Abstract

We have observed maternal transmission ratio distortion (TRD) in favor of DDK alleles at the Ovum mutant (Om) locus on mouse chromosome 11 among the offspring of (C57BL/6 × DDK) F1 females and C57BL/6 males. Although significant lethality occurs in this backcross (∼50%), differences in the level of TRD found in recombinant vs. nonrecombinant chromosomes among offspring argue that TRD is due to nonrandom segregation of chromatids at the second meiotic division, i.e., true meiotic drive. We tested this hypothesis directly, by determining the centromere and Om genotypes of individual chromatids in zygote stage embryos. We found similar levels of TRD in favor of DDK alleles at Om in the female pronucleus and TRD in favor of C57BL/6 alleles at Om in the second polar body. In those embryos for which complete dyads have been reconstructed, TRD was present only in those inheriting heteromorphic dyads. These results demonstrate that meiotic drive occurs at MII and that preferential death of one genotypic class of embryo does not play a large role in the TRD.

WHEN females of the DDK inbred mouse strain are mated with males of many other inbred strains, up to 95% of the resulting embryos die prior to the completion of preimplantation development (Wakasugi 1974). The reciprocal crosses, between DDK males and non-DDK females, are fully viable and fertile (Wakasugi 1974). This unusual system of polar, preimplantation lethality has been termed the “DDK syndrome” (Babinet et al. 1990). Ovary transfer experiments (Wakasugi 1973), genetic experiments using F1 backcrosses (Wakasugi 1974), and pronuclear transfer experiments (Mann 1986; Renard and Babinet 1986) all indicate that the preimplantation lethality results from the interaction of a DDK ovum gene product with a non-DDK paternal gene.

The failure to segregate the gene encoding the DDK maternal product and the lethally interacting paternal gene among a modest number of F1 backcross offspring led Wakasugi (1974) to propose that the genetic factors responsible for DDK syndrome resided at the same locus. Consistent with this interpretation, both the maternal factor and the lethally interacting paternal gene segregate as a single locus (Ovum mutant, Om) and have been mapped to a small region of mouse chromosome 11 (Baldacci et al. 1996; Pardo-Manuel de Villena et al. 1997; F. Pardo-Manuel de Villena and C. Sapienza, unpublished results).

Two of the four F1 backcrosses, that between DDK females and (C57BL/6 × DDK) F1 males and that between (C57BL/6 × DDK) F1 females and C57BL/6 males, exhibit intermediate levels of lethality (Wakasugi 1974; Pardo-Manuel de Villena et al. 1999). We observed transmission ratio distortion (TRD, defined as a statistically significant departure from the Mendelian ratio expected) in favor of DDK alleles at the Om locus in both of the semilethal F1 backcrosses. In the case of the backcross between DDK females and F1 males, the high level of TRD (>80%) was due to death of embryos inheriting the lethally interacting “alien” (C57BL/6) paternal allele from their F1 fathers. [In fact, we mapped the location of Om to chromosome 11 by determining the position of maximum TRD in surviving offspring from this backcross (Sapienza et al. 1992).]

We also observed TRD at Om among the offspring of (C57BL/6 × DDK) F1 females and C57BL/6 males in multiple independent experiments (Pardo-Manuel de Villena et al. 1996, 1997, 2000a,b). The level of TRD in favor of maternal DDK alleles in this backcross (as well as those involving additional strains of males; Pardo-Manuel de Villena et al. 2000a; Kim et al. 2005) was modest, ranging from 56 to 62.8% in individual experiments (summarized in Pardo-Manuel de Villena et al. 2000a). Although there was significant embryonic death in the backcross of (C57BL/6 × DDK) F1 females to C57BL/6 males, we also considered the possibility that TRD was not due to preferential loss of offspring of one genotypic class. We formulated a genetic test, based on the expectations of a single-locus lethality model and an alternative model of nonrandom segregation of chromosomes during the first or second meiotic division (Pardo-Manuel de Villena et al. 2000a). We found that the level of TRD differs among surviving offspring, being significantly greater when they inherit a recombinant (nonparental) than a nonrecombinant (parental) chromosome 11 (Pardo-Manuel de Villena et al. 2000a). This observation was not consistent with the expectations of a single-locus lethality model but was consistent with the possibility that TRD at Om was due to meiotic drive at the second meiotic division.

We have tested the meiotic drive hypothesis directly, by removing the female pronucleus and second polar body from zygote stage embryos and determining the genotype of the single chromatid contained in each meiotic product at markers linked closely to the centromere and to Om. We find that TRD is present at the zygote stage and occurs reciprocally and to the same level in the maternal pronucleus and second polar body. Furthermore, TRD occurs only in dyads (the pair of chromatids that compose one chromosome of a bivalent) in which one chromatid has recombined between the centromere and Om; i.e., TRD occurs only in ova in which it is possible to make a segregational choice between DDK and C57BL/6 alleles at Om at meiosis (M)II. The results of this experiment are consistent with the interpretation that nonrandom segregation of chromosomes between the oocyte and second polar body is responsible for TRD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mouse crosses and embryo collection:

The DDK inbred strain was a gift of Charles Babinet (Institute Pasteur, Paris) and has been maintained in a specific pathogen-free facility at Temple University Medical School since 1997. C57BL/6J, PERA/EiJ, and PANCEVO/EiJ strains were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). In all crosses described in the text, the dam is listed first and sire second. (C57BL/6J × DDK) F1 females (8–16 weeks old, bred in house) in natural estrus were set up for mating with C57BL/6J, PERA/EiJ or PANCEVO/EiJ males in the afternoon. All of the males used as sires had been tested previously for TRD in favor of the inheritance of DDK alleles at Om among their offspring and similar levels of TRD favoring the transmission of the maternal DDK allele at Om are observed in all three crosses (Pardo-Manuel de Villena et al. 2000a; Kim et al. 2005). Females were checked for copulation plugs the next morning and mated females were killed before noon and their oviducts were collected into M2 medium (Sigma, St. Louis) containing 100 units/ml of hyaluronidase (ICN, Aurora, OH) at room temperature. The cumulus-oocyte complexes were released from the oviducts by rupturing the ampulla of each oviduct with sharp tweezers. Adherent cumulus cells were removed by repeated pipetting through a small-bore glass pipette after 5 min of enzyme treatment and one-cell embryos were washed and cultured in CZB medium (Chatot et al. 1989) for 2–5 hr before microsurgery. CZB culture drops were equilibrated in a humidified incubator (37°, 5% CO2 in air) for at least 1 hr before embryo culture.

Micromanipulation and DNA preparation:

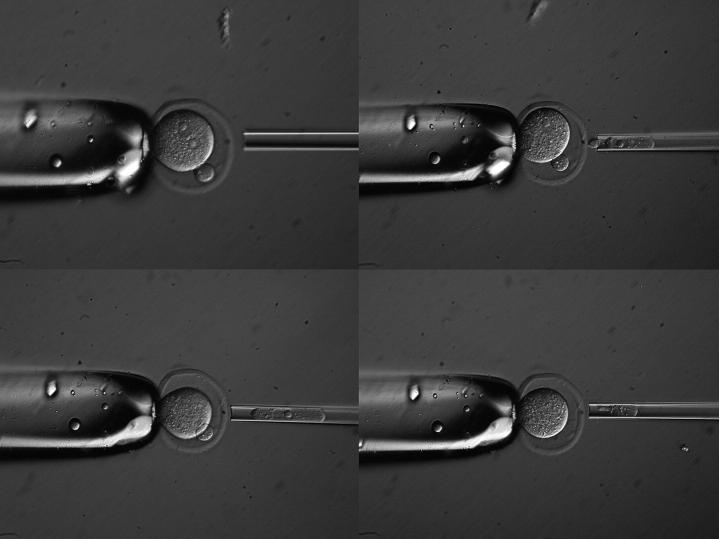

One-cell embryos were transferred into CZB medium containing 10 μg/ml cytochalasin B and 0.4 μg/ml demecolcine drop and placed in the incubator for 20–30 min before microsurgery. Enucleation was performed in M2 medium containing cytochalasin and demecolcine using pipettes of 20-μm outer diameter on a Leitz micromanipulator with Piezo-drill controller PMM-150 (Prime Tech, Ibaraki, Japan). To distinguish between maternal and paternal pronuclei, the embryo was held in such a way that the second polar body was at the one o'clock or five o'clock position and both pronuclei were seen clearly at the same time (Figure 1). The maternal pronucleus was selected as the one closer to the second polar body and smaller in size than the male pronucleus. Each polar body or pronucleus was transferred separately into eight-strip 0.2-ml PCR tubes containing 1 μl of 17-μm sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and 2 μl of 125-μg/ml proteinase K (Holding et al. 1993) overlaid with a drop of paraffin oil and then incubated at 37° overnight followed by 15 min at 95° to inactivate the enzyme.

Figure 1.—

A representative enucleation series. Top left: a zygote positioned so that both maternal and paternal pronuclei are visible, with maternal pronucleus closer to the second polar body. Top right: the embryo after removal of the maternal pronucleus (maternal pronucleus is positioned in the enucleation pipette). Bottom left: the embryo after removal of the paternal pronucleus (in enucleation pipette). Bottom right: the embryo after removal of the second polar body (in enucleation pipette).

Microsurgery was attempted on a total of 378 zygotes. Three hundred ten of the zygotes were from the cross (C57BL/6J × DDK) F1 × C57BL/6J, 40 zygotes were from (C57BL/6J × DDK) F1 × PANCEVO/EiJ, and 28 zygotes were from (C57BL/6J × DDK) F1 × PERA/EiJ. There was no significant difference in the distribution of genotypes at Om between the maternal pronucleus and second polar body among the three strains of males (χ2 = 1.45, P > 0.05); therefore, the data were combined.

The PANCEVO/EiJ and PERA/EiJ strains were selected for use in this experiment because males of these strains had been pretested for TRD among live-born offspring (to determine the paternal Om phenotype of additional strains; Kim et al. 2005). Once significant TRD was demonstrated among the offspring of these males; they (i.e., the same individuals) were used as sires in the present experiment.

Nested PCR and genotype determination:

The genotypes of the samples were determined using nested PCR, as described by El-Hashemite et al. (1997), with minor modifications (see below). Two sets of specific primer pairs (outer and inner primers; Table 1) were designed for each microsatellite marker: D11Mit71, linked closely to the centromere [at position 1.1 cM (http://www.informatics.jax.org/) and physical position 6825228–6825411 (NCBI m33)], and D11Spn1 or D11Spn4. D11Spn1 is at position 47 cM and physical position 81773654–81773802 bp [http://www.ensembl.org/Mus_musculus/ (NCBI m33)] and is very closely linked to Om (Pardo-Manuel de Villena et al. 2000a). D11Spn4 is just proximal to Om (at position 46.5 cM; F. Pardo-Manuel de Villena, unpublished results) and at physical position 81612112–81612303 bp [http://www.ensembl.org/Mus_musculus/ (NCBI m33)]. PCRs with the D11Spn1 marker were not as robust as with the D11Spn4 marker in the PANCEVO/EiJ strain. On days when PANCEVO/EiJ plugs were obtained, the D11Spn4 marker was substituted in all PCRs for that day, including those with pronuclei/polar bodies from C57BL/6J or PERA/EiJ plugs.

TABLE 1.

Primer sequence information for nested PCRs

| Microsatellite marker |

Outer primer | Inner primer | Nested product size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| D11Mit71 | Forward catacctggtagcgtgttcc | tgaccctgtgtaattgtgatcc | |

| Reverse gtagattcaaacacca gtaagtg | aattttcagatgtagccataagcc | 184 | |

| D11Spn1 | Forward cccttgctcttgctgacatct | atagaaccacagcctgtaagcc | |

| Reverse catgtggaaagcgtgcag | tggcaggatgtggattttctccc | 149 | |

| D11Spn4 | Forward cgcgcaacaactttcaatta | gtcttctggaaacctgaaagc | |

| Reverse agctggtgggggtgttagaac | gagaattgagggaaaattgtc | 192 |

PCR amplifications were performed in a Perkin-Elmer 9600 thermal cycler, and reagents were from Roche Applied Science (Indianapolis). Primary reactions used the ∼4 μl of DNA template (single pronucleus or polar body prepared previously) in a total volume of 15 μl. Reactions contained 250 μm each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP), 0.05 units/μl Taq polymerase, and 0.1 μm each outer primer. Cycling conditions were an initial 3-min denaturation at 95°, followed by 25 cycles, each consisting of a 30-sec denaturation at 94°, a 45-sec annealing at 55°, and a 1-min extension at 72°. These 25 cycles were followed by a 7-min extension at 72°. Nested amplifications used 1.2 μl of the primary PCR product as the template in a total reaction volume of 12 μl. Amplifications contained 250 μm each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP), 0.05 units/μl Taq polymerase, and 0.1 μm each inner primer. Nested cycling conditions were as described for the primary amplification, except that 35 cycles were used. Reaction products were subsequently maintained at 4° until they were analyzed by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis.

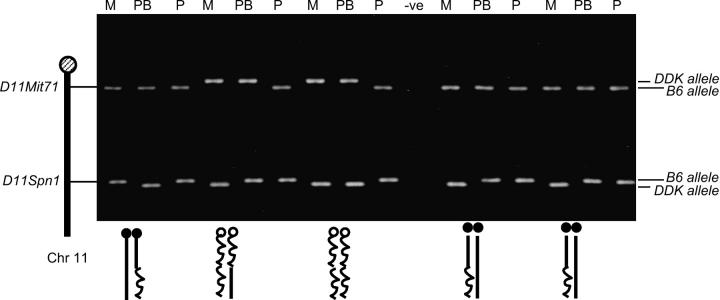

Negative controls were included in each experiment and paternal pronuclei acted as an internal positive control in that DDK alleles should never be amplified. The genotype of each sample at each locus was assigned according to the nested PCR product size difference between C57BL/6J and DDK alleles found in the female pronucleus and second polar body (Figure 2).

Figure 2.—

Representative agarose gel electrophoresis of nested PCR products. PCR templates are pronuclei and second polar bodies. M, maternal pronucleus; PB, polar body; P, paternal pronucleus; −ve, negative control. Genotype on each chromatid is inferred (below gel) by identity of allele (right side of gel) at D11Mit71 (for centromere) and D11Spn1 (for Om). Solid circles, C57BL/6 centromeres; open circles, DDK centromeres; wavy lines, the DDK allele; straight lines, the C57BL/6 allele.

Statistical analysis:

Departure from 1:1 allelic ratios in each comparison class for the predictions of meiotic drive (i.e., reciprocal TRD in female pronuclei and second polar bodies and TRD in heteromorphic dyads) was evaluated using the chi-square test with 1 d.f.

Note on terminology:

The designation of a dyad as “heteromorphic” or “homomorphic” refers only to recombination events between the centromere and Om. Because of the risk of nondisjunction in so-called E0 tetrads, recombination has occurred, in all likelihood, between Om and the telomere on those dyads designated as homomorphic (see Broman et al. 2002; de la Casa-Esperón et al. 2002). Note, also, that dyads composing one nonrecombinant chromatid and one chromatid on which two recombination events have occurred between the centromere and Om are also considered homomorphic for the purposes of the predictions of the genetic model [see Pardo-Manuel de Villena et al. 2000a, Figure 1, for a detailed consideration (provided as supplementary material at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/)]. Finally, we do not intend to imply that the Responder (the locus acted upon by the Distorter to create transmission ratio distortion in this system) and Om are identical, although the two are linked closely (Pardo-Manuel de Villena et al. 2000c).

RESULTS

Reciprocal TRD at Om is observed in the female pronucleus and second polar body:

The female pronucleus, male pronucleus, and second polar body were removed from zygote stage embryos by microsurgery (see materials and methods and Figure 1) and genotypes at the centromere and at Om of each chromatid were inferred by PCR for informative loci linked closely to the centromere and to Om (see materials and methods).

The nested PCRs used proved very robust, and we achieved 86% success in determining all four relevant genotypes; i.e., both the centromere genotype and the Om genotype in both the maternal pronucleus and the second polar body were determined for 326 out of the 378 zygotes tested (a representative example is shown in Figure 2). We also determined the centromere and Om genotypes in >90% of the paternal pronuclei and we did not observe a DDK allele in any case, indicating that confusion of maternal and paternal pronuclei occurred rarely, if at all (see materials and methods).

If the TRD we observed in previous experiments (Pardo-Manuel de Villena et al. 1996, 1997, 2000a,b) occurred as a result of meiotic drive rather than embryonic death associated with the DDK syndrome, TRD should be present at the zygote stage; i.e., there should be more OmDDK alleles than OmC57BL/6 alleles in female pronuclei. To test this prediction we used all maternal pronuclei for which Om genotype was determined successfully (in 353/378 zygotes, or 93% success), regardless of whether the genotype at the centromere or either polar body genotype was determined successfully (Table 2). A significant excess of DDK alleles was found in maternal pronuclei (χ2 = 5.24; P < 0.05, Table 2), consistent with this prediction.

TABLE 2.

InferredOm genotype of individual chromatids segregated to maternal pronuclei or second polar bodies

| No. OmDDK | No. OmC57BL/6 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal pronucleus | 198a | 155 | 353 |

| Second polar body | 159 | 204b | 363 |

| Total | 357 | 359 | 716 |

All successful D11Spn1 or D11Spn4 determinations are shown.

H0: equal transmission of OmDDK and OmC57BL/6 to maternal pronucleus; χ2 = 5.24, P < 0.05.

H0: equal transmission of OmDDK and OmC57BL/6 to second polar body; χ2 = 5.58, P < 0.05.

Our previous genetic data (Pardo-Manuel de Villena et al. 2000a) also predicted that meiotic drive was occurring at the second meiotic division rather than at the first. This hypothesis makes the further prediction that TRD should be present in both the maternal pronucleus and the second polar body, but in opposite directions (Pardo-Manuel de Villena et al. 2000a). To test this prediction we used all of the second polar bodies for which Om genotype was determined successfully (in 363/378 second polar bodies, or 96% success) and the results were, again, consistent with this prediction (χ2 = 5.58; P < 0.05, Table 2). There was significant TRD in favor of DDK alleles in the maternal pronucleus and also significant TRD in favor of C57BL/6 alleles in the second polar body.

TRD is observed only in embryos that contain heteromorphic dyads at MII:

The data in Table 2 demonstrate that TRD was present in the embryos before any lethality due to the DDK syndrome had taken place, indicating that nonrandom segregation of chromatids occurred at MII. If this is the case, then TRD must occur as a result of preferential segregation of the chromatid carrying a DDK allele at Om to the maternal pronucleus and the preferential segregation of the chromatid carrying a C57BL/6 allele to the second polar body. This situation occurs at MII only when the dyad remaining in the ovum after MI is heteromorphic; i.e., there has been a recombination event between the centromere and Om on one chromatid and no recombination event between the centromere and Om on the other (see materials and methods and Pardo-Manuel de Villena et al. 2000a, Figure 1).

We reconstructed the dyad present in the ovum after MI (i.e., successful determination of centromere and Om genotype in both maternal pronucleus and second polar body) in 326 cases (Table 2). There was no evidence of TRD among embryos that inherited a homomorphic maternal dyad, consistent with the interpretation that nonrandom segregation of chromosomes did not take place at MI in this system (49.9 ± 1.9% OmDDK alleles present at MI). There was, however, significant TRD in embryos that inherited a heteromorphic maternal dyad (χ2 = 4.70; P < 0.05, Table 3), consistent with the expectations of meiotic drive at MII.

TABLE 3.

Comparison of female pronuclearOm genotypes in complete dyads

| No. OmDDK in female pronucleus |

No. OmC57BL/6 in female pronucleus |

Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heteromorphic dyads | 156a | 120 | 276 |

| Homomorphic dyads | 24 | 26 | 50 |

| Total | 180 | 146 | 326 |

Homomorphic dyads are those for which the Om genotype is the same in both female pronucleus and second polar body. Heteromorphic dyads are those for which the Om genotype differs between female pronucleus and second polar body.

H0: equal transmission of OmDDK and OmC57BL/6 in heteromorphic dyads; χ2 = 4.70, P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

We tested the hypothesis that TRD at Om occurs as a result of meiotic drive at MII (Pardo-Manuel de Villena et al. 2000a). Our results demonstrate the following: (1) significant TRD in favor of DDK alleles is present at the zygote stage in female pronuclei; (2) significant and reciprocal TRD in favor of C57BL/6 alleles is present in second polar bodies; and (3) significant TRD occurs only in embryos that contain heteromorphic dyads at MII. We stress that the first two conclusions represent independent tests of the meiotic drive hypothesis; if the null hypothesis was that TRD is due to preferential death of embryos carrying OmC57BL/6 alleles, TRD in favor of OmC57BL/6 in second polar bodies is not a predicted result of this experiment. Overall, all three of these results demonstrate that TRD in favor of DDK alleles at Om occurs as a result of nonrandom segregation of chromatids at MII.

We note that the level of TRD observed in zygotes (56.1%, Table 2), as well as the level of reciprocal TRD observed in second polar bodies (56.2%, Table 2), was similar to that observed in live-born offspring (56–62.8%; Pardo-Manuel de Villena et al. 1996, 1997, 2000a,b) and similar to the level of nonrandom segregation of univalent X chromosomes observed in the mouse at MI (62.2%; LeMaire-Adkins and Hunt 2000), as well as the level of TRD observed in both mouse (59.6%) and human (58.7%) female Robertsonian translocation carriers (summarized in Pardo-Manuel de Villena and Sapienza 2001a). The relative quantitative uniformity of these results suggests that some common feature of oocyte meiotic spindle asymmetry is being exploited even though the nonrandom segregation reported here occurs at MII, while the nonrandom segregation of univalent X chromosomes and Robertsonian translocations occurs at MI. Higher levels of maternal TRD (∼80%) have been observed in favor of chromosome 1 containing a large homogeneously staining region (Agulnik et al. 1990); however, preferential segregation of this chromosome appears to occur at both MI and MII so that the exploitation of some common aspect of spindle asymmetry in this system is also not ruled out.

Although we have demonstrated that TRD is present in both zygotes (this report) and live-born offspring (summarized in Pardo-Manuel de Villena et al. 2000a), certain aspects of the zygote data exhibit unexpected characteristics that may not preclude some postzygotic selection against one class of OmC57BL/6/OmC57BL/6 embryo. Table 4 compares the number of parental/nonparental chromosomes observed in live-born offspring (data from Pardo-Manuel de Villena et al. 2000a) with the number of each type found in the maternal pronucleus in the present experiment. Although the two sets of observations do not differ significantly (χ2 = 6.3, 3 d.f., P > 0.05), three aspects of the comparison bear mention: (1) there are significantly more C57BL/6 centromeres than DDK centromeres in the live-born data set (χ2 = 4.37, P < 0.05) but there are not significantly more C57BL/6 centromeres in the zygote data set; (2) the fraction of nonparental chromosomes in the live-born data set is 0.44 ± 0.013, while it is 0.49 ± 0.027 in the zygote data set; and (3) the level of TRD in parental chromosomes and nonparental chromosomes does not differ in the zygote data set while the level of TRD in the nonparentals is significantly higher in the live-born data set (Pardo-Manuel de Villena et al. 2000a). If we use the live-born data set to predict which class of observation is the cause of these three discrepancies, we would conclude that the nonparental chromosome class that has a DDK centromere and a C57BL/6 allele at Om is overrepresented in the zygote data set (i.e., <71 such chromosomes would be predicted on the basis of their relative representation in the live-born data set). If fewer of this nonparental class were observed in the zygote data set, then the fraction of each type of chromosome would more closely approximate that found in the live-born data set: the fraction of the total chromosomes containing C57BL/6 centromeres would be higher, the fraction of nonparental chromosomes would be lower, and the level of TRD in favor of DDK alleles at Om in nonparental chromosomes would be higher. That a smaller fraction of this nonparental chromosome class is found in live-borns vs. zygotes suggests the possibility that some embryonic loss of this genotypic class may occur.

TABLE 4.

Comparison of parental and nonparental chromosomes in live-born offspring and zygotes

| Parental

|

Nonparental

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C57BL/6 | DDK | DDK-C57BL/6 | C57BL/6-DDK | Total | |

| Live-borna | 363 | 476 | 235 | 429 | 1503 |

| Zygotes | 75 | 96 | 71 | 93 | 335 |

| Total | 438 | 572 | 306 | 522 | 1838 |

H0: live-born offspring differ from zygotes; χ2 = 6.3, 3 d.f., P > 0.05. TRD in live-borns = (476 + 429)/1503 = 0.602, χ2 = 62.7, P < 10−6; TRD in zygotes = (96 + 93)/335 = 0.564, χ2 = 5.52, P < 0.05. Fraction of parentals, 0.44 in live-borns, 0.49 in the present experiment; TRD in parentals, 0.57 in live-borns, 0.56 in the present experiment; TRD in nonparentals, 0.65 in live-borns, 0.57 in the present experiment.

Data for live-born offspring were taken from Pardo-Manuel de Villena et al. (2000a).

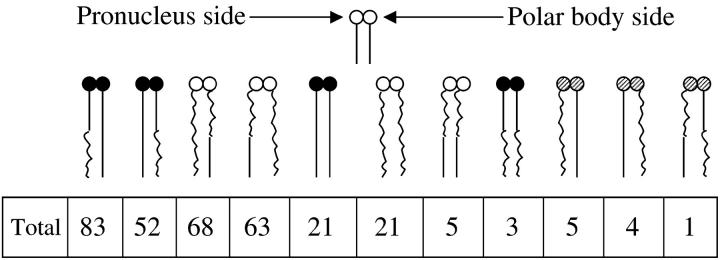

Interestingly, more detailed analysis of complete dyads that contain this particular nonparental chromosome does not rule out this possibility. Figure 3 shows all of the dyads that could be reconstructed on the basis of successful genotypes at both the centromere and Om in both maternal pronuclei and second polar bodies. From the standpoint of being able to choose either the OmC57BL/6 or OmDDK allele at MII, the first four classes and the last three classes are heteromorphic. As stated previously in Table 3, there is significant TRD in favor of DDK alleles in the total of these seven classes of dyad. However, by inspection, there appears to be substantial TRD in those embryos that contain heteromorphic dyads that have C57BL/6 centromeres (first two classes on the left) but little TRD in those that have heteromorphic dyads with DDK centromeres (next two classes), although the difference in the level of TRD is not statistically significant (χ2 = 2.48, P > 0.05). In addition, this interpretation must be tempered by the fact that there is some uncertainty in the precise numbers in each of the first four categories on the left, due to the 10 dyads in the last three classes on the right (Figure 3). These classes represent dyads in which the D11Mit71 genotypes of the second polar body and maternal pronucleus differ. This may occur as a result of recombination between the centromere and D11Mit71 [expected to occur in 1.1% of dyads (http://www.informatics.jax.org/); in Figure 3 they represent 3.1% of dyads] or in instances in which the centromere genotypes truly differ because of premature separation of sister chromatids at MI. Although the frequency at which the latter event occurs is likely to be low (e.g., Hodges et al. 2001), it is not precluded by the number of indeterminate dyads observed. Because of the uncertainty in centromere genotype in these classes, we cannot determine whether the five dyads that segregated DDK alleles at Om to the ovum and C57BL/6 alleles to the second polar body belong in the first class or the third class. Similarly, we cannot determine whether the five dyads that segregated C57BL/6 alleles to the ovum and DDK alleles to the polar body belong in the second class or the fourth class. In the “best” case for the possibility that meiotic drive occurs in both C57BL/6 centromere-containing and DDK centromere-containing dyads, the level of TRD in the C57BL/6 centromere case would be 83:57 and the level of TRD in the DDK centromere dyads would be 73:63. Under the scenario that only C57BL/6 centromere dyads exhibited drive the C57BL/6 centromere dyads could have TRD as high as 88:52 and the DDK centromere dyads could exhibit equal numbers (68:68) of DDK and C57BL/6 alleles at Om.

Figure 3.—

Schematic of complete dyads scored. The dyads were reconstructed after individual testing of maternal pronuclei and second polar bodies. In each dyad, solid circles represent C57BL/6 centromeres, open circles represent DDK centromeres, and hatched circles represent instances in which the maternal pronucleus and second polar body were of different genotype at D11Mit71. (Such instances are interpreted to represent recombination between D11Mit71 and the centromere or premature separation of sister chromatids. It is not possible to infer centromere genotype in either case.) Nonrecombinant (i.e., parental—D11Mit71 and D11Spn1/D11Spn4 genotypes the same) C57BL/6 chromatids are represented as continuous straight lines, nonrecombinant DDK chromatids are represented as continuous wavy lines, recombinant chromatids (i.e., nonparental—D11Mit71 and D11Spn1/D11Spn4 genotypes differ) that carry OmDDK are represented as straight lines adjacent to centromeres and wavy lines below, while recombinant chromatids that carry OmC57BL/6 are represented as wavy lines adjacent to centromeres and straight lines below. The chromatid on the left of each dyad was segregated to the maternal pronucleus, and the chromatid on the right was segregated to the second polar body.

One final note on the potential source of any differences between the live-born data set and the zygote data set is the variable action of X-linked loci that modify the overall level of recombination in F1 females (de la Casa-Esperón et al. 2002). Because this X-linked modifier locus appears sensitive to X-inactivation (de la Casa-Esperón et al. 2002), there could be true differences in the level of recombination observed (the fraction of nonparental chromosomes in Table 4) between the two data sets, depending on the X-inactivation phenotypes of the females used in each set of experiments.

In any case, the data presented here demonstrate, by direct determination of genotypes in the maternal pronucleus and second polar body, that the TRD observed among live-born offspring (Pardo-Manuel de Villena et al. 1996, 1997, 2000a,b; Kim et al. 2005) occurs predominately as a result of nonrandom segregation of chromatids at a single meiotic division in females. Even if there is some level of postzygotic selection against embryos that inherit one class of nonparental chromosome, the data in Table 4 suggest that the contribution of such selection to the overall TRD is minor.

These data are the first example of which we are aware in which nonrandom segregation has been demonstrated directly in a mammal in the absence of a cytologically visible chromosome polymorphism (Agulnik et al. 1990) or aneuploidy (LeMaire-Adkins and Hunt 2000). Nonrandom segregation is demonstrated most strongly for heteromorphic dyads containing a C57BL/6 centromere. In such dyads, DDK alleles at Om were segregated to the ovum, in preference to the polar body, by a margin of 83:52 (61.5%).

Female-based meiotic drive of this magnitude could play a powerful role in changing allele frequencies in natural populations. Comparative evolutionary data indicate that it has been an important force in shaping the mammalian karyotype (Pardo-Manuel de Villena and Sapienza 2001a). However, little is known about the molecular mechanisms involved. Formally, meiotic drive requires an asymmetric meiotic division (one product must be a functional gamete and the other not), functional polarity of the meiotic spindle (there must be an “ovum side” and a “polar body side”), and a functional difference between the chromosomes in their ability to be attached to the ovum side of the spindle vs. the polar body side (Pardo-Manuel de Villena and Sapienza 2001b). In the system we have investigated, it appears that DDK alleles in the Om region enhance the ability of the chromosome to attach to the ovum side of the spindle when paired opposite a C57BL/6 allele at Om. In this regard, we have not observed any apparent morphological differences between chromosomes in MII oocytes from F1 females (G. Wu, unpublished results) or any of the molecular hallmarks of a “neocentromere” in the Om region (i.e., ectopic CenpE staining; G. Wu, unpublished results). Nevertheless, we have confirmed that nonrandom segregation does occur at MII, although the mechanism remains unknown.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH R01GM62537 to C.S. and NIH R01HD43092 to K.E.L.), the National Science Foundation (MCB-0133526 to F.P.M.d.V.), and the Andrew Mellon Foundation (to F.P.M.d.V.).

References

- Agulnik, S. I., A. I. Agulnik and A. O. Ruvinsky, 1990. Meiotic drive in female mice heterozygous for the HSR inserts on chromosome 1. Genet. Res. 55: 97–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babinet, C., V. Richoux, J. L. Guenet and J. P. Renard, 1990 The DDK inbred strain as a model for the study of interactions between parental genomes and egg cytoplasm in mouse preimplantation development. Development S: 81–87. [PubMed]

- Baldacci, P. A., M. Cohen-Tannoudji, C. Kress, S. Pournin and C. Babinet, 1996. A high-resolution map around the locus Om on mouse chromosome 11. Mamm. Genome 7: 114–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broman, K. W., L. B. Rowe, G. A. Churchill and K. Paigen, 2002. Cross over interference in the mouse. Genetics 160: 1123–1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatot, C. L., C. A. Ziomek, B. D. Bavister, J. L. Lewis and I. Torres, 1989. An improved culture medium supports development of random-bred 1-cell mouse embryos in vitro. J. Reprod. Fertil. 86: 679–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Casa-Esperón, E., J. L. Osti., F. Pardo-Manuel de Villena, T. L. Briscoe, J. M. Malette et al., 2002. X chromosome effect on maternal recombination and meiotic drive in the mouse. Genetics 161: 1651–1659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Hashemite, N., D. Wells and J. D. Delhanty, 1997. Single cell detection of beta-thalassaemia mutations using silver stained SSCP analysis: an application for preimplantation diagnosis Mol. Hum. Reprod. 3: 693–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges, C. A., R. LeMaire-Adkins and P. A. Hunt, 2001. Coordinating the segregation of sister chromatids during the first meiotic division: evidence for sexual dimorphism J. Cell Sci. 114: 2417–2426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holding, C., D. Bentley, R. Roberts, M. Bobrow and C. Mathew, 1993. Development and validation of laboratory procedures for preimplantation diagnosis of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J. Med. Genet. 30: 903–909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K., S. Thomas, I. B. Howard, T. A. Bell, H. Doherty et al., 2005. Meiotic drive at the Om locus in wild-derived inbred mouse strains. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 84: 487–492. [Google Scholar]

- LeMaire-Adkins, R., and P. A. Hunt, 2000. Nonrandom segregation of the mouse univalent X chromosome: evidence of spindle-mediated meiotic drive. Genetics 156: 775–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann, J. R., 1986. DDK egg-foreign sperm incompatibility in mice is not beween the pronuclei. J. Reprod. Fertil. 76: 779–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo-Manuel de Villena, F., C. Slamka, M. Fonseca, A. K. Naumova, J. Paquette et al., 1996. Transmission-ratio distortion through F1 females at chromosome 11 loci linked to Om in the mouse DDK syndrome. Genetics 142: 1299–1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo-Manuel de Villena, F., A. K. Naumova, A. E. Verner, W. H. Jin and C. Sapienza, 1997. Confirmation of maternal transmission ratio distortion at Om and direct evidence that the maternal and paternal “DDK syndrome” genes are linked. Mamm. Genome 8: 642–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo-Manuel de Villena, F., E. de la Casa-Esperon, A. Verner, K. Morgan and C. Sapienza, 1999. The maternal DDK syndrome phenotype is determined by modifier genes that are not linked to Om. Mamm. Genome 10: 492–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo-Manuel de Villena, F., E. de la Casa-Esperon, T. L. Briscoe and C. Sapienza, 2000. a A genetic test to determine the origin of maternal transmission distortion: meiotic drive at Om. Genetics 154: 333–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo-Manuel de Villena, F., E. de la Casa-Esperon, T. L. Briscoe, J. M. Malette and C. Sapienza, 2000. b Male offspring-specific, haplotype-dependent, nonrandom cosegregation of alleles at loci on two chromosomes. Genetics 154: 351–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo-Manuel de Villena, F., E. de la Casa-Esperon, J. W. Williams, J. M. Malette, M. Rosa et al., 2000. c Heritability of the maternal meiotic drive system linked to Om and high-resolution mapping of the responder locus in mouse. Genetics 155: 283–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo-Manuel de Villena, F., and C. Sapienza, 2001. a Female meiosis drives karyotypic evolution in mammals. Genetics 159: 1179–1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo-Manuel de Villena, F., and C. Sapienza, 2001. b Nonrandom segregation during meiosis: the unfairness of females. Mamm. Genome 12: 331–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renard, J. P., and C. Babinet, 1986. Identification of a paternal developmental effect on the cytoplasm of one-cell stage mouse embryos. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 83: 6883–6886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapienza, C., J. Paquette, P. Pannunzio, S. Albrechtson and K. Morgan, 1992. The polar-lethal Ovum mutant gene maps to the distal portion of mouse chromosome 11. Genetics 132: 241–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakasugi, N., 1973. Studies on fertility of DDK mice: reciprocal crosses between DDK and C57BL/6J strains and experimental transplantation of the ovary. J. Reprod. Fertil. 33: 283–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakasugi, N., 1974. A genetically determined incompatibility system between spermatozoa and eggs leading to embryonic death in mice. J. Reprod. Fertil. 41: 85–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]