Abstract

This review provides an overview and definition of the concept of neurobehavior in human development. Two neurobehavioral assessments used by the authors in current fetal and infant research are discussed: the NICU Network Neurobehavioral Assessment Scale and the Fetal Neurobehavior Coding System. This review will present how the two assessments attempt to measure similar processes from pre to post-natal life by examining three main components of neurobehavior: neurological, behavioral and stress/reactivity measures. Assessment descriptions, strengths and weaknesses, as well as cautions and limitations are provided.

Keywords: neurobehavior, fetal, infant, assessment, development

Prior to the 1960s, newborn infants were considered completely immature organisms without prior experience or learning. Early research focused on the newborn’s ability to respond to external stimuli. In the 1930s, Irwin regarded the newborn as a “non-cortical organism” [Irwin and Weiss, 1930]. Pratt challenged this view; stating that the infant is not merely a “miniature man” nor is the infant simply a “reflexive organism” [Pratt, 1935]. It took another decade for researchers to observe the newborn further for patterns of movement. Seminal work by Gilmer, McGraw, Wolff, and others [Gilmer, 1933; Pratt, 1935; McGraw, 1939; Wolff, 1959; Brazelton, 1961; Cobb, Grimm, Dawson, 1967; Korner, 1969] revealed that neonates have a repertoire of behaviors that are spontaneous yet can be elicited or diminished resulting in the development of assessments designed to assess more complex forms of behavior [Rosenblith, 1961; Brazelton, 1973]. These assessments, such as the Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scale (NBAS), [Als, et al., 1977] have been used extensively to explore individual differences in infant behavior and how they are related to genetics and specific experiences of the infant prior to and during birth.

The term “neurobehavior” is used broadly to reflect the idea that all human experiences have both psychosocial and biological contexts. Biological and behavioral systems dynamically influence each other and are dependent upon neural feedback for optimal synergistic functioning. Neurobehavior reflects the interface of behavior and physiology. A neurobehavioral assessment must be sensitive to the broad range of behaviors that high-risk infants present while also capturing the normal range of behaviors. Thus, the NICU Network Neurobehavioral Scale (NNNS) was designed to measure processes of biobehavioral organization that may be influenced by multiple risk factors.

The advent of ultrasound technology in the 1970s enabled live, unobtrusive observations of fetal behaviors in humans, vastly increasing our knowledge of the human embryo and fetus. This “window” into the critical period of prenatal development provides for the continuity of assessment from pre to post natal life by allowing the main principles of neurobehavioral assessments such as the NNNS to be applied to the assessment of fetal neurobehavior.

Fetal neurobehavior comprises four domains: fetal heart rate, motor activity, behavioral state, and responsiveness to extrauterine stimuli [DiPietro, 2001]. Assessment of these domains across gestational age provides critical information about central nervous system (CNS) development [Nijhuis, 1986; Prechtl and Einspieler, 1997; DiPietro et al., 2002]. The FEtal Neurobehavior Coding System (FENS) was developed to assess these four domains of fetal neurobehavior in healthy as well as at-risk samples. In this article, we will first review the NNNS assessment, followed by a description of the FENS, and then conclude with data showing that the FENS assessment may be predictive of NNNS scores.

THE NNNS

The NNNS is an assessment of infant neurobehavior that was originally developed for the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) NICU Research Network as part of a multisite “Maternal Lifestyle” study (MLS) of the effects of prenatal drug exposure on child outcome [Lester and Tronick, 2004]. The NNNS was designed to provide a comprehensive assessment of both neurological integrity and behavioral function of infants exposed to high-risk conditions such as drugs and/or prematurity. The NNNS assessment includes 3 parts: 1) classic neurological items that assess active and passive tone, primitive reflexes, and CNS integrity; 2) behavioral items including state, sensory and interactive responses; and 3) stress/abstinence items that document the range of withdrawal and stress behavior likely to be observed in substance-exposed or high-risk infants. Infants can be assessed in the preterm period once they are medically stable.

Description of Test Procedures

NNNS items are administered within packages that are defined by a change in focus or position [Lester, Tronick, and Brazelton, 2004a]. The NNNS typically begins with the infant asleep and covered. Initial behavioral state is scored using the traditional criteria described by Prechtl [Prechtl and O’Brien, 1982] for quiet sleep, active sleep, nonalert-waking, alert waking, active waking and fuss, and crying. If the initial assessment of the infants’ behavioral state determines that the infant is in a sleep state, the infant is then presented with repeated trials of light and then sound until the infant no longer responds to the stimulus (habituation).

The infant is then undressed and placed supine on a flat surface to observe the infant’s posture, skin color, skin texture, and movement. Reflexes are then examined within packages: seven Lower Extremity Reflexes, nine Upper Extremity Reflexes, four Upright, and three Prone responses. These reflexes are all assessed with the infant in an awake, noncrying state. The assessment includes measures of classic reflexes, muscle tone, and joint angles. The infant also is assessed for “cuddliness” by picking up the awake, calm infant and cuddling him or her with the arm cradled without talking. This is repeated with the infant on the examiner’s shoulder. The infant’s ability to attend, respond to, and visually track animate and inanimate stimuli is assessed with the infant on the examiner’s lap in a calm, awake state. At the conclusion of the behavioral and neurological items, the infant is returned to the crib for a final assessment of the infant’s state.

A great deal of attention is paid to the infant’s behavioral state throughout the assessment. The examiner will assist the infant in obtaining a quiet, alert state by using graduated soothing techniques when crying or gently stimulating the infant with ventral rocking or talking when the infant is drowsy. The types and number of techniques used to keep the infant in the appropriate state are structured and limited and are scored as part of the total assessment. Administering the NNNS takes approximately 30 min and scoring the exam requires an additional 15 min.

Description of Scoring System

The NNNS is scored by the examiner once the administration is complete. The infant’s responses/performance on each of the administered items is scored first, followed by 20 items designed to summarize the infant’s behavior throughout the course of the exam. The 51-item Stress/Abstinence Scale is scored last to record the presence or absence of observed signs or behaviors that may indicate developmental problems or signs of withdrawal. The items are divided into the following systems: Physiological, Autonomic, CNS, Skin, Visual, Gastrointestinal, and State.

Raw scores may be converted to a set of summary scores, developed a priori, and tested in the Maternal Lifestyle Study sample of 1,388 infants. The summary scores include Habituation, Orientation, Amount of Handling, State, Self-Regulation, Hypotonia, Hypertonia, Quality of Movement, Number of Stress Abstinence Signs (which can be also computed by organ system), and Number of Nonoptimal Reflexes [Lester et al., 2004b].

Training Required

Appropriate use of the NNNS requires certification through the NNNS Assessment Training Program. The established certification procedures require examiners to meet specified criteria in areas of administration and scoring. Training programs are available in the United States, Europe, South America, and Southeast Asia. There is also a Spanish version of the manual.

Significance of Test Results

Information from the NNNS can be used for research and clinical practice. Most research to date uses the NNNS as an outcome measure to study the effects of a previous perinatal exposure, insult, or event. However, an increasing number of studies are using the exam to evaluate the effectiveness of specific treatments, such as medications used to help reduce withdrawal symptoms in heroin-and methadone-exposed infants. The NNNS examination can be repeated without affecting the reliability or validity of the scores. Multiple exams may be useful for documenting change in infant behavior that may indicate recovery processes and/or responses to treatment. Clinical applications include developing a profile of the infant to write a management plan for the infant while in the hospital, evaluating the infant close to discharge as part of the discharge plan, and aiding in the transition to home by involving the caregivers in the exam. The exam also can be used to determine which infants qualify for early-intervention services.

Cautions and Limitations

The NNNS provides an assessment of a wide range of neurobehavioral function in at-risk infants but is not appropriate for highly detailed assessments of specific functions. Although some classical reflexes, measures of tone and posture, preterm behavior, and stress abstinence are measured by the NNNS, it does not provide the level of detail needed if the focus were only on one of these domains. For example, the Assessment of Preterm Infants’ Behavior (APIB) [Als et al., 1982] provides a more in-depth assessment of preterm behavior than the NNNS. Similarly, the NNNS Stress/Abstinence scale includes items to measure drug withdrawal from Finnegan’s measure of neonatal abstinence [Finnegan, 1986], but it does not include all of the items or the specific cut-offs used by the Finnegan to determine drug treatment for addicted infants. Although the NNNS can be used to assess healthy term infants, the NBAS may be the more appropriate choice for researchers and clinicians working with low-risk infants because many of the behaviors measured by the NNNS will not occur.

Data sets from a large sample of 1-month-old cocaine and/or opiate-exposed infants, high-risk comparison infants, and healthy term newborn infants have been published [Lester et al., 2004b]. Although these data are not truly normative, these quasinormative data sets may serve as useful comparisons for researchers and clinicians. Efforts to develop norm-referenced databases for the NNNS at selected gestational ages are continuing and once completed, will aid in our understanding of these infants.

Strengths/Benefits

The NNNS includes measures of classical reflexes, tone, posture, social and self-regulatory competencies, and signs of stress in infancy. The inclusion of each of these domains provides a comprehensive and integrated picture of the infant that cannot be obtained from assessments focused on specific functional domains. An assessment of reflexes alone will not provide information about the infant’s higher order functioning, regulatory capacities and coping strategies. Likewise, a focused assessment of social interactive capacities will not assess the infant’s basic neurological function that may determine behavior.

In addition to being comprehensive, the NNNS was designed around the principle of state-dependent administration, which requires that items be administered in specific states and that when they are elicited they are only administered a set number of times. These rules insure the comparability of how state affects performance and emphasizes the state dependent features of infant responsiveness.

The NNNS is designed to maintain structure while allowing for some flexibility. The NNNS has a relatively invariant sequence of item administration in that the specified sequence is one strongly preferred by experienced examiners because most infants can achieve it. Thus individual differences in examiner style are minimized. Modifications are allowed, but the order of administration and deviations from the standard sequence are recorded. This semistructured design of the NNNS effectively balances structure with flexibility which minimizes the time needed to administer the examination by eliminating time outs and soothing procedures aimed at bringing out optimal performance.

THE FENS

Goal/Objective of the Test

Our goal was to develop a method of observing and measuring fetal behaviors in utero during the second half of pregnancy that would assess fetal CNS maturation, including neurological development and behavioral reactivity, in typically developing and at-risk fetuses. We needed a safe, reliable procedure that could be completed in a minimum amount of time, be comfortable for the women, and be amenable to the addition of fetal heart rate and activity monitoring. We developed our behavioral coding scheme based on the work of others in the field [de Vries, Visser, and Prechtl, 1982; Nijhuis et al., 1982; de Vries, Visser, and Prechtl, 1985; Pillai and James, 1991; Pillai, James, and Parker, 1992], our own experiences observing fetal and infant behavior, and our experience developing and using the NNNS.

Although assessment of fetal neurobehavior is limited to visual observation and physiological measures, the FENS includes the same three components of assessment as the NNNS: neurological, behavioral, and stress/reactivity measures. We included behaviors that would enable reliable measurement within these three domains.

Description of the Test Procedures

We use real-time ultrasound (Toshiba diagnostic ultrasound machine, model SSA-340A, with a 3.750-MHz transducer; Toshiba American Medical, Duluth, GA) to examine fetal behaviors in conjunction with a fetal actocardiograph (Toitu MT325) to monitor fetal heart rate (FHR) and activity [DiPietro, Costigan, and Pressman, 1999]. While the participant reclines in a semirecumbent position; the fetus is monitored for a baseline period of time (40–60 min); followed by a single; 3-s vibroacoustic stimulus applied to the maternal abdomen and an additional 10–30 min observation after the stimulus. Alternative stimuli, such as light and airborne sounds, may be used in the FENS. The maximum observation time is limited to 60 min of ultrasound scanning. Fetal behavior is observed using one ultrasound transducer that is focused on a longitudinal view of the fetus; including visualization of the face, trunk, and upper limbs (Fig. 1). The actocardiograph machine (Toitu m325; H&A Medical, Lone Tree, CO) collects simultaneous information about FHR, fetal heart patterns, and fetal movement (amplitude, duration, frequency) [Maeda et al., 1988; Maeda, Tatsumura, and Nakajima, 1991; DiPietro, Costigan, and Pressman, 1999]. The data from the actocardiogram are synchronized with the ultrasound recording for scoring of fetal behaviors, fetal heart rate, activity, and fetal behavioral state.

Fig. 1.

Preferred view of the fetus for coding: visualization of the fetal eye, mouth, chest, and one or more limbs.

Description of the Scoring System

The ultrasound observation is recorded on videotape for coding of specific fetal behaviors. The videotape is then dubbed with a SMPTE time code, which has a resolution up to a 30th of a second, onto the right audio channel of the ultrasound recording. The SMPTE dub is coded at the computer keyboard for fetal behaviors using a computer-based behavioral coding system: The Action, Analysis, Coding, and Training (AACT) Program (Intelligent Hearing Systems: Miami, FL).

The FENS fetal behavior coding system incorporates definitions for fetal behaviors following DeVries et al. [de Vries, Visser, and Precht, 1982] classification; Pillai et al., rest-activity cycles [Pillai, James, and Parker, 1992]; as well as behaviors that may be indicative of stress and/or coping derived from the NNNS [Lester and Tronick, 2004] (see Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Fetal Behavior Coding Definitions: Face View

| Behavior | Definition |

|---|---|

| Fetal Eye Movement | Clear movement of the pupil or eyelid when a view of the eyes is obtained. |

| Suck/Rhythmic mouthing★ | Rhythmical bursts of regular jaw opening and closing at a rate of approximately one per second (or more). |

| Regular and Irregular sucking is coded. | |

| Drinking and Mouthing Movements | Mouth opening and closing that is isolated or limited to less than 3 at one time, often with tongue protrusion. You may see swallowing of amniotic fluid. |

| Yawn★ | This movement is similar to the yawn observed after birth: prolonged wide opening of the jaws followed by quick closure often with flexion of the head and sometimes elevation of the arms. |

| Hand to Face★ | The hand slowly touches the face or mouth, the fingers frequently flex and extend. |

| Isolated Head Movement (IH), head rotation, extension | Movement of the head that is not accompanied by limb or trunk movement, either small jerky movements in the vertical plane, rotation from side to side, or extension. |

Behaviors that also are coded as “stress signs” consistent with NNNS scoring.

Adapted from de Vries, Visser, and Prechtl [1982] and de Vries et al. [1985].

Table 2.

Fetal behavior coding definitions: Chest/Upper Body View

| Behavior | Definition |

|---|---|

| Breathing Movements | Displacement of the diaphragm lasting less than 1s that is either small or large. |

| Isolated Limb Movement (IL) | Movement of any limb or combination of limb movements that does not include trunk or head movement. Scored as smooth or jerky in quality. |

| General Body Movement (GB) | An indiscriminate pattern of movement involving at least one limb, the trunk and the head. Scored as smooth or jerky in quality. |

| Startle★ | A quick, generalized movement, always initiated in the limbs and sometimes spreading to neck and trunk. |

| Back Arch★ | Extension of the trunk and maintenance in this position for greater than 1 second. |

| Stretch | Always carried out at a slow speed and consists of: forceful extension of the back, retroflexion of the head, and external rotation and elevation of the arms. |

| Hiccup★ | Consists of a jerky, repetitive contraction of the diaphragm. |

| Hyperflexion | Flexion of the trunk and maintenance of this position for greater than 1 second. |

Behaviors that also are coded as “stress signs” consistent with NNNS scoring.

Adapted from de Vries, Visser, and Prechtl [1982] and de Vries et al. [1985].

After an initial inspection of the videotape for quality of the image, the tape is viewed and scored in two separate passes. The first pass is to code movements and behaviors involving the face and head (Table 1): head movements, eye movements, sucking (Fig. 2), drinking, and yawning. The second pass is to code specific movements and movement patterns involving the chest and body (Table 2). The quality of these movements also is coded as either jerky or smooth. Specific behavior patterns, such as fetal breathing movement, startle, backarch, stretch, and hiccup, are coded whenever they are present. Inter-rater reliability has been demonstrated for videotaped-coding, with percent agreement scores of 73% to 100% and Intraclass correlations of 0.73 to 1.0.

Fig. 2.

A 26-week gestational-age fetus sucking its thumb.

Fetal actocardiogram strips are scanned into the computer and digitized using the NIH-Scion IMAGE program (Scion Corp). The data are then processed for FHR and activity measures according to DiPietro’s established guidelines [DiPietro, Costigan, and Pressman, 1999; DiPietro, 2001]. Actocardiogram data are then synchronized with behavioral observation data. Scoring of fetal behavioral state for fetuses older than 32 weeks of gestation is completed by visual inspection of the actocardiogram strip coupled with a print out of episodes of fetal eye movement and fetal breathing.

Typical Duration of Test Procedure

The fetal ultrasound procedures take 60–90 min to complete. Scoring of the ultrasound videotape requires approximately 2–4 h per tape. Processing the actocardiogram requires approximately 60 min per strip without automated digitizing equipment and an additional 20–30 min for state scoring.

Training Required

The FENS uses medical technology for the recording of non-diagnostic information. To follow the guidelines of the Food and Drug Administration, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine, the use of ultrasound technology requires that an individual performing ultrasound scans for any reason be trained in Limited, Basic, or Targeted Obstetrical Ultrasound. Therefore, personnel certified in Limited Obstetrical Ultrasound are required to run the fetal ultrasound recordings. Training and certification in fetal monitoring is also required for running the fetal heart rate recordings. The FENS nurse or technician is then trained to maintain an optimal view of the fetus for behavior recordings. Once trained on ultrasound and fetal monitoring, the FENS procedures require an additional training period of 10–20 h of practical application.

Coding of fetal behavior involves the ability to observe behaviors and run the AACT computer program, as well as the additional skill of being able to visualize the fetus on the recording. Coders are trained first by having them observe behaviors and states in neonates, followed by observations of fetal ultrasounds as they are recorded. Trainees then view fetal videotapes until they are comfortable identifying specific movements. Trainees code at least 5 recordings before testing reliability with other trained coders. Once reliability is established at greater than 80% agreement, the coder is able to score tapes independently. Coding reliability is checked periodically.

Significance of Test Results

Fetal neurobehavior measures were found to differentiate at-risk infants prenatally. Growth-retarded fetuses compared with normally developing fetuses showed a delayed appearance of fetal behavioral states, longer state transitions, and disorganized behavior patterns[van Vliet et al., 1985; Arduini, Rizzo, and Romanini, 1995]. Growth-retarded fetuses also showed a difference in the quality and quantity of fetal movement. Fetuses of diabetic mothers had a delay in the appearance of fetal behavioral states and increased periods of non-concordance of fetal variables within states [Mulder et al., 1987].

When these methods were used with substance using women during pregnancy, cocaine-exposed fetuses spent more time in a waking active state, with fewer state transitions [Hepper, 1995; Gingras and O’Donnell, 1998]. Fetuses of smoking mothers were more likely to have nonreactive tests or decreased reactivity, which can be indicative of fetal distress [Phelan, 1980; Graca et al., 1991; Oncken et al., 2002].

Maternal stress and anxiety were reported to have some effect on fetal neurobehavior. Fetuses of mothers with high trait anxiety scores spent significantly more time in quiet sleep and had fewer gross body movements when in active sleep [Groome et al., 1995]. In an acute stress model; pregnant women with high anxiety scores exposed to a cognitive task had lower elevations in blood pressure than nonanxious women and their fetuses had greater FHR increases after the task [Monk et al., 2000, 2003].

These studies demonstrate the importance of looking at fetal variables in a variety of contexts. The FENS provides a comprehensive assessment of the fetus by looking at fetal behavior, behavioral state, stress reactivity, and physiology.

Cautions and Limitations

There are obvious limitations to studying human fetal behavior, such as access to observe and measure fetal variables without imposing a source of stress or risk to the fetus or mother. The use of ultrasound technology for human fetal observation has been found to be safe by the World Federation for Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology (WFUMB). Guidelines for use during pregnancy were established by the WFUMB over and above those recommended by the Food and Drug Administration[Barnett et al., 2000]. The guiding principles suggest using the lowest power, lowest intensity Doppler scanning, for the shortest amount of time possible. We limit the amount of scanning time to one hour.

Another consideration is that the use of two ultrasound transducers allows for more detailed and extensive views of the fetus than a single transducer. However, using two transducers increases the likelihood of interference or noisy signal on the actocardiogram. It also increases the amount of sound waves delivered in to the uterus, thereby increasing sound wave exposure to the fetus. Therefore, the use of one ultrasound transducer in conjunction with a fetal actocardiogram is preferable. The use of one transducer was previously validated for measurement of fetal behavioral state. [Arabin et al., 1988]

In general, the use of the FENS is limited to research purposes at present as it is too long for general medical assessments of fetal neurobehavioral development. In addition, adequate control of factors known to influence fetal behavior such as maternal caffeine and other substance use, time of last meal, time of day and comfort of the recording condition may be difficult and would limit the feasibility of general medical use [Pillai and James, 1990; Pillai, James, and Parker, 1992; Devoe et al., 1993; Lecanuet et al., 1995; Mulder et al., 1998]. These factors and potential modifications will be addressed in future research.

Strength/Benefits

Studying the fetus enables us to examine the factors that may influence prenatal development at the time of their occurrence. The behavior measured prenatally is also less susceptible to the influence of other variables that appear to be more salient in the newborn period, such as the stress of the labor and delivery process, sex differences, and potential effects of drugs given during labor and delivery or immediately after birth.

The FENS examines behavioral and physiological development that may be affected by substance exposure and maternal conditions (such as medical and psychiatric illnesses), which may be precursors to later emotional development.

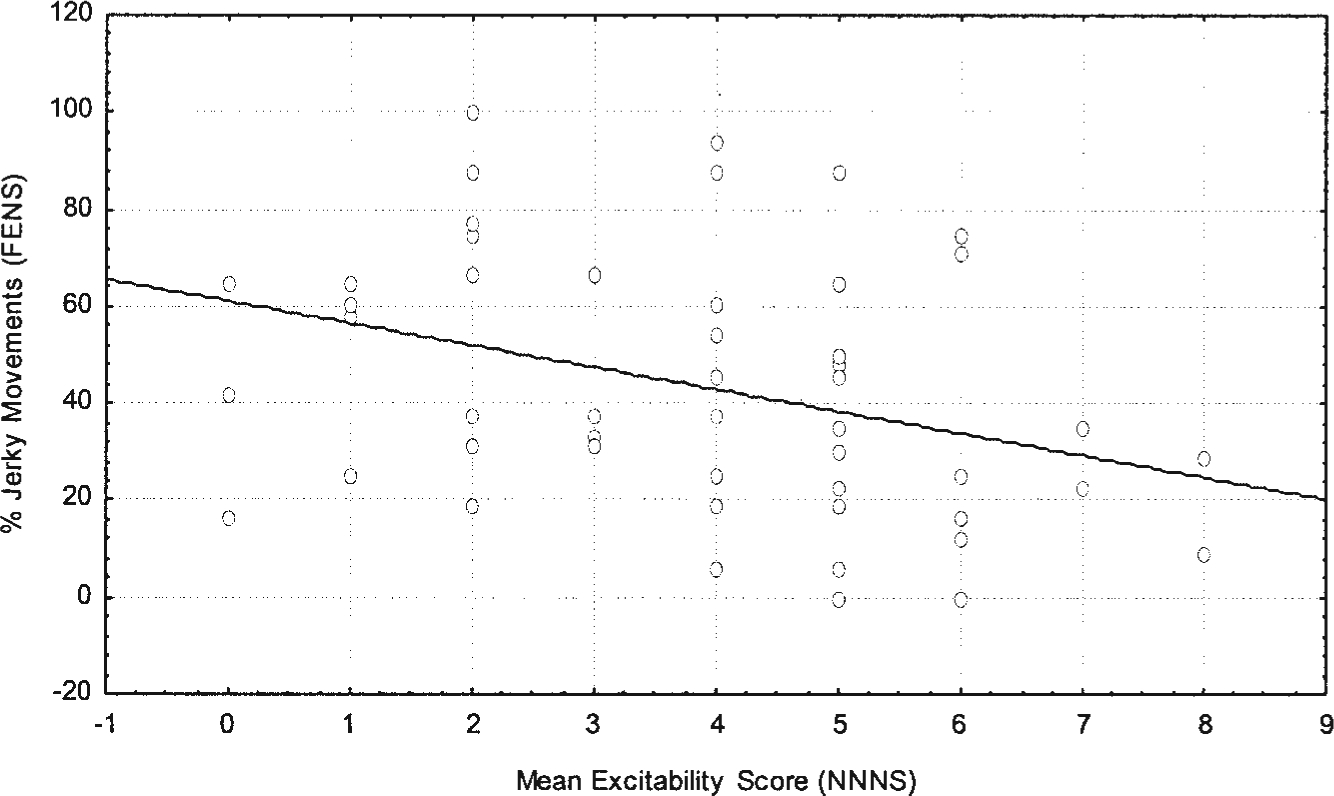

We are currently testing the predictive ability of the FENS to the NNNS in several large-scale studies in at risk and control samples. We have preliminary evidence from a smaller pilot study that the FENS and NNNS variables are correlated. FENS variables measured in a community sample between 25 and 32 weeks of gestation were correlated with newborn NNNS variables of 60 healthy, full-term infants. Infants were assessed with the NNNS between 24 and 48 h after delivery. Fetal quality of movement was related to NNNS outcome variables (Figs. 3 and 4). Specifically, fetal smooth movements were positively correlated with NNNS self-regulation scores and negatively correlated with NNNS excitability. The data are limited by sample size and short fetal recording period (<20 min) but support further testing of continuity between fetal neurobehavior measured with the FENS and infant neurobehavior on the NNNS at least in the newborn period.

Fig. 3.

Scatterplot of fetal smooth movements on the FENS and newborn self-regulation scores on the NNNS; r = 0.34, P < 0.01, n = 59.

Fig. 4.

Scatterplot of fetal smooth movements on the FENS and newborn excitability scores on the NNNS, r = 0.63, P < .003, n = 50.

CONCLUSIONS

Longitudinal assessments of fetuses into infancy will enable us to examine early development in a variety of contexts and at critical developmental time points. The FENS and NNNS assessments allow for a comprehensive and “seemless” assessment of fetal to infant development. We currently are using both assessments in a longitudinal study of fetal and infant neurobehavioral development in healthy and at-risk samples. One of our studies is examining the potential effects of fetal exposure to maternal depression or antidepressant medications compared with those who were never exposed to maternal psychiatric illness or medications.

Acknowledgments

Grant sponsor (for NNNS): NIH; Grant numbers: U10 HD 27904, U10 HD 21397,U10 HD 21385; U10 HD 27856, NICHD contract N01-HD-2-3159, and intraagency agreements with the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), Administration on Children, Youth and Families (ACYF), and the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (CSAT); Grant sponsor (for FENS): NIMH; Grant number: K-23 Mentored Patient Oriented Research Career Award 1 K23 MH65479-01 (ALS).

REFERENCES

- Als H, Lester B, Tronick E et al. 1982. Towards a research instrument for the assessment of preterm infants’ behavior (A.P.I.B.). In: Fitzgerald H, Lester B, Yogman M, editors. Theory and research in behavioral pediatrics. New York: Plenum Press. p 85–132. [Google Scholar]

- Als H, Tronick E, Lester B, et al. 1977. The Brazelton Neonatal Behavioral Assessment and Scale (BNBAS). J Abn Child Psychol 5(3): 215–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arabin B, Riedewald S, Zacharias C, et al. 1988. Quantitative analysis of fetal behavioural patterns with real-time sonography and the actocardiograph. Gynecol Obstet Invest 26:211–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arduini D, Rizzo G, Romanini C. 1995. Fetal behavioral states and behavioral transitions in normal and compromised fetuses. In: Fifer WP, Lecanuet JP, editors. Fetal development: a psychobiological perspective. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. p 83–99. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett SB, Ter Haar GR, Ziskin MC, et al. 2000. International recommendations and guidelines for the safe use of diagnostic ultrasound in medicine. Ultrasound Med Biol 26:355–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazelton TB. 1961. Psychophysiologic reactions in the neonate. I. The value of observations of the neonate. Disabil Rehabil 58:508–512. [Google Scholar]

- Brazelton TB. 1973. Assessment of the Infant at Risk. Clin Obstet Gynecol 16(1):361–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb K, Grimm ER, Dawson B. 1967. Reliability of global observations of newborn infants. J Gen Psych. 110(2):253–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries JIP, Visser GHA, Prechtl HFR. 1982. The emergence of fetal behavior, I. Qualitative aspects. Early Hum Dev 7:301–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries JIP, Visser GHA, Prechtl HFR. 1985. The emergence of fetal behaviour. II. Quantitative aspects. Early Hum Dev 12:99–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devoe LD, Murray C, Youssif A, et al. 1993. Maternal caffeine consumption and fetal behavior in normal third- trimester pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 168:1105–1111; discussion 1111–1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiPietro J 2001. Fetal neurobehavioral assessment. In: Zeskind PS, Singer JE, editors. Biobehavioral assessment. Amstersdam: Elsevier; p 43–80. [Google Scholar]

- DiPietro JA, Bornstein MH, Costigan KA, et al. 2002. What does fetal movement predict about behavior during the first two years of life? Dev Psychobiol 40:358–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiPietro JA, Costigan KA, Pressman EK. 1999. Fetal movement detection: comparison of the Toitu actograph with ultrasound from 20 weeks gestation. J Matern Fetal Med 8:237–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnegan L 1986. Neonatal abstinence syndrome: assessment and pharmacotherapy. In: Rubatelli F, Granati B, editors. Neonatal therapy and update. New York: Experta Medica. [Google Scholar]

- Gilmer BVH. 1933. An analysis of the spontaneous responses of the newborn infant. J Gen Psych 42:392–405. [Google Scholar]

- Gingras JL, O’Donnell KJ. 1998. State control in the substance-exposed fetus. I. The fetal neurobehavioral profile: an assessment of fetal state, arousal, and regulation competency. Ann N Y Acad Sci 846:262–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graca LM, Cardoso CG, Clode N, et al. 1991. Acute effects of maternal cigarette smoking on fetal heart rate and fetal body movements felt by the mother. J Perinat Med 19:385–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groome LJ, Swiber MJ, Bentz LS, et al. 1995. Maternal anxiety during pregnancy: effect on fetal behavior at 38 to 40 weeks of gestation. J Dev Behav Pediatr 16:391–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepper PG. 1995. Human fetal behaviour and maternal cocaine use: a longitudinal study. Neurotox 16:139–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin OC, Weiss AP. 1930. A note on mass activity in newborn infants. J Gen Psych 38:20–30. [Google Scholar]

- Korner AF. 1969. Neonatal startles, smiles, erections, and reflex sucks as related to state, sex, and individuality. Child Dev 40:1039–1053. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecanuet JP, Fifer W, Krasenegor NA, et al. , editors. 1995. Fetal development: a psychobiological perspective. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. p 512. [Google Scholar]

- Lester BM, Tronick EZ. 2004. History and description of the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Network Neurobehavioral Scale. Pediatrics 113:634–640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester BM, Tronick EZ, Brazelton TB. 2004a. The Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Network Neurobehavioral Scale procedures. Pediatrics 113: 641–667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester BM, Tronick EZ, LaGasse L, et al. 2004b. Summary statistics of neonatal intensive care unit network neurobehavioral scale scores from the maternal lifestyle study: a quasinormative sample. Pediatrics 113:668–675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda K, Tatsumura M, Nakajima K. 1991. Objective and quantitative evaluation of fetal movement with ultrasonic Doppler actocardiogram. Biol Neonate 60(Suppl 1):41–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda K, Tatsumura M, Nakajima K, et al. 1988. The ultrasonic Doppler fetal actocardiogram and its computer processing. J Perinat Med 16:327–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGraw MB. 1939. Swimming behavior of the human infant. J Pediatr. 15:485–490. [Google Scholar]

- Monk C, Fifer WP, Myers MM, et al. 2000. Maternal stress responses and anxiety during pregnancy: effects on fetal heart rate. Dev Psychobiol 36:67–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monk C, Myers MM, Sloan RP et al. 2003. Effects of women’s stress-elicited physiological activity and chronic anxiety on fetal heart rate. J Dev Behav Pediatr 24(1):32–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulder EJ, Morssink LP, van der Schee T, et al. 1998. Acute maternal alcohol consumption disrupts behavioral state organization in the near-term fetus. Pediatr Res 44:774–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulder EJ, Visser GH, Bekedam DJ, et al. 1987. Emergence of behavioural states in fetuses of type-1-diabetic women. Early Hum Dev 15: 231–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijhuis JG. 1986. Behavioural states: concomitants, clinical implications and the assessment of the condition of the nervous system. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 21:301–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijhuis JG, Prechtl HFR, Martin CB Jr., et al. 1982. Are there behavioural states in the human fetus? Early Human Dev 6:177–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oncken C, Kranzler H, O’Malley P, et al. 2002. The effect of cigarette smoking on fetal heart rate characteristics. Obstet Gynecol 99:751–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan JP. 1980. Diminished fetal reactivity with smoking. Am J Obstet Gynecol 136:230–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillai M, James D. 1990. Development of human fetal behavior: a review. Fetal Diagn Ther 5:15–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillai M, James D. 1991. Human fetal mouthing movements: a potential biophysical variable for distinguishing state 1F from abnormal fetal behavior; report of 4 cases. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 38:151–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillai M, James DK, Parker M. 1992. The development of ultradian rhythms in the human fetus. Am J Obstet Gynecol 167:172–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt KC. 1935. The organization of behavior in the newborn infant. Psych Bull 32:692–693. [Google Scholar]

- Prechtl HF, Einspieler C. 1997. Is neurological assessment of the fetus possible?. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 75:81–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prechtl HFR, O’Brien MJ. 1982. Behavioral states of the full-term newborn. The emergence of a concept. In: Stratton P, editor. Psychobiology of the human newborn. New York: John Wiley & Sons. p 53–73. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblith JF. 1961. The modified Graham behavior test for neonates: test-retest reliability, normative data, and hypotheses for future work. Biologia Neonatorum 3:174–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Vliet MA, Martin CB Jr, Nijhuis JG, et al. 1985. Behavioural states in growth-retarded human fetuses. Early Hum Dev 12:183–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff PH. 1959. Observations on newborn infants. Psychosom Med 21:110–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]