Abstract

Malaria is an infectious disease caused by protozoan parasites of the genus Plasmodium. The most virulent form of the disease is caused by P. falciparum which infects hundreds of millions of people and is responsible for the deaths of 1 to 2 million individuals each year. An essential part of the parasitic process is the remodeling of the red blood cell membrane and its protein constituents to permit a higher flux of nutrients and waste products into or away from the intracellular parasite. Much of this increased permeability is due to a single type of broad specificity channel variously called the new permeation pathway (NPP), the nutrient channel, and the Plasmodial surface anion channel (PSAC). This channel is permeable to a range of low molecular weight solutes both charged and uncharged, with a strong preference for anions. Drugs such as furosemide that are known to block anion-selective channels inhibit PSAC. In this study we have investigated a dye known as benzothiocarboxypurine, BCP, which had been studied as a possible diagnostic aid given its selective uptake by P. falciparum infected red cells. We found that the dye enters parasitized red cells via the furosemide-inhibitable PSAC, forms a brightly fluorescent complex with parasite nucleic acids, and is selectively toxic to infected cells. Our study describes an antimalarial agent that exploits the altered permeability of Plasmodium-infected red cells as a means to killing the parasite and highlights a chemical reagent that may prove useful in high throughput screening of compounds for inhibitors of the channel.

Keywords: Plasmodium falciparum, malaria, chemotherapy, nutrient channel, PUR-1, benzothiocarboxypurine, confocal fluorescence microscopy, parasite

Introduction

Malaria is a primary health concern in most of the tropical areas of the world today. The effectiveness of standard antimalarial drugs, such as chloroquine and quinine, has been steadily declining with the emergence and spread of increased resistance in the Plasmodium parasites that cause the disease (Cowman, 2001, Olliaro, 2001, Wellems and Plowe, 2001). Given that the hope for a long-lasting vaccine against malaria is as yet unfulfilled (Chiang, et al., 2006, Greenwood, et al., 2005, Malkin, et al., 2006), it appears that control of the disease must rely on chemotherapy in the foreseeable future. Hence, there is an urgent need for development of novel therapeutic approaches, such as the one described here, for treatment of malaria.

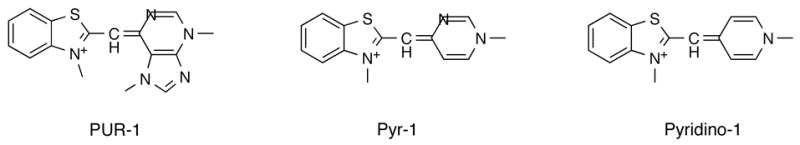

In this report we describe results with a fluorescent dye, previously referred to as benzothiocarboxypurine (BCP) (Hunt Cooke, et al., 1992, Hunt Cooke, et al., 1993, Makler, et al., 1991) and PUR-1 (Lee and Mize, 1990). The chemical name of the compound is 3-methyl-2-[(3,7-dimethyl-6-purinylidene)-methyl]-benzothiazolium and its structure is presented in Figure 1. To avoid ambiguity with the past literature we will use the acronym PUR-1 in reference to this material. Makler and colleagues were first to report the use and utility of this fluorescent dye in diagnosis of malaria. The basis of their diagnostic procedure rested upon the observation that the dye does not penetrate viable white blood cells but does stain the nucleic acids of viable Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes. The nature of the fluorescence exhibited by the stained cells was of an intense apple green to yellow color that could be easily viewed by fluorescence microscopy for diagnostic purposes.

Figure 1.

Structure of PUR-1, also known as benzothiocarboxypurine (BCP), and two structural analogs, Pyr-1 (Pyrimidino-1) and Pyridino-1.

The apparent selective uptake of PUR-1 by infected red blood cells and its strong affinity for parasite nucleic acids led us to begin an investigation of its potential as an antimalarial agent. Herein we confirm the prior experience with this compound, including the selective uptake phenomenon, and present evidence that PUR-1 and its analogs represent an exciting lead in our quest to discover new antimalarial and antiparasitic drugs.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and Solutions

Chemicals and solvents needed for synthesis of PUR-1 were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, Missouri, USA). Cell culture media, medium supplements, and Histopaque (1.119 gm/ml; needed for processing blood) were obtained from Sigma. Radiolabeled ethanolamine was obtained from American Radiolabeled Chemicals (St. Louis, Missouri, USA).

Chemical synthesis procedures

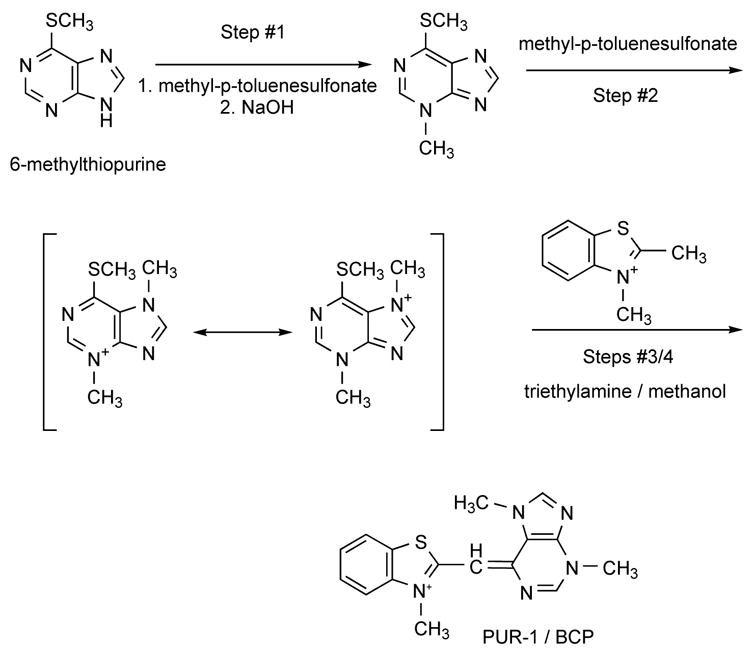

PUR-1 was synthesized in the following manner (Figure 2), patterned after that of Lee and Mize (Lee and Mize, 1990):

Figure 2.

Chemical synthesis of PUR-1.

Step #1

A round bottomed flask was charged with 3 gm of 6-methylthiopurine, 3.7 gm of methyl-p-toluenesulfonate and 6 ml of dimethylformamide. The mixture was heated in an oil bath at 110°C for 2.5 hrs until it became a clear yellowish solution. After cooling, 20 ml of water was added and the solution was then extracted with three 20 ml portions of ether to remove unreacted starting material. The combined ethereal portions were back-extracted with 20 ml of water; the aqueous layer was washed with 20 ml ether and then combined with the initial aqueous solution. The solution then was made basic to pH 13 by addition of KOH. After several minutes, a white crystalline solid precipitated from solution. The solid was filtered and washed with water and air-dried. The white crystals were identified as 3-methyl-6-(methylthio)-purine (“I”).

Step #2

To prepare 3,7-dimethyl-6-(methylthio)-purine p-toluenesulfonate, a flask was charged with 0.8gm of “I” and with 0.95gm of methyl-p-toluenesulfonate. The mixture was briefly heated in an oil bath at 100°C. The homogeneous solution was cooled and then washed with acetone and ether. After washing, the reaction mixture appeared as an amorphous white solid. The organic washes were combined and a white crystalline solid formed. This material was combined with the amorphous solid and was used without purification in the synthesis of PUR-1.

Steps 3 and 4

To prepare 2,3-dimethylbenzothiazolium p-toluenesulfonate, 1 eq. of methyl-p-toluenesulfonate and 1 eq. of 2-methylbenzothiazole were combined in a round bottomed flask equipped with a metal stirring bar and reflux condenser. The flask was heated to 80°C in an oil bath for 16 hrs. The light-green solid was cooled, crushed, washed with acetone and filtered. Finally, to prepare PUR-1, a round bottomed flask, equipped with a magnetic stirring bar and condenser, was charged with 1.28 gm of the 2,3-dimethyl-benzothiazolium, 1.5 gm of crude 3,7-dimethyl-6-(methylthio)purinium p-toluenesulfonate, 20 ml of methanol and 0.5ml of triethylamine. The mixture was refluxed for about 45 minutes, producing a red solution containing a yellow solid. The material was cooled, filtered, and washed with methanol and ether resulting in a yellow-orange solid that was identified as PUR-1 by 1H-nmr and by elemental analysis. [Analogous methods were used to prepare Pyr-1 and Pyridino-1.].

Cultures

Three different laboratory strains of P. falciparum (D6, W2, and F-86) were cultured in human erythrocytes by standard methods under a low oxygen atmosphere (5% O2, 5% CO2, 90% N2) in an environmental chamber (Trager and Jensen, 1976). The chloroquine-susceptible clone D6, the multidrug-resistant clone W2 and the chloroquine-resistant strain, FCR-3/Gambia subline F-86 (Jensen and Trager, 1978), were obtained from the MR4 repository of the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). The culture medium was RPMI 1640, supplemented with 25 mM Hepes, 25 mg/liter gentamicin sulfate, 45 mg/liter hypoxanthine, 10 mM glucose, 2 mM glutamine, and 10% fresh human serum (complete medium). The parasites were maintained in fresh Group A+ human erythrocytes suspended at a 2% hematocrit in complete medium at 37°C. Stock cultures were sub-passaged every 3 to 4 days by transfer of infected red cells to a flask containing complete medium and uninfected erythrocytes. Where indicated, parasitized red blood cells were synchronized to ring form trophozoites by two cycles of sorbitol lysis (Lambros and Vanderberg, 1979).

Growth inhibition assays

P. falciparum growth was assessed by measuring the incorporation of radiolabeled ethanolamine into parasite lipids in complete medium (Kelly, et al., 2002). Aliquots of stock solutions of PUR-1 in DMSO were placed in the wells of flat bottomed cell culture plates (Nunc), under sterile conditions, to render final concentrations of 1 nM to 10 μM PUR-1 after the addition of either control (uninfected) or parasitized red cell suspensions in culture medium. DMSO concentrations did not exceed 0.1% (vol./vol.) under the experimental conditions. The plates were transferred to a gas-tight environmental chamber flushed with the low oxygen gas mixture, and incubated at 37°C for 48hrs. [3H]-Ethanolamine (50 Ci/mmol, 1 μCi,) was added after 48 hr, and the experiments were terminated after 72 hr of incubation by collecting the cells onto glass fiber filters with a semiautomated Tomtec (Orange, CT) 96-well plate harvester. [3H]-Ethanolamine uptake was quantitated by scintillation counting of the filters using a Wallac (Gaithersburg, MD) 1205 Betaplate counter. The concentration of PUR-1 giving 50% inhibition of label incorporation (IC50) relative to drug-free controls was calculated by nonlinear regression analysis of the semi-logarithmic dose-response curve using PRISM software. Each IC50 value (± standard deviation) was derived from the average of at least 3 separate experiments, each performed in duplicate.

Growth inhibition assays for determination of cytotoxicity against mammalian cells in culture were performed as described in the results section.

Confocal Analysis

PUR-1 was dissolved in ethanol at a concentration of 10 mM and diluted to 5μM in pre-warmed complete medium. Equal volumes of the 5μM PUR-1 solution and of parasitized red blood cells (from the laboratory’s stock culture: 2% hematocrit, ≈10–12% parasitemia, strain D6) were mixed. Imaging began immediately after mixing. Laser scanning confocal fluorescence microscopy was employed to visualize the PUR-1-stained infected red blood cells. Excitation was at a wavelength of 476nm and emission was collected in the range of 500 to 550nm. Live recordings were made of the cells which had been placed in a LabTek chamber slide (Nunc) for viewing at room temperature. Images from the confocal microscope were exported as single-image files in the PSD format (Photoshop, Adobe, Mountain View, California, USA). Photoshop software was then used to combine and overlay the transmitted image and fluorescence image of a typical field of view.

Results

PUR-1 inhibits P. falciparum growth in vitro

Parasite growth was assessed in all three strains by measuring the incorporation of [3H]-ethanolamine in asynchronous cultures and in cultures initiated with synchronous early trophozoite-stage parasites. The effects of PUR-1 were tested against a chloroquine-sensitive strain (D6) and two chloroquine-resistant strains (FCR-3 and W2) of P. falciparum . PUR-1 inhibited parasite growth with IC50 values between 20 and 30nM, irrespective of the chloroquine sensitivity of the strain (Table 1).

Table 1.

In vitro antimalarial activity and cytotoxicity of PUR-1.*

| Parasite strain or cell type | Plasmodium falciparum strain | K562 cells | J774 cells | JY cells | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D6 | FCR-3/ subline F-86 | W2 | ||||

| Drug resistance | Mildly resistant to mefloquine | Intermediate resistance to chloroquine, sensitive to pyrimethamine | Resistant to chloroquine, quinine, pyrimethamine, sulfadoxine & cycloguanil | NA | NA | NA |

| IC50 value | 24.6±4 nM | 23.7±3 nM | 26.2±5nM | ≈6,500nM | ≈8,000nM | ≈5,900nM |

IC50 values are the mean ± standard deviation of three determinations, each in duplicate.

PUR-1 toxicity toward mammalian cell lines

The effect of PUR-1 on mammalian cells in vitro was also examined. For these experiments, the EBV-transformed JY human B lymphoblast cell line (Fingeroth, et al., 1984) was grown in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and antibiotics in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air at 37°C. The human erythroblast line, K562 (Koeffler and Golde, 1980), was included for comparison and it was cultivated in the same medium as indicated for the JY line. The cells were exposed to various concentrations of PUR-1 (0 to 50μM) for 72 hours prior to determining cell density and viability. In summary, evidence of PUR-1 cytotoxicity was present in both cell lines at μmolar concentrations of the drug (Table 1). The IC50 values for PUR-1 vs. JY cells and K562 cells in our system were estimated as 5.9μM and 6.5μM, respectively. The cytocidal effect of PUR-1 against the murine macrophage-like cell line, J774 (Sakurai, et al., 1986), was also investigated and gave similar results (Table 1). Compared to the potency of the drug against Plasmodium-infected red cells, the cytotoxicities directed toward the mammalian cell lines were at least two orders of magnitude higher.

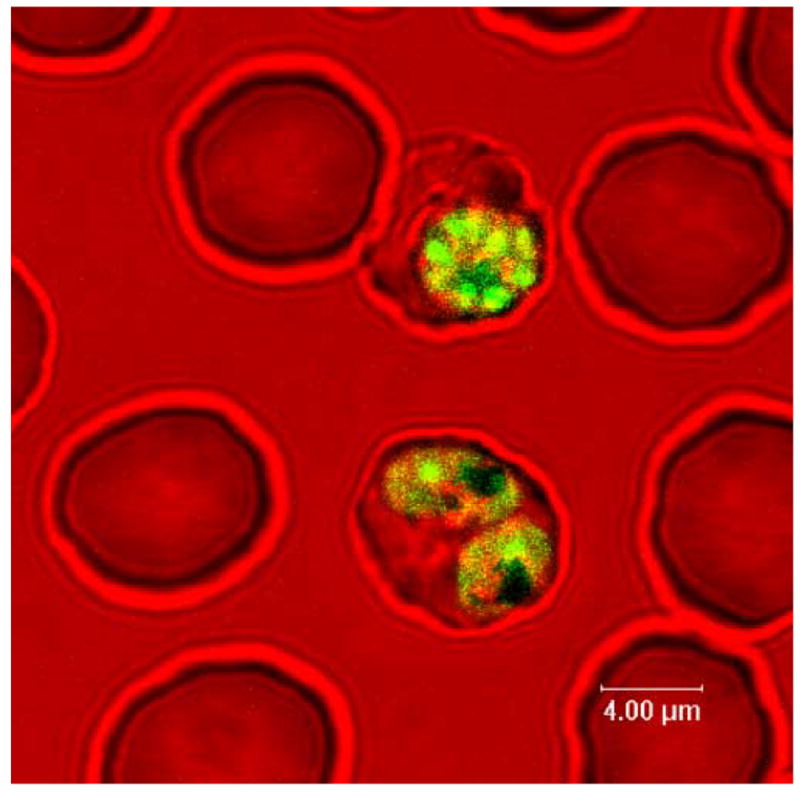

Confocal imaging of Plasmodium falciparum infected red cells treated with PUR-1

Makler, Hinrichs, and coworkers first reported that viable Plasmodium-infected red cells exposed to PUR-1 exhibited fluorescence while similarly treated uninfected blood cells did not, thereby forming the basis of a malaria diagnostic procedure. The images presented in their original publication were taken at an insufficient magnification to allow the identification of the subcellular structures that had been stained by the dye. We therefore conducted laser scanning confocal fluorescence microscopy to visualize viable PUR-1-stained P. falciparum infected red blood cells suspended in a Labtek chamber slide. The complex between the dye and nucleic acids is excitable in the range of 460 to 480nm and with a maximum emission in the range of 480 to 550nm. The 476nm line of an argon laser effected excitation of the dye on the confocal fluorescence microscope, and emission was collected from 500–550nm. Shown in Figure 3 is the transmitted image of normal red blood cells in the presence of two parasitized red cells exposed to PUR-1 for 5 minutes. Notice that only the infected cells stained with the dye thus confirming the earlier observations of Makler and Hinrichs. Importantly, one of the stained cells appears to be doubly infected and at the trophozoite stage of development exhibiting large pigment granules. The other infected cell is at a later stage of development with clearly delineated nuclear regions of developing merozoites. It is noteworthy that nearly all asexual forms of the parasite stain intensely with PUR-1, with the exception of the early rings. In an experiment performed in parallel, we also processed whole blood and purified white blood cells in an analogous manner and did not observe any staining of these cell populations by PUR-1.

Figure 3.

Selective staining of PRBC (and not normal red cells) by PUR-1, as visualized by confocal fluorescence microscopy.

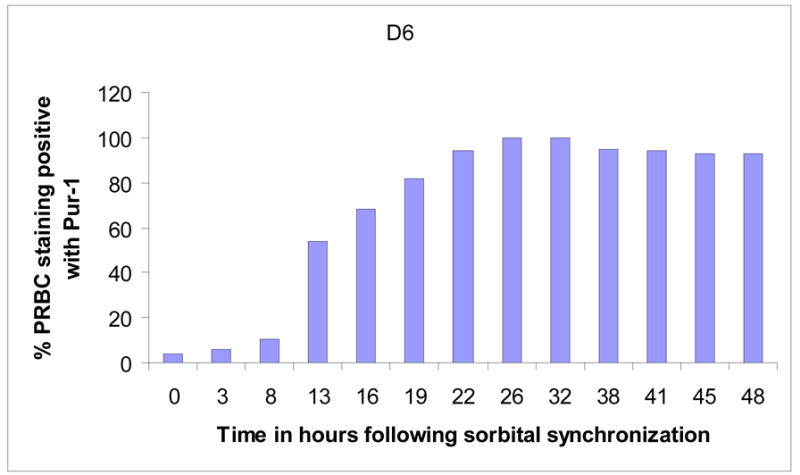

Stage-dependent uptake of PUR-1 by Plasmodium falciparum-infected red blood cells

Since PRBC become fluorescent upon uptake of PUR-1 and complexation of the dye to nucleic acids (RNA and DNA), we set out to investigate whether the drug is transported in a stage-dependent manner. The experiment was performed with the aid of a Becton-Dickinson FACS Scan flow cytometer using the fluorescein channel. Parasitized red cells were synchronized to the early ring stage by two cycles of sorbitol lysis (Lambros and Vanderberg, 1979) separated by 4 hours and then cultivated in complete medium. Normal uninfected red blood cells served as controls for fluorescence gating of unstained and stained cell populations. Cultures of normal and synchronous infected red cells were incubated at 37ºC in an atmosphere of 5% O2, 5% CO2, and 90% N2. At various intervals, 100μl of the cell suspension was removed and mixed with an equal volume of 2.5μM PUR-1 and incubated for an additional 5 minutes before cytofluorographic analysis. At each interval, a microscopic analysis of the parasite culture was made to assess percent parasitemia and the stage of parasite development. A Giemsa stained preparation at the beginning of the incubation period showed that ≈16% of the cells were infected with ring-form parasites. As shown in Figure 4, PUR-1 staining of infected red cells was negligible throughout the first 12 hrs of the experiment. In the interval from 8 to 13 hours of incubation there was a significant increase in the number of PRBC staining with the dye, increasing from 8.1% to ≈55%. By the 19 hr time point ≈80% of the parasitized cell population gated positive for fluorescence in the presence of PUR-1. After 22 to 26 hrs in culture following ring stage synchronization, and corresponding to the early to mid-trophozoite stage of parasite development, essentially all of the parasitized red cells stained positive with the fluorescent benzylthiazolium dye.

Figure 4.

Stage-dependent staining of synchronous PRBC by PUR-1.

Inhibition of PUR-1 staining by furosemide

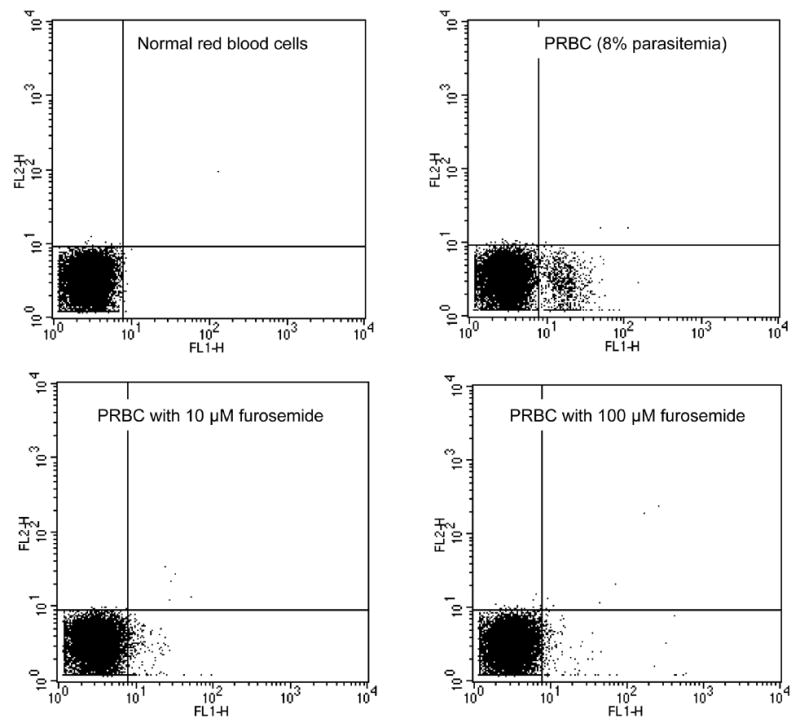

Our studies confirm the selectively permeable nature of P. falciparum infected red cells to PUR-1. Confocal fluorescence microscopy demonstrates that the drug rapidly enters infected cells and binds to nucleic acids, presumably stifling parasite DNA replication and RNA transcription. We initially considered the possibility that PUR-1 is actively transported into parasite infected red blood cells via a purine transporter, perhaps the PfNT1 nucleoside/nucleobase transporter (Carter, et al., 2000, Carter, et al., 2001, Parker, et al., 2000, Rager, et al., 2001). However, we were unable to demonstrate any interference of PUR-1 staining by numerous purine and pyrimidine nucleobases and nucleosides. We then tested furosemide and the possibility that PUR-1 gains entry into PRBC via the parasite-induced, chloride ion dependent, new permeation pathway (NPP). Briefly, PRBC, taken from a stock culture, were washed and suspended in HEPES-buffered saline (125mM NaCl, 5mM KCl, 25mM HEPES, 5mM glucose, pH 7.4). Normal red blood cells (NRBC) were treated in the same manner to provide a reference control. NRBC and PRBC were then stained with PUR-1 (5μM) for 2 minutes in the presence or absence of increasing concentrations of furosemide, the anion channel blocker (Kirk, et al., 1994). As shown in Figure 5, low concentrations of furosemide (10 and 100μM) antagonize staining of PRBC by PUR-1. An interesting structure-activity profile emerges from similar studies performed with PUR-1 analogs, Pyr-1 and Pyridino-1. While both of these compounds enter PRBC and stain parasite nucleic acids, entry of Pyr-1 or Pyridino-1 is not perturbed by furosemide. The in vitro antiplasmodial activity of Pyr-1 (IC50 ≈250nM) is ≈10 times less than the parent molecule while Pyridino-1 is slightly more potent (IC50 ≈10nM). Taken together, these data seem to point to the critical nature of the purine ring on the specificity of the furosemide inhibitable channel.

Figure 5.

Inhibition of PUR-1 staining of PRBC by the anion selective channel blocker, furosemide. Top left, normal red cells stained with PUR-1; top right, PRBC stained with PUR-1 (asynchronous parasitemia of ≈8%); bottom left, PRBC stained with PUR-1 in the presence of 10μM furosemide (1.51% staining); and PRBC stained with PUR-1 in the presence of 100μM furosemide (1.1% staining).

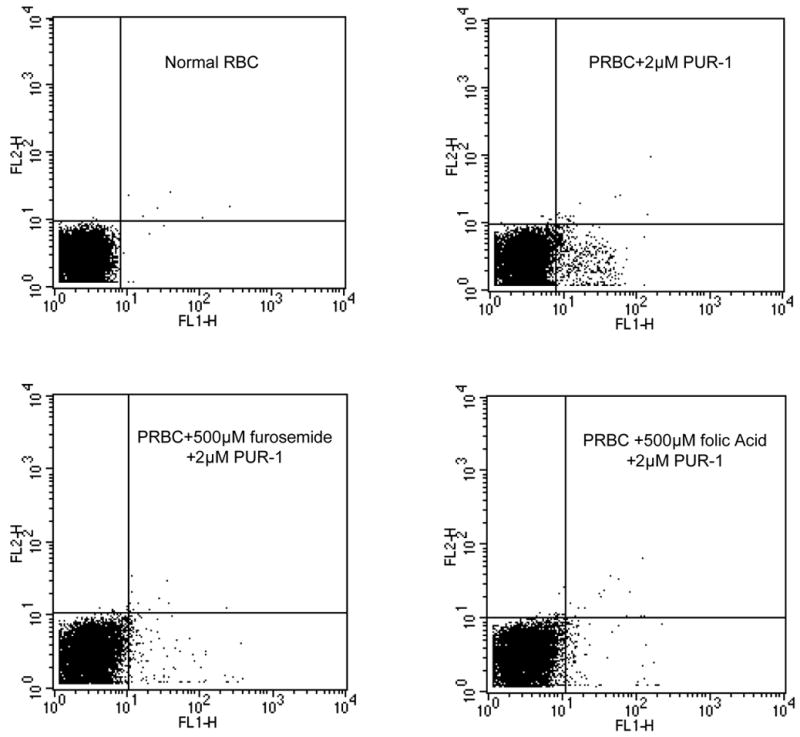

Based on these findings we began to explore further the structural features of PUR-1 that are important for entry into parasitized red cells via the PSAC channel. We considered the findings of Ward and coworkers who have suggested that exogenous folates gain entry into PRBC via the broad specificity anion dependent channel (Nzila, et al., 2003). Considering that the heterocyclic purine ring in PUR-1 may be recognized as a pterin-like heterocycle in this biological system, we set up an experiment to test the ability of folic acid to interfere with PUR-1 staining of PRBC. As shown in Figure 6, our data show that folic acid antagonizes PUR-1 uptake and staining of PRBC which is consistent with the notion that the channel may function in salvage of folic acid from the bloodstream of the human host. Importantly, the methods employed in our study cannot distinguish between folic acid and PUR-1 competition for uptake through the PSAC channel on the outer membrane of the infected cell vs. competition for uptake across a carrier protein located on the parasite plasma membrane. However, taken together with the findings of Nzila et al. (Nzila, et al., 2003) and Wang et al. (Wang, et al., 1999) it seems reasonable to believe that a selective inhibitor of the NPP will block uptake of exogenous folic acid from the bloodstream and function synergistically with selective inhibitors of parasite dihydrofolate reductase, such as WR99210 (Canfield, et al., 1993, Kinyanjui, et al., 1999) and “biguanide” prodrugs of the Jacobus series (Jensen, et al., 2001).

Figure 6.

Inhibition of PUR-1 staining of PRBC by folic acid. Conditions were as described above for PUR-1 and furosemide combinations. Top left, normal red cells stained with PUR-1; top right, PRBC stained with PUR-1 (asynchronous parasitemia of 5.93% staining positive); bottom left, PRBC stained with PUR-1 in the presence of 500μM furosemide (1.53% staining); and PRBC stained with PUR-1 in the presence of 500μM folic acid (1.43% staining).

Discussion

PUR-1 is a selectively potent inhibitor of parasite growth. Our investigation indicates that this compound is toxic to parasites in the mid and latter stages of erythrocytic development. The compound is equally active against strains of P. falciparum that display a range of sensitivities to the 4-aminoquinolines, including the multidrug-resistant W2 clone. While PUR-1 inhibits parasite growth with IC50 values in the 20–30nM range in a 72 hr assay, its effects on the proliferation of several different mammalian cell lines were not evident until concentrations were increased to the micromolar level.

Our studies confirm the selectively permeable nature of P. falciparum infected red cells to PUR-1. Confocal fluorescence microscopy demonstrates that the drug rapidly enters infected cells and binds to nucleic acids, presumably stifling parasite DNA replication and RNA transcription. A working hypothesis drawn from the accumulated evidence is that PUR-1 is actively transported into parasite infected red blood cells via the NPP/PSAC. Desai et al. (Desai, et al., 2000, Desai, et al., 1993, Desai and Rosenberg, 1997) has described the NPP as a chloride ion dependent nutrient permeable channel which allows the movement of organic and inorganic ions across the plasma membrane of infected red blood cells. Thus, it is known that glutamate, pantothenate (vitamin B5), lactate, choline, and chloride ion all pass through the channel and that the channel exhibits significant permeability to mono-cations as well (Bray, et al., 2003). The molecular identity of the channel remains a mystery and there is some controversy as to whether and if the channel is composed of proteins derived from the parasite or simply remodeled from host proteins (Kirk, 2000). But despite this uncertainty there is a clear recognition that the channel is an attractive target for new drug design (Alkhalil, et al., 2004, Desai, 2004, Ginsburg and Stein, 2005, Kirk, 2004, Lisk, et al., 2006). It is hoped that the results reported here will aid in the effort to develop pharmacologic means to block or subvert the channel, leading to discovery of novel antimalarial agents.

Acknowledgments

We want to acknowledge financial support from the Merit Review Program of the Department of Veterans Affairs, the US National Institutes of Health (grant #AI051509-01A1), and the US Department of Defense PRMRP program (DAMD contract #17-03-1-0030). We also gratefully acknowledge financial contributions by the Medical Research Foundation of Oregon and the Collins Medical Trust of Oregon. TPB and MOA were recipients of summer research fellowships from the Portland VA Research Foundation.

Abbreviations

- BCP

benzothiocarboxypurine

- IC50

50% inhibitory concentration

- NPP

nutrient permeable pathway

- NRBC

normal red blood cells

- PSAC

Plasmodial surface anion channel

- PRBC

Plasmodium infected red blood cells

- PUR-1

3-methyl-2-[(3,7-dimethyl-6-purinylidene)-methyl]-benzothiazolium

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Alkhalil A, Cohn JV, Wagner MA, Cabrera JS, Rajapandi T, Desai SA. Plasmodium falciparum likely encodes the principal anion channel on infected human erythrocytes. Blood. 2004;104:4279–4286. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-05-2047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bray PG, Barrett MP, Ward SA, de Koning HP. Pentamidine uptake and resistance in pathogenic protozoa: past, present and future. Trends in Parasitology. 2003;19:232–239. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4922(03)00069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Canfield CJ, Milhous WK, Ager AL, Rossan RN, Sweeney TR, Lewis NJ, Jacobus DP. PS-15: a potent, orally active antimalarial from a new class of folic acid antagonists. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1993;49:121–126. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1993.49.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carter NS, Ben Mamoun C, Liu W, Silva EO, Landfear SM, Goldberg DE, Ullman B. Isolation and functional characterization of the PfNT1 nucleoside transporter gene from Plasmodium falciparum. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275:10683–10691. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.14.10683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carter NS, Landfear SM, Ullman B. Nucleoside transporters of parasitic protozoa. Trends in Parasitology. 2001;17:142–145. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4922(00)01806-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chiang PK, Bujnicki JM, Su X, Lanar DE. Malaria: therapy, genes and vaccines. Current Molecular Medicine. 2006;6:309–326. doi: 10.2174/156652406776894545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cowman AF. Functional analysis of drug resistance in Plasmodium falciparum in the post-genomic era. International Journal of Parasitology. 2001;31:871–878. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(01)00201-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Desai SA. Targeting ion channels of Plasmodium falciparum-infected human erythrocytes for antimalarial development. Current Drug Targets: Infectious Disorders. 2004;4:79–86. doi: 10.2174/1568005043480934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Desai SA, Bezrukov SM, Zimmerberg J. A voltage-dependent channel involved in nutrient uptake by red blood cells infected with the malaria parasite. Nature. 2000;406:1001–1005. doi: 10.1038/35023000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Desai SA, Krogstad DJ, McCleskey EW. A nutrient-permeable channel on the intraerythrocytic malaria parasite. Nature. 1993;362:643–646. doi: 10.1038/362643a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Desai SA, Rosenberg RL. Pore size of the malaria parasite's nutrient channel. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences U S A. 1997;94:2045–2049. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fingeroth JD, Weis JJ, Tedder TF, Strominger JL, Biro PA, Fearon DT. Epstein-Barr virus receptor of human B lymphocytes is the C3d receptor CR2. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences U S A. 1984;81:4510–4514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.14.4510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ginsburg H, Stein WD. How many functional transport pathways does Plasmodium falciparum induce in the membrane of its host erythrocyte? Trends in Parasitology. 2005;21:118–121. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greenwood BM, Bojang K, Whitty CJ, Targett GA. Malaria. Lancet. 2005;365:1487–1498. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66420-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hunt Cooke A, Moody AH, Lemon K, Chiodini PL, Horton J. Use of the fluorochrome benzothiocarboxypurine in malaria diagnosis. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1992;86:378. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(92)90228-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hunt Cooke A, Morris-Jones S, Horton J, Greenwood BM, Moody AH, Chiodini PL. Evaluation of benzothiocarboxypurine for malaria diagnosis in an endemic area. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1993;87:549. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(93)90082-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jensen JB, Trager W. Plasmodium falciparum in culture: establishment of additional strains. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1978;27:743–746. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1978.27.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jensen NP, Ager AL, Bliss RA, Canfield CJ, Kotecka BM, Rieckmann KH, Terpinski J, Jacobus DP. Phenoxypropoxybiguanides, prodrugs of DHFR-inhibiting diaminotriazine antimalarials. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2001;44:3925–3931. doi: 10.1021/jm010089z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kelly JX, Winter R, Peyton DH, Hinrichs DJ, Riscoe M. Optimization of xanthones for antimalarial activity: the 3,6-bis-omega-diethylamino-alkoxyxanthone series. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2002;46:144–150. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.1.144-150.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kinyanjui SM, Mberu EK, Winstanley PA, Jacobus DP, Watkins WM. The antimalarial triazine WR99210 and the prodrug PS-15: folate reversal of in vitro activity against Plasmodium falciparum and a non-antifolate mode of action of the prodrug. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1999;60:943–947. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.60.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kirk K. Malaria. Channelling nutrients. Nature. 2000;406:949–951. doi: 10.1038/35023209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kirk K. Channels and transporters as drug targets in the Plasmodium-infected erythrocyte. Acta Trop. 2004;89:285–298. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kirk K, Horner HA, Elford BC, Ellory JC, Newbold CI. Transport of diverse substrates into malaria-infected erythrocytes via a pathway showing functional characteristics of a chloride channel. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269:3339–3347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koeffler HP, Golde DW. Human myeloid leukemia cell lines: a review. Blood. 1980;56:344–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lambros C, Vanderberg JP. Synchronization of Plasmodium falciparum erythrocytic stages in culture. Journal of Parasitology. 1979;65:418–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee L, Mize P. Novel fluorescent dye, United States Patent Office. Becton Dickinson and Company; USA: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lisk G, Kang M, Cohn JV, Desai SA. Specific inhibition of the plasmodial surface anion channel by dantrolene. Eukaryotic Cell. 2006;5:1882–1893. doi: 10.1128/EC.00212-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Makler MT, Ries LK, Ries J, Horton RJ, Hinrichs DJ. Detection of Plasmodium falciparum infection with the fluorescent dye, benzothiocarboxypurine. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1991;44:11–16. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1991.44.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Malkin E, Dubovsky F, Moree M. Progress towards the development of malaria vaccines. Trends in Parasitology. 2006;22:292–295. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nzila A, Mberu E, Bray P, Kokwaro G, Winstanley P, Marsh K, Ward S. Chemosensitization of Plasmodium falciparum by probenecid in vitro. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2003;47:2108–2112. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.7.2108-2112.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olliaro P. Mode of action and mechanisms of resistance for antimalarial drugs. Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2001;89:207–219. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(00)00115-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parker MD, Hyde RJ, Yao SY, McRobert L, Cass CE, Young JD, McConkey GA, Baldwin SA. Identification of a nucleoside/nucleobase transporter from Plasmodium falciparum, a novel target for anti-malarial chemotherapy. Biochemical Journal. 2000;349:67–75. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3490067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rager N, Mamoun CB, Carter NS, Goldberg DE, Ullman B. Localization of the Plasmodium falciparum PfNT1 Nucleoside transporter to the parasite plasma membrane. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276:41095–41099. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107037200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sakurai A, Satomi N, Haranaka K. Macrophage cell line, J774, producing a tumor necrosis factor. Japanese Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1986;56:195–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trager W, Jensen JB. Human malaria parasites in continuous culture. Science. 1976;193:673–675. doi: 10.1126/science.781840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang P, Brobey RK, Horii T, Sims PF, Hyde JE. Utilization of exogenous folate in the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum and its critical role in antifolate drug synergy. Molecular Microbiology. 1999;32:1254–1262. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wellems TE, Plowe CV. Chloroquine-resistant malaria. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2001;184:770–776. doi: 10.1086/322858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]