Abstract

ATR associates with the regulatory protein ATRIP that has been proposed to localize ATR to sites of DNA damage through an interaction with single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) coated with replication protein A (RPA). We tested this hypothesis and found that ATRIP is required for ATR accumulation at intranuclear foci induced by DNA damage. A domain at the N terminus of ATRIP is necessary and sufficient for interaction with RPA–ssDNA. Deletion of the ssDNA–RPA interaction domain of ATRIP greatly diminished accumulation of ATRIP into foci. However, the ATRIP–RPA–ssDNA interaction is not sufficient for ATRIP recognition of DNA damage. A splice variant of ATRIP that cannot bind to ATR revealed that ATR association is also essential for proper ATRIP localization. Furthermore, the ATRIP–RPA–ssDNA interaction is not absolutely essential for ATR activation because ATR phosphorylates Chk1 in cells expressing only a mutant of ATRIP that does not bind to RPA–ssDNA. These data suggest that binding to RPA–ssDNA is not the essential function of ATRIP in ATR-dependent checkpoint signaling and ATR has an important function in properly localizing the ATR–ATRIP complex.

INTRODUCTION

Cellular responses to genotoxic stress include cell cycle arrest, DNA repair, changes in transcription, and apoptosis. Signal transduction pathways that begin with activation of the phosphoinositide-3-kinase-like protein kinases, including ataxia-telangiectasia mutated (ATM) and ATM- and Rad3-related (ATR), coordinate these DNA damage responses.

ATM and ATR share sequence homology, substrates, and functions. Loss of ATM or ATR activity causes similar cellular phenotypes, including loss of cell cycle checkpoints and increased sensitivity to DNA damage (Abraham, 2001; Shiloh, 2001). One difference between these signaling pathways is that ATM primarily responds to DNA double strand breaks, whereas ATR responds to many forms of genotoxic stress, including DNA cross-links, base modifications, and stalling of replication forks. A key question is what allows ATR to respond to a diverse array of genetic insults, whereas ATM is limited primarily to double strand breaks.

An important clue to the biochemical differences between ATM and ATR came with the identification of an accessory protein that functions exclusively with ATR (Edwards et al., 1999; Paciotti et al., 2000; Rouse and Jackson, 2000; Cortez et al., 2001; Wakayama et al., 2001). This protein, Rad26 in Schizosaccharomyces pombe, DDC2/LCD1/PIE1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, or ATRIP in humans, binds to ATR and is required for ATR signaling. Deletion of the yeast ATRIP genes or RNA inhibition of ATRIP expression in human cells leads to nearly identical phenotypes as observed when ATR is deleted (Uchiyama et al., 1997; Edwards et al., 1999; Paciotti et al., 2000; Rouse and Jackson, 2000; Cortez et al., 2001; Wakayama et al., 2001). Importantly, ATRIP does not associate with ATM (Cortez et al., 2001). Thus, one hypothesis to explain how ATR can be activated by different genotoxic stresses than ATM is that ATRIP provides the broadened specificity. A second clue to how ATR might be activated differently than ATM came with the observation that ATR activation often requires DNA replication (Michael et al., 2000; Lupardus et al., 2002; Tercero et al., 2003). The interaction of a replication fork with a DNA lesion may be essential for activating ATR in many circumstances. In fact, ATR has increased activity during normal DNA replication in yeast cells and Xenopus egg extracts (Edwards et al., 1999; Paciotti et al., 2000; Shechter et al., 2004), and ATR is an essential gene in cycling human and mouse cells (Brown and Baltimore, 2000; Cortez et al., 2001). Furthermore, ATR phosphorylates some components of the replication fork, including the MCM helicase complex (Cortez et al., 2004).

The question remains how can a protein kinase complex respond to such diverse genetic insults as an interstrand cross-link, stalled replication fork, or double strand break? One model proposes that ATR is activated by physically associating with sites of DNA damage or stalled replication forks. Indeed, both ATR and ATRIP relocalize to intranuclear foci in response to DNA damage and a fraction of these proteins is chromatin associated (Hekmat-Nejad et al., 2000; Cortez et al., 2001; Lupardus et al., 2002; Dart et al., 2004). Observations that ATR activation is impaired in Xenopus extracts by depleting the single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) binding protein RPA, and ATR localization to foci in human cells is impaired when RPA expression is inhibited by RNA inhibition support this model (Costanzo et al., 2003; Zou and Elledge, 2003; Dart et al., 2004). Furthermore, ATRIP was recently shown to bind to RPA-coated ssDNA directly (Zou and Elledge, 2003), and DDC2 does not localize to sites of DNA damage in yeast mutants defective in the single-stranded binding protein RFA1 (Lisby et al., 2004). Thus, ATRIP may promote specific relocalization and activation of ATR in response to a variety of DNA lesions that are processed to expose ssDNA-bound to RPA.

In this study, we have directly tested this ssDNA–RPA recruitment model for activation of ATRIP–ATR. Surprisingly, our data indicate that an interaction between ssDNA–RPA and ATRIP is neither sufficient for ATRIP accumulation at DNA lesions nor absolutely essential for ATR-dependent checkpoint signaling.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture, Small Interfering RNA (siRNA), and Transfections

All cell lines were maintained in DMEM + 10% fetal bovine serum. Retroviruses were packaged using calcium phosphate transfections of the Phoenix-Amphotropic packaging cell line. Transfections of plasmid DNA were accomplished by Lipofectamine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Transfections of siRNA were performed with Oligofectamine (Invitrogen). The ATRIP siRNA target sequence is AAGGUCCACAGAUUAUUAGAU. The ATR siRNA target sequence is AACCUCCGUGAUGUUGCUUGA. The nonspecific control oligonucleotide target sequence is AAAUGAACGUGAAUUGCUCAA. All RNA oligonucleotides were purchased from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO).

Two Hybrid

Random fragment libraries of ATRIP and ATR were prepared by fragmenting plasmids containing the ATRIP and ATR cDNAs by using a nebulizer and N2. Fragments (350–1500 bp) were blunted with T4 DNA polymerase, and XhoI linkers were added. These fragments were ligated into pACT containing the DNA activation domain of GAL4. Approximately 60,000 colonies, with >90% inserts, were obtained for the pACT–ATRIP library, and 80,000 colonies, with >90% inserts, were obtained for the pACT–ATR library. The pACT–ATR library was screened with pAS2 containing the full-length ATRIP cDNA fused to the GAL4 DNA binding domain. The pACT–ATRIP library was screened with amino acids 1–388 of ATR in pAS2. The pJ694a yeast strain was used in all screening procedures (James et al., 1996).

RPA–ssDNA Binding

The 14- and 70-kDa subunits are tagged with a His6 epitope tag (Stauffer and Chazin, 2004). RPA was purified from Escherichia coli using nickel affinity chromatography followed by Superdex fractionation. Twenty picomoles of biotin-labeled 69-base pair single-stranded oligonucleotide was bound to streptavidin beads and then incubated either with binding buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0.02% Igepal CA-630, and 10 μg/ml bovine serum albumin) alone or a 4 M excess of RPA in binding buffer. The RPA–ssDNA–streptavidin beads were washed three times with binding buffer before use. 293T cells transiently expressing ATRIP or ATRIP fragments were lysed in NETN buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% Igepal CA-630, 5 μg/ml aprotinin, 5 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 mM NaF, 20 mM β-glycerol phosphate, 1 mM sodium vanadate, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). Lysates were cleared by centrifugation. Beads containing the ssDNA with or without RPA were added to the cleared lysates, incubated for 1.5 h, and washed three times with NETN buffer. Proteins bound to beads were eluted and separated by SDS-PAGE before blotting.

DNA Constructs

Wobble base pair mutations in ATRIP were introduced by site-directed mutagenesis to make it immune to siRNA silencing by using the following primer and its complement: CGGGACGTGTCCAGTGATCATAAAGTGCACCGATTATTAGATGGCATGTCAAAAAATCC. Retroviral vectors were created by transferring the ATRIP cDNA into either pLNCX2 or pLPCX by using XhoI-NotI digests. ATRIP 1-107 and ATRIP 108-791 were made using PCR. A nuclear localization signal was added to some constructs by inserting the codons encoding the sequence PKKKRKV. All constructs generated using PCR were confirmed by sequencing.

Semiquantitative Reverse Transcription (RT)-PCR

RNA was extracted from HeLa and HCT116 cells by using the RNeasy kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA). Semiquantitative RT-PCR was performed using a poly(dT) primer and Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase, followed by PCR with the ATRIP primers 5′-GACAGAGTGGCCTTGGAGAC-3′ and 5′-ACGCAGTGCATCATGAAGAG-3′ or Actin primers 5′-AAGTACCCCATTGAGCATGGC-3′ and 5′-CACAGCTTCTCCTTGATGTCGC-3′.

Antibodies and Localization

The ATRIP antibody has been described previously (Cortez et al., 2001). Antibodies to Chk1 and ATR were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA); fluorescein isothiocyanate-(FITC) and rhodamine-red X–conjugated secondary antibodies were obtained from Jackson Immuno-Research Laboratories (West Grove, PA); Chk1 P345 antibody was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Immunofluorescence was performed by plating cells directly on glass coverslips. Cells were fixed with paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with Triton X-100 as described previously (Wang et al., 2000). Images were obtained with a Zeiss Axioplan microscope equipped with a Zeiss camera and software.

RESULTS

Identification of ATR–ATRIP Interaction Domains

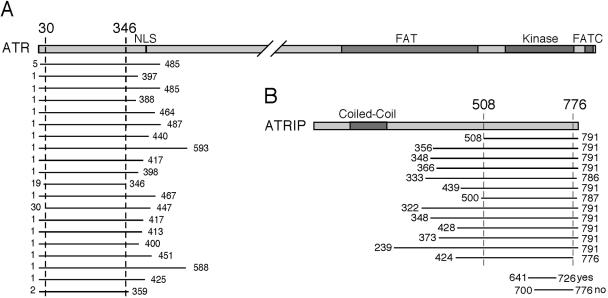

The ATRIP protein is associated with ATR in mammalian cells (Cortez et al., 2001). We used a two-hybrid approach to determine domains of ATR and ATRIP that are sufficient for the ATR–ATRIP interaction. A library of random fragments of ATR fused to the GAL4 activation domain was produced by mechanical shearing and ligation. This library contained >9000 expressed fragments of ATR between 100 and 500 amino acids in length. Full-length ATRIP fused to the GAL4 DNA binding domain was used as a bait to screen this library. Sequencing 20 of the ATR fragments recovered revealed that ATR binds to ATRIP through an N-terminal domain containing ATR amino acids 30–346 (Figure 1A). This domain of ATR is not conserved in ATM, which explains why ATRIP is specific to ATR complexes.

Figure 1.

Mapping the ATR–ATRIP interaction domains. (A) A library of ATR fragments fused to the Gal4 activation domain was transformed into yeast strain PJ694a containing full-length ATRIP fused to the Gal4 DNA binding domain. Cells were plated on media to select for positive-interacting fragments. Twenty plasmids containing ATR fragments that interacted with ATRIP were recovered and sequenced. A schematic diagram of where on the 2644-amino acid ATR protein these fragments are located is shown along with their starting and ending amino acid numbers. (B) A library of ATRIP fragments fused to the Gal4 activation domain was transformed into yeast strain PJ694a containing ATR amino acids 1–388 fused to the DNA binding domain of Gal4. Cells were plated on selective media, and 13 of the fragments that interacted with ATR1–388 were recovered and sequenced. In addition, two smaller fragments of ATRIP containing either amino acids 641–726 or 700–776 were tested directly for interaction with ATR1-388 in the PJ694a strain.

A fragment of ATR containing amino acids 1–388 fused to the GAL4 DNA binding domain was used as a bait to screen a library of random fragments of ATRIP fused to the activation domain of GAL4. This library contained ∼5000 expressed fragments of ATRIP between 100 and 500 amino acids in length. Sequencing of ATRIP fragments capable of interaction with ATR revealed that all of the interacting fragments contained amino acids 508–776 of ATRIP (Figure 1B). We tested whether smaller ATRIP fragments also could interact with ATR in the two-hybrid system and found that amino acids 641–726 were sufficient for interaction with ATR, but amino acids 700–776 were incapable of interaction, suggesting a requirement for amino acids residues between 641 and 700. Although ATRIP amino acids 641–726 are sufficient to interact with the N terminus of ATR in a yeast two-hybrid analysis, other ATRIP domains are required to stabilize this interaction in human cells (Cortez et al., 2001).

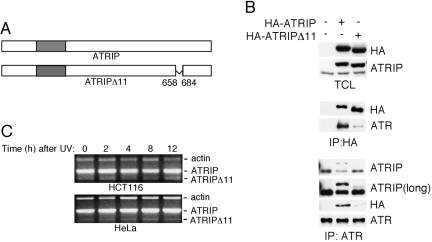

We previously reported that this C-terminal region of ATRIP is subject to alternative splicing that removes exon 11 that codes for amino acids 658–684 (Figure 2A) (Cortez et al., 2001). This alternatively spliced message (ATRIPΔ11) removes amino acids mapping exactly to the region that interacts with ATR. Therefore, we tested whether ATRIPΔ11 could bind to ATR. Expression of hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged wild-type ATRIP or HA-ATRIPΔ11 in mammalian cells followed by immunoprecipitation with the HA antibody revealed that ATRIPΔ11 is severely compromised in its ability coimmunoprecipitate ATR compared with full-length ATRIP (Figure 2B). Furthermore, ATR immunoprecipitates contained very little HA-ATRIPΔ11 compared with HA-ATRIP. Thus, amino acids 658–684 of ATRIP are necessary for efficient ATR interaction. RT-PCR revealed that ATRIPΔ11 mRNA levels are <5% of the levels of full-length ATRIP and are not appreciably altered by treating either p53 wild-type or p53-defective cells with UV light (Figure 2C). We also found no regulation of expression of this transcript in response to ionizing radiation (IR) or hydroxyurea (HU) (our unpublished data). To determine whether ATRIPΔ11 mRNA is translated into protein, we purified ATRIP by using antibodies to the N terminus of ATRIP. Mass spectrometry revealed a peptide VALETQWLQLEQEVVR that is unique to ATRIPΔ11 in addition to the peptide expected for full-length ATRIP (our unpublished data). Thus, the ATRIPΔ11 message can be made into protein, but it is not clear what percentage of ATRIP in a cell is ATRIPΔ11, nor is it clear what function it might have. Nonetheless, the failure of ATRIPΔ11 to bind to ATR confirmed the yeast two-hybrid data mapping the interaction domain for ATR on ATRIP to its C terminus. Furthermore, ATRIPΔ11 provides a reagent to investigate the role of the ATR–ATRIP interaction in checkpoint signaling.

Figure 2.

An alternatively spliced ATRIP protein missing exon 11 is expressed in cells and cannot bind to ATR. (A) A schematic diagram of ATRIPΔ11 and wild-type ATRIP. (B) HA-ATRIP or HA-ATRIPΔ11 was stably expressed in HeLa cells. The total cell lysate (TCL) blots indicate equal expression levels. Immunoprecipitations (IP) from cell lysates were performed with either HA or ATR antibodies, separated by SDS-PAGE, and blotted with the indicated antibodies. ATRIP (long) is a longer exposure of the ATRIP blot to show the small amount of coimmunoprecipitated ATRIPΔ11 found in an ATR complex. (C) HCT116 or HeLa cells were treated with 50 J/m2 of UV light and then incubated for the indicated number of hours. RNA was extracted and PCR was performed with primers specific to ATRIP or actin after reverse-transcription to generate cDNA. Cloning and sequencing confirmed the ATRIPΔ11 product.

ATRIP–RPA–ssDNA Interaction Is Not Sufficient for ATR–ATRIP Localization and Signaling

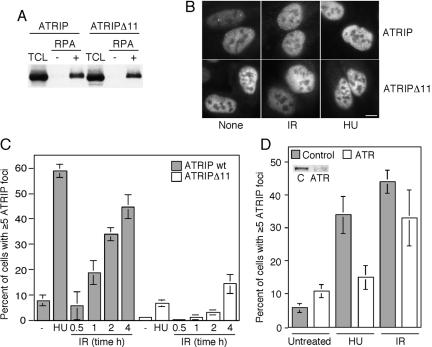

ATRIP has been proposed to localize ATR to sites of DNA damage through an interaction with ssDNA bound to RPA. If this model were correct, then we would expect a mutant of ATRIP that cannot bind ATR to localize to damage-induced intranuclear foci but fail to recruit ATR. The ATRIPΔ11 protein provides a means of testing this hypothesis. First, we determined whether ATRIPΔ11 binds to RPA–ssDNA with the same efficiency as full-length ATRIP. ssDNA bound to streptavidin beads was coated with RPA purified from bacteria and then incubated with lysates of mammalian cells overexpressing either HA-ATRIP or HA-ATRIPΔ11. Both ATRIP and ATRIPΔ11 efficiently bound to the ssDNA coated with RPA but not to ssDNA alone (Figure 3A). Thus, ATR is not required for the ATRIP–RPA–ssDNA interaction as expected.

Figure 3.

ATRIPΔ11 binds to RPA but does not localize to sites of DNA damage or replication stress efficiently. (A) Phoenix derivatives of human embryonic kidney 293 cells were transfected with retroviral vectors expressing HA-ATRIP or HA-ATRIPΔ11. Cells were lysed and incubated with beads bound to single-stranded DNA that had either been coated with recombinant RPA (+) or mock coated (-). After extensive washing, proteins bound to the beads were denatured and separated by SDS-PAGE followed by blotting with an HA antibody. Total cell lysate (TCL) is 5% of the lysate used in the pull down. (B) Indirect immunofluorescence was performed on U2OS cells stably expressing HA-ATRIP or HA-ATRIPΔ11 that had either been left untreated (none) or exposed to 8Gy of IR or 2 mM HU. Representative photographs of cells are shown. Bar, 10 μm. (C) Quantitation of HA–ATRIP or HA–ATRIPΔ11 foci formation. Cells containing five or more easily visualized foci were counted as positive. Cells were left untreated (-), exposed to HU for 5.5 h, or irradiated and then incubated for the indicated number of hours before staining. (D) Quantitation of HA–ATRIP foci formation in cells transfected with control or ATR-specific siRNA oligonucleotides. Cells were transfected with siRNA 3 d before treating with either 2 mM HU for 5.5 h or 8 Gy of IR 3 h before fixation. The inset is a Western blot using ATR antibodies to show the overall levels of ATR in the control and ATR siRNA-transfected cells. Error bars on all graphs indicate standard deviations where 100 cells were scored separately three times.

Next, U2OS cells were infected with retroviruses encoding either HA-ATRIP or HA-ATRIPΔ11, and the localization of these proteins was analyzed using immunofluorescence microscopy. Surprisingly, we found a marked decrease in the number of cells containing ATRIPΔ11 foci compared with full-length ATRIP (Figure 3, B and 3C). After exposure to HU, ATRIPΔ11 formed foci in only 8% of cells compared with 58% for full-length ATRIP (Figure 3C). A similarly severe defect in ATRIPΔ11 foci formation was observed after ionizing radiation. A time-course analysis after IR treatment indicated that this lack of ATRIPΔ11 foci formation was probably not due to a failure to maintain the protein at foci because the defect is most severe at early times after IR (Figure 3C). There is also a decrease in the number of undamaged cells with ATRIPΔ11 foci (1%) compared with full-length ATRIP (8%) consistent with a role for ATR–ATRIP signaling in an unperturbed S phase.

These data suggest that ATR binding is required for ATRIP to localize to sites of DNA damage. In support of this conclusion, siRNA targeting ATR reduces the ability of ATRIP to form foci (Figure 3D). This experiment was done using U2OS cells stably expressing HA-ATRIP at a level ∼3–6 times over endogenous protein levels because loss of ATR from cells reduces the levels of endogenous ATRIP (Cortez et al., 2001). ATR levels were reduced by ∼80% by the siRNA treatment (Figure 3D, inset). Under these conditions 13% of HU-treated cells and 31% of IR-treated cells contained HA–ATRIP foci compared with 33% of HU-treated and 45% of IR-treated cells transfected with a nonspecific siRNA. This ATR dependency for ATRIP foci formation is likely to be an underestimation of the requirement because all cells in the population were counted, including cells that did not take up the siRNA and continue to express normal levels of ATR. Thus, the ATRIP–RPA–ssDNA interaction is not sufficient to target ATRIP to sites of DNA damage or replication stress. An ATRIP–ATR interaction also is required for proper ATRIP localization.

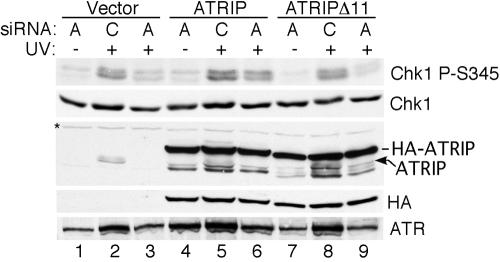

Based on the severe reduction in the ability of ATRIPΔ11 to localize to sites of DNA damage and bind to ATR, we expected that this alternatively spliced protein would be unable to promote ATR signaling. In yeast, ATRIP proteins are essential for signaling by ATR orthologues. To prove that ATRIPΔ11 cannot function in ATRIP–ATR-dependent signaling we developed an ATRIP complementation assay in which endogenous ATRIP is replaced by HA-tagged ATRIP proteins. Both the HA–ATRIP and HA–ATRIPΔ11 proteins were stably expressed at the same levels from retroviral vectors in U2OS cells. These cDNAs were altered to make them immune to siRNA targeting endogenous ATRIP by mutating two wobble base pairs in the cDNA target sequence. Stable expression of HA-ATRIPΔ11 did not cause any noticeable phenotypic consequences to the cells. siRNA depletion of endogenous ATRIP in vector control cells caused a severe reduction in the UV-induced Chk1S345 phosphorylation that is an ATR-dependent phosphorylation event (Figure 4). Expression of full-length HA-ATRIP but not HA-ATRIPΔ11 was capable of suppressing this reduction (Figure 4). The ATRIP siRNA was slightly less effective in reducing endogenous ATRIP in both the HA-ATRIP wildtype and HA-ATRIPΔ11–expressing cells compared with the empty vector cells, perhaps indicating that the HA–ATRIP mRNAs with two wobble base pair changes in the siRNA recognition sequence can partially interfere with the siRNA targeting of the endogenous ATRIP mRNA. However, reduction of endogenous ATRIP was still >80% and was sufficient to reveal that the ATRIPΔ11 protein is defective in promoting Chk1 phosphorylation. Expression of HA-ATRIP did not alter the expression level of endogenous ATRIP. Depletion of endogenous ATRIP does reduce the ATR levels especially in the vector and HA–ATRIPΔ11 cells. This presumably reflects a requirement for ATRIP binding to stabilize ATR (Cortez et al., 2001) and partly explains the loss of Chk1 phosphorylation in the vector and HA–ATRIPΔ11 cells. Thus, the ATR–ATRIP interaction is required for proper ATRIP foci formation and Chk1S345 phosphorylation in response to genotoxic stress.

Figure 4.

ATRIPΔ11 cannot support ATR-dependent signaling. U2OS cells infected with retroviruses containing either no cDNA (vector), HA-ATRIP, or HA-ATRIPΔ11 were transfected with ATRIP siRNA (A) or nonspecific siRNA (C). The cDNAs were made immune to the ATRIP siRNA by mutations of wobble base pairs in the target sequence. Cells were either mock treated or treated with 30 J/m2 of UV light and then incubated for 2 h. Cell lysates were separate by SDS-PAGE and blotted with antibodies to ATR, HA, ATRIP, Chk1, or phosphorylation-specific antibodies to Chk1 P-S345. The ATRIP blot is labeled to indicate the HA-ATRIP protein, endogenous ATRIP, and two bands that cross-react with the ATRIP antibody (*). There is also a degradation product of the HA–ATRIP and HA–ATRIPΔ11 proteins in lanes 4–9.

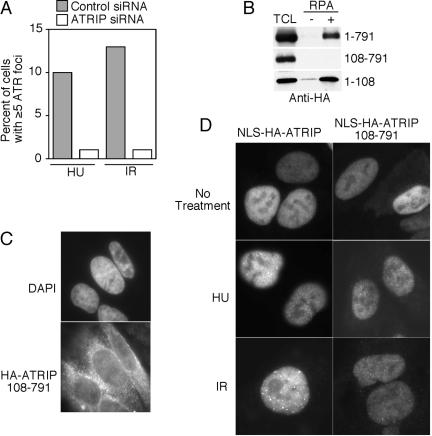

The ATRIP–RPA–ssDNA Interaction Is Required for ATR–ATRIP Accumulation in Damage-induced Foci

Because an ATRIP–RPA–ssDNA interaction was not sufficient for proper ATRIP localization and signaling, we tested whether it was necessary. We found that ATRIP is necessary for ATR accumulation at sites of genotoxic stress because cells that have been treated with siRNA to ATRIP fail to show DNA damage or replication stress-induced ATR foci formation (Figure 5A). This experiment was performed by overexpressing an HA-tagged form of ATR to compensate for any endogenous ATR loss observed after ATRIP siRNA treatment (Cortez et al., 2001). It should be noted that the percentages of cells with ATR foci in this experiment is lower than what might be expected based on ATRIP foci formation rates. This is most likely due to the methodology of transient overexpression of ATR from a strong cytomegalovirus promoter that frequently caused very high levels of ATR expression that probably overwhelm the levels of endogenous ATRIP. Indeed, the control siRNA-treated cells that did show observable HA–ATR foci almost invariably expressed lower levels of HA-ATR than those cells in which HA-ATR localized more uniformly to the nucleoplasm.

Figure 5.

Interaction between ATRIP and RPA–ssDNA is required for accumulation of ATRIP–ATR into bright intranuclear foci. (A) HeLa cells were transfected with an HA–ATR expression vector and either nonspecific control or ATRIP siRNA. Indirect immunofluorescence was performed with antibodies to HA after exposing the cells to IR or HU. Cells were scored as having foci if there were five or more clearly defined foci per cell. (B) Phoenix derivatives of human embryonic kidney 293 cells were transfected with vectors expressing FLAG-ATRIP or FLAG-ATRIP missing either the first 107 amino acids (108–791) or the last 683 amino acids (1–107). These expression constructs also contained a heterologous nuclear localization signal to ensure that these proteins are localized to the nucleus. Cells were lysed and incubated with beads bound to single-stranded DNA that had either been coated with recombinant RPA (+) or mock coated (-). After extensive washing, proteins bound to the beads were denatured and separated by SDS-PAGE followed by blotting with the FLAG antibody. TCL is 5% of the lysate used in the pull down. (C) U20S cells stably expressing HA-ATRIP108-791 missing the first 107 amino acids were examined by indirect immunofluorescence by using antibodies to HA and counterstained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole to visualize the nucleus. (D) Cells expressing either NLS-HA-ATRIP or NLS-HA-ATRIP108-791, which contain a heterologous NLS, were left untreated, exposed to ionizing radiation, or treated with HU and then fixed and stained with HA antibodies followed by a FITC-conjugated secondary antibody. Representative cell images are shown.

To test more directly whether the ATRIP–RPA–ssDNA interaction was required for proper ATRIP–ATR localization, we mapped the domain on ATRIP that is necessary for the RPA–ssDNA interaction. We found that an ATRIP protein lacking the first 107 amino acids was incapable of binding to ssDNA coated with RPA (Figure 5B). This region of ATRIP is sufficient for the ATRIP–RPA–ssDNA interaction because amino acids 1–107 alone associate with RPA–ssDNA. These experiments were performed with epitope-tagged ATRIP constructs that also contain a heterologous nuclear localization signal to ensure that the truncated proteins were both expressed in the same cellular compartment.

U2OS cells expressing HA-ATRIP108-791 missing the first 107 amino acids were generated by retroviral infection, and we found that this ATRIP mutant localizes predominantly in the cytoplasm (Figure 5C) and also failed to complement loss of endogenous ATRIP for Chk1S345 phosphorylation after UV treatment (our unpublished data). There is no predicted nuclear localization signal within the human ATRIP protein. It is unlikely that RPA binding is required to localize ATRIP to the nucleus because we did not observe any loss of endogenous ATRIP from the nucleus in cells treated with siRNA targeting RPA (our unpublished data). There may be a noncanonical nuclear localization signal within amino acids 1–107. This region has two short stretches of basic amino acids and is rich in proline residues.

To test whether an ATRIP protein that cannot bind to RPA but does localize to the nucleus can functionally complement for deletion of endogenous ATRIP, we added a heterologous nuclear localization signal to make an NLS–HA–ATRIP108-791 protein. NLS-HA-ATRIP108-791 does bind to ATR, suggesting that the protein is folded properly (our unpublished data). Although NLS-HA-ATRIP108-791 is localized to the nucleus, it is impaired in its ability to accumulate in foci after DNA damage (Figure 5D). After IR or HU treatment, we were only able to detect small, faint NLS-HA-ATRIP108-791 foci in a small percentage of cells (11 and 7%, respectively), in contrast to the large, bright foci that NLS–HA–ATRIP full-length forms (Table 1). Figure 5D illustrates that the cells that do exhibit NLS-HA-ATRIP108-791 foci after HU and IR treatment have a reduced number of less intensely staining foci compared with full-length NLS-HA-ATRIP. These faint NLS–HA–ATRIP108-791 foci were best visualized in cells expressing low amounts of NLS–HA–ATRIP108-791 protein. We interpret this result to indicate that RPA–ssDNA binding is required for ATRIP to accumulate to high levels at sites of DNA damage or replication stress.

Table 1.

Accumulation of wild-type and mutant ATRIP proteins in nuclear foci

| Protein | Damage | Type I foci (%) | Type II foci (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NLS-HA-ATRIP | None | 0.3 ± 0.6 | 0.7 ± 0.6 |

| NLS-HA-ATRIP108-791 | None | 0 ± 0 | 0.7 ± 0.6 |

| NLS-HA-ATRIP | HU | 55 ± 12 | 2.3 ± 0.6 |

| NLS-HA-ATRIP108-791 | HU | 0 ± 0 | 7.3 ± 3.8 |

| NLS-HA-ATRIP | IR | 68 ± 4 | 2.0 ± 1.0 |

| NLS-HA-ATRIP108-791 | IR | 0 ± 0 | 11.3 ± 1.2 |

Cells containing NLS-HA-ATRIP or NLS-HA-ATRIP 108–791 were treated with 1 mM HU or 8 Gy IR and then processed for immunofluorescence by using the HA antibody. Type I foci were defined as large and bright foci, whereas type II foci were defined as small and faint. Examples of these foci types are shown in Figure 5D. The percentage of cells containing >5 foci is indicated.

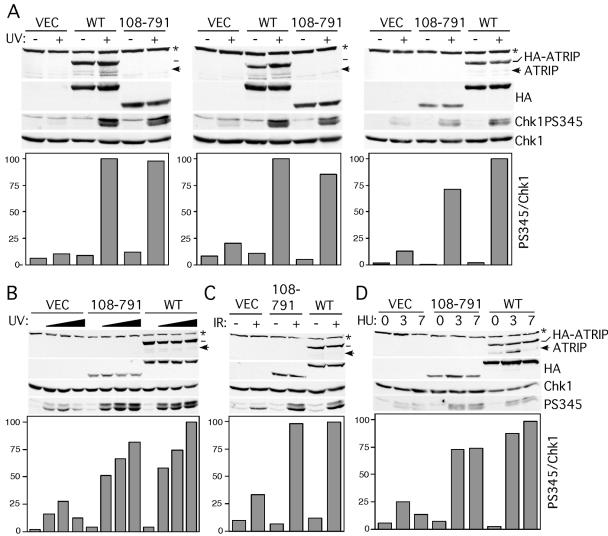

The ATRIP–RPA–ssDNA Interaction Is Not Essential for ATR–ATRIP-dependent Chk1 Phosphorylation

We tested whether ATRIP binding to RPA–ssDNA and stable localization to foci are required for ATRIP-dependent Chk1 S345 phosphorylation by replacing endogenous ATRIP with NLS-HA-ATRIP108-791 or NLS-HA-ATRIP full length. The expression level of NLS-HA-ATRIP and NLS-HA-ATRIP108-791 is approximately two- to threefold higher than endogenous levels before siRNA treatment. ATRIP is required for Chk1S345 phosphorylation in response to UV, HU, or IR because cells expressing only the vector have greatly diminished Chk1S345 phosphorylation compared with cells expressing NLS–HA–ATRIP full-length protein (Figure 6, A–D). Surprisingly, NLS-HA-ATRIP108-791 complemented the loss of endogenous ATRIP almost as well full-length ATRIP as measured by Chk1S345 phosphorylation 2 h after UV treatment (Figure 6A). We created three independent cell lines expressing either vector alone, full-length ATRIP, or ATRIP108-791 to confirm these results. Although there was a small decrease (<25% difference) in Chk1S345 phosphorylation in two of the three cell lines, this correlated with these cells expressing less total NLS-HA-ATRIP108-791 than wild-type ATRIP (Figure 6A). UV dose–response and time-course experiments also revealed minimal differences in Chk1 S345 phosphorylation between NLS–HA–ATRIP108-791 and NLS–HA–ATRIP full-length cells (Figure 6B). Chk1 also is phosphorylated in the NLS–HA–ATRIP108-791-expressing cells after IR treatment and 3 and 7 h after HU treatment to similar levels as in cells expressing wild-type ATRIP (Figure 6, C and D). Chk1 phosphorylation in the NLS–HA–ATRIP-expressing cells cannot be due to an inability to deplete endogenous ATRIP in these cells because blotting with an N-terminal ATRIP antibody (directed at amino acids 1–107) demonstrates that endogenous ATRIP is efficiently eliminated. The siRNA is directed toward a region of the ATRIP mRNA that is completely deleted in the ATRIP 108-791 mutant, eliminating any possibility of competition between the exogenous and endogenous mRNAs.

Figure 6.

Binding to RPA–ssDNA is not essential for ATR–ATRIP-dependent Chk1 phosphorylation. U2OS cells expressing no cDNA (vector), NLS-HA-ATRIP (WT), or NLS-HA-ATRIP108-791 (108-791) were transfected with ATRIP siRNA to remove endogenous ATRIP. The wild-type cDNA was made immune to the ATRIP siRNA by mutations of wobble base pairs in the target sequence. The target sequence is completely deleted in the ATRIP108-791 mRNA. Cells were either mock treated (-) or treated with (A) 30 J/m2 of UV light and then incubated for 2 h; (B) 0, 10, 30, or 60 J/m2 of UV; (C) 8 Gy of IR; or (D) 1 mM HU for 0, 3, or 7 h. Cell lysates were separate by SDS-PAGE and blotted with antibodies to HA-ATRIP, Chk1, or phospho-S345-specific antibodies to Chk1. The bar graphs are quantitations of the Chk1 phosphorylation data in which the Chk1 P-S345 signal was divided by the total Chk1 signal. All values were compared with the value obtained in the damaged NLS–HA–ATRIP (WT)-expressing cells, which was set at 100%. Three independent sets of cell lines were created and analyzed in A to illustrate the variability in the assay.

Thus, the first 107 amino acids of ATRIP represents a DNA damage-sensing domain that functions to bind RPA-coated single-stranded DNA that is generated as an intermediate in response to DNA damage and stalling of replication forks. This binding is required to accumulate large amounts of ATRIP at intranuclear foci, but surprisingly, is largely unimportant for ATR–ATRIP-dependent Chk1 phosphorylation.

DISCUSSION

ATM and ATR are both primary responders to DNA damage, but these kinases seem to be activated differently. ATM is activated efficiently by double strand breaks but not by most other types of genotoxic lesions, whereas ATR is activated by all genotoxic stresses but usually requires ongoing replication for its activity. Our data indicate that ATRIP contains a stress-sensing domain that binds RPA–ssDNA. This RPA–ssDNA binding domain is essential for accumulation of ATRIP at sites of DNA damage or stalled replication forks. However, it is neither sufficient for this recruitment nor absolutely necessary for ATRIP–ATR-dependent Chk1 phosphorylation. Thus, the essential function of ATRIP in ATR-dependent Chk1 activation is not to bind to RPA–ssDNA. Although not essential for Chk1 phosphorylation, the RPA-dependent stable accumulation of ATRIP–ATR in intranuclear foci may be important for ATR recognition of other substrates or for some other aspect of ATR function.

Our data are consistent with several observations that also suggest that the RPA–ssDNA–ATRIP recruitment model is insufficient to explain ATR activation. DDC2 localization to damage-induced foci is Mec1 (the S. cerevisiae ATR orthologue) dependent (Melo et al., 2001). In addition, DDC2 can bind directly to double strand breaks without RPA, and this binding was genetically linked to Mec1 activation (Rouse and Jackson, 2002). ATR binds directly to DNA with a preference for DNA containing UV damage (Unsal-Kacmaz et al., 2002). Cut5, a homolog of human TOPBP1, is required for ATR recruitment to chromatin in Xenopus extracts (Parrilla-Castellar and Karnitz, 2003). Kinase-inactive mutants of ATR do not localize to intranuclear foci efficiently after DNA damage (Barr et al., 2003). An unidentified protein is required for an RPA-independent association of ATR–ATRIP with DNA (Bomgarden et al., 2004). The ATR protein alone or an ATR–ATRIP complex was reported to bind to naked or RPA-covered ssDNA with comparable affinities (Unsal-Kacmaz and Sancar, 2004). Finally, ATR was reported to be activated toward at least some substrates independently of RPA (Dodson et al., 2004). All of these results seem to be inconsistent with at least the simplest forms of the ssDNA–RPA recruitment model for ATR–ATRIP activation and support our conclusion that the ATRIP-RPA–ssDNA interaction is neither sufficient for ATRIP–ATR localization to sites of DNA damage nor essential for ATR activation.

ATR and ATRIP Interaction Domains

We mapped the ATRIP interaction domain on ATR to a 316-amino acid region at the N terminus of ATR. Although ATR has extensive homology to ATM, this region is not conserved between the two proteins, providing an explanation for why ATRIP does not bind to ATM. ATRIP has at least two domains—a C-terminal ATR interaction domain and an N-terminal RPA–ssDNA interaction domain. These results are consistent with studies by Itakura et al. (2004). ATRIP amino acids 641–726 are sufficient to interact with the N terminus of ATR in a yeast-two hybrid assay. However, deletion of the first 217 amino acids of ATRIP prevented it from coimmunoprecipitating with full-length ATR when both are expressed in human cells (Cortez et al., 2001). ATRIP 1-217 did not bind to ATR in either the yeast or mammalian systems. One explanation of these results is that an N-terminal region of ATRIP may be required to promote a stable interaction between the C-terminal region of ATRIP and ATR. Indeed, we have recently observed that the ATRIP coiled-coil domain between amino acids 108–217 mediates ATRIP oligomerization, and oligomerization is necessary for ATRIP to form a stable complex with ATR in mammalian cells (H. B. and D. C., unpublished data). Thus, the ATRIP coiled-coil domain promotes a quaternary structure that allows a stable association with ATR in which ATRIP residues 641–726 contact ATR residues 30–346. ATRIPΔ11 can form oligomers with full-length ATRIP (Ball and Cortez, unpublished data), which may explain the small amount that can be recruited into complexes with ATR (Figure 2B).

The ATRIPΔ11 splice variant message is expressed in all cell types that we have examined. Because ATRIPΔ11 does not bind to ATR but retains the ability to bind to RPA–ssDNA, high-level expression of this protein might be expected to act as a dominant-interfering mutant toward ATR signaling. However, we have successfully created stable cell lines expressing ATRIPΔ11 at levels at least three- to fivefold higher than endogenous full-length ATRIP without observing a significant phenotype either before or after exposure of cells to genotoxic stress unless endogenous ATRIP is depleted. Furthermore, we have seen no regulation of the expression levels of this transcript relative to the full-length ATRIP message. We believe ATRIPΔ11 may be an improperly spliced transcript that plays no functional role in ATR signaling.

Nuclear Localization of ATRIP

The first 107 amino acids of ATRIP are necessary and sufficient to bind to RPA–ssDNA. Deletion of this domain prevents proper subcellular localization. ATRIP lacking this region is mainly located in the cytoplasm unless a heterologous nuclear localization signal is added to it. There is no predicted nuclear localization signal in this region or anywhere else in ATRIP, so it is unclear how ATRIP localizes to the nucleus. ATR does have a predicted nuclear localization signal (NLS) directly after the ATRIP interaction domain. However, ATRIP 107-791 binds to ATR, so ATR binding cannot be sufficient for ATRIP nuclear localization. One possibility is that RPA binding is essential to localize ATRIP to the nucleus. This seems unlikely because we have not observed any change in the cytoplasm–nuclear localization of ATRIP in RPA-depleted cells (our unpublished data). There are KRR and KRAR basic sequences separated by 19 amino acids starting at amino acid 10 of ATRIP. It will be important to determine whether these sequences functions as an NLS for ATRIP.

The Role of ATR in ATRIP–ATR Localization

Our data clearly indicate that ATRIP is required for ATR localization to intranuclear foci (Figure 5A). However, ATR also is required for proper ATRIP localization. The ATRIPΔ11 protein is severely impaired in its ability to localize to foci after both HU treatment and ionizing radiation. Loss of ATR also significantly reduces the ability of full-length ATRIP to form foci. Based on the ATRIPΔ11 localization studies, we had expected a more complete loss of full-length ATRIP foci in the ATR siRNA-treated cells. There are several explanations for why it was not more complete. First, siRNA to ATR did not completely deplete ATR. Second, siRNA against ATR consistently increased the percentage of undamaged cells containing ATRIP foci. This may be because reduction in ATR levels in some cells was sufficient to cause replication problems but insufficient to prevent at least some of the ATRIP protein from localizing to foci. Finally, ATR may play a catalytic role for ATRIP localization that would require nearly complete elimination of the ATR protein from cells before a defect in ATRIP localization would become apparent. The observation that a kinase-defective ATR protein does not properly localize to foci supports this idea (Barr et al., 2003).

Our data are consistent with data from S. cerevisiae that showed Mec1 is required for DDC2 localization to sites of DNA damage (Melo et al., 2001) but inconsistent with the lack of requirement for Rad3 to localize Rad26 in S. pombe (Wolkow and Enoch, 2003). At present, it is unclear why ATR is required for ATRIP localization. One possibility is that ATR makes important contacts with DNA. Human ATR contains a weak, non-sequence-specific DNA binding activity, suggesting that an ATR–DNA interaction may be important (Unsal-Kacmaz et al., 2002; Zou and Elledge, 2003; Bomgarden et al., 2004). However, Xenopus ATR does not seem to bind to chromatin without ATRIP and RPA (Costanzo et al., 2003; Kumagai et al., 2004). Nonetheless, the ATRIPΔ11 protein conclusively demonstrates that ATRIP does not localize efficiently to DNA damage-induced foci without binding to ATR.

Functional Considerations of the ATRIP–RPA–ssDNA Interaction

Current models of ATR activation postulate that it must be recruited to sites of DNA damage. The focal localization of ATR–ATRIP complexes after genotoxic stress has been used as an assay for the recruitment and activation of ATR at DNA lesions. Furthermore, the clear involvement of RPA–ssDNA as an intermediate in checkpoint signaling and the ability of ATRIP to bind to RPA–ssDNA strongly suggested that ATRIP functions to promote ATR activation by recruiting it to RPA–ssDNA (You et al., 2002; Costanzo and Gaiter, 2003; Lee et al., 2003; Zou and Elledge, 2003). Yet, we have now demonstrated that an ATRIP mutant that cannot bind to RPA–ssDNA can still promote ATR activation toward Chk1.

To reconcile these observations, we suggest that there are several mechanisms that initially function to promote localization of ATR to DNA lesions in addition to ATRIP binding to RPA-coated ssDNA. This localization is dependent on both ATRIP and ATR functions. Although accumulation into bright intranuclear foci is dependent on ATRIP binding to RPA–ssDNA, this is a poor assay for recruitment of ATR–ATRIP to sites of DNA damage. The number of molecules that need to accumulate together to visualize a foci by indirect immunofluorescence is larger than that required for Chk1 phosphorylation. ATRIP binding to RPA–ssDNA is important for accumulation of ATRIP into bright foci, but it is not necessarily essential to recruit the ATRIP–ATR complex to DNA lesions or for Chk1 phosphorylation. Indeed, the ATRIPΔ11 protein demonstrates that there are important RPA-independent mechanisms that promote ATRIP recognition of DNA damage. We recently demonstrated that ATRIP binds to the MCM7 protein (Cortez et al., 2004) and MCM7 was demonstrated to be required for localization of ATR–ATRIP into DNA damage-induced foci (Tsao et al., 2004), suggesting one possible alternative means of localizing ATRIP–ATR to sites of stalled replication forks.

It seems unlikely that the RPA–ssDNA binding domain on ATRIP and the accumulation of ATRIP into bright nuclear foci would serve no purpose. The ATRIP–RPA–ssDNA interaction may be essential to prolong ATR activation or some other quantitative aspect of ATR activation that is not measurable in our Chk1 phosphorylation assay. It also may be important for ATR to recognize substrates other than Chk1. Another formal possibility is that there may be a second RPA–ssDNA binding domain on ATRIP that is not sufficient for an in vitro interaction between ATRIP108-791 and RPA but is strong enough to bring this mutant protein to RPA–ssDNA in living cells when it is expressed at levels approximately two- to threefold higher than endogenous ATRIP.

RPA-coated ssDNA is essential for ATR activation even though the ATRIP–RPA–ssDNA interaction is not. Several studies in yeast, Xenopus, and humans have indicated that RPA–ssDNA is a necessary intermediate in the checkpoint response. In addition to binding to ATRIP, RPA-coated ssDNA is required for Rad17 and Hus1 to associate with chromatin (You et al., 2002; Lee et al., 2003; Zou et al., 2003). Thus, it will be important to determine how Rad17 recognizes RPA and whether this interaction is essential for Chk1 phosphorylation.

Conclusions

The N terminus of ATRIP is a DNA damage-sensing domain that binds to RPA–ssDNA and helps accumulate the ATR–ATRIP complex at sites of DNA damage and stalled replication forks. However, the ATRIP–RPA–ssDNA interaction is neither sufficient for ATRIP relocalization after genotoxic stress nor essential for ATR–ATRIP–dependent activation toward Chk1.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dan Liebler and Amy Ham (Vanderbilt Proteomics Laboratory) for assistance with mass spectrometry. We thank Walter Chazin and Melissa Stauffer for the His-RPA construct, and Curtis Thorne for assistance with the yeast two-hybrid screens. This work was supported by National Cancer Institute grants K01CA93701 and R01CA102729 to D. C. D. C. also is supported by the Pew Scholars Program in the Biological Sciences sponsored by the Pew Charitable Trusts. H. B. is supported by training grant T32 CA78136. The Vanderbilt Center in Molecular Toxicology (National Institutes of Health grant P30ES00267-38) helped support the mass spectrometry used to identify the ATRIPΔ11 protein.

This article was published online ahead of print in MBC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E04-11-1006) on March 2, 2005.

Abbreviations used: ATM, ataxia-telangiectasia mutated; ATR, ATM and Rad3 related; HU, hydroxyurea; IR, ionizing radiation; NLS, nuclear localization signal; RPA, replication protein A; ssDNA, single-stranded DNA.

References

- Abraham, R. T. (2001). Cell cycle checkpoint signaling through the ATM and ATR kinases. Genes Dev. 15, 2177-2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr, S. M., Leung, C. G., Chang, E. E., and Cimprich, K. A. (2003). ATR kinase activity regulates the intranuclear translocation of ATR and RPA following ionizing radiation. Curr. Biol. 13, 1047-1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bomgarden, R. D., Yean, D., Yee, M. C., and Cimprich, K. A. (2004). A novel protein activity mediates DNA binding of an ATR-ATRIP complex. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 13346-13353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, E. J., and Baltimore, D. (2000). ATR disruption leads to chromosomal fragmentation and early embryonic lethality. Genes Dev. 14, 397-402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortez, D., Glick, G., and Elledge, S. J. (2004). Minichromosome maintenance proteins are direct targets of the ATM and ATR checkpoint kinases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 10078-10083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortez, D., Guntuku, S., Qin, J., and Elledge, S. J. (2001). ATR and ATRIP: partners in checkpoint signaling. Science 294, 1713-1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costanzo, V., and Gautier, J. (2003). Single-strand DNA gaps trigger an ATR- and Cdc7-dependent checkpoint. Cell Cycle 2, 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costanzo, V., Shechter, D., Lupardus, P. J., Cimprich, K. A., Gottesman, M., and Gautier, J. (2003). An ATR- and Cdc7-dependent DNA damage checkpoint that inhibits initiation of DNA replication. Mol. Cell 11, 203-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dart, D. A., Adams, K. E., Akerman, I., and Lakin, N. D. (2004). Recruitment of the cell cycle checkpoint kinase ATR to chromatin during S-phase. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 16433-16440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodson, G. E., Shi, Y., and Tibbetts, R. S. (2004). DNA replication defects, spontaneous DNA damage, and ATM-dependent checkpoint activation in replication protein A-deficient cells. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 34010-34014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, R. J., Bentley, N. J., and Carr, A. M. (1999). A Rad3-Rad26 complex responds to DNA damage independently of other checkpoint proteins. Nat. Cell. Biol. 1, 393-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hekmat-Nejad, M., You, Z., Yee, M. C., Newport, J. W., and Cimprich, K. A. (2000). Xenopus ATR is a replication-dependent chromatin-binding protein required for the DNA replication checkpoint. Curr. Biol. 10, 1565-1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itakura, E., Takai, K. K., Umeda, K., Kimura, M., Ohsumi, M., Tamai, K., and Matsuura, A. (2004). Amino-terminal domain of ATRIP contributes to intranuclear relocation of the ATR-ATRIP complex following DNA damage. FEBS Lett. 577, 289-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James, P., Halladay, J., and Craig, E. A. (1996). Genomic libraries and a host strain designed for highly efficient two-hybrid selection in yeast. Genetics 144, 1425-1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai, A., Kim, S. M., and Dunphy, W. G. (2004). Claspin and the activated form of ATR-ATRIP collaborate in the activation of Chk1. J. Biol. Chem. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lee, J., Kumagai, A., and Dunphy, W. G. (2003). Claspin, a Chk1-regulatory protein, monitors DNA replication on chromatin independently of RPA, ATR, and Rad17. Mol. Cell 11, 329-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisby, M., Barlow, J. H., Burgess, R. C., and Rothstein, R. (2004). Choreography of the DNA damage response: spatiotemporal relationships among checkpoint and repair proteins. Cell 118, 699-713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupardus, P. J., Byun, T., Yee, M. C., Hekmat-Nejad, M., and Cimprich, K. A. (2002). A requirement for replication in activation of the ATR-dependent DNA damage checkpoint. Genes Dev. 16, 2327-2332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo, J. A., Cohen, J., and Toczyski, D. P. (2001). Two checkpoint complexes are independently recruited to sites of DNA damage in vivo. Genes Dev. 15, 2809-2821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael, W. M., Ott, R., Fanning, E., and Newport, J. (2000). Activation of the DNA replication checkpoint through RNA synthesis by primase. Science 289, 2133-2137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paciotti, V., Clerici, M., Lucchini, G., and Longhese, M. P. (2000). The checkpoint protein Ddc2, functionally related to S. pombe Rad26, interacts with Mec1 and is regulated by Mec1-dependent phosphorylation in budding yeast. Genes Dev. 14, 2046-2059. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrilla-Castellar, E. R., and Karnitz, L. M. (2003). Cut5 is required for the binding of Atr and DNA polymerase alpha to genotoxin-damaged chromatin. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 45507-45511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouse, J., and Jackson, S. P. (2000). LCD 1, an essential gene involved in checkpoint control and regulation of the MEC1 signalling pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 19, 5801-5812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouse, J., and Jackson, S. P. (2002). Lcd1p recruits Mec1p to DNA lesions in vitro and in vivo. Mol. Cell 9, 857-869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shechter, D., Costanzo, V., and Gautier, J. (2004). ATR and ATM regulate the timing of DNA replication origin firing. Nat. Cell. Biol. 6, 648-655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiloh, Y. (2001). ATM and ATR: networking cellular responses to DNA damage. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 11, 71-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stauffer, M. E., and Chazin, W. J. (2004). Physical interaction between replication protein A and Rad51 promotes exchange on single-stranded DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 25638-25645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tercero, J. A., Longhese, M. P., and Diffley, J. F. (2003). A central role for DNA replication forks in checkpoint activation and response. Mol. Cell 11, 1323-1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsao, C. C., Geisen, C., and Abraham, R. T. (2004). Interaction between human MCM7 and Rad17 proteins is required for replication checkpoint signaling. EMBO J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Uchiyama, M., Galli, I., Griffiths, D. J., and Wang, T. S. (1997). A novel mutant allele of Schizosaccharomyces pombe rad26 defective in monitoring S-phase progression to prevent premature mitosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 3103-3115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unsal-Kacmaz, K., Makhov, A. M., Griffith, J. D., and Sancar, A. (2002). Preferential binding of ATR protein to UV-damaged DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 6673-6678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unsal-Kacmaz, K., and Sancar, A. (2004). Quaternary structure of ATR and effects of ATRIP and replication protein A on its DNA binding and kinase activities. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 1292-1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakayama, T., Kondo, T., Ando, S., Matsumoto, K., and Sugimoto, K. (2001). Pie1, a protein interacting with Mec1, controls cell growth and checkpoint responses in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 755-764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y., Cortez, D., Yazdi, P., Neff, N., Elledge, S. J., and Qin, J. (2000). BASC, a super complex of BRCA1-associated proteins involved in the recognition and repair of aberrant DNA structures. Genes Dev. 14, 927-939. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolkow, T. D., and Enoch, T. (2003). Fission yeast Rad26 responds to DNA damage independently of Rad3. BMC Genet. 4, 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You, Z., Kong, L., and Newport, J. (2002). The role of single-stranded DNA and polymerase alpha in establishing the ATR, Hus1 DNA replication checkpoint. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 27088-27093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou, L., and Elledge, S. J. (2003). Sensing DNA damage through ATRIP recognition of RPA-ssDNA complexes. Science 300, 1542-1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou, L., Liu, D., and Elledge, S. J. (2003). Replication protein A-mediated recruitment and activation of Rad17 complexes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 13827-13832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]