Nox alone. Nonetheless, these measurements clearly establish the functional overproduction of Pdc and/or Nox in L. lactis NZ9000.

Analysis of metabolites produced by pdc- and/or nox-overexpressing L. lactis.

Initially, to evaluate the possible toxicity of the pyruvate decarboxylase product (acetaldehyde) for L. lactis, the MIC (35 ± 4 mM) and the concentration that generates a 50% growth rate reduction relative to the growth of a noninhibited culture (9 ± 1 mM) for this metabolite were determined using previously described procedures (20; data not shown). Based on these data and the notion that the central carbon metabolism and growth are largely uncoupled in L. lactis (13), the metabolic impact of Nox and/or Pdc overproduction was evaluated in a two-step fermentation in which the growth and enzyme production phase is separated from the metabolite production phase by resting cell fermentations (11, 14). To this end, L. lactis NZ9000 derivatives that harbor pNZ7300, pNZ7301, pNZ7302, or pNZ8020 were grown at 30°C under aerobic (100 ml of culture in a 500-ml flask, shaken at 200 rpm) or anaerobic (100 ml of static culture) conditions. At an OD600 of 0.5, overexpression of the pdc and/or nox gene was induced by adding 1 ng of nisin per ml. Following induction, growth was continued for 2 h under the same conditions. Subsequently, cells were harvested by centrifugation (15 min, 10,000 × g, 4°C), washed twice with ice-cold 50 mM potassium-sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0), and resuspended in the same buffer containing 50 mM glucose at a final OD600 of 10. Cell suspensions were incubated at 30°C and shaken in air at 200 rpm when aerobic conditions were applied. When anaerobic conditions were applied, cell pellets were washed and resuspended in the same buffers in an anaerobic hood, and fermentations were performed at 30°C in airtight, anaerobic vessels that were shaken at 200 rpm. After 2 h of incubation, cells were removed by centrifugation (5 min, 14,000 × g) and glucose and acetaldehyde concentrations were determined in the supernatants by enzymatic assays, according to the manufacturer's protocols (R-Biopharm). Lactate, formate, acetate, acetoin, butanediol, ethanol, and pyruvate levels were determined by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) as described previously (33). Relative metabolite production levels given correspond to 10 mM glucose consumed (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Fermentation characteristics of NADH oxidase (nox) and pyruvate decarboxylase (pdc)-overexpressing L. lactis strains

| Overexpression of genea

|

Aerobic conditionsb | Concn (mmol/liter) of indicated product formed per 10 mM glucose consumedc

|

Recovery (%)d | Theoretical NADH excess (%)e | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pdc | nox | Lactate | Formate | Acetate | Acetoin | Butanediol | Ethanol | Pyruvate | Acetaldehyde | ||||

| − | − | + | 16.7 (83.7) | ND | 1.5 (7.4) | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.1 (0.5) | 92 | 16 | |

| − | + | + | 2.3 (11.3) | ND | 1.4 (7.2) | 7.4 (73.7) | ND | ND | ND | 0.1 (0.3) | 93 | 89 | |

| + | − | + | 9.1 (45.4) | ND | 0.5 (2.4) | ND | ND | 0.7 (3.5) | ND | 5.5 (27.5) | 79 | 33 | |

| + | + | + | 2.9 (14.7) | ND | 0.9 (4.6) | 2.6 (26.1) | ND | 0.3 (1.3) | ND | 3.9 (19.7) | 67 | 55 | |

| − | − | − | 14.5 (72.4) | ND | 0.4 (2.0) | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 75 | 4 | |

| − | + | − | 4.2 (21.0) | ND | 1.4 (7.1) | 4.8 (47.6) | ND | ND | ND | ND | 76 | 62 | |

| + | − | − | 8.4 (41.8) | ND | 0.2 (0.9) | ND | ND | 2.8 (13.9) | ND | 4.2 (20.8) | 78 | 23 | |

| + | + | − | 3.2 (16.2) | ND | 0.3 (1.6) | ND | ND | 0.7 (3.4) | ND | 9.5 (47.4) | 69 | 51 | |

Gene products are overexpressed by the addition of nisin. +, overexpressed; −, not overexpressed.

+, both preculture and fermentation conditions were in the presence of oxygen; −, preculture and initial fermentation conditions were microaerobic.

Values in parentheses are percentages of pyruvate converted into the product. ND, not detected.

Carbon recovery is calculated based on detected metabolites.

Theoretical excess NADH has been calculated assuming that 10 mM glucose has been converted to 20 mM pyruvate, yielding 20 mM NADH. For each end product, the stoichiometric NADH consumption or production if produced from pyruvate has been calculated. The recovery of the various end products has been multiplied by this factor. It has to be noted that under aerobic conditions, there is no genuine NADH excess, because NADH can be oxidized by Nox.

The main fermentation products produced by L. lactis NZ9000 under aerobic conditions are lactate and acetate, while overproduction of Nox in this strain results in a clear decrease of lactate production and an increase of acetoin production (Table 1). This determination is in good agreement with previous observations (10, 23) and can be completely explained in terms of redox balance and pyruvate affinity constants of the enzymes involved (10). Upon Pdc overproduction, approximately a fourth of the glucose consumed is converted to acetaldehyde at the expense of lactate formation, corroborating the idea that Pdc (the Km for pyruvate is 0.3 mM [26]) can effectively compete with Ldh (the Km for pyruvate is 1.15 mM [9]) for the available pyruvate. Only a small amount of ethanol is formed under these conditions by the reduction of acetaldehyde to ethanol, catalyzed by the endogenous alcohol dehydrogenase (Adh), which generally has only a limited activity in L. lactis (10). Upon combined overproduction of Pdc and Nox, the reduction of lactate production is comparable to that observed upon overproduction of Nox alone. Moreover, acetoin production in these cells was strongly reduced relative to that in cells that overproduce Nox alone, which is caused by the low relative affinity of Als for pyruvate (the Km is 50 mM [10]) compared with that of Pdc, thereby explaining the effective rerouting of pyruvate towards acetaldehyde at the expense of acetoin production. However, the acetaldehyde production level appeared to be slightly lower than that of cells overproducing Pdc alone, while ethanol production was inhibited by Nox overexpression, which can be explained by the reduced NADH concentration. Remarkably, the observed carbon recoveries for various fermentations, including that of the wild type, appeared relatively low compared to what has been found in other studies (Table 1) (12, 14). This apparent discrepancy is possibly due to the accumulation of experimental errors in the analysis methods used. Alternatively, other metabolic end products, which were not measured here, may have been produced by these cells. However, neither wide-range organic acid and alcohol (33) nor sugar and polyol HPLC analyses (including mannitol [27] and sorbitol [15]) (18) revealed unidentified peaks that could correspond to such an alternative metabolite. In this respect, it is noteworthy that a significant negative correlation (P = 0.006) was found between acetaldehyde concentration and total carbon recovery using Pearson's product moment correlation coefficient (R2 = 0.48) (34), assuming that the data came from a bivariate normal distribution. This correlation might be due to the volatile nature of acetaldehyde, resulting in underestimation of the production level of this metabolite and partially explain some of the relatively low carbon recovery results.

As expected, the wild-type strain (NZ9000) produced mainly lactate under anaerobic conditions (2, 30). Formate production was not detected, which suggests that Pfl is irreversibly inactivated by the exposure to oxygen during preparation of the incubation mixtures (1, 17, 25). Pdc overproduction under these conditions led to an effective rerouting of the pyruvate metabolism towards acetaldehyde and ethanol. The relatively high ethanol production level probably reflects the high NADH/NAD+ ratio as a consequence of the reduced flux through the NADH-dependent Ldh pathway and favors the conversion of acetaldehyde to ethanol by NADH-dependent Adh. This conclusion is supported by calculations of the redox balance based on glucose consumption and metabolites found (Table 1). Highly remarkable results were obtained for the Nox-overproducing cells under anaerobic conditions. These cells displayed a metabolic shift from lactate towards acetoin and acetate that almost equals that observed for the same strain under aerobic conditions. Despite our efforts, the possibility of the presence of residual amounts of oxygen at the start of these fermentations cannot be excluded. However, these amounts would be far from sufficient to serve as the electron acceptor for the Nox reaction, which suggests that an alternative, unidentified compound might act as electron acceptor for the lactococcal Nox enzyme under anaerobic conditions. This possibility is clearly apparent from the observation that especially upon overproduction of Nox under anaerobic conditions, the calculated NADH/NAD+ balance suggests a very high metabolic excess of NADH, which supports the possibility of the presence of an alternative electron sink under these conditions. Notably, Nox activity and, consequently, the presence of an alternative electron acceptor under anaerobic conditions have been observed previously (M. H. N. Hoefnagel, unpublished observation; A. R. Neves, personal communication). Finally, wild-type cells containing high levels of Nox and Pdc can convert glucose to acetaldehyde with very high efficiency, which corresponded to almost 50% of the glucose consumed. Notably, the production of acetoin appeared to be entirely lost in these cells compared to that in cells overproducing Nox alone. Analogously to what was concluded above, the very low production levels of lactate and ethanol observed with Nox- and Pdc-overproducing cells under anaerobic conditions suggest that the NADH/NAD+ ratio is very low under these conditions. Theoretically, a high metabolic NADH excess is calculated again and thus confirms that the Nox enzyme can effectively regenerate NAD+ from NADH despite the absence of molecular oxygen. Consequently, the distribution of the available pyruvate between the Pdc and Ldh pathways is strongly favored towards NADH-independent Pdc, resulting in high-level production of acetaldehyde. Moreover, and as stated above, the volatile nature of acetaldehyde probably results in an underestimation of the level produced, which is corroborated by the carbon recovery levels observed during these fermentations, which appeared to be the lowest of all fermentations performed. The concentration of acetaldehyde produced in this fermentation (21.3 mM) is the highest produced in this study, exceeding the concentration that would severely inhibit the growth of L. lactis (see above), and thereby supports its application in a two-step fermentation process in a manner analogous to what is described here.

In conclusion, in addition to the previously established suitability of L. lactis as a production host for alanine (11) and diacetyl (14), our acetaldehyde production results provide a third example of the suitability of this bacterial host for the production of metabolites that are derived from its central metabolic intermediate pyruvate in an industrially relevant two-step fermentation process. Moreover, industrially relevant production conditions were found to be most effective for the production of the important flavor compound acetaldehyde.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Roelie Holleman for technical assistance in the HPLC metabolite analysis. We thank Thierry Ferain and Pascal Hols for providing pGIT510 and for fruitful discussion and Jeroen Hugenholtz for critically reading the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arnau, J., F. Jorgensen, S. M. Madsen, A. Vrang, and H. Israelsen. 1997. Cloning, expression, and characterization of the Lactococcus lactis pfl gene, encoding pyruvate formate-lyase. J. Bacteriol. 179:5884-5891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bongers, R. S., M. H. N. Hoefnagel, M. J. C. Starrenburg, M. A. J. Siemerink, J. G. A. Arends, J. Hugenholtz, and M. Kleerebezem. 2003. IS981-mediated adaptive evolution recovers lactate production by ldhB transcription activation in a lactate dehydrogenase-deficient strain of Lactococcus lactis. J. Bacteriol. 185:4499-4507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradford, M. M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantification of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:52-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bringer-Meyer, S., K. L. Schminz, and H. Sahm. 1986. Pyruvate decarboxylase from Zymomonas mobilis. Isolation and partial characterization. Arch. Microbiol. 146:105-110. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casabadan, M. J., and S. N. Cohen. 1980. Analysis of gene control signals by DNA fusion and cloning in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 138:179-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaves, A. C. S. D., M. Fernandez, A. L. S. Lerayer, I. Mierau, M. Kleerebezem, and J. Hugenholtz. 2002. Metabolic engineering of acetaldehyde production by Streptococcus thermophilus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:5656-5662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Ruyter, P. G. G. A., O. P. Kuipers, and W. M. de Vos. 1996. Controlled gene expression systems for Lactococcus lactis with the food-grade inducer nisin. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:3662-3667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferain, T., A. N. Schanck, J. Hugenholtz, P. Hols, W. M. de Vos, and J. Delcour. 1998. Redistribution métabolique chez une souche de Lactobacillus plantarum déficiente en lactate déshydrogénase. Lait 78:107-116. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hillier, A. J., and G. R. Jago. 1982. l-Lactate dehydrogenase, FDP-activated, from Streptococcus cremoris. Methods Enzymol. 89:362-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoefnagel, M. H. N., M. J. C. Starrenburg, D. E. Martens, J. Hugenholtz, M. Kleerebezem, I. I. van Swam, R. S. Bongers, H. V. Westerhoff, and J. L. Snoep. 2002. Metabolic engineering of lactic acid bacteria, the combined approach: kinetic modelling, metabolic control and experimental analysis. Microbiology 148:1003-1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hols, P., M. Kleerebezem, A. N. Schanck, T. Ferain, J. Hugenholtz, J. Delcour, and W. M. de Vos. 1999. Conversion of Lactococcus lactis from homolactic to homoalanine fermentation through metabolic engineering. Nat. Biotechnol. 17:588-592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hols, P., A. Ramos, J. Hugenholtz, J. Delcour, W. M. de Vos, H. Santos, and M. Kleerebezem. 1999. Acetate utilization in Lactococcus lactis deficient in lactate dehydrogenase: a rescue pathway for maintaining redox balance. J. Bacteriol. 181:5521-5526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hugenholtz, J., and M. Kleerebezem. 1999. Metabolic engineering of lactic acid bacteria: overview of the approaches and results of pathway rerouting involved in food fermentations. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 10:492-497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hugenholtz, J., M. Kleerebezem, M. Starrenburg, J. Delcour, W. de Vos, and P. Hols. 2000. Lactococcus lactis as a cell factory for high-level diacetyl production. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:4112-4114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hugenholtz, J., and E. J. Smid. 2002. Nutraceutical production with food-grade microorganisms. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 13:497-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hugenholtz, J., W. Sybesma, M. Nierop-Groot, W. Wisselink, V. Ladero, K. Burgess, D. van Sinderen, J. C. Piard, G. Eggink, E. J. Smid, G. Savoy, F. Sesma, T. Jansen, P. Hols, and M. Kleerebezem. 2002. Metabolic engineering of lactic acid bacteria for the production of nutraceuticals. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 82:217-235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jensen, N. B. S., C. R. Melchiorsen, K. V. Jokumsen, and J. Villadsen. 2001. Metabolic behavior of Lactococcus lactis MG1363 in microaerobic continuous cultivation at a low dilution rate. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:2677-2682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koops, J., and C. Olieman. 1985. Routine testing of farm milk with the Milko-Scan 203. 3. Comparative evaluation of polarimetry, HPLC, enzymatic assay and reductometry for the determination of lactose. Calibration for infra-red analysis of lactose. Calculation of total solids from infra-red measurements. Netherlands Milk Dairy J. 39:89-106. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuipers, O. P., P. G. G. A. de Ruyter, M. Kleerebezem, and W. M. de Vos. 1997. Controlled overproduction of proteins by lactic acid bacteria. Trends Biotechnol. 15:135-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuipers, O. P., H. S. Rollema, W. M. G. J. Yap, H. J. Boot, R. J. Siezen, and W. M. de Vos. 1992. Engineering dehydrated amino acid residues in the antimicrobial peptide nisin. J. Biol. Chem. 267:24340-24346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lapierre, L., J. E. Germond, A. Ott, M. Delley, and B. Mollet. 1999. d-Lactate dehydrogenase gene (ldhD) inactivation and resulting metabolic effects in the Lactobacillus johnsonii strains La1 and N312. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:4002-4007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lopez de Felipe, F., M. Kleerebezem, W. M. de Vos, and J. Hugenholtz. 1998. Cofactor engineering: a novel approach to metabolic engineering in Lactococcus lactis by controlled expression of NADH oxidase. J. Bacteriol. 180:3804-3808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lopez de Felipe, F., M. J. C. Starrenburg, and J. Hugenholtz. 1997. The role of NADH-oxidase in acetoin and diacetyl production from glucose in Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis MG1363. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 156:15-19. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Melchiorsen, C. R., K. V. Jokumsen, J. Villadsen, M. G. Johnsen, H. Israelsen, and J. Arnau. 2000. Synthesis and posttranslational regulation of pyruvate formate-lyase in Lactococcus lactis. J. Bacteriol. 182:4783-4788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neale, A. D., R. K. Scopes, R. E. Wettenhall, and N. J. Hoogenraad. 1987. Pyruvate decarboxylase of Zymomonas mobilis: isolation, properties, and genetic expression in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 169:1024-1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neves, A. R., A. Ramos, C. Shearman, M. J. Gasson, J. S. Almeida, and H. Santos. 2000. Metabolic characterization of Lactococcus lactis deficient in lactate dehydrogenase using in vivo 13C-NMR. Eur. J. Biochem. 267:3859-3868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ott, A., J. E. Germond, M. Baumgartner, and A. Chaintreau. 1999. Aroma comparisons of traditional and mild yogurts: headspace gas chromatography quantification of volatiles and origin of α-diketones. J. Agric. Food Chem. 47:2379-2385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pedersen, M. B., P. R. Jensen, T. Janzen, and D. Nilsson. 2002. Bacteriophage resistance of a ΔthyA mutant of Lactococcus lactis blocked in DNA replication. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:3010-3023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Platteeuw, C., J. Hugenholtz, M. Starrenburg, I. van Alen-Boerrigter, and W. M. de Vos. 1995. Metabolic engineering of Lactococcus lactis: influence of the overproduction of α-acetolactate synthase in strains deficient in lactate dehydrogenase as a function of culture conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:3967-3971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 32.Schirch, V., S. Hopkins, E. Villar, and S. Angelaccio. 1985. Serine hydroxymethyltransferase from Escherichia coli: purification and properties. J. Bacteriol. 163:1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Starrenburg, M. J. C., and J. Hugenholtz. 1991. Citrate fermentation by Lactococcus and Leuconostoc subsp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 57:3535-3540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamane, T. 1973. Statistics. An introductory analysis, 3rd ed. Harper & Row Publishers Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 35.Zhang, M., C. Eddy, K. Deanda, M. Finkelstein, and S. Picataggio. 1995. Metabolic engineering of a pentose phosphate pathway in ethanologenic Zymomonas mobilis. Science 267:240-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]