Abstract

The size of the readily releasable pool (RRP) of vesicles was measured in control conditions and during post-tetanic potentiation (PTP) in a large glutamatergic terminal called the calyx of Held. We measured excitatory postsynaptic currents evoked by a high frequency train of action potentials in slices of 4–11-day-old rats. After a tetanus the cumulative release during such a train was enlarged by approximately 50%, indicating that the size of the RRP was increased. The amount of enhancement depended on the duration and frequency of the tetanus and on the age of the rat. After the tetanus, the size of the RRP decayed more slowly (t1/2= 10 versus 3 min) back to control values than the release probability. This difference was mainly due to a very fast initial decay of the release probability, which had a time constant compatible with an augmentation phase (τ≈ 30 s). The overall decay of PTP at physiological temperature was not different from room temperature, but the increase in release probability (Pr) was restricted to the first minute after the tetanus. Thereafter PTP was dominated by an increase in the size of the RRP. We conclude that due to the short lifetime of the increase in release probability, the contribution of the increase in RRP size during post-tetanic potentiation is more significant at physiological temperature.

Synaptic terminals can increase the release of the number of vesicles per action potential after repetitive stimulation. Release can be enhanced because the release probability (Pr) has become higher or because the number of vesicles available for release, the so-called readily releasable pool (RRP), is larger (Zucker & Regehr, 2002). Both mechanisms have been proposed to be responsible for short-term synaptic plasticity (Stevens & Wesseling, 1999; Rosenmund et al. 2002; Kalkstein & Magleby, 2004; for review see Zucker & Regehr, 2002). Short-term plasticity has been classified based on duration. Post-tetanic potentiation (PTP) has the longest duration and augmentation has a duration intermediate between facilitation and potentiation (Magleby & Zengel, 1976).

The RRP is a functionally defined pool of vesicles that most likely consists of the docked vesicles observed in electron microscopic studies (Schikorski & Stevens, 2001). The size of the RRP has been thoroughly investigated in the calyx of Held synapse, a large glutamatergic nerve terminal originating from the globular bushy cells of the cochlear nucleus. The axons of the bushy cells cross the midline and terminate onto the glycinergic principal cells in the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body (MNTB). During a short high-frequency train of action potentials, excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) in the postsynaptic cell depress. This depression has several causes (Schneggenburger et al. 2002; von Gersdorff & Borst, 2002), of which depletion of synaptic vesicles from the RRP is the most important one at frequencies higher than 100 Hz (Xu & Wu, 2005). Measuring how many vesicles are released during such a train therefore provides an estimate of the RRP size. Depletion of the RRP by high frequency stimulation was confirmed by subsequent depolarizing steps, flash photolysis of caged calcium or hypertonic sucrose application (Schneggenburger et al. 1999; Wu & Borst, 1999; Bollmann et al. 2000; Wu & Wu, 2001). When the size of the RRP is calculated by dividing the cumulative EPSC of a train by the miniature EPSC size, estimates for the size of the RRP at the calyx of Held vary from 600 to 800 vesicles. Larger numbers are obtained by capacitance measurements, deconvolution of EPSCs and quantal analysis (Sakaba & Neher, 2001a; Scheuss & Neher, 2001; Sun & Wu, 2001). Calyx of Held terminals contain around 500 release sites with 2–6 docked vesicles per active zone (Sätzler et al. 2002; Taschenberger et al. 2002). This number of docked vesicles corresponds well with the estimated number of vesicles in the physiologically defined RRP. During an action potential 200 (Borst & Sakmann, 1996) to 400 (Taschenberger et al. 2002) vesicles are released from the terminal, leading to an average Pr of 0.2 per vesicle (Schneggenburger et al. 1999).

In contrast to depression during the tetanus, EPSCs in the principal cells of the MNTB potentiate to around 200% of control after repetitive stimulation. This potentiation of the EPSCs decays back to baseline with a time constant of 1–9 min (Habets & Borst, 2005; Korogod et al. 2005), which defines this form of synaptic plasticity as PTP. The major part of the PTP could be explained by an increase in the Pr of the vesicles in the RRP (Korogod et al. 2005), but we also found a small but significant increase of the size of the RRP (Habets & Borst, 2005). An increase in the RRP has also been observed following application of forskolin, an activator of adenylate cyclase (Sakaba & Neher, 2001b; Kaneko & Takahashi, 2004), but it is unclear under what physiological stimulus conditions the RRP size increases. In this study we measured the RRP size with short trains of action potentials and examined its size before and after tetanic stimulation of different lengths and frequencies.

Methods

Preparation of slices

Animal procedures were in agreement with the guidelines of the animal committee of the Erasmus MC. Wistar rats were decapitated at postnatal day 4–11 (P4–11) and the brainstem was dissected in ice-cold saline containing (mm): 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 3 MgSO4, 0.1 CaCl2, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 0.4 ascorbic acid, 3 myo-inositol, 2 pyruvic acid, 25 d-glucose, 25 NaHCO3 (Merck); pH 7.4 when bubbled with carbogen (95% O2, 5% CO2). Coronal slices of 200 μm were cut with a vibratome (Leica, Bensheim, Germany), while the tissue was submerged in ice-cold oxygenated saline. Slices were transferred to a holding chamber containing artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF), which had the same composition as the slicing solution, except that the concentrations of CaCl2 and MgSO4 were 2 and 1 mm, respectively. Slices were incubated for 30 min at 37°C. Thereafter, they were either kept at room temperature or at 37°C for experiments performed at physiological temperature.

Electrophysiological recordings

For electrophysiological measurements slices were transferred to a recording chamber on an upright microscope (BX-50; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Oxygenated aCSF was continuously perfused over the slice at 2 ml min−1. In most experiments kynurenic acid (Tocris, Bristol, UK) was added to reduce postsynaptic receptor saturation and desensitization. At the concentration range used (2–4 mm), the rapidly dissociating, competitive glutamate receptor antagonist kynurenic acid reduced the EPSCs by 93–96%, indicating that it prevented released glutamate from binding to most of the available AMPA receptors, thus also largely preventing saturation and desensitization (Diamond & Jahr, 1997; Wu & Borst, 1999; Sakaba & Neher, 2001c; Wong et al. 2003). As a result, the paired-pulse ratio at a stimulus interval of 10 ms increased both at room temperature and at physiological temperature. Neurons were visualized with infrared differential interference contrast optics. The axons of the calyces of Held were stimulated (0.1 ms, 0.03–0.5 mA) at the midline by a bipolar electrode (FHC, Inc., Bowdoinham, ME, USA). Cells were selected when extracellular recordings indicated postsynaptic action potential firing (Habets & Borst, 2005). Whole-cell voltage clamp recordings were made with an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Union City, CA, USA) and low-pass (2–10 kHz) filtered with a 4-pole Bessel filter. Signals were digitized at 50 kHz with a Digidata 1320A (Molecular Devices). Pipette solutions contained (mm): 125 K-gluconate, 20 KCl, 10 Na2-phosphocreatine, 4 MgATP, 0.3 Na2GTP, 10 Hepes (Sigma) and 0.5 EGTA. Holding potential for all experiments was −80 mV. Potentials were corrected for a −11 mV junction potential. Series resistance (< 15 MΩ) was electronically compensated by 80–98% with a lag of 5 μs. Cells with a membrane resistance lower than 100 MΩ were rejected from analysis. Data acquisition and analysis was done with pCLAMP (Molecular Devices) or Igor (Wavemetrics, Lake Oswego, OR, USA).

Data analysis

The RRP size was calculated from the sum of the EPSC amplitudes evoked by a train of action potentials with a frequency of 50, 100, 200 or 400 Hz, depending on the maximal frequency at which the terminals fired action potentials without failures. After six EPSCs the depletion and replenishment of vesicles was considered to have reached a steady state and the rest of the cumulative EPSC plot was fitted with a line, which was back-extrapolated to the start of the stimulus train to correct for replenishment during the train (Fig. 1B; Elmqvist & Quastel, 1965; Schneggenburger et al. 1999). This yielded an RRP estimate in nanoamps, which was converted to number of vesicles by dividing it by the mean amplitude of spontaneous release events of the same cell. This method of calculating the RRP size assumes that the RRP can be depleted by high-frequency trains of action potentials, for which experimental evidence has been obtained (e.g. Wu & Borst, 1999). In addition, it assumes that replenishment is constant. Although this assumption is most likely incorrect (e.g. Sakaba & Neher, 2001a), as long as the steady-state component is small, the errors in the estimate of RRP can be expected to be small as well. An estimate of the Pr of the vesicles in the RRP was obtained by dividing the amplitude of the first EPSC of a train by the RRP size. This method assumed that the Pr of vesicles in RRP is homogeneous. Since this assumption is most likely incorrect (e.g. Wu & Borst, 1999), the reported Pr values may overestimate the true release probabilities. The increase in PTP or RRP size was calculated by dividing the difference before and after the tetanus by the pre-tetanus value. Averaged traces were fitted with a bi-exponential function. Processes with a time constant of at most 30 s were regarded as an augmentation phase. The mean pre-tetanus value was subtracted from data plotted on a semilogarithmic axis.

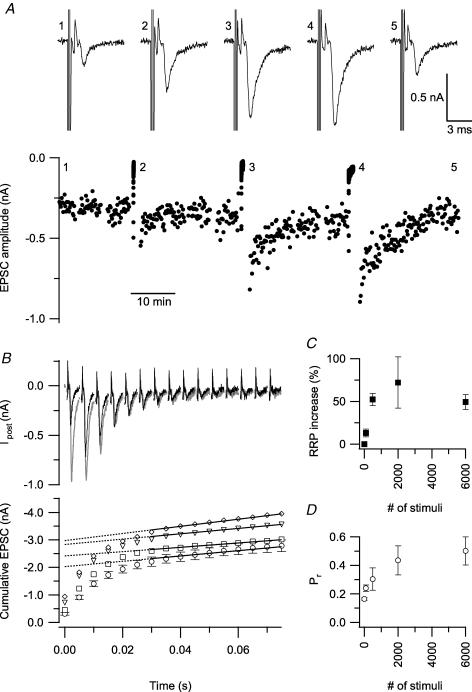

Figure 1. Induction criteria for PTP at 100 Hz.

Axons were stimulated in the midline and EPSCs were recorded in the presence of 2 mm kynurenic acid. The experiments were conducted at RT in slices of 9–10-day-old rats. A, EPSC amplitudes were measured at 0.1 Hz before and after a 100 Hz tetanus of 500, 2000 and 6000 stimuli. Top, example traces, numbers indicate corresponding time point in the bottom graph. B, 6 min before and 1 min after the tetanus the size of the RRP was probed with a short 200 Hz train (25 stimuli). Black traces in the top panel show the first 15 EPSCs in such a train under control conditions, while grey traces show the same, 1 min after a tetanus (6000 stimuli at 100 Hz). Stimulation artefacts were blanked, but prespikes are shown. In the bottom panel the EPSC amplitudes of the 200 Hz trains are plotted cumulatively. The amplitudes after a tetanus of 500 stimuli (□), 2000 (∇) and 6000 (⋄) are shown together with the average of the control trains (○±s.e.m.). An estimate of the RRP size was obtained by extrapolation to the first EPSC of a line that was fitted through the last 18 points in the curve. Traces and amplitudes shown in A and B are from the same experiment. C, the mean (±s.e.m.) increase in the RRP estimate of all experiments (n = 3) is shown as a function of the number of stimuli in the tetanus. The increase without stimulation is set to zero. D, Pr plotted versus the number of stimuli in a 100 Hz tetanus. The mean Pr was calculated by dividing the first EPSC amplitude of a train by the estimate of the RRP.

Spontaneous release events were identified using Clampfit 9.0 (Molecular Devices) by a template made of averaged, manually selected, spontaneous EPSCs.

The amplitude of the prespikes, which could be observed preceding the EPSC in the postsynaptic recordings (Forsythe, 1994), was quantified as the difference between the negative and positive peak. Prespike amplitudes and EPSC amplitudes were divided by their respective mean value before the tetanus (except for Fig. 5C, where the data were normalized to the peak). Data are given as means ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). Statistical comparisons were done using Student's t test, unless otherwise noted.

Figure 5. Temperature dependence of PTP.

A, normalized EPSC amplitudes at RT (n = 9). Axons were stimulated at 0.1 Hz, in the presence of 2 mm kynurenic acid. At t =−1 min, the cell was stimulated with a 100 Hz tetanus of 1 min. Inset shows example currents before (black) and after (grey) the tetanus, with the stimulation artefacts blanked. B, same as in A, only these experiments were done at PT in the presence of 4 mm kynurenic acid (n = 5). C, To compare the decay of PTP at RT (•) to the decay at PT (□), the EPSC values from graphs A and B were normalized to the maximum and plotted on a semilogarithmic scale.

Results

Induction criteria for a change in the RRP

High frequency stimulation in the calyx of Held results in PTP (Habets & Borst, 2005; Korogod et al. 2005). This potentiation results from two different processes, an increase in the RRP and an increase in the probability that a vesicle from this pool is released (Pr). Although the latter has been extensively investigated (Awatramani et al. 2005; Habets & Borst, 2005; Korogod et al. 2005; Lou et al. 2005; Habets & Borst, 2006), the increase in the RRP has received less attention. We started by looking at the induction criteria for an increase in the RRP. We stimulated the axons of the calyces with 100 Hz tetani of different lengths. Before and after this stimulation the EPSC amplitude was measured at 0.1 Hz (Fig. 1A) and an estimate of the size of the RRP and Pr was obtained with a short high frequency train (Fig. 1B). The RRP was enlarged by 13 ± 4.5% (P = 0.81) after 100 stimuli and reached a plateau after 500 stimuli (52 ± 7.1%, P < 0.05, Dunnett's test, Fig. 1C). The increase in Pr after 100 Hz stimulation (Fig. 1D) was similar to our previous measurements after 20 Hz stimulation (Habets & Borst, 2005).

Dynamics of the increase in pool size

In the experiments summarized in Fig. 1, a bi-exponential decay of PTP was present in 3 of 5 cells (as judged by eye, e.g. Fig. 1A). We previously reported a fast and slow component of decay for a subset of experiments following 20 Hz stimulation (Habets & Borst, 2005). To assess the contribution of the increase in RRP size and in Pr to the two phases of decay, we continuously stimulated the terminal with short high frequency trains with an interstimulus interval of 1 min (Fig. 2A and D). These experiments were followed by a second experiment where PTP was quantified in a more standard fashion, by analysing the change in EPSC amplitude during 0.1 Hz stimulation. PTP was more prolonged when the RRP was continuously measured, indicating that these short high frequency trains sustained the potentiation. The size of the RRP estimate in Fig. 2E increased during the baseline period, probably for the same reason. This stimulation protocol enabled us to measure changes in the RRP and changes in Pr simultaneously during the decay of PTP. We found that the Pr was already greatly increased 20 s after a 100 Hz tetanus. The Pr returned to baseline levels with a half-decay time of 3.0 ± 1.4 min (n = 5). The RRP did not reach its maximum until after 1 min, and decreased more slowly to baseline (t1/2= 10 ± 2.4 min, n = 5; Fig. 2E and F). The decay of the mean Pr increase was well described with a double exponential function (τfast≈ 0.5 min, τslow= 11 min; Fig. 2C), which indicates that there might be an augmentation phase shortly after the tetanus. The dynamics of the mean RRP size were fitted with a fast increase (τ≈ 0.3 min) and a slow decrease (τ= 15 min) after the tetanus (Fig. 2C). During RRP depleting trains, the steady state release from terminals depends on replenishment of vesicles (Kushmerick et al. 2006). The amount of depression is therefore inversely proportional to the replenishment rate. Twenty seconds after the tetanus the action potentials in the presynaptic terminals failed in response to high frequency stimulation (Fig. 2A). This hampered a correct analysis of depression and replenishment. At 80 s post-tetanus the amplitudes of the EPSCs at the end of the 200 Hz train were similar to control (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. Dynamics of the RRP during PTP.

The RRP size was continually probed with short trains of action potentials in the presence of 2 mm kynurenic acid. A, the first 10 traces of a train, before (top), 20 s after (middle) and 80 s after a 100 Hz tetanus of 1 min. Asterisks indicate presynaptic action potential failures. Stimulation artefacts were blanked. B, mean amplitudes during the 200 Hz trains of 4 experiments. ○ are from the test train before the tetanus, • are from a test train 80 s after the tetanus. C, semi-logarithmic plot of the Pr (○) and RRP size (▪) after the tetanus. The values correspond to the values in E and F, but are presented as the change from baseline for comparison of the contribution of both decays to PTP. Double exponential functions were fitted through the mean RRP values (n = 5, continuous line) and mean release probabilities (n = 5, dotted line). D, EPSC amplitudes of the experiment with continuous measurement of the RRP before and after the tetanus ends (t = 0). E, time plot of the mean RRP estimates. F, time plot of the release probabilities.

Age and frequency dependence of a change in the number of releasable vesicles

The size of the RRP and the number of active zones increase with age in the calyx of Held (Taschenberger et al. 2002) and PTP is more easily induced in younger rats (Korogod et al. 2005). We therefore compared the contribution of a change in the RRP to PTP at different neonatal ages (Fig. 3). In slices from 4-day-old rats, just after formation of the calyceal synapse (Hoffpauir et al. 2006), PTP could be induced with a 20 Hz tetanus of 5 min. The change in RRP size was maximal at P4 and declined with age until around P10. The age dependence could arise from the more rapid calcium clearance at the older ages (Chuhma & Ohmori, 2001).

Figure 3. Age dependence of the increase in RRP and Pr.

The increases in RRP size (▪) and Pr(○) are plotted for the different ages of the rats. Only experiments with a 20 Hz tetanus of 5 min are shown. The animals used were 4 (n = 2), 6 (n = 2), 7 (n = 13), 8 (n = 7), 9 (n = 7), 10 (n = 3) or 11 (n = 5) days old.

The data in Fig. 3 apply to increases in the RRP induced by a 20 Hz tetanus of 6000 stimuli. PTP at this stimulation frequency is almost completely absent in slices from 10-day-old animals (Fig. 4A and B). Three different stimulation frequencies (20, 50 and 100 Hz) were applied to the afferent fibres of 9–10-day-old rats. Increasing the stimulus frequency resulted in more PTP for this age group. On average the Pr increased from 0.15 ± 0.02 before tetanization to 0.21 (20 Hz, n = 4), 0.25 (50 Hz, n = 2) and 0.35 (100 Hz, n = 9) 1 min after the tetanus (Fig. 4C). The change in RRP size was significantly larger after a 100 Hz tetanus than after a 20 Hz tetanus (Fig. 4D, one-tailed t test, P < 0.01). This indicates that in older animals an increase comparable to the values shown in Fig. 3 for younger ages can be achieved by stimulation at higher frequencies. The increase in Pr was the dominant mechanism of PTP at 1 min after the tetanus for all frequencies tested.

Figure 4. Frequency dependence of PTP.

A, EPSC amplitudes measured in a principal cell from a P10 rat. The cell was tetanized with 6000 stimuli of three different frequencies, as indicated in the top graph by bars. From left to right: 20 Hz, 50 Hz and 100 Hz. B, example traces before (grey) and after (black) the 20 Hz (top), 50 Hz (middle) and 100 Hz (bottom) tetanus. C, mean release probabilities from P9 and P10 slices. PTP was induced with a 20-Hz ○), 50 Hz (□) or 100 Hz (▵) tetanus. D, increase in the size of the RRP for the three different frequencies tested. Experiments were conducted in the presence of kynurenic acid.

PTP at physiological temperature

Experiments on PTP in mammals are often performed at room temperature, although synaptic transmission during and after trains of action potentials depends strongly on temperature (Klyachko & Stevens, 2006). We therefore set out to measure the effect of temperature on PTP at the calyx of Held. At the neuromuscular junction the decay of PTP is accelerated at higher temperature (Rosenthal, 1969; Zengel et al. 1980) and we first wanted to see whether this was also true at the calyx of Held synapse. At physiological temperature (PT) the fast rise time and large size of the EPSCs in the principal cells of the MNTB can lead to voltage escape (Borst et al. 1995). The competitive antagonist kynurenic acid, in addition to reducing postsynaptic receptor saturation and desensitization, improved the voltage-clamp on the postsynaptic cell by reducing the rise time and amplitude of the EPSCs (Wong et al. 2003). Kynurenic acid was less effective in reducing the EPSC amplitude at PT (37°C) compared to room temperature (RT). EPSCs were reduced to 3.6 ± 0.3% (n = 7) in 2 mm kynurenic acid at RT (24°C), while the EPSC amplitude was 7.1 ± 0.9% (n = 5) of control in 4 mm kynurenic acid at PT. A difference in inhibition of the EPSCs at PT versus RT has also been observed for γ-DGG (Kushmerick et al. 2006), which is a glutamate antagonist with a somewhat lower affinity compared to kynurenic acid (Wong et al. 2003).

At all frequencies tested (20, 50 and 100 Hz), PTP decayed somewhat faster at PT (t1/2= 2.7 ± 0.3 min; n = 20) than at RT (t1/2= 3.6 ± 0.4 min; n = 17), although the difference was not significant. Figure 5A shows the mean EPSC amplitudes obtained at RT when the terminals were stimulated with a 100 Hz tetanus (n = 9). A clear biphasic decay is apparent and the data points after the tetanus could be fitted with a double exponential function with time constants of 0.3 ± 0.4 min and 8.1 ± 3.6 min. Figure 5B shows the mean EPSC amplitude at PT (n = 5). The amount of PTP was not significantly smaller at 37°C than at RT and the decay looked similar. To compare the decay phases, the relative amplitudes are plotted on semilogarithmic axes in Fig. 5C. Example traces of individual EPSCs can be seen as insets in Fig. 5A and B for RT and PT, respectively. The EPSC kinetics were clearly faster at higher temperature, as has been reported previously at the calyx of Held synapse (Borst et al. 1995; Kushmerick et al. 2006; Postlethwaite et al. 2007).

Temperature has a profound effect on the filling of the RRP in the calyx of Held (Kushmerick et al. 2006) and other synapses (Dinkelacker et al. 2000; Pyott & Rosenmund, 2002). We therefore set out to explore the contribution of a change in pool size to PTP at PT. Before the application of kynurenic acid, the amplitude of spontaneous EPSCs was 43 ± 2 pA (n = 7) at RT and 76 ± 5 pA (n = 5) at PT (data not shown). These values are comparable to results by Kushmerick et al. (2006). Based on these findings we calculated the number of vesicles in the RRP by dividing the cumulative EPSC amplitude of a train by the spontaneous release amplitude. Our estimates for the number of releasable vesicles in the RRP at both temperatures were 781 ± 187 (RT, n = 7) and 623 ± 45 (PT, n = 5), which was not significantly different from each other and comparable to previous estimates based on this method (Schneggenburger et al. 1999; Wu & Borst, 1999). We repeated the experiment shown in Fig. 2 at 37°C (Fig. 6). Because the terminals follow high frequency stimulation more easily at PT, we increased the frequency of the test trains, which were given every 60 s, to 400 Hz. One experiment was excluded because it did not result in an increase of the EPSC amplitude after the tetanus. Figure 6C shows the mean cumulative EPSC amplitudes of three experiments. This figure shows that the mean RRP size 20 s after the tetanus (filled triangles) was not larger than the estimate from the last train before the tetanus (open circles). A clear increase in Pr is apparent when comparing the first response of a train after the tetanus with the first response of a train before the tetanus (Fig. 6A, B and C). Eighty seconds after the tetanus (open squares, Fig. 6C) Pr was back to baseline while the RRP was increased. On average, increasing the temperature from 24 to 37°C made the increase in Pr more transient (Fig. 6E). The dynamics of the RRP were also somewhat faster at PT (Fig. 6D), but this might be attributed to a slow decrease in RRP size during the baseline at PT, in contrast to the slow increase we observed at RT (Fig. 2E).

Figure 6. RRP dynamics at physiological temperature.

The size of the RRP was continuously probed at 37°C, with short 400 Hz trains in 4 mm kynurenic acid. Data of cells stimulated for 20 s to 1 min with a 100 Hz tetanus were pooled. A, the first 10 EPSCs of a train of 25 are shown for the last train before the tetanus (top) and for trains 20 s (middle) and 80 s (bottom) after the tetanus. B, enlargement of the first two EPSCs of control (dotted), 20 s (grey) and 80 s (black, continuous) trains shown in A. Traces were aligned on their prespikes. C, cumulative EPSC plots show the mean values of three experiments at control (○), 20 s (▴) and 80 s (□) after the tetanus. Error bars for the values 20 s after the tetanus are omitted for clarity. The cumulative release curves were fitted with lines (dotted line for control; continuous line, 20 s after the tetanus; dashed line, 80 s after the tetanus). D, the mean normalized RRP estimates from the experiments shown in C are plotted versus time after the tetanus. The RRP was probed with 1 min intervals. E, mean normalized Pr was calculated by dividing the first EPSC amplitude from a train by the RRP estimate. F, EPSCs are preceded by a small prespike which resembles the first derivative of the action potential (examples shown in B). The mean Pr of the first EPSC is plotted versus the mean amplitude of the prespike for the three time points shown in A (n = 3). The prespike amplitudes were normalized to the mean pre-tetanus value.

In a previous study (Habets & Borst, 2006) we found a contribution of an increase in calcium influx to the increase in Pr. We hypothesized that this increase in calcium influx could be due to facilitation of the calcium current or due to broadening of the action potential. Action potential broadening is often linked to inactivation of potassium channels (Geiger & Jonas, 2000). Recovery from inactivation of these channels (Rodríguez et al. 1998) and thereby return of the action potential shape to control is much faster at higher temperatures. This could explain why the decay of Pr is much faster at 37°C. We therefore examined the prespike (Forsythe, 1994), which resembles an inverted first derivative of the action potential (Borst et al. 1995). Despite some rundown during the recording and the noisiness of this small signal, analysis of the prespikes at the time points shown in Fig. 6A and C indicates that the time course of the decrease in normalized prespike amplitude resembled the decay of Pr after the tetanus (Fig. 6B and F).

To compare the contribution of the change in RRP at RT and at PT we plotted the increase in RRP versus the increase in EPSC amplitude 1 min after the tetanus (PTP). The fit through the data was steeper for the data obtained at PT for 20 Hz (Fig. 7) and 50 Hz tetanization (data not shown). The steepness of the fits indicate that 1 min after the tetanus, more than 50% of PTP can be explained by an increase in the RRP at PT, while this percentage is considerably smaller (< 19%) at RT. The difference in contribution of the RRP between PT and RT was less clear for data obtained with a 100 Hz tetanus, probably because the dataset was smaller for this frequency. We conclude that the contribution of the RRP enlargement to PTP is more significant at PT compared to RT.

Figure 7. Contribution of the RRP increase to PTP.

The RRP increase 1 min after the tetanus of all cells stimulated with a 20 Hz tetanus was plotted against the amount of PTP. Data at RT (○) were fitted with a line through zero and a slope of 0.17 (continuous line). A similar fit through the data at PT (•, dotted line) resulted in a slope of 0.59. Experiments with depressed EPSCs are not shown, but were included in the fit.

Discussion

We measured the pool of vesicles that is immediately ready for release in the calyx of Held and found that it is enlarged after as few as 500 stimuli at 100 Hz. Furthermore, we could measure the RRP during PTP and its return to pretetanus levels. We saw that the increase in the RRP was longer lasting than the increase in Pr and that this difference was even larger at PT. At PT, Pr was increased for less than 80 s, thereafter it was the RRP increase that resulted in larger EPSCs.

Physiological relevance

The calyx of Held is part of the auditory network responsible for detecting interaural intensity differences. In young-adult mice the mean spontaneous firing rate is about 40 Hz (Kopp-Scheinpflug et al. 2003a), which is in the same order as the stimulation frequencies used in this study. Although our experiments are conducted at ages before the onset of hearing, it is conceivable that there is spontaneous activity at similar rates as in adult animals. The function of the calyx of Held synapse is considered to be that of a sign inverting relay (Schneggenburger & Forsythe, 2006; but see Kopp-Scheinpflug et al. 2003b). For this function fast and reliable transmission is important. Increasing the size of the RRP can increase the output of the synapse, thereby alleviating depression due to vesicle depletion, although for high frequencies the steady-state output was not increased (Figs 1B, 2B and 6C) and it is not yet known whether PTP is induced by the high firing rates of the adult calyx of Held synapse.

PTP at physiological temperature

We observed a biphasic decay of PTP at RT and found that the decay of Pr was dominated by an augmentation phase. At PT only the augmentation phase of Pr was detectable. Therefore, the overall decay of PTP at PT was dominated by the decay of the RRP size, which was only slightly accelerated. A moderate sensitivity of PTP for temperature is consistent with previous studies, in which a Q10 of around 2 for the decay of PTP was found (Zengel et al. 1980; Fisher et al. 1997) in contrast to a Q10 of 4–5 for augmentation (Magleby & Zengel, 1976; Klyachko & Stevens, 2006). The decay of Pr correlated with the amplitude of the prespike in the experiments conducted at PT. The prespike (Forsythe, 1994) is proportional to the inverted first derivative of the action potential (Borst et al. 1995) and a reduction of the prespike amplitude indicates a broadening of the action potential. The reduction of the prespike after the tetanus was larger than in our previous study (Habets & Borst, 2005). This is due to the fact that we started measuring sooner (20 s) after the tetanus in this study. Indeed at a comparable time after the tetanus (80 s) the prespike had already recovered to 78% (PT, Fig. 6) and 80% (RT, data not shown) of control. Broadening of the action potential contributes to the augmentation phase of PTP, because changes in the action potential shape have been shown to have a profound effect on neurotransmitter release (Borst & Sakmann, 1999; Geiger & Jonas, 2000; Fedchyshyn & Wang, 2005). We showed that during PTP, calcium influx is increased and that this increase is sufficient to explain the increase in release probability (Habets & Borst, 2006). Action potential broadening is one of the mechanisms that could underlie increased calcium influx during PTP. The contribution of a presynaptic post-tetanic hyperpolarization (Kim et al. 2007) to changes in action potential waveforms and release probabilities remains to be investigated under conditions that preserve PTP.

Temperature accelerates vesicle mobilization to the RRP (Pyott & Rosenmund, 2002; Kushmerick et al. 2006) and this accelerated replenishment in combination with calcium dependent vesicle recruitment transiently overfills the RRP in chromaffin cells (Dinkelacker et al. 2000). Unlike chromaffin cells, the size of the RRP in the calyx of Held was not significantly different at both temperatures, in agreement with the results of Kushmerick et al. (2006). PTP at the calyx of Held is dependent on residual calcium, which is apparently not very sensitive to changes in temperature. Residual calcium at other synapses has a moderate temperature dependence (Regehr et al. 1994; Dinkelacker et al. 2000).

RRP increase

A change in the number of vesicles immediately ready for release has been proposed as a mechanism for short-term plasticity in a number of other synapses (Byrne & Kandel, 1996; Rosenmund et al. 2002; Kuromi & Kidokoro, 2003; Zhao & Klein, 2004). After repetitive stimulation, no change or partial depletion of the RRP has been observed in hippocampal cultures (Stevens & Wesseling, 1999) and frog neuromuscular junction (Kalkstein & Magleby, 2004), respectively. In contrast to a study by Korogod et al. (2005), we found a 30% increase of the number of vesicles in the RRP during PTP at the calyx of Held (Habets & Borst, 2005). In the present study we show that this difference is not due to differences in the stimulation protocol since we found an even bigger enlargement of the pool with a similar tetanus (100 Hz, 5 s) as used in their experiments. Our measurements in P4 animals also exclude that the age of the rats caused the difference. We think that the time point at which the pool size was measured provides a more likely explanation. Korogod et al. (2005) measured 20 s after the tetanus. At this time point, we also did not observe an increase in the RRP, while another 60 s later the RRP was significantly overfilled.

The Pr of vesicles in the readily releasable pool of the calyx of Held is heterogeneous (Wu & Borst, 1999; Sakaba & Neher, 2001a). Both differential calcium sensitivities of the vesicles and positional heterogeneity may contribute to this heterogeneity (Wölfel & Schneggenburger, 2003; Sakaba et al. 2005; Wadel et al. 2007). During a train of short stimuli the vesicles with high Pr are depleted by 80–100% (Wu & Borst, 1999; Sakaba, 2006). We found that mainly the first four responses of a stimulus train were enlarged during PTP (Fig. 2B). These first four EPSCs are predominantly composed of vesicles from the pool with high Pr (Sakaba & Neher, 2001c). We therefore think that the increase in RRP during PTP is an increase of the number of vesicles with high Pr. It seems likely that residual calcium, the long-lasting increase in the presynaptic Ca2+ concentration after a tetanus, is involved in this increase. PTP at the calyx of Held synapse depends on residual calcium (Habets & Borst, 2005; Korogod et al. 2005). Since the RRP increase decayed with a similar time course to the residual calcium after a tetanus, the most parsimonious explanation is that the residual calcium was responsible for the increased pool size during PTP. The age dependence of the increase in RRP size may then have its origin in the calcium extrusion, which is faster in older animals (Chuhma & Ohmori, 2001). This view is supported by the observation that PTP can be induced in older animals by stimulation at higher frequency. We assumed constant replenishment in all our measurements of the RRP, which is most likely not correct. If the two pools of vesicles identified at the calyx of Held represent different maturation steps in vesicle priming (Sakaba & Neher, 2003b) acceleration of the replenishment to the high Pr pool, due to residual calcium from the tetanus, could account for the observed increase in RRP size. A Ca2+/calmodulin dependent acceleration of replenishment of the high Pr pool has been shown in the calyx of Held (Sakaba & Neher, 2001a). Calmodulin is thought to regulate the RRP size during short-term plasticity via an interaction with Munc13 (Junge et al. 2004), a protein involved in the modulation of transmitter release by phorbol esters in the calyx of Held (Hori et al. 1999). Another possibility is that the cAMP-dependent guanosine exchange factor Epac is involved in the increase in the number of vesicles with high Pr (Sakaba & Neher, 2001b, 2003a; Kaneko & Takahashi, 2004). Many proteins that are involved in the docking or priming process could function as downstream effectors of Ca2+ and/or cAMP, including synapsins (Sun et al. 2006), Munc18 (Toonen et al. 2006), Rim (Calakos et al. 2004), or Rab3 and other Ras-related GTPases (Owe-Larsson et al. 2005; Schlüter et al. 2006). These proteins might aid in increasing the RRP size independently or in conjunction (Dulubova et al. 2005) with each other.

Acknowledgments

We like to thank Rostislav Turecek and Laurens Bosman for critical reading of an earlier version of the manuscript. This work was supported by a Neuro-Bsik grant (Senter, the Netherlands).

References

- Awatramani GB, Price GD, Trussell LO. Modulation of transmitter release by presynaptic resting potential and background calcium levels. Neuron. 2005;48:109–121. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollmann JH, Sakmann B, Borst JGG. Calcium sensitivity of glutamate release in a calyx-type terminal. Science. 2000;289:953–957. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5481.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borst JGG, Helmchen F, Sakmann B. Pre- and postsynaptic whole-cell recordings in the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body of the rat. J Physiol. 1995;489:825–840. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp021095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borst JGG, Sakmann B. Calcium influx and transmitter release in a fast CNS synapse. Nature. 1996;383:431–434. doi: 10.1038/383431a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borst JGG, Sakmann B. Effect of changes in action potential shape on calcium currents and transmitter release in a calyx-type synapse of the rat auditory brainstem. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1999;354:347–355. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1999.0386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne JH, Kandel ER. Presynaptic facilitation revisited: state and time dependence. J Neurosci. 1996;16:425–435. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-02-00425.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calakos N, Schoch S, Südhof TC, Malenka RC. Multiple roles for the active zone protein RIM1α in late stages of neurotransmitter release. Neuron. 2004;42:889–896. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuhma N, Ohmori H. Differential development of Ca2+ dynamics in presynaptic terminal and postsynaptic neuron of the rat auditory synapse. Brain Res. 2001;904:341–344. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02506-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond JS, Jahr CE. Transporters buffer synaptically released glutamate on a submillisecond time scale. J Neurosci. 1997;17:4672–4687. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-12-04672.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinkelacker V, Voets T, Neher E, Moser T. The readily releasable pool of vesicles in chromaffin cells is replenished in a temperature-dependent manner and transiently overfills at 37°C. J Neurosci. 2000;20:8377–8383. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-22-08377.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulubova I, Lou X, Lu J, Huryeva I, Alam A, Schneggenburger R, Südhof TC, Rizo J. A Munc13/RIM/Rab3 tripartite complex: from priming to plasticity? EMBO J. 2005;24:2839–2850. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmqvist D, Quastel DMJ. A quantitative study of end plate potentials in isolated human muscle. J Physiol. 1965;178:505–529. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1965.sp007639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedchyshyn MJ, Wang LY. Developmental transformation of the release modality at the calyx of Held synapse. J Neurosci. 2005;25:4131–4140. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0350-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher SA, Fischer TM, Carew TJ. Multiple overlapping processes underlying short-term synaptic enhancement. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20:170–177. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)01001-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsythe ID. Direct patch recording from identified presynaptic terminals mediating glutamatergic EPSCs in the rat CNS, in vitro. J Physiol. 1994;479:381–387. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger JRP, Jonas P. Dynamic control of presynaptic Ca2+ inflow by fast-inactivating K+ channels in hippocampal mossy fiber boutons. Neuron. 2000;28:927–939. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00164-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habets RLP, Borst JGG. Post-tetanic potentiation in the rat calyx of Held synapse. J Physiol. 2005;564:173–187. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.079160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habets RLP, Borst JGG. An increase in calcium influx contributes to post-tetanic potentiation at the rat calyx of Held synapse. J Neurophysiol. 2006;96:2868–2876. doi: 10.1152/jn.00427.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffpauir BK, Grimes JL, Mathers PH, Spirou GA. Synaptogenesis of the calyx of Held: rapid onset of function and one-to-one morphological innervation. J Neurosci. 2006;26:5511–5523. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5525-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori T, Takai Y, Takahashi T. Presynaptic mechanism for phorbol ester-induced synaptic potentiation. J Neurosci. 1999;19:7262–7267. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-17-07262.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junge HJ, Rhee JS, Jahn O, Varoqueaux F, Spiess J, Waxham MN, Rosenmund C, Brose N. Calmodulin and Munc13 form a Ca2+ sensor/effector complex that controls short-term synaptic plasticity. Cell. 2004;118:389–401. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalkstein JM, Magleby KL. Augmentation increases vesicular release probability in the presence of masking depression at the frog neuromuscular junction. J Neurosci. 2004;24:11391–11403. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2756-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko M, Takahashi T. Presynaptic mechanism underlying cAMP-dependent synaptic potentiation. J Neurosci. 2004;24:5202–5208. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0999-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH, Sizov I, Dobretsov M, von Gersdorff H. Presynaptic Ca2+ buffers control the strength of a fast post-tetanic hyperpolarization mediated by the α3 Na+/K+-ATPase. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:196–205. doi: 10.1038/nn1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klyachko VA, Stevens CF. Temperature-dependent shift of balance among the components of short-term plasticity in hippocampal synapses. J Neurosci. 2006;26:6945–6957. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1382-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp-Scheinpflug C, Fuchs K, Lippe WR, Tempel BL, Rübsamen R. Decreased temporal precision of auditory signaling in Kcna1-null mice: an electrophysiological study in vivo. J Neurosci. 2003a;23:9199–9207. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-27-09199.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp-Scheinpflug C, Lippe WR, Dorrscheidt GJ, Rübsamen R. The medial nucleus of the trapezoid body in the gerbil is more than a relay: comparison of pre- and postsynaptic activity. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2003b;4:1–23. doi: 10.1007/s10162-002-2010-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korogod N, Lou X, Schneggenburger R. Presynaptic Ca2+ requirements and developmental regulation of posttetanic potentiation at the calyx of Held. J Neurosci. 2005;25:5127–5137. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1295-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuromi H, Kidokoro Y. Two synaptic vesicle pools, vesicle recruitment and replenishment of pools at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction. J Neurocytol. 2003;32:551–565. doi: 10.1023/B:NEUR.0000020610.13554.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushmerick C, Renden R, von Gersdorff H. Physiological temperatures reduce the rate of vesicle pool depletion and short-term depression via an acceleration of vesicle recruitment. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1366–1377. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3889-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou X, Scheuss V, Schneggenburger R. Allosteric modulation of the presynaptic Ca2+ sensor for vesicle fusion. Nature. 2005;435:497–501. doi: 10.1038/nature03568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magleby KL, Zengel JE. Augmentation: a process that acts to increase transmitter release at the frog neuromuscular junction. J Physiol. 1976;257:449–470. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1976.sp011378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owe-Larsson B, Chaves-Olarte E, Chauhan A, Kjaerulff O, Brask J, Thelestam M, Brodin L, Löw P. Inhibition of hippocampal synaptic transmission by impairment of Ral function. Neuroreport. 2005;16:1805–1808. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000186594.87328.c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postlethwaite M, Hennig MH, Steinert JR, Graham BP, Forsythe ID. Acceleration of AMPA receptor kinetics underlies temperature-dependent changes in synaptic strength at the rat calyx of Held. J Physiol. 2007;579:69–84. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.123612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyott SJ, Rosenmund C. The effects of temperature on vesicular supply and release in autaptic cultures of rat and mouse hippocampal neurons. J Physiol. 2002;539:523–535. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regehr WG, Delaney KR, Tank DW. The role of presynaptic calcium in short-term enhancement at the hippocampal mossy fiber synapse. J Neurosci. 1994;14:523–537. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-02-00523.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez BM, Sigg D, Bezanilla F. Voltage gating of Shaker K+ channels. The effect of temperature on ionic and gating currents. J Gen Physiol. 1998;112:223–242. doi: 10.1085/jgp.112.2.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenmund C, Sigler A, Augustin I, Reim K, Brose N, Rhee JS. Differential control of vesicle priming and short-term plasticity by Munc13 isoforms. Neuron. 2002;33:411–424. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00568-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal J. Post-tetanic potentiation at the neuromuscular junction of the frog. J Physiol. 1969;203:121–133. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1969.sp008854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaba T. Roles of the fast-releasing and the slowly releasing vesicles in synaptic transmission at the calyx of Held. J Neurosci. 2006;26:5863–5871. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0182-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaba T, Neher E. Calmodulin mediates rapid recruitment of fast-releasing synaptic vesicles at a calyx-type synapse. Neuron. 2001a;32:1119–1131. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00543-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaba T, Neher E. Preferential potentiation of fast-releasing synaptic vesicles by cAMP at the calyx of Held. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001b;98:331–336. doi: 10.1073/pnas.021541098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaba T, Neher E. Quantitative relationship between transmitter release and calcium current at the calyx of Held synapse. J Neurosci. 2001c;21:462–476. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-02-00462.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaba T, Neher E. Direct modulation of synaptic vesicle priming by GABAB receptor activation at a glutamatergic synapse. Nature. 2003a;424:775–778. doi: 10.1038/nature01859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaba T, Neher E. Involvement of actin polymerization in vesicle recruitment at the calyx of Held synapse. J Neurosci. 2003b;23:837–846. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-03-00837.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaba T, Stein A, Jahn R, Neher E. Distinct kinetic changes in neurotransmitter release after SNARE protein cleavage. Science. 2005;309:491–494. doi: 10.1126/science.1112645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sätzler K, Söhl LF, Bollmann JH, Borst JGG, Frotscher M, Sakmann B, Lübke JHR. Three-dimensional reconstruction of a calyx of Held and its postsynaptic principal neuron in the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10567–10579. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-24-10567.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheuss V, Neher E. Estimating synaptic parameters from mean, variance, and covariance in trains of synaptic responses. Biophys J. 2001;81:1970–1989. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75848-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schikorski T, Stevens CF. Morphological correlates of functionally defined synaptic vesicle populations. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:391–395. doi: 10.1038/86042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlüter OM, Basu J, Südhof TC, Rosenmund C. Rab3 superprimes synaptic vesicles for release: implications for short-term synaptic plasticity. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1239–1246. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3553-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneggenburger R, Forsythe ID. The calyx of Held. Cell Tissue Res. 2006;326:311–337. doi: 10.1007/s00441-006-0272-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneggenburger R, Meyer AC, Neher E. Released fraction and total size of a pool of immediately available transmitter quanta at a calyx synapse. Neuron. 1999;23:399–409. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80789-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneggenburger R, Sakaba T, Neher E. Vesicle pools and short-term synaptic depression: lessons from a large synapse. Trends Neurosci. 2002;25:206–212. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(02)02139-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens CF, Wesseling JF. Augmentation is a potentiation of the exocytotic process. Neuron. 1999;22:139–146. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80685-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Bronk P, Liu X, Han W, Südhof TC. Synapsins regulate use-dependent synaptic plasticity in the calyx of Held by a Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2880–2885. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511300103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun JY, Wu LG. Fast kinetics of exocytosis revealed by simultaneous measurements of presynaptic capacitance and postsynaptic currents at a central synapse. Neuron. 2001;30:171–182. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00271-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taschenberger H, Leão RM, Rowland KC, Spirou GA, von Gersdorff H. Optimizing synaptic architecture and efficiency for high-frequency transmission. Neuron. 2002;36:1127–1143. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01137-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toonen RFG, Wierda K, Sons MS, de Wit H, Cornelisse LN, Brussaard A, Plomp JJ, Verhage M. Munc18–1 expression levels control synapse recovery by regulating readily releasable pool size. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:18332–18337. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608507103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Gersdorff H, Borst JGG. Short-term plasticity at the calyx of Held. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:53–64. doi: 10.1038/nrn705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadel K, Neher E, Sakaba T. The coupling between synaptic vesicles and Ca2+ channels determines fast neurotransmitter release. Neuron. 2007;53:563–575. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wölfel M, Schneggenburger R. Presynaptic capacitance measurements and Ca2+ uncaging reveal submillisecond exocytosis kinetics and characterize the Ca2+ sensitivity of vesicle pool depletion at a fast CNS synapse. J Neurosci. 2003;23:7059–7068. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-18-07059.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong AYC, Graham BP, Billups B, Forsythe ID. Distinguishing between presynaptic and postsynaptic mechanisms of short-term depression during action potential trains. J Neurosci. 2003;23:4868–4877. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-12-04868.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu LG, Borst JGG. The reduced release probability of releasable vesicles during recovery from short-term synaptic depression. Neuron. 1999;23:821–832. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)80039-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu XS, Wu LG. Protein kinase C increases the apparent affinity of the release machinery to Ca2+ by enhancing the release machinery downstream of the Ca2+ sensor. J Neurosci. 2001;21:7928–7936. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-20-07928.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Wu LG. The decrease in the presynaptic calcium current is a major cause of short-term depression at a calyx-type synapse. Neuron. 2005;46:633–645. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zengel JE, Magleby KL, Horn JP, McAfee DA, Yarowsky PJ. Facilitation, augmentation, and potentiation of synaptic transmission at the superior cervical ganglion of the rabbit. J Gen Physiol. 1980;76:213–231. doi: 10.1085/jgp.76.2.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Klein M. Changes in the readily releasable pool of transmitter and in efficacy of release induced by high-frequency firing at Aplysia sensorimotor synapses in culture. J Neurophysiol. 2004;91:1500–1509. doi: 10.1152/jn.01019.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RS, Regehr WG. Short-term synaptic plasticity. Annu Rev Physiol. 2002;64:355–405. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.64.092501.114547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]