Abstract

Using quantitative sensory testing (QST), we found that many migraineurs seeking secondary and tertiary care exhibit cutaneous allodynia whenever they undergo a migraine attack, but not interictally (i.e., between attacks). When such patients were quizzed interictally in the clinic about symptoms of skin sensitivity in past attacks, 76% of them were ‘correctly’ classified either as allodynic (≥1 symptoms) or non-allodynic (zero symptoms) in line with the QST analysis. In this study, patients were classified as allodynic if they documented any one symptom of allodynia during an actual migraine attack that they already cited in an earlier interictal interview. Of a total of 151 patients, 77% were classified as allodynic, citing on average 4 symptoms of skin hypersensitivity, 3 of which were consistently cited in the interictal interview and again during an attack. Among the remaining 23% patients who were classified as non-allodynic, half cited zero symptoms as expected, while the other half cited between 1 and 5 symptoms, each of which cited either interictally or during an attack, but not in both. Further analysis showed that 97% of patients citing ≥2 symptoms during an attack consisted of the patients labeled as allodynic, and that 75% of those citing just one symptom during an attack consisted of patients labeled as non-allodynic. Short of QST analysis, the results suggest that about 90% of all patients can be identified as allodynic or non-allodynic depending on whether or not they (a) consistently cited the same item(s) both interictally and during an attack or, alternatively, (b) cited ≥2 symptoms during an attack.

Introduction

The occurrence of “scalp tenderness” during migraine was first described in 1832 (1) and then documented in greater detail during the 1950s-60's (2, 3) and the 1980's (4-11). Using quantitative sensory testing (QST), we found that 70-80% of migraineurs seeking secondary and tertiary care exhibited cephalic and extracephalic cutaneous allodynia (decreased pain thresholds to thermal and mechanical stimulation of the skin) whenever they underwent a migraine attack (12). Knowing whether a given patient is allodynic during the attack was found to be crucial for effective triptan therapy, because allodynic migraineurs, unlike non-allodynic ones, must resort to triptan treatment soon after the onset of the attack in order to be rendered pain-free (13).

Notwithstanding its scientific merits, QST is a rather impractical, cost-ineffective tool to be used routinely in the doctor's office involving lengthy testing when the patient is free of migraine, and again during an attack (12, 13). We have therefore developed a set of questions presented interictally to migraine patients, asking them to recall whether they were aware of skin hypersensitivity during past migraine attacks (14, 15, 16). When quizzed interictally in the clinic about symptoms of skin sensitivity in past attacks, 76% of the patients were ‘correctly’ classified as either allodynic (≥1 symptoms) or non-allodynic (zero symptoms) in line with the QST analysis (16). In order to improve on the accuracy of the data obtained from the questionnaire, we examined in this study whether interictal recollection of allodynia symptoms was consistent with observations of allodynia made by the patients during an actual migraine attack at home.

Patients and methods

Patient selection

The study was carried out in accordance with the ethical standards of the Institutional Review Board for Studies with Human Subjects of Thomas Jefferson University Hospital and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 1983. Included in the study were patients between the ages of 12 and 60 years who met the International Headache Society (IHS) criteria for episodic migraine with or without aura (17), had 1-6 migraine attacks per month, and were able to give an informed consent. Excluded from the study were patients with chronic daily headache or with chronic non-cephalic pain and patients who had been treated with Botulinum toxin for any indication.

Experimental protocol

Patients visited the clinic when they were free of migraine, at least 5 days from the conclusion of the last migraine attack. Patients were interviewed regarding migraine history (e.g., age of onset, number of years with migraine, frequency and duration of attacks, pain characteristics) and associated symptoms (e.g., nausea, vomiting, photophobia, phonophobia, osmophobia, muscle tenderness). During the interview, patients were asked to recall whether they had abnormal skin sensitivity during migraine attacks (see questionnaire below). Patients were sent home with a questionnaire that contained the same questions on skin sensitivity as the ones they were asked during the interview. They were instructed to fill it when having an acute migraine attack. When completed, the questionnaire was either mailed back to the clinic or given to the investigator during the patients' following office visit.

The questionnaire

Do you experience pain or unpleasant sensation on your skin during a migraine attack when you engage in any of the following activities (Yes, No, or Not Applicable): (1) combing your hair; (2) pulling your hair back (example: ponytail); (3) shaving your face; (4) wearing eyeglasses; (5) wearing contact lenses; (6) wearing earrings; (7) wearing necklaces; (8) wearing anything tight on your head or neck (hat, scarf); (9) wearing anything on your arm or wrist (bracelet, watch); (10) wearing a finger ring; (11) wearing tight clothes; (12) being covered with a heavy blanket; (13) taking a shower (when shower water hits your face); (14) resting your face on the pillow on the side of the headache; (15) being exposed to heat (examples: cooking; placing heating pads on your face); (16) being exposed to cold (examples: breathing through your nose on a cold day; placing ice packs on your face).

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using non-parametric statistics (18). Item-by-item analysis of the questionnaire was performed using the χ2 test or Fisher exact probability test, depending on sample size and expected frequencies. The number of symptoms cited by allodynic patients was compared to that cited by non-allodynic patients using the Mann-Whitney U test. Within each group, the number of symptoms cited in the interview was compared to that cited during an attack using the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-ranked test. The level of significance was set at 0.05.

Results

The study included 151 patients (125 women, 26 men) 34.4±1.0 years of age (mean±SEM). They were 16.7±0.7 years old when they sustained their first migraine attack and had 17.5±1.0 years of episodic migraine history. They estimated to undergo 3.5±0.1 attacks per month, each attack lasting 1.6±0.2 days, and approximated having a total of 7.0±0.3 days of migraine per month. Based on the interictal interview, the prevalence of migraine-associated symptoms was as follows: visual aura – 34% of the patients; photophobia – 94%; phonophobia – 86%, osmophobia – 58%; nausea – 84%, vomiting – 44%; muscle tenderness – 53% (16% before and 37% after attack onset). According to real-time records taken during a migraine attack at home, they filled the questionnaire 198±11 min after the headache began to throb.

Criterion for allodynia

Of the 151 patients, 139 (92%) and 132 (87%) cited ≥1 symptoms of skin hypersensitivity in the interview and during an actual migraine attack, respectively. A patient was classified as allodynic if she/he cited any one questionnaire item during a migraine attack that she/he already cited before in the interview. Using this criterion of consistent citation, 119 patients (79%) were classified as allodynic and 32 (21%) as non-allodynic.

Item-by-item analysis of the 16-item questionnaire

Citation of each of the 16 questionnaire items are listed from the highest to the lowest frequency in Table 1. During a migraine attack, citations of 15 out of 16 markers of skin hypersensitivity were significantly lower in non-allodynic than allodynic patients. Data analysis indicated that exclusion of 8 lower-frequency items (bottom 8 items in Table 1) affected the classification of only 3 patients, yielding 116 allodynic and 35 non-allodynic patients (77% and 23%, respectively).

Table 1.

Incidence of positive responses to individual questionnaire items during an interictal interview and an actual migraine attack.

| Symptoms of skin hypersensitivity |

Number of responders citing a given symptom |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Account during an attack |

Interictal recollection |

|||

| Allodynic | Non-allodynic | Allodynic | Non-allodynic | |

| 1. Ponytaila | 82 | 1 | 77 | 4 |

| 2. Tight clothsa | 72 | 1 | 69 | 3 |

| 3. Combinga | 71 | 2 | 67 | 5 |

| 4. Pillowa | 68 | 6 | 61 | 3 |

| 5. Heata | 62 | 3 | 56 | 8 |

| 6. Eye glassesa | 57 | 1 | 61 | 7 |

| 7. Tight head/neck geara | 48 | 2 | 44 | 3 |

| 8. Colda | 41 | 0 | 41 | 2 |

| 9. Showera | 38 | 0 | 41 | 2 |

| 10. Necklaceb | 30 | 0 | 19 | 1 |

| 11. Earringb | 28 | 0 | 22 | 1 |

| 12. Arm-wristb | 26 | 0 | 21 | 1 |

| 13. Contact lensesc | 18 | 0 | 18 | 0 |

| 14. Blanketc | 17 | 0 | 16 | 0 |

| 15. Ringc | 13 | 0 | 8 | 0 |

| 16. Shavingd | 3 | 0 | 5 | 1 |

p<0.0001, χ2 test

p<0.005, χ2 test

p<0.05, Fisher exact probability test, comparing allodynic and non-allodynic patients during a migraine attack.

not significant, Fisher exact probability test, comparing allodynic and non-allodynic patients during a migraine attack.

Patient-by-patient analysis of the 8-item questionnaire

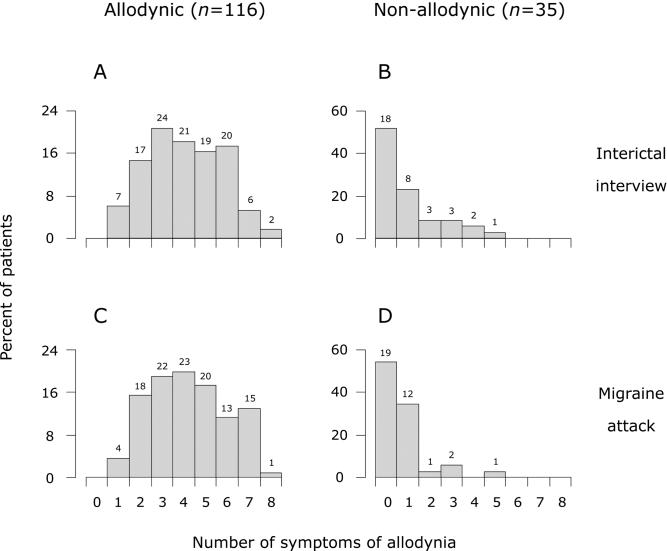

All 116 patients classified as allodynic cited between 1 and 8 symptoms of skin hypersensitivity (Fig. 1A and B): mean±SEM number of items cited was 4.05±0.16 in the interview and 4.22±0.16 during an attack; of those, 3.26±0.16 items were repeated in both situations. Among the 35 patients classified as non-allodynic, about half were unaware of any sign of skin hypersensitivity as expected, but the remaining half cited between 1 and 5 symptoms: 2.12±0.32 in the interview and 1.56±0.29 during an attack (Fig. 1C and D). The proportion of patients classified as allodynic who cited ≥2 symptoms of skin hypersensitivity was 97% (112/116) based on data recorded during an actual attack, and 94% (109/116) based on the interictal interview. The corresponding proportions of patients classified as non-allodynic who cited ≥2 symptoms of skin hypersensitivity were 11% (4/35) using data collected during an attack, and 26% (9/35) based on interictal interview.

Figure 1.

Percentage of allodynic (A, C) and non-allodynic (B, D) patients citing symptoms of skin hypersensitivity in the interictal interview and during an attack. Numbers above bars indicate actual number of patients. A vs. B or C vs. D: p<0.0001, Mann-Whitney U-test. A vs. C or B vs. D: p>0.22, Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test.

Grouping the patients on the basis of the number of symptoms cited during a migraine attack (Fig. 2) indicated that all patients citing zero symptoms (n=19) fell in the non-allodynic category, whereas 97% of those citing ≥2 symptoms (112/116) were in the allodynic category. The remaining 16 patients (=10.5% of all patients) cited just one symptom of allodynia; contrary to expectation, 75% of those patients fell in the non-allodynic category.

Figure 2.

Distribution of allodynic (black) and non-allodynic (gray) patients according to the number of symptoms of skin hypersensitivity cited during a migraine attack. Note that 75% of patients citing a single symptom were non-allodynic.

Discussion

We have previously established that 70-80% of migraineurs seeking secondary and tertiary medical help develop cephalic and extracephalic allodynia each time they undergo a migraine attacks (12). This observation was made using QST analysis, in which pain thresholds to mechanical and thermal skin stimulation were determined in each patient interictally (baseline) and during an actual migraine attack. We found that 15% of the patients classified as allodynic by QST were unaware of any marker skin hypersensitivity using a 12-item questionnaire in an interictal interview, and that 48% of those classified as non-allodynic by QST cited one or more items in the interview (12). We concluded that when patients are free of migraine, they are less likely to reliably remember symptoms they had experienced in past attacks. However, the present study showed no significant differences between the number of allodynia symptoms recalled in the absence of migraine and the number cited during an actual attack. Moreover, the non-allodynic patients that recalled certain symptoms in the interview cited other symptoms during an attack, suggesting that the questionnaire accuracy may be limited not only by recollection, but also by subjective perception.

In agreement with the rate of allodynia that was determined using QST (12), 77% of the patients in the present study were classified as allodynic if they cited any one questionnaire item during a migraine attack that they already cited before in the interview. Virtually all patients who cited ≥2 symptoms during a migraine attack (=77% of all patients) fell in the allodynic category, and all patients who cited zero symptoms (=12.5% of all patients) fell in the non-allodynic category. The remaining patients who cited just a single symptom (=10.5% of all patients) were in the non-allodynic category for the most part. Short of QST analysis, the results suggest that about 90% of the patients can be identified as allodynic or non-allodynic if they cited the same item twice, once interictally and again during an attack or, alternatively, if they cited ≥2 symptoms during a migraine attack.

In agreement with our previous studies (12, 13, 16), there was no difference between allodynic and non-allodynic patients in the prevalence of aura (37 vs. 41%), photophobia (94 vs. 94%), phonophobia (88 vs. 79%) or osmophobia (56 vs. 62%). If these symptoms are initiated and mediated by neuronal hyperexcitability in the visual, auditory, olfactory, sensory and motor cortices (19), our findings suggest that the initiation or maintenance of allodynia does not depend on cortical hyperexcitability.

As a practical approach for identifying allodynic migraineurs, we propose to rely on a questionnaire that focuses on the first 8 items in Table 1, which cover thermal (heat and cold) and mechanical (static and dynamic) allodynia. We recommend that the threshold for allodynia be based on either one of the following methods: (a) a minimum of one item cited consistently interictally and during an attack or, (b) a minimum of two items cited during an actual attack.

Acknowledgments

Supported by a grant from GlaxoSmithKline, and by NIH grants NS051484 and NS35611 (National Institutes of Neurological Disorder and Stroke) to Dr. Burstein.

References

- 1.Liveing E. On Megrim, Sick-Headache. Arts and Boeve; Nijmegen: 1873. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolff HG, Tunis MM, Goodell H. Studies on migraine. Arch. Internal Medicine. 1953;92:478–484. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1953.00240220026006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Selby G, Lance JW. Observations on 500 cases of migraine and allied vascular headache. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiat. 1960;23:32. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tfelt-Hansen P, Lous I, Olesen J. Prevalence and significance of muscle tenderness during common migraine attacks. Headache. 1981;21(2):49–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1981.hed2102049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lous I, Olesen J. Evaluation of pericranial tenderness and oral function in patients with common migraine, muscle contraction headache and ‘combination headache’. Pain. 1982;12(4):385–393. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(82)90183-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jensen K, Tuxen C, Olesen J. Pericranial muscle tenderness and pressure-pain threshold in the temporal region during common migraine. Pain. 1988;35(1):65–70. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90277-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jensen R, Rasmussen BK, Pedersen B, Lous I, Olesen J. Prevalence of oromandibular dysfunction in a general population. J Orofacial Pain. 1993;7(2):175–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jensen K. Extracranial blood flow, pain and tenderness in migraine. Clinical and experimental studies. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl. 1993;147:1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waelkens J. Warning symptoms in migraine: characteristics and therapeutic implications. Cephalalgia. 1985;5(4):223–228. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1985.0504223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drummond PD. Scalp tenderness and sensitivity to pain in migraine and tension headache. Headache. 1987;27(1):45–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1987.hed2701045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blau JN. Adult migraine: the patient observed. In: Blau JN, editor. Migraine - Clinical, therapeutic, conceptual and research aspects. Chapman and Hall Ltd; Cambridge: 1987. pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burstein R, Yarnitsky D, Goor-Aryeh I, Ransil BJ, Bajwa ZH. An association between migraine and cutaneous allodynia. Annals Neurol. 2000;47:614–624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burstein R, Jakubowski M, Collins B. Defeating migraine pain with triptans: A race against the development of cutaneous allodynia. Ann Neurol. 2004;55(1):19–26. doi: 10.1002/ana.10786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ashkenazi A, Young WB. The effects of greater occipital nerve block and trigger point injection on brush allodynia and pain in migraine. Headache. 2005;45(4):350–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2005.05073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lopinto C, Young W, Ashkenazi A. Comparison of dynamic (brush) and static (pressure) mechanical allodynia in migraine. Cephalalgia. 2006;26(7):852–856. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2006.01121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jakubowski M, Silberstein S, Ashkenazi A, Burstein R. Can allodynic migraine patients be identified interictally using a questionnaire? Neurology. 2005;65(9):1419–1422. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000183358.53939.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The international classification of headache disorders second edition. Cephalalgia. 2004;24(supplement 1):1–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2003.00824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zar JH. Biostatistical Analysis. 4th ed. Prentice-Hall; Englewood Cliffs: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bolay H, Moskowitz MA. The emerging importance of cortical spreading depression in migraine headache. Rev Neurol (Paris) 2005;161(67):655–657. doi: 10.1016/s0035-3787(05)85108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]