Abstract

PURPOSE

This paper describes the ethnic and socioeconomic correlates of psychosocial functioning in a cohort of long-term nonrecurring breast cancer survivors and determines the contribution of ongoing difficulties, including symptoms and concerns about cancer, to the ethnic and socioeconomic differences in functioning levels.

METHODS

Participants (n=804) in this study were women from the Health, Eating, Activity, and Lifestyle (HEAL) Study, a population-based, multicenter, multiethnic, prospective study of women newly diagnosed with in situ or Stages I to IIIA breast cancer. Measurements occurred at three timepoints following diagnosis (average 6.1 months following diagnosis, at approximately 30.5 months post diagnosis, at approximately 40.6 months post diagnosis). Outcomes included standardized measures of functioning (MOS SF-36).

RESULTS

Overall, these long-term survivors reported values on two physical function subscales of the SF-36 slightly lower than population norms. Black women reported statistically significantly lower physical functioning scores (p=0.01), compared with White and Hispanic women, but higher mental health scores (p<0.01) compared with White and Hispanic women. In the final adjusted model, race was significantly related to physical functioning, with Black participants and participants in the “Other” ethnic category reporting poorer functioning compared to the White referent group (p<0.01, 0.05). Not working outside the home, being retired or disabled and being unemployed (on leave, looking for work) were associated with poorer physical functioning compared to currently working (both p<0.01).

CONCLUSION

These data indicate that race/ethnicity influences psychosocial functioning in breast cancer survivors and can be used to identify need for targeted interventions to improve functioning.

INTRODUCTION

Recent key papers1-4 indicate that many of the quality of life (QOL) difficulties experienced by breast cancer survivors in the short term (i.e., during the first two years post diagnosis) resolve over time. However, some women report decrements in several aspects of QOL up to four years after diagnosis.3,5,6 Several disparity-based explanations are explored in this paper. First, it is likely that demographic differences exist in long term functioning of cancer patients, although very little has been published on the survivorship experience of a demographically diverse group of women2,3 7,8 Second, continuing experience of symptoms, including hormone related symptoms,5 lymphedema,3,9 and fatigue,10 could interfere with functioning. Finally, the worry and fear of cancer recurrence may be another type of reminder of the initial experience, of vulnerability, and of potential mortality.11 Worry about recurrence and its meaning could interfere with women's ability to put the cancer experience behind them and could interfere with their overall functioning. These potential psychosocial explanations (worry, symptoms) may also be related to the differences among demographic subgroups, providing clues to explain disparities in functioning outcomes.

The research aims of this paper are: (1) to describe the ethnic and socioeconomic correlates of functioning in a diverse cohort of long-term nonrecurring breast cancer survivors and (2) to determine the contribution of ongoing difficulties, including symptoms and concerns about cancer, to the ethnic and socioeconomic differences in functioning levels.

METHODS

Study Design

Participants were enrolled in the Health, Eating, Activity, and Lifestyle (HEAL) Study, a population-based, multicenter, multiethnic, prospective study of women newly diagnosed with in situ or Stages I to IIIA breast cancer. HEAL study participants are being followed to determine the impact of weight, physical activity, diet, hormones, and other exposures on breast cancer prognosis. All study protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of each participating center. The baseline interview occurred on average 6.1 months following diagnosis. A second interview (24-month assessment) was conducted approximately 24.4 months following the baseline interview, at approximately 30.5 months post diagnosis. A third assessment (QOL assessment) was administered on average 34.5 months following the baseline interview, at approximately 40.6 months post diagnosis. Women with new primary cancer or recurrent cancer were excluded from all analyses.

Eligibility and Recruitment

Female patients diagnosed with their first primary breast cancer were recruited from National Cancer Institute sponsored Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) registries in three geographic regions of the United States, and data on two of the sites have been previously published.12 Incident breast cancer patients at the third site (Los Angeles County, California) were initially recruited to participate in one of two population-based case-control studies, a study of in situ breast cancer13,14 and a study of invasive breast cancer.15,16 Women were eligible to participate in these two case control studies if they were age 35 to 64 years at diagnosis, Caucasian or Black, and born in the United States. Los Angeles County participants in these studies were included in the HEAL study if they were (1) Black, (2) diagnosed between May 1995 and May 1998, and (3) satisfied the HEAL stage eligibility criterion. Overall, less than 2.4% of the participants were beyond the 12-month window.

Data Collection

The baseline interview occurred from 1 to 9 months following diagnosis (mean = 5.3 months) in New Mexico, from 3 to 23 months following diagnosis (mean = 7.5 months) in Western Washington, and from 2 weeks to 17 months following diagnosis (mean = 6.0 months) in Los Angeles County. The 24-month assessment was conducted 17-32 months after the baseline interview (mean = 22.9 months) in New Mexico, 12-29 months after the baseline interview (mean = 24.2 months) in Western Washington, and 23-45 months after the baseline interview (mean = 27.3 months) in Los Angeles County. Quality of life assessments were added as a third assessment after the baseline data collection occurred. The QOL assessment was administered by telephone interview and mailed questionnaire in New Mexico, by mailed questionnaire plus telephone follow-up in Washington, and by telephone interview in Los Angeles County, 26-54 months post-baseline (mean = 36.4 months) in New Mexico, 15-37 months post-baseline (mean = 26.0) in Western Washington, and 28-54 months post-baseline (mean = 37.3 months) in Los Angeles County. In women completing the QOL assessment, only 1.2% were beyond the 12 month post diagnosis window for the baseline assessment.

Measures

General functioning

We used the Medical Outcomes Study short form 36 (SF-36) health status measure created to measure physical and mental health functioning in healthy populations.17,18 This widely used measure includes 36 items, scored into eight subscales: Physical Functioning (PF), Role-Physical (RP), Bodily Pain (BP), General Health (GH), Vitality (VT), Social Functioning (SF), Role-Emotional (RE), and Mental Health (MH), and a physical component and a mental component summary scale. All SF-36 subscales ranged from zero to 100 with increasing scores indicating better functioning, per standard coding protocol. Our own analyses indicate high internal consistency among items in the eight subscales (Cronbach's alphas ranged from 0.78-0.91). These scales and subscales served as outcome measures for the present analyses.

Demographic variables

We used standard measures of age in years, education, and race/ethnicity collected at baseline. We used information on marital status, household income, and employment at the 24-month assessment in order to reflect the status of these measures closest to the time of the QOL assessment.

Menopausal status

Menopausal status was determined at the 24-month assessment using an algorithm that assigned women into pre, post, or unclassifiable menopausal status based on the following data: age, date of last menstruation, hysterectomy and oophorectomy status. To define menopausal status for women without a uterus or those taking HRT, we first considered all women who were 55 years of age or older, and who had not menstruated in the last year, who did not know the date of their last menstruation but reported having had a hysterectomy, or who were less than age 55 and had not menstruated in the last year prior to their interview, as postmenopausal. The following groups of women were categorized as unknown menopausal status: women less than age 55, who had a hysterectomy, but had at least one ovary remaining; and women 55 years of age or older with an intact uterus, who were still menstruating but had used HRT within a year or more prior to interview. The remaining women were classified as premenopausal.

Stage of breast cancer and treatment

Stage of disease was based on SEER data. Treatment information was abstracted from medical record abstraction and SEER registry records. Treatment data were recoded as: surgery only; surgery with chemotherapy; surgery with radiation, or the combination of all three treatments. Tamoxifen use was categorized as use between baseline and 24-months, use at or before baseline only, or no use during the study period.

Antidepressant use

Self-reported use of antidepressant medication was collected at the 24-month assessment and categorized as currently taking at 24 months versus not currently taking at 24 months.

Hormone-related symptom checklist

Hormone symptoms were measured with 14 items representing the most relevant symptoms for a population of breast cancer survivors. Previous psychometric work using the HEAL cohort indicated five separate reliable and valid scales for vasomotor symptoms (α = 0.74), urinary incontinence (α = 0.88), cognitive/mood symptoms (α = 0.83), vaginal symptoms (α = 0.60), and weight gain/appearance concerns (α = 0.70).19 All five scales were coded 0-4 with increasing scores indicating more severe symptoms.

Lymphedema

We constructed an index of self-reported lymphedema, with three levels: currently experiencing lymphedema (current lymphedema), did experience lymphedema, but not currently experiencing lymphedema (no current lymphedema), and never experienced lymphedema (never had lymphedema).

Fatigue

We measured the duration of fatigue using two questions. We first asked about feeling fatigued in the past four weeks. If the participant answered yes, we asked about how long she had felt fatigued, with response categories of minutes, hours, days, weeks, or months. We constructed a simple three-level index of fatigue duration: fatigued for weeks or months (longer-term fatigued), fatigued for minutes, hours, or days (short-term fatigued), and never fatigued.

Impact of Cancer

Impact of cancer was measured with four scales measuring the impact on four separate domains of life: Caregiving/Finances (α = 0.77), Exercise/Diet (α = 0.63), Social/Emotional (α = 0.75), and Religiosity (α = 0.80).20

Fear of Recurrence

For the current study we used a 5-item version of the Fear of Recurrence scale21 which has not been previously validated. The five items included: “I would like to feel more certain about my health”; “I worry that my cancer will return”; “I am bothered about the uncertainty about my health status”; “When I think about my future health status, I feel some uneasiness”; “I am preoccupied with thoughts of the cancer returning.” The five items in this subscale capture concerns about future health status including concerns about cancer recurrence. Confirmatory CFI = 0.99, Tucker-Lewi factor analysis indicated that all items loaded onto one common factor (Comparative Fit Index s Index TLI = 0.99). The single factor accounted for 66% of the scale variance. Cronbach's α in the present sample was 0.82 and item-total score correlations ranged from 0.48 to 0.76 indicating moderate to high factor loadings for all items in the subscale. Possible scores on the summed 5-item scale ranged from five to 25 with higher scores indicating higher fear of recurrence.

Analysis plan

The analyses presented in this paper use data collected through November 18th, 2004. The data were analyzed using SAS/STAT software, version 9 of the SAS System for Windows. Copyright ©2002 SAS Institute Inc. Confirmatory factor analysis on the 5-item version of the FOR was conducted using version 3.01 of MPlus, which is a specialized software that is designed for analyzing ordinal level data.22 Imputation of missing values was considered for psychosocial scales that were used as outcome variables in our analyses (i.e., for SF-36, hormone-related symptoms, BCIA, and FOR). SF-36 subscales with missing item responses were imputed following standard scoring methods.23 Missing hormone-related symptoms and BCIA scale scores were imputed (for less than 3% of participants) based on the average of non-missing item responses, when at least 50% of the scale items were not missing; no imputation was necessary for the FOR scale responses. Imputation of missing values was not considered for any other measure.

Fisher's exact tests were used to identify differences between HEAL enrollees who did and did not complete the QOL survey at the follow-up period. We next fit linear regression models to evaluate the associations between race/ethnicity and socioeconomic variables with the study's QOL measures. Centering of continuous measures was not performed in our regression models. We controlled for baseline (age in years, stage at diagnosis, breast cancer treatment type) and 24-month (marital status, current employment, menopausal status, months from breast cancer diagnosis to QOL survey, tamoxifen use, antidepressant use) characteristics in all subsequent analyses. Indicator variables representing the three HEAL sites were not included in our models due to their strong associations with the racial/ethnic groups recruited by each site. In addition, we did not use 24-month household income (collected at the 24-month follow-up interview) as a socioeconomic predictor in the regression models due to the extent of missing data reported. We next described differences in symptom reporting, impact of cancer, and fear of recurrence at the follow-up measurement period, by education, race/ethnicity, and employment status. We used these intermediate outcomes, along with fatigue and lymphedema, to predict the overall physical and mental functioning variables.

RESULTS

Table 1 presents the HEAL cohort at enrollment and at the QOL measurement (n=805). See Alfano et al.19 for a figure of this process. However, for the analyses that are presented here, 1 woman did not have complete data sufficient to compute psychosocial scales; thus, the final sample size available for analysis was 804 women.

Table 1.

HEAL eligibility and participation.

| Western Washington |

New Mexico |

Los Angeles |

Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total completed baseline surveys |

202 (17%) |

615 (52%) |

366 (31%) |

1183 (100%) |

|

| ||||

|

| ||||

| 24-month Follow-up survey | ||||

| Deceased | 0 | 25 | 19 | 44 |

| Patient refusal | 12 | 64 | 28 | 104 |

| Unable to contact | 0 | 0 | 17 | 17 |

| Unable to locate | 2 | 14 | 39 | 55 |

| Too ill to complete questionnaire | 0 | 17 | 2 | 19 |

| Total completed 24-month follow-up surveys |

188 (93%) |

495 (80%) |

261 (71%) |

944 (80%) |

|

| ||||

|

| ||||

| Quality of Life (QOL) Survey | ||||

| Deceased a | 0 | 49 | 26 | 75 |

| Patient refusal | 22 | 64 | 54 | 140 |

| Unable to contact | 0 | 33 | 17 | 50 |

| Unable to locate | 2 | 4 | 43 | 49 |

| Too ill to complete survey | 1 | 7 | 3 | 11 |

| Total completed QOL surveys |

177 (88%) |

458b (74%) |

223 (61%) |

858 (73%) |

|

| ||||

| Excluded due to recurrence/new primary breast cancer by QOL survey date c | 10 | 18 | 25 | 53 |

| Total participants for QOL analyses |

167 (83%) |

440 (72%) |

198 (54%) |

805 (68%) |

Participants deceased prior to QOL survey, including those deceased prior to 24-month survey.

Includes 29 participants who did not complete the 24-month follow-up survey.

Out of the total completed QOL survey.

Table 2 presents demographic and medical characteristics of the 804 participants who provided data at the QOL measurement point, compared to the 304 participants who did not provide QOL data at the follow-up period. As shown in this table, there were key differences in the distributions between the two groups of women. Non-completers were significantly more likely to be younger or older (p<0.01), of lower educational attainment (p<0.01), and either Black or Hispanic (p<0.01). Also, non-completers were slightly, but significantly, more likely to be diagnosed at a more advanced breast cancer stage (p<0.01) and more likely to have received treatment (p<0.01).

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of 804 HEAL participants who completed the quality of life follow-up survey, compared to 304 participants who did not.

| Characteristic | Completed (n = 804) | Not Completed† (n = 304) | P‡ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Baseline | |||||

| Age (yr) | |||||

| 29-49 | 239 | 29.7 | 125 | 41.1 | <0.01 |

| 50-59 | 301 | 37.4 | 79 | 26.0 | |

| 60-69 | 178 | 22.1 | 45 | 14.8 | |

| 70+ | 86 | 10.7 | 55 | 18.1 | |

| (mean ± sd) | (55.5 ± 10.4) | (55.3 ± 13.3) | 0.81 | ||

| Education | |||||

| HS or less | 205 | 25.5 | 126 | 41.4 | <0.01 |

| Some college | 293 | 36.5 | 117 | 38.5 | |

| College grad | 156 | 19.4 | 30 | 9.9 | |

| Grad school | 149 | 18.6 | 31 | 10.2 | |

| (missing) | (1) | ||||

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 486 | 60.4 | 121 | 39.8 | <0.01 |

| Black | 199 | 24.8 | 135 | 44.4 | |

| Hispanic | 95 | 11.8 | 48 | 15.8 | |

| Other | 24 | 3.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Registry | |||||

| Western Washington | 167 | 20.8 | 22 | 7.2 | <0.01 |

| New Mexico | 439 | 54.6 | 147 | 48.4 | |

| Los Angeles | 198 | 24.6 | 135 | 44.4 | |

| Stage at diagnosis | |||||

| In situ | 179 | 22.3 | 48 | 15.8 | <0.01 |

| Localized | 453 | 56.3 | 165 | 54.5 | |

| Regional | 172 | 21.4 | 90 | 29.7 | |

| (unstaged) | (1) | ||||

| Breast cancer treatment type | |||||

| Surgery + chemotherapy | 74 | 9.2 | 40 | 13.2 | <0.01 |

| Surgery + chemotherapy + radiation | 174 | 21.6 | 64 | 21.1 | |

| Surgery + radiation | 296 | 36.8 | 100 | 32.9 | |

| Surgery only | 260 | 32.3 | 95 | 31.3 | |

| Other | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 1.6 | |

| 24-Month Follow-up | |||||

| Marital status | |||||

| Married | 450 | 58.1 | |||

| Widowed/divorced/separated | 272 | 35.1 | |||

| Never married | 52 | 6.7 | |||

| (missing)* | (30) | ||||

| Current employment | |||||

| Currently working | 450 | 58.1 | |||

| Unemployed (on leave, looking for work) | 26 | 3.4 | |||

| Not working outside the home/retired/disabled | 299 | 38.6 | |||

| (missing)* | (29) | ||||

| Income ($) | |||||

| <= 10K | 54 | 7.4 | |||

| >10K – 20K | 86 | 11.9 | |||

| >20K – 30K | 93 | 12.8 | |||

| >30K – 50K | 168 | 23.2 | |||

| >50K – 70K | 211 | 29.1 | |||

| >70K | 113 | 15.6 | |||

| (missing)* | (79) | ||||

| Menopausal status | |||||

| Pre | 143 | 18.4 | |||

| Post | 589 | 75.8 | |||

| Unable to categorize | 45 | 5.8 | |||

| (missing)* | (27) | ||||

| Tamoxifen | |||||

| Use between baseline & 24 mo | 350 | 45.0 | |||

| Use at or before baseline only | 69 | 8.9 | |||

| No use during study period | 358 | 46.1 | |||

| (missing)* | (27) | ||||

| Antidepressants | |||||

| Currently taking at 24 mo | 119 | 15.3 | |||

| Not currently taking at 24 mo | 658 | 84.7 | |||

| (missing)* | (27) | ||||

| Months from diagnosis to QOL survey | |||||

| 23 – 35 | 193 | 24.0 | |||

| 36 – 41 | 274 | 34.1 | |||

| 42 – 47 | 209 | 26.0 | |||

| 48 – 63 | 128 | 15.9 | |||

| (mean ± sd) | (40.5 ± 6.5) | ||||

Note: Table 2 reports on 1108 participants that were not diagnosed with a recurrent or new primary breast cancer by the time of the QOL survey date (out of the 1183 that completed a baseline survey).

Includes one additional woman that provided an incomplete QOL follow-up survey (insufficient to compute psychosocial scale scores).

P-values are either from Fisher's exact tests for categorical variables, or from a t-test for the difference in mean age.

Includes women with baseline and QOL data who did not complete a 24-month assessment (n = 27).

Data on physical and mental health functioning summary scores by socioeconomic level and by race/ethnicity are provided in Table 3. Race/ethnicity was a significant correlate of physical (p=0.01) and mental (p<0.01) summary scores. Black women reported statistically significantly lower physical functioning scores, compared with White and Hispanic women, but higher mental health scores compared with White and Hispanic women. Employment status was also significantly associated with physical functioning (p<0.01). Restricting the analyses to women aged 35-64, the age of the Black women, or conducting analyses without the “other” race category, did not alter the pattern of findings.

Table 3.

Mean (SD) and least-squares mean values of functional status scores by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic level [n = 771].

| Characteristic | SF-36 Physical Component Score |

SF-36 Mental Component Score |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean (SD) | LSM† | P | Mean (SD) | LSM† | P | |

| Education | |||||||

| HS or less | 194 | 43.8 (11.6) | 41.1 | 0.27 | 49.8 (11.4) | 46.7 | 0.27 |

| Some college | 280 | 44.9 (11.0) | 40.9 | 49.4 (10.7) | 46.4 | ||

| College grad | 152 | 48.4 (9.7) | 42.8 | 50.7 (8.1) | 48.3 | ||

| Grad school | 145 | 48.5 (9.9) | 42.2 | 49.8 (9.4) | 47.8 | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 463 | 47.0 (10.5) | 43.0 | 0.01 | 49.2 (9.7) | 46.9 | <0.01 |

| Black | 198 | 43.5 (11.6) | 40.4 | 52.7 (10.6) | 50.9 | ||

| Hispanic | 86 | 46.8 (9.2) | 44.0 | 47.2 (10.7) | 44.9 | ||

| Other | 24 | 43.4 (13.9) | 39.4 | 46.9 (10.5) | 46.5 | ||

| Current employment | |||||||

| Currently working | 447 | 48.8 (9.4) | 45.6 | <0.01 | 49.8 (9.9) | 48.3 | 0.38 |

| Unemployed (on leave, looking for work) | 26 | 43.4 (10.5) | 39.8 | 48.4 (12.1) | 46.4 | ||

| Not working outside the home/retired/disabled | 298 | 42.0 (11.7) | 39.8 | 50.0 (10.5) | 47.2 | ||

| Income ($) | |||||||

| <= 10K | 53 | 38.0 (12.6) | 47.6 (12.8) | ||||

| >10K – 20K | 86 | 41.1 (11.8) | 49.5 (10.9) | ||||

| >20K – 30K | 92 | 46.0 (10.7) | 49.9 (10.7) | ||||

| >30K – 50K | 166 | 46.5 (10.8) | 49.8 (9.5) | ||||

| >50K – 70K | 210 | 48.2 (9.4) | 49.8 (10.1) | ||||

| >70K | 112 | 48.9 (9.1) | 49.7 (10.1) | ||||

| (52 missing) | |||||||

| Overall | 771 | 46.0 (10.9) | 49.8 (10.2) | ||||

Least-squares means (LSM) adjust for baseline (age in years, education level, race/ethnicity, stage at diagnosis, breast cancer treatment type) and follow-up (marital status, current employment, menopausal status, tamoxifen use, antidepressant use, months from diagnosis to quality of life survey) characteristics. Follow-up income has been excluded as a model variable due to missing data, resulting in no corresponding LSM estimate. Overall R2 = 0.20 for relating to the physical component score; R2 = 0.11 for relating to the mental component score. P-values are computed based on LSM comparisons. Note: SF-36 component scales have a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10, with increasing scores indicating better functioning.

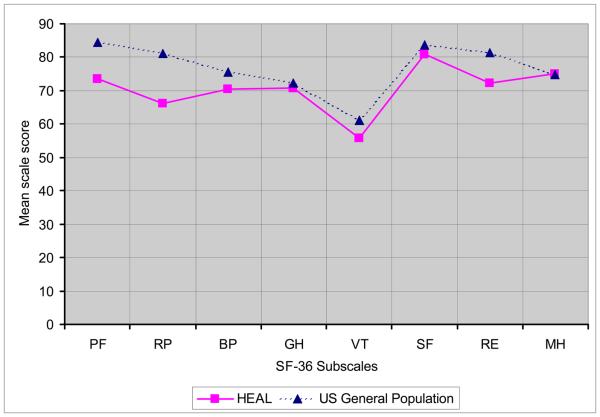

Figure 1 presents data on the specific and independent eight subscale scores for the SF-36, compared to national norms.23 As seen in this figure, HEAL participants reported lower scores on most of the subscale scores, but particularly the physical functioning, role-physical, and role-emotional scores. The largest differences were in physical functioning and role-physical subscales, where the scores for these breast cancer survivors were approximately one standard deviation below population means.

Figure 1.

Mean SF-36 subscale scores for HEAL participants [n=771] compared with US population norms

PF = Physical functioning GH = General health RE = Role-emotional

RP = Role-physical VT = Vitality MH = Mental health

BP = Bodily pain SF = Social functioning

Note: SF-36 subscales ranged from 0-100 with increasing scores indicating better functioning.

Tables 4a and 4b present the results of analyses to determine the relationships between demographic variables and both hormone-related symptoms and BCIA scale scores. Significant relationships between symptom level and sociodemographic variables were reported for Black women versus other women in cognitive/mood (p<0.01), incontinence (p<0.01), and weight/appearance (p<0.01) symptoms. Table 4b contains the results of the BCIA on five scales, each representing a different dimension of life. Scores for the Exercise/Diet subscale differed significantly by educational levels (p<0.01). Higher education level was associated with a more positive impact of breast cancer on exercise/diet subscale (p for trend < 0.01). White and Black women reported a greater negative impact of cancer on the caregiving/finances domain, compared to Hispanic women. Hispanic women reported significantly greater positive impact of cancer on religiosity compared with both Black and White women. Employment levels were significantly related to the Caregiving/Finances (p<0.01) and Social/Emotional (p=0.05) scores, with women who were unemployed (seeking a job or on leave) reporting a greater negative impact of cancer than employed women. FOR scores were greater among White and Hispanic women, compared to Black women.

Table 4a.

Mean and least-squares mean (LSM) values for symptoms scale scores, by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic level [n = 771].

| Characteristic | Cognitive / Mood | Urinary Incontinence | Vasomotor | Weight / Appearance | Vaginal | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (LSM†) | P | Mean (LSM†) | P | Mean (LSM†) | P | Mean (LSM†) | P | Mean (LSM†) | P | |

| Education | ||||||||||

| High school or less | 1.11 (1.46) | 0.61 | 0.88 (1.19) | 0.97 | 1.62 (1.52) | 0.43 | 1.37 (1.76) | 0.44 | 0.56 (0.62) | 0.41 |

| Some college | 1.04 (1.40) | 0.89 (1.23) | 1.60 (1.51) | 1.38 (1.70) | 0.55 (0.61) | |||||

| College graduate | 1.04 (1.38) | 0.89 (1.21) | 1.52 (1.36) | 1.40 (1.60) | 0.47 (0.50) | |||||

| Graduate school | 1.04 (1.34) | 0.93 (1.24) | 1.69 (1.41) | 1.47 (1.58) | 0.59 (0.61) | |||||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 1.08 (1.39) | <0.01 | 1.00 (1.30) | <0.01 | 1.62 (1.54) | 0.10 | 1.46 (1.70) | <0.01 | 0.56 (0.61) | 0.51 |

| Black | 0.92 (1.16) | 0.58 (0.87) | 1.54 (1.30) | 1.10 (1.22) | 0.53 (0.53) | |||||

| Hispanic | 1.17 (1.45) | 0.94 (1.23) | 1.63 (1.56) | 1.58 (1.80) | 0.50 (0.52) | |||||

| Other | 1.47 (1.57) | 1.21 (1.48) | 1.79 (1.40) | 2.06 (1.92) | 0.63 (0.67) | |||||

| Current employment | ||||||||||

| Currently working | 1.05 (1.29) | 0.04 | 0.79 (1.06) | 0.08 | 1.72 (1.46) | 0.97 | 1.57 (1.67) | 0.41 | 0.53 (0.47) | 0.10 |

| Unemployed (on leave, | 1.12 (1.42) | 1.02 (1.34) | 1.54 (1.46) | 1.56 (1.77) | 0.69 (0.71) | |||||

| looking for work) | ||||||||||

| Not working outside the home/retired/disabled | 1.07 (1.47) | 1.05 (1.25) | 1.44 (1.43) | 1.14 (1.54) | 0.55 (0.57) | |||||

| Income ($) | ||||||||||

| <= 10K | 1.28 | 0.94 | 1.36 | 1.19 | 0.48 | |||||

| >10K – 20K | 1.02 | 0.97 | 1.26 | 1.15 | 0.60 | |||||

| >20K – 30K | 1.08 | 0.98 | 1.48 | 1.34 | 0.47 | |||||

| >30K – 50K | 1.03 | 0.83 | 1.66 | 1.39 | 0.60 | |||||

| >50K – 70K | 1.08 | 0.98 | 1.81 | 1.60 | 0.53 | |||||

| >70K | 1.00 | 0.73 | 1.60 | 1.50 | 0.55 | |||||

| (52 missing) | ||||||||||

| Overall Sample Mean | 1.06 | 0.89 | 1.61 | 1.40 | 0.54 | |||||

| [Overall R2] | [0.122] | [0.088] | [0.179] | [0.164] | [0.098] | |||||

Least-squares means (LSM) adjust for baseline (age in years, education level, race/ethnicity, stage at diagnosis, breast cancer treatment type) and follow-up (marital status, current employment, menopausal status, tamoxifen use, antidepressant use, months from diagnosis to quality of life survey) characteristics. Follow-up income has been excluded as a model variable due to missing data, resulting in no corresponding LSM estimate. P-values are computed based on LSM comparisons.

Note: Hormone-related symptom scales were coded 0-4 with increasing scores indicating more severe symptoms.

Table 4b.

Mean and least-squares mean (LSM) values for BCIA and fear of recurrence scale scores, by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic level [n = 771].

| Characteristic | Caregiving/ Finances | Social / Emotional | Religiosity | Exercise / Diet | Fear of Recurrence | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (LSM†) | P | Mean (LSM†) | P | Mean (LSM†) | P | Mean (LSM†) | P | Mean (LSM†) | P | |

| Education | ||||||||||

| High school or less | 0.03 (−0.00) | 0.14 | 0.01 (−0.03) | 0.18 | 0.54 (0.46) | 0.89 | 0.22 (−0.00) | 0.01 | 15.9 (16.8) | 0.19 |

| Some college | −0.07 (−0.10) | −0.06 (−0.10) | 0.55 (0.49) | 0.26 (0.03) | 16.1 (16.9) | |||||

| College graduate | −0.06 (−0.10) | 0.05 (−0.01) | 0.58 (0.52) | 0.53 (0.24) | 15.5 (16.0) | |||||

| Graduate school | −0.07 (−0.11) | 0.06 (0.01) | 0.60 (0.52) | 0.54 (0.27) | 15.8 (16.2) | |||||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | −0.07 (−0.19) | <0.01 | −0.01 (−0.15) | 0.02 | 0.53 (0.44) | 0.02 | 0.39 (0.09) | 0.43 | 16.0 (16.1) | <0.01 |

| Black | −0.06 (−0.16) | −0.03 (−0.12) | 0.57 (0.44) | 0.27 (0.03) | 14.9 (14.4) | |||||

| Hispanic | 0.10 (−0.03) | 0.09 (−0.04) | 0.78 (0.68) | 0.40 (0.13) | 17.0 (16.9) | |||||

| Other | 0.15 (0.07) | 0.25 (0.18) | 0.53 (0.43) | 0.46 (0.30) | 18.5 (18.4) | |||||

| Current employment | ||||||||||

| Currently working | −0.01 (0.08) | <0.01 | 0.03 (0.07) | 0.05 | 0.62 (0.59) | 0.12 | 0.40 (0.10) | 0.34 | 16.0 (16.3) | 0.84 |

| Unemployed (on leave, looking for work) | −0.35 (−0.25) | −0.19 (−0.15) | 0.51 (0.44) | 0.58 (0.27) | 16.3 (16.8) | |||||

| Not working outside the home/retired/disabled | −0.06 (−0.07) | −0.02 (−0.02) | 0.48 (0.47) | 0.27 (0.03) | 15.6 (16.3) | |||||

| Income ($) | ||||||||||

| <= 10K | −0.17 | −0.16 | 0.34 | 0.05 | 15.9 | |||||

| >10K – 20K | −0.10 | 0.05 | 0.54 | 0.24 | 15.6 | |||||

| >20K – 30K | −0.04 | −0.08 | 0.45 | 0.32 | 15.8 | |||||

| >30K – 50K | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.66 | 0.41 | 15.9 | |||||

| >50K – 70K | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.56 | 0.39 | 16.0 | |||||

| > 70K | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.68 | 0.51 | 16.5 | |||||

| (52 missing) | ||||||||||

| Overall sample mean | -0.04 | 0.00 | 0.57 | 0.36 | 15.9 | |||||

| [Overall R2] | [0.086] | [0.091] | [0.044] | [0.112] | [0.065] | |||||

Least-squares means (LSM) adjust for baseline (age in years, education level, race/ethnicity, stage at diagnosis, breast cancer treatment type) and follow-up (marital status, current employment, menopausal status, tamoxifen use, antidepressant use, months from diagnosis to quality of life survey) characteristics. Follow-up income has been excluded as a model variable due to missing data, resulting in no corresponding LSM estimate. P-values are computed based on LSM comparisons.

Note: BCIA scores were centered at 0 (no impact), with values ranging from −2 (very negative impact) to +2 (very positive impact); Fear of recurrence was coded 5-25 with higher scores indicating higher fear of recurrence.

We examined differences in the fatigue and lymphedema by the same demographic data (data not shown in table). A total of 27.4 percent of women reported short-term fatigue, 37.0% reported long-term fatigue, and 35.6% reported no fatigue. For self-reported lymphedema, 13.9% reported current lymphedema, 6.1% reported past lymphedema, and 80.0% reported never having lymphedema.

Table 5 contains the results of regression models using both socioeconomic indicators from Table 3 and potential mechanisms from Table 4 (hormonal and other symptoms, impact of cancer, and fear of recurrence) as correlates of physical and mental health functioning scores. In the final model, where demographic and psychosocial variables were included together, race was significantly related to physical functioning, with Black participants and participants in the “Other” ethnic category reporting poorer functioning compared to the White referent group (p<0.01, 0.05). Not working outside the home, being retired or disabled and being unemployed (on leave, looking for work) were associated with poorer physical functioning compared to currently working (p<0.01, <0.01). More severe urinary incontinence symptoms and greater fear of recurrence were both associated with lower physical functioning scores (p=0.04, 0.04, respectively). A less negative impact of cancer on the caregiver/financial domain was associated with an increase in physical functioning (p=0.01). However, a less negative impact of cancer on the social/emotional domain was related to a decrease in physical functioning (p=0.03). More positive impact of cancer on exercise/diet was related to an increase in physical functioning (p<0.01). In addition, current lymphedema and both short- and long-term fatigue were related to poorer physical functioning (p<0.01 for all three variables), in both the unadjusted and the adjusted models.

Table 5.

Linear regression models relating functional status scores to physiological and psychosocial variables and background characteristics [n = 767]†.

| Characteristic | SF-36 Physical Component Score | SF-36 Mental Component Score | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (SE) | P | β (SE)‡ | P | β (SE) | P | β (SE)‡ | P | |

| Education | ||||||||

| High school or less | −0.25 (1.06) | 0.82 | −0.03 (0.98) | 0.98 | ||||

| Some college | −0.75 (0.95) | 0.43 | −0.52 (0.88) | 0.55 | ||||

| College graduate | 0.36 (1.05) | 0.73 | 0.05 (0.96) | 0.96 | ||||

| Graduate school [referent] | 0.00 (-----) | ----- | 0.00 (-----) | ----- | ||||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White [referent] | 0.00 (-----) | ----- | 0.00 (-----) | ----- | ||||

| Black | −3.42 (0.99) | <0.01 | 1.72 (0.91) | 0.06 | ||||

| Hispanic | 0.27 (1.11) | 0.81 | −2.02 (1.02) | 0.05 | ||||

| Other | −3.75 (1.92) | 0.05 | 0.54 (1.77) | 0.76 | ||||

| Current employment | ||||||||

| Currently working [referent] | 0.00 (-----) | ----- | -----(-----) | ----- | ||||

| Unemployed (on leave, looking for work) | −5.35 (1.86) | <0.01 | −1.12 (1.71) | 0.51 | ||||

| Not working outside the home/retired/disabled | −4.80 (0.87) | <.01 | −0.03 (0.80) | 0.97 | ||||

| Physiological/Psychosocial Variabless | ||||||||

| Symptoms | ||||||||

| Cognitive / Mood | −1.16 (0.57) | 0.04 | −0.75 (0.54) | 0.16 | −4.22 (0.48) | <0.01 | −3.84 (0.50) | <0.01 |

| Urinary incontinence | −1.29 (0.36) | <0.01 | −0.70 (0.34) | 0.04 | 0.12 (0.30) | 0.69 | 0.18 (0.31) | 0.56 |

| Vasomotor | 0.58 (0.36) | 0.11 | 0.00 (0.35) | 0.99 | 0.28 (0.30) | 0.36 | 0.14 (0.33) | 0.66 |

| Weight / Appearance | 0.67 (0.35) | 0.06 | −0.28 (0.35) | 0.42 | −0.12 (0.30) | 0.68 | 0.14 (0.32) | 0.66 |

| Vaginal | −0.28 (0.51) | 0.58 | −0.35 (0.49) | 0.47 | −0.07 (0.43) | 0.87 | −0.25 (0.45) | 0.58 |

| Brief Cancer Impact | ||||||||

| Assessment scales | ||||||||

| Caregiving / Finances | 2.26 (0.92) | 0.01 | 2.45 (0.88) | 0.01 | 0.68 (0.78) | 0.38 | 0.67 (0.81) | 0.41 |

| Social / Emotional | −1.17 (0.84) | 0.16 | −1.71 (0.79) | 0.03 | 2.23 (0.71) | <0.01 | 2.10 (0.73) | <0.01 |

| Religiosity | 0.66 (0.56) | 0.24 | 0.32 (0.52) | 0.54 | −0.92 (0.47) | 0.05 | −0.90 (0.48) | 0.06 |

| Exercise / Diet | 2.59 (0.50) | <.01 | 2.11 (0.48) | <.01 | 0.62 (0.42) | 0.14 | 0.69 (0.44) | 0.12 |

| Fear of recurrence | −0.12 (0.08) | 0.16 | −0.16 (0.08) | 0.04 | −0.43 (0.07) | <0.01 | −0.42 (0.07) | <0.01 |

| Fatigue | ||||||||

| Long-term fatigued | −7.00 (0.98) | <0.01 | −6.99 (0.92) | <.01 | −6.03 (0.83) | <0.01 | −6.00 (0.84) | <0.01 |

| Short-term fatigued | −4.68 (0.85) | <0.01 | −3.66 (0.84) | <.01 | −1.76 (0.72) | 0.01 | −2.63 (0.77) | <0.01 |

| Never fatigued [referent] | 0.00 (-----) | ----- | 0.00 (-----) | ----- | 0.00 (-----) | ----- | 0.00 (-----) | ----- |

| Self-reported Lymphedema | ||||||||

| Current lymphedema | −3.80 (1.04) | <0.01 | −3.14 (1.00) | <0.01 | 2.50 (0.88) | <0.01 | 1.76 (0.92) | 0.06 |

| Past lymphedema | −1.66 (1.47) | 0.26 | −2.08 (1.39) | 0.13 | 0.40 (1.24) | 0.75 | 0.57 (1.27) | 0.65 |

| Never lymphedema [referent] | 0.00 (-----) | ----- | 0.00 (-----) | ----- | 0.00 (-----) | ----- | 0.00 (-----) | ----- |

| [Overall R2] | [0.235] | [0.380] | [0.386] | [0.411] | ||||

Excludes data from four additional women with unknown duration of fatigue.

Multiple regression model includes baseline (age in years, education level, race/ethnicity, stage at diagnosis, breast cancer treatment type) and follow-up (marital status, current employment, menopausal status, tamoxifen use, antidepressant use, months from diagnosis to QOL survey) characteristics, and twelve physiological/psychosocial variables (symptoms, impact of breast cancer, fear of recurrence, fatigue, and lymphedema).

Note: SF-36 component scales have a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10, with increasing scores indicating better functioning; Hormone-related symptom scales were coded 0-4 with increasing scores indicating more severe symptoms; BCIA scores were centered at 0 (no impact), with values ranging from −2 (very negative impact) to +2 (very positive impact); Fear of recurrence was coded 5-25 with higher scores indicating higher fear of recurrence.

In the fully adjusted model, race/ethnicity was related to the mental health component score. Black women reported better mental health than White women (p=0.06), whereas Hispanic women reported poorer mental health than White women (p=0.05). The variables that were found to be significant in the unadjusted model were still significantly related to the mental health component score in the adjusted model. More severe cognitive/mood symptoms and greater fear of recurrence were associated with poorer mental health (both p<0.01). Less negative impact of cancer on the social/emotional domain was related to better mental health (p<0.01). Short- and long-term fatigue were significantly related to poorer mental health in both unadjusted and adjusted analyses (both p<0.01 for long-term fatigue; p=0.01 and <0.01 for short-term fatigue). Self-reports of current lymphedema were positively and significantly related to mental health summary score in the unadjusted analysis (p<0.01), but were only borderline significantly related to mental health summary scores in the adjusted analyses (p=0.06).

DISCUSSION

These data suggest that women who are surviving breast cancer for over two years are doing relatively well. The values for the eight scales of the SF-36 were somewhat lower than population norms, but not in all areas.24 The clinical significance of this magnitude of decrease is debatable and is likely to represent meaningful problems for some women and insignificant changes for others, depending on resilience and other complicating factors in a given woman's life. In general, however, these results show that women without recurrent or second primary cancers are generally able to recover from the diagnosis and treatment experience and continue with their lives. These findings are supported by recent studies on long-term survivor functioning.1-3,5

The demographic associations identify demographic subgroups of women who report poorer physical and mental functioning. One possible explanation for the poorer physical functioning in Black women might be that Black women are diagnosed at later stages, and later stage of diagnosis is related to different, more invasive treatment options and possibly more morbidity. In our data, Black women were more likely to be diagnosed at a later stage (data not shown) and were more likely to have lymphedema symptoms that would likely decrease their physical functioning (data not shown). However, we controlled for disease stage and included lymphedema in the adjusted models. There could be an additional factor such as increased spirituality, social support, or better post-traumatic growth that may account for both fewer symptoms and higher mental health scores in Black women.

One explanation for differences between Black women and others could be differences in comorbid conditions. Post-hoc analyses were conducted using both the number and severity of breast cancer-related comorbid conditions, (eg, pulmonary disease and other complications of surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation). Black women did not differ from other groups of women on either of these measures, making comorbidity differences an unlikely explanation for differences in outcomes in this sample. In adjusted models, we see that the most consistent correlates of long-term mental health and physical functioning are fear of recurrence, the impact of cancer on social and emotional life, and fatigue; all symptoms that continue to be reported in long-term survivor groups.

It is interesting that current lymphedema was related to higher levels of mental health summary scores. The literature (e.g., 3) has shown the inverse relationship: persistent lymphedema is related to poorer mental health outcomes. We conducted a post-hoc analysis to identify possible explanations for the unusual relationship that we found. Black women had higher mental health summary scores, as shown previously in Table 3. In our post-hoc analyses, Black women accounted for almost half (46.7%) of the participants reporting current lymphedema. Because of the higher frequency of Black women in the current lymphedema group, combined with higher reported mental health summary scores, the mean for the entire group may have been increased. However, the adjusted models should have taken this into account.

This study has several strengths. One is to include women from a multiethnic sample with a broad range of socioeconomic levels. Many survivorship studies have focused on small samples consisting primarily of White women. In these data we were able to compare women from different ethnic groups and women at differing levels of education and employment. Documenting demographic differences is important as we move from clinical to population-based approaches when studying cancer patients into survivorship. Another strength of this study is the use of previously developed and widely used measures, allowing for comparisons to other studies.

This study has several features that may limit the generalizability of the data. A higher proportion of women who completed the QOL follow-up assessments were White, more educated, and diagnosed at an earlier stage. However, participation was still relatively high due to the intensive follow-up procedures, and therefore we have confidence that the data from the follow-up do not show strong bias in this regard. Ethnic comparisons are not based on women equally recruited across sites, and therefore we cannot completely rule out the idea that race differences are due to center differences as much as differences among race or ethnic groups. Multiethnic samples recruited in the same ways from the same sites will address this question. Constant loss to the multiple procedures and follow-up efforts in this study resulted in a sample that is not fully generalizable to any population of cancer survivors. While this is somewhat less of a problem in the present sample, compared with other samples, one should keep this in mind when interpreting the data patterns. Finally, the study had measurement constraints of follow-up timing and survey length that resulted from the need for coordination across three distant sites.

Overall, these data indicate that race/ethnicity and socioeconomic factors are important determinants of QOL in long term survivors. The final regression models explained a large amount of variance in QOL, 38% and 41% of the variance in physical and mental scores, respectively. Racial/ethnic and socioeconomic variables remained significant in these models after adjustment. These data suggest that race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status represent health disparities that are important for breast cancer survivors. Given the relative importance of these demographic variables on functioning, future studies should address interventions to reduce negative functioning in these groups.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript presents original data from our study. A portion of these data were presented at the Cancer Survivorship Pathways to Health meeting of the National Cancer Institute, June 2004. This research was supported by research contracts from the National Cancer Institute (N01-CN-75036-20, N01-CN-05228, N01-PC-67010) and by a training grant from the National Cancer Institute (R25 CA92408)

REFERENCES

- 1.Ganz PA, Desmond KA, Leedham B, et al. Quality of life in long-term, disease-free survivors of breast cancer: a follow-up study. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2002;94:39–49. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giedzinska AS, Meyerowitz BE, Ganz PA, et al. Health-related quality of life in a multiethnic sample of breast cancer survivors. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2004;28:39–51. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2801_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kornblith AB, Ligibel J. Psychosocial and sexual functioning of survivors of breast cancer. Seminars in Oncology. 2003;30:799–813. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2003.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ganz PA, Rowland JH, Meyerowitz BE, et al. Impact of different adjuvant therapy strategies on quality of life in breast cancer survivors. Recent Results in Cancer Research. 1998;152:396–411. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-45769-2_38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ganz PA, Rowland JH, Desmond K, et al. Life after breast cancer: understanding women's health-related quality of life and sexual functioning. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1998;16:501–14. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.2.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bower JE, Ganz PA, Desmond KA, et al. Fatigue in long-term breast carcinoma survivors: a longitudinal investigation. Cancer. 2006;106:751–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adler NE, Newman K. Socioeconomic disparities in health: pathways and policies. Inequality in education, income, and occupation exacerbates the gaps between the health “haves” and “have-nots.”. Health Affairs (Millwood) 2002;21:60–76. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.2.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adler NE. Community preventive services. Do we know what we need to know to improve health and reduce disparities? American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2003;24:10–1. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00649-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rietman JS, Dijkstra PU, Hoekstra HJ, et al. Late morbidity after treatment of breast cancer in relation to daily activities and quality of life: a systematic review. European Journal of Surgical Oncology. 2003;29:229–38. doi: 10.1053/ejso.2002.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bower JE, Ganz PA, Desmond KA, et al. Fatigue in breast cancer survivors: occurrence, correlates, and impact on quality of life. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2000;18:743–53. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.4.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andersen MR, Peacock S, Nelson J, et al. Worry about ovarian cancer risk and use of ovarian cancer screening by women at risk for ovarian cancer. Gynecologic Oncology. 2002;85:3–8. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2001.6556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Irwin ML, Tworoger SS, Yasui Y, et al. Influence of demographic, physiologic, and psychosocial variables on adherence to a yearlong moderate-intensity exercise trial in postmenopausal women. Preventive Medicine. 2004;39:1080–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patel AV, Press MF, Meeske K, et al. Lifetime recreational exercise activity and risk of breast carcinoma in situ. Cancer. 2003;98:2161–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meeske K, Press M, Patel A, et al. Impact of reproductive factors and lactation on breast carcinoma in situ risk. International Journal of Cancer. 2004;110:102–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marchbanks PA, McDonald JA, Wilson HG, et al. The NICHD Women's Contraceptive and Reproductive Experiences Study: methods and operational results. Annals of Epidemiology. 2002;12:213–21. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(01)00274-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marchbanks PA, McDonald JA, Wilson HG, et al. Oral contraceptives and the risk of breast cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;346:2025–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hays RD, Sherbourne CD, Mazel RM. The RAND 36-Item Health Survey 1.0. Health Economics. 1993;2:217–27. doi: 10.1002/hec.4730020305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ware JE., Jr . The SF-36 health survey, in Spilker B (ed): Quality of life and pharmacoeconomics in clinical trials. 2nd ed. Lippincott-Raven; Philadelphia: 1996. pp. 337–45. ed 2nd. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alfano CM, McGregor BA, Kuniyuki A, et al. Psychometric properties of a tool for measuring hormone-related symptoms in breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology. doi: 10.1002/pon.1033. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alfano CM, McGregor BA, Kuniyuki A, et al. Psychometric evaluation of the Brief Cancer Impact Scale among breast cancer survivors. Oncology. doi: 10.1159/000094320. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Northouse LL. Mastectomy patients and the fear of cancer recurrence. Cancer Nursing. 1981;4:213–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus User's Guide. Muthen and Muthen; Los Angeles, CA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ware JE. SF 36 health survey: manual and interpretation guide. The Health Institute New England Medical Center; Boston: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yost KJ, Haan MN, Levine RA, et al. Comparing SF-36 scores across three groups of women with different health profiles. Quality of Life Research. 2005;14:1251–61. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-6673-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]