Abstract

Purpose

The Study of Progression of Adult Nearsightedness (SPAN) is a 5-year observational study to determine the risk factors associated with adult myopia progression. Candidate risk factors include: a high proportion of time spent performing near tasks, performing near tasks at a close distance, high accommodative convergence/accommodation (AC/A) ratio, and high accommodative lag.

Methods

Subjects between 25 and 35 years of age, with at least −0.50 D spherical equivalent of myopia (cycloplegic autorefraction), were recruited from the faculty and staff of The Ohio State University. Progression is defined as an increase in myopia of at least −0.75 D spherical equivalent as determined by cycloplegic autorefraction. Annual testing includes visual acuity, noncycloplegic autorefraction and autokeratometry, phoria, accommodative lag, response AC/A ratio, cycloplegic autorefraction, videophakometry, ultrasound, and partial coherence interferometry (IOLMaster). Participants’ near activities were assessed using the experience sampling method (ESM). Subjects carried a pager for two 1-week periods and were paged randomly throughout the day. Each time they were paged, they dialed into an automated telephone survey and reported their visual activity at that time. From these responses, the proportion of time spent performing near work was estimated.

Results

Three-hundred ninety-six subjects were enrolled in SPAN. The mean (± standard deviation) age at baseline was 30.7 ± 3.5 years, 66% were female, 80% were white, 11% were black, and 8% were Asian/Pacific Islander. The mean level of myopia (spherical equivalent) was −3.54 ± 1.77 D, the mean axial length by IOLMaster was 24.6 ± 1.1 mm, and subjects were 1.7 ± 4.0 Δ exophoric. Refractive error was associated with the number of myopic parents (F = 3.83, p = 0.023), and the number of myopic parents was associated with the age of myopia onset (χ2 = 13.78, p = 0.001). In a multivariate analysis, onset of myopia (early vs. late) still had a significant effect on degree of myopia (F = 115.1, p < 0.001), but the number of myopic parents was no longer significant (F = 0.65, p = 0.52). For the ESM, the most frequently reported visual task was computer use (mean, 18.9%; range, 0–60.0%) and, overall, subjects reported near work activity 34.1% of the time (range, 0–67.3%).

Conclusions

The design of SPAN and the baseline characteristics of the cohort have been described. Parental history of myopia is related to the degree of myopia at baseline, but this effect is mediated by the age of onset of myopia.

Keywords: myopia, adults, risk factors, accommodation, near work, epidemiology

Most myopia develops during the school years1 and stabilizes in the teenage years.2 Nonetheless, a number of individuals will show myopic changes after entering college.1 This may manifest as an increase in myopia in a previously myopic subject—adult myopia progression—or the onset of myopia in a previously emmetropic or hyperopic individual—adult-onset myopia. The National Research Council Committee on Vision Working Group on Myopia Prevalence and Progression reviewed over 500 articles on myopia.3 On the basis of the studies reviewed, the report concluded that up to 40% of low hyperopes and emmetropes entering college and military academies are likely to become myopic by the age of 25 years. Conversely, in populations in which college graduates are excluded, <10% of individuals become myopic as adults.

There have been a number of reports of myopia progression in adulthood, and a selection is summarized in Table 1.4–13 Waring et al., for example, reported a mean myopic shift of −0.65 D across 10 years in the fellow eye of 47 Prospective Evaluation of Radial Keratotomy (PERK) study patients who elected not to undergo radial keratotomy on their second eye.8 Adams and McBrien found that 50% of clinical microscopists reported significant myopia progression since joining the profession.6 A number of studies, including our own, have documented myopia progression in subjects in their thirties.8,10,13 This agrees with eye care practitioners’ descriptions of adult myopia progression anecdotally associated with professional or graduate school, increasing computer use, or both.14

TABLE 1.

Previous studies of adult myopia progressiona

| Study | Sample | Age (years) | Duration | Key finding | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prospective studies | |||||

| Grosvenor and Scott7 | 79 students | 18–34 at entry; mean, 21.5 | 3 years | 26% progressed by at least −0.50 D (27% of myopes) | 33% loss to follow up |

| Waring et al.8 | 47 radial keratotomy patients | 21–58 at entry; mean, 33.5 | 10 years | Mean myopic shift = −0.65 D | Potential bias in group who declined second eye surgery |

| McBrien and Adams10 | 166 microscopists | 21–63 at entry; mean, 29.3 | 2 years | 48% progressed by at least −0.37 D | Only one professional group |

| Kinge et al.11, 12 | 192 students | 20.6 at entry | 3 years | Mean myopic shift = −0.51 D | Limited age range, only one professional group |

| Retrospective studies | |||||

| Zadnik and Mutti4 | 87 law students | Early 20s | Variable | 47% progressed by at least −0.50 D | Clinic-based sample, with presentation bias |

| O’Neal and Connon5 | 497 military recruits | 17–21 at entry; mean, 18.5 | 2.5 years | 37% progressed by at least −0.50 D (55% of myopes) | Limited age range, limited follow up, males only |

| Adams and McBrien6 | 251 microscopists | 21–63 at time of study; mean, 29.7 | Variable | 49% reported adult progression | Self-reported data, poorly defined progression |

| Ellingsen et al.9 | 413 practice patients | Grouped by decade | 10 years | Subjects increased by −0.39 D during their 30s | Retrospective, potential bias |

| Bullimore et al.13 | 291 contact lens wearers | 28.5 at entry | 5 years | 21.3% progressed by at least −1.00 D | Retrospective, contact lens wearers only |

Studies are grouped into prospective and retrospective designs and arranged by publication date.

None of the aforementioned studies has demonstrated a compelling relationship between adult myopia progression and near work. Clinicians may tell their patients that their adult myopia progression is related to their computer use. Nonetheless, there is little evidence to support this assertion. Rather, the association has been based on the occupation and education levels of different groups of subjects.

We describe the design and baseline characteristics of a 5-year observational study of myopia progression in adults with detailed measures of near work and other risk factors. At study end, subjects will be categorized into those whose myopia progressed and those whose refractive error was stable. The two groups will be analyzed with respect to near work-related risk factors. In particular, two broad categories of risk factors will be assessed: the proportion of time a subject spends reading or performing other forms of near work and selected characteristics of the subjects’ ocular accommodation and vergence.

The rationale for studying near work-related risk factors is based on the clinic and research community’s belief that near work causes adult myopic progression,3 reports of myopic changes in occupations involving large amounts of near work,4,6,10 and reports of an association between myopic progression and hours of near work in university students.11,12

The rationale for studying accommodation-related risk factors is the numerous publications implicating accommodation and vergence in the etiology of myopia. A number of researchers have hypothesized that underaccommodation, or accommodative lag, induces myopia in humans by a similar mechanism to that which produces experimental myopia in animals.15–18 This hypothesis is supported by studies in children and adults showing greater accommodative lag in myopes compared with emmetropes.15,19 Subsequent studies have shown that accommodative lag is greater in children20 and adults.21 whose myopia is increasing than in those whose myopia is stable.

Studies have also linked the interaction between accommodation and convergence—usually characterized by the accommodative convergence/accommodation (AC/A) ratio—to the etiology of myopia. Cross-sectional studies in children22 and adults17,23 have found that higher AC/A ratios are associated with myopia. Jiang found that adults whose myopia developed or progressed over a 2- to 3-year period had significantly higher response AC/A ratios than those whose refractive error was stable. Likewise, Mutti et al. reported that a high response AC/A ratio is a significant risk factor for the onset of myopia in children.24

METHODS

The tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki were followed throughout the study. The Ohio State University Office of Research Risk Protection approved the protocol, and informed consent was obtained from all subjects after the protocol had been explained.

Study Design

A 5-year prospective, observational study was undertaken to determine the risk factors associated with adult myopia progression. The primary risk factors to be evaluated are:

Performing near work for a greater proportion of the day;

Performing near tasks at a close distance;

A high response AC/A ratio; and

A high accommodative lag.

Subjects participate in two concurrent components of the study. First, they attend for an annual visit every year for 5 years (a total of six visits). Second, the subjects’ daily activities are assessed for 1 week every 6 months using the experience sampling method (ESM).25

Definition of Myopia Progression

The study’s primary outcome measure is change in cycloplegic autorefraction measured with the Humphrey 599 (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, CA). Autorefraction was chosen over subjective refraction based on autorefraction’s superior repeatability.26,27 Cycloplegia is necessary to discriminate bona fide changes in refractive error from those resulting from transient near work-induced accommodative effects.28

Myopia progression is operationally defined as an increase in myopia of at least −0.75 D spherical equivalent in the right eye at any time over the 5 years. At study end, subjects will be divided into progressors and nonprogressors for data analysis based on this criterion. Only the right eye is measured so that the cycloplegic agent may be applied to one eye only, thus minimizing the respondent burden in this working population. A value of −0.75 D can be regarded as a meaningful change producing a clear reduction in visual acuity.29 It also exceeds the variability of the autorefractor (95% limits of agreement = ± 0.19 D, unpublished data). Nonetheless, in publication of our main findings, we will present data using several different criteria for progression along with analyses that treat refractive error as a continuous variable. This will allow the community to examine the robustness of any reported effects.

Confirmatory Visit

Misclassification of myopia progression is minimized by requiring a confirmatory visit. Subjects found to have progressed at an annual visit are required to have their cycloplegic autorefraction repeated within 3 months to confirm progression. At the confirmatory visit, only cycloplegic autorefraction is performed. If the change from baseline is at least −0.75 D for this visit, then progression is confirmed and the subject is classified as a progressor. If the change from baseline is less than −0.75 D, the subject is classified as a nonprogressor. All subjects attending a confirmatory visit return for their next annual visit based on their original schedule. Subjects continue to attend for annual visits after progression has been confirmed so that higher amounts of progression can be documented and are available for analysis.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Subjects were required to:

Be between 25 and 35 years of age at the time of enrollment;

Have at least 20/25 best-corrected visual acuity in each eye;

Have at least −0.50 D of myopia in both meridians of both eyes as measured by cycloplegic autorefraction but not exceeding −7.75 D in any one meridian (as measured in the spectacle plane);

Not have diabetes, active ocular, neurologic, or muscular diseases, or have had refractive surgery; and

Not have strabismus.

The decision to exclude subjects with strabismus was made after two with a constant deviation had already been enrolled in the study. These subjects continue to be followed. There were no exclusion criteria based on astigmatism or anisometropia.

Subject Recruitment

Subjects were recruited, predominantly, from the faculty and staff of the Ohio State University (OSU) in Columbus. A comprehensive database was provided by the OSU Office of Human Resources. All potential subjects were sent a letter through campus mail inviting them to participate. If the employee did not have a valid campus address, a letter was sent to the home address. A response form was enclosed that subjects could complete, staple, and drop in the campus mail. The subject could also e-mail or phone the study coordinator. Subjects who did not respond within 3 weeks were sent an e-mail containing the recruitment letter to their campus account. If there was no response after approximately 3 to 4 weeks, a letter was sent to the home addresses, if available.

After 9 months, the database was updated to include new hires and employees reaching or approaching their 25th birthday. Letters were sent to these potential subjects along with those who had not responded to previous mailings. In addition, recruitment posters were displayed around campus and on the campus bus service.

All individuals that responded and were interested were contacted by e-mail or telephone and asked a series of questions to determine their eligibility: did they wear glasses or contact lenses for distance vision, were they diabetic, and so on. Subjects who passed this screening were probably eligible and thus scheduled for a baseline examination.

Baseline and Annual Visit Measurements

The baseline and annual visit last 1 hour and include the following measurements:

Visual acuity with habitual correction;

Autorefraction and autokeratometry;

Near phoria;

Accommodative lag;

Response AC/A ratio;

Cycloplegic instillation;

Cycloplegic autorefraction;

Videophakometry;

Partial coherence interferometry; and

Ultrasound (A scan).

Visual Acuity

Monocular visual acuity was measured with the subject’s habitual correction (spectacles or contact lenses) using Bailey-Lovie charts30 and a standardized protocol31 to determine study eligibility. Testing was performed at a distance of 6 meters and the total number of letters correct recorded. Any subject whose visual acuity was poorer than 20/25 (40 letters) in either eye was tested on the autorefractor and retested with the resultant refraction in a trial frame. Subjects who still did not meet the eligibility criterion received a subjective refraction and were retested with this prescription in a trial frame. If this visual acuity was poorer than 20/25, the subject was considered ineligible for the study.

Noncycloplegic Autorefraction and Autokeratometry

Before cycloplegia, refractive error and corneal curvature were measured on both eyes with the Humphrey 599. One valid reading was taken per eye. For contact lens wearers, these measurements were made after the measurement of phoria and accommodation.

Near Phoria

Near phoria was selected as a secondary risk factor and as a confirmatory measure for our response AC/A measurements. A distance cover test was first performed and any tropia or phoria was estimated. Near phoria was measured at near with the subject’s habitual correction using a prism-neutralized cover test. If the subject did not bring his or her correction, his or her prescription as determined by the autorefractor was placed in a trial frame. The subject fixated a five-point letter target at 40 cm. The examiner covered the subject’s right eye with the occluder for at least 2 seconds and then quickly transferred the occluder to the left eye for at least 2 seconds. Care was taken so binocular fixation did not occur. This procedure was repeated several times with the examiner watching the uncovered eye for movement. Any movement was estimated and a prism placed in front of the right eye using a 2-Δ step prism bar. Prism was increased in 2-Δ steps until the movement was neutralized and then reversed. The recorded phoria was the midway point between two prisms that gave the smallest observable eso and exo movements.

Response AC/A Ratio and Accommodative Lag

Accommodative lag and response AC/A ratio were among the primary risk factors evaluated in this study and were measured using a modification of the Canon R-1 auto-refractor described by Mutti et al.24 Accommodation was stimulated by a 4 × 4 grid of eight-point letters (1.45 mm). Accessory lights produced a target luminance between 30 and 50 cd/m2. This was viewed by the right eye through a +6.50 D Badal lens. Accommodative stimulus levels of 0, 2, and 4 D relative to optical infinity were used and the accommodative response measured using the autorefractor. At least five autorefractor readings were taken with the right eye in primary gaze.

The amount of convergence of the left eye was monitored on a second channel. A focused infrared LED light source was mounted on top of a CCD camera aimed at the left eye of the subject by way of an infrared reflecting mirror. The CCD camera was fitted with a 50-mm focal length F1.4 C-mount lens on a 20-mm extension tube with the camera’s stock infrared filter removed. The infrared LED produced Purkinje images I and IV (from the anterior surface of the cornea and the posterior surface of the lens, respectively). Eye rotation was monitored by measuring the relative lateral movement of these two images, similar to eye trackers.32,33 The two data channels, accommodative response from the right eye and eye movement from the left eye, were recorded simultaneously by a video multiplexer. This unit displayed a divided image of both channels on a monitor but maintained resolution by recording full frames of video alternating at 25 Hz on a standard VHS recorder for later analysis.

The protocol for measurement was as follows. A subject was placed behind the Canon R-1 and aligned. An infrared filter (Wratten 89B) was placed in front of the left eye. This filter only passed wavelengths longer than 680 nm, disrupting fusion by being opaque to the observer but remaining transparent to the CCD camera. Each subject was calibrated by making a 10° eye movement alternating fixation two times between targets printed on a card on the Badal track. Calibration was important to reduce the variability of the technique.24 Accommodation was then measured as described at each stimulus level while eye position was recorded on the second channel.

Subjects wore their habitual spectacle or contact lens correction. If the subject wore rigid contact lenses, the subject’s own right lens was left in place and the left lens was removed before testing. Subjects who did not bring a spectacle or contact lens correction wore a plastic frame with trial lenses (sphere and cylinder) in front of the right eye based on the autorefraction results and the left eye covered by an infrared filter cut to fit the left side of the plastic frame and secured by silicone caulking.

Eye position data were extracted from the multiplexer videotapes by a certified video reader. Measurements were made of the lateral separation of Purkinje images I and IV using a frame grabber and Image Analyst version 8.1.24

Accommodative lag was determined for stimulus levels of 2 D and 4 D from the measurement of AC/A ratio by subtracting the measured accommodative response (mean of five readings) from the stimulus level.

Cycloplegic Drop Instillation

After the previously mentioned tests, two drops of 1% tropicamide were instilled into the subject’s right eye only separated by 5 minutes. Tropicamide was chosen for its short duration of action, few side effects, and similar effectiveness to cyclopentolate.34,35

Questionnaire

Subjects completed a questionnaire at each visit. For the baseline visit, the questionnaire included questions about age, gender, level of education, race, age of onset of myopia, family history of myopia, occupation, and contact lens wear. For all visits, the questionnaire asked about the amount of time spent performing activities such as reading, computer, and driving, at home and at work, although the ESM is used as the primary assessment of daily activities.

Cycloplegic Autorefraction

Thirty minutes after instillation of the first drop of tropicamide, refractive error was measured for the right eye only using the Humphrey 599 autorefractor. Measurements were taken until three valid readings were obtained. Refractive error readings (sphere, cylinder, and axis) were averaged using the methods described by Thibos et al.36

Videophakometry

Anterior and posterior crystalline lens curvatures were measured on the right eye only using videophakometry.37,38 Pairs of Purkinje images are produced by a dual fiberoptic light source at optical infinity, captured by a CCD video camera, and recorded on videotape. The left eye was occluded with an eye patch while the subject monocularly fixated a red LED mounted on a movable arm to position and record Purkinje images I, III, and IV near the center of the dilated right pupil. Like the AC/A data, recorded images were digitized by a frame grabber, and the separation between the center of each image in the pair was measured by Image Analyst version 8.1. This distance yields an equivalent mirror radius in air, which was then refracted through the optical elements preceding the reflecting surface, giving the radius of curvature in the eye (not reported in this article).

Partial Coherence Interferometry

Axial length was measured on the right eye only with the Zeiss-Humphrey IOLMaster (Carl Zeiss Meditec), which uses partial coherence interferometry (PCI).39,40 This is a noncontact technique, so no topical anesthetic is required. Three axial length readings were taken of the subject’s right eye.

Ultrasound

Anterior chamber depth, crystalline lens thickness, and axial length were measured on the right eye only using the Humphrey 820 (Carl Zeiss Meditec). Topical anesthesia with one drop of proparacaine was followed by five consecutive measurements of the subject’s right eye. Any scans that did not show sharp, clean spikes with lens and retinal echoes roughly equal in amplitude were deleted and the measurement repeated. The five values of anterior chamber depth, crystalline lens thickness, and axial length were printed out for data entry.

Data Entry and Quality Control

Questionnaires and examination forms were checked for completeness before the subject completed his or her study visit. Autorefraction printouts were checked for validity and number (sphere values within ± 5.00 D of mode; cylinder values within ± 1.00 D of mode). Data were double-entered into an Access database by the Optometry Coordinating Center (OCC) and then checked for entry errors. Edit reports identified missing or illegible data points for verification. The final dataset was exported for analysis in SAS 9.1.

Lens curvature data from videophakometry and eye position data from response AC/A ratio measurement were derived separately from image analysis by a video reader. These data were automatically saved into a text file by the image analysis software. The files were then reviewed for completeness and forwarded to the OCC for merging with the main dataset. Range checks were performed on these data to permit verification of irregular values.

Assessment of Daily Activities: The Experience Sampling Method

To assess near work-related risk factors for the progression of myopia, a random sampling technique known as the ESM was adopted.25,41–44 In the ESM, subjects carried a portable electronic pager and were paged randomly throughout the day. Originally, the method required that subjects record their activity in a diary or log book. We modified the technique by providing the subject with a cellular telephone. Each time they were paged, they dialed into an automated telephone survey system and reported their activity at that time.

Each subject’s daily activities were surveyed using the ESM twice a year for one week at a time. One week of sampling was scheduled immediately after the annual visit. The second week occurred midway between annual visits.

Each subject was paged eight times per day using an automated dialing system. The times at which a subject was paged were randomized by subject and by day but restricted to between 8:00 AM and 10:00 PM. For subjects who performed shift work or worked irregular hours, the automated dialing system was programmed so that they were paged during their waking hours. When paged, subjects were required to call the automated telephone survey immediately or as soon as possible. The number was preprogrammed into the cellular phone provided, although some participants opted to use an alternative phone. When they dialed the survey, they were prompted to verbally respond to five questions:

Please state the identification number on your beeper.

What were you doing when you were paged? Please be specific.

At what time did you begin this activity? Please state AM or PM.

Estimate the distance at which you were working in inches. If the distance was longer than 36 inches, please estimate the distance in feet.

Were you wearing glasses, contact lenses, both, or no correction during the activity?

At the baseline visit, subjects received initial instruction to familiarize them with the pagers and cellular phones. A cellular phone and pager were then issued to the subject for a week. To help subjects estimate distances, they were also provided with a pocket-sized tape measure.

Data from the voicemail messages were regularly transcribed into a subject log by study personnel and later entered into an Access database. Reported activities are assigned to one of 13 categories, e.g., reading, computer use, TV, and so on. Over the course of the study, each subject is surveyed a total of 560 times (5 years × 2 weeks × 7 days × eight pages).

Sample Size

Our primary question is whether a risk factor is associated with myopia progression in our sample. We have estimated the statistical power that our study design will provide to estimate the association between myopia progression and various candidate risk factors (e.g., proportion of time spent doing near work or response AC/A ratio).

All computations were performed using PASS software assuming an α = 0.05, two-sided test with one year of recruitment and 5 years of follow up. An acceptable minimum hazard ratio of 1.75 (i.e., a 75% increase in the risk of myopia progression for subjects in the high-risk group) is detectable with 80% power. Table 2 shows the hazard ratios that can be detected with the recruited sample and the effect of a range conservative estimates for the percent of subjects lost to follow up (up to 25%) and percent of subjects progressing during the 5-year follow up (up to 35%).13

TABLE 2.

Hazard ratios that can be detected with 0.80 statistical power for a range of progression rates (p) and loss to follow up in 396 subjects

| Loss to Follow Up |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p | 5 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 25 |

| 0.15 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.30 | 2.30 | 2.30 |

| 0.20 | 1.90 | 1.90 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 |

| 0.25 | 1.80 | 1.80 | 1.80 | 1.80 | 1.80 |

| 0.30 | 1.70 | 1.75 | 1.75 | 1.75 | 1.75 |

| 0.35 | 1.65 | 1.65 | 1.65 | 1.65 | 1.65 |

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics, e.g., mean ± standard deviation, were calculated for all variables. Analysis of variance was performed to examine the effect of various demographic variables on baseline refractive error. Post hoc testing was performed using the Tukey method of adjustment for multiple comparisons. Chi-squared testing was performed to determine the association between categorical variables. The association between ocular components and refractive error was assessed using linear regression.

At the study’s conclusion, modeling risk of myopia progression will be performed using time-to-event analysis, i.e., survival analysis.45 This technique uses maximum likelihood methods to model the time until first confirmed myopia progression as a function of various independent variables (risk factors, explanatory variables).

RESULTS

Of the original 3690 potentially eligible subjects, 2241 responded to the recruitment letter or subsequent attempts at contact. The majority reported that they were ineligible or declined participation. Four hundred ninety-seven subjects attended for a baseline examination, but 101 were ineligible. The reasons for their exclusion were myopia exceeding −7.75 D (n = 39), hyperopic or myopia too low (n = 47), strabismus (n = 6), poor visual acuity (n = 3), small pupils making autorefraction not possible (n = 1), or some combination of these reasons (n = 5).

A total of 396 subjects were enrolled in the study and completed the baseline examination. Of these, 41 were enrolled as part of a pilot study of subjects aged between 30 and 35 years of age that began 2 years previously but have been followed on the same schedule. All had undergone the same baseline examination with the exception of axial length measurement with the IOLMaster. In addition, these pilot study subjects did not participate in the ESM during their first year. Thus, the ESM results reported here do not include data from these subjects.

The mean (± standard deviation [SD]) age of the 396 enrolled subjects was 30.5 ± 3.4 years (range, 25–36 years). A few subjects reached their 36th birthday between being recruited and attending for their baseline visit, but they were still enrolled. The demographics of the cohort are summarized in Table 3. Of the 396 subjects, 66% were female, 80% were white, 11% were black, and 8% were Asian/Pacific Islander. As might be anticipated for a university-based population, the sample was well educated with 82% having at least a college degree. Most subjects reported a family history of myopia with 78% having at least one myopic parent and 60% having at least one sibling with myopia. At baseline, 233 subjects (59%) were wearing contact lenses: 216 wore soft lenses and 17 wore rigid gas-permeable (RGP) lenses. Most of these subjects (82%) reported wearing their contact lenses at least 7 hours a day (178 of 216 soft lens wearers = 82% and 13 of 17 RGP lens wearers = 76%), although 12 subjects (5%) reported wearing their contact lenses on average less than 1 hour a day. Sixty-eight subjects (17%) reported that they did not wear a correction when reading.

TABLE 3.

Demographic characteristics of SPAN subjects

| Characteristics | N | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 263 | 66 |

| Male | 133 | 34 |

| Race | ||

| White | 316 | 80 |

| Black | 42 | 11 |

| Asian | 30 | 8 |

| Hispanic | 2 | 1 |

| Other or unspecified | 6 | 2 |

| Education | ||

| Less than high school | 0 | 0 |

| High school education or GED | 4 | 1 |

| Some college | 70 | 18 |

| College degree | 137 | 35 |

| Some graduate education | 185 | 47 |

| Family history | ||

| Two myopic parents | 134 | 36 |

| One myopic parent | 159 | 42 |

| No myopic parents | 83 | 22 |

| At least one myopic sibling | 227 | 60 |

| Age began wearing spectacles | 13.8 ± 5.5 | |

| Ever worn contact lenses | 305 | 77 |

| Age began wearing contact lenses | 18.1 ± 5.6 | |

| Currently wearing contact lenses | ||

| No | 163 | 41 |

| Soft | 216 | 55 |

| Wearing time | 12.2 ± 5.6 | 82>7 hours/day |

| Rigid gas permeable | 17 | 4 |

| Wearing time | 11.1 ± 6.5 | 76>7 hours/day |

| Correction not worn to read (n = 389) | 68 | 17 |

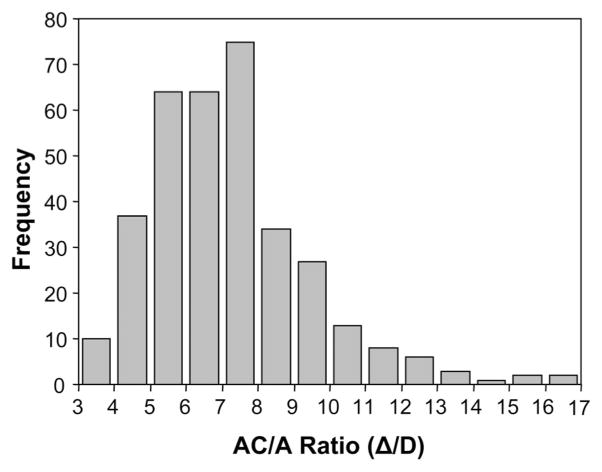

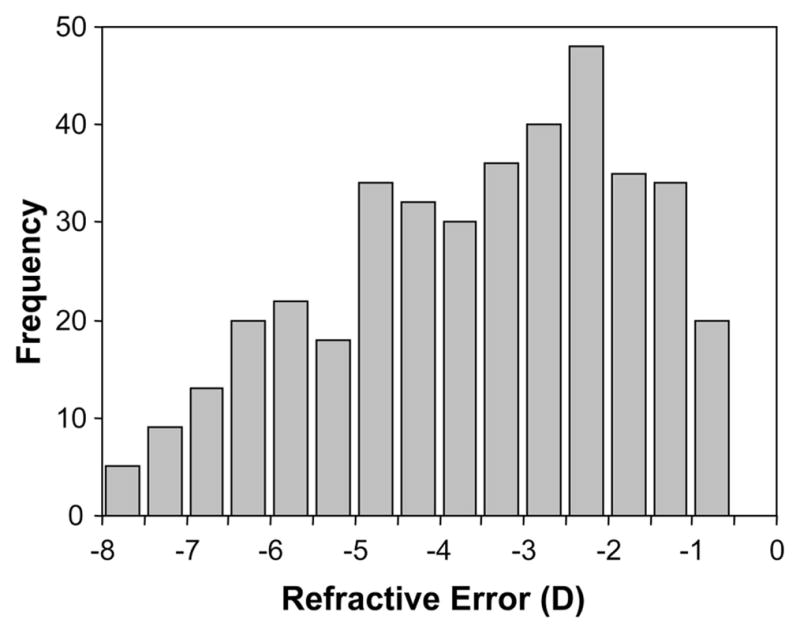

The mean (± SD) for refractive error, ocular components, and accommodative and vergence measures are shown in Table 4. The mean refractive error (spherical equivalent) of the subjects was −3.54 ± 1.77 D with 0.53 ± 0.51 D of astigmatism. The distribution of refractive error is shown in Figure 1. The mean axial length as measured with the IOLMaster was 24.6 ± 1.1 mm (n =355). The distribution of axial length is shown in Figure 2. Axial length values measured by ultrasound were shorter than those obtained with the IOLMaster (Table 4). Among those subjects with both IOLMaster and ultrasound data, the mean difference was 0.19 ± 0.23 mm (paired t = 15.23; p < 0.001).

TABLE 4.

Biometric and accommodative characteristics of SPAN subjects (n = 396 unless specified)

| Clinical measure | Mean ± standard deviation |

|---|---|

| Refractive error (D) | |

| Spherical equivalent | −3.54 ± 1.77 |

| Astigmatism | 0.53 ± 0.51 |

| Axial length (mm) | |

| Ultrasound | 24.46 ± 1.05 |

| IOLMaster (n = 355) | 24.62 ± 1.06 |

| Anterior chamber depth (mm) | 3.64 ± 0.29 |

| Lens thickness (mm) | 3.74 ± 0.21 |

| Corneal power (D) | +44.34 ± 1.47 |

| Near phoria (Δ, − = exo) | −1.73 ± 3.99 |

| Accommodative response (D) | |

| 2-D stimulus | 1.61 ± 0.36 |

| 4-D stimulus | 3.46 ± 0.56 |

| AC/A ratio (Δ/D, n = 346) | 7.22 ± 2.24 |

FIGURE 1.

The distribution of refractive error (spherical equivalent in D) in SPAN subjects (n = 396).

FIGURE 2.

The distribution of axial length (mm) measured with the IOLMaster in SPAN subjects (n = 355).

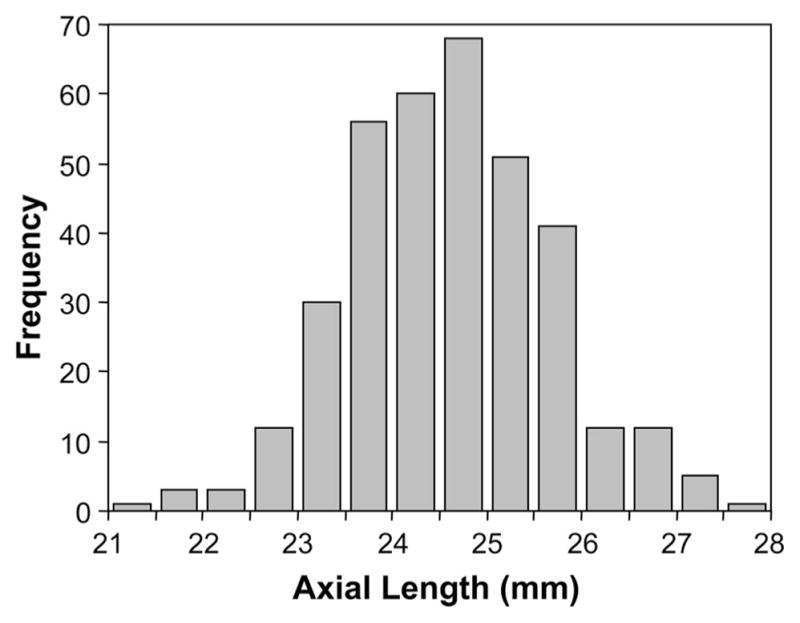

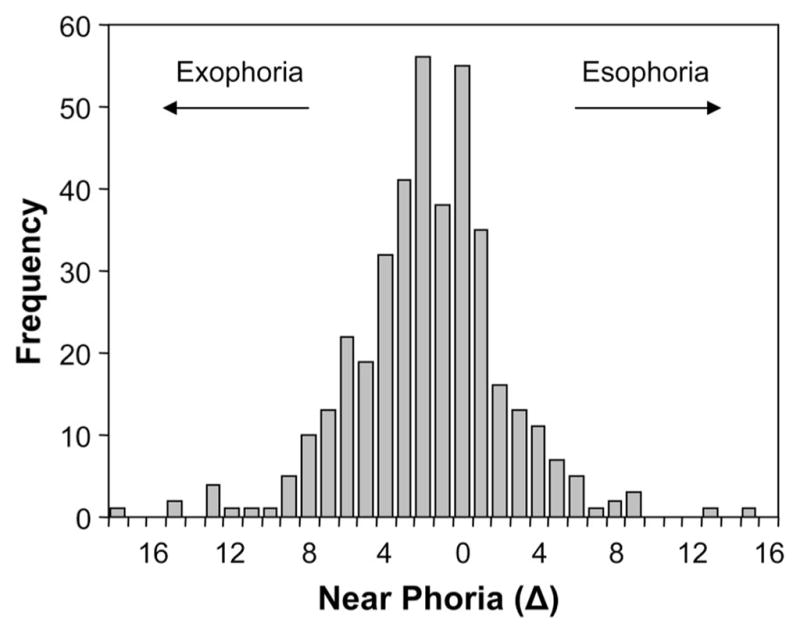

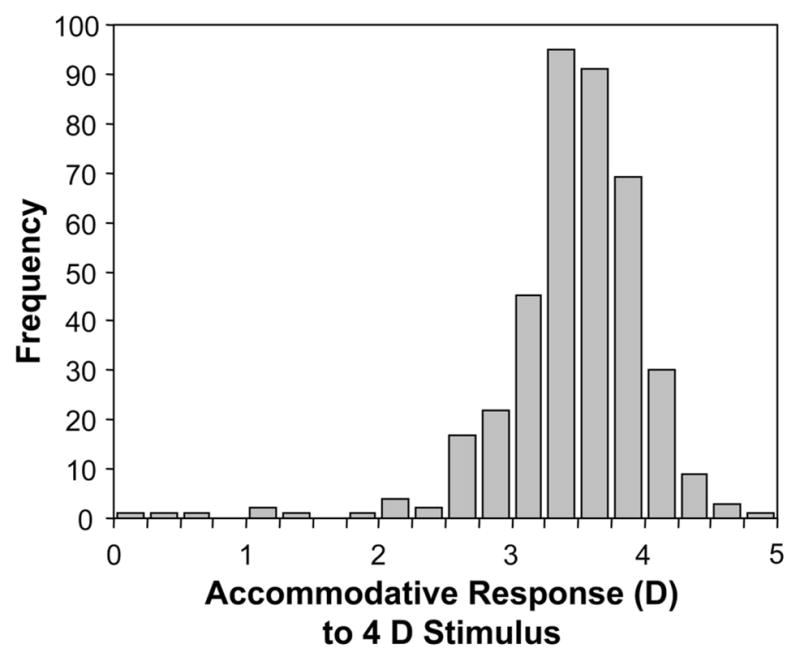

On average, subjects were exophoric (mean phoria = 1.7 ± 4.0 Δ), although 95 (24.0%) were esophoric. The distribution of near phoria is shown in Figure 3. The mean accommodative response was 1.61 ± 0.36 D and 3.46 ± 0.56 D for the 2- and 4-D stimuli, respectively (no adjustment has been made for the effectivity of correcting lenses). The distribution of accommodative responses for the 4-D stimulus is shown in Figure 4. Fifty-two (13.2%) subjects have an accommodative response of <3 D for the 4-D stimulus. AC/A data were available on only 346 subjects as a result of problems with the videotapes. The mean AC/A ratio was 7.22 ± 2.24 Δ/D. It should be noted that this is a response AC/A ratio and thus higher than the more commonly measured stimulus AC/A ratio. The distribution of AC/A ratios is shown in Figure 5. Thirty-five subjects (10.1%) have an AC/A ratio >10 Δ/D.

FIGURE 3.

The distribution of near phoria (Δ) in SPAN subjects (n = 396).

FIGURE 4.

The distribution of accommodative response (D) to the 4-D stimulus in SPAN subjects (n = 395).

FIGURE 5.

The distribution of AC/A ratio (Δ/D) in SPAN subjects (n = 346).

The effect of the demographic variables (Table 3) on refractive error was examined. Gender, race, education, and age at baseline were not related to refractive error. The effect of family history on the degree of myopia is shown in Table 5. Refractive error was associated with the number of myopic parents (F = 3.83, p = 0.023) with subjects reporting two myopic parents more myopic than those reporting no myopic parents (−3.81 ± 1.78 vs. −3.14 ± 1.74 D, p = 0.019). Furthermore, subjects reporting a myopic mother were more myopic than those reporting a nonmyopic mother (−3.76 ± 1.77 vs. −3.33 ± 1.73 D, F = 5.55, p = 0.019), but the reported refractive status of the subject’s father had no significant effect (F = 2.56, p = 0.11). There was also a significant effect of sibling myopia on refractive error with subjects reporting at least one myopic sibling more myopic than those reporting none (−3.74 ± 1.77 vs. −3.36 ± 1.74 D, F = 4.22, p = 0.041).

TABLE 5.

Mean (± standard deviation) refractive error as a function of reported parental and sibling myopia

| Family history | n | Mean ± standard deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Number of myopic parents | ||

| Two | 134 | −3.81 ± 1.78 |

| One | 159 | −3.64 ± 1.74 |

| Zero | 83 | −3.14 ± 1.74 |

| Mother myopic? | ||

| Yes | 225 | −3.76 ± 1.77 |

| No | 152 | −3.33 ± 1.73 |

| Father myopic? | ||

| Yes | 202 | −3.73 ± 1.75 |

| No | 174 | −3.43 ± 1.77 |

| Any myopic siblings? | ||

| Yes | 227 | −3.74 ± 1.77 |

| No | 150 | −3.36 ± 1.74 |

The age at which subjects began wearing spectacles—a surrogate for age of myopia onset—was associated with the amount of myopia (r = 0.509, p < 0.001; slope = 0.16 D/year). Previous studies have categorized myopes as early or late onset, typically using a criterion of 15 years as the cut point.46,47 Dividing the current cohort into early and late onset revealed that the early-onset myopes had significantly higher levels of myopia (n = 248; mean = −4.23 ± 1.71 D) than late-onset myopes (n = 147; mean = −2.40 ± 1.18 D). Given that both age of onset and parental history were significantly related to degree of myopia, we evaluated the relation between number of myopic parents and onset of myopia. Table 6 shows the number and proportion of both early- and late-onset myopes who reported zero, one, or two myopic parents. The number of myopic parents was significantly higher in the early-onset myopes than in late-onset myopes (χ2 = 13.78, p = 0.001). Early-onset myopes also reported significantly more myopic mothers (χ2 = 8.65, p = 0.003) and myopic fathers (χ2 = 6.53, p = 0.011), but age of onset was not related to reported sibling myopia (χ2 = 0.83, p = 0.36).

TABLE 6.

The relation between myopia onset (early = before 15 years, late = after 15 years) and reported parental history of myopia

| Number of myopic parents |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| Early onset (n = 241a) | |||

| n | 40 | 104 | 97 |

| Percent | 16.6 | 43.1 | 40.2 |

| Late onset (n = 134a) | |||

| n | 43 | 55 | 36 |

| Percent | 32.1 | 41.0 | 26.9 |

Not all subjects reported parental refractive status.

When both onset of myopia and the number of myopic parents were considered in a multivariate analysis, onset of myopia (early vs. late) still had a significant effect on degree of myopia (F = 115.1, p < 0.001), but the number of myopic parents was no longer significant (F = 0.65, p = 0.52).

Contact lens wearers were more myopic than nonwearers (F = 17.3, p < 0.001). RGP lens wearers (−4.59 ± 1.79 D) and soft lens wearers (−3.90 ±1.69 D) were more myopic (p < 0.001) than nonwearers (−2.96 ± 1.71 D) but not different from each other. This effect was maintained if individuals who wore their contact lenses less than 1 hour a day were considered as nonwearers (F = 21.6, p < 0.001).

As would be expected, greater axial lengths were associated with higher levels of myopia (r = −0.532, p < 0.001). Increased anterior chamber depth (r = −0.134, p = 0.008) and corneal power (r = −0.104, p = 0.044) were also both associated with increased myopia, but lens thickness was not (p = 0.07).

Experience Sampling Method Assessment of Near Work

The mean subject response rate for the first week of ESM was 90.1% (median, 96.4%; range, 7.1–100%). Fifty-three of the subjects (34.4%) responded to all 56 pages and 257 (73%) responded to at least 90% of pages. Three subjects (0.8%) declined to participate in ESM. Table 7 lists the task categories and the mean proportion with which each was reported by subjects. The most frequently reported visual task was computer use (mean, 18.9%; range, 0–60.0%). On average, subjects reported reading 10.3% of the time (range, 0–42.9%). Other common tasks included distance tasks such as driving (14.2%), in conversation (11.6%), and watching TV (10.2%). The reading, computer use, and near miscellaneous categories were combined to represent each subject’s total near activity. Overall, subjects reported near work activity 34.1 ± 11.6% of the time (range, 0–67.3%).

TABLE 7.

Summary of SPAN subjects’ responses during the first week of the experience sampling method

| Activity | Mean (%) | Minimum (%) | Maximum (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reading | 10.3 | 0 | 42.9 |

| Using computer | 18.9 | 0 | 60.0 |

| Near misc. task | 4.8 | 0 | 30.4 |

| In conversation | 11.6 | 0 | 52.2 |

| On phone | 2.1 | 0 | 14.5 |

| Shopping | 1.7 | 0 | 7.8 |

| Watching TV | 10.2 | 0 | 41.1 |

| Exercising | 1.1 | 0 | 14.3 |

| Household tasks | 7.1 | 0 | 27.5 |

| Eating | 3.6 | 0 | 19.2 |

| Grooming | 2.6 | 0 | 16.7 |

| Miscellaneous intermediate tasks | 2.0 | 0 | 21.4 |

| Combination near and distance tasks | 4.6 | 0 | 30.9 |

| Distance tasks | 14.2 | 0 | 50.0 |

| Sleeping | 5.4 | 0 | 38.6 |

DISCUSSION

This article presents the baseline findings from the SPAN. In comparing our results with previous studies, it is important to remember that all of the subjects in SPAN are myopes and the analyses use refractive error (degree of myopia) rather than the presence or absence of myopia. This is particularly germane when considering the impact of family history on the refractive status of the SPAN cohort. It is not surprising that so many subjects report myopic parents and siblings,48,49 but it is surprising that myopia in a parent, particularly the subject’s mother, is related to the degree of myopia. Although the degree of myopia is not significantly associated with the reported refractive status of the subject’s father, there is a trend for higher levels in those with a myopic father (Table 5).

As reported by previous researchers, the degree of myopia is related to the age of onset.7,47 In the SPAN cohort, each 1-year increase in the age at which the subject began wearing spectacles is associated with −0.16 D less myopia and early-onset myopes are significantly more myopic than late-onset myopes. Further analysis demonstrates that that the number of myopic parents is significantly related to the age of myopia onset. For example, twice as many late-onset myopes (32.1%) report no parental history of myopia as early-onset myopes (16.6%). Given that both age of onset and parental history are significantly related to the degree of myopia in our cohort, we performed a multivariate analysis to simultaneously assess the affect of these variables. In the multivariate model, age of onset (early vs. late) was significant related to degree of myopia, but parental history was no longer significant. Thus, any impact of parental refractive error on the level of myopia is mediated by the age of onset of myopia. In other words, those subjects with myopic parents have higher levels of myopia because they developed myopia at an earlier age.

The degree of myopia is higher among contact lens wearers than nonwearers, but this is probably the result of the cosmetic and functional limitations of higher-powered spectacle lenses or having spent more years as a myope and thus having greater opportunity to begin contact lens wear. As would be expected, degree of myopia was associated with increased axial length. Although less compelling, the association with anterior chamber depth and corneal power has been reported previously.50

The response rate for the ESM was impressive and bodes well for the characterization of near activity in the cohort. On average, subjects spend approximately one-third of their time engaged in near activity (34.1%) with computer use contributing just over half of the activity (18.9%). Despite the cohort having been recruited from university faculty and staff, the range of near activity is quite broad (0–67.3%).

Risk Factors for Progression

The goal of SPAN is to determine the risk factors associated with adult myopia progression. The primary risk factors to be evaluated are performing near work for a greater proportion of the day, performing near tasks at a close distance, a high response AC/A ratio, and a high accommodative lag. The first two near work-related risk factors were chosen based on the longstanding, but largely unsubstantiated, assertion that adult myopia progression is associated with high levels of near activity. Of the previous studies listed in Table 1, few examined near work as a potential risk factor for adult myopia progression,10,12,13 and only Kinge et al.12 reported an association between near work and myopia progression (r = 0.25). Reading at a closer distance has been proposed as a potential risk factor in children.51,52 An informal survey at the Eighth International Conference on Myopia in 2000 found that 31 of 47 of meeting presenters (66%) felt that environmental factors were primarily responsible for adult myopia progression, and an additional nine (19%) felt that the progression was the result of an interaction between environmental and genetic factors.

The hypothesis that increased accommodative lag is a risk factor for myopia progression is supported by both animal myopia research and accommodative studies in humans. The neonatal animal eye can compensate for refractive errors induced by convex or concave lenses. A minus lens placed in front of the cornea shifts the focal plane posteriorly. In an emmetropic eye, this results in hyperopic defocus unless the eye accommodates. In young chicks,53 tree shrews,54 and monkeys,55 the eye compensates over a period of days or weeks by increasing its axial growth rate until the retina has shifted to this modified focal plane. A recent report suggests that the mechanism may still be active in adolescent monkeys.56

In humans, underaccommodation to a near target—accommodative lag—results in hyperopic defocus similar to that produced by a minus lens in the animal studies. A number of researchers have hypothesized that this accommodative lag induces myopia in humans by a mechanism similar to that which produces experimental myopia in animals.15–17,57 Studies in children and adults reported greater accommodative lag in myopes compared with emmetropes.15,46,47 Subsequent studies have shown that accommodative lag is greater in children20 and adults21 whose myopia is increasing compared with subjects whose myopia is stable.

Studies have also linked the interaction between accommodation and convergence to the etiology of myopia. This interaction is usually characterized by the AC/A ratio, measured as the change in convergence (or phoria) induced by a change in accommodation. Cross-sectional studies in children24,58 and adults17,23 found that higher AC/A ratios were associated with myopia. Of particular interest is a small prospective study that found that adults whose myopia developed or progressed over a 2- to 3-year period had significantly higher response AC/A ratios than those whose refractive error was stable.17 Likewise, it has been reported that a high response AC/A ratio is a significant risk factor for the onset of myopia in children.24,59

The ability of SPAN to successfully identify significant risk factors depends in part on there being a broad distribution of the relevant variables in the study population. In this regard, it is important to note that there is a broad range in the proportion of near activity undertaken by the subjects (Table 7). Likewise, other primary risk factors—accommodative lag and AC/A ratio—along with secondary factors like phoria show similar broad distributions. A detailed analysis of the ESM data is the subject of a future manuscript.

Public Health Significance

Myopic progression in adults is of increasing clinical interest as increasing numbers of patients undergo refractive surgery, e.g., LASIK, to correct their myopia. Adult myopic changes affect the long-term patient satisfaction with such procedures. For example, a 25 year old who is rendered emmetropic by LASIK, but whose myopia then progresses by a diopter over the next decade, will evolve into a 35-year-old –1.00-D myope (although such a refractive error may be desirable in a presbyope). Javitt and Chiang analyzed the cost-effectiveness of excimer laser photorefractive keratectomy and concluded that over a 20-year period, it was a less expensive investment than either daily wear or extended-wear soft contact lenses.60 Their analyses were based, however, on the premise that there were no long-term refractive changes in the postsurgery patient and that the vast majority of patients remained “glasses-free.” If patients shift in a myopic direction, then clearly refractive surgery may be a less cost-effective alternative than proposed by Javitt and Chiang.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH/NEI R01-EY012952 and R24-EY014792.

References

- 1.Grosvenor T. A review and a suggested classification system for myopia on the basis of age-related prevalence and age of onset. Am J Optom Physiol Opt. 1987;64:545–54. doi: 10.1097/00006324-198707000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goss DA, Winkler RL. Progression of myopia in youth: age of cessation. Am J Optom Physiol Opt. 1983;60:651–8. doi: 10.1097/00006324-198308000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Research Council (U.S.) Myopia: Prevalence and Progression. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1989. Working Group on Myopia Prevalence and Progression. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zadnik K, Mutti DO. Refractive error changes in law students. Am J Optom Physiol Opt. 1987;64:558–61. doi: 10.1097/00006324-198707000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Neal MR, Connon TR. Refractive error change at the United States Air Force Academy—class of 1985. Am J Optom Physiol Opt. 1987;64:344–54. doi: 10.1097/00006324-198705000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adams DW, McBrien NA. Prevalence of myopia and myopic progression in a population of clinical microscopists. Optom Vis Sci. 1992;69:467–73. doi: 10.1097/00006324-199206000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grosvenor T, Scott R. Three-year changes in refraction and its components in youth-onset and early adult-onset myopia. Optom Vis Sci. 1993;70:677–83. doi: 10.1097/00006324-199308000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waring GO, 3rd, Lynn MJ, McDonnell PJ. Results of the prospective evaluation of radial keratotomy (PERK) study 10 years after surgery. Arch Ophthalmol. 1994;112:1298–308. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1994.01090220048022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ellingsen KL, Nizam A, Ellingsen BA, Lynn MJ. Age-related refractive shifts in simple myopia. J Refract Surg. 1997;13:223–8. doi: 10.3928/1081-597X-19970501-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McBrien NA, Adams DW. A longitudinal investigation of adult-onset and adult-progression of myopia in an occupational group. Refractive and biometric findings. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1997;38:321–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kinge B, Midelfart A, Jacobsen G. Refractive errors among young adults and university students in Norway. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 1998;76:692–5. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.1998.760612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kinge B, Midelfart A, Jacobsen G, Rystad J. The influence of near-work on development of myopia among university students. A three-year longitudinal study among engineering students in Norway. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2000;78:26–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.2000.078001026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bullimore MA, Jones LA, Moeschberger ML, Zadnik K, Payor RE. A retrospective study of myopia progression in adult contact lens wearers. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:2110–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adams AJ. Axial length elongation, not corneal curvature, as a basis of adult onset myopia. Am J Optom Physiol Opt. 1987;64:150–2. doi: 10.1097/00006324-198702000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gwiazda J, Thorn F, Bauer J, Held R. Myopic children show insufficient accommodative response to blur. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1993;34:690–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goss DA, Wickham MG. Retinal-image mediated ocular growth as a mechanism for juvenile onset myopia and for emmetropization. A literature review. Doc Ophthalmol. 1995;90:341–75. doi: 10.1007/BF01268122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang BC. Parameters of accommodative and vergence systems and the development of late-onset myopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995;36:1737–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flitcroft DI. A model of the contribution of oculomotor and optical factors to emmetropization and myopia. Vision Res. 1998;38:2869–79. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(98)00087-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bullimore MA, Gilmartin B. The accommodative response, refractive error and mental effort: 1. The sympathetic nervous system. Doc Ophthalmol. 1988;69:385–97. doi: 10.1007/BF00162751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gwiazda J, Bauer J, Thorn F, Held R. A dynamic relationship between myopia and blur-driven accommodation in school-aged children. Vision Res. 1995;35:1299–304. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(94)00238-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abbott ML, Schmid KL, Strang NC. Differences in the accommodation stimulus response curves of adult myopes and emmetropes. Ophthal Physiol Opt. 1998;18:13–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gwiazda J, Grice K, Thorn F. Response AC/A ratios are elevated in myopic children. Ophthal Physiol Opt. 1999;19:173–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1475-1313.1999.00437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenfield M, Gilmartin B. Effect of a near-vision task on the response AC/A of a myopic population. Ophthal Physiol Opt. 1987;7:225–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mutti DO, Jones LA, Moeschberger ML, Zadnik K. AC/A ratio, age, and refractive error in children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:2469–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rah MJ, Mitchell GL, Bullimore MA, Mutti DO, Zadnik K. Prospective quantification of near work using the experience sampling method. Optom Vis Sci. 2001;78:496–502. doi: 10.1097/00006324-200107000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bullimore MA, Fusaro RE, Adams CW. The repeatability of automated and clinician refraction. Optom Vis Sci. 1998;75:617–22. doi: 10.1097/00006324-199808000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zadnik K, Mutti DO, Adams AJ. The repeatability of measurement of the ocular components. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1992;33:2325–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ong E, Ciuffreda KJ. Nearwork-induced transient myopia: a critical review. Doc Ophthalmol. 1995;91:57–85. doi: 10.1007/BF01204624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Atchison DA, Smith G, Efron N. The effect of pupil size on visual acuity in uncorrected and corrected myopia. Am J Optom Physiol Opt. 1979;56:315–23. doi: 10.1097/00006324-197905000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bailey IL, Lovie JE. New design principles for visual acuity letter charts. Am J Optom Physiol Opt. 1976;53:740–5. doi: 10.1097/00006324-197611000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gordon MO, Schechtman KB, Davis LJ, McMahon TT, Schornack J, Zadnik K Collaborative Longitudinal Evaluation of Keratoconus (CLEK) Study Group. Visual acuity repeatability in keratoconus: impact on sample size. Optom Vis Sci. 1998;75:249–57. doi: 10.1097/00006324-199804000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cornsweet TN, Crane HD. Accurate two-dimensional eye tracker using first and fourth Purkinje images. J Opt Soc Am. 1973;63:921–8. doi: 10.1364/josa.63.000921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barry JC, Effert R, Reim M, Meyer-Ebrecht D. Computational principles in Purkinje I and IV reflection pattern evaluation for the assessment of ocular alignment. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1994;35:4205–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin LL, Shih YF, Hsiao CH, Su TC, Chen CJ, Hung PT. The cycloplegic effects of cyclopentolate and tropicamide on myopic children. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 1998;14:331–5. doi: 10.1089/jop.1998.14.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Egashira SM, Kish LL, Twelker JD, Mutti DO, Zadnik K, Adams AJ. Comparison of cyclopentolate versus tropicamide cycloplegia in children. Optom Vis Sci. 1993;70:1019–26. doi: 10.1097/00006324-199312000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thibos LN, Wheeler W, Horner D. Power vectors: an application of Fourier analysis to the description and statistical analysis of refractive error. Optom Vis Sci. 1997;74:367–75. doi: 10.1097/00006324-199706000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mutti DO, Zadnik K, Adams AJ. A video technique for phakometry of the human crystalline lens. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1992;33:1771–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mutti DO, Zadnik K, Adams AJ. The equivalent refractive index of the crystalline lens in childhood. Vision Res. 1995;35:1565–73. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(94)00262-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Drexler W, Findl O, Menapace R, Rainer G, Vass C, Hitzenberger CK, Fercher AF. Partial coherence interferometry: a novel approach to biometry in cataract surgery. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998;126:524–34. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(98)00113-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sheng H, Bottjer CA, Bullimore MA. Ocular component measurement using the Zeiss IOLMaster. Optom Vis Sci. 2004;81:27–34. doi: 10.1097/00006324-200401000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moneta GB, Csikszentmihalyi M. The effect of perceived challenges and skills on the quality of subjective experience. J Pers. 1996;64:275–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1996.tb00512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hnatiuk SH. Experience sampling with elderly persons: an exploration of the method. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 1991;33:45–64. doi: 10.2190/541V-1036-8VFK-J0MU. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hillbrand M, Waite BM. The everyday experience of an institutionalized sex offender: an idiographic application of the experience sampling method. Arch Sex Behav. 1994;23:453–63. doi: 10.1007/BF01541409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Csikszentmihalyi M, LeFevre J. Optimal experience in work and leisure. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989;56:815–22. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.56.5.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Klein JP, Moeschberger ML. Survival Analysis: Techniques for Censored and Truncated Data. New York: Springer; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 46.McBrien NA, Millodot M. The effect of refractive error on the accommodative response gradient. Ophthal Physiol Opt. 1986;6:145–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bullimore MA, Gilmartin B, Royston JM. Steady-state accommodation and ocular biometry in late-onset myopia. Doc Ophthalmol. 1992;80:143–55. doi: 10.1007/BF00161240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mutti DO, Mitchell GL, Moeschberger ML, Jones LA, Zadnik K. Parental myopia, near work, school achievement, and children’s refractive error. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:3633–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Morgan I, Rose K. How genetic is school myopia? Prog Retin Eye Res. 2005;24:1–38. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grosvenor T, Scott R. Comparison of refractive components in youth-onset and early adult-onset myopia. Optom Vis Sci. 1991;68:204–9. doi: 10.1097/00006324-199103000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Haro C, Poulain I, Drobe B. Investigation of working distance in myopic and non-myopic children. Optom Vis Sci. 2000;77(suppl):189. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gwiazda JE, Hyman L, Norton TT, Hussein ME, Marsh-Tootle W, Manny R, Wang Y, Everett D. Accommodation and related risk factors associated with myopia progression and their interaction with treatment in COMET children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:2143–51. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schaeffel F, Glasser A, Howland HC. Accommodation, refractive error and eye growth in chickens. Vision Res. 1988;28:639–57. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(88)90113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Siegwart JT, Jr, Norton TT. Regulation of the mechanical properties of tree shrew sclera by the visual environment. Vision Res. 1999;39:387–407. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(98)00150-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hung LF, Crawford ML, Smith EL., 3rd Spectacle lenses alter eye growth and the refractive status of young monkeys. Nat Med. 1995;1:761–5. doi: 10.1038/nm0895-761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhong X, Ge J, Nie H, Smith EL., 3rd Compensation for experimentally induced hyperopic anisometropia in adolescent monkeys. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:3373–9. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Flitcroft DI. The lens paradigm in experimental myopia: oculomotor, optical and neurophysiological considerations. Ophthal Physiol Opt. 1999;19:103–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1475-1313.1999.00432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gwiazda J, Grice K, Thorn F. Response AC/A ratios are elevated in myopic children. Ophthal Physiol Opt. 1999;19:173–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1475-1313.1999.00437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gwiazda J, Thorn F, Held R. Accommodation, accommodative convergence, and response AC/A ratios before and at the onset of myopia in children. Optom Vis Sci. 2005;82:273–8. doi: 10.1097/01.opx.0000159363.07082.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Javitt JC, Chiang YP. The socioeconomic aspects of laser refractive surgery. Arch Ophthalmol. 1994;112:1526–30. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1994.01090240032022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]