Abstract

An analysis of trends in hospital use and capacity by ownership status and community poverty levels for large urban and suburban areas was undertaken to examine changes that may have important implications for the future of the hospital safety net in large metropolitan areas. Using data on general acute care hospitals located in the 100 largest cities and their suburbs for the years 1996, 1999, and 2002, we examined a number of measures of use and capacity, including staffed beds, admissions, outpatient and emergency department visits, trauma centers, and positron emission tomography scanners. Over the 6-year period, the number of for-profit, nonprofit, and public hospitals declined in both cities and suburbs, with public hospitals showing the largest percentage of decreases. By 2002, for-profit hospitals were responsible for more Medicaid admissions than public hospitals for the 100 largest cities combined. Public hospitals, however, maintained the longest Medicaid average length of stay. The proportion of urban hospital resources located in high poverty cities was slightly higher than the proportion of urban population living in high poverty cities. However, the results demonstrate for the first time, a highly disproportionate share of hospital resources and use among suburbs with a low poverty rate compared to suburbs with a high poverty rate. High poverty communities represented the greatest proportion of suburban population in 2000 but had the smallest proportion of hospital use and specialty care capacity, whereas the opposite was true of low poverty suburbs. The results raise questions about the effects of the expanding role of private hospitals as safety net providers, and have implications for poor residents in high poverty suburban areas, and for urban safety net hospitals that care for poor suburban residents in surrounding communities.

Keywords: Medicaid ALOS, Poverty, Safety net hospitals, Suburban hospital care, Urban hospital care

INTRODUCTION

The 100 largest U.S. cities and their surrounding suburbs are home to more than half the nation’s population.1 Among the greatest challenges for both urban and suburban communities today is the growing difficulty hospitals face meeting the needs of poor and uninsured residents while surviving economically in an ever-competitive health care environment.2 At the same time, federal, state, and local governments are reassessing their financial commitments to safety net facilities as political pressure mounts to contain or reduce costs associated with Medicaid and charity care.

These market forces and government actions are creating significant shifts in the composition of the safety net in large metropolitan areas across the country. Research has documented a decline in the number of general acute care hospitals across these areas since at least 1980.3 As core components of the safety net, public hospitals have been part of this trend, declining 14% in the 100 largest cities and 43% in their surrounding suburbs between 1980 and 1996. The decline in public hospitals, whether through closure or conversion, has raised concerns about the increasing role of the private sector in providing care to the poor and uninsured. In areas where public hospitals have been privatized, evidence indicates that care for the uninsured declines.4 And because major urban safety net hospitals are more likely to provide critical, high cost, and frequently unprofitable specialty care, such as neonatal intensive care, and are more likely to care for uninsured and difficult to treat patients, the closure or conversion of these facilities may, by implication, reduce access significantly.5

Concerns About Urban–Suburban Hospital Disparities

A small but growing literature has focused on urban–suburban hospital “disparities.” The Community Tracking Survey (CTS) has found a widening disparity in high quality care found at the community level in Indianapolis, Seattle, Phoenix, Greenville, Northern New Jersey, and Miami, in which physician specialists and hospital systems are disproportionately investing resources in wealthier suburban communities.6 A recent CTS case study of Northern New Jersey hospitals found that the largest hospital systems are “competing aggressively for market share in wealthy suburban areas” that are experiencing population growth, by expanding and upgrading facilities, whereas smaller hospitals serving lower income and aging urban communities with stagnant or declining populations are struggling, with several closing in recent years.7 Our research from an unpublished pilot study in 2003 found that relatively poor suburban areas that are home to increasing numbers of diverse and immigrant populations, such as in suburban Los Angeles, are struggling with inadequate access to hospital care, particularly regarding a lack of emergency and specialty care, made worse by the dispersion of populations and services across a large geographic area.

The Agency for Health Care Research (AHRQ), in noting the often distinctive differences in demographics and population density between central cities and their surrounding suburbs, has emphasized the importance of assessing the differences between the needs and problems of safety nets in urban and suburban areas.8 However, little research has systematically examined and compared urban and suburban trends in hospital availability, capacity, and utilization across large metropolitan areas.

This study analyzes indicators of hospital use and availability for urban and suburban areas by focusing on two key dimensions: hospital ownership status and the poverty level of the area where a hospital is located. First, we describe hospital characteristics and volume of care by ownership status across cities and suburbs for 1996, 1999, and 2002. Secondly, we examine select measures of hospital use and capacity of cities and suburbs by poverty level, which is positively correlated with illness and health care need.9 From these results, we consider how the delivery of hospital care may be changing in urban and suburban areas, particularly for vulnerable populations, and the potential implications for the hospital safety net in large metropolitan areas.

METHODS

The Social and Health Landscape of Urban and Suburban America project, from which this study originated, documented the social and health improvements and challenges occurring in the nation’s 100 largest cities and their suburbs between 1990 and 2000.1 The selection of the 100 largest cities for both 1990 and 2000 was based on population counts from the 2000 Census.10 Although there is no standard method for defining a suburban area, the counties are the federal government’s standard building blocks for defining a metropolitan statistical area (MSA).11 We define the suburbs as the counties making up a primary MSA, excluding the central city(ies). Over time, as traditionally “suburban” cities have grown relatively rapidly in recent years, many now appear on the list of 100 largest cities. Aurora, in the Denver MSA and Plano, Garland, and Irving in the Dallas MSA are examples. In these cases where more than one of the 100 largest cities are part of the same MSA, the combined city data from that MSA were subtracted to define the suburban area. Thus, the sampling represents 100 cities in 82 distinct metropolitan areas.

This method of selection from the 100 largest cities produces a different set of cities and suburbs than a selection based on the 100 largest metropolitan areas. Our method may somewhat lessen the differences found between city and suburban averages compared to a method that selects the largest metropolitan areas first and subtracts the “traditional” central city to define the suburban area.

We report 1996, 1999, and 2002 hospital data provided by Health Forum from the American Hospital Association (AHA) annual surveys for general acute care hospitals located in the metropolitan areas of the 100 largest cities. The nonresponse rate was about 18% for all 3 years. At least one hospital from each city participated in the survey each year. Eight suburban areas had no hospital data included in the study.

We examined hospital data by three categories of ownership: public, nonprofit, and for-profit, as reported by each institution. The hospital indicators included number of hospitals, staffed beds, admissions, inpatient days, outpatient and emergency department (ED) visits, Medicaid discharges, and Medicaid average length of stay (ALOS). These data were grouped and analyzed by urban and suburban location, as described above.

To examine the relationship between hospital capacity or utilization with poverty, we categorized cities and suburbs each into three poverty groups and compared their relative distribution of hospital services with their relative distribution of population. Population size itself is not a perfect indicator of demand because people can use hospitals in places where they do not live. However, we note that other research has found that 75% of discharges among acute care urban hospitals took place within a 10-mile radius.12 Because hospital utilization data were not available by patient address, we aggregated population and hospital resource and utilization data across all cities and across all suburbs. This allowed us to make relative comparisons by poverty levels that minimize the effects of variation of individual locations.

We defined levels of low, medium, and high poverty to create similarly sized groups of cities and suburbs, based on poverty data from the 2000 Census.13 Levels were created separately for cities and suburbs because of the large difference in average poverty rates (17.4% for cities, 9.3% for suburbs). For cities, low was defined as less than 15%, medium as 15 to 20%, and high as greater than 20%. For suburbs, low was defined as less than 7%, medium as 7 to 10%, and high as greater than 10%. We calculated the percentage of total urban population that each poverty group of cities comprises and the percentage of total suburban population that each poverty group of suburbs comprises.

We aggregated the following hospital indicators, using 2002 data, by urban and suburban poverty groups: staffed beds, admissions, inpatient days, outpatient and ED visits, number of level 1 or 2 trauma centers, number of positron emission tomography (PET) scanners, and number of neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) beds. To analyze the relative availability or use of hospital resources by poverty level for each indicator listed above, we compared each urban poverty group’s percentage of the total to each poverty group’s percentage of total urban population. The same method applied for the suburban poverty groups.

RESULTS

Utilization by Hospital Ownership

The suburbs, which have two thirds more population than the urban areas of the 100 largest cities, are home to many more acute care general hospitals than the cities they surround. Urban hospitals, however, have more staffed beds and provide a much larger volume of both inpatient and outpatient care, on average, compared to suburban hospitals, regardless of ownership type.

All hospital ownership groups experienced moderate to substantial declines in their numbers from 1996 to 2002 (Table 1). Proportionally, the greatest losses occurred among public hospitals. Public hospitals declined by 16% in cities, from 83 to 70, compared with 11% for nonprofit and for-profit urban hospitals. Suburban public hospitals declined by 27%, from 134 to 98 between 1996 and 2002 (Table 2). Suburban area nonprofit and for-profit hospitals decreased by 2 and 11%, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Urban hospital statistics by type of ownership

| Hospital ownership | 1996 | 1999 | 2002 | Percent change | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996–1999 | 1999–2002 | 1996–2002 | |||||

| Number of hospitals | For-profit | 161 | 148 | 143 | −8.1 | −3.4 | −11.2 |

| Nonprofit | 486 | 454 | 432 | −6.6 | −4.8 | −11.1 | |

| Public | 83 | 72 | 70 | −13.3 | −2.8 | −15.7 | |

| Total | 730 | 674 | 645 | −7.7 | −4.3 | −11.6 | |

| Staffed beds | |||||||

| Per hospital | For-profit | 209 | 226 | 238 | |||

| Total | 33,727 | 33,459 | 34,004 | −0.8 | 1.6 | 0.8 | |

| Per hospital | Nonprofit | 372 | 381 | 394 | |||

| Total | 180,789 | 173,156 | 170,070 | −4.2 | −1.8 | −5.9 | |

| Per hospital | Public | 431 | 420 | 434 | |||

| Total | 35,805 | 30,265 | 30,381 | −15.5 | 0.4 | −15.1 | |

| Per hospital | Total | 343 | 351 | 363 | |||

| Total | 250,321 | 236,880 | 234,455 | −5.4 | −1.0 | −6.3 | |

| Admissions | |||||||

| Per hospital | For-profit | 7,496 | 8,969 | 10,208 | |||

| Total | 1,206,876 | 1,327,367 | 1,459,763 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 21.0 | |

| Per hospital | Nonprofit | 14,930 | 16,602 | 18,419 | |||

| Total | 7,255,948 | 7,537,279 | 7,956,852 | 3.9 | 5.6 | 9.7 | |

| Per hospital | Public | 17,321 | 17,861 | 18,613 | |||

| Total | 1,437,671 | 1,285,989 | 1,302,886 | −10.6 | 1.3 | −9.4 | |

| Per hospital | Total | 13,562 | 15,060 | 16,619 | |||

| Total | 9,900,495 | 10,150,635 | 10,719,501 | 2.5 | 5.6 | 8.3 | |

| Inpatient days | |||||||

| Per hospital | For-profit | 40,972 | 47,471 | 53,407 | |||

| Total | 6,596,463 | 7,025,670 | 7,637,232 | 6.5 | 8.7 | 15.8 | |

| Per hospital | Nonprofit | 91,617 | 96,441 | 103,603 | |||

| Total | 44,525,807 | 43,784,349 | 44,756,438 | −1.7 | 2.2 | 0.5 | |

| Per hospital | Public | 115,710 | 116,131 | 122,214 | |||

| Total | 9,603,959 | 8,361,430 | 8,554,979 | −12.9 | 2.3 | −10.9 | |

| Per hospital | Total | 83,187 | 87,791 | 94,494 | |||

| Total | 60,726,229 | 59,171,449 | 60,948,649 | −2.6 | 3.0 | 0.4 | |

| Outpatient visits | |||||||

| Per hospital | For-profit | 65,782 | 80,738 | 91,289 | |||

| Total | 10,590,903 | 11,949,217 | 13,054,346 | 12.8 | 9.2 | 23.3 | |

| Per hospital | Nonprofit | 181,449 | 214,040 | 248,214 | |||

| Total | 88,184,008 | 97,173,938 | 107,228,265 | 10.2 | 10.3 | 21.6 | |

| Per hospital | Public | 323,333 | 360,183 | 408,377 | |||

| Total | 26,836,659 | 25,933,162 | 28,586,419 | −3.4 | 10.2 | 6.5 | |

| Per hospital | Total | 172,071 | 200,380 | 230,805 | |||

| Total | 125,611,570 | 135,056,317 | 148,869,030 | 7.5 | 10.2 | 18.5 | |

| ED visits | |||||||

| Per hospital | For-profit | 17,077 | 21,980 | 27,507 | |||

| Total | 2,749,400 | 3,253,030 | 3,933,480 | 18.3 | 20.9 | 43.1 | |

| Per hospital | Nonprofit | 33,957 | 39,851 | 44,865 | |||

| Total | 16,503,073 | 18,092,234 | 19,381,719 | 9.6 | 7.1 | 17.4 | |

| Per hospital | Public | 60,176 | 63,166 | 70,167 | |||

| Total | 4,994,646 | 4,547,933 | 4,911,690 | −8.9 | 8.0 | −1.7 | |

| Per hospital | Total | 33,215 | 38,417 | 43,763 | |||

| Total | 24,247,119 | 25,893,197 | 28,226,889 | 6.8 | 9.0 | 16.4 | |

Source: AHA Annual Survey of Hospitals, 1996, 1999, 2002

TABLE 2.

Suburban hospital statistics by type of ownership

| Hospital ownership | 1996 | 1999 | 2002 | Percent change | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996–1999 | 1999–2002 | 1996–2002 | |||||

| Number of hospitals | For-profit | 164 | 146 | 146 | −11.0 | 0.0 | −11.0 |

| Nonprofit | 608 | 603 | 595 | −0.8 | −1.3 | −2.1 | |

| Public | 134 | 111 | 98 | −17.2 | −11.7 | −26.9 | |

| Total | 906 | 860 | 839 | −5.1 | −2.4 | −7.4 | |

| Staffed beds | |||||||

| Per hospital | For-profit | 148 | 145 | 145 | |||

| Total | 24,301 | 21,152 | 21,219 | −13.0 | 0.3 | −12.7 | |

| Per hospital | Nonprofit | 204 | 203 | 201 | |||

| Total | 124,190 | 122,663 | 119,746 | −1.2 | −2.4 | −3.6 | |

| Per hospital | Public | 135 | 149 | 171 | |||

| Total | 18,156 | 16,513 | 16,738 | −9.0 | 1.4 | −7.8 | |

| Per hospital | Total | 184 | 186 | 188 | |||

| Total | 166,647 | 160,328 | 157,703 | −3.8 | −1.6 | −5.4 | |

| Admissions | |||||||

| Per hospital | For-profit | 5,412 | 5,861 | 6,680 | |||

| Total | 887,489 | 855,748 | 975,213 | −3.6 | 14.0 | 9.9 | |

| Per hospital | Nonprofit | 8,228 | 9,077 | 9,732 | |||

| Total | 5,002,332 | 5,473,212 | 5,790,584 | 9.4 | 5.8 | 15.8 | |

| Per hospital | Public | 5,149 | 6,048 | 7,468 | |||

| Total | 689,902 | 671,352 | 731,815 | −2.7 | 9.0 | 6.1 | |

| Per hospital | Total | 7,262 | 8,140 | 8,936 | |||

| Total | 6,579,723 | 7,000,312 | 7,497,612 | 6.4 | 7.1 | 14.0 | |

| Inpatient days | |||||||

| Per hospital | For-profit | 26,587 | 28,229 | 31,886 | |||

| Total | 4,360,344 | 4,121,392 | 4,655,293 | −5.5 | 13.0 | 6.8 | |

| Per hospital | Nonprofit | 45,541 | 47,160 | 48,757 | |||

| Total | 27,689,204 | 28,437,474 | 29,010,544 | 2.7 | 2.0 | 4.8 | |

| Per hospital | Public | 29,518 | 36,015 | 43,066 | |||

| Total | 3,955,393 | 3,997,678 | 4,220,449 | 1.1 | 5.6 | 6.7 | |

| Per hospital | Total | 39,741 | 42,508 | 45,156 | |||

| Total | 36,004,941 | 36,556,544 | 37,886,286 | 1.5 | 3.6 | 5.2 | |

| Outpatient visits | |||||||

| Per hospital | For-profit | 48,672 | 58,376 | 69,625 | |||

| Total | 7,982,232 | 8,522,945 | 10,165,240 | 6.8 | 19.3 | 27.3 | |

| Per hospital | Nonprofit | 117,154 | 136,517 | 149,959 | |||

| Total | 71,229,639 | 82,319,984 | 89,225,596 | 15.6 | 8.4 | 25.3 | |

| Per hospital | Public | 83,167 | 109,429 | 137,717 | |||

| Total | 11,144,417 | 12,146,647 | 13,496,252 | 9.0 | 11.1 | 21.1 | |

| Per hospital | Total | 99,731 | 119,755 | 134,550 | |||

| Total | 90,356,288 | 102,989,576 | 112,887,088 | 14.0 | 9.6 | 24.9 | |

| ED visits | |||||||

| Per hospital | For-profit | 16,433 | 19,524 | 22,624 | |||

| Total | 2,695,092 | 2,850,473 | 3,303,051 | 5.8 | 15.9 | 22.6 | |

| Per hospital | Nonprofit | 25,221 | 28,197 | 31,841 | |||

| Total | 15,334,310 | 17,002,859 | 18,945,393 | 10.9 | 11.4 | 23.5 | |

| Per hospital | Public | 19,338 | 22,367 | 27,502 | |||

| Total | 2,591,272 | 2,482,717 | 2,695,148 | −4.2 | 8.6 | 4.0 | |

| Per hospital | Total | 22,760 | 25,972 | 29,730 | |||

| Total | 20,620,674 | 22,336,049 | 24,943,592 | 8.3 | 11.7 | 21.0 | |

Source: AHA Annual Survey of Hospitals, 1996, 1999, 2002

As the number of hospitals declined, the bed size per hospital increased over the same 6-year period. For-profit hospitals had the largest average increase in bed size in cities (14%), whereas public hospitals led in the suburbs (26%). Increases in average bed size were associated with increases in utilization. Urban for-profit hospitals consistently showed the greatest increases in several indicators, including the average number of admissions (36%), inpatient days (30%), outpatient visits (39%), and ED visits (61%) per hospital between 1996 and 2002.

With the largest average bed size, urban public hospitals had much higher utilization per facility than nonprofit and for-profit urban hospitals. Across the entire set of 100 largest cities, however, they were responsible for fewer total admissions, inpatient days, and ED visits (but not outpatient visits) in 2002 than in 1996. In contrast, for-profit hospitals, as a group, saw double-digit growth on each of these measures, and by 2002, had surpassed public hospitals in the total number of staffed beds (34,000 vs 30,400) and admissions (1.5 million vs 1.3 million) in the largest urban areas.

Medicaid Utilization and Hospital Ownership

In cities, public hospitals maintained the highest average rate of Medicaid discharges as a percentage of total admissions in 2002 (31.1%) compared to nonprofit hospitals (18%) and for-profit hospitals (19.8%), but the differences among the groups have narrowed since 1996. For-profit and nonprofit hospitals increased their share of Medicaid discharges from 1996 to 2002, whereas the reverse was true for public hospitals (Table 3). Total Medicaid discharges rose nearly 39% among for-profit hospitals while declining more than 20% among urban public hospitals. Medicaid discharges rose about 17% among nonprofit hospitals over the same 6-year period.

TABLE 3.

Medicaid discharges and ALOS for urban and suburban hospitals

| Hospital ownership | 1996 | 1999 | 2002 | Percent change | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996–1999 | 1999–2002 | 1996–2002 | |||||

| Urban hospitals | |||||||

| Medicaid discharges | |||||||

| Percent of total admissions | For-profit | 17.3 | 15.9 | 19.8 | |||

| No. of discharges | 208,574 | 211,548 | 289,347 | 1.4 | 36.8 | 38.7 | |

| Percent of total admissions | Nonprofit | 16.9 | 14.2 | 18.0 | |||

| No. of discharges | 1,227,919 | 1,073,857 | 1,431,585 | −12.5 | 33.3 | 16.6 | |

| Percent of total admissions | Public | 35.8 | 31.4 | 31.1 | |||

| No. of discharges | 515,129 | 403,748 | 405,326 | −21.6 | 0.4 | −21.3 | |

| Percent of total admissions | Total | 19.2 | 16.5 | 19.8 | |||

| No. of discharges | 1,896,137 | 1,669,811 | 2,124,729 | −11.9 | 27.2 | 12.1 | |

| Medicaid ALOS | For-profit | 4.9 | 5.1 | 5.0 | 4.4 | −1.1 | 3.2 |

| Nonprofit | 6.8 | 6.8 | 6.2 | −0.2 | −8.9 | −9.1 | |

| Public | 6.8 | 7.4 | 7.5 | 8.6 | 2.2 | 11.1 | |

| Total | 6.6 | 6.7 | 6.3 | 1.7 | −6.3 | −4.6 | |

| Suburban hospitals | |||||||

| Medicaid discharges | |||||||

| Percent of total admissions | For-profit | 17.2 | 14.4 | 17.9 | |||

| No. of discharges | 152,703 | 123,054 | 174,505 | −19.4 | 41.8 | 14.3 | |

| Percent of total admissions | Nonprofit | 12.5 | 10.6 | 13.3 | |||

| No. of discharges | 626,999 | 582,664 | 770,523 | −7.1 | 32.2 | 22.9 | |

| Percent of total admissions | Public | 17.8 | 22.1 | 18.9 | |||

| No. of discharges | 122,463 | 148,502 | 137,976 | 21.3 | −7.1 | 12.7 | |

| Percent of total admissions | Total | 14.2 | 12.8 | 14.8 | |||

| No. of discharges | 931,123 | 893,282 | 1,106,106 | −4.1 | 23.8 | 18.8 | |

| Medicaid ALOS | For-profit | 4.6 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 8.5 | −0.2 | 8.3 |

| Nonprofit | 6.3 | 6.3 | 5.7 | 0.8 | −9.2 | −8.5 | |

| Public | 6.9 | 8.3 | 7.7 | 19.9 | −6.8 | 11.8 | |

| Total | 6.1 | 6.4 | 5.9 | 5.8 | −8.7 | −3.4 | |

Source: AHA Annual Survey of Hospitals, 1996, 1999, 2002

Medicaid’s proportion of total admissions per hospital varied much less by ownership type in the suburbs compared to urban areas, ranging from an average of 13.3% for nonprofit hospitals to 18.9% for public hospitals in 2002. In contrast to urban hospitals, the Medicaid proportion of total discharges per hospital and the total number of Medicaid discharges rose among suburban hospitals for all three ownership types between 1996 and 2002. Suburban for-profit hospitals were responsible for a larger total number of Medicaid discharges than public hospitals for each of the three study years.

In both cities and suburbs, for-profit hospitals had the shortest Medicaid ALOS and public hospitals had the longest. From 1996 to 2002, city and suburban public hospitals both saw similar increases—between 11 and 12%—in their Medicaid ALOS to 7.5 days for city public hospitals, and to 7.7 days among suburban public hospitals. In contrast, the ALOS for Medicaid patients served in nonprofit hospitals declined by 9% to 6.2 days in cities and declined by 8.5% to 5.7 days in suburban areas. For-profit hospitals in cities and suburbs saw modest increases (about 3 and 8%, respectively) in their Medicaid ALOS to 5 days in 2002.

Hospital Utilization and Capacity by Poverty Level in Cities and Suburbs

The cities and suburban areas, each grouped by low, medium, and high poverty rates, as described in the Methods section, differ on a number of demographic characteristics. On average, high poverty cities and high poverty suburbs are relatively larger, have the lowest proportions of white residents and those without a high school education, have the highest proportion of black residents, and have the highest percentage of population that receives public assistance and is unemployed (Table 4). Violent crime rates are also highest in high poverty cities and suburbs, as are low birth weight rates, relative to their respective low and medium poverty groups. Cities, overall, are more racially and ethnically diverse than their suburbs, but vary less by poverty level on the percentage of Hispanic and foreign-born residents compared with the suburbs.

TABLE 4.

Characteristics of 100 largest cities and their suburbs by poverty rate levelsa, 2000

| Cities by poverty level | Suburbs by poverty level | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Low | Medium | High | Total | Low | Medium | High | |

| Total populationb | 56,590,581 | 19,956,047 | 12,812,500 | 23,822,034 | 94,758,109 | 25,094,993 | 27,888,383 | 41,774,733 |

| Average population size | 690,129 | 623,626 | 557,065 | 882,298 | 1,184,461 | 815,347 | 1,237,728 | 1,562,885 |

| Percent of population 65 and older | 11.2 | 10.5 | 10.9 | 12.2 | 11.2 | 11.1 | 11.7 | 10.7 |

| Percent of population non-Hispanic white | 50.7 | 60.9 | 52.6 | 37.0 | 73.8 | 84.1 | 75.3 | 58.0 |

| Percent of population non-Hispanic black | 25.4 | 15.7 | 18.3 | 42.9 | 8.2 | 6.0 | 8.3 | 11.1 |

| Percent of population Hispanic | 16.3 | 13.0 | 21.9 | 15.3 | 12.5 | 5.3 | 9.4 | 26.4 |

| Percent of population foreign-born | 13.3 | 13.4 | 14.2 | 12.6 | 9.4 | 7.4 | 8.4 | 13.6 |

| Percent of population on public assistance | 5.1 | 3.4 | 5.1 | 7.2 | 2.7 | 1.8 | 2.5 | 4.1 |

| Percent of population 25 and older with no high school diploma | 21.6 | 16.4 | 22.0 | 27.5 | 16.8 | 12.0 | 15.5 | 25.1 |

| Unemployment rate (%) | 7.6 | 5.5 | 7.3 | 10.4 | 4.9 | 3.6 | 4.6 | 7.1 |

| Violent crime rate (per 100,000 pop.) | 990.3 | 792.2 | 893.4 | 1307.7 | 323.0 | 216.9 | 337.5 | 448.4 |

| Low birth weight rate (percent of live births) | 8.9 | 7.8 | 8.2 | 10.6 | 7.1 | 6.6 | 7.1 | 7.6 |

Source: Demographic statistics tabulated from 2000 Census Bureau data; violent crime rates tabulated from 2000 FBI crime data; low birth weight rates tabulated from the 2000 Natality Data Set provided by the National Center for Health Statistics.

aCategories for percentage of population living below federal poverty level are (1) cities: low <15%, medium 15–20%, and high >20%; suburbs: low <7%, medium 7–10%, and high >10%

bSuburban numbers exclude the population of suburban areas that were not represented by in the hospital data sets.

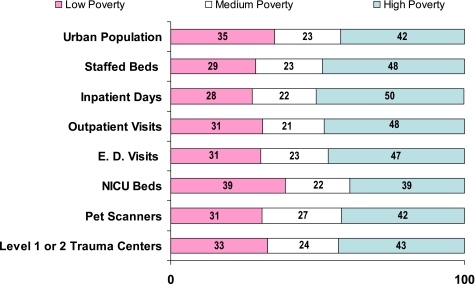

We found that the proportion of hospital utilization and resources in high poverty cities was modestly higher than their proportion of urban population. High poverty cities had slightly higher proportions of beds, admissions, inpatient days, and ED and outpatient visits relative to their proportion of the total urban population (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

One hundred largest cities by poverty level: Distribution of 2000 population compared with distribution of hospital beds, utilization and specialty care, 2002 (percentages shown).

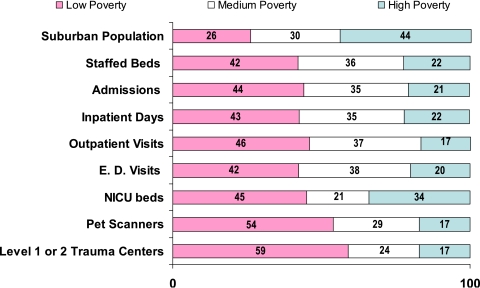

By contrast, high poverty suburbs showed dramatically lower levels of utilization relative to their share of the suburban population. These suburban communities, which accounted for the largest proportion of the suburban population—44% in 2000—represented about one fifth of all suburban hospital beds, ED admissions, and inpatient days in 2002, and only 17% of the outpatient visits (Figure 2). Low poverty suburbs, with just over one quarter (26%) of the total suburban population, accounted for 42% of suburban hospital beds and more than 40% of each of the other utilization measures.

FIGURE 2.

Suburbs of 100 largest cities by poverty level: Distribution of 2000 population compared with distribution of hospital beds, utilization and specialty care, 2002 (percentages shown).

We selected three high-cost hospital services to examine by community poverty level: level 1 or 2 trauma care, PET scanners, and NICU beds. In cities, the overall distribution and availability of these services across the three poverty groups generally matched the distribution of the population across these groupings. For example, high poverty cities, with 42% of the total urban population in 2000, represented 43% of the urban level 1 and 2 trauma centers, 42% of the urban PET scanners, and 39% of the urban NICU beds in 2002.

In suburban areas, distribution of these services by level of poverty was not proportionate to the population distribution by poverty level. The low poverty suburbs, with 26% of the total suburban population, accounted for 59% of these trauma centers, 54% of the PET scanners, and 45% of the NICU beds. From 1996 to 2002, the number of PET scanners reported in hospitals located in low poverty suburbs increased from 3 to 60 (data not shown). As with service utilization, high poverty suburbs were significantly underrepresented by these capacity measures. With 44% of total suburban population, they had only 17% of suburban trauma centers and PET scanners and 34% of suburban NICU beds in 2002.

DISCUSSION

The results of our analysis of hospital data for urban and suburban areas of the 100 largest cities between 1996 and 2002 highlight two key themes. The first is that while public hospitals remain as the major safety net providers in the communities they serve, hospital inpatient care overall and for Medicaid patients in particular appears to be shifting from the public to the private sector. These trends raise questions about the long-term effects of a hospital safety net increasingly comprised of nonprofit and for-profit institutions.

The second theme relates to the apparent disparities in the relative availability of hospital resources between low poverty and high poverty suburban areas. In contrast, for cities, there was only modest or little difference between the percentage distribution of utilization or availability of select specialty care services across low, medium, and high urban poverty areas, and the percentage distribution of population across these three groups. The findings have implications for poor residents in high poverty suburban areas, and also for urban safety net hospitals and the role that they may play in caring for poor suburban residents in surrounding communities. The appropriateness of the levels of hospital resources concentrated in low poverty suburban areas also comes into question.

City–Suburban Differences by Ownership

The number of general acute care hospitals and staffed beds declined between 1996 and 2002, with public hospitals showing the largest percentage decreases in both cities (16%) and suburbs (27%). These trends represent an acceleration in closings, mergers, or conversions of public hospitals compared with the previous 16-year period, between 1980 and 1996, noted earlier. The remaining urban public hospitals continued to be relatively large facilities, as measured by their bed size, but their presence across the urban landscape is diminishing. By 2002, for-profit hospitals had eclipsed public hospitals in the volume of total and Medicaid admissions in the largest cities. Whereas urban public hospitals still provided a larger share of ED visits compared with urban for-profit hospitals, they were the only group to see a decline in ED visits between 1996 and 2002.

These trends suggest a diminishing role for public hospitals in the provision of inpatient care and a shift toward the private sector. This change has been documented in New York City and Miami, for example, where the public hospital systems are facing increasing competition from private hospitals for Medicaid enrollees.14,15 However, research on urban and suburban hospital care found that private hospitals maintained a very consistent proportion of gross patient revenues attributed to Medicaid and self-pay (i.e., a proxy for uninsured) patients during the 1990s, and that changes within one category were offset by relatively similar amounts in the other.16 This consistency suggests that private hospitals, in general, may seek to stabilize a ceiling on the proportion of revenues dedicated to low income populations to maintain their operating margins. To do so may require decreasing charity care or increasing revenues through collections, or seeking Medicaid patients who are more likely to generate positive income (e.g., women giving birth). However, the threat of lawsuits and congressional hearings are putting more pressure on nonprofit hospitals to show they have provided a significant community benefit worthy of their tax-exempt status, particularly regarding care for the uninsured and other vulnerable populations.17,18

In suburbs, for-profit hospitals continued to have a larger share of total and Medicaid inpatient volume compared to public hospitals. But unlike urban areas, both inpatient and outpatient volume increased across suburban pubic hospitals. In addition, average bed size for remaining public hospitals increased considerably, suggesting that relatively smaller facilities closed or converted ownership, or merged with other hospitals. It is also possible that new beds were added to remaining hospitals as a result of hospital closings. One question, and an area for future research, is whether the larger size of remaining suburban public hospitals, combined with their increase in utilization across suburban areas, suggest that their numbers and staffed beds will stabilize or continue to decline from continued financial pressures.

We also found that public hospitals in urban and suburban areas had both the longest Medicaid ALOS and the steepest rise in Medicaid ALOS between 1996 and 2002. These findings may indicate that, on average, public hospitals treat more seriously ill Medicaid patients than for-profit or nonprofit hospitals, or that public hospitals are performing fewer services such as deliveries, which are associated with relatively shorter hospital stays. The results may also suggest that public hospitals are less efficient in providing care or in their discharge planning, which could also be related to patient circumstances beyond the hospitals’ control. Whether the longer ALOS is related to inefficiencies or sicker patients or both, the financial implications are ominous and worthy of additional study. Without adequate revenues to cover the costs of care and to maintain infrastructure, many public hospitals will continue to face an uphill battle for survival.

Hospitals in Low, Medium, and High Poverty Urban and Suburban Areas

Our review of hospital capacity and utilization by community poverty levels indicates that high poverty cities accounted for a slightly larger proportion of hospital use relative to their proportion of the total urban population, whereas the availability of specialty services such as trauma care, NICU beds, and PET scanners across low, medium, and high poverty cities was generally in line with the population distribution across these groups. Among suburban areas, however, we found that high poverty communities represented the greatest proportion of suburban population in 2000 but had the smallest proportion of hospital use and specialty care capacity, as indicated by the proportion of PET scanners, trauma care centers, and NICU beds. The opposite was true of low poverty suburbs, which represented the smallest proportion of total suburban population, but had the largest proportions of suburban hospital use and specialty care capacity. This lopsided distribution of hospital resources in favor of low poverty suburbs supports other research documenting that hospitals have targeted expansion of specialty care services to high-income markets.6,19 The population characteristics of low poverty suburban areas suggest that their residents are, on average, the most affluent in metropolitan America, and likely are the best insured.

By the same token, hospital systems may be reluctant to expand into high poverty suburbs. Although we do not have data on uninsured rates for these areas, low income is highly associated with insurance status.20 We also noted earlier that the high poverty suburban areas averaged the largest percentages of Hispanic and foreign-born populations. Surveys have documented these groups as having among the highest uninsured rates in the country.21 A lack of health coverage may be a contributing factor in the relatively small proportion of hospital resources available in high poverty suburbs.

For hospitals that do serve poor areas, the trends are troubling. We found that between 1996 and 2002, high poverty areas had the greatest decline in the number of suburban hospitals (data not shown). Such losses may further exacerbate access problems, particularly for those with limited or no insurance and limited transportation options.6 These findings suggest other areas of inquiry of metropolitan safety net issues by raising questions about whether residents in high poverty suburban areas, especially those who are poor or uninsured, will become increasingly dependent on nearby city public hospitals. This contention has already surfaced in Texas, where indigent or uninsured patients residing in surrounding suburban counties of five urban county hospital districts accounted for 16% of the $1.2 billion in uncompensated care provided by the public hospitals in these districts in 2002.22

The continued growth in the uninsured population in this country, which now exceeds 46 million, is one of the most critical issues facing safety net hospitals today, regardless of ownership status.23 The responsibilities of each community to care for its uninsured and other vulnerable populations fall on local hospitals and other safety net providers. In the absence of state, regional, or national reforms to significantly expand insurance coverage, hospitals will continue to search for ways to limit their financial exposure from caring for uninsured patients, particularly as the hospital industry becomes even more competitive in a global economy.24

A limitation of this study is that we did not conduct a multivariate analysis. Our aggregate analyses focus on poverty without considering other potentially important factors that may influence hospital distribution, or supply and demand, such as regional dynamics, local economics, political jurisdictional considerations, uninsured rates and rates of disability.25 At the same time, the results of our analysis may offer direction for future research that takes these factors into account. The results of this study also do not allow us to assess whether a group of cities or suburbs provides too much or too little hospital care, nor do they address critical concerns about the distribution of hospital services within individual cities or suburban areas.

CONCLUSIONS

What do these results by ownership and poverty say about the future of hospital care in urban and suburban areas? The continued losses of public hospitals in both cities and suburbs, at the very least, inject uncertainty about a changing hospital safety net that increasingly involves the private sector. The fallout from this transition in cities may differ significantly from the suburbs. In large central cities, the size of public and other primary safety net institutions, their constituency, their presence as an employer, and the political issues surrounding their status suggest that communities are likely to demand a careful assessment of impact, as well as a viable alternative safety net plan.4 Suburban areas with growing numbers of poor, or those losing their public or primary safety net hospitals, may be less likely to have the strong constituencies found in central cities. As a result, there may be a less vocal and concerted effort to assure that viable options are available, with the consequences falling on the most vulnerable. Ultimately, more regional cooperation may be required to ensure adequate financing and access to hospital care for the poor and uninsured in large metropolitan areas.

Acknowledgement

Funding for the Social and Health Landscape of Urban and Suburban America project, upon which this study was based, came from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Footnotes

Reports and statistics for individual cities and suburban areas are available at www.downstate.edu/healthdata. This report series was the successor to an earlier grant from Robert Wood Johnson Foundation to examine health and socio-economic trends of the nation’s 100 largest cities, from 1980 to 1990.

Andrulis is with the Center for Health Equality, School of Public Health, Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA 19102, USA; Duchon is with Health Management Associates, Washington, DC 20037, USA.

Contributor Information

Dennis P. Andrulis, Phone: +1-215-7626957, FAX: +1-215-7627840, Email: dennis.andrulis@drexel.edu

Lisa M. Duchon, Phone: 202-785-3669, FAX: 202-833-8932, Email: lduchon@healthmanagement.com

References

- 1.U.S. Census Bureau. Supplementary Survey Summary Tables for Census 2000 (database online). Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2002.

- 2.Dobson A, DaVanzo J, Sen N. The cost-shift payment ‘hydraulic’: Foundation, history, and implications. Health Aff. 2006;25:22–33. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Andrulis DP, Goodman NJ. The Social and Health Landscape of Urban and Suburban America. Chicago: AHA Press; 1999.

- 4.Waitzkin H. Commentary: The history and contradictions of the health care safety net. HSR. 2005;40:941–952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Gaskin DJ. Safety Net Hospitals: Essential Providers of Public Health and Specialty Services. New York: The Commonwealth Fund; 1999.

- 6.Hurley R, Pham H, Claxton G. A widening rift in access and quality: growing evidence of economic disparities. Health Aff. 2005;24:566–576. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Mays GP, Berenson RA, Bodenheimer T, et al. Urban–Suburban Hospital Disparities Grow in Northern New Jersey, community report no. 4. Washington, DC: The Center for Studying Health System Change; August, 2005. Available at http://www.hschange.com/CONTENT/769/769.pdf. Accessed December 10, 2006.

- 8.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Monitoring the Healthcare Safety Net, Book 1. Data for Metropolitan Areas, Chap. 2: Place Matters. Available at http://www.ahrq.gov/data/safetynet/. Accessed December 10, 2006 (This website also provides data on various safety net indicators and performance outcomes at the county and MSA level).

- 9.Shi L, Starfield B. Primary care, income inequality, and self-rated health in the United States: A mixed-level analysis. Int J Health Serv. 2000;30:541–555. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.U.S. Census Bureau. Metropolitan Areas and Components (with fips codes). USA: U.S. Census Bureau; 1999. Available at http://www.census.gov/population/estimates/metro-city/99mfips.txt. Accessed January 15, 2002.

- 11.Office Of Management and Budget. Standards for Defining Metropolitan and Micropolitan Areas; Notice. USA: Federal Register, vol. 65, no. 249; December 27, 2002. Available At http://www.census.gov/population/www/estimates/00-32997.pdf. Accessed March 4, 2004.

- 12.Gresenz CR, Rogowski J, Escarce JJ. Updated variable-radius measures of hospital competition. HSR. 2004;39:417–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.The 2000 federal poverty level for a family of three was $14,150 for the 48 contiguous states and the Districts of Columbia. Federal Register, Vol. 65, No. 31, February 15, 2000, pp. 7555–7557.

- 14.Chan S. City Hospitals May Need More Aid to Counter Deficit. The New York Times. March 13, 2006; B3.

- 15.Hirschkorn C, Trude S, Andrews CA, Brown LD. Market Calm, But Change on the Horizon: Miami, Florida. Washington, DC: The Center for Studying Health System Change; Spring 1999, community report no. 08. Available at http://hschange.org/CONTENT/104/?topic=topic01. Accessed December 10, 2006.

- 16.Andrulis DP, Goodman NJ. The Social and Health Landscape of Urban and Suburban America. Chicago: AHA Press; 1999.

- 17.Hyman DA, Sage WM. Subsidizing health care providers through the tax code: status or conduct. Health Aff. 2006;25:w312–w315. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Kane NM. Testimony Before the Full Committee of the House Committee on Ways and Means. Washington DC: Committee on Ways and Means; May 26, 2005. Available at http://waysandmeans.house.gov/hearings.asp?formmode=view&id=2719. Accessed December 10, 2006.

- 19.Bazzoli G, Gerland A, May J. Construction activity in U.S. hospitals. Health Aff. 2006;25:783–791. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.DeNavas-Walt C, Proctor, BD, Hill Lee C. U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Reports, P60–231, Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2005. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2006.

- 21.Schur CL, Feldman J. Job Characteristics, Immigrant Status and Family Structure Keep Hispanics Uninsured. New York: The Commonwealth Fund; 2001.

- 22.Amarsingham R, Pickens S, Anderson RJ. County hospitals and regional medical care in Texas: an analysis of out-of-county costs. Texas Medicine. 2004;100:56–59. Available at http://www.texmed.org/Template.aspx?id=1255. Accessed February 20, 2007. [PubMed]

- 23.Vladeck B. Paying for Hospitals’ Community Service. Health Aff. 2006;25:34–43. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Altman SH, Shactman D, Eilat E. Could U.S. hospitals go the way of U.S. airlines? Health Aff. 2006;25:11–21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.AHRQ. Monitoring the Healthcare Safety Net, Book 1. Data for Metropolitan Areas, Chap. 3: Demand for Safety Net Services. Available at http://www.ahrq.gov/data/safetynet/. Accessed December 10, 2006.