Abstract

The aim of this study was to identify optimized sets of genotyping targets for the staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec). We analyzed the gene contents of 46 SCCmec variants in order to identify minimal subsets of targets that provide useful resolution. This was achieved by firstly identifying and characterizing each available SCCmec element based on the presence or absence of 34 binary targets. This information was used as input for the software “Minimum SNPs,” which identifies the minimum number of targets required to differentiate a set of genotypes up to a predefined Simpson's index of diversity (D) value. It was determined that 22 of the 34 targets were required to genotype the 46 SCCmec variants to a D of 1. The first 6, 9, 12, and 15 targets were found to define 21, 29, 35, and 39 SCCmec variants, respectively. The genotypes defined by these marker subsets were largely consistent with the relationships between SCCmec variants and the accepted nomenclature. Consistency was made virtually complete by forcing the computer program to include ccr1 and ccr5 in the target set. An alternative target set biased towards discriminating abundant SCCmec variants was derived by analyzing an input file in which common SCCmec variants were repeated, thus ensuring that markers that discriminate abundant variants had a large effect on D. Finally, it was determined that mecA single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) can increase the overall genotyping resolution, as different mecA alleles were found in otherwise identical SCCmec variants.

Comparative bacterial genomics is revealing numerous hypervariable regions in bacterial chromosomes. Interrogation of such regions can efficiently provide an epidemiological fingerprint, or insight into pathogenic capability, antimicrobial resistance phenotype, or vaccine susceptibility (7, 9, 11). However, the often complex nature of the variations can make it difficult to devise standardized protocols for subtyping such regions.

An excellent example of a clinically relevant hypervariable region in a major bacterial pathogen is the staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) (16, 19). This element defines methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) through carriage of the beta-lactam resistance gene mecA. A combination of multilocus sequence type (MLST) and SCCmec type is frequently used as an identifier for MRSA clones (8, 31, 36). As a consequence, in recent years there has been considerable interest in developing SCCmec subtyping methods.

A number of broadly similar but distinct SCCmec typing methods have been described. These methods include PCR-based detection of type-specific targets (ccr variants, mec gene complexes, and junkyard regions [10, 29, 30, 46]), restriction digests (43, 45), and full sequence analysis (15-17). In general, SCCmec is divided into five major types based on the combination of mec class and recombinase-encoding (ccr) genes present (15, 17, 25). The mec classes are themselves defined by the arrangement of genes adjacent to mecA (38). Subtypes are defined by binary variation (presence or absence) of sequence blocks in the “junkyard” regions (4). The various typing methods and associated terminology have evolved in a somewhat ad hoc fashion as more SCCmec variants have been discovered. Recently, a proposal for a rationalized SCCmec typing nomenclature was published (4). This proposal has merit, as it incorporates the core structural features and the variable junkyard regions. However, there is currently no standardized SCCmec genotyping method that systematically and efficiently utilizes all known variations.

Our research group has previously developed the computer program “Minimum SNPs” (35). This was designed to derive sets of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) from MLST databases on the basis of maximization of resolving power. Resolving power may be measured either on the basis of the power to discriminate a user-defined sequence type from all other sequence types or on the basis of maximization of the Simpson's index of diversity (D) (13). More recently, this approach was adapted to the identification of resolution-optimized sets of binary markers. Price and coworkers derived a set of such markers from Campylobacter jejuni comparative genome hybridization data on the basis of D maximization, and these markers were shown to have considerable utility as genotyping targets (33). SCCmec diversity can also be considered to be a database of binary gene variation and is therefore amenable to a similar analysis. Accordingly, we have carried this out, with the central hypothesis of the study being that the sets of markers derived by our systematic approach would efficiently provide resolving power.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Identification of SCCmec variants.

A literature and NCBI database search was undertaken to identify SCCmec variants for this study. Variants were named according to the proposed SCCmec nomenclature system (4). This procedure was complicated by the fact that described SCCmec variants differ in the detail to which they have been analyzed; some are completely sequenced, while others are classified only though PCR amplification. In a small number of instances, SCCmec variants reported in the literature lacked sufficient structural information to be included in this study.

Identification of resolution-optimized sets of binary markers.

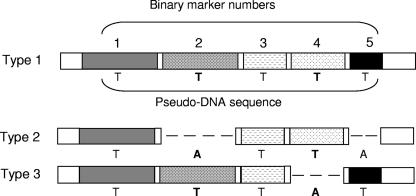

Sets of binary markers were identified using the computer program “Minimum SNPs” by a strategy illustrated in Fig. 1 (33, 35). This program extracts resolution-optimized sets of SNPs from DNA sequence alignments. It does this by identifying the single SNP with the highest resolving power, labeling this as SNP 1, and then identifying the SNP that in combination with SNP 1 gives the highest resolving power and labeling that as SNP 2, etc. A valuable feature of the software is that the user can force the program to include or exclude any SNP in/from the SNP set.

FIG. 1.

Illustration of the strategy used to identify sets of resolution-optimized binary markers. Each genotype of interest is characterized based on the presence (T) or absence (A) of the total set of binary markers (five are used in this example). Thus the binary gene configuration is converted into a pseudo-DNA sequence composed of A's and T's. The alignment of pseudo-DNA sequences is then analyzed using Minimum SNPs for combinations of binary markers that maximize the Simpson's index of diversity (D) (33). In the example shown above, binary genes 2 and 4 provide a D of 1, i.e., they completely resolve the three genotypes. In the present study, 46 SCCmec types were defined by the presence or absence of 34 binary markers. Even with this relatively small data set, manual identification of resolution-optimized marker sets is extremely difficult.

Minimum SNPs can measure resolving power in more than one way, but the most generally applicable method is by calculation of D with respect to the sequence alignment. This algorithm was used throughout this study. Resolution-optimized sets of binary markers were identified by first converting the binary marker data for the SCCmec variants into a string of “A's” and “T's,” with “A” denoting binary maker absence and “T” denoting binary marker presence. In this way the binary data for each SCCmec variant becomes a pseudo-DNA sequence that can be aligned with other pseudo-DNA sequences representing other SCCmec variants. This alignment was then mined by Minimum SNPs in order to identify sets of binary markers that give a high D value with respect to that alignment. The alignment input file reflecting estimated SCCmec abundance included 49 extra copies of variants: 1B.1.1 (I), 2A.1.1 (II), 3A1.1.1 (III), 3A.1.2 (IIIA), 3A.1.3 (IIIB), 2B.1 (IVa), 2B.2.1 (IVb), 2B.3.1 (IVc), and 5C.1 (V).

mecA nucleotide sequence determination and SNP analysis.

The mecA genes from 19 diverse Australian MRSA isolates from nine MLST types were amplified using primers mecAF1 and mecAR3 (Sigma-Proligo, Lismore, Australia) (39, 41). The amplicons were purified using Exo-SapIt (Amersham Biosciences, Castle Hill, Australia) for 15 min at 37°C and 15 min at 80°C and then sequenced for 1,400 bp from the 3′ end using primers mecAF1 and mecAR2. The sequence traces were viewed and analyzed in SeqMan II version 4.06 (DNAstar, Madison, Wis.).

The literature and NCBI databases were searched for S. aureus mecA gene sequences whose corresponding SCCmec type was known. Twenty-five mecA sequences were identified, cropped to 1,440 bp, and added to a sequence alignment with the 19 partial mecA sequences identified in this study. Clustal X (v. 1.64b) was used to align the partial mecA gene sequences to identify SNPs. In order to investigate the possibility of combinatorial genotyping methods based on SNPs and binary genes, the SNP data were added to the pseudo-DNA sequences derived from the binary marker genotypes, so as to construct an input file for Minimum SNPs that would allow the identification of resolution-optimized SNP-binary marker combinations.

For full details of the mecA sequences used in this analysis and the isolates from which they were derived, see the supplemental material.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The new mecA sequences have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers EF692630, EF692631, and EF692632.

RESULTS

Collation of currently available data concerning SCCmec binary diversity.

The overall aim of this study was to apply a systematic approach for the identification of genetic targets to efficiently genotype SCCmec. In order to do this effectively, it was necessary to extract all available SCCmec data from the literature and the publicly available databases. Diversity can be in the form of binary variability (gene presence/absence) or SNPs. As complete sequences are known for only a subset of the genes that make up all the known SCCmec variants, binary diversity data were collated and analyzed first.

Analysis of the literature and online databases resulted in the definition of 34 SCCmec-associated binary targets (Table 1). Unique sequences associated with the targets (see the supplemental material) were used to facilitate the design of genotyping methods. The 34 binary targets in turn defined 46 SCCmec variants (Table 2). Each SCCmec element differing at one or more of the 34 binary targets (Table 1) was considered a separate variant. This extensive compilation of SCCmec variants reveals the extensive rearrangement and mutation that the five major types have undergone during their evolutionary histories, with diversity in the junkyard regions defining the majority of the variants.

TABLE 1.

The 34 binary targets used for SCCmec characterization

| Region | Target

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ccr | mec class | J1 | J2/J3 | |

| Core | ccr1 | A | ||

| ccr2 | A1a | |||

| ccr3 | A.3 | |||

| ccr4 | A.4 | |||

| ccr5 | B | |||

| ccrC-VT | B1b | |||

| C2 | ||||

| E | ||||

| Fb | ||||

| Gc | ||||

| Junkyard | a | pT181, dcs | ||

| b | pI258, pls | |||

| c | pUB110, kdp | |||

| d | Tn4001, 3A.2.1 (unique) | |||

| g | Tn554 MLS | |||

| ΨTn554 (cad) | ||||

| IS256-dcs | ||||

| IS256-Tn4001 | ||||

| IS256-mecI | ||||

Two separate mec classes have been termed B1. For this analysis, the mec class described by Lim et al. remains B1 and the mec configuration described by Shukla et al. has been renamed mec class F (23, 39).

The novel mec class featured in SCCmecZH47 at the time of writing was unnamed; therefore, the tentative name of mec class G was used (GenBank accession no. AM292304).

TABLE 2.

Forty-six SCCmec variants collated for this studya

| SCCmec class | SCCmec (n = 46) | Uniform nomenclatureb | Defining characteristics

|

PCR genotypec | Strain/isolate and/or sequence (accession no.) | Reference(s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ccr and mec class | J1 | J2 and J3 | ||||||

| I (1B) | I | 1B.1.1 | ccr1, mec class B | pls | I | NCTC10442 (AB033763), COL (CP000046) | 15 | |

| I variant | (1B.2.1) | ccr1, mec class B | No pls | I | PhII | 38 | ||

| IA | 1B.1.2 | ccr1, mec class B | pls | pUB110 | I | PER34 | 31 | |

| IA variant | (1B.1.3) | ccr1, mec class B | pls | IS256 | I | PER184 | 31 | |

| IA variant | (1B.1.4) | ccr1, mec class B | pls | IS256 and pUB110 | I | PER88 | 31 | |

| II (2A) | IIa | 2A.1.1 | ccr2, mec class A | kdp operon | pUB110 | II | N315 (D86934), MRSA252 (BX571856) | 16 |

| II variant | 2A.1.2 | ccr2, mec class A | kdp operon | II | Not described | 3 | ||

| II variant | (2A.1.3) | ccr2, mec class A | kdp operon | pUB110 and no dcs | II | Not described | 3 | |

| IIA | 2A.3.1 | ccr2, mec class A.4 (IS1182) | J1 of IVb (2B.2.1) | Tn554 and pUB110 | II NV | Not described | 38 | |

| IIB | 2A.3.2 | ccr2, mec class A | J1 of IVb (2B.2.1) | pUB110 | II | AJ810123 | 38 | |

| IIC | 2A.3.3 | ccr2, mec class A.3 (IS1182) | J1 of IVb (2B.2.1) | Tn554 and pUB110 | II NV | Not described | 38 | |

| IID | 2A.3.4 | ccr2, mec class A.4 (IS1182) | J1 of IVb (2B.2.1) | Tn554 | II NV | Not described | 38 | |

| IIE | 2A.3.5 | ccr2, mec class A.3 (IS 1182) | J1 of IVb (2B.2.1) | Tn554 | II NV | AR13.1/330.2 (AJ810120) | 38 | |

| IIb | 2A.2 | ccr2, mec class A | Unique sequence for 2A.2 | IS256, Tn554 | II | JCSC3063 (AB127982) | 12 | |

| IIb variant | (2F.1.1)d | ccr2, mec class F | kdp operon | dcs and no pUB110 | NV | Not described | 40 | |

| III (3A) | III | (3A.1.1) | ccr3, mec class A | Tn554 MLS, pT181, and pI258 | III | HUSA304 | 23, 31 | |

| III | (3A1.1.1)e | ccr3, mec class A1 (ΔmecR1) | Tn554 MLS, pT181, and pI258 | III | 85/2082 (AB037671), ANS46 | 15, 31 | ||

| IIIA | 3A.1.2 | ccr3, mec class A | No pT181 or ips | III | HU25 (AF422651 to AF422696) | 31 | ||

| IIIB | 3A.1.3 | ccr3, mec class A | No pT181, pI258, or Tn554 | III | HDG2 | 31 | ||

| III variant | (3A.1.5) | ccr3, mec class A | No Tn554 | III | R35 | 31 | ||

| III variant | (3A.1.4) | ccr3, mec class A | pUB110 | III | 15814-9852 | 41 | ||

| III variant | (3A.2.1) | ccr3, mec class A | Tn554 cad with tnpA | III | 85/3907 | 18 | ||

| III variant | (3A.3.1) | ccr3, mec class A | Tn554 MLS | III | 85/961 | 18 | ||

| III variant | (3A.4.1) | ccr3, mec class A | pls | dcs | III | DOM068 | 5 | |

| III variant | (3A.1.6) | ccr3, mec class A | dcs | III | HSA10 | 1 | ||

| IV (2B) | IVa | 2B.1 | ccr2, mec class B | Specific for 2B.1 (IVa) | IVa | MW2 (BA000033), CA05 (AB063172) | 25 | |

| IVb | 2B.2.1 | ccr2, mec class B | Specific for 2B.2.1 (IVb) | IVb | 8/6-3P (AB063173) | 25 | ||

| IVc | 2B.3.1 | ccr2, mec class B | Specific for 2B.3.1 (IVc) | Tn4001 | IVc | MR108 (AB096217) | 18 | |

| IVc variant | 2B.3.2 | ccr2, mec class B | Specific for 2B.3.1 (IVc) | No Tn4001 | IVc | 2314 (AY271717) | 27 | |

| IVd | 2B.4 | ccr2, mec class B | Specific for 2B.4 (IVd) | IVd | JCSC4469 (AB097677) | 12 | ||

| IVE | 2B.3.3 | ccr2, mec class B | Identical to 2B.3.1 (IVc) | Unique left extremity sequence | IVc | AR43/3330.2 (AJ810121) | 38 | |

| IVF | 2B.2.2 | ccr2, mec class B | Identical to 2B.2.1 (IVb) | Unique left extremity sequence | IVb | AR43 | 38 | |

| IVg | 2B.5 | ccr2, mec class B | Specific for 2B.5 (IVg) | IVb | M03-68 (DQ106887) | 22 | ||

| IV variant | (2B.6) | ccr2, mec class B | Different than IVa, -b, -c, or -d | IV NV | SD179-1 | 12 | ||

| IV variant | 4B | ccr4, mec class B | NT | HDE288 (AF411935) | 31 | |||

| IV variant | (2B.1.2) | ccr2, mec class B | IS256 | IVa | BARGII17 | 31, 34 | ||

| IVA variant | 2B.N.2 | ccr2, mec class B | pUB110 | IVa | PER2 | 3, 30 | ||

| V (5C) | V | 5C.1 | ccr5, mec class C2 | hsd | V | WIS (AB121219) | 17 | |

| V variant | (5B.1) | ccr5, mec class B | No details described | NV | 04-17489 | 28 | ||

| V variant | (5B1.1) | ccr5, mec class B1 | No details described | NV | WBG8404 | 28 | ||

| V variant | (5E.1) | ccr5, mec class E | No details described | NV | WBG10198 | 28 | ||

| VT | (5C2.1) | ccrC2, mec class C2 | No details described | V | TSGH 17 | 2 | ||

| V variant | (5/2G.1) | ccr5 and ccr2, mec class C2 | hsd | NV | ZH 47 (AM292304) | Not published | ||

| V variant | (5/1C.1.1) | ccr5 and ccr1, mec class C2 | No details described | pT181 | NV | B827549 | This study; 41 | |

| Other | NV | (2C.1) | ccr2, mec class C2 | No details described | NV | 04-16419 | 28 | |

| Truncated | IS431, pUB110, and dcs | NT | 479968 | 6 | ||||

Table adapted from Chongtrakool et al. (4) with permission.

Uniform nomenclature values in parentheses denote tentative naming of unnamed variants as defined by Chongtrakool et al. (4).

Hypothetical SCCmec genotype using standard PCR assays for ccr, mec class, and the 2B J1 regions a, b, c, and d. NV and NT indicate a new variant and a nontypeable variant, respectively.

Shukla et al. described this isolate as a SCCmec 2A variant (40).

Identification of a resolution-optimized set of binary targets, without constraints.

The database of binary gene variation was converted into a pseudo-sequence alignment (see Materials and Methods) and analyzed using Minimum SNPs for sets of markers that provide a high D. For the first experiment, a set of binary markers was derived from the data in Table 2 simply on the basis of maximization of D, with no attempt to make the results consistent with previously described typing methods. It was determined that all 46 SCCmec variants can be completely resolved by interrogating 22 of the 34 binary targets. Table 3 shows the resolving powers of the best 6-, 9-, 12-, and 15-target sets, which differentiate 21, 29, 35, and 39 of the 46 variants, respectively.

TABLE 3.

Resolution-optimized sets of binary targets, selected without constraints

| SCCmec class | SCCmec variants identified using a set ofa:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 targets (ccr2, Tn554 MLS, dcs, pUB110, mec class A, and J1b) | 9 targets (previous 6 plus mec class C2, IS256-dcs, and pT181) | 12 targets (previous 9 plus mec class B, ccr1, and mec class A.3) | 15 targets (previous 12 plus J1a, J1c, and pls) | |

| 1B (I) | 1B.1.1 | 1B.1.1 | 1B.1.1 | 1B.1.1 |

| (1B.2.1) | (1B.2.1) | (1B.2.1) | (1B.2.1) | |

| 4B* | 4B* | 4B | 4B | |

| (1B.1.3) | 1B.1.3) | (1B.1.3) | (1B.1.3) | |

| 1B.1.2 | 1B.1.2 | 1B.1.2 | 1B.1.2 | |

| Truncated* | Truncated* | Truncated | Truncated | |

| (1B.1.4) | (1B.1.4) | (1B.1.4) | (1B.1.4) | |

| 2A (II) | 2A.3.1 | 2A.3.1 | 2A.3.1 | 2A.3.1 |

| 2A.3.3 | 2A.3.3 | 2A.3.3 | 2A.3.3 | |

| 2A.3.4 | 2A.3.4 | 2A.3.4 | 2A.3.4 | |

| 2A.3.5 | 2A.3.5 | 2A.3.5 | 2A.3.5 | |

| 2A.1.1 | 2A.1.1 | 2A.1.1 | 2A.1.1 | |

| 2A.3.2 | 2A.3.2 | 2A.3.2 | 2A.3.2 | |

| 2A.2 | 2A.2 | 2A.2 | 2A.2 | |

| 2A.1.2 | 2A.1.2 | 2A.1.2 | 2A.1.2 | |

| (2A.1.3) | (2A.1.3) | (2A.1.3) | (2A.1.3) | |

| (2F.1.1) | (2F.1.1) | (2F.1.1) | (2F.1.1) | |

| 3A (III) | 3A.1.1 | 3A.1.1 | 3A.1.1 | 3A.1.1 |

| (3A.2.1) | (3A.2.1) | (3A.2.1) | (3A.2.1) | |

| (3A.3.1) | (3A.3.1) | (3A.3.1) | (3A.3.1) | |

| 3A.1.2 | 3A.1.2 | 3A.1.2 | 3A.1.2 | |

| 3A.1.3 | 3A.1.3 | 3A.1.3 | 3A.1.3 | |

| (3A.1.5) | (3A.1.5) | (3A.1.5) | (3A.1.5) | |

| (3A.1.6) | (3A.1.6) | (3A.1.6) | (3A.1.6) | |

| (3A.4.1) | (3A.4.1) | (3A.4.1) | (3A.4.1) | |

| (3A1.1.1) | (3A1.1.1) | (3A1.1.1) | (3A1.1.1) | |

| (3A.1.4) | (3A.1.4) | (3A.1.4) | (3A.1.4) | |

| 2B (IV) | 2B.4 | 2B.4 | 2B.4 | 2B.4 |

| (2B.6) | (2B.6) | (2B.6) | (2B.6) | |

| 2B.1 | 2B.1 | 2B.1 | 2B.1 | |

| 2B.3.2 | 2B.3.2 | 2B.3.2 | 2B.3.2 | |

| (2B.1.2) | (2B.1.2) | (2B.1.2) | (2B.1.2) | |

| 2B.3.1 | 2B.3.1 | 2B.3.1 | 2B.3.1 | |

| 2B.3.3 | 2B.3.3 | 2B.3.3 | 2B.3.3 | |

| (5/2G.1)* | (5/2G.1)* | (5/2G.1) | (5/2G.1) | |

| (2C.1)* | (2C.1) | (2C.1) | (2C.1) | |

| 2B.2.1 | 2B.2.1 | 2B.2.1 | 2B.2.1 | |

| 2B.5 | 2B.5 | 2B.5 | 2B.5 | |

| 2B.N.2 | 2B.N.2 | 2B.N.2 | 2B.N.2 | |

| 2B.2.2 | 2B.2.2 | 2B.2.2 | 2B.2.2 | |

| 5C (V) | 5C.1 | 5C.1 | 5C.1 | 5C.1 |

| (5C2.1) | (5C2.1) | (5C2.1) | (5C2.1) | |

| (5B1.1) | (5B1.1) | (5B1.1) | (5B1.1) | |

| (5E.1) | (5E.1) | (5E.1) | (5E.1) | |

| (5B.1) | (5B.1) | (5B.1) | (5B.1) | |

| (5/1C.1.1) | (5/1C.1.1) | (5/1C.1.1) | (5/1C.1.1) | |

| No. of variants resolved (D) | 21/46 (0.9507) | 29/46 (0.9768) | 35/46 (0.9855) | 39/46 (0.9923) |

Horizontal lines indicate discrimination by the respective sets of binary targets. The discriminatory power increases as additional targets are added, so the number of horizontal lines increases from left to right. SCCmec variants in parentheses were named in this study. Asterisks indicate variants grouped with unrelated variants.

These targets were then compared with those used in currently extant SCCmec typing methods, with respect to their identity, resolving power, and whether the variants they define correspond with current SCCmec classification schemes. Current PCR-based SCCmec typing generally makes use of 10 targets (ccr1, -2, -3, and -5, mec classes A, B, and C, and three junkyard regions from type 2B) to assign a SCCmec element to one of the five major types and also provide some subtyping information. When tested against the data set containing 46 variants, these 10 targets discriminated 18 genotypes. In comparison, the first 10 targets derived on the basis of D maximization discriminated 32 genotypes. This supports our conjecture that binary target identification on the basis of computerized D maximization will provide a superior result to an ad hoc approach. In order to further test this, the resolving powers of randomly selected sets of markers were determined. This always gave a much lower resolving power than marker sets selected on the basis of D maximization (data not shown), thus supporting the utility of our method for target selection.

A resolution-optimized set of binary targets nucleated by ccr1 and ccr5.

It would be desirable for a SCCmec genotyping method to define genotypes consistent with accepted terminology and current models concerning the degrees of relatedness of the different SCCmec variants. In other words, a genotyping method that fails to discriminate some pairs of distantly related SCCmec variants may be regarded as problematic. The genotypes defined by the D-maximized marker set largely met this requirement. However, the six- and nine-target sets were unable to discriminate the unrelated 4B and truncated SCCmec from 1B (I) variants and also the 5/2G.1 and 2C.1 from 2B (IV) variants (Table 3). Accordingly, a second set of resolution-optimized targets was derived using the “Include” function in Minimum SNPs. This forces the program to include a chosen marker(s) in the set. In this instance, ccr1 and ccr5 were forced into the set, because these discriminate the variants that are not discriminated with the original marker set. In this analysis, Minimum SNPs builds marker sets using the set of ccr1 plus ccr5 as a starting point, so in effect the derived marker sets are nucleated by ccr1 and ccr5.

The derived marker sets are very similar to the unconstrained set and provided almost the same resolution. However, the occurrence of incorrectly grouped variants was largely rectified. The only instances of disparate variants being grouped together were 2C.1 with 2B variants and 2B.N.2 with 2A variants when using the six-target set (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Resolution-optimized sets of binary targets nucleated by ccr1 and ccr5

| SCCmec class | SCCmec variants identified using a set ofa:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 targets (ccr1, ccr5, Tn554 MLS, dcs, pUB110, and ccr2) | 9 targets (previous 6 plus J1b, mec class C2, and IS256-dcs) | 12 targets (previous 9 plus mec class A, pT181, and mec class A.3) | 15 targets (previous 12 plus mec class B, J1a, and J1c) | |

| 1B (I) | 1B.1.1 | 1B.1.1 | 1B.1.1 | 1B.1.1 |

| (1B.2.1) | (1B.2.1) | (1B.2.1) | (1B.2.1) | |

| (1B.1.3) | (1B.1.3) | (1B.1.3) | (1B.1.3) | |

| 1B.1.2 | 1B.1.2 | 1B.1.2 | 1B.1.2 | |

| (1B.1.4) | (1B.1.4) | (1B.1.4) | (1B.1.4) | |

| 2A (II) | 2A.1.1 | 2A.1.1 | 2A.1.1 | 2A.1.1 |

| 2A.3.1 | 2A.3.1 | 2A.3.1 | 2A.3.1 | |

| 2A.3.3 | 2A.3.3 | 2A.3.3 | 2A.3.3 | |

| 2A.3.4 | 2A.3.4 | 2A.3.4 | 2A.3.4 | |

| 2A.3.5 | 2A.3.5 | 2A.3.5 | 2A.3.5 | |

| 2A.1.2 | 2A.1.2 | 2A.1.2 | 2A.1.2 | |

| (2F.1.1) | (2F.1.1) | (2F.1.1) | (2F.1.1) | |

| 2A.3.2 | 2A.3.2 | 2A.3.2 | 2A.3.2 | |

| 2B.N.2* | 2B.N.2 | 2B.N.2 | 2B.N.2 | |

| 2A.2 | 2A.2 | 2A.2 | 2A.2 | |

| (2A.1.3) | (2A.1.3) | (2A.1.3) | (2A.1.3) | |

| 3A (III) | 3A.1.1 | 3A.1.1 | 3A.1.1 | 3A.1.1 |

| (3A.2.1) | (3A.2.1) | (3A.2.1) | (3A.2.1) | |

| (3A.3.1) | (3A.3.1) | (3A.3.1) | (3A.3.1) | |

| 3A.1.2 | 3A.1.2 | 3A.1.2 | 3A.1.2 | |

| (3A1.1.1) | (3A1.1.1) | (3A1.1.1) | (3A1.1.1) | |

| 3A.1.3 | 3A.1.3 | 3A.1.3 | 3A.1.3 | |

| (3A.1.5) | (3A.1.5) | (3A.1.5) | (3A.1.5) | |

| (3A.1.4) | (3A.1.4) | (3A.1.4) | (3A.1.4) | |

| (3A.1.6) | (3A.1.6) | (3A.1.6) | (3A.1.6) | |

| (3A.4.1) | (3A.4.1) | (3A.4.1) | (3A.4.1) | |

| 2B (IV) | 2B.1 | 2B.1 | 2B.1 | 2B.1 |

| 2B.3.2 | 2B.3.2 | 2B.3.2 | 2B.3.2 | |

| 2B.4 | 2B.4 | 2B.4 | 2B.4 | |

| (2B.6) | (2B.6) | (2B.6) | (2B.6) | |

| 2B.2.1 | 2B.2.1 | 2B.2.1 | 2B.2.1 | |

| 2B.5 | 2B.5 | 2B.5 | 2B.5 | |

| (2B.1.2) | (2B.1.2) | (2B.1.2) | (2B.1.2) | |

| 2B.3.1 | 2B.3.1 | 2B.3.1 | 2B.3.1 | |

| 2B.3.3 | 2B.3.3 | 2B.3.3 | 2B.3.3 | |

| 2B.2.2 | 2B.2.2 | 2B.2.2 | 2B.2.2 | |

| (2C.1)* | (2C.1) | (2C.1) | (2C.1) | |

| 5C (V) | 5C.1 | 5C.1 | 5C.1 | 5C.1 |

| (5C2.1) | (5C2.1) | (5C2.1) | (5C2.1) | |

| (5B.1) | (5B.1) | (5B.1) | (5B.1) | |

| (5B1.1) | (5B1.1) | (5B1.1) | (5B1.1) | |

| (5E.1) | (5E.1) | (5E.1) | (5E.1) | |

| (5/2G.1) | (5/2G.1) | (5/2G.1) | (5/2G.1) | |

| (5/1C.1.1) | (5/1C.1.1) | (5/1C.1.1) | (5/1C.1.1) | |

| Other | 4B | 4B | 4B | 4B |

| Truncated | Truncated | Truncated | Truncated | |

| No. of variants resolved (D) | 18/46 (0.9391) | 28/46 (0.9729) | 34/46 (0.9836) | 37/46 (0.9903) |

Horizontal lines indicate discrimination by the respective sets of binary targets. SCCmec variants in parentheses were named in this study. Asterisks indicate variants grouped with unrelated variants.

A resolution-optimized target set derived from an input file reflecting SCCmec variant abundances.

An assumption inherent in our approach to identifying resolution-optimized sets of genotyping targets is that the database is a useful surrogate of the population structure. If this is the case, then the resolving power of the targets with respect to the database is a useful measure of their resolving power on actual collections of isolates. This assumption, although unlikely to be completely wrong, may be simplistic. This is because all of the SCCmec variants are not similarly abundant. This could result in a difference between the D value calculated from the database and the D value obtained from actual collections of isolates. A corollary of this is that markers that discriminate between the abundant genotypes should be preferentially included in the marker set if the D for actual collections of isolates is to be maximized.

We addressed this issue by creating an input file for “Minimum SNPs” that contained multiple copies of abundant SCCmec variants. A comprehensive and accurate determination of relative abundances in nature was not practical, so this exercise was carried out somewhat crudely; the published literature was used to make a judgment as to which SCCmec variants are abundant, and these variants were repeated 50 times in the Minimum SNPs input file. It was hypothesized that the derived marker sets would provide a very high performance at discriminating the abundant variants because a marker that discriminated between abundant variants would have a big impact on the D value. It was also predicted that the derived markers would still be effective for discriminating the less-abundant variants from the abundant variants and from each other.

The resolution-optimized marker sets from this exercise are shown in Table 5. The target sets identified are significantly different from the unconstrained and ccr1- and ccr5-nucleated target sets, and interestingly, do not discriminate as many genotypes. However, as expected, this marker set provided a performance superior to the unconstrained and ccr1- and ccr5-nucleated marker sets in resolving the nine SCCmec variants identified as being abundant. There were, however, a small number of instances where the six-target set failed to discriminate rare SCCmec variants from other unrelated SCCmec variants. This was partially rectified by manually promoting the 13th identified target, ccr1, into the six-target set. This discriminates 4B and the aberrant variant we have termed “truncated” from the abundant unrelated variant 1B.1.1. The resulting seven-target set is what is shown in the first column of targets in Table 5. This target set does not discriminate 5/2G.1 and 2C.1 from the abundant unrelated variant 2B3.1. However, the 11-target set does discriminate all these unrelated variants.

TABLE 5.

Resolution-optimized binary target sets derived from an input file reflecting SCCmec variant abundance

| SCCmec | SCCmec variants identified using a set ofa:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 targets (ccr1, dcs, Tn554 MLS, ccr2, mec class A, J1b, and pT181) | 9 targets (previous 7 plus pUB110 and mec class B) | 11 targets (previous 9 plus mec class C2 and J1a) | 13 targets (previous 11 plus pls and IS256-dcs) | Abundant variant | |

| 1B (I) | 1B.1.1 | 1B.1.1 | 1B.1.1 | 1B.1.1 | Yes |

| (1B.1.3) | (1B.1.3) | (1B.1.3) | (1B.1.3) | No | |

| (1B.2.1) | (1B.2.1) | (1B.2.1) | (1B.2.1) | No | |

| 1B.1.2 | 1B.1.2 | 1B.1.2 | 1B.1.2 | No | |

| (1B.1.4) | (1B.1.4) | (1B.1.4) | (1B.1.4) | No | |

| 2A (II) | 2A.1.1 | 2A.1.1 | 2A.1.1 | 2A.1.1 | Yes |

| 2A.1.2 | 2A.1.2 | 2A.1.2 | 2A.1.2 | No | |

| 2A.2 | 2A.2 | 2A.2 | 2A.2 | No | |

| (2A.1.3) | (2A.1.3) | (2A.1.3) | (2A.1.3) | No | |

| 2A.3.2 | 2A.3.2 | 2A.3.2 | 2A.3.2 | No | |

| (2F.1.1) | (2F.1.1) | (2F.1.1) | (2F.1.1) | No | |

| 2A.3.1 | 2A.3.1 | 2A.3.1 | 2A.3.1 | No | |

| 2A.3.3 | 2A.3.3 | 2A.3.3 | 2A.3.3 | No | |

| 2A.3.4 | 2A.3.4 | 2A.3.4 | 2A.3.4 | No | |

| 2A.3.5 | 2A.3.5 | 2A.3.5 | 2A.3.5 | No | |

| 3A (III) | 3A.1.1 | 3A.1.1 | 3A.1.1 | 3A.1.1 | Yes |

| (3A.2.1) | (3A.2.1) | (3A.2.1) | (3A.2.1) | No | |

| (3A.3.1) | (3A.3.1) | (3A.3.1) | (3A.3.1) | No | |

| (3A1.1.1) | (3A1.1.1) | (3A1.1.1) | (3A1.1.1) | No | |

| 3A.1.2 | 3A.1.2 | 3A.1.2 | 3A.1.2 | Yes | |

| (3A.1.4) | (3A.1.4) | (3A.1.4) | (3A.1.4) | No | |

| 3A.1.3 | 3A.1.3 | 3A.1.3 | 3A.1.3 | Yes | |

| (3A.1.5) | (3A.1.5) | (3A.1.5) | (3A.1.5) | No | |

| (3A.1.6) | (3A.1.6) | (3A.1.6) | (3A.1.6) | No | |

| (3A.4.1) | (3A.4.1) | (3A.4.1) | (3A.4.1) | No | |

| 2B (IV) | 2B.1 | 2B.1 | 2B.1 | 2B.1 | Yes |

| (2B.1.2) | (2B.1.2) | (2B.1.2) | (2B.1.2) | No | |

| 2B.3.2 | 2B.3.2 | 2B.3.2 | 2B.3.2 | No | |

| 2B.4 | 2B.4 | 2B.4 | 2B.4 | No | |

| (2B.6) | (2B.6) | (2B.6) | (2B.6) | No | |

| 2B.N.2 | 2B.N.2 | 2B.N.2 | 2B.N.2 | No | |

| 2B.2.1 | 2B.2.1 | 2B.2.1 | 2B.2.1 | Yes | |

| 2B.5 | 2B.5 | 2B.5 | 2B.5 | No | |

| 2B.3.1 | 2B.3.1 | 2B.3.1 | 2B.3.1 | Yes | |

| 2B.3.3 | 2B.3.3 | 2B.3.3 | 2B.3.3 | No | |

| (5/2G.1)* | (5/2G.1)* | (5/2G.1) | (5/2G.1) | No | |

| (2C.1)* | (2C.1)* | (2C.1) | (2C.1) | No | |

| 2B.2.2 | 2B.2.2 | 2B.2.2 | 2B.2.2 | No | |

| 5C (V) | 5C.1 | 5C.1 | 5C.1 | 5C.1 | Yes |

| (5C2.1) | (5C2.1) | (5C2.1) | (5C2.1) | No | |

| (5B1.1) | (5B1.1) | (5B1.1) | (5B1.1) | No | |

| (5E.1) | (5E.1) | (5E.1) | (5E.1) | No | |

| (5B.1) | (5B.1) | (5B.1) | (5B.1) | No | |

| (5/1C.1.1) | (5/1C.1.1) | (5/1C.1.1) | (5/1C.1.1) | No | |

| Other | 4B* | 4B | 4B | 4B | No |

| Truncated* | Truncated | Truncated | Truncated | No | |

| No. of variants resolved | 19/46 (0.8976) | 28/46 (0.9012) | 31/46 (0.9034) | 36/46 (0.9047)b | |

Horizontal lines indicate discrimination by the respective sets of binary targets. SCCmec variants in parentheses were named in this study. Asterisks indicate variants grouped with unrelated SCCmec variants.

Due to the input data set containing repeats of identical sequences, a D value close to 1 cannot be obtained.

To further test the efficacy of this approach, a separate data set containing only the nine abundant variants was assembled and analyzed. “Minimum SNPs” calculated that six of the 34 targets were required to attain a D of 1. These six targets were very different from the marker set in Table 5 and provided poor resolving power with the entire data set, and there were numerous instances of unrelated variants failing to be discriminated (data not shown). Therefore, the approach of using the entire data set, with multiple copies of abundant genotypes, was superior.

mecA SNPs can increase resolving power.

It has previously been reported that the MRSA mecA gene contains several SNPs (37, 39, 44). These are potential genotyping markers that could be used either as replacements for the binary targets selected or to define more SCCmec subtypes. The literature and sequence databases were searched for mecA sequences from characterized SCCmec elements. In total, 25 sequences were retrieved from the NCBI database, and in addition, partial mecA sequence analysis was undertaken on 19 selected isolates from our collection of previously characterized SCCmec elements (41). From this set of 44 partial mecA sequences, eight SNPs in total were identified, three of which were novel (Table 6).

TABLE 6.

SCCmec variants and associated mecA SNP profilesa

| SCCmec class | SCCmec variant | Nucleic acid at mecA SNP positionb

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 75 | 312* | 415* | 438* | 448* | 612* | 675* | 737 | ||

| 1B (I) | 1B.1.1 | A | C | G | T | G | T | T | A/G |

| 2A (II) | 2A.1.1 | A/C | C | G | T | G | T | T | G |

| 2A.3.5 | A | C | G | T | G | T | T | G | |

| 2B (IV) | 2B.1 | A | C | G | T | G | T | T | G |

| 2B.2.1 | A | C | G | T | G | T | T | G | |

| 2B.3.1 | A | C | G | T | G | T | T | A/G | |

| 2B.3.2 | A | C | G | T | G | T | T | A | |

| 2B.3.3 | A | C | G | T | G | T | T | G | |

| 2B.5 | A | C | G | T | G | T | T | A | |

| 3A (III) | 3A.1.1 | A | C | G | T/A | G/A | G | T | A |

| 3A.1.2 | A | A | G | T | G | G | T | A | |

| 3A.1.3 | A | C | G | T | G | T | T | G | |

| 3A.1.4 | A | C | G/A | T | G | T | T | G | |

| 3A.2.1 | A | C | G | T | G | T | T | A | |

| 5C (V) | 5/1C.1.1 | A | C | G | T | G | T | A | G |

| 5C.1 | A | C | G | T | G | T | A | G | |

| 5C2.1 | A | C | G | T | G | T | A | G | |

| 5/2G.1 | A | C | G | T | G | T | A | G | |

To determine whether mecA SNPs add resolution to the binary genes, they were included in a Minimum SNPs analysis as additional data points. Because no precise mecA sequence data could be assigned to many of the SCCmec variants, a new SCCmec data set was created containing only variants with corresponding mecA sequences. In this case, the data used as input into Minimum SNPs was in effect an alignment that contained a region of pseudo-DNA sequence derived from binary gene variation and a region of actual DNA sequence derived from mecA sequences. This data set consisted of 18 of the original 46 SCCmec variants (Table 6). As different mecA SNP profiles were found within identical SCCmec variants, the 34 binary markers in combination with the eight SNPs defined 24 variants. These expanded mixed SNP/binary target profiles were analyzed using “Minimum SNPs,” which revealed that a D of 1.0 was achieved with 9 binary targets and five mecA SNPs. Overall, of these five SNPs, only SNP 737 could be considered a possible replacement for the binary targets, as it was selected at the third position in the Minimum SNPs output. The remaining SNPs were selected at positions 9 and 12 to 14, which demonstrates minimal D-value contribution. The entire marker set is ccr2, Tn554 MLS, mecA737, mec class A, dcs, pT181, ccrC, Jyb, mecA438, ccrC-VT, Tn4001, mecA75, mecA415, and mecA448.

DISCUSSION

It is now generally accepted that a powerful strategy for bacterial genotyping is to interrogate the genome backbone plus one or more hypervariable regions. This generalized approach has been termed “phylogenetic hierarchical assays using nucleic acids” (20). The practice of identifying MRSA clones by a combination of MLST and SCCmec type is an example of this. The widespread adoption of this MRSA genotyping method has proven an impetus to the accumulation of considerable information regarding SCCmec diversity and the development of several specific SCCmec subtyping schemes.

SCCmec has been classified into five major “types,” composed of mec classes and ccr gene identity, and several SCCmec genotyping methods classify the element to this level only (10, 45). The results of our comprehensive search of the literature and the databases emphasized the high diversity of SCCmec and revealed that much of the diversity is invisible to previously published SCCmec typing methods. In addition to the initial characterization of types 1B, 2A, and 3A (I, II, and III) (15), the community-acquired type 2B (IV) (25), and the most recent type 5C (V) (17), more variable and unusual variants have been identified. Of particular interest are variants carrying multiple copies of ccr and instances of new combinations of mec and ccr classes (2, 28).

Our approach to identifying sets of binary markers for genotyping SCCmec differs greatly from previously published methods (21). Genotyping approaches reported to date yield approximately one mec class or ccr gene per marker interrogated. This is needlessly inefficient as the extensive recombination in SCCmec means that resolving power can potentially increase logarithmically rather than arithmetically as more targets are interrogated. Accordingly, rather than identifying binary markers diagnostic for particular classes/types/subtypes, we used a computerized approach that identifies sets of markers that maximize D. What this algorithm does is attempt to identify a marker that splits the known variants into two equal halves and then attempts to find a single marker that splits each of the groups defined by marker 1 into two equal halves, and so forth. In effect, it is a search for markers that are maximally unlinked. This approach proved to be valuable. It provided sets of markers with greater resolving power than equivalently sized sets of markers identified by the traditional approach. Also, the analyses clearly defined a range of options regarding the numbers of markers interrogated and the resolution obtained. These results bore out the prediction that resolution could increase exponentially with the number of targets interrogated; when the numbers of targets was graphed against log(1 − D), the points formed a straight line (data not shown).

The markers identified have obvious potential to inform the design of specific SCCmec genotyping methods around the multiplexing capacity of the technology to be used and/or the resolution required. One intriguing result was the strong consistency between the SCCmec classes and the groups defined by small numbers of resolution-optimized marker sets, even when there were no constraints on marker selection. The fact that maximally unlinked markers define these groups supports the notion that the SCCmec classes indeed represent distinct phylogenetic clusters of this element. The strategy to increase the consistency between genotypes and the relationships between the SCCmec variants by nucleating the marker set with ccr1 and ccr5 proved successful, as was the analysis to identify markers especially efficient at discriminating the abundant SCCmec variants. Overall, our approach to marker selection proved effective and flexible. The marker sets identified provide a wide choice of well-understood options for the design of SCCmec genotyping procedures. This general approach could be applied to any genome region displaying a high degree of binary variability, e.g., the loci encoding the enzymes that synthesize complex antigenically active cell wall-associated polysaccharides.

Rapid interpretation of the results of a genotyping procedure based on the marker sets described here is potentially problematic. It can be done by manually correlating the results with the information in Table 2, but this is quite laborious. However, it can also be done more rapidly using Minimum SNPs, which is able to run in reverse and return all sequences in an alignment that correspond to a user-defined SNP profile.

The utility of including mecA SNPs in the marker set was explored, and it was found that such SNPs define additional SCCmec variants. However, the SNPs are not effective substitutes for binary markers. Of interest were the observations that identical SNP allelic combinations were found in different SCCmec variants while, conversely, different mecA alleles were found in identical SCCmec variants. For example, the first four SCCmec classes (1B, 2A, 3A, and 2B) each carry the most abundant mecA sequence, while seven of the nine mecA sequences are found in type 3A. This suggests that some SCCmec variants are very much older than others or that there has been recombination between different SCCmec variants. Other observations of interest include variant 2B.1 (IVa) exclusively carrying the most numerous mecA sequence, which is different from the mecA sequence in the closely related variant 2B.3.1 (IVc), and the complete linkage found between ccr5 and a particular mecA sequence (Table 6). It was also observed that two SNP profiles were primarily associated with mec class B, while seven SNP profiles were associated with mec classes A and C. It was concluded that mecA SNPs constitute a possible means of increasing resolving power, with inclusion of the SNP data increasing the number of genotypes. However, the mecA SNPs have only a limited potential use as replacements for the binary markers, especially considering that it is more technically straightforward to assay for the presence of a binary marker than to interrogate a SNP.

Recently, our research group used Minimum SNPs to derive sets of seven (35, 41) or eight (14, 26) resolution-optimized SNPs from the S. aureus MLST database. The genotypes defined by these SNP sets display a high level of consistency with the S. aureus clonal complex structure as revealed by eBURST analysis of the MLST database. A combinatorial MRSA typing method that interrogated these SNPs plus, e.g., the first seven targets in Table 5 (ccr1, dcs, Tn554 MLS, ccr2, mec class A, J1b, and pT181) would be a method of MRSA clone identification that would provide sufficient resolution for many purposes and would be easily adaptable to standardized real-time PCR, medium-density array, or “lab on a chip” technologies. Additional resolution for exploring small-scale epidemiological questions (e.g., in the practice of infection control) could be provided by interrogating one or more variable-number tandem repeat loci. This also could be done in a real-time PCR device by Tm measurement.

In conclusion, this study has demonstrated the effectiveness and flexibility of a systematic computer-assisted approach to deriving genotyping targets from loci displaying high levels of complex binary gene variation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank E. P. Price for scientific advice.

This work was supported by the Cooperative Research Centres Program of the Australian Federal Government.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 21 May 2007.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aac.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aires de Sousa, M., and H. de Lencastre. 2003. Evolution of sporadic isolates of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in hospitals and their similarities to isolates of community-acquired MRSA. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:3806-3815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyle-Vavra, S., B. Ereshefsky, C. C. Wang, and R. S. Daum. 2005. Successful multiresistant community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus lineage from Taipei, Taiwan, that carries either the novel staphylococcal chromosome cassette mec (SCCmec) type VT or SCCmec type IV. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:4719-4730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cha, H. Y., D. C. Moon, C. H. Choi, J. Y. Oh, Y. S. Jeong, Y. C. Lee, S. Y. Seol, D. T. Cho, H. H. Chang, S. W. Kim, and J. C. Lee. 2005. Prevalence of the ST239 clone of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and differences in antimicrobial susceptibilities of ST239 and ST5 clones identified in a Korean hospital. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:3610-3614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chongtrakool, P., T. Ito, X. X. Ma, Y. Kondo, S. Trakulsomboon, C. Tiensasitorn, M. Jamklang, T. Chavalit, J. H. Song, and K. Hiramatsu. 2006. Staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated in 11 Asian countries: a proposal for a new nomenclature for SCCmec elements. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:1001-1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deurenberg, R. H., C. Vink, G. J. Oudhuis, J. E. Mooij, C. Driessen, G. Coppens, J. Craeghs, E. De Brauwer, S. Lemmen, H. Wagenvoort, A. W. Friedrich, J. Scheres, and E. E. Stobberingh. 2005. Different clonal complexes of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus are disseminated in the Euregio Meuse-Rhine region. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:4263-4271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donnio, P. Y., D. C. Oliveira, N. A. Faria, N. Wilhelm, A. Le Coustumier, and H. de Lencastre. 2005. Partial excision of the chromosomal cassette containing the methicillin resistance determinant results in methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:4191-4193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dorrell, N., J. A. Mangan, K. G. Laing, J. Hinds, D. Linton, H. Al-Ghusein, B. G. Barrell, J. Parkhill, N. G. Stoker, A. V. Karlyshev, P. D. Butcher, and B. W. Wren. 2001. Whole genome comparison of Campylobacter jejuni human isolates using a low-cost microarray reveals extensive genetic diversity. Genome Res. 11:1706-1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Enright, M. C., D. A. Robinson, G. Randle, E. J. Feil, H. Grundmann, and B. G. Spratt. 2002. The evolutionary history of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:7687-7692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fitzgerald, J. R., D. E. Sturdevant, S. M. Mackie, S. R. Gill, and J. M. Musser. 2001. Evolutionary genomics of Staphylococcus aureus: insights into the origin of methicillin-resistant strains and the toxic shock syndrome epidemic. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:8821-8826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Francois, P., G. Renzi, D. Pittet, M. Bento, D. Lew, S. Harbarth, P. Vaudaux, and J. Schrenzel. 2004. A novel multiplex real-time PCR assay for rapid typing of major staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec elements. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:3309-3312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hakenbeck, R., N. Balmelle, B. Weber, C. Gardes, W. Keck, and A. de Saizieu. 2001. Mosaic genes and mosaic chromosomes: intra- and interspecies genomic variation of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect. Immun. 69:2477-2486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hisata, K., K. Kuwahara-Arai, M. Yamanoto, T. Ito, Y. Nakatomi, L. Cui, T. Baba, M. Terasawa, C. Sotozono, S. Kinoshita, Y. Yamashiro, and K. Hiramatsu. 2005. Dissemination of methicillin-resistant staphylococci among healthy Japanese children. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:3364-3372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hunter, P. R., and M. A. Gaston. 1988. Numerical index of the discriminatory ability of typing systems: an application of Simpson's index of diversity. J. Clin. Microbiol. 26:2465-2466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huygens, F., J. Inman-Bamber, G. R. Nimmo, W. Munckhof, J. Schooneveldt, B. Harrison, J. A. McMahon, and P. M. Giffard. 2006. Staphylococcus aureus genotyping using novel real-time PCR formats. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:3712-3719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ito, T., Y. Katayama, K. Asada, N. Mori, K. Tsutsumimoto, C. Tiensasitorn, and K. Hiramatsu. 2001. Structural comparison of three types of staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec integrated in the chromosome in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1323-1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ito, T., Y. Katayama, and K. Hiramatsu. 1999. Cloning and nucleotide sequence determination of the entire mec DNA of pre-methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus N315. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:1449-1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ito, T., X. X. Ma, F. Takeuchi, K. Okuma, H. Yuzawa, and K. Hiramatsu. 2004. Novel type V staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec driven by a novel cassette chromosome recombinase, ccrC. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:2637-2651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ito, T., K. Okuma, X. X. Ma, H. Yuzawa, and K. Hiramatsu. 2003. Insights on antibiotic resistance of Staphylococcus aureus from its whole genome: genomic island SCC. Drug Resist. Updates 6:41-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katayama, Y., T. Ito, and K. Hiramatsu. 2000. A new class of genetic element, staphylococcus cassette chromosome mec, encodes methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:1549-1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keim, P., M. N. Van Ert, T. Pearson, A. J. Vogler, L. Y. Huynh, and D. M. Wagner. 2004. Anthrax molecular epidemiology and forensics: using the appropriate marker for different evolutionary scales. Infect. Genet. Evol 4:205-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kondo, Y., T. Ito, X. X. Ma, S. Watanabe, B. N. Kreiswirth, J. Etienne, and K. Hiramatsu. 2007. Combination of multiplex PCRs for staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec type assignment: rapid identification system for mec, ccr, and major differences in junkyard regions. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:264-274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwon, N. H., K. T. Park, J. S. Moon, W. K. Jung, S. H. Kim, J. M. Kim, S. K. Hong, H. C. Koo, Y. S. Joo, and Y. H. Park. 2005. Staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) characterization and molecular analysis for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and novel SCCmec subtype IVg isolated from bovine milk in Korea. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 56:624-632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lim, T. T., F. N. Chong, F. G. O'Brien, and W. B. Grubb. 2003. Are all community methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus related? A comparison of their mec regions. Pathology 35:336-343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lim, T. T., G. W. Coombs, and W. B. Grubb. 2002. Genetic organization of mecA and mecA-regulatory genes in epidemic methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from Australia and England. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 50:819-824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma, X. X., T. Ito, C. Tiensasitorn, M. Jamklang, P. Chongtrakool, S. Boyle-Vavra, R. S. Daum, and K. Hiramatsu. 2002. Novel type of staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec identified in community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1147-1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McDonald, M., A. Dougall, D. Holt, F. Huygens, F. Oppedisano, P. M. Giffard, J. Inman-Bamber, A. J. Stephens, R. Towers, J. R. Carapetis, and B. J. Currie. 2006. Use of a single-nucleotide polymorphism genotyping system to demonstrate the unique epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in remote aboriginal communities. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:3720-3727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mongkolrattanothai, K., S. Boyle, T. V. Murphy, and R. S. Daum. 2004. Novel non-mecA-containing staphylococcal chromosomal cassette composite island containing pbp4 and tagF genes in a commensal staphylococcal species: a possible reservoir for antibiotic resistance islands in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:1823-1836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Brien, F. G., G. W. Coombs, J. C. Pearson, K. J. Christiansen, and W. B. Grubb. 2005. Type V staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec in community staphylococci from Australia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:5129-5132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okuma, K., K. Iwakawa, J. D. Turnidge, W. B. Grubb, J. M. Bell, F. G. O'Brien, G. W. Coombs, J. W. Pearman, F. C. Tenover, M. Kapi, C. Tiensasitorn, T. Ito, and K. Hiramatsu. 2002. Dissemination of new methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clones in the community. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:4289-4294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oliveira, D. C., and H. de Lencastre. 2002. Multiplex PCR strategy for rapid identification of structural types and variants of the mec element in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:2155-2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oliveira, D. C., A. Tomasz, and H. de Lencastre. 2001. The evolution of pandemic clones of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: identification of two ancestral genetic backgrounds and the associated mec elements. Microb. Drug Resist. 7:349-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oliveira, D. C., S. W. Wu, and H. de Lencastre. 2000. Genetic organization of the downstream region of the mecA element in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates carrying different polymorphisms of this region. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:1906-1910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Price, E. P., F. Huygens, and P. M. Giffard. 2006. Fingerprinting of Campylobacter jejuni by using resolution-optimized binary gene targets derived from comparative genome hybridization studies. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:7793-7803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roberts, R. B., A. de Lencastre, W. Eisner, E. P. Severina, B. Shopsin, B. N. Kreiswirth, A. Tomasz, et al. 1998. Molecular epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in 12 New York hospitals. J. Infect. Dis. 178:164-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robertson, G. A., V. Thiruvenkataswamy, H. Shilling, E. P. Price, F. Huygens, F. A. Henskens, and P. M. Giffard. 2004. Identification and interrogation of highly informative single nucleotide polymorphism sets defined by bacterial multilocus sequence typing databases. J. Med. Microbiol. 53:35-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robinson, D. A., and M. C. Enright. 2003. Evolutionary models of the emergence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:3926-3934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ryffel, C., F. H. Kayser, and B. Berger-Bachi. 1992. Correlation between regulation of mecA transcription and expression of methicillin resistance in staphylococci. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 36:25-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shore, A., A. S. Rossney, C. T. Keane, M. C. Enright, and D. C. Coleman. 2005. Seven novel variants of the staphylococcal chromosomal cassette mec in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from Ireland. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:2070-2083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shukla, S. K., S. V. Ramaswamy, J. Conradt, M. E. Stemper, R. Reich, K. D. Reed, and E. A. Graviss. 2004. Novel polymorphisms in mec genes and a new mec complex type in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates obtained in rural Wisconsin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:3080-3085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shukla, S. K., M. E. Stemper, S. V. Ramaswamy, J. M. Conradt, R. Reich, E. A. Graviss, and K. D. Reed. 2004. Molecular characteristics of nosocomial and Native American community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clones from rural Wisconsin. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:3752-3757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stephens, A. J., F. Huygens, J. Inman-Bamber, E. P. Price, G. R. Nimmo, J. Schooneveldt, W. Munckhof, and P. M. Giffard. 2006. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus genotyping using a small set of polymorphisms. J. Med. Microbiol. 55:43-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taneike, I., T. Otsuka, S. Dohmae, K. Saito, K. Ozaki, M. Takano, W. Higuchi, T. Takano, and T. Yamamoto. 2006. Molecular nature of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus derived from explosive nosocomial outbreaks of the 1980s in Japan. FEBS Lett. 580:2323-2334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van der Zee, A., M. Heck, M. Sterks, A. Harpal, E. Spalburg, L. Kazobagora, and W. Wannet. 2005. Recognition of SCCmec types according to typing pattern determined by multienzyme multiplex PCR-amplified fragment length polymorphism analysis of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:6042-6047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu, C. Y., J. Hoskins, L. C. Blaszczak, D. A. Preston, and P. L. Skatrud. 1992. Construction of a water-soluble form of penicillin-binding protein 2a from a methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolate. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 36:533-539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang, J. A., D. W. Park, J. W. Sohn, and M. J. Kim. 2006. Novel PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis for rapid typing of staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec elements. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:236-238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang, K., J. A. McClure, S. Elsayed, T. Louie, and J. M. Conly. 2005. Novel multiplex PCR assay for characterization and concomitant subtyping of staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec types I to V in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:5026-5033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.