Abstract

Plant volatiles (PVs) are lipophilic molecules with high vapor pressure that serve various ecological roles. The synthesis of PVs involves the removal of hydrophilic moieties and oxidation/hydroxylation, reduction, methylation, and acylation reactions. Some PV biosynthetic enzymes produce multiple products from a single substrate or act on multiple substrates. Genes for PV biosynthesis evolve by duplication of genes that direct other aspects of plant metabolism; these duplicated genes then diverge from each other over time. Changes in the preferred substrate or resultant product of PV enzymes may occur through minimal changes of critical residues. Convergent evolution is often responsible for the ability of distally related species to synthesize the same volatile.

Plant volatiles (PV) are typically lipophilic liquids with high vapor pressures. Nonconjugated PVs can cross membranes freely and evaporate into the atmosphere when there are no barriers to diffusion. The number of identified volatile chemicals synthesized by various plants exceeds 1000 and is likely to grow as more plants are examined with new methods for detecting and analyzing quantities of volatiles that are often minute (1–3).

PVs serve multiple functions in both floral and vegetative organs, and these roles are not always related to their volatility (1). Most PVs are restricted to specific lineages and are involved in species-specific ecological interactions, leading to their designation as specialized, or secondary, metabolites (4). To humans, pollinator-attracting floral scents have been a source of olfactory pleasure since antiquity, and we also use a large number of aromatic plants as flavorings, preservatives, and herbal remedies (5). Flower and herb aromas may contain many individual chemicals, sometimes with very little overlap in the PV profiles of even closely related species (6). It is unlikely that the observed differences are due entirely to differential gene expression. That most PVs are restricted to a few lineages, both ancient and derived, argues for frequent changes in enzymatic profiles through evolution. Considerable diversity and fast rates of change have also been observed in nonvolatile specialized metabolites in plants, raising similar questions regarding the underlying evolutionary mechanisms (7).

Improvements in analytical techniques and molecular and biochemical methods have made PVs one of the best-studied groups of plant secondary metabolites. Here we describe insights into molecular mechanisms involved in the biosynthesis of PVs and their implications for our understanding of plant metabolic diversity.

PV Biosynthetic Pathways Branch Off from Primary Metabolism

The largest class of PVs is derived from isoprenoid pathways. In plants, both the cytosolic mevalonate and the plastidic methylerythritol phosphate pathways generate the five-carbon compound isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) and its isomer dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP). A plastidic prenyltransferase synthesizes geranyl pyrophosphate (GPP) from the condensation of one IPP molecule and one DMAPP molecule. A second type of plastidic prenyltransferase condenses DMAPP with three IPP molecules to produce geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate (GGPP). In the cytosol, the condensation of one DMAPP molecule with two IPP molecules results in farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP). These pyrophosphate-containing compounds serve as precursors of many primary metabolites (8).

Plants also have enzymes called terpene synthases (TPSs), which catalyze the formation of diverse hemi-, mono-, sesqui-, and diterpene PVs from DMAPP, GPP, FPP, and GGPP,respectively (9). Many distinct TPSs that synthesize monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes (the bulk of terpenoid PVs) have been characterized from various plants (1, 2, 10). Each species contains a number of these mechanistically and structurally related TPSs. For example, the Arabidopsis genome contains 32 genes that appear to encode functional TPSs, including six proven monoterpene synthases and at least two proven sesquiterpene synthases (11).

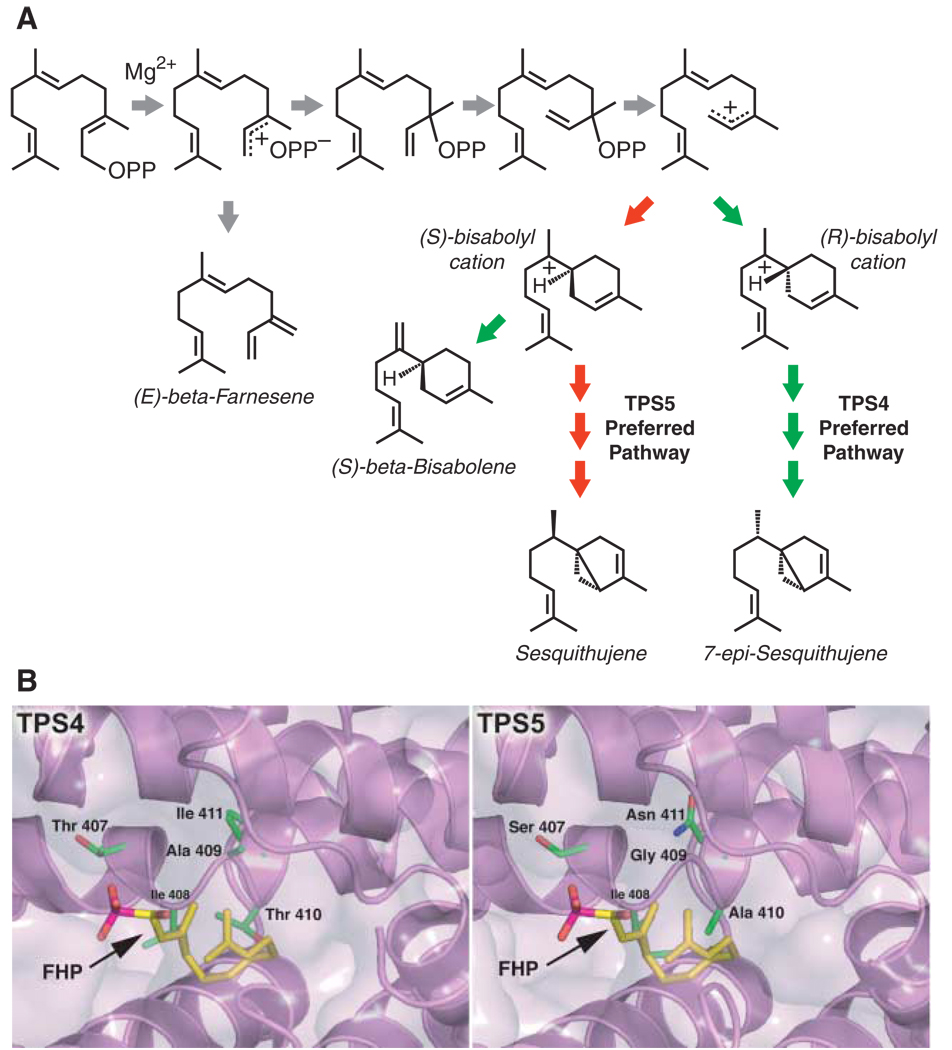

The first step in the reaction catalyzed by TPSs is removal of the pyrophosphate group, leading to a carbocation (Fig. 1A). This highly unstable intermediate can then undergo a number of multistep transformations. The active site of each TPS channels and directs the intermediates through regioand stereochemical rearrangements to produce often one or two major products and a few (or even scores of) minor “derailment” products (9, 11, 12). For example, four residues lining the active-site cavities of two highly related maize TPSs, designated TPS4 and TPS5, control the proportions of sesquiterpenes produced in these enzymes (Fig. 1) (12). Changing only these four residues in TPS5 to those found in TPS4 produced a volatile profile and catalytic efficiency identical to that of native TPS4, even though differences elsewhere in the proteins remained (12).

Fig. 1.

Maize TPS4 and TPS5 catalyze the formation of the same complement of sesquiterpene products, albeit in distinctly different proportions. (A) Abbreviated TPS4 and TPS5 mechanisms accounting for the major products of each enzyme [29% (S)-β-bisabolene, 9% (E)-β-farnesene, 24% 7-epi-sequithujene, and 6% sesquithujene for TPS4; and 27% (S)-β-bisabolene, 13% (E)-β-farnesene, 2% 7-epi-sesquithujene, and 28% sesquithujene for TPS5]. For clarity, only the major products are shown or those products whose levels are considerably different for TPS4 and TPS5. OPP signifies a pyrophosphate. Gray arrows depict pathways equally shared among TPS4 and TPS5. Red and green arrows depict TPS5- and TPS4-preferred pathways, respectively [adapted from (12)]. (B) Active site models of TPS4 and TPS5 based on the crystal structure of tobacco 5-epi-aristolochene synthase (10), shown with the FPP nonhydrolyzable analog farnesyl hydroxyphosphonate (FHP). The four key residues responsible for functional divergence—Thr407, Ala409, Thr410, and Ile411 in TPS4, and Ser407, Gly409, Ala410, and Asn411 in TPS5— are shown as color-coded sticks, with the underlying secondary structure of the three-dimensional models colored lavender.

The second largest class of PVs consists of compounds containing an aromatic ring. Although not all reactions leading to the synthesis of the basic skeletons have been determined, most are derived from intermediates in the pathway that leads from shikimate to phenylalanine and then to an array of primary (such as lignin) and secondary nonvolatile compounds (2). Eugenol (clove essence) is a reduced version of coniferyl alcohol, a lignin precursor (13). Phenylacetaldehyde, a compound present in tomato fruit (14), is derived from phenylalanine by decarboxylation and oxidative removal of the amino group (15). Shortening of the three-carbon side chain of phenylalanine-derived hydroxycinnamates to one carbon also leads to aromatic building blocks such as benzoic acid and benzaldehyde (16). Still other PVs are produced by type III polyketide synthases (PKSs) that use cinnamoyl- and malonyl–coenzyme As (CoAs) as starting material (17).

A third group of PVs is derived by oxidative cleavage and decarboxylation of various fatty acids, resulting in the production of shorter-chain volatiles with aldehyde and ketone moieties (18, 19)that often serve as precursors for the biosynthesis of other PVs (20). Similarly, some volatile terpenes are not derived directly from isoprenoid pyrophosphates but instead from the cleavage of carotenoids by carotenoid cleavage dioxygenases (CCDs) (21). Other PVs, particularly those containing nitrogen or sulfur, are synthesized by cleavage reactions of modified amino acids or their precursors (5). For example, the volatile indole is made in maize by the cleavage of indole-3-glycerol phosphate, an intermediate in tryptophan biosynthesis (22).

Some Modifying Enzymes Can Use Multiple Substrates

A common property of enzymes for specialized metabolites, including PVs, is their proclivity to act on multiple substrates. This promiscuity probably serves as an important cornerstone in the rapid functional divergence of such enzymes. For enzymes with broad substrate specificity, such as some carboxyl methyltransferases and acyltransferases, the availability of a substrate determines the type and amount of formed products. For example, petunia flowers contain a carboxylmethyltransferase that favors salicylic acid over benzoic acid but produces methylbenzoate in planta due to a lack of salicylic acid (23). In contrast, Stephanotis floribunda flowers contain an enzyme with similar properties, but both methylsalicylate and methylbenzoate are produced because both acid substrates are available (24).

Enzymes for the Biosynthesis of PVs Often Belong to Large Families

Specific chemical modifications can convert nonvolatile compounds to volatile ones, enhance the volatility of already volatile chemicals, and alter their olfactory properties. This kind of biosynthetic tailoring is responsible for the combinatorial diversity of non–isoprenoid-derived PVs and also contributes to increasing the number of terpenoid PVs (2).

Sequence analyses of whole genomes and of gene transcripts derived from plant tissues rich in PVs, combined with characterization of the generation of PVs by enzymes encoded by some of these genes, show that plants possess several families of modifying enzymes that catalyze similar reactions but use distinct substrates. For example, the enzymes that methylate the carboxyl group of salicylic and benzoic acids mentioned above are homologous to jasmonic acid carboxylmethyltransferase, producing the PV methyljasmonate found in both floral and vegetative tissues (25). Another family of modifying enzymes consists of acyltransferases, many of which catalyze the transfer of an acetyl group from acetyl-CoA to alcohols such as geraniol (geranyl acetate is a distinct “note” in the scent of roses) and 3-cis-hexen1-ol (3-cis-hexenyl acetate is emitted from the crushed leaves of many species) (20, 26). Enzymes in this family also catalyze the transfer of other acyl groups; for example, from benzoyl-CoA to benzyl alcohol to produce benzylbenzoate in flowers of Clarkia breweri, a California annual (20). Members of another large group of enzymes, the oxidoreductases, have been found to catalyze the oxidation of the monoterpene carveol to carvone (caraway spice) and the reduction of medium-chain fatty acid aldehydes to alcohols (27, 28).

PV Modification Enzymes Often Evolve from Non-PV Enzymes

The genome of Arabidopsis contains 272 genes belonging to the cytochrome P450 oxidase family. A few such P450s participate in PV biosynthesis, such as the oxidative cleavage of fatty acids to produce volatile aldehydes, whereas others contribute to primary metabolism or nonvolatile secondary metabolism (18, 29). Given the extreme diversity of P450s in Arabidopsis, we can expect to find similarly large P450 groups in other plants. Some of these enzymes probably function in PV biosynthesis. Indeed, a P450 responsible for the hydroxylation of the monoterpene limonene in the menthol pathway in mint has been described (30). The families of oxidoreductases, methyltransferases, and acetyltransferases may be similarly diverse (2).

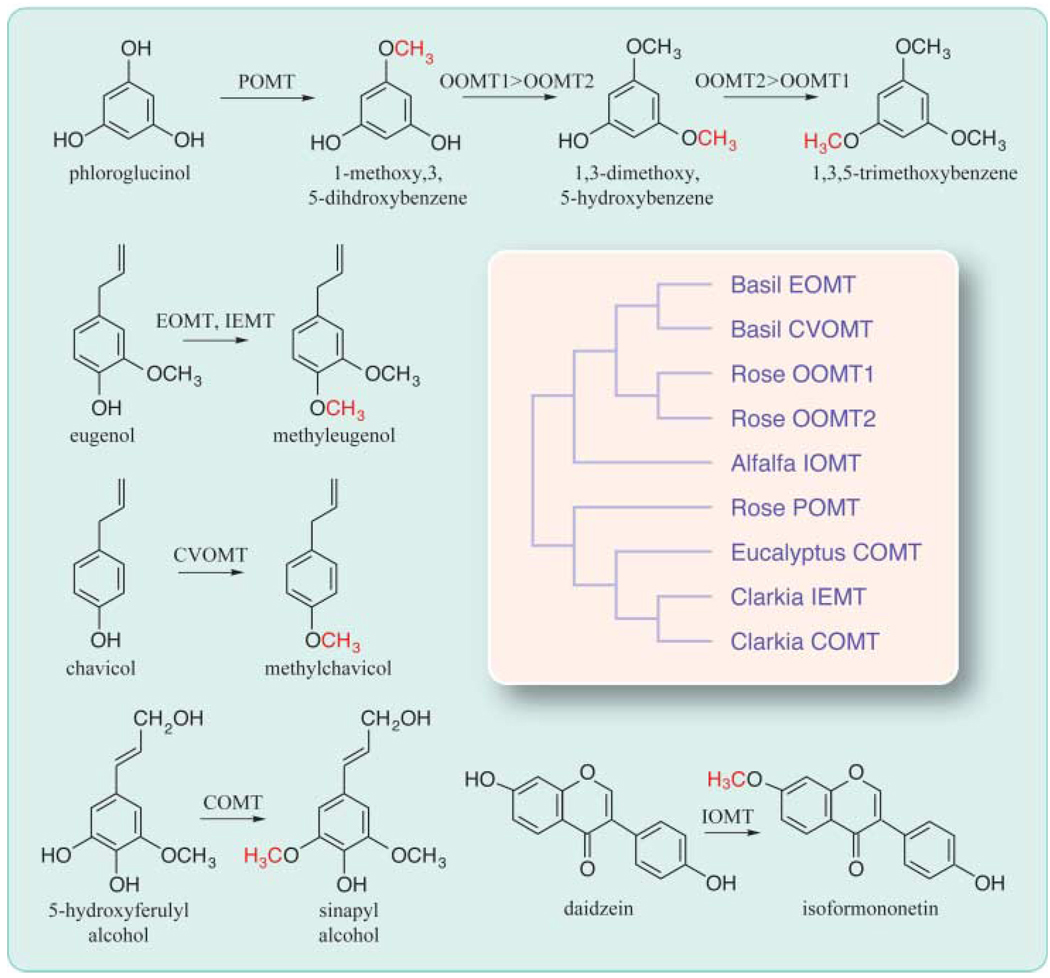

In these protein families, little correlation is observed between the level of sequence similarity among enzymes and the structural similarity of their substrates. An illustrative example involves a group of O-methyltransferases that catalyze the formation of scent compounds in rose, basil, and C. breweri (Fig. 2). In rose flowers, 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene is produced from phloroglucinol (1,3,5-trihydroxybenzene) through three successive methylations. An enzyme designated phloroglucinol O-methyltransferase (POMT) monomethylates phloroglucinol but lacks iterative activity with subsequent methylated intermediates (31). The second and third reactions are catalyzed by two highly similar proteins (96% amino acid sequence identity), OOMT1 (orcinol O-methyltransferase 1) and OOMT2 (32). OOMT1 slightly prefers the first intermediate (1-methoxy-3,5-dihydroxybenzene) and OOMT2 prefers the second intermediate (1,3-dimethoxy-5-hydroxybenzene). The high degree of sequence identity between OOMT1 and OOMT2 indicates recent gene duplication and incipient gene evolution. However, neither of these two enzymes methylates phloroglucinol. POMT is highly divergent from OOMT1 and OOMT2 (30% identity), having higher sequence similarity (54% identity) to IEMT (isoeugenol/eugenol methyltransferase), the enzyme that methylates eugenol (and isoeugenol) in C. breweri. Moreover, POMT and IEMT have higher sequence identity (>60%) with COMT (caffeic acid O-methyltransferase), a methyltransferase involved in lignin biosynthesis (31, 33). On the other hand, OOMT1 and OOMT2 are more similar (50% identical) to EOMT (eugenol O-methyltransferase), the basil enzyme that methylates eugenol, as well as to enzymes involved in isoflavone biosynthesis (34).

Fig. 2.

Structural relatedness of some methyltransferases and their substrates. POMT, OOMT1, and OOMT2 are involved in synthesizing the rose floral volatile 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene. Basil EOMT and C. breweri IEMT methylate eugenol to produce methyleugenol. Basil CVOMT methylates chavicol to produce methylchavicol. Eugenol, chavicol, methylchavicol, and methyleugenol are all volatiles with distinct aromas. COMT is an enzyme in the lignin biosynthetic pathway, and IOMT methylates the nonvolatile isoflavone daidzein to the nonvolatile isoformonentin. All these enzymes use S-adenosyl-l-methionine as the methyl donor [adapted from (31–34)]. The branches in the schematic phylogenetic tree are not drawn to scale.

In vitro mutagenesis experiments with these and similar enzymes show that changes in a few critical residues can create PV biosynthetic enzymes with altered substrate specificity (33, 34). For example, a single active-site substitution in basil chavicol O-methyltransferase (CVOMT) (Fig. 2) creates an enzyme whose substrate specificity is identical to that of basil EOMT (34). The presence of gene families enhances the chances for duplications to occur and also increases the chances of repeated evolution, a special case of convergent evolution in which enzymes with similar functions evolve independently in different species from homologous but not necessarily orthologous genes (such as eugenol methyltransferases in basil and C. breweri)(4). On the other hand, because a new volatile may confer higher fitness than an existing volatile, gene duplication is not an absolute prerequisite for divergence, and orthologous genes in different species may encode enzymes for different PVs (35).

Spatial and Temporal Modulation of PV Biosynthesis

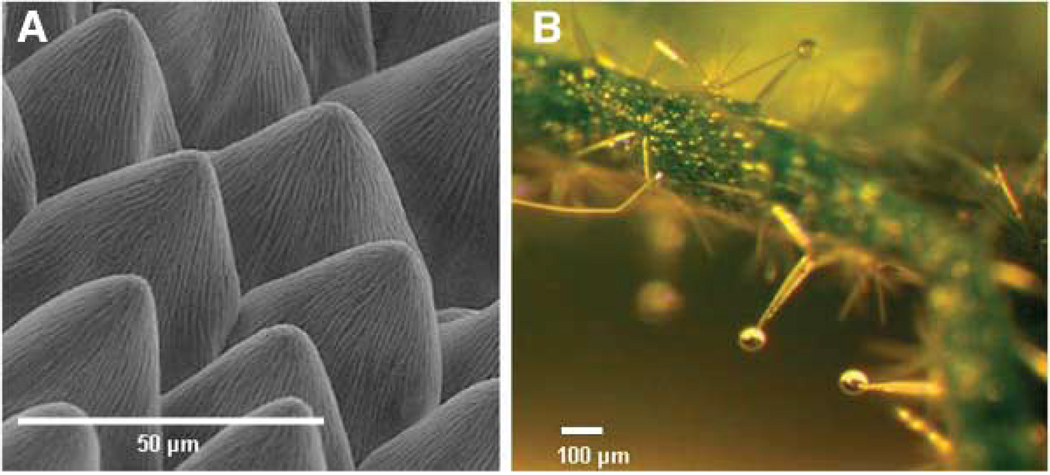

In flowers, the biosynthesis of PVs usually occurs in epidermal cells (Fig. 3A), allowing an easy escape of PVs into the atmosphere (36). In vegetative organs, PVs may be synthesized in surface glandular trichomes (Fig. 3B) and then secreted from the cells and stored in a sac created by the extension of the cuticle (13, 37). Some PVs are made in internal structures such as individual specialized cells (38) or ducts (39) from which they can be released upon disruption (for example, by herbivory). Free PVs in cells probably accumulate in membranes, but in some cases volatiles are glycosylated and apparently stored in vacuoles (40). The postsynthesis subcellular localization of PVs is, unfortunately, a much neglected area.

Fig. 3.

Localization of storage and synthesis of PVs. (A) Conical cells on the surface of snapdragon petals synthesize and emit terpenes and benzenoids. (B) Glands of Cistus creticus, a shrub native to Crete, are rich in volatile and nonvolatile terpenes.

The rates of biosynthesis of leaf PVs are typically highest when leaves are young and not fully expanded and need the most protection, which PVs provide directly because of their toxicity or indirectly through the summoning of herbivores’ predators (1, 2, 41). High rates are also observed when flowers are ready for pollination, and they decrease drastically after fertilization (2, 23). Biosynthetic rates are correlated with levels of transcripts of genes encoding the final biosynthetic enzymes, or the concentration of the substrates of these enzymes, or both (2, 42).

PV synthesis or emission may be influenced by environmental factors such as light, temperature, and moisture (41, 43) and often follow a rhythmic pattern, which may be regulated by a circadian clock or light (2, 44).

Conclusion

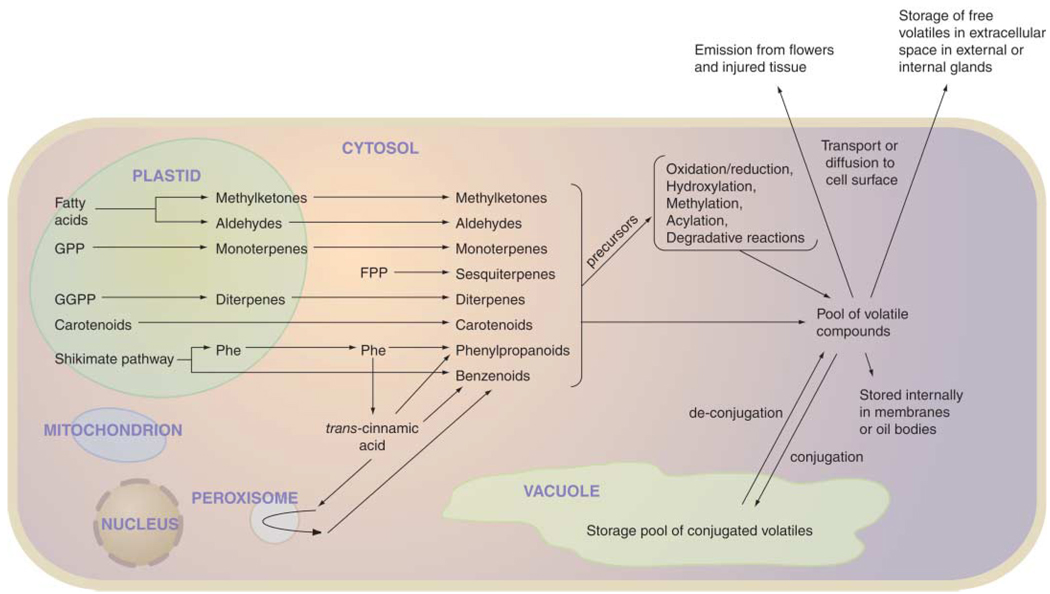

Each plant species is capable of synthesizing a unique set of volatiles. In the past decade, a large number of pathways and enzymes for the synthesis of PVs have been discovered (Fig. 4). We have learned that PVs are often derived from primary metabolism through the emergence of one or a few enzymes with new substrate specificities, mostly through duplication and divergence of enzymes used elsewhere in primary or secondary metabolism. Despite this progress, the enzymes responsible for the majority of already known PVs have not been characterized, and no doubt the number of PVs and their biosynthetic enzymes yet to be identified exceeds the known ones many times. Much remains to be elucidated regarding the internal and external factors influencing PV biosynthesis. Finally, the transport, storage, and emission of these compounds are neglected areas of study that must be addressed to complete our understanding of how plants use these specialized metabolites in diverse ecosystems.

Fig. 4.

Summary of the cellular processes involved in the synthesis of PVs. Most modification reactions occur in the cytosol, but some may take place in other subcellular compartments, including plastids, mitochondria, peroxisomes, and the endoplasmic reticulum.

References and Notes

- 1.Pichersky E, Gershenzon J. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2002;5:237. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(02)00251-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dudareva N, Pichersky E, Gershenzon J. Plant Physiol. 2004;135:1893. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.049981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodwin SM, et al. Physiol. Plant. 2003;117:435. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3054.2003.00047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pichersky E, Gang D. Trends Plant Sci. 2000;5:439. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(00)01741-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goff SA, Klee HJ. Science. 2006;311:XXXX. doi: 10.1126/science.1112614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knudsen JT, Tollsten L, Bergstrom G. Phytochemistry. 1993;33:253. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwab W. Phytochemistry. 2003;62:837. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(02)00723-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buchanan BB, Gruissem W, Jones RL, editors. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology of Plants. Rockville, MD: American Society of Plant Biology; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bohlmann J, Meyer-Gauen G, Croteau R. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998;95:4126. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Starks CM, Back K, Chappell J, Noel JP. Science. 1997;277:1815. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5333.1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tholl D, Chen F, Petri J, Gershenzon J, Pichersky E. Plant J. 2005;42:757. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kollner TG, Schnee C, Gershenzon J, Degenhardt J. Plant Cell. 2004;16:1115. doi: 10.1105/tpc.019877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gang DR, et al. Plant Physiol. 2001;125:539. doi: 10.1104/pp.125.2.539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tadmor Y, et al. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002;50:2005. doi: 10.1021/jf011237x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayashi S, et al. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:7005. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boatright J, et al. Plant Physiol. 2004;135:1993. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.045468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borejsza-Wysooki W, Hrazdina G. Plant Physiol. 1996;110:791. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.3.791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Howe GA, Schilmiller AL. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2002;5:230. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(02)00250-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fridman E, et al. Plant Cell. 2005;17:1252. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.029736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.D’Auria JC, Chen F, Pichersky E. Plant Physiol. 2002;130:466. doi: 10.1104/pp.006460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simkin AJ, Schwartz SH, Auldridge M, Taylor MG, Klee HJ. Plant J. 2004;40:882. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frey M, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000;97:14801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.260499897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Negre F, et al. Plant Cell. 2003;15:2992. doi: 10.1105/tpc.016766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pott M, et al. Plant Physiol. 2004;135:1946. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.041806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seo HS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:4788. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081557298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shalit M, et al. Plant Physiol. 2003;131:1868. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.018572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bouwmeester HJ, Gershenzon J, Konings MCJM, Croteau R. Plant Physiol. 1998;117:901. doi: 10.1104/pp.117.3.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bate NJ, Riley JCM, Thompson JE, Rothstein SJ. Physiol. Plant. 1998;104:97. doi: 10.1104/pp.117.4.1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schuler MA, Werck-Reichart D. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2003;54:629. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.54.031902.134840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bouwmeester HJ, Konings MCJM, Gershenzon J, Karp F, Croteau R. Phytochemistry. 1999;50:243. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu S, et al. Plant Physiol. 2004;135:95. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.037051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lavid N, et al. Plant Physiol. 2002;129:1899. doi: 10.1104/pp.005330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang J, Pichersky E. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1999;368:172. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gang DR, et al. Plant Cell. 2002;14:505. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van der Hoeven RS, Monforte AJ, Breeden D, Tanksley SD, Steffens JC. Plant Cell. 2000;12:2283. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.11.2283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kolosova N, Sherman D, Karlson D, Dudareva N. Plant Physiol. 2001;126:956. doi: 10.1104/pp.126.3.956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Turner GW, Gershenzon J, Croteau RB. Plant Physiol. 2000;124:655. doi: 10.1104/pp.124.2.655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lewinsohn E, et al. Ann. Bot. (London) 1998;81:35. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Franceschi VR, Krokene P, Christiansen E, Kreklling T. New Phytol. 2005;167:353. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Watanabe S, et al. Biosci. Biotech. Biochem. 2001;65:442. doi: 10.1271/bbb.65.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gershenzon J, McConkey ME, Croteau RB. Plant Physiol. 2000;122:205. doi: 10.1104/pp.122.1.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Verdonk JC, Haring MA, van Tunen AJ, Shuurink RC. Plant Cell. 2005;17:1612. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.028837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Staudt M, Bertin N. Plant Cell Environ. 1998;21:385. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Helsper JPFG, Davies JA, Bouwmeester HJ, Krol AF, van Kampen MH. Planta. 1998;207:88. [Google Scholar]

- 45.We thank N. Kolosova and M. Varbanova for help with Fig. 3. We apologize to our colleagues whose work could not be cited for lack of space. J.P.N. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. Funded by grants from NSF (E.P, J.P.N, and N.D.), the U.S. Department of Agriculture (E.P. and N.D.), and the National Institutes of Health (J.P.N.).