INTRODUCTION

Taste buds are peripheral sensory organs that respond to a wide variety of sapid chemicals. Mammalian taste cells are classified into four categories on the basis of their cytological and ultrastructural features: Type I, II, III, and basal cells (reviewed by Roper 1989). Basal cells are progenitor cells that restock the taste bud during its normal course of cell turnover. Type I cells are believed to be supporting cells. Type III cells form ultrastructurally recognizable synapses with primary afferent sensory nerve processes (25) and are considered by many investigators to generate a final output signal from gustatory end organs. Importantly, it is just now being recognized that Type II cells are likely to be the initial sensory receptor cells. This realization stems from recent observations that the molecular machinery for taste transduction, including G protein-coupled taste receptors (GPCRs) and downstream effectors are expressed only in Type II cells (5, 1, 41, 42). Although sensory afferent fibers come into close contact with Type II cells, there are no classical ultrastructural specializations indicating the presence of synapses (8). This raises the conundrum that chemosensory transduction takes place in one type of cell (Type II) but output signals from taste buds appear to arise from another cell type (Type III). If this is the case, cell-cell signaling must occur within the peripheral sensory organs of taste.

Chemical synapses and gap junctions between taste cells have been identified and might be routes for cell-cell signaling (40, 32, 4), but little is known about these candidates for signal coupling. One possibility is that groups of 2 to 5 taste cells are united into a “gustatory processing unit” by gap junctions (40, 43). Cells within the processing unit might share electrical signals and/or second messengers such as IP3 via the gap junctions. Paracrine secretion of norepinephrine, glutamate, serotonin, CCK, VIP, and other transmitters within the taste bud may be another route of cell-cell signaling (16, 12, 7, 19, 20, 23). Lastly, taste cells conceivably communicate directly with each other and with closely apposed sensory afferent fibers via novel mechanisms not involving conventional synapses.

Thus, there are 3 possible routes for cell-cell interactions within taste buds: (a) interactions via paracrine secretions, (b) transmission via conventional synapses, and (c) communication via gap junctions. If these cell-cell interactions take place, identifying the transmitters will be paramount to sorting out the synaptic logic of signal processing in taste buds. Candidates for paracrine secretions and synaptic neurotransmitters in taste buds have been proposed, including norepinephrine, acetylcholine, ATP, glutamate, and peptides (reviewed by Nagai et al. 1996; Yamamoto et al. 1998; Herness et al. 2004). However, to date, serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine; 5HT) has been one of the best studied candidates, although whether it is a paracrine secretion, a conventional synaptic neurotransmitter, or both is not yet clear. 5HT has been identified with HPLC in mammalian taste tissues (44). Histochemical and immunocytochemical techniques have demonstrated that 5HT is present in a subset of type III taste cells in circumvallate and foliate papillae of mouse, rat, rabbit, and monkey (13, 24, 26, 37, 42) and in basal-like Merkel cells in amphibian taste buds (34, 38, 9). By using autoradiographic techniques with H3-labelled 5HT and exploiting the large taste cells in Necturus taste buds, researchers demonstrated that certain taste cells selectively take up 5HT and release it in a Ca2+-dependent manner when depolarized (27). Ren et al. (1999) reported that the Na-dependent 5HT transporter, SET, was expressed in rat taste cells. These workers suggested that the actions of 5HT, released from one cell and acting on other cells within the taste bud, was terminated by this transporter. Early reports with patch clamp recordings indicated that bath-applied 5HT modulates Ca2+ currents in amphibian taste cells: Ca2+ current in some cells was up-regulated and in other cells it was down-regulated (9). These actions were believed to be mediated by 5HT1a-like receptors. Later studies by Herness and his colleagues, also using patch clamp electrophysiology, showed that 5HT decreased K+ and Na+ currents in mammalian taste cells (17). Ewald and Roper (1994) impaled adjacent taste cells in the large taste buds of Necturus and found that depolarizing one cell led to a hyperpolarization in a subset of adjacent cells. This hyperpolarization was mimicked by bath-applying 5HT. Finally, RT-PCR and immunostaining have indicated that mammalian taste buds express certain subtypes of 5HT receptors, with 5HT1a receptors occurring on cells within taste buds and 5HT3 receptors on nerve fibers innervating taste buds (23).

Taken collectively, the above findings suggest the following scenario: in response to gustatory stimulation, (a) certain taste cells secrete 5HT onto adjacent taste cells (paracrine secretion) to modulate surrounding taste cell activity via metabotropic receptors (5HT1a); (b) taste cells (specifically, serotonergic Type III) also release 5HT onto primary afferent fibers to excite them via ionotropic (5HT3) receptors (synaptic transmission). A crucial missing link in this scenario is whether 5HT is released during gustatory stimulation. This link is the focus of our findings. Namely, we have used 5HT-sensitive biosensor cells to unambiguously identify serotonin as one of the transmitters released from mouse taste bud cells during taste transduction. These data are published in full in Huang et al. (21).

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Biosensor cells

CHO cells expressing 5HT2c receptors (2) were seeded into 35 mm diameter culture dishes. To produce biosensors, cells were suspended in Hanks Buffered Saline Solution (HBSS) containing 0.125% trypsin and collected in a 15 ml centrifuge tube after terminating the reaction with 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Dispersed CHO cells were loaded with 4 μM Fura-2 acetoxymethyl ester (Fura-2AM) for 1 hr at room temperature. An aliquot of Fura-loaded cells was transferred to a recording chamber and viewed with an Olympus IX70 inverted microscope to test their responses to bath-applied 5HT, KCl, cycloheximide, acetic acid, and saccharin. Sequential fluorescence microscopic images were recorded with a long pass emission filter (≥ 510 nm) with the cells excited at 340 followed by 380 nm, and the ratios calculated with Indec Workbench v5 software. Data shown are these ratios, labeled F340/F380 in the figures.

Isolated taste buds

We removed the lingual epithelium containing taste papillae from the tongues of adult C57BL/6J female mice by injecting a cocktail of 1 mg/ml collagenase A (Roche), 2.5 mg/ml dispase II (Roche), and 1 mg/ml trypsin inhibitor (Sigma) directly under the epithelium surrounding taste papillae. The peeled epithelium was bathed in Ca-free solution 30 minutes at room temperature and isolated taste buds were drawn into fire-polished glass micropipettes with gentle suction. Taste buds were transferred to a shallow recording chamber having a glass coverslip base. The coverslip was coated with Cell-Tak (BD Biosciences) to hold the taste buds firmly in place. Taste buds were perfused with Tyrode solution (in mM; 140 NaCl, 5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 10 glucose, 10 Na-pyruvate, 5 NaHCO3, pH 7.4, 310–320 Osm).

Stimulation

Taste buds were stimulated by bath-perfusion of KCl (50 mM substituted equimolar for NaCl); cycloheximide (10–100 μM); sodium saccharin (2–20 mM), aspartame (1–10 mM), and acetic acid (8 mM). All stimuli were made up in Tyrode solution and applied at pH 7.2 except for acetic acid (pH 5).

Immunohistochemistry

Isolated taste buds were fixed for 10 minutes in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Taste buds were then rinsed 3 times in PBS and incubated for 2 hours in PBS containing 0.3% triton X-100, 2% normal donkey serum, and 2% bovine serum albumin. Taste buds were incubated with rabbit polyclonal anti-serotonin antibodies (1:1000, Sigma catalog #S5545) for 60 to 90 minutes at room temperature. Thereafter, taste buds were washed 3 times in PBS, incubated for 1 hour in Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (1:500; Molecular Probes), and then washed again 3 times in PBS.

RESULTS

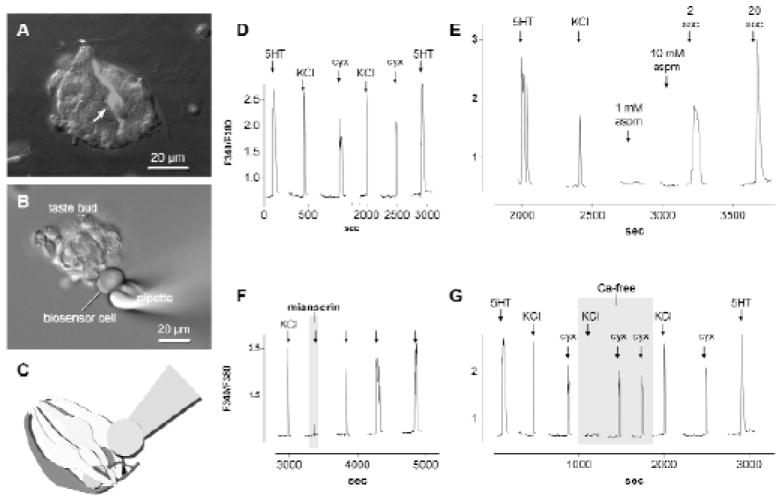

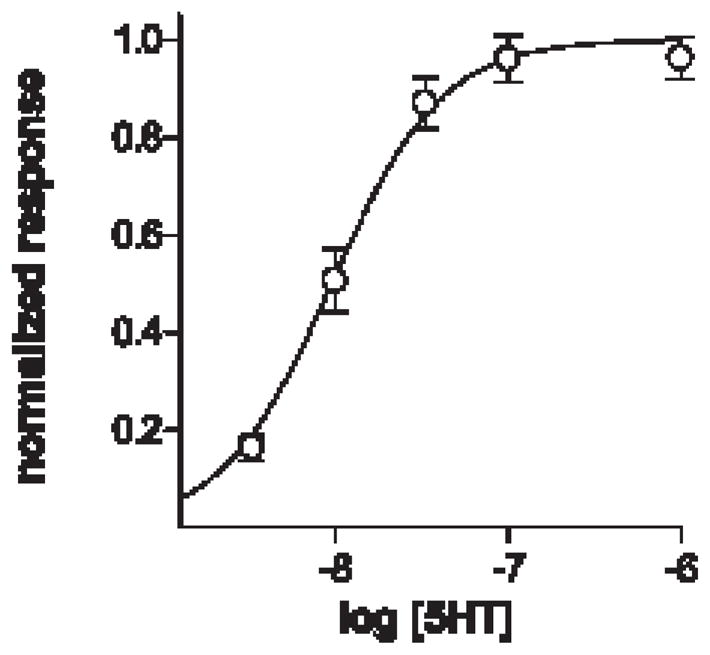

We used CHO-K1 cells stably expressing 5HT2c receptors (2) to produce biosensors for detecting the release of serotonin from stimulated taste buds. We suspended these “CHO/5HT2c cells” in buffer and loaded them with the Ca2+-sensitive dye, Fura 2, to detect intracellular Ca2+ transients. Bath-applied 5HT rapidly increased intracellular Ca2+. The threshold for activation was ~ 3 nM and the EC50 was ~ 9 nM (Fig. 1). These cells became our biosensors to explore 5HT release from taste buds.

Fig. 1. Serotonin elevates Ca2+ in CHO cells transfected with 5HT2c receptors.

Concentration-response plot for 5HT. Responses were measured as Fura 2 emission ratios, F340/F380, and normalized to the ratios at 1 μM 5HT. EC50 ~ 9 nM. Points show mean ± s.e.m. (N = 31 cells from 2 experiments), sigmoidal non-linear regression curve fitted with Prism v4 (GraphPad). Adapted from Huang et al., 2005.

CHO cells express endogenous purinoceptors and muscarinic acetylcholine receptors which, in principle, might confound the origin of responses generated in CHO/5HT2c cells. The purinoceptors, but not the muscarinic receptors, are coupled to Ca2+ signaling. Accordingly, fura-loaded CHO cells increased [Ca2+]i in response to ATP but not to ACh (up to 1 mM). To distinguish purinergic from serotonergic responses in CHO/5HT2c biosensors, we used a selective 5HT2c antagonist, mianserin. Ca2+ elevations in responses to 5HT were reversibly and reliably blocked by 10 nM mianserin but ATP responses were unaffected. Thus, even though CHO cells express endogenous receptors, the specific transmitter involved can be determined by applying selective antagonists.

Although CHO/5HT2c cells responded to serotonin, they did not respond to depolarization with bath-applied KCl (50 mM, substituted for NaCl). CHO/5HT2c cells also did not respond to bath-applied taste stimuli – cycloheximide (100 μM), a well-established bitter taste compound for rodents, or to saccharin (20 mM), a sweet-tasting compound. CHO/5HT2c cells also did not respond to a sour stimulus – acetic acid (8 mM, pH 5). Furthermore, CHO/5HT2c cells maintained their responses to bath-applied serotonin even if Ca2+ in the medium was replaced with Mg2+, consistent with the coupling of 5HT2c to intracellular Ca2+ release mechanisms.

These data demonstrate that (a) Fura 2-loaded CHO/5HT2c cells are sensitive and reliable biosensors for 5HT; (b) responses to 5HT can be differentiated from responses to ATP by applying mianserin; and (c) CHO/5HT2c biosensor cells do not respond directly to taste stimuli or depolarization with KCl.

Next, we transferred an aliquot of suspended Fura 2-loaded CHO/5HT2c cells into a chamber containing freshly-isolated mouse taste buds. After the CHO/5HT2c cells had settled to the base of the chamber, we superperfused 3 nM serotonin to identify a biosensor that manifested a robust response. The identified cell was then drawn onto a fire-polished glass micropipette with gentle suction and maneuvered to an isolated taste bud (Fig. 2B, C). Mere physical contact between the biosensor cell and the taste bud did not elicit a response, nor did bath perfusion with Tyrode solution. However, in approximately 30% of the recordings, perfusing the chamber with KCl, cycloheximide, or saccharin evoked rapid and repeatable biosensor responses (Fig. 2D, E). We attribute the 30% success rate as due to the likelihood of positioning the biosensor over or near to a synaptic release site. Responses to bath-applied stimuli were abolished if the biosensor cell was withdrawn only a few microns from the isolated taste bud and responses returned when the biosensor was re-positioned in the identical location on the taste bud. Thus, the taste bud was the source of the agent that produced a response.

Fig. 2. Biosensor cells detect serotonin released from isolated taste buds.

A. a fixed, isolated taste bud immunostained for serotonin. At least one immunopositive taste cell (arrow) is visible. The lingual epithelium was incubated with 500 μM hydroxytryptophan (5HTP) prior to isolating this taste bud (see later).

B. a Fura 2-loaded biosensor cell abutted against an isolated taste bud in a living preparation. In both A and B, Nomarski differential interference contrast and fluorescence microscopy images were merged.

C. cartoon showing placement of a biosensor onto an isolated taste bud in a configuration used for the experiments described in this report, as in B.

D. Ca2+ elevation in a 5HT biosensor cell positioned against a taste bud as in B, C. Bath-applied 3 nM 5HT (↓) was used initially to verify the sensitivity of the biosensor, followed by 50 mM KCl to depolarize taste cells and 100 μM cycloheximide (cyx). The lingual epithelium had been incubated with 500 μM 5HTP to elevate 5HT in taste cells. Responses evoked by depolarization and taste stimulation are enhanced by this procedure. All subsequent records were recorded from taste buds isolated from epithelium incubated in 5HTP.

E. saccharin, but not aspartame, elicts 5HT release from taste buds. Biosensor responses were elicited by perfusing KCl, 2 mM and 20 mM saccharin (sac), but neither 1 mM nor 10 mM aspartame (aspm) were effective stimuli.

F. Mianserin, a 5HT2c receptor antagonist, reversibly reduces 5HT biosensor responses. Responses were evoked by depolarizing taste buds with 50 mM KCl (↓). 1 nM mianserin was present during the time indicated by the shaded region. Mianserin also reversibly blocked responses evoked by saccharin, cycloheximide, and acetic acid (data not shown).

G. 5HT release from taste buds depends on Ca2+ influx for KCl depolarization but not for taste stimulation with a bitter (cycloheximide) compound. Sequential biosensor responses from an isolated taste bud stimulated with 50 mM KCl (↓) or 100 μM cycloheximide (cyx, ↓). The 5HT biosensor was calibrated at the beginning and end of the recording with 3 nM serotonin (5HT, ↓). During the shaded region, Ca2+ in the bath (2 mM) was exchanged for 8 mM Mg2+.

Adapted from Huang et al., 2005.

Although serotonergic signals were recorded by stimulating freshly isolated taste buds, biosensor responses were significantly enhanced by incubating the lingual epithelium in 500 μM 5-hydroxytryptophan (5HTP), the immediate precursor to 5HT, for 30 minutes prior to isolating taste buds. Responses to bath-applied stimuli were reversibly blocked by the 5HT2c receptor antagonist mianserin (1 nM, Fig. 2F). Collectively, these tests verify that 5HT was the compound released from stimulated taste buds and the the biosensor responses were not due, for example, to the secretion of other compound(s) from taste buds during stimulation.

As described above, prototypic bitter (cycloheximide) and sweet (saccharin) stimuli elicited 5HT release when applied to isolated taste buds at taste-appropriate concentrations. Importantly, aspartame, a sweet tastant for humans but not for rodents, did not elicit 5HT release from mouse taste buds, even at high concentration (Fig. 2E). This supports our interpretation that 5HT release is taste-specific. In addition, sour stimulation (8 mM acetic acid, pH 5) elicited 5HT release from taste buds (data not shown). We did not test salt or umami stimuli. It is difficult to stimulate isolated taste buds with NaCl because the buffer itself contains 112 mM NaCl and elevating this produces a hypertonic solution. Applying glutamate (umami tastant) is complicated by the presence of basolateral synaptic glutamate receptors that are quite sensitive to the amino acid (6).

Identifying sources of Ca2+ for transmitter release

We tested whether the release of serotonin from taste buds was Ca2+-dependent. Magnesium (8 mM) was substituted for Ca2+ (2 mM) in the bath, and taste buds were stimulated with KCl and taste stimuli, as before. In the case of KCl depolarization and acid stimulation, replacing Ca2+ with Mg2+ rapidly and reversibly blocked serotonin release (e.g., Fig. 2G for KCl stimulation), consistent with influx of Ca2+ through depolarization-gated Ca channels and consistent with conventional synaptic mechanisms. Surprisingly, 5HT release elicited by cycloheximide (Fig. 2G) or saccharin (not shown) was not affected by replacing Ca2+ with Mg2+. Cycloheximide and saccharin are known to stimulate intracellular Ca2+ release in taste cells via a signaling cascade involving PLCβ2 and IP3 (3, 35, 15, 45). Thus, a likely source of Ca2+ for the 5HT release elicited by these compounds was an intracellular store (endoplasmic reticulum). Because pharmacological approaches to test this notion would also affect the CHO/5HT2c biosensor, we adopted a different approach that used taste buds isolated from PLCβ2-null mutant mice (22). No tastant-evoked intracellular Ca2+ release would be expected in taste cells from these mice. These mutant taste buds released 5HT in response to bath-applied KCl but yielded no detectable 5HT release in response to cycloheximide or saccharin. These findings are consistent with the source of Ca2+ for tastant-evoked transmitter release being intracellular stores (via a PLCβ2 signaling cascade).

DISCUSSION

These data indicate that 5HT is one of the neurotransmitters released by taste cells in response to gustatory stimulation and that certain stimuli evoke 5HT release in response to Ca2+ derived from intracellular stores. Our findings, however, do not indicate where serotonin is acting postsynaptically. Serotonin may be an excitatory transmitter between taste cells and primary sensory afferent fibers (36, 11, 28). Serotonin may also be a paracrine secretion and modulate activity of cells within the taste bud (14, 12, 23). Our experiments were not designed to distinguish between these possibilities, both of which remain open questions.

5HT release from taste cells appears to depend on two sources of Ca2+. For depolarizing and sour stimuli (here, KCl and acetic acid, respectively), Ca2+ influx was necessary and (for KCl at least) sufficient to elicit serotonin release. For tastants (cycloheximide, saccharin) that stimulate G protein-coupled receptors, 5HT release was not blocked by replacing extracellular Ca2+with Mg2+. Possible explanations for this include: (1) replacing Ca2+ with Mg2+ in the bath did not totally eliminate Ca2+. Residual Ca2+ in the chamber, albeit low, might have sufficed to elicit 5HT release (29); (2) 5HT release in taste buds is Ca2+-independent and perhaps mediated by neurotransmitter transporters (Schwartz 2002); (3) 5HT release evoked by tastants is triggered by Ca2+ from internal stores. Our finding that exchanging Ca2+ for Mg2+ totally abolished depolarization-evoked release argues against the first possibility. To our knowledge, there are no data that support or negate transporter-mediated 5HT release in taste buds (the second possibility). Our findings with the PLCβ2 knockout mice argue in favor of the last explanation.

SUMMARY

CHO cells transfected with high-affinity 5HT receptors were used to detect and identify the release of serotonin from taste buds. Taste cells release 5HT when depolarized or when stimulated with bitter, sweet, or sour tastants. Sour- and depolarization-evoked release of 5HT from taste buds is triggered by Ca2+ influx from the extracellular fluid. In contrast, bitter- and sweet-evoked release of 5HT is triggered by Ca2+ derived from intracellular stores.

References

- 1.Adler E, Hoon MA, Mueller KL, Chandrashekar J, Ryba NJ, Zuker CS. A novel family of mammalian taste receptors. Cell. 2000;100:693–702. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80705-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berg KA, Clarke WP, Sailstad C, Saltzman A, Maayani S. Signal transduction differences between 5-hydroxytryptamine type 2A and type 2C receptor systems. Mol Pharmacol. 1994;46:477–484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernhardt SJ, Naim M, Zehavi U, Lindemann B. Changes in IP3 and cytosolic Ca2+ in response to sugars and non-sugar sweeteners in transduction of sweet taste in the rat. J Physiol. 1996;490:325–336. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bigiani A, Roper SD. Estimation of the junctional resistance between electrically coupled receptor cells in Necturus taste buds. J Gen Physiol. 1995;106:705–725. doi: 10.1085/jgp.106.4.705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boughter JD, Jr, Pumplin DW, Yu C, Christy RC, Smith DV. Differential expression of alpha-gustducin in taste bud populations of the rat and hamster. J Neurosci. 1997;17:2852–2858. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-08-02852.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caicedo A, Jafri MS, Roper SD. In situ Ca2+ imaging reveals neurotransmitter receptors for glutamate in taste receptor cells. J Neurosci. 2000a;20:7978–7985. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-21-07978.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caicedo A, Kim KN, Roper SD. Glutamate-induced cobalt uptake reveals non-NMDA receptors in rat taste cells. J Comp Neurol. 2000b;417:315–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clapp TR, Yang R, Stoick CL, Kinnamon SC, Kinnamon JC. Morphologic characterization of rat taste receptor cells that express components of the phospholipase C signaling pathway. J Comp Neurol. 2004;468:311–321. doi: 10.1002/cne.10963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Delay RJ, Kinnamon SC, Roper SD. Serotonin modulates voltage-dependent calcium current in Necturus taste cells. J Neurophysiol. 1997;77:2515–2524. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.5.2515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Delay RJ, Taylor R, Roper SD. Merkel-like basal cells in Necturus taste buds contain serotonin. J Comp Neurol. 1993;335:606–613. doi: 10.1002/cne.903350411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Esakov AI, Golubtsov KV, Solov’eva NA. The role of serotonin in taste reception in the frog Rana temporaria. J Evolut Biochem Physiol. 1983;19:62–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ewald DA, Roper SD. Bidirectional synaptic transmission in Necturus taste buds. J Neurosci. 1994;14:3791–3804. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-06-03791.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fujimoto S, Ueda H, Kagawa H. Immunocytochemistry on the localization of 5-hydroxytryptamine in monkey and rabbit taste buds. Acta Anat (Basel) 1987;128:80–83. doi: 10.1159/000146320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujita T, Kanno T, Kobayashi S. The paraneuron. Tokyo: Springer-Verlag; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gilbertson TA, Damak S, Margolskee RF. The molecular physiology of taste transduction. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2000;10:519–527. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00118-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herness MS. Vasoactive intestinal peptide-like immunoreactivity in rodent taste cells. Neuroscience. 1989;33:411–419. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90220-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herness S, Chen Y. Serotonin inhibits calcium-activated K+ current in rat taste receptor cells. Neuroreport. 1997;8:3257–3261. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199710200-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herness S, Zhao FL, Kaya N, Shen T, Lu SG, Cao Y. Communication routes within the taste bud by neurotransmitters and neuropeptides. Chem Senses; Proceedings of the 14th International Symposium on Olfaction and Taste; Kyoto. 2004. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herness S, Zhao FL, Kaya N, Lu SG, Shen T, Sun XD. Adrenergic signalling between rat taste receptor cells. J Physiol. 2002a;543:601–614. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.020438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herness S, Zhao FL, Lu SG, Kaya N, Shen T. Expression and physiological actions of cholecystokinin in rat taste receptor cells. J Neurosci. 2002b;22:10018–10029. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-22-10018.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang Y-J, Maruyama Y, Lu K-S, Pereira E, Plonsky I, Baur JE, Wu D, Roper SD. Mouse taste buds use serotonin as a neurotransmitter. J Neurosci. 2005;25:843–847. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4446-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang H, Kuang Y, Wu Y, Xie W, Simon MI, Wu D. Roles of phospholipase C beta2 in chemoattractant-elicited responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:7971–7975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.15.7971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaya N, Shen T, Lu SG, Zhao FL, Herness S. A paracrine signaling role for serotonin in rat taste buds: expression and localization of serotonin receptor subtypes. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;286:R649–658. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00572.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim DJ, Roper SD. Localization of serotonin in taste buds: a comparative study in four vertebrates. J Comp Neurol. 1995;353:364–370. doi: 10.1002/cne.903530304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murray RG. Cellular relations in mouse circumvallate taste buds. Microsc Res Tech. 1993;26:209–224. doi: 10.1002/jemt.1070260304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nada O, Hirata K. The occurrence of the cell type containing a specific monoamine in the taste bud of the rabbit’s foliate papilla. Histochem. 1975;43:237–240. doi: 10.1007/BF00499704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nagai T, Delay RJ, Welton J, Roper SD. Uptake and release of neurotransmitter candidates, [3H]serotonin, [3H]glutamate, and [3H]gamma-aminobutyric acid, in taste buds of the mudpuppy, Necturus maculosus. J Comp Neurol. 1998;392:199–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nagai T, Kim DJ, Delay RJ, Roper SD. Neuromodulation of transduction and signal processing in the end organs of taste. Chem Senses. 1996;21:353–365. doi: 10.1093/chemse/21.3.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Piccolino M, Pignatelli A. Calcium-independent synaptic transmission: artifact or fact? Trends Neurosci. 1996;19:120–125. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)80017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ren Y, Shimada K, Shirai Y, Fujimiya M, Saito N. Immunocytochemical localization of serotonin and serotonin transporter (SET) in taste buds of rat. Brain Res Mol, Brain Res. 1999;74:221–224. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(99)00253-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roper SD. The cell biology of vertebrate taste receptors. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1989;12:329–353. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.12.030189.001553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roper SD. The microphysiology of peripheral taste organs. J Neurosci. 1992;12:1127–1134. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-04-01127.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schwartz EA. Transport-mediated synapses in the retina. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:875–891. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00010.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Solov’eva NA, Krokhina EM, Esakov AI. Possible nature of the biogenic amine in the dumbbell-shaped cells of frog taste buds. Biull Eksp Biol Med. 1978;86:596–598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spielman AI, Nagai H, Sunavala G, Dasso M, Breer H, Boekhoff I, Huque T, Whitney G, Brand JG. Rapid kinetics of second messenger production in bitter taste. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:C926–931. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.270.3.C926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takeda M. Uptake of 5-hydroxytryptophan by gustatory cells in the mouse taste bud. Arch Histol Jpn. 1977;40:243–250. doi: 10.1679/aohc1950.40.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Uchida T. Serotonin-like immunoreactivity in the taste bud of the mouse circumvallate papilla. Jpn J Oral Biol. 1985;27:509–521. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Whitear M. Merkel cells in lower vertebrates. Arch Histol Cytol. 1989;52(Suppl):415–422. doi: 10.1679/aohc.52.suppl_415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamamoto T, Nagai T, Shimura T, Yasoshima Y. Roles of chemical mediators in the taste system. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1998;76:325–348. doi: 10.1254/jjp.76.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang J, Roper SD. Dye-coupling in taste buds in the mudpuppy, Necturus maculosus. J Neurosci. 1987;7:3561–3565. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-11-03561.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang R, Tabata S, Crowley HH, Margolskee RF, Kinnamon JC. Ultrastructural localization of gustducin immunoreactivity in microvilli of type II taste cells in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 2000;425:139–151. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20000911)425:1<139::aid-cne12>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yee CL, Yang R, Bottger B, Finger TE, Kinnamon JC. “Type III” cells of rat taste buds: immunohistochemical and ultrastructural studies of neuron-specific enolase, protein gene product 9.5, and serotonin. J Comp Neurol. 2001;440:97–108. doi: 10.1002/cne.1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yoshii K. Gap junctions among taste bud cells in mouse fungiform papillae. Proceedings of the 14th International Symposium on Taste and Smell; Kyoto. 2004. p. 46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.ZANCANARO C, SBARBATI A, BOLNER A, ACCORDINI C, PIEMONTE G, OSCULATI F. Biogenic amines in the taste organ. Chem Senses. 1995;20:329–335. doi: 10.1093/chemse/20.3.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang Y, Hoon MA, Chandrashekar J, Mueller KL, Cook B, Wu D, Zuker CS, Ryba NJ. Coding of sweet, bitter, and umami tastes: different receptor cells sharing similar signaling pathways. Cell. 2003;112:293–301. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00071-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]