Abstract

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) reverse transcriptase (RT) contains four structural motifs (A, B, C, and D) that are conserved in polymerases from diverse organisms. Motif B interacts with the incoming nucleotide, the template strand, and key active-site residues from other motifs, suggesting that motif B is an important determinant of substrate specificity. To examine the functional role of this region, we performed “random scanning mutagenesis” of 11 motif B residues and screened replication-competent mutants for altered substrate analog sensitivity in culture. Single amino acid replacements throughout the targeted region conferred resistance to lamivudine and/or hypersusceptibility to zidovudine (AZT). Substitutions at residue Q151 increased the sensitivity of HIV-1 to multiple nucleoside analogs, and a subset of these Q151 variants was also hypersusceptible to the pyrophosphate analog phosphonoformic acid (PFA). Other AZT-hypersusceptible mutants were resistant to PFA and are therefore phenotypically similar to PFA-resistant variants selected in vitro and in infected patients. Collectively, these data show that specific amino acid replacements in motif B confer broad-spectrum hypersusceptibility to substrate analog inhibitors. Our results suggest that motif B influences RT-deoxynucleoside triphosphate interactions at multiple steps in the catalytic cycle of polymerization.

Conversion of viral RNA to double-stranded DNA by reverse transcriptase (RT) is a defining step in the retroviral life cycle (8) and a key target of therapy for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection (17). The 66-kilodalton subunit of HIV-1 RT contains four motifs (A, B, C, and D) that are similarly arranged in all known structures of replicative DNA and RNA polymerases (21). Three additional structural elements, motifs E and F and premotif A, are also conserved among RTs and viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerases (4, 21, 45, 76). Together, motifs A, B, C, and F and premotif A form a closely packed protein framework that positions the templating nucleotide, the primer terminus, and incoming deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP) at the RT active site (Fig. 1A). Amino acid substitutions within this conserved core can affect dNTP insertion fidelity, susceptibility to nucleoside analogs, and/or discrimination against ribonucleoside triphosphates (rNTPs) during DNA synthesis (40, 49, 64, 72). Thus, these motifs influence the stringency and specificity of substrate incorporation by RT.

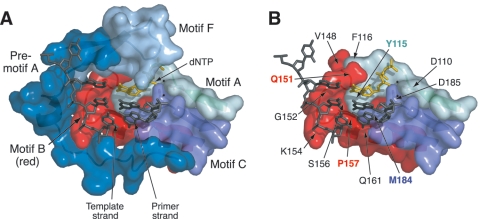

FIG. 1.

Relationship of motif B to other structural components in the ternary complex of HIV-1 RT (Protein Data Bank entry 1RTD) (24). (A) Surface representation of conserved structural motifs in the polymerase domain. Amino acids 107 to 118 (motif A), 147 to 169 (motif B), and 180 to 189 (motif C) are shown, as assigned by Poch et al. (53). Residues 102 to 106 (motif A), 143 to 146 (motif B), and 190 (motif C) are omitted for clarity. Boundaries for motif F (residues 64 to 75) are based on recent alignments of viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerases (4, 76). The region designated “premotif A” (residues 75 to 91) was originally identified in an alignment of HIV-1 RT with negative-stranded RNA virus polymerases (45). (B) Location of several motif B amino acids and other residues discussed in the text. Motif F and premotif A have been removed for clarity. Amino acid substitutions at residues Q151 and P157 (labeled in red) are known to confer resistance to nucleoside analogs (25, 36, 61). Residues Y115 and M184 are key determinants of dNTP substrate selectivity in motifs A and C, respectively (40, 64). Mg2+ ions coordinated at the active site are shown as small black spheres. These views were produced using MacPyMOL version 0.95 (http://pymol.sourceforge.org).

Motif B is of particular interest because of its central position in the RT core structure (Fig. 1) (12, 24). Motif B contacts the template strand, the incoming dNTP, and each of the other motifs in the core structure (premotif A and motifs A, C, and F) (Fig. 1A), including residues within these other motifs that are known to affect dNTP substrate recognition (Fig. 1B) (12, 24). The importance of motif B in substrate selection is evident from studies of HIV-1 mutants resistant to nucleoside analogs (49, 72). Two amino acid substitutions in motif B are associated with resistance to chain-terminating inhibitors: Q151M and P157S (Fig. 1B). The Q151M replacement confers low-level resistance to 3′-azido-3′-deoxythymidine (zidovudine [AZT]), 2′,3′-dideoxyinosine (didanosine [ddI]), and 2′,3′-didehydro-3′-deoxythymidine (stavudine [d4T]) (25, 36). The addition of mutations at RT positions 62, 75, 77, and 116 in combination with Q151M substantially increases the level of resistance to these drugs both in vitro and in patients receiving antiviral therapy (25, 36). The P157S mutation, originally observed in a drug-resistant isolate of feline immunodeficiency virus, confers resistance to (−)-β-2′,3′-dideoxy-3′-thiacytidine (lamivudine [3TC]) in both feline immunodeficiency virus and HIV-1 (61, 62). Mutation P157S or P157A is occasionally observed in RT sequences from patients receiving nucleoside analog therapy (15, 43, 46, 52).

Additional evidence for the role of motif B in substrate selectivity comes from biochemical studies of HIV-1 RT mutants. Specific substitutions at position Q151 affect nucleotide insertion fidelity, discrimination against rNTPs, and the incorporation of nucleotide analogs (10, 23, 28, 33, 54, 74). Replacements at motif B residues V148, W153, K154, P157, and F160 also affect fidelity and/or analog incorporation in cell-free polymerase assays (11, 18, 29, 33, 56, 57, 74). However, most of the RT mutants examined in these experiments exhibit significant reductions in catalytic activity and are therefore unlikely to support HIV-1 replication (13, 48). Thus, the importance of motif B for substrate analog susceptibility and accurate DNA synthesis during viral replication remains largely unexplored.

To this end, we used “random scanning mutagenesis” to construct pools of HIV-1 variants, and we subjected these pools to a single passage in culture to identify motif B mutations that preserve viral replication capacity. Individual variants were then screened for altered sensitivity to nucleoside and pyrophosphate analogs. Our results show that many motif B residues influence substrate analog susceptibility and that specific substitutions in this region confer hypersusceptibility to structurally diverse nucleoside analog inhibitors. The phenotypes exhibited by these mutants suggest that motif B influences both the substrate selectivity and the primer unblocking activity of HIV-1 RT.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Inhibitors.

RT inhibitors ddI, d4T, and phosphonoformic acid (foscarnet [PFA]) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, Mo. Inhibitors (R)-9-(2-phosphonylmethoxypropyl)adenine (tenofovir [PMPA]) and (1S,4R)-4-[2-amino-6-(cyclopropyl-amino)-9H-purin-9-yl]-2-cyclopentene-1-methanol (abacavir [ABC]) were obtained from Moravek Biochemicals Inc., Brea, Calif. AZT was purchased from Moravek and Sigma-Aldrich. 3TC was kindly provided by Raymond Schinazi of Emory University or purchased from Moravek.

Plasmids, cells, and virus.

All mutant strains and random virus pools were derived from a modified version of the full-length pR9 HIV-1 clone (65) that lacks an ApaI site in the plasmid backbone (kindly provided by Uta von Schwedler, University of Utah). pBSpol was created by subcloning an ApaI/EcoRI fragment of pR9 (HIV-1NL4-3, nucleotides 2010 to 5743) into pBluescript II KS(−) (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.). pBSpolam (containing an amber stop codon substitution at RT position 154) and pBSpolClaI (containing the insertion GATCGAT at RT codon 152 [ClaI site underlined]) were generated from pBSpol by site-directed mutagenesis (Muta-Gene phagemid mutagenesis kit; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.). pR9Δpol was created from pR9 by replacing the ApaI/EcoRI fragment with an ApaI-ATCGATGCGGCCGC-EcoRI synthetic linker (unique ClaI and NotI sites are underlined and italicized, respectively).

293tsA1609neo (293T) (51) and HeLa-CD4-LTR-β-galactosidase (HeLa-P4) (5) cells were cultured (37°C, 5% CO2) in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, Calif.) supplemented with 4 mM l-glutamine, 50 U/ml penicillin, 50 μg/ml streptomycin, and 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone, Logan, Utah).

Random-scanning mutagenesis.

Mutant plasmid libraries containing random substitutions at individual codons in RT motif B were constructed by oligonucleotide-mediated mutagenesis using pBSpolam (for G152, K154, P157, and Q161 mutant pools) or pBSpolClaI (for the remaining mutant pools) as template DNA. The oligonucleotides used to generate single-codon random mutants (Operon, Alameda, Calif.) spanned HIV-1NL4-3 nucleotides 2971 to 3030 for pools randomized at sites V148 to Q151, nucleotides 2982 to 3029 for G152, nucleotides 2977 to 3034 for W153 and G155, nucleotides 2991 to 3030 for K154, nucleotides 2982 to 3038 for S156, and nucleotides 3002 to 3043 for P157 and Q161. Nucleotide sequences at each randomized site were as follows: V148, HNN/NVN; L149, NVN/RNN; P150, NDN/DNN; Q151, NBN/DNN; G152, HNN/HHN/NHN; W153, NNH; K154, BNN/BNY/NNY; G155, HNN/NHN; S156, NWN/SNN/VNR; P157, NDN/DNN; and Q161, NBN/DNN (where N is A/T/G/C, D is A/G/T, B is C/G/T, H is A/C/T, V is A/C/G, R is A/G, Y is C/T, and S is C/G). These resulted in the exclusion of wild-type amino acids at each target codon and also excluded variants L149F, Q151H, K154M, S156C, S156W, and Q161H from their respective random pools. Products from the mutagenesis reactions were electroporated into ElectroMAX DH10B Escherichia coli (Gibco BRL), plasmids were isolated from pools of >104 independent transformants, and ApaI/EcoRI fragments from the pools were cloned into pR9Δpol. The resulting full-length pR9 mutant libraries were purified from pools of >104 independent transformants using the Endo-Free maxiprep kit (QIAGEN Inc., Valencia, Calif.).

Transfections.

To prepare wild-type virus stocks and random virus pools, CaPO4-pR9 DNA coprecipitates were prepared with 10 μg plasmid DNA as described previously (6), except that the 2× BBS buffer was replaced with 2× HEPES-buffered saline (270 mM NaCl, 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM Na2HPO4 · 2H2O, 11 mM dextrose, 40 mM HEPES, pH 7.05). 293T cultures were seeded into 10-cm plates and grown to approximately 25% confluence prior to the addition of CaPO4-DNA coprecipitates. Following a 3-hour incubation, culture supernatants were aspirated, 2 ml of 10% glycerol in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was added to each plate, and the cells were incubated at 37°C for 2 min. Cells were then rinsed twice with 6 ml of PBS, 10 ml of DMEM was added to each plate, and the cultures were returned to the incubator. Culture supernatants were harvested at approximately 42 h after transfection, filtered through 0.4-μm syringe filters, and stored in 1-ml aliquots in the vapor phase of liquid nitrogen for subsequent analysis. Stocks of individual HIV-1 mutants were produced by transfection of 293T cells as described above, except that the glycerol shock step was omitted. Cultures were instead treated with chloroquine at a final concentration of 25 μM in DMEM immediately before the DNA-CaPO4 mixtures were added. Supernatants were aspirated and replaced with fresh medium 1 day later and then harvested and frozen on the following day as described above. The titers of wild-type stocks produced by either protocol typically ranged from 2 × 105 to 5 × 105 focus forming units (FFU)/ml for frozen stocks and 1 × 106 to 4 × 106 FFU/ml for fresh preparations.

HeLa-P4 passage protocol.

HeLa-P4 cells were seeded at 105 cells per 10-cm plate and infected the next day with 104 FFU in 2 ml DMEM containing 20 μg/ml DEAE-dextran (Sigma). After incubation at 37°C for 2 to 4 h, an additional 6 ml of DMEM was added to each plate, and incubation was continued overnight. The monolayers were then washed three times with 6 ml of PBS, and the cultures were replenished with 8 ml fresh medium, which was changed again after 2 days of incubation. Culture supernatants were harvested on the fifth day after infection, passed through 0.4-μm filters, and treated with 420 U DNase I (Worthington Biochemical) at 37°C for 20 min after we added MgCl2 to a final concentration of 10 mM. Viral particles were concentrated by layering 1 ml of culture supernatant onto a 250-μl cushion of 20% sucrose in phosphate-buffered saline, followed by centrifugation at 15,500 × g for 90 min at 4°C. Virion pellets were resuspended in 100 μl of lysis buffer (7 M urea, 0.35 M NaCl, 4 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate) and stored at −20°C for subsequent RNA extraction and RT-PCR amplification. The remaining unconcentrated culture supernatants were frozen in 1-ml aliquots in the vapor phase of liquid nitrogen.

RT-PCR and DNA sequencing.

RT-PCR was performed in thin-walled tubes (Robbins), using the Access RT-PCR system (Promega), in 50-μl reaction mixtures containing 200 μM of each dNTP, 1 mM MgSO4, 5 U avian myeloblastosis virus RT, 5 U Tfl DNA polymerase, 10 μl of 5× avian myeloblastosis virus-Tfl buffer, 50 pmol each of primers H3 and BH1 (see below), and 1 μl of extracted viral RNA. Primers BH1 (5′-TATGGATCCCTTTTAGAATCTCCCTGTTTTCTGCC-3′; BamHI site underlined) and H3 (5′-AGTCAAGCTTGGATGGCCCAAAAGTTAAACAATGGCC-3′; HindIII site underlined) amplified a 0.8-kb fragment corresponding to nucleotides 2597 to 3483 of HIV-1NL4-3. Thermocycling conditions in an MJ Research PTC-100 thermocycler were as follows: 48°C for 45 min, 94°C for 2 min, then 40 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 60°C for 1 min, and 68°C for 2 min, and ending with 68°C for 7 min. Control reactions lacking RT were performed and analyzed in parallel to ensure that amplification was RNA dependent. When required, viral RNA samples were subjected to a second DNase I treatment to remove contaminating plasmid or proviral DNA (see above). RT-PCR products were digested with BamHI and HindIII, ligated into double-digested pBluescript II KS(−), transformed into E. coli, and spread on agar plates containing ampicillin. Individual colonies were randomly picked from these plates, and plasmids were isolated and sequenced using primer pNL1 (5′-GACTTCAGGAAGTATACTGC-3′) and BigDye Terminator chemistry (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.).

Infectivity assay.

Single-round infectivities were determined using HeLa-P4 indicator cells as previously described (5, 61). Briefly, HeLa-P4 cells were seeded into 96-well plates at 0.5 × 104 cells/well and infected the following day with serial dilutions of virus prepared in DMEM containing 20 μg/ml DEAE-dextran. After 40 h of growth, cultures were fixed and stained with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal; Promega, Madison, Wis.). In this time frame, infected cells appeared as isolated groups of two to five contiguous Lac+ (blue) cells, indicating that the majority of foci were derived from a single cycle of virus replication. Titers of Lac+ foci were normalized against HIV-1 capsid p24 concentration (HIV-1 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; PerkinElmer, Boston, MA) to determine the infectivities of mutants relative to that of the wild-type virus. The infectivity of the wild-type pR9-derived HIV-1NL4-3 was 880 ± 180 FFU/ng p24 (mean ± standard error) for frozen stocks and 4,500 ± 1,100 FFU/ng p24 for fresh supernatants. A variant containing the RT-inactivating D185A mutation served as a negative control and yielded 0.014 ± 0.004 FFU/ng p24 from frozen stocks.

Inhibitor sensitivity assay.

For measurements of inhibitor sensitivity, HeLa-P4 cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 0.5 × 104 cells/well and incubated overnight. Culture wells were dosed with various concentrations of inhibitor on the following morning, and the plates were then returned to the incubator for an additional 3 hours. Immediately prior to infection, virus stocks were diluted to 4,000 FFU/ml in DMEM containing 20 μg/ml of DEAE-dextran. Supernatants in the microtiter plates were aspirated, and 25 μl of the virus dilution was added directly to the monolayer in each well. Plates were then returned to the incubator for 3 hours. After this time, an additional 175 μl medium was added to each well, a second dose of inhibitor was added (at the same concentration as the first dose), and incubation was continued for two more days. Culture monolayers were fixed and stained as described above, and Lac+ foci were counted. Control cultures incubated in the absence of substrate analogs typically yielded 70 to 250 foci/well. Concentrations of analog required to inhibit focus formation by 50% of the untreated control value (50% effective concentration [EC50]) were calculated by linear regression of the resulting dose-response data.

RESULTS

Random scanning mutagenesis of motif B.

To examine the role of motif B in substrate analog sensitivity, we first generated pools of HIV-1 mutants containing random single amino acid replacements at each of 11 motif B residues (60). This strategy is an extension of alanine scanning mutagenesis (9) and is referred to here as “random scanning mutagenesis.” The benefit of random scanning mutagenesis is that all 19 amino acid substitutions are introduced at each position, thus permitting the detection of functional changes that are not produced by simple alanine substitutions.

We used two different strategies to optimize the yield of random amino acid substitutions and minimize the proportion of wild-type sequences at each target codon. In the first approach, we constructed a pol subclone that contained a lethal amber stop codon at RT position K154 (pBSpolam). Mutagenic oligonucleotides were used to correct this stop codon and simultaneously introduce random substitutions at RT codon G152, K154, P157, or Q161. Following mutagenesis, the pol genes were ligated into a pol-deleted HIV-1 construct (pR9Δpol) to produce full-length HIV-1 plasmid libraries, each randomized at a specific codon in RT motif B. Sequence analyses of 180 individual pR9 clones generated by this method confirmed that each library contained a diverse array of amino acid substitutions at the targeted motif B position. Pools randomized at codon G152, K154, P157, or Q161 contained 12, 16, 17, or 14 of 20 possible amino acid residues, respectively, at the target codon. However, each pool also contained a substantial number of nonmutant clones that retained the K154 amber stop codon (50% in the K154, P157, and Q161 pools and 85% in the G152 pool). Although these K154 amber products did not interfere with subsequent experimental steps, sequencing of large numbers of clones was required in order to characterize the diversity of each library.

To increase mutagenesis efficiency, we devised a second strategy for random mutagenesis of the remaining seven target residues in motif B. This method started with a pol subclone containing a unique ClaI restriction site at position 152 of RT (pBSpolClaI). Oligonucleotide primers restored the wild-type sequence at codon 152 while simultaneously introducing random mutations at position 148, 149, 150, 151, 153, 155, or 156 of RT. After subcloning into pR9Δpol and amplification in E. coli, the resulting full-length HIV-1 plasmid libraries were enriched for mutant clones by being digested with ClaI, followed by a third round of E. coli amplification. Sequencing of individual clones generated by this second strategy showed that the final proportion of mutant plasmids in the resulting libraries was >90% and that the diversity of these libraries was similar to the diversity achieved using the initial pBSpolam-based approach (see above). Both mutagenesis strategies limited but did not completely exclude wild-type clones, which were present at frequencies of 5 to 12% in the plasmid libraries.

Selection of replication-competent mutants.

The full-length mutant HIV-1 plasmid libraries were separately transfected into 293T cells to produce mutant virus pools, each comprised of variants with random replacements at a single codon in motif B. Replication-competent viruses were selected from these pools by subjecting the virus populations to a single 5-day passage in HeLa-P4 cells (see Materials and Methods for details). Infectious mutants were then identified by sequencing individual clones of RT-PCR products derived from the resultant HeLa-P4-passaged pools. Altogether, 52 different single amino acid substitutions in motif B were detected following a single passage in culture (Table 1). Eight of the 11 pools (V148, L149, P150, Q151, K154, G155, P157, and Q161) yielded mutants with both conservative and nonconservative replacements at the respective target codons. Two pools (W153 and S156) yielded only a single variant, and only one pool (G152) failed to produce infectious mutants.

TABLE 1.

Amino acid substitutions observed in the mutant virus pools following a single passage in HeLa-P4 cells

| Positiona | Amino acid(s) (no. of clones)b |

|---|---|

| V148 | V (18), I (1), S (2), C (3), T (1), R (1) |

| L149 | L (18), I (6), T (1), M (2) |

| P150 | P (24), A (2), K (1) |

| Q151 | G (7), A (12), V (1), I (1), S (1), C (1), T (3), M (4) |

| G152 | G (19) |

| W153 | W (25), F (1) |

| K154 | G (10), A (2), V (7), L (5), S (6), C (4), T (9), R (1), N (1), W (1) |

| G155 | G (11), A (4), V (1), L (1), S (1), C (1), M (2), N (3), Q (2) |

| S156 | S (20), A (25) |

| P157 | P (18), G (13), A (2), L (1), S (2), C (4), T (3) |

| Q161 | Q (8), G (8), A (4), V (3), L (2), S (3), T (1), M (3), E (4) |

Pools of mutants were produced and manipulated as independent virus populations, each containing random mutations at the specified amino acid position in RT.

RT-PCR products amplified from HeLa-P4 supernatants were cloned into a plasmid vector and sequenced. Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of clones containing wild-type (bold italics) or mutant (roman) amino acids at the targeted RT codon. No wild-type clones were observed in random mutant pool Q151 or K154. Data are retabulated from reference 60.

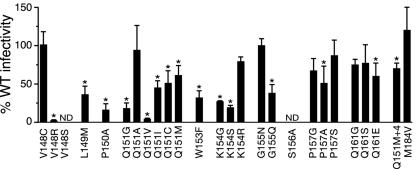

To confirm that the variants identified in the HeLa-P4-selected populations were viable, we performed two separate analyses of viral replication. First, the K154, P157, and Q161 mutant virus pools were subjected to three additional passages in culture, and the range of mutants present in these subsequent cultures was determined by sequencing 25 to 50 clones from each passage interval. Of the 25 mutants identified in the first passage of these mutant pools (Table 1), 23 were detected in passage 2, 3, or 4 (60). Thus, the majority of mutants observed after a single passage in culture were capable of multiple cycles of replication. We also constructed 24 full-length HIV-1 plasmid clones containing specific single amino acid substitutions in motif B that were detected in the passage 1 supernatants. In most cases, the variants produced by these clones retained ≥50% of wild-type infectivity (Fig. 2). Altogether, 47 of the 52 mutants observed in the virus pools following a single passage in HeLa-P4 cells (Table 1) were replication competent, as evidenced by their infectivity as purified clones (Fig. 2) and/or persistence in subsequent passages (60).

FIG. 2.

Replication capacities of RT motif B mutants. 293T cells were transfected with the wild-type (WT) HIV-1 pR9 clone or with clones containing specific substitutions in motif B. Titers in the resulting cultures were measured using HeLa-P4 cells and normalized to the concentration of HIV-1 capsid p24 in the supernatant to determine the infectivity of each mutant relative to that of the wild-type virus. ND, not determined; Q151M+4, multinucleoside-resistant mutant Q151M/A62V/V75I/F77L/F116Y (25). *, statistically different from the wild type by one-way analysis of variance (P < 0.05).

Residues throughout motif B affect nucleoside analog sensitivity.

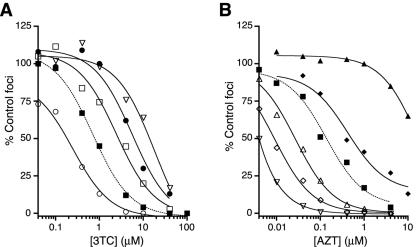

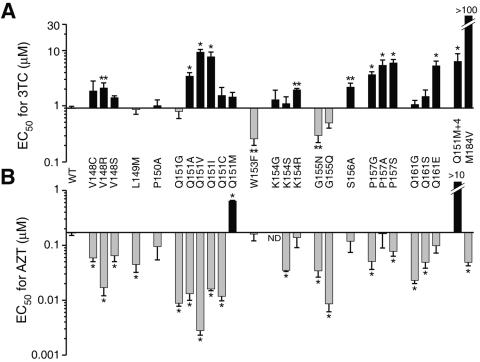

To assess the functional importance of motif B, we initially measured the susceptibility of each replication-competent mutant shown in Fig. 2 to the cytidine nucleoside analog 3TC. Several mutations in motif B altered the sensitivity of the virus to this analog (Fig. 3A and 4A). Overall, there was a trend towards 3TC resistance among the variants analyzed (Fig. 4A), although many substitutions were neutral and three replacements (W153F, G155N, and G155Q) resulted in slight hypersusceptibility to 3TC.

FIG. 3.

Representative dose-response data for the pyrimidine analogs 3TC (A) and AZT (B). Profiles for wild-type HIV-1 (dotted lines) and several motif B variants (solid lines) are shown. Analog sensitivities were measured by quantitating the dose-dependent reduction of Lac+ foci in HeLa-P4 cells. The percentages of solvent-only control foci are plotted as a function of nucleoside analog concentration. Curves were generated using a sigmoidal regression equation (GraphPad Prism 4 software package [44]). The results for each strain are from a single assay, with two determinations of focus formation per drug concentration. These data are representative of the responses observed for each mutant in multiple independent experiments. •, P157S; ○, W153F; ▪, wild type; □, Q151A; ▿, Q151V; ▴, Q151M/A62V/V75I/F77L/F116Y; ▵, Q161G; ♦, Q151M; ⋄, G155Q.

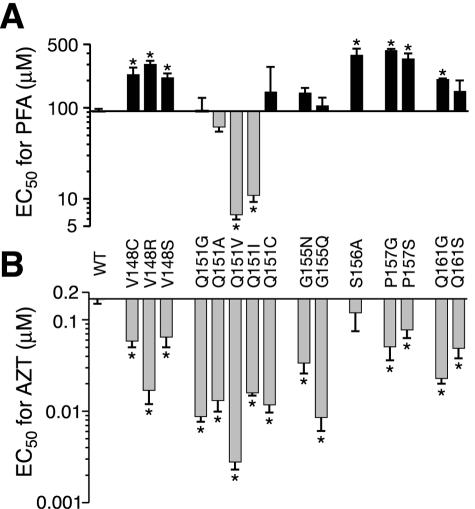

FIG. 4.

Susceptibilities of motif B mutants to 3TC (A) and AZT (B). Concentrations of nucleoside analog required to inhibit Lac+ focus formation in HeLa-P4 cells by 50% (EC50) were calculated by regression analyses of dose-response data (Fig. 3), as described in Materials and Methods. The abscissa is set at the EC50 for wild-type (WT) virus; bars above and below the abscissa represent analog resistance and hypersusceptibility, respectively. Each bar represents the mean ± standard error from at least three independent experiments. *, significantly different from the wild type by one-way analysis of variance (P < 0.05); **, significantly different from the wild type by a paired t test (P < 0.05). ND, not determined. Variants Q151M+4 (Q151M/A62V/V75I/F77L/F116Y) and M184V, which exhibit high-level resistance to AZT and 3TC, respectively, served as positive controls in these assays (25, 55, 69).

We also examined the susceptibility of each motif B mutant to the thymidine analog AZT. As previously reported, the Q151M mutation conferred moderate resistance to AZT, and the Q151M/A62V/V75I/F77L/F116Y complex of mutations conferred >50-fold resistance to the drug (25, 36). In contrast, most of the other motif B mutants examined were hypersusceptible to AZT (Fig. 3B and 4B). Specific substitutions at positions V148, Q151, and G155 conferred 10- to 60-fold increases in AZT sensitivity. Altogether, 20 of the 24 motif B variants examined were hypersusceptible to AZT and/or resistant to 3TC (Fig. 4). Specific mutations at codons V148, Q151, and P157 conferred both AZT hypersusceptibility and 3TC resistance.

We noted that a subset of AZT-hypersusceptible mutants exhibited a substantial impairment in viral replication capacity (Fig. 2). To further examine the relationship between hypersusceptibility and viral infectivity, we characterized the effects of four specific mutations in the “primer grip” region of RT (26). An F227A RT mutant was eightfold hypersensitive to AZT and retained 27% of wild-type HIV-1 infectivity, demonstrating that mutations outside of motif B can also confer AZT hypersusceptibility. In contrast, variants W266F, W266Y, and W266R exhibited 0.5, 27, and 92% of wild-type infectivity, respectively, but ≤2-fold changes in AZT or 3TC sensitivity. Similarly, the P150A replacement in motif B, which reduced viral infectivity to 15% of the wild type, had no effect on AZT sensitivity, while other variants that retained 80 to 100% replication capacity were ≥10-fold hypersusceptible to AZT (e.g., Q151A and Q161G) (Fig. 2 and 4B). Taken together, these data indicate that AZT hypersusceptibility does not generally correlate with reduced viral replication capacity.

Relationship between AZT hypersusceptibility and PFA resistance.

Specific replacements at codons 88, 89, 90, 92, 156, 160, 161, and 164 of HIV-1 RT have previously been shown to confer slight increases in AZT sensitivity (20, 39, 42, 67, 68). These substitutions also confer resistance to PFA, an analog that mimics the β-γ pyrophosphate group of the incoming dNTP substrate. To further examine this phenotypic relationship, we measured the sensitivities of 14 different AZT-hypersusceptible motif B mutants to PFA (Fig. 5). We also included the S156A variant in these experiments as a positive control for PFA resistance (67, 68). Six of the variants (V148C, V148R, V148S, P157G, P157S, and Q161G) were resistant to PFA (Fig. 5A) and therefore fit the aforementioned pattern of AZT hypersusceptibility and PFA resistance. As previously reported, the S156A mutation conferred fourfold resistance to PFA without significantly affecting viral sensitivity to AZT (67, 68).

FIG. 5.

Sensitivities of AZT-hypersusceptible mutants to PFA. EC50s for PFA (A) and AZT (B) were measured and graphed as described in Materials and Methods and the legend to Fig. 3. Each bar represents the mean ± standard error from at least three independent experiments. *, significantly different from the wild type (WT) by one-way analysis of variance (P < 0.05).

We also observed several variants that did not follow the AZT-hypersusceptible, PFA-resistant pattern (Fig. 5). For example, mutants Q151G, Q151C, G155N, and G155Q displayed 6- to 20-fold hypersusceptibility to AZT but were not significantly resistant to PFA. In addition, the Q151V and Q151I variants showed increased sensitivity to both AZT and PFA (Fig. 5 and Table 2). These results demonstrate that the AZT-hypersusceptible phenotype is not necessarily coupled to PFA resistance.

TABLE 2.

Susceptibilities of Q151 RT mutants to substrate analogs

| Virus | EC50 (μM)a

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3TC | AZT | d4T | ddI | PMPA | ABC | PFA | |

| Wild type | 0.90 ± 0.1 (1) | 0.17 ± 0.02 (1) | 5.8 ± 0.9 (1) | 3.1 ± 0.8 (1) | 5.9 ± 1 (1) | 7.0 ± 1 (1) | 92 ± 6 (1) |

| Q151G | 0.79 ± 0.3 (1) | 0.0088 ± 0.001 (0.1) | 0.36 ± 0.1 (0.1) | 1.2 ± 0.3 (0.4) | 0.92 ± 0.1 (0.2) | 1.3 ± 0.1 (0.2) | 93 ± 36 (1) |

| Q151A | 3.4 ± 0.5 (4) | 0.013 ± 0.003 (0.1) | 2.8 ± 2 (0.5) | 1.1 ± 0.1 (0.3) | 1.8 ± 0.2 (0.3) | 2.0 ± 0.5 (0.3) | 62 ± 8 (0.7) |

| Q151V | 9.3 ± 1 (10) | 0.0028 ± 0.001 (0.02) | 0.58 ± 0.2 (0.1) | 1.4 ± 0.1 (0.4) | 0.36 ± 0.1 (0.1) | 3.4 ± 0.5 (0.5) | 6.7 ± 0.9 (0.1) |

| Q151I | 7.7 ± 2 (9) | 0.016 ± 0.001 (0.1) | 0.55 ± 0.04 (0.1) | 0.69 ± 0.3 (0.2) | 0.48 ± 0.1 (0.1) | 3.2 ± 0.5 (0.5) | 11 ± 2.2 (0.1) |

| Q151C | 1.5 ± 0.6 (2) | 0.012 ± 0.002 (0.1) | 0.30 ± 0.05 (0.1) | 0.73 ± 0.2 (0.2) | 0.46 ± 0.1 (0.1) | 0.71 ± 0.2 (0.1) | 150 ± 130 (2) |

| Q151M | 1.4 ± 0.3 (2) | 0.64 ± 0.02 (4) | 23 ± 5 (4) | 11 ± 2 (3) | 7.8 ± 2 (1) | 17 ± 3 (2) | 160 ± 60 (2) |

| Q151M+4b | 6.3 ± 2 (7) | >10 (>100) | >100 (>20) | 39 ± 5 (13) | 18 ± 1 (3) | 56 ± 18 (8) | NDc |

EC50s were obtained for HeLa-P4 cells as described in Materials and Methods. Numbers in parentheses indicate EC50s relative to that of the wild-type virus. Values are the means ± standard errors from three or more independent experiments.

ND, not determined.

Variants hypersusceptible to other nucleoside analogs.

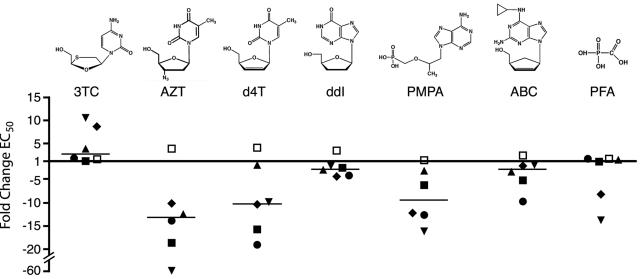

Several substitutions at position Q151 resulted in 10-fold or greater hypersusceptibility to AZT (Fig. 4B), suggesting that this residue is particularly important for substrate analog sensitivity. We therefore determined the response of the Q151 mutants to a panel of structurally diverse nucleoside analog inhibitors (Table 2 and Fig. 6). Consistent with previous reports, the Q151M mutation resulted in low-level resistance to d4T and ddI, and Q151M combined with A62V, V75I, F77L, and F116Y conferred higher levels of resistance to these two analogs (Table 2) (25, 36). In contrast, replacement of glycine, alanine, valine, isoleucine, or cysteine at position 151 increased HIV-1 sensitivity to several of the nucleoside analogs tested. Mutants Q151G and Q151C were 5- to 10-fold hypersusceptible to d4T, PMPA, and ABC (Table 2). Variants Q151V and Q151I were also 10-fold hypersusceptible to d4T and PMPA but showed only marginal hypersusceptibility to ABC. The Q151A mutation resulted in two- to threefold increases in d4T, PMPA, and ABC sensitivities. With the exception of methionine, each of the Q151 substitutions also conferred modest hypersusceptibility to ddI, with EC50s two- to fivefold lower than that of the wild type. Thus, several different substitutions at Q151 conferred a multinucleoside-hypersusceptible phenotype (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Hypersusceptibility of Q151 mutants to substrate analog inhibitors. Data from Fig. 4 and 5 and Table 2 are plotted to illustrate the change (n-fold) in EC50 for each Q151 mutant relative to that of wild-type HIV-1. Values above and below the x axis are resistant and hypersusceptible to drug, respectively. Horizontal bars indicate the median change (n-fold) in EC50 for each analog for the entire set of Q151 mutants. ▪, Q151G; □, Q151M; ▾, Q151V; ▴, Q151A; ♦, Q151I; •, Q151C.

In addition to Q151 mutations, specific substitutions at other motif B positions also conferred multinucleoside hypersusceptibilty. Mutants V148R and G155Q, both of which were hypersusceptible to AZT (Fig. 4A), were also four- to sevenfold hypersusceptible to PMPA (EC50s of 1.4 ± 0.2 μM and 0.90 ± 0.3 μM for V148R and G155Q, respectively, versus 5.9 ± 1.0 μM for the wild-type virus). The G155Q variant also exhibited three- to fivefold hypersusceptibility to d4T, ddI, and ABC but no change in PFA sensitivity (data not shown).

In summary, substitutions at 9 of the 11 RT motif B positions subjected to random mutagenesis altered viral susceptibility to one or more nucleoside analogs, and several mutations conferred altered sensitivity to the pyrophosphate analog PFA. Thus, residues throughout RT motif B play important roles in determining the substrate analog sensitivity of HIV-1.

DISCUSSION

The polymerase domain of HIV-1 RT contains structural motifs that are conserved in all reverse transcriptases and RNA-dependent viral polymerases (Fig. 1) (4, 21, 76). Amino acid residues within these motifs affect the fidelity of DNA synthesis and influence the sensitivity of HIV-1 to substrate analog inhibitors (40, 49, 64, 72). Motif B is particularly interesting because of its central position in the core polymerase structure (Fig. 1). Although a few mutations in HIV-1 RT motif B have been shown to confer drug resistance (25, 36, 39, 61, 67), the role of this structure in viral sensitivity to nucleoside and pyrophosphate analogs is largely unknown. To examine the functional importance of motif B in the context of replicating virus, we used random scanning mutagenesis to introduce random single amino acid replacements at 11 motif B codons. We then identified the range of replacements that preserve HIV-1 replication in culture (Table 1 and Fig. 2) and screened a subset of these infectious mutants for altered sensitivity to substrate analog inhibitors. The results demonstrate that residues throughout the targeted region of motif B affect viral susceptibility to substrate analogs (Fig. 3 to 5) and that specific substitutions, particularly at residue Q151, confer a multidrug-hypersusceptible phenotype (Table 2 and Fig. 6).

Previous efforts to identify determinants of dNTP selectivity have primarily used conventional site-directed mutagenesis to introduce single amino acid replacements in RT (40, 64). These variant RTs often exhibit severe impairments of polymerase function and are therefore unable to support viral replication (13, 18, 23, 28, 48, 56, 57, 59, 74). Here, we used cell culture to select replication-competent viruses from random pools of HIV-1 RT mutants. A sampling of 24 culture-selected mutants showed that most retained ≥50% of wild-type HIV-1 infectivity (Fig. 2). Thus, random scanning mutagenesis coupled to selection in culture is a facile approach for identifying catalytically active RT mutants. The strategies we used to enrich viable mutants and limit the proportion of wild-type HIV-1 in the random virus pools can readily be applied to other regions of the HIV-1 genome as well as other viruses for which a full-length plasmid clone is available.

A notable finding from our study was the magnitude and scope of substrate analog hypersusceptibility produced by mutations in RT motif B. Substitutions at 8 of the 11 residues analyzed increased the sensitivity of HIV-1 to one or more inhibitors, and several variants displayed 10-fold or greater analog hypersusceptibility (Fig. 4 and 5 and Table 2). Previous studies of HIV-1 variants have reported low-level (i.e., two- to fivefold) increases in viral sensitivity to nucleoside analogs (20, 39, 42, 61, 67, 68, 73), and replacements in conserved regions of herpesvirus and bacteriophage φ29 DNA polymerases occasionally confer low-level hypersusceptibility to substrate analogs (3, 7, 14, 19, 38, 70). Our data demonstrate that single amino acid substitutions in HIV-1 RT motif B can produce large increases in inhibitor sensitivity (Fig. 3 to 5) while preserving viral replication capacity (Fig. 2). We anticipate that other conserved RT motifs play a similar role in substrate analog susceptibility.

Our analysis of motif B suggests that nucleoside analog hypersusceptibility results from multiple biochemical mechanisms that are not necessarily mutually exclusive. First, a subset of motif B mutations may affect hypersensitivity to AZT by impairing the “primer unblocking” activity of RT (41). This inference is supported by the observation that specific mutations conferred both AZT hypersusceptibility and PFA resistance (Fig. 5), a phenotypic pattern that has been correlated with a loss of unblocking capacity (1, 42). Diminished primer unblocking function may occur with or without compromised RT polymerase activity, as suggested by the subset of hypersusceptible variants with reduced infectivity (Fig. 2 and 4).

Second, mutations in RT may confer nucleoside analog hypersusceptibilty by enhancing the efficiency of analog incorporation. Specific replacements at position Q151 increased the sensitivity of HIV-1 to multiple substrate analogs (Table 2), suggesting a direct effect on nucleotide selectivity (see below). Other mutations in motif B are likely to impart nucleoside analog hypersusceptibility indirectly by repositioning residues Y115 and M184 (Fig. 1B), which are key determinants of substrate specificity (40, 64). Taken together, our data suggest that motif B influences both the efficiency of the primer unblocking reaction and the selectivity of nucleotide incorporation by HIV-1 RT. Thus, motif B likely contributes to important enzyme-substrate interactions at multiple steps in the catalytic cycle of polymerization.

Our results demonstrate that residue Q151 is particularly important for substrate analog sensitivity (Table 2 and Fig. 6). Substitutions at this position presumably affect the interaction between RT and the incoming dNTP (Fig. 1) (24), thereby directly influencing analog binding and/or polymerization (10). It is well established that the Q151M mutation contributes to nucleoside analog resistance in HIV-1 and simian immunodeficiency virus (25, 36, 71). Here, we show that other Q151 substitutions confer broad-spectrum hypersusceptibility to structurally diverse nucleoside analogs, with up to a 60-fold increase in analog sensitivity. Moreover, we show that a subset of Q151 mutations also imparts hypersusceptibility to the pyrophosphate analog PFA. These data suggest that specific Q151 replacements in HIV-1 RT confer a general relaxation of polymerase active-site stringency. Additional experiments are required to examine the relationship between multidrug hypersusceptibility and other aspects of RT substrate selectivity, such as mispair formation and rNTP versus dNTP discrimination.

Residues that are structurally analogous to Q151 of HIV-1 RT also influence nucleoside inhibitor sensitivity in other DNA polymerases. In family A (E. coli DNA polymerase I-related) enzymes, a conserved aromatic residue (phenylalanine or tyrosine) that is positioned similarly to Q151 in the polymerase active site strongly influences dNTP versus dideoxynucleoside triphosphate selectivity (2, 35, 66). Substitutions at a structurally equivalent asparagine residue in family B (mammalian DNA polymerase α-related) polymerases also affect fidelity and/or nucleoside analog sensitivity (27, 31, 47). Taken together, these data indicate that residues analogous to Q151 influence the inhibitor sensitivities of polymerases from diverse organisms.

In patients receiving antiviral therapy, drug treatment occasionally selects for variants that are resistant to one or more components of the administered regimen but are hypersusceptible to other inhibitors. For example, mutations that emerge in vivo in response to 3TC, ddI, PFA, or certain nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors can confer hypersusceptibility to AZT and “resensitize” AZT-resistant viruses (20, 30, 32, 42, 63, 68, 75). Increased viral sensitivity to protease inhibitors and nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors in clinical isolates of HIV-1 has also been reported (16, 34, 37, 58). Our analysis suggests that there are a number of RT mutations that confer hypersusceptibility to AZT and other nucleoside analogs. These mutations may contribute to observed differences in drug sensitivity among “wild-type” HIV-1 isolates (22, 50) and could potentially influence the efficacy of nucleoside-containing antiretroviral regimens.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tom North, Masanori Ogawa, and Tina Albertson for critical reading of the manuscript and Crystal Pyrak for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported by Public Health Service grants R01 AI34834 to B.D.P. and F32 AI10139 to R.A.S.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arion, D., N. Sluis-Cremer, and M. A. Parniak. 2000. Mechanism by which phosphonoformic acid resistance mutations restore 3′-azido-3′-deoxythymidine (AZT) sensitivity to AZT-resistant HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. J. Biol. Chem. 275:9251-9255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Astatke, M., N. D. Grindley, and C. M. Joyce. 1998. How E. coli DNA polymerase I (Klenow fragment) distinguishes between deoxy- and dideoxynucleotides. J. Mol. Biol. 278:147-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bestman-Smith, J., and G. Boivin. 2003. Drug resistance patterns of recombinant herpes simplex virus DNA polymerase mutants generated with a set of overlapping cosmids and plasmids. J. Virol. 77:7820-7829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruenn, J. A. 2003. A structural and primary sequence comparison of the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerases. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:1821-1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Charneau, P., G. Mirambeau, P. Roux, S. Paulous, H. Buc, and F. Clavel. 1994. HIV-1 reverse transcription. A termination step at the center of the genome. J. Mol. Biol. 241:651-662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen, C., and H. Okayama. 1987. High-efficiency transformation of mammalian cells by plasmid DNA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 7:2745-2752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cihlar, T., M. D. Fuller, and J. M. Cherrington. 1998. Characterization of drug resistance-associated mutations in the human cytomegalovirus DNA polymerase gene by using recombinant mutant viruses generated from overlapping DNA fragments. J. Virol. 72:5927-5936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coffin, J. M., S. H. Hughes, and H. E. Varmus (ed.). 1997. Retroviruses. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y. [PubMed]

- 9.Cunningham, B. C., and J. A. Wells. 1989. High-resolution epitope mapping of hGH-receptor interactions by alanine-scanning mutagenesis. Science 244:1081-1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deval, J., B. Selmi, J. Boretto, M. P. Egloff, C. Guerreiro, S. Sarfati, and B. Canard. 2002. The molecular mechanism of multidrug resistance by the Q151M human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase and its suppression using alpha-boranophosphate nucleotide analogues. J. Biol. Chem. 277:42097-42104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diamond, T. L., G. Souroullas, K. K. Weiss, K. Y. Lee, R. A. Bambara, S. Dewhurst, and B. Kim. 2003. Mechanistic understanding of an altered fidelity simian immunodeficiency virus reverse transcriptase mutation, V148I, identified in a pig-tailed macaque. J. Biol. Chem. 278:29913-29924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ding, J., K. Das, Y. Hsiou, S. G. Sarafianos, A. D. Clark, A. Jacobo-Molina, C. Tantillo, S. H. Hughes, and E. Arnold. 1998. Structure and functional implications of the polymerase active site region in a complex of HIV-1 RT with a double-stranded DNA template-primer and an antibody Fab fragment at 2.8 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 284:1095-1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao, G., and S. P. Goff. 1998. Replication defect of Moloney murine leukemia virus with a mutant reverse transcriptase that can incorporate ribonucleotides and deoxyribonucleotides. J. Virol. 72:5905-5911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gibbs, J. S., H. C. Chiou, K. F. Bastow, Y. C. Cheng, and D. M. Coen. 1988. Identification of amino acids in herpes simplex virus DNA polymerase involved in substrate and drug recognition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85:6672-6676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gonzales, M. J., T. D. Wu, J. Taylor, I. Belitskaya, R. Kantor, D. Israelski, S. Chou, A. R. Zolopa, W. J. Fessel, and R. W. Shafer. 2003. Extended spectrum of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase mutations in patients receiving multiple nucleoside analog inhibitors. AIDS 17:791-799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gonzalez, L. M., R. M. Brindeiro, M. Tarin, A. Calazans, M. A. Soares, S. Cassol, and A. Tanuri. 2003. In vitro hypersusceptibility of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype C protease to lopinavir. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:2817-2822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gotte, M. 2004. Inhibition of HIV-1 reverse transcription: basic principles of drug action and resistance. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2:707-716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gutierrez-Rivas, M., A. Ibanez, M. A. Martinez, E. Domingo, and L. Menendez-Arias. 1999. Mutational analysis of Phe160 within the “palm” subdomain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase. J. Mol. Biol. 290:615-625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hall, J. D., and S. Woodward. 1989. Aphidicolin resistance in herpes simplex virus type 1 appears to alter substrate specificity in the DNA polymerase. J. Virol. 63:2874-2876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hammond, J. L., D. L. Koontz, H. Z. Bazmi, J. R. Beadle, S. E. Hostetler, G. D. Kini, K. A. Aldern, D. D. Richman, K. Y. Hostetler, and J. W. Mellors. 2001. Alkylglycerol prodrugs of phosphonoformate are potent in vitro inhibitors of nucleoside-resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and select for resistance mutations that suppress zidovudine resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1621-1628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hansen, J. L., A. M. Long, and S. C. Schultz. 1997. Structure of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase of poliovirus. Structure 5:1109-1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harrigan, P. R., J. S. Montaner, S. A. Wegner, W. Verbiest, V. Miller, R. Wood, and B. A. Larder. 2001. World-wide variation in HIV-1 phenotypic susceptibility in untreated individuals: biologically relevant values for resistance testing. AIDS 15:1671-1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harris, D., N. Kaushik, P. K. Pandey, P. N. Yadav, and V. N. Pandey. 1998. Functional analysis of amino acid residues constituting the dNTP binding pocket of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. J. Biol. Chem. 273:33624-33634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang, H., R. Chopra, G. L. Verdine, and S. C. Harrison. 1998. Structure of a covalently trapped catalytic complex of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase: implications for drug resistance. Science 282:1669-1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iversen, A. K., R. W. Shafer, K. Wehrly, M. A. Winters, J. I. Mullins, B. Chesebro, and T. C. Merigan. 1996. Multidrug-resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 strains resulting from combination antiretroviral therapy. J. Virol. 70:1086-1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jacobo-Molina, A., J. Ding, R. G. Nanni, A. D. Clark, Jr., X. Lu, C. Tantillo, R. L. Williams, G. Kamer, A. L. Ferris, P. Clark, A. Hizi, S. H. Hughes, and E. Arnold. 1993. Crystal structure of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase complexed with double-stranded DNA at 3.0 Å resolution shows bent DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:6320-6324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kamiyama, T., M. Kurokawa, and K. Shiraki. 2001. Characterization of the DNA polymerase gene of varicella-zoster viruses resistant to acyclovir. J. Gen. Virol. 82:2761-2765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaushik, N., T. T. Talele, P. K. Pandey, D. Harris, P. N. Yadav, and V. N. Pandey. 2000. Role of glutamine 151 of human immunodeficiency virus type-1 reverse transcriptase in substrate selection as assessed by site-directed mutagenesis. Biochemistry 39:2912-2920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klarmann, G. J., R. A. Smith, R. F. Schinazi, T. W. North, and B. D. Preston. 2000. Site-specific incorporation of nucleoside analogs by HIV-1 reverse transcriptase and the template grip mutant P157S. Template interactions influence substrate recognition at the polymerase active site. J. Biol. Chem. 275:359-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Larder, B. A. 1992. 3′-Azido-3′-deoxythymidine resistance suppressed by a mutation conferring human immunodeficiency virus type 1 resistance to nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 36:2664-2669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Larder, B. A., S. D. Kemp, and G. Darby. 1987. Related functional domains in virus DNA polymerases. EMBO J. 6:169-175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Larder, B. A., S. D. Kemp, and P. R. Harrigan. 1995. Potential mechanism for sustained antiretroviral efficacy of AZT-3TC combination therapy. Science 269:696-699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Larder, B. A., S. D. Kemp, and D. J. Purifoy. 1989. Infectious potential of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase mutants with altered inhibitor sensitivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:4803-4807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leigh Brown, A. J., S. D. Frost, B. Good, E. S. Daar, V. Simon, M. Markowitz, A. C. Collier, E. Connick, B. Conway, J. B. Margolick, J. P. Routy, J. Corbeil, N. S. Hellmann, D. D. Richman, and S. J. Little. 2004. Genetic basis of hypersusceptibility to protease inhibitors and low replicative capacity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 strains in primary infection. J. Virol. 78:2242-2246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lim, S. E., M. V. Ponamarev, M. J. Longley, and W. C. Copeland. 2003. Structural determinants in human DNA polymerase gamma account for mitochondrial toxicity from nucleoside analogs. J. Mol. Biol. 329:45-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maeda, Y., D. J. Venzon, and H. Mitsuya. 1998. Altered drug sensitivity, fitness, and evolution of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 with pol gene mutations conferring multi-dideoxynucleoside resistance. J. Infect. Dis. 177:1207-1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martinez-Picado, J., T. Wrin, S. D. Frost, B. Clotet, L. Ruiz, A. J. Brown, C. J. Petropoulos, and N. T. Parkin. 2005. Phenotypic hypersusceptibility to multiple protease inhibitors and low replicative capacity in patients who are chronically infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 79:5907-5913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matsumoto, K., C. I. Kim, H. Kobayashi, H. Kanehiro, and H. Hirokawa. 1990. Aphidicolin-resistant DNA polymerase of bacteriophage phi 29 APHr71 mutant is hypersensitive to phosphonoacetic acid and butylphenyldeoxyguanosine 5′-triphosphate. Virology 178:337-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mellors, J. W., H. Z. Bazmi, R. F. Schinazi, B. M. Roy, Y. Hsiou, E. Arnold, J. Weir, and D. L. Mayers. 1995. Novel mutations in reverse transcriptase of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reduce susceptibility to foscarnet in laboratory and clinical isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:1087-1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Menendez-Arias, L. 2002. Molecular basis of fidelity of DNA synthesis and nucleotide specificity of retroviral reverse transcriptases. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 71:91-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meyer, P. R., S. E. Matsuura, A. M. Mian, A. G. So, and W. A. Scott. 1999. A mechanism of AZT resistance: an increase in nucleotide-dependent primer unblocking by mutant HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. Mol. Cell 4:35-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meyer, P. R., S. E. Matsuura, D. Zonarich, R. R. Chopra, E. Pendarvis, H. Z. Bazmi, J. W. Mellors, and W. A. Scott. 2003. Relationship between 3′-azido-3′-deoxythymidine resistance and primer unblocking activity in foscarnet-resistant mutants of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase. J. Virol. 77:6127-6137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Milazzo, L., S. Rusconi, L. Testa, S. La Seta-Catamancio, M. Galazzi, S. Kurtagic, P. Citterio, M. Gianotto, A. Grassini, F. Adorni, A. d'Arminio-Monforte, M. Galli, and M. Moroni. 1999. Evidence of stavudine-related phenotypic resistance among zidovudine-pretreated HIV-1-infected subjects receiving a therapeutic regimen of stavudine plus lamivudine. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 22:101-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Motulsky, H. J., and A. Christopoulos. 2003. Fitting models to biological data using linear and nonlinear regression. A practical guide to curve fitting. GraphPad, Inc., San Diego, Calif.

- 45.Muller, R., O. Poch, M. Delarue, D. H. Bishop, and M. Bouloy. 1994. Rift Valley fever virus L segment: correction of the sequence and possible functional role of newly identified regions conserved in RNA-dependent polymerases. J. Gen. Virol. 75:1345-1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nijhuis, M., R. Schuurman, D. de Jong, R. van Leeuwen, J. Lange, S. Danner, W. Keulen, T. de Groot, and C. A. Boucher. 1997. Lamivudine-resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variants (184V) require multiple amino acid changes to become co-resistant to zidovudine in vivo. J. Infect. Dis. 176:398-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ogawa, M., S. Limsirichaikul, A. Niimi, S. Iwai, S. Yoshida, and M. Suzuki. 2003. Distinct function of conserved amino acids in the fingers of Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA polymerase alpha. J. Biol. Chem. 278:19071-19078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Olivares, I., V. Sanchez-Merino, M. A. Martinez, E. Domingo, C. Lopez-Galindez, and L. Menendez-Arias. 1999. Second-site reversion of a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase mutant that restores enzyme function and replication capacity. J. Virol. 73:6293-6298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Parikh, U., C. Calef, B. Larder, R. Schinazi, and J. W. Mellors. 2001. Mutations in retroviral genes associated with drug resistance, p. 191-277. In C. Kuiken, B. Foley, B. Hahn, P. Marx, F. McCutchan, J. Mellors, S. Wolinski, and B. Korber (ed.), HIV-1 sequence compendium. Theoretical Biology and Biophysics Group, Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos, N.Mex.

- 50.Parkin, N. T., N. S. Hellmann, J. M. Whitcomb, L. Kiss, C. Chappey, and C. J. Petropoulos. 2004. Natural variation of drug susceptibility in wild-type human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:437-443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pear, W. S., G. P. Nolan, M. L. Scott, and D. Baltimore. 1993. Production of high-titer helper-free retroviruses by transient transfection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:8392-8396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Picard, V., E. Angelini, A. Maillard, E. Race, F. Clavel, G. Chene, F. Ferchal, and J. M. Molina. 2001. Comparison of genotypic and phenotypic resistance patterns of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates from patients treated with stavudine and didanosine or zidovudine and lamivudine. J. Infect. Dis. 184:781-784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Poch, O., I. Sauvaget, M. Delarue, and N. Tordo. 1989. Identification of four conserved motifs among the RNA-dependent polymerase encoding elements. EMBO J. 8:3867-3874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rezende, L. F., K. Curr, T. Ueno, H. Mitsuya, and V. R. Prasad. 1998. The impact of multidideoxynucleoside resistance-conferring mutations in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase on polymerase fidelity and error specificity. J. Virol. 72:2890-2895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schinazi, R. F., R. M. Lloyd, Jr., M. H. Nguyen, D. L. Cannon, A. McMillan, N. Ilksoy, C. K. Chu, D. C. Liotta, H. Z. Bazmi, and J. W. Mellors. 1993. Characterization of human immunodeficiency viruses resistant to oxathiolane-cytosine nucleosides. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:875-881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sharma, B., N. Kaushik, K. Singh, S. Kumar, and V. N. Pandey. 2002. Substitution of conserved hydrophobic residues in motifs B and C of HIV-1 RT alters the geometry of its catalytic pocket. Biochemistry 41:15685-15697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sharma, B., N. Kaushik, A. Upadhyay, S. Tripathi, K. Singh, and V. N. Pandey. 2003. A positively charged side chain at position 154 on the beta8-alphaE loop of HIV-1 RT is required for stable ternary complex formation. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:5167-5174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shulman, N., A. R. Zolopa, D. Passaro, R. W. Shafer, W. Huang, D. Katzenstein, D. M. Israelski, N. Hellmann, C. Petropoulos, and J. Whitcomb. 2001. Phenotypic hypersusceptibility to non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors in treatment-experienced HIV-infected patients: impact on virological response to efavirenz-based therapy. AIDS 15:1125-1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Singh, K., N. Kaushik, J. Jin, M. Madhusudanan, and M. J. Modak. 2000. Role of Q190 of MuLV RT in ddNTP resistance and fidelity of DNA synthesis: a molecular model of interactions with substrates. Protein Eng. 13:635-643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Smith, R. A., D. J. Anderson, and B. D. Preston. 2004. Purifying selection masks the mutational flexibility of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. J. Biol. Chem. 279:26726-26734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Smith, R. A., G. J. Klarmann, K. M. Stray, U. K. von Schwedler, R. F. Schinazi, B. D. Preston, and T. W. North. 1999. A new point mutation (P157S) in the reverse transcriptase of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 confers low-level resistance to (−)-β-2′,3′-dideoxy-3′-thiacytidine. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:2077-2080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Smith, R. A., K. M. Remington, B. D. Preston, R. F. Schinazi, and T. W. North. 1998. A novel point mutation at position 156 of reverse transcriptase from feline immunodeficiency virus confers resistance to the combination of (−)-β-2′,3′-dideoxy-3′-thiacytidine and 3′-azido-3′-deoxythymidine. J. Virol. 72:2335-2340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.St. Clair, M. H., J. L. Martin, G. Tudor-Williams, M. C. Bach, C. L. Vavro, D. M. King, P. Kellam, S. D. Kemp, and B. A. Larder. 1991. Resistance to ddI and sensitivity to AZT induced by a mutation in HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. Science 253:1557-1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Svarovskaia, E. S., S. R. Cheslock, W. H. Zhang, W. S. Hu, and V. K. Pathak. 2003. Retroviral mutation rates and reverse transcriptase fidelity. Front. Biosci. 8:d117-d134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Swingler, S., P. Gallay, D. Camaur, J. Song, A. Abo, and D. Trono. 1997. The Nef protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 enhances serine phosphorylation of the viral matrix. J. Virol. 71:4372-4377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tabor, S., and C. C. Richardson. 1995. A single residue in DNA polymerases of the Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I family is critical for distinguishing between deoxy- and dideoxyribonucleotides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:6339-6343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tachedjian, G., D. J. Hooker, A. D. Gurusinghe, H. Bazmi, N. J. Deacon, J. Mellors, C. Birch, and J. Mills. 1995. Characterisation of foscarnet-resistant strains of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Virology 212:58-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tachedjian, G., J. Mellors, H. Bazmi, C. Birch, and J. Mills. 1996. Zidovudine resistance is suppressed by mutations conferring resistance of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 to foscarnet. J. Virol. 70:7171-7181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tisdale, M., S. D. Kemp, N. R. Parry, and B. A. Larder. 1993. Rapid in vitro selection of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 resistant to 3′-thiacytidine inhibitors due to a mutation in the YMDD region of reverse transcriptase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:5653-5656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tsurumi, T., K. Maeno, and Y. Nishiyama. 1987. A single-base change within the DNA polymerase locus of herpes simplex virus type 2 can confer resistance to aphidicolin. J. Virol. 61:388-394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Van Rompay, K. K., J. L. Greenier, M. L. Marthas, M. G. Otsyula, R. P. Tarara, C. J. Miller, and N. C. Pedersen. 1997. A zidovudine-resistant simian immunodeficiency virus mutant with a Q151M mutation in reverse transcriptase causes AIDS in newborn macaques. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:278-283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Vivet-Boudou, V., J. Didierjean, C. Isel, and R. Marquet. 2006. Nucleoside and nucleotide inhibitors of HIV-1 replication. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 63:163-186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wainberg, M. A., M. D. Miller, Y. Quan, H. Salomon, A. S. Mulato, P. D. Lamy, N. A. Margot, K. E. Anton, and J. M. Cherrington. 1999. In vitro selection and characterization of HIV-1 with reduced susceptibility to PMPA. Antivir. Ther. 4:87-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Weiss, K. K., S. J. Isaacs, N. H. Tran, E. T. Adman, and B. Kim. 2000. Molecular architecture of the mutagenic active site of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase: roles of the beta 8-alpha E loop in fidelity, processivity, and substrate interactions. Biochemistry 39:10684-10694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.White, K. L., N. A. Margot, J. K. Ly, J. M. Chen, A. S. Ray, M. Pavelko, R. Wang, M. McDermott, S. Swaminathan, and M. D. Miller. 2005. A combination of decreased NRTI incorporation and decreased excision determines the resistance profile of HIV-1 K65R RT. AIDS 19:1751-1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Xu, X., Y. Liu, S. Weiss, E. Arnold, S. G. Sarafianos, and J. Ding. 2003. Molecular model of SARS coronavirus polymerase: implications for biochemical functions and drug design. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:7117-7130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]