Abstract

Asthma is a chronic disorder that can place considerable restrictions on the physical, emotional, and social aspects of the lives of patients. Inhaled glucocorticoids (GCs) are the most effective controller therapy. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effect of inhaled GCs on quality of life in patients with moderate to severe asthma. Patients completed the asthma quality of life questionnaire (AQLQ) and pulmonary function test at baseline and after 4 wks treatment of GCs. We enrolled 60 patients who had reversibility in FEV1 after 200 µg of albuterol of 15% or more and/or positive methacholine provocation test, and initial FEV1% predicted less than 80%. All patients received inhaled GCs (fluticasone propionate 1,000 µg/day) for 4 wks. The score of AQLQ was significantly improved following inhaled GCs (overall 51.9±14.3 vs. 67.5±12.1, p<0.05). The change from day 1 to day 28 in FEV1 following inhaled GCs was diversely ranged from -21.0% to 126.8%. The improvement of score of AQLQ was not different between at baseline and after treatment of GCs according to asthma severity and GCs responsiveness. Quality of life was improved after inhaled GCs regardless of asthma severity and GCs responsiveness in patients with moderate to severe asthma.

Keywords: Glucocorticoids, Quality of Life, Asthma

INTRODUCTION

Asthma is a chronic disorder that can place considerable restrictions on the physical, emotional, and social aspects of the lives of patients and may have an impact on their careers. Many people with asthma do not completely appreciate the impact of the disease on their social life and claim the lead "normal" lives either because normality may be based on adjustments and restrictions that they have already incorporated into their lifestyle or because they deny their restriction, wanting to "live like others" (1). Recently studies of patient outcomes in asthma have focused on clinical and physiologic measures (2). Although such clinical measures do not provide a complete, accurate view of the impact of a disease on an individual's physical, social, or emotional well being, health related quality of life measures are increasingly being integrated into clinical research in asthma (2-4).

Inhaled glucocorticoids (GCs) have revolutionized the treatment of asthma and have now become the mainstay of therapy for patients with chronic asthma (5, 6). Asthma management guidelines (1) have mentioned that the early intervention and effective dosage (start high-go low), and enough period of inhaled GCs would be the best way to control and maintain asthma symptoms. Control of asthma (1) is monitored by asthma symptoms, the use of rescue inhaled β2-agonist, and measurement of diurnal variation of peak expiratory flow (PEF), FEV1, and by non-invasive markers of inflammation such as exhaled nitric oxide and induced sputum and airway hyperresponsiveness. A wide variation of response to inhaled GCs is expected between patients, but there is little data about responsiveness to high dose inhaled GCs relation to change in FEV1 and asthma symptoms such as asthma quality of life questionnaire (AQLQ). Therefore, the aims of this study were to examine the effect of maximally recommended dose of inhaled GCs (1,000 µg of fluticasone propionate, FP) for 4 wks on AQLQ of patients with moderate to severe asthma, and the correlation of AQLQ with asthma severity and GCs responsiveness.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

On the first day of study, a clinical history was obtained using a physician-administered questionnaire. Chest PA radiography, the allergy skin prick test, and spirometry including bronchodilator response after inhalation of 2 puffs of 100 µg aerosolized albuterol were performed. Blood and sputum were sampled for differential cell counts. AQLQ was evaluated at baseline and 4 wks. On second day, airway hyperrespousiveness (AHR) was measured in case of 70% or more in FEV1% predicted. The patients were educated visually by the trained nurse how to use the inhaled GCs until the accuracy score reach 12 of 14 (maximal score) (7). The inhaled GCs was started and maintained for 4 wks. The dose of inhaled GCs used via a multi-dose dry powder inhaler was FP 1,000 µg/day (2 puff b.i.d, Diskhaler; GSK, U.S.A.). During the study period, the patients were asked to record their symptom score and medication usage. The patients used short acting bronchodilator as needed base. The switch to combination or add on therapy was done in exacerbation during study period; deterioration of greater than 12% in AQLQ or FEV1 at any time with developing aggravating symptoms. The primary end points were the change in AQLQ, basal FEV1, FEF25-75%, and FEV1/FVC after treatment of inhaled GCs.

Subjects

The patients with chronic asthma were recruited from the out patient clinics in Soonchunhyang University Hospital. All patients with asthma had currently one or more asthma symptoms and the findings of physical examination compatible with asthma definition by the American Thoracic Society (8). Each patient showed airway reversibility as documented by a positive bronchodilator response of more than 15% increase in FEV1 and/or an airway hyper-reactivity of less than 10 mg/mL methacholine (9). Asthma severity was classified with symptoms, pulmonary function before treatment. The exclusion criteria were as follows: duration of asthma less than one year, acute exacerbated asthma within 4 wks, history of brittle asthma, atopic individuals to pollens, parenchymal lung diseases on chest radiography, diffusing capacity less than 80%, previous inhaled steroid or systemic steroid usage within the past 4 wks, and maintaining theophylline or leukotriene antagonist therapy. The prospective controlled trial involved 60 patients of mean age 45 yr with moderate to severe persistent asthma. The clinical parameters are summarized in Table 1. 42.5% of asthmatics showed positive skin test to the common inhalant allergens. The change from day 1 to day 28 in FEV1 [ΔFEV1=(FEV1 at 4 wks-baseline FEV1)/baseline FEV1] following inhaled GCs was measured. Responder to inhaled GCs was regarded as demonstrating greater response than 12% or more in ΔFEV1. During this period, 5 patients of asthmatics moved to the combination or add on therapy according to the protocol due to decreases of greater than 12% in FEV1 or AQLQ with symptom aggravation. This study was performed with the approval of the Ethics Committee of the University Hospital and informed written consent was obtained from all study subjects.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the patients*

*Plus-minus values are mean±SD. FEV1, forced expiratory volume in one second. FVC, forced vital capacity; FEF, forced expiratory flow. †p<0.01 compared with moderate asthma patients. AQLQ score, asthma quality of life score.

Quality of life measurement

AQLQ was evaluated at baseline and 4 wks by using the quality of life questionnaire for adult Korean asthmatics (10). Each question was answered by the patient on a 5-point scale, with a score of 1 representing the greatest impairment and a score 5 representing no impairment (lower AQLQ scores therefore reflect increased impairment). Items were equally weighted and reported as the mean score for each domain (activity limitations, emotions, symptoms, and exposure to environmental stimuli) along with an overall score.

Lung function tests

Baseline measurements of FVC and FEV1 were selected according to American Thoracic Society criteria (8). Basal and post-bronchodilator FEV1, FVC, and FEF25-75% were measured. The measurement was made between 1 p.m. and 4 p.m. AHR was measured by a methacholine challenge test and expressed as the provocation concentration to cause a fall in FEV1 of 20% (PC20) in non-cumulative units (11).

Sputum examination

Sputum was induced using isotonic saline containing a short-acting bronchodilator as described by Norzila et al. (12). Samples were treated within 2 hr of collection using the method of Pizzichini et al. (13) with a minor modification. Briefly, all visible portions with more solidity were carefully selected and placed in a preweighed Eppendorf tube. Samples were treated by adding four volumes of 0.1% dithiothreitol (Sputolysin, Calbiochem Corp., San Diego, Calif., U.S.A.). One volume of protease inhibitors (0.1 M EDTA and 2 mg/mL phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride) was added to 100 volumes of the homogenized sputum, and the total cell count was determined with a hemocytometer. Homogenized sputum was spun in a cytocentrifuge and 500 cells were read on each sputum slide stained with Diff-quick solution (American Scientific Products, Chicago, Ill., U.S.A.).

Allegy skin prick tests

Allergy skin prick tests were performed using commercially available 55 inhalant allergens including dust mites (Dermatophagoides farinae and Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus, Bencard co, Reinbek, Germany) and histamine (1 mg/mL, Bencard, U.K.). None of the subjects had received antihistamines orally in the three days preceding the study. All tests included positive (1 mg/mL histamine) and negative (diluent) controls. After 15 min, the mean diameter of any wheal formed by the allergen was compared with that formed by histamine. If the former was the same or larger than the latter (A/H ratio ≥1.0), the reaction was deemed positive. Atopy was determined by the presence of an immediate skin reaction to one or more aeroallergens as previously described (14).

Statistical analysis

Data were doubled entered onto SPSS (v 10.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, U.S.A.). Data are expressed as mean±SD. Comparison of continuous variables was made using independent samples t testing. Differences in proportions were analyzed by chi-square testing with Fisher exact test when low expected cell counts were encountered. Pearson's correlations and Spearman's correlations were used to assess relationships between variables. A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

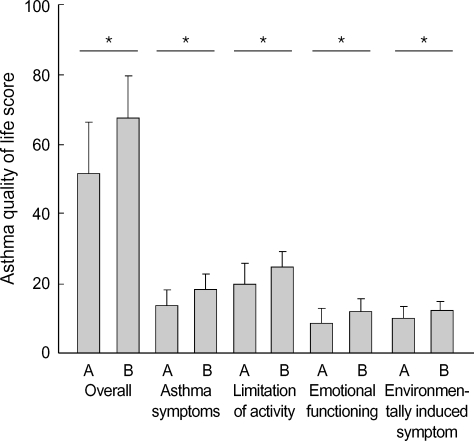

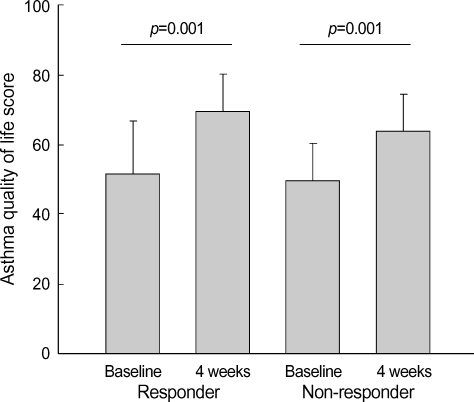

The scores of AQLQ were significantly increased after 4 wks of inhaled GCs (overall; 51.9±14.3 vs. 67.5±12.1, asthma symptoms; 13.5±4.5 vs. 18.4±4.2, limitation of activity; 19.9±5.4 vs. 24.8±4.3, emotional functioning; 8.6±4.0 vs. 12.1±3.2, environmentally induced symptom; 10.0±3.6 vs. 12.1±2.4, respectively p<0.01. Fig. 1). During the study period, 33 patients (55.0%) with asthma showed 12% or more increase in FEV1 after high dose inhaled GCs and 27 patients were non-responder. The change in FEV1 [ΔFEV1=(FEV1 at 4 wks-baseline FEV1)/baseline FEV1] following inhaled GCs was diverse from -21% to 126.8%. The change in FVC [ΔFVC=(FVC at 4 wks-baseline FVC)/baseline FVC] following inhaled GCs was diverse from -74% to 37%. The change in FEF [ΔFEF=(FEF at 4 wks-baseline FEF)/baseline FEF] following inhaled GCs was diverse from -27.0% to 100%. FEV1% predicted, FEF25-75%, FEV1/ FVC were significantly increased at 4 wks of inhaled GCs in moderate to severe asthmatics (Table 2). The responder of greater than 12% in ΔFEV1 demonstrated significantly lower baseline FEV1% predicted. The responder of greater than 12% in ΔFEV1 compared with non-responder had higher trend proportion of sputum and blood eosinophils prior to treatment (sputum; 6.17±12.0 vs. 4.90±8.52, blood 7.15±5.18 vs. 4.88±3.72). Although the scores of AQLQ were increased after 4 wks of inhaled GCs, there was no difference of the scores of AQLQ at baseline and after treatment between responder and non-responder (Fig. 2). Also there was no difference of the scores of AQLQ at baseline and after treatment in terms of asthma severity and atopy. Duration of asthma, age, sputum eosinophils, blood eosinophils, FEV1% predicted at baseline, and PC20 methacholine were not correlated with AQLQ.

Fig. 1.

The changes of AQLQ scores after inhaled glucocorticoids for 4wks in moderate to severe patients with asthma. A; baseline, B; 4 weeks, *p<0.05 compared with baseline values.

Table 2.

Quality of life score, spirometry following inhaled glucocorticoids for 4 wks compared with baseline value prior to treatment

*Plus-minus values are mean±SD. FEV1, forced expiratory volume in one second. FVC, forced vital capacity; FEF, forced expiratory flow. AQLQ score, asthma quality of life score.

Fig. 2.

Change in overall AQLQ scores between responder and non-responder after inhaled glucocorticoids for 4 wks.

DISCUSSION

Quality of life scores and FEV1% predicted were improved in patients with moderate to severe asthma after high dose inhaled GCs, indicating that AQLQ as well as pulmonary function test may be an additive clinical parameter for effectiveness of GCs treatment in patients with asthma.

Clinical trials in asthma have studied on physiological measures of outcome such as airway caliber (15) and responsiveness (16). Questionnaires on asthma symptoms and treatment requirements have been used to assess clinical severity, but they have tended to be restricted to conventional clinical symptoms and have not taken into the impact of the symptoms and other aspects of the disease on the patients' lives. Asthma is associated with significant impairments of quality of life. Specific quality of life scales include questions targeted to asthma; many studies have been employed in clinical trials (17-21).

GCs, usually administered by means of inhalation, are potent inhibitors of inflammatory responses and therefore are currently considered to be the standard therapeutic regimen for the treatment of persistent asthma (22). GCs treatment of asthmatic patient reduces the numbers of infiltrating eosinophils and lymphocytes in the airways and decreases production and release of pro-inflammatory mediators and cytokines. As a consequence, some of the structural abnormalities of asthmatic airways are normalized after GCs treatment (23). In our study, responder asthmatic patients had higher trend of blood and sputum eosinophils prior to inhaled GCs, indicating that asthma patients with eosinophilic airway inflammation may be more responsible to inhaled GCs.

It is now well documented (24, 25), in both adults and children, that long-term treatment with inhaled GCs suppresses the disease by affecting the underlying airway inflammation. As a result, symptoms disappeared and lung function improves. The outcome parameter responding most rapidly to the initiation of inhaled steroid therapy is symptoms, PEF values improve gradually, while improvements in AHR may continue over many months or even years. Inhaled GCs may also modify the disease outcome if prescribed early enough and long enough. In this study we evaluated effect of high dose inhaled GCs to exclude dose dependent effect of GCs. We found that significant increase in FEV1 was observed at 4 wks in patients with asthma received high dose inhaled GCs. The responsiveness to inhaled GCs was diverse among patients with asthma.

The scores of AQLQ were used as a tool to measure outcome of drug treatment. Measurement of AQLQ may show benefits of asthma treatments not revealed by objective monitoring and can complement clinical and physiological assessments of treatment outcome (16, 20, 21, 26-29). In this study, we found that the scores of AQLQ in terms of overall and each item were improved after treatment of inhaled GCs, indicating that the AQLQ is valuable as the conventional clinical variables considered important in measuring asthma control. The correlations between pulmonary function and AQLQ scores not observed in this study, which was in consistent with Marks et al. (30). In contrast with Juniper et al. (27, 29) correlations between severity and AQLQ scores not observed due to the smaller sample size. Also age, atopy, duration of asthma, PC20 methacholine was not correlated with AQLQ scores.

The scores of AQLQ in terms of overall and each item were improved after treatment of GCs for 4wks, suggesting that the AQLQ can be used as a measure of outcome in GCs responsiveness in asthma.

Footnotes

This work was supported by a grant from the Korea Health 21 R&D Project, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (01-PJ3-PG6-01GN04-003 and 0412-CR03-0704-0001).

References

- 1.Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. NHLBI/WHO workshop report. Bethesda, Md: National Institutes of Health National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; 2002. NIH publication no. 02-3659. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;110:S141–S219. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blaiss MS. Outcomes analysis in asthma. JAMA. 1997;278:1874–1880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guyatt GH, Feeny DH, Patrick DL. Measuring health-related quality of life. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118:622–629. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-8-199304150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Juniper EF. Quality of life in adults and children with asthma and rhinitis. Allergy. 1997;52:971–977. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.1997.tb02416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barnes PJ. Inhaled glucocorticoids for asthma. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:868–875. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503303321307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamada AK, Szefler SJ, Martin RJ, Boushey HA, Chinchilli VM, Drazen JM, Fish JE, Israel E, Lazarus SC, Lemanske RF. Issues in the use of inhaled glucocorticoids. The Asthma Clinical Research Network. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153:1739–1748. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.6.8665030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amirav I, Goren A, Pawlowski NA. What do pediatricians in training know about the correct use of inhalers and spacer devices? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1994;94:669–675. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(94)90173-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Thoracic Society. Lung function testing: selection of reference values and interpretative strategies. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;144:1202–1218. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/144.5.1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Standards for the diagnosis and care of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987;136:225–244. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/136.1.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park JW, Cho YS, Lee SY, Nahm DH, Kim YK, Kim DG, Sohn JW, Park JK, Jee YK, Cho YJ, Yoon HJ, Kim MK, Park HS, Choi BW, Choi IS, Park CS, Min KU, Moon HB, Park SH, Lee YK, Kim NS, Hong CS. Multi-center study for the utilization of quality of life questionnaire for adult Korean asthmatics (QLQAKA) J Asthma Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;20:467–480. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Juniper EF, Cockcroft DW, Hargreave FE. Histamine and methacholine inhalation tests: A laboratory tidal breathing protocol. ed 2. Lund: Astra Draco; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Norzila MZ, Fakes K, Henry RL, Simpson J, Gibson PG. Interleukin-8 secretion and neutrophil recruitment accompanies induced sputum eosinophil activation in children with acute asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:769–774. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.3.9809071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pizzichini MM, Pizzichini E, Clelland L, Efthimadis A, Mahony J, Hargreave FE. Sputum in severe exacerbation of asthma: Kinetics of inflammatory indices after prednisone treatment. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:1501–1508. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.5.9154849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park CS, Kim YY, Kang SY. Correlation between RAST and skin test for inhalant offending allergens. J Korean Soc Allergol. 1983;3:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horn CR, Clark TJ, Cochrane GM. Inhaled therapy reduces morning dips in asthma. Lancet. 1984;I:1143–1145. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)91392-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Juniper EF, Kline PA, Vanzieleghem MA, Ramsdale EH, O'Byrne PM, Hargreave FE. Effect of long-term treatment with an inhaled corticosteroid (budesonide) on airway hyperresponsiveness and clinical asthma in nonsteroid dependent asthmatics. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;142:832–836. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/142.4.832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katz PP, Yelin EH, Eisner MD, Earnest G, Blanc PD. Performance of valued life activities reflected asthma-specific quality of life more than general physical function. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57:259–267. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mancuso CA, Peterson MG. Different methods to assess quality of life from multiple follow-ups in a longitudinal asthma study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57:45–54. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(03)00248-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moy ML, Fuhlbrigge AL, Blumenschein K, Chapman RH, Zillich AJ, Kuntz KM, Paltiel AD, Kitch BT, Weiss ST, Neumann PJ. Association between preference-based health-related quality of life and asthma severity. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2004;92:329–334. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61570-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Epstein RS, Ferrie PJ, Jaeschke R, Hiller TK. Evaluation of impairment of health related quality of life in asthma: development of a questionnaire for use in clinical trials. Thorax. 1992;47:76–83. doi: 10.1136/thx.47.2.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marks GB, Dunn SM, Woolcock AJ. An evaluation of an asthma quality of life questionnaire as a measure of change in adults with asthma. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46:1103–1111. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90109-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lim S, Jatakanon A, John M, Gilbey T, O'Connor BJ, Chung KF, Barnes PJ. Effect of inhaled budesonide on lung function and airway inflammation: Assessment by various inflammatory markers in mild asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:22–30. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.1.9706006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laitinen LA, Laitinen A, Haahtela T. A comparative study of the effects of an inhaled corticosteroid, budesonide, and a beta 2-agonist terbutaline on airway inflammation in newly diagnosed asthma: a randomized, double-blind parallel group controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1992;90:32–42. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(06)80008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laitinen LA, Laitinen A, Heino M, Haahtela T. Eosinophilic airway inflammation during exacerbation of asthma and its treatment with inhaled corticosteroid. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;143:423–427. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/143.2.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Toogood JH, Baskerville JC, Jennings B, Lefcoe NM, Johansson SA. Influence of dosing frequency and schedule on the response of chronic asthmatics to the aerosol steroid, budesonide. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1982;70:288–298. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(82)90065-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holgate ST, Chuchalin AG, Hebert J, Lotvall J, Persson GB, Chung KF, Bousquet J, Kerstjens HA, Fox H, Thirlwell J, Cioppa GD. Efficacy and safety of a recombinant anti-immunoglobulin E antibody (omalizumab) in severe allergic asthma. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34:632–638. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.1916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Juniper EF, Jenkins C, Price MJ, James MH. Impact of inhaled salmeterol/ fluticasone propionate combination product versus budesonide on the health-related quality of life of patients with asthma. Am J Respir Med. 2002;1:435–440. doi: 10.1007/BF03257170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Banov C, Howland WC, 3rd, Lumry WR, Parasuraman B, Uryniak T, Liljas B. Budesonide turbuhaler delivered once daily improves health-related quality of life in adult patients with non-steroid-dependent asthma. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2003;24:129–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Juniper EF, Svensson K, O'Byrne PM, Barnes PJ, Bauer CA, Lofdahl CG, Postma DS, Pauwels RA, Tattersfield AE, Ullman A. Asthma quality of life during 1 year of treatment with budesonide with or without formoterol. Eur Respir J. 1999;14:1038–1043. doi: 10.1183/09031936.99.14510389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marks GB, Dunn SM, Woolcock AJ. A scale for the measurement of quality of life in adults with asthma. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:461–472. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90095-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]