Abstract

Widespread cooperation between domain experts and front-line clinicians is a key component of any successful clinical knowledge management framework. Peer review is an established form of cooperation that promotes the dissemination of new knowledge. The authors describe three peer collaboration scenarios that have been implemented using the knowledge management infrastructure available at Intermountain Healthcare. Utilization results illustrating the early adoption patterns of the proposed scenarios are presented and discussed, along with succinct descriptions of planned enhancements and future implementation efforts.

Introduction

Healthcare has long been described as an “information-based” industry [1], making knowledge management an activity of recognized importance for any successful healthcare organization [2–4]. Recently, knowledge management within healthcare organizations has shifted its focus from traditional practices to innovative and specialized efforts that enable and promote computerized decision support to clinicians [5,6].

The continuous improvement of any clinical knowledge management framework depends on successful strategies for promoting cooperation between knowledge authors (e.g., domain experts) and knowledge users (e.g., front-line clinicians) [7]. Effective frameworks help to induce and sustain cooperation, while supporting extensive “fingerprinting” in an effort to promote shared ownership of knowledge assets [8].

An established form of cooperation is peer review. Peer review is a recognized process for “certifying” new knowledge and its basic principles promote active and open collaboration between authors and reviewers [9]. Peer review is also an excellent strategy for initiating the dissemination of new knowledge [10].

Background

Intermountain Healthcare (Intermountain) is a not-for-profit integrated delivery system of 21 hospitals, over 70 outpatient clinics, an employed physician group with over 500 physicians, and an insurance plan located in Utah and southeastern Idaho. Intermountain facilities range from major tertiary-level teaching and research facilities to small hospitals and clinics in rural communities.

Since 2001, Intermountain has been developing and implementing a new clinical knowledge management infrastructure. This infrastructure includes multiple software components designed to support the complete lifecycle of knowledge assets. The three core components include a centralized store, a flexible knowledge editor, and a generic search and browsing tool.

The centralized store is known as the “Clinical Knowledge Repository” (CKR). The CKR includes a database that stores both interactive and reference knowledge assets produced by teams of clinical experts [11–15]. The preferred asset representation and storage format is XML, but other document formats are also supported (e.g., text, PDF, MS Word, JPEG). The CKR also offers an extensive set of read and write services, most of which can be easily accessed via HTTP. Using these services, clinical information systems and intranet applications can search and retrieve knowledge assets. Clinical systems tightly integrated to the CKR can also create and update XML-based assets.

Every knowledge asset stored in the CKR receives a unique numeric identifier and is associated with a rich set of metadata. The numeric identifier remains the same during the entire lifecycle of the asset. A sequential version number identifies each new edition of the same asset. Each asset represents an instance of a specific category and can be a member of one or many collections. A category represents the intended clinical purpose of the asset (e.g., patient education handout, nursing protocol, medication monograph).

In the case of XML-based assets, the category also defines the underlying schema. Collections identify arbitrary logical sets of assets used primarily to facilitate clinician searching and navigation (e.g., clinical practice guidelines, clinical forms, emergency services). Knowledge engineers are responsible for the definition and implementation of asset categories and collections [16].

The content editor is called “Knowledge Authoring Tool” (KAT) [17]. KAT is a web-based knowledge editor that allows knowledge authors to create and update XML-based assets. KAT can be configured to create practically any type of XML document, which provides excellent infrastructure flexibility and substantial autonomy to knowledge engineers.

Finally, the generic search and browsing component is the “Knowledge Repository Online” (KRO) [18]. KRO is a web-based application that allows clinicians and intranet users to search and retrieve any CKR asset, irrespective of category or collection. KRO was designed primarily to enable an open and distributed review process.

Peer Review Strategies

The peer review strategies currently implemented in the CKM infrastructure are based on three interrelated scenarios. Each scenario explores a specific step of the knowledge asset lifecycle, in an effort to maximize the ubiquity of peer review and promote widespread collaboration.

The first scenario explores a more traditional peer review process where reviewers with recognized expertise are asked to critique and validate a newly published knowledge asset. However, given our intent to promote extensive “fingerprinting” of knowledge assets, the current implementation of this first scenario is not limited to assigned reviewers. Instead, it is implemented as an open review process that enables any clinician within Intermountain to critique a knowledge asset, even before it is made available for clinical use. It is important to recognize that in this scenario assigned reviewers receive a communication that explains their assignment, while volunteer reviewers have to search for the assets that they are interested in reviewing.

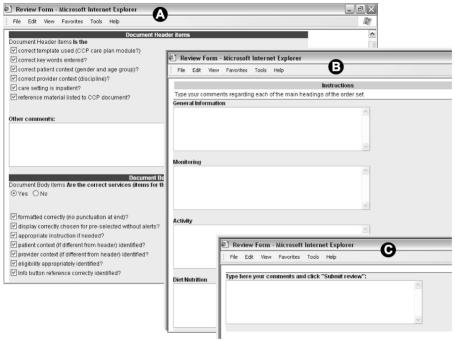

Using KRO, once the desired asset has been identified, the reviewer can select the “review” function and provide feedback using a pre-defined review form (Figure 1). The intent of a review form is to guide the reviewer in providing pertinent information to the author. Authors and knowledge engineers have the opportunity to create very specific review forms for any given asset category (Figure 2). Review forms also normally include text areas that allow reviewers to provide additional feedback that is not elicited by the specific questions.

Figure 1.

KRO search results screen, demonstrating the options to create a review (“A”), to read existing reviews (“B”), and to view the metadata (“C”).

Figure 2.

Examples of review forms created for different asset categories and/or collections: structured form with default answers (“A”), semi-structured form with only headers (“B”), and simple form with a single generic text area (“C”).

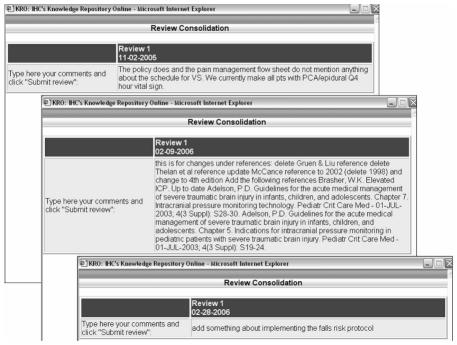

The submitted reviews are stored in the CKR with a direct association with the specific version of the knowledge asset they pertain to. Any KRO user can read these reviews, but in order to promote an open process and prevent review biases, the identity of the reviewers is not disclosed (Figure 3). Every review submitted triggers an email notification to the author of the knowledge asset. The authors know the identity of the reviewers, enabling direct contact to obtain clarifications about the feedback received.

Figure 3.

Examples of reviews created for different knowledge assets. Notice that the identity of the reviewer is not displayed (“Reviewer 1”).

The second scenario explores the opportunity of obtaining highly pertinent feedback when clinicians are interacting with a knowledge asset while using Intermountain’s clinical information systems, or other intranet sites and applications. In this scenario, clinicians may be motivated to provide feedback when they have identified some deficiency on a knowledge asset. It is important to recognize that in this scenario clinicians are again volunteer reviewers.

In an effort to implement a non-intrusive access point to a review form, a user interface artifact known as the “knowledge-button” (K-button) was implemented (Figure 4). The clinician simply clicks at the K-button and a new window appears with the appropriate review form within KRO. If the user has never used KRO before, a simple user profile form will be displayed first, requesting items like clinical discipline and specialty, as well as email and contact phone numbers. After submitting the feedback (using the “submit” button at the bottom of the review form), the clinician can simply close the window and continue her original activity.

Figure 4.

Examples of the “K-Button” within a clinical information system (“A” – HELP2 System, orders module) and an intranet application (“B” – Collaborative Practice Guidelines viewer).

Clinicians normally also have the ability to easily review the asset metadata while using a clinical system or an intranet application. In these cases, the title of the asset is a hyperlink that opens a new window containing the information about the knowledge asset (Figure 5). The metadata always includes the name and email of the asset author. If the clinician clicks at the author’s email, a new window is opened, allowing her to send an email directly to the author. The messages exchanged between clinicians and authors are not stored in the CKR.

Figure 5.

Information about the knowledge asset (metadata). A button on the top (“A”) enables the user to subscribe or unsubscribe to automated notifications. The email hyperlink (“B”) can be used to send an email to the author (custodian).

Some of the intranet applications and sites also have a “contact us” hyperlink as a default element that appears on every page. When a user clicks at this hyperlink, she is asked to choose between providing feedback related to the application or the knowledge content (i.e., knowledge asset collection). If the feedback is related to the content, the message is sent directly to the custodian of the asset collection.

The third scenario is not focused on the actual review activity, but more on the necessity of keeping peer reviewers engaged in the lifecycle of knowledge assets, particularly those that are relevant to them. In this scenario, clinicians are provided with a simple mechanism to receive an automated notification every time a new version of a given knowledge asset is published (Figure 5). The notification is delivered using an email message that explains the modifications that have been made, along with a hyperlink that can be used to promptly view the new version of the asset and another hyperlink that can be used to submit a review (Figure 6). The expectation is that this notification will trigger a timely voluntary review of the asset, following a process similar to the first scenario described. Another possibility is that this notification will prompt the clinician to somehow contact the author of the modifications to express concerns or ask for clarifications.

Figure 6.

Example of a notification explaining that a new version of the asset “DKA Problem” was released. The first hyperlink (“A”) can be used to view the asset and the second hyperlink (“B”) can be used to submit a review.

Peer Review utilization

The size and diversity of the CKR has been constantly increasing since its initial release back in June of 2003. As of March of 2006, 35,251 knowledge assets from 68 distinct categories are being stored in the CKR. The total number of active (i.e., released for clinical use) knowledge assets is 7,704 (21.9% of all assets, or 89.4% of all non-inactive assets). There are 536 (6.2% of all non-inactive assets) assets currently under review and 378 (4.4% of all non-inactive assets) under development. There are 1,061 unique users total, taking into account both authors and reviewers.

In terms of peer review, the CKR now stores 1,350 reviews associated with 689 “distinct” assets (i.e., different asset identifiers, irrespective of version). Taking into account the status of the asset, 355 (4.6%) of the active assets, 502 (93.7%) of the assets under review, and 88 (23.3%) of the assets under development have at least one review. The average number of reviews per asset is 1.96 (median is 1.0) and the number of assets with two or more reviews is 315 (45.7% of the assets with reviews).

In terms of diversity and engagement of reviewers, 164 (23.8% of the assets with reviews) assets have reviews from two or more reviewers. The number of users that have submitted at least one review is 167 (15.7% of the users) and the number of users that have submitted two or more reviews is 86 (8.1% of the users).

The number of users that are receiving an automated notification every time a new version of a given knowledge asset is published is 95 (9% of the users). Taking into account the status of the asset, 155 (2.0%) of the active assets, 26 (4.9%) of the assets under review, and 77 (20.4%) of the assets under development have at least one user enrolled to receive automated notifications.

Discussion

The continuous expansion and diversification of the CKR content confirm the usefulness of the clinical knowledge management infrastructure [17]. Similarly, the growing number of users indicates that the processes supported by the core software infrastructure tools are very relevant to a considerable number of clinicians.

Given our emphasis on cooperation, and particularly on peer review, the utilization numbers seem to demonstrate that our framework is still on rather preliminary stages of adoption. The fact that only 1,350 reviews exist for a total of 35,251 assets clearly indicates that the vast majority of the assets are not being peer reviewed, at least not using the proposed software infrastructure. Other forms of cooperation and peer review are certainly occurring, such as team meetings and informal discussions, but unfortunately these are not properly documented nor actively tracked. Our goal is to eventually have all assigned peer review activities supported by the knowledge management software infrastructure. Likewise, we eventually want to have at least 2 to 5 volunteer reviews for every asset that has remained unchanged and in active use for at least six months.

The small fraction of users that have submitted two or more reviews confirms that few clinicians are using the peer review infrastructure. This is particularly true if one takes into account that there are virtually no access restrictions to use the knowledge management tools, and that the total number of potential users at Intermountain is over 15,000 clinicians. Our goal is to ultimately have 40 to 50% of the Intermountain clinicians engaged in voluntary peer review activities, confirmed by at least 3 to 5 new reviews per user every 12 months.

A positive result is that the vast majority of assets currently under review do indeed have at least one review. Hopefully this indicates that recently the various content authoring teams are becoming more aware of the existing peer review strategies.

Limitations of the results presented include the fact that we did not attempt to distinguish reviews created by assigned versus volunteer reviewers, nor did we attempt to determine if frequently used documents had a proportionally larger number of reviews. Finally, we also did not attempt to correlate the existence of a review with the length of time that a given asset remained unchanged and in active use.

Conclusion

In reality, few organizations with comparable size and complexity have been attempting similar efforts, making it difficult to find other credible utilization results. Some of the interpretations above can be considered simple speculations. On the other hand, these numbers hopefully are an effort towards establishing a baseline that can be used by Intermountain and others to evaluate the degree of utilization of their clinical knowledge management infrastructure. These utilization numbers might represent indirect metrics that can be used to determine the degree of collaboration and “fingerprinting” that occurs within a clinical knowledge management framework.

In terms of next steps, we certainly need to increase the awareness and proficiency of clinicians regarding the available peer review strategies. In addition to user training, we also intend to continue enhancing the software infrastructure in terms of ease of use and functionality, including more effective utilization monitoring. Regarding functionality, we have been evaluating emerging web feed formats and web-based collaborative communities as promising extensions to the existing tools and services.

References

- 1.Drucker PF. Harvard Business Review on Knowledge Management. Boston: Harvard Business School Press; 1998. The Coming of the New Organization; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stefanelli M. Knowledge and process management in health care organizations. Methods Inf Med. 2004;43(5):525–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guptill J. Knowledge Management in Health Care. J Health Care Finance. 2005;31(3):10–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bali RK, editor. Clinical Knowledge Management: Opportunities and Challenges. Idea Group Publishing; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davenport TH, Glaser J. Just-in-Time Delivery Comes to Knowledge Management. Harvard Business Review. 2002 Jul;80(7):5–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.James BC. Make it easy to do it right (editorial) N Engl J Med. 2001;345(13):991–2. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200109273451311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clemmer TP, Spuhler VJ, Berwick DM, Nolan TW. Cooperation: the foundation of improvement. Ann Intern Med. 1998 Jun 15;128(12 Pt 1):1004–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-12_part_1-199806150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clemmer TP, Spuhler VJ. Developing and gaining acceptance for patient care protocols. New Horizons. 1998;6(1):12–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bergquist M, Ljungberg J, Lundh-Snis U. Practising peer review in organizations: a qualifier for knowledge dissemination and legitimization. Journal of Information Technology. 2001;16:99–112. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marriott S, Palmer C, Lelliott P. Disseminating healthcare information: getting the message across. Qual Health Care. 2000 Mar;9(1):58–62. doi: 10.1136/qhc.9.1.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilkinson SG, Rocha RA, Rhodes J. A Knowledge Development and Maintenance Process: Description and Evaluation. Proc of the 8th International Congress in Nursing Informatics. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Del Fiol G, Rocha RA, Washburn J, Rhodes J, Hulse N, Bradshaw RL, Roemer LK. On-demand Access to a Multi-Purpose Collection of Best Practice Standards. Proc of the 26th Annual International Conference of the IEEE EMBS. 2004:3342–45. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2004.1403939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roemer LK, Rocha RA, Del Fiol G, Bradshaw RL, Hanna TP, Hulse NC. Knowledge Management Strategies: Enhancing Knowledge Transfer to Clinicians and Patients. Proc of the 9th International Congress in Nursing Informatics. 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bigelow SM, Xu X, Del Fiol G, Rocha RA, Washburn J. Integration of Interdisciplinary Guidelines with Clinical Applications: Current and Future Scenarios. Proc of the 9th International Congress in Nursing Informatics. 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roemer LK, Rocha RA, Del Fiol G. Integration of HTML Documents into an XML-Based Knowledge Repository. Proc of the AMIA 2005 Annual Fall Symposium. 2005:1097. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Del Fiol G, Rocha RA, Bradshaw RL, Hulse NC, Roemer LK. An XML Model that Enables the Development of Complex Order Sets by Clinical Experts. IEEE Trans Inf Technol Biomed. 2005;9(2):216–28. doi: 10.1109/titb.2005.847200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hulse NC, Rocha RA, Del Fiol G, Bradshaw RL, Hanna TP, Roemer LK. KAT: A Flexible XML-based Knowledge Authoring Environment. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2005;12(4):418–30. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilkinson SG. Knowledge Repository Online: An Electronic Knowledge Development and Maintenance Process. Master’s thesis. Department of Medical Informatics; University of Utah: 2003. [Google Scholar]