Abstract

Radiosurgery is defined as the use of highly focused beams of radiation to ablate a pathologic target, thus achieving a surgical objective by noninvasive means. Recent advances have allowed a wide variety of intracranial lesions to be effectively treated with radiosurgery, and radiosurgical treatment has been accepted as a standard part of the neurosurgical armamentarium. The advent of frameless radiosurgery now permits radiosurgical treatment to all parts of the body and is being actively explored by many centers. This article reviews some of the modern tools for radiosurgical treatment and discusses the current clinical practice of radiosurgery.

Stereotaxis has made the depths of the brain accessible to surgery and the use of radiation has made it possible to operate through the intact skull.

—Lars Leksell, Stereotaxis and Radiosurgery (1)

With these words, Lars Leksell summarized the guiding principle of radiosurgery: to use highly focused, precisely aimed beams of radiation to ablate a pathological target with the same finality as surgical resection. The requirement of ablation distinguished this nascent field from that of radiotherapy, and the clear advantages of safety—no risk of infection, bleeding, or disfigurement—permitted treatment of tumors that were inaccessible to surgery. The combination of radiation technology and the surgical philosophy of ablation led to Leksell's coinage of the word radiosurgery.

Radiosurgery was initially limited to the brain because of the requirement of a stereotactic frame attached to the skull to provide a coordinate system for tumor localization. Recent advances, however, allow radiosurgical treatment throughout the body without such frames, and new protocols are being written for tumors of the lung, liver, pancreas, kidney, and other sites. These developments are some of the most exciting in the field of radiation oncology.

This article reviews some of the modern radiosurgical tools and the new developments that allow radiosurgical treatment outside the brain. It then discusses the current practice of radiosurgery for the brain and spine along with recent results. A future paper will describe preliminary results in extracranial radiosurgery.

RADIOSURGERY: THE TOOLS

Leksell's idea and the Gamma Knife

The central idea of radiosurgery, attributed to Leksell, is to aim a large number of beams of radiation at the desired target from many directions (Figure 1). The target receives a dose from each beam, whereas all other sites receive only a single dose. In this fashion the radiation is “focused” upon the target at the central point with minimal exposure to surrounding tissue.

Figure 1.

Schematic showing the central idea of radiosurgery. The target (shown in red) receives a dose from each beam of radiation, whereas any other site receives a dose from only a single beam.

Leksell refined his radiosurgical devices over many years to culminate in the current version of the Gamma Knife (1). At the heart of this system is a large metal collimator consisting of a dome-shaped shell perforated with 201 holes that transmit the radiation to its center point (Figure 2). The patient's head is placed within the collimator so that the target lies at this center. Although the radiation is maximal at the target point itself, the radiation falls to zero rapidly as the distance from this center point increases. The result is that the volume of tissue receiving 50% or less of this maximum amount is a tightly focused sphere of radiation centered at the desired target.

Figure 2.

The Gamma Knife. The inset shows the collimator with 201 holes allowing 201 beams of radiation. During treatment, the Gamma Knife doors (arrow) open and the couch moves into the unit to position the head under the cobalt sources. Main photo courtesy of Elekta.

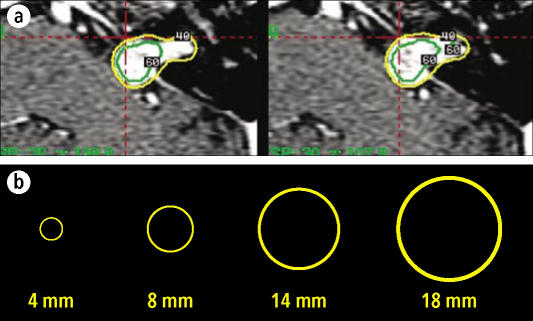

A single sphere of radiation is obtained each time the patient's head is inserted into the Gamma Knife, and spheres at different centers can be produced by slight changes of the head position at each insertion. In this fashion, a complex tumor can be covered by spheres during a single treatment (Figure 3). The process is facilitated by the availability of collimators of various sizes, which produce spheres with diameters of 4, 8, 14, or 18 mm. The overall accuracy of the Gamma Knife system is 1 mm or less (2).

Figure 3.

(a) Gamma Knife plans showing coverage of tumor with a 40% isodose line (shown in yellow) obtained by superimposing different spheres. (b) The Gamma Knife system includes collimators allowing creation of spheres of 4, 8, 14, and 18 mm.

The stereotactic frame

To position the head so that the desired target is at the center of the collimator, a stereotactic frame is anchored to the skull with four screws that penetrate the outer table. This box-shaped device is worn during the radiologic studies and contains fiducial markers appearing on the images, which are used by a computer algorithm to specify how the frame is to be attached to the collimator to align the target at the center. The newest version of the Gamma Knife is equipped with robotic motors that move the frame automatically from one location to another during complex treatments. The frame is placed with the aid of light sedation and a local anesthetic and is usually well tolerated.

Case example 1

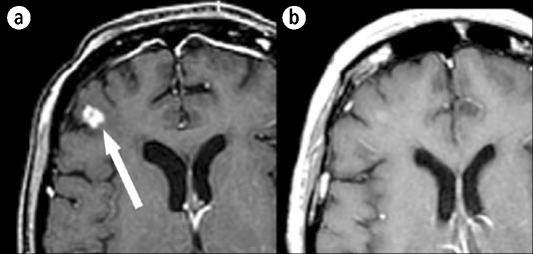

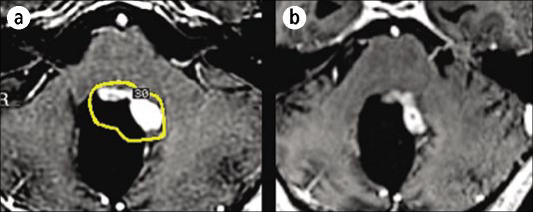

A 57-year-old woman with non–small cell lung cancer developed multiple intracranial metastatic lesions 5 months following diagnosis and was treated with whole brain radiotherapy. Her radiologic studies improved, but a magnetic resonance (MR) image obtained 1 year after radiotherapy showed progression of lesions, including a right frontal and right cerebellar lesion. She underwent Gamma Knife radiosurgery to treat 17 separate lesions. Three months following radiosurgery, all lesions were smaller or stable and her neurologic status was unchanged (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

An MR image of a 57-year-old woman with non–small cell lung cancer, described in case example 1. (a) The right frontal lobe lesion at the time of Gamma Knife treatment. (b) The same region 3 months after treatment.

A different idea: the CyberKnife

The necessity for a stereotactic frame imposes several important limitations. First, lesions outside the head cannot be treated. Second, fractionated treatments extending over several days cannot be delivered without a prolonged and impractical use of the frame. Finally, some patients (e.g., infants) cannot be treated because they cannot tolerate rigid frame fixation. A frameless system would therefore allow treatment of tumors anywhere in the body, permit the use of fractionated schedules, and extend radiosurgery to other patient populations.

The CyberKnife is a recently developed frameless stereotactic system that has enjoyed widespread acceptance (3, 4). It consists of a modified linear accelerator mounted on a robotic system that moves slowly around the patient, delivering several beams of radiation at each of many stopping points (Figure 5). Stereotactic precision is achieved without a rigid frame by means of two x-ray systems mounted in the CyberKnife vault, which are used to obtain periodic images of the skull. Any patient motion is detected by these images, and that information is used by the robot to compensate and keep the linear accelerator on target: in effect, the CyberKnife “tracks” the patient. The overall accuracy of the system is reported to be 1.1 ± 0.3 mm (4, 5).

Figure 5.

The CyberKnife. Arrow indicates the modified linear accelerator. Photo courtesy of Accuray.

Because the CyberKnife does not require a stereotactic frame, treatments can be given in a fractionated fashion, with smaller doses given over several days rather than one large dose on a single day. The theoretical benefit of this hypofractionated or staged regimen is a smaller risk of damage to surrounding normal tissue. For example, a hypofractionated regimen was reported recently for the treatment of acoustic neuromas in which the rate of hearing preservation was higher than that found in conventional radiosurgery (6). Although experience is early, many centers routinely use hypofractionated schedules to avoid complications for tumors that are large, located near eloquent structures, or surrounded by edema.

Although the initial use of the CyberKnife was for radiosurgery of the brain, extension to tumors elsewhere in the body is more challenging and has required several technical refinements. For example, the anatomy of the spine is too complex for the system to track with x-rays alone, necessitating the placement of internal fiducial markers—small, 2-mm stainless steel screws placed in the spinal lamina adjacent to the desired target—that are “tracked” by the system during treatment even during complex movement of the spine. The fiducials are placed during a percutaneous outpatient procedure prior to radiosurgical treatment. A wide variety of spinal lesions, including metastatic lesions, cord tumors, and arteriovenous malformations (AVMs), have been treated (7, 8).

Radiosurgery of other organs requires that the CyberKnife system also compensate for respiratory movement. The internal fiducial markers used for the spine are insufficient because x-rays cannot be taken quickly enough to track the respiratory cycle. The needed step is the placement of external markers on the skin that can be tracked continuously by infrared signals (similar to systems used for intraoperative navigation) and periodic registration of the movement of the internal fiducials with that of the external fiducials. A mathematical model is then built that relates the movement between these two sets of fiducials and allows the external fiducials—tracked continuously—to predict the movement of the internal fiducials and thus of the tumor. In this fashion, tumors in organs that move with respiration can be continuously tracked to allow precise radiosurgical treatment (9–11).

The advances that allow extracranial radiosurgery are very recent, and protocols to distinguish optimal dosing and clinical strategies are under way. This new capability is emerging as a valuable and exciting oncological tool.

Case example 2

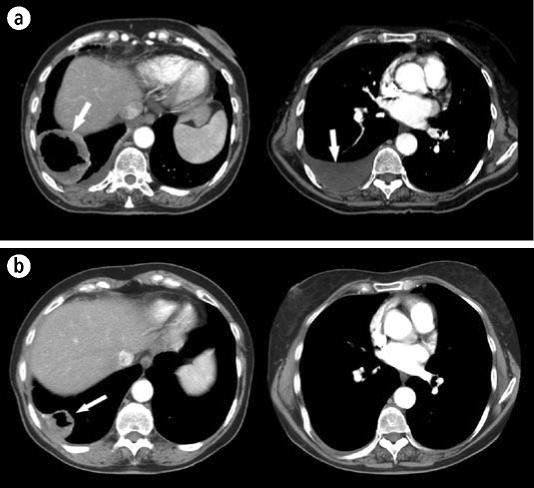

A 65-year-old woman presented with a 7-cm right lower lobe cavitary lesion, a large right pleural effusion, a 2-cm left lingular lesion, and left hilar adenopathy. Positron emission tomography (PET) computed tomography showed hypermetabolic uptake in the lung lesions and hilum but no evidence of distant disease. Biopsy of the cavitary lesion showed non–small cell carcinoma, later staged as stage IV T2N1M1. She was symptomatic with right lower back discomfort and a single episode of hemoptysis. Although palliative external beam radiation alone was considered at an outside facility, she was referred for CyberKnife lung radiosurgery.

Because standard treatment with either chemotherapy alone or palliative large-field standard external beam radiation was thought to have little chance of local control with significant risks of morbidity, radiosurgery was chosen to obtain more durable local control and to limit morbidity. Both lung lesions were treated with CyberKnife radiosurgery using a hypofractionated course of three fractions of 14 Gy each to obtain a biologically effective dose of over 100 Gy. Although the lingular lesion was not symptomatic, it was treated since the likelihood for tumor control was high and the potential for morbidity low with radiosurgery compared with standard treatment. The hilar adenopathy was not treated due to concern for potential bronchial fistula. Chemotherapy was planned following radiosurgery. Six weeks after the lung radiosurgery, there was a marked response, with resolution of the pleural effusion, near resolution of the left lingular mass, and significant shrinkage of the cavitary right lower lobe tumor. The patient was asymptomatic prior to initiation of chemotherapy (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

The patient described in case example 2. (a) A computed tomography scan of the chest at the time of CyberKnife treatment showing a large tumor (left) and pleural effusion (right). (b) The same regions 6 weeks after treatment. The tumor is significantly smaller, and pleural effusion has resolved. Arrows indicate tumor and effusion.

RADIOSURGERY: THE APPLICATIONS

This section summarizes some of the major applications of contemporary radiosurgery.

Metastatic disease

Radiosurgery is well suited for the treatment of metastatic lesions because these lesions are usually relatively small and round. Numerous reports document local control rates of 80% to 100% for a variety of tumor types (where local control generally means lack of growth), with rates of symptomatic radionecrosis of about 5% (12–16). For example, Gerosa (13) reported a local control rate of 93% with a mean follow-up of 14 months after treatment of 1307 metastatic lesions in 804 patients; Sheehan (12) reported an 84% control rate with a mean time to tumor progression of 12 months of 627 metastatic lesions in 273 patients with non–small cell lung cancer; Amendola (16) found a 94% local control rate with a median follow-up of 7.8 months in 68 patients with breast cancer; Radbill (17) found an 81% local control rate with a median follow-up of 25 weeks (median survival, 26 weeks) in 188 lesions in 51 patients with melanoma; and Wowra (18) found an actuarial local control rate of 95% at 1.5 years following radiosurgery in 350 lesions in 75 patients with renal cell carcinoma.

Radiosurgical treatment of metastatic lesions also seems to have salutary effects upon survival. Several recent reports (a total of 354 patients) show a median survival of about 10 months following radiosurgery of metastatic lesions (19–23), comparing favorably to that of surgical resection (10.8 months) and surgical resection combined with whole brain radiotherapy (12 months) (24). A recent prospective, randomized trial showed a longer median survival when radiosurgery was added to whole brain radiotherapy for one to three metastatic lesions (6.5 vs 4.9 months); the median survival of patients with a favorable clinical status (RPA1) was 11.6 months (25). Local control and functional status were also improved with radiosurgery. Finally, preliminary results of a prospective randomized trial (26) show a median survival of 17 months for patients with single lesions treated with radiosurgery. The addition of whole brain radiotherapy did not significantly alter the mean survival (18 months) but did reduce the number of new lesions from 45% to 15%.

Radiosurgical treatment of metastatic brain lesions can confer improvements in local control, survival, and quality of life with low morbidity. Radiosurgical treatment is quick and noninvasive and can be used repeatedly as new lesions arise. Optimal therapy may be a combination of radiosurgery and radiotherapy, and radiosurgery can be effective if radiotherapy fails or lesions recur. These features have made the treatment of metastatic disease the most common use of radiosurgery for the brain.

Figure 4 shows the response of a metastatic lesion to radiosurgery. The following example illustrates that radiosurgery may be used repeatedly and aggressively with good results.

Case example 3

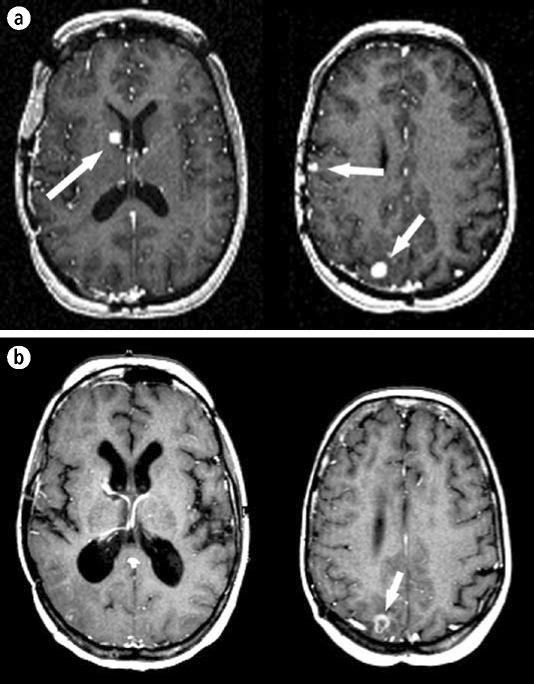

A 48-year-old woman with ovarian cancer underwent craniotomy for resection of a metastatic lesion and was subsequently treated with whole brain radiotherapy. New intracranial lesions were discovered and treated over the next few years as follows: two new lesions discovered 12 months after craniotomy were treated with the Gamma Knife; three new lesions discovered 5 months later were treated with the Gamma Knife; seven new lesions discovered 6 months later were treated with the Gamma Knife; three new lesions discovered 16 months later were treated with the Gamma Knife; two new lesions discovered 2 years later were treated with the Gamma Knife; two new lesions discovered 11 months later were treated with the CyberKnife; and two new lesions discovered 20 months later were treated with the CyberKnife. Seven years after the appearance of her first intracranial metastatic lesions and following the treatment of 20 lesions with seven radiosurgical procedures, her tumors are controlled and she remains neurologically intact (Figure 7). Her course should be compared with estimates of a median survival of 7 months for patients with intracranial metastatic ovarian carcinoma (27).

Figure 7.

The patient described in case example 3. (a) An MR image of the head showing three lesions (arrows) due to metastatic ovarian cancer. (b) The same regions 6 years after treatment. Two of the lesions have resolved and one is smaller (arrow).

Gliomas

Radiosurgery is often incorporated into treatment protocols for gliomas with the hope that local control might lead to improved survival despite the infiltrative nature of these tumors. Although the most common use of radiosurgery in these settings is as a salvage procedure for tumor progression after conventional radiotherapy, some centers choose radiosurgery as an upfront measure at the onset of disease. This latter approach has been studied in a recent prospective, randomized trial that showed no survival benefit nor benefit of quality of life when radiosurgery was used prior to radiotherapy in patients with glioblastoma multiforme (28). Nevertheless, many believe that radiosurgery can play an important role in the treatment of progressive gliomas, and several series suggest a benefit of radiosurgery for recurrent glioblastoma when the enhancing portions of the tumor are targeted (29–31). The issue has been reviewed by McDermott et al (32), who suggest that results could be improved if the most metabolically active portions of the tumor are targeted using MR spectroscopy or PET scanning. Finally, some studies show high rates of local control for unresectable pilocytic astrocytomas (33).

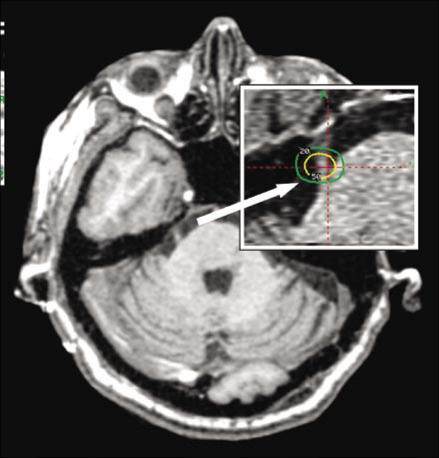

Although there may be little benefit of radiosurgery as an initial treatment of glioblastoma, it is reasonable to offer radiosurgical treatment of the enhancing portions of progressive or recurrent high-grade gliomas. Incorporation of physiological information derived from MR spectroscopy or PET scans may increase the benefit of radiosurgery for these difficult tumors (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

An MR scan of a 17-year-old male with a pilocytic astrocytoma treated with resection followed by external beam radiotherapy. (a) The tumor outlined by a 30% isodose line on the day of Gamma Knife treatment. (b) The same region 3 months later showing a significant decrease in tumor size. The dose was 13.5 Gy to the 30% isodose line.

Acoustic neuromas

Acoustic neuromas (vestibular schwannomas) are benign tumors arising from the vestibular nerve. These tumors can damage the seventh and eighth nerve, brain stem, and fifth nerve as they slowly grow in the confined space of the posterior fossa. Surgical approaches include the translabyrinthine approach, which sacrifices hearing, and the suboccipital approach, which can preserve hearing. In addition to the morbidity associated with major intracranial procedures, a major surgical consideration is the risk of injury to the facial nerve, which can exceed 25% for large tumors, even in expert hands (34).

For tumors exerting a symptomatic mass effect on the brain-stem or causing hydrocephalus, prompt surgical resection is the treatment of choice. For other tumors that are growing slowly, radiosurgical treatment has evolved and is now considered a competing (and in some cases superior) option to resection. Lunsford et al reported a local control rate of 97% in 829 cases at 10 years with a risk of facial neuropathy of <1% (35), and Prasad et al (36) reported a local control rate of 94% in 153 cases with a permanent facial neuropathy rate of 1%. Whether hypofractionated radiosurgery can improve rates of hearing loss is controversial, although a hearing preservation rate of 74% has been reported in a group of patients with an average tumor diameter of 18.5 mm followed for a minimum of 36 months after treatment (6). If confirmed by future studies, this rate is a significant improvement over those reported after resection (34).

Radiosurgical treatment of acoustic neuromas has become an accepted option. Of interest is a recent successful lawsuit filed against a physician when discussion of radiosurgical treatment was omitted from preoperative counseling (37).

Meningiomas, pituitary tumors, and other benign tumors

Radiosurgery can provide local control for a variety of benign tumors just as it does for acoustic neuromas. Control rates for meningiomas are >90% (38–40) in series with follow-up of 5 to 10 years, with morbidity depending on the location and size of the tumor. Although complete surgical resection of these lesions may be preferable to radiosurgical treatment, Pollock (38) found that radiosurgical treatment was equivalent to a Simpson grade 1 resection for meningiomas <35 mm in diameter. Furthermore, many difficult lesions cannot be completely removed without a high risk of damage to important structures (such as cranial nerves) to which the tumor adheres. The option of leaving behind a small but troublesome portion of the tumor for subsequent radiosurgical treatment has altered surgical strategy in most centers.

Although radiosurgery provides a local control rate of 90% for pituitary tumors (41), initial treatment is usually surgical resection. Radiosurgery is particularly useful when the tumor invades the cavernous sinus and cannot be completely resected. Disadvantages of radiosurgical treatment include a long latency until hormonal secretion is controlled (42) and a limitation of dose if the tumor presses into the radiosensitive optic apparatus (43).

Some have argued that the possibility of radiation-induced malignancy should preclude the use of radiosurgery for benign tumors, and there have been a few reports of new malignant tumors following radiosurgery. However, the risk of this complication is low—only three cases of malignancy following radiosurgical treatment of benign lesions have been reported (44) in more than 170,000 radiosurgical procedures for benign lesions (according to the Elekta website, http://www.elekta.com)—and is comparable to the risk of major anesthetic complications during the surgery that would occur in place of radiosurgical treatment.

Arteriovenous malformations

AVMs are abnormal microscopic fistulae between the arterial and venous circulation that appear as a tangle of blood vessels and present as seizures, neurologic deficit, or hemorrhage. Annual rates of hemorrhage of 3% to 4% prompt most centers to recommend treatment. Surgical resection can be difficult because of the risk of neurologic deficit and the risk of torrential bleeding during the procedure.

Radiosurgery was first used to obliterate an AVM by Steiner (45). By focusing the field upon the AVM nidus (rather than feeding vessels or draining veins), obliteration rates of 50% to 90% can be obtained depending on the size of the AVM. However, obliteration usually does not occur until 2 years after treatment, so the risk of radiosurgery is the risk of the radiation itself (usually 3% to 5%) added to the risk of hemorrhage (3% to 4% per year) until obliteration is complete (46). The comparison of this risk to that of surgical resection is both an essential and complex requirement for each case.

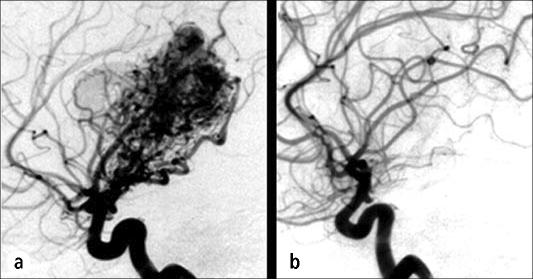

Case example 4

A 28-year-old woman was found to have a 3-cm left thalamic AVM after recovering from an intracranial hemorrhage. The size and location of the lesion precluded resection and embolization. She was treated with Gamma Knife radiosurgery (13 Gy to a 30% isodose line surrounding the nidus of the AVM). Several months later she developed a mild right hemiparesis, and her MR image showed increased T2 signal in the region of the AVM. Her symptoms improved with steroids but worsened when she stopped the steroids without medical advice. Three years after treatment, she is neurologically intact except for a slight limp, and her angiogram shows that the AVM has vanished (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

The patient described in case example 4. (a) An angiogram showing a thalamic arteriovenous malformation on the day of Gamma Knife treatment. (b) An angiogram 3 years after treatment showing resolution of the malformation.

Brain tumors in children

Malignant brain tumors are the most common solid tumors of childhood and are unfortunately often more aggressive than those of adults. Many centers include Gamma Knife radiosurgery in their protocols for older children. The efficacy and morbidity seem to be similar to those for adults, establishing radiosurgical treatment for pediatric disease.

The situation for babies and younger children is more desperate for two reasons. First, malignant brain tumors in younger children tend to be more aggressive than those in adults. Second, conventional radiation therapy cannot be given to young patients without a high risk of devastating cognitive decline in later life (47). Although many pediatric oncologists will temporize with surgery and chemotherapy until the patient is old enough to tolerate radiation, the inability to freely use radiation therapy is a major disadvantage. Third, although Gamma Knife radiosurgery would offer the opportunity for local treatment while avoiding the widespread exposure that would lead to later cognitive problems, the fragile skulls of these young patients are not suitable for the rigid frame fixation required by Gamma Knife radiosurgery.

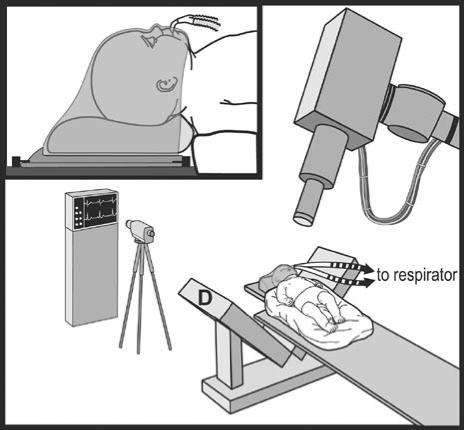

Fortunately, the CyberKnife does not require a frame and so would seem to be ideally suited for the treatment of these young patients. The feasibility of this approach has been recently shown (48, 49), with acceptable rates of efficacy and morbidity. The CyberKnife allows radiosurgical treatment of children when other radiotherapy is prohibited (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Schematic of the setup for CyberKnife treatment of infants. D indicates the x-ray detector of the CyberKnife system. Reprinted with permission from reference 48.

Trigeminal neuralgia

Trigeminal neuralgia—an excruciating, lancinating type of facial pain that can be severe enough to lead to suicide—usually occurs in the distribution of one or two branches of the trigeminal nerve. It is thought to be caused by irritation of the nerve by a nearby vessel. Medical treatment is usually effective initially but often fails, and surgical treatment is directed at moving the offending vessel during a posterior fossa craniotomy (microvascular decompression) or by partly damaging the trigeminal complex with a percutaneous approach. Success rates of these procedures are high: excellent results (98% pain free without medication) are seen in 75.2% of patients 1 year following microvascular decompression and in 63.5% after 10 years (50). Rates of complete pain relief for percutaneous procedures are approximately 80% after 1 year and >50% after 5 years (51).

Gamma Knife radiosurgery is commonly used as a noninvasive way to induce partial damage of the trigeminal nerve in these patients (Figure 11). Initial reports claimed high rates of efficacy, although recent reports have refined these data. Although only about one third of patients treated with radiosurgery become pain free (52, 53), these patients are typically those who have failed microvascular decompression or percutaneous procedures. Furthermore, one recent review indicates that the efficacy of radiosurgery is similar to that of the percutaneous procedures for patients who have not undergone other procedures, but radiosurgery has a lower rate of disturbing facial numbness (51). Radiosurgery can also be safely repeated if the pain recurs, adding to the overall rate of success (54).

Figure 11.

An MR image showing the trigeminal nerve. The inset shows targeting used in Gamma Knife radiosurgery for trigeminal neuralgia (the green line is the 20% isodose line and the yellow line is the 50% isodose line).

We believe that radiosurgical treatment of trigeminal neuralgia is not as effective as other surgical procedures but has a useful role when the other procedures have failed, when the patient does not want the facial numbness required by percutaneous procedures, or when the patient is unable to undergo conventional surgery.

Spinal lesions

As described before, the radiosurgical treatment of spinal lesions requires placement of small fiducial markers in the lamina adjacent to the tumor. Ryu showed the feasibility of this approach in 16 patients with a variety of spinal lesions treated with 11 to 25 Gy in one to five fractions with the CyberKnife. No morbidity or progression was seen with a minimum follow-up of 6 months (7). Gerszten et al (8) reported 125 cases of spinal tumors with a median follow-up of 18 months following CyberKnife treatment. Seventy-nine of the patients were treated for pain related to their lesion, and improvement in pain was seen in 74 of these patients after 1 month. An additional 14 benign tumors and 30 of 32 malignant tumors did not progress after treatment.

Although early, the experience with radiosurgery for spinal lesions is encouraging.

GOALS AND ADVANTAGES OF RADIOSURGERY

The doses of radiation that can be safely used in radiosurgery are far higher than the equivalent doses used in conventional radiotherapy because the radiosurgical plan spares the surrounding normal tissue from high levels of radiation. This may explain the efficacy of radiosurgery in treating “radioresistant” tumors such as renal cell carcinoma and melanoma (17, 18).

Radiosurgery can be used in combination with conventional radiotherapy to give a “boost” to the tumor. Radiosurgical treatment is also frequently effective for recurrences after radiotherapy and can be repeated for multiple recurrences. Furthermore, tumors that are inaccessible to surgery can often be treated with a radiosurgical plan. Finally, because the focal plans of radiosurgery minimize the dose to normal tissues, aggressive strategies including high doses and multiple treatments are feasible.

An important advantage of radiosurgery is that it is noninvasive. There are no incisions and virtually no risk of infection, no hair is shaved, and most patients return to their activity the following day. Radiosurgery can be offered to patients who are poor surgical candidates and does not consume much of the patient's time.

LIMITATIONS AND RISKS OF RADIOSURGERY

The efficacy of radiosurgery is lower and the risk of complications is higher for tumors that are large or that have been treated with radiation in the past. For example, most centers use reduced doses, and accept a lower rate of efficacy, for tumors >3 cm in diameter in order to avoid radionecrosis. Similar concerns hold for tumors that are surrounded by edema. However, radiosurgery is commonly used in patients who have received prior conventional radiotherapy.

A particularly vexing limitation of radiosurgery is imposed by the sensitivity of the optic nerves and optic chiasm to radiosurgical doses. Most centers limit the dose to these structures to 8 Gy (compared with doses of 15 to 20 Gy to treat meningiomas and metastatic lesions, respectively). Because of these limitations, treatment of tumors adjacent to the optic chiasm such as meningiomas can be technically demanding, and treatment of tumors such as optic gliomas can be impossible.

The risk of radiosurgical damage to the other cranial nerves seems to be lower than the risk to the optic nerve. For example, meningiomas of the cavernous sinus commonly involve cranial nerves III through VI, and marginal doses of 15 to 17 Gy are well tolerated. The same is true for tumors of the skull base engulfing the lower cranial nerves. The risks to the facial and trigeminal nerves are also relatively low and have been discussed in the acoustic neuroma and trigeminal neuralgia sections, respectively.

Radionecrosis is a feared risk of radiosurgery and refers to a combination of cytotoxic and microvascular tissue injury within the treated field as a consequence of the delivered radiation. The onset of injury may be delayed several months following treatment and usually persists for months. The injury may be asymptomatic or may mimic a severe stroke and require steroids, hyperbaric oxygen, or surgical decompression.

The risk of radionecrosis increases with higher doses and with larger treatment volumes, and clinicians typically choose doses to minimize these risks. For example, guidelines for doses yielding specific risks for various volumes of an AVM nidus are available (46), and the general goal is to limit the risk to 5%. The risk of radionecrosis when treating primary brain tumors and brain metastases has been studied in a randomized trial (55). Single-fraction doses of 24, 18, and 15 Gy for tumors of maximum diameter ≤20, 21–30, and 31–40 mm, respectively, yielded an actuarial incidence of radionecrosis of 11% at 24 months following treatment. In our practice, we attempt to limit this risk to approximately 5% by using slightly smaller doses than these levels.

CONCLUSION

A constant stream of technical refinements has improved the delivery of radiosurgery to the brain, has expanded radiosurgical applications, and now allows radiosurgical treatment of virtually any organ in the body. The local control of tumors achieved by radiosurgery confers a survival benefit for patients with metastatic disease, and radiosurgical treatment of lesions such as AVMs and acoustic neuromas is now accepted as an essential part of the neurosurgical arsenal. Although there is reason to be optimistic about radiosurgery for extracranial disease, there is a need for more experience and for directed protocols.

References

- 1.Leksell L. Stereotaxis and Radiosurgery. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mack A, Czempiel H, Kreiner HJ, Durr G, Wowra B. Quality assurance in stereotactic space. A system test for verifying the accuracy of aim in radiosurgery. Med Phys. 2002;29:561–568. doi: 10.1118/1.1463062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adler JR, Murphy MJ, Chang SD, Hancock SL. Image-guided robotic radiosurgery. Neurosurgery. 1999;44:1299–1307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuo JS, Yu C, Petrovich Z, Apuzzo ML. The CyberKnife stereotactic radiosurgery system: description, installation, and an initial evaluation of use and functionality. Neurosurgery. 2003;53:1235–1239. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000089485.47590.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang SD, Main W, Martin DP, Gibbs IC, Heilbrun MP. An analysis of the accuracy of the CyberKnife: a robotic frameless stereotactic radiosurgical system. Neurosurgery. 2003;52:140–146. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200301000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang SD, Gibbs IC, Sakamoto GT, Lee E, Oyelese A, Adler JR., Jr Staged stereotactic irradiation for acoustic neuroma. Neurosurgery. 2005;56:1254–1261. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000159650.79833.2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ryu SI, Chang SD, Kim DH, Murphy MJ, Le QT, Martin DP, Adler JR., Jr Image-guided hypo-fractionated stereotactic radiosurgery to spinal lesions. Neurosurgery. 2001;49:838–846. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200110000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerszten PC, Ozhasoglu C, Burton SA, Vogel WJ, Atkins BA, Kalnicki S, Welch WC. CyberKnife frameless stereotactic radiosurgery for spinal lesions: clinical experience in 125 cases. Neurosurgery. 2004;55:89–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whyte RI, Crownover R, Murphy MJ, Martin DP, Rice TW, DeCamp MM, Jr, Rodebaugh R, Weinhous MS, Le QT. Stereotactic radiosurgery for lung tumors: preliminary report of a phase I trial. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;75:1097–1101. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)04681-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ponsky LE, Crownover RL, Rosen MJ, Rodebaugh RF, Castilla EA, Brainard J, Cherullo EE, Novick AC. Initial evaluation of Cyberknife technology for extracorporeal renal tissue ablation. Urology. 2003;61:498–501. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)02442-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.King CR, Lehmann J, Adler JR, Hai J. CyberKnife radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer: rationale and technical feasibility. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2003;2:25–30. doi: 10.1177/153303460300200104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sheehan JP, Sun MH, Kondziolka D, Flickinger J, Lunsford LD. Radiosurgery for non–small cell lung carcinoma metastatic to the brain: long-term outcomes and prognostic factors influencing patient survival time and local tumor control. J Neurosurg. 2002;97:1276–1281. doi: 10.3171/jns.2002.97.6.1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerosa M, Nicolato A, Foroni R, Zanotti B, Tomazzoli L, Miscusi M, Alessandrini F, Bricolo A. Gamma knife radiosurgery for brain metastases: a primary therapeutic option. J Neurosurg. 2002;97(5 Suppl):515–524. doi: 10.3171/jns.2002.97.supplement. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maor MH, Dubey P, Tucker SL, Shiu AS, Mathur BN, Sawaya R, Lang FF, Hassenbusch SJ. Stereotactic radiosurgery for brain metastases: results and prognostic factors. Int J Cancer. 2000;90:157–162. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20000620)90:3<157::aid-ijc6>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amendola BE, Wolf AL, Coy SR, Amendola M, Bloch L. Brain metastases in renal cell carcinoma: management with gamma knife radiosurgery. Cancer J. 2000;6:372–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amendola BE, Wolf AL, Coy SR, Amendola M, Bloch L. Gamma knife radiosurgery in the treatment of patients with single and multiple brain metastases from carcinoma of the breast. Cancer J. 2000;6:88–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Radbill AE, Fiveash JF, Falkenberg ET, Guthrie BL, Young PE, Meleth S, Markert JM. Initial treatment of melanoma brain metastases using gamma knife radiosurgery: an evaluation of efficacy and toxicity. Cancer. 2004;101:825–833. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wowra B, Siebels M, Muacevic A, Kreth FW, Mack A, Hofstetter A. Repeated gamma knife surgery for multiple brain metastases from renal cell carcinoma. J Neurosurg. 2002;97:785–793. doi: 10.3171/jns.2002.97.4.0785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coffey RJ, Flickinger JC, Bissonette DJ, Lunsford LD. Radiosurgery for solitary brain metastases using the cobalt-60 gamma unit: methods and results in 24 patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1991;20:1287–1295. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(91)90240-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flickinger JC, Kondziolka D, Lunsford LD, Coffey RJ, Goodman ML, Shaw EG, Hudgins WR, Weiner R, Harsh GR IV, Sneed PK, et al. A multi-institutional experience with stereotactic radiosurgery for solitary brain metastasis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1994;28:797–802. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(94)90098-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Auchter RM, Lamond JP, Alexander E, Buatti JM, Chappell R, Friedman WA, Kinsella TJ, Levin AB, Noyes WR, Schultz CJ, Loeffler JS, Mehta MP. A multiinstitutional outcome and prognostic factor analysis of radiosurgery for resectable single brain metastasis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1996;35:27–35. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(96)85008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shirato H, Takamura A, Tomita M, Suzuki K, Nishioka T, Isu T, Kato T, Sawamura Y, Miyamachi K, Abe H, Miyasaka K. Stereotactic irradiation without whole-brain irradiation for single brain metastasis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;37:385–391. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(96)00488-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fernandez-Vicioso E, Suh JH, Kupelian PA, Sohn JW, Barnett GH. Analysis of prognostic factors for patients with single brain metastasis treated with stereotactic radiosurgery. Radiat Oncol Investig. 1997;5:31–37. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6823(1997)5:1<31::AID-ROI5>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patchell RA, Tibbs PA, Regine WF, Dempsey RJ, Mohiuddin M, Kryscio RJ, Markesbery WR, Foon KA, Young B. Postoperative radiotherapy in the treatment of single metastases to the brain: a randomized trial. JAMA. 1998;280:1485–1489. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.17.1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andrews DW, Scott CB, Sperduto PW, Flanders AE, Gaspar LE, Schell MC, Werner-Wasik M, Demas W, Ryu J, Bahary JP, Souhami L, Rotman M, Mehta MP, Curran WJ., Jr Whole brain radiation therapy with or without stereotactic radiosurgery boost for patients with one to three brain metastases: phase III results of the RTOG 9508 randomised trial. Lancet. 2004;363:1665–1672. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16250-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jawahar A, Nanda A, Ampil F, Campbell P, DeLaune A. Phase III randomized trial to assess the efficacy of Gamma Knife radiosurgery with or without XRT for brain metastases; Presented at the 2005 annual meeting of the American Association of Neurological Surgeons, New Orleans, LA; April 18, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 27.McMeekin DS, Kamelle SA, Vasilev SA, Tillmanns TD, Gould NS, Scribner DR, Gold MA, Guruswamy S, Mannel RS. Ovarian cancer metastatic to the brain: what is the optimal management? J Surg Oncol. 2001;78:194–201. doi: 10.1002/jso.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Souhami L, Seiferheld W, Brachman D, Podgorsak EB, Werner-Wasik M, Lustig R, Schultz CJ, Sause W, Okunieff P, Buckner J, Zamorano L, Mehta MP, Curran WJ., Jr Randomized comparison of stereotactic radiosurgery followed by conventional radiotherapy with carmustine to conventional radiotherapy with carmustine for patients with glioblastoma multiforme: report of Radiation Therapy Oncology Group 93-05 protocol. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;60:853–860. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kondziolka D, Flickinger JC, Bissonette DJ, Bozik M, Lunsford LD. Survival benefit of stereotactic radiosurgery for patients with malignant glial neoplasms. Neurosurgery. 1997;41:776–785. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199710000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nwokedi EC, DiBiase SJ, Jabbour S, Herman J, Amin P, Chin LS. Gamma knife stereotactic radiosurgery for patients with glioblastoma multiforme. Neurosurgery. 2002;50:41–46. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200201000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shrieve DC, Alexander E, III, Black PM, Wen PY, Fine HA, Kooy HM, Loeffler JS. Treatment of patients with primary glioblastoma multiforme with standard postoperative radiotherapy and radiosurgical boost: prognostic factors and long-term outcome. J Neurosurg. 1999;90:72–77. doi: 10.3171/jns.1999.90.1.0072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McDermott MW, Berger MS, Kunwar S, Parsa AT, Sneed PK, Larson DA. Stereotactic radiosurgery and interstitial brachytherapy for glial neoplasms. J Neurooncol. 2004;69:83–100. doi: 10.1023/b:neon.0000041873.42938.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hadjipanayis CG, Kondziolka D, Garnder P, Niranjan A, Dagam S, Flickinger JC, Lunsford LD. Stereotactic radiosurgery for pilocytic astrocytomas when multimodal therapy is necessary. J Neurosurg. 2002;97:56–64. doi: 10.3171/jns.2002.97.1.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ojemann RG. Acoustic neuroma (vestibular schwannoma) In: Youmans JR, editor. Neurological Surgery. 4th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1996. pp. 2841–2861. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lunsford LD, Niranjan A, Flickinger JC, Maitz A, Kondziolka D. Radiosurgery of vestibular schwannomas: summary of experience in 829 cases. J Neurosurg. 2005;102(Suppl):195–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prasad D, Steiner M, Steiner L. Gamma surgery for vestibular schwannoma. J Neurosurg. 2000;92:745–759. doi: 10.3171/jns.2000.92.5.0745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ebin v. Kimmelman, New York Supreme Court 119956/97, November 8, 2002

- 38.Pollock BE, Stafford SL, Utter A, Giannini C, Schreiner SA. Stereotactic radiosurgery provides equivalent tumor control to Simpson grade 1 resection for patients with small- to medium-size meningiomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;55:1000–1005. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)04356-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.DiBiase SJ, Kwok Y, Yovino S, Arena C, Naqvi S, Temple R, Regine WF, Amin P, Guo C, Chin LS. Factors predicting local tumor control after gamma knife stereotactic radiosurgery for benign intracranial meningiomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;60:1515–1519. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.05.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kondziolka D, Nathoo N, Flickinger JC, Niranjan A, Maitz AH, Lunsford LD. Long-term results after radiosurgery for benign intracranial tumors. Neurosurgery. 2003;53:815–821. doi: 10.1093/neurosurgery/53.4.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sheehan JP, Niranjan A, Sheehan JM, Jane JA, Jr, Laws ER, Kondziolka D, Flickinger J, Landolt AM, Loeffler JS, Lunsford LD. Stereotactic radiosurgery for pituitary adenomas: an intermediate review of its safety, efficacy, and role in the neurosurgical treatment armamentarium. J Neurosurg. 2005;102:678–691. doi: 10.3171/jns.2005.102.4.0678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang N, Pan L, Wang EM, Dai JZ, Wang BJ, Cai PW. Radiosurgery for growth hormone-producing pituitary adenomas. J Neurosurg. 2000;93(Suppl 3):6–9. doi: 10.3171/jns.2000.93.supplement. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stafford SL, Pollock BE, Leavitt JA, Foote RL, Brown PD, Link MJ, Gorman DA, Schomberg PJ. A study on the radiation tolerance of the optic nerves and chiasm after stereotactic radiosurgery. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;55:1177–1181. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)04380-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McIver JI, Pollock BE. Radiation-induced tumor after stereotactic radiosurgery and whole brain radiotherapy: case report and literature review. J Neurooncol. 2004;66:301–305. doi: 10.1023/b:neon.0000014497.28981.4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Steiner L, Leksell L, Greitz T, Forster DM, Backlund EO. Stereotaxic radiosurgery for cerebral arteriovenous malformations. Report of a case. Acta Chir Scand. 1972;138:459–464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Flickinger JC, Kondziolka D, Maitz AH, Lunsford LD. An analysis of the dose-response for arteriovenous malformation radiosurgery and other factors affecting obliteration. Radiother Oncol. 2002;63:347–354. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(02)00103-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hoppe-Hirsch E, Brunet L, Laroussinie F, Cinalli G, Pierre-Kahn A, Renier D, Sainte-Rose C, Hirsch JF. Intellectual outcome in children with malignant tumors of the posterior fossa: influence of the field of irradiation and quality of surgery. Childs Nerv Syst. 1995;11:340–345. doi: 10.1007/BF00301666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Giller CA, Berger BD, Gilio JP, Delp JL, Gall KP, Weprin B, Bowers D. Feasibility of radiosurgery for malignant brain tumors in infants by use of image-guided robotic radiosurgery: preliminary report. Neurosurgery. 2004;55:916–924. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000137332.03970.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Giller CA, Berger BD, Pistenmaa DA, Sklar F, Weprin B, Shapiro K, Winick N, Mulne AF, Delp JL, Gilio JP, Gall KP, Dicke KA, Swift D, Sacco D, Harris-Henderson K, Bowers D. Robotically guided radiosurgery for children. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005;44:1–7. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jannetta PJ. Outcome after microvascular decompression for typical trigeminal neuralgia, hemifacial spasm, tinnitus, disabling positional vertigo, and glossopharyngeal neuralgia. Clin Neurosurg. 1997;44:331–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lopez BC, Hamlyn PJ, Zakrzewska JM. Systematic review of ablative neurosurgical techniques for the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia. Neurosurgery. 2004;54:973–983. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000114867.98896.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McNatt SA, Yu C, Giannotta SL, Zee CS, Apuzzo ML, Petrovich Z. Gamma knife radiosurgery for trigeminal neuralgia. Neurosurgery. 2005;56:1295–1303. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000160073.02800.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sheehan J, Pan HC, Stroila M, Steiner L, Gamma knife surgery for trigeminal 55. Shaw E, Scott C, Souhami L, Dinapoli R, Kline R, Loeffler J, Farnan N. neuralgia: outcomes and prognostic factors. J Neurosurg. 2005;102:434–441. doi: 10.3171/jns.2005.102.3.0434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hasegawa T, Kondziolka D, Spiro R, Flickinger JC, Lunsford LD. Repeat radio surgery for refractory trigeminal neuralgia. Neurosurgery. 2002;50:494–500. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200203000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shaw E, Scott C, Souhami L, Dinapoli R, Kline R, Loeffler J, Farnan N. Single dose radiosurgical treatment of recurrent previously irradiated primary brain tumors and brain metastases: final report of RTOG protocol 90-05. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;47:291–298. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(99)00507-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]