Abstract

The presence of live periosteal progenitor cells on the surface of bone autografts confers better healing than devitalized allograft. We have previously demonstrated in a murine 4 mm segmental femoral bone-grafting model that live periosteum produces robust endochondral and intramembraneous bone formation that is essential for effective healing and neovascularization of structural bone grafts. To the end of engineering a live pseudo-periosteum that could induce a similar response onto devitalized bone allograft, we seeded a mesenchymal stem cell line stably transfected with human bone morphogenic protein-2/β-galactosidase (C9) onto devitalized bone allografts or onto a membranous small intestinal submucosa scaffold that was wrapped around the allograft. Histology showed that C9-coated allografts displayed early cartilaginous tissue formation at day 7. By 6 and 9 weeks, a new cortical shell was found bridging the segmental defect that united the host bones. Biomechanical testing showed that C9-coated allografts displayed torsional strength and stiffness equivalent to intact femurs at 6 weeks and superior to live isografts at 9 weeks. Volumetric and histomorphometric micro–computed tomography analyses demonstrated a 2-fold increase in new bone formation around C9-coated allografts, which resulted in a substantial increase in polar moment of inertia (pMOI) due to the formation of new cortical shell around the allografts. Positive correlations between biomechanics and new bone volume and pMOI were found, suggesting that the biomechanical function of the grafted femur relates to both morphological parameters. C9-coated allograft also exhibited slower resorption of the graft cortex at 9 weeks than live isograft. Both new bone formation and the persistent allograft likely contributed to the improved biomechanics of C9-coated allograft. Taken together, we propose a novel strategy to combine structural bone allograft with genetically engineered mesenchymal stem cells as a novel platform for bone tissue engineering.

INTRODUCTION

Bone graft transplantation is increasingly used as an effective treatment for repair of large bone defects in orthopedic reconstruction procedures. Although autograft remains the gold standard for bone graft transplantation, size limitation, donor site morbidity, and other complications markedly limit its use for repair of large structural defects. On the other hand, allogeneic structural bone graft has been one of the popular choices for clinicians due to its osteoconductive nature, unlimited size, and the absence of donor site morbidity. However, because of the lack of viable cells on processed allografts, healing and incorporation of the grafts are poor. The absence of osteogenesis, osteoinduction, and remodeling within allografts results in slower fusion, accumulation of microdamage, and increased infection rates. These shortcomings have lead to a 10-year outcome failure rate of approximately 60% in clinical allografts.1–8

Toward a better understanding of the molecular and cellular mechanisms involved in structural bone graft incorporation and revascularization, we have established a murine segmental bone-grafting model that recapitulates the salient features of live autograft and processed allograft healing in humans.9–11 Using this model, we have shown that live autografts heal through a robust osteogenic response from periosteum on the graft, whereas healing and neovascularization in devitalized allograft are completely dependent on osteoinductive activity from the host bone. Using live bone graft harvested from Rosa 26A mice, which constitutively express β-galactosidase, we demonstrated that donor periosteal progenitor cells play an essential role in initiating the healing response that eventually leads to complete host-dependent repair and remodeling of the graft.10

Tissue engineering holds great promise for tissue repair and regeneration.12–14 Although reconstruction of small to moderate-sized bone defects using tissue engineering is technically feasible, the repair of large load-bearing defects remains challenging. So far, few of the hard tissue scaffolds have been used clinically for repair of large defects. On the other hand, massive allografts can restore the size and shape of the resected bone. Structural bone allografts possess superior mechanical strength and fracture resistance to that of hard tissue scaffolds, such as ceramics, and therefore remain a better choice for repair of large defects that require immediate support.15,16 Furthermore, the use of allograft has expanded recently because of improved methods of procurement, preparation, and storage.17

To enhance bone allograft performance and prolong allograft longevity, we proposed to apply cell-based tissue-engineering concepts to revitalizing structural bone allografts. In this current study, we seeded a genetically modified bone morphogenic protein (BMP)-2–producing mouse mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) line (C9) onto a bone allograft. We also pre-seeded the cells onto a membranous scaffold derived from small intestinal submucosa (SIS) then wrapped the membrane around bone allografts. Micro-computed tomography (CT) and histological analyses demonstrated that C9 cells on bone graft induced early endochondral bone formation on allograft, followed by formation of a new cortical shell around the bone graft that was completely integrated into the host bone. Biomechanical testing showed that the C9-coated allograft not only displayed better bony union than the allograft, but also restored its strength to that of the live isograft at 6 and 9 weeks post-grafting. These data demonstrated a novel strategy of combining allografts with genetically engineered MSCs for repair of large structural defects.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mouse strains

C57BL/6 mice were originally purchased from Jackson Laboratory. Allogeneic bone grafts were obtained from mice of the 129 strains for implantation into C57BL/6 mice. The University of Rochester Committee of Animal Resources approved all animal surgery procedures.

Bone graft preparation and transplantation

Ten-week-old C57BL/6 mice were anesthetized via intraperitoneal injection with a combination of ketamine and xylazine. A 7–8 mm long incision was made, and the midshaft femur was exposed using blunt dissection of muscles. A 4-mm mid-diaphyseal segment was removed from the femur by osteotomizing the bone using a saw. A 4 mm cortical bone graft was then inserted into the segmental defect and stabilized using a 26-gauge metal pin placed through the intramedullary marrow cavity, as previously described.9,10 The grafting procedures were performed between inbred C57BL/6 mice with identical genetic background (isografts) or between mice with genetically different backgrounds (allografts). For live-bone isograft transplantation, the graft was carefully dissected to remove the muscles without compromising the periosteum and immediately transplanted into the mice. For devitalized bone graft transplantation, allografts were scraped, extensively washed, sterilized with 70% ethanol, rinsed in saline to remove residual ethanol, and fresh frozen at −70°C for at least 1 week before transplantation. Graft healing was followed radiographically using a Faxitron x-ray system (Faxitron X-ray, Wheeling, IL). The grafted femurs were processed for histological testing, micro-CT analyses, and biomechanical testing at the end time points of the experiments.

Cell engraftment on bone or bio-surfaces

Generation of C9 cells was described previously.2 Briefly, cells from the C3H10T1/2 MSC line were stably transfected with a ptTATop-BMP2 plasmid vector that encodes for a tetracycline transactivator and rhBMP-2 (tet-off system). Using the inducible human BMP-2 expression vector, ptTATop-BMP2, the expression of hBMP-2 could be regulated using doxycycline, an analogue of tetracycline, yielding higher levels of gene expression. The cells were further infected with a retrovirus encoding for the β-galactosidase marker gene. The engineered MSCs were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine, 100units/mL penicillin, 100 units/mL streptomycin, and 10% fetal calf serum (Hyclone, Logan, UT). The culture media was supplemented with doxycycline to prevent cell differentiation before implantation. To prepare cellular bone allografts, C9 cells were seeded onto bone allografts at a density of 1.5×105 cells per graft and cultured for an additional hour at 37°C in DMEM before being used to repair the defects. C9 cells were also seeded onto a SIS membrane at a similar density and cultured for 1 h at 37°C. The pre-seeded membranes were then used to wrap around allografts, followed by transplantation into the femoral defect.

Histochemical staining for β-galactosidase and alkaline phosphatase

After the mice were killed, the grafted femurs were harvested, fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, and decalcified in 10% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA). At least 3 non-consecutive 3-mm paraffin-embedded sections were prepared and stained with alcian blue and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and analyzed as previously described.18,19 For β-galactosidase staining, fresh femur samples were fixed in 0.2% glutaraldehyde at 4°C for 4 days and washed twice in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for 15 min. All samples were decalcifed in EDTA at 4°C for 14 days. After complete decalcification, samples were immersed in 30% sucrose at 4°C overnight and then embedded in OCT medium for cryosectioning. Consecutive tissue sections were re-fixed in 0.2% glutaraldehyde for 30 min, followed by 2 washes in PBS. All slides were stained in X-galactosidase solution (0.02% NP40, 10 mM EDTA, 0.02% glutaraldehyde, 0.05% X-galactosidase, and 2 mM magnesium chloride (MgCL2) in phosphate buffer, PH 7.5) for 24 h. Beta-galactosidase-positive cells were visualized and photographed under light microscopy. For alkaline phosphatase (AP) staining, tissue sections were rinsed in PBS 3 times and then washed in AP buffer (100 mM Tris-hydrochloric acid, pH9.5, 100 mM sodium chloride, 10 mM MgCl2) for 10 min, followed by staining with substrates containing 0.2 mg/mL naphthol AS-MX phosphate and 0.4 mg/mL Fast Red TR.

Micro-CT imaging analyses

Grafted femurs were scanned in a micro-CT imaging system (Scanco Medical, Bassersdorf, Switzerland) at a voxel size of 10.5 μm to image bone. From the 2-dimensional slice images generated, an appropriate threshold was chosen for the bone voxels by visually matching thresholded areas to gray-scale images. The threshold and the volume of interest (VOI) covering the entire length of allograft and 50 slices into the host bone at both bone graft junctions were kept constant throughout the analyses for each femur. To measure the new bone volume, contour lines were drawn in the 2-dimensional slice images to exclude the allograft and the old host cortical bone.10 New bone volume and average cross-sectional polar moment of inertia (pMOI) at the region of the graft were calculated based on histomorphometric and MOI programs in the Scanco system. Cross-sectional pMOI is calculated by numerical integration of , pixel-by-pixel about the cross-section’s area-centroid using the parallel axis theorem, thus calculated by: , where is the pMOI, is the pMOI of a pixel, is the area of each pixel, and is the distance of each pixel from the centroid.

Torsional mechanical testing for grafted femurs

After imaging, the ends of the femurs were cemented into 6.35mm square aluminum tubes using poly(methyl methacrylate) in a custom-made jig to ensure axial alignment and maintain a gage length of 5 to 7 mm. Samples were then mounted on an EnduraTec TestBench system (200 N-mm torque cell; Bose Corp., Minnetonka, MN) and tested in torsion at a rate of 1°/sec until failure. To compare data from samples with different gage lengths, rotation data was normalized by the gage length measured before testing. From this, the ultimate torque was found, as well as the torsional rigidity as determined from the linear portion of the curve.20

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as means ± standard errors of the mean. Statistical significance between experimental groups was determined using one-way analysis of variance and a Tukey’s post hoc test (GraphPad Prism). A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Structure–function relationships were determined by calculating correlation coefficients between bone mechanical property and new bone volume around grafts or average cross-sectional pMOI. Linear regression analyses were performed using a computer program (MiniTab, State College, PA).

RESULTS

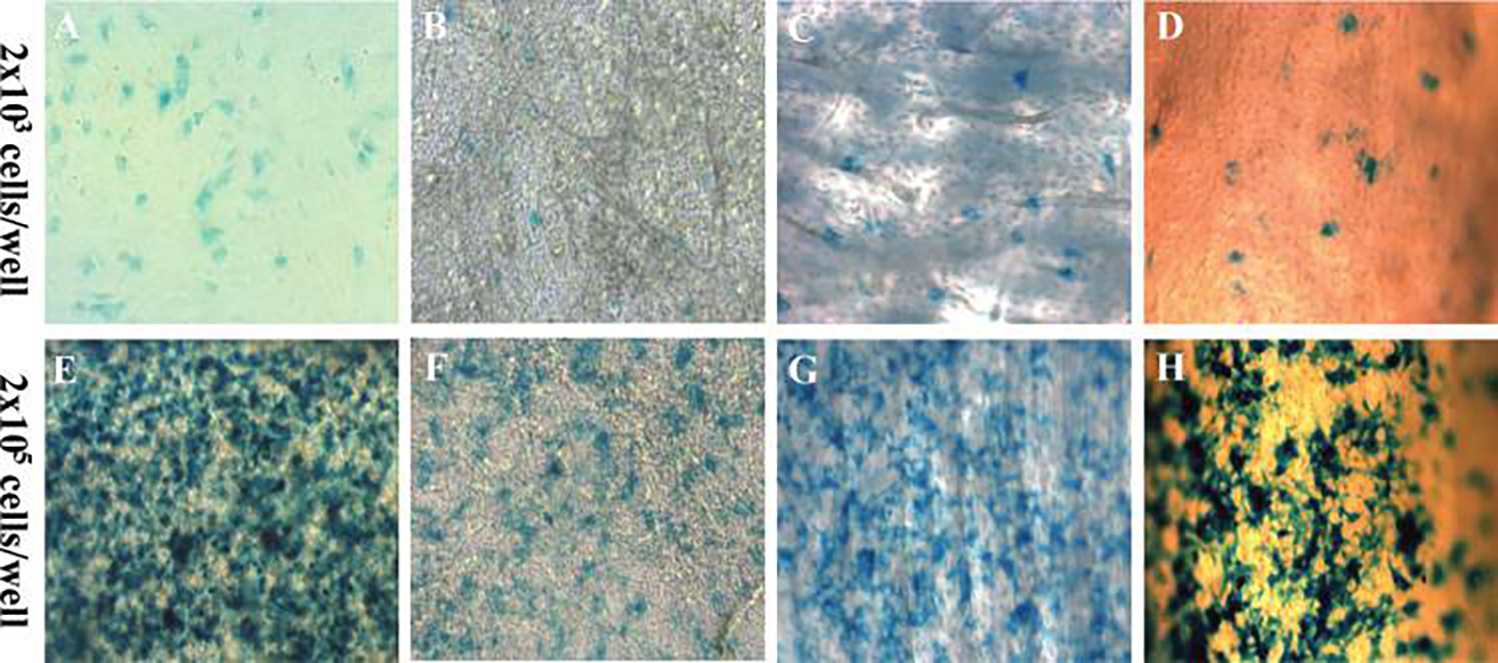

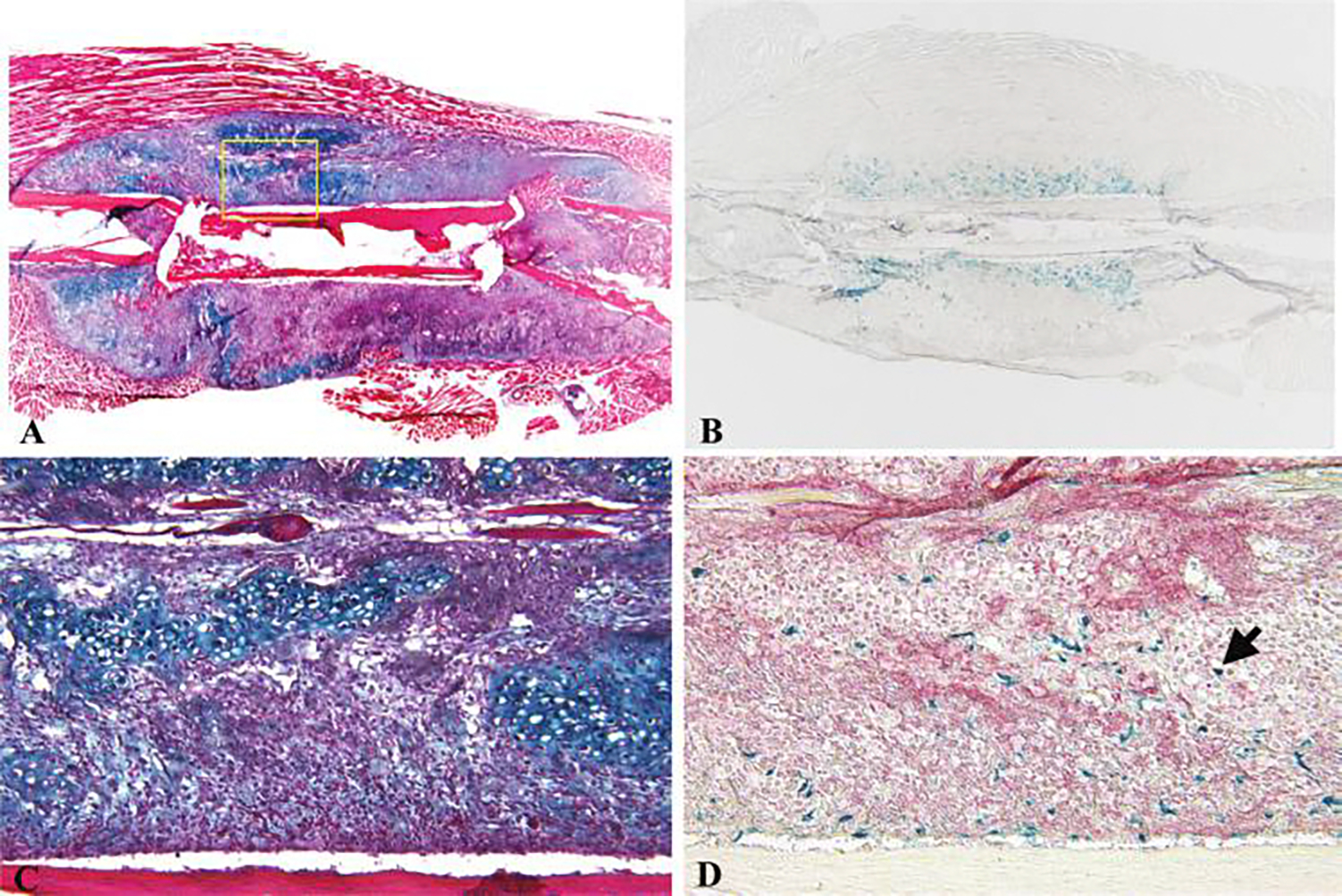

To check the growth and viability of C9-coated allografts, we evaluated C9 cells cultured on various matrices, such as bovine bone wafer, and the processed bone allografts using X-galactosidase staining (Fig. 1). We found that these cells can be easily grown on these bone surfaces, as well as on membranous scaffolds such as SIS. To determine the bio-integration and survival of C9 cells after their transplantation on coated allografts in vivo, we performed X-galactosidase staining on histology sections of grafts that were recovered 7 days after transplantation. These experiments demonstrated a large number of β-galactosidase-positive mesenchymal cells that were adjacent to the allograft (Fig. 2B). Alcian blue/H&E staining of parallel ections showed direct induction of early chondrogenesis on the surface of the C9-coated allografts (Fig. 2A, C), which was not observed in allograft controls (data not shown). Double staining for AP and β-galactosidase showed that AP-positive cells surrounded β-galactosidase-positive cells adjacent to the C9-coated allografts, indicating early induction of differentiation by the C9 cells (Fig. 2D). In addition, we also observed β-galactosidase-positive chondrocytes, indicating that these cells were derived from the transplanted C9 cells (Fig. 2D, arrow). However, these β-galactosidase-positive cells were not readily detected in the healing grafts 14 days after transplantation (data not shown), indicating that they are replaced by host cells during extensive remodeling.

FIG. 1.

Culture of C9 mesenchymal stem cells on scaffold or bone. Bone morphogenic protein-2-producing mesenchymal stem cells (C9) were seeded on plastic surface (A&E), small intestinal submucosa membrane (B&F), bovine bone wafer (C&G), or murine bone allograft (D&H) at the indicated seeding density. Cells were stained using X-galactosidase to determine the resulting seeding density. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/ten.

FIG. 2.

Histologic healing of C9-coated allografts. C9 cells were directly seeded on an allograft and used to repair a 4-mm segmental bone defect in a mouse femur. Alcian blue and hematoxylin and eosin staining sections demonstrated direct induction of early cartilaginous callus on devitalized bone allograft in C9-coated allografts 7 days post-surgery (A&C). X-galactosidase staining in an adjacent section showed numerous β-galactosidase-positive C9 cells within the early periosteal callus (B&D). Alkaline phosphatase staining of the same section showed differentiated alkaline phosphatase–positive mesenchymal cells around the bone allograft (D). (Arrow indicates β-galactosidase-positive chondrocytes.) Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/ten.

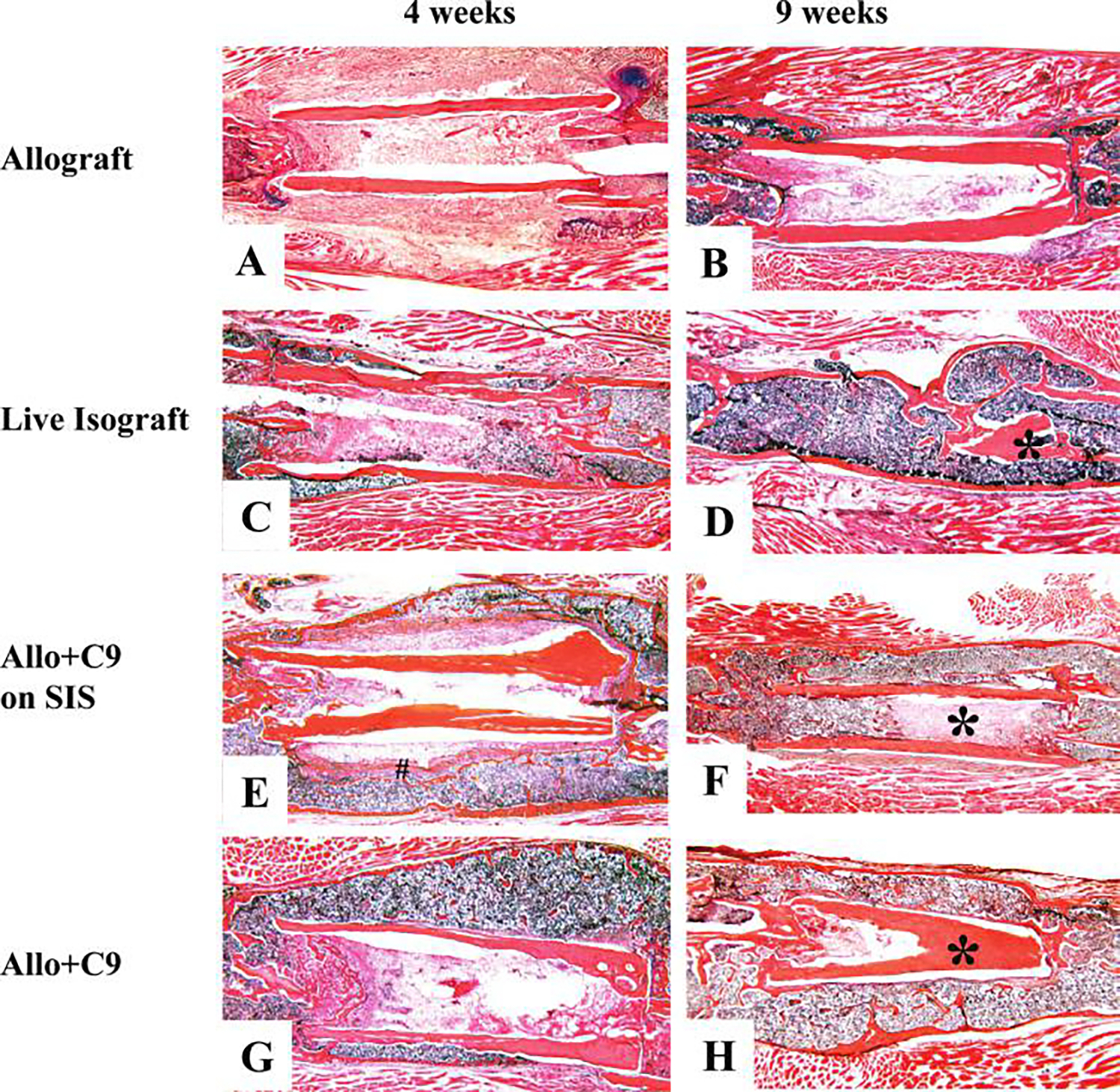

To assess the effects of the C9 cell coating on allograft healing, we compared their histology, with or without the SIS membrane, with that of allograft and live isograft controls at 4 and 9 weeks post-grafting (Fig. 3). In contrast to the allografts, which demonstrated a complete absence of periosteal bone formation, both types of C9-coated allografts displayed robust bone formation along the necrotic cortex at 4 weeks, which was similar to that observed in the live isografts. Furthermore, the engineered grafts demonstrated remarkable healing, as evidenced by a new bridging outer cortical shell with trabecular bone and live marrow elements that spanned the distal and proximal ends of the host bone by 4 weeks post-grafting (Fig. 3C, E, G). By 9 weeks, the original live isograft cortex was largely resorbed, and a solid cortical bone formed, replacing the grafted bone (Fig. 3D). In C9-coated allograft, we found that the resorption of allograft was markedly delayed (Fig. 3F, H). The persistent allograft, together with a solid plate-like cortical shell, formed a contiguous loadbearing structure for the grafted femur (Fig. 3F, H). The analysis of the SIS membrane demonstrated its ability to support C9 cell osteogenesis at 4 weeks, followed by its complete resorption by 9 weeks (Fig. 3E, F). Because we observed a similar healing pattern from both seeding approaches (direct seeding on the graft and seeding on SIS membrane), we focused our radiographic and biomechanical analyses only on C9-allografts without SIS membrane.

FIG. 3.

Induction of periosteal-like new bone callus in C9-coated allografts (Allo + C9). C9 cells were directly seeded on bone allograft or on small intestinal submucosa (SIS) membrane wrapped around the allograft. The cellularized allograft was used to repair a 4 mm segmental defect in the mouse femur. Representative histological sections from allograft (A&B), live isograft (C&D), allograft wrapped with C9 cells pre-seeded on SIS membrane (E&F), or allograft with direct C9 cell seeding (G&H) were obtained at 4 and 9 weeks post-grafting. The absence of periosteal bone formation associated with poor graft incorporation is evident in allograft 4 and 9 weeks post-surgery. In contrast, Allo + C9 produced a contiguous new bone callus with an outer cortical shell at 4 and 9 weeks post-surgery, similar to live isograft at 4 weeks. (* indicates transplanted bone graft, # indicates the residues of SIS). Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/ten.

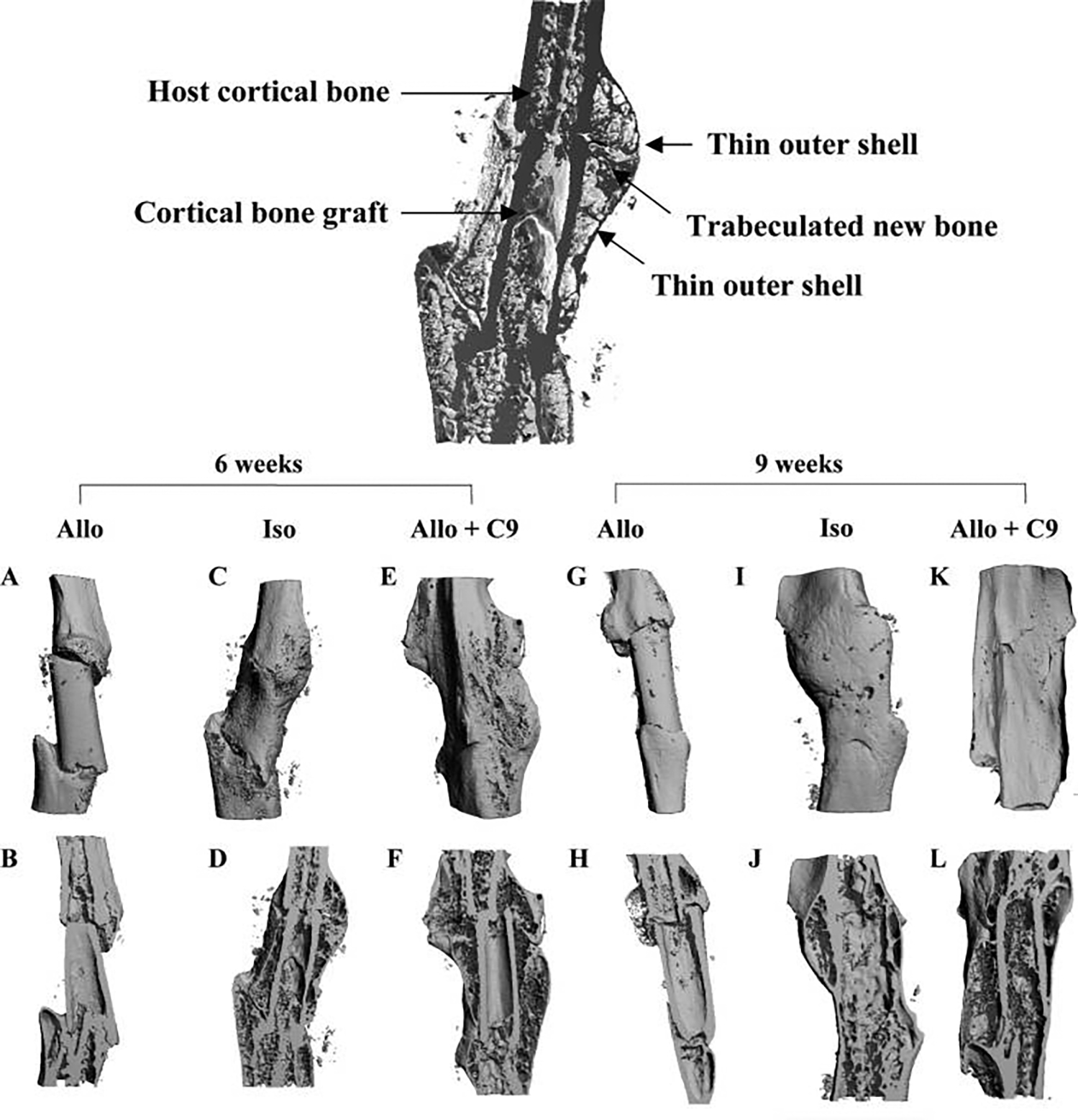

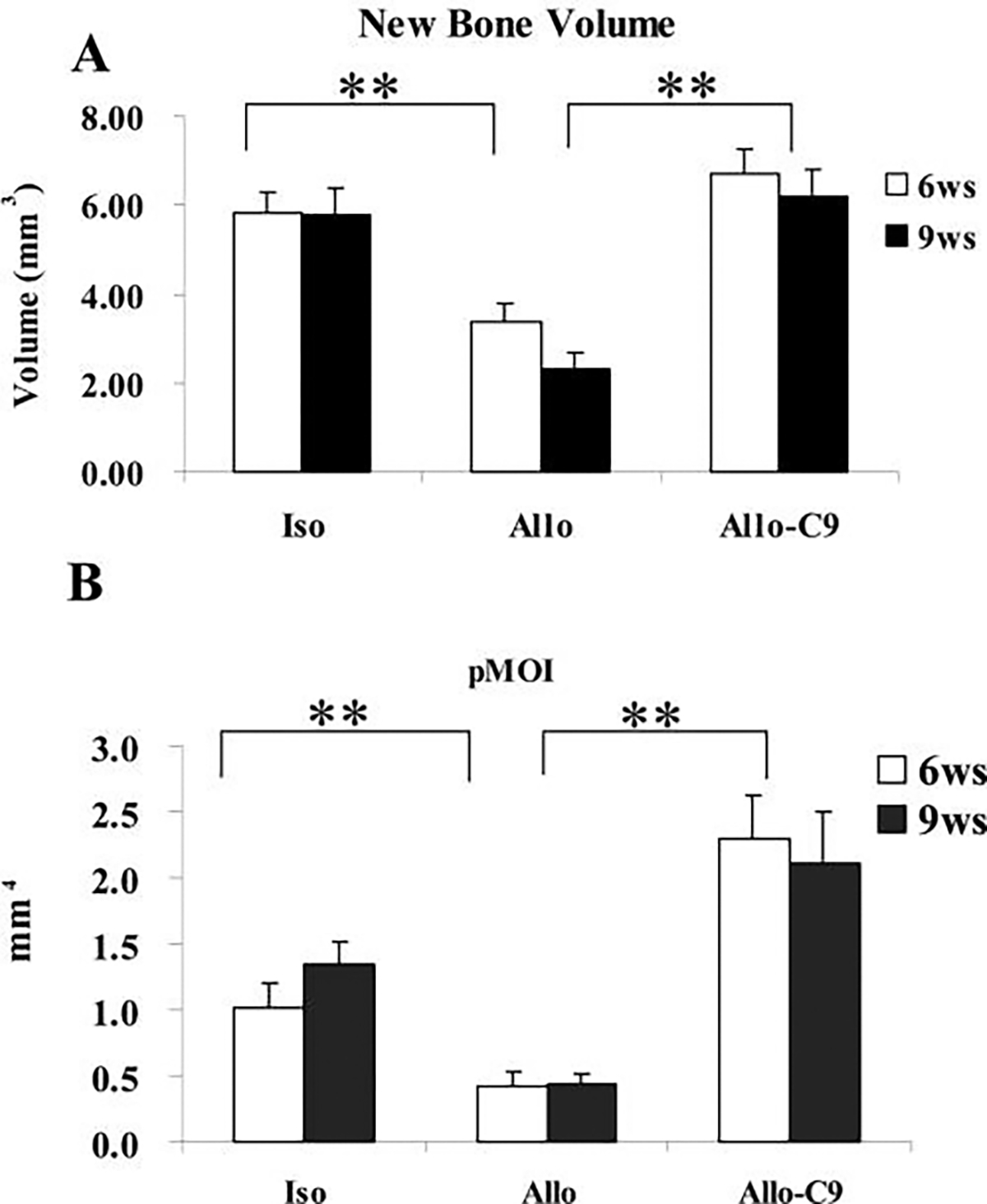

To confirm our histologic findings, micro-CT analyses on allografts, live isografts, and C9-coated allografts were performed at 6 and 9 weeks. Consistent with the histology, assessment of the 3-dimensional reconstructed images of the bone demonstrated the remarkable new bone formation around the C9-coated allografts with bridging union that was similar to the live isografts (Fig. 4). By 9 weeks, graft resorption in C9-coated allografts was markedly delayed, resulting in a load-bearing structure consisting of allograft cortex and the outer cortical shell. Micro-CT volumetric and cross-sectional histomorphometric analyses were performed to measure new bone formation around bone graft, as previously described.10 Approximately 2-fold induction of new bone formation around the allograft was found in C9-coated allografts, comparable with live isograft (Fig. 5A, n = 8, p < 0.01). As a result of the new bone formation, we found that the average cross-sectional pMO) of the grafted femurs, an indicator of the structural contribution to resistance of the femur to torsion, was markedly greater in femurs treated with C9 cells, significantly exceeding the increased pMOI of the live isografts (Fig. 5B, n = 8, p < 0.01).

FIG. 4.

Three-dimensional micro-computed tomography ()imaging of C9-coated allografts (Allo + C9). Image at top center illustrates the structure layers of a healing isografted femur (Iso). Representative micro-CT images were obtained from grafted femurs 6 and 9 weeks post-surgery. Limited bone formation was observed in allograft (Allo) (A&B, G&H). In contrast, extensive new bone formation across bone graft was shown in intact live bone Iso at 6 weeks (C&D). By 9 weeks, live bone graft cortex was resorbed, leaving the outer shell as the major load-bearing structure for the healing bone (I&J). In Allo + C9, periosteal bone formation was restored, which resulted in a contiguous new cortical shell at 6 and 9 weeks post-surgery (E&F, K&L). In addition, graft resorption was markedly delayed to allow the persistent allograft and the outer cortical shell to form a contiguous load-bearing structure.

FIG. 5.

C9-coated allografts (Allo-C9) demonstrate a significant increase in bone formation. New bone volume around allografts (Allo) (A) and average cross-sectional polar moment of inertia of the grafted region (B) were markedly greater in Allo-C9. Data shown are means ± standard errors of the mean. * p < 0.05 (n ≥ 8). Iso, isograft.

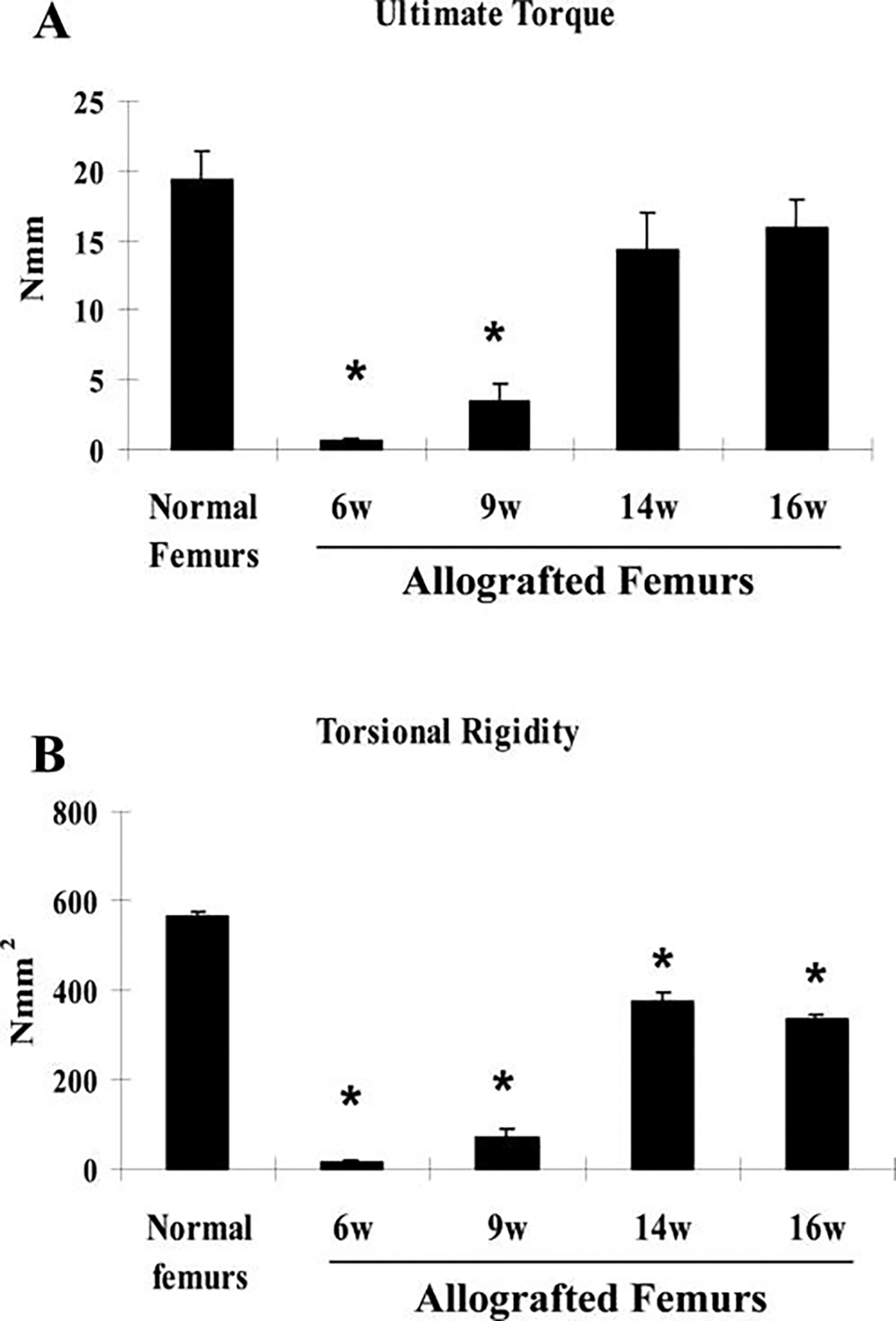

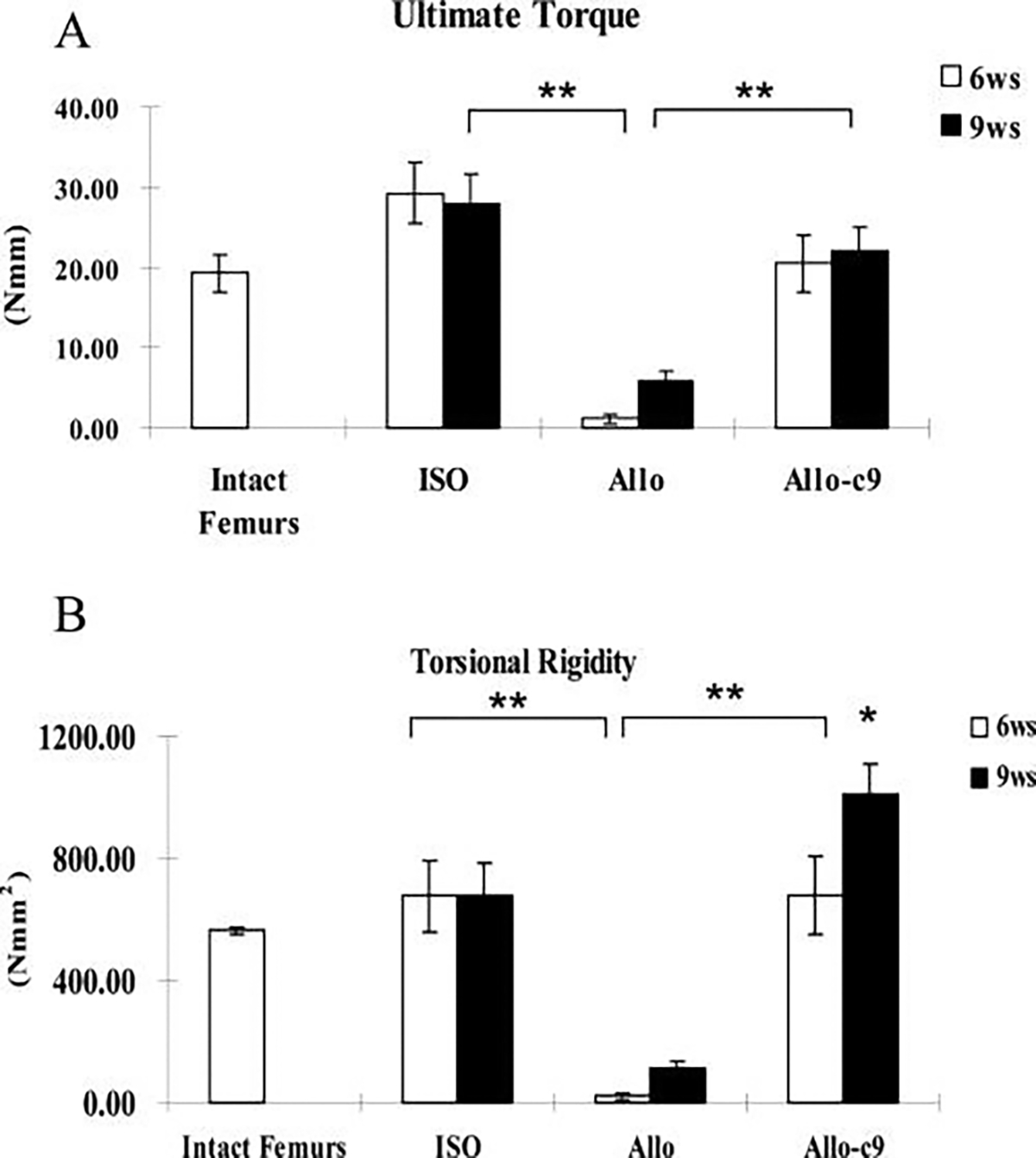

To determine functional osseo-integration of the graft to host bone, torsional testing was conducted to examine mechanical strength of the grafted femurs. Normal age- and sex-matched intact C57/B6 mouse femurs were used as controls. We first examined the mechanical strength of allografted femurs at 6, 9, 14, and 16 weeks post-grafting (Fig. 6A, B). At 6 weeks, ultimate torque and torsional rigidity of the allografted femurs were less than 10% of the intact femoral bone, indicating a non-bony union. The strength (ultimate torque) and the stiffness (torsional rigidity) of the allograft increased over time due to slow incorporation of the graft into host bone. By 16 weeks, allograft gained about 85% of the ultimate torque (n = 6, p > 0.05) and 59% of the torsional rigidity (n = 6, p < 0.05) of the intact femurs. In contrast to allograft, isografted femur gained its full strength at 6 weeks post-grafting, matching normal femur bone (Fig. 7A, B n ≥ 8, p > 0.05). C9 cell treatment markedly accelerated allograft bone incorporation such that, by 6 weeks, the grafted femurs had already been restored to the full strength of normal bone, and by 9 weeks, torsional rigidity was shown to be 60% higher than normal unfractured femurs and 49% higher than isografted femurs (Fig. 7B, n ≥ 8, p < 0.05).

FIG. 6.

Torsional testing indicates inferior biomechanics of allografted femurs. Torsional testing was performed to examine the mechanical properties of allografted femurs at 6, 9, 14, and 16 weeks. Normal intact femurs were used as controls. Each group included 6samples. Data shown are means ± standard errors of the mean. * p < 0.05.

FIG. 7.

C9-coated allografts demonstrate a significant increase in biomechanical strength. Torsional testing was performed to determine the mechanical properties of allografts (Allo), live isografts (ISO), and C9-cell-treated allografts (Allo-C9). Ultimate torque (A) and torsional rigidity (B) were markedly greater in Allo-C9 than in devitalized Allo alone and were similar to those of the ISO. Normal intact femurs were used as controls. Data shown are means ± standard errors of the mean. * p < 0.05 (n ≥ 8).

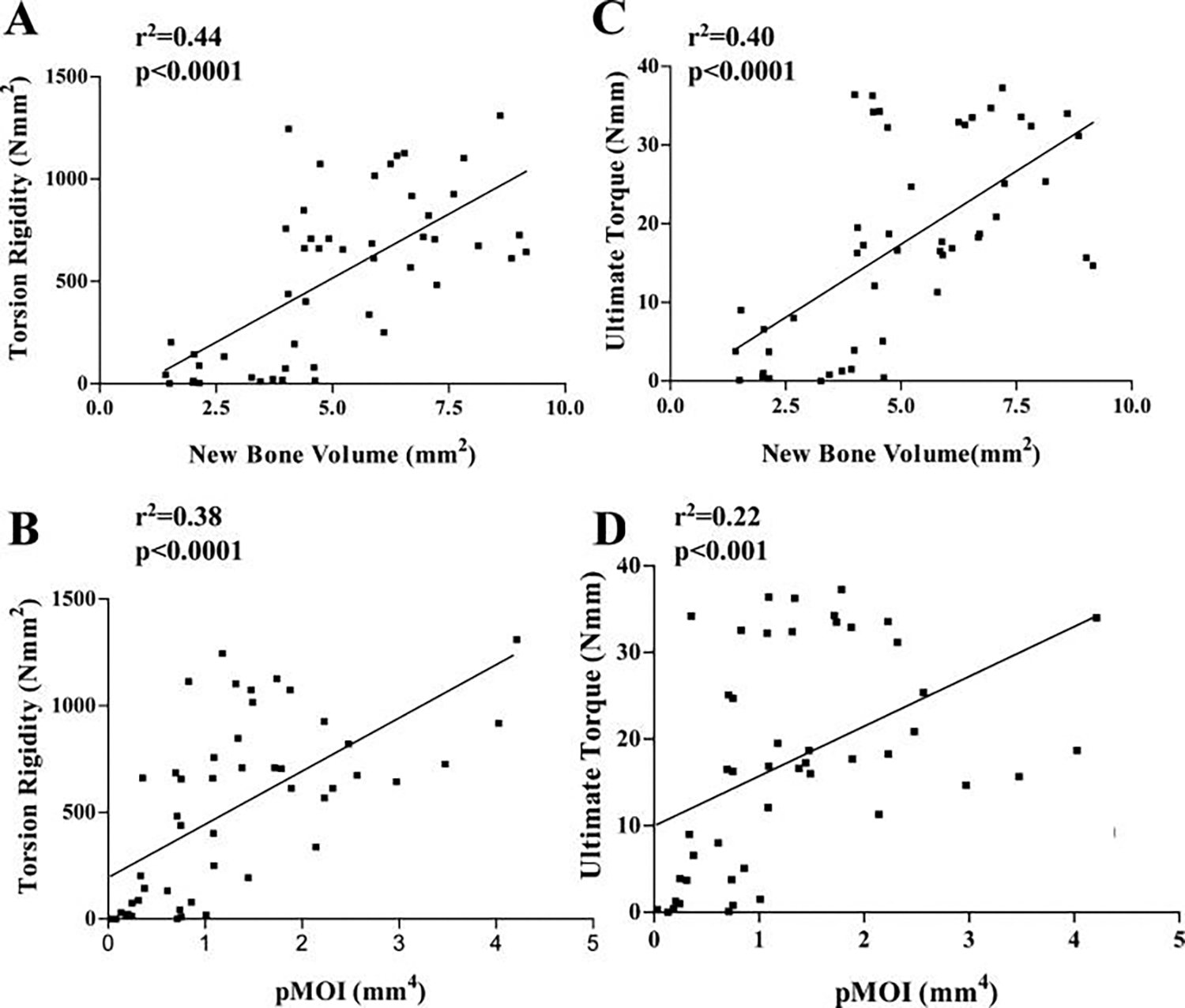

Because torsional testing and micro-CT imaging were performed on the same femurs, we were able to perform linear regression analyses to determine statistical correlation between new bone formation and pMOI and mechanical properties of the grafted femurs. This analysis revealed a positive correlation between new bone volume and torsional rigidity (Fig. 8A, n = 48, coefficient of determination (r2) = 0.44, p < 0.001). Similarly, average cross-sectional pMOI was also found to correlate with torsional rigidity (Fig. 8B, n = 48, r2 = 0.38, p < 0.001). In addition to torsional rigidity, ultimate torque was also shown to have similar correlations with new bone formation (Fig. 8C, r2 = 0.40, p < 0.001) or pMOI (Fig. 8D, r2 = 0.22, p < 0.001).

FIG. 8.

Significant correlation between femur biomechanics and new bone volume and polar moment of inertia. Linear regression analyses were performed to determine the relationship between torsional rigidity, ultimate torque, and new bone volume, or pMOI, of allografts, isografts, and C9-coated allografts. The coefficients of determination (r2) for the correlation between torsional rigidity and new bone volume or pMOI were 0.44 and 0.38, respectively (n = 48, p < 0.001). The r2 for the correlation between ultimate torque and new bone volume or pMOI were 0.40 and 0.22, respectively (n = 48, p < 0.001).

DISCUSSION

Structural allograft has been favored for repair of large bone defects that requires immediate support. Yet the poor long-term outcome of the allograft demands exploration of new alternatives. In this study, we adopted a novel strategy by combining genetically modified BMP-2-producing MSCs with devitalized allograft to repair a 4 mm loadbearing segmental defect. This approach led to the induction of a reparative response on bone graft at day 7 and new bone formation surrounding allograft at later time points. As a result, healing and incorporation of the allograft was markedly enhanced, as evidenced by formation of a cortical shell around bone graft and marked improvement of biomechanics of the grafted femurs.

C9 cells are derived from the mesenchymal cell line C3H10T1/2 with genetic modification to express high levels of rhBMP-2.21–23 Consistent with prior observations, we found that C9 cells not only induced differentiation of host mesenchymal cells to chondrocytes (paracrine), but also formed chondrocytes themselves (autocrine) at the repair site, indicating the involvement of paracrine and autocrine mechanisms of BMP-2 produced from the cells.23,24 Nevertheless, we found that, at day 7 post-implantation, only a few C9 cells underwent differentiation to become chondrocytes. Large numbers of C9 cells remained as early mesenchyme around the allografts. Yet by day 14, only a few β-galactosidase-positive cells were visible at the area of new bone formation, indicating the rapid remodeling of the early callus by host. Taken together, these observations led us to conclude that the genetically engineered MSCs play a major role in the early stage of callus formation in coated allografts.

Using genetically engineered MSCs as a platform for delivery of osteoinductive factors has proven to be an effective approach for bone regeneration.24,25 These cells not only produce growth factors, but also participate in new bone formation. Recent studies have further showed that MSCs have potent immunosuppressive effects, permitting allogeneic transplantation for the purpose of tissue engineering.26,27 In the current study, we implanted C9 cells derived from C3H mice into C57BL/6 mice. Because the implanted cells were not from the same strain, they should be regarded as allogeneic. This allogeneic transplantation led to the successful engraftment of cells in vivo and eventually resulted in marked enhancement of bone healing. These data corroborate the previous finding of Djouad et al., which showed that C9 cells do not elicit any immune response and are still able to form bone when implanted in various allogeneic, immunocompetent mice.28

As an important design element in tissue engineering, 3-dimensional scaffolds gu ide the regeneration activity of the progenitor cells and further support the invasion of bone cells and blood vessels. From a practical standpoint, using flexible membranous scaffold pre-seeded with osteoinductive or osteogenic cells could guide new bone formation in more-complicated shapes than allografts and offer an easier approach for clinical application. For the application of allograft, using a thin and fast degradable scaffold is advantageous because bulky or dense scaffolds could lead to minimal bone ingrowth due to poor oxygen infusion,29,30 and slowly degrading scaffolds may further interfere with the revascularization and remodeling of the allograft.10 Two approaches were used in this study to engraft the osteogenic and osteoinductive cells onto allograft surface: seeding the cells directly on bone graft surface and 2) seeding the cells on micrometer-thin membranous scaffold SIS.31,32 Both approaches led to similar induction of bone formation. Yet we found that membranous scaffold could persist for less than 9 weeks and therefore may disrupt the early integration of new bone on allograft surface (Fig. 3E). Compared with pre-seeded SIS, direct seeding of cells on allograft induced bone formation closer to the allograft surface. From this standpoint, we think that a rapidly degradable scaffold that supports mineralization may be more desirable in this application.

Our current study using torsional biomechanical testing demonstrated that the functional union of devitalized allograft occurred as late as 12 to 16 weeks. Even by then, the biomechanical properties, in particularly torsional rigidity, of the grafted femur were still inferior to that of normal bone (Fig. 6). This observation is consistent with clinical practice, in which rigid fixation has always been used with structural allografts to compensate for slow graft incorporation. C9 cell engraftment markedly accelerated the fusion of the allograft and restored its strength and stiffness to that of normal bone. The restoration of biomechanical function was associated with marked induction of new bone formation, comparable with live isograft. We found that live isograft and C9-coated allograft promoted the formation of a contiguous outer cortical shell around the graft, bridging the defect. As a result, the average cross-sectional pMOI was markedly greater for both bone grafts (Fig. 5). The formation of the outer cortical shell could be due to the uneven distribution of weight bearing, which favors the bony structure located far away from the center of the bone.33,34 Although the exact contribution of this outer shell to the biomechanics of the grafted femurs was not directly assessed, linear regression analyses demonstrated a significant positive correlation between graft biomechanics and the average cross-sectional pMOI in grafted femurs (Fig. 8).

The marked difference between live isograft and C9-coated allograft is the slower resorption of the allograft cortex. By 9 weeks, in live isograft, an estimated 50% to 60% of the grafted cortex was resorbed, leaving the outer cortical shell as the major weight-bearing structure for the grafted femur. In contrast, in C9 samples, allograft cortex persisted with much slower graft resorption. Although further resorption could occur at later time points, as we have previously reported,10 the underlying allograft cortex could be a significant contributing factor to the biomechanics of the C9-coated samples. In particular, the marked increase in torsional rigidity observed at 9 weeks could be due to the coexistence of the outer cortical shell and the persistent inner allograft cortex. In additin, although dead cortical bone is extremely resistant to resorption at the orthotopic site, when placed ectopically, devitalized cortical bone can be rapidly resorbed,35 suggesting that load bearing and later adaptation may be the most important determining factor for graft resorption.

The structure–function relationships of a healing bone can be complex because of the irregular shape and the presence of trabecular and cortical bone in the callus. Identification of structural, geometric, and compositional variables that correlate with the function of the healing bone is important for evaluating healing as well as for devising new therapeutic treatments.36,37 In this current study, we identified 2 variables that positively correlate with torsion biomechanics: the new bone volume around bone graft and the pMOI. However, our analyses only achieved an r2 of 0.48 when combining the two, indicating that other important material and structural parameters may also be important for accurate outcome predictions. Among them, the degree of mineralization and extent of osseointegration between graft and host bone are two important determinants of functional bone graft healing. Future efforts will be directed to developing micro-CT-based quantitative measurements to determine the degree of bone graft incorporation into the host bone.

In summary, our data suggest that reconstitution of a reparative callus via a strategy combining tissue engineering and genetically modified MSC therapy markedly accelerates allograft incorporation and functional restoration, thereby offering a novel and exciting therapeutic approach to the repair of large structural defects.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study is supported by grants from the Musculoskeletal Transplant Foundation, the Coulter Fundation, and the National Institutes of Health (AR051469, AR46545, AR054041, DE017096). We also thank Krista Canary and Barbara Stroyer for their assistance with histological work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Burchardt H 1983. The biology of bone graft repair. Clin Orthop 28–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burchardt H 1987. Biology of bone transplantation. Orthop Clin North Am 18:187–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lord CF, Gebhardt MC, Tomford WW, and Mankin HJ 1988. Infection in bone allografts. Incidence, nature, and treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am 70:369–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berrey BH Jr., Lord CF, Gebhardt MC, and Mankin HJ 1990. Fractures of allografts. Frequency, treatment, and end-results. J Bone Joint Surg Am 72:825–833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Enneking WF, and Mindell ER 1991. Observations on massive retrieved human allografts. J Bone Joint Surg Am 73:1123–1142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hornicek FJ, Gebhardt MC, Tomford WW, Sorger JI, Zavatta M, Menzner JP, and Mankin HJ 2001. Factors affecting nonunion of the allograft-host junction. Clin Orthop 87–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Enneking WF, and Campanacci DA 2001. Retrieved human allografts : a clinicopathological study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 83-A:971–986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wheeler DL, and Enneking WF 2005. Allograft bone decreases in strength in vivo over time. Clin Orthop Relat Res 36–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tiyapatanaputi P, Rubery PT, Carmouche J, Schwarz EM, O’Keefe R J, and Zhang X 2004. A novel murine segmental femoral graft model. J Orthop Res 22:1254–1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang X, Xie C, Lin AS, Ito H, Awad H, Lieberman JR, Rubery PT, Schwarz EM, O’Keefe RJ, and Guldberg RE 2005. Periosteal progenitor cell fate in segmental cortical bone graft transplantations: implications for functional tissue engineering. J Bone Miner Res 20:2124–2137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ito H, Koefoed M, Tiyapatanaputi P, Gromov K, Goater JJ, Carmouche J, Zhang X, Rubery PT, Rabinowitz J, Samulski RJ, Nakamura T, Soballe K, O’Keefe RJ, Boyce BF, and Schwarz EM 2005. Remodeling of cortical bone allografts mediated by adherent rAAV-RANKL and VEGF gene therapy. Nat Med 11:291–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Griffith LG, and Naughton G 2002. Tissue engineering—current challenges and expanding opportunities. Science 295:1009–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caplan AI 2002. In vivo remodeling. Ann N Y Acad Sci 961:307–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bianco P, and Robey PG 2001. Stem cells in tissue engineering. Nature 414:118–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davy DT 1999. Biomechanical issues in bone transplantation. Orthop Clin North Am 30:553–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tencer A, and Johnson K 1994. Biomechanics in Orthopaedic Trauma. Philadelphia, JB: Lippincott. [Google Scholar]

- 17.McLean V December 1993. American Association of Tissue Banks. AATP Information Alert Vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flick LM, Ulrich-Vinther M, Abuzzahab F, Zhang X, Xing L, Dougall W, Anderson D, and Schwarz EM 2001. Effects of RANK blockade on fracture healing. J Orthop Res 21:676–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang X, Schwarz EM, Young DA, Puzas JE, Rosier RN, and O’Keefe RJ 2002. Cyclooxygenase-2 regulates mesenchymal cell differentiation into the osteoblast lineage and is critically involved in bone repair. J Clin Invest 109:1405–1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brodt MD, Ellis CB, and Silva MJ 1999. Growing C57Bl/6 mice increase whole bone mechanical properties by increasing geometric and material properties. J Bone Miner Res 14:2159–2166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hasharoni A, Zilberman Y, Turgeman G, Helm GA, Liebergall M, and Gazit D 2005. Murine spinal fusion induced by engineered mesenchymal stem cells that conditionally express bone morphogenetic protein-2. J Neurosurg Spine 3:47–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pelled G, G ,T., Aslan H., Gazit Z., and Gazit D. 2002. Mesenchymal stem cells for bone gene therapy and tissue engineering. Curr Pharm Des 8:1917–1928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moutsatsos IK, Turgeman G, Zhou S, Kurkalli BG, Pelled G, Tzur L, Kelley P, Stumm N, Mi S, Muller R, Zilberman Y, and Gazit D 2001. Exogenously regulated stem cell-mediated gene therapy for bone regeneration. Mol Ther 3:449–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gazit D, Turgeman G, Kelley P, Wang E, Jalenak M, Zilberman Y, and Moutsatsos I 1999. Engineered pluripotent mesenchymal cells integrate and differentiate in regenerating bone: a novel cell-mediated gene therapy. J Gene Med 1:121–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Turgeman G, Pittman DD, Muller R, Kurkalli BG, Zhou S, Pelled G, Peyser A, Zilberman Y, Moutsatsos IK, and Gazit D 2001. Engineered human mesenchymal stem cells: a novel platform for skeletal cell mediated gene therapy. J Gene Med 3:240–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bartholomew A, Sturgeon C, Siatskas M, Ferrer K, McIntosh K, Patil S, Hardy W, Devine S, Ucker D, Deans R, Moseley A, and Hoffman R 2002. Mesenchymal stem cells suppress lymphocyte proliferation in vitro and prolong skin graft survival in vivo. Exp Hematol 30:42–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsuchida H, Hashimoto J, Crawford E, Manske P, and Lou J 2003. Engineered allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells repair femoral segmental defect in rats. J Orthop Res 21:44–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Djouad F, Plence P, Bony C, Tropel P, Apparailly F, Sany J, Noel D, and Jorgensen C 2003. Immunosuppressive effect of mesenchymal stem cells favors tumor growth in allogeneic animals. Blood 102:3837–3844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muschler GF, Nakamoto C, and Griffith LG 2004. Engineering principles of clinical cell-based tissue engineering. J Bone Joint Surg Am 86-A:1541–1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muschler GF, and Midura RJ 2002. Connective tissue progenitors: practical concepts for clinical applications. Clin Orthop 66–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hodde J 2002. Naturally occurring scaffolds for soft tissue repair and regeneration. Tissue Eng 8:295–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suckow MA, Voytik-Harbin SL, Terril LA, and Badylak SF 1999. Enhanced bone regeneration using porcine small intestinal submucosa. J Invest Surg 12:277–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van der Meulen MC, Beaupre GS, and Carter DR 1993. Mechanobiologic influences in long bone cross-sectional growth. Bone 14:635–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van der Meulen MC, Jepsen KJ, and Mikic B 2001. Understanding bone strength: size isn’t everything. Bone 29:101–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goldberg VM, and Stevenson S Bone Transplantation. 1990. In: Evarts CM., ed. Surgery of the Musculoskeletal System. New York: Churchill Livingstone, Inc., 115–149. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shefelbine SJ, Augat P, Claes L, and Simon U 2005. Trabecular bone fracture healing simulation with finite element analysis and fuzzy logic. J Biomech 38:2440–2450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shefelbine SJ, Simon U, Claes L, Gold A, Gabet Y, Bab I, Muller R, and Augat P 2005. Prediction of fracture callus mechanical properties using micro-CT images and voxel-based finite element analysis. Bone 36:480–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]