Abstract

Estrogen receptors (ER) are ligand-dependent transcription factors that regulate growth, differentiation, and maintenance of cellular functions in a wide variety of tissues. We report here that p21WAF1/CIP1, a cyclin-dependent kinase (Cdk) inhibitor, cooperates with CBP to regulate the ERα-mediated transcription of endogenous target genes in a promoter-specific manner. The estrogen-induced expression of the progesterone receptor and WISP-2 mRNA transcripts in MCF-7 cells was enhanced by p21WAF1/CIP1, whereas that of the cyclin D1 mRNA was reduced and the pS2 mRNA was not affected. Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays revealed that p21WAF1/CIP1 was recruited simultaneously with ERα and CBP to the endogenous progesterone receptor gene promoter in an estrogen-dependent manner. Experiments in which the p21WAF1/CIP1 protein was knocked down by RNA interference showed that the induction of the expression of the gene encoding the progesterone receptor required p21WAF1/CIP1, in contrast with that of the cyclin D1 and pS2 genes. p21WAF1/CIP1 induced not only cell cycle arrest in breast cancer cells but also milk fat globule protein and lipid droplets, indicators of the differentiated phenotype, as well as cell flattening and increase of the volume of the cytoplasm. These results indicate that p21WAF1/CIP1, in addition to its Cdk-regulatory role, behaves as a transcriptional coactivator in a gene-specific manner implicated in cell differentiation.

Estrogens act through binding to their receptor proteins (ER), members of the steroid/thyroid nuclear receptor superfamily (38). Two isoforms of ER have been identified, ERα and ERβ (NR3A1 and NR3A2; Nuclear Receptors Nomenclature Committee, 1999), with overlapping but distinct roles in mediating estrogen action as a function of cell context and promoters (14). Both ERs have highly homologous ligand-binding and DNA-binding domains and two similar activation function sites (43) that are important in interactions with nuclear coactivators (1) and corepressors (29, 34, 64). For regulation of gene transcription, ERα has to interact with basal transcription factors and RNA polymerase II (7, 28, 60, 72). The binding of the hormone to the receptor induces a conformational change in the hormone-binding domain (6). This conformational change allows ER to bind to coactivators, such as the p160/SRC family, the cointegrators p300/CBP, and the p300/CBP-associated factor p/CAF, which enhance its transactivation potential (57). These coactivators function as bridging proteins for the components of the basal transcriptional machinery and/or as histone acetyltransferases that help to overcome the repressive effect of chromatin structure on transcription (57). In addition, p160/SRC coactivators recruit protein arginine methyltransferases, such as CARM1 or PRMT1 (39). These secondary coactivators act synergistically with the p160/SRC coactivators to enhance ER function. Transcriptional coactivators have been shown to stimulate the activities of many transcription factors involved in multiple and sometimes opposite cellular activities (57). The association of coactivator proteins with transcription factors involved in both cell proliferation and differentiation can be regulated by diverse signals from mitogens or differentiation-inducing stimuli.

Estrogens are decisive actors responsible for the proliferation and differentiation of normal mammary epithelial cells as well as the development and progression of breast cancer (16, 32, 44). They act in early G1 phase of the cell cycle (65, 71), the time window in which the cell commits to proliferation or differentiation. Normal cell growth is dependent on the tightly regulated activation of cyclin-cyclin-dependent kinase (Cdk) complexes (63). The activities of Cdks are controlled in part by the synthesis and proteolysis of cyclins and through the interaction with two classes of Cdk inhibitors (CdkI), which bind to and inactivate cyclin-Cdk complexes (24). The first class of CdkI includes the INK proteins, which target Cdk4 and Cdk6 and inhibit their binding to cyclins. The second class of CdkI is composed of the CIP/KIP proteins, p21WAF1/CIP1, p27KIP1, and p57KIP2, which bind to and inhibit all cyclin-Cdk complexes. Recently, several studies have reported that p21WAF1/CIP1 (hereafter referred to as p21) might have additional roles. It has been proposed that p21 plays a positive role in the commitment to differentiate, since this protein is up-regulated in the early stage of differentiation (22, 35). In this regard, p21 induced by MyoD has been reported to promote myogenic differentiation (37). A similar mechanism has been proposed for retinoic acid-induced F9 differentiation (30). Conversely, the inhibition of p21 expression in G0-arrested cells can induce DNA synthesis and cell cycle progression (42). Several recent studies report that p21 can also regulate transcription. The fact that p21 lacks DNA-binding motifs and detectable affinity for DNA suggests that p21 may function as a transcriptional cofactor. For example, p21 acts as a negative modulator of E2F, c-Myc, and STAT3 transcriptional activities (10, 15, 31), whereas it enhances the transcriptional activities of C/EBP and NF-kB, two transcriptional factors implied in cell growth and differentiation (25, 47). We have recently demonstrated that the expression of p21, along with the inhibition of Cdk2 activity and cell cycle arrest, stimulates transcriptional activation by ERα through a CBP-histone acetyltransferase (HAT) activity-dependent mechanism (54).

In the present study we provide evidence that p21 functions as a regulator of ER transcriptional activity and discuss its possible roles in cell- and gene-specific regulation of estrogen-dependent transcription.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

MCF-7, ZR-75.1, T47D, and MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells and HeLa cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). The MCF-7 tet-off-p21 cell line (E15), harboring conditional expression of hemagglutinin-tagged p21 (HA-p21), was cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, G418 (400 μg/ml), hygromycin B (100 μg/ml), and doxycycline (DOX) (2 μg/ml). To induce the expression of HA-p21, cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and maintained in media lacking DOX for various time periods.

Plasmids.

The p21 and p27 expression constructs were provided by B. Ducommun and N. Rivard. The p21 coding sequence was cloned into the pTRE-HA vector (Clontech) between the HindIII and XbaI sites. The expression plasmid pRc/RSV-CBP was a gift from R. H. Goodman. The full-length human ERα cDNA was cloned into EcoRI sites of pGEX-3X (Amersham-Pharmacia). Small interfering RNA (siRNA) oligonucleotides for p21 were designed by using the Target Finder program (Ambion). The following sequences were used to construct small RNA interference vectors in pSUPER (5): p21-siRNA225, 5′-CTTCGACTTTGTCACCGAGTT-3′; and p21-siRNA400, 5′-GACCATGTGGACCTGTCACTT-3′. The scrambled sequence was 5′-AGTACGTGTACATGCGCCCTT-3′. TranSilent human control siRNA vector and TranSilent human CBP siRNA vector were from Panomics.

Generation of the E15 cell line.

MCF-7-tTA cells (75) were trypsinized, centrifuged, and resuspended in cytomix buffer (68) containing 20 μg of pTRE-HA-p21 and 1 μg of pTK-hygro. The total amount of DNA was adjusted to 40 μg per transfection with salmon sperm DNA. Cell suspension (5 × 106 cells) in 500 μl was transferred to a 0.4-cm-electroporation-gap cuvette (Bio-Rad) and pulsed with a gene pulser apparatus (960 μF, 250 V). Cell suspensions (450 μl) were plated in 10-cm petri dishes in medium containing 10% FBS for 48 h and then selected in medium containing 400 μg of G418/ml, 100 μg of hygromycin B/ml, and 2 μg of DOX/ml. Several individual clones were isolated. Each clone was cultured in the presence or absence of DOX and analyzed for the inducibility of p21 by Western blot analysis using anti-p21 antibody. The clone E15 was selected for further study, since it displayed the strongest induction of the exogenous p21 in the absence of DOX and no background expression with 2 μg of DOX/ml.

Transient transfection.

For the promoter activity assays, cells were placed for 24 h in medium without phenol red containing 10% dextran-charcoal-stripped serum. Transfections were performed using the FuGene 6 transfection reagent (Roche Molecular Biochemicals). For siRNA experiments, MCF-7 cells were grown to 70 to 80% confluency and trypsinized, and 5 × 106 cells were centrifuged and resuspended in 500 μl of cytomix buffer. Cell suspension was added to 0.4-cm electroporation-gap cuvettes containing plasmids and 20 μg of sheared salmon sperm DNA and electroporated by using a gene pulser apparatus (960 μF, 250 V). Cell suspensions (100 μl) were plated in 3.5-cm petri dishes in medium without phenol red containing 10% dextran-charcoal-stripped serum. After overnight incubation, cells were treated with 10 nM estradiol or vehicle and harvested 24 h later for the determination of luciferase and β-galactosidase activities (54).

GST pull-down.

Glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins or GST alone was expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 and bound to glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads (Amersham Pharmacia). In vitro-translated [35S]methionine-labeled proteins produced by using the TNT-Quick coupled transcription-translation system (Promega) were incubated for 4 h with GST fusion proteins bound to beads in NTEN buffer as described previously (60). Bound proteins were analyzed by fluorography.

Immunoblots, immunoprecipitation, and reimmunoprecipitation.

For immunoblots, 50 μg of protein from cell lysate was fractionated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and probed with antibodies. Enhanced-chemiluminescence reagents were used for the signal detection. For immunoprecipitation experiments, MCF-7 cells were maintained in phenol red-free medium supplemented with 10% dextran-charcoal-stripped FBS for 48 h and then treated with 10 nM estradiol or vehicle for 2 h. Nuclear extracts were prepared as previously described (3). Nuclear extract (500 μg of protein) was incubated with the anti-CBP antibody or control normal rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) overnight at 4°C on a rotator, followed by addition of protein G-Sepharose beads for 1 h at 4°C. Beads were washed three times with 1 ml of lysis buffer and boiled for 5 min in Laemmli sample buffer. The immunoprecipitates were subjected to SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotting analyses were performed with antibodies against ERα, CBP, and p21 as described previously (54). For reimmunoprecipitation, immunocomplexes were eluted from the primary immunoprecipitation by incubation with 10 mM dithiothreitol at 37°C for 30 min and diluted 1/10 in buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% NP-40) before being reimmunoprecipitated with the second antibody. Reimmunoprecipitation of supernatants was carried out in a manner similar to that of the primary immunoprecipitation. Nuclear extracts equivalent to 1/10 of the input for each immunoprecipitation were also analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies against ERα, CBP, and p21. The antibodies used were as follows: anti-HA Y11, anti-actin I-19, and anti-CBP A22 from Santa-Cruz Biotechnology, anti-p21 SX-118 from Pharmingen, anti-ERα Ab-15 and anti-PR Ab-8 from NeoMarkers, and anti-cyclin D1 from Clontech; anti-pS2 was a gift from M. C. Rio.

Reverse transcription-quantitative real-time PCR (RT-QPCR).

Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy mini-kit (QIAGEN) with DNase I treatment according to the manufacturer's instructions. Two micrograms of total RNA was subjected to reverse transcription by using random primers (Invitrogen) for 50 min at 42°C. Two microliters of RT product was diluted (1:10) and subjected to quantitative PCR, using sequence-specific primers (300 nM) and Brilliant SYBR GREEN QPCR master mix on an Mx3000P apparatus (Stratagene). Primers for amplification of target genes were as follows: pS2 (TFF1), upper, 5′-GCCCAGACAGAGACGTGTACAGT-3′; lower, 5′-CTGGAGGGACGTCGATGGTATTAG-3′; PR, upper, 5′-ACAGGACCCCTCCGACGAAAA-3′; lower, 5′-AGCTGTCTCCAACCTTGCACC-3′; transforming growth factor alpha, upper, 5′-CTGGGTATTGTGTTGGCTGCGT-3′; lower, 5′-CACTCACAGTGTTTTCGGACCT-3′; c-Myc, upper, 5′-GG CGCCCAGCGAGGATATCT-3′; lower, 5′-AAGCTGGAGGTGGAGCAGACG-3′; c-Jun, upper, 5′-CTCCAAGTGCCGAAAAAGGAAG-3′; lower, 5′-CACCTGTTCCCTGAGCATGTTG-3′; stanniocalcin 2, upper, 5′-GAATGTTTCGAGAACAACTCTT-3′; lower, 5′-TCTTTGATGAATGACTTGCC-3′; WISP-2, upper, 5′-CATGCAGAACACCA ATATTAAC-3′; lower, 5′-TAGGCAGTGAGTTAGAGGAAAG-3′; cathepsin D, upper, 5′-GCACAAGTTCACGTCCAT-3′; lower, 5′-AGTACTTTGAGACGGGGC-3′; cyclin D1, upper, 5′-TCCAGAGTGATCAAGTGTGA-3′; lower, 5′-GATGTCCACGTCCCGCACGT-3′; p21WAF1, upper, 5′-ACCCTAGTTCTACCTCAGGC-3′; lower, 5′-AAGATCTACTCCCCCATCAT-3′; 36B4, upper, 5′-GATTGGCTACCCAACTGTTG-3′; lower, 5′-CAGGGGCAGCAGCCACAAA-3′.

Thermocycling conditions were as follows: 1 cycle at 95°C for 10 min and 40 cycles at 95°C for 30 s, 60°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 30 s. The threshold was set above the nontemplate control background and within the linear phase of target gene amplification to calculate the cycle number at which the transcript was detected. Gene expression values were calculated based on the comparative ΔCT method (50) and normalized to the housekeeping gene 36B4.

ChIP assays.

MCF-7 cells were grown in phenol red-free DMEM supplemented with 5% dextran-charcoal-stripped serum in 100-mm dishes for 3 days and then treated with or without 100 nM estradiol for 45 min. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were performed largely as described previously (73). A small portion of the cross-linked, sheared chromatin solution (1%) was saved as input DNA, and the remainder was used for immunoprecipitation with anti-ERα antibody (AER-311; Upstate), anti-p21 antibody (SX118; Pharmingen), and anti-CBP antibody (A-22; Santa Cruz). Immunoprecipitated DNA was deproteinized by phenol-chloroform extraction, precipitated by ethanol, and resuspended in 30 μl of buffer. PCR amplifications were performed with 2 μl of DNA, using 35 cycles. PCR products were run on 2% agarose gels and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. Quantitative real-time PCR amplifications of promoters were performed with 2 μl of DNA as described in the preceding section. The following primer pairs were used: PR promoter region, −125 to +187, upper, 5′-TAACGGGTGGAAATGCCAACT-3′; lower, 5′-TCTGCTGGCTCCGTACTGCGG-3′; PR promoter region, +352 to +616, upper, 5′-GCCGTCGCAGCCGCAGCCACT-3′; lower, 5′-ATCTCCACCTCCTGGGTCGGG-3′; pS2 promoter (region −353 to −30), upper, 5′-GGCCATCTCTCACTATGAATCACTTCTGC-3′; lower, 5′-GGCAGGCTCTGTTTGCTTAAAGAGCG-3′; cyclin D1 promoter (region −43 to +12), upper, 5′-TAACAACAGTAACGTCACACG-3′; lower, 5′-GACTTTGCAACTTCAACAAAACT-3′.

Flow cytometry analysis of the cell cycle.

Analysis of the cell cycle was performed by flow-cytometric quantitation of nuclear DNA contents after propidium iodide staining. Cells were trypsinized, washed in PBS, and fixed in 70% ethanol. For analysis, they were suspended in PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100, treated with RNase (1 μg/ml) and propidium iodide (20 μg/ml) for 30 min at room temperature, and analyzed with a FACSCAN flow cytometer.

Microscopic imaging.

E15 cells were plated on 6-cm dishes and grown for 48 h in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS in the presence or absence of 2 μg of DOX/ml. The parental MCF-7 cells were grown in medium containing 10% FBS. Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde-PBS and then treated briefly with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS. After three rinses with PBS, cells were incubated with fluorescein phalloidin (1:200 dilution of a 5-μg/0.1 ml solution; Sigma) in the dark for 40 min at room temperature, rinsed, and incubated for 5 min at room temperature with the fluorescent lipid stain Nile red (1:2,000 dilution of a 1-mg/ml acetone solution; Sigma) (19, 67). Alternatively, cells were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with primary antibodies to cytokeratin 18 (Sigma), to HA-epitope Y11 (Santa-Cruz Biotechnology), or to milk fat globule proteins (MFG) (Chemicon), rinsed, and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with Texas Red-conjugated secondary antibody (goat anti-mouse IgG; Jackson) or fluorescein-conjugated secondary antibody (goat anti-rabbit IgG; Jackson). Nuclei were stained with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) at a concentration of 1 μg/ml. All dishes were rinsed in PBS and mounted with Fluoromount-G containing 2.5% N-propylgalate. Images were obtained with a Leica DMR microscope equipped with a fluorescence imaging system (×63 objective).

RESULTS

The transcriptional effect of p21 varies according to the cell line.

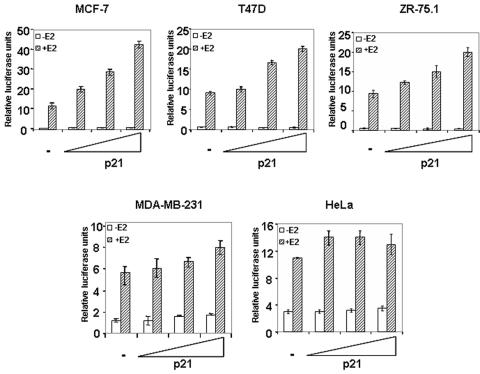

We recently demonstrated that increased expression of p21 led to an increased transcriptional activity of ERα in a CBP/p300 HAT-dependent manner in MCF-7 cells (54). We report here similar experiments carried out with three additional human breast cancer cell lines exhibiting distinct differentiation phenotypes and with the HeLa cell line that exhibit a poorly differentiated phenotype. The selected cell lines can be classified from a more to a less differentiated phenotype as follows: MCF-7, ZR-75.1, T47D, MDA-MB-231, and HeLa (11, 40, 66). Importantly, MCF-7, T47D, and ZR75.1 cells are ERα positive, in contrast with the MDA-MB-231 and HeLa cells. Experiments carried out with T47D and ZR-75.1 cells showed that p21 increased the activity of ERα in the presence of estradiol in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1). However, the transcriptional activation in both these cell lines was weaker than in the MCF-7 cells. A weak effect was observed in the MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 1). In the HeLa cells, p21 did not enhance the estradiol-induced ERα transcriptional activity (Fig. 1). We verified that exogenous p21 was expressed at comparable levels in all these cell lines (data not shown). These data show that the enhancement of transcriptional activity of ERα by p21 is not a general phenomenon and may be related to the type and degree of cell differentiation.

FIG. 1.

The transcriptional effect of p21 varies according to the cell line. Cells were transfected with increasing amounts (0.5, 1, or 2 μg) of pCMV-p21 along with 0.5 μg of ERE-tk-luc and 0.1 μg of a β-galactosidase construct as an internal control. In the ERα-negative cells, MDA-MB-231 and HeLa cells, the transfection mix included 0.1 μg of pSG5-hERα. After overnight incubation, cells were treated with 10 nM estradiol (+E2) or vehicle (−E2) and harvested 24 h later. Extracts were assayed for luciferase and β-galactosidase activities. Luciferase activity was normalized to β-galactosidase activity. The results are shown as means ± standard errors from at least three separate experiments.

p21 enhances CBP-mediated ERα transactivation.

Since p21 belongs to the CIP/KIP family of Cdk inhibitors, we examined whether the expression of the related p27KIP1 may also play a role in estrogen signaling. Figure 2A shows that cotransfection of p27KIP1, expressed at levels similar to that of p21 (data not shown), enhanced the estradiol-induced ERα transcriptional activity but to a lesser extent than with p21 even at the highest concentration used. The ability of p27KIP1 to arrest cell proliferation in MCF-7 cells was examined by the cyclin A-luciferase assay (17). As with p21, the expression of p27KIP1 down-regulated the luciferase activity (data not shown). These results confirm that ERα transcriptional activity is stimulated by proteins that inhibit phosphorylation by Cdks (54). However, the greater efficiency of p21 in stimulating ERα transcriptional activity cannot be accounted for simply by the inhibition of the kinase activity.

FIG. 2.

ERα interacts with p21 and CBP. (A) MCF-7 cells were transfected with increasing amounts (0.5, 1, or 2 μg) of pCMV-p21 or pCMV-p27, 1 μg of pRSV-CBP alone or in combination with 1 μg of pCMV-p21, or 1 μg of pCMV-p27 along with 0.5 μg of ERE-tk-luc and 0.1 μg of a β-galactosidase construct as an internal control. (B) MCF-7 cells were electroporated with 20 μg of pCMV-p21 or TranSilent human CBP-siRNA vector alone or in combination with 2 μg of ERE-tk-luc. Total lysates of the control or siRNA-transfected cells were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting for CBP and β-actin. For panels A and B, after overnight incubation, cells were treated with 10 nM estradiol (+E2) or vehicle (−E2) and harvested 24 h later. Extracts were assayed for luciferase and β-galactosidase activities. Luciferase activity was normalized to β-galactosidase activity except for panel B, where all luciferase values were normalized to protein concentration. The data are means ± ranges of duplicates and illustrate one of three experiments which all gave similar results. (C) Equal amounts of 35S-labeled p21 or p27 were incubated with bacterially expressed GST or GST-ERα fusion constructs immobilized on glutathione-Sepharose beads. Following incubation at 4°C for 2 h, complexes were washed five times with binding buffer, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and detected by fluorography. As a control, 10% of the 35S-labeled protein used in the experiment was analyzed in parallel (Input). (D) MCF-7 cells were maintained in phenol red-free medium supplemented with 10% dextran-charcoal-stripped serum for 48 h and then grown in medium with or without 10 nM estradiol for 2 h. For immunoprecipitations, 500 μg of nuclear extract was incubated with the anti-CBP antibody or control normal rabbit IgG (lanes 3 to 5). After incubation with 10 mM dithiothreitol at 37°C for 30 min, the supernatant was collected and reimmunoprecipitated with antibodies against p21 or control normal mouse IgG (lanes 6 to 8). The immunoprecipitates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. A portion of the nuclear extracts was also analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies against ERα, CBP, and p21 (Input) (lanes 1, 2).

To obtain insight into the molecular mechanism by which p21 and CBP increase the transcriptional activation mediated by ERα, we determined the effect of CBP on this transactivation by transfection-based assays. Transfection of CBP did not significantly alter the hormone response (Fig. 2A), probably reflecting the fact that endogenous CBP was not limiting for transcriptional activation by endogenous ERα in the MCF-7 cell line (9). The transactivation was enhanced ∼3.5-fold with the highest concentration of p21 used compared to that with the control vector. When p21 and CBP were transfected simultaneously, the gene expression was further increased (∼6.5 times the control level; Fig. 2A). In contrast, the transfection of p27KIP1 together with CBP did not significantly alter the response obtained with p27KIP1 alone (Fig. 2A). To complete the above data, we analyzed the effect of p21 expression when endogenous CBP was silenced. We used the TranSilent siRNA vector to produce an siRNA duplex to specifically target CBP expression. As a control, we used the same vector expressing a siRNA duplex which does not anneal to any mRNA. Lysates of MCF-7 cells transfected with these vectors were tested for the expression of CBP and β-actin. CBP expression level was efficiently decreased in the lysates of MCF-7 cells, whereas the β-actin level was not affected (Fig. 2B). As expected, a reduced level of CBP decreased the transcriptional activity of ERα and abolished the effect of p21 expression on ERα transactivation (Fig. 2B). These results showed a synergistic effect of CBP and p21 in the ERα coactivation.

p21 associates with CBP and ERα.

Although several mechanisms for the synergistic enhancement of ERα transcriptional activity by CBP and p21 could be envisaged, the simplest model relies upon direct interaction between these proteins. In order to verify this possibility, we tested whether p21 and p27KIP1 directly associate with ERα in vitro. We performed GST pull-down experiments in which GST and GST-ERα fusion proteins, preloaded on glutathione-coupled beads, were incubated with in vitro-translated p21 and p27KIP1. As shown in Fig. 2C, only 35S-labeled p21 interacted with the GST-ERα fusion protein. This prompted us to verify whether the binding of p21, ERα, and CBP could be found in the same complex by coimmunoprecipitation. MCF-7 cells were stimulated over 2 h with estradiol, and nuclear extracts were prepared. Lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with an anti-CBP antibody. The precipitates were treated with dithiothreitol, diluted in the lysis buffer, and then subjected to a second round of immunoprecipitation with an anti-p21 antibody (Fig. 2D, lanes 6 and 7). A fraction of the first immunoprecipitation was saved to determine if ERα and p21 coprecipitated with CBP (lanes 3 to 5). p21 and ERα were found to associate with CBP in the first immunoprecipitation in a ligand-dependent manner (lanes 3 and 4). The second immunoprecipitation with anti-p21 demonstrated that the proteins were in the same complex (lanes 6 and 7).

p21 enhances the estrogen-induced expression of endogenous ERα target gene transcripts in a gene-specific manner.

To get insight in the biological significance of the enhancement of the ERα-transcriptional activity by p21, we investigated whether this mechanism also affects the expression of endogenous estrogen target genes. We determined the amounts of different estrogen-induced mRNA transcripts in MCF-7 cells transfected with a p21 expression vector and in control MCF-7 cells by using RT-QPCR. For transfection we used an electroporation protocol which results in >70% transfection efficiency (68). The estrogen-inducible genes analyzed were those encoding c-Fos, progesterone receptor (PR), pS2, transforming growth factor alpha, cathepsin D, c-Myc, WISP-2, cyclin D1, c-Jun, HMG1, stanniocalcin-2, and lactotransferrin. Among the 12 genes tested, we detected the effects of p21 expression with only four genes: those for PR, WISP-2, c-Myc, and cyclin D1 (Fig. 3A). The estrogen-induced expression of the PR and WISP-2 mRNA transcripts was significantly enhanced by p21, without changes in their basal expression level observed in the absence of estrogen. The weak induction in estrogen-induced expression of the c-Myc mRNA in the presence of p21 may imply a possible transcriptional induction of the c-Myc promoter by p21. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that the increase observed at 6 to 8 h after the addition of estrogen could reflect other indirect mechanisms. In contrast, the cyclin D1 mRNA transcript was strongly reduced in p21-transfected cells. We did not observe any significant effect of p21 on the basal or estrogen-induced expression of other estrogen target genes tested (data not shown). Protein expression analyzed by Western blotting confirmed that p21 enhanced the estradiol-induced expression of the PRB isoform and inhibited the estradiol-induced expression of cyclin D1. In contrast, p21 had no effect on the expression of the PRA isoform or of pS2. The decreased level of ERα found in cells treated with estradiol (Fig. 3B) is due to the proteasome-mediated turnover of transcriptionally active ERα (36, 55). The level of ERα was not modulated by p21. These results indicate that p21 coactivates endogenous ERα target genes in a gene-specific manner.

FIG. 3.

p21 selectively modulates estrogen-dependent transcription. (A) MCF-7 cells electroporated with empty vector or p21 expression vector were incubated in hormone-free medium for 48 h and then stimulated with 10 nM estradiol for 1, 4, or 8 h or left untreated. mRNA levels were analyzed by real-time RT-QPCR, as described in Materials and Methods, with primers specific for ERα target genes. The results after standardization to 36B4 in the same experiments are shown and are the means ± standard errors of triplicates. (B) MCF-7 cells were electroporated as for panel A and placed in medium containing or lacking 10 nM estradiol for 24 h. Cell extracts were prepared and tested for PRB, PRA, pS2, cyclin D1, p21, and ERα proteins by immunoblotting.

p21 siRNA decreases the transcriptional activity of ERα.

We used the pSUPER vector (5) to produce two small interfering RNA duplexes designed to specifically suppress the endogenous p21 (p21-siRNA225 and p21-siRNA400). The same vector encoding an siRNA duplex of scrambled sequence was used as a control in these experiments. MCF-7 cells were transiently transfected by electroporation with these pSUPER vectors together with ERE-tk-luc and were harvested 48 h later. Cell lysates were tested in parallel for the expression of the p21 and β-actin proteins. p21-siRNA400 was more effective in decreasing the p21 expression than p21-siRNA225, the scrambled construct had no effect, and the expression of β-actin was not affected by any of these vectors (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, the hormone-induced transactivation of the ERE-tk-luc was dramatically diminished by transfection with the vector directing the synthesis of p21-siRNA400 (Fig. 4A). These effects were specific, since none of the siRNA tested measurably affected the activity of the β-galactosidase reporter plasmid that was included in each transfection (data not shown). These findings are in agreement with our previous results showing that exogenous p21 acts as a positive regulator of the ERα activity toward an episomal expression vector (54).

FIG. 4.

Endogenous p21 is required for ERα function. (A) MCF-7 cells were electroporated with 20 μg of p21-siRNA400, p21-siRNA225, or scrambled siRNA together with 2 μg of ERE-tk-luc and 0.8 μg of a β-galactosidase construct as an internal control. After overnight incubation, cells were treated with 10 nM estradiol (+E2) or vehicle (−E2) and harvested 24 h later. Extracts were assayed for luciferase and β-galactosidase activities. Luciferase activity was normalized to β-galactosidase activity. Values shown are means ± standard errors from at least three separate experiments. Total lysates of the siRNA-transfected cells were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting for p21 and β-actin. (B) MCF-7 cells were electroporated with 20 μg of p21-siRNA400 or scrambled-siRNA vectors. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were treated with 10 nM estradiol for 8 h or left untreated. mRNAs were analyzed by real-time RT-QPCR to measure the levels of p21, PRB, pS2, and cyclin D1 transcripts. C. MCF-7 cells were electroporated and treated as in panel B. Cell extracts were prepared and tested for ERα, PRB, pS2, and cyclin D1 proteins by immunoblotting.

As a further test of the role of p21 in ERα function, we analyzed whether the p21-siRNA400 vector transfected into MCF-7 cells affected the expression of three endogenous estrogen target genes, PR, pS2, and cyclin D1 (Fig. 4B). Estrogen-induced expression of the PR gene was inhibited by p21-siRNA400, whereas the expression of the pS2 and cyclin D1 genes was unaffected, as determined both by RT-QPCR and by immunoblotting (Fig. 4B and C). Note that only endogenous ERα and p21 were involved in these experiments. Thus, endogenous p21 is required for efficient hormonal induction of the PR gene by endogenous ERα in the MCF-7 cells.

p21 is recruited to the PR promoter in an estrogen-dependent manner.

To determine whether p21 acts directly on the promoters of the endogenous estrogen target genes, we examined the association of p21 to the pS2, cyclin D1, and PR promoters in MCF-7 cells using a ChIP assay. MCF-7 cells were grown in the absence of estrogen for at least 3 days, followed by treatment with a saturating concentration of estradiol for 45 min. An ERα-, p21-, or CBP-specific antibody was used to immunoprecipitate the protein-DNA complexes. The presence of the specific promoters in the chromatin immunoprecipitates was analyzed by PCR with specific pairs of primers spanning the estrogen-responsive regions in the four promoters.

As shown in Fig. 5A, ERα was recruited to the pS2, cyclin D1, and PR promoters in an estrogen-dependent manner. The presence of ERα in the absence of stimulation by estradiol can be attributed to the fact that ERα binds to DNA in vitro and in vivo even in the absence of ligand (55, 59, 62). In the presence of E2, CBP was recruited to the pS2 and PR promoters but not to the cyclin D1 promoter, in agreement with the fact that p300 but not CBP induces the cyclin D1 promoter (2). Treatment with estradiol caused an increase in the occupancy by p21 of the PR gene promoter region from −125 to +187; in contrast, we did not detect any estrogen-dependent interaction of p21 with the PR gene promoter region from +352 to +616 or with the pS2 promoter and cyclin D1 promoter regions. By quantitative real-time PCR analysis, we observed 2-, 2.5-, and 4-fold induction of the PR promoter region from −125 to +187 occupancy by ERα, CBP, and p21, respectively (Fig. 5B). These results suggest that p21 is recruited directly to a subset of estrogen-inducible genes in a gene promoter-specific manner and is involved in estrogen-dependent transcriptional coactivation. It should be noted that the binding of p21 to the PR promoter region from −125 to +187 was observed for the MCF-7 cells not transfected by the p21 expression vector, indicating that endogenous p21 was recruited to the chromosomal PR promoter.

FIG. 5.

p21 is recruited to the PR promoter in an estrogen-dependent manner. (A) Cross-linked, sheared chromatin from MCF-7 cells incubated with or without estradiol (45 min) was immunoprecipitated with the indicated antibodies. DNA was analyzed by PCR, using primers to amplify the pS2 promoter, the cyclin D1 promoter, or two different regions of the PR promoter. Results shown are representative of four independent experiments. (B) Real-time quantitative PCR analysis. Results are shown as percentages of input (means ± standard errors of triplicates). PRB, PR promoter region −125 to +187; PRA, PR promoter region +352 to +616.

p21 expression induces growth arrest and morphological and biochemical differentiation of MCF-7 cells.

Since PR is a differentiation marker for breast cells (18), we next evaluated the phenotypic effects of the expression of p21 in the MCF-7 cells. In this study we stably transfected MCF-7-tTA cells (75) with a vector carrying p21 cDNA under the control of the tetracycline-doxycycline response element, thus creating conditional MCF-7 tet-off-p21 cells. In the absence of DOX, the tetracycline-controlled transactivator protein (tTA) binds to the tetracycline-doxycycline response element and activates transcription of HA-p21. In the clone E15, the level of HA-p21 protein was undetectable in the presence of DOX and increased upon removal of antibiotic from the culture medium to reach a maximum after 48 to 72 h, whereas the level of endogenous p21 was not modified (Fig. 6A). To examine the cell cycle distribution, we performed flow-cytometric analyses of cells treated with or without DOX. As shown in Fig. 6B, MCF-7 and E15 cells in the presence of DOX presented identical cell cycle distribution, whereas removal of DOX concurrent with p21 expression in the E15 clone reduced the proportion of S-phase cells. In conjunction with the inhibition of cell proliferation, we next evaluated the phenotypic consequences of p21 expression. In the presence of DOX, E15 cells were of epithelial type with indistinct cell margins, like the parental cells (Fig. 6C). In the absence of DOX, they underwent significant changes (Fig. 6C). The cells increased in size and flattened. The increase in cell size was predominantly attributable to an abundance of cytoplasm. The cells appeared more columnar and had distinct cellular boundaries. In addition, only minimal mitotic activity was present.

FIG. 6.

p21 inhibits proliferation and induces morphological changes in E15 cells. (A) Induction of exogenous p21 by removal of DOX in the E15 clone. The cells were cultured for 48 h in the presence or absence of DOX and harvested for analysis of HA-p21 expression by Western blotting with an anti-p21 antibody. β-Actin was used as a control. (B) E15 cells were cultured in the presence or absence of DOX for 48 h. Cells were harvested, fixed with ethanol, and stained with propidium iodide. Cell cycle distribution was then determined by flow cytometry. Cell number is plotted against DNA content. (C) MCF-7 cells and E15 cells were cultured with or without DOX for the indicated times. Cytokeratin 18 detection using a Texas Red-tagged secondary antibody is shown. Images were obtained by microscopy (magnification, ×63). Scale bars, 7 μm. The results were verified in three experiments.

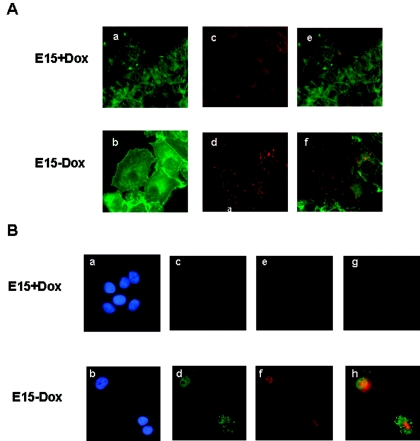

One of the markers of functional differentiation of mammary tissue is the induction of lipid droplets, which are found in the cytoplasm of normal mammary epithelium (21). Lipid droplets are composed mainly of triglycerides and represent an important component of milk. We utilized a fluorescent stain, Nile red, to monitor lipid droplet formation (19) in E15 cells in response to p21 expression. The cells were counterstained with fluorescein-phalloidin, which binds to actin filaments. The absence of DOX did not significantly alter the actin cytoskeleton of E15 cells (Fig. 7A, panel b). In the presence of DOX, E15 cells contained only faintly detectable lipid droplet vacuoles (Fig. 7A, panel c). Lipid droplets accumulated in E15 cells cultured without DOX (Fig. 7A, panel d). The lipid droplets are located in the perinuclear area of E15 cells and may be milk fat triglycerides. Milk contains a mixture of lipids and proteins, including MFG. The expression of these proteins was assessed in E15 cells in the presence or absence of DOX. In the absence of DOX, E15 cells expressed p21 that was essentially located in the nucleus (Fig. 7B, panel d) and were enriched in MFG (Fig. 7B, panel f). Altogether, these morphological changes were suggestive of mammary epithelial differentiation.

FIG. 7.

p21 induces lipid accumulation and milk fat proteins in E15 cells. (A) E15 cells were cultured with (a, c, and e) or without (b, d, and f) DOX for 48 h. Cells were fixed, permeabilized, and then sequentially incubated with fluorescein-phalloidin to identify actin filaments (a and b) and Nile red to identify lipid droplets (c and d). Cells which fluoresce both green and red appear orange (e and f). (B) E15 cells were cultured with (a, c, e, and g) or without (b, d, f, and h) DOX for 48 h. Cells were fixed, permeabilized, and then incubated with either anti-HA or anti-MFG antibody. HA-p21 was detected using a fluorescein-labeled secondary antibody (c and d), and MFGs were detected using a Texas Red-labeled secondary antibody (e and f). Nuclear DNA was stained with DAPI (a and b). Cells which fluoresce both green and red appear orange (g and h). Images were obtained by microscopy (magnification, ×63). The results were confirmed by three independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we provide evidence that p21 functions as a transcriptional regulator of ERα and induces differentiation of MCF-7 breast cancer cells.

p21 enhances transcription through direct interaction with ERα, CBP, and the target promoter sequences.

Previously we reported that p21 enhances estrogen-dependent transcription from the synthetic promoter ERE-tk through a CBP-histone-acetyltransferase activity-dependent mechanism (54). In the present work, we have compared p21 and p27KIP1, a Cdk inhibitor of the same family, and demonstrated that p21 produced a significantly greater enhancement of ERα-dependent transcriptional activity (Fig. 2A). These results suggest that the stimulation of transcription by p21 cannot be accounted for solely by the inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinase activity. Two points should be noted in this context. First, biochemical analyses confirmed that p21 but not p27KIP1 bound to ERα (Fig. 2C). Second, the observations that CBP binds directly to ERα (8, 23, 33), that p21 binds to CBP (10), and that ERα binds to p21 support the possibility that p21, ERα, and CBP can form a ternary complex. Indeed, successive coimmunoprecipitation experiments confirmed that endogenous p21 bound simultaneously to both ERα and CBP, in vivo, in an estrogen-dependent manner (Fig. 2D).

In order to understand the biological significance of transcription-regulatory mechanisms, it is important to verify the conclusions of transient-transfection experiments with endogenous genes. Studying the expression of estrogen-inducible genes in the MCF-7 breast cancer cells, we noted that the enhancement of ERα activity by p21 was not a general phenomenon: p21 enhanced the estrogen-induced expression of the PR and WISP-2 mRNA transcripts and reduced the estrogen-induced cyclin D1 mRNA but had no significant influence on the expression of other target genes tested (Fig. 3A and data not shown). Furthermore, silencing of endogenous p21 by siRNA selectively affected the estrogen-induced expression of the PR mRNA with a concomitant decrease of the protein level but had no effect on cyclin D1 and pS2 mRNA and protein expression (Fig. 4). These results indicate that the effect of p21 was gene specific.

Estrogens regulate several physiologic process in their target cells. Therefore, p21 appears to provide a mechanism that enables the cell to discriminate between the different estrogen-induced genes implicated in specific functions. Although WISP-2 has been identified in MCF-7 breast cancer cells (27), the role of WISP-2 in mediating estrogenic effects has not been fully elucidated. Several reports suggest that WISP-2 expression is independent of DNA synthesis and cell proliferation and that WISP-2 may act as a tumor suppressor (26, 74). The observation that endogenous p21 was recruited in an estrogen-dependent manner to the PR promoter but not to the pS2 promoter suggests that the gene-specific action of p21 may be attributed to its promoter-specific recruitment (Fig. 5). Our data point to the conclusion that p21 facilitates ERα-dependent transcription through direct association with the transcription factor (ERα) bound to a region between −125 and +187 of the promoter and with a coactivator (CBP). This mechanism is superimposed on the indirect effect of p21 via the inhibition of CBP phosphorylation (54). Indeed, p21 was recruited to the region of the promoter encompassing the two Sp1 binding sites located in promoter B and an ERE half-site adjacent to an AP-1 binding site located between promoter A (+464 to +1105) and promoter B (−711 to +31). This region has been reported to play an important role in the activation of the human PR gene (48, 49, 61). Only the 120-kDa PR-B isoform was significantly modulated in the MCF-7 cells. Note that PR-B has a differentiative function in breast cells and that PR-B up-regulates STAT5A, MSX-2, and C/EBPβ, three transcription factors known to be critical for normal mammary gland development (56, 69). Interestingly, progesterone regulates transcription from the p21 promoter and induces up-regulation of p21, leading to cell cycle arrest in breast cancer cells (20, 46); this may suggest a possible positive feedback loop between steroid hormones and p21.

The mechanism by which ERα in the presence of p21 inhibits cyclin D1 gene expression remains to be determined. Cyclin D1 has been shown to be repressed by Cdk inhibitors, such as p16INK4 and p19ARF (12), through distinct elements of the promoter. ERα activates cyclin D1 in part through the CRE/ATF-2 binding site (58). We have not found recruitment of p21 in this promoter region, but we cannot exclude that p21 could be recruited to other regions in the cyclin D1 promoter to mediate the repression effect.

Possible biological role of p21 at the proliferation-differentiation interface.

In the E15 cells, in the presence of hormone, the expression of p21 induced cell cycle arrest in the G0/G1 phase accompanied by changes suggestive of mammary differentiation: increase in cell size attributable to an abundance of cytoplasm; accumulation of cytoplasmic lipid droplets; and induction of milk fat globule proteins, indicators of the differentiated mammary phenotype (Fig. 6 and 7). Induction of p21 in the absence of hormone did not lead to differentiation by any of these criteria. In numerous cell types, G0/G1 arrest has been shown to be necessary but not sufficient for differentiation, which requires a change in the gene expression profile. Thus, in MCF-7 cells, expression of p21 may contribute to ERα-dependent transcriptional activation of specific genes involved in differentiation.

Our results also suggest that the p21 pathway of cell cycle regulation can be dysfunctional during mammary tumor progression. In MCF-7 breast cancer cells, cyclin D1 and c-Myc are induced within 2 to 8 h following treatment with E2, while the level of p21 mRNA decreases to ∼70% of the control level as early as after 4 h and to ∼30% of the control level at 24 h (53; also our unpublished data). The decrease in the transcription rate of p21 may result from the increased c-Myc protein level in the cell. In this context, c-Myc and p21 have been found to reciprocally inactivate one another as a function of their respective concentrations (31). Furthermore, several studies report that through E2F and STAT3, p21 can down-regulate certain genes involved in the proliferation pathway (10, 15). It is generally accepted that p21 is an important regulatory switch: low expression leads to cell cycle progression, whereas high expression causes cell cycle arrest and favors differentiation in certain cell types. Early studies have shown that p21 is the major cyclin-dependent kinase-inhibitory protein in the human estrogen-dependent MCF-7 breast cancer cell line, with little contribution from p27 (51, 53). In this regard, it is interesting that there is a significant correlation between p21 immunoreactivity and well-differentiated histological grade in ER-positive breast carcinoma (45), whereas a reduced expression of p21 is associated with a high risk of breast cancer recurrence (70). These observations and our data concerning the ability of p21 to enhance the estrogen-dependent induction of PR to induce differentiation and to inhibit the expression of genes involved in cell cycle progression point to p21 as a key regulator of the proliferation-differentiation balance in mammary epithelial cells.

In conclusion, we provide evidence that p21 may function as a selective ERα coactivator. In particular, p21 increases the expression of PR in estrogen-stimulated cells, in support of the notion that its cellular functions include the induction of cell differentiation. We propose a model in which p21 enhances ERα-dependent transcription through two types of mechanism. First, it alleviates the block on CBP function mediated by Cdk2 (47, 54); second, the binding of p21 to CBP and ERα can facilitate the recruitment of CBP to the receptor or regulate protein-protein interactions responsible for CBP-mediated transcriptional activation by ERα (Fig. 8). Since p21 increases the acetyltransferase activity of CBP, the p21 coactivation function can be required only for a subset of genes. The cooperation with CBP and p21 may also concern transcription factors other than ERα. For instance, it has been reported that p300/CBP HAT activity is critical for retinoic acid-induced differentiation of F9 cells (4), myogenic terminal differentiation downstream of the expression of p21 (52), and p21-dependent differentiation of keratinocytes (13, 41). Taken together, these results suggest that p21 can enhance CBP HAT activity necessary to activate genes implicated in the differentiation process. The balance of the reciprocal activation between p300/CBP and p21 may determine the course of cellular processes such as proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis. The involvement of p21 in the transcriptional control of a nuclear receptor activity directly implicated in cell growth and differentiation provides a new regulatory mechanism in which cell cycle-regulatory proteins can play a dual function.

FIG. 8.

Proposed model for p21-mediated ERα transactivation. First, p21 inhibits the phosphorylation of CBP by Cdk and thus enhances CBP HAT activity. Second, in the presence of estradiol, p21 binds to CBP and ER on ERE-driven promoters of genes expressed in differentiated cells and favors their transcription.

Acknowledgments

We thank B. Ducommun, N. Rivard, and R. H. Goodman for plasmids. We also thank T. Shioda and S. Ait-Si-Ali for sharing RT-PCR and siRNA information, respectively. We thank D. Catala for technical assistance.

This study was supported by the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), the Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer, and the Ligue Nationale contre le Cancer, Comité de Paris.

REFERENCES

- 1.Acevedo, M. L., and W. L. Kraus. 2003. Mediator and p300/CBP-steroid receptor coactivator complexes have distinct roles, but function synergistically, during estrogen receptor alpha-dependent transcription with chromatin templates. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:335-348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albanese, C., M. D'Amico, A. T. Reutens, M. Fu, G. Watanabe, R. J. Lee, R. N. Kitsis, B. Henglein, M. Avantaggiati, K. Somasundaram, B. Thimmapaya, and R. G. Pestell. 1999. Activation of the cyclin D1 gene by the E1A-associated protein p300 through AP-1 inhibits cellular apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 274:34186-34195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andrews, N. C., and D. V. Faller. 1991. A rapid micropreparation technique for extraction of DNA-binding proteins from limiting numbers of mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 19:2499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brouillard, F., and C. E. Cremisi. 2003. Concomitant increase of histone acetyltransferase activity and degradation of p300 during retinoic acid-induced differentiation of F9 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 278:39509-39516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brummelkamp, T. R., R. Bernards, and R. Agami. 2002. A system for stable expression of short interfering RNAs in mammalian cells. Science 296:550-553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brzozowski, A. M., A. C. Pike, Z. Dauter, R. E. Hubbard, T. Bonn, O. Engstrom, L. Ohman, G. L. Greene, J. A. Gustafsson, and M. Carlquist. 1997. Molecular basis of agonism and antagonism in the oestrogen receptor. Nature 389:753-758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cavailles, V., S. Dauvois, F. L'Horset, G. Lopez, S. Hoare, P. J. Kushner, and M. G. Parker. 1995. Nuclear factor RIP140 modulates transcriptional activation by the estrogen receptor. EMBO J. 14:3741-3751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chakravarti, D., V. J. LaMorte, M. C. Nelson, T. Nakajima, I. G. Schulman, H. Juguilon, M. Montminy, and R. M. Evans. 1996. Role of CBP/P300 in nuclear receptor signalling. Nature 383:99-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chevillard-Briet, M., D. Trouche, and L. Vandel. 2002. Control of CBP co-activating activity by arginine methylation. EMBO J. 21:5457-5466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coqueret, O., and H. Gascan. 2000. Functional interaction of STAT3 transcription factor with the cell cycle inhibitor p21WAF1/CIP1/SDI1. J. Biol. Chem. 275:18794-18800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coradini, D., A. Biffi, C. Pellizzaro, E. Pirronello, and G. Di Fronzo. 1997. Combined effect of tamoxifen or interferon-beta and 4-hydroxyphenylretinamide on the growth of breast cancer cell lines. Tumour Biol. 18:22-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.D'Amico, M., K. Wu, M. Fu, M. Rao, C. Albanese, R. G. Russell, H. Lian, D. Bregman, M. A. White, and R. G. Pestell. 2004. The inhibitor of cyclin-dependent kinase 4a/alternative reading frame (INK4a/ARF) locus encoded proteins p16INK4a and p19ARF repress cyclin D1 transcription through distinct cis elements. Cancer Res. 64:4122-4130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Datto, M. B., P. P. Hu, T. F. Kowalik, J. Yingling, and X. F. Wang. 1997. The viral oncoprotein E1A blocks transforming growth factor beta-mediated induction of p21/WAF1/Cip1 and p15/INK4B. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:2030-2037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delaunay, F., K. Pettersson, M. Tujague, and J. A. Gustafsson. 2000. Functional differences between the amino-terminal domains of estrogen receptors alpha and beta. Mol. Pharmacol. 58:584-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Delavaine, L., and N. B. La Thangue. 1999. Control of E2F activity by p21Waf1/Cip1. Oncogene 18:5381-5392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feigelson, H. S., and B. E. Henderson. 1996. Estrogens and breast cancer. Carcinogenesis 17:2279-2284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feng, X. H., E. H. Filvaroff, and R. Derynck. 1995. Transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta)-induced down-regulation of cyclin A expression requires a functional TGF-beta receptor complex. Characterization of chimeric and truncated type I and type II receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 270:24237-24245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Graham, J. D., and C. L. Clarke. 1997. Physiological action of progesterone in target tissues. Endocr. Rev. 18:502-519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greenspan, P., E. P. Mayer, and S. D. Fowler. 1985. Nile red: a selective fluorescent stain for intracellular lipid droplets. J. Cell Biol. 100:965-973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Groshong, S. D., G. I. Owen, B. Grimison, I. E. Schauer, M. C. Todd, T. A. Langan, R. A. Sclafani, C. A. Lange, and K. B. Horwitz. 1997. Biphasic regulation of breast cancer cell growth by progesterone: role of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors, p21 and p27(Kip1). Mol. Endocrinol. 11:1593-1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hahm, H. A., M. M. Ip, K. Darcy, J. D. Black, W. K. Shea, S. Forczek, M. Yoshimura, and T. Oka. 1990. Primary culture of normal rat mammary epithelial cells within a basement membrane matrix. II. Functional differentiation under serum-free conditions. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. 26:803-814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Halevy, O., B. G. Novitch, D. B. Spicer, S. X. Skapek, J. Rhee, G. J. Hannon, D. Beach, and A. B. Lassar. 1995. Correlation of terminal cell cycle arrest of skeletal muscle with induction of p21 by MyoD. Science 267:1018-1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanstein, B., R. Eckner, J. DiRenzo, S. Halachmi, H. Liu, B. Searcy, R. Kurokawa, and M. Brown. 1996. p300 is a component of an estrogen receptor coactivator complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:11540-11555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harper, J. W., and S. J. Elledge. 1996. Cdk inhibitors in development and cancer. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 6:56-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harris, T. E., J. H. Albrecht, M. Nakanishi, and G. J. Darlington. 2001. CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein-alpha cooperates with p21 to inhibit cyclin-dependent kinase-2 activity and induces growth arrest independent of DNA binding. J. Biol. Chem. 276:29200-29209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Inadera, H. 2003. Estrogen-induced genes, WISP-2 and pS2, respond divergently to protein kinase pathway. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 309:272-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Inadera, H., S. Hashimoto, H. Y. Dong, T. Suzuki, S. Nagai, T. Yamashita, N. Toyoda, and K. Matsushima. 2000. WISP-2 as a novel estrogen-responsive gene in human breast cancer cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 275:108-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jacq, X., C. Brou, Y. Lutz, I. Davidson, P. Chambon, and L. Tora. 1994. Human TAFII30 is present in a distinct TFIID complex and is required for transcriptional activation by the estrogen receptor. Cell 79:107-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jung, D. J., S. K. Lee, and J. W. Lee. 2001. Agonist-dependent repression mediated by mutant estrogen receptor alpha that lacks the activation function 2 core domain. J. Biol. Chem. 276:37280-37283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kawasaki, H., R. Eckner, T. P. Yao, K. Taira, R. Chiu, D. M. Livingston, and K. K. Yokoyama. 1998. Distinct roles of the co-activators p300 and CBP in retinoic-acid-induced F9-cell differentiation. Nature 393:284-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kitaura, H., M. Shinshi, Y. Uchikoshi, T. Ono, S. M. Iguchi-Ariga, and H. Ariga. 2000. Reciprocal regulation via protein-protein interaction between c-Myc and p21(cip1/waf1/sdi1) in DNA replication and transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 275:10477-10483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Korach, K. S. 1994. Insights from the study of animals lacking functional estrogen receptor. Science 266:1524-1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kraus, W. L., and J. T. Kadonaga. 1998. p300 and estrogen receptor cooperatively activate transcription via differential enhancement of initiation and reinitiation. Genes Dev. 12:331-342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kumar, R., R. A. Wang, A. Mazumdar, A. H. Talukder, M. Mandal, Z. Yang, R. Bagheri-Yarmand, A. Sahin, G. Hortobagyi, L. Adam, C. J. Barnes, and R. K. Vadlamudi. 2002. A naturally occurring MTA1 variant sequesters oestrogen receptor-alpha in the cytoplasm. Nature 418:654-657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu, M., M. H. Lee, M. Cohen, M. Bommakanti, and L. P. Freedman. 1996. Transcriptional activation of the Cdk inhibitor p21 by vitamin D3 leads to the induced differentiation of the myelomonocytic cell line U937. Genes Dev. 10:142-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lonard, D. M., Z. Nawaz, C. L. Smith, and B. W. O'Malley. 2000. The 26S proteasome is required for estrogen receptor-alpha and coactivator turnover and for efficient estrogen receptor-alpha transactivation. Mol. Cell 5:939-948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mal, A., D. Chattopadhyay, M. K. Ghosh, R. Y. Poon, T. Hunter, and M. L. Harter. 2000. p21 and retinoblastoma protein control the absence of DNA replication in terminally differentiated muscle cells. J. Cell Biol. 149:281-292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mangelsdorf, D. J., C. Thummel, M. Beato, P. Herrlich, G. Schutz, K. Umesono, B. Blumberg, P. Kastner, M. Mark, P. Chambon, et al. 1995. The nuclear receptor superfamily: the second decade. Cell 83:835-839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marmorstein, R. 2001. Protein modules that manipulate histone tails for chromatin regulation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2:422-432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Merot, Y., R. Metivier, G. Penot, D. Manu, C. Saligaut, F. Gannon, F. Pakdel, O. Kah, and G. Flouriot. 2004. The relative contribution exerted by AF-1 and AF-2 transactivation functions in estrogen receptor alpha transcriptional activity depends upon the differentiation stage of the cell. J. Biol. Chem. 279:26184-26191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Missero, C., E. Calautti, R. Eckner, J. Chin, L. H. Tsai, D. M. Livingston, and G. P. Dotto. 1995. Involvement of the cell-cycle inhibitor Cip1/WAF1 and the E1A-associated p300 protein in terminal differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:5451-5455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nakanishi, M., G. R. Adami, R. S. Robetorye, A. Noda, S. F. Venable, D. Dimitrov, O. M. Pereira-Smith, and J. R. Smith. 1995. Exit from G0 and entry into the cell cycle of cells expressing p21Sdi1 antisense RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:4352-4356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nilsson, S., and J. A. Gustafsson. 2000. Estrogen receptor transcription and transactivation: basic aspects of estrogen action. Breast Cancer Res. 2:360-366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nilsson, S., S. Makela, E. Treuter, M. Tujague, J. Thomsen, G. Andersson, E. Enmark, K. Pettersson, M. Warner, and J. A. Gustafsson. 2001. Mechanisms of estrogen action. Physiol. Rev. 81:1535-1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oh, Y. L., J. S. Choi, S. Y. Song, Y. H. Ko, B. K. Han, S. J. Nam, and J. H. Yang. 2001. Expression of p21Waf1, p27Kip1 and cyclin D1 proteins in breast ductal carcinoma in situ: relation with clinicopathologic characteristics and with p53 expression and estrogen receptor status. Pathol. Int. 51:94-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Owen, G. I., J. K. Richer, L. Tung, G. Takimoto, and K. B. Horwitz. 1998. Progesterone regulates transcription of the p21(WAF1) cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor gene through Sp1 and CBP/p300. J. Biol. Chem. 273:10696-10701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Perkins, N. D., L. K. Felzien, J. C. Betts, K. Leung, D. H. Beach, and G. J. Nabel. 1997. Regulation of NF-κB by cyclin-dependent kinases associated with the p300 coactivator. Science 275:523-527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Petz, L. N., and A. M. Nardulli. 2000. Sp1 binding sites and an estrogen response element half-site are involved in regulation of the human progesterone receptor A promoter. Mol. Endocrinol. 14:972-985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Petz, L. N., Y. S. Ziegler, M. A. Loven, and A. M. Nardulli. 2002. Estrogen receptor alpha and activating protein-1 mediate estrogen responsiveness of the progesterone receptor gene in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Endocrinology 143:4583-4591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pfaffl, M. W. 2001. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Planas-Silva, M. D., and R. A. Weinberg. 1997. Estrogen-dependent cyclin E-cdk2 activation through p21 redistribution. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:4059-4069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Polesskaya, A., I. Naguibneva, L. Fritsch, A. Duquet, S. Ait-Si-Ali, P. Robin, A. Vervisch, L. L. Pritchard, P. Cole, and A. Harel-Bellan. 2001. CBP/p300 and muscle differentiation: no HAT, no muscle. EMBO J. 20:6816-6825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Prall, O. W., B. Sarcevic, E. A. Musgrove, C. K. Watts, and R. L. Sutherland. 1997. Estrogen-induced activation of Cdk4 and Cdk2 during G1-S phase progression is accompanied by increased cyclin D1 expression and decreased cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor association with cyclin E-Cdk2. J. Biol. Chem. 272:10882-10894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Redeuilh, G., A. Attia, J. Mester, and M. Sabbah. 2002. Transcriptional activation by the oestrogen receptor alpha is modulated through inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinases. Oncogene 21:5773-5782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reid, G., M. R. Hubner, R. Metivier, H. Brand, S. Denger, D. Manu, J. Beaudouin, J. Ellenberg, and F. Gannon. 2003. Cyclic, proteasome-mediated turnover of unliganded and liganded ERα on responsive promoters is an integral feature of estrogen signaling. Mol. Cell 11:695-707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Richer, J. K., B. M. Jacobsen, N. G. Manning, M. G. Abel, D. M. Wolf, and K. B. Horwitz. 2002. Differential gene regulation by the two progesterone receptor isoforms in human breast cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 277:5209-5218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rosenfeld, M. G., and C. K. Glass. 2001. Coregulator codes of transcriptional regulation by nuclear receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 276:36865-36868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sabbah, M., D. Courilleau, J. Mester, and G. Redeuilh. 1999. Estrogen induction of the cyclin D1 promoter: involvement of a cAMP response-like element. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:11217-11222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sabbah, M., F. Gouilleux, B. Sola, G. Redeuilh, and E. E. Baulieu. 1991. Structural differences between the hormone and antihormone estrogen receptor complexes bound to the hormone response element. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:390-394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sabbah, M., K. I. Kang, L. Tora, and G. Redeuilh. 1998. Oestrogen receptor facilitates the formation of preinitiation complex assembly: involvement of the general transcription factor TFIIB. Biochem. J. 336:639-646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schultz, J. R., L. N. Petz, and A. M. Nardulli. 2003. Estrogen receptor alpha and Sp1 regulate progesterone receptor gene expression. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 201:165-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shang, Y., X. Hu, J. DiRenzo, M. A. Lazar, and M. Brown. 2000. Cofactor dynamics and sufficiency in estrogen receptor-regulated transcription. Cell 103:843-852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sherr, C. J. 1994. G1 phase progression: cycling on cue. Cell 79:551-555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shi, Y., M. Downes, W. Xie, H. Y. Kao, P. Ordentlich, C. C. Tsai, M. Hon, and R. M. Evans. 2001. Sharp, an inducible cofactor that integrates nuclear receptor repression and activation. Genes Dev. 15:1140-1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sutherland, R. L., R. E. Hall, and I. W. Taylor. 1983. Cell proliferation kinetics of MCF-7 human mammary carcinoma cells in culture and effects of tamoxifen on exponentially growing and plateau-phase cells. Cancer Res. 43:3998-4006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Thompson, E. W., S. Paik, N. Brunner, C. L. Sommers, G. Zugmaier, R. Clarke, T. B. Shima, J. Torri, S. Donahue, and M. E. Lippman. 1992. Association of increased basement membrane invasiveness with absence of estrogen receptor and expression of vimentin in human breast cancer cell lines. J. Cell. Physiol. 150:534-544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Toscani, A., D. R. Soprano, and K. J. Soprano. 1990. Sodium butyrate in combination with insulin or dexamethasone can terminally differentiate actively proliferating Swiss 3T3 cells into adipocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 265:5722-5730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.van den Hoff, M. J., A. F. Moorman, and W. H. Lamers. 1992. Electroporation in ‘intracellular’ buffer increases cell survival. Nucleic Acids Res. 20:2902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Visvader, J. E., and G. J. Lindeman. 2003. Transcriptional regulators in mammary gland development and cancer. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 35:1034-1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wakasugi, E., T. Kobayashi, Y. Tamaki, Y. Ito, I. Miyashiro, Y. Komoike, T. Takeda, E. Shin, Y. Takatsuka, N. Kikkawa, T. Monden, and M. Monden. 1997. p21(Waf1/Cip1) and p53 protein expression in breast cancer. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 107:684-691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wakeling, A. E., M. Dukes, and J. Bowler. 1991. A potent specific pure antiestrogen with clinical potential. Cancer Res. 51:3867-3873. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wu, S. Y., M. C. Thomas, S. Y. Hou, V. Likhite, and C. M. Chiang. 1999. Isolation of mouse TFIID and functional characterization of TBP and TFIID in mediating estrogen receptor and chromatin transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 274:23480-23490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yahata, T., W. Shao, H. Endoh, J. Hur, K. R. Coser, H. Sun, Y. Ueda, S. Kato, K. J. Isselbacher, M. Brown, and T. Shioda. 2001. Selective coactivation of estrogen-dependent transcription by CITED1 CBP/p300-binding protein. Genes Dev. 15:2598-2612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhang, R., L. Averboukh, W. Zhu, H. Zhang, H. Jo, P. J. Dempsey, R. J. Coffey, A. B. Pardee, and P. Liang. 1998. Identification of rCop-1, a new member of the CCN protein family, as a negative regulator for cell transformation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:6131-6141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zwijsen, R. M., R. Klompmaker, E. B. Wientjens, P. M. Kristel, B. van der Burg, and R. J. Michalides. 1996. Cyclin D1 triggers autonomous growth of breast cancer cells by governing cell cycle exit. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:2554-2560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]