Abstract

In insulinoma cell lines proliferation and insulin gene transcription are stimulated by growth hormone and prolactin, which convey their signals through the transcription factors Stat5a and 5b (referred to as Stat5). However, the contribution of Stat5 to the physiology of β-cells in vivo could not be assessed directly since Stat5-null mice die perinataly. To explore the physiological role of Stat5 in the mouse, the corresponding gene locus targeted with loxP sites was inactivated in β-cells using two lines of Cre recombinase expressing transgenic mice. While the RIP-Cre transgene is active in pancreatic β-cells and the hypothalamus, the Pdx1-Cre transgene is active in precursor cells of the endocrine and exocrine pancreas. Mice carrying two floxed Stat5 alleles and a RIP-Cre transgene developed mild obesity, were hyperglycemic and exhibited impaired glucose tolerance. Since RIP-Cre transgenic mice by themselves display some glucose intolerance, the significance of these data is unclear. In contrast, mice, in which the Stat5 locus had been deleted with the Pdx1-Cre transgene, developed functional islets and were glucose tolerant. Mild glucose intolerance occurred with age. We conclude that Stat5 is not essential for islet development but may modulate β-cell function.

Keywords: Stat5, Rip-Cre, Pdx1-Cre, Islets of Langerhans, β-cells, glucose homeostasis

INTRODUCTION

Growth hormone (GH), prolactin (PRL) and placental lactogen (PL) are potent growth factors for insulinoma cells in vitro [1–3]. In addition, these hormones stimulate insulin production in vitro, partially through the transcriptional activation of the insulin gene promoter [4]. These effects are mediated through the GH receptor (GHR) and the PRL receptor (PRLR), which activate the tyrosine kinase Jak2 and the transcription factors Stat5a and Stat5b (referred to as Stat5) [5, 6]. The mechanisms by which GH and PRL promote β-cell proliferation and gene expression, and the role of Stat5 have been explored in vitro [7–9]. In insulin-producing INS-1 cells and in cultured rat islets, GH and PRL induced the phosphorylation of Stat5a and Stat5b and their nuclear translocation [10, 11], suggesting their involvement in β-cell physiology. In support of this, PRLR−/− and GHR−/− mice exhibited a reduction in islet density and β-cell mass [12, 13]. Pancreatic insulin mRNA levels were also reduced in adult PRLR-null mice. In addition, PRLR−/− and GHR−/− mice exhibited impaired glucose tolerance and increased insulin sensitivity, respectively. These observations established a physiological role for GH and PRL in β-cell function and glucose homeostasis.

Although Stat5 mediates GH- and PRL-induced proliferation of insulinoma cell lines and insulin gene transcription, and expression of dominant-negative Stat5 in transgenic mice resulted in increased body weight and impaired glucose tolerance [14], the physiological consequences of a complete absence of Stat5 in β-cells remained elusive. Since Stat5−/− mice die perinatally [15] it is impossible to explore the function of Stat5 in the physiology of β-cells. To address the significance of Stat5 we deleted the Stat5 locus in the entire pancreas and in β-cells of mice using Cre-mediated recombination.

RESULTS

Deletion of the Stat5 locus in pancreatic β-cells and the hypothalamus altered islet morphology and content

Since the complete loss of Stat5 from the mouse genome results in perinatal lethality [15], we elected to delete Stat5 specifically in the pancreas of the mouse using Cre-mediated recombination. Two lines of Cre expressing mice were used to delete the Stat5 locus bracketed by loxP sites. While the RIP-Cre transgene [16] is active in pancreatic β-cells and in the hypothalamus [17], the Pdx1-Cre transgene [18] expresses Cre in pancreatic precursor cells, which results in the deletion of floxed genes in exocrine and endocrine cells. Mice were generated that carried two floxed Stat5 alleles and the RIP-Cre transgene (Stat5fl/fl; RIP-Cre mice) (Figure 1A). Stat5b was detected in β-cells throughout the islets of control mice but not in Stat5fl/fl; RIP-Cre mice (Figure 1B). There was no difference in insulin staining between control and Stat5fl/fl; RIP-Cre mice and levels of insulin mRNA in islets of these mice were comparable (data not shown). Loss of Stat5 resulted in a disrupted architecture of islets as evidenced by the migration of glucagon-expressing α-cells into the central region of the islets (Figure 1B, right panel). Deletion of the Stat5 locus was also observed in mice older than one year (data not shown), demonstrating that there was no selective advantage of cells carrying a non-recombined Stat5 locus.

Figure 1.

Targeted disruption of the Stat5 genes and assessment of Stat5 deletion in β-cells of Stat5fl/fl;RIP-Cre mice. (A) Schematic of the construct used to generate Stat5fl/fl;RIP-Cre mice. (B) Fluorescence immunohistochemical analysis of Stat5 (red) and glucagon (green) in control (C: Stat5fl/fl) and Stat5fl/fl;RIP-Cre mice. Pancreata from 7 month old mice were used for immunohistochemical analyses. Residual Stat5b-positive cells in Stat5fl/fl;RIP-Cre mice are non-β-cells. D) Impaired glucose homeostasis in 4–5 month old Stat5fl/fl;RIP-Cre mice and RIP-Cre transgenic mice. Results are expressed as average blood glucose level ± SEM of 6–8 males of each group. E) Insulin release from isolated islets. Islets were isolated from two animals per genotype which were used for glucose tolerance test at 5 months. Insulin secretion was induced by basal (3 mM) and 16.7 mM of glucose. (*, #)P < 0.05; (**, ##)P < 0.01; (***, ###)P < 0.001.

Stat5fl/fl; RIP-Cre mice developed mild obesity

Up to 12 weeks of age there was no significant difference in body weight between Stat5fl/fl; RIP-Cre and control mice. However, older Stat5fl/fl; RIP-Cre mice developed mild obesity (Table 1) and by 9 months of age, mutant mice weighed on the average 20% more than their control litter mates. Since the RIP-Cre transgene is also active in the hypothalamus [17, 19], the developing obesity could be due to the hypothalamic loss of Stat5 and an altered metabolism. Late-onset obesity was not observed in RIP-Cre transgenic mice or in Stat5fl/fl; Pdx1-Cre mice, further implicating hypothalamic Stat5 in the regulation of metabolism. To explore the overall metabolic consequence in Stat5fl/fl; RIP-Cre mice, metabolic responses were measured. At 7 months of age, serum glucose levels were slightly elevated and serum free fatty acids (FFA) and leptin levels were significantly higher in mutant mice but serum insulin levels were normal (Table 1). Body composition was measured by NMR. While the lean mass was similar between mutant and control mice the adipose tissue mass of Stat5fl/fl; RIP-Cre female mice was significantly elevated (Table 1).

Table 1.

Body composition and metabolic parameters of Stat5fl/fl; RIP-Cre mice

| Stat5fl/fl | Stat5fl/fl; RIP-Cre | |

|---|---|---|

| Body weight | 31.1± 0.9 | 36.8 ± 2.0 |

| Lean mass (g) | 22.51 ± 0.6 | 22.58 ± 0.6 |

| Total adipose mass (g) | 5.34 ± 0.9 | 12.14 ± 1.9b |

| Total adipose mass (% body weight) | 17.18 ± 2.7 | 32.11 ± 3.5b |

| Serum glucose (mg/dl) | 189.1 ± 2.8 | 210.2 ± 8.9a |

| Serum insulin (ng/ml) | 1.2 ± 0.9 | 1.2 ± 0.2 |

| Serum TG (mg/dl) | 131.6 ± 22.6 | 156.0 ± 18.9 |

| Serum FFA (mM) | 0.4 ± 0.04 | 0.6 ± 0.05a |

| Leptin (ng/ml) | 10 ± 1.9 | 21.2 ± 4.2 |

Weight and body composition was measured in 7 month-old female mice. Blood was collected from the tail vein directly into non-EDTA-coated capillary tubes and centrifuged to separate the serum, which was used to assay triglycerides, FFAs, glucose, insulin and leptin. Values shown are the mean ± SEM; seven to nine mice were used for analysis.

P < 0.05 vs. Control (Stat5fl/fl);

P < 0.01 vs. Control (Stat5fl/lf)

Stat5fl/fl; RIP-Cre mice failed to maintain glucose homeostasis

To examine the impact of the loss of Stat5 on the response to an acute glucose challenge, glucose disposal was assessed in fasted mice by glucose tolerance tests. At all ages examined (6 weeks to 11 months), Stat5fl/fl; RIP-Cre mice displayed higher glucose levels than the controls at all time points after glucose injection (Figure 1C). The severity of impaired glucose response was increasing in both female and male mice as they aged. As we described recently [20], RIP-Cre transgenic mice in a C57BL/6 background display some glucose intolerance as early as 6 weeks of age. Although glucose intolerance of 4~5 month-old Stat5fl/fl; RIP-Cre mice was more severe than that seen in RIP-Cre mice (Figure 1C), both showed reduced insulin secretion from isolated islets upon challenge with 16.7 mM of glucose (Figure 1D).

Stat5fl/fl; Pdx1-Cre mice exhibit normal glucose homeostasis

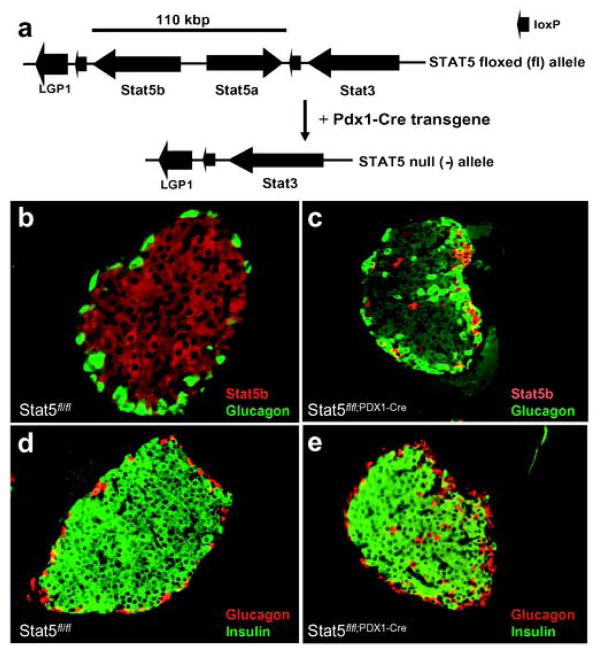

Since the presence of the RIP-Cre transgene by itself causes some glucose intolerance [20, 21], we were unable to draw firm conclusions about the contribution of pancreatic Stat5 in glucose homeostasis. To bypass this problem, Stat5fl/fl; Pdx1-Cre mice, in which Cre activity is confined to the pancreas, were generated (Figure 2a). Stat5fl/fl; Pdx1-Cre mice were observed over a 15 month period and their weights were indistinguishable from controls (Table 2). Moreover, levels of glucose, insulin and glucagons were normal over the 15 month period (Table 2). Islet architecture and the presence of Stat5b in pancreatic β-cells were evaluated by immunohistochemical analysis. In control mice Stat5b was detected throughout the islets (Figure 2b), but it was largely absent in Stat5fl/fl; Pdx1-Cre mice (Figure 2c). The few remaining Stat5b-positive cells in Stat5fl/fl; Pdx1-Cre mice either expressed glucagon (Figure 2c) or somatostatin (data not shown). This suggests that the Stat5 locus failed to be deleted in a small number of progenitor cells. In mutant mice, α-cells had migrated into the central region of the islets (Figure 2c), but not in control mice (Figure 2b). Real-time PCR analysis confirmed the loss of Stat5b mRNA in islets from Stat5fl/fl; Pdx1-Cre mice compared to Stat5fl/fl controls. There was no apparent difference in insulin staining between control and Stat5fl/fl; Pdx1-Cre mice (Figure 2d and 2e). Real time PCR confirmed the presence of comparable levels of insulin mRNA in islets from control and mutant mice, with beta actin as internal control (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Targeted disruption of the Stat5 genes and assessment of Stat5 deletion in β-cells of Stat5fl/fl; Pdx1-Cre mice. (a) Schematic of the Stat5 locus targeted with loxP sites and deletion of the Stat5 genes using the Pdx1-Cre transgene. (b–c) Assessment of Stat5 protein levels. Pancreata from 3 month old mice were used for immunohistochemical analyses. Sections were stained with antibodies against glucagon (green) and Stat5b (red). Immunofluorescence was viewed under an Olympus BX51 microscope (Olympus America Inc., Melville, N.Y.) and images were captured with a Nikon DXM1200 digital camera (Nikon Inc., Melville, N.Y.). (d–e) Fluorescence immunohistochemical analysis of insulin (green) and glucagon (red) in control (d: Stat5fl/fl) and Stat5fl/fl; Pdx1-Cre mice (e).

Table 2.

| Stat5 fl/fl | Stat5 fl/fl;PDX1-Cre | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight (g) | 28.8±1.3 | 28.7±2.5 | 0.49 |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 129.5±11.5 | 139.7±7.9 | 0.23 |

| Insulin (ng/ml) | 0.6±0.3 | 0.6±0.2 | 0.22 |

| Glucagon (ng/ml) | 246.7±27.5 | 272.3±89.4 | 0.61 |

Blood was collected from the tail vein directly into non-EDTA-coated capillary tubes and centrifuged to separate the serum, which was used for assay. Values shown are the mean ± SEM; four to five 10~15 months old fed mice were used for analysis.

To investigate the consequences of the loss of Stat5 on the response to an acute glucose challenge, glucose disposal was assessed in fasted mice by glucose tolerance tests. Glucose levels in fasting Stat5fl/fl; Pdx1-Cre mice prior to the administration (ip) of glucose were normal in all age groups tested (Figure 3A and 3B). Glucose tolerance was overtly normal in 2–3 months-old Stat5fl/fl; Pdx1-Cre mice (Figure 3A) but mild glucose intolerance developed in mice older than six months (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Results from glucose tolerance tests in Stat5fl/f and Stat5fl/fl; PDX1-Cre mice. Glucose tolerance tests were performed on fasted mice after an i.p. injection of 2 g/kg BW glucose at 10 weeks (a) and 6 months (b) of age. Blood glucose values were measured immediately before and 15, 30, 60, and 120 min after glucose injection. Results are expressed as average blood glucose level ± SEM of 6–8 males of each group. (*) and (**) means P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively, from independent t-tests (unpaired and two-tailed). P-value from ANOVA (analysis of variance between groups, two-way repeated) was 0.8661 at 10 weeks (a) and 0.0007 at 6 months (b) of age. (c–d) Glucose tolerance test was performed on 2–3 month old females before pregnancy (c) and on day 17 of gestation (d). Mice were fasted 9 hours and administrated 2 g/kg BW glucose loads at time zero. All results are reported as mean ± SEM of 5 females of each group. (*) means P < 0.05 from t-tests, but ANOVA shows no significant difference both before pregnancy (P=0.7127) and on day 17 of gestation (P=0.2021).

Mouse studies have suggested a role for GH and PRL on β-cell function during pregnancy. To test whether this effect is mediated by Stat5, glucose tolerance tests were performed prior to pregnancy and on day 17 of pregnancy. Stat5fl/fl; Pdx1-Cre female mice were slightly more glucose intolerant during pregnancy than their control litter mates (Figure 3D), but the differences were not statistically significant. These results imply that Stat5 signaling contributes to the optimal function of β-cells under conditions of stress, such as pregnancy and aging.

Discussion

Given the established role of GH, PRL and PL in inducing the proliferation of insulinoma cell lines and insulin gene transcription and secretion [7, 9–11, 22], as well as the involvement of Stat5 in these signaling pathways, more profound defects in Stat5 mutant mice had been anticipated. However, studies demonstrating a role for Stat5 in the proliferation of insulinoma cell lines might not fully reflect the in vivo situation since immortalized cell lines are subject to altered growth control. This study now demonstrates that a complete absence of Stat5 from pancreatic β-cells in mice has no discernable impact on islet development and function in young animals. However, Stat5 appears to be a modulating component in β-cell function in older mice.

The obesity, glucose intolerance and metabolic defects observed upon deletion of the Stat5 locus using the RIP-Cre transgene are likely not only due to the loss of Stat5 from pancreatic β-cells, but also the results of other events. In particular, RIP-Cre mice by themselves develop some glucose intolerance [21], and loss of Stat5 from the hypothalamus possibly influences metabolic pathways. Thus these mice are not suited to explore the role of Stat5 in the physiology of pancreatic β-cells.

Tissue culture studies have suggested that Stat5 is central to the GH- and PRL-mediated proliferation of β-cells and the activation of the genes encoding insulin and cyclin D2 [7–9]. In support of a role for Stat5, expression of constitutively active Stat5b in cell lines stimulated GH-independent proliferation [7, 23]. Since functional islets were present in Stat5 mutant mice analyzed in this study, it is clear that the presence of Stat5 is not essential for the proliferation of β-cells. However, no stereological analyses were performed and it is possible that the β-cell mass in Stat5-mutant mice is slightly different. Since PRLR−/− and GHR−/− mice displayed a reduction in islet density and β-cell mass [12, 13] it is possible that β-cell proliferation is controlled by signaling pathways other than Stat5. GH and PRL stimulate insulin production in vitro, in part through the activation of Stat5 and thus a transcriptional induction of the insulin gene promoter [4–6, 10, 11]. Again, we found that levels of insulin mRNA were unaltered in mutant mice, further demonstrating a negligible role of Stat5 in the context of the pancreas in vivo.

A recent study also addressed the role of Stat5 in vivo through the expression in transgenic mice of a dominant-negative mutant of Stat5b (DNSTAT5) or a constitutively active mutant of Stat5b (CASTAT5) under control of the rat insulin 1 promoter (RIP) [14]. Mild glucose tolerance, increased body weight, increased insulin and leptin levels and an increased β-cell area were observed in DNSTAT5 transgenic mice only on a high-fat diet but not on a standard diet. Thus, the loss of Stat5 in islets due to the deletion of the genes or due to expression of a dominant negative form results in similarly mild defects and supports the notion that Stat5 modulates β–cell function only under defined physiological conditions.

Although a wide range of tissue culture cell experiments have linked Stat5 to many aspects of cell physiology, the analysis of mice from which Stat5 has been deleted in defined tissues and cells has not confirmed all of these proposed roles. Two explanations can be offered for this discrepancy. It is possible that the functions of Stat5 observed in tissue culture cells are unique to those experimental systems but do not reflect the situation encountered in the context of an animal. Alternatively, it is possible that other members of the Stat family, namely Stat1 and Stat3, compensate for the loss of Stat5. Since the Stat3 gene is juxtaposed to the Stat5a/b locus it is impossible at this time to test this possibility through the deletion of all three genes.

METHODS

Generation of Stat5 fl/fl; RIP-Cre and Stat5 fl/fl; Pdx1-Cre mice

Stat5fl/fl mice [15] were bred with RIP-Cre [16]or Pdx1-Cre [18] transgenic mice. Mice were maintained on a 12-h light, 12-h dark cycle and fed water and standard diets. The NIDDK Animal Care and Use Committee approved all procedures and studies were conducted in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines. Genotyping was performed by PCR amplification of tail DNA from each mouse at 3 week of age. The primers for genotyping of the Stat5 floxed allele were primer 1 (5′-GAA AGC ATG AAA GGG TTG GAG-3′), primer 2 (5′-AGC AGC AAC CAG AGG ACT AC-3′) and primer 3 (5′-AAG TTA TCT CGA GTT AGT CAG G-3′). Primer 1 and 2 pair amplify a fragment of 450 bp from wild-type mice and a 200-bp fragment was detected by primer 2 and 3; the latter is located in the pLoxpneo vector, in mice heterozygous or homozygous for the Stat5 floxed allele. Primers for the RIP-Cre transgene were 5′-CTC TGG CCA TCT GCT GAT CC-3′, which binds in the insulin 2 gene promoter and 5′-CGC CGC ATA ACC AGT GAA AC-3′, which binds in the Cre sequence. This pair amplifies a 550 bp Rip-Cre specific fragment. For the detection of the Pdx1-Cre transgene, 5′-TTG AAA CAA GTG CAG GTG TTC G-3′ and 5′-CCA TGA GTG AAC GAA CCT GGT CG-3′ were used.

Preparation of pancreatic sections and immunohistochemical analyses

Pancreas samples were dissected from fed mice and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde/PBS solution overnight at 4°C. Five-micrometer longitudinal sections of paraffin-embedded sections were rehydrated with xylene followed by decreasing concentrations of ethanol. Antigen retrieval was performed by heat treatment with an antigen unmasking solution (Vector Laboratories Inc.), and tissue sections were blocked for 30 min in PBS-Tween (PBST) containing 3% goat serum. Sections were incubated with anti-Glucagon (Sigma) and anti-Stat5b (sc-836, Santa Cruz, Calif.) antibodies. The primary antibodies were allowed to bind overnight at 4°C. Secondary antibodies were from Molecular Probes, Inc. (Eugene, Oreg.) and included goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) conjugated to Alexa Fluor 594 and goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488. Sections were incubated in the dark for 30 min, washed twice in PBST, and mounted with Vectashield (Vector Laboratories Inc.). Immunofluorescence was viewed under an Olympus BX51 microscope (Olympus America Inc., Melville, N.Y.) and images were captured with a Nikon DXM1200 digital camera (Nikon Inc., Melville, N.Y.).

Analytical assays and metabolic rates

Blood glucose levels were determined from the tail vein using a glucometer (Accu-Chek, Roche, Indianapolis, IN). Serum insulin and leptin levels were measured by radioimmunoassay (Linco Research Inc., St. Charles, MO). Serum fatty acids and triglyceride levels were analyzed in fed mice using a commercial FA kit (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) and the GPO-Trinder kit (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO), respectively. Insulin and glucose tolerance tests were performed in fasted animals after i.p. injections of either insulin (0.75U/kg body weight) or glucose (2 g/kg body weight). Blood glucose values were measured immediately before and 15, 30 and 60 min after insulin injection, and before and 15, 30, 60, and 120 min after glucose injection. For insulin release, glucose (3 g/kg body weight) or L-arginine (1 mg/g BW in PBS) [24] was injected IP, and venous blood was collected at 0, 2.5, 5, 15, and 30 min in chilled heparinized tubes, immediately centrifuged, and the plasma stored at −20°C. Insulin levels were measured with a RIA kit. Metabolic rates were measured in fed female mice 7 month of age by indirect calorimetry using the Oxymax system (Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH) as described by Héron-Milhavet et al [25]. Data were collected for 24 h at room temperature (22°C) and for 24 h at thermoneutral temperature (30°C). Data are expressed as the average of 24 h and normalized to (total body weight)0.75.

Body composition

Body composition was measured in awake mice using an NMR analyzer (Bruker Minispec mq10, Bruker Optics Inc., Billerica, MA).

Insulin secretion from isolated islets

Islets were isolated from 4 month old control (Stat5fl/f) and Stat5fl/f; RIP-Cre mice by collagenase digestion (Liberase, Roche Diagnostics, IN) followed by centrifugation over a Histopaque gradient (Sigma, St Louis, MO). Islets were handpicked under a stereo microscope and incubated overnight in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 IU/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin at 37°C and 5% CO2. For assay of insulin secretion, islets were handpicked and incubated in Krebs-Ringer solution (119 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCL, 2.2 mM CaCl2, 1.19 mM KH2PO4, 240 mM NaHCO3, 1.19 mM MgSO4, 10 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 0.1% bovine serum albumin, and 3.3 mM glucose) at 37°C for 45 min. At the end of the incubation period, islets were transferred to a new 12-well plate and stimulated with various glucose concentrations (3.3 mM and 16.7 mM) for 1 h at 37°C. Supernatants were collected and insulin release was measured with a rat insulin ELISA kit (Crystal Chem. Inc., Chicago, IL). Samples were run in triplicate, and the number of experiments was n= 4–5. Total islet insulin content was measured in batches of five islets. The islets were sonicated twice in 200 μl acidic ethanol (0.25 mol/l HCl in 87.5% ethanol) and incubated overnight at 4°C. The samples were centrifuged and total insulin was measured in the supernatant.

Statistical analysis

All results are reported as mean ± SEM for equivalent groups. Results were compared with independent t tests (unpaired and two-tailed) reported as P values.

Acknowledgments

We thank Shoshana Yakar, Dinesh Gautam, and Andras Bratincsak for expert technical advice and John Hanover for his help with the microscopic observation. We also thank Doug Melton for providing the Pdx1-Cre mice.

Abbreviations

- Stat

Signal transducer and activator of transcription

- JAK

Janus kinase

- GH

growth hormone

- PRL

prolactin

- PL

placental lactogen

- GHR

GH receptor

- PRLR

PRL receptor

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Brelje T, Scharp D, Lacy P, Ogren L, Talamantes F, Robertson M, Friesen H, Sorenson R. Effect of homologous placental lactogens, prolactins, and growth hormones on islet B-cell division and insulin secretion in rat, mouse, and human islets: implication for placental lactogen regulation of islet function during pregnancy. Endocrinology. 1993;132:879–887. doi: 10.1210/endo.132.2.8425500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nielsen J, Galsgaard E, Moldrup A, Friedrichsen B, Billestrup N, Hansen J, Lee Y, Carlsson C. Regulation of beta-cell mass by hormones and growth factors. Diabetes. 2001;50:S25–29. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.2007.s25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nielsen J, Svensson C, Galsgaard E, Moldrup A, Billestrup N. Beta cell proliferation and growth factors. J Mol Med. 1999;77:62–66. doi: 10.1007/s001090050302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galsgaard E, Gouilleux F, Groner B, Serup P, Nielsen J, Billestrup N. Identification of a growth hormone-responsive STAT5-binding element in the rat insulin 1 gene. Mol Endocrinol. 1996;10:652–660. doi: 10.1210/mend.10.6.8776725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goffin V, Kelly P. The prolactin/growth hormone receptor family: structure/function relationships. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 1997;2:7–17. doi: 10.1023/a:1026313211704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takeda K, Akira S. STAT family of transcription factors in cytokine-mediated biological responses. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2000;11:199–207. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(00)00005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedrichsen B, Galsgaard E, Nielsen J, Moldrup A. Growth hormone- and prolactin-induced proliferation of insulinoma cells, INS-1, depends on activation of STAT5 (signal transducer and activator of transcription 5) Mol Endocrinol. 2001;15:136–148. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.1.0576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brelje T, Parsons J, Sorenson R. Regulation of islet beta-cell proliferation by prolactin in rat islets. Diabetes. 1994;43:263–273. doi: 10.2337/diab.43.2.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brelje T, Stout L, Bhagroo N, Sorenson R. Distinctive roles for prolactin and growth hormone in the activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 in pancreatic islets of langerhans. Endocrinology. 2004;145:4162–4175. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brelje T, Svensson A, Stout L, Bhagroo N, Sorenson R. An immunohistochemical approach to monitor the prolactin-induced activation of the JAK2/STAT5 pathway in pancreatic islets of Langerhans. J Histochem Cytochem. 2002;50:365–383. doi: 10.1177/002215540205000308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stout L, Svensson A, Sorenson R. Prolactin regulation of islet-derived INS-1 cells: characteristics and immunocytochemical analysis of STAT5 translocation. Endocrinology. 1997;138:1592–1603. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.4.5089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freemark M, Avril I, Fleenor D, Driscoll P, Petro A, Opara E, Kendall W, Oden J, Bridges S, Binart N, Breant B, Kelly P. Targeted deletion of the PRL receptor: effects on islet development, insulin production, and glucose tolerance. Endocrinology. 2002;143:1378–1385. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.4.8722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu J, Coschigano K, Robertson K, Lipsett M, Guo Y, Kopchick J, Kumar U, Liu Y. Disruption of growth hormone receptor gene causes diminished pancreatic islet size and increased insulin sensitivity in mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004;287:E405–413. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00423.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jackerott M, Moldrup A, Thams P, Galsgaard ED, Knudsen J, Lee YC, Nielsen JH. STAT5 Activity in Pancreatic {beta}-Cells Influences the Severity of Diabetes in Animal Models of Type 1 and 2 Diabetes 10.2337/db06-0244. Diabetes. 2006;55:2705–2712. doi: 10.2337/db06-0244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cui Y, Riedlinger G, Miyoshi K, Tang W, Li C, Deng CX, Robinson GW, Hennighausen L. Inactivation of Stat5 in mouse mammary epithelium during pregnancy reveals distinct functions in cell proliferation, survival, and differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:8037–8047. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.18.8037-8047.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Postic C, Shiota M, Niswender K, Jetton T, Chen Y, Moates J, Shelton K, Lindner J, Cherrington A, Magnuson M. Dual roles for glucokinase in glucose homeostasis as determined by liver and pancreatic beta cell-specific gene knockouts using Cre recombinase. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:305–315. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.1.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gannon M, Shiota C, Postic C, Wright C, Magnuson M. Analysis of the Cre-mediated recombination driven by rat insulin promoter in embryonic and adult mouse pancreas. Genesis. 2000;26:139–142. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1526-968x(200002)26:2<139::aid-gene12>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lammert E, Gu G, McLaughlin M, Brown D, Brekken R, Murtaugh LC, Gerber HP, Ferrara N, Melton DA. Role of VEGF-A in Vascularization of Pancreatic Islets. Current Biology. 2003;13:1070–1074. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00378-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inoue M, Hager J, Ferrara N, Gerber H, Hanahan D. VEGF-A has a critical, nonredundant role in angiogenic switching and pancreatic beta cell carcinogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2002;1:193–202. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00031-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee JY, Hennighausen L. The transcription factor Stat3 is dispensable for pancreatic [beta]-cell development and function. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2005;334:764–768. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.06.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee J-Y, Ristow M, Lin X, White MF, Magnuson MA, Hennighausen L. RIP-Cre Revisited, Evidence for Impairments of Pancreatic beta-Cell Function 10.1074/jbc.M512373200. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:2649–2653. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512373200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Galsgaard E, Friedrichsen B, Nielsen J, Moldrup A. Expression of dominant-negative STAT5 inhibits growth hormone- and prolactin-induced proliferation of insulin-producing cells. Diabetes. 2001;50:S40–41. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.2007.s40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Friedrichsen B, Richter H, Hansen J, Rhodes C, Nielsen J, Billestrup N, Moldrup A. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 activation is sufficient to drive transcriptional induction of cyclin D2 gene and proliferation of rat pancreatic beta-cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:945–958. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kulkarni R, Bruning J, Winnay J, Postic C, Magnuson M, Kahn C. Tissue-specific knockout of the insulin receptor in pancreatic beta cells creates an insulin secretory defect similar to that in type 2 diabetes. Cell. 1999;96:329–339. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80546-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Héron-Milhavet L, Haluzik M, Yakar S, Gavrilova O, Pack S, Jou W, Ibrahimi A, Kim H, Hunt D, Yau D, Asghar Z, Joseph J, Wheeler M, NA A, LeRoith D. Muscle-Specific Overexpression of CD36 Reverses the Insulin Resistance and Diabetes of MKR Mice. Endocrinology. 2004;145:4667–4676. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]